1. Introduction

We start this paper by asking a question – how might we develop critical perspectives and alternative forms of technology-supported learning in professional settings? There is currently an urgent need to respond to major global issues such as climate change, forced displacement and global health challenges. At the same time, we live in an era of hype around innovation, the future of work and education, especially in light of recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI). Recent research highlights the need to support professionals to learn to deal with complex scenarios in their everyday practice, which necessitates an understanding of “how the global and local intersect and how this knowledge can be translated into teaching and learning practice” (Carvalho, Castañeda & Yeoman 2023). We, as educators, can help professionals respond to these issues by contributing to the design and development of learning in professional settings.

It is essential that educators are mindful of what forms of design work can support workers in various professional roles to develop the capabilities needed to understand and act upon global challenges within their localities and communities. These forms of design require a good understanding of professional values that guide the design work (Carvalho, Castañeda & Yeoman 2023). This requires a transition away from how (conventionally) we conceptualise professional development programmes that prioritise content, prescribed solutions, or individual gains to instead reframe how we think about learning at the workplace. To guide this rethinking, in this paper we consider emerging trends at three levels of the educational ecosystem: global developments (macro), (workers’) local practices (meso), and daily activities (micro) (Markauskaite et al. 2023).

This paper examines how we, as educators, developed complex designs and attended to design choices related to teaching and learning practice in the context of a professional development programme focusing on Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR). We highlight and share the underlying values guiding our learning design choices. We also describe how we developed pedagogical strategies to encourage collaboration, individual agency, productive participation, and authentic co-creation in learning (Castañeda et al. 2023). Crucially, we aim to offer an account of how we considered technical and practical elements in our design work to develop integrated designs that would work for professional learning at-scale. Through this account, we stress our commitment “to collaboratively transform structures and processes” (Carvalho, Castañeda & Yeoman 2023: 341) in ways that support designs for learning in work settings to become more conversant with systems thinking necessary to tackle major societal challenges.

We frame the analysis within an Activity-Centred Analysis and Design (ACAD) framework (Goodyear, Carvalho & Yeoman 2021; Goodyear & Carvalho 2014) that provides a means to (retrospectively) analyse and map assemblages of people, tasks and tools across those levels and reflect on the creation of designs that are well-aligned to pedagogical values (Goodyear, Carvalho & Yeoman 2021; Goodyear & Carvalho 2014). In doing so, the paper expands on this body of work and contributes an exploration of future professional learning by tracing connections between approaches to learning and design for learning in response to major societal challenges.

2. Professional learning within the context of work

Transforming structures and processes around how professionals learn requires reconsideration of current approaches to professional development. Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) have been viewed by employers as a way to accelerate professional learning by offering learning at scale and reach in an affordable way (Hamori 2018). Over the decade from 2011 to 2021, the number of learners who participated in a MOOC increased from 300,000 to 220 million and many of these were professionals (Diaz-Infante et al. 2022), whose main motivations seem to include gaining specific job skills, preparing for additional education, and obtaining professional certification (Garrido et al. 2016). MOOCs can be designed in ways that engage committed professionals to put their knowledge into action in ways that support their learning (Laurillard & Kennedy 2020). In relation to teacher professional development, MOOCs have been used to build teacher capacities and are perceived as an effective way to expand pedagogical knowledge and classroom practices (Koukis & Jimoyiannis 2019). Similarly, the MOOC technology has been used as a method to supplement and augment medical training and inter-professional learning (Bettiol, Psereckis & MacIntyre 2022).

Several studies draw on MOOCs because they are seen as being more relevant in countries that may have a shortage of means and methods to provide professional development opportunities to a large number of teachers at different levels (e.g. Pherali et al. forthcoming) or across a range of health workers (e.g. Bettiol, Psereckis & MacIntyre 2022). By leveraging the efficiencies in content delivery, MOOCs for example have been used in research training for health professionals in low-and-middle-income countries (LMICs) (Launois et al. 2021) and One Health1 education in Kakuma refugee camp in Kenya (Bolon et al. 2020).

Despite a well-intended approach to providing free-to-access online professional learning and addressing life-long learning and widening participation agendas, such claims have been criticised (Lambert 2020). Scholars have documented several shortfalls in MOOCs such as cultural-epistemic injustices (Adam 2020), focusing on relevance, inclusive processes and the geopolitics of knowledge production. MOOCs are lacking diverse and pluralistic content, while the hegemonic role of English language is noted. Other well-documented issues are raised in the literature, for example low completion rates (Jordan 2015), lack of diversity in enrolment (Greene, Oswald & Pomerantz 2015), certification cost, and the fact that most MOOCs are standalone and do not form part of a broader curriculum, thus do not build towards an accredited comprehensive programme (or degree).

