1. Introduction

Conventional heritage fosters territorial integration and transmits material and immaterial goods, anthropic and natural environments, to future generations. This legacy enhances culture and draws tourists, elevating quality of life and promoting sustainable economic development. Established in the 1970s, cultural tourism integrates travel with cultural heritage (CH) through the exploration of nature (Casillo et al., 2025). Enhancing CH attracts visitors and stimulates the local economy, generating significant benefits. Conserving and sustaining intricate, substantial CH assets necessitates comprehensive knowledge of their state (D’Aniello, Gaeta and Reformat, 2017). Combined cultural and natural heritage sites, particularly those with restricted access, require enhanced and constant monitoring. Effectively evaluating such sites necessitates extensive data collection and interdisciplinary expertise (Jiang et al., 2021; Condorelli and Morena, 2023; Kumoratih et al., 2023; Prados-Peña, Pavlidis and García-López, 2023). The current maintenance methods at the CH site require acknowledgment and enhancement through the application of innovative instruments and solutions (Lorusso, Messina and Santaniello, 2023; Buldo, Agustín-Hernández and Verdoscia, 2024; Cecere et al., 2024). Contemporary instruments improve decision-making (Bellini et al., 2025) evaluate CH risk factors, and monitor maintenance and risk management (Colace, D’Aniello, et al., 2025) (Colace, De Santo, et al., 2025). This study investigates the potential and advancement of innovative Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) driven solutions for the management of CH assets (Gao et al., 2024; Masini et al., 2024): we examine recent research and provide insights for CH restoration and conservation through comprehensive bibliometric analysis. We concentrate on the increasing application of AI and ML in CH conservation techniques. These technologies can support museum curators in preservation efforts (Mazzetto, 2024). AI and ML provide comprehensive data analysis to predict critical issues risks and formulate a preventive strategy, enhancing CH conservation management. This enhances conservation efforts and facilitates rapid response to unforeseen dangers (Zou et al., 2019).

AI-driven predictive models and ML algorithms facilitate cultural decision-making (Ribera et al., 2020; Casillo et al., 2023; Liang et al., 2023). These tools empower managers and expert users to implement educated protective measures and adapt their strategies for each scenario, each of which, as we will demonstrate, represents a unique case (Lazarinis et al., 2022; Rossi and Bournas, 2023; Yu and Wang, 2023). They accomplish this by analyzing intricate data patterns from several sources. Our bibliometric survey methodology provides a comprehensive overview of current and emerging trends in novel AI technologies, specifically ML and DL (Deep Learning) for CH protection. This approach facilitates the understanding of research evolution, highlights main themes, and forecasts future trajectories. These technologies prioritize ongoing research and innovation for sustainable conservation, rather than merely addressing immediate requirements. These systems evolve and acquire knowledge to align with our changing circumstances, thereby guaranteeing cultural preservation (Foka and Griffin, 2024). The bibliometric study examines AI-based conservation strategies for CH and its future potential. Advanced monitoring systems and sensors provide real-time oversight (D’Aniello et al., 2020) and automated administration of CH sites. These technologies reduce the need for manual effort and support data-driven protection strategies (Brezoi et al., 2024). This research field necessitates data analysis improved by AI and ML (D’Aniello et al., 2024). Drones and advanced imaging technologies are revolutionizing information collection and inspections by obtaining detailed photos from previously unattainable vantage points, facilitating both (Altaweel et al., 2022; Li and Tang, 2023) comprehensive and intricate views of studied areas. Innovative techniques enable decision support systems to assimilate data from various sources, thereby providing more informed recommendations for maintenance management. A deeper understanding of DL applications in cultural heritage conservation strengthens the methodological foundations of the field, promoting the development of data-driven, scalable, and non-invasive diagnostic strategies that complement traditional conservation practices (Briz et al., 2024). CNNs (convolutional neural networks) and other AI techniques may identify and assess critical details of artworks, architecture, and cultural findings. They facilitate timely and efficient protection by recognizing deterioration and other issues that may not be visible to the unaided eye. AI enhances diagnostic precision, enabling conservationists to examine factors to ascertain damage and its origins. Instruments like HSI (Hyperspectral Imaging) and thermographic inspection provide comprehensive examinations of cultural artifacts (Casillo, Colace, et al., 2024; Coïsson and Ferrari, 2024) without causing damage. Automated systems can analyze more rapidly and efficiently than experts, hence decreasing medium and long term expenses. They also furnish accurate documentation of the current status of cultural objects, and continuous monitoring observes changes over time, which is essential for understanding how shifting climatic conditions or conservation strategies impact artifacts (Karadag, 2023). AI algorithms can predict conservation outcomes or propose restoration techniques based on analogous situations (Barrile, Gattuso and Genovese, 2024). Examining artwork pigments, materials, and techniques can provide historical and cultural contexts. Climate change endangers several historic sites and artifacts; hence, certain studies focus on climate-neutral CH conservation (Foka and Griffin, 2024).

In such context, by using complex geographic data, advanced predictive models, and remote sensing technology, AI is becoming a force that can change the way things are done and break through old limitations in methodology and operations. Growing accessibility of geographical data, the emergence of sophisticated prediction models, and the incorporation of remote sensing technologies have empowered researchers to tackle extensive inquiries previously restricted by methodological and practical limitations (Choi and Kim, 2023; Liang et al., 2023; Casillo, Cecere, et al., 2024). One of the most notable applications involves using DL algorithms to automatically identify archaeological sites using satellite and aerial data and utilizing models such as MaxEnt to forecast the geographical distribution of these sites in distant areas. These approaches have shown remarkable efficacy, surpassing 90% accuracy in the mapping and identification of archaeological artifacts, even in intricate settings such as tropical forests or deserts (Basu et al., 2023; Masini et al., 2024). LIDAR technologies and CNNs have also made it possible to find hidden urban infrastructure, which gives us a lot of information about past environments (Barba, Villecco and Naddeo, 2019; Di Benedetto and Fiani, 2022; di Filippo et al., 2022; Gao et al., 2024). AI extends beyond discovery, supporting in the preventative protection of cultural treasures by analyzing multispectral data and generating DTs (Digital Twins) that model degradation scenarios and environmental risks. However, despite these advancements, there are still issues that persist: the quality and accessibility of data, the protection of sensitive areas from technological exploitation, and the lack of standardization in analytical techniques, requiring a multidisciplinary focus (Roumana, Georgopoulos and Koutsoudis, 2022; Menaguale, 2023).

This study seeks to provide a critical analysis of the primary uses of AI in archaeology, examining notable scientific advancements, ethical and practical issues, and delineating a framework for future sustainable and inclusive utilization of these technologies. This article seeks to provide a thorough analysis of AI and ML applications in archaeology, including current contributions, potentialities, and future obstacles. We specifically organize the analysis around the following research questions:

Q1: What are the main countries related to AI in archaeological site conservation?

Q2: What are the main themes and goals discussed in literature?

Q3: What are the main technological elements for incorporating AI into archaeological methodologies?

Q4: What are the main AI approaches and techniques used today to identify and map archaeological sites and their issues?

Q5: What are the open challenges and opportunities and possible future directions?

This study aims to critically evaluate the impact of AI on archaeological practice, particularly about conservation measures, rather than merely examining previous material. We strive to establish a progressive framework that responsibly and inclusively incorporates AI into cultural heritage management, acknowledging methodological deficiencies, ethical issues, and sustainability constraints. Despite the broader scope of AI in the field, which includes natural language processing, semantic knowledge modeling, and simulation-based approaches, this review does not consider these areas because we are more focused on AI aimed at the conservation of archaeological sites through predictive maintenance. Instead, this study aims to provide a systematic and critical synthesis of current advancements in the application of artificial intelligence within archaeology, with a clear objective of delineating its scope. The investigation focuses on computational methodologies rooted in computer vision, remote sensing, and DL, specifically in the areas of spatial analysis, site identification, material degradation assessment, and predictive conservation techniques.

