Structural Health Monitoring (SHM) has emerged as a critical approach for maintaining the integrity and reliability of engineering structures through continuous, real-time assessment. By enabling the early detection of damage and degradation, SHM facilitates condition-based maintenance strategies, thereby minimizing the likelihood of unexpected failures and enhancing operational safety and efficiency (de Sá Rodrigues, 2023). In contrast to conventional Non-Destructive Testing (NDT) techniques – which are typically conducted at fixed intervals and often require operational interruptions – SHM provides a significant advantage by offering uninterrupted monitoring without the need for downtime. This continuous capability leads to substantial reductions in both maintenance costs and system unavailability, making SHM particularly advantageous across a range of sectors, including aerospace (Ren et al., 2023a, 2023b), civil engineering (García-Macías & Ubertini, 2022; Mishra et al., 2022), wind turbines (Martinez-Luengo et al., 2016; Khazaee et al., 2022), and power generation (Steczek et al., 2017; Ahmad & Khan, 2018). Among SHM techniques, linear and nonlinear Lamb wave techniques have gained prominence, each providing unique benefits and addressing different aspects of structural assessment (Espinoza et al., 2018; Su et al., 2014).

Linear methods employ embedded piezoelectric lead zirconate titanate (PZT) transducers to generate and receive Lamb waves, detecting damage by comparing signals from a baseline (undamaged) state to the current (unknown) state (Giannakeas et al., 2023). The growing adoption of GWSHM methods is largely attributed to their capability to propagate guided waves over long distances with minimal attenuation and their high sensitivity to incipient structural changes. When Lamb waves encounter damage—such as cracks, delamination, or corrosion—they undergo scattering and attenuation, which can be exploited as diagnostic indicators of structural integrity. To enhance the reliability and accuracy of GWSHM, a variety of signal processing and interpretation algorithms have been developed. These include time-of-arrival (Tua et al., 2004; Kudela et al., 2008), time-reversal techniques (Ramadas et al., 2010; Kudela et al., 2015), and artificial intelligence (AI) (Liu & Zhang, 2019), which have been applied in SHM efforts. For instance, He et al. (2013) demonstrated a correlation between fatigue crack growth and signal-based damage indices—such as correlation coefficients and amplitude-phase shifts—in riveted lap joints. Similarly, Mardanshahi et al. (2020) proposed a hybrid framework that integrated linear wave propagation data with AI models for detecting and classifying matrix cracking in glass/epoxy composites. Using features such as wave velocity and amplitude ratios, their support vector machine (SVM) model achieved a classification accuracy of 91.7%, underscoring its potential for automated damage evaluation. Yue & Aliabadi (2020) further advanced system-level SHM design by introducing a hierarchical approach for detecting barely visible impact damage in composite airframe structures under uncertain operational conditions.

In contrast to linear methods, which rely on baseline comparisons and are often limited in detecting micro-scale damage, nonlinear Lamb wave techniques identify damage through the analysis of wave-induced nonlinearities. These nonlinear methods are primarily divided into two categories based on wave interaction characteristics: signal modulation techniques (cross-interaction) (Yeung & Ng, 2020; Sampath et al., 2022) and harmonic methods (self-interaction), which include subharmonic (Maruyama et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2017), second harmonic (Rauter et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2018), and third harmonic approaches (Zhao et al., 2022a, 2022b). Nonlinear guided waves exhibit enhanced sensitivity to micro-defects – such as incipient cracks and dislocation networks – that may not be detectable using conventional linear approaches. For example, Espinoza et al. (2018) compared linear and nonlinear resonant ultrasound spectroscopy methods for quantifying dislocation density in metallic samples, demonstrating that nonlinear approaches (e.g., SHG) offer 2–6 times higher sensitivity, with up to 62% greater signal change. Recent developments have also explored the integration of both linear and nonlinear wave features to improve damage characterization. Su et al. (2014) proposed a hybrid acousto-ultrasonic method that leverages the advantages of both approaches for fatigue crack monitoring. Their findings indicate that nonlinear features are more effective for detecting early-stage damage, while linear features offer better robustness against noise. The fusion of these features allows for comprehensive tracking of damage evolution from micro-crack initiation to macro-scale propagation. Additionally, Yun et al. (2021) provided a systematic comparison between linear and nonlinear Lamb wave methods, emphasizing the superior sensitivity of nonlinear techniques for early-stage defect detection without the need for baseline signals. Despite their promising capabilities, nonlinear Lamb wave methods face notable challenges, particularly their susceptibility to environmental variability—most significantly, temperature fluctuations. To address this, the present study systematically investigates the performance of the nonlinear guided wave method under progressive fatigue damage and varying temperature conditions. The main contributions of this work related to nonlinear ultrasonic guided wave SHM are as follows:

- (i)

This study explores the use of nonlinear ultrasonic parameters extracted from piezoelectric (PZT) transducers for in-service fatigue damage monitoring. The approach eliminates the need for baseline signals by leveraging the material’s nonlinear response to cyclic loading, offering a more practical solution for real-world applications.

