Introduction

Higher education institutions use digital social networks (i.e., X, Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Snapchat, LinkedIn, and others) primarily to broadcast resources and materials to entice prospective and current students. Within these institutions, departments and programs are using digital social networks to create affinity spaces for stakeholders (i.e., current students, faculty, staff, alumni, and other members of the community) to share information such as publications, events, accomplishments, links with resources, and others (Romero-Hall, Kimmons & Veletsianos 2018). Furthermore, it is no surprise that digital social networks have permeated higher education settings for teaching and learning purposes (Romero-Hall & Li 2020), given their influence on young adults (Zachos, Paraskevopoulou-Kollia & Anagnostopoulos 2018) and the affordances they provide for a variety of educational experiences (Romero-Hall et al. 2023). Researchers have established that the use of digital social networks in the physical and online classroom can influence learning experiences by supporting communication and collaboration (Smith & Buchanan 2019; Zachos, Paraskevopoulou-Kollia & Anagnostopoulos 2018). Still, many academics continue grappling with how to properly leverage the use of digital social networks for teaching and learning.

When it comes to the use of digital social networks by scholars in institutions of higher education, research related to networked scholarship by Veletsianos and Kimmons (2016) stated that academics tend to have varied or low participation in digital social networks such as Twitter (now referred to as X). Additionally, past research stated that academics are more hesitant than their students to actively partake in digital social networking for professional purposes (Zachos, Paraskevopoulou-Kollia & Anagnostopoulos 2018). Yet, more recent research has established that academics are actively using digital social networks to access peer-reviewed papers, introduce themselves and their academic pursuits, and follow key trends and studies (Bardakcı, Arslan & Unver 2018). With this in mind, in this investigation, we aimed to survey academics who purposely use and participate in digital social networks for professional purposes. This research enables us to better understand how, why, and with what imagined audience in mind scholars use these digital social networks for scholarly communication, socializing, and academic support.

Literature Review

As previously mentioned in this paper, the use of digital social networks in education, at various educational levels, continues to flourish due to its potential for networked learning (Watson 2020; Mese & Aydin 2019; Asino, Gurjar & Boer 2021; Mazana 2018; Castellanos-Reyes et al. 2022; Shelton et al. 2022; Muljana, Staudt Willet & Luo 2022). In addition to being used in a teaching and learning context, different digital social networks have evolved into affinity spaces in which academics aim to socialize and interact with other scholars for professional purposes. These interactions tend to center around academics’ roles related to research, service, teaching, and professional development. For example, research suggests that academics use event-based hashtags to connect during professional conferences as part of backchannel exchanges; however, their participation tends to decrease after these events end (Veletsianos & Kimmons 2016). In addition, some academics use these digital social networks to post information about college life, including upcoming events as well as to share information about new programs (Masele & Rwehikiza 2021). Some scholars regularly write blog posts that are then shared on digital social networks to further spread their message. It is also not uncommon to see research groups, research labs, and academic coalitions create profiles on different digital social network platforms in an effort to connect with other professionals and share their achievements and news (i.e., publications, events, awards, funding, and open positions).

Various research studies have explored the use of digital social networks for professional development by academics, including faculty and graduate students (Romero-Hall 2017; Veletsianos 2016). Researchers have explored engagement in networked scholarship (Jordan 2023; Quan-Haase, Suarez & Brown 2015; Veletsianos & Kimmons 2012; Veletsianos 2016) and the academic use of hashtags on X as part of an online social community (Gomez-Vasquez & Romero-Hall 2020; Espinola Coombs & Rhinesmith 2019), among others. However, there is currently a gap in the literature. Current research has not yet grasped the motivators, gratification, and challenges that academics encounter when considering experiences across the different digital social networks. As stated by Jordan (2020), “the social media ecosystem is wide-ranging, however, and focusing upon particular platforms only examines a single facet of academic identity online” (Jordan 2020: 166). Although there have been efforts to better understand the experiences of scholars using digital social networks, these investigations have been platform-specific (i.e., X, Reddit, Instagram, TikTok, etc.) or focused on specific education hashtags’ communities of practice (Espinola Coombs & Rhinesmith 2019; Jordan 2019; Stewart 2015; Veletsianos & Kimmons 2016).

Furthermore, there is a laundry list of concerns related to using these digital social networks for socializing and as professional affinity spaces (Veletsianos and Stewart 2016). Ethical concerns and challenges include the lack of privacy and being subjected to surveillance by employers, colleagues, or individuals who are part of the community. With this lack of privacy comes opportunities for online harassment, bullying, stalking, and retaliation (Gosse et al. 2020; Kamali 2015; Sutherland et al. 2020). It is also important to acknowledge that these digital social networks that scholars use for public, social, and private exchanges are owned by private entities. These private entities own the content generated by users including text messages, photos shared, and private exchanges. As has happened in the past, the content that users generate and share in these platforms constitutes data that can be sold to third parties as revenue.