The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 explains the systematic literature review methodology based on PRISMA guidelines. Section 3 presents a bibliometric analysis of technical trends, collaborations, and publishing patterns. Section 4 provides a review analysis showcasing AI applications in archaeology, such as predictive modeling and anomaly detection. Section 5 discusses ethical, methodological, and environmental issues, stressing the need for critical reflection and interdisciplinary collaboration. Section 6 concludes the work summarizing the findings and suggesting future directions.

2. Methodology

The review was done according to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) method, which is known for organizing and putting together scientific literature (Moher et al., 2009; Page et al., 2021). The investigation used the Scopus, Web of Science (WoS), and IEEE Xplore databases, selected for their extensive coverage of academic papers of national and international interest. We used Boolean operators to restrict the findings to English Computer Science papers of journals and conferences from January 2020 to October 2024, using keyword combinations such as ‘Archaeology’, ‘Artificial Intelligence’, ‘Machine Learning’, ‘Deep Learning’, ‘Predictive Models’, ‘Images’ and ‘LIDAR’, identifying a total of 149 items. The selecting procedure occurred in three phases. Initially, we eliminated duplicates detected within the databases. We further analyzed the titles and abstracts of the papers to assess their relevance, eliminating those that did not focus on the archaeological setting (Moher et al., 2009; Tricco et al., 2018; Page et al., 2021). We compiled a comprehensive text review to ensure that the final analysis included only papers that met the inclusion criteria. Following this procedure, we selected 37 relevant articles, which met specific criteria. We included research that demonstrated the practical applications of AI and ML in archaeology, with a focus on preserving cultural assets, utilizing geospatial data and remote sensing methodologies, and creating prediction models. Articles restricted to non-archaeological settings or only centered on algorithms devoid of practical applications were omitted.

The primary goal was to collect and synthesize peer-reviewed research publications that discuss the application of AI methods in archaeology and the conservation of cultural assets. Special emphasis was placed on empirical studies that delineate or evaluate AI techniques in operational contexts, encompassing site discovery, structural monitoring, risk modeling, and decision-making processes pertinent to heritage management. The literature discovery was formulated using the following research query:

Query{( archaeology OR ( archaeological AND site ) OR ( archaeological AND park ) ) AND ( ( artificial AND intelligence ) OR ai OR ( machine AND learning ) OR ml OR ( deep AND learning ) OR dl OR ( predictive AND models ) ) AND ( sensors OR iot OR ( internet AND of AND things ) OR images OR lidar )}

This composite query was conducted across three esteemed academic databases: Scopus, Web of Science (WoS), and IEEE Xplore.

The aggregated queries yielded an initial collection of 358 documents, comprising 175 from Scopus, 116 from Web of Science, and 67 from IEEE Xplore. Duplicate entries, identified through metadata analysis, were systematically removed, resulting in a refined collection of 149 distinct articles. A two-phase evaluation approach was employed to assess the relevance of each title and abstract to the topic and the methodological rigor of the study. Articles were chosen for comprehensive review solely if they exhibited a distinct and significant emphasis on the use of AI in archaeological or heritage-related situations. This encompassed research that proposed or evaluated AI-driven methodologies for material categorization, object identification, degradation forecasting, environmental surveillance, or the development of conservation strategies. Publications devoid of empirical foundation, methodological clarity, or pertinence to the field of cultural heritage were eliminated at this stage.

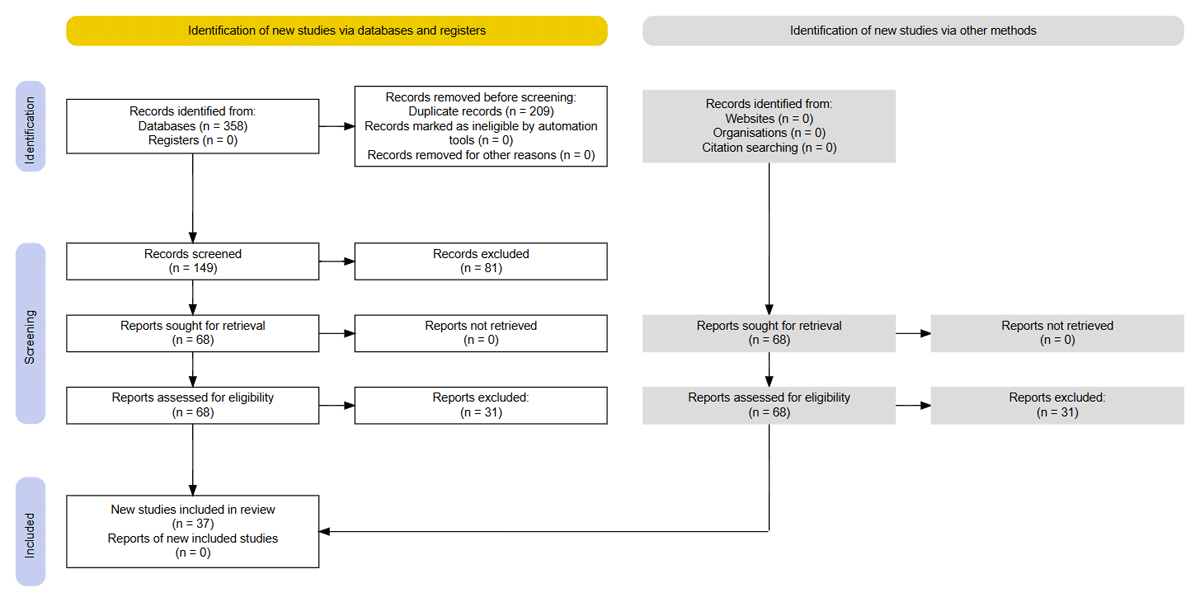

After the comprehensive review process, a final selection of 37 articles was maintained for inclusion in the qualitative synthesis. This research collectively constitutes a broad yet thematically unified dataset related to various geographic regions, technical methodologies, and conservation goals. The selection and screening procedure is illustrated in a PRISMA-compliant flow diagram in Figure 1, which delineates each stage of identification, eligibility, and inclusion.

Figure 1

PRISMA methodology (Page et al., 2021).

The data study concentrated on three primary aspects: technical applications, categorization of used technologies, and realized performance. Specifically, parameters including prediction accuracy and detection precision were assessed. We used a qualitative framework to elucidate the effects of the utilized technologies. Notwithstanding the methodological rigor used, this review has several limitations. The selection of search words may have resulted in the omission of pertinent publications published under alternative terminologies, and limited access to databases such as Web of Science may have limited the scope of the examined literature.

