Introduction

Citizen science intentionally engages non-professionals in the “doing” of science, typically through contributions to the collection and/or processing of data (Bonney et al. 2009). While citizen science is often driven by scientific outcomes, intentionally designing learning outcomes for participants is an important consideration (Bonney et al. 2016; NASEM 2018; Phillips et al. 2018). Curriculum-based citizen science projects are intentionally designed to achieve specific educational goals, either for formal K–12 audiences or informal youth education programs (Bonney et al. 2016). These differ from many science-driven projects in that they have not been repurposed for learning but have been intentionally designed to support science learning from the outset (NASEM 2018). The integration of citizen science into formal educational systems, however, presents unique challenges that require specific attention (Dickinson and Bonney 2012; Roche et al. 2020). Schools operate within a highly structured system, particularly with regards to scheduling and assessment, and time and resources are needed to ensure curricular mandates are met. Despite these constraints, citizen science within the context of formal education have been shown to promote student self-efficacy, motivation, interest, and the development of science inquiry skills and stewardship behaviour (see Lüsse et al. 2022). However, despite the growing importance of citizen science in formal learning contexts, it is rarely situated within the science curriculum, and research on the learning outcomes remain scarce (Kelemen-Finan, Scheuch, and Winter 2018; Roche et al. 2020).

It has been acknowledged that balancing the scientific goals and formal learning goals for curriculum-based citizen science requires intentional design (Zoellick, Nelson, and Schauffler 2012; Bopardikar, Bernstein, and McKenney, 2023). The focus of this study was to articulate learning outcomes for the curriculum-based Intertidal Monitoring Project (IMP) and evaluate how they were being met.

Theoretical Foundations

This study is grounded in the learning sciences, which emphasize the intentional design of learning environments that support students in actively constructing their own meaning (Nathan and Sawyer 2014). A central theme of the learning sciences is that deeper understanding occurs when students are engaged in authentic activities with professionals or disciplinary experts (Sawyer 2014). As learners work alongside more experienced members of a community, they acquire the knowledge and skills required to become more central participants within the community of practice (CoP) (Lave and Wenger 1991). Having a common purpose, and doing things together to achieve that goal, builds a shared repertoire of resources, skills, and values (Carsten Conner et al. 2018). CoP theory emphasizes the common goal and shared practices that bind participants into a social entity, and common resources produced by the CoP that reify community practices (e.g., vocabulary, tools, routines, values, concepts, etc.) (Lave and Wenger 1991). The underlying premise of CoP theory is that learning is the formation of identities and meaning-making in practice; a process of coming to know (Wenger 1998). CoP is a lens that has been used to examine participation in citizen science in diverse contexts (e.g., Kermish-Allen 2019; Liberatore et al. 2018; Sbrocchi et al. 2022).

Context: Co-creation of the Intertidal Monitoring Project

In 2014, the British Columbia (BC) Ministry of Education was actively redesigning the K–9 curriculum, with full implementation planned for 2016–2017. The concept-based, competencies-driven curriculum is grounded in a Know-Do-Understand model (BC MOE n.d.). Within each learning area, the curricular content (Know), the curricular competencies (Do), and the big ideas (Understand) interconnect to foster deeper, more transferable learning. The model is reinforced by core competencies that are foundational to all learning. The curriculum emphasizes inquiry-based approaches and experiential learning that is place-based, and integrates Indigenous ways of knowing across all disciplines, including science (BC MOE n.d.). Overall, the transformed BC curriculum prioritizes the development of student competencies and graduating “Educated Citizens” that can think and act in a culturally diverse world of constant change. However, generalist elementary teachers trained to teach in a content-driven classroom expressed uncertainty in how they would implement it. Scientists from the Nanaimo Science and Sustainability Society (Ns3) proposed that authentic participation in place-based scientific research could provide students with an opportunity to develop science competencies and engage in local sustainability issues. Dr. Liz DeMattia, one of the co-founders of Ns3, initiated a partnership between Vancouver Island University (VIU) and the local school district to develop the curriculum-based Intertidal Monitoring citizen science Project (IMP). This collaboration later included Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

