The crisis in Ukraine, caused by ongoing military actions, has created unprecedented challenges for children's mental health.

Preschool-aged children, being among the most vulnerable groups, require stability and emotional support from adults. Monitoring experience has confirmed that parental involvement is a key factor in the psycho-emotional development and stability of the child.

In response to limited access to education, the “2 by 2” model was introduced—combining offline meetings with educators and active parental engagement at home. This approach compensates for disrupted access to early childhood education and strengthens emotional bonds within the family.

The third wave of monitoring involved 3,820 parents across eight regions. The study focused on the impact of parenting practices on the development of emotional intelligence: the child’s ability to recognize, express, and regulate emotions and cope with stress. Children receiving responsive support exhibit lower levels of anxiety and greater stress resilience.

Most parents demonstrated empathy and used language of encouragement and praise. However, only 15.6% regularly practiced body-oriented techniques, 20.9% engaged in emotional play, and more than one-third responded inconsistently to their children's fears.

The “2 by 2” model, supported by UNICE, provided parents with access to practical resources—such as diaries, guidelines, and games—which increased parental awareness and helped reduce children's anxiety.

Monitoring clearly showed that parental emotional presence is a critical resource for stabilizing a child’s mental state. Systematic family engagement in the educational process should become a priority in national policy under crisis conditions.

The aim of the study is to examine the relationship between parental emotional socialization practices and the psycho-emotional state of preschool-aged children under conditions of armed conflict, based on data from the third wave of monitoring conducted within the framework of the “2 by 2” model in front-line regions.

- –

To assess the level of parental emotional involvement in daily interactions with children under conditions of stress and instability.

- –

To determine the prevalence of supportive practices, including discussing emotions, teaching self-regulation skills, practicing breathing exercises, accepting negative emotions, encouraging effort-based praise, and modeling emotionally open adult behavior.

- –

To identify barriers such as emotional exhaustion, lack of knowledge, limited resources, and prevailing stereotypes.

- –

To analyze the role of parents as primary regulators of emotional safety and carriers of coping strategies in the context of restricted access to early childhood education institutions.

- –

To confirm the need for systematic parental support and the enhancement of emotional competence.

- –

To use the findings to advocate for policy changes: implementing family support programs, integrating the foundations of emotional intelligence into early childhood education, and fostering educator–parent partnerships.

The parental survey was conducted from April 1 to April 28, 2025, with 3,820 respondents from the Dnipropetrovsk, Zaporizhzhia, Mykolaiv, Odesa, Poltava, Sumy, Kharkiv, and Kherson regions. The questionnaire was designed to collect empirical data within the framework of multilevel monitoring aimed at studying the development of the emotional domain, self-esteem, and stress resilience in preschool-aged children.

The respondents were parents of children aged 3 to 6 years.

The questionnaire consists of seven consecutive sections:

Section 1 – Introduction/Instructions (explains the purpose and provides brief guidance on how to complete the form).

Section 2 – Demographic information (includes region, personal data about the parents).

Section 3 – Emotion recognition. Section 4 – Emotion expression.

Section 5 – Parental modeling.

Section 6 – Support for emotional development.

Section 7 – Stress coping skills.

Sample Structure of Children by Age, Gender, and Disability Status

| Age | Quantity | Of which: boys | Of which: girls | Children with disabilities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Third year of life | 651 | 333 | 318 | |

| Fourt year of life | 1172 | 610 | 562 | |

| Fifth year of life | 1262 | 638 | 624 | 15 |

| Sixth year of life | 685 | 320 | 343 | 22 |

| Seventh to eighth year of life | 72 | 31 | 41 | 35 |

| Total | 3842 | 1932 | 1888 | 72 |

The assessment covered both cognitive (awareness and understanding of emotions) and behavioral (adult responses to children's emotions) components, offering a comprehensive view of parenting practices. These elements correlated with monitoring data on emotional development, self-esteem, and stress resilience in children whose parents participated in the third wave of the “2 by 2” model (five months).

Findings from parent surveys and child assessments revealed a clear link between parental support and emotional skill development. The study analyzed play frequency, use of body-oriented techniques, and responses to negative emotions (fear, aggression, anxiety). A pilot test (57 respondents, March 2025) helped refine the questionnaire.

To ensure data reliability, parental responses were aligned with pedagogical observations. A systemic approach, grounded in clear developmental criteria, is essential for timely identification of difficulties and planning support.

A multilevel monitoring model was developed across five domains: emotional (8 indicators), social interaction (8), cognitive (38), self-esteem (8), and stress resilience (8), totaling 70 indicators. These domains are interrelated; for example, chronic stress may impair cognition and reduce resilience (Kosenchuk & Tarnavska, 2023).

The analysis also included the role of play in emotional stability, family-based relaxation practices, and the influence of adults’ experiences on children’s emotional competence. Ontogenetically based criteria enabled adaptation to individual needs and informed decision-making on the type and intensity of support.

Methods were adapted to the cultural context and applicable in both formal and alternative educational formats. Quantitative (surveys) and qualitative (observations, children’s work, expert reviews) methods were used.

Observations in natural settings followed standardized scales, ensuring authenticity. Children’s activities were analyzed during classes and play. Data were processed in Google Sheets, with individual scores averaged and classified as low (0–0.3), medium (0.4–0.7), or high (0.8–1). Results allow tracking development at child, institution, and community levels, supporting targeted parental programs.

Based on the data obtained through multilevel monitoring, an optimized system for the education, upbringing, and development of foundational emotional intelligence in preschool-aged children was proposed. This system employs a systemic approach and incorporates methodological algorithms (Kosenchuk, Tarnavska, Shytikova, Shulha, Karapuzova, & Kovalevska, 2025).

The statistical data refer to the period during which children attended educational settings from February to April 2025. The results of child development monitoring and parental surveys were collected concurrently, allowing for the correlation of parental influence on children’s emotional state and emotional intelligence skills with their interactions with educators and the implementation of the program “Caring for Emotions — The Language of the Heart” (targeted at middle and senior preschool age groups) (Kosenchuk & Tarnavska, 2024a; Kosenchuk & Tarnavska, 2024b).

