artificial intelligence artificial neural networks consumer buying behavior consumption metaphor extreme learning machine k-nearest neighbors marketing intelligence machine learning neighborhood component analysis neighborhood component feature selection radio frequency identification single-layer feedforward neural networks support vector machine

The revolution in information technologies has led to the emergence of an interdisciplinary approach in the field of science (Klein, 2010; Rhoten et al., 2009). This approach aims to solve problems that cannot be addressed by a single method and emphasizes integration and effective problem-solving (Barry et al., 2008; Bergmann et al., 2005; Pohl & Hadorn, 2007). In marketing science, strategies such as customer behavior analysis, rapid data collection, and analysis have been developed (Barry et al., 2008; Bergmann et al., 2005; Pohl & Hadorn, 2007). Marketing professionals have started collaborating closely with information technologies for customer segmentation and data analysis (Florez-Lopez & Ramon-Jeronimo, 2009). This study examines consumer buying behavior (CBB) by applying machine learning (ML) and incorporates the role of the consumption metaphor (CM), comparing the results to validate the relationship between the two concepts.

ML has rapidly become widespread in the field of marketing alongside technological advancements. ML, adopted in digital advertising, provides successful examples on platforms like Facebook and Google (Purdy & Daugherty, 2016; Samuel, 1959). These platforms leverage ML’s ability to predict digital actions and reach the right customers with the best content. Syam and Sharma (2018) suggested that sales representatives use ML to analyze purchasing processes, thereby enhancing customer satisfaction. ML contributes to achieving more effective results in marketing strategies (Rakthin et al., 2016; Weber et al., 2018).

Tattooing serves as a powerful application area for understanding and analyzing consumer behavior. The decision to get a tattoo is closely tied to factors such as personal expression, independence, and the search for uniqueness. Tattoos are particularly popular among individuals aged 18–34, representing not only an aesthetic choice but also a social and cultural phenomenon. Research shows that 40% of individuals in this age group have at least one tattoo, with most getting their first tattoo before the age of 18 (Cvetkovska, 2021).

A personal choice like getting a tattoo provides an ideal data source for understanding the emotional, social, and psychological factors influencing consumer behavior. The frequency of getting tattoos, design choices, and service provider preferences reflect individuals’ consumption habits and priorities. Furthermore, this decision-making process is associated with broader dynamics such as identity formation and the pursuit of social acceptance. Tattooing offers a rich opportunity to analyze both individual and societal consumption trends and supports the prediction of these trends through ML techniques. Therefore, tattooing offers an effective application domain for both ML and CBB models (McGriff et al., 2015).

The study consists of two main stages. In the first stage, the effect of the CM on CBB was analyzed using traditional marketing techniques, and the results of this analysis were integrated into the implementation process to validate the ML predictions. This phase was conducted with 378 university students (n = 378) who have tattoos or are considering getting one, and printed surveys were distributed to students from Selcuk and Konya Technical Universities. The second main stage of the study involves ML applications. In this stage, the goals were to predict CBB and to both validate and estimate the effect of the CM on this behavior. The ML applications were divided into two sub-stages. In the first sub-stage, CBB was predicted, while in the second sub-stage, the effect of the CM on CBB was analyzed using ML techniques, and the results obtained from traditional marketing techniques were validated. The prediction process consisted of two steps: feature selection and model building. To identify significant predictors, the neighborhood component feature selection (NCFS) method was used. Among various ML approaches developed in recent years, three popular algorithms k-nearest neighbors (kNN), support vector machine (SVM), and Extreme Learning Machine (ELM) were selected for their suitability in predicting nonlinear human behavior.

This study holds significant value as it contributes to the limited body of literature that bridges marketing and ML approaches. In particular, the integration of multiple concepts within the application enhances its academic merit. Furthermore, its interdisciplinary nature offers innovative perspectives to various fields of science. One of the unique aspects of the study is its demonstration of how harmoniously and synchronously social sciences and engineering sciences can collaborate. This synergy is crucial in today’s rapidly evolving world, as it addresses scenarios where individual scientific domains may fall short. For future research, a conceptual proposal could be put forward to develop the notion of “algorith(m)arketing” through the joint efforts of engineering and marketing sciences (Ding et al., 2020; Hagen et al., 2020; Hair & Sarstedt, 2021; Haupt, 2020; Kaličanin et al., 2019; Mahajan et al., 2017).

The study continues with Section 2, where the literature review is made after the introduction. Section 2 presents a literature review on the relationship between CBB, CM, and ML. Section 3 is the methodology section which includes the purpose, importance, method, and design of the study. Section 4 is the section where empirical results are reported by analyzing the data. Section 5 focuses on the discussion, while Section 6 outlines the conclusion. The final section addresses the limitations of the study and provides recommendations for future research.

There are many studies associating tattoos and other body arts with CBB. Sanders (1985) examined the personalization of body parts as a component of consumer behavior. Watson (1998) and Horne et al. (2007) consider purchasing tattoos and other body arts as a form of ownership. Watson (1998) also suggested that the tattoo consumer makes at least two decisions regarding the choice of symbol and determining which part of the body to place it on. According to Kowalski (1999), young consumers are highly influenced by the effects of peer pressure when deciding to get a tattoo. Older consumers, on the other hand, are influenced by their children or friends when deciding on a tattoo (Hebden et al., 2011).

