Introduction

The recent Covid-19 pandemic caused educational chaos, forcing some institutions to provide education online and students to study from home. However, online education can be challenging for students especially those in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) where the availability and use of technology in education are not widespread (Utoikamanu 2019). Apart from availability, other factors such as the cost of online education, network issues, poor power supply, and varying levels of digital literacy among students can hinder effective online learning (Omwenga 2022; Shrestha et al. 2021). The pandemic has shone a spotlight on inequality, particularly in LMICs where there is a pernicious digital divide among citizens that shows no signs of abating (Baidoo-Anu, Gyamerah & Munezhi 2023; Mathrani et al. 2021; Dawadi, Giri & Simkhada 2020).

It has been widely argued that the Covid-19 pandemic has had a serious impact on equitable access to higher education in LMICs (Devkota 2021; Gautam & Gautam, 2021; Nyerere 2020). However, to the best of our knowledge, there is little research on the specific impacts of the pandemic on higher education in LMICs. Most importantly, university level students’ accounts of their experiences during the pandemic in these countries are very limited (Baidoo-Anu, Gyamerah & Munezhi 2023; Martins et al. 2021). Thus, this study aimed to understand the impacts of the pandemic on equitable access to higher education in two LMICs, Kenya and Nepal. The research contributes to the overall goal of improving access to quality education and support for students and teachers in such countries.

Literature Review

Online education during the pandemic and relevant challenges

The sudden adoption of online learning during the Covid-19 pandemic is one of the factors that has led to questions around equitable access to education, technology and the internet, as well as students’ digital capabilities to learn online (Wekullo et al. 2022; Czerniewicz et al. 2020). Gyamerah (2020) points out that although online education offers many benefits, it can widen existing inequalities, if all necessary measures are not taken into consideration.

Universities in LMICs were facing multiple challenges even before the pandemic. The sudden, but compulsory, shift to online education exacerbated these challenges. For instance, Khan et al.’s (2020) study indicates that most lecturers in Bangladesh do not have the necessary skills to teach online, and students lack the skills required to take part in an online course. They contend that many students are at a disadvantage as they do not have good access to digital devices. In the context of the impact of the pandemic on higher education in Ghana, Adarkwah (2021) reports some major challenges such as cost (i.e., online learning is expensive for most students), and a lack of access to learning platforms, ICT tools, internet and electricity. Similarly, Anyonje et al. (2022) claim that major challenges of online teaching in Kenyan higher education include poor internet connection, non-affordability and inaccessibility of online platforms, and poor attendance by the students. Kimiti (2022) states that the pandemic encouraged teachers to introduce innovative teaching strategies in Kenyan universities, but “the quality of the curriculum implementation was significantly compromised. This was attributed to poor network, limited technical skills on use of online platforms by lecturers and systemic failures” (Kimiti 2022: 1).

The above studies also provide some evidence that the pandemic has had a considerable impact on equitable participation in education in LMICs. According to Khan et al. (2020) lecturers expressed concerns for students who were marginalised due to poor connectivity and a lack of access to digital devices. This validates Oloyede, Faruk and Raji (2022) and Dube’s (2020) observations on the pandemic’s impact on the education sector in South Africa, that online learning excludes many learners from participating as they do not have good access to technology and learning management systems. Similarly, in the context of Nepal, Devkota (2022) argues that inequalities in Nepalese higher education are reinforced through online education mainly because of “a lack of strong pedagogic support for students from disadvantaged and marginalised spaces, including those with low proficiencies in English and technological skill” (Devkota 2021: 145). Kunwar, Shrestha and Phuyal’s (2022) findings provide further evidence to Devkota’s claim when they highlight that university level students’ differential access to technology produced social inequalities in Nepal. The authors argue that more students from rural and disadvantaged communities dropped out from their studies during the pandemic. However, more exploration is needed to fully understand the real challenges faced by students.

Adding to the inequitable access to education, a mental health crisis has been emerging because of the pandemic since many students lost access to services that were offered by universities. Students with limited digital skills and resources were particularly affected (Shrestha, et al. 2021). Many experienced an increased level of anxiety and depression (Grubic, Badovinac & Johri 2020). In a study of 874 university students in Bangladesh, Faisal et al. (2021) found that 72% of students had depressive symptoms, 40% had moderate to severe anxiety and 53% showed moderate to poor mental health status. Similarly, Shrestha et al.’s (2021) research showed the noticeable negative impact of the pandemic on university students’ and teachers’ mental wellbeing in Bangladesh and Nepal. In another study, Makhado et al. (2022) reported that undergraduate students and their teachers in Kenya experienced elevated anxiety during the pandemic. However, they used several coping strategies such as online chatting with friends, watching films and participating in online vocational training to deal with the challenges.