At the level of implementation of MOOCs, challenging dominant discourses can be achieved by including, and creating space for interaction and co-creation of knowledge, as in the case of the TIDE programme in Myanmar, in which the Open University UK worked with local partners to co-produce contextually relevant open educational resources (Farrow et al. 2023), and the MOOCs developed by the RELIEF centre at UCL with partners and community members in Lebanon (Kennedy et al. 2022). In both cases a design process is followed that is tailored to the needs of a specific population group. Designing MOOCs in ways that pay attention to the needs of the professional adds value to the learning experience (Kennedy et al, 2022; Littlejohn, Kennedy & Laurillard 2022). To add value, it is vital that professionals themselves are involved in the design by contributing their knowledge (Laurillard 2024; Kennedy & Laurillard 2023). What is more, in the global space of MOOCs with heterogeneous participants distributed across the world, it can be difficult to have content that is relevant to everyone, thus emphasis needs to be given to pedagogical decisions to include diverse voices and critical thought from the participants themselves (Adam 2020). This is well aligned with the approach reported in this paper.

Furthermore, adapting both work practice and the workplace context is important because of the reflexive relationship between the knowledge learned and the context of knowledge application in the workplace (Billett 2004). Professionals have to apply the knowledge they learn in a course to their work, taking into account the local work context. This involves the extra effort of abstracting the knowledge learned in a course and re-applying it in the workplace (Markauskaite & Goodyear 2017). In the context of MOOCs, this means that the separation of the learning context (eg a MOOC) from the work context can make it difficult for professionals to apply new knowledge and adapt how they work (Littlejohn, Kennedy & Laurillard 2022). The study presented in this paper explores how professional learning online and at a distance can be designed in ways that support professionals in making the connection between the learning context and their work context.

3. Framing design: The Activity-Centred Analysis and Design framework

Many models and frameworks that offer approaches to the design of learning, often with the use of technology, have been featured in the literature (e.g. Laurillard 2002; Conole et al. 2008; Goodyear & Carvalho 2014). Such models tend to follow a learner-centred process (Laurillard 2012) and the term ‘learning design’ has been used as an approach that enables teachers and designers to make informed decisions (Kennedy & Laurillard 2023). The term ‘design for learning’ has also been featured in the literature (Dimitriadis & Goodyear 2013) to highlight that learning itself cannot be designed, and instead what is designed may have an indirect effect on learning, which is emergent and responsive to what was designed. This concept also highlights the critical role that the teachers have as ‘actors’ and ‘designers’ of learning, who often have intentions during the design process and are likely to influence what is happening in a learning situation, irrespective of situations taking place in-person or at a distance. For Dimitriadis and Goodyear (2013), this approach is “partly about designing with a sensitivity to the complexities and unpredictability of what happens after a design ‘goes live’” (2013: 2) but also being mindful that learning situations (and consequently learning) are complex and affected by a multitude of factors.

For our analysis we draw on a framework that supports understanding and improving of complex learning situations and was developed by Goodyear and Carvalho (2014) and their subsequent work (see e.g. Carvalho, Castañeda & Yeoman 2023; Goodyear, Carvalho & Yeoman 2021). The Activity-Centred Analysis and Design (ACAD) framework emphasises that learning is always physically, socially and epistemologically situated (Lave 1991). This perspective takes into account the local environment where each learner is situated, rather than assuming a standardised ‘learning environment’, and, as such, may be better suited to analyse and design professional learning that takes place across diverse workplace settings. For professional learners, the physical situation represents the place of work and the resources available to them but also the space that is used or is created as part of the teaching and learning process (e.g. classroom, web space). The social situation is influenced by their role and includes people and resources they interact with. The epistemological situation depends on the physical and social settings as well as the objectives of the job (i.e. tasks performed).

This framework draws an important distinction between two key moments: ‘design time’ and ‘learn-time’, where structural elements often situate and influence activity, but do not determine it. This is because the framework highlights learners’ agency to change and reconfigure what is proposed in the design, which ACAD describes as “emergent or influenced by design” (Carvalho, Castañeda & Yeoman 2023). In other words, this framework distinguishes between “what has been designed (planned) and what learners actually do (learn) and these reflections provide meaningful and actionable feed forward into future (re)designs” (Carvalho, Castañeda & Yeoman 2023: 344).

