1. Introduction

1.1 Teaching BPS to architects in the climate emergency context

Architectural education requirements have shifted to include climate emergency goals and learning outcomes.1 Many schools have made further changes to enhance students’ climate design knowledge and ability, including teaching building performance simulation (BPS) to architecture students. Here, BPS is taken to mean computational tools to model and quantitatively predict a building’s performance, e.g. embodied/operational carbon and daylighting.

Widely varying architectural BPS teaching with different epistemological presumptions is found in the literature. The majority of papers report on individual courses absent a consensus educational theory. Alsaadani & Bleil De Souza’s (2018) review of the literature on BPS pedagogy provides a useful two-paradigm framework to characterize BPS teaching: one paradigm emphasizes expert analysis, the other design decision support. With the latter, users are either ‘consumers’ of others’ simulation results or ‘performers’ of simulation. Alsaadani and Bleil De Souza noted polarized perspectives within the user-centered approach; proponents of ‘performer’ approaches hold BPS to be an empowering skill for architects toward which schools should aspire; proponents of the ‘consumer’ paradigm counter that in actual practice simulation is typically done by specialists. The review found the ‘performer’ paradigm to be more common. This paper analyzes a performer paradigm course that frames BPS as a tool for ‘sensemaking’ in early design ideation. To understand BPS thus, it is helpful first to clarify what sensemaking is relative to design and analysis.

1.2 Sensemaking: how knowledge becomes actionable

When one experiences something new, one must reconcile it with one’s preexisting knowledge. When sensemaking, a person comes to grasp ambiguous, surprising, or otherwise incongruent information, thereby forging new understanding from confusion (Sandberg & Tsoukas 2015). Making sense describes learning from interaction with the world, and from assimilation of formal classroom teaching. Psychology researchers (e.g. Anderson 1982) describe that learning skills (such as design) requires one to move from an explicit ‘declarative knowledge’ stage where facts are learned to an implicit ‘procedural knowledge’ stage where facts become embedded in methods. Procedural knowledge drives early-stage design choices well made before analysis begins; any declarative knowledge one has not yet made sense of is therefore not yet in play, even if it is ‘known.’ Describing all mechanisms for procedural knowledge development is outside the scope of this paper, but sensemaking is one way architecture students move knowledge from declarative to procedural, and thus apply knowledge about energy to design choices.

Sensemaking is context dependent. For example, the sense made where rules and ordered, rational processes are stressed (e.g. process engineering) differs radically from that made where core principles and nonlinear intuitive processes are emphasized (e.g. creative arts) (Snowden 2005). Context influences which cues individuals attend to, and how they interpret them. Sensemaking is also highly individual and non-uniform. Scholars describe sensemaking as an individual’s attempt to bridge gaps in understanding (Dervin 1998), as a reframing after unexpected discovery (Klein et al. 2007) and as verbal narrative creation, rhetorically asking, ‘How can I know what I think until I see what I say?’ (Weick 1995: 18). Individuals build unique, individualized but coherent schemas to guide actions as they uncover new information. This is critical for architectural students learning to design.

1.3 Sensemaking in design

Early-phase architectural design embeds sensemaking as designers confront new information on each project. Sensemaking culminates in actions that evolve the design and may build new procedural knowledge. This aligns with Schön’s (1992) reflective practice, which describes architectural design as spontaneous, intuitive performance of knowledge, akin to Anderson’s (2014) procedural knowledge, and to Gero’s (1990) function–behavior–structure framework whereby a designer compares expected with actual behavior and transforms a structure until it achieves the desired function (for a further summary of design methodology theory, see Cross’s 2007 synthesis). Further, Schön’s (1985) ‘reflection in action’ occurs when tacit knowledge leads to surprising results to be explored and incorporated. However, cognitive reflection is in counterpoint to design intuition. Some argue that architectural design is ‘making’ focused (Lloyd & Scott 1995), and foregrounds sensibility and embodied responses over rational cognition in the generation of proposals (Rylander Eklund et al. 2022). In the sensemaking of design unexpected information triggers action. Schön (1985: 26ff.) terms exploring and responding to surprise ‘a reflective conversation with the situation,’ and Klein et al. (2007) calls it ‘reframing.’ Sensemaking in early design is distinct from the analytical processes of developed design once form and direction are clear; sensemaking is the intuitive process of forming provisional understandings to take initial design action.

Designerly sensemaking is visuospatial, not verbal. Paraphrasing Weick (1995: 18), a designer might ask, ‘How can I know what I think until I see what I make?’ Visual information is particularly critical to student sensemaking. Images of design intent are overall more salient to architecture students than quantitative expressions (LaVine 2001). Visualization is especially significant to high-performance design exploration (Hamza & Horne 2007). Alsaadani & Bleil De Souza (2018) find architectural BPS teaching more visually based in initial exercises (usually daylighting analysis), shifting toward the quantitative (often thermal analyses) as students progress. Visual sensemaking remains important to practicing architects. Architects still use traditional visual methods (e.g. hand sketches and physical models) for ideation and communication, despite the ubiquity of computing in contemporary practice (Loukissas 2012). Simulation is one visualization tool in contemporary practice used to ‘transform quantitative models of building physics into qualitative sensory experiences […] through visualization’ (Peters 2018: 2). Thus, BPS can transcend simpler analysis tools through visuals, suggesting qualities of data that invite speculation. Reflection upon design (here, through data) builds tacit learning into explicit knowledge (Schön 1985). While visual information is essential, reflection can draw from multiple, competing knowledge traditions to arrive at actionable understanding (Fauconnier & Turner 1998). Novel information in many forms is incorporated to generate a design proposal; BPS can facilitate the convergence of quantitative and visuospatial information for architecture students.