Even though the global discourses on the pandemic and its impact on education are growing, very few studies have been conducted to explore the anxiety and uncertainty caused by the educational closures and the potential inequality in access to higher education (Khan et al. 2020). While issues such as cost, digital skills, internet connectivity and training in low-income economies have been given heightened importance (Chan 2020; Farhana & Mannan 2020; Jordan et al. 2021) and literature on equity and inclusion in online learning is emerging globally, the topic of online learning in Nepal and Kenya has not been adequately researched and published. Therefore, this study set out to address the following questions:

How has the Covid-19 pandemic affected equitable and inclusive access to higher education in Kenya and Nepal?

What strategies have been used by universities/educators and local communities, including families, to enhance equitable and inclusive access to quality education and mitigate learning losses?

Research Contexts

This research explores impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic on higher education in Kenya and Nepal. Existing research suggests that the pandemic crippled education systems in both countries. For instance, Nyerere (2020) notes that her studies of Kenyan universities pre-pandemic highlighted challenges in adopting online education including lecturers’ and students’ limited digital skills, scarce online content, limited internet, and frequent electricity blackouts. Similarly, Shrestha et al. (2021) highlight some challenges that university students and teachers faced during the pandemic in Nepal. Laudari and Maher (2019) further point out two types of barriers to online university education in Nepal: external barriers, such as lack of resources and training, unconducive policy and administration, rigid curriculum and assessment; and internal barriers, which relate to teachers’ beliefs, motivation and attitudes towards technology.

Although our research is not a comparative study, it brings together experiences from two contexts that share some similarities. Both countries adopted British colonial educational policies and practices. “Whereas Kenya was physically colonised by Britain, Nepal was and still is ideologically colonised by the west”; thus, education in both countries has been impacted by Western ideologies (Nganga et al. 2021: 42). In addition, our contextual knowledge gained from previous research conducted in these countries (Dawadi, Giri & Simkhada 2020; Coughlan et al. 2023; Goshtasbpour et al. 2022) gives us a solid foundation for the study. We had some awareness of local pandemic-related challenges and considered it important to understand how students and teachers were dealing with them and what could be learnt in terms of implications for future digital learning environments. We aimed to obtain insights and an enhanced understanding that can inform future educational planning and policies for equitable access to higher education in Kenya, Nepal and perhaps other LMICs.