- (ii)

A detailed investigation into the method’s sensitivity threshold is conducted, establishing the minimum detectable crack size during fatigue crack progression. This provides a quantitative benchmark for evaluating the method’s effectiveness in early-stage damage detection.

- (iii)

The influence of temperature variation on nonlinear parameter behavior is rigorously examined. The results highlight that, although the nonlinear method performs well in detecting progressive damage, its performance deteriorates at elevated temperatures due to increased parameter variability. This underscores the need for compensation strategies to enhance its robustness under environmental fluctuations and ensure consistent performance in field applications.

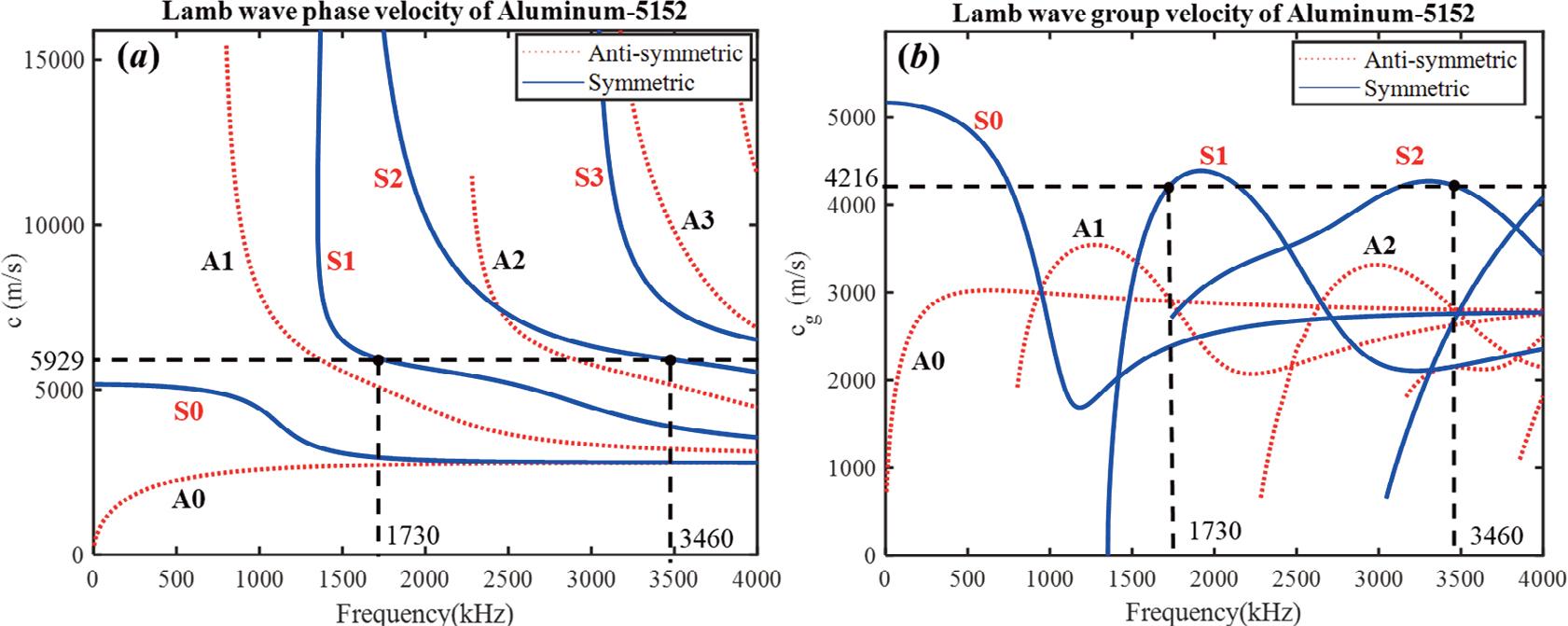

In nonlinear ultrasonic theory, the Lamb wave dispersion relation can be used to describe the propagation behaviour of the fundamental frequency (first harmonic) and the second harmonic generated through nonlinearity. Figure 1a shows two modes of phase velocity matching: the fundamental S1 mode and the third harmonic S2 mode. The corresponding frequencies are 1.73 MHz and 3.46 MHz respectively. From Figure 1b, it can be seen clearly that given the same frequency, the group velocity of the group velocity of the fundamental S1 mode and the third harmonic S2 mode is higher compared to other modes. Therefore, the fundamental S1 mode is the first wave packet signal (direct wave) in the response signal. At the same time, the two modes meet the requirement for group velocity matching. Consequently, the third harmonic S2 mode propagates at the same time as the fundamental S1 mode.