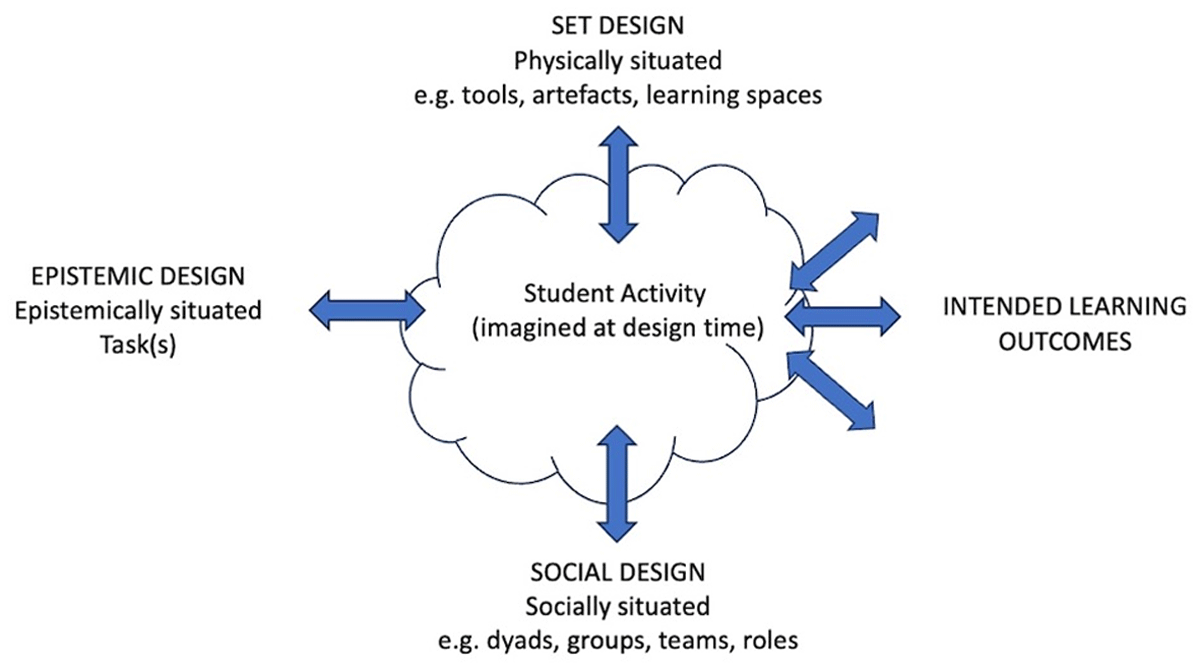

Specifically, ACAD considers four structural elements. The first three are “designable” components (see Figure 1), the last one is “emergent” (Goodyear, Carvalho & Yeoman 2021):

Set design – the digital and physical elements, including materials and digital artefacts, tools and resources.

Social design – social organisation/social arrangements of learners such as dyads and groups.

Epistemic design – proposed tasks, types of knowledge and ways of knowing, including the sequence and pace of tasks and assessment.

Co-creation and co-configuration activity – emergent activity, including ways that students may re-arrange and re-configure what is proposed.

Figure 1

ACAD at design-time (Source: Goodyear, Carvalho & Yeoman 2021: 449).

In this analysis, we examine the first three ‘designable’ elements of the ‘Tackling Antimicrobial Resistance’ MOOC and maintain an interest in how these enabled emergent learning activity (with a focus on online web-based technologies) through the ACAD framework. We are mindful that our knowledge of what has happened in ‘learn-time’ is still emerging and it is thus beyond the scope of this paper to analyse this aspect. This is partly because of the nature of examining changes in work practice. Such changes do not align with the lifecycle of a course, can take time, and are intertwined with other elements in the work-life of the learner (e.g. workplace policies, cultural barriers) and would thus require inclusion of methods that could generate insights beyond what could be ‘observed’ in the course itself. This is also partly because we draw on a case (i.e. AMR curriculum for professional learning) which encourages independent/unsupervised, self-paced learning – autonomous from us as educators/designers and there is a constant stream of learners distributed across the world signing-up to the course.

Despite this limitation, our approach in the sections that follow focuses on identifying how created artefacts (e.g., course materials, resources), places (e.g., a web space, workplaces), divisions of labour (e.g., arrangements planned for learners to work in groups, pairs, etc.), and tasks (e.g., what learners were asked to do) relate to one another, and how a combination of a particular set of elements may influence learners’ activity. To do this we use the ACAD wireframe (Table 1) (Carvalho, Castañeda & Yeoman 2023), a grid which helps in identifying designable elements across dimensions of design (epistemic, set, social) and across levels (micro, meso, macro). Taken together, ACAD and its wireframe, alongside illustrative examples from the AMR curriculum, offer a practical approach to analysing a complex learning situation, in a way that can produce knowledge that will be reusable in subsequent design work. This was deemed important particularly because in the context of major societal challenges, we cannot rely on expertise from any one domain and as educators we increasingly find ourselves involved in design work in diverse and multi-disciplinary teams, often distributed across institutions and sites. Such teams are often assembled to carry out this work and include subject-matter experts, experts in online pedagogy, educators, academics, learning support professionals, learning technologists, and managers. Many may lack the requisite design or educational training. As educators, we felt it important to engage in a process of reflection by using the ACAD framework to identify relationships between different design elements to guide subsequent design work we may embark upon and support one another as we explore potential areas that may require re-design as the MOOC is updated.