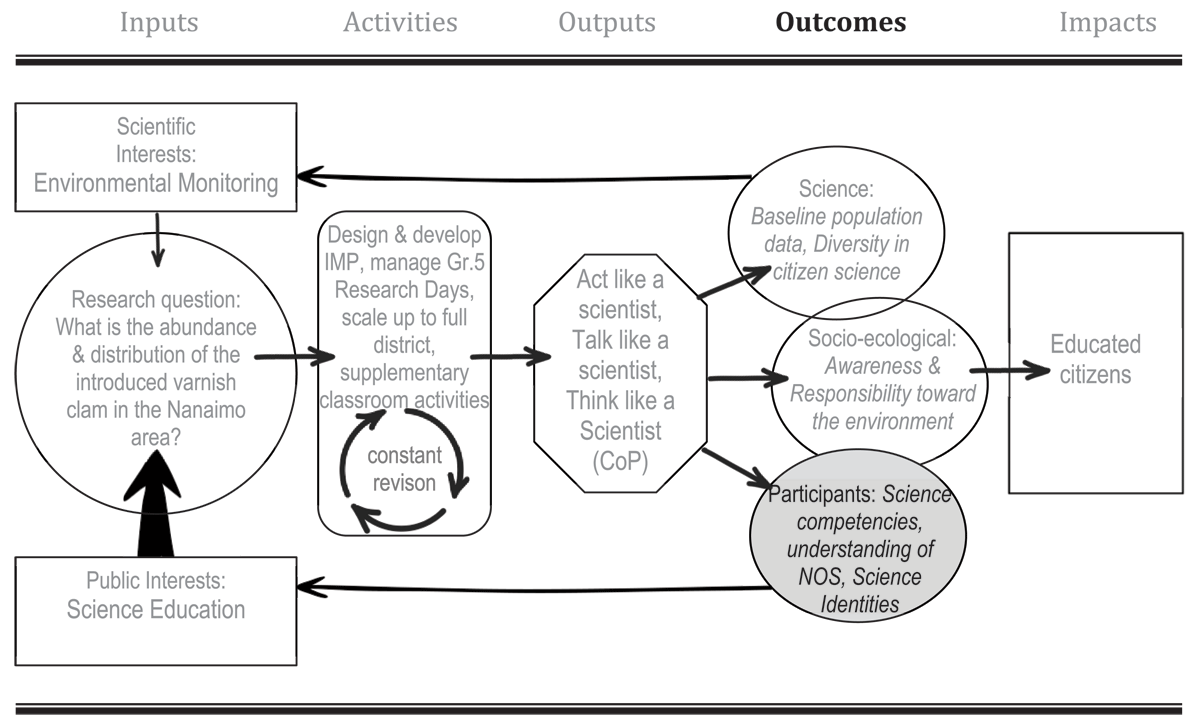

Although the design of the curriculum-based IMP evolved with each iteration, it had been developing as a conservation-in-action opportunity for VIU undergraduate students and had no formal structure. This study built on the project by situating the idea within an established citizen science framework (Shirk et al. 2012) that is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Guiding framework for the Intertidal Monitoring citizen science Project (IMP). Note this study is centered on the learning outcomes that have been shaded.

Intertidal Monitoring Project inputs

Shirk et al. (2012) emphasize that citizen science projects are collaborative efforts that must balance both scientific and public interests. After consulting with school district teachers and administrators, it was collectively determined that the development of science competencies, as defined in the BC curriculum, was the overarching goal of the IMP. The public interests were the primary driver of the IMP and are therefore represented with a larger arrow (Figure 1). The scientific inputs of the IMP were identified after consultation with Dr. Sarah Dudas, a Canada Research Chair at VIU at the time. Her doctoral research had focused on a species of clam that had been introduced to the coastal waters of BC in the early 1990s (Dudas 2005; Dudas, Dower, and Anholt 2007). Little was known about the population dynamics of the introduced varnish clam (Nutallia obscurata), but it appeared to be increasing dramatically, and there was interest in developing a fishery. Dudas was therefore interested in monitoring clam populations in locally important salmon spawning habitats. In addition, Dr. Jane Watson from VIU was interested in the intertidal distribution of varnish clams. As the only clam available at high tide, they were becoming an important winter food source for racoons (Simmons, Sterling, and Watson 2014) and shore birds (Hollenberg and Demers 2017). The scientific interests were seen as secondary and are therefore represented with a smaller arrow (Figure 1). A research question was collaboratively created: What is the abundance and distribution of the introduced varnish clam in the Nanaimo area?

Intertidal Monitoring Project activities

Activities refer to the work that is necessary to design, establish, and manage all aspects of a citizen science project (Shirk et al. 2012). The main activity for the IMP is the grade five Research Days where students participate in authentic scientific research by collecting monitoring data (Figure 1). The IMP development team designed age-appropriate data collection protocols. This included in-depth discussions about data quality, a common issue in citizen science (Dickinson, Zuckerberg, and Bonter 2010), and the challenges of working within the structure of school timetables and curricular goals (Roche et al. 2020). Sampling equipment was collected, borrowed, or made, and educational materials were designed and created.