Dispersion curves of (a) phase velocity and (b) group velocity for Aluminum-5152 with 2 mm thickness.

In this research, the second harmonic parameter β′, calculated from the fundamental and second harmonic amplitudes, is proposed to analyze the frequency domain of the response, which is defined as:

Where A′1 represents the amplitude of the fundamental frequency obtained from the received signal, and A′2 is the amplitude of the second harmonic frequency components.

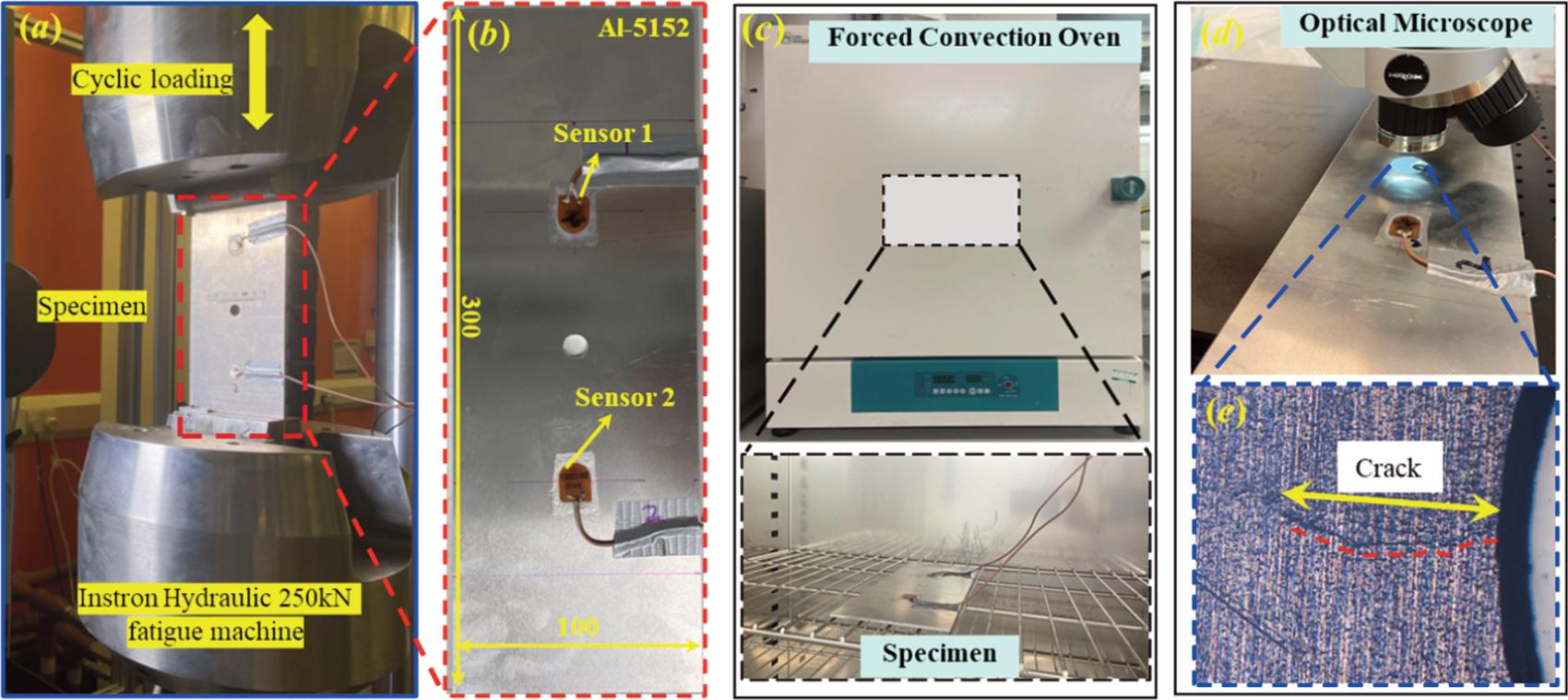

In the experiment, three Al-5152 plates (300 mm × 100 mm × 2 mm) cut from the same aluminium sheet were used. A 10 mm diameter circular hole was initially machined at the center of each plate. Two piezoelectric sensors (DuraAct, PI) were bonded to the plates using Hexcel Redux 312 epoxy-based film adhesive, as shown in Figure 2b. These PZT sensors are multifunctional, enabling passive vibration measurement as well as linear and nonlinear guided wave measurement without the need for additional power sources, thereby simplifying sensor deployment and reducing power consumption. The cyclic loading tests were conducted using an Instron hydraulic 250 kN fatigue machine, as shown in Figure 2a. The three specimens were labelled T1, T2, and T3. Cyclic uniaxial loading was applied with a maximum load of 15 kN (50% of the yield strength) and a minimum load of 1.5 kN, at a load ratio of 0.1 and a frequency of 10 Hz. In the early stages of the fatigue test, the loading was paused every 10,000 cycles. As the fatigue test progressed, the frequency of pausing was gradually reduced to capture more data on crack propagation. The plates were then removed and placed in a forced convection oven for nonlinear guided wave measurements, at varying temperatures between 20°C and 40°C, as shown in Figure 2c. After completing the measurements, crack initiation and propagation were observed using a Hirox 3D digital microscope, as illustrated in Figure 2d-e.