Scholars’ engagement with digital social networks is complex, warranting a comprehensive understanding of their use and participation. Furthermore, it is imperative to gain a holistic perspective across different digital social networks. This big picture perspective is pivotal because of the significant impact that different digital social networks could have on scholars’ networked learning, dissemination of scholarship, and communities of practice (Semingson et al. 2017). We cannot assume that, because of the far-reaching use of digital social networks in society for personal purposes, all academics know the similarities, differences, and affordances of these digital networked spaces. The reality is that 70% of faculty use digital social networks monthly for personal purposes but only 55% use it for professional purposes (Seaman & Tinti-Kane 2013).

Theoretical Framework

There are two theoretical frameworks guiding this research: (a) the Uses and Gratification framework (Katz, Blumler & Gurevitch 1973; Gruzd et al. 2018) and (b) networked participatory scholarship conceptualization (Veletsianos & Kimmons 2012). According to the Uses and Gratification framework, purposive media users are motivated by access to media content, exposure to the media itself, and the social ecosystem that facilitates situations of spotlight (Katz, Blumler & Gurevitch 1973). This framework also recognizes purposive media users as effective evaluators looking for, using, and employing media for their own goals (Katz, Blumler & Gurevitch 1973; Gruzd et al. 2018). Networked participatory scholarship is conceptualized as “the emergent practice of scholars’ use of participatory technologies and online social networks to share, reflect upon, critique, improve, validate, and further their scholarship” (Veletsianos & Kimmons 2012: 768). In this investigation, higher education scholars are hypothetically identified as purposive media users who seek gratification through networked participatory scholarship.

Purpose Statement and Research Questions

The purpose of our investigation was to survey academics who purposely use and participate in digital social networks for professional purposes. The investigation also examined scholars partaking in “digital social communities” within these networks for professional endeavors. Digital social communities refers to hashtag-specific chats, public or private groups, public or private online forums, or other forms of affinity groups. The research questions that guided our investigation are the following:

RQ1: How do scholars in different fields use digital social networks for their academic careers?

RQ2: What are the benefits and challenges for scholars using digital social networks for their academic careers?

RQ3: Who are the imagined audiences of scholars when they use digital social networks for their academic careers?

RQ4: How do scholars use and participate in digital social communities?

Methods

Recruitment

This investigation received institutional review board approval (IRB 19–120) at The University of Tampa. A total of 336 higher education scholars consented to participate in the study. However, this investigation focuses on the analysis of 307 largely completed surveys. First, recruitment of participants was conducted via X. The lead researchers widely distributed an electronic survey, posting an invitation to participate and a link to the survey in their X profiles. Tweets sharing the link to the survey also included the #AcademicTwitter hashtag. Second, the link to the survey was distributed widely through the lists of different professional academic organizations, including the Association for Educational Communications and Technology. Third, the survey was distributed and posted in public groups on other digital social networks frequently used by scholars, such as LinkedIn and Facebook. Recruitment and distribution of the link was done over a two-month period. After the two-month recruitment period the link to the survey was disabled in Qualtrics and those who clicked on the survey link received a message stating that the recruitment period had concluded.

Electronic survey

Data was collected via an electronic questionnaire with closed and open-ended questions using Qualtrics. The first page of the survey specified the principal investigators’ names and contact information, the purpose of the research project, confidentiality information, and details related to what participation would entail. All participants were asked to provide consent before proceeding with the survey and participating in the investigation. If participants selected not to provide consent, they were a) redirected to the end of the survey and b) thanked for their willingness to partake in the investigation, and c) none of their data was included in the analysis. Participants who consented to be part of the investigation were then asked to indicate whether they use digital social networks as part of their academic careers. If participants selected ‘Yes’, they were given the option to continue with the survey and their data was included in the analysis. The questionnaire also included inquiries related to participants’ a) demographic characteristics, b) motivators to participate in online professional communities on digital social networks, and c) the benefits and challenges of participation in these types of communities. At the end of the electronic survey, participants were given the option to provide their contact information (email or phone) to participate in a raffle. The research team raffled two gift cards among those who provided their contact information.