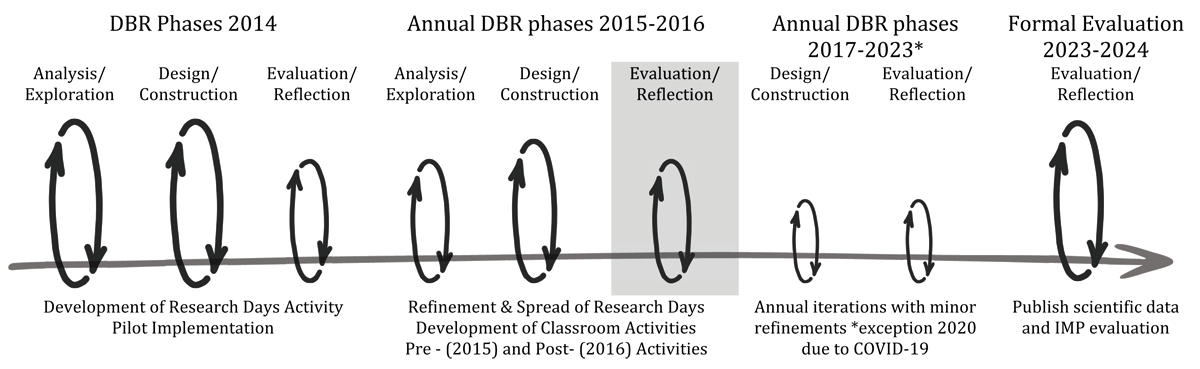

In 2015, the school district agreed to fund transportation and programming costs to ensure every grade five class could participate in the IMP Research Days. The IMP development team began responding to issues noted during the pilot and designing supplementary classroom activities. In 2016, a classroom activity was designed and beta tested, which is the study site for this research (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Design-based research (DBR) phases of the Intertidal Monitoring Project (IMP) from 2014 to 2023. Note this study focuses on an Evaluation and Reflection phase of the IMP (shaded), and the size of the arrows reflects how much time and effort went into that DBR phase.

Intertidal Monitoring Project outputs

Outputs are the initial products or results of the activities based on observations and experiences (Shirk et al. 2012). In early iterations, it was clear that participating in IMP activities provided an opportunity for students to become members of a CoP as they worked with scientists to understand a local issue (Lave and Wenger 1991). Students were doing science together, building a shared repertoire of domain-specific processes, skills, and values (Carsten Conner et al. 2018). Collectively, the IMP activities encouraged elementary students to talk like scientists, act like scientists, and think like scientists. These outputs, which aligned with other curriculum-based citizen science projects with elementary students (Chen and Cowie 2013), were therefore articulated as the IMP outputs (Figure 1).

Intertidal Monitoring Project outcomes

Outcomes are the measurable elements that result from the specific outputs of a project (Shirk et al. 2012). Within the context of environmental citizen science, these fall under three categories: outcomes for participants, socioecological systems, and science (Figure 1).

Participants

The primary goal of the curriculum-based IMP is to foster the development of science competencies, as defined by the BC curriculum (BC MOE n.d.). They fall under six categories: questioning and predicting, planning and conducting, processing and analyzing data and information, evaluating, applying and innovating, and communicating. These align with the “scientific practices and skills” of the K–12 science education curriculum in other countries (e.g., NRC 2012), and the “skills of science inquiry” in citizen science research (Phillips et al. 2018).

Based on the science education literature, two additional individual outcomes were identified. These included an understanding of the Nature of Science (NOS) and the development of science identities. Both have been recognized as potential learning outcomes for citizen science (NASEM 2018; Phillips et al. 2018). NOS frames science as an epistemological framework, or a way of knowing the world, that exists within a sociocultural context (Abd-El-Khalick and Lederman 2000). It makes the scientific processes surrounding knowledge creation more transparent and exposes any underlying assumptions. The elements of NOS are clustered in three domains: the tools and processes of science, the human elements of science, and the domain of science and its limitations (McComas 2020). Science identity as an outcome for the IMP embraces who students think they are and how others perceive them to be in relation to science (see Shanahan 2009). Do students see themselves as “being a scientist” (Archer et al. 2010), or someone who knows about, uses, and sometimes contributes to science (NRC 2009)? Research has shown that providing opportunities for students to participate in citizen science together as a class can foster identity work (Simms and Shanahan 2019).