The influence of parental behavior on children's psycho-emotional state in crisis conditions was assessed based on developmental indicators from two waves of multilevel monitoring. A deeper analysis of the relationship between parental emotional involvement, awareness, and practical use of emotional intelligence methods proved highly relevant. The study identified key forms of emotional support in families, such as the frequency of discussing emotions, parents’ ability to recognize children's emotional states, and their responses to fears and tantrums—all of which directly affect children’s anxiety levels, self-confidence, and emotional stability.

While educators interact with children 6 to 12 hours per week, parents engage daily and across diverse contexts. For young children, natural imitation of parental behavior highlights the family's central role in shaping emotional development. Parents serve as primary attachment figures, forming the most influential emotional bond and acting as models for social learning (Bandura, 1977).

Combining parent surveys with pedagogical observations helped identify gaps in adults' understanding of children's emotional needs, often rooted in personal experiences, limited knowledge, or difficulties in emotional response. Comparative analysis clarified effective support strategies both in families and in preschool settings operating under the “2 by 2” model and revealed additional resources needed for child development.

Limitations such as socially desirable responses, varying interpretations of terms, the impact of war, and subjective pedagogical evaluations were considered. There is also a potential bias due to educators' desire to report positive outcomes.

The study is grounded in the ontogenetic approach, with all criteria aligned to age norms and developmental regularities of preschool children, ensuring the validity and reliability of the dynamic assessment.

This approach enabled:

Identification of individual developmental delays by comparing children's behavior and emotional responses to age-typical patterns;

Detection of parental and child needs arising from crisis conditions (e.g., armed conflict) through observation of gaps in emotional intelligence, self-esteem, and stress resilience;

Adaptation of educational strategies to match both developmental stages and critical periods of emotional sensitivity, ensuring stable emotional relationships.

Thus, the ontogenetic framework provided scientifically valid criteria and allowed for both quantitative and developmental interpretation of results—clarifying each child’s trajectory and the conditions that facilitate or hinder their progress.

To assess the level of parental involvement in the emotional development of children, a survey was conducted with the participation of 3,820 respondents. Participants were invited to answer questions aimed at evaluating the extent to which emotional interaction and emotional upbringing are integrated into daily family communication.

The survey results are presented below in the form of charts and tables to facilitate visual analysis.

Question 1. Do you talk to your child about their emotions?

Total responses: 3,831

Yes - 74,4 %

Sometimes - 23%

Rarely 2,3%

Never 0,3%

Distribution of responses to Question 1: Do you talk to your child about their emotions?

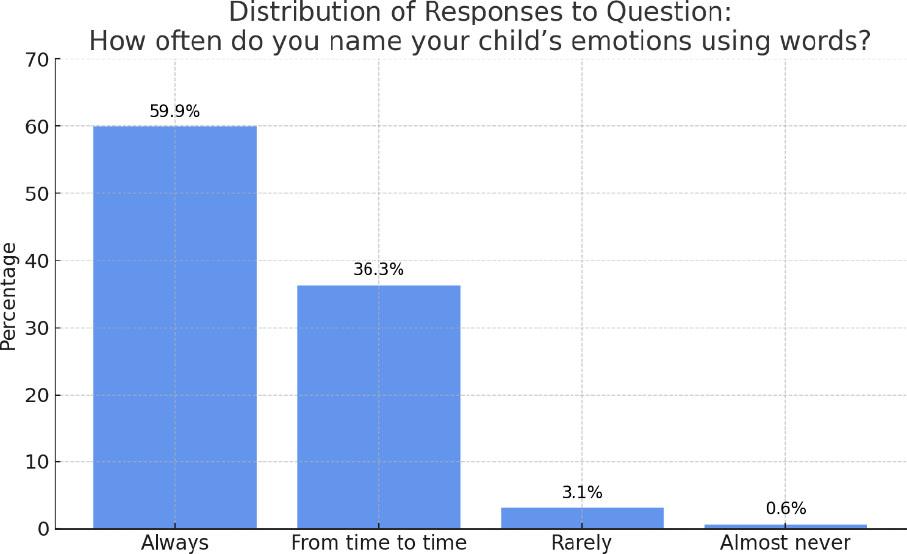

Question 2. How often do you name your child’s emotions using words (e.g., "You look upset," "I see you’re happy," "You're angry right now")?

Always - 59,9%

From time to time - 36,6%

Rarely - 3,1%

Almost never - 0,4%

Distribution of responses to Question 2: How often do you name your child’s emotions using words (e.g., "You look upset," "I see you’re happy," "You're angry right now")?

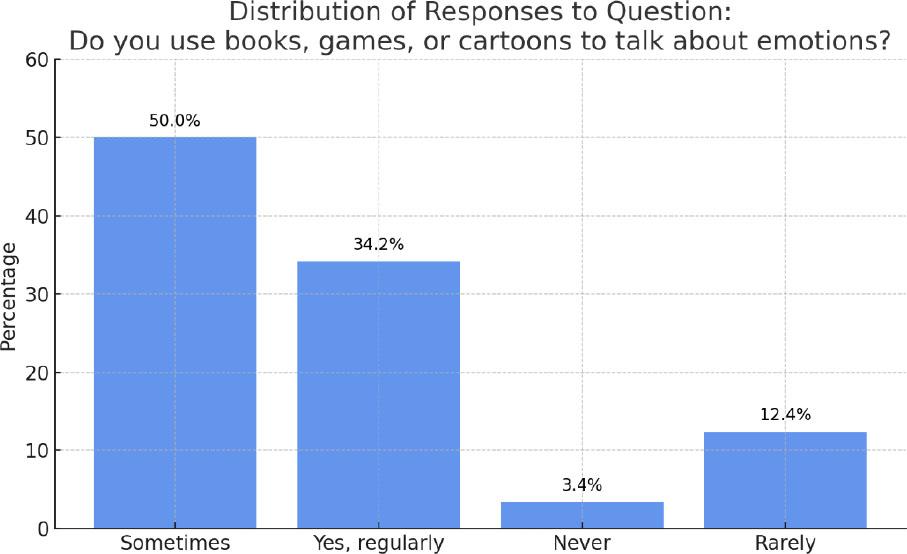

Question 3. Do you use books, games, or cartoons to talk about emotions?