1.4 Technologically facilitated design sensemaking

Computational design tools facilitate efficient, precise design by processing information that is difficult to make sense of through analog means. Lawson (2002) notes that computer-aided design (CAD) facilitates creativity by easing representation of difficult-to-draw forms; Picon (2010) that algorithmic tools enable innovative form-making; and Loukissas (2012) that coding and computation logics engender new forms of creativity and collaboration. In addition, novice designers may lean on computational design tools to make sense of overwhelming data before developing robust analytical skills. Several performer-paradigm BPS courses specifically aim to develop skills for early-stage design. Notable examples include Kim et al.’s (2013) use of advanced simulation for preliminary design synthesis; Doelling & Nasrollahi’s (2012) use of parametric simulation in a high-performance design process; Madina et al.’s (2021) use of lighting simulation for daylighting design; Passe’s (2020) structured BPS workflow coupled to design milestones; Reinhart et al.’s (2012) gamification of BPS-influenced design decisions; and Doelling & Jastram’s (2013) use of physically spatialized BPS results to reframe the relationships between form and performance. In each of these cases, BPS is leveraged to generate situated information about a particular proposal’s performance, enabling exploration and deep understanding beyond rule-of-thumb generalities rather than tool proficiency.

Specifically, encountering unexpected information deepens understanding about a design. If BPS simulation results only affirm expectations, arguably no new, better understanding is built. Surprises are central to reframing and sensemaking (Sandberg & Tsoukas 2015) and important to design. Schön (1992: 131) notes:

The design process opens up possibilities for surprise that can trigger new ways of seeing things, and it demands visible commitments to choices that can be interrogated to reveal underlying values, assumptions, and models of phenomena.

Suwa et al. (2000) also found that surprises are essential to developing a deep understanding of situated issues and requirements in design. An advantage of BPS is the potential for the discovery of new, situated knowledge which runs counter to expectation, triggering a designer’s cycle of sensemaking. Computational tools can thus help students develop situated, intuitive understanding of early design proposals; this allows for sensemaking of declarative knowledge and the emergence of deeper, procedural knowledge among novice designers.

However, BPS is not guaranteed to provide surprises to spark sensemaking. First, BPS results have ‘epistemic uncertainty’ because models may have been poorly constructed; results are thus implicitly suspect (Li et al. 2013). Results that cannot be trusted may be ignored rather than probed, so managing uncertainty is particularly important if sensemaking is to occur at all (Dritsa & Houben 2024). Problematically, one can even make sense of plausible-seeming outputs, even if inaccurate (Weick et al. 2014). Ensuring sufficient accuracy for early-design sensemaking is essential for student learning to occur (this is discussed further below).

Second, sensemaking potential is contingent on the circumstances of BPS usage. Uptake of design computational technology depends heavily on how users make sense of it, and the institutional context of use (Griffith 1999; Linderoth 2017). Successful technology adoption depends on alignment with users’ identity narratives; e.g. energy consultants, architects, and mechanical engineers have overlapping technical expertise, but come to use and identify with different software. Further, Lawson (2002) cautiously notes that CAD may impede creativity by disconnecting drafting from construction; and Klein et al. (2006) writes that while technology can facilitate data insights, decision-assistance tools may in fact impede sensemaking by restricting data exploration. An emphasis on processes of discovery and experimentation in course materials can, for example, influence the potential for student BPS sensemaking.

Third, research has shown that designers exert tremendous effort to maintain or only incrementally tweak an initial design proposal (Cross 2004; Lloyd & Scott 1995; Rowe 1987). Once a provisional design is in place, new information (such as simulated performance data) may not thus trigger making new sense of a design. Encouraging wholesale revision of design after new discoveries is a broader challenge in architectural teaching, but is arguably facilitated by building student trust in their own findings.

1.5 Managing epistemic uncertainty: the importance of the frame

Building trust in BPS results such that sensemaking can take place means setting a floor for result accuracy and a ceiling for result precision. Sufficient accuracy for early-design sensemaking in student projects requires management techniques unique from other use contexts. Beausoleil-Morrison (2019) manages BPS’s epistemic uncertainty by structuring critical self-evaluation through comparative ‘autopsies’ of student results, thereby setting appropriate expectations around results and diagnosing problems. BPS results for sensemaking require less precision than analyses in later design, so managing expectations about precision is essential. Anderson (2014: 217) deemphasizes the calibration of models to actual performance, arguing that ‘architects are better served using comparative energy savings instead of predicted energy performance.’ Comparative, simplified modeling aligns with den Hartog et al.’s (1998: 10) assertion that early-design-stage decisions need far less precision than simulation can provide.