3. Trends Analysis

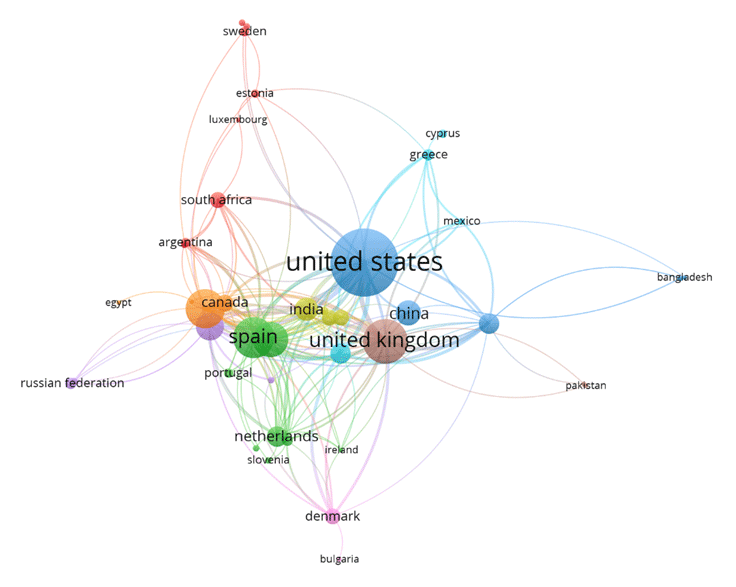

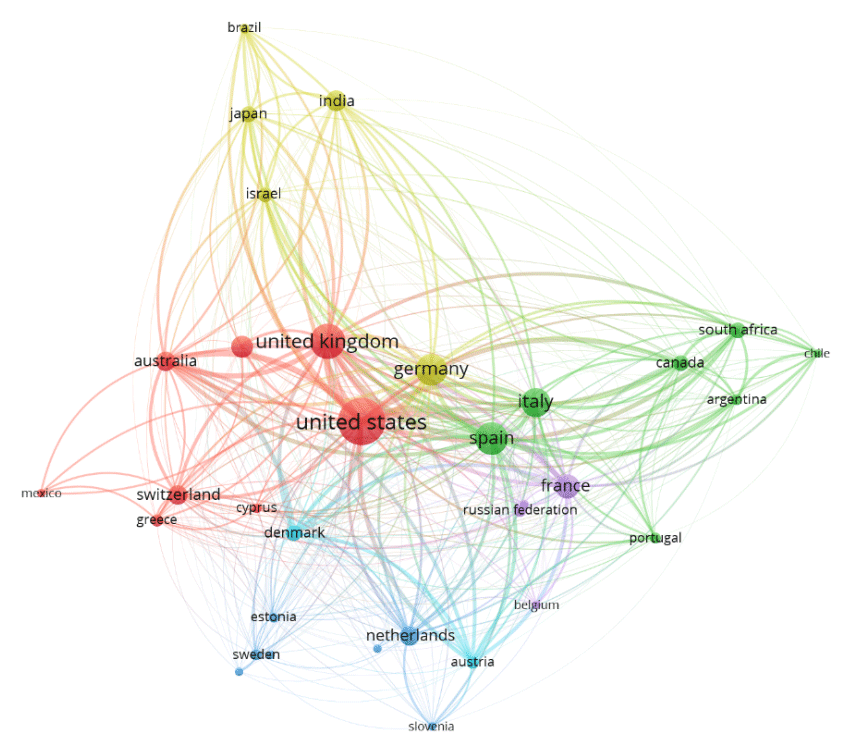

The co-authorship network graph in Figure 2 and the bibliographic connection network in Figure 3 show a strong international collaboration in the use of AI to archaeological preservation. The United States functions as a pivotal center, cultivating robust research connections with the United Kingdom, Spain, and Germany. The graph also highlights smaller, region-specific clusters, such as the partnership between Greece and Italy, motivated by their common cultural legacy and archaeological interests. Furthermore, growing partnerships with nations such as India and China indicate a worldwide acknowledgment of AI’s capacity in cultural conservation. These collaborations indicate that countries with substantial archaeological heritage are progressively allocating resources to AI-driven solutions to address conventional preservation difficulties. Notably, substantial institutional nodes emerge also in nations with extensive digital archaeology programs, whereas locations with minimal AI infrastructure appear underrepresented. This fragmentation may affect the dissemination of methodology, standards, and common datasets within the field. Such graph also exhibits a relatively thin cooperation environment characterized by few isolated clusters and limited international links. This trend suggests that a research environment is still divided by geographical and disciplinary barriers.

Figure 2

Co-authorship network graph (VOSviewer).

Figure 3

Bibliographic coupling network (from VOSviewer).

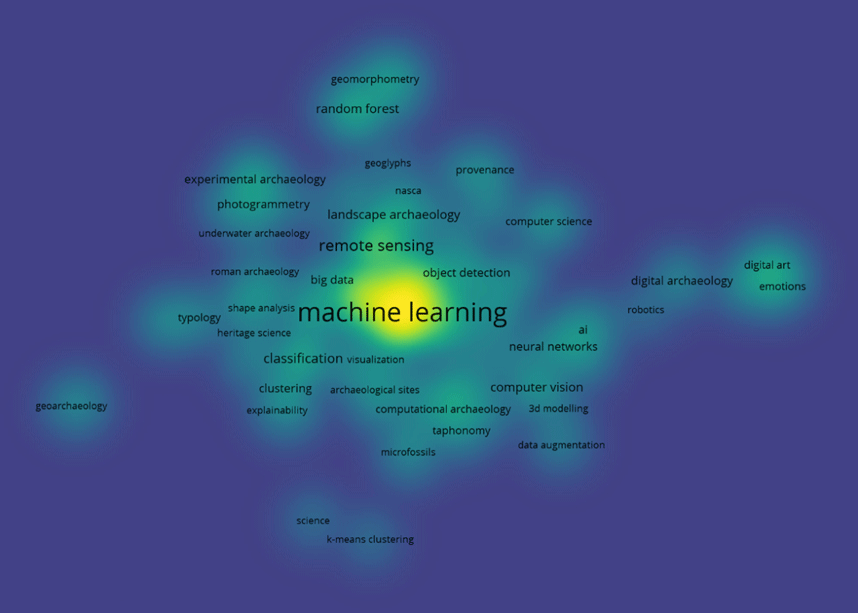

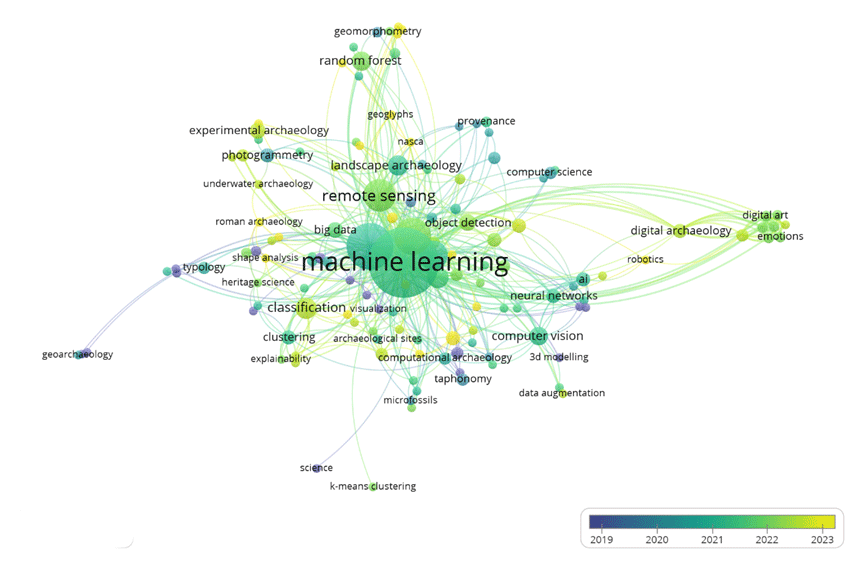

The density map of author keywords in Figure 4 underscores the significance of terms like “machine learning,” “remote sensing,” and “object detection,” reflecting the primary themes of AI-oriented research in archaeology. Figure 4, the overlay graph, depicts the temporal progression of these themes. Keywords such as “neural networks,” “digital archaeology,” and “3D modeling” have notably risen in importance in recent years, indicating a shift towards more advanced AI applications. For instance, “machine learning” remains a fundamental methodology, yet terminology like “clustering” and “classification” illustrate its varied applications in tasks from predictive analysis to artifact categorization. The overlay graph indicates a growing interest in environmental analysis and sustainability, corresponding with heightened knowledge of climate change effects on archaeological sites.

Figure 4

Keyword map (Vos Viewer).

Figure 5 illustrates the co-occurrence of terms throughout the chosen corpus. The prevalence of terms such as “machine learning” and “remote sensing” suggest that recent AI applications in archaeology are primarily focused on visual data processing and geographic analysis. Conversely, notions relating to conservation ethics, public involvement, or epistemological critique are minor or nonexistent. This theme bias underlines a technocentric approach in the sector, with inadequate integration of humanistic or socio-political components.

Figure 5

Keyword relation and density (Vos Viewer).

