This paper presents a case study, where a framework for passive (i.e. no active signal) target detection is described. Furthermore, two configurations for an algorithm of the detection framework are detailed, implemented and evaluated. The implementation was motivated by the need to utilise a commercially available passive 360-degree camera sensor for target detection and classification tasks in a military application on an unmanned ground vehicle (UGV). This simplified use case would involve two target classes. Therefore a video dataset was gathered to train and test machine learning (ML) models. The dataset included two tracked vehicle types in a relevant operational environment. The models were evaluated in two settings: offline, using pre-recorded data, and online, as part of a demonstration test on the Laykka UGV platform (Hemminki et al. 2022). The online evaluation involved final field testing with real-life combat vehicles in Finnish winter woodlands. During this testing phase, the models were responsible for enabling the UGV’s autonomous control to closeup the distance to a tracked vehicle.

Autonomous systems have found their way into various military applications, including unmanned military vehicles and flying drones (Munir et al. 2022). These systems are able to provide numerous advantages, such as increased combat efficiency and reduced operational risks for personnel by removing them from frontlines and lines of fire (Scharre 2015). In such systems, achieving a comprehensive 360-degree situational awareness within complex and dynamic environments remains a pervasive challenge. To achieve this, researchers have often focused on employing sensor fusion techniques to enhance situational awareness by capturing a complete view of the surroundings (Schueler et al. 2012; Yeong et al. 2021). Active sensors emit energy in the form of signals and analyse the reflected responses to detect objects or gather information, while passive sensors rely solely on detecting natural energy, such as light or heat, emitted or reflected by objects in the environment. While many sensor fusion techniques and systems are accurate and efficient, they are detectable by other sensors. Additionally, using sensor fusion introduces a probability of malfunctions and poses challenges in costs, synchronisation and data integration (Yeong et al. 2021).

To avoid possible exposure by laser and various signal-detecting systems commonly used in military combat vehicles (Heikkila et al. 2004; Graswald et al. 2019), autonomous navigation of a UGV towards the target should rely exclusively on visual or audio-based sensor fusion techniques, without emitting any signals, thus being a passive system. A presence of even one active sensor system makes the whole system active. By controlling and minimising possible sensor emissions, UGV will be harder to detect for military vehicles and their detection systems, as they mostly rely on active sensor signals and their emissions (Heikkila et al. 2004; Graswald et al. 2019). Thus the UGV would require advanced passive capabilities for the determination of distance to the target. These capabilities could be based on passive sensor data, stereo vision or a 360-degree camera for accurate target recognition and locking (Andersson et al. 2024).

To overcome the challenges above, this paper presents a passive 360-degree camera-based framework for target detection. In the framework, a single cost-effective and seamlessly integrated 360-degree camera passive sensor is utilised to provide a more simplified passive solution for executing military recognition tasks. This approach not only addresses implementation challenges but also streamlines data integration, ensuring a simpler and reliable passive system for military daylight operations. Because of the need to process sensor data locally, there are limitations to the computation power available for the ML-related tasks. The computational limits are compounded even further if the system is designed to be expendable as well as the target detection time window is restricted. Furthermore, ML recognition models are restricted in terms of the architecture, including the image size that can be inputted. These limitations are aggravated by the fact that the panoramic image contains information from an omnidirectional view while a typical camera focuses on a smaller view section. Concretely, the panoramic image has to be compressed leading to information loss.

This study follows an inductive, exploratory research approach, with the purpose of demonstrating the feasibility and evaluating a detection framework for passive sensor integration in military UGV. Specifically, it investigates how a passive 360-degree vision system can support autonomous target detection in real-world outdoor conditions. The Laykka UGV platform is used as a test case to implement and evaluate the proposed framework. The framework supports two alternative detection configurations: the Panorama Model, which processes the entire panoramic image, and the Windowed Model, which segments the panorama into resolution-preserving image crops. These configurations are integrated into the Laykka AI module and evaluated through both offline experiments and real-world field tests. The Laykka platform serves as a representative example of a resource-constrained, passive, low-cost and expendable military UGV.

This study seeks to answer the following research question: (1) Does the proposed framework perform as expected in the test case; specifically, can a single passive 360-degree camera, integrated with ML, enable reliable target detection and classification for military UGV applications in real-world outdoor conditions? To support this inquiry, the study also examines two sub-questions: (a) Which configuration of the framework and ML algorithm provides better offline accuracy for target classification and detection? and (b) Can any of the ML algorithms deliver feasible online performance given the computational constraints of the UGV system and the temporal demands of a live test?

In the proposed framework, the initial step involves the transformation of a 360-degree fisheye camera image into a panoramic representation. In contrast to many existing methodologies that directly input either the 360-degree image or its panoramic counterpart into an ML algorithm, the approach presented in this paper includes an intermediate step that serves as a bridge between 360-degree image data and post-processing algorithms. Specifically, the panoramic image is partitioned into multiple sub-regions matching the input resolution of existing object detection algorithms without any loss in image quality and especially in resolution available to the model. This streamlines the image processing pipeline, enhancing the efficiency of object identification but also directly supports parallel processing if required.

This work is grounded in a pragmatic epistemological stance, where the utility of a detection framework is demonstrated through real-world performance rather than theoretical modelling. The ontology is constructive-technical, viewing the UGV as a designed artefact whose behaviour can be empirically evaluated in realistic environments.

Section 2 reviews existing sensor systems in autonomous navigation and describes the Laykka UGV platform. Section 3 details the proposed detection framework, including the fisheye-to-panorama transformation and its integration into the Laykka AI module. Section 4 presents experimental results comparing the two model configurations in both offline and real-world tests. Section 5 discusses system performance, outlines current limitations, and suggests future research directions. Finally, the Conclusion summarises the findings and highlights broader applications of the framework beyond military use.

This section elaborates on the UGV platform used and related work in the context of object detection. First, an overview of the UGV’s role and its growing significance in military applications is presented. Next, the key sensors used for autonomous navigation and object detection in these platforms are examined, with a focus on the challenges posed by sensor fusion. Finally, related works on object detection within UGVs and other autonomous vehicles are reviewed, highlighting the methodologies and technologies employed, particularly the use of 360-degree cameras for situational awareness and target identification.

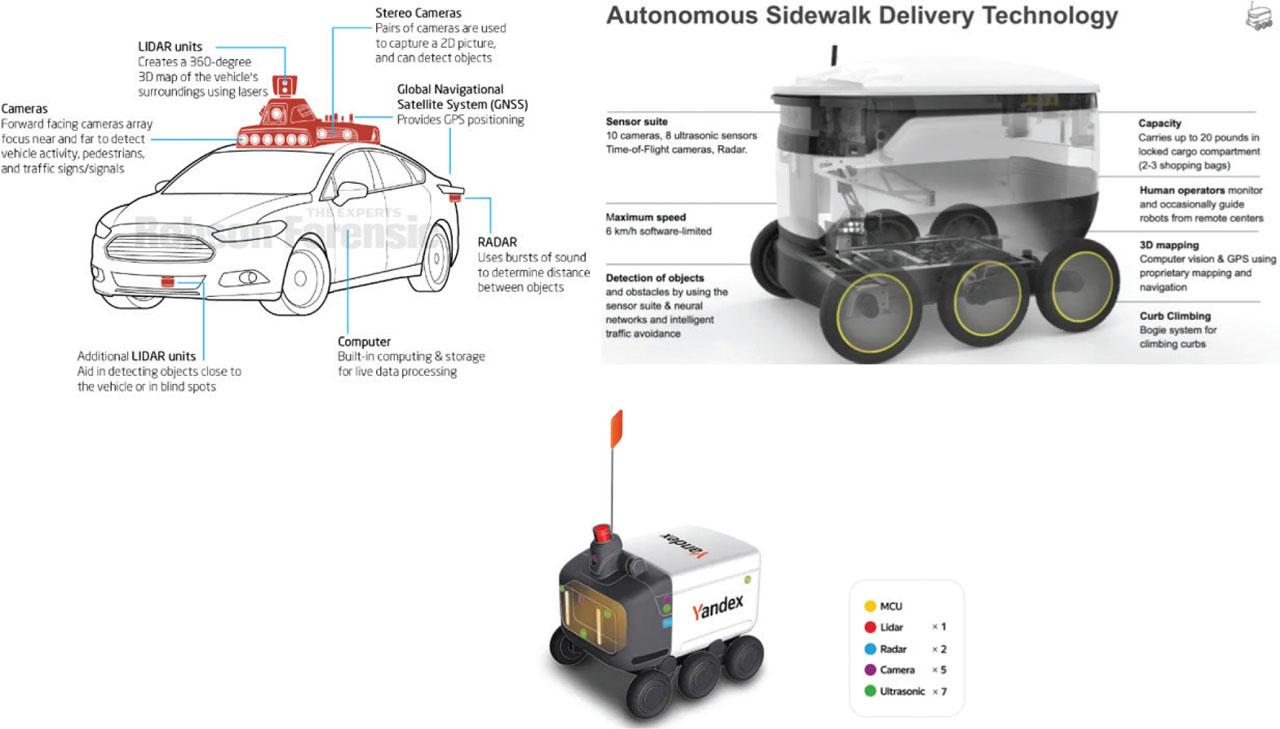

In the realm of autonomous vehicles and delivery robots such as starship and Yandex R3, current state-of-the-art systems predominantly rely on sophisticated sensor fusion techniques to navigate and make decisions (Leiss 2018; Kosonen 2020; Lubenets 2021). These systems typically incorporate a range of sensors, including Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR), ultrasonic sensors, multiple radars and a variation of cameras, to gather comprehensive environmental data. LiDAR, for instance, emits laser pulses to measure distances to surrounding objects, creating detailed 3D maps. Ultrasonic sensors and radars are used to detect nearby obstacles, particularly in close-range scenarios. Additionally, multiple cameras and stereo cameras are strategically placed around the vehicle to provide a 360-degree view, aiding in object detection, classification and tracking (Wolf et al. 2010; Leiss 2018; Kosonen 2020; Lubenets 2021). The examples of platforms and their sensors in configuration are shown in Figure 1. Most of these systems are inherently active in nature, as they emit signals outward to collect data, which is then processed to inform navigation and decision-making algorithms.