When consumers consider buying tattoos, they are influenced by their desire to enhance and support their self-concept in the eyes of others (Allison et al., 2000). Research has revealed that women are the group who buy the most tattoos and other body arts. Women think that a tattoo makes them more attractive (Harris Interactive, 2008). Burnkrant and Cousineau (1975) claimed that consumers buy tattoos in the belief that harmony can only be achieved when their behavior is seen by others. Park and Lessig (1977) also supported this view. According to Fishbein and Ajzen (2010), general attributes of a tattoo include price, future purchase intention, location on the body, and design. On the other hand, the global attitude toward tattoos also has an impact on the purchase of tattoos and other body arts. It seems that there are many other factors, especially demographic factors, that affect the consumer's decision when buying a tattoo.

It is important to discuss in detail the terminological differences and the interactions between these concepts in order to better understand the relationship between CBB and the CM. Accordingly, consumer behavior encompasses a broader scope compared to CBB. It includes processes such as purchasing, consuming, and disposing of products and services (Belch & Belch, 1998; Engel et al., 1995; Kotler et al., 2005; Solomon, 2007). CBB refers specifically to purchasing products or services for personal or household use (Pride & Ferrell, 2000). CBB can be influenced by various factors, including packaging, branding, and demographic characteristics. For instance, some studies have found that packaging and its components influence consumers’ buying decisions (Hsee et al., 2009). Branding is another factor that significantly affects CBB. Additionally, studies on brand image and advertisements have demonstrated a strong relationship with CBB (Malik et al., 2013; Raheem et al., 2014). The effect of demographic characteristics on CBB is also undeniable (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010; Harris Interactive, 2008; Hebden et al., 2011).

A metaphor is a figure of speech that explains something by analogy or by describing it in terms of something else (Lakoff, 2008). Various studies have explored the relationship between metaphor and CBB, known as the CM (Forceville, 1994; Leiss et al., 1990; McQuarrie & Mick, 1999; Stern, 1988). Zaltman and Coulter (1995) suggested that preferences, including the behavior of buying a pack of margarine, can be explained by metaphors they define as balance, transformation, journey, container, connection, control, and resource.

Just like events and facts, actions are given more meaning through metaphors. This is the main reason why metaphors are used in CBB (Lakoff, 2008). In consumer behavior research, analyzing data within the context of cultural metaphors offers a more accurate approach to minimize data loss (Moisander & Valtonen, 2006). Levy (1981) stated that consumers use metaphors in product usage and brand interpretation. Analyses based on metaphors are frequently applied in advertising and other marketing communication efforts. Through metaphors, the deep meanings formed by individuals’ experiences are revealed (Stern, 1995). Techniques like ZMET (Zaltman Metaphor Elicitation Technique) further facilitate uncovering consumers’ underlying thoughts (Coulter et al., 2001).

By analyzing the metaphors used by different consumer groups, valuable insights can be gained, providing various opportunities for market strategy (Hirschman, 2007). For example, a water company used religious connotations after some consumers indicated that bottled water represented religious purification. Ritzer (2003) explained modern shopping centers using the metaphor of “islands of the living dead,” highlighting how consumers spend significant time in such places. Holt (1995) discussed CMs across four dimensions: experience, integration, play, and classification. From this perspective, Chelminski and Ekin (2007) viewed CMs as tools rather than outcomes. In one study, consumers seeking tattoos chose metaphors such as gaining experience, joining a community, socialization, and social differentiation. The hypothesis H1 is formulated as follows:

H1: There is a significant relationship between CBB and the CM (p < 0.05).

Chaotic systems such as human behavior, weather conditions, and road traffic do not follow well-defined logical rules. The behavior of chaotic systems is highly sensitive to numerous parameters, making linear methods ineffective for predicting future states. Nonlinear ML methods have emerged as an alternative field of study, enabling researchers to uncover patterns that recur within disorder. In recent years, research on predicting human behavior across various domains using ML methods has gained momentum, especially due to its potential for commercial and political applications (Janssen et al., 2022; Van Noordt & Misuraca, 2022). This study provides an overview of research on CBB and its analysis through ML.

Chen et al. (2021) emphasize that tourism purchases can be accurately predicted using ML algorithms. Their study introduces a purchase forecasting model for online tourism and evaluates the impact of various behavioral variables on online tourism purchases. Shebl et al. (2021) analyze customer characteristics to examine the influence of economic and social factors on consumer behavior. Using data from the fast-food restaurant sector, they apply statistical methods and conclude that CBB is more strongly influenced by economic factors.

Chaudhuri et al. (2021) investigate CBB on an e-commerce platform to assist platform designers in planning user engagements. The study evaluates multiple ML algorithms and a deep learning method on a large multidimensional dataset. Alshehri et al. (2021) focus on predicting revenue for massive open online courses by analyzing students’ buying behavior. Their research compares the predictive accuracy of several ML algorithms in determining course purchasability.

Huiru et al. (2018) explore consumer behavior in wine consumption by applying two ML methods, providing valuable insights for wine production and marketing managers to make informed decisions. Zuo et al. (2016) propose a method for analyzing CBB by utilizing two representative ML methods to process RFID data collected from supermarkets. Chiu (2002) presents a case-based reasoning system enhanced by a genetic algorithm (GA-CBR) to predict CBB. Developed using real-world data from a global insurance company, the system incorporates an optimization mechanism to identify the most and least likely customers to purchase insurance.

Based on these reviewed studies, ML algorithms in this research are employed to predict CBB by utilizing variables collected from a tattoo survey as problem features. The study further validates the H1 hypothesis before applying ML methods to analyze the data.

The aim of this study is to predict CBB using ML techniques. The study consists of two scenarios. In the first scenario, the impact of the CM on CBB is integrated into the application phase to validate the ML predictions. In the second scenario, the ML model is designed not only to predict CBB but also to estimate and confirm the effect of the CM on CBB.