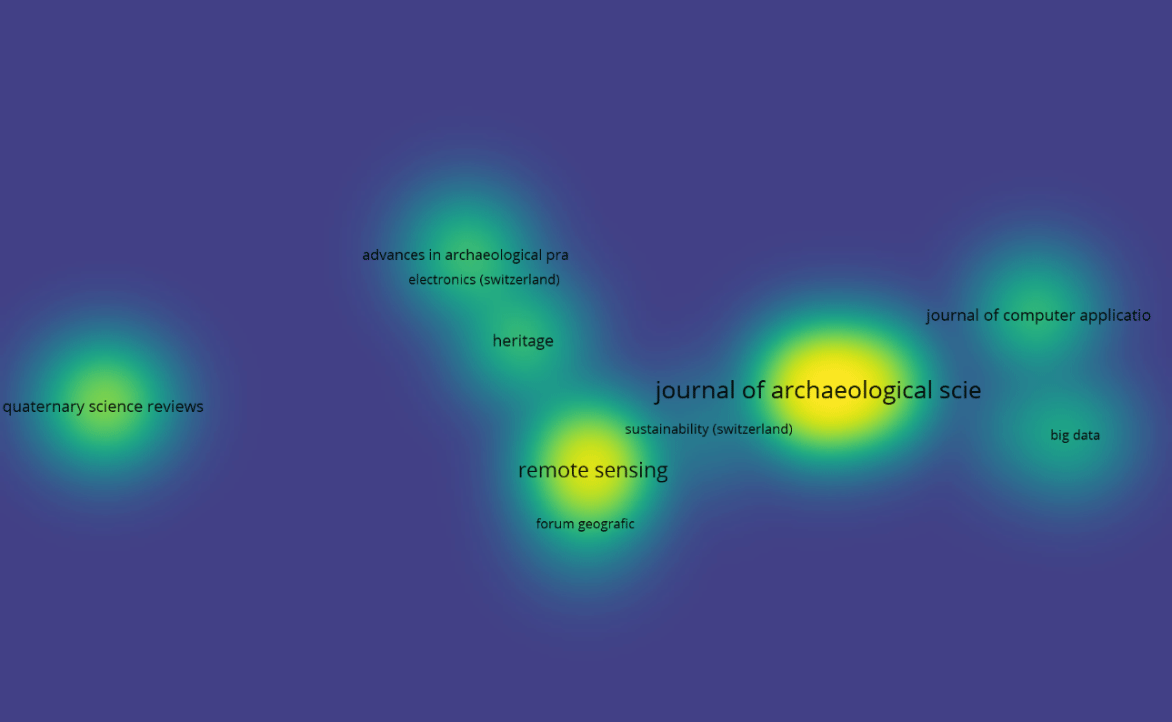

The citation source density map in Figure 6 identifies prominent publications such as the Journal of Archaeological Science, Remote Sensing, and Heritage Science as primary venues for disseminating AI-related archaeological research. This aggregation of research interest, keywords and position in the journal (Figure 5 and Figure 6) illustrates the interdisciplinary character of the area where technological advancement converges with heritage science. The figures together illustrate the growing incorporation of AI technologies in archaeological studies. The extensive use of neural networks, LIDAR, and predictive models highlights their promising capacity in tackling enduring difficulties, like the detection of buried sites and the assessment of environmental repercussions. Nonetheless, obstacles persist. Although the co-authorship graph shows an increase in international collaboration, it also reveals imbalances in contributions, with certain regions underrepresented. Mitigating these discrepancies necessitates augmented investment in capacity-building initiatives and the democratization of AI capabilities.

Figure 6

Citation sources density map (VOSviewer).

In the last twenty years, AI has swiftly transitioned from emerging technology to a crucial component of archaeological study. The surge of papers in this domain reached the highest point between 2020 and 2024, as can be seen in Table 1, propelled by the accessibility of techniques like ML, DNNs (Deep Neural Networks), and the availability of open-source datasets and cloud computing platforms (Basu et al., 2023; Rossi and Bournas, 2023). This setting has allowed archaeologists to address intricate issues, like the identification of sites in isolated regions and the analysis of extensive geographical data. The combination of remote sensing technologies, including LIDAR, with sophisticated DL methodologies represents a significant advancement. The use of segmentation algorithms as Mask R-CNN has enabled the automated identification of covered archaeological sites (which, however, require archaeological validation in the field), providing enhanced precision and efficiency compared to conventional techniques (Trier, Reksten and Løseth, 2021). Moreover, cloud computing platforms have democratized access to these technologies, enabling researchers worldwide to use sophisticated tools and interact on a global scale (D’Aniello, Gaeta and Reformat, 2017).

Table 1

Main publications 2010–2024.

| PERIOD | NUMBER OF PUBLICATIONS | MAIN TECHNOLOGIES | AREAS OF INTEREST |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2010–2014 | 79 | Basic algorithms for geospatial data analysis | Initial identification of sites |

| 2015–2019 | 132 | LIDAR, predictive algorithms, photogrammetry | Mapping and predictive modelling |

| 2020–2024 | 243 | DL, IoT (Internet of Thing) integration, DT (Digital Twin) | Monitoring and conservation |

4. Research Analysis

In this section, we propose an analysis of the research relative to AI in archaeological site conservation, organizing the articles in various types of research according to their aim and the approach used. First, we summarize the main technical components used for the integration of AI in archaeological practices, and then we categorize and discuss the literature related to AI for archaeological site protection. At the end, a summary table and discussion will be proposed.

4.1 Main technical components for the integration of AI in archaeological practices

The application of AI in archaeological techniques is predicated on three technical pillars: data gathering, sophisticated data processing, and predictive modeling. Technologies such as LIDAR, UAVs (Unmanned Aerial Vehicles) equipped with multispectral sensors, and high-resolution satellite imagery facilitate the collection of extensive spatial and spectral data, even in remote areas. During the data processing phase, deep learning architectures are employed to discern intricate patterns and characteristics. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) (Lecun et al., 1998) are prevalent models that function by sequentially applying convolutional filters to input images, thereby extracting hierarchical spatial features that are proficient for classification and object recognition in archaeological imagery. U-Net (Ronneberger, Fischer and Brox, 2015) is commonly utilized for pixel-wise segmentation tasks, which is crucial for delineating archaeological features. This symmetric encoder-decoder network integrates low-level spatial resolution with high-level semantic information via skip connections, facilitating precise feature localization. Mask R-CNN (He et al., 2017) enhances object recognition frameworks by incorporating a concurrent segmentation branch, facilitating instance-level segmentation, especially advantageous for distinguishing architectural features or artefactual clusters from intricate backdrops. RetinaNet (Lin et al., 2017), designed to tackle class imbalance in dense object recognition, utilizes a focused loss function that enhances the model’s capacity to identify uncommon or nuanced characteristics that are rare but frequently encountered in archaeological datasets marked by sparse distributions. PointConv (Wu, Qi and Fuxin, 2019) is a model designed explicitly for three-dimensional spatial analysis, operating directly on unstructured point cloud data. It utilizes convolutional operations in 3D space without requiring voxelization, making it particularly efficient in handling LIDAR and photogrammetric survey data. These models serve as both analytical tools and frameworks for interpreting archaeological data. Their incorporation into field processes, such as drone-based surveying of pipelines, has enabled the scanning of vast historical sites with millimetric precision, thereby expediting documentation and reducing operational expenses. Predictive modeling, frequently augmented by GIS-based spatial analysis, utilizes these extracted traits to identify regions of interest or prospective cultural significance, hence refining field operations and conservation planning (Fulton and Darr, 2018).

