English-speaking proficiency requires self-confidence and the ability to manage anxiety related to FNE in classroom settings (Mridha and Muniruzzaman 2020). As English becomes a primary medium of instruction worldwide, particularly in academic and professional settings (Rao 2019), developing strong speaking skills is essential for students’ success. However, one of the greatest barriers to proficiency in English speaking is Foreign Language Anxiety (FLA), particularly FNE, which hinders learners’ participation and engagement (Agata et al. 2019; Alnahidh and Altalhab 2020). Learners with high levels of FNE are often reluctant to speak in class due to fear of making mistakes and negative evaluation (Al-Khotaba et al. 2020).

LLS are essential tools that help students overcome anxiety and improve their speaking skills. LLS, including cognitive, metacognitive, and affective strategies, empower learners to take control of their learning and reduce FLA (Mohammadi et al. 2013; Ramdhani 2021). Integrating these strategies into language learning can lead to better language performance, increased confidence, and reduced anxiety (Oflaz 2019). Moreover, the rise of Mobile-Assisted Language Learning (MALL) offers a promising platform to enhance LLS use by allowing learners to practice English in flexible, technology-mediated environments (Khan et al. 2024). MALL has proven effective in reducing language anxiety and promoting independent learning (Chen 2024; Kukulska-Hulme and Traxler 2005).

Among various mobile applications, Telegram provides unique opportunities for enhancing EFL (English as a Foreign Language) learning. Its features, such as voice messaging, feedback tools, and language-learning bots, allow students to practice speaking and receive immediate, non-judgmental feedback (Abu-Ayfah 2020; Khan et al. 2024). Telegram also enables asynchronous communication, which reduces the pressure of face-to-face evaluations and encourages more active participation (Alahmad 2020). This has made Telegram an ideal tool for supporting EFL learners in overcoming FNE and improving their speaking skills.

In Saudi Arabia, preparatory-year EFL students often struggle with both speaking proficiency and the confidence to participate actively in English (Alnahidh and Altalhab 2020). High levels of FNE lead to behaviors such as shyness and avoidance of speaking opportunities, ultimately affecting their performance. Despite this, there is limited research on how technology-mediated LLS, such as those facilitated by Telegram, can mitigate FNE in EFL learners, particularly in Saudi contexts.

This study aims to fill this gap by investigating how Telegram-mediated LLS can reduce FNE and enhance speaking proficiency among Saudi undergraduates in the preparatory year. The study will examine the specific LLS employed by learners through Telegram and explore how these strategies help alleviate anxiety and promote effective communication in English.

The study attempted to answer the following questions:

-

To what extent does the use of Telegram mediated LLS reduce Saudi undergraduates’ FNE in the EFL speaking context?

-

What LLS are used by Saudi undergraduates to reduce their FNE in the EFL speaking context?

-

How does Telegram assist in the use of LLS that reduced Saudi undergraduates’ learner anxiety in FNE in EFL speaking context?

Speaking is undeniably a crucial skill that students must master in the language learning process, and it is often considered one of the most challenging skills to acquire since it needs extensive practice and a strong commitment to reach high performance (Masuram and Sripada 2020). Nunan (1991) defines speaking as “the ability to express oneself in the situation, or the activity to report acts, or situation in precise words or the ability to converse or to express a sequence of ideas fluently” (p. 23). According to Abdullaev and Qizi (2021), speaking is an interactive process involving the production of meaning through multiple stages, including the creation, reception, and processing of information. Speaking cannot be restricted by topics, materials, location, time, or other factors; thus, students must be attentive and apply and make use of the situations in which they find themselves.

Speaking is significant since it is a skill that enables others to understand what is being communicated simply. In contrast to reading or writing, speaking English demands the simultaneous application of a wide range of abilities, which are developed at various paces. EFL speaking in the Saudi context is problematic, students’ oral communication skills are anticipated to be excellent since, after studying English for many years, they will participate in a variety of English classes that require excellent abilities to communicate orally in English (Al-khresheh 2024). However, university students’ speaking abilities are, in fact, still quite low, and it is challenging to achieve speaking proficiency.

LLS have been a central focus of second language acquisition research since the 1970s (Rubin 1975). They refer to the deliberate actions learners take to improve their language learning process. Oxford (1990) defines them as “specific actions taken by the learner to make learning easier, faster, more enjoyable, more self-directed, more effective, and more transferable to new situations” (p. 8). This definition highlights the role of LLS in promoting learner autonomy, proficiency, and confidence. LLS are particularly valuable in the EFL speaking context, where many learners struggle with anxiety, lack of confidence, and limited opportunities for practice. Research demonstrates that by employing appropriate strategies, learners can directly counter these issues, enhancing their oral communication skills while reducing the fear of negative evaluation (Mohammadi et al. 2013; Wu 2010). By consciously applying strategies, learners gain more control over their language use, which in turn supports greater willingness to communicate in the classroom.

Oxford’s (1990) widely adopted taxonomy groups LLS into two broad categories: direct strategies and indirect strategies. Direct strategies such as cognitive, memory and compensation strategies are applied to the language itself. They involve practicing, analyzing, reasoning, recalling, and compensating for gaps in knowledge. Indirect strategies – metacognitive, affective, and social – support the learning process by helping learners plan, monitor, regulate emotions, and collaborate with peers. Together, these strategies provide learners with a toolkit for managing both the cognitive and emotional demands of speaking in a foreign language.

Evidence suggests that metacognitive and social strategies are especially effective in reducing speaking anxiety, as they allow learners to set goals, monitor progress, and seek support from peers (Fei 2019; Mohammadi et al. 2013). Cognitive strategies, such as imitation and repetition, further reinforce speaking fluency, while affective strategies help learners regulate emotions during performance tasks. Although learners may vary in their preference for particular strategies depending on cultural and educational contexts, studies consistently report that greater use of LLS is associated with lower anxiety and improved speaking outcomes (Khaliq et al. 2021; Noormohamadi 2009). LLS are essential for EFL learners aiming to develop oral proficiency and overcome barriers such as fear of negative evaluation. Therefore, by explicitly equipping learners with metacognitive, affective, and social strategies, educators can create a more supportive environment that encourages risk-taking, reduces anxiety, and promotes communicative competence.

FNE is a core component of foreign language anxiety, characterized by a pervasive apprehension about others’ judgments, which leads to the avoidance of evaluative situations and the anticipation of negative feedback (Horwitz et al. 1986). In the context of language learning, FNE often stems from learners’ perceptions of their own proficiency as well as formal academic assessments. Worde (2003) describes it as the assumption that one will inevitably be judged negatively in performance situations. Because language classrooms are inherently evaluative, students frequently become sensitive to real or imagined criticism from teachers and peers. This sensitivity can trigger anxiety during tasks such as oral presentations or class discussions, leading many learners to avoid participation altogether (Horwitz et al. 1986). This fear also extends to real-life communicative contexts, such as interviews and public speaking, where anxiety similarly inhibits performance. Research highlights that FNE is commonly reinforced by peer and teacher monitoring (Mazidah 2020); highly anxious learners display acute sensitivity to evaluations from instructors, classmates, or even native speakers (Agata et al. 2019). Importantly, FNE reflects expectations of negative judgment rather than momentary emotions such as shyness (Toyama and Yamazaki 2018). Learners who perceive their peers as more proficient often report heightened anxiety and reduced confidence, which undermines their willingness to participate (Wardhani 2019). Additional triggers include inadequate preparation, a fear of making mistakes, and receiving corrective feedback or negative judgment from others (Isa et al. 2023). As a significant predictor of speaking anxiety, FNE negatively influences oral performance. Okyar (2023) notes that because language learning occurs in evaluative social environments, higher FNE amplifies speaking anxiety and obstructs communication. Empirical studies consistently show that learners with strong FNE are less willing to speak, more likely to withdraw from classroom interaction, and more vulnerable to reduced performance outcomes (Aral and Arli 2019; Downing et al. 2020). This manifests in specific avoidance behaviors, expectations of negative judgment, and heightened classroom anxiety (Azzahra and Fatimah 2023). Similarly, Putri et al. (2024) found that learners often trace their reluctance to speak directly to a fear of criticism or ridicule by peers.