Table 1

Elements described through the ACAD framework (adapted by Yeoman 2015).

| PHILOSOPHY | SET DESIGN LEARNING IS PHYSICALLY SITUATED | EPISTEMIC DESIGN LEARNING IS SUPPORTED THROUGH KNOWLEDGE-ORIENTED TASKS/ACTIVITY | SOCIAL DESIGN LEARNING IS SOCIALLY SITUATED |

|---|---|---|---|

| MACRO The global | Complex mix of digital and physical artefacts, texts, and tools (incl. global frameworks on AMR, digital systems) Diverse built/work sites across sectors and geographies Online learning platform. Internet infrastructure/networks in LMICs/remote locations | Scientific research and scientific methodologies (e.g. research on AMR, research on learning in professional settings, research on learning online) | Broader cultural context (e.g. rules, norms, division of labour re. organisation of work in health/vet settings in LMICs) |

| MESO The local | Site on the platform Modules’ site Physical space at work (e.g. facilities for teaching and meetings, computer lab) Physical space at home Local/Organisational digital and physical artefacts, texts and tools (incl. infrastructure for connectivity/broadband accessibility, and national and org policies, AMR Data (org/national level)) | Pathways designed per role Sequence of modules Module content Assessment framework | Distance learning modality Asynchronous learning Independent learning Individuals encouraged to connect with their professional communities Inter-dependency of roles and responsibilities |

| MICRO The detail | Access to work devices (e.g. PCs) Access to personal devices (e.g. laptops, mobile phones) Access to work equipment and spaces (e.g. disks, reagents, lab equipment, lab spaces Data – broadband accessibility Downloadable/printed materials in various formats (ePub, pdf etc) Multimedia resources/videos Time allocated for study | Selection of modules Tasks (incl. assessment) Pace of study | Social arrangements may be continually changing Connections include Tutor – students (indirect); Students – colleagues and wider AMR community |

Drawing on applications of the ACAD framework in a variety of contexts (see e.g. Green et al. 2023; Heredia, Carvalho & Vieira 2019), we explore the application of the framework to online/distance learning in professional settings in low- and middle-income countries. Here we focus not only on connections at a macro level (e.g. global distribution of learners), but also the implications of such work for those designing professional learning at a distance at the meso (e.g., the university, companies) or micro contexts (e.g., sequencing of a lesson, tasks etc).

In the following sections we describe the methods and the context of our case study. We then analyse the case study within the ACAD framework.

4. Case study context: Professional learning for AMR at a distance

The study is contextualised in healthcare, specifically the use of antibiotics and the challenge of AMR. AMR occurs when microorganisms (bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites) no longer respond to antimicrobial medicines resulting in medicines becoming less effective and infections becoming difficult to treat. AMR is a leading global health issue that imposes significant social and economic costs on society (Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators 2022) and is severely affecting resource-limited settings, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa and South-east Asia (Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators 2022). As a major health challenge, practices associated with AMR change rapidly requiring professionals to learn continuously and adapt to new ways of working.

Our on-going work in this field investigates forms of professional learning that support people as they learn and apply knowledge about AMR in clinical or animal health settings in LMICs. In a series of interlinked publications (Charitonos & Littlejohn 2022; Kaatrakoski, Littlejohn & Charitonos 2021; Littlejohn, Charitonos & Kaatrakoski 2019), we examined professionals’ practice by drawing on the theoretical framework of socio-cultural and cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT) that conceptualizes human activity as object oriented, collective and social. We gave attention to the tensions that professionals may face when they accommodate the new AMR surveillance practices within their existing work. The tensions were understood as manifestations of contradictions in the form of problems, challenges and disturbances associated with professionals’ work within an activity system (Engeström 2015; Ilvenkov 1982). The following paragraphs offer a brief description of tensions identified (a more detailed discussion is available in Charitonos & Littlejohn 2022; Kaatrakoski, Littlejohn & Charitonos 2021; Littlejohn, Charitonos & Kaatrakoski 2019).

First, professional groups are not always aware of the global threat posed by AMR and entrenched professional practices are deep-rooted in existing forms of practice. Second, although AMR is considered as a multisectoral challenge, changes in ways of working are not considered across human health, animal health and environment sectors. AMR surveillance relies on distributed networks of professionals working together around shared knowledge objects (i.e. AMR Data). This requires trust and openness among professionals, but this trust is not always evident, particularly where people are working in silos. Another tension is related to the monitoring of AMR data which relies on the flow of the data through local, national and global systems. Yet these networks are under-developed; professionals have limited conception of how these networks inter-relate or how their role is situated in, and contributes to, these networks. For learning to be effective, practitioners need to understand their role and work in relation to these new, extended contexts and networks and familiarise themselves with collective knowledge around AMR surveillance. The role of cultural and organisational norms and rules needs to be considered when arranging learning opportunities and developing work around AMR.