In other words, the second stage of the study is divided into two sub-phases: (1) predicting CBB and (2) evaluating and validating the relationship between CM and CBB. To achieve these objectives, the research focuses on individuals who either have tattoos or intend to get tattoos.

This part of the study was designed in the general survey model based on quantitative data and the relational survey model. Therefore, the study was conducted on 378 university students who have or intend to have a tattoo (n = 378), and printed surveys were applied to students from Selcuk and Konya Technical Universities. In the study, firstly, the effect of the CM on CBB was examined. Therefore, as a data collection technique, a survey was applied to 378 university students. The obtained data were analyzed with JAMOVI and SPSS 26.0 programs. The random sampling method was preferred in determining the students to be included in the sampling. Questions about the CM were adapted from Rammstedt and John (2007). A Likert scale (5) was used. The questions were replied to in the range of 1 = I strongly disagree, 5 = I strongly agree. Confirmatory factor analysis was performed to test the validity of the scales. Non-parametric analyses were performed on the data. In the analysis of the data, Cronbach’s Alpha reliability test and correlation analysis were performed. A cross-tab Chi-square analysis was conducted to determine the relationship between consumers’ CM and CBB. The significance level of the study was taken as (p < 0.05). The results showed that the CM is effective on CBB. In this context, the research hypothesis and research model are designed as follows. Thus, it will be evaluated whether the results obtained in the study are statistically significant, and whether the hypothesis is confirmed or not will be tested.

H1: There is a significant relationship between CBB and CM as shown in Figure 1 (p < 0.05) (Coulter et al., 2001; Hirschman, 2007; Lakoff, 2008; Stern, 1995).

Relationship between CM and CBB.

The second scenario of the research consists of an ML application. The ML application is also divided into two sub-stages. In the first stage of the ML application, the estimation of CBB was carried out. In the second stage, the effect of the CM on CBB was estimated using the ML technique. The result obtained through the statistical analysis of marketing techniques was confirmed in this process. The estimation process was carried out in two steps: feature selection and model creation. NCFS was used in the first step to identify important predictors. Afterward, three popular learning algorithms kNN, SVM, and ELM were used to predict nonlinear human behavior.

Feature selection is the process of investigating the effectiveness of features in data mining. Determining the subset involving the most significant features assists decrease overfitting, reduce training time, and improve accuracy of a learning model (Ayyıldız & Tuncer, 2020). More comprehensive reviews on feature selection methodologies can be referred to (Guyon and Elisseeff, 2003; Guyon et al., 2008; Saeys et al., 2007). In this study, the NCA which is a feature weighting approach was employed as a feature selection (Goldberger et al., 2004). NCFS attempts to state the weights of features by optimizing an average leave-one-out classification accuracy objective function.

The primary goal is to identify a weighting vector w on the labeled training set T = {(x

i

, y

i

), i = 1, 2, …, N} where

If

NCA feature selection.

| 1 | Procedure |

| 2 | Initialization: |

| 3 | repeat |

| 4 | for I = 1, …, N do |

| 5 | Compute |

| 6 | for l = 1, …, d do |

| 7 |

|

| 8 |

|

| 9 |

|

| 10 |

|

| 11 | if |

| 12 |

|

| 13 | else |

| 14 |

|

| 15 | until |

| 16 |

|

| 17 | return |

The kNN algorithm is an instance-based classification algorithm proposed by Fix and Hodges (1951). The method is based on predicting the class of the new sample by investigating the distance of the features of the new instance to the features of known instances in the training set as follows.

The algorithm steps of kNN.

| 1 | Determine the value of |

| 2 | Calculate the distance between the new instance |

| 3 | Determine the |

| 4 | Determine the class of the new instance by majority voting. |

SVM algorithm is based on the idea of finding a decision boundary called hyperplane that classifies the data points in high-dimensional space (Vapnik, 2013). The objective of the algorithm is to determine a plane that has the maximum margin among many possible hyperplanes. Any hyperplane can be written as equation (5).

As it is known, in real-world problems, data are often noisy and linearly inseparable. Defining hing loss function is shown in 7. SVM was able to solve such problems as well. Thus, the optimization problem takes the following form:

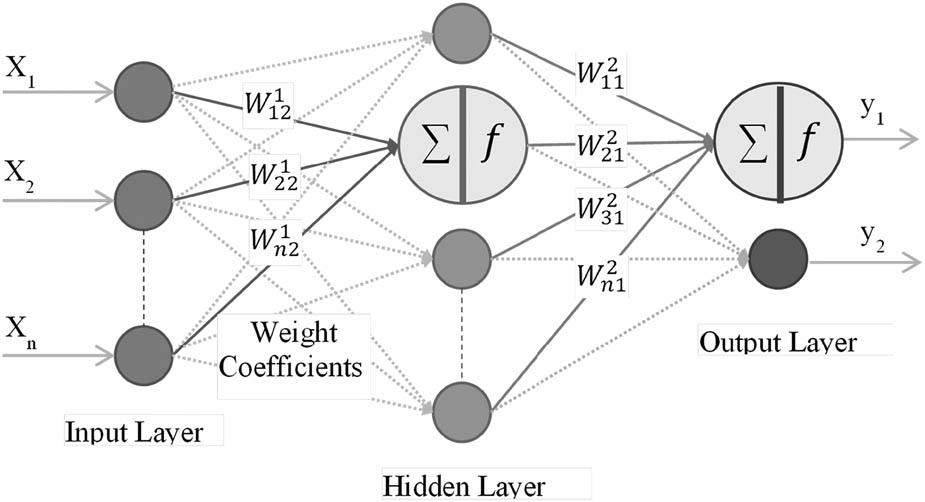

ELM proposed by Huang et al. (2006) are random weight networks in the type of single-layer feedforward neural networks (SLFN). ELM uses the Moore-Penrose generalized inverse to adjust neural weights instead of gradient-based backpropagation. Due to the weights stated analytically, the method tends to provide good generalization performance at an extremely fast learning speed. SLFNs with random hidden nodes are mathematically modeled as equation (8).