The relationship between the use of LLS and FLA has been extensively studied, with consistent findings indicating a significant negative correlation between the two. Researchers argue that the frequent use of LLS, particularly metacognitive strategies, is associated with lower levels of anxiety in language learners. For instance, Mohammadi et al. (2013) found that learners who actively employ LLS experience less English Language Classroom Anxiety (ELCA) compared to those who use LLS less frequently. This suggests that LLS serve as a tool for managing anxiety, enabling learners to approach language learning with greater confidence. Among the various categories of LLS, metacognitive strategies were the most preferred, as they help learners plan, monitor, and evaluate their learning processes. On the other hand, affective strategies, which involve managing emotions, were the least utilized, possibly because anxious learners may struggle to regulate their emotions effectively. Thus, the evidence supports the argument that LLS play a crucial role in reducing FLA, particularly when learners are equipped with strategies that help them take control of their learning.

However, the relationship between LLS and FLA is not one-sided; it is also influenced by the level of anxiety learners experience. Fei (2019) demonstrated that learners with high levels of spoken English anxiety still use LLS, but their preferences vary. For example, anxious learners tend to rely on cognitive and compensation strategies to cope with their anxiety, such as guessing meanings or using synonyms during speaking tasks. This indicates that while anxiety may hinder language performance, learners actively employ LLS to mitigate its effects. Furthermore, Fei (2019) emphasized that LLS help reduce FNE, a major component of FLA, by encouraging learners to participate more actively in classroom activities. This suggests that LLS not only alleviate anxiety but also foster a more supportive learning environment where learners feel comfortable making mistakes and collaborating with peers. Therefore, it can be argued that LLS are a vital resource for anxious learners, enabling them to overcome their fears and engage more effectively in language learning.

Critics might argue that the effectiveness of LLS in reducing FLA depends on the cultural and educational context in which they are applied. For example, Khaliq et al. (2021) found that Pakistani students who regularly used LLS exhibited lower anxiety related to FNE, as they felt more comfortable speaking English in various situations. This finding aligns with Noormohamadi’s (2009) study, which revealed that less anxious learners used metacognitive and social strategies more frequently, while memory and affective strategies were used less often. These studies highlight that the preference for certain LLS may vary across contexts, but the overall trend remains consistent: reduced anxiety correlates with increased use of LLS. This supports the argument that LLS are universally beneficial for managing FLA, though their implementation may need to be tailored to specific cultural and educational settings.

The evidence overwhelmingly supports the argument that the use of LLS, particularly metacognitive and social strategies, significantly reduces FLA and enhances language learning outcomes. By empowering learners to take control of their learning processes and alleviating fears of negative evaluation, LLS create a more supportive and less stressful learning environment. While cultural and contextual factors may influence the specific strategies learners prefer, the consistent negative correlation between LLS use and FLA underscores the importance of integrating LLS into language teaching practices. Educators should prioritize teaching learners how to effectively use LLS, as this not only reduces anxiety but also fosters greater confidence and competence in language use, particularly in speaking contexts.

University learners frequently use social messaging applications such as Telegram, which has had a considerable impact on education in general and English language learning in particular (Cremades et al. 2021). Telegram provides instant messaging services that allow users to exchange texts, images, audio, video, and documents in real time, making it an accessible and versatile tool for both social and academic purposes (Khan et al. 2024). It has been recognized as a valuable platform for remote and virtual learning, enhancing teacher–student interaction and facilitating the sharing of learning materials (Abu-Ayfah 2020; Zarei 2023). Several features make Telegram suitable for educational use. The application supports large groups and channels, unlimited file sharing, and interactive functions such as voice and video messages. These features promote collaborative learning, enable teachers to provide immediate feedback, and allow students to practice language skills beyond the classroom (Aladsani 2021; Shabani and Rezaei 2023). Teachers and learners alike benefit from its flexibility: assignments, comments, assessments, and discussions can be exchanged anytime and anywhere, encouraging continuous learning and engagement (AlAwadhi and Dashti 2021; Khan et al. 2024).

Research indicates that Telegram enhances learners’ performance by fostering interaction, engagement, and collaboration. Alakrash et al. (2020) found that the platform increases students’ interest, supports vocabulary development, and enables learning from peers’ errors. Similarly, Alahmad (2020) and Ramamurthy et al. (2022) reported that Telegram supports speaking skills such as pronunciation and fluency, while also generating positive learner attitudes toward self-learning and classroom practice. Other studies highlight its effectiveness in improving different language skills, including writing (Alodwan 2021), reading (Al Momani 2020), speaking (Abu-Ayfah 2020), and listening (Wardhono and Spanos 2018).

Beyond skill development, Telegram also influences affective variables. Wahyuni (2018) and Citrawati et al. (2021) observed that the application creates engaging and supportive learning environments that reduce anxiety and encourage participation. Zhao et al. (2022) further demonstrated that Telegram significantly improved learners’ motivation and reduced anxiety in an experimental study with Iranian EFL learners. Similar findings were reported by Zarei et al. (2017) and Zheng et al. (2023), where learners expressed greater comfort in responding via Telegram and viewed the platform as an effective extension of classroom learning.

Despite these benefits, few studies have explored how Telegram can mediate LLS to reduce FNE in speaking contexts. This gap is particularly evident in the Saudi EFL context. Addressing this, the present study examines how Telegram-mediated LLS can support Saudi undergraduates in overcoming FNE during speaking tasks in preparatory year programs.

This quasi-experimental study investigates the use of LLS mediated by Telegram to reduce FNE in the EFL speaking context among undergraduates. The data collected through pre-and post-questionnaires and semi-structured interviews about the use of LLS in EFL speaking through Telegram to reduce FNE. The design utilized an intact class structure with purposive sampling, meaning that the participants were not randomly assigned to groups.

The sample consisted of two intact speaking classes in total of 70 level one EFL undergraduates: 35 in the experimental group and 35 in the control group enrolled in the Preparatory Year (first year) at Najran University in Saudi Arabia in the first semester 2024/2025. The sample of Preparatory Year students share a number of common characteristics. The students in the science stream at high school join the Preparatory Year (a two-semester program) in which students study English, communication, thinking, research, mathematics, and computer skills. They compete for the medical, engineering, computer science, and administrative science faculties. Table 1 shows the common features of the experimental group and control group.