Representation of autonomous car and delivery robots with their sensors (Leiss (2018); Kosonen (2020); Lubenets (2021)).

However, this reliance on multiple sensors and complex camera systems introduces significant challenges, particularly in terms of sensor calibration, data synchronisation and the need for robust algorithms to fuse data from disparate sources. As highlighted in the review by Yeong et al. (2021), these challenges include the difficulty of maintaining accurate sensor calibration across various environmental conditions, the complexities of achieving real-time data fusion and the increased computational load associated with processing inputs from numerous sensors simultaneously (Yeong et al. 2021).

Yang et al. (2020) proposed methods to address the previously mentioned challenges by using panoramic vision with simultaneous localisation and mapping (SLAM) based on multi-camera collaboration. Their study aimed at utilising the characteristics of panoramic vision and stereo perception to improve the localisation precision in off-road environments on top of a UGV (Yang et al. 2020). In this study, instead of focusing on the localisation process of the UGV, object detection is addressed for target approach using a single passive panoramic camera sensor. The sensor architecture is further simplified by using only a single passive 360-degree panoramic camera. This streamlined set-up aims to mitigate the challenges associated with multi-sensor systems by eliminating the need for complex sensor calibration and fusion processes making the whole system more compact in architectural and computational terms.

There is a definitive steady global increase in military UGV development and sales (Gordon 2022; Sejal 2022; Joshi and Katare 2024). This also means that UGVs will be more frequently deployed in different conflicts around the world (Mizokami 2018; Army Recognition 2023b). In one of the latest wars, the conflict between Russia and Ukraine had become a stage for testing various unmanned ground, water and aerial vehicles (Army Recognition 2023a; Askew 2023; Baker 2023; Shmigel 2023; Sutton 2023). Leading UGV manufacturers share some information about their vehicles in news outlets or at public exhibitions, allowing some technical data, particularly on older models, to be publicly accessible. However, details regarding the latest UGVs, especially related to Artificial Intelligence (AI) systems and specific functionalities, remain undisclosed (Andersson 2021). This can be understood because of the sensitive nature of the system details. However, this also limits the public development and amount of recent unclassified literature (Mansikka et al. 2023).

There have not been many UGVs developed to be used as a self-destructing loitering mine before the Ukrainian war, except for the Iranian Heidar-1 and Laykka platform that has been in development since 2018 (Atherton 2019; Andersson 2022). Several UGVs with similar capabilities are currently being developed in the Ukrainian theatre of war (Kirill 2022; Bureau 2023; Malyasov 2023), although they are mostly teleoperated and pose none or very limited amount of autonomy or AI capabilities (Andersson 2022). As previously noted, information regarding sensors and AI systems is often withheld from public access. This paper provides a detailed disclosure of the sensor techniques employed in AI for target recognition within military UGVs.

The work presented in this paper is part of an ongoing autonomous UGV Laykka project (Hemminki et al. 2022), which explores the potential functionalities of UGVs, and aims to develop a UGV that is cost-effective and straightforward in design. This makes it suitable for sacrificial use in a military context (Andersson et al. 2024).

The Laykka UGV is meant to provide real-time recognition information about the enemy in the combat field, by operating in front of deployed troops. If needed the UGV can destroy or damage enemy vehicles, armoured vehicles and also personnel by using its self-destruct properties or weaponized modules. Laykka relies solely on passive sensors in its operation and one of its main sensors is the 360-degree camera whose functionality is based on the framework proposed in this study. Depending on the module and its incorporated AI, the platform can be programmed to perform according to required mission parameters (Andersson et al. 2024).

The concept consists of a platform that has several different modules of which each incorporates its own specific mission-type AI. These AIs will modify the behaviour of the UGVs based on the capabilities and specifications of the attached modules. In this context, a module is a distinct assembly of components and programmes including AIs that are incorporated in one distinct system that can be easily removed, added or replaced as a part of a larger system.

Laykka AI should be able to recognise different tracked armoured combat vehicles and be able to distinguish between them. The proposed framework takes into account the unique environmental challenges and task-specific requirements of military operations. These challenges arise from different military operation areas encountered in Finland such as woodlands and winter conditions. During a possible skirmish, additional factors such that the situation and environment may affect visual perception of the camera on UGVs include a near-maximum speed of traversal in uneven terrain, limited time-budget of approach to target with no chances to pauses or second attempts, and varying weather and illumination conditions. Figure 2 represents the Laykka platform with a 360-degree camera module. The camera is placed in the middle top to give the best possible view of the surroundings. If necessary, the camera can be protected against sunshine and rain using the camera reflection cover.

Laykka platform with mine-module and 360-degree camera module installed on top.

Object detection is a common challenge in ML-oriented projects (Qiu et al. 2019; Zhang et al. 2019; Jafarzadeh et al. 2023; Naik and Hashmi 2023). Several studies highlight the challenges in assessing the accuracy and reliability of object detection due to varying environmental conditions and the difficulty of conducting repeated tests in realistic scenarios (Kulchandani and Dangarwala 2015; Liang et al. 2024).

Object detection ML models can be divided into two categories: two-stage detectors and single-shot detectors. Two-stage detectors consist of region proposal networks (RPN) to generate proposal bounding boxes (BBs) of objects to be classified. Single-shot detectors do class prediction and BB estimation simultaneously. In this paper, three ML models for object detection were tested: SSD with ResNet50 as the feature extractor, Faster-RCNN with ResNet50 as the feature extractor and EfficientDet D1 (He et al. 2016; Liu et al. 2016; Ren et al. 2016; Tan et al. 2019).

Faster R-CNN enhances R-CNN and Fast R-CNN by incorporating an RPN to generate object proposals directly from feature maps. It uses two modules: a convolutional network for feature extraction and an RPN for proposal generation, followed by a second network for classification and BB refinement (Ren et al. 2016).

Single shot detector (SSD) is known for its speed and accuracy, detecting objects using a single neural network that predicts BBs and class probabilities from feature maps. It is well-suited for real-time applications like autonomous vehicles and surveillance (Liu et al. 2016).

EfficientDet optimises model depth, width and resolution to achieve high accuracy and computational efficiency; it is built on the EfficientNet architecture. It is notable for its balanced scaling approach, making it highly effective for object detection tasks (Tan and Le 2019; Tan et al. 2019).

ResNet, or Residual Network, devised by He et al. (2016), tackled the vanishing gradient problem by introducing skip connections. These connections circumvent the degradation of signal during backpropagation in exceedingly deep networks. This innovation enabled the construction of networks surpassing a 1,000 layers.

The selection of reference methods for object detection was based on their prevalent use in the existing literature, as well as their computational efficiency. The performance of object detection models was a significant concern throughout the conducted project. It was crucial to choose computationally efficient models that could deliver fast and accurate results. Laykka’s system hardware is computationally limited, which necessitated the choice of these models to ensure that they could operate effectively within the system’s constraints. On average, two-stage detectors perform better than single-shot but are slower (Zelioli 2024).

The 360-degree camera has gained popularity for its ability to capture an entire scene. Several applications have emerged that utilise 360-degree cameras for object detection with ML models (Zhang et al. 2017; Yang et al. 2018; Wang and Lai 2019; Premachandra et al. 2020; Xu et al. 2020; Rashed et al. 2021). Yang et al. (2018) proposed a multi-projection variant of a detector and demonstrated its effectiveness in object detection with low-resolution inputs. Wang and Lai (2019) proposed a deep learning-based object detector specifically designed for 360-degree images, which outperforms other methods in terms of accuracy. Premachandra et al. (2020) investigated the detection and tracking of moving objects at intersections using a 360-degree camera and demonstrated high detection rates and effective tracking within 25 m of moving objects.

Demir et al. (2020) implemented panoramic image object detection using a high-resolution omnidirectional imaging platform tailored for drone detection and tracking. The system employs 16 cameras, each with 20-megapixel resolution, to achieve an aggregate resolution of 320 megapixels, enabling comprehensive 360-degree surveillance. This complex setup allows for the detection of drones with a 100 cm diameter from a distance of up to 700 m, making it effective for both short-range and long-range monitoring scenarios. The platform is capable of processing high-resolution video in real-time, meeting the demanding requirements of rapidly changing environments (Demir et al. 2020).

This implementation closely resembles the object detection system described in the paper, which is deployed on ground vehicles in outdoor military settings. However, the approach presented in this paper diverges by utilising a single 360-degree camera, simplifying the system’s complexity compared with the multi-camera set-up described by Demir et al. (2020). The used Laykka platform has significant limitations to its size and energy consumption and hence Demir et al.’s (2020) solution could not be implemented as is.

The camera sensor used in this paper is a Picam 360-degree camera. The technical specifications of this camera are provided in Section 3.3. The Picam 360 camera was also used in a recent study by Nguyen et al. (2023) to enhance unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) landings, due to its ability to observe the 360-degree environment through its fisheye lens. The key distinction in this approach is the transformation of the fisheye view into a panoramic view for subsequent processing, rather than using the fisheye view directly in its original form.

This section provides a detailed overview of the framework, its integration with the Laykka system and the specifications of the sensor employed. First, the framework designed for object detection using fisheye images is introduced. Next, the process of integrating this object detection module within the Laykka AI module is described. Finally, the selected sensor is outlined, including its capabilities and the approach taken to incorporate it into the system.