Conceptual Framework

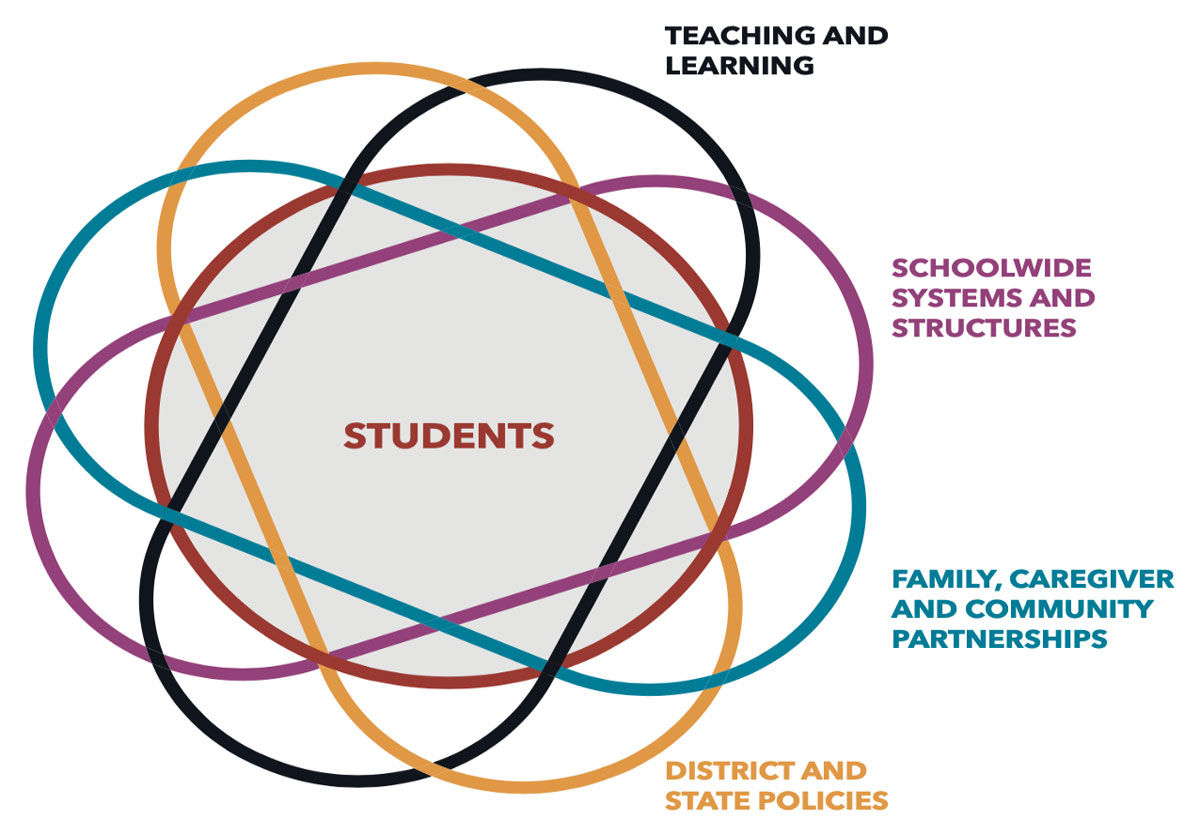

This study is guided by the Building Equitable Learning Environments (BELE) framework (BELE Network 2020) which shows how to foster equitable learning opportunities for students to enhance their learning experience and outcomes. The framework was originally developed for the US context and highlights a need to co-develop education systems in partnership with families and communities while putting student experience and development at the centre, as shown in Figure 1. It encourages the achievement of this through four domains:

“teaching and learning”, which focuses on creating meaningful learning experiences as the primary goal of an equitable learning environment;

“school-wide systems and structures”, which refers to the organisation of a learning environment (such as a school or university) where resources, staff and opportunities are aligned to support learning and teaching;

“family and community partnership”, which emphasises a shared vision, authentic collaboration and trusting relationships among families, communities and learning environments;

“region and state policies”, which stresses that regions and states must provide resources for the successful implementation of the first three domains (BELE Network 2020).

Figure 1

Building Equitable Learning Environments (BELE) Framework.

The BELE framework has been used in this study because of its comprehensive view of factors contributing to an equitable learning experience and to help a) direct data collection and data analysis procedures, b) classify types of Covid-19 impact on student experiences, and c) unpack the relationship between identified impact types.