Socioecological systems

While the development of science competencies has been the focus of the IMP, the project also brings awareness to the problem of introduced species. Socioecological issues (e.g., introduced species, habitat loss) are inherently multidisciplinary in nature as they intertwine human values, actions, and decisions at both a local and global scale. By holding the IMP Research Days in a local environment, students are provided with the opportunity to make place connections and envision themselves as environmental actors or stewards in this world (Wells and Lekies 2012; Haywood, Parrish, and Dolliver 2016). It is for these reasons that awareness and responsibility toward the environment, one of the core competencies in the BC curriculum (BC MOE n.d.), was identified as an IMP outcome (Figure 1).

Science

The science-related outcome initially identified for the IMP was the collection of reliable, long-term baseline population data on clams from important salmon spawning areas in the Nanaimo area (Figure 1). Scientists involved in the IMP were committed to publishing the monitoring data because the under-utilization of data generated by citizen science has been long recognized (Theobald et al. 2015). In 2023, funding was secured to analyze years of IMP monitoring data for Fisheries and Ocean Canada (Irwin-Borg et al. report in progress).

Diversity became an important outcome to articulate for the IMP. Research examining who is and who is not participating in citizen science indicates that there is a lack of diversity in citizen science, which can perpetuate inequities (NASEM 2018; Pateman, Dyke, and West 2021). The IMP represents a unique situation in that all grade five students in the local school district can be citizen scientists in their community. Between 2014 and 2023, more than 4,000 students from diverse cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds participated in the IMP Research Days.

Intertidal Monitoring Project impacts

Impacts are long-term and sustained changes that support improved human well-being or conservation of natural resources (Shirk et al. 2012). While the impacts of the IMP have not yet been explored, they align with the BC curriculum initiative to develop “Educated Citizens” (Figure 1) that can think critically and creatively to respond to an ever-changing world (BC MOE n.d.).

The creation of the IMP framework provided the structure needed to address the question that guides this study: How are the learning outcomes of the IMP being met?

Design-Based Research

A design-based research (DBR) approach was used for the initial and ongoing development of IMP activities. DBR was chosen because it is a systematic but flexible methodology aimed at improving educational practices through the study of interventions in complex real-world settings (Bell 2004; Wang and Hannafin 2005; Barab 2014). DBR emphasizes ongoing collaboration among researchers, practitioners, and stakeholders to provide input on the initial design of an educational intervention, the analysis of its success in practice, and its ongoing implementation and spread (Barab and Squire 2004; McKenney and Reeves 2019). NASEM’s (2018) report Learning through Citizen Science dedicates an entire chapter to intentionally designing for learning that aligns closely with DBR (e.g., linking scientific goals with learning goals, engaging stakeholders, opportunities for participants to apply what they learn). DBR was therefore seen as an ideal methodological approach to develop a citizen science project.

McKenney and Reeves (2019) developed a model for conducting DBR in education. It includes three phases that create a flexible, iterative structure for research: Analysis/Exploration, Design/Construction, Evaluation/Reflection. It also considers the common goal of creating change through the Implementation/Spread of the educational intervention. These phases of DBR have been used to intentionally design other curriculum-based citizen science projects (Bopardikar, Bernstein, and McKenney 2023). This research focuses specifically on one Evaluation/Reflection phase of the IMP to determine how the IMP learning outcomes were being met (Figure 2).

Methods

DBR calls for research to occur within representative real-world settings, and the evaluation phase is often conducted on or through the educational intervention itself (McKenney and Reeves 2019). This Evaluation/Reflection phase occurred during the beta testing of a post-Research Days classroom activity in 2016. DBR requires rich descriptions of the research context so others can judge the value of the contribution and make connections to their own context (Barab 2014). As a result, the activity will first be described and then the research design will be presented.

Study site: The Intertidal Monitoring Project Research Proposal activity

The IMP Research Days are focussed on scientific data collection, one of the most common types of citizen science (Bonney et al. 2009). However, simple data collection does not always support student-driven inquiry (Trautmann et al. 2012) and often lacks opportunities for participants to reflect on the processes of science (see Bonney et al. 2016). In response to these criticisms, a classroom activity was developed to provide students an opportunity to apply what they had learned and engage in more elements of science inquiry.

The DBR Analysis/Exploration phase included a literature review surrounding student-driven inquiry using the SocioScientific Issues (SSI) approach (e.g., Sadler, Barab, and Scott 2007). SSI uses complex scientific issues as the context for students to analyze and discuss the issue from both a scientific and societal perspective and is grounded in CoP theory (Sadler 2009). Using the SSI lens, case studies of locally relevant socioecological issues were presented in a short newspaper article format aimed at a grade five reading level (e.g., seastar wasting syndrome, toxic algae blooms). The case studies were designed to emphasize changing population dynamics in response to global issues such as climate change and habitat loss. To support students in making connections to the Research Days learning experience, relevant language was bolded in the newspaper article (e.g., monitor, abundance, distribution), and connections were made to existing citizen science initiatives.