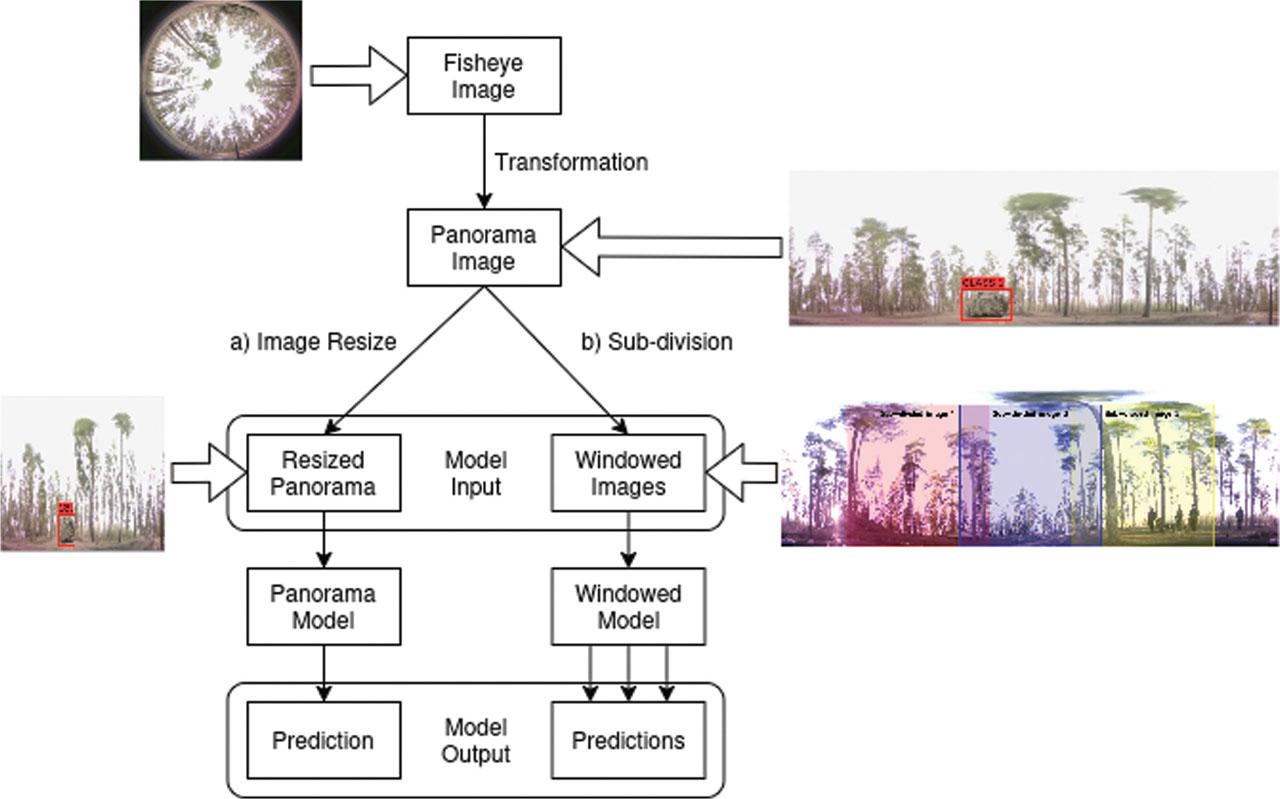

The framework depicted in Figure 3 is designed to process fisheye images and generate predictions through two distinct model types: a panoramic model for general situational awareness and a windowed model for targeted detection with adaptive windowing. The system at hand can then either use the panorama model for a global scene prediction or the windowed model for multiple localised predictions, depending on the application needs.

Detection framework for converting fisheye images into a panoramic format, followed by model-based inference using one of two alternative configurations. After transformation, the panorama image can either be (a) resized and passed through a Panorama Model for full-image detection, or (b) subdivided into fixed-size windows and processed by a Windowed Model for localised detection. Arrows indicate sequential data flow from image input to prediction output.

Initially, the fisheye image is transformed into a panoramic format. The Fisheye-to-Panorama transformation is integrated into the framework for two reasons. First, the transformation corrects the significant geometric distortions that vary depending on the spatial position within the fisheye projection. By contrast, panoramic images present geometries that are more realistic and consistent with substantially reduced distortion, hence, decreasing the complexity of the learning process required for AI models. Second, this process reduces the complexity and effort required for data annotation, as fisheye views are less intuitive to humans compared with panoramic views. This transformation improves readability, allowing for more precise identification and labelling of objects, ultimately supporting higher-quality data for model training. The fisheye-to-panorama transformation process is explained in detail in Section 3.3.

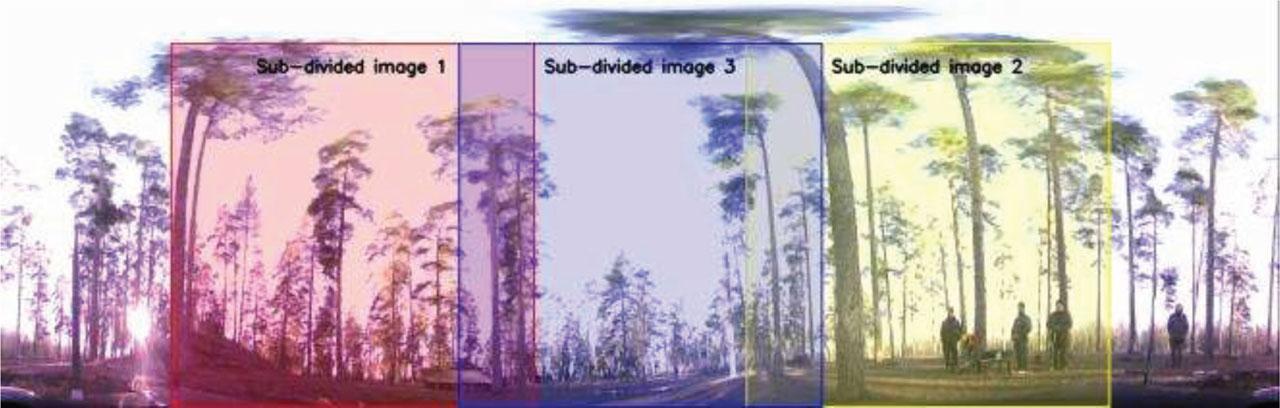

The fisheye image is first converted into a panoramic view, which is then processed using either of two approaches: (a) resizing for a global model or (b) dividing it into multiple smaller windows for localised detection. This process is illustrated in Figure 4. These windowed images serve as inputs for the Windowed Model, facilitating a finer-grained analysis of specific regions within the scene. Once the model inputs are prepared, each path follows a distinct processing approach. The resized panoramic image is processed by the Panorama Model, generating a single prediction that reflects the global context of the scene. Meanwhile, each windowed image in Path b is independently processed by the Windowed Model, producing separate predictions for each local region.

The panoramic image is divided into smaller, fixed-size windows to cover the full horizontal field of view. To ensure reliable target detection, the windows are configured with slight horizontal overlap. This overlap allows targets that lie near the edge of one window to still be visible in adjacent windows, reducing the chance of missed detections due to boundary clipping. In practice, this overlapping strategy helps maintain spatial continuity between frames.

The system can now, depending on the model type used, process either a single prediction or multiple predictions. If the Panorama Model is employed, the system works with a single, global prediction that captures the overall context of the panoramic scene. Alternatively, if the Windowed Model is used, the system processes multiple localised predictions, each corresponding to a specific region within the panorama. This set-up enables the system to adapt to different application requirements, whether a holistic understanding of the entire scene is necessary or a detailed, region-by-region analysis is more beneficial. The ability to select between global and localised processing paths ensures that the framework can handle a variety of tasks by leveraging either broad contextual insights or focused, detailed observations.

A windowed configuration could also be implemented in a parallel set-up, enabling a more modular and flexible system. In this approach, each window could be analysed or processed independently, allowing the system to scale more easily and adapt to various tasks. By having multiple processes, the system could potentially make decisions independently within each window, improving efficiency and enabling faster responses.

To structure the evaluation of the proposed framework, a two-stage testing approach was adopted, consisting of offline benchmarking and online field demonstrations. This method is commonly used in the ML and autonomous systems domains, where offline tests allow for controlled benchmarking of model performance on annotated datasets, and online tests enable assessment under real-world operational constraints and system integration factors (Zhang et al. 2022). Methodologically, this study follows a case-study approach, commonly used in systems engineering and prototyping. The Laykka UGV platform serves as a clearly defined unit of analysis, and the Laykka AI module represents the implementation of the proposed perception framework within this platform. In this context, the Laykka AI module is not only a component but the central system under evaluation.