The experiment setup and facilities, (a) the fatigue machine to produce crack (b) the cracked Aluminium plate (c) The forced convection oven to control temperature (d) the optical microscope for the crack inspection.

Fatigue test details on different specimens under different temperatures.

| Stage of fatigue test | T1 | T2 | T3 | Working temperature |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0k | 0k | 0k | 20-40° |

| 2 | 100k | 100k | 100k | |

| 3 | 200k | 200k | 200k | |

| 4 | 300k | 300k | 300k | |

| 5 | 320k | 350k | 400k | |

| 6 | 340k | 370k | 420k | |

| 7 | 360k | 440k |

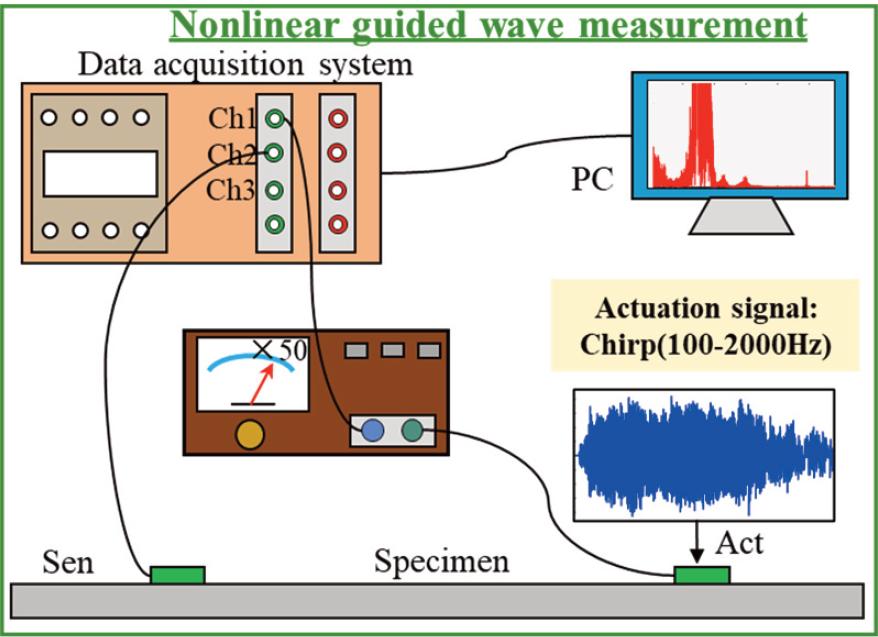

Four different tests were conducted intermittently during the fatigue experiment. For the linear guided-wave method, two PZT sensors were used simultaneously as both actuators and sensors. Guided waves were generated in the plate using broadband chirp excitation signals to efficiently capture responses across a range of frequencies. The nonlinear measurement system consisted of an arbitrary waveform generator (NI PXI-5412), an oscilloscope (NI PXI-5105), and an amplifier (TEGAM x50), as shown in Figure 3. A 1.73 MHz sine wave was generated by the PXI 5412 and applied to one sensor, while the response from the other sensor was recorded by the PXI 5105 oscilloscope, also with a 60 MHz sampling frequency, for 200 μs. The test was repeated five times to reduce the impact of environmental noise.

The signal acquisition system of the nonlinear guided wave-based method.