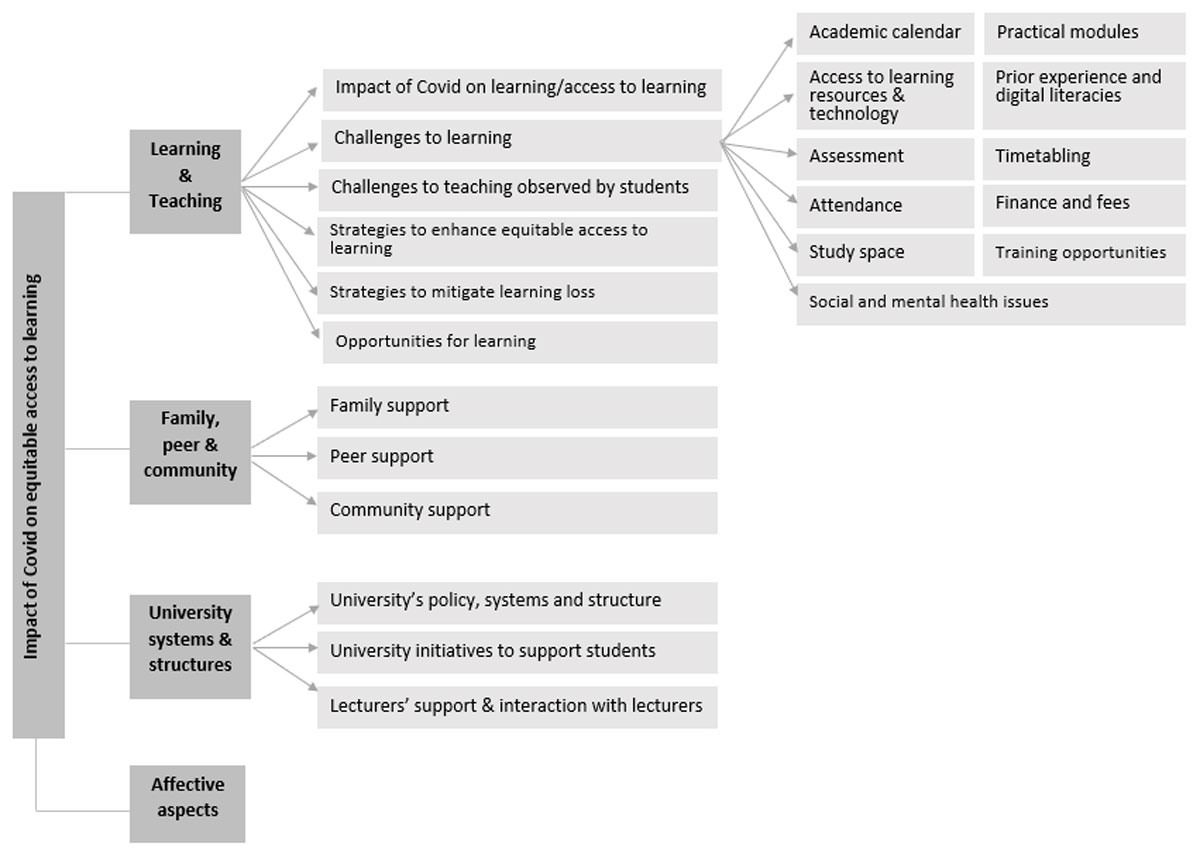

To ensure the framework takes into account the research context (e.g. the State Policy element is specific to the US and not applicable to Nepal or Kenya), a revision of the framework with the four elements of “learning and teaching”, “family, peers and community”, “university systems and structures” and “affective aspects” was considered. Figure 2 (see data analysis section below) shows the revised domains and sub-domains of the framework used for data analysis.

Figure 2

Revised domains and sub-domains of BELE Framework for data analysis.

Research Design

Participants

A total of 24 undergraduate students (11 male, 13 female) and teachers (n = 8, 4 male, 4 female) from universities in Kenya and Nepal participated in this study, with an equal number of participants – both students and teachers – from the two countries. In terms of student participants, 14 and 10 respectively were from public and private universities. The numbers for participating teachers were 5 (public) and 3 (private), thus there was a larger number of participants from public universities overall. The universities were purposively selected to cover both private and public universities, but participants took part on a voluntary basis. A total of 32 students expressed their willingness to take part in this study. Among them, 24 students were selected to have a gender balance.

In the context of Nepal, half of the students were in the final year of their study whereas the other half were in the first and second years. The majority of students from Kenya were final-year students, with a few completing the first or second year of their degrees. Teachers’ experience of teaching in higher education ranged between one and sixteen years. Most participating students did not have prior experience of studying online before the pandemic. However, half of the teachers in Nepal and all the teachers in Kenya had prior experience of delivering lessons online.

Data collection

This study employed a qualitative approach and semi-structured interviews were used to collect data. The interviews included a fixed part to enable comparison across participants, and a flexible part to maintain openness and exploration (Creswell 2014). They enabled variation in prompts to draw participants more fully into the topic under investigation (Galetta 2013).

Interviews lasted between 30 and 60 minutes and were conducted online, in English with Kenyan participants and in Nepali with most Nepalese participants, between March and May 2021. The interview questions had a focus on the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on students’ access to education, and strategies used by universities and local communities to enhance equitable and inclusive access.

The project was carried out in accordance with the British Educational Research Association’s ethics guidelines (BERA, 2018). Informed consent from each participant was obtained prior to data collection and all data were treated as confidential, promptly anonymised and stored securely. To anonymise the data, each participant was assigned a code indicating the role [student (S) or teacher (T)] and country [Nepal (N) or Kenya (K)]. Thus, “SN8” represents student participant number 8 from Nepal.

Data analysis

All the interviews were transcribed (and translated where required) and transferred to NVivo 12 for coding. In order to maximise the overall depths of the analysis, both top-down and bottom-up approaches were utilised. A top-down coding based on the BELE framework was used as the starting point, with the codes: university systems, structures, and policies (e.g., university initiatives to support students and lectures); teaching and learning (e.g., access to learning resources, challenges to learning/teaching); family and community support to students; and state policies. However, relevant information in the data was also considered for better understanding of the research issues. Emerging or open codes included affective aspects (e.g., risk, compassion, and issues related to mental wellbeing); use of social media for educational support; and prior experience with online teaching and learning.

Findings

Findings of this study are organised into four main themes based on the BELE framework revised domains. Under each theme, results from students’ interviews are first reported. These are followed by findings from teachers’ interviews for a more comprehensive understanding of each theme. The first two themes – Learning and teaching and Affective aspects – address research question one and reveal how the pandemic affected learning and teaching as well as equitable access to education. The last two themes – University systems and structures and Family, peer and community support – are related to the second research question and show the initiatives deployed by universities, families and local communities to enhance access to education and mitigate learning losses.

Learning and teaching

The findings reveal that higher education in both countries was considerably affected during the first year of the pandemic. Almost all participants reported that their universities were closed during the first few months of the pandemic, though they resumed their activities remotely after three to four months of closure. Many students reported that they were not able to engage with online activities for several reasons, namely lack of access to the internet, financial constraints, lack of appropriate digital devices, poor connectivity and power cuts (particularly in Nepal):

Many students are from rural parts of the country and they had no access to the internet (SN5).

They [friends’ parents] depended more on other sources of livelihoods which were cut because of that pandemic. And so the students’ parents are not able to purchase them those gadgets, and maybe bundles because it requires funds (SK19).

All students who managed to attend online classes reported that they were not as effective as face-to-face classes:

I couldn’t ask questions to my teachers as they would not be able to hear me because of poor network […] I could not listen to teachers properly and videos would be off quite frequently (SN1).