Data analysis

Quantitative data analysis of the responses to the electronic survey was conducted. The quantitative analysis included descriptive statistics. The data analysis also included qualitative analysis of textual responses given to various survey items. The researchers employed an inductive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke 2006) to examine all the participants’ responses. Throughout the qualitative data analysis, the researchers focused on identifying patterns and clusters across the responses provided (Creswell 2009; Tesch 1990). For the inductive thematic analysis, two researchers from the research team conducted open coding. The two researchers then met to compare, discuss, merge, and refine the initial codes. The researchers then agreed as a team on a specific set of codes. Next, the same two researchers coded another group of textual responses separately. A second meeting occurred, in which codes were eliminated or added based on discussion. Finally, one of the researchers coded the remaining textual responses.

Results

Demographics

Participants were asked using closed-ended survey items to specify their age group, gender, and geographical region of residence. All participants in this investigation were 18 years or older. A range of different age groups is represented in the data (see Table 1). Most participants were 24–35 years old (32%), 36–25 years old (35%), or 46–55 years old (16%). Demographic data about the participants show that the majority were women (68%), but the data set also includes those who self-identified as men (29%) or as non-binary/third-gender individuals (3%). In terms of geographical regions, analysis of the data revealed that 80% of participants were in North America, while 5% resided in Europe and another 5% in the Caribbean. Table 2 includes a complete breakdown of participants by geographical region. Every attempt was made to reach out to participants globally. Yet, most participants were located in North America.

Table 1

Participants’ Age Ranges.

| AGE RANGES | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| 18–23 | 22 | 7% |

| 24–35 | 96 | 32% |

| 36–45 | 105 | 35% |

| 46–55 | 48 | 16% |

| 56–65 | 24 | 8% |

| 66+ | 5 | 2% |

| Prefer not to disclose | 3 | 1% |

Table 2

Participants’ Location of Residence.

| LOCATION | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| North America | 241 | 80% |

| Europe | 16 | 5% |

| Caribbean | 15 | 5% |

| Asia | 9 | 3% |

| South America | 9 | 3% |

| Africa | 6 | 2% |

| Oceania | 4 | 1% |

| Middle East | 2 | 1% |

Using closed-ended survey items, scholars shared their type of institution and current role. Results indicate that most participants were affiliated with a doctoral-granting university (62%); however, a large number of participants (30%) from masters-granting universities were represented as well (see Table 3). Participants’ roles included graduate students (35%), non-tenure-track instructors (25%), tenured or tenure-track professors (30%), researchers (4%), and others (7%). Using an open-ended survey item, participants also shared their fields of study. The results of the data analysis indicate that the investigation included participants from a variety of fields including arts and humanities (32%), business (10%), education (22%), health (7%), social science (21%), and STEM (8%).

How do scholars in different fields use digital social networks for their academic careers?

Using a closed-ended survey item, participants were asked “What do you use digital social network for in your academic career?”. The results of this investigation show that academics use digital social networks for teaching (n = 101), research (n = 145), service (n = 56), personal branding (n = 123), academic support (n = 85), to interact with other academics (n = 186), and other(s) (n = 10). “Other” ways that academics reported using digital social networks were a) to interact with members of their cohort, b) as editor(s) of an academic journal, c) for branding of a research lab, and d) to promote a program or department. Using a closed-ended survey item, participants were asked “What are your motivations for using digital social networks for your academic career?”. Analysis of the data determined that scholars’ main motivators for using digital social networks were to network (n = 174), look for resources for teaching or research (n = 149), stay informed or discover information (n = 149), and share research or job-related achievements (n = 102). Table 4 includes a complete list of motivators for using digital social networks for professional purposes, as selected by the participants from the options provided.

Table 4

Motivators for Using Digital Social Networks as an Academic.

| WHAT ARE YOUR MOTIVATORS FOR USING DIGITAL SOCIAL NETWORKS FOR YOUR ACADEMIC CAREER? | n |

|---|---|

| To connect with or meet other professors/academics (networking) | 174 |

| To look for resources for my teaching or research | 149 |

| To be informed/discover information | 149 |

| To ask questions or seek help/advice | 115 |

| To share my research and/or achievements in my academic job | 102 |

| To help others | 94 |

| To share resources (content assignments, syllabus, student work, etc.) | 91 |

| To share my opinions about a topic | 87 |

| To build communities of practice | 86 |

| To thank people or show encouragement | 83 |

| To get away from pressures and stress of the academic job | 59 |

| Other(s) | 5 |

Using a closed-ended survey item, participants were asked “What digital social network platforms do you use for your academic career?” The results of this investigation illustrate the range of digital social networks that academics use for career support and to socialize with others. The main digital social network applications included LinkedIn (n = 144), Facebook (n = 138), X (n = 127), YouTube (n = 100), and Instagram (n = 90). Table 5 provides a complete list of digital social network applications used by participants. A closed-ended item was used to survey participants on advice for those scholars who want to improve their online professional and academic presence in digital social networks. Scholars who are active digital social network users for professional purposes encouraged their colleagues to curate content frequently (n = 74), share resources with their network (n = 44), answer questions asked in social communities or chats (n = 20), share their research (n = 33), and share their achievements (n = 7).