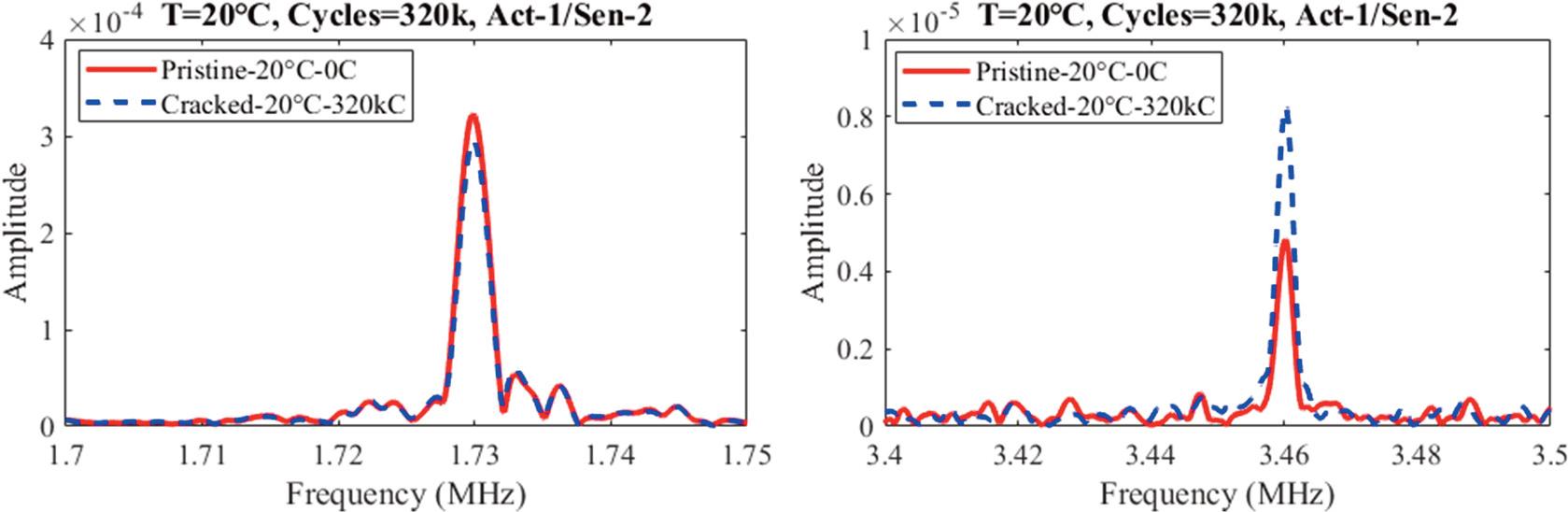

In nonlinear guided wave theory, the appearance of cracks leads to an enhancement of material local nonlinearity, which subsequently affects the frequency components of the guided wave. Specifically, the amplitude of the fundamental frequency decreases, while the amplitude of the second harmonic increases. The effect of the crack is summarised in Figure 4.

The amplitude of the (d) fundamental frequency and (e) second harmonic before the fatigue test and after 320k cycles.

The amplitudes of the fundamental and second harmonic frequency components under these two states are compared and summarized in Figure 4a and b. As shown in Figure 4d, the appearance of a crack results in an approximately 8.49% reduction in the amplitude of the fundamental frequency, along with a slight leftward shift in the corresponding frequency. In contrast, the second harmonic amplitude increased by 70.58% following crack initiation, indicating a redistribution of energy across different frequency components in the cracked region. This phenomenon arises primarily from the increased local nonlinearity of the material near the crack. As the crack propagates, the stress-strain relationship in the affected material becomes increasingly nonlinear, facilitating the generation of higher-order harmonics. Consequently, the increase in the second harmonic amplitude serves as a sensitive indicator of crack formation, effectively reflecting the nonlinear characteristics of the material and their influence on Lamb wave propagation. Current research on the influence of temperature on the nonlinear guided wave coefficient remains limited. However, existing studies indicate that the nonlinear guided wave coefficient increases with rising temperatures (Zhao et al., 2022c; Chillara et al., 2015). To further validate the effectiveness of nonlinear guided waves under varying temperature conditions, it is essential to investigate the specific impact of temperature on this coefficient.

The process also requires several input parameters, including maximum flight hours, time of interest (ToI), number of items analyzed per aircraft, hazard severity (specific to each SSPP), fleet size, operational factor (indicating whether failures are potential, such as loss of redundant component that does not result in total failure, or a crack that propagates circumferentially rather than longitudinally), and total fleet flight hours.

The second step is to calculate the probability density function (PDF) and cumulative density function (CDF). The failure rate curve is then derived to evaluate the influence of different inspection intervals using the equation (1) below. The cumulated failure rate from each aircraft yields the risk for the fleet.