As a result, the neural network model is illustrated in Figure 2, and the algorithm is summarized in Table 3.

Neural network model.

The algorithm steps of ELMs.

| 1 | Assign weights |

| 2 | Calculate hidden layer output, H |

| 3 | Calculate output weight matrix , |

| 4 | Use |

This is the part in which the CBB and the CM are associated. First, the frequency distribution table according to the demographic characteristics of the participants is given in Tables 4 and 5.

Sample distribution table of the subjects participating in the study.

| Variables | Frequency (f) | Percent (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 180 | 47.6 |

| Male | 198 | 52.4 | |

| Age | 17–18 | 16 | 4.2 |

| 19–20 | 177 | 46.8 | |

| 21–22 | 137 | 36.2 | |

| 23–24 | 33 | 8.7 | |

| 25 and more | 15 | 4.0 | |

| Body type | Slim | 92 | 24.3 |

| Normal | 237 | 62.7 | |

| Large | 49 | 13.0 | |

| Educational level | Associate degree | 299 | 79.1 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 79 | 20.9 | |

| Science field | Social sciences | 324 | 85.7 |

| Science | 36 | 9.5 | |

| Health Sciences | 18 | 4.8 | |

| Level of income | 1,000 TL and less | 224 | 59.3 |

| 2,000 TL | 85 | 22.5 | |

| 3,000 TL | 24 | 6.3 | |

| 4,000 TL | 11 | 2.9 | |

| 5,000 TL and more | 34 | 9.0 | |

| Total | 378 | 100 | |

Distribution table of socio-demographic characteristics of the subjects participating in the study.

| Variables | Frequency (f) | Percent (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship (partner) | Yes | 132 | 34.9 |

| No | 246 | 65.1 | |

| Place of birth | Big city | 171 | 45.2 |

| Province | 99 | 26.2 | |

| County | 99 | 26.2 | |

| Village | 9 | 2.4 | |

| Living place | Big city | 243 | 64.3 |

| Province | 79 | 20.9 | |

| County | 46 | 12.2 | |

| Village | 10 | 2.6 | |

| Mother’s education level | Illiterate | 23 | 6.1 |

| Primary school | 156 | 41.3 | |

| Secondary education | 156 | 41.3 | |

| University | 43 | 11.4 | |

| Father’s education level | Illiterate | 8 | 2.1 |

| Primary school | 137 | 36.2 | |

| Secondary education | 162 | 42.9 | |

| University | 71 | 18.8 | |

| State of illness | Yes | 48 | 12.7 |

| No | 330 | 87.3 | |

| Total | 378 | 100 | |

When Table 4, regarding the characteristics of the sample, is examined, 47.6% of the participants are female, and 52.4% are male. The 19–20 age group constitutes 46.8% of the age distribution. Additionally, 62.7% of body types are classified as normal. Furthermore, 79.1% of the education levels consist of an associate's degree. The field of science for the participants is predominantly social sciences, with a rate of 85.7%. In terms of income, 59.3% of participants earn 1,000 TL or less.

When Table 5, regarding the socio-demographic characteristics of the sample, is examined, 65.1% of the participants reported not being in a relationship. Places of birth are predominantly provinces and districts, accounting for 52.4%, while living places are primarily big cities, with a rate of 64.3%. The mother’s education level is primary and secondary education for 82.6% of participants, and the father’s education level is primary and secondary education for 79.1%. Additionally, “no response” constitutes 87.3% of the state of illness responses.

The CM survey questions were adapted from Rammstedt and John (2007). The CM scale consists of four questions and is designed in a five-point Likert scale format, ranging from 1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree.

The CBB scale consists of 11 questions. The internal consistency coefficient of the CBB scale was calculated as α = 0.845, while the CM scale was calculated as α = 0.961. If these values are above 0.70, it indicates that the reliability of the scale is high. To analyze the data, Cronbach’s Alpha test, descriptive statistics, and correlation analysis were used. The significance level of the study was set at p < 0.05. The findings were interpreted by transforming them into tables aligned with the research questions.

According to the Cronbach Alpha values in Table 6, both scales are above 0.70. Accordingly, it is understood that the scales used for CM and CBB are reliable.

Cronbach’s alpha test.

| Scale | Number of expression | Cronbach alpha |

|---|---|---|

| CM | 4 | 0.823 |

| CBB | 11 | 0.792 |

The KMO value should be above 0.50 (Bartlett, 1950). Table 7 indicates that the KMO test clearly meets this requirement, with a value of 0.835.

Kmo–Bartlett’s test.

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy | 0.835 | |

| Bartlett’s test of sphericity | Approx. chi-square | 5174.812 |

| df | 435 | |

| Sig. | 0.000 | |

Items with factor loadings below 0.30 and a difference of no greater than 0.100 between loadings in different factors (i.e., any item loading on more than one factor with a difference of less than 0.1) were excluded from the analysis (SD4, SD6, SD8, SD9). The remaining items were analyzed using principal components analysis and the Varimax orthogonal rotation technique. The total variance explained was found to be 58.812%.

According to Table 8, the structures of the scales tested through the exploratory factor analysis and internal consistency findings were confirmed.