4.2 Recent applications of AI for the detection and mapping of archaeological sites

AI technologies have transformed the methodologies used in the surveying and mapping of archaeological sites. By analyzing multispectral photos and using automated identification algorithms, funerary monuments, ancient infrastructures, and settlements have been identified with over 90% accuracy (Altaweel, Khelifi and Shana’ah, 2024). An example is the use of MaxEnt in southwestern Algeria, where models using environmental data effectively forecasted the distribution of ancient urban sites, with an AUC of 0.859 (Garrido et al., 2021). In intricate settings like the Mayan tropical jungles, the amalgamation of LIDAR with CNNs has facilitated the mapping of whole concealed towns, offering an extensive perspective of the historical terrain (Richards-Rissetto, Newton and Al Zadjali, 2021). An especially interesting breakthrough is the development of three-dimensional DTs of archaeological sites, which allow for the modeling of erosion and degradation scenarios and therefore prompt conservation efforts (Sizyakin et al., 2020).

4.3 Archaeological Locations

This study reveals that authors exhibit considerable interest in proposing and researching methods for identifying new places or entities inside current locations. Numerous projects include different sorts of photographs, including instances that incorporate both photos and 3D data from ALS (Alternative Light Sources). Other studies use conventional ML methods applied to predictors, often reflecting data obtained from sensors. Literature on issues detection at archaeological sites is limited, however there is a growing interest in this field.

4.3.1 Visual representation

The study (Tao et al., 2023) presents a methodology for identifying historic centers with DL techniques. The process includes an automated technique for identifying settlements in remote sensing photos using a DL algorithm, coupled with precise computation of their geographical coordinates. This study was conducted in the Conghua region (n area located northeast of Guangzhou, Guangdong Province, southern China), a rapidly developing area that preserves several ancient settlements. Two identification models were evaluated to ascertain a more appropriate recognition procedure, one for picture classification and the other for object detection. A GIS database was used to display the locations of communities in the past. The researchers determined that the picture classification method, VGG16, achieved an identification accuracy of 90.79%. Nevertheless, the visualization of the test data indicates that the selected region is not identifiable as a settlement, but rather the adjacent surroundings. The object detection algorithm, Retinanet, achieves a detection accuracy of 95.61%, demonstrating its precision and efficacy. The selected method identified 1531 historical sites in the Conghua region, being able to determine their geographical coordinates. The study broadened the target detection capabilities of remote sensing imagery using DL algorithms, expanding beyond individual structures to include group patterns and intricate terrain features, therefore promoting the convergence of landscape conservation and AI technology. This time-efficient method may significantly enhance the identification and field investigation of quickly evolving archaeological evidence and provide a robust foundation for creating conservation policies.

The publication (Altaweel, Khelifi and Shana’ah, 2024) presents an innovative method for the automated identification of archaeological elements using three-channel pictures obtained from UAVs. The authors created an application using the Mask R-CNN for instance segmentation. The objective is to provide a GUI-based tool for applying annotations to train neural network models, construct segmentation models, and categorize picture data to enhance the automated identification of archaeological elements. The suggested method is adaptable and applicable in several situations, despite being evaluated using datasets from the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Oman, Iran, Iraq, and Jordan. The training data facilitated the identification of deteriorated structures, including funerary areas, remnants of exposed edifices, and other surface characteristics in deterioration. The technique further delineates other classes and assists users in developing their own training-oriented methodologies and feature identification classes. This model attains an accuracy above 0.9. The authors recommend further dissemination of UAV picture data via publications and open public repositories to enhance accuracy. This method, prevalent in other domains using UAV data, is increasingly necessary in CH and archaeology to enhance data exchange and the formulation of more precise models. The tool is included among the project deliverables.

The objective of (Trier, Reksten and Løseth, 2021) is to develop technologies that enhance the mapping of the Norwegian terrain, facilitating the production of a comprehensive map of extensive regions within realistic time and budget constraints. The study primarily examined three categories of cultural assets often present in diverse Norwegian landscapes: mounds, deer traps, and coal kilns. The Faster R-CNN, a DNN for object recognition in natural pictures, is used to identify these properties in ALS data. In a study with 737 test photos (16.6 km²) not included in the training set, 87% of the natural and putative historical heritage assets were correctly classified (consumer accuracy). Merely 1% of the CH components were misclassified; nevertheless, 13% of the instances were unrecognized. However, the reference photos are all very small (150 m x 150 m) and each contains at least one CH item, perhaps resulting in a larger false positive rate over a whole landscape.

The publication (Anttiroiko et al., 2023) presents comprehensive research on the identification of tar producing kilns, a significant but undervalued archaeological phenomena, in the northern boreal forest of Finland. The authors developed a semi-automated method for identifying these structures via high-density ALS data and a U-Net CNN. The U-Net module was designed to identify and categorize the archaeological remnants of tar furnaces using ALS data. The suggested system demonstrated remarkable efficiency, achieving an overall accuracy of 93% in kiln detection. This methodology enabled the finding of several previously unidentified furnaces, markedly enhancing the understanding of tar kilns in each study domain. The analysis indicated that this DL-based technology is more accurate, expedient, and capable of encompassing wider regions than manual detection. The algorithm sometimes allocated many polygons to a single archaeological feature, resulting in complications.

Grilli et al. (Grilli and Remondino, 2020) present a ML-based approach for classifying 3D architectural heritage point clouds with a focus on generalisation across diverse datasets. The authors use a RF (Random Forest) classifier trained on photogrammetric data of the Bologna porticoes. The datasets include five RGB-coloured point clouds obtained via photogrammetry and laser scanning, covering different architectural styles and acquisition conditions. The classification is related to architectural elements such as facades, windows, doors, columns, and more. The study shows that the trained model can generalise effectively to new, structurally similar scenarios, even with different acquisition techniques or sensor resolutions. Performance metrics across test cases show F1 scores ranging from 0.70 to 0.99 for the various classes.

In conclusion, preliminary research indicates that the Faster R-CNN is appropriate for the semi-automated identification of CH objects in high-resolution aerial LIDAR data. To enhance the system, efforts must be directed towards addressing false positives in photos that include segments of bigger regions or whole mapping areas.

The use of LIDAR technology with DL methodologies for the identification of ancient Maya archaeological sites is examined in (Richards-Rissetto, Newton and Al Zadjali, 2021). This research uses PointConv, a specialized DL architecture, to categorize Maya archaeological sites with 3D LIDAR data in point clouds, mostly from the UNESCO site of Copán, Honduras. This technique was evaluated against CNN-based processes using 2D data to determine the best successful strategy. Furthermore, data augmentation methods for tiny 3D datasets were assessed. The researchers assert that the PointConv architecture yields superior accuracy in classifying the Maya archaeological site compared to the CNN-based method, achieving 95% accuracy with the model trained via data augmentation. This result indicates a pathway for designers to directly use 3D data inside neural networks, enhancing precision and reducing model configuration time.

4.4 Determinants

The research (Mertel, Ondrejka and Šabatová, 2018), using the novel graph similarity technique, elucidates a comprehensive approach for forecasting ancient sites in the Bohemian-Moravian highlands. The study pertains to a comprehensive database of 4,153 archaeological sites. It encompasses geographical metrics such as elevation, slope, TWI, TPI, proximity to rivers, and soil properties. This methodology consists of three primary steps: associating archaeological details with the environmental characteristics of each surveyed site, iteratively comparing the diagrams of individual sites utilizing the Hamming distance technique to elucidate patterns of correlation between historical human activity and the environment, and ultimately predicting the presence of specific archaeological components in regions devoid of archaeological discoveries. The method produces an AUC (Area Under the Curve) of 0.62, signifying modest discriminative ability. Although its overall predictive efficacy is limited, it has demonstrated some value in identifying sites with an elevated probability of archaeological significance, particularly in under-documented or distant areas. The research identifies many methodological problems, including the intricacy of the data processing phase and the need for a uniform distribution of environmental characteristics throughout the study region to guarantee an accurate portrayal of each site’s geographical position. This approach provides a novel viewpoint on the realm of preventative archaeology. It illustrates how data similarity may be used to enhance research and deepen understanding of prehistoric settlement dynamics.