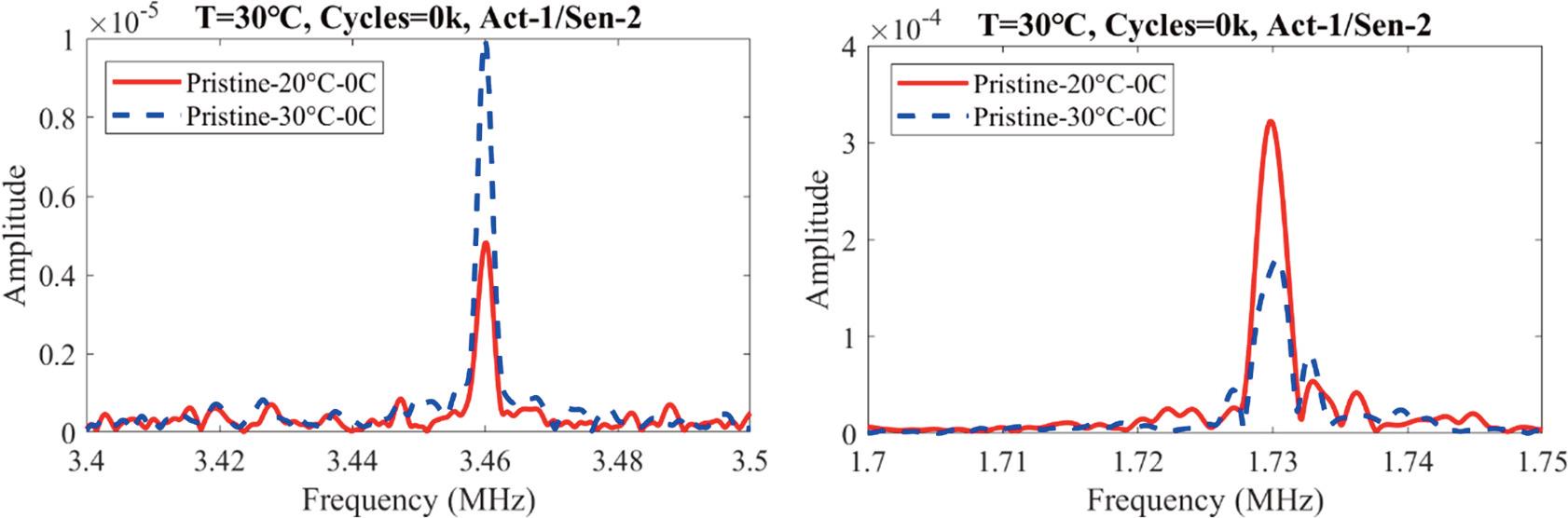

Figure 5 illustrates the effect of temperature on the amplitudes of both the fundamental frequency and the second harmonic. As the temperature increases from 20°C to 30°C, the amplitude of the fundamental frequency decreases by 44.16%, while the amplitude of the second harmonic significantly decreases by 107.1%. This phenomenon is attributed to temperature-induced changes in the material’s mechanical properties, such as elastic modulus and shear modulus, which influence the material’s nonlinear response and change the second harmonic parameter. With rising temperatures, the material softens or exhibits a more pronounced plastic deformation, enhancing its nonlinear behavior and consequently increasing the second harmonic parameter (Li & He, 2021). Since the effects of temperature and cracks on the nonlinear guided waves follow the same trend, the decrease in both the fundamental frequency and second harmonic amplitudes due to rising temperature is significantly greater than the impact of cracks. As a result, it becomes challenging to differentiate between the effects of damage and temperature on monitoring performance when using this method under varying temperature conditions.

The crack effect on the fundamental and second harmonic frequency.