Certain design criteria need not be determined in five digits. A global result may be sufficient, especially when one is only interested in the direction the performance of a design takes when varying a given parameter.

Loukissas (2012) emphasizes the importance of setting appropriate expectations, noting that:

Computer simulations are never true in an absolute sense, but they can become valid for a particular audience when framed appropriately.

Simulations provide indications, not directives, for design decision-making. Structured, well-bounded use of BPS can manage both accuracy and precision sufficient for students’ sensemaking; the mechanisms for doing so in this paper’s course are described below. BPS output can thus provide the surprising information to spark sensemaking when the surrounding epistemic frame manages uncertainty.

1.6 Differences between novices and experts

Novices differ from experts when making sense and designing. A full discussion of differences is outside the scope of this paper, but a contrast relevant to this inquiry is in information-gathering strategies. Novices collect more data than experts, who move more quickly to conjectural solutions (Cross 2004), likely because experts have extensive knowledge of precedents upon which to draw when positing new designs (Schön 1985, 1988). This mental library of precedents supports an ‘appreciative system’ aiding design judgment (Checkland & Casar 1986; Lurås 2016; Vickers 1965). Aspiring designers have relatively small libraries and immature appreciative systems; consequently, surprising anomalies are rare, and sensemaking limited. Working backward from the desired goal to the design proposal depends on an individual’s judgement to assess and prioritize data (Kolko 2010). Thus, high-performance design is particularly challenging for non-experts lacking the repertoire of examples on which to build an appreciative system enabling good judgements. Using BPS to explore designs helps build a viable appreciative system with a repertoire of high-performance exemplars such that sense can be made of data during design.

1.7 Sensemaking cultivation with BPS

This paper argues that novices can learn BPS to grow their expertise not with the tool per se, but to develop deep understandings of performance data for early-design ideation. To differentiate it from other architectural design processes (e.g. analysis, formal design) and emphasize the subjective grappling with new and varied information, this is termed ‘spatial-data sensemaking’; it is akin to the design synthesis via simulation described by Kim et al. (2013) in a process of ‘discovery–performance–design.’ While the overarching teaching approach is a necessary component of understanding BPS as a potential tool for sensemaking, determining whether students actually make sense in this way requires their perspectives.

This paper qualitatively investigates a course taught within the ‘performer’ paradigm that emphasizes the use of BPS for ‘sensemaking’ in early design, whereby performance exploration facilitates students’ deep intuitive understanding of situated building physics behaviors well before full-building simulation is attempted. Specifically, the paper addresses the question: Can BPS be instrumentalized to develop students’ spatial-data sensemaking? Intrinsic to this question is whether students perceive their own understanding through reflection, i.e. they have ‘made sense’ of their design’s performance. Assessing student work products, while necessary for course grading, is insufficient to determine whether sensemaking has occurred; students can perform rote analyses without deeply understanding implications for design decisions. Within the larger query are several related questions: How do students construe themselves as designers in relation to BPS? What image do students construct of BPS? How do students understand the usage of BPS more broadly? Answering aims to shed light on the students’ perceptions and understanding of BPS from their perspective as novice performers.