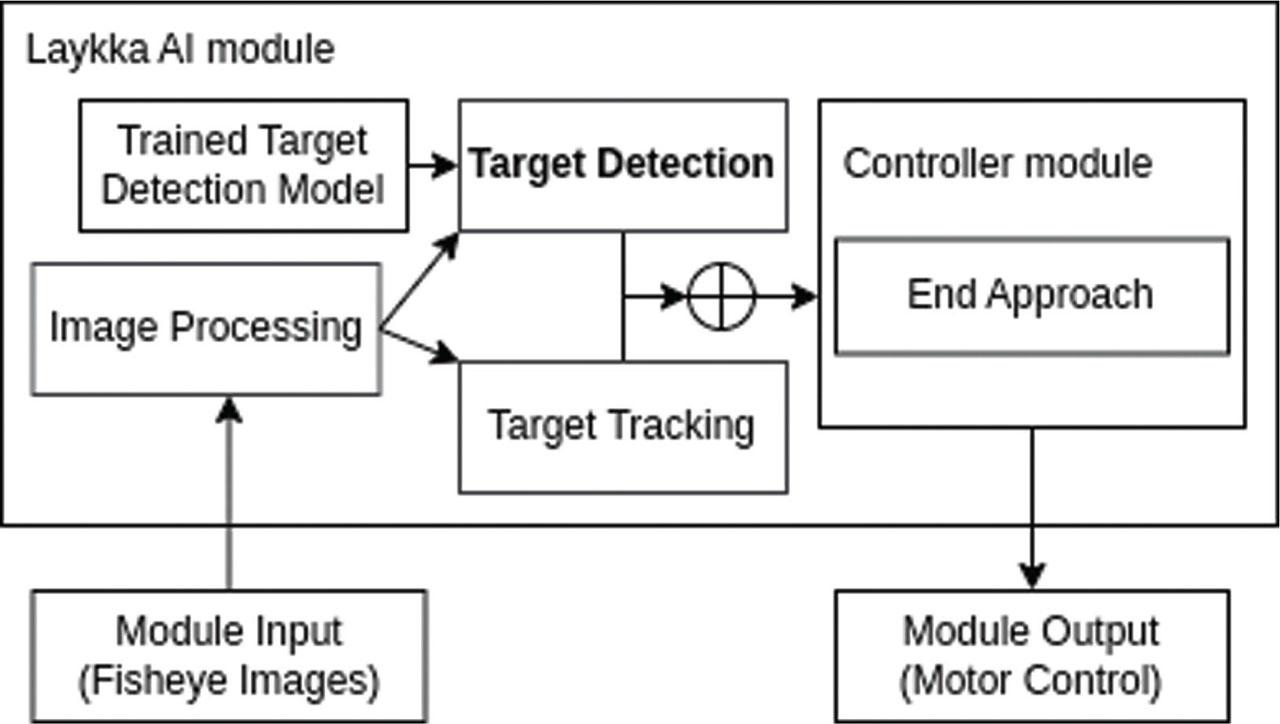

The integration of the object detection module (camera and ML model) into the Laykka AI module and its role in the system is depicted in Figure 5. The Laykka AI controller module in operation works as follows: fisheye images obtained by the panoramic camera sensor undergo the desirable format through image processing. The target detection model then identifies the target on the processed images. Concurrently, a target tracking system works to ensure continuous tracking of the detected object in case the model loses the target. The result of the target detection model plays a critical role within controller module which determines the motor control based on the model’s results. The output from the controller module is a set of signals for motor controllers, thus controlling the vehicle to perform according to the desired state. As previously mentioned in Section 3.1, there are two model configurations: windowed and panorama. Depending on the selected model configuration, the Laykka AI module is configured to handle either a single prediction (in the case of the panorama model) or multiple predictions concurrently (in the case of the windowed model).

Overview of the Laykka AI control module, which integrates object detection and tracking for autonomous decision-making. Arrows indicate data flow: fisheye images undergo preprocessing and detection, feeding into a target tracking component that maintains temporal consistency. These results jointly inform the controller module, which generates motion signals and can trigger an end-approach manoeuvre when conditions are met. The dual-path detection (direct and via tracking) improves robustness in the case of incorrect target detection. AI, artificial intelligence.

In the implementation of the framework presented in this paper, a 640 × 640 resolution was utilised to comply with the computational limitations of the Laykka platform, allowing the model to generate predictions efficiently. In the panorama model configuration, panoramic images were resized to this resolution, which results in a reduction of image detail that can lead to significant data loss and negatively affect model accuracy. In operation, these resized panorama images are input directly into the model, and the outputs are subsequently fed into the controller module for determining the module motor control signal. In the windowed configuration the panorama images are cropped images, which preserves the native pixel detail but restricts the model’s field of view to a smaller portion of the scene. This configuration operates by subdividing the panoramic scene into multiple 640 × 640 resolution windows, with each section analysed individually to produce localised predictions. When a target is detected, the system focuses on the corresponding window, dynamically adjusting its position to track the target. The predictions generated on this focused window are then used in the controller module, which determines the motor control signal.

Windowed configuration introduces additional complexity, as the integrated system must be programmed to handle multiple windows. In the system presented, if the object detection achieves a sufficient confidence threshold of 85% and maintains detection over five consecutive frames, the Laykka AI module creates a new window around the predicted target. The new window configuration dynamically updates its position to contain the predicted target in the middle, tracking the target’s movements. A BB is used to determine where in the image the target is. Once the Laykka AI module locks onto the target within this windowed setup, a pixel-based tracker supports continuous target following, compensating for any intermittent detection losses.

Sections 1 and 2 emphasised the importance of utilising cost-effective, user-friendly instruments with a broad range of readily accessible applications. For the Laykka AI module, the PICAM360-4KHDR camera was selected and connected to a computer via a Universal Serial Bus (USB)-A connector; see Figure 6. A camera module was placed on top of the Laykka to provide an omnidirectional view of the surroundings. The PICAM360 camera module initially produced fisheye images. However, detecting objects in such images presented a challenge due to distortions of nearby objects. As a result, it was decided to integrate an omnidirectional panoramic image transformation into the system to represent nearby objects in a more realistic manner.

PICAM360 camera module (Picam360 Developer Community, P. I 2023). USB-a connector allows for an easy integration with Laykka platform.

The selected camera has the capability to capture high-resolution (4k) images. However, due to the incompleteness of the original fisheye image, achieving a realistic, distortion-free image transformation was not possible. Consequently, a 2k (2,048 × 1,536 pixels) resolution image was chosen instead. The decision to use 2k resolution instead of 4k was additionally supported by a higher camera frame rate.

Specifically, the 4k resolution offered a frame rate of 15 frames per second (fps), whereas the 2k resolution provided a more favourable frame rate of 30 fps. For the experiment, no calibration was performed, as the camera was utilised in its default unmodified state, directly out of the box.

Each original fish-eye image is transformed into a panoramic image, addressing the inherent distortion in fisheye lenses and producing a wide-angle view suitable for further processing. The transformation process involves the creation of a pixel-by-pixel map from a fish-eye perspective to a panoramic view. It is done by applying geometric calculations to remap each pixel’s position. The core logic lies in generating a mapping that straightens out the fisheye distortion. This mapping is then used to transform the fisheye image into a panoramic representation. The process involves calculating new coordinates for each pixel based on their original fisheye positions. This results in a wider, undistorted view of the captured scene.