Common features of the experimental group and control group.

| Qualities | Experimental group | Control group |

|---|---|---|

| Educational background | High school (science stream) | High school (science stream) |

| English language as a foreign language | 8 years at school | 8 years at school |

| Age | 18–20 | 18–20 |

| Gender | Male | Male |

| Nationality | Saudi Arabia | Saudi Arabia |

| Mother tongue | Arabic | Arabic |

| Use of smartphones | Yes | No |

| Level of study | First year: first semester | First year: first semester |

This study utilized purposive sampling in the quantitative and qualitative phases. According to Etikan et al. (2016, p. 2), purposive sampling is ‘the deliberate choice of a participant due to the qualities the participant possesses’ based on previous knowledge or experience. Purposive sampling is a qualitative research method used to deliberately select specific individuals or units for analysis rather than choosing them randomly. Also called judgmental or selective sampling, this approach ensures participants are chosen intentionally based on relevant criteria (Thomas 2022). In purposive sampling, the researcher intentionally chooses participants with specific characteristics or attributes that align with the study’s objectives (Campbell et al. 2020). Purposive sampling enables researchers to collect detailed data on particular topics or issues, offering valuable insights and a deeper understanding of the research question (Ames et al. 2019). Etikan et al. (2016) describe homogeneous purposive sampling as the deliberate selection of individuals from a specific subgroup for in-depth analysis. This method focuses on participants who share common characteristics, such as age, demographics, education level, and gender.

This non-random assignment introduces several potential threats to internal validity, which must be considered to provide a comprehensive understanding of the study’s findings.

-

Selection Bias: The use of purposive sampling, combined with intact classes, means that participants were not randomly assigned to groups. As a result, pre-existing differences between the experimental and control groups such as varying levels of FNE or prior exposure to English could have influenced the outcomes independently of the intervention. These baseline differences could pose a threat to the internal validity of the study’s conclusions.

-

Maturation: The time gap between the pre-test and post-test measurements may have allowed for natural changes in the participants, regardless of the intervention. Over time, students may have become more comfortable with the language and less anxious about speaking, which could have contributed to the observed changes in FNE, independent of the Telegram-mediated language learning strategies.

-

History: External factors, including events outside the scope of the intervention (e.g., other language-learning opportunities, shifts in the educational environment, or personal life changes), might have influenced the participants’ FNE levels. These factors could have affected the results, posing a potential threat to the internal validity of the study.

-

Testing Effect: The repeated administration of the FNE and LLS questionnaires could have led to improvements due to the familiarity with the tests themselves. Participants might have performed better on the post-test simply because they had become more accustomed to the test format, rather than as a direct result of the intervention. This effect could have artificially inflated the observed outcomes.

-

Instrumentation: Any inconsistencies in administering the questionnaires and interviews, as well as possible variations in the interpretation of results, could introduce measurement errors.

Purposive sampling introduces a limitation in the generalizability of the findings because it does not allow for random assignment, which could reduce the impact of pre-existing group differences. As a result, the study may not fully control for all variables that could influence the outcomes, such as students’ prior proficiency in English or their previous experience with mobile-assisted learning.

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the University’s Research Ethics Committee prior to the commencement of the program’s implementation. The approval process included the preparation and submission of necessary documents, such as the formal application that outlined the research methodology, data collection tools, and potential risks. The committee reviewed the study to ensure that it adhered to ethical standards and safeguarded participants’ rights. Upon addressing any modifications suggested by the committee, final approval was granted, confirming that the study complied with all relevant ethical guidelines. Participation in this study was entirely voluntary, and all participants were informed of their right to withdraw at any stage without any consequence. Before starting the study, participants were orally briefed on the research objectives, the purpose of their involvement, and the procedures they would be expected to follow. To ensure transparency and informed consent, all participants, both in the experimental and control groups, were provided with a participation statement document, which detailed the study’s purpose, procedures, potential risks, and the handling of data. In addition to the oral briefing, each participant was given two copies of the consent form: one to sign and return to the researcher, and the other to keep for their records. This process ensured that participants understood and agreed to the terms of the study before their involvement. To protect anonymity, participants were identified by pseudonyms throughout the research, ensuring that their identities remained confidential. Additionally, confidentiality was strictly maintained by securing all data, including voice recordings and interview transcripts, in password-protected files. Only the research team had access to the data, and all information was handled in accordance with data protection regulations.

Finally, the research adhered to the ethical principle of beneficence, ensuring that the study did not cause harm to participants, and that the data collected would be used solely for research purposes. These steps were implemented to guarantee that both anonymity and confidentiality were preserved throughout the study, addressing the ethical concerns of the participants while maintaining the integrity of the research process.

Several important steps were carried out before the training program began. These included introducing the participants to the objectives of the program and study, providing a detailed explanation of the training content, and defining its role in reducing their anxiety in fear of negative evaluation after taking the training program. Necessary approvals were also obtained from the Research Ethics Committee to ensure adherence to ethical standards throughout the study. In addition, pre-questionnaires (LLS and FNE) were applied to evaluate participants’ level in fear of negative evaluation and the strategies used before the training began.

In the experimental group, the participants were subjected to a training session designed to help them correctly use LLSs mediated through the smartphone application Telegram. A qualified teacher conducted the training program for the experimental group from listening and speaking course in the second semester in the English department at Preparatory year college for over 10 sessions on how to employ LSLS through Telegram in relation to the textbook NorthStar 1: Listening and Speaking (3rd Edition) (GCC) (Solo’rzano and Schmidt 2009). In these sessions, the participants received training on the LLS: memory strategies, cognitive strategies, compensation strategies, metacognitive strategies, and affective strategies by Oxford (1990). For example, in memory strategies, students were given a list of words (advice, afraid to, came up to, completely, creative, employees etc.) and then instructed to practice these words by repeating them to oneself mentally several times. Students were also requested to use their Telegram to practice words by sending them as a voice messages in the group. After conducting the program, post-questionnaires (LLS and FNE) and semi-structured interviews were applied to evaluate participants’ level in fear of negative evaluation and the strategies used.

The instruments used for this study are a LLS questionnaire, a FNE questionnaire, and a semi-structured interview. A questionnaire prior to the intervention was administered in the first week to the experimental and control group, and then the strategy use intervention program was implemented to the experimental group for 12 weeks. Following the intervention program, the post questionnaire was administered to the experimental and control group whereas a semi-structured interview was administered to the experimental group. The questionnaire was distributed as a hard copy to the control group and experimental group inside the classroom with the help of the teacher. The questionnaire consisted of two domains. The first domain included an adapted version of Oxford’s (1990) Strategy Inventory of Language Learning (SILL) version 7.0. which is a 5-point Likert-scale questionnaire containing multiple-choice statements and ratings where 1 = Never, 2 = Rarely, 3 = Sometimes, 4 = Often, and 5 = Always. The adapted version of LLS consisted of 45 items which were divided into six sections: 1) Memory Strategies (8 items), 2) Cognitive Strategies (13 items), 3) Compensation Strategies (5 items), 4) Metacognitive Strategies (8 items), 5) Affective Strategies (6 items), and 6) Social Strategies (5 items) totaling 45 items. The adaptation ensured that the questionnaire was relevant to the research focus on speaking strategies, as the study aimed to investigate their impact on fear of negative evaluation. The questionnaire was tailored specifically to assess strategies used in the EFL speaking context. Additionally, modifications were made to ensure contextual relevance by aligning the items with the use of smartphone-based learning strategies via Telegram. This adaptation involved rewording some items to reflect the study’s emphasis on fear of negative evaluation , while irrelevant items were removed to enhance clarity and direct applicability. All items were revised, and some items were removed that are not related to speaking. Item no. 7 form memory strategies, item no. 20 and 23 form cognitive strategies, item no. 27 form compensation strategies, item no. 33 form metacognitive strategies, and item no. 50 form social strategies. Additionally, a pilot study was carried out to examine the LLS and FNE questionnaires. The LLS and FNE questionnaires and the speaking test were administered to an additional sample of 30 male Saudi students other than those who participated in the study. The students, ages 18 to 20, were enrolled in the Preparatory Year (first year) in the first semester. The pilot study was carried out in the preparatory year speaking classes. The reliability coefficient, Cronbach’s Alpha, was used to analyze the questionnaire results. The findings from this study prompted several revisions to improve the clarity and relevance of the items. These changes were incorporated into the final version of the instruments, ensuring that both the SILL and FNE are valid and reliable for use with the target group. Cronbach’s Alpha was employed to check the internal consistency of the questionnaire. The overall internal reliability of FNE was 0.94 while overall internal reliability of SILL was 0.93 which is an excellent degree of reliability. The questionnaires were distributed after its reliability.