2. Course description

2.1 Overview

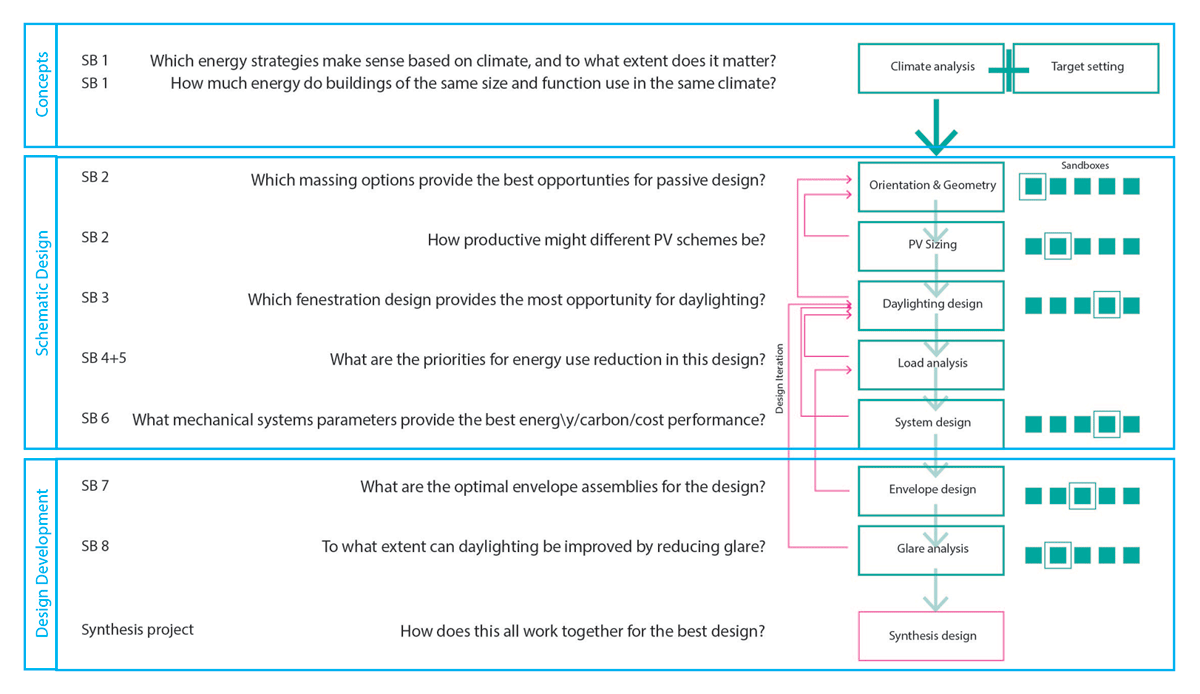

The lecture/lab course stressed asking ‘good questions’ when developing low-carbon design. Structuring appropriate questions and developing processes to answer them is key to architects’ BPS use (Anderson 2014). Figure 1 shows the 10 design-driving questions and associated analysis processes and open-ended experimentations. The course consisted of eight ‘skillbuilder’ assignments in both single-aspect and full-building simulation where students learned to self-audit the results with visual checks. Students then worked collaboratively to synthesize previous results and build an argument for a final proposal. This approach is platform agnostic, but this course used the ClimateStudio plug-in for Rhino.

Figure 1

Course organization: topically driven questions are tied to specific types of analysis.

Note: Prescriptive, self-audited baseline analyses are followed by open-ended explorations.

2.2 Lecture + lab organization

Weekly 90-min lectures provided a topical overview of building physics, relevant metrics, design process, and exemplar precedents, and reviewed computational underpinnings to help make sense of how simulation might contribute to design. This is important given a need for students to make sense of a tool itself (Linderoth 2017) and resist passivity about data interpretations (Klein et al. 2006). Lectures reviewed BPS-integrated design processes underpinning exemplar projects. Weekly 90-min labs included group critiques of building performance data graphics, and guided simulation instruction in a large teaching computer lab.

2.3 Projects: skill building, sandboxes, and synthesis

Students were tasked with exploring and improving the performance of a 21,000 ft2 (1950 m2) wellness center. Students built the model geometry, one key to internalizing its sensibilities (Loukissas 2012). Step-by-step instructions guided students on geometry construction (e.g. interior geometry was unnecessary for facade radiation analyses) and simulation input parameters. After running preliminary analysis prescriptively, students were given open-ended tasks to explore with the model (e.g. ‘Experiment with glazing materials to see how this impacts your achievement of the daylighting target’).

Weekly projects broached a single topic such as massing or photovoltaic configuration (see the topics in Figure 1). Initial inquiry via BPS was strictly constrained to reduce epistemic uncertainty, and to allow students gradually to make sense of their design proposal’s performance along the studied dimensions (e.g. energy production, space-conditioning energy usage, daylighting, glare), thereby incrementally growing a situated appreciative system for the culminating synthesis project. This approach aligns with Passe’s (2020) highly structured, 10-stage workflow of discreet analyses performed while developing a design.

Like the exercises in other performer-paradigm BPS courses (Doelling & Jastram 2013; Doelling & Nasrollahi 2012; Kim et al. 2013; Madina et al. 2021; Reinhart et al. 2012), this experimentation aimed to build and deepen students’ design sensibility. Students made sense of these experiments through brief written statements about design changes influenced by their results, operationalizing Schön’s (1985) ‘reflection upon reflection-in-action.’ Upon completion of initial skill-building, students collaborated to revisit analyses, synthesize holistic design recommendations, and develop graphics and narratives arguing for redesign.

2.4 Visual plausibility

While underlying simulation engines were presumed valid and precise, the course had to manage the implicit epistemic uncertainty of student-generated geometry and parameter selection. However, the course presumed that high accuracy was not required, as den Hartog et al. (1998) noted. Students were guided to manage uncertainty by reviewing graphic outputs for ‘reasonable’ accuracy against provided examples or descriptions of output patterns and ranges, and advised that the outlying results meant problems with the model. Each skillbuilder assignment included an image of correct baseline design results for students’ visual comparison. Also, with every modeling run, students were asked the following. Do the results look to be in the patterns you expect? Do the results look to be in the numerical range of reality? Both questions were supported with a brief description of expected patterns and ranges. Once baseline results were thus self-audited, students could feel more confident about their results in the exploratory ‘sandbox’ exercises building upon the baseline models. Furthermore, students were encouraged to collaborate and compare results with peers, and to pursue anomalous results.

3. Methods

This paper used qualitative methods to investigate student perceptions and points of view in their end-of-term reflections. This analysis presumed a Piagetian constructivist model of learning, where students actively assemble understanding through experiences; they do not passively absorb knowledge squarely as an instructor intends. The intention was to provide a student-centered description of BPS’s pedagogical utility in cultivating spatial-data sensemaking. Two years of anonymized student reflections (n = 104) on course learning outcomes were coded and thematized using qualitative analysis software NVivo. The reflection prompt required a 500-word written response to characterize the extent to which course learning outcomes were achieved, and to describe expectations for future use of the course knowledge academically and professionally.