Table 5

Digital Social Network Applications Used by Scholars in their Academic Careers.

| WHAT DIGITAL SOCIAL NETWORK PLATFORMS DO YOU USE FOR YOUR ACADEMIC CAREER? | n |

|---|---|

| 144 | |

| 138 | |

| X | 127 |

| YouTube | 100 |

| 90 | |

| ResearchGate | 73 |

| Academia.edu | 62 |

| Blogs | 51 |

| Podcasts | 49 |

| 44 | |

| TikTok | 19 |

| Wikis | 16 |

| Other(s) | 15 |

| Forums | 14 |

| 13 | |

| 12 | |

| Telegram | 11 |

| Publons | 8 |

| Snapchat | 7 |

| Social bookmarking | 5 |

| 1 |

What are the benefits and challenges for scholars using digital social networks for their academic careers?

Using an open-ended question, participants were asked: “What are the benefits of using digital social networks for your academic career?” The benefits experienced by scholars are very much connected to the motivation factors participants shared in this investigation. These benefits include networking in general (n = 70), networking with others outside their institution (n = 25), networking with known peers (n = 17), support (n = 11), information and learning (n = 29), resources (n = 25), sharing accomplishments (n = 8), personal branding (n = 35), seeking job opportunities (n = 6), and other benefits (n = 12). Table 6 provides some sample comments related to the benefits experienced by participants.

Table 6

What are the Benefits of Using Digital Social Networks for One’s Academic Career?

| BENEFITS | n | SAMPLE COMMENTS BY PARTICIPANTS |

|---|---|---|

| Networking in general | 70 | ‘Networking and communicating projects or obstacles to peers for targeted feedback.’ |

| Personal branding | 35 | ‘Visibility, transparency, feedback and recognition.’ |

| Information and learning | 29 | ‘Following experts and receiving information directly from them rather than information interpreted by media.’ |

| Networking with others outside their institution | 25 | ‘Connecting with global scholars, access [to] and information about resources.’ |

| Resources | 25 | ‘Able to communicate with people across the world who otherwise it would be very difficult to connect with. With Twitter it’s easy to hear about things that people are doing, find opportunities, etc. that otherwise I would never know about.’ |

| Networking with known peers | 17 | ‘To follow colleagues whose work is relevant to me.’ |

| Other(s) | 12 | ‘Ease of access.’ ‘Staying relevant and maintaining credibility for tenure/promotion.’ |

| Support | 11 | ‘Contents can be scrutinized by various scholars who come across the content. Seeing and reading about what others have done may help encourage one to challenge themselves to keep on thriving and doing better.’ |

| Sharing accomplishments | 8 | ‘Promote awareness of my work.’ |

| Seeking job opportunities | 6 | ‘I can see job posts.’ |

Using an open-ended question, participants were asked: “What are the challenges or drawbacks of using digital social networks for your academic career?” Some of the challenges that are often present when scholars actively use digital social networks for professional purposes included privacy issues (n = 26), dealing with misinformation (n = 10), access to too much information (n = 11), impostor syndrome (n = 6), the time needed to actively participate (n = 32), harassment issues (n = 26), a false sense of community (n = 8), knowing how to properly draw the line between personal and professional sharing (n = 31), and other challenges (n = 34). Table 7 provides some sample comments related to the challenges experienced by participants.

Table 7

What are the Challenges of Using Digital Social Networks for One’s Academic Career?

| CHALLENGES | n | SAMPLE COMMENTS BY PARTICIPANTS |

|---|---|---|

| Other(s) | 34 | ‘Accessibility issues as Internet penetration has not been sufficient enough.’ ‘Self-promotion gets exhausting.’ ‘It’s always changing.’ ‘Many of my colleagues don’t use it and thus won’t see my posts.’ |

| The time needed to actively participate | 32 | ‘Time consuming. In order to leverage networking and connections, we have to dedicate time to invest in our personal brands online.’ |

| Knowing how to properly draw the line between personal and professional sharing | 31 | ‘There is a pressure to be professional and a difficulty to separate personal posts from professional posts.’ |

| Privacy issues | 26 | ‘Privacy is the biggest thing for me. I enjoy keeping my work life and private life separate.’ |

| Experiences with harassment | 26 | ‘Twitter is where academics are forced to be, but it is toxic as hell! Negative, angry, bullying- it’s bad for society and for mental health.’ |

| Access to too much information | 11 | ‘Difficulty of managing multiple streams of communication when I’m already overloaded.’ |

| Dealing with misinformation | 10 | ‘Vetting sources for misinformation is paramount and can be difficult. Failing to vet can get you into trouble.’ |

| False sense of community | 8 | ‘I wish there was more authenticity in networking. I feel that places like LinkedIn are only about showing off your best attributes so it’s become this competition of who can be better in their industry.’ |

| Impostor syndrome | 6 | ‘It creates false expectations of success and/or failure.’ |