The second questionnaire included FNE that consisted of 9 statements that were adapted from the Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Scale (FLCAS) created by Horwitz et al. (1986) and 7 (10–16) additional statements were added that are related to the fear of negative evaluation suggested by the experts reviewers. The questionnaire was administered in order to check the level of in FNE in the context of EFL speaking. Each item was rated on a five-point Likert scale by the participants, ranging from strong disagreement to strong agreement: 1 = Strong Disagreement; 2 = Disagree; 3 = Neither Agree Nor Disagree; 4 = Agree; and 5 = Strong Agreement. The adaptation of the SILL and FLCAS instruments was conducted with thorough attention to detail. The translation and back-translation process was carefully carried out by two bilingual experts, each possessing specialized expertise in the relevant languages and extensive experience in the field of applied linguistics and translation. The first expert performed the initial translation, followed by a back-translation conducted by a second, independent expertise. This dual-step process ensured the accuracy and consistency of the instruments, preserving the original meaning while adapting them to the target language. This process helped identify any discrepancies in meaning or potential loss of nuance during translation. Items with significant differences in the back-translation were revised to ensure that the Arabic version accurately reflected the original intent and meaning of each item. Cultural adaptation was also a crucial aspect of this process, with particular attention given to ensuring that the items were culturally relevant and appropriate for the target sample. Any items found to be culturally inappropriate or irrelevant were carefully removed, while others were retained after a rigorous review of their cultural fit.

The semi-structured interview’s questions were created by the researcher, and then they were checked for validity. Semi-structured interviews were conducted after the intervention program to gather detailed insights into students’ use of the Telegram app for EFL speaking and LLS. The students were asked the following questions: “How do you use Telegram to reduce your fear of negative evaluation?”, “Have you participated in Telegram speaking discussion activities? If so, how did they affect your confidence? “Which Telegram features help you feel more comfortable speaking English? “Do the constructive feedback in Telegram groups helps reduce the fear of judgment or criticism? These interviews, preferred for their flexibility and ability to yield accurate, comparable data (Cohen and Crabtree 2006), allowed researchers to prepare questions in advance while giving interviewees the freedom to express their views. Theoretical thematic analysis focuses on the researcher’s interest in exploring data within a particular field, offering valuable and detailed data into a specific area of study. Braun and Clarke (2006) detailed a thematic analysis framework consisting of six steps. The semi-structured interview was conducted in English with Arabic translations when needed the interviews involved 12 voluntarily participating students and lasted 15–20 min each. Participants, selected based on their questionnaire responses, were individually interviewed in the researcher’s office. The interviews were recorded with consent, transcribed, and analyzed thematically to explore Telegram’s role in reducing anxiety in fear of negative evaluation.

The following Table 2 is adopted from Braun and Clarke (2006, p. 87) explains each phase.

Braun and Clarke’s (2006) thematic analysis (Adopted).

| Phase | Description of the process |

|---|---|

| 1. Familiarising yourself with your data | Transcribing data (if necessary), reading and re-reading the data, noting down initial ideas. |

| 2. Generating initial codes | Coding interesting features of the data in a systematic fashion across the entire data set, collating data relevant to each code. |

| 3. Searching for themes | Collating codes into potential themes, gathering all data relevant to each potential theme. |

| 4. Reviewing themes | Checking in the themes work in relation to the coded extracts (Level 1) and the entire data set (Level 2), generating a thematic ‘map’ of the analysis. |

| 5. Defining and naming themes | Ongoing analysis to refine the specifics of each theme, and the overall story the analysis tells; generating clear definitions and names for each theme. |

| 6. Producing the report | The final opportunity for analysis. Selection of vivid, compelling extract examples, final analysis of selected extracts, relating back of the analysis to the research question and literature, producing a scholarly report of the analysis. |

In this study, content analysis was performed manually without the use of software to process the data collected from the semi-structured interviews to answer the fourth research question concerning the participants’ usage of Telegram in order to reduce fear of negative evaluation.

To analyze data for the current study, the researcher followed the iterative data analysis, First, reading the whole transcribed interview responses multiple times, and notes were taken on recurring patterns. Second, systematic coding was conducted by highlighting key features of the data relevant to the research focus. Third, codes were grouped into potential themes based on common patterns across the dataset. Forth, themes were reviewed at two levels to ensure accuracy and relevance. Fifth, each theme was clearly defined to highlight its role in addressing the research question. Finally, the report is created by selecting impactful extracts, conducting the final analysis, and connecting the findings to the research questions.

The study tools were applied to a sample of 30 respondents from outside of the main study, and Pearson Correlation method was used to validate the items’ grouping in relation to LLS. Table 3 shows Pearson Correlation coefficients of the LLS questionnaire.

Pearson correlation of LLS questionnaire.

| No. | Items | Pearson correlation | Sig. (2-tailed) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Memory strategies | 1 | 0.939** | |

| 1 | I think of relationships between what I already know and new things I learn in English. | 0.879** | 0.772** |

| 2 | I use new English words in a sentence so I can remember them. | 0.727** | 0.641** |

| 3 | I connect the sound of a new word and an actual or mental picture of the word to help me remember the word. | 0.440* | 0.699** |

| 4 | I link the sound of new words to help me remember the word. | 0.834** | 0.782** |

| 5 | I use rhymes to remember new words with familiar words or sounds from either English or any language. | 0.834** | 0.811** |

| 6 | I use notes to remember new words. | 0.780** | 0.794** |

| 7 | I review speaking lessons often. | 0.706** | 0.866** |

| 8 | I remember new words or phrases by remembering their location on the page, on the board, or on a street sign. | 0.631** | 0.463* |

| Cognitive strategies | 1 | 0.960** | |

| 9 | I say or listen to new words several times. | 0.845** | 0.805** |

| 10 | I try to talk like native English speakers | 0.725** | 0.793** |

| 11 | I practice the sounds of new English words. | 0.838** | 0.794** |

| 12 | Use the words I know in different ways. | 0.780** | 0.794** |

| 13 | I start conversations in English. | 0.852** | 0.766** |

| 14 | I watch English episodes or videos. | 0.689** | 0.638** |

| 15 | I use available dictionaries, word lists, and grammar exercises to understand what I listen in the new language and then produce conversation. | 0.806** | 0.793** |

| 16 | I speak for pleasure in English. | 0.927** | 0.830** |

| 17 | I compare new words in English with words in my Arabic language | 0.897** | 0.832** |

| 18 | I make use of grammar and vocabulary formation rules to get the meaning of new words in a spoken text. | 0.856** | 0.585** |

| 19 | I find the meaning of a new word by dividing it into parts that I understand. | 0.897** | 0.832** |

| 20 | I try to translate spoken text into my own language in order to understand the meaning. | 0.845** | 0.805** |

| 21 | I try not to translate word-for-word. | 0.709** | 0.589** |

| Compensation strategies | 1 | 0.952** | |

| 22 | To understand unfamiliar English words, I make inferences. | 0.758** | 0.763** |