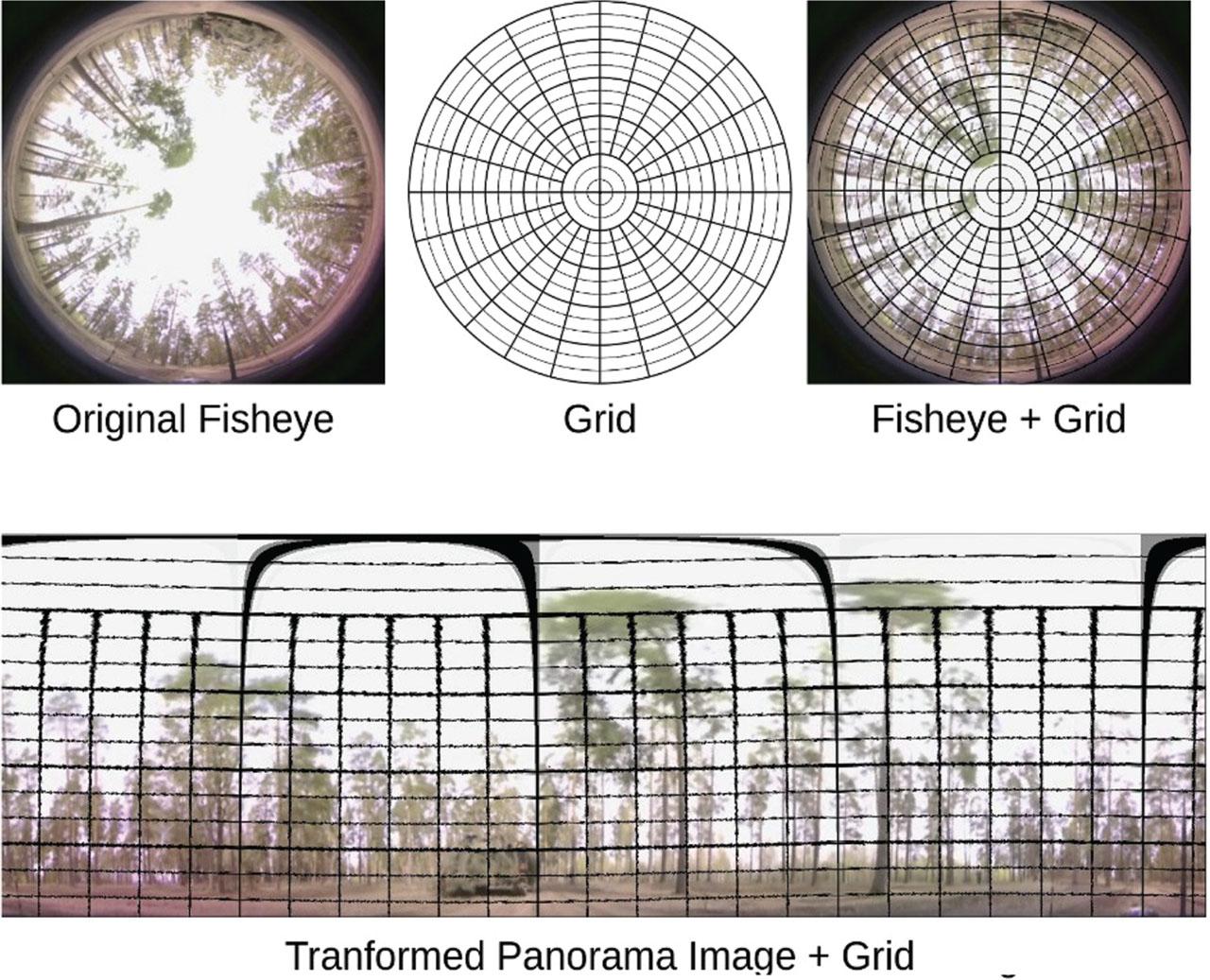

Figure 7 illustrates the image transformation with the grid addition. The images from the camera module were processed to create panoramic representations. A grid is overlaid on the image to aid in visualising pixel mapping. To improve efficiency, the pixel map is pre-generated, and a straightforward algorithm is then applied to remap the fish-eye image into a panoramic format using this map. Although objects near the top of the image appear distorted, this is not a significant issue, as the primary objects of interest are typically located near the bottom of the image. The resulting processed panorama image is 2,255 × 718 pixels. The fish-eye-to-panorama transformation is performed in three main steps. First, mapping coordinates are computed to translate the polar layout of the fisheye image into a rectangular panorama. For each pixel in the target panorama, a corresponding source coordinate in the fisheye image is calculated based on the radius and angle. Second, an initialisation step calculates key parameters: the centre of the fisheye image (Cx, Cy), the usable outer radius (R) and the desired output dimensions. Using these, remapping matrices are generated via the OpenCV-based mapping function. Third, the fisheye image is remapped with linear interpolation, producing the panoramic output. The detailed transformation process is outlined in Algorithm 2 (Rankin 2020).

Object Detection using ML Model

| 1: | Input: Panoramic or windowed image I, previous bounding box Bprev |

| 2: | Output: Detected bounding box Bdet, confidence score Sdet, class label Cdet |

| 3: | Step 1: Load Model and Configuration |

| 4: | Load pretrained object detection model M |

| 5: | Set detection threshold and relevant parameters |

| 6: | Step 2: Prepare Input |

| 7: | Preprocess image I for model input |

| 8: | Step 3: Run Object Detection |

| 9: | Pass image through model: D = M(I) |

| 10: | Extract Bdet, Sdet, and Cdet |

| 11: | Step 4: Filter Predictions |

| 12: | for each detected object do |

| 13: | if confidence score below threshold then |

| 14: | Ignore detection |

| 15: | end if |

| 16: | if Bprev exists then |

| 17: | Compute overlap with previous detection |

| 18: | Define if detection is valid |

| 19: | end if |

| 20: | end for |

| 21: | Step 5: Select Best Detection |

| 22: | Choose highest-confidence valid detection |

| 23: | if no valid detections found then return “no detection” |

| 24: | end if |

| 25: | Return Bdet, Sdet, and Cdet |

Fisheye-to-Panorama Transformation (using opencv-python package (cv2) (Rankin 2020; OpenCV Tracker API 2023))

| 1: | Input: Fisheye image Ifisheye of size (Hf, Wf) |

| 2: | Output: Panoramic image Ipanorama of size (Hp, Wp) |

| 3: | Step 1: Compute Mapping Coordinates |

| 4: | procedure BuildMap(Wp, Hp, R, Cx, Cy, offset) |

| 5: | Initialize mapx, mapy ← zero matrices of size (Hp, Wp) |

| 6: | for y ← 0 to Hp − 1 do |

| 7: | for x ← 0 to Wp − 1 do |

| 8: | Compute radius:

|

| 9: | Compute angle:

|

| 10: | Compute source coordinates: |

| 11: | xs ← Cx + r × sin(θ) |

| 12: | ys ← Cy + r × cos(θ) |

| 13: | mapx[y, x] ← xs |

| 14: | mapy[y, x] ← ys |

| 15: | end for |

| 16: | end for |

| 17: | return mapx, mapy |

| 18: | end procedure |

| 19: | Step 2: Initialize Unwrapper |

| 20: | procedure Initialize Unwrapper(Hf, Wf, Cb, offset) |

| 21: | Cx ← Hf/2, Cy ← Wf/2 |

| 22: | Compute outer radius: R ← Cb − Cx |

| 23: | Compute output image size: |

| 24. | Wp ← ⌊2 × (R/2) × π˼ |

| 25: | Hp ← ⌊R˼ |

| 26: | (mapx, mapy) ← BuildMap(Wp, Hp, R, Cx, Cy, offset) |

| 27: | end procedure |

| 28: | Step 3: Transform Fisheye Image |

| 29: | procedure Unwrap(Ifisheye, mapx, mapy) |

| 30: | i ← cv2.INTER LINEAR |

| 31: | Ipanorama ← cv2.remap(Ifisheye, mapx, mapy, i) |

| 32: | return Ipanorama |

| 33: | end procedure |

Fisheye image transformation visualisation. The grid helps to visualise before and after the transformation.

This section will present the results of the comparison for both framework model approaches, starting with an overview of the evaluation data, including how it was collected, annotated and augmented. Overview of the performance metrics used for evaluation will be provided. The object detection results will then be presented, followed by an analysis of how the integration of the object detection module into the Laykka system was tested in real-world field tests, where the system’s ability to detect and track targets in dynamic environments was assessed.

The critical feature of building an effective Laykka AI module lies in acquiring a diversified dataset that accurately represents the tested environment and its objects. This dataset forms the foundation for training the detection model, enabling it to discern combat vehicles in various scenarios. During data collection, the aim was to capture images of the combat vehicles from as many angles and environmental conditions as possible to achieve the desired objective. Collecting data from different angles, distances and lighting conditions ensures the model’s robustness and adaptability in real-world situations. The environment during data collection was similar to that of the final real-world tests. The images were gathered from the forest across all four seasons. Combat Vehicle 90 (CV90) and BMP-2 were chosen as the two targets for this research. The collected image data was manually annotated and the resulting dataset offers ground-level truth labels for the BMP-2 and CV90 combat vehicles. This section provides an overview of the data collection process, along with details about the annotation and augmentation techniques used to improve the training.

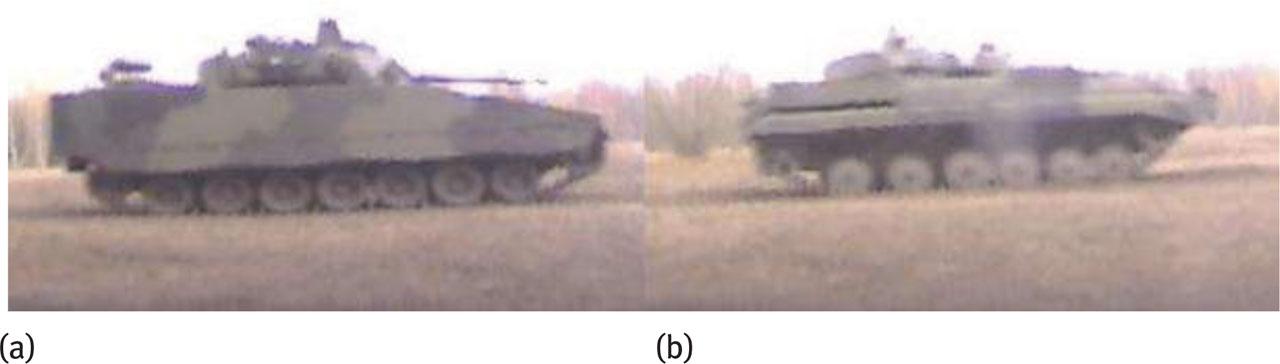

A total of 7,323 images underwent manual labelling, with 4,582 BMP-2 combat vehicle images and 2,741 of the CV90 combat vehicle. An example image of a CV90 target and a BMP-2 target is shown in Figure 8. CV90 has a more angular, boxy hull, with a relatively flat front and sides, while BMP2 has a more rounded and cylindrical appearance, especially around the front and turret areas. The discrepancy in the number of collected images for the two vehicle types arises from considerations of the availability and prevalence of these vehicles in the testing environment.

The annotated dataset was split into training (≈80%), validation (≈10%) and test sets (≈10%).

Example images of CV90 combat vehicle (a) and BMP-2 combat vehicle (b) classes.

It is important to note that the training set images were not randomly selected. Instead, folders containing images from separate military scenarios with different environmental conditions were chosen. These conditions included variations in daytime lighting and vegetation cover. Random selection for training and test/validation sets would have introduced bias due to the high similarity among images. Therefore, a strategy was adopted in which entire sets of images from distinct scenarios were exclusively allocated to either the training or test/validation sets, thereby potentially limiting bias. This will be discussed in more detail in Section 5.3 on research limitations.

The images in the training set were augmented, but the total amount of images was not increased (see Table 1). Table 1 summarises the parameters of the different augmentation techniques employed in this study, including random adjustments to brightness, contrast, saturation and hue, as well as random rotations. There is no single best augmentation technique for all datasets (Kaur et al. 2021). Augmentation functions were selected by observing which one had a positive effect on the training, and the parameter values were chosen with an educated guess. The minimum and maximum values in Table 1 refer to the range of values that were applied to a specific augmentation technique. These techniques were applied once to each training image to increase the diversity and variability of the images in the dataset, ultimately improving the accuracy and robustness of the system presented. The training data encompasses variations in background, lighting, weather conditions and target distance. It also features images with targets obscured by trees or bushes, along with a focus on capturing varying levels of sunlight.