There were several indications that students faced more challenges in engaging with modules or courses that included hands-on activities (e.g., experiments in online labs) or experiential learning:

Another one is the practical courses were also affected; especially we natural science geographers were affected. We were not able to go to our fields to collect data (SK1).

Engaging with the assessment seemed to be another major challenge for most students. They reported a variety of factors such as being removed from the online exam due to technology failure, difficulty in concentrating due to doing the exam from home with family present, not being able to access the exam questions due to poor connectivity, or unpaid fees. In addition, a few students reported that online exams were conducted without considering students’ difficulties:

We would receive questions around 5 to 6 minutes late and we would not get sufficient time to complete the tests (SN10).

The data also revealed that in both countries, there was a digital divide between urban and rural students:

“We are in the rural areas and the accessibility of the Internet is poor” (SK14); “We have two different groups of students. I mean there is a digital divide […] Many students in my university are from rural parts of the country. Many of them don’t have access to technology” (TN2).

Other effects of the pandemic were mainly related to “learning losses” and delay in their career progression:

During the lockdown, I didn’t carry any books with me when I went to my village as I didn’t know that the lockdown would continue for such a long time […] I forgot all the contents that I learnt before the pandemic. So, the lockdown has a huge impact on my study (SN3).

If you were supposed to finish maybe your course next year or in two years’ time, now you have to go three years. So you know, it’s going to impact on your whole sphere of education in life (SK19).

Students’ academic year losses and learning losses resulted largely from university closures and delay in conducting exams. The universities did not seem to have an appropriate plan to mitigate against these losses:

“I think our university is not in a position to mitigate students’ learning loss. They don’t seem to have any concrete plan yet to address the problem” (SN10).

The teachers reported several challenges in delivering lessons online. They included low student engagement and motivation; limited access to technology, teaching resources and data; issues with conducting course assessments; and mental and social wellbeing issues. Teachers’ challenges as reported by students provide valuable evidence of those challenges. Nevertheless, there are also indications that the pandemic offered teachers an opportunity to develop their digital skills and use technology for academic purposes.

Students from both countries reported that their teachers had difficulties in delivering lessons online, mainly because of the lack of digital skills: “We could easily sense that our older teachers were struggling with online education systems” (SN11); “It’s quite a challenge for them [teachers] to make sure even they’re audible, maybe they don’t know where the microphone is, they don’t know how to switch on their videos” (SK12).

Two of the teachers in Nepal further indicated that they did not have access to any learning management systems, and they had to depend on the free version of the Zoom platform to offer their classes.

Nonetheless, the data suggest that the pandemic also had some positive impacts. Most students reported an opportunity to learn more about technology and online education:

Despite the challenges the pandemic provided opportunities, learnt driving, swimming, farming. Online classes were an awesome experience. Some got a source of income like cryptomania bought and sold bitcoins online (SK17).

Additionally, the pandemic seems to have positively affected peer support practices. Students reported that they supported their peers in several ways, such as,

Helping each other understand course content:

You and your friends would form a group and then you would have discussions. Not in class, yeah, not the class discussions but your own discussions in Teams (SK15).

Sharing learning materials (and class notes):

I didn’t have any books. I just had our course syllabus. My friends sent me the syllabus via Facebook (SN10).

Sharing information about online classes:

We also share information, in case they have anything they know, they share on WhatsApp. So, we communicate constantly (SK26).

Helping each other cope with stress:

There are a few of my colleagues who some of their parents had to be laid off from work because of the cutbacks with the lockdown. We had to organise our own weekly online sessions just to say hi to each other, you know, to smile, share a few laughs (SK26).

Providing financial support:

I borrowed money from my friends. They helped me a lot to pay my room rent. I don’t know what I would do if my friends didn’t support me that time (SN4).

Affective aspects

There are several indications that the pandemic has had some psychological impacts both on students’ and teachers’ wellbeing. Most students and teachers indicated that they experienced or observed mental health issues among their colleagues and in some cases, they even reported suicidal cases: “Quite a number of students are losing hope. We also have a lot of suicide” (TK28). The data also confirm that almost all the student participants experienced a heightened level of stress associated with their study and career:

It [the pandemic] has badly affected my career. When the university was closed, I was very much worried […] I could not even concentrate on my study. I even lost my interest in my study (SN4).

Some students from private universities, particularly from Nepal, reported that another reason for their stress or anxiety was the pressure from their teachers to work hard in their studies:

It was frustrating because teachers would not understand our problems […] We were expected to spend most of the time on our studies which was not possible for us […] they would simply tell us something like since you have free time, you can take even 2 tests on the same day. Due to this, our anxiety level was high (SN10).

The analysis suggests that teachers made efforts to support those students who were depressed or had mental health issues, as indicated in this excerpt: “There is a lot of restlessness in the students, so we try and also counsel them” (TK28).