Who are the imagined audiences of scholars using digital social networks for their academic careers?

As part of this investigation, using a closed and open survey item, scholars were asked to share their imagined audiences. Specifically, participants were asked: “Who are your imaginary audiences when you are using digital social networks for professional or academic purposes? Check all that apply and explain the reason for your selection.” The “imaginary audiences” refers to the community of individuals for whom a scholar may curate their online identity while considering choice of language, cultural references, and style of content presentation (Marwick & boyd 2010). Participants shared that their imagined audience included other academics (n = 137), journalists or reporters (n = 36), their students (n = 85), administrators (n = 19), higher education staff (n = 33), family and friends (n = 59), fans (n = 18), and others (n = 11). Some of the ‘other’ imagined audiences shared by participants referred to potential employers outside academia, industry professionals, government leaders, policymakers, K-12 teachers, heads of community organizations, staff in non-profit organizations, and the general public. Table 8 provides some of the sample responses given by participants.

Table 8

Imagined Audiences of Scholars.

| IMAGINED AUDIENCES | n | SAMPLE COMMENTS BY PARTICIPANTS |

|---|---|---|

| Other academics | 137 | ‘This is my primary audience; I want to share my research with other academics or have conversations with them to improve my own research.’ ‘My goal is to connect and research with academics that work [on] the same subject as me.’ |

| Students | 85 | ‘They are for me, the most important audience in all my social media platforms. My engagement is based on them.’ ‘I hope students find resources I post to be helpful.’ |

| Family and friends | 59 | ‘I have some friends or closer colleagues that I wish to share resources and achievements with.’ ‘People who love you although they don’t understand all that you do, but they are happy for your achievements’. |

| Journalists and reporters | 36 | ‘I don’t have many associations with the media, but I do hope to get attention for my research.’ ‘Translating research to lay audience.’ |

| Higher education staff | 33 | ‘We can also engage with the staff. You never know who is interested in the type of content you share and can engage with you and your peers.’ |

| Administrators | 19 | ‘I may find some research that my administrators find interesting, and they may share it.’ |

| Fans | 18 | ‘You may have followers that are not enrolled in your institution but can find your content engaging.’ |

| Others | 11 | ‘Practitioners, as a teacher educator my main audience is K-12 teachers and informal educators.’ ‘Industry professionals, hiring managers.’ |

How do scholars use and participate in digital social communities?