Augmentation techniques used in the study

| Technique | Min. value | Max. value |

|---|---|---|

| Random adjust brightness | 0 | 0.5 |

| Random adjust contrast | 0.4 | 1.25 |

| Random adjust saturation | 0.4 | 1.25 |

| Random adjust hue | 0 | 0.01 |

| Random rotation | 0° | 10° |

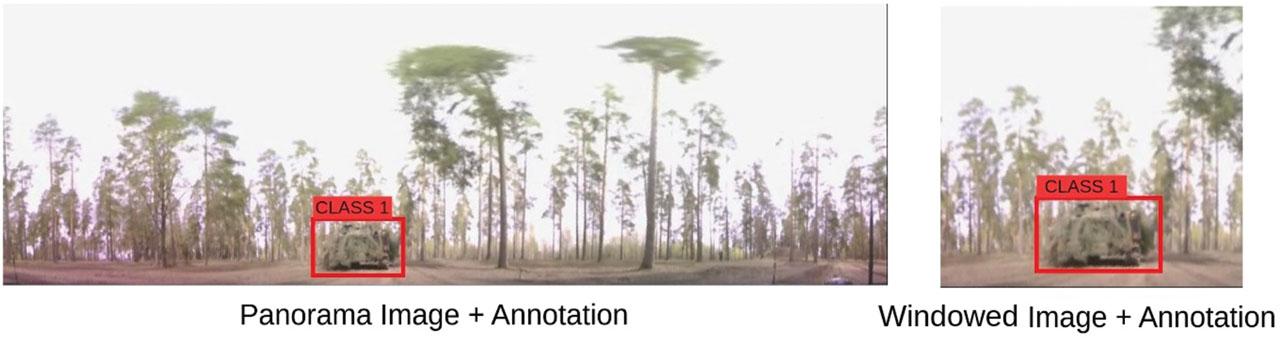

Figure 9 shows examples of both image types used in training, with the full annotated panorama image on the left for the panorama configuration, and the cropped, annotated view on the right for the windowed configuration. For the windowed model type, the training images are cropped around the combat vehicle of interest. The cropped image size equals the model input size, which in this case is a 640 × 640 image. In the case where the AI control module operates with the panorama-trained model, no cropping is necessary, as the entire panoramic image can be processed without sub-division.

Example of two types of the same image used in the training.

Performance metrics are essential for evaluating the accuracy of object detection systems. A common metric is Intersection over Union (IoU), which measures the overlap between predicted and ground truth BBs. IoU values range from 0 to 1, with 1 indicating a perfect match. However, due to human annotation discrepancies, perfect matches are rare, and IoU values typically reflect some margin of error. IoU is used to define other key metrics like precision and recall. Precision is the ratio of true positives (TP) to the total number of predicted positives, while recall is the ratio of TP to the total number of ground truth positives. TP, true negatives (TN), false positives (FP), and false negatives (FN) are used to classify each detection.

Average precision (AP) is a summary measure of model performance, calculated as the area under the precision–recall curve for various IoU thresholds. It provides a single value that summarises the trade-off between precision and recall at different thresholds. Mean average precision (mAP) is the average of AP values for all object classes in a dataset and is commonly reported for IoU thresholds of 0.5, with AP for small objects (APs), AP for medium objects (APm), and AP for large objects (APl), which indicate the model’s performance based on object size. The pixel ranges defining these size categories are provided in Section 4.3. Additionally, the Confusion Matrix (CM) is utilised to further assess classification performance. The CM shows the counts of TP, FP, FN and TN, which helps in understanding the model’s classification errors.

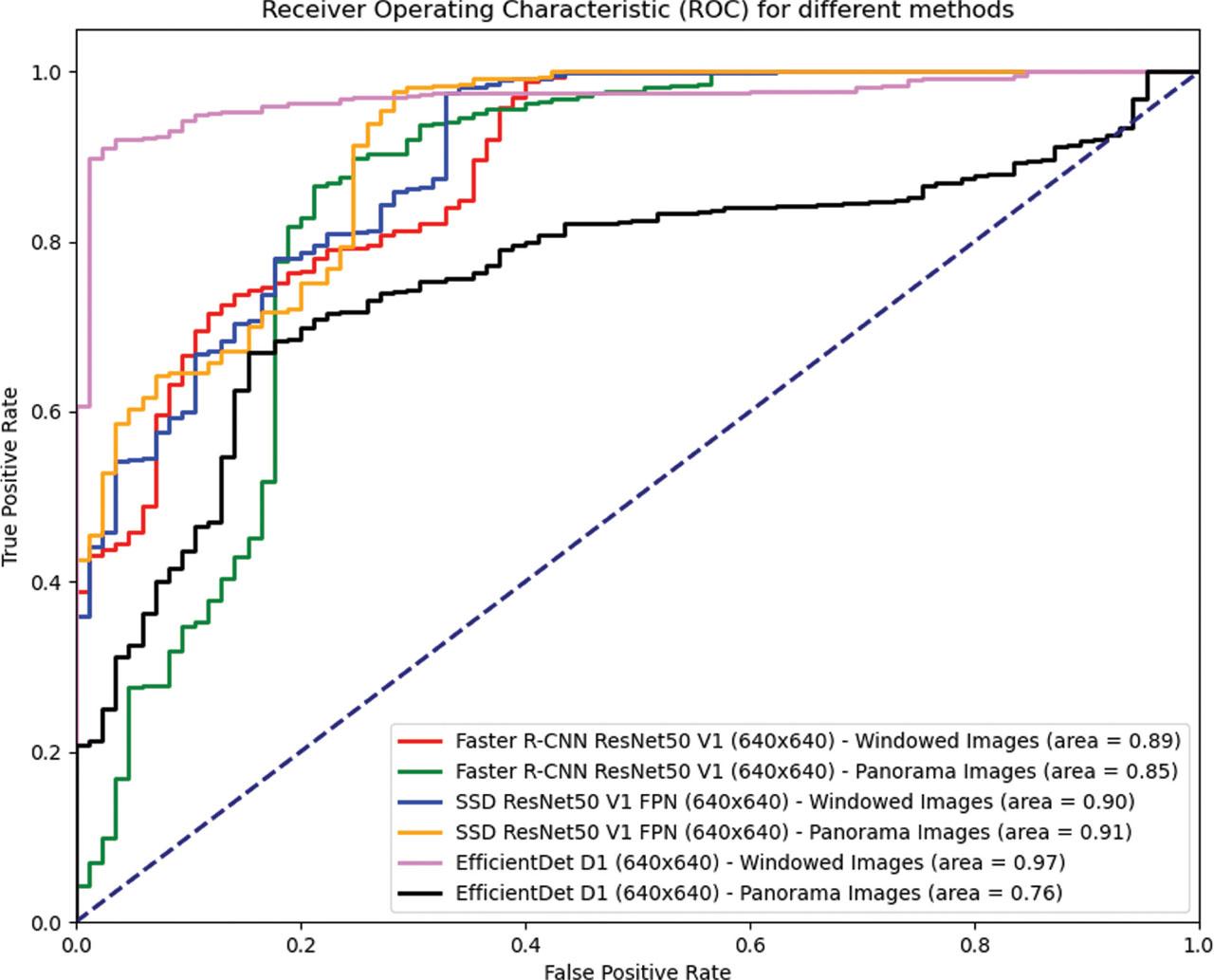

The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve is another evaluation tool, illustrating the trade-off between TP rate (recall) and false positive rate (1 – specificity) at various thresholds. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) indicates the model’s ability to discriminate between classes, with higher values representing better performance.

This section presents an evaluation of three CNN-based object detection models tested on two types of datasets: windowed and panorama images. The structured process of object detection is summarised in Algorithm 1. The analysis focuses on comparing the models’ effectiveness across different object sizes and image contexts.

Table 2 displays the AP percentages of three different types of CNN-based detectors, all trained with the same input image size of 640 × 640 pixels. APs is the AP value for small objects defined as those with an area less than 32 × 32 pixels. APm is the AP value for medium objects defined as those with an area between 32 × 32 pixels and 96 × 96 pixels. AP is the AP value across all object sizes.

AP: @0.5 comparison of object detection models on different object sizes, trained on panorama and windowed images (640 × 640 resolution)

| Model | Trained on panorama images | Trained on windowed images | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APs | APm | APl | AP | APs | APm | APl | AP | |

| SSD ResNet50 V1 | 0.151 | 0.350 | 0.663 | 0.526 | 0.151 | 0.285 | 0.674 | 0.511 |

| Faster R-CNN ResNet50 V1 | 0.101 | 0.243 | 0.661 | 0.471 | 0.151 | 0.268 | 0.667 | 0.501 |

| EfficientDet D1 | 0.000 | 0.197 | 0.588 | 0.402 | 0.151 | 0.418 | 0.692 | 0.567 |

AP, average precision.

The results indicate that EfficientDet D1 achieved the highest overall AP on windowed images at 0.567. For panorama images, SSD ResNet50 V1 showed the best performance with an AP of 0.526. All models generally performed better on windowed images compared with panorama images, with the exception of the SSD model, which maintained a consistent performance for large object detection across both datasets.