Initial descriptive codes drawn from a review of the sensemaking literature included the following: capabilities, understanding, descriptors of self, attitudes toward simulation, and future uses of simulation. After initially coding terms and concepts in the reflections line by line to these broad themes, reflections were then recoded to elicit dimensions within initial thematic categories. Thematic categories were then reassembled and organized to present the range of perspectives held by students.

4. Results and analysis

Themes in student reflections shed light upon how the students saw themselves as architectural designers in relation to BPS, how they framed their emerging understanding of BPS itself, and how they envision the relationship of BPS to their future work. Table 1 lists the themes and student quotations typifying each.

Table 1

Thematic results and illustrative quotations.

| STUDENT CONSTRUCTIONS OF THEMSELVES AND THEIR KNOWLEDGE | |

| New insight into buildings and energy | |

| What ‘shocked me the most’ […] I always knew that elements of a building consumed a lot of energy, but I never knew how much | |

| I realized this and several other things wrong with my old design which claimed to be ‘sustainable’ which makes me want to face-palm myself | |

| I ‘did not understand the units of measurement as well as I thought I did’ | |

| Deepened consciousness of buildings and energy through building performance simulation (BPS) | |

| Of specific elements/systems | I never realized how drastic something as simple as the material of the façade on a building can have. I think I am now concerned about mechanical systems, where windows are placed, and also what material goes on where. I now realize that a little bit up front can go a very long way in the long run when it comes to energy consumption. Especially heating and cooling systems! |

| Understanding through attentional focus | Thermal loads, lighting quality and quantity were not something I often considered, let alone understood |

| Understanding expressed as a language | Energy consumption is now ‘easy to talk about in my own words’ |

| Understanding attributed to visual/graphic outputs | The visuals of data helped for a greater understanding of what the lectures were discussing, as well as the direct impact on a site-specific structure |

| Situating knowledge in a broader context | I feel like I have a better understanding of what environmentally conscious design can look like |

| More sophisticated understanding of design with energy-related factors through BPS | |

| Understanding interrelationships and trade-offs | The small edits in one place can work against changes in another, it is all a delicate balancing act |

| I learned that increasing performance of a building can have a negative impact on the user’s comfort level and overall experience in the building, which shows that there must be some give and take when trying to design a sustainable building | |

| Understanding part–whole relationships | It was interesting seeing how you can alter a few minor things and get a lower results in energy consumption |

| I see how they all work together to achieve the goal of saving energy and operating costs. I also do see how energy efficient windows can make such impact. I think I have achieved this because now I look at these components both individually and as a whole | |

| Recognizing the development of intuition | I’ve also grown to understand that energy, lighting, comfort and building geometry are all related to one another when designing a building. I believe I understood this prior to this class, but our final project really hammered this idea home. We performed tests and made decisions in the composition of our final project that positively impacted daylighting and visual comfort while sacrificing energy efficiency and vice versa. Now on top of understanding this concept, I actually have experience and a feeling for the degree to which this is the case |

| I was ‘able to test the things we as students hear in lecture about what good passive system design is. A lot of these rules are stated but being able to test them and see the numbers go up or down was a great way to reinforce intuitive understanding what certain design moves will do’ | |

| STUDENT CONSTRUCTIONS OF BPS AS A DESIGN TOOL | |

| BPS produces useful visual information | |

| I was able to compare different design options by visually seeing the analysis results | |

| By showing accurate charts and data it allows me to be more confident in having specific reasons why certain designs work better than others | |

| Seeing charts and graphs and data spreads that reinforce my design concepts feels great. It’s a validation that goes above just aesthetics in my opinion | |

| BPS yields quantitative outputs | |

| Being able to put a metric value on something that has come from my head and seeing how it performs has been so fascinating. These are things that I always thought about but never quite understood how to assign a value to | |

| I feel I was certainly able to do this prior to the class, but only through qualitative means. I could explain why something would likely be either an improvement or detriment, but was unable to definitively prove it, or back it up with quantitative measurements | |

| BPS ‘allowed us to provide quantitative results for theoretical scenarios for our designs that would otherwise be impossible’ | |

| Distinctions between the BPS model and the ‘truth’ | |

| Understood that output is a clue but not the truth | My original idea of simulation was that they were concrete and ‘right’ but I have come to realize they are just a tool to take advantage of to get a better understanding |

| The digital model may not be perfectly accurate | |

| Simulations may not be an exact correlation to reality, but they are still representative of reality enough to inform our design decisions | |

| The natures of testing with BPS | |

| Open-ended testing | Previously when designing, I would always use whatever option seemed best and go with the first choice, but I now understand how simple it can be to run a few tests |

| Frequently used terms: ‘test,’ ‘explore,’ ‘play with,’ ‘experiment’ | |

| There is no single optimal solution | |

| Semi-structured testing | Frequently used terms: ‘design choices,’ ‘options,’ ‘iterations,’ ‘combinations,’ ‘comparative,’ ‘endless simulations,’ ‘constantly adjusting different design aspects’ |