In this study, two models, LoR (Logistic Regression) and graph similarity analysis, are compared by choosing two distinct geographical locations for their examination. The LoR technique requires access to data about the origin and persistence of archaeological sites, resulting in challenges stemming from the frequent incompleteness or inaccuracy of archaeological information. Conversely, the MaxEnt technique, which utilizes just presence data, demonstrates more flexibility and efficacy when the number of archaeological site observations is known and constrained. The researchers assert that MaxEnt provided a more precise and dependable forecast of the LoR in both study regions. Their AUC was 0.796 ± 0.02, using 80% for training and 20% for testing. The analysis indicated that MaxEnt is mostly used in archaeology, where practitioners often encounter numerically constrained data and positive samples. MaxEnt serves as a compelling and versatile tool for conducting archaeological research, enabling archaeologists to accurately pinpoint the most promising areas for inquiry and excavation, hence enhancing the efficiency of excavations and the preservation of ancient sites. This essay underscores the significance of selecting the best suitable criteria based on the quality of the data and the aims of archaeological study (Wachtel et al., 2018).

The paper (Yaworsky et al., 2020) provides a comprehensive analysis of regression and ML techniques for predicting the locations of archaeological sites inside the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument (a protected area in southern Utah, United States, established in 1996). The research focuses on locations from the Formative Period, which extends from 2100 to 650 BP. The researchers used four statistical methodologies: GLM (Generalized Linear Model), GAM (Generalized Additive Model), MaxEnt, and RFs. Each technique was assessed using performance metrics, including AUC and true skill statistics (TSS), to ascertain their efficacy in predicting the locations of archaeological sites. The study underscores the challenges faced in predictive modeling within archaeology, mostly stemming from the lack of data about true-absence locations, which are essential for several statistical models. This issue has adversely affected the performance of GLM and GAM models. The MaxEnt method, using pseudo-absence points, has shown superior efficacy for these data sets, particularly for predictive purposes rather than inferential analysis, with an AUC of 0.88. The findings indicated that although RFs are often lauded for their precision, they may be less appropriate for datasets characterized by a scarcity of positive instances or sampling bias. The study offers significant insights into archaeology, emphasizing the need to comprehend the assumptions of any statistical model and their influence on archaeological research. This research underscores the significance of selecting the suitable procedure according to the particular aims and characteristics of the data.

Ultimately, (Imen et al., 2024) examines the applications of the MaxEnt self-learning approach to identify the locations of urban cultural sites in the desert area of southern Algeria, namely in the Saoura region. The research seeks to identify the geo-environmental parameters —slope, elevation DEM (Digital Elevation Model), distance to water, normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI), fertility, and proximity to palm groves— that significantly affect the placement of cultural sites. The researchers emphasized the superior predictive capacity of the fertility component, which constituted 94.1% of the overall weight, underscoring the pivotal importance of soil fertility in the identification of historic sites in the Sahara. The MaxEnt module demonstrated a strong capacity to forecast the locations of historical sites, with an AUC of 0.860. This signifies the model’s capacity to distinguish regions likely to harbor sites of historical significance from those that are not. The study emphasizes the significance of using a ML methodology, such as MaxEnt, to aid in the planning and protection of CH. The new approach may aid engineers and archaeologists in pinpointing regions that may harbor undiscovered ancient sites, allowing them to prevent degradation during urban or other developments.

4.5 Identification of Issues

The first work examined (Zhang et al., 2022) introduces an innovative approach using DL to detect cracks in the surfaces of clay structures. This research examines the conservation of brick cultural assets vulnerable to natural and anthropogenic deterioration, including fissures. The researchers developed a DL method to monitor fractures at the single pixel level on the surfaces of these sites. They used a diverse collection of crack image data for preparation and three DL frameworks (U-Net, Linknet, and FPN) with unique foundational designs. During this procedure, photographs of cracks from historical sites were collected, recorded, and included into existing crack picture repositories. Various metrics, including accuracy, recall, IoU (Intersection over Union), and F1 score, were used to assess the distinct models. The FPN-vgg16 method achieved the highest F1 score (84.40%) and IoU score (73.11%), demonstrating considerable potential for use in fracture detection at earthwork sites. Nonetheless, this methodology has significant limitations, including the need for a substantial training dataset and the challenges associated with deploying these systems on highly constrained embedded devices for practical applications.

Next, (Altaweel, Khelifi and Shana’ah, 2024) offers a comprehensive analysis of employing DL to observe looting activities at culturally significant sites. The learning model utilizes the Mask R-CNN framework, a CNN designed for image segmentation, which was trained on a specialized dataset of aerial images captured in the Middle East. These photos depict numerous alterations due to destruction and looting, and the module was taught to identify these particular characteristics. The training used database augmentation approaches to enhance the quantity and variety of accessible data, hence improving the module’s generalization to novel pictures. The study demonstrates that the strategy is very successful in pinpointing looting sites, with an accuracy of 93%. Nonetheless, the approach has constraints in identifying aged or corroded damage, which may be less visible in aerial photographs. The capacity for rapid damage detection is essential for timely action and the mitigation of further harm. This study examines the technological obstacles of deploying a system using UAVs and DL, emphasizing the need to address concerns related to privacy, data governance, and site accessibility.

AI and ML are transforming archaeology by offering sophisticated methods to tackle enduring difficulties in the finding, study, and preservation of cultural material. AI has shown remarkable proficiency in detecting ancient sites by analyzing satellite and aerial imagery. Advanced DL methods, such as Mask R-CNN, are used for instance segmentation, enabling the detection of funerary monuments, settlements, and ancient buildings concealed inside intricate landscapes like deserts or tropical woods. In a case study in the Maya area, U-Net and Mask R-CNN attained over 90% accuracy, significantly decreasing the time and expense of field surveys (Richards-Rissetto, Newton and Al Zadjali, 2021).

Predictive algorithms like MaxEnt have become essential instruments for identifying unknown archaeological sites. These algorithms use geographical data, including topography and soil composition, to pinpoint regions with a high likelihood of having historical artifacts. An AUC of 0.860 was found in research conducted in the Saoura area of Algeria, indicating great precision in selecting prospective sites (Imen et al., 2024). These models optimize resources, enabling archaeologists to concentrate their efforts on important regions.

Remote sensing technologies, like LIDAR, have increased the examination of archaeological landscapes, facilitating the discovery of ancient infrastructure covered by vegetation. PointConv’s integration of LIDAR technology with CNNs has achieved a 95% accuracy rate in mapping locations like Copán, Honduras. These technologies provide a more comprehensive and intricate understanding of the configuration of ancient landscapes. AI plays a crucial role in the protection of CH by using sophisticated algorithms to detect physical and environmental changes at archaeological sites. Researchers have applied DL algorithms to multispectral photos to identify early indicators of erosion, vandalism, and degradation at locations like Petra, Jordan. These technologies have facilitated the identification of risk variables that are undetectable by conventional methods, allowing for prompt treatments for preservation. Notwithstanding advancements, the use of AI in archaeology presents considerable ethical issues. The exact identification of susceptible places may heighten the danger of looting or unlawful exploitation. Consequently, it is essential to establish security protocols to safeguard sensitive data and prevent information abuse. Furthermore, in emerging economies, restricted access to high-quality datasets and sophisticated technical tools presents an additional barrier to the worldwide implementation of AI technology. The advancement of AI-assisted archaeology relies on the cooperation of archaeologists, computer scientists, and heritage conservationists. The use of open and standardized datasets is crucial for enhancing accessibility and promoting international collaboration.

Valero et al. (Valero et al., 2019) present a method for the automatic classification of defects and classification in ashlar masonry walls using supervised machine learning. The approach leverages accurate 3D point cloud data obtained through terrestrial laser scanning and photogrammetry of the main façade of the Chapel Royal at Stirling Castle, Scotland. The aim is to identify and classify defects such as erosion, mechanical damage, delamination, and discolouration, reducing subjectivity and improving efficiency compared to traditional visual assessment methods. The supervised Logistic Regression multi-class classification model demonstrates promising performance, achieving high accuracy in distinguishing defects, especially in classifying erosion, mechanical damage, and discolouration patterns, thereby indicating significant potential for broader application in heritage conservation and building maintenance.