In sum, the analysis of tensions was powerful in revealing the systemic tensions and issues preventing the development of new ways of working, and the complexity inherent in this system where these tensions were manifested across levels (e.g. macro, micro). A key challenge for us was related to unpacking the links between the theoretical breadth offered by CHAT in the studied context and pedagogical practice for learning at a distance and making such knowledge actionable. As others have noted, it is difficult to take such theoretical conceptualisations and consider how to situate them in pedagogical aspects of design (Bower & Vlachopoulos 2018). For us, each of these tensions offered an ‘opening’ to numerous pedagogical possibilities and at the same time raised challenges both in the internal workings of heterogeneous teams and in our engagement with the funding bodies, as these had to constantly be viewed in relation to an aspiration to draw on critical digital pedagogy frameworks and create opportunities for expansive learning (Engeström 2015) online, but also in the light of feasibility and material constraints entailed in the (any) project. In other words, we were dealing with the “pragmatics of messy, real-world analysis and design” (Goodyear, Carvalho & Yeoman 2021: 466).

5. Methods

In this paper we draw on the global AMR curriculum ‘Tackling Antimicrobial Resistance’ as a case. This was purposely selected as the team authoring this paper were leading (authors 1, 3) or worked on (authors 2, 4) the design of the modules. As a team we participated in a variety of project activities, including fieldwork (authors 1, 3), authoring workshops (authors 2, 4), design of resources and materials that are available on the platform (all authors) and project evaluation (authors 1, 3). To this end, we have access to notes (team meetings, author workshops, meetings with the funder), design drafts, log files of students’ activity and other types of empirical evidence generated as part of this project. Information related to the course and modules was collected from the online platform, which offered us access to course/module descriptions and learning outcomes (available to any visitor/user of the platform).

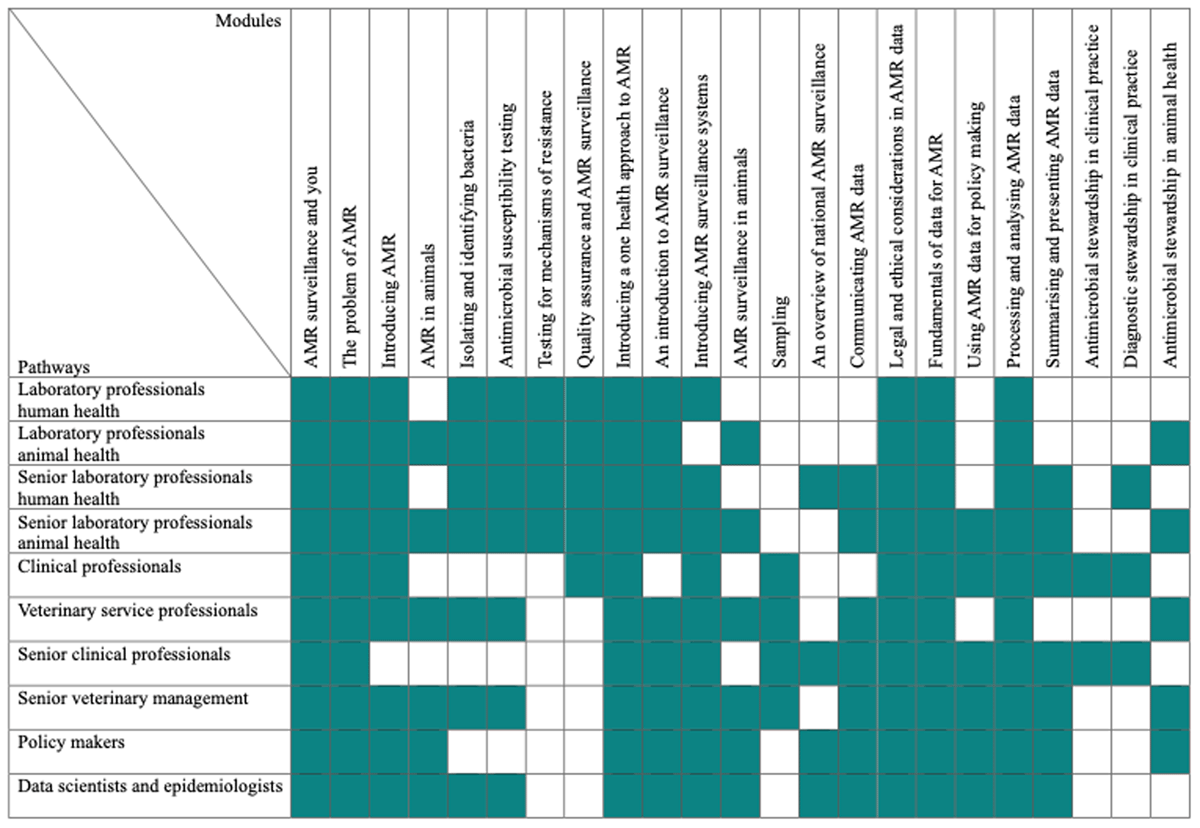

The curriculum was developed on the OpenLearn Create platform. A key decision made in the early stages of the design work, in response to the tensions identified above, was for the online collection to comprise 23 short modules linked as a set of 10 learning pathways targeted towards professionals in specific job roles. Figure 2 below shows a diagrammatic representation of the pathways and modules. In this figure, each short module (columns) focuses on an area of knowledge and skills that were deemed essential to effectively tackle AMR, allowing learners to purposefully select and navigate through the course based on their individual needs, roles and workplaces. Ten discrete learner pathways (rows) consider the needs of key stakeholders in roles associated with AMR work. Pathways are mapped against specific modules; not every profession requires every module, but many modules are required by several professions. The modules were released between January 2021 and August 2021. In the ACAD wireframe that is presented in Table 1, curriculum is situated within the epistemological/meso level (see Table 1).