Yes - 34,1%

Sometimes - 50%

Rarely 12,5%

Never - 3,4%

Distribution of responses to Question 3: Do you use books, games, or cartoons to talk about emotions?

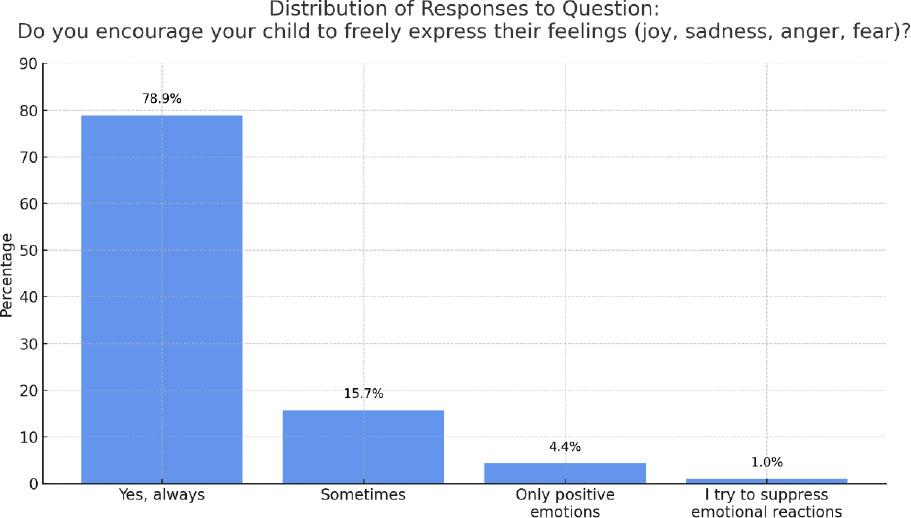

Question 4. Do you encourage your child to freely express their feelings (joy, sadness, anger, fear)?

Yes - 78,9%

Sometimes - 15,7%

Only positive emotions - 4,4 %

I try to suppress emotional reactions- 1,0 %

Distribution of responses to Question 4: Do you encourage your child to freely express their feelings (joy, sadness, anger, fear)?

Question 5. How do you respond when your child is angry or cry

I help them understand the cause and calm down - 82,9%

I distract their attention - 14,7%

I tell them such feelings should not be expressed - 1,9%

I ignore it - 0,5 %

Distribution of responses to Question 5: How do you respond when your child is angry or crying?

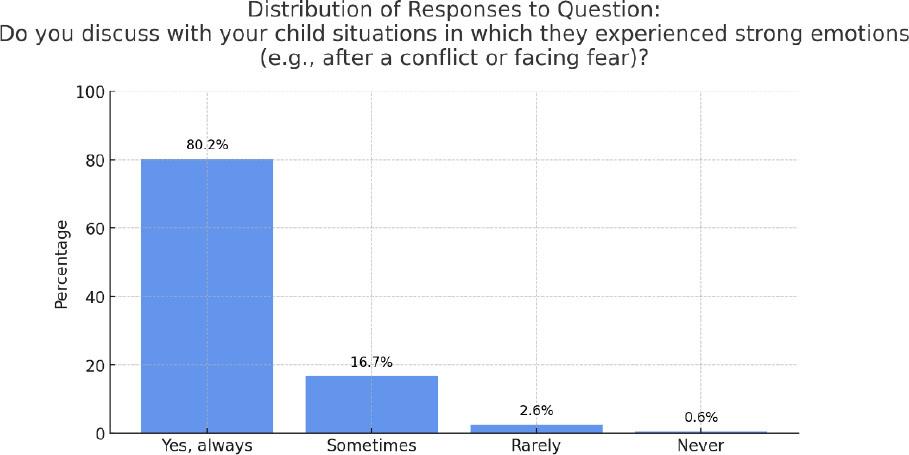

Question 6. Do you discuss with your child situations in which they experienced strong emotions (e.g., after a conflict or facing fear)?

Yes, always - 80,2%

Sometimes - 16,7%

Rarely - 2,6%

Never - 0,6 %

Distribution of responses to Question 6: Do you discuss with your child situations in which they experienced strong emotions (e.g., after a conflict or facing fear)?

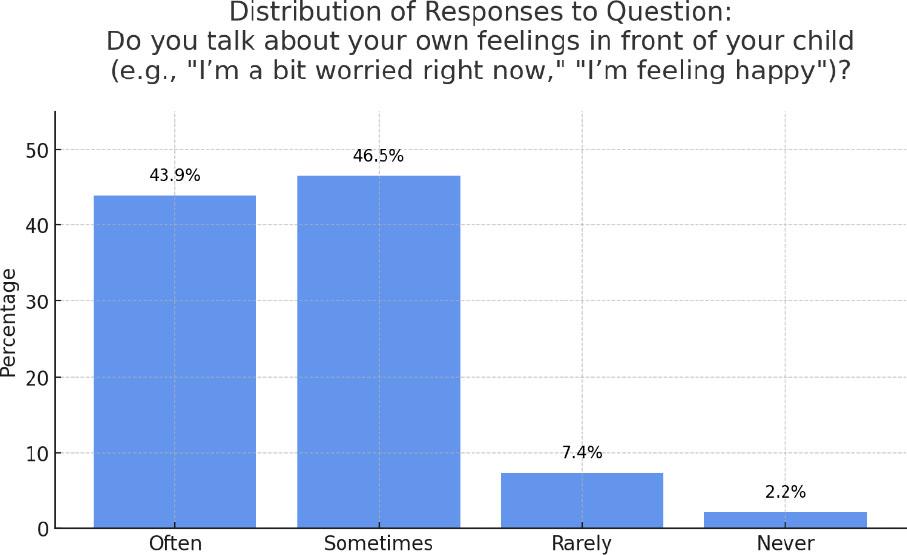

Question 7. Do you talk about your own feelings in front of your child (e.g., "I’m a bit worried right now," "I’m feeling happy")?