Over three classroom visits, students (i) identified the socioecological issue in the newspaper article; (ii) designed a scientific protocol to monitor the impacted population; (iii) created a three-minute video to propose their idea; and (iv) presented their video proposal to the class and a panel of judges to compete for “grant money” to fund their research. The beta testing of the Research Proposal activity became the site for this formal DBR Evaluation/Reflection phase.

Data collection

To determine whether the outcomes of the IMP were being met, multiple types of data were collected.

Throughout the Research Proposal activity, student learning artefacts were collected. From the first classroom visit, these data included audio recordings of group work as they discussed the case study and designed a monitoring protocol to address the problem. It also included the proposal outline worksheet, with written feedback from a scientist. From the second classroom visit, data included audio recordings of group work as they collaboratively refined their research proposals and created a video using a whiteboard app. From the third classroom visit, student-generated data included the final Research Proposal video and audio recordings of their presentation, and an exit slip asking students to reflect on what they had learned from the IMP activities.

At the completion of the Research Proposal activity, a semi-structured interview was conducted with the classroom teacher. This interview used open-ended questions to capture the teachers’ perspective of student learning during the IMP activities. Questions also prompted the teacher to consider if and how the outcomes of the IMP were being met and how activities could be improved to meet these outcomes.

Data analysis

Student-and teacher-generated data were transcribed, and preparations were made for directed content analysis. This approach uses predetermined codes for researchers to identify and categorize all instances of a particular phenomenon (e.g., students developing science competencies) (Hsieh and Shannon 2005). Therefore, a codebook was first developed using provisional codes created from curricular documents and the literature (Miles, Huberman, and Saldana 2014). Twelve a priori codes were created for each of the science competencies/skills outlined in the BC curriculum (BC MOE n.d.). Seven a priori codes were created for the Nature of Science (McComas 2020) and two for science identities (Archer et al. 2010; NRC 2009). Operational definitions for each code were added to the codebook to ensure consistency during the interpretive process (Nowell et al. 2017). The first author then used the codebook to qualitatively code student- and teacher-generated data. Constant comparative analysis (Shanahan and Burke 2017) was used throughout the coding process to increase the trustworthiness of this interpretive research and ensure that emerging themes were not missed. This method requires that every time a new piece of data is added to a code, it is compared with those previously recorded for that code. Using this approach, an additional 12 codes emerged inductively (Miles, Huberman, and Saldana 2014). These were mostly related to teaching and learning (e.g., student engagement, authentic learning). To further address issues of trustworthiness, a second project member independently coded a portion of the data set (>10%), and interpretations were member checked by multiple collaborators (Norwell et al. 2017). Any disagreements were discussed and resolved. A copy of the codebook with exemplar data is included in the supplemental materials to provide transparency in the qualitative coding process.

Findings

Collecting different types of student- and teacher-generated data allowed us to evaluate how the learning outcomes of the IMP were being met. However, due to the collaborative nature of the IMP activities, only the exit slips collected individual student data that might indicate the proportion of students meeting the learning outcomes. The richest source of data came from the culminating Research Proposal presentations and teacher interview. Exemplar excerpts were chosen to support our interpretation of how the IMP outcomes were being met by the class in general.

Science competencies: outcome being met

When asked what they had learned during the IMP Research Day, 94% of students who had provided consent/assent to participate in the research and submitted an exit slip (n = 16) made comments that coded to at least one of the science competencies. Most often they coded to Conducting investigations (81%) and Observing (56%) (e.g., I learned: how to use a caliper, how to measure clams and chart data, how to identify clams). Two excerpts from the culminating Research Proposal presentations were chosen to highlight how additional science competencies were being developed during the supplementary classroom activities. The first excerpt is from the presentation that emerged from the newspaper article: City of Nanaimo Ponders Geese Cull.

S2: On Vancouver Island, we are experiencing troubles with our Canadian geese. The geese are contaminating our land with their feces.

S3: We will be monitoring the geese at Westwood Lake because it’s a fun place to swim and hang out at, but the geese are ruining the fun.

S4: What we are going to do is monitor the geese population at Westwood Lake, by putting signs up.

S1: The signs will say if you find a goose with a collar and a number, please report their number to birdwatchers.com. This way we can monitor where the geese are coming from.

S2: We will also be looking out for the tagged geese too, as well as others who may be interested. As a Citizen Scientist, we will be watching the geese at any opportunities possible. If we find an untagged geese we will be reporting them as well. We will check the website frequently to keep tabs on any geese that seem to be very active as its being spotted.