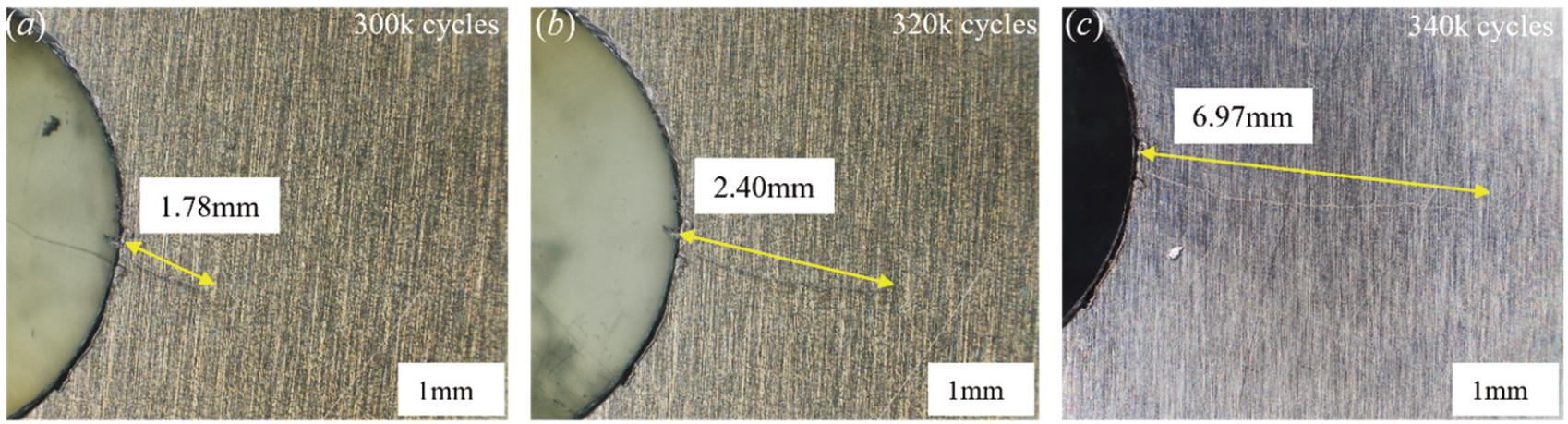

Optical microscope images of fatigue crack ar at: (a) 300k cycles, (b) 320k cycles, (c) 340k cycles.

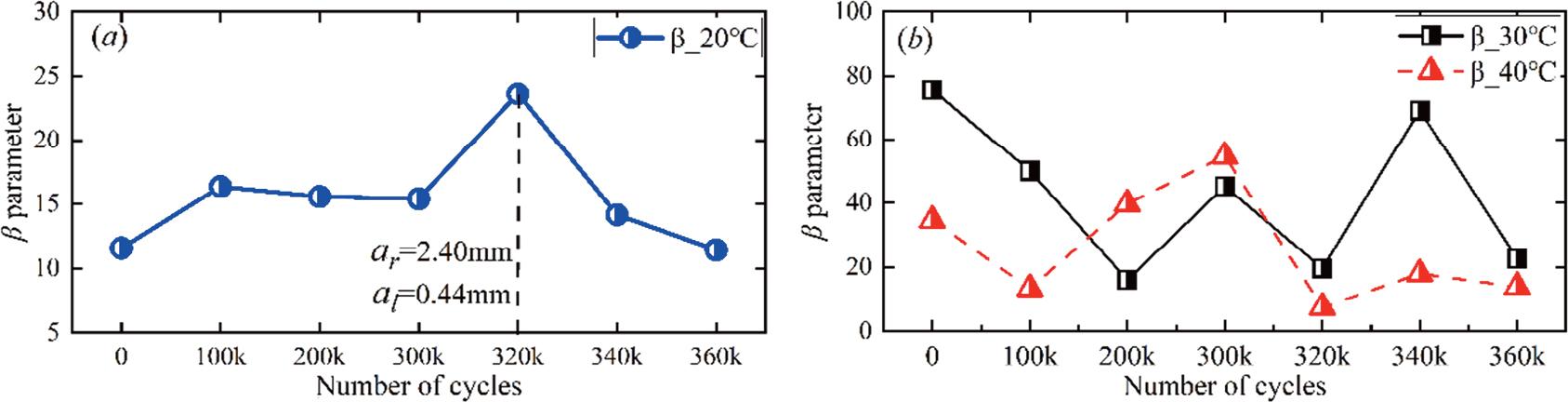

Based on Eqn. 1, the SH values under different loading cycles and temperatures were calculated, and the crack propagation at each stage was observed and recorded using the Hirox microscope. Specifically, the variations of SH values with loading cycles and temperature are summarized and presented in Figure 7.

(a) The second harmonic parameters versus fatigue cycles under 20° environments. (b) The second harmonic parameters versus fatigue cycles under 30° and 40° environments.

As shown in Figure 7a and Table 2, the β′ value obtained from T1 initially increases with the number of loading cycles and stabilises after 100k cycles. At 300k cycles, crack lengths measured using the Hirox microscope are 0.42 mm on the left side and 1.78 mm on the right side, yet the β′ value remains relatively unchanged. However, after 320k cycles, the β′ value experiences a sudden increase, corresponding to crack sizes of 0.44 mm on the left and 2.40 mm on the right. Subsequently, as the cracks continue to propagate, the β′ value gradually decreases. This sudden change in β′ is thus considered a potential indicator of crack detection during fatigue testing, aligning with findings reported in previous studies (Pan et al., 2025; Pan et al., 2025b). In contrast, Figure 7b shows that when the temperature increases to 30°C and 40°C, the β′ value exhibits irregular behaviour with the loading cycles. For instance, at 30°C, the β′ value initially decreases with increasing cycles, then increases, and continues to oscillate unpredictably. These findings highlight the necessity for the SH method to account for temperature effects to ensure consistent and reliable testing conditions. The results of β′ value changes with loading cycles for the other two specimens are presented in Figure 8.