| 23 | I make up new words if I don’t know the right words in English. | 0.857** | 0.813** |

| 24 | I try to guess what the other person will say next in English | 0.838** | 0.794** |

| 25 | To try to understand a spoken text without looking up every new word. | 0.927** | 0.830** |

| 26 | If I can’t think of an English word, I use a word or phrase that means the same thing. | 0.830** | 0.761** |

| Metacognitive strategies | 1 | 0.950** | |

| 27 | Try to find as many ways as I can to speak. | 0.845** | 0.805** |

| 28 | I notice my mistakes and use that information to help me do better in speaking in future. | 0.766** | 0.712** |

| 29 | I pay attention when someone is speaking English. | 0.845** | 0.805** |

| 30 | Have clear objectives and goals for improving my speaking skills. | 0.806** | 0.793** |

| 31 | Decide the purpose of speaking. | 0.897** | 0.832** |

| 32 | I look for people I can talk to in English. | 0.709** | 0.589** |

| 33 | I look for opportunities to speak as much as possible in English. | 0.714** | 0.606** |

| 34 | Assess my progress in learning speaking skills. | 0.856** | 0.585** |

| Affective strategies | 1 | 0.948** | |

| 35 | Reduce anxiety about learning speaking using relaxation, deep breathing, laughter, games, mediation, and music. | 0.695** | 0.687** |

| 36 | Encourage myself to speak English even when I am afraid of making a mistake. | 0.922** | 0.845** |

| 37 | I give myself a reward when I speak well in English. | 0.852** | 0.766** |

| 38 | Notice if I am tense or nervous when I speak. | 0.901** | 0.810** |

| 39 | Write down my feelings about learning speaking in a diary. | 0.725** | 0.793** |

| 40 | Talk to someone else about how I feel toward learning speaking. | 0.856** | 0.585** |

| Social strategies | 1 | 0.856** | |

| 41 | Ask the other person to slow down or say it again if I do not understand something in speaking. | 0.612** | 0.856** |

| 42 | Ask people whose English is better than mine to correct me when 1 speak. | 0.692** | 0.495* |

| 43 | Practice speaking English with other students. | 0.856** | 0.585** |

| 44 | Ask for help from good speakers of English when doing a speaking task. | 0.689** | 0.638** |

| 45 | Ask questions about speaking tasks. | 0.866** | 0.614** |

**Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). *Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

Table 2 shows that the Pearson correlation coefficients between the items and the total score of their respective strategy were statistically significant at the (0.01) and (0.05) significance levels. The Pearson correlation coefficients between the items and the total score of their respective strategy ranged between (0.440*–0.927**). Additionally, the Pearson correlation coefficients between the strategies and the total score of the questionnaire ranged between (0.856**–0.960**) and were statistically significant at the (0.01) significance level.

As for the FNE questionnaire. Pearson Correlation method was used to validate the items’ grouping in relation to FNE. Table 4 shows the factor analysis of the FNE questionnaire.

Pearson correlation of FNE questionnaire.

| No. | Item | Pearson correlation | Sig | No. | Item | Pearson correlation | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | I tremble when I know that I’m going to be called on in English class. | 0.501* | 0.024 | 9 | I get nervous when the English teacher asks questions which I haven’t prepared in advance. | 0.951** | 0.000 |

| 2 | I keep thinking that the other students are better at English than I am. | 0.726** | 0.000 | 10 | I am afraid that my English teacher is ready to correct every mistake I make. | 0.854** | 0.000 |

| 3 | It embarrasses me to volunteer answers in my English class. | 0.709** | 0.000 | 11 | I feel very shy about speaking English about speaking English in front of the other students. | 0.870** | 0.000 |

| 4 | I get upset when I don’t understand what the teacher is correcting | 0.503* | 0.024 | 12 | I am frequently afraid of other students noticing my shortcomings when I speak in English. | 0.694** | 0.001 |

| 5 | I can feel my heart pounding when I’m going to be called on in English class. | 0.600** | 0.005 | 13 | I worry about what kind of impression that other students are making on me. | 0.768** | 0.000 |

| 6 | I always feel that the other students speak the English language better than I do. | 0.616** | 0.004 | 14 | I am afraid that the students and the teacher will track my mistakes when I speak in English. | 0.921** | 0.000 |

| 7 | I start to panic when I have to speak without preparation in English class. | 0.870** | 0.000 | 15 | The opinion of the teacher and the students about me bothers me. | 0.834** | 0.000 |

| 8 | I am afraid that the other students in the class will laugh at me when I speak in English. | 0.746** | 0.000 | 16 | If I know that the teacher and the students are judging me, it has big effect on me. | 0.951** | 0.000 |

**Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). *Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

Table 4 shows that Pearson correlation coefficients between the items and the total score of the FNE Questionnaire were statistically significant at the (0.01) and (0.05) significance levels. The Pearson correlation coefficients between the items and the total score ranged from (0.501*–0.951**) with significance levels ranging from (0.00–0.024).

Table 5 shows the distribution of LLS items, and the Cronbach’s Alpha of the LLS questionnaire. It can be seen that the overall internal reliability was 0.93, an excellent degree.

Internal consistency of the LLS questionnaire.

| No. | Strategies | No. of items | Reliability-Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Memory strategies | 8 | 0.83 |

| 2 | Cognitive strategies | 13 | 0.91 |

| 3 | Compensation strategies | 5 | 0.78 |

| 4 | Metacognitive strategies | 8 | 0.80 |

| 5 | Affective strategies | 6 | 0.79 |

| 6 | Social strategies | 5 | 0.76 |

| 7 | Overall | 45 | 0.93 |

In addition, the Cronbach’s Alpha of the FNE questionnaire was calculated. The overall internal reliability was 0.94, an excellent degree of reliability.

As for the semi-structured interview, two methods were used to verify the semi-structured interview: a pilot study and an expert review. The researcher developed the semi-structured interview questions, which were then validated by three professors specializing in blended language learning and technology use in language learning. They were requested to review the semi-structured interview questions for clarity, relevance, and bias. One professor holds a Ph.D. and has been lecturing in applied linguistics at King Khalid University in Saudi Arabia for around 8 years. The other two experts are professors holding a Ph.D. in applied linguistics and foreign language acquisition at Najran University in Saudi Arabia, with more than 10 years of experience teaching English. Additionally, they have many publications in second or foreign language acquisition and mobile-assisted language learning (MALL). The questions of the interview were sent to the professors through e-mail. In addition, they were briefed about the study, and then the professors approved the general content of the interview questions to fulfil the research objectives. The experts suggested adding sub-questions “Do the constructive feedback in Telegram groups helps reduce the fear of judgment or criticism? How so?, and “Which Telegram features help you feel more comfortable speaking English?” to take more information about experience about using Telegram to reduce their fear of negative evaluation. After having validated the semi-structured interview, the researcher conducted a pilot study. Five students were asked to participate in the semi-structured interview in order to verify several aspects of it such as timing, location, technical aspects, and the clarity of its questions. The semi-structured interviews lasted 15–20 min each. The respondents reported feeling at ease in the researcher-teacher’s office and had no issues using the researcher’s smartphone recorder. They were able to understand the questions easily, but it was recommended to include some examples to clarify the points further.

The results provided insight into how the participants reportedly used LLS through Telegram to reduce their anxiety in FNE among Saudi EFL students enrolled in Preparatory Year Deanship at Najran University in Saudi Arabia in EFL speaking context.