S3: The funding money will go to buy the collars for the geese, building a website and relocating geese so they can have a home. We will also need help from educated scientists to put the collars on the geese.

The above excerpt highlights the development of science competencies related to communicating, planning investigations, and problem solving.

The second excerpt is from the presentation that emerged from the newspaper article: Polar Bear Populations can be Monitored by Satellite.

S1: We are studying the polar bears and how global warming is affecting them and their habitat.

S2: The ice is melting, and the polar bears are, like, losing their homes and they are forced, well, yeah, they fall into ice and drowning.

S3: Polar bears are being forced to swim to find more ice, to sleep and to find food; and more cubs are drowning and dying from the swimming because they are burning all their fat.

S1: Food is crucial to polar bears due to burning all their fat from swimming. So when they are swimming they use up all their fat for energy to keep swimming.

S2: Which is causing them to die.

S1: Which is also causing them to die, to starve to death.

S1: [Shows 2 maps of Artic Sea Ice] As you may see the ice is moving faster than we thought. So that means that soon there will be no more ice and the polar bears will be extinct. As you can see, this is the ice picture from 1984 and this is 2012 and there is a ginormous difference between them.

S3: Now for our protocol.

S1: [shows two satellite photos – before and after] These are satellite pictures.

S2: The yellow circles are bears.

S1: The yellow circles are bears and as you can see, because this is the before picture and there’s a white dot, and that’s a polar bear, it is missing from here… and the red ones are probably just rocks.

S2: We’re using it that way because you can count the bears.

S1: And we use satellite counting because it’s cheaper than aerial counting and it doesn’t really affect the polar bears.

This excerpt highlights the development of science competencies related to communicating, processing and analyzing data and information, planning investigations, and problem solving.

In the exit interview, the teacher acknowledged that students had developed multiple science competencies during the IMP activities. We have chosen two excerpts to highlight science competencies that were not visible in the student excerpts shared above (i.e., questioning, applying, and innovating).

The questions that were being asked [after the Research Proposal presentations] and their ability to answer them. I mean that proves right there that they took it seriously. And they did learn. They even had some previous knowledge that they were able to conceptually go: I can make that connection! It did show that they had some other prior knowledge and experience that they could apply to the situation. Taking that experience in the field and looking at how the protocol was laid out then adapt and modify it to meet their species need.

…they were problem solving you know like the cruise ships. Would adults have thought OK, let’s find somebody on the cruise ships to take water samples!? [to look for toxic algae]

Overall, both student- and teacher-generated data indicate that science competencies was an IMP learning outcome being met.

Science identities: unrealistic outcome

Very little student-generated data coded to science identities. Only one student that completed the exit slip (n = 16; 6%) revealed any self-recognition of a science identity (e.g., I learned to be a scientist). More often (25%), students recognized the practices that bind scientists to a community of practice (e.g., I learned how to work with a group of scientists; you must stay in your quadrat; you may need a team to help in the field).This aligned with data from the Research Proposal presentations, where only one group referred to themselves as scientists (e.g., We are grade 5 students and scientists studying how sea life is being killed by toxic algae). The teacher did acknowledge students’ developing science identities in the exit interview (e.g., I think they were truly speaking like little scientists) but overall, the findings suggest that fostering science identities may not be a realistic outcome for the IMP.

The Nature of Science (NOS): outcome to strengthen

When asked what they had learned during the IMP activities, 31% of students (n = 16) gave responses that coded to the NOS. As noted above, this often coded to the shared methods of scientists. In the Research Proposal presentations, all groups acknowledged the collaborative nature of research (i.e., interaction of science and society). The teacher acknowledged multiple times the creativity that students had shown in designing their monitoring protocols (see Supplemental File 1: Codebook).

While all groups created a protocol to monitor a species related to a socioecological problem (i.e., shared methods of science), participant observations and researcher memos indicated that there were significant supports provided by scientists for them to be able to do this. Overall, the findings suggest that the NOS is a realistic outcome for the IMP, but more intentional design is needed.

Learning by design

Eleven codes emerged that fell under the topic of “learning by design”). Because our research question was asked through the lens of CoP theory, we focus this section on two emergent codes related to learning alongside scientists (for others, see Supplemental File 1: Codebook).

The opportunity for both students and teachers to work closely with science experts was identified as an essential design element of the IMP.

…as a classroom teacher, you can’t be a master of all things. YOU [scientist] have that specialty, you have that background, and you bring it to the classroom. Having experts come into the classroom is important. We can’t always go out.

The teacher recognized that engaging in research with scientists provided learning experiences that fostered science competencies in students.