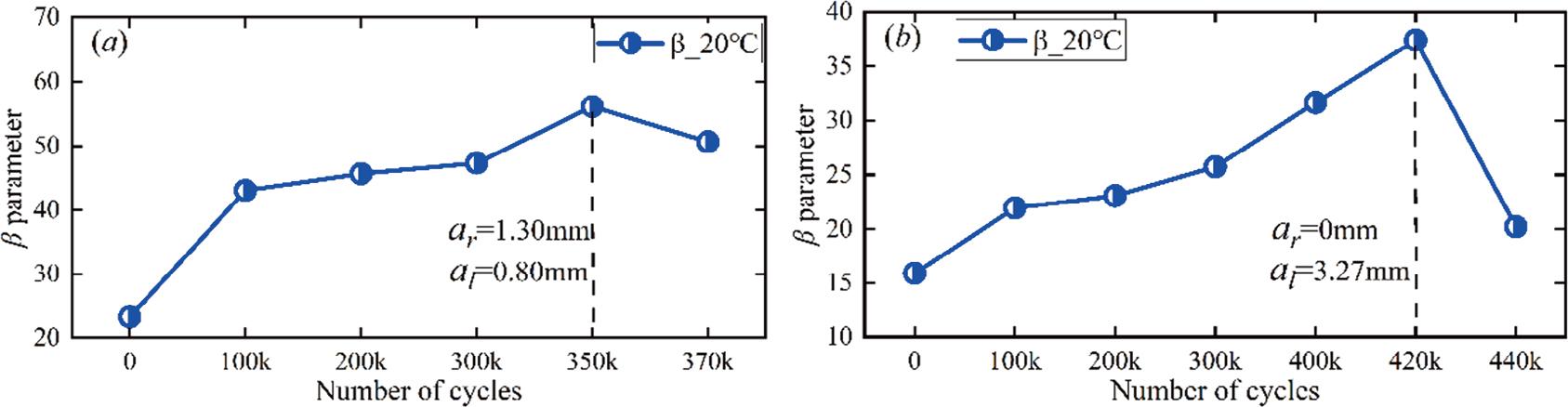

(a) The second harmonic parameters versus fatigue cycles were obtained by specimens (a) T2, and (b)T3.

Crack length of different fatigue stage on specimens T1, T2, and T3.

| Specimens | T1(mm) | T2(mm) | T3(mm) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Num of stage | cycles | al | ar | cycles | al | ar | cycles | al | ar |

| 1 | 0k | 0 | 0 | 0k | 0 | 0 | 0k | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 100k | 0 | 0 | 100k | 0 | 0 | 100k | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 200k | 0 | 0 | 200k | 0 | 0 | 200k | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 300k | 0.42 | 1.78 | 300k | 0 | 0 | 300k | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 320k | 0.44 | 2.4 | 350k | 0.8 | 1.3 | 400k | 0.6 | 0 |

| 6 | 340k | 2.11 | 6.97 | 370k | 1.93 | 3.90 | 420k | 3.27 | 0 |

| 7 | 360k | 4.05 | 11.4 | 440k | 6.71 | 1.4 | |||

As shown in Figure 8, the β′ value exhibits a similar trend with the number of loading cycles on the other two specimens T2 and T3, with the maximum β′ values corresponding to crack lengths of 2.1 mm and 3.27 mm, respectively. This further confirms that, under consistent temperature conditions, the SH method can effectively detect cracks around 3 mm in size.

The nonlinear Lamb wave method presents a promising baseline-free approach for online fatigue crack detection and growth characterization. By extracting the nonlinear parameter β′, which reflects the material’s nonlinear response under cyclic loading, this method enables the identification of crack initiation and evolution without the need for baseline signals from undamaged states. This advantage significantly enhances its applicability in practical, in-service environments where baseline acquisition is often unfeasible. Experimental results demonstrate that the method can detect cracks as small as approximately 3 mm, with β′ exhibiting a distinct and sudden increase corresponding to early-stage damage. However, despite its baseline independence, the method’s performance is notably sensitive to environmental variations-particularly temperature changes. At elevated temperatures, the response of β′ becomes irregular, which introduces uncertainty into both crack detection and growth modeling. This temperature sensitivity limits its reliability in fluctuating environments and underscores the need for future work on robust compensation techniques or temperature-insensitive feature extraction. Potential solutions may include temperature-normalized nonlinear indices or integrated thermal monitoring strategies to improve the consistency of β′ under variable operational conditions.

In summary, the nonlinear Lamb wave method strikes a balance between practical deployment and sensitivity to early damage, making it well-suited for applications where baseline data are unavailable and moderate environmental stability can be ensured. With further refinement to address temperature effects, this approach holds strong potential for integration into real-time structural health monitoring systems, particularly in aerospace, mechanical, and civil infrastructure domains.