Often - 43,8%

Sometimes - 46,6%

Rarely - 7,4%

Never - 2,2%

Distribution of responses to Question 7: Do you talk about your own feelings in front of your child (e.g., "I’m a bit worried right now," "I’m feeling happy")?

Question 8. How do you respond when you experience strong emotions in front of your child?

I openly talk about my feelings and explain them - 54%

I try to hide my emotions - 22,5%

I say everything is fine, even if it’s not - 21,8%

I express emotions uncontrollably - 1,4%

Distribution of responses to Question 8: How do you respond when you experience strong emotions in front of your child?

Question 9. Do you play games with your child that help recognize and express emotions (e.g., “act out an emotion,” “what is the character feeling?”)?

Yes, often - 20,9%

Sometimes - 47,1%

Rarely - 22,7%

Never - 9,2%

Distribution of responses to Question 9: Do you play games with your child that help recognize and express emotions (e.g., “act out an emotion,” “what is the character feeling?”)?

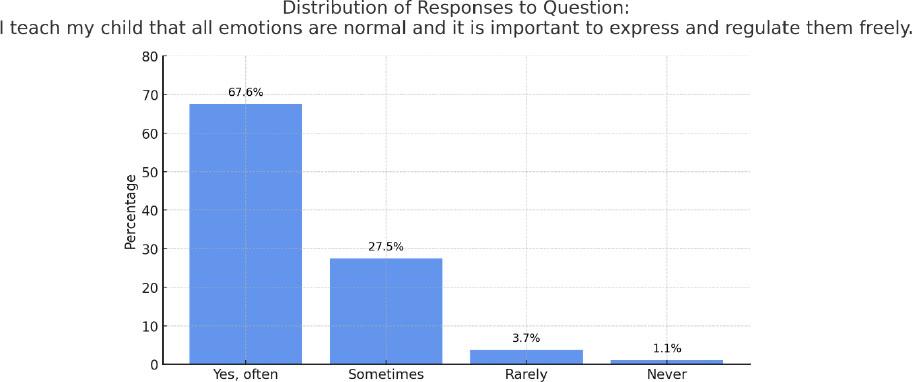

Question 10. I teach my child that all emotions are normal, and it is important to express and regulate them freely.

Yes, often - 67,7%

Sometimes - 27,5%

Rarely - 3,7%

Never - 1,1%

Distribution of responses to Question 10: I teach my child that all emotions are normal and that it is important to express and regulate them freely.

Question 11. Do you use relaxation techniques or breathing exercises to help your child calm down?

Yes, regularly - 15,6%

Sometimes - 38,1%

Rarely - 24%

Never - 22,3%

Distribution of responses to Question 11: Do you use relaxation techniques or breathing exercises to help your child calm down?

Question 12. I explain that failures are a part of life and they help us learn.

Yes, regularly - 73,3%

Sometimes - 21,7%

Rarely - 3,4%

Never - 1,6%

Distribution of responses to Question 12: I explain that failures are a part of life and they help us learn.

Question 13. We talk together about how to cope with fears and anxieties.

Yes, regularly - 64,5%

Sometimes - 28,1%

Rarely - 5,6 %

Never - 1,8%

Distribution of responses to Question 13: We talk together about how to cope with fears and anxieties.

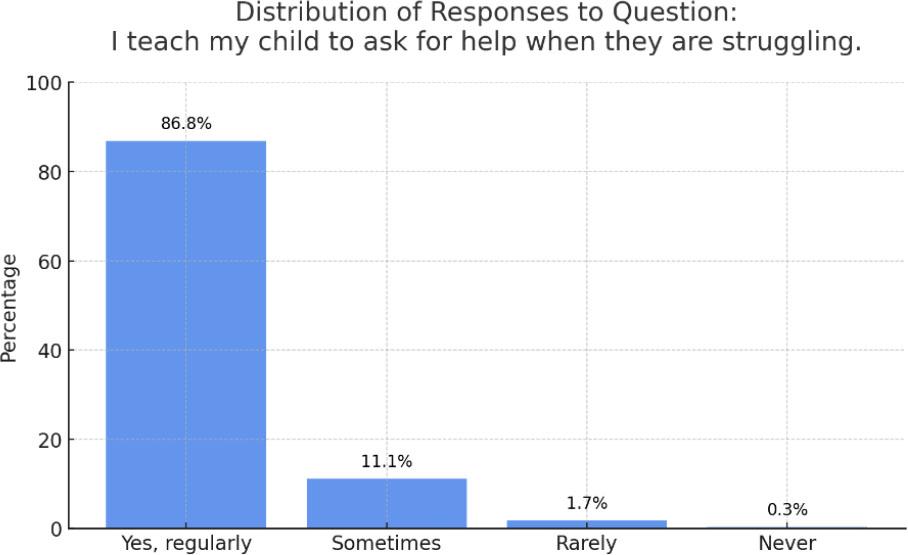

Question 14. I teach my child to ask for help when they are struggling.

Yes, regularly - 86,8%

Sometimes - 11,2%

Rarely - 1,7%

Never - 0,3 %

Distribution of responses to Question 14: I teach my child to ask for help when they are struggling.

Question 15. I praise my child for their efforts to cope with difficult situations and acknowledge their strengths.

Yes, regularly - 93,1%

Sometimes - 6,4%

Rarely - 0,3%

Never - 0 %

Distribution of responses to Question 15: I praise my child for their efforts to cope with difficult situations and acknowledge their strengths.

The primary aim of the analysis is to identify the relationship between parenting practices and the psycho-emotional development of children aged 4–6 under conditions of armed conflict. Parental surveys and child assessments were conducted simultaneously (April 1–28, 2025).

The first section of the questionnaire, “Emotion Recognition,” focuses on practices that foster emotional awareness, labeling of emotions, empathy, and self-regulation. Questions addressed whether parents talk to their children about emotions, how often emotions are verbalized, and the use of books, games, or cartoons for emotional learning. The following is an interpretation of the results:

Question 1. Do you talk to your child about their emotions?

A total of 74.4% of parents reported doing so regularly, indicating a high level of emotional involvement. Another 23% do so occasionally, suggesting openness but a lack of consistency. Only 2.3% rarely engage in such conversations, likely due to a lack of knowledge or confidence. A minimal 0.3% never discuss emotions with their child, pointing to the absence of such a model in their own upbringing. (See Diagram 1).