Mishra et al. (Mishra, Barman and Ramana, 2022) use an AI visual inspection method to detect flaking, exposed walls, cracks, and detachments. They compare YOLOv5 and Faster R-CNN. The results indicate that the YOLOv5 model outperforms the Faster R-CNN model in terms of mAP, achieving a more accurate defect detection with a mAP of 93.7 percent.

4.6 From Detection to Decision-Making: AI for Long-Term Conservation Strategies

In addition to archaeological site recognition and categorization, new advancements in artificial intelligence have shown considerable promise in enhancing long-term conservation efforts for heritage sites. These applications encompass areas such as predictive maintenance, structural health monitoring, environmental diagnostics, and multi-criteria decision making. In this context, digital twins (DTs) —virtual representations of physical cultural assets— combined with Internet of Things (IoT) sensors enable real-time monitoring of environmental and structural conditions. Through the continuous aggregation of data from temperature, humidity, vibration, and pollution sensors, digital twins provide a dynamic representation of deterioration processes across time. This facilitates the simulation of diverse degradation scenarios, allowing cultural heritage managers to foresee hazards, plan timely treatments, and allocate resources more effectively (Sizyakin et al., 2020).

Besides structural modeling, machine learning algorithms using longitudinal records can produce predictive models that detect early indicators of material stress or failure. These models may incorporate many inputs, including climate trends, visitation patterns, and historical maintenance data, therefore improving the ability to evaluate site risk under various interacting stressors. Support vector machines (SVMs) and recurrent neural networks (RNNs) have been investigated in heritage asset forecasting, particularly in addressing complex temporal connections.

Hyperspectral imaging (HSI) integrated with deep convolutional neural networks (CNNs) has demonstrated effectiveness in identifying micro-degradation in frescoes, stonework, and organic materials in the realm of preventive diagnostics prior to such damage being perceptible to the naked eye (Casillo et al., 2024; Karadag, 2023). These non-invasive methods facilitate early conservation choices, reduce the need for harmful sampling, and can be integrated into ongoing monitoring systems.

Moreover, AI is being integrated into multi-criteria decision support systems (MC-DSS), providing institutional stakeholders with systematic assistance in identifying appropriate conservation solutions. These systems can reconcile technical factors (e.g., urgency of intervention, material sensitivity) with socio-economic restrictions (e.g., budget availability, heritage value, public access) and ethical concerns (e.g., reversibility, authenticity). MC-DSS systems employ approaches such as fuzzy logic, Bayesian networks, and optimization algorithms to provide transparent and repeatable justifications for conservation planning (Ribera et al., 2020).

These discoveries indicate a fundamental transition from reactive to predictive and preventive maintenance. Instead of reacting to degradation after it occurs, AI-driven technologies provide a proactive approach to heritage management, foreseeing changes, simulating uncertainties, and facilitating sustainable decision making. This transformation underscores AI’s significance not just as a supplementary diagnostic tool but as a pivotal element in the operational and strategic management of cultural assets, effectively connecting data-intensive technologies with context-sensitive conservation practices.

4.7 Summary Table

The approaches we have discussed are summarized in Table 2. The data shown demonstrate that most investigations concentrated on identifying specific CH attributes, predominantly utilizing visual datasets obtained by UAVs, satellite images, or aerial laser scanning. This research often utilizes classification or object identification frameworks, with many treating the challenge as an image segmentation issue. The most used segmentation models are U-Net and Mask R-CNN, while Faster R-CNN is primarily employed for object detection. VGG16 and ResNet are the most often utilized backbone topologies. MaxEnt) models are particularly prominent in investigations using structured predictor datasets. The performance of these techniques varies significantly among works, with accuracy, AUC, and F1 score being the predominant assessment criteria. Nonetheless, direct comparison is sometimes obstructed by different datasets, variable reporting standards, and divergent definitions of assessment criteria.

Table 2

Summary of analyzed works.

| WORK | GOAL | TYPE OF DATA | TECHNIQUE | RESULT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Garrido et al., 2021) | Detection and Mapping of Site | Predictors | MaxEnt | 0.859 AUC |

| (Altaweel, Khelifi and Shana’ah, 2024) | Issues Detection and Mapping of Archaeological Sites | Images: Three Channel | Mask R-CNN Segmentation | 93% A |

| (Tao et al., 2023) | Identification | Images: Three Channel | Classification: VGG16, Detection: Resnet | Class: 90.79% A Detect: 95.61% A |

| (Altaweel et al., 2022) | Identification | Images: Three Channel | Mask R-CNN instance segmentation | Over 0.9 A |

| (Trier, Reksten and Løseth, 2021) | Identification | Images: laser scanning | Faster R-CNN Detection | 87% correct class Less 1 % wrong class 13% not detected |

| (Anttiroiko et al., 2023) | Identification | Images: laser scanning | U-Net based semantic segmentation | 93% A |

| (Richards-Rissetto, Newton and Al Zadjali, 2021) | Identification | 2D Images and 3D data | PointConv Detection | 95% A |

| (Grilli and Remondino, 2020) | Identification | 3D point cloud | Random Forest | 0.70 to 0.99 F1 |

| (Mertel, Ondrejka and Šabatová, 2018) | Identification | Predictors | Graph analysis and comparison using hamming distance | 0.65 AUC |

| (Wachtel et al., 2018) | Identification | Predictors | Max Ent | 0.796 ± 0.02 AUC on control group 14 and 20% test |

| (Yaworsky et al., 2020) | Identification | Predictors | Max Ent | 0.88 AUC |

| (Imen et al., 2024) | Identification | Predictors | Max Ent | 0.860 AUC |

| (Zhang et al., 2022) | Issues Detection | Images: Three Channel | FPN-vgg16 Detection | 84.40% F1-m 73.11% IoU-s |

| (Sizyakin et al., 2020) | Issues Detection | Images: Three Channel | MCNC (CNN) | 0.819 F1 |

| (Valero et al., 2019) | Issues Detection | 3D point cloud | LR Multiclass | About 0.9 R |

| (Mishra, Barman and Ramana, 2022) | Issues Detection | Images: RGB | YoloV5 Detection | 93.7% mAP |

| Casillo et al., 2024 | AI for Decision Making | Predictors | KNN | 92.21% A |

| (Karadag, 2023) | AI for Decision Making | Images: Three Channel | GAN | 0,88-0,95 SSIM |

| (Ribera et al., 2020) | AI for Decision Making | Predictors | Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) | Avg 8.14 ROI |

5. Discussion

The findings presented in the previous sections demonstrate the promising influence of AI applications —specifically DL, remote sensing integration, and predictive modeling— on archaeological processes. Nonetheless, whereas technical performance measures such as AUC, precision, and segmentation accuracy demonstrate quantifiable progress (refer to Table 2), these metrics alone are insufficient for assessing the broader implications of AI integration in archaeology. This section examines the conceptual, ethical, environmental, and epistemological aspects arising from the analyzed literature and case studies, emphasizing the necessity for a critical perspective.

A primary problem pertains to data governance and spatial ethics. Many of the examined methodologies depend on publicly available geospatial datasets, UAV photography, or LIDAR point clouds for the detection, classification, or monitoring of archaeological sites. This transparency promotes innovation, but it also introduces hazards, especially when site locations are made available without sufficient protective measures. Research by Richards-Rissetto et al. (2021) and Altaweel et al. (2024) demonstrates elevated detection accuracy in regions such as Copán (Honduras) or the Middle East; however, they rarely consider the downstream consequences of data exposure in at-risk locations. A systematic method for anonymizing sensitive locational data and engaging local authorities and communities is inadequately addressed in existing research.