Exploratory factor analysis.

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| CM Cr. Alpha = 0.823 | Get experience with tattooing | 0.618 | |

| Desire to join a community | 0.847 | ||

| Socialization or group interaction | 0.902 | ||

| Social differentiation | 0.846 | ||

| CBB Cr. alpha = 0.792 | Do you have a tattoo? | 0.441 | |

| Would you like to get a tattoo? | 0.701 | ||

| What are the reasons why you don’t want to get a tattoo? | 0.650 | ||

| Do you want to get a permanent tattoo or a temporary tattoo? | 0.897 | ||

| On which part(s) of your body did you have your tattoo done or would you like to have it done? | 0.599 | ||

| Does anyone in your family have a tattoo? | 0.850 | ||

| Do any of your friends have tattoos? | 0.875 |

Confirmatory factor analysis was performed to test the validity of the scales used in the study. As can be seen in Tables 4 and 5, the structures of the scales tested according to confirmatory factor analysis and internal consistency findings were confirmed.

When the model fit criteria, goodness of fit index reference ranges in Table 9, model results, and Table 10 are examined, the goodness of fit for the CM and CBB scales is high. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to assess the distribution of the data. According to the test results, the CM measurement data (test statistic: 0.112, p = 0.00) and the CBB measurement data (test statistic: 0.102, p = 0.00) are not normally distributed, as indicated by the rejection of the null hypothesis.

Goodness of fit indexes of scales.

| Scale model | ΔX 2 | sd | p | ΔX 2/sd | GFI | CFI | RMSEA | RMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CM | 7.274 | 6 | 0.06 | 1.21 | 0.85 | 0.97 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| CBB | 5.489 | 3 | .23 | 1.83 | 0.89 | 0.95 | 0.04 | 0.02 |

Notes: (i) The relationship is significant at the p < 0.01 significance level (ii) ΔX 2 (chi-square test result of cm, sd (degrees of freedom), p (significance value), ΔX 2/sd (chi-square value of cm divided by degrees of freedom), GFI (absolute fit index), CFI and RMSEA (comparative fit index) , RMR (residual based fit index).

Model fit criteria goodness of fit index reference ranges.

| Model fit criteria | Good fit | Acceptable fit |

|---|---|---|

| X 2 Uyum Testi | 0.05 < p ≤ 1 | 0.01 < p ≤ 0.05 |

| CMIN/SD | X 2/sd ≤ 3 | X 2/sd ≤ 5 |

| Comparative fit indexes | ||

| CFI | 0.97 ≤ CFI | 0.95 ≤ CFI |

| RMSEA | RMSEA ≤ 0.05 | RMSEA ≤ 0.08 |

| Absolute fit indexes | ||

| GFI | 0.90 ≤ GFI | 0.85 ≤ GFI |

| Residual compliance indexes | ||

| RMR | 0 < RMR ≤ 0.05 | 0 < RMR ≤ 0.08 |

To avoid Type I and Type II errors, non-parametric analyses were conducted. The data were analyzed using the Cronbach’s Alpha reliability test and descriptive statistics, while correlation analysis was used to compare the two variables. A cross-tabulation Chi-Square analysis was also conducted to examine the relationship between CM and CBB. The significance level for the study was set at p < 0.05. The findings obtained from the analyses were interpreted and presented in tables aligned with the survey questions.

According to the results of the simple correlation analysis of the relationship between CM and CBB measurement data in Table 11, a positive, moderate, and significant correlation is observed (r = +0.315, p < 0.01).

Correlation analysis results.

| Measurement data | 1 | 2 |

| 1. CM | 1 | |

| 2. CBB | 0.315** | 1 |

Notes: (i) **At p < 0.01 significance level, the relationship is significant (Spearman rho).

After identifying this significant relationship, a chi-square test was performed to analyze the association between CBB categories and the CM. The analysis results are presented in Table 12. When the results of the Chi-Square analysis test among the categories of CBB are examined in Table 12, it is observed that 96.4% of the participants expressed a desire to get a new tattoo, while 3.6% stated that they did not plan to have one. Additionally, 46.0% of those who wanted a tattoo responded, “I did not have it” when asked if they would like to have a tattoo. Furthermore, 70.7% of the study participants answered, “I did not have it” to the question, “Would you like to have a tattoo?”

Chi-Square analysis results among CBB categories.

| Would you like to get a tattoo? | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Total | |||

| Did you get a tattoo? | Yes, I did | Frequency | 213 | 8 | 221 |

| Did you get a tattoo? | 96.4% | 3.6% | 100.0% | ||

| Would you like to get a tattoo? | 29.3% | 1.3% | 16.5% | ||

| No, I did not | Frequency | 514 | 604 | 1,118 | |

| Did you get a tattoo? | 46.0% | 54.0% | 100.0% | ||

| Would you like to get a tattoo? | 70.7% | 98.7% | 83.5% | ||

| Total | Frequency | 727 | 612 | 1,339 | |

| Did you get a tattoo? | 54.3% | 45.7% | 100.0% | ||

| Would you like to get a tattoo? | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | ||

Notes: (i) Pearson Chi-Square X 2 = 188.920, p = 0.000 (ii) At p < 0.01 significance, the relationship is significant.

Overall, 54.3% of the participants indicated, “I would like” to have a tattoo, while 45.7% stated, “I would not.” The Chi-Square analysis results for these findings were statistically significant (X 2 = 188.920, p = 0.000). Moreover, the two-way significance value (p) was less than 0.05 within the 95% confidence interval. Consequently, the H1 hypothesis was accepted (H1: There is a significant relationship between CBB and CM, p < 0.05).