The connection between parental and child outcomes is clear: a high level of parental involvement—74.4% of parents regularly talk to their children about emotions—contributed to a notable improvement in the child indicator “Recognizes and names own emotions,” which increased from 0.25 to 0.61 between February and April (see Table 2).

Results of monitoring the development of emotional domain, self-esteem, stress resilience, and related indicators in preschool children (February – baseline/interim, March – interim, and April – interim 2025)

| Key developmental domains (criteria) | Child development indicators | February – baseline | February – interim | March – interim | April – interim |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Development of the emotional domain | 1. Perceives their emotions as natural and important | 0,34 | 0,51 | 0,58 | 0,62 |

| 2. Understands how appropriately their expressed emotions match the situation and context | 0,32 | 0,52 | 0,58 | 0,61 | |

| 3. Knows that it is not necessary to be ashamed of expressing one’s own emotions | 0,41 | 0,51 | 0,55 | 0,56 | |

| 4. Recognizes and names their emotion | 0,25 | 0,52 | 0,58 | 0,61 | |

| 5. Shows a tendency to restrain emotional expressions when necessary | 0,25 | 0,51 | 0,56 | 0,60 | |

| 6. Accepts that other people experience different emotional states | 0,34 | 0,52 | 0,57 | 0,61 | |

| 7. Is able to empathize and show compassion | 0,36 | 0,53 | 0,58 | 0,62 | |

| 8. Demonstrates emotional readiness to interact with others | 0,37 | 0,53 | 0,57 | 0,61 | |

| Formation of positive self-esteem | 1. Perceives themselves positively | 0,39 | 0,53 | 0,58 | 0,72 |

| 2. Displays confidence in their abilities | 0,29 | 0,52 | 0,56 | 0,60 | |

| 3. Demonstrates willingness to accept others as they are | 0,29 | 0,52 | 0,53 | 0,58 | |

| 4. Shows a tendency to differentiate actions and their consequences according to the situations occurring | 0,27 | 0,51 | 0,56 | 0,61 | |

| 5. Responds appropriately to situations and actions of adults and peers, adhering to social norms and accepted rules of conduct within the community | 0,29 | 0,52 | 0,57 | 0,62 | |

| 6. Supports cooperation with others and participates in creative and cooperative play | 0,33 | 0,52 | 0,57 | 0,61 | |

| 7. Understands and accepts the need to negotiate roles and rules of interaction, share toys, support one another, and so on | 0,29 | 0,52 | 0,56 | 0,61 | |

| 8. Recognizes situations in which they feel insecure and reflects on how to overcome them | 0,21 | 0,51 | 0,55 | 0,60 | |

| Stress resilience | 1. Demonstrates the ability to cope with difficulties and stressful situations | 0,20 | 0,49 | 0,55 | 0,59 |

| 2. Recognizes states of anxiety, worry, internal tension, and similar feelings | 0,24 | 0,49 | 0,55 | 0,59 | |

| 3. Knows simple techniques to manage worry and calm down | 0,21 | 0,40 | 0,51 | 0,52 | |

| 4. Demonstrates the ability to adapt to new situations and changes, effectively cope with challenges, and recover from setbacks | 0,21 | 0,50 | 0,55 | 0,58 | |

| 5. Possesses basic self-regulation skills in challenging situations, such as waiting for their turn and restraining impulsive behaviors and actions | 0,23 | 0,50 | 0,54 | 0,59 | |

| 6. Is able, according to age-specific characteristics, to distinguish disappointment, despair, fear, depression, etc., and demonstrates skills in regulating these emotions | 0,24 | 0,50 | 0,54 | 0,59 | |

| 7. Expresses their needs, desires, and feelings verbally without resorting to tantrums or other destructive behaviors | 0,27 | 0,51 | 0,57 | 0,61 | |

| 8. Adheres to social norms and rules such as saying “please” and “thank you,” taking turns in conversation, respecting others’ personal space, and so on | 0,36 | 0,53 | 0,58 | 0,62 | |

Question 2. How often do you label your child’s emotions with words?

A total of 59.9% of parents reported doing so consistently, indicating strong awareness of the role of verbalization. Another 36.6% do so occasionally, reflecting a less structured approach. Only 3.1% rarely label emotions, likely due to low emotional literacy, while 0.4% almost never do so, suggesting limited awareness in this area (see Diagram 2).

Parental verbalization of emotions is closely linked to the child indicator “Perceives own emotions as natural and important.” The increase in this indicator from 0.34 to 0.62 between February and April (see Table 2) demonstrates positive dynamics; however, the overall level remains within the medium range.

Question 3. Do you use books, games, or cartoons to discuss emotions?

A total of 34.1% of parents do so regularly, indicating a deliberate use of narrative materials in emotional education. Another 50% use such resources occasionally, reflecting interest but a lack of consistency. About 12.5% rarely apply these tools, possibly due to limited understanding of their benefits or difficulty identifying characters' emotions. Finally, 3.4% never use them, suggesting a significant lack of knowledge in this area (see Diagram 3).

Overall, the results indicate limited consistency in the use of books, games, and cartoons for discussing emotions among parents. Only 34.1% regularly use these tools as part of emotional education, reflecting a conscious and targeted effort to engage children through visual and narrative materials. The child indicator “Demonstrates willingness to accept others as they are” increased from 0.29 to 0.58 between February and April (see Table 2), reflecting a moderate level of skill development.

The second section of the questionnaire explores how parents respond to their child’s emotions and whether they foster an environment for open emotional expression. Questions addressed encouragement of emotional openness, parental reactions to anger, tears, and fear, as well as discussions of emotionally charged situations. The results reveal a range of parental strategies—from emotional support and open communication to avoidance, dismissal, or excessive control. The interpretation of findings is presented below:

Question 4. Do you encourage your child to freely express their feelings (joy, sadness, anger, fear)?