Another domain for examination is environmental sustainability. While deep learning systems are frequently utilized to enhance long-term conservation and monitoring efforts, their foundational computational demands include significant ecological repercussions. Training CNNs or U-Net models using multispectral or LIDAR data, as outlined in Tao et al. (2023) and Anttiroiko et al. (2023), requires high-performance hardware, often cloud-based, with significant energy consumption. Assertions concerning the “sustainability” of AI in historic conservation necessitate a rigorous reassessment due to the energy-intensive requirements of model training, data storage, and aerial survey logistics. The examined instances mainly lack such thoughts, indicating a gap between the potential of technology and environmental responsibility.

The discourse also uncovers a deficiency in methodological standardization across the examined research. For example, although MaxEnt is commonly employed for predictive modeling (e.g., Imen et al., 2024; Wachtel et al., 2018), the choice of environmental variables, resolution, training-testing split ratios, and validation metrics varies considerably, often without explanation. Likewise, image-based object detection frameworks such as Mask R-CNN or Faster R-CNN exhibit significant potential; however, they differ substantially in training dataset size, annotation methodology, and post-processing analysis. In the absence of standardized reporting procedures and compatible data structures, repeatability is constrained. We contend that implementing a fundamental set of reporting requirements, informed by PRISMA and FAIR principles, will significantly enhance the archaeological AI community.

Another component is epistemological. The growing dependence on machine learning technologies, particularly black box models, threatens to reduce archaeological practice to mere categorization and pattern extraction. This is apparent in the structuring of research that regards cultural artifacts primarily as geographical data points or spectral abnormalities. Although the technical efficacy of these methods is indisputable, they may inadvertently neglect the interpretive, historical, and social aspects of archaeological knowledge. The detection of kilns, mounds, or looting damage through CNNs (Trier et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2022) offers scalable insights but falls short of providing the contextual depth necessary to comprehend site formation processes, socio-political significance or cultural meaning without supplementary qualitative investigation. As archaeology increasingly incorporates AI, it must avoid devolving into a solely techno-centric epistemology.

Ultimately, interdisciplinarity is crucial yet underexploited. Although several contributions (e.g., Masini et al., 2024; Casillo et al., 2023) promote integrated frameworks that include architects, data scientists, and cultural managers, the majority of research functions operate within disciplinary silos. Addressing these gaps necessitates not just technological interoperability but also collaborative project design, unified terminologies, and participatory frameworks that include stakeholders throughout the research process. This is particularly crucial in resource-limited environments, where technological solutions sourced from the Global North must be carefully tailored to local contexts and goals, thereby avoiding the pitfalls of digital reliance or technological determinism.

Although several AI applications in archaeology have concentrated on detection, categorization, and recording, their capacity to facilitate long-term conservation plans is becoming increasingly apparent. Digital twins, predictive diagnostics, and decision support systems, as previously noted, signify a transformative change in the monitoring and maintenance of cultural assets.

Digital heritage can be certainly treated in more detail in the existing AI literature on archaeological sites protection. Digital heritage encompasses not only the digitization and digital preservation of archaeological data but also involves considerations of digital accessibility, long-term storage, and digital continuity. The integration of digital heritage practices with AI-driven methods should include explicit consideration of digital archiving standards, that for now is rarely considered (Clarizia et al., 2024). A lack of emphasis on metadata standards and digital archiving protocols risks producing data sets with limited future utility. AI-driven technologies also raise concerns regarding the integrity of digital heritage representations. Without robust verification processes, digital reconstructions or virtual restorations risk presenting distorted versions of heritage sites, potentially misleading public perceptions (Penjor et al., 2024). AI’s ability to rapidly produce detailed, accessible digital archives can increase risks of looting, unauthorized reproduction, or cultural appropriation if not accompanied by strict governance mechanisms.

In such a context, although the branch of sustainable AI has been gaining much importance in recent years, our analysis showed that the issues related to sustainability and ethics are still barely addressed in the archaeological domain but more generally in the CH domain. Sustainable AI is rarely treated in such field, even though it is crucial for CH because minimizing energy consumption and promoting ethical data practices directly support the protection and longevity of heritage assets for future generations (Rocco Loffredo and Massimo De Santo, 2024). In this context, it is important to develop models that deliver strong performance in classification and detection for the protection of cultural heritage, while generating less environmental impact than the deep learning models widely used today, which typically require lengthy training on GPUs and large amounts of data. Techniques of this kind would not only reduce energy consumption, with positive implications for the field of Green AI (Liu, 2025), but would also have significant repercussions in other ethical aspects. They could help establish a standard of techniques accessible to countries and research groups with limited economic resources, scarce computational capacity, and a limited amount of data, which is often difficult to obtain nowadays.

Furthermore, despite several studies emphasizing the effective implementation of AI in archaeological processes, it is essential to recognize the inherent limitations of these technologies. DL models often function as ‘black boxes’, complicating the interpretation and validation of decision-making processes. Furthermore, the growing reliance on computerized pattern recognition risks marginalizing context-based interpretative reasoning, a fundamental aspect of archaeological investigation.

In conclusion, although the use of AI in archaeology is advancing, its sustained efficacy and ethical validity will depend on resolving these overarching challenges. Future directions should focus not only on enhancing detection algorithms or increasing model accuracy but also on integrating AI technologies into a responsible, transparent, and critically reflective framework for archaeological practice.

6. Conclusions

This study examines how AI is being integrated into archaeology, identifying key developments and challenges. We performed a trend and technical analysis on the literature regarding AI in archaeological site conservation, responding to the five research questions established in the introduction. The answers are the following:

Q1: The main countries identified by our trend analysis are the United States, the United Kingdom, Spain, and Germany, but also Greece, Italy, India, and China.

Q2: The main issues addressed in these works are related to entity identification, particularly the detection of ancient archaeological sites so that they can be preserved and appreciated. Another commonly addressed goal is the identification of threats to site security, such as damaged roofs or holes dug by looters seeking artifacts and artwork.

Q3: The integration of IoT approaches and paradigms is widely used to acquire predictive data from sensors related to weather, seismic activity, proximity, and other phenomena. UAVs can also be employed to capture aerial images, while laser scanning techniques are used to acquire point clouds. ML and DL techniques, are widely applied to analyse this data.

Q4: Regarding detection, CNN-based techniques are the most used, particularly those based on YOLO or Faster R-CNN. Semantics segmentation models such as Mask R-CNN and GAN-based are also widely used, often leveraging pre-trained CNN backbones and U-Net-style architectures.

Q5: Standardized datasets are lacking, with many custom datasets remaining unpublished due to institutional reluctance. While CNN-based deep learning currently dominates the field, it requires large amounts of annotated data, raising concerns about sustainability. There is a clear need for platforms that integrate AI with BIM, GIS, and IoT for real-time monitoring. Digital twins and generative AI are emerging technologies in this space, but they remain underdeveloped. Ethical, sustainability, and logistical challenges persist, including data sensitivity and unequal access to technology —especially in lower-income regions. A collaborative approach involving archaeologists, computer scientists, and policymakers is essential for developing shared standards and sustainable solutions. Investment in open-source datasets, privacy regulations, and interdisciplinary training is crucial to maximizing the benefits of AI, while also accounting for its environmental impact in discussions around sustainability. Sustainable AI is still rarely addressed in this field, despite being critical for cultural heritage: ethical and sustainable practices directly support the preservation and longevity of heritage assets for future generations. In this context, future research should aim to achieve strong predictive performance for the protection of archaeological sites, while minimizing energy consumption, data requirements, and the need for extensive computational resources.

Ultimately, the future of AI in archaeology requires international cooperation, standardized methodologies, and ethical frameworks. This will ensure that technology supports rather than overshadows humanistic and interpretative aspects in the field. This study calls for a critical, cohesive, and multidisciplinary approach to AI in archaeology, one that prioritizes ethical use, social inclusion, and the long-term preservation of cultural heritage.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.