However, some students reported that universities and teachers failed to understand their mental health issues: “I could not attend online classes because of my economic condition. It was very stressful […] But, my university didn’t provide me any support that time” (SN3).

The data revealed that teachers’ mental wellbeing was similarly affected by the pandemic. For instance, one of the teachers form Kenya stated:

There was a lot regarding motivation, you know, just trying to motivate yourself during a pandemic, to emotionally be there, be available for students, not just in terms of knowledge, also be there to listen to what they have to say and what are the problems they’re probably going through. Because that affects their education directly. So just being there while you’re also going through your own problems was a lot more difficult (TK32).

One of the main reasons for their anxiety seemed to be lack of payment during the 2020 lockdown:

I didn’t receive my salary for the online classes that I conducted during the lockdown. I have now heard that we will not be paid for those classes, which is unfair (TN1).

University systems and structures

After a few months of closure when most universities were not able to offer any teaching, they resumed their activities with a shift to online delivery. To support teachers and students with this shift, there were two main initiatives: offering training on how to teach and learn online and providing data bundles or broadband to students. For example, in Nepal, universities worked with local governments and requested them to support students. Some, particularly private ones, provided mobile data packages to students: “Later, the university provided mobile data package to students. Then, the number of students in online classes increased slightly” (SN10). Additionally, universities liaised with internet providers and asked them to provide data packages to students with subsidised prices in both countries. However, it seems that many students did not use the data packages for several reasons: lack of a smartphone, network issues and lack of information.

Nevertheless, many students (except students from Kenya’s private universities) believed that they were not supported by their universities. A statement such as “The university are not supporting us. Since first months we are supporting ourselves which is very difficult (SK1)” is a case in point. In addition, a number of students from Nepal highlighted that universities were not able to offer needs-based support. It seems that support did not take account of their economic background:

Our university offered a mobile data package to all the students. […] Instead of helping the students who did not seem to have any problem, the university could provide more support to the needy students. I think, our university could not understand that (SN11).

However, some students believed that their teachers made efforts to enhance their equitable access to learning through two main strategies summarised in Table 1.

Table 1

Teachers’ strategies to provide better access to learning, as reported by students.

| STRATEGY | EXAMPLES |

|---|---|

| Providing learning resources | They were really helpful in giving us the resources, the notes. They were understanding if you had internet issues. They would give you your exam or your cards on a later date when you are able to access the internet (SK15). |

| Use of social media for educational support | We had a Facebook Group of our class. Our teachers would drop information about their classes in our Group chat box (SN8). |

There were also less-reported strategies, such as recording online classes or responding to students’ phone calls (for those who did not have access to the internet). However, some students, particularly in Nepal, stated that they did not receive any support from their teachers, and their access was limited or non-existent: “They [teachers] didn’t support us. They didn’t do anything for us” (SN5).

Family, peer and community support

As one of the BELE framework domains emphasises community and family support as essential for an equitable learning experience, we were also interested in the community and family support that students received. Regarding community support, our findings are mixed. While some students reported that they received some support from their community, others indicated that their communities did not provide any support:

My friends would go to their village and municipality offices as there was Wi-Fi in the offices. They would visit the offices in person to download exam papers and upload their answers (SN4).

The majority of students from both countries reported that they received good support from their family members. However, a few students pointed out that their parents were not able to support them because of financial constraints:

Personally, for my parents, they were not able to pay for my school fees at the time because business had stopped, things were hard for them. That means, I could not attend the online lectures (SK12).

Discussion

The aim of the study was to explore the impacts of the pandemic on equitable access to higher education in two low/lower-middle income countries. Guided by the BELE framework (BELE Network 2020), the study reflected on how the pandemic affected teaching and learning practices in higher education, along with the initiatives taken by universities for the continuation of teaching and learning. Additionally, it explored the nature of community, family and peer support to students and the impacts of the pandemic on students’ and teachers’ mental wellbeing.

With regard to our first research question (i.e., how the Covid-19 pandemic has affected equitable and inclusive access to higher education in Kenya and Nepal), our findings indicate that the pandemic disproportionately affected students mainly for three reasons: due to students’ inequitable access to digital technology and the internet, teachers’ (and students’) lack of prior experience with online education, and low digital literacy among teachers and students. We found that most universities that were closed due to the pandemic had some initiatives to continue teaching and learning though neither teachers nor students were mentally and technically prepared for online education, and their access to the internet, the most important element of online education, was not reliable. Universities in both countries focused on transiting to online education and started online classes within a few months of their closures although private universities required less time for this transition (Crawford et al. 2020).