A total of 78.9% of parents encourage open emotional expression, indicating support for emotional openness, trust, and the child’s ability to explore and experience a full range of emotions. Another 15.7% do so occasionally, suggesting partial support and possible difficulties in accepting intense emotions. About 4.4% allow only positive emotions to be expressed, which may lead to the suppression of negative feelings, often due to a lack of understanding of children's emotional processes. Finally, 1.0% try to suppress emotional reactions, likely due to discomfort with rapid emotional shifts or the perception that the child is unresponsive to adult guidance (see Diagram 4).

Although 78.9% of parents reported encouraging children to freely express their emotions, the child indicator “Knows that expressing one’s emotions is nothing to be ashamed of” increased only moderately from 0.41 to 0.56 between February and April (see Table 2), without reaching a high level. This suggests that in practice, parents may primarily support the expression of positive emotions, while negative ones (such as sadness, anger, or fear) are often suppressed. It is possible that parents overestimate their level of support, equating the absence of prohibitions with active encouragement to experience the full emotional spectrum. A critical aspect is often overlooked: all emotions—both “pleasant” and “unpleasant”— are natural and require expression. These findings highlight the need for deeper work with parents on emotional acceptance and communication.

Question 5. How do you respond when your child is angry or cries?

A total of 82.9% of parents reported helping their child understand the cause of the emotion and calm down, indicating a high level of sensitivity and support during intense emotional experiences. Another 14.7% distract the child’s attention to relieve tension, which may reduce emotional stress but does not always promote deeper emotional understanding. About 1.9% believe certain emotions should not be expressed, often reflecting traditional views on “negative” emotions or fear of uncontrollable behavior. Finally, 0.5% do not respond to the child’s emotions, indicating low parental involvement (see Diagram 5).

82.9% of parents demonstrate support during their child’s intense emotional experiences, which correlates with the positive dynamics of the child indicator “Demonstrates age-appropriate ability to differentiate between disappointment, despair, fear, and sadness, and to regulate these emotions.” which increased from 0.24 to 0.59 between February and April (see Table 2). Parents’ high self-assessment of their emotional sensitivity (82.9%) may reflect actual emotional socialization practices as well as a heightened desire to be a source of stability during wartime. In crisis conditions, parents tend to focus more on their child’s emotions—even if they had not done so previously—or may slightly overestimate the extent of their support.

Question 6. Do you talk with your child about situations in which they experienced strong emotions (e.g., after a conflict or a fearful event)?

A total of 80.2% of parents reported always discussing such emotional experiences with their child, indicating an understanding of the importance of reflection for emotional intelligence development. Another 16.7% do so occasionally, likely due to time constraints or lack of confidence. About 2.6% rarely revisit their child’s emotions, which may reflect avoidance or a lack of awareness about the value of emotional support. Finally, 0.6% never engage in such discussions, suggesting emotional distancing, low involvement, or adherence to a model of emotional avoidance (see Diagram 6).

80.2% of parents consistently discuss situations involving strong emotions with their child, which supports the development of emotional reflection and awareness of internal states. Through this, children learn to revisit events, analyze their experiences, and recognize feelings such as anxiety, tension, and excitement. However, the child indicator “Demonstrates the ability to cope with difficulties and stressful situations” increased from 0.20 to 0.59 between February and April (see Table 2), but remains at a moderate level. This may suggest that such conversations are often superficial or spontaneous, focused more on events than on emotional states, or that parents overestimate the effectiveness of their communication.

The third section of the questionnaire examined how parents express emotions in interactions with their child and the example they set in emotional expression and regulation. Particular attention was given to parents' openness in discussing their own emotions as a means of fostering emotional reflection in children.

Question 7. Do you talk about your own feelings in front of your child?

A total of 43.8% of parents frequently share their emotions with their child, which contributes to the development of empathy. Another 46.6% do so occasionally, depending on the context. About 7.4% rarely speak about their feelings, possibly due to personal difficulties or beliefs. Finally, 2.2% never do so, reflecting emotional reticence or adherence to traditional views of adult roles (see Diagram 7).

Although most parents report being open about their emotions, fewer than half demonstrate this consistently. This likely explains why the child indicator “Accepts that other people experience different emotional states” increased only moderately from 0.34 to 0.61 between February and April (see Table 2). Children learn empathy not only through explanation but primarily through modeled behavior. A lack of emotional transparency from parents hinders the child’s ability to accept and respect others’ feelings, highlighting the importance of fostering emotional openness in adults.

Question 8. How do you respond when experiencing strong emotions in front of your child?

A total of 54% of parents openly share and explain their feelings, fostering empathy and emotional reflection in the child. Another 22.5% hide their emotions, fearing emotional overload or loss of authority. About 21.8% reassure the child that “everything is fine,” even when it is not, which hinders the child's ability to recognize subtle emotional cues. Finally, 1.4% react uncontrollably, setting a harmful example that may confuse or emotionally distress the child (see Diagram 8).

Parental emotional openness is directly linked to the child's ability to understand the appropriateness of their own emotions. In contrast, children of parents who conceal or deny their emotions (44.3%) receive inconsistent or unclear emotional signals. This corresponds with the moderate improvement of the indicator “Accepts that other people experience different emotional states,” which increased from 0.34 to 0.61 between February and April (see Table 2).

The fourth section examined how parents foster emotional intelligence in daily interactions, focusing on play, verbal guidance, and emotional reinforcement. It assessed practices of recognizing, expressing, and regulating emotions, as well as parents' awareness of play as a tool for emotional learning. Below is the interpretation of the results:

Question 9. Do you play games with your child that help recognize and express emotions (e.g., “show the emotion,” “what is the character feeling?”)?

20.9% of parents frequently engage in emotional games, recognizing their value in creating a safe environment where the child can experience complex emotions without real-world pressure. Another 47.1% do so occasionally, indicating partial awareness of the role of play as a space for emotional experimentation through role enactment. About 22.7% rarely use such games, likely underestimating their importance for emotional development, while 9.2% never play them, depriving the child of a safe outlet for emotional expression, which may hinder the development of emotional competence (see Diagram 9).