Figure 2

Modules and learner pathways in the global AMR curriculum.

In the analysis section that follows we draw on specific examples across modules and pathways in a way that allows us to retrospectively engage with how we went about the ‘design time’ (Carvalho, Castañeda & Yeoman 2023), namely the ‘moment’ in which we as educators engaged in advanced planning including the selection and specification of tasks, tools, and social arrangements. The examples selected serve to illustrate pedagogical possibilities and values, and highlight certain decisions made in the light of these. They also serve to stress that design for learning in professional settings should not be treated as isolated instances within primarily the epistemological element (2nd column, Table 1), but importantly as a holistic engagement across elements and levels (in horizontal, vertical and diagonal movements – see Table 1). Table 1 serves as an illustration of elements described through ACAD in relation to the case presented in the paper.

We note that many of the elements presented in the table at the macro level (1st row) are not static but evolve continuously because of the emergent nature of the AMR as a health challenge (e.g. evolving domain/research, evolving global and national systems, protocols, and policies, evolving roles and rules associated with AMR). This also has direct implications for developments at the meso level, especially in terms of local/organisational level policies, protocols, and the availability (or not) of equipment (set design) but also wider professional communities linked to AMR (social design). This further had implications for us, because many aspects were ‘in-the-making’ while we were engaged in design work (e.g. equipment available within work settings as part of the wider grant, availability of AMR data and policies) and were thus unknown to us as educators. Finally, and slightly paradoxically given the above, another requirement placed upon us was to design a curriculum which would be sustained and remain available to learners beyond the project timeline.

In what follows we use these ideas to describe/theorise about our case study, linking aspects of the meso and micro levels of the design of the course to the broader context (macro level) of learning in professional settings at a distance.

6. Analysis of examples

EXAMPLE 1 – Linking macro to micro levels: global knowledge and local work practice

The notion of connecting global knowledge (epistemic design) to localised work practice is an essential element of professional development. Professionals need to be supported in developing a working knowledge of the concepts, terminology, techniques and approaches that are specific to professionals’ roles. Subject-specific knowledge should not be viewed in isolation but should be associated with opportunities for professionals to make connections between emergent knowledge and their existing work practice.

This objective was achieved by designing the curriculum as distinct pathways to cover subject-specific knowledge relevant to diverse professional roles involved in AMR work (Table 1- epistemic design, meso level). Specific modules were available in more than one pathway, as they were deemed relevant for people across roles (epistemic design). Within each module several learning tasks were included to engage learners with subject-specific knowledge (epistemic design, macro level) and support them in making links to practices in their workplace (epistemic and social design, micro level).

For example, the module, Antimicrobial susceptibility testing aims to develop laboratory and senior laboratory professionals’ knowledge of the testing procedures that generate robust, standardised data for AMR surveillance and to then apply the knowledge in their work. To support learners in linking emerging knowledge of testing guidelines to their existing workplace practices and processes we designed a task in two parts. First, learners consider ‘Standard operating procedures in your workplace’ then in ‘Performing antimicrobial susceptibility testing in your workplace’ learners consider challenges they face while performing these tests in their workplace. Collectively the intended outcome was for learners to recognise the importance of implementing procedures and practices designed to ensure the quality of susceptibility testing in their workplace.

In terms of epistemology, the task utilises learners’ emerging knowledge about international testing guidelines to investigate how these guidelines align with the ways in which they currently carry out susceptibility testing at work. The design prompts learners to independently search for, and retrieve, information about testing practices in their workplace (social design, meso level) in the form of documented standard procedures that can then contextualise the learning task by considering the local processes and practices (epistemic and social design, micro level). Learners are encouraged to link these local ways of working with the knowledge they learn about international testing guidelines by investigating how guideline information is documented in their workplace and if/how their workplace practice differs from international testing guidelines.

To take into consideration the physical, work setting/environment where knowledge learned is applied, the task positions consideration of processes and practices and the challenges they face within learners’ workplaces. To do this, learners draw on resources from their workplace in order to contextualise the task to their local context (set design, social design, meso and micro level). In designing this task, a key consideration was that access to resources may vary depending on learners’ local context and role (set design, macro and micro levels). For example, where susceptibility testing capability is being developed in a workplace standard operating procedures may be unavailable or may not be sufficiently aligned to current guidelines. This variation in access to resources was reflected in variation in how the task was presented to the learners to consider the context within which the emergent activity would happen. So, whilst the design of the task strongly encouraged learners to use documents for their workplace to support them in drawing links between practice in their workplace and emergent knowledge, it also offered an alternative option that recognised that, for some learners, this may have not been available. The task, therefore, also included the option to use exemplar/example documents, accessed via weblinks, such that learners could co-configure the activity based on their circumstances.