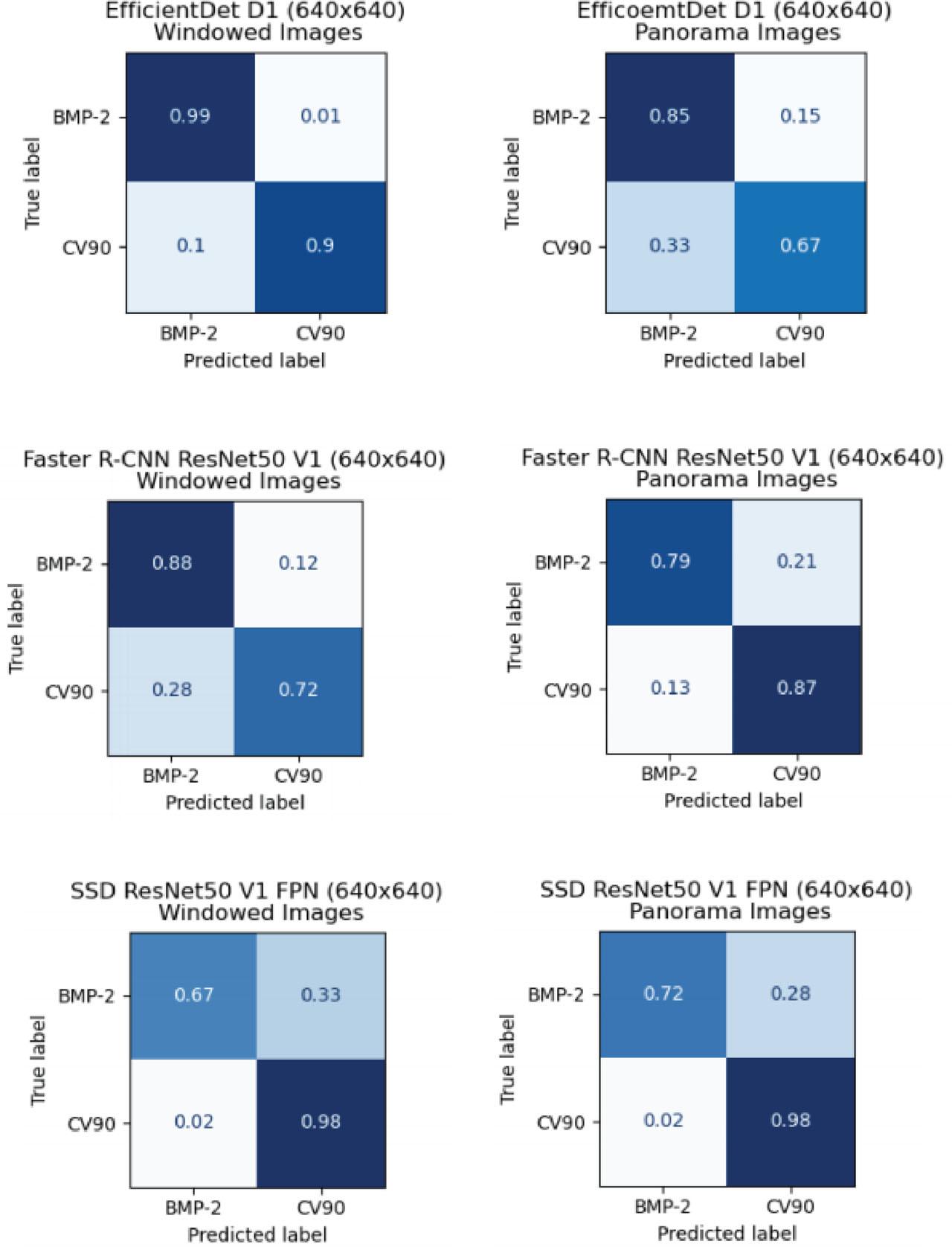

Figure 10 displays the confusion matrices for three object detection models: EfficientDet D1, Faster R-CNN ResNet50 V1 and SSD ResNet50 V1 FPN. Each model was assessed using two types of images: windowed images and panorama images, both at a resolution of 640 × 640 pixels. The target classes were BMP-2 and CV90.

A comparison of the models is provided in the form of confusion matrices illustrating the performance of the models on the (left column) windowed and the (right column) panorama image datasets with a resolution of 640 × 640 pixels. Three different models, namely EfficientDet D1, Faster-RCNN ResNet50 V1 and SSD ResNet50 V1 FPN were evaluated. The matrices demonstrate the success rates of distinguishing between the BMP-2 and CV90 classes, with more diagonal values being preferable because they indicate better classification.

EfficientDet D1 (Windowed images): This model performed well for both classes. The classification accuracy for BMP-2 reached 99%, with only 1% misclassified as CV90. For the CV90 class, the accuracy was 90%, with 10% misclassified as BMP-2.

EfficientDet D1 (Panorama images): The model’s performance declined when tested on panorama images. For the BMP-2 class, accuracy fell to 85%, with 15% misclassified. For CV90, the accuracy decreased to 67%, resulting in a higher misclassification rate of 33%.

Faster R-CNN ResNet50 V1 (Windowed images): This model also demonstrated strong performance on windowed images. It achieved 88% accuracy for BMP-2 and 72% for CV90. The misclassification rates were 12% for BMP-2 and 28% for CV90.

Faster R-CNN ResNet50 V1 (Panorama images): Performance further declined when evaluated on panorama images. The accuracy for BMP-2 dropped to 79%, while CV90’s accuracy was 69%. The respective misclassification rates were 21% and 31%.

SSD ResNet50 V1 FPN (Windowed images): This model showed relatively weaker performance compared with the others on windowed images, achieving 87% accuracy for BMP-2 and 64% for CV90. Misclassification rates were 13% for BMP-2 and 36% for CV90.

SSD ResNet50 V1 FPN (Panorama images): On panorama images, SSD ResNet50 V1 FPN exhibited the lowest performance among the models. BMP-2 was classified with an accuracy of 77%, while CV90 had an accuracy of 62%. The misclassification rates were 23% and 38%, respectively.

The ROC curves in Figure 11 provide a comparison of the performance of various object detection models on windowed and panorama image datasets. EfficientDet D1 (640 × 640) showed the highest performance on windowed images with an AUC of 0.97, but its performance dropped significantly on panorama images, with an AUC of 0.76, indicating potential limitations when dealing with broader image perspectives. Faster R-CNN ResNet50 V1 (640 × 640) displayed moderate and stable results, with an AUC of 0.85 for both windowed and panorama images, suggesting relatively uniform performance across these scenarios.

ROC curves for object detection models tested on windowed and panorama image datasets at a resolution of 640 × 640. The ROC AUC values indicate comparative performance, with SSD ResNet50 V1 FPN showing the highest consistency and performance across both image types. EfficientDet D1 demonstrates the best performance on windowed images but experiences a notable decline on panorama images. ROC, receiver operating characteristic; AUC, area under the ROC curve.

Overall, the analysis indicates that while most models performed better with windowed images, there are notable variations in robustness and adaptability among them. The SSD ResNet50 V1 FPN model’s high and consistent AUC across image types positions it as the most versatile model for applications requiring reliable detection across varied visual fields.

The system integration was tested during a practical demonstration to achieve Technology Readiness Level 6 (TRL 6), as defined by Mankins (1995). The goal of field tests was to evaluate the proposed framework to recognise two separate combat vehicles (CV90 and BMP-2), as part of the Laykka AI module. To ensure realistic conditions, the test was conducted in a woodland area with minimal underbrush and challenging weather, including sub-zero temperatures and a thick layer of snow. The day of field testing was conducted at the end of the year. The objective of the field test was to validate the framework’s capability to differentiate between the two vehicles under various real-world (summer vs. winter) environmental conditions, distinct from those employed in the offline testing and model training phase.

During the tests, the Laykka AI module was programmed to identify both combat vehicles but to follow only the BMP-2 combat vehicle. If a CV90 was detected, the controller module was programmed to remain stationary. During the test, the CV90 was driven along the road while the Laykka AI module scanned the surroundings for targets. When the CV90 approached, the Laykka AI module identified it but correctly determined that it was not the intended target, continuing its detection process.

Subsequently, the BMP-2 approached, and the Laykka AI module accurately recognised it as the target, prompting the UGV to move towards it. The position coordinate of the BB around the target in the image guided the UGV’s movement towards the detected target. The UGV was manually halted via the command line as it closed in on the target. This procedure was repeated multiple times with multiple models to validate the system’s integration performance.

To assess the capabilities and limitations of the proposed framework, this section will delve into the insights gained from the results. This section will examine key observations from integrating the framework and Laykka AI module with the Laykka platform, focusing on model performance under various environmental and computational constraints. The discussion below revisits the three guiding research questions in light of the results and contextualises the significance of the findings. The discussion will then conclude by exploring potential enhancements for future iterations.

The real-world demonstration confirmed that the proposed framework, when integrated into the Laykka UGV, can successfully detect and classify targets in dynamic outdoor military environments using a single passive panoramic sensor. The resource constrained UGV correctly identified and followed the BMP-2 while ignoring the CV90, validating not only classification accuracy but also behaviour-specific autonomy. Despite the challenging outdoor environmental conditions, including snow and cluttered woodland terrain, the system demonstrated stable performance without reliance on active sensors.

No comparative quantitative performance metrics were recorded during the field test. This was due to the fact that not all models were deployed in the real-world demonstration. Initial offline and controlled environment tests showed that some models could not maintain an acceptable frame rate on the embedded hardware and struggled to consistently detect the target vehicle under winter outdoor conditions. Since reliability was critical during the live demonstration, we selected the least failure-prone option based on preliminary evaluations in the field, the Windowed configuration of Faster R-CNN ResNet50 V1, for deployment in the demonstration test. Nonetheless, these findings support the conclusion that single 360-degree passive vision-based autonomy is feasible for constrained military UGV deployments when coupled with carefully selected ML algorithms.

Among the evaluated configurations, the Windowed model architecture consistently outperformed the Panorama-based approach across multiple object sizes and models. EfficientDet D1 demonstrated the highest offline AP (AP = 0.567 on windowed images), particularly excelling with medium and large objects. However, it suffered notable drops in performance when applied to panoramic images (AUC = 0.76), emphasising the importance of preserving image resolution when using 360-degree vision.

This reinforces that panoramic compression leads to significant loss of fine-grained detail, lowering detection accuracy, especially for smaller or distant objects. By contrast, the windowed configuration preserves local resolution, improving detection robustness across varying object scales. This outcome substantiates the framework’s design decision to partition panoramic imagery into overlapping windows to maximise detection accuracy within the resolution and compute constraints of the UGV, if computation resources allow it.