The use of games such as “Show the emotion” or “What is the character feeling?” has a direct impact on children’s emotional literacy, empathy, and self-regulation, particularly in crisis contexts. Among the 20.9% of parents who regularly engage in such play, a positive trend was observed in the indicator “Engages in cooperation with others, participates in creative and cooperative play,” which rose from 0.33 to 0.61 between February and April (see Table 2). However, 56.3% of parents do not use these games systematically, likely due to limited awareness of their role and importance— emphasizing the need for enhanced parental education.

Question 10. I teach my child that all emotions are normal and that it is important to express and regulate them freely.

A total of 67.7% of parents frequently teach their child that all emotions are natural and should be openly expressed and regulated, indicating high emotional awareness and a desire to create a safe emotional environment. Another 27.5% address this occasionally, likely recognizing its importance but lacking a consistent strategy. About 3.7% rarely discuss this topic, possibly due to limited understanding or personal experience with emotional suppression. Finally, 1.1% never address this issue, likely due to emotional avoidance or adherence to outdated models of emotional socialization (see Diagram 10).

A high level of parental awareness regarding the importance of an emotionally safe connection—where the child feels unconditional acceptance and can freely experience emotions—is evident among the 67.7% of parents who consistently teach emotional acceptance and regulation. This correlates with the development of the skill “Demonstrates basic self-regulation in challenging situations, such as waiting their turn or controlling impulsive behavior,” which increased from 0.23 to 0.59 between February and April (see Table 2). However, 32.3% of parents do not teach that all emotions are normal, which may hinder natural emotional development and weaken the child’s connection with their inner emotional experience.

The fifth section assesses how parents help children manage stress and difficult emotions, focusing on body-oriented practices, attitudes toward failure, openness to discussing worries, and seeking help. It evaluates parental support in building children’s emotional resilience, adaptive strategies, and self-regulation. Below is the interpretation of the results:

The questions in this section assess the level of parental support in developing a child's emotional resilience, adaptive strategies, and self-regulation. Below is the interpretation of the results for each item:

Question 11. Do you use relaxation techniques or breathing exercises to help your child calm down?

A total of 15.6% of parents regularly use relaxation methods, indicating a high level of awareness; 38.1% use them occasionally, showing potential for growth; 24% do so rarely, likely due to limited knowledge; and 22.3% do not use them at all, suggesting low awareness (see Diagram 11).

Only 15.6% of parents regularly use relaxation techniques or breathing exercises to help their child calm down. The presence of such practices in the family environment directly influences the child’s awareness of self-soothing strategies. Irregular or absent use of these techniques by 84.4% of parents results in a lack of consistent behavioral models for managing anxiety. The overall slow increase in the child indicator “Knows simple strategies to manage anxiety and calm down,” from 0.21 to 0.52 between February and April (see Table 2), can be attributed to the low frequency of regular parental practice and limited integration of body-based methods into daily interactions.

Question 12. I explain that failures are a part of life and help us learn.

A total of 73.3% of parents consistently promote a constructive attitude toward challenges, supporting resilience, adaptability, and a growth mindset (Dweck, 2006). Another 21.7% do so occasionally, reflecting limited understanding of mistakes as learning opportunities. About 3.4% rarely address failure, which may foster fear of mistakes and dependence on external approval. Finally, 1.6% never discuss this topic, possibly due to personal traumatic experiences, increasing the risk that the child will struggle to accept failure (see Diagram 12).

Regular parental explanation of the value of failure (73.3%) correlates with the positive trend in the child indicator "Demonstrates the ability to adapt to new situations and changes, cope effectively with challenges, and recover from setbacks," which increased from 0.21 to 0.58 between February and April (see Table 2).

Question 13. We talk together about how to cope with fears and anxieties.

A total of 64.5% of parents regularly discuss fears with their children, demonstrating high emotional sensitivity and supporting the development of emotional intelligence, self-regulation, and trust. Another 28.1% do so occasionally, providing situational but inconsistent support. About 5.6% rarely engage in such discussions, potentially ignoring children's fears and weakening emotional trust. Finally, 1.8% never address these topics, indicating a lack of open communication, which may increase anxiety and emotional tension (see Diagram 13).

Overall, most parents (64.5%) regularly discuss fears and anxieties with their children. These children are more likely to develop the ability to recognize their internal states—for example, to distinguish fear from sadness or disappointment from despair—and are better equipped to apply appropriate strategies for managing emotional tension. This correlates with growth in the indicator "Demonstrates the ability to adapt to new situations and changes, cope effectively with challenges, and recover from setbacks," which increased from 0.24 to 0.59 between February and April (see Table 2).

However, more than one-third of parents (35.5%) rarely or never talk with their children about how to cope with fears and anxieties. As a result, children are left alone with their emotions and lack opportunities to make sense of difficult feelings. Due to this inconsistent support, the overall level of the skill remains below the high threshold (0.7–1.0).

Question 14. I teach my child to ask for help when they are struggling.

A total of 86.8% of respondents answered “yes, regularly,” indicating an understanding of the importance of encouraging help-seeking behavior, which fosters the child’s confidence and meets their need to feel heard. Another 11.2% do so occasionally, reflecting a lack of consistency. About 1.7% rarely address this, likely due to the belief that children should cope independently—posing a risk of emotional isolation. Finally, 0.3% never teach this, which may instill the notion that asking for help is a sign of weakness (see Diagram 14).

Most parents (86.8%) regularly teach their child to ask for help, which supports the development of verbal communication during emotionally challenging situations. This reduces the likelihood of tantrums, aggression, or manipulative behavior as a means of seeking attention. It correlates with the growth of the indicator "Express needs, desires, and feelings verbally without resorting to tantrums or other destructive behavior," which increased from 0.27 to 0.61 between February and April (see Table 2). However, nearly one in ten families do so only occasionally or rarely, which may reflect a compensatory parenting model shaped by unresolved personal trauma.

Question 15. I praise my child for their efforts to cope with difficult situations and acknowledge their strengths.