Nevertheless, the rapid shift from face-to-face to online provision proved to be not fully effective for various reasons. Firstly, many students, particularly from rural settings, were not able to attend online lessons due to their lack of access to the internet and technology, power cuts as well as financial constraints. These findings support Lai and Widmar (2021) who argue that rural students’ limited access to the internet and technology has been historically problematic but never as severely painful as during the Covid-19 pandemic. Moreover, they verify digital equity issues in LMICs that have been reported by previous studies (Wekullo et al. 2022; Gautam & Gautam 2021; Khan et al. 2020; Rajput et al. 2020). University initiatives such as providing data packages with subsidised prices did not seem to work well, as the support was not needs-based.

Secondly, teaching and learning activities in online classes did not seem to be effective. Most students, including students with good access to the internet, reported several challenges such as not being able to ask for clarification or not hearing the lecturer clearly when attending online classes. There are several indications that there was a low level of student engagement. Hence, poor teaching could have resulted from teachers’ lack of prior online teaching experience and potentially a lack of adequate training.

Therefore, we argue that the effectiveness of online education is context-specific (Lembani et al. 2021). To make online education effective, teachers must be well-trained, and useful resources should be available both to teachers and students. Furthermore, online education should be embedded in community practices and there should be support from community members. However, our study indicates that students and teachers were not well supported by their communities.

It is worth pointing out that most students in this study found online classes to be less effective than face-to-face classes. These findings are in line with the findings reported by Gautam and Gautam (2021) that university level students in developing countries (particularly in Nepal) feel more comfortable with face-to-face classes. As discussed above, such a preference could have resulted from the lack of access to reliable internet, technical assistance and support systems (Srichanyachon 2014).

Another group of concerns is related to learning losses caused by university closures during the pandemic. Previous research on the impact of instructional time on student learning shows that even a brief period of missed classes will have negative consequences on learning (Carlsson et al. 2015) and learning achievements (Lavy 2015). In Kenya and Nepal, universities were closed for several months and almost all the student participants in our study expressed concerns about their learning loss. Nevertheless, universities did not seem to have appropriate policies or strategies in place to support students to recover from the learning loss.

Furthermore, students’ and teachers’ mental wellbeing appeared prominently in this study. The finding of worsening mental wellbeing of students and teachers resonates with Shrestha et al.’s (2021) report that university level students and teachers from Bangladesh and Nepal experienced a high level of anxiety and stress during the pandemic. One of the main reasons behind their anxiety was the postponement of external assessments/exams, since this has a direct impact on students. It created anxiety as students were stuck in the same grade/class they had studied for a whole year which affected their career progression and occupational future. In addition, as claimed by previous studies, (e.g., Andersen & Nielsen 2019; Dawadi et al. 2020), delays in conducting assessments could have negative impacts on students’ learning. Since assessment is one of the key motivating factors for students (Dawadi 2020), universities should have looked for an alternative form of those assessments in good time.

However, there have been some positive impacts too. One unanticipated finding of the study was that the level of peer support during the pandemic increased. There was evidence that peers became a support mechanism for most students in receiving learning resources, understanding course content, coping with stress, and managing financial issues. Similar findings have been reported by Kazerooni et al. (2020) that an online peer support platform initiative developed in Iran helped university students to overcome their stress and anxiety arising from the pandemic. Huang et al.’s (2018) systematic review with meta-analysis also suggests that peer support interventions are effective in helping college students minimise their depression and anxiety. Hence, peer-based interventions seem to be a promising tool to improve students’ mental health.

Another benefit that the disruption created (for teachers) was that it enabled teachers to use social media platforms for teaching and learning purposes. It was intriguing to see that teachers made context-sensitive use of social media to support students during the pandemic. Teachers used social media to bring students together, provide information about their classes, send learning materials and promote group discussions among students about the course content taught in online classes, to enhance students’ understanding. These results add to Paudel’s (2021) findings about the positive impacts of online education during the pandemic (e.g., developing self-discipline, working more flexibly, connecting to the global community and accessing more resources) on the experience of university students and teachers in Nepal.

As Shrestha et al. (2021) have highlighted, the pandemic also offered an opportunity for both students and teachers to learn more about technology and online education. For instance, almost all the participants in this study reported that they had hardly used technology for learning before the pandemic, but they had to use it during the pandemic as there was a sudden shift to online education. Indeed, the pandemic forced educational systems across the world to offer new modalities of learning.

It is also worth pointing out that in relation to our second research question (i.e., what strategies have been used by universities/educators and local communities, including families, to enhance equitable and inclusive access to quality education and mitigate learning losses), the findings are not conclusive. While there are some indications that universities/teachers and communities offered some support to their students (e.g., providing mobile data packages and learning resources to students), this support mechanism did not work effectively as it did not cater for students’ social contexts and needs. Additionally, they seemed to lack effective strategies to mitigate students’ learning losses. Nevertheless, findings indicate that the pandemic offered an opportunity to higher education institutions to review their systems for making positive changes.