Although EfficientDet D1 achieved the best offline accuracy, the Faster R-CNN ResNet50 V1 model delivered more stable performance in real-world tests. Its moderate but consistent accuracy was complemented by greater prediction stability and fewer FN in online tracking scenarios. This stability minimised the dependency on backup tracking modules, which proved critical for real-time execution on the Laykka platform.

The Faster R-CNN model’s region proposal mechanism enabled sustained target engagement even during partial occlusion or brief misclassification. It was able to maintain continuity of detection and motor control, thereby supporting uninterrupted autonomy. These findings suggest that while EfficientDet is optimal for offline use cases requiring precision, Faster R-CNN is more suitable for embedded real-time deployment in constrained environments. This emphasises the importance of improving small object detection capabilities, especially for applications requiring identification of smaller or partially obscured targets. EfficientDet D1 may be more suited for applications where precise, focused detection is critical and visual complexity is lower.

The study demonstrates that cost-effective, passive vision systems can be a viable alternative to complex sensor fusion architectures in military robotics. This is particularly relevant for stealth-critical or expendable UGV applications. While the results indicate that the panoramic configuration was not suitable for the presented object detection task, the possible use for the full panoramic view could be beneficial in applications focused on situational awareness, such as security or surveillance, where high resolution of individual objects is less critical but a larger view of environment is prioritised. However, for the task presented in this paper, a more localised approach was necessary, as preserving the resolution of the target was critical for accurate detection.

Furthermore, the exploration into the efficacy of sub-dividing panoramic images using a windowed configuration led to improved results, although the improvement was not significant. It is evident that even with this configuration, the inherent resolution limitations persist, indicating that a fundamental constraint lies in the resolution itself. Increasing the camera resolution could help with detecting more distant objects, but this would also introduce additional computational overhead across the system, potentially exceeding the UGV’s processing capacity. Given the poor performance in detecting distant objects, it is evident that for the Laykka AI module to achieve more accurate detection using this particular PICAM-360 camera model, the target must be positioned within a medium visual range of the camera. This proximity ensures that the target falls within the scope of a medium-sized object within the image frame.

From a military perspective, the successful integration of ML into low-power UGVs demonstrates that advanced autonomous capabilities can be achieved without resorting to computationally intensive architectures. This enables the development of intelligent loitering munitions or smart mine-like systems capable of detecting enemy assets, issuing alerts or initiating direct action, all while remaining difficult to detect or jam electronically due to their passive design. Furthermore, the use of lightweight and efficient ML models allows multiple AI modules to operate concurrently on a single UGV without overwhelming its onboard computational resources. This parallel processing capacity enhances the system’s adaptability, enabling it to carry out more complex mission profiles. While increasing system intelligence and responsiveness, these improvements inevitably raise the unit cost, but the resulting tactical advantage in terms of autonomy, survivability and operational flexibility could be potentially significant.

While the results present promising performance, some limitations were identified during the evaluation. The operational conditions were somewhat constrained, with limitations on both the testing location and time. It is important to note that while data augmentation can create an approximation of some environmental conditions, it may be difficult to fully recreate actual environmental conditions. Thus, the effectiveness of data augmentation should be evaluated in conjunction with real-world testing to ensure that the model is robust and effective in a variety of scenarios (Shorten and Khoshgoftaar 2019).

Furthermore, the dataset used for training and evaluation might not comprehensively cover the wide range of scenarios that the robot system could encounter such as urban combat environments and other types of tracked or wheeled vehicles. Section 4.1 described that during data collection, the BMP-2 tank was more frequently encountered, leading to a larger number of collected images of it. It is essential to note that this dataset imbalance could potentially affect the model’s performance, as the model is likely to be biased towards the class with a greater number of observations during training. However, because the images were gathered from a live scenario, this reflects real-world conditions where balanced data collection for each target is not always feasible. In this context, the overrepresentation of certain classes, such as the primary target vehicle, can be considered aligned with operational priorities, as accurate detection of these more critical or frequently encountered targets is more important in deployment scenarios. While class imbalance may introduce systematic bias, in this case it supports the intended application by emphasising the recognition of mission-relevant targets. Thus, the model’s ability to perform reliably under such biased conditions, where prior odds of encountering the overrepresented class are large, reinforces its robustness and adaptability for real-world military use.

Section 4.1 also highlighted that the annotated dataset is composed of different scenarios with varying environmental conditions, which were separated into training, validation and test sets. However, a limitation arises from the fact that, despite this separation, certain scenarios may share similarities due to location restrictions and allowed areas of use of armoured vehicles. This is because some of the images gathered were collected closely to each other at the several same locations and times, leading to images that are visually similar across various scenarios. This similarity between scenarios could introduce bias in model performance and may limit the model’s ability to generalise to entirely new environments. Although it managed to work in a completely new snowy environment as discussed in Section 4.1, incorporating data from additional locations, varying times and different environmental conditions could improve the model’s ability to generalise.

Future research endeavours could explore enhancing the system’s adaptability to highly varying weather conditions, lighting changes and diverse more challenging terrains. Moreover, fine-tuning the object detection specifically for combat vehicles could lead to even more accurate and efficient performance. Adding audio stereo sensors to the system could aid the system to recognise targets from afar or during the night based on vehicles specific emitted noise. This would be a necessary future direction for sensor fusion research using cost-effective sensors within the proposed framework.

In addition to the limitations already discussed, further studies are needed to determine the precise performance of the selected ML models operating under the computational constraints of the Laykka platform. This includes quantifying the system’s response within specific time windows, particularly as target speeds vary, to better understand latency and detection thresholds. Future work should aim to collect and report standardised performance metrics under these conditions to rigorously assess the system’s robustness and generalisability.

Additionally, future work will take into consideration the detection of various obstacles and their possible circumvention. The distance to the target becomes a trade-off that incorporates camera resolution, and quality when acquiring targets at significant distances using passive sensors such as 360-degree camera. Further experimentation is necessary for more dynamic and complex environments such as live combat exercises or chaotic environments to assess real-world feasibility. A practical test was conducted on a single scenario, which provided valuable insights but may not fully represent the range of conditions the system might encounter. Testing additional scenarios would likely offer a more comprehensive understanding of the system’s performance across diverse conditions, allowing for more robust evaluation and potential improvements.

To better validate the presented methods, a comparative analysis incorporating alternative approaches, such as Transformers-based detectors (Han et al. 2022), YOLO-models (Vijayakumar and Vairavasundaram 2024), and other Deep Learning-Based Methods, could be performed. These methods offer different trade-offs in terms of computational efficiency, detection accuracy and adaptability to real-world conditions. However, given the constraints of this study, focusing on real-world deployment within a resource-limited UGV platform, the selected models were chosen because they are well-documented in the literature and relatively easy to implement. This made them practical choices to implement quickly within the scope of the project. While other methods could provide advantages in certain situations – like higher precision through ensemble learning – these were not selected due to implementation complexity or resource demands. Future research could explore these approaches to further refine and benchmark the system’s capabilities in varied operational environments.

Taken together, the findings presented illustrate that low-power, passively sensed autonomous systems, when paired with well-selected ML models, can operate effectively in real-world military environment. The framework for a passive target detection demonstrated both functional reliability in the field and adaptability across model configurations, with trade-offs emerging between detection accuracy and computational efficiency. While challenges related to resolution limits, dataset imbalance and scenario generalisation remain, the study underscores that meaningful autonomy is achievable without reliance on sensor-fusion or expensive active sensors. These insights not only validate the core design choices of the proposed system but also point towards concrete paths for improvement, including sensor upgrades, model refinement and expanded environmental testing. The concluding section builds on these lessons to reflect on broader implications and outline priorities for future research.

This study presented a novel detecting framework that utilises a single 360-degree camera, leveraging fisheye imaging in autonomous systems through an ML-based approach. The framework was tested as part of the Laykka UGV platform, specifically tasked with detecting CV90 and BMP-2 combat vehicles in real-world field conditions. These field tests confirmed the system’s operational potential, achieving TRL 6 readiness and validating its applicability under varied environmental and lighting conditions. At the core, the detection framework allows either the windowed partitioning or panoramic method, and allows the system to focus on either localised scene regions or the full panoramic view, depending on situational demands.

Among the tested ML models, EfficientDet D1 in the windowed configuration demonstrated the highest detection accuracy with 0.97 IoU in offline tests, whereas Faster R-CNN ResNet50, also in the windowed configuration, proved more robust during dynamic online field deployment tests by maintaining a steady detection output enabled by its region proposal mechanism, despite some trade-offs in accuracy. The use of a single 360-degree passive camera significantly reduces hardware complexity and cost, eliminating the need for multi-camera synchronisation or active sensors such as LiDAR or radar. This cost-effective passive approach inherently improves system stealth and simplicity, critical features for expandable autonomous systems operating in contested or covert environments.

Looking ahead, future work should explore higher-resolution or multimodal sensor integration to increase recognition performance, particularly under occlusion or low-contrast conditions. Future trials in more complex terrains and adversarial scenarios should be conducted to further stress-test system resilience. The scalability to multi-platform configurations, such as heterogeneous swarms of UGVs or coordinated UAV-UGV teams, should also be examined to broaden deployment flexibility.

When observing beyond military ground vehicles, the framework has broader relevance to passive sensing applications across various domains, including drones, mobile surveillance units, environmental monitoring robots and infrastructure inspection. By enabling robust, real-time target detection using a compact and efficient vision-based system, this research advances the field of autonomous robotics with a generalisable and cost-effective sensing solution that could be applicable to military and civilian uses.