In addition to sociodemographic data, the questionnaire includes four groups of questions and 50 sub-questions covering personality, physical characteristics, CM, and buying events. The questions related to CBB determine the class label of the dataset, while the other sub-questions constitute the variables used for prediction. The dataset consists of 378 samples, 48 attributes, and two class labels. As shown in the Chi-Square analysis, the distribution of class labels is balanced. The Likert-type data were standardized for processing and analysis, with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1.

Two different approaches are considered for prediction. The first approach uses all survey questions as features, incorporating feature selection to optimize the predictive model. The second approach investigates whether CBB can be predicted solely based on the CM, addressing one of the key research questions of the study.

The importance of features in prediction or classification performance is not equal, and some variables may negatively impact performance. Although this study does not utilize a very large dataset, identifying variables that positively affect performance while discarding those below a determined threshold offers several advantages. These include improving classification accuracy, reducing computational cost, and minimizing time consumption.

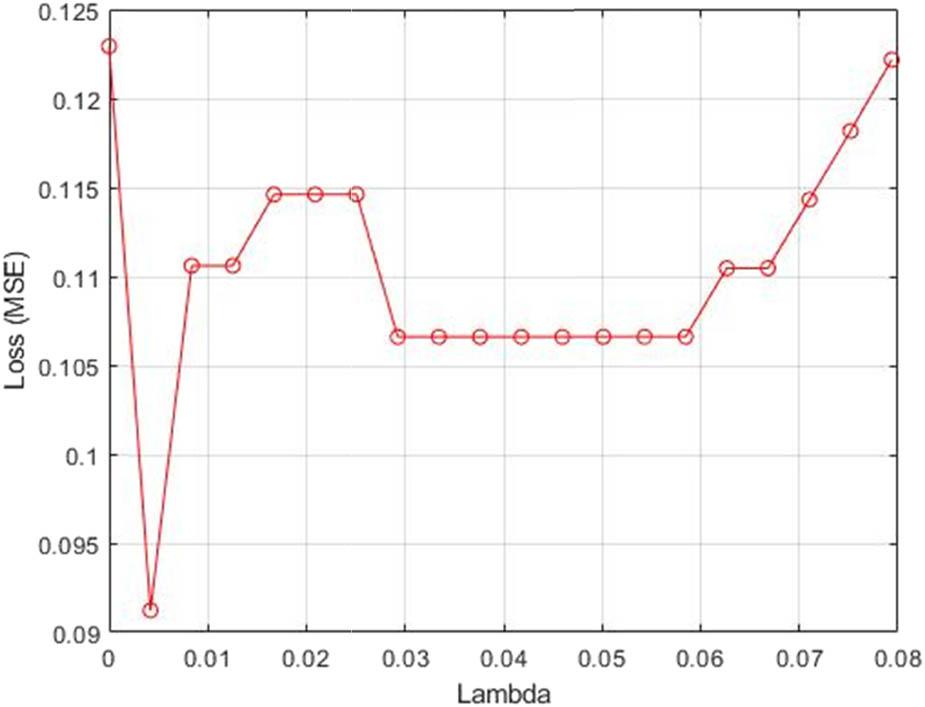

To achieve this, the NCFS approach was applied. The dataset was initially split into 10 folds. For each fold, four-tenths of the data were designated as the training set, while one-tenth was assigned as the test set. After determining a range of λ values, the NCA model was trained for each λ value using the training set in each fold. The NCA model then computed the classification loss for the test set in each fold. Subsequently, the average loss across the folds was calculated for each λ value. The λ value corresponding to the minimum average loss was identified as the optimal value. Figure 3 illustrates the average loss values plotted against the λ values.

Loss values versus the λ values.

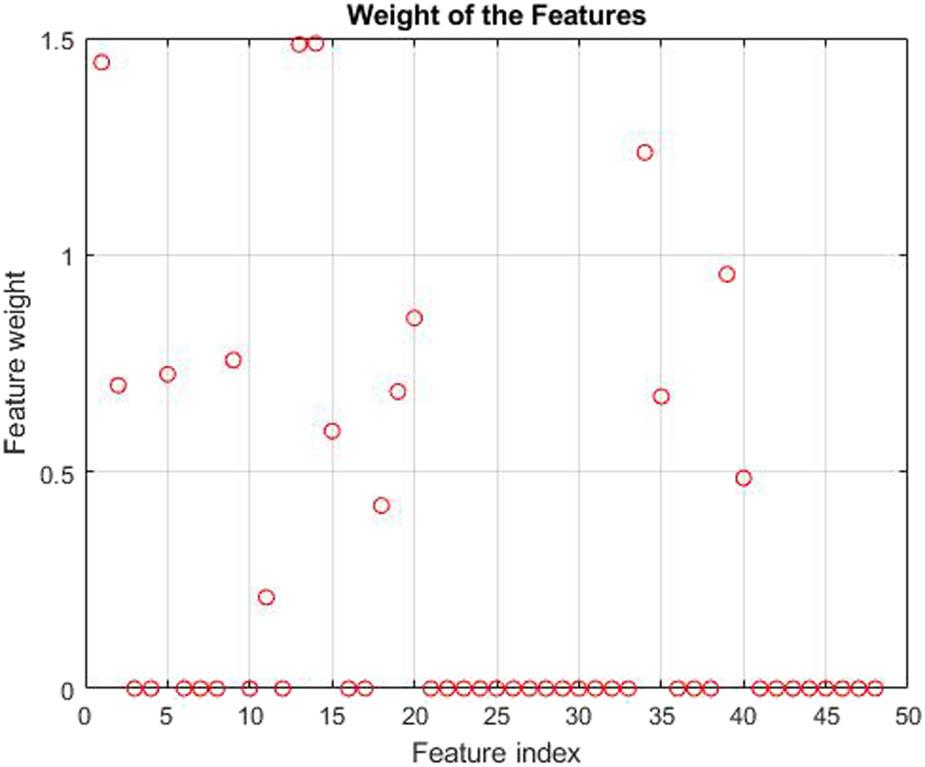

Once determined the best λ, the NCA scheme is fitted to the dataset. Features are selected according to the feature weights and threshold value = 0.01. Figure 4 shows feature weights values versus the feature index.