Our understanding is that the pandemic has become an eye opener for universities which have been resistant to embrace online learning and teaching. It has become a gamechanger in the way teaching and learning in higher education is happening around the globe (Gautam & Gautam 2021). Indeed, it has brought ample opportunities to reform conventional teaching-learning practices in developing countries, including in Kenya and Nepal. This means that it created opportunities to explore digital technologies for the education sector, realising the significance of the use of technology in the teaching-learning process. Indeed, ensuring quality in higher education has long been a key challenge in developing countries and it stems “from the increasing global competition, advancement in technology” (Latif et al. 2019: 769). Although the evolution of digital technologies provided new opportunities to transform higher education, there was frequently insufficient consideration for how educators can adapt new technologies to improve student learning and assessment (Rudolph, Tan & Tan 2023). Consequently, before the pandemic, most universities were using traditional teaching and assessment methods which often do not support student learning. It is pleasing to see that higher education used the crisis as an opportunity to embrace technology or new learning modes and assessment strategies.

Implications for Practice

Findings of the study have several important implications for those who offer online learning in low/lower-middle income countries. The first implication concerns students’ equitable access to the internet and learning resources. The pandemic has caused inequality in terms of access to education. In both countries, the repercussions of university closures on students’ access to quality learning have significantly widened the gap between the students who are disadvantaged and study in rural areas and those who are in urban areas. Therefore, there is a need to accelerate progress towards a fairer educational representation and participation in online education. For this to happen, learning resources must be evenly distributed. Hence, government policies in those countries should focus especially on the needs, capacities and aspirations of disadvantaged students living in rural areas.

A further implication relates to initiatives taken by universities during the pandemic. Having considered students’ low engagement with online learning, universities made efforts to support students. However, they failed to offer needs-based support, as they introduced the same support mechanism for all the students, irrespective of their economic background. Their initiatives would be more effective if they could identify disadvantaged students and offer more support to them.

The findings have also illustrated the high levels of stress and anxiety in students during the pandemic. Although almost all the students expressed some anxiety, the study did not uncover any serious attempt by teachers or universities to reduce it. It is worth noting that students’ heightened anxiety levels can have an adverse effect on their learning. Therefore, it is important to educate teachers and students on relevant coping strategies. In other words, higher education institutions should give more attention to strengthening peer support to improve students’ mental health and their learning during study from home (in the situation of a pandemic or any other crisis in the future).

One more important implication of the study concerns the assessment practices. Our findings suggest that most universities postponed their assessment of learning for nearly a year as they used solely high-stakes (final) exams rather than continuous assessment. However, as Vahid suggests in his video message, they could “replace large high-stakes exams by many smaller low-stakes activities like homework, quizzes, or small custom projects” (Vahid 2020). Had the universities considered such assessment, students would not have had to lose the entire academic year and there would not be a long-term impact on students’ progression.

Limitations of the Study

Although research presented here offers several contributions to knowledge, some limitations need to be addressed. The first limitation of the study is from a methodological point of view. This study was limited to the data collected from student and teacher interviews, but it would have benefited from additional data, such as classroom observation data and interviews with university leaders, students’ family members and local governments. Another limitation concerns the lack of rich contextual information about Kenya and Nepal for readers to better understand the findings. Building up a richer picture through more contextual information would be helpful in future studies.

Conclusion

This study provides valuable findings on students’ and teachers’ experiences of online education during the pandemic in the context of higher education in two low/lower-middle resource countries. The study revealed several reasons preventing students from engaging with remote/online activities, their multiple sources of stress and anxiety, challenges in learning interactions and assessment, and negative impacts on students’ planning for their careers. Alongside the difficulties, there were some positive remarks around opportunities to engage with new ways of teaching and learning. University initiatives that were mentioned focused on providing training and subsidized mobile data packages; however, the latter could not always be used by those who needed them. Support from teachers, peers, families and communities was valued, but was not always available. Thus, this research has revealed a hidden landscape of inequitable and sometimes painful experiences that may remain invisible to universities if students and teachers are not regularly asked about these issues and solutions are not sought.

The paper draws out several implications of the study’s findings, covering provision of infrastructure, internet access, training, needs-based support, adaptation of assessment practices, as well as noting the need for strategies to reduce stress and anxiety and to facilitate recovery of learning loss. The findings of this study and its implications should be beneficial for universities, helping them to understand the challenges that students and teachers face in online education and, drawing on some of the suggestions from our findings, to devise strategies to address their needs.

Data Accessibility Statement

Please email the corresponding author to obtain raw data.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor Christine A. Onyango (Taita Taveta University, Kenya), Mr Eliud Okumu (Egerton University, Kenya) and Dr Kamal Raj Devkota (Tribhuvan University, Nepal) for their review of the manuscript and insightful suggestions.

Funding Information

This study is funded by The Open University, PVC-RES Coronavirus Response Research Fund.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.