The social setting within which the learning takes places gives people access to colleagues/peers they can draw on as they learn (Littlejohn, Milligan & Margaryan 2012). Although the review of operating procedures in the first part of the learning task and reflection on the challenges and barriers in the second part are individual tasks within the module, learners are encouraged to connect with relevant colleagues to support their learning (social design, micro level). This is important because identifying challenges and barriers itself is not sufficient to change practice, challenges need to be shared with others in the workplace to provide opportunities for solutions to be explored and developed.

By offering such tasks, the intention was for each learner to be supported to make concrete connections with things happening in their local setting, which was a key intended outcome in this task. As Green et al. (2023) put it, “assemblage of elements within the design for learning coalesces to influence the emergent activities” (2023: 103). The tasks, as presented in the digital platform/module space (set design, meso), were seen as creating the conditions for connections to be created in the physical space (set design, micro; social design/micro). It is within the physical work space (set design) that these connections may be created and/or strengthened, so that a sense of continuity can be developed between what learners experience as part of their interactions in the digital and the physical settings.

EXAMPLE 2 – Connecting meso to micro: recognising roles, responsibilities and the contributions of one’s own work to local work practice

As an emerging global health challenge AMR is associated with the emergence of new, specialist forms of knowledge, which in turn leads to new roles and practices to be created. This results in a diverse set of new actors from a range of fields becoming involved in AMR-related work (e.g. data scientists, epidemiologists) or professionals already involved in this field (e.g. lab professionals) being required to adapt and take on new tasks and responsibilities within their existing roles.

Reflecting on this tension in our design work, we realised that course materials needed to support professionals to accommodate emerging knowledge and respond to changing circumstances within their roles. It also meant that, as educators, we had to consider the diverse needs of key actors in this field working in a variety of roles that were constantly evolving and support them to reflect on and appreciate their roles, responsibilities and the contributions of their work within the wider system (micro, meso and macro-levels). From a practical point of view this meant that our focus needed to be across the three elements in the ACAD framework (set design, epistemic design and social design) and across levels. In other words, the focus should be on the physical setting in which work is conducted (set design, meso and micro levels) but also on the knowledge and skills that professionals need to learn (epistemic design, macro and meso level) to adapt their role. Finally, the focus should also be on their inter-relationships with others (social design, meso and micro levels).

We are elaborating further on this point through an example from the introductory module AMR surveillance and you, which was the first module in each of the pathways (epistemic design, meso level). Our expectation was for all learners to start with this module. The intended outcomes of the module were for learners to understand how AMR relates to their role, know what knowledge and skills they need to develop for their role, plan a strategy to address these gaps and reflect on how their learning in the other modules in their selected pathway could change their work practice. A key consideration for us while designing this module was to foreground to the learners that each of them individually would need to consider the physical and social situation that they find themselves in, as part of their professional roles (set design, social design). For example, the tasks entitled ‘You as the AMR surveillance professional’ and ‘Your role in the surveillance process’ encourage consideration of learners’ roles within their local AMR surveillance process. Specifically, the task prompts learners to reflect on their role and how it fits within an (emergent) local AMR surveillance process. Whilst the task is designed around a typical local AMR surveillance system as per international guidelines, it also takes into consideration the diversity that exists in different settings and national systems (set design, meso levels). It thus considers the possibility that learners may be in relevant roles with a range of job titles and descriptions and/or have different responsibilities or that learners are in roles that are new and evolving (social design, macro level) and as such may not fit well within the recognised (typical) local AMR surveillance process. To achieve this aim, the task entitled ‘You as the AMR surveillance professional’ encouraged learners to connect with relevant colleagues to discuss local processes and roles (social design, micro level). Similarly, in the task entitled ‘Your role in the surveillance process’ learners were encouraged to reflect on the consequences for others in the surveillance process of not being able to carry out their role.

To support learners in assessing and identifying the knowledge and skills they needed to develop for their role, we designed a series of tasks. A key consideration was to support learners to link their role and individual learning needs (epistemic design) to the specific areas of knowledge within distinct learner pathways. In the first two tasks in this module entitled ‘Identifying the skills required for your role’ and ‘Assessing your skills’ learners were asked to identify activities they carry out in their AMR-related role, consider the knowledge and skills required to carry out these activities and reflect on how confident they were with these skills. Following this, in the task entitled ‘Setting your learning goals’ learners were encouraged to draw on those reflections to develop personal learning goals. Finally, we designed the task entitled ‘Planning your study’ to support learners in linking their personal learning needs to the curriculum learning pathways. The sequencing of these tasks across the module foregrounds the importance of individual needs, roles and workplaces in the learning and encourages learners to have agency over their own learning, while it also highlights that these are always situated within wider structures, norms and rules (set design, social design).