A total of 93.1% of parents regularly support their child’s efforts, fostering motivation and self-confidence. Another 6.4% do so occasionally, likely due to inconsistency or restraint in giving praise. Only 0.3% rarely offer such feedback, possibly due to a focus on outcomes or fear of “spoiling” the child. Notably, 0% reported never doing so—all respondents recognized the importance of encouragement Regular praise for effort and strengths by 93.1% of parents reflects a healthy, supportive parenting style and alignment with a growth mindset, which values not only outcomes but also the process of effort. The child indicator "Perceives self positively" showed the highest increase—from 0.39 to 0.72 between February and April (see Table 2)—confirming the effectiveness of this form of support. Challenges in Parenting Practices:

Irregular use of books, games, and cartoons for discussing emotions limits the development of children's empathy and imagination.

Low frequency of emotional play hinders the development of self-regulation and empathy in children.

Lack of body-oriented practices prevents children from developing physical self-soothing skills, increasing the risk of psychosomatic responses.

In conclusion, the development of children’s psycho-emotional sphere is closely linked to intentional and conscious parental practices. During times of crisis, emotional modeling, body-based self-regulation, and play-based processing of experiences become particularly important.

Interpretation of Data from Table 2. The data reflect the dynamics of psycho-emotional development in preschool children across key domains: emotional functioning, self-esteem, and stress resilience, assessed over three time points—February (baseline/intermediate), March (intermediate), and April (intermediate), 2025. Evaluation was conducted using a 0 to 1 scale, representing the average level of development for each indicator within the respective domain.

The most significant progress was observed in the indicator "Perceives self positively," which increased from 0.39 to 0.72 (+0.33), indicating active development of a healthy self-esteem.

The least improvement was observed in the indicator "Knows calming strategies," which increased from 0.21 to 0.52 (+0.31). Despite the growth, it had the lowest initial value and remained among the lowest by the final assessment, indicating a need to strengthen body-oriented and self-regulation practices.

Interpretation of Data from Table 3. It presents the aggregated results of monitoring preschool children's development in the areas of emotional functioning, self-esteem, and stress resilience, assessed across three time points: February (baseline/intermediate), March (intermediate), and April (intermediate), 2025. Each indicator was evaluated on a scale from 0 to 1.0, reflecting the average level of development for each domain.

Summary results of monitoring the development of emotional domain, self-esteem, and stress resilience in preschool children (February – baseline/interim, March – interim, and April – interim 2025)

| Domains of psycho-emotional development in preschool children | Baseline monitoring | February interim monitoring | March interim monitoring | April interim monitoring |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Development of the emotional domain | 0,28 | 0,52 | 0,57 | 0,60 |

| Formation of positive self-esteem | 0,30 | 0,52 | 0,56 | 0,62 |

| Stress resilience | 0,25 | 0,49 | 0,55 | 0,59 |

Throughout the monitoring period, positive dynamics were recorded across all three areas of psycho-emotional development.

The emotional domain increased from 0.28 to 0.60, indicating an almost twofold improvement in the level of emotional skill formation.

Self-esteem reached the highest final score—0.62—demonstrating steady development of self-confidence and social adaptability.

Stress resilience rose from 0.25 to 0.59, reflecting a significant improvement in self-regulation and the ability to cope with emotional tension.

Thus, from February to May, a consistent positive increase was observed across all three domains, correlating with the intensity of parenting practices. The most significant progress was noted in the development of positive self-esteem (up to 0.72), particularly among children whose parents consistently offer support, acknowledge emotions, and discuss challenges. The slowest growth was in the area of self-regulation (0.52), which is linked to the low frequency of body-oriented practices used in families.

The materials include empirically grounded tools for supporting children in crisis conditions. The "2 by 2" model is presented as an alternative to traditional early childhood education during wartime, emphasizing active parental involvement. The multilevel monitoring approach enables timely identification of challenges in emotional development and allows for the adaptation of support strategies accordingly.

The survey covers key aspects of emotional interaction, including emotional expression, coping strategies, and the growth mindset, guiding parents toward specific, actionable practices. It also identifies barriers such as emotional burnout, cultural norms, and lack of knowledge—providing a foundation for designing targeted educational programs for families.

The article is valuable for teacher training, as it provides assessment criteria based on the ontogenetic approach and includes examples of integrating body-based, verbal, and play-based practices into everyday interactions.

The results have implications for educational policy development: they confirm the importance of systematic parental support and can be adapted to other crisis contexts, including war, humanitarian emergencies, and displacement. They may also be used to advocate for the integration of emotional intelligence foundations into educational and partial (supplementary) programs.

The study is limited by the impact of war, which complicates the educational process, reduces available resources, and narrows coverage. External moderators—such as parental psychological trauma, social media influence, and community support—were not considered, although they may affect the child's emotional state.

The data are based on parental self-reports, which may be biased by emotional distress or the desire to give socially acceptable answers. The study captures only an intermediate state and does not reflect long-term developmental trends.

Future research should include longitudinal studies to track changes from the onset of crisis through stabilization, with further assessment of their impact on children's psychosocial development.

The third phase of monitoring within the project "Improving Access to Early Childhood Education Services in Emergency Situations" enhanced the methodology, making it more adaptive to crisis conditions and relevant for preparing professionals to face complex challenges in early childhood education.

The data confirm that parental emotional involvement is a key factor in the development of children’s emotional intelligence and overall well-being. Over 70% of parents demonstrate an empathetic style, provide support, and engage in reflection, which contributes to improvements in children's self-esteem, self-regulation, and stress resilience.

At the same time, about one-third of families show inconsistency in addressing fears, failure, and emotional tension regulation—factors that negatively affect children's psychological stability. These families often lack the knowledge or resources necessary for intentional emotional support, which is particularly critical in times of crisis.

In conclusion, parents are the foundation of a child’s emotional safety. Systematic work with families is needed to promote the use of body-based, play-based, and verbal methods of emotional support.

Early childhood education institutions are encouraged to focus on strengthening parental competence through training sessions, visual materials, and collaborative partnerships.

The development and piloting of strategies for supporting and maintaining mental health are crucial for mitigating the effects of high stress, enhancing children's overall well-being, resilience, and socialization processes (Kosenchuk & Tarnavska, 2024).

Systematic analysis and conclusions support the creation of targeted psychological and educational interventions, as well as the development of optimized early childhood development programs. These programs have been successfully piloted and implemented within the framework of the Project (Kosenchuk & Tarnavska, 2024a; Kosenchuk & Tarnavska, 2024b).