| STUDENT CONCEPTUALIZATIONS OF FUTURE BPS USE | |

| BPS as a tool for broader change | |

| Understanding of architects’ roles in impacting energy use with BPS | I felt reassured that I was an architecture major because I thought that this meant I would be able to be a part of the step towards building sustainably |

| I feel more empowered to factor in the energy demands of a design early on and to think through the consequences of design decisions in real time | |

| BPS for decision-making and argumentation in future design | |

| A way of developing understanding | I was able to execute different analyses that helped me better understand what factors impact a building more than others |

| I had no idea how powerful simulation could be towards making design decisions | |

| BPS ‘allowed me to make design decisions based off of more than just common sense and aesthetic quality as I had done before’ | |

| Tool to justify/rationalize decisions | I also enjoyed the ability to justify my design by the performance simulations. The form was designed to improve performance, but the performance [data] also gave merit to the design |

| Having sufficient data to support your claims can only help solidify why you made those decisions and how to further improve upon them | |

| BPS ‘transforms my opinions into arguments’ | |

| Tool to shift decisions | Simulations can help to either support or contradict your proposal |

| A great tool to nudge you in the right direction | |

4.1 Student perceptions of themselves and their knowledge

This course helped shape students’ emerging concepts of themselves and their knowledge as designers, as evidenced by their reflective statements. BPS project work allowed students new insights into building–energy relationships. Some students cited a deeper understanding of the envelope (and specifically its constituent glazing, insulation, and assemblies); others of building systems. Some attributed this understanding to new attentional focus. Many described demonstrating their deepened understanding linguistically or narratively; many others visually or graphically; and some noted now situating understanding in a broader context.

Many students mentioned a deeper appreciation for the interdependent and contingent ways building performance relates to architectural decisions about a building’s geometry, materials, and systems. While similar to the broader understanding of the building–energy relationships described above, some students specifically referenced how their choices as designers affect these relationships, and their awareness of trade-offs among performance dimensions due to design decisions. Some students emphasized the aggregate impact of individual choices; others an expanded design intuition about energy and buildings.

About half the students expressed some confidence in using BPS; more specifically, many expressed confidence in using the software to conduct studies, and others simply that they were now less intimidated to do so. Several attributed their greater confidence to a deepened understanding of energy and systems; others to a greater ability to communicate effectively about design choices; and still others to their greater awareness of the importance of considering building performance in professional architectural practice.

About one-third of students acknowledged room for further growth with BPS. Some felt that though they could run analyses, they had only ‘scratched the surface’ of larger topics. Many students acknowledged that while not experts, they had more knowledge than before. Several students wanted to use the software more before they could feel skilled. When students expressed reservations about their abilities to run specific analyses, these were more often about thermal than daylighting or radiation analyses.

4.2 Student perceptions of BPS as a design tool

Close examination of student reflections also indicates how they constructed understandings of BPS. Students frequently described BPS as producing useful visual information; others described a tool that yields quantitative and numerical outputs. Most students were new to BPS and found their preconceptions shifted from a presumption of BPS’s correctness or ‘truth’ toward a presumption of provisionally useful input for design consideration. Some students conceptualized BPS as a tool for open-ended experimentation; others saw its utility in semi-structured testing for improvement or optimization.

Many students’ responses contained indications of their subjective experiences with BPS; far more expressed positive sentiment than negative. Many students voiced positive feelings about gaining skills and confidence with new software; a few appreciated leveraging a familiar tool (here, Rhino). Many positive descriptions involved experimenting, exploring, or ‘playing’ with designs; for some, a positive experience related to the tool’s ease of use. Several mentioned delight in seeing improvements from experimentations; a few noted the joy of the work’s inherent challenges. Where students mentioned specific analytical processes positively, they almost always referred to lighting or radiation analyses; some alluded to the importance of lighting to occupants or architecture more broadly; others saw a utility in lighting/radiation studies for future employment. However, student sentiment was not all positive. Particularly unpopular was the time-consuming nature of the assigned work: students described feeling overwhelmed, particularly at the semester’s start. Some students specifically described thermal energy analyses in negative terms as difficult, abstract, or tedious; others commented on the challenge and frustration inherent in geometry construction.

4.3 Student conceptualizations of future BPS use

Some students found BPS work empowering, opening their eyes not only to the magnitude of building energy consumption but also to the role professional architects might play in mitigating energy consumption. When describing intentions for future BPS use, students described analysis execution, decision-making, and argumentation. Many students described BPS analysis as a vehicle for developing design understanding; some as an instrument to justify or rationalize design decisions; still others as an impetus to shift a design proposal.

Nearly three-quarters of students expected or hoped to use budding BPS skills in future professional work; some noted a competitive job-seeking edge; others mentioned advantages for future client communication; several observed the utility for practice of quick and easy analyses. A small subset of students working in practice expressed an intention to share knowledge with their current employers. Many acknowledged that while they did not imagine themselves performing BPS in future, they better understood its utility within practice. Still others remarked that they had no intentions to use BPS in future practice.