…within that one little group there were questions the whole time. They were asking questions that were being immediately answered. And they had that background experience [as citizen scientists] so they could engage in that authentic conversation.

On the exit slips, students (n = 16) themselves recognized that they had learned about science from the team of scientists that supported them during the IMP Research Days (62%) and Research Proposal (68%) activities. Additionally, the teacher referred to her own science learning by acknowledging her initial lack of interest in teaching science (e.g., …to tell you the truth, Science is not my thing…) and how it had developed during the inquiry-based IMP activities (e.g., I thought, oh my gosh, this is how I need to approach Science! I am thinking how can I create this type of opportunity again, if this was not available). Finally, participant observations and researcher memos regularly identified the supports being provided by scientists during the IMP activities for both students and teachers (see Supplemental File 1: Codebook). Overall, the findings suggest that having students and teachers learning alongside scientists was an important design element.

Discussion

It has been acknowledged that the intentional design of citizen science projects can amplify the learning opportunities for participants (Shirk et al. 2012; Zoellick, Nelson, and Schauffler 2012; NASEM 2018). This is especially important if the goal is to integrate citizen science into formal educational contexts (Roche et al. 2020). In this study, a DBR approach informed the ongoing development of a local, curriculum-based environmental monitoring project. The DBR approach calls for research to occur within representative real-world settings, and evaluation is often conducted on or through the educational intervention itself (McKenney and Reeves 2019). This study represents a formal Evaluation/Reflection phase that occurred during the beta testing of a classroom activity for the IMP. A framework was first created, articulating the inputs, activities, outputs, outcomes, and impacts (Shirk et al. 2012). The outcomes were then qualitatively assessed to determine how they were being met. Student- and teacher-generated data both indicated that students were developing science competencies during the IMP. However, there was little evidence to suggest that the IMP had fostered the development of science identities. Understanding the NOS was a learning outcome that needed more intentional design. Students and teachers working closely with scientists emerged as an important design element of the curriculum-based IMP.

Science competencies

Engaging students in authentic scientific research is well suited to fostering science competencies or the skills of science inquiry (Phillips et al. 2018). At the end of the IMP, students and their teacher both recognized that science competencies had been developed. This aligns with other citizen science projects that have fostered science inquiry skills in elementary students (Chen and Cowie 2013; Ruiz-Mallén et al. 2016; Baptista, Reis & De Andrade 2018; Kermish-Allen, Peterman, and Bevc 2019). The science competencies visible included: identifying problems to solve, observing, asking questions, planning investigations, conducting investigations, processing data and information, communicating ideas about science using science language, innovating, and applying science learning to new situations (BC MOE n.d.). This study adds to the research showing how curriculum-based citizen science can be intentionally designed to support students “coming to know” science as a community of practice in the highly structured school environment.

Science identities

CoP theory emphasizes the formation of identities-in-action as the precursor to all other elements of learning (e.g., skills, content knowledge) (Wenger 1998). However, science identities have been recognized as a distal outcome for citizen science participants, one that requires thoughtful design to achieve (NASEM 2018). The sequence of IMP learning activities was intentionally designed to provide opportunities for students to work alongside expert scientists, and transition them from novice scientist to mini expert. The IMP was designed to engage students in science identity work with peers so that they might be recognized as the kind of person who can do science (Calabrese Barton et al. 2013). However, there was little evidence to suggest students identified as a scientist. Archer et al. (2010) found that many students are engaged in “doing” science, but do not appear to see themselves as “being” a scientist. They suggest that this may be due to perceptions that a science identity is inaccessible or undesirable. Science identities are intertwined with youth voice and agency, which is lacking in formal educational contexts (Rahm, Lachaîne, and Mathura 2014). School-mandated participation in citizen science may therefore not be recognized as an important site for identity development (Simms and Shanahan 2019). Although some research has shown that science identities are possible outcomes in curriculum-based citizen science (e.g., Chen and Cowie 2013), others were unable to show any impact (e.g., Williams, Hall, and O’Connell 2021). Science identities may be an unrealistic outcome for relatively short-term, school-based citizen science projects in which students are required to participate.

The Nature of Science

Gray, Nicosia, and Jordan (2012) proposed that citizen science projects integrated into school science should prioritize NOS as a learning outcome. However, few projects identify NOS as an outcome (Bonney et al. 2016; Phillips et al. 2018). Due to the weak evidence available to support NOS as a learning outcome, it has been referred to as a distal outcome that requires intentional design (NASEM 2018). The IMP was intentionally designed to engage elementary students in scientific practices and disciplinary ways of knowing. Although evidence of some student understanding of the NOS was visible (i.e., science as a collaborative process, society and science interaction, shared methods, creativity), it was not strongly represented. A critical review of the literature suggests that having students “do” science does not necessarily develop understandings of NOS. Explicit instruction is more effective (Abd-El-Khalick and Lederman 2000). The call for explicit instruction and intentional design to support understanding NOS has also been voiced in citizen science (Brossard, Lewenstein, and Bonney 2005; NASEM 2018).