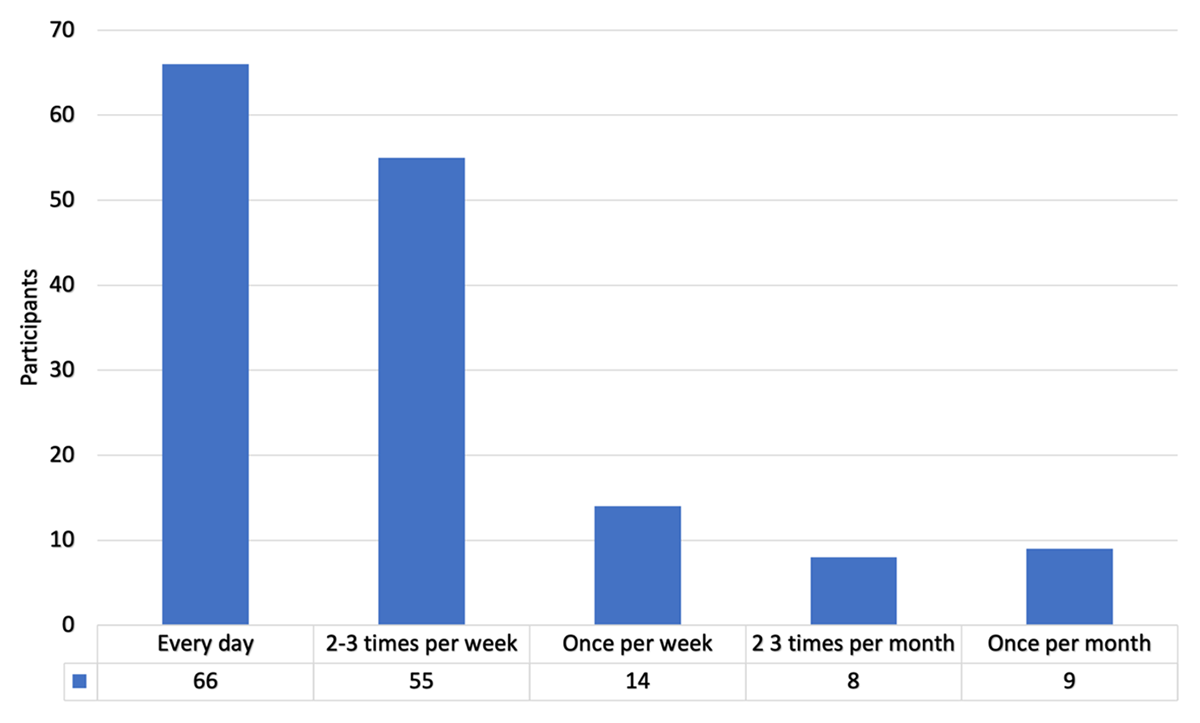

Scholars who consented to being part of this investigation were also asked to share whether they actively participated in online digital social communities. As previously mentioned, digital social communities refers to public or private affinity groups (i.e., hashtag-specific chats, online forums, or other) within digital social networks. Out of 187 people who responded to this survey item, 157 shared that they participate in some form of digital social community. Using a closed-ended survey item, participants were asked how often they engage with their digital social communities, the majority responded that they are active every day (n = 66) or two to three times per week (n = 55). A complete breakdown of responses is included in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Frequency of Participation in Digital Social Communities.

Using a closed-ended survey item, participants were asked why they turn to digital social communities as part of their careers. The survey item options selected most often as their main reasons were a) staying informed or seeking information (n = 134), such as teaching practice or research updates; b) networking with other academics (n = 119); c) amplifying content and ideas (n = 71); d) asking for help and support (n = 70); and e) sharing academic pressures and struggles (n = 69). Participants were given the option to share “Other” reasons. Some of the other reasons mentioned included: “To promote work with like-minded people globally,” “stay up to date with a broad range of teachers in K-12 and higher ed,” and “I’m a lurker, commentor – not a poster.” Figure 2 includes a complete breakdown of participants’ reasons for actively engaging with other academics in online social communities.

Figure 2

Why do Scholars Turn to Digital Social Communities?