Table 6 shows the descriptive data analysis of the participants’ level of foreign language classroom anxiety in FNE in an EFL speaking context in both the experimental group and control group ahead of the intervention program. The table displays means (M), standard deviation (SD), and the t-test for independent samples to illustrate the significance of the differences between the averages of the scores of the control and experimental groups on the scale of FNE in an EFL-speaking context.

Analysis of FNE questionnaire.

| Application | Group | N | Mean | Std. Deviation | t | df | Sig. (2-tailed) | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Control | 35 | 3.95 | 0.695 | 0.78 | 68 | 0.437 | 0.19 (small) |

| Experimental | 35 | 3.83 | 0.580 | |||||

| Post | Control | 35 | 3.50 | 0.711 | 11.83 | 68 | 0.000 | 2.82 (very large) |

| Experimental | 35 | 1.92 | 0.348 |

As shown in Table 6, at the pre-test stage, no significant differences were found between the experimental group (M = 3.83, SD = 0.58) and the control group (M = 3.95, SD = 0.70) on the overall FNE scale, t(68) = 0.78, p = 0.437, Cohen’s d = 0.19. This indicates that both groups experienced comparable levels of foreign language anxiety before the intervention, confirming their initial homogeneity.

In contrast, at the post-test stage, statistically significant differences emerged between the control group (M = 3.50, SD = 0.71) and the experimental group (M = 1.92, SD = 0.35), t(68) = 11.83, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 2.82. This very large effect size demonstrates that the experimental group experienced a substantial reduction in foreign language classroom anxiety following the implementation of the LLS intervention program through Telegram, whereas the control group, who were taught using traditional methods, showed comparatively higher levels of anxiety.

The comparison of pre- and post-test data highlights that Telegram-mediated LLS was highly effective in lowering FNE among Saudi EFL undergraduates.

Table 7 shows the descriptive data analysis of the participants’ use of language learning strategies LLS in an EFL speaking context in both the experimental group and control group ahead of the intervention program. Table 6 displays means (M), standard deviations (SD), and the t-test for independent samples to illustrate the significance of the differences between the averages of the scores of the control and experimental groups on the scale of LLS in an EFL-speaking context.

Analysis of LLS questionnaire.

| Strategy | Group | N | Mean | Std. Deviation | t | df | Sig. (2-tailed) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | |||||||

| Memory strategies | Control | 35 | 2.81 | 0.601 | −1.589 | 68 | 0.117 |

| Experimental | 35 | 3.07 | 0.741 | ||||

| Cognitive strategies | Control | 35 | 2.93 | 0.518 | 0.624 | 68 | 0.534 |

| Experimental | 35 | 2.86 | 0.469 | ||||

| Compensation strategies | Control | 35 | 3.02 | 0.684 | 1.252 | 68 | 0.215 |

| Experimental | 35 | 2.83 | 0.571 | ||||

| Metacognitive strategies | Control | 35 | 3.42 | 0.722 | 1.290 | 68 | 0.202 |

| Experimental | 35 | 3.21 | 0.623 | ||||

| Affective strategies | Control | 35 | 2.83 | 0.700 | 1.390 | 68 | 0.169 |

| Experimental | 35 | 2.61 | 0.613 | ||||

| Social strategies | Control | 35 | 3.22 | 0.709 | 1.664 | 68 | 0.101 |

| Experimental | 35 | 2.97 | 0.493 | ||||

| Total | Control | 35 | 3.00 | 0.465 | 1.065 | 68 | 0.291 |

| Experimental | 35 | 2.89 | 0.375 | ||||

| Post | |||||||

| Memory strategies | Control | 35 | 2.46 | 0.438 | −5.427 | 68 | 0.302 |

| Experimental | 35 | 3.29 | 0.796 | ||||

| Cognitive strategies | Control | 35 | 3.13 | 0.492 | −5.657 | 68 | 0.000 |

| Experimental | 35 | 3.83 | 0.546 | ||||

| Compensation strategies | Control | 35 | 3.22 | 0.580 | −2.847 | 68 | 0.005 |

| Experimental | 35 | 3.66 | 0.695 | ||||

| Metacognitive strategies | Control | 35 | 3.37 | 0.592 | −3.29 | 68 | 0.000 |

| Experimental | 35 | 3.83 | 0.573 | ||||

| Affective strategies | Control | 35 | 3.08 | 0.622 | −2.398 | 68 | 0.019 |

| Experimental | 35 | 3.48 | 0.762 | ||||

| Social strategies | Control | 35 | 3.46 | 0.587 | −3.055 | 68 | 0.121 |

| Experimental | 35 | 3.89 | 0.602 | ||||

| Total | Control | 35 | 3.68 | 0.570 | −3.677 | 68 | 0.166 |

| Experimental | 35 | 3.19 | 0.544 |

As shown in Table 7, it is clear that participants in both groups often use metacognitive strategies (M = 3.21, 3.42, SD = 0.722, 0.623), which ranked as the most frequently used strategy, followed by social strategies (M = 2.97, 3.22, SD = 0.493, 0.709), memory strategies (M = 3.07, 2.81, SD = 0.741, 0.601), compensation strategies (M = 2.83, 3.02, SD = 0.571, 0.684). Cognitive strategies (M = 2.86, 2.93, SD = 0.469, 0.518) and affective strategies (M = 2.61, 2.83, SD = 0.613, 7.00) ranked as the least often used strategies. That is to say, participants in both the experimental and control groups often use the smartphone application Telegram to employ LLS.

Moreover, before the intervention program both groups have extremely similar means among all items on the subscale whereas the experimental group used the Telegram app for language learning strategies in the speaking course, had a significantly higher use of LLS compared to the control group (M = 3.68, SD = 0.570): t(68)=3.677, p=0.000. Participants in the experimental group exceeded the control group in the use of both direct and indirect strategies. The highest mean difference was scored in social strategies (SS) (M = 3.89, SD = 0.602): t(68) = 3.055, p = 0.003. Memory strategies (MS), cognitive strategies (CS), metacognitive strategies (MSs), affective strategies (AS), and compensation strategies (CSs) had close significances (p = 0.320, 0.320, 0.140, 0.078, 0.108, respectively).