Teachers play a crucial role in successfully integrating citizen science into their classrooms and schools (Roche et al. 2020). However, generalist elementary teachers often have little science experience and are underprepared to teach NOS (Olson et al. 2015; Shah and Martinez 2016). This study suggests that both students and teachers would benefit from more explicit instruction on the NOS in school-based citizen science. We argue that targeting NOS as a learning outcome in curriculum-based citizen science would create space for other ways of knowing science, such as Indigenous science (Snively and Williams 2016). This would align with calls from science education and citizen science to ensure other worldviews coexist alongside Western perspectives of science (BC MOE n.d.; Snively and Williams 2016; NASEM 2018).

Student-Teacher-Scientist Partnerships

This study indicates that providing opportunities for students, teachers, and scientists to learn together is an important design element of a curriculum-based citizen science project. Student-teacher-scientist partnerships (STSPs) are collaborations “in which students, teachers, and scientists work together to answer real-world questions about a phenomenon or problem the scientists are studying” (Houseal, Abd-El-Khalick and Destefano, 2014, p. 86). STSPs have been used as a framework for integrating citizen science with school science through intentional design (e.g., Bopardikar, Bernstein, and McKenney 2023; Zoellick, Nelson, and Shauffler 2012).They provide a mechanism to bridge communities of practice with different ways of knowing science (i.e., school science and the work of professional scientists). When carefully structured, STSPs can provide both valuable professional development for teachers and meaningful learning opportunities for students. Teachers are central to the STSPs as they act as both students—learning about scientific research, and teachers—transforming what they learn into new practices (Houseal, Abd-El-Khalick, and Destefano 2014). Bopardikar, Bernstein and McKenney (2023) offer a detailed example of how to intentionally design STSPs to overcome the boundaries that exist when integrating citizen science with school science.

Conclusion

The IMP is a local, curriculum-based citizen science project intentionally designed to support the development of science competencies in elementary students. A DBR approach was used to develop and refine the IMP activities between 2014 and 2023. This research was focused on a DBR Evaluation/Reflection phase that qualitatively assessed how participant learning outcomes were being met. Student- and teacher-generated data confirmed that students were developing science competencies. Recommended next steps are to measure for whom and under what conditions these science competencies are occurring. There was little evidence to suggest that the relatively short-term IMP could foster the development of science identities, and this outcome has since been removed from the framework. Understanding the NOS was a learning outcome that could benefit from explicit instruction. Additional supports for NOS continue to be developed. STSPs emerged as an important design element to achieve learning outcomes; however, providing STSPs for all participants remains and issue for the IMP.

Data Accessibility Statement

Some student and teacher-generated quotes are included in the article and supplemental files. Most data are not publicly available due to lack of parental consent/student assent.

Supplementary File

The supplemental file for this article can be found as follows:

Ethics and Consent

This research had ethical approval from the University of Calgary’s Conjoint Faculties Research Ethics Board and the Vancouver Island University Research Ethics Board. Permission to conduct research in the schools was received by the school district Superintendent and school principals. Each teacher that signed up for the IMP Research Days in 2016 was emailed an invitation to participate in the study. The first three teachers that submitted consent forms were included. A recruitment package for students was sent home with the Research Days paperwork. The consent/assent forms explicitly stated that participation was in no way connected to assessment and that participation was completely voluntary. Students could voluntarily opt-in to the research by returning a signed parental consent/student assent form. Parents or students could opt out of the study by not signing or not returning the forms.

Funding Information

This project had funding support from the Vancouver Island University Research Awards Committee.

Competing Interests

Four of the authors were either a voluntary Board Member (WS) or employed by the Nanaimo Science and Sustainability Society (LD, EM, EP) during the initial and ongoing development of the Intertidal Monitoring Project (IMP). There is no financial conflict of interest to report. The IMP was not created as an intervention for this research.

Author Contributions

LD initiated and developed the IMP with consultation from VIU scientists SD and JW. Ns3 Executive Directors (LD, EM, EP) managed and implemented IMP Research Days between 2014 and 2023. SD and EP oversaw the analysis of IMP data. WS developed supplementary classroom activities including the Research Proposal activity, conducted the research, and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript prior to submission.