Many described general intentions to use BPS (usually solar radiation or daylighting, if specified) in future academic studios or competitions, though typically absent the specificity characterizing descriptions of future professional work. A few students mentioned the utility of simulation early in design, and the advantages of evidence for decision-making.

5. Discussion

The themes emerging from students’ responses resonate with previous notions of BPS teaching, but provide new evidence for how intentions translate into student perceptions. This helps shed light on the research question gauging BPS’s utility within architectural education to cultivate students’ spatial-data sensemaking.

5.1 Student sensemaking with BPS

Taken in aggregate, the ways in which students described themselves as designers using BPS suggest they are using BPS to help make sense in early design. Students describe a deeper understanding of the interrelationship of buildings and energy; the development of such understanding is core to the idea of sensemaking as gap-bridging in one’s own knowledge (Dervin 1998), and as a process of examining and reformulating one’s pre-existing knowledge frames, and as extrapolating abstract knowledge from the specific (Klein et al. 2007). This finding is also echoed in the literature on BPS pedagogy: several instructors find that BPS is a useful teaching aid in cultivating a deeper understanding of the principles of physics as applied in buildings, as well as the development of design intuition in applying these principles to project design (Anderson 2014; Charles & Thomas 2009; Reinhart et al. 2012; Schmid 2008). The performer paradigm closely aligns with the framing of BPS as a tool supporting spatial-data sensemaking, the more so when students are framing the analysis process and directly leveraging the output in design decisions. This finding also suggests that the course structures around uncertainty management are sufficient to allow students to translate declarative to procedural knowledge in this case. Students are making new sense of information they had previously learned.

Notably some students specifically mentioned their greater ability to speak about their understanding after working with BPS, similar to the way Weick (1995) centers the narrative creation of sensemaking. Here, however, rather than Weick’s question: How can I know what I think until I see what I say?, or the designerly sensemaking question: How can I know what I think until I see what I make?, the operative question in spatial-data sensemaking is: How do I know what to make until I see what it does? Something indeed appears to change in students’ perceptions from working with BPS which facilitates thoughtful making.

5.2 Student sensemaking of BPS

Students understood BPS as a tool with specific features: for design communication, for visual learning, or for quantitative understanding. This reinforces the idea that sensemaking takes place once knowledge is externalized (Weick 1995). Each aspect is important epistemologically, for its relevance to the designer’s emerging understanding, rather than ontologically as a description of the world beyond the realm of the simulation process. Further to this point, many students parsed their descriptions of BPS outputs carefully, describing clues to the behavior of buildings, rather than as ‘truth’ as such. Also, students frequently described their BPS work with an open-ended language of experimentation, play or exploration, or a directional improvement or optimization, rather than an absolute language such as ‘pass’ or ‘fail.’ Students described actively prospecting for new data, what Pirolli & Card (2005) call ‘information foraging,’ and Russell et al. (1993) call ‘the search for representation’ around which new frames of understanding develop. Anticipating future work, students envisioned using BPS to aid understanding, cultivating results that challenge expectations, and providing a means to communicate. All these are arguably central to the surprises, new understandings, and communication thereof central to sensemaking. While many students described the utility of BPS in increasing understanding and consciousness about energy and buildings, there was little discussion about accuracy of the results. As scholars of sensemaking point out, the plausibility of information is more critical than the accuracy of it (Weick et al. 2014). Accuracy was actively managed through the structure of coursework; arguably this was successful in reducing students’ epistemic uncertainty.

5.3 Sensemaking around future BPS use

Students saw the specific role of BPS for architects during design, for both decision-making and communication; through such work they saw the potential for architects to have greater impact. The literature aligns with these points. The American Institute of Architects (2019) argues that while only a minority of its members use it, BPS is essential to building design and delivery and aims to grow its usage. Fernandez-Antolin et al. (2020) further suggest that the lack of BPS teaching in architecture programs creates a gap in their professional capacities for designing net zero buildings. However, it is acknowledged that professionals use BPS in plural ways, and that there is no singular approach needed to prepare them for professional work (Oliveira et al. 2017). An international survey of professionals found broad interest in increased training in architectural programs, ongoing professional development, and the development of professional services and fee structures for doing this work (Soebarto et al. 2015). Students with BPS knowledge are likely to have more capacity to perform and consume performance information when in practice.

5.4 Further research

As an initial qualitative study, the research objective was to reveal the set of relevant student perspectives triggered by a pedagogy; future research is warranted to assess quantitatively the prevalence of themes. While analysis of student tool proficiency and simulation accuracy is outside the scope of this paper (though assessed for students’ grades), correlating student expertise with perception presents another avenue for future investigations.