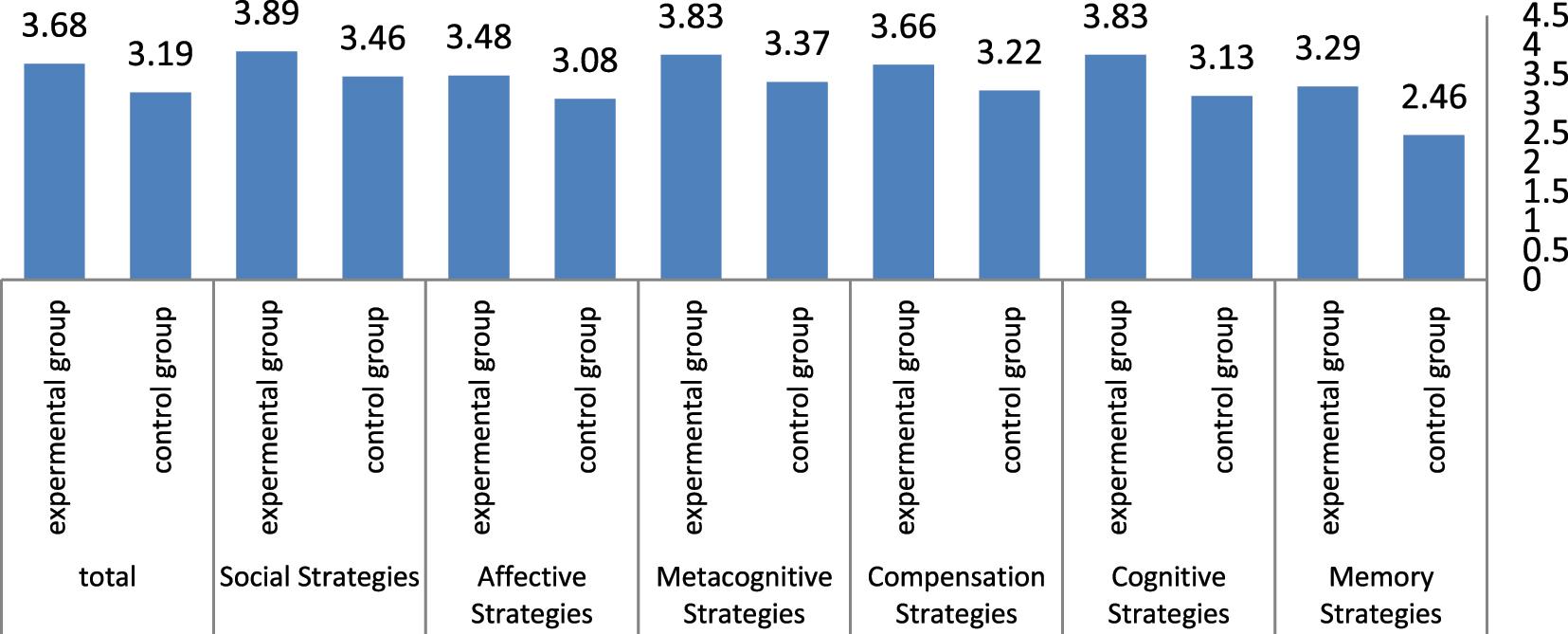

Table 7 shows that there are statistically considerable differences at the level of significance (0.05) between the means on the LLS scale for language learning through the smartphone application Telegram on the use of language learning strategies in an EFL speaking context by the participants after the intervention program conducted in favor of the experimental group (Figure 1).

Results of the use of LLS mediated by Telegram before and after the intervention.

In semi-structured interviews, participants shared their experiences using Telegram to apply LLS in an EFL-speaking classroom. All 12 participants agreed that Telegram helped in reducing their fear of negative evaluation. The following Table 8 demonstrates the thematic breakdown of semi-structured interviews.

Themataic breakdown of the semi-structured interview.

| Semi-structured interview questions | Themes | Codes | Interviewees’ responses |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. How do you use Telegram to reduce your fear of negative evaluation? | Reducing fear of negative evaluation | Use of voice messages for authentic conversation | “Well, I used voice messages… because, um, I felt like real conversations.” (SSI = 1) |

| Active participation in group discussions without fear of judgment | “Uh …I do not feel shy speaking English in the group.” (SSI = 9) | ||

| 2. Have you participated in Telegram speaking discussion activities? If so, how did they affect your confidence? | Building confidence through interaction | Peer support and feedback in discussions | “Telegram gave me opportunities to participate actively, um, without worrying about mistakes.” (SSI = 8) |

| Encouragement from peers to participate | “Well, I was encouraged to answer the questions, like, voluntarily. I wasn’t worried about, you know, correcting my mistakes.” (SSI = 2) | ||

| 3. Which Telegram features help you feel more comfortable speaking English? | Tools and features for comfort | Voice messages | “I used voice messages to express myself more freely without the fear of judgment.” (SSI = 11) |

| Dictionaries and translation tools for vocabulary and pronunciation | “I used an online dictionary to learn the pronunciation of new words before speaking.” (SSI = 6) | ||

| 4. Do the constructive feedback in Telegram groups help reduce the fear of judgment or criticism? | Reducing judgment fear through feedback | Constructive peer feedback in group discussions | “Feedback in Telegram helped me improve by pointing out small mistakes. It felt less harsh than in class.” (SSI = 5) |

| Instant and supportive feedback | “I always listen to responses to understand areas that need improvement… um.” (SSI = 11) |

The semi-structured interviews revealed that Telegram played a vital role in reducing fear of negative evaluation and boosting students’ confidence in speaking English. Features such as voice messages, group discussions, and peer feedback created a supportive and non-judgmental environment, encouraging active participation. For instance, one participant (SSI = 9) mentioned, “I do not feel shy speaking English in the group.” This highlights how the group feature provided a safe space for participation without the fear of immediate judgment. Another participant (SSI = 1) added, “I used voice messages… because, um, I felt like real conversations.” This demonstrates how voice messages allowed students to communicate more freely without the pressure of live interaction. Furthermore, students appreciated the instant feedback from peers, which helped build their confidence. One participant (SSI = 5) shared, “Feedback in Telegram helped me improve by pointing out small mistakes… It felt less harsh than in class.” Another (SSI = 11) explained, “I always listen to responses to understand areas that need improvement… um.” Features like dictionaries also helped improve vocabulary and pronunciation, making students feel more comfortable speaking. Overall, Telegram provided a flexible and supportive platform where students could practice, receive constructive feedback, and gain confidence in their speaking abilities without the pressure of face-to-face interaction.

The qualitative analysis, through thematic analysis, provided valuable insights into students’ use of Telegram to reduce Fear of Negative Evaluation. The coding process was rigorously conducted ensuring reliability. Thematic analysis revealed new insights into the mechanisms of peer support, constructive feedback, and comfort in speaking, offering a more detailed understanding of how Telegram’s features contribute to reducing anxiety and enhancing confidence in EFL learners. The platform’s features, such as voice messages, group chats, and feedback mechanisms, created a supportive and flexible learning environment. These features allowed students to engage in speaking activities without the anxiety typically associated with face-to-face communication. Moreover, Telegram supported individual learning needs, offering students the freedom to practice, self-assess, and review their progress in a less pressured setting, ultimately contributing to their speaking skill development.

The current study, within the specific context of this intervention, suggests that Telegram-mediated LLS substantially reduced learners’ levels of FNE in an EFL speaking context. The quantitative results clearly showed that, following the intervention, the experimental group’s FNE scores decreased markedly compared to the control group, whose FNE remained relatively high. This indicates that employing LLS through a supportive digital platform such as Telegram can provide a meaningful reduction in anxiety levels, offering a safer environment for EFL learners to practice speaking without fear of negative evaluation.

The intervention program also enhanced learners’ use of LLS in both direct and indirect strategies. Pre-intervention data indicated that both groups used strategies similarly, with metacognitive strategies being the most frequently employed, followed by social, memory, compensation, cognitive, and affective strategies. However, post-intervention findings demonstrated a clear shift, with social strategies emerging as the most frequently used, followed by cognitive, metacognitive, compensation, affective, and memory strategies. This suggests that Telegram’s interactive and collaborative features influenced learners’ strategy preferences, encouraging socially-oriented strategies over more individually-directed approaches such as metacognitive strategies.

The predominance of social strategies can be explained by the affordances of Telegram, which allows learners to interact with peers through group chats, voice messages, and instant feedback. These features created a non-judgmental, low-pressure environment, enabling learners to participate actively, seek peer support, and receive constructive feedback without fear of embarrassment. This result diverges from prior studies (Fei 2019; Mohammadi et al. 2013; Noormohamadi 2009), which reported metacognitive strategies as most frequently used, and Khaliq et al. (2021), who found affective strategies dominant. The difference highlights how digital platforms and the specific learning context can reshape learners’ strategic choices, suggesting that the choice of strategies is highly sensitive to the affordances of the learning environment and the learners’ cultural and social context.