Connecting new knowledge and skills to the local context is critical for the application of global knowledge in the local context. To this end, we designed a reflective learning journal/blog, which was introduced in the ‘AMR surveillance and you’ module but made available across all modules in the course, for learners to record thoughts on how what they learned related to their local work. In relation to this objective, learners were encouraged to reflect on the relevance of what they had learned to their work and how it could be applied to their work via a series of additional questions.

By offering such tasks, the intention was to support each learner to take active steps in planning and managing their own learning, without us making prior assumptions about what each of them needed or the knowledge and skills they were bringing with them as learners of this course. The intention was not to create tasks that foreground individualistic views of professional learning. Instead, the aim was for learners to be able to position themselves and their needs in relation to wider professional communities and structures as emerging in their work setting and/or global systems. The tasks, as presented in the digital platform/module space (set design, meso), were seen as creating the conditions for connections to be created between the personal and the practical for learners to be able to influence both their own learning and developments in their own setting and communities. This way “both individuals and their institutional contexts are subject to change as learners gain agency over their learning processes” (Tasquier, Knain & Jornet 2022: 1).

7. Designing for professional learning: Conclusions and limitations

In this paper, we started from the idea that the current major societal challenges are urgently challenging us as educators. In particular we are challenged to re-think and re-consider our role in the design for learning in professional settings. This is, on the one hand, related to supporting professionals to adapt to a changing environment in the light of new and/or emerging fields (such as AMR) and, on the other hand, about considering professionals’ roles within wider, complex systems and professional settings. To support professionals to learn and successfully act upon and navigate novel situations that are both urgent and complex, calls for alternative ways of thinking about design that considers what it means to equip professionals with the knowledge, experience, and supportive structures they need to face the complexity of their professional lives and contribute – both as individuals and within their communities – to the changes/transformation required by current societal challenges.

This paper emphasises the changing nature of work and recognises that we are increasingly involved in designing learning for professional work that is ‘in-the-making’: work that is evolving, with roles, responsibilities and dependencies that are not yet fully established. For this reason, we urgently need to move away from concepts of professional learning that focus on micro-levels of activity in this ecosystem. These concepts are preoccupied with delivering courses and curriculum that provide knowledge. As we argue in the paper, design for professional learning – including professional learning in MOOCs – should be treated as a holistic engagement across physical, social and epistemological elements. Critically, professionals need to be encouraged to make connections with developments at the macro level and with their local work environment, work practices and communities (meso and micro levels).

The focus of this paper has been on the ‘design-time’, as per the ACAD framework. We recognise that ‘learn-time’ is critical but the paper’s primary aim was to analyse and reflect on the creation of designs, offering our perspective as both authors of this paper and leads of key work-streams of the project. We also acknowledge that in offering the reflective analysis in this paper, we did not consider the views of colleagues who were involved in wider authoring teams, as they also had active involvement in the development of the online modules. We have sought their views through individual, one-to-one interviews, and we aim to analyse the data generated to offer further insights on elements they considered and challenges they faced in their designs.

The ACAD framework offers a practical reflective tool to rethink how learning activities can be designed and (re)shaped to encourage learners to make those connections, and to also consider future (re)designs we may embark on. Through this process, we recognise that our designs should anticipate and plan for situations in which learners could encounter and interact with tools, tasks, and others as they create or co-produce knowledge artefacts. The emphasis should also be on making connections across the macro-meso and meso-micro levels by encouraging connections and interactions across digital, physical and social arrangements. Through this process we also became aware of the need to support learners to recognise their agency as a form of practical action that may help them to navigate their professional lives and influence changes. Indeed, a key notion we need to consider in future work – and arguably a persistent challenge for us – is “the agentic role of individuals in terms of their possibility to influence the collective dimension and the evolution of the system” (Tasquier, Knain & Jornet 2022: 18). What will be critical in future design for professional learning – and an area of further deliberation within the ACAD framework – is understanding how to support the development of a sense of agency in ways that allow professionals to move from micro-levels of activity to committed actions that may influence transformational changes in professional lives/settings (meso and macro levels), in response to the complex and important issues of our times.

Notes

[1] “One Health is an integrative and systemic approach to health, based on the understanding that human, animal and ecosystem health are inextricably linked.” (Mettenleiter et al. 2023: 1).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Mott Macdonald and the UK Government Department of Health and Social Care for funding this study and for the support they provided during the production of the global AMR curriculum. We are also grateful to Tim Seal, Paola de Munari and Olivier Biard for their work on project management and to all authors and critical readers for their contributions to course materials.

Funding Information

This work was funded by UK Aid, Department of Health and Social Care, Fleming Fund 2019–2023.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Author Contributions

All authors prepared the manuscript and approved the final version before submission.