5.5 Applications for teaching

An important finding from this paper is that students engaged in spatial-data sensemaking with BPS; they developed new insight and deepened their intuition about buildings and energy. The course scaffolded learning on knowledge from previous coursework; course lectures were structured to illuminate the relationships of key review concepts to exemplar design processes. Learning outcomes included both declarative understanding of building-energy use and procedural BPS proficiency. However, the results in this paper underscore the role for teaching BPS to make sense of building–energy relationships, and only secondarily to build tool proficiency. This chimes with the broader purview of the ‘performer’ paradigm which Alsaadani & Bleil De Souza (2018) identify and to which others teaching in this paradigm aspire. Teaching to cultivate spatial-data sensemaking with BPS should influence software selection, the time investment in teaching and learning BPS input and output mechanics, and course requirement for BPS proficiency demonstrations.

Graphics were found to be essential for student sensemaking with BPS. As also seen in the literature, visualization of the results is often a critical element in the development of student understanding (Anderson 2014; Hamza & Horne 2007; LaVine 2001; Loukissas 2012; Peters 2018). Visualizing results is not simply a by-product of quantitative analysis; they are fundamental to the development of student understanding. That said, additional strategies to make more sense of visual results through parallel explorations with physical models, sensors, etc. can be explored.

Students further made sense of the BPS outputs when using them as a tool for design argumentation. As Weick’s words have been reinterpreted here, students rhetorically ask: How do I know what to make until I see what it does? Design argumentation is distinct from the validation of the performance of design, however. Students seemed to make less sense of their results when conceiving them as diametric tests of pass/fail, correct/incorrect, met/not met. Structuring course assignments to require narrative arguments will aid in student sensemaking with data. Furthermore, closer integration of BPS with studio coursework could engage students in sensemaking activities during more phases of design. A further integration of BPS across all levels of the architectural curriculum could develop a computation-facilitated sensemaking process far beyond that discussed in this paper, but aligned with the integration of other computational design assistance tools (e.g. CAD, building information modelling (BIM)) in architectural education.

To students, trust in BPS software goes beyond having a robust computational engine. Tools need to have a robust graphic interface, to produce consistent outputs for consistent inputs, be sensitive to changes in input, resist crashing, and perform as expected relative to saving and re-opening work. Seemingly small bugs were frustrating and alienating to some students. For example, a software quirk wherein modified library files of new material assemblies were unavailable upon re-opening a model created an unforeseen barrier to students’ understandings about envelope performance modifications. For learning and sensemaking to take place, students must have trust not only in their results but also confidence in the BPS tool itself.

5.6 Study limitations

It is important to note some limitations to these findings. The work reported upon reflects two years of data from a course. (These data are from the second and third years the course was taught; data were not collected in the first year.) Students produced reflections as an end-of-term assignment; while papers were marked for completion and clarity, students may have perceived an incentive to write positively for a graded assignment. That having been said, the nature of the reflection was self-directed and not evaluative of the course.

6. Conclusions

Design can be seen as a process of sensemaking; and design with quantitative data is a more particular form of sensemaking, provisionally termed ‘spatial-data sensemaking.’ This important process is at work when understandings about energy and carbon influence the design of a building to respond to the climate emergency. Acquiring performance data is insufficient on its own, but use of building performance simulation (BPS) can cultivate sensemaking with those data. However, the inherent epistemic uncertainty of student-produced information must be carefully managed to avoid making sense of incorrect data, or literally making non-sense. Making sense of performance information means that it is so deeply absorbed that it becomes embedded within one’s design decision-making; the declarative becomes procedural in design. Whether students have made sense of information cannot be judged well simply by examining project designs or analyses, which may achieve good results without this deep understanding and not build learning for subsequent high-performance design. Students themselves must reflect on these actions.

In this paper, a teaching approach that uses BPS to cultivate designers’ spatial-data sensemaking is presented and analysed for its ability to be perceived as such among aspiring architects. Examining student reflection upon BPS work clarifies what transpires during their earliest design processes; student narratives indicate that BPS usage indeed deepened their intuitive knowledge upon which future design decisions could be made, and was perceived as a useful tool for testing and experimentation with the ability to nudge design decision-making even without certain or precise results. This finding suggests further research into sensemaking in design more broadly and calls for the development of further teaching strategies to encourage architecture students’ spatial-data sensemaking.

Notes

[1] For example, see the National Architectural Accrediting Board’s 2020 Conditions and Procedures, which requires in Program Criteria 3 that a program ‘instils in students a holistic understanding of the dynamic between built and natural environments, enabling future architects to mitigate climate change responsibly’; https://www.naab.org/accreditation/accreditation-criteria (accessed on August 20, 2024).

Acknowledgements

The author gratefully acknowledges the collaborations with Mike Tillou (2021) and Amir Rezaei (2023) in delivering the described curriculum; the assistance of graduate students Sneha Arikapudi (2021), Nicole Sarmiento (2022), and Tareq Naim Ogleh Nusair (2023) in course administration; and the tenacious effort by University at Buffalo architecture students in productively grappling with new ideas and methods.

Author contributions

The author was solely responsible for conceiving, writing, and editing this manuscript.

Competing interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

Data accessibility

The reflection data are not publicly available due to confidentiality assurances provided to the subjects.

Ethical approval

This study’s materials were reviewed and approved by SUNY University at Buffalo institutional review board (IRB), and were determined on April 12, 2023 to be exempt according to 45 CFR Part 46.104.