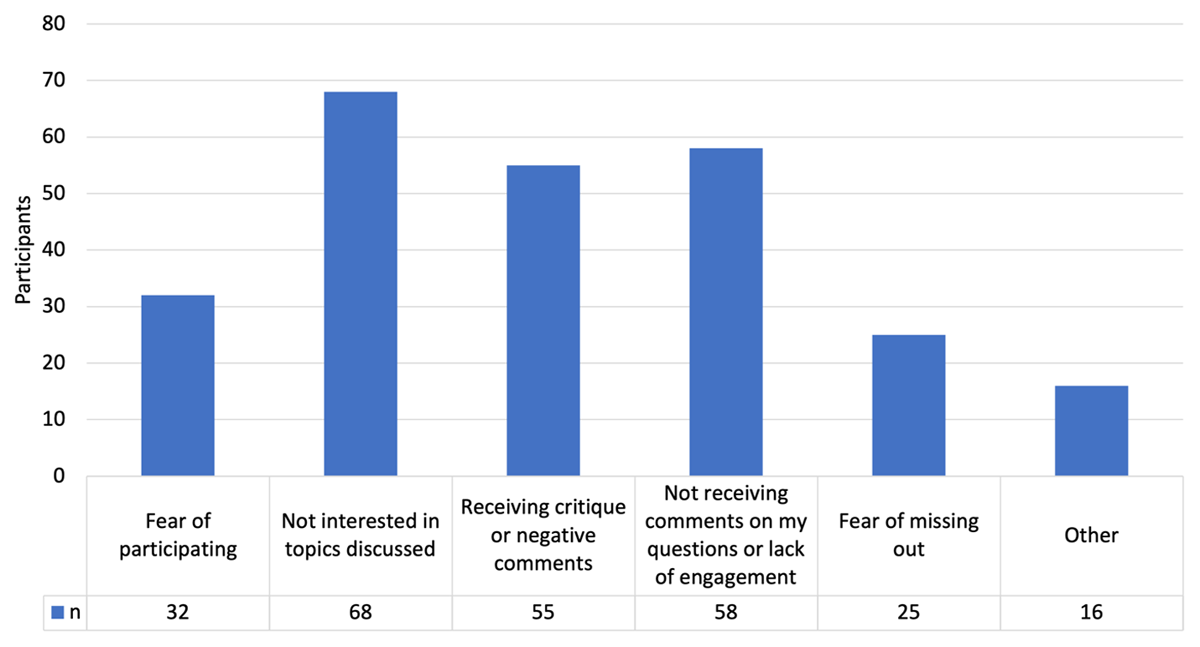

Similarly, participants used a closed-ended survey item to select several challenges that come with actively engaging in these digital social communities (see Figure 3), such as a lack of interest in the topics discussed by other members of the community, receiving critique or negative comments, lack of engagement from other community members when asking questions or seeking feedback, fear of participation, and/or fear of missing out. When asked to list other challenges not mentioned in the survey, participants included ‘privacy concerns’, ‘time overlaps with personal time and time management, specifically having to wade through a lot of marginal material to find something truly useful and valuable’, ‘engaging in topics that deviate too far from current research or commitments’, ‘my perspective may not be tolerated/faculty disparaging students or one another/arguments, hostility’, ‘other people don’t post very much in LinkedIn groups’, and ‘retaliation from institution and other entities related to the university’.

Figure 3

Challenges of Participating in Digital Social Communities.

Using a closed-ended survey item, participants were asked whether they considered their engagement in digital social communities to be continuous professional development. Specifically, participants were asked: “Do digital social communities contribute to continuous professional development? Please explain your response.” The data analysis indicated that the majority of participants felt positive about their use of digital social communities for professional development purposes (see Table 9). When asked to share why they did or did not consider their engagement in digital social communities to be continuous professional development, participants provided a range of different explanations (see Table 9).

Table 9

Digital Social Communities as Continuous Professional Development?

| DO YOU CONSIDER YOUR PARTICIPATION IN DIGITAL SOCIAL COMMUNITIES TO BE CONTINUOUS PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT? | n | SAMPLE COMMENTS BY PARTICIPANTS |

|---|---|---|

| Strongly Agree | 39 | ‘Yes: I’m in many photography groups for professors or artists and I both learn new resources and can share my own. This brings visibility to my artwork, and I have been offered professional opportunities from people seeing my work online.’ |

| Agree | 66 | ‘Social media allows professionals and academics to connect across vast distances and engage with an entire community of peers to share ideas, find employment, collaborate on projects/research, and alleviate the stress of work/school life.’ |

| Neutral | 28 | ‘They can give you new ideas, but it requires a lot of work to wade through arguments and random negative comments and so on.’ ‘Sometimes Twitter is the only place you will see a job or conference advertised.’ |

| Disagree | 5 | ‘They usually start strongly engaged but people don’t stay involved.’ |

| Strongly disagree | 1 | ‘I don’t use this for professional development purposes.’ |

Discussion

The purpose of this investigation was to better understand how scholars use and participate in digital social networks for their professional endeavors. In particular, we were interested in a) the profile and demographics of scholars, b) a general sense of scholars’ motivators, c) the benefits and challenges that are part of these networked experiences, d) the imagined audiences to whom these academics cater, and e) their involvement in and engagement with digital social communities. This research helps highlight how the “values and ideologies of digital and open science aimed at promoting scholarly networking and public sharing of scientific knowledge among a wider public” (Manca & Ranieri 2017: 123) are put into practice by scholars in higher education. The intent is not merely to focus on the tool (i.e., digital social networks) but to consider how these practices serve as steppingstones to increase the promotion of open science, knowledge democracy, and networked participatory scholarship.

The results of this investigation illustrate how scholars, as purposive media users (Katz, Blumler & Gurevitch 1973; Gruzd et al. 2018), regularly use these affinity spaces in ways that influence their professional roles. This level of increased connectivity of academics can be attributed to the many benefits that scholars anticipate and experience, as mentioned in this investigation. But scholars also noted that there are numerous challenges (i.e., dealing with misinformation, access to too much information, a false sense of community, and accessibility issues) that come with engaging in professional socializing in these digital social networks. The results of this investigation suggest that scholars are constantly navigating these challenges and trading them off against the benefits.

Although this specific study did not consider changes over time, research has established that this tradeoff causes scholars to engage differently in digital social networks over time (Veletsianos, Johnson & Belikov 2019). Scholars who are more active on digital social networks today may be less active in the future, and vice versa. It has been documented in the research literature that academics are not always willing to engage in tradeoffs between the challenges and benefits of using digital social networks. Instead, scholars reduce their involvement in these digital social networks to focus on personal life events, professional transitions, self-protection, and relationships offline (Veletsianos, Johnson & Belikov 2019; Jordan 2020). In some instances, scholars reduce their involvement in digital social networks to remove themselves from conversation related to the political climate.