Weight of the features.

Due to the nonlinear nature of the CBB problem, we employed nonlinear ML algorithms, including kNN, SVM, and ELM as prediction models. To address overfitting and ensure robustness in the learning algorithms, we utilized the k-fold cross-validation method with k = 10.

During each iteration of cross-validation, the data were partitioned into training and testing sets. All algorithms, along with their variations using different parameter configurations, were run consecutively to enable a fair comparison. This ensured that the learning algorithms were trained on the same training data and evaluated on the same test data. The average performance indicators obtained across different parameter settings and folds are presented in Tables 13 and 14.

Prediction with all features.

| Method* | Accuracy | Specificity | Precision | Recall | F-Measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KNN | 89.77 | 87.33 | 89.26 | 91.64 | 90.27 |

| SVM | 87.54 | 85.46 | 87.49 | 88.72 | 87.84 |

| ELM | 87.32 | 81.48 | 85.49 | 91.60 | 88.23 |

Notes: (1)* Parameters of Learning Algorithms: KNN with k = 1, 3, 5, 7. SVM with Kernel RBF and Polynomial, Order = 2, 3, 4, 5. ELM: Activation Function is Sigmoid, Number of Hidden Neurons 10, 20, 30, 40, 50.

Prediction with selected features by using NCFS.

| Method* | Accuracy | Specificity | Precision | Recall | F-Measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KNN | 91.02 | 90.98 | 91.91 | 90.51 | 91.03 |

| SVM | 87.63 | 87.14 | 88.46 | 86.91 | 87.47 |

| ELM | 88.54 | 84.98 | 87.29 | 91.34 | 89.13 |

Notes: (1)* Parameters of Learning Algorithms: KNN with k = 1, 3, 5, 7. SVM with Kernel RBF and Polynomial, order = 2, 3, 4, 5. ELM: Activation Function is Sigmoid, Number of Hidden Neurons 10, 20, 30, 40, 50.

The nonlinear learning algorithms applied to the CBB problem demonstrated similar performance and achieved high success rates. According to the results tables, the satisfying F-Measure values can be attributed to the balanced distribution of class labels and the strong relationship between Precision and Recall indicators. This balance ensures that accuracy can be safely used to compare the algorithms. Based on the accuracy results in Table All, SVM outperformed the other two algorithms. For instance, when using all attributes, kNN correctly predicted 89.77% of consumers who tend to have tattoos and 87.33% of consumers who do not.

To further explore the problem, we expanded the experimental study with a feature selection approach. While discarding some attributes may result in minor performance degradation, it also offers benefits such as reduced computational cost and time. In this study, however, reducing the number of features led to an average improvement of 1% in the accuracy of the learning algorithms compared to the full-feature scenario. Since the primary goal of our research is to predict consumers who tend to buy, we prioritized accuracy over specificity.

The results demonstrate that the NCFS algorithm effectively selects attributes that have a dominant influence on class labels. As shown in Table NCFS, the kNN algorithm predicted 91.02% of consumers who tend to have tattoos and 90.98% of those who do not. SVM and ELM followed closely, with only slight differences in performance. Therefore, we conclude that nonlinear learning algorithms are well-suited for predicting CBB.

The final step of the prediction section examines the relationship between CBB and the CM. The survey includes four metaphor-related questions designed to explore the purpose of consumption. For this analysis, the dataset was reduced to four attributes, retaining the two class labels. The classifiers were applied under the same conditions as in the previous experimental study, and the results are presented in Table 15.

Prediction with metaphor variables by using NCFS.

| Method | Accuracy | Specificity | Precision | Recall | F-Measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KNN | 72.86 | 83.56 | 79.78 | 62.88 | 69.25 |

| SVM | 70.06 | 69.75 | 70.00 | 70.92 | 69.60 |

| ELM | 78.33 | 79.51 | 79.34 | 77.55 | 78.12 |

The prediction results reveal how consumers’ perspectives on the CM influence their consumption preferences. However, these results also underscore the impact of other consumption-related factors, the absence of which explains the decrease in predictive success compared to the previous experiment. Focusing on the ELM model, the metaphor-based prediction achieved an accuracy of 78.33% for customers who tend to buy and 79.51% for those who do not. The other two algorithms yielded accuracy rates of 72.86 and 70.06%, respectively.

The integration of marketing and ML approaches has the potential to significantly minimize errors in predicting consumer needs, as highlighted by studies such as Kaličanin et al. (2019) and Hagen et al. (2020). In terms of managerial implications, this integration can lead to improvements in critical performance criteria such as efficiency, profitability, economy and productivity. Over the past two decades, the relationship between information technologies and marketing sciences has gained increasing attention, suggesting that future research could introduce “algorith(m)arketing” as a new concept. This concept would represent the intersection of marketing and information technologies, providing a fresh lens through which to explore marketing practices (Kotras, 2020). Studies aligning with this theme could be categorized under this emerging framework in the literature (Ding et al., 2020; Hair & Sarstedt, 2021; Haupt, 2020; Mahajan et al., 2017).