Cognitive strategies, which ranked second in the post-intervention data, helped learners practice new expressions, imitate native speakers, and translate unfamiliar vocabulary. The high use of cognitive strategies aligns with Fei (2019), who reported them as secondary, but diverges from studies by Khaliq et al. (2021) and Noormohamadi (2009), where social strategies ranked second. Metacognitive strategies, ranked third, supported learners in planning, monitoring, and evaluating their language learning, allowing them to exert control over their progress. Compensation strategies ranked fourth, helping students manage knowledge gaps by creating new words, using their mother tongue, or asking peers for assistance.

Affective strategies, which ranked fifth, contributed to reducing anxiety and building learner confidence, consistent with Fei (2019), but divergent from Mohammadi et al. (2013) and Noormohamadi (2009), who reported memory strategies as fifth, and Khaliq et al. (2021), who reported cognitive strategies in this position. Finally, memory strategies were the least used, reflecting learners’ reduced reliance on rote memorization in a digital, interactive learning context. This aligns with the shift in instructional practices in many Arab educational contexts, moving away from didactic, rote-based methods towards more interactive, learner-centered approaches (Tamer 2013).

The results suggest a clear relationship between the use of LLS and reduced FNE. Learners who actively employed strategies reported feeling more confident when participating in speaking activities, better able to avoid errors, and more willing to engage with peers and teachers. This aligns with previous studies highlighting the role of LLS in mitigating language anxiety (Fei 2019; Ghafournia 2023; Khaliq et al. 2021; Mohammadi et al. 2013; Noormohamadi 2009; Oflaz 2019; Wu 2010). For instance, Wu (2010) asserted that students who apply a wider range of learning strategies are likely to experience less anxiety, while Fei (2019) and Oflaz (2019) emphasized that students who actively engage in communication and interaction skills become more confident, asking questions without fear of mistakes. Similarly, Ghafournia (2023) highlighted that LLS enhance self-directed learning, and Khaliq et al. (2021) emphasized their role in reducing anxiety and promoting self-encouragement.

The specific role of Telegram in mediating LLS is also evident. The app’s features, such as voice messages, group chats, and instant peer feedback, contributed to learners’ reduced anxiety and increased confidence. Unlike mobile applications criticized for lacking interactive elements (Shamsi et al. 2019), Telegram provides real-time messaging, social support, and immediate feedback, which likely explain the very large effect size observed in this study. The platform allowed learners to engage in meaningful practice without the pressures typical of face-to-face interactions. Furthermore, the semi-structured interviews corroborated the quantitative findings, revealing that learners appreciated using voice messages for authentic conversation, participating in group discussions without fear of judgment, and accessing dictionaries and translation tools for vocabulary and pronunciation.

Methodologically, the structured intervention design, inclusion of a control group, and use of both pre- and post-tests ensured the reliability of findings, overcoming limitations observed in prior studies, such as Shamsi et al. (2019), which relied on small, non-representative samples and lacked a control group. The careful integration of Telegram features with LLS allowed learners to personalize their engagement, practice at their own pace, and receive constructive feedback, all of which likely enhanced both strategy use and anxiety reduction.

The study also highlights the cultural and contextual dimensions of strategy use. In Saudi EFL classrooms, group harmony and collaborative norms may encourage learners to adopt social strategies. Telegram provided a culturally congruent space where learners could interact comfortably with peers, ask questions, seek help, and collaboratively practice language, thus reinforcing the preference for social strategies observed in this study.

In terms of practical implications, this study demonstrates that mobile applications like Telegram can be effective tools for reducing FNE, enhancing LLS use, and promoting active participation in EFL speaking tasks. Educators may consider integrating interactive, peer-supported digital platforms into speaking curricula, as these can provide learners with a safe space for experimentation, feedback, and collaborative learning. Additionally, the findings underscore the importance of aligning strategy instruction with the digital affordances of learning tools and the sociocultural context of learners, to maximize engagement and reduce anxiety.

Overall, this study contributes to the applied linguistics literature by demonstrating that the combination of Telegram-mediated LLS and a supportive, interactive digital environment can significantly reduce FNE, increase learner confidence, and encourage the use of both direct and indirect learning strategies. The findings also highlight the importance of considering platform-specific affordances, cultural context, and instructional design in mobile-assisted language learning interventions. By facilitating low-stakes social interaction, promoting cognitive and metacognitive engagement, and allowing individualized learning, Telegram can serve as a powerful tool for EFL speaking instruction, complementing traditional pedagogical approaches.

The study highlights the importance of reducing their anxiety in FNE by LLS via Telegram. The findings suggest that integrating Telegram in EFL learning enhances learners’ interaction with peers and teachers, fostering independent learning and shifting the focus from what to learn to how to learn. Telegram not only encourages self-directed learning but also provides opportunities for collaboration and real-time feedback, creating a supportive learning environment. The study’s intervention program demonstrated that learners benefited from personalized learning with minimal teacher dependence, leading to increased confidence and reduced anxiety in FNE. These findings have key implications for both students and educators. For students, technology-assisted learning can improve speaking skills and lower anxiety in English-speaking contexts. For teachers, leveraging platforms like Telegram can enhance engagement, facilitate feedback, and support collaborative learning, ultimately fostering a more effective and less stressful language-learning experience.

The findings of the current study could serve as a strong base to take further actions to vary the EFL learning methods through allowing the use of the smartphone application Telegram as an important parties in the learning process of EFL speaking skills inside and outside the classroom. Future EFL speaking courses can be incorporated with the integration of the applications of smartphones. The findings of the current study provide university authorities with a comprehensive picture on how the explicit use of strategy mediated by application Telegram can reduce the EFL speakers’ anxiety in FNE. Besides that, they will have self-confidence and not being afraid from their teachers and peers judgments in the class, and not being afraid of making mistakes when speaking as well. Therefore, they will be able to speak effectively.

The following aspects limited the study. First, the most significant limitation is the homogeneous nature of the sample, as it only reflects the experiences of male students in the preparatory year at a single university in Saudi Arabia. Consequently, the generalizability of the results to other populations such as female students, students at different academic levels, or learners in other cultural or institutional contexts is limited. Secondly, the study relied heavily on self-report data, which is susceptible to social desirability bias. Participants may have overstated their use of Telegram or their engagement with LLS, aiming to present themselves in a favorable light. Thirdly, the measurement validity of the tools used to assess FNE and LLS. While the questionnaires and interviews were useful in gathering insights, their effectiveness in accurately capturing the depth of FNE and LLS remains questionable. Finally, this study only considered FNE of the Horwitz et al. (1986) scale of FLA, which comprises three factors: communication apprehension, FNE, and test anxiety.

Future studies should aim to include a more diverse sample, representing different institutions, regions, and proficiency levels, to ensure broader applicability of the findings. In addition, further studies could combine self-reports with actual usage data or observational methods to better capture learners’ true experiences with mobile learning tools. Future research should aim to validate these instruments in various cultural contexts and with diverse learner populations to enhance their reliability and applicability.

Furthermore, research could explore alternative digital tools beyond smartphones to accommodate students with limited access to such devices. Future studies could examine other aspects of FLA, such as communication apprehension and test anxiety, to gain a broader perspective on how technology-assisted learning impacts overall language anxiety. Moreover, placing greater emphasis on the need for studies with larger and more diverse samples could lead to more meaningful, reliable, and valid results. Finally, in Saudi Arabia, studies on Telegram-mediated LLS for reducing FNE are limited, highlighting the need for broader research on other language skills like listening, reading, and writing.