To some measure, a surprising finding from this study are the calculated ways in which academics raise their online profiles and presence. Scholars were quick to recognize how to tactically use these networks to reach a wider audience and were able to easily identify recommendations for other scholars wishing to raise their online presence. The academics, who participated in this investigation, highlighted some of these tactics such as sharing resources, addressing questions, and acknowledging their triumphs. These practices are similar to those of new digital artisans in education, a term used by Marcelo et al. (2022) when referring to teachers in Spain who use digital social networks to build community and share content working with their own means and resources. Due to their similarity in practice, we could consider scholars in higher education using digital social networks strategically as digital artisans because unlike the “education influencer,” whose primarily goal is monetization (Carpenter, Shelton & Schroeder 2022), the reward for participation is focused on social recognition and personal learning (Marcelo et al. 2022).

In terms of imagined audiences, the results corroborate findings from previous investigations in which it was established that scholars have a range of different imagined audiences (Jordan 2020; Veletsianos & Shaw 2018). However, it is clear from the results that the primary imagined audiences for scholars in higher education are other scholars and their students. A noteworthy finding were the many reasons provided by scholars when describing why they cater to specific imagined audiences. The reasons shared by scholars aligned with the self-presentation and impression management theory, which states that “when an individual performs impression management, they carefully consider what personal information should be made available or restricted to other people rather than present a false or untrue image of oneself to them” (Stsiampkouskaya et al. 2021: 2). For the scholars in this investigation, the intent is not to misrepresent or manipulate their content; instead, the intent is to share content that the imagined audience would find beneficial or rewarding.

This investigation also provides insights into academics’ participation in digital social communities. Scholars engage with specific online communities in which they can contribute and that serve to further provide professional support. Given the investment of scholars in their digital social networks and online presence, as discussed in this paper, it would be anticipated that all scholars would passionately support the value and role of online communities as opportunities for continuous professional development. It was unexpected that the majority of scholars who participate in digital social communities only “agree” that these affinity spaces can be considered continuous professional development. Some scholars even remained neutral towards this notion and, even more, argued that making digital social communities part of their professional development can be a “hit and miss” experience. Precautionary recommendations provided by those who participated in the study emphasized reading, reviewing, engaging with, and carefully considering the information exchanged and content shared.

Conclusion

In addition to being a space for casual chatter, digital social networks used by academics provide a sense of belonging to a community, opportunities for interactions within and across countries, and additional learning resources and research collaborations. Professional growth via digital social networks is generated through the social sharing and refining of ideas in a network or community with a common domain (Romero-Hall 2017). This research aids in understanding connected scholars’ practices when using digital social networks in their professional endeavors. It helps illustrate the many benefits for teaching, research, and professional development that come into play in these affinity spaces. Yet, it also calls attention to and identifies an array of challenges that are present for scholars who choose to connect and share their professional life on digital social networks. This research serves as a venue for discussion for other academics who wish to leverage these affinity spaces for teaching, research, and socializing while providing an overview of the good, the bad, and the ugly. This work also has implications for administrators in higher education because it calls attention to the need for institutions to recognize and incentivize scholars who value and sustain this practice of open science in digital social networks despite the challenges. Currently the practice of network scholarship lacks academic merit and institutional support, which weakens academics’ incentives to adopt open digital practices (Manca & Ranieri 2017).

Future Research

In this research, we have looked at the results based on certain professional demographics (i.e., institutional rank, type of institution) provided by the participants in this investigation. It would be beneficial for future research endeavors to further explore and consider scholars from across varied socioeconomic and racial groups. We need to better understand how tradeoffs are maneuvered across the different identities of scholars. What disparities can be identified in the ways digital social network use benefits and harms scholars of different income, education, cultural, and ethnic backgrounds? Also, participants in this investigation primarily reside in North America. Future research could focus on exploring academics in specific geographical regions (i.e., Latin America, Africa, Australia, etc.) and offer the option to engage with the research instrument in their preferred language.

Data Accessibility Statement

Data and materials for this investigation can be shared, if requested in writing via email to the corresponding author.

Ethics and Consent

This research was approved by The University of Tampa.

All participants consented to participate in this investigation.

Funding Information

This project was funded by a Research Innovation and Scholarly Excellence (RISE) Grant (GR3143) from The University of Tampa to Drs. Lina Gomez-Vasquez and Enilda Romero-Hall.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.