Methodological approaches, such as case studies and empirical research, have been proposed to explore AI applications in organizations. However, the sufficiency of these approaches remains debatable. While case studies provide detailed insights within specific contexts, they lack generalizability. Conversely, empirical studies are broader in scope but often fail to capture the complexities of organizational realities. Given the limited availability of AI technologies when Duchessi (1993) proposed these methodologies, it is necessary to reassess whether they can adequately address the complexities of modern AI applications.

Although AI techniques are promoted as tools to streamline and manage workflows, their effectiveness may vary significantly across organizations. For instance, while the Clowder model emphasizes personalized workflows, it overlooks potential drawbacks such as limiting employee autonomy and negatively impacting organizational culture. Furthermore, the notion of dynamically controlling workflows through ML techniques could complicate decision-making processes by reducing human involvement, rather than enhancing transparency.

Dai and Weld’s (2010) assertion that optimized workflows outperform human-produced outputs depends on the performance criteria used for evaluation. While the centrality of social media awareness in AI-based marketing intelligence (MI) is acknowledged, it raises concerns about user privacy and ethical implications.

In summary, while AI offers significant potential benefits for organizational applications, it is essential to address its limitations and potential negative impacts with greater scrutiny.

This study aimed to determine the significant relationship between CBB and CM. It was conducted on n = 378 participants to reduce sampling error by attempting to reach the maximum sample size. A single hypothesis was formulated to assess the relationship between CM and CBB. The findings revealed a significant relationship between these two variables. Specifically, the analysis demonstrated a connection between consumers’ tattooing behaviors and their general buying tendencies.

The results showed that most individuals with tattoos expressed a desire to get a new tattoo, suggesting that tattoos serve as a form of personal identity expression or even as a habit. Conversely, the absence of this desire in a small percentage of tattooed individuals indicates that tattooing is a personal preference that may reach a natural endpoint for some.

Data on consumers considering getting a tattoo revealed that a significant portion of those expressing this desire had not yet done so. This finding suggests that external factors such as financial constraints, cultural norms, social influences, or personal concerns may play a role in delaying the decision. Furthermore, the significant number of individuals who do not want a tattoo underscores the influence of cultural, religious, or personal reasons in distancing some from such decisions. Overall, these findings emphasize the role of CMs in tattooing decisions, with tattoos acting as both an aesthetic choice and a vehicle for individual identity and self-expression.

A deeper investigation into individuals considering a tattoo but not taking action could offer additional insights into the factors shaping this process. In light of these findings, the hypothesis H1: There is a significant relationship between CBB and CM (Coulter et al., 2001; Hirschman, 2007; Lakoff, 2008; Stern, 1995) was accepted.

Among the nonlinear ML methods applied, kNN identified 89.77% of participants who were willing to get a tattoo. In prediction and classification problems, the importance of features varies, with some features potentially having less or even negative impacts on performance. Feature selection methods identified such features, and their removal improved prediction accuracy by approximately 1% while also reducing dataset size, computational cost, and time consumption. Using the selected features, kNN correctly classified 91.02% of consumers willing to get a tattoo. The other algorithms tested SVM and ELM also performed well, achieving favorable prediction results.

Regarding the CM, the significant relationship between CBB and metaphor was further validated through the classification performance of the algorithms. For example, ELM achieved a classification accuracy of 78.33% when using metaphor-related queries. These results are consistent with findings in other studies (Chaudhuri et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2021; Huiru et al., 2018; Zuo et al., 2016). Specifically, Alshehri et al. (2021) conducted a study on students and reported similar outcomes. Chiu (2002) also explored consumer buying probabilities using ML, showing parallels with the results of this study.

However, some distinctions exist. Zuo et al. (2016) processed Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) data using ML, whereas this study relied on survey data. Additionally, Chiu (2002) employed a genetic algorithm combined with an optimization mechanism to predict buying probabilities, further differentiating his approach from this study. Despite these differences, the overall alignment of findings underscores the robustness of the methodologies and the relevance of the CM in CBB research.

This study focused on a specific group of university students, which inherently limits the generalizability of the results to a broader population. Additionally, logistical and economic challenges associated with data collection prevented the use of larger, more diverse samples. As a result, the study was intentionally conducted on a homogeneous and relatively small group to establish a foundation for future research. To address generalizability, we utilized algorithms that are current in the literature and known for their high generalization capabilities.

Future studies could build on this work by testing the generalizability of the results using larger samples with diverse socio-demographic characteristics. Expanding the dataset in this manner would enhance the robustness and applicability of the findings.

A review of the ML literature reveals the vast range of available algorithms, including those designed for clustering and prediction tasks. Examples include artificial neural networks (ANN), logistic regression, and decision trees (Mohri et al., 2012). The absence of additional learning algorithms in this study represents one of its limitations (Canepa, 2016). Future research could explore the use of a wider variety of ML techniques to compare their effectiveness.

Further, incorporating additional questions related to the CM scenarios could improve the accuracy of predictions in ML applications. Given that predicting CBB is a chaotic and non-linear problem, future studies could also focus on developing new deep learning models to uncover higher-level patterns in the CBB of individuals who express interest in tattooing.

This study was supported by the Artificial Intelligence Application and Research Centre of Konya Technical University.

Authors state no funding involved.

Alaaddin Selcuk Koyluoglu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Collecting, Data Analysis (Statistical Modeling), Writing, Visualization.Engin Esme: Software (ML implementation), Validation, Data Collecting, Formal Analysis (Machine Learning), Writing, Algorithm Design.

Authors state no conflict of interest.