Academic achievement is not only a central indicator of students’ learning outcomes but has also long been regarded as a key factor in evaluating educational quality. Teacher support is widely recognized as an important contributor to students’ academic performance (Ansong et al. 2024; Jiang 2024; Zhou and Wu 2024). However, findings from existing empirical studies remain inconsistent. Some studies show that teacher support can significantly enhance academic achievement (Zhu et al. 2024), while others report that its effect is not always significant in specific contexts (Li et al. 2023). In addition, many studies suggest that teacher support often influences achievement indirectly through mediating variables (Lei et al. 2018; Wu and Kang 2023), whereas other studies highlight the role of moderating factors (Teng and Liu 2017). These differences suggest that the relationship between teacher support and academic achievement is not a straightforward direct link, but rather may be influenced by multiple mediators and contextual conditions. This situation underlines the need for a systematic review and integration of current evidence.

To better understand this complexity, several theoretical frameworks clarify how teacher support may influence academic outcomes. Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura 1997) emphasizes the role of supportive environments in cultivating students’ self-efficacy, a proximal predictor of achievement. Self-Determination Theory (Ryan and Deci 2000) specifies that teacher behaviors satisfying students’ needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness enhance intrinsic motivation and sustained effort. The Self-System Model of Motivational Development (Connell and Wellborn 1991) further conceptualizes teacher support as a contextual resource that strengthens self-system processes, in turn enhancing engagement and performance. Collectively, these perspectives imply that teacher support often exerts its effects through motivational and engagement mechanisms. Whether these mechanisms operate similarly in higher education – with its distinctive levels of autonomy, instructional modes, and interaction patterns – remains insufficiently synthesized, reinforcing the need for a systematic review.

It is noteworthy that systematic reviews focusing on perceived teacher support and academic achievement in higher education are still lacking. By contrast, most existing reviews concentrate on primary and secondary education (Lozano Botellero et al. 2023; Tao et al. 2022). In the higher education context, the limited available reviews have addressed different foci. For instance, Okada (2021) conducted a meta-analysis specifically on the relationship between teacher autonomy support and academic achievement, while Liu et al. (2024) examined the broader link between social support and academic achievement. Higher education differs from earlier stages in important ways. University students generally show greater autonomy and self-regulation (Arnett 2000; Chickering and Reisser 1993), and factors such as learning motivation and academic self-efficacy play a central role in their success (Bandura 1997; Ryan and Deci 2000). Teacher–student interactions are less frequent but more academically focused in higher education (Umbach and Wawrzynski 2005), and teaching formats are more diverse, including online, face-to-face, and blended learning (Bi and Bi 2024; Refide and Ismigul 2024). These differences suggest that conclusions from primary and secondary education cannot simply be generalized to the higher education context. Thus, a systematic review of studies in higher education is necessary.

The present study aims to systematically review the relationship between teacher support and academic achievement in higher education. It synthesizes existing findings, identifies key mechanisms and influencing factors, and highlights current gaps to support theoretical development and inform educational practice.

The research addresses two central questions:

-

Is there a direct link between perceived teacher support and academic achievement?

-

What indirect mechanisms explain the relationship between teacher support and academic achievement?

This systematic literature review examines the relationship between perceived teacher support and academic achievement in higher education. To ensure that the evidence was both contemporary and directly relevant, we included primary empirical studies published between 1 January 2020 and 10 September 2025. Eligible studies were required to sample higher-education students, including those enrolled in universities, colleges, postgraduate programs, or vocational/TVET institutions. They also needed to measure perceived teacher support – typically reported by students in terms of autonomy, competence, relatedness, emotional, or instrumental support – and academic achievement, which was operationalized through objective indicators such as course grades, GPA, or standardized tests, as well as validated self-report achievement measures. Only peer-reviewed journal articles published in English were considered.

Studies that did not meet these criteria were excluded. Specifically, we removed conceptual or theoretical papers, systematic reviews and meta-analyses, qualitative-only studies that did not report achievement outcomes, dissertations, conference proceedings, and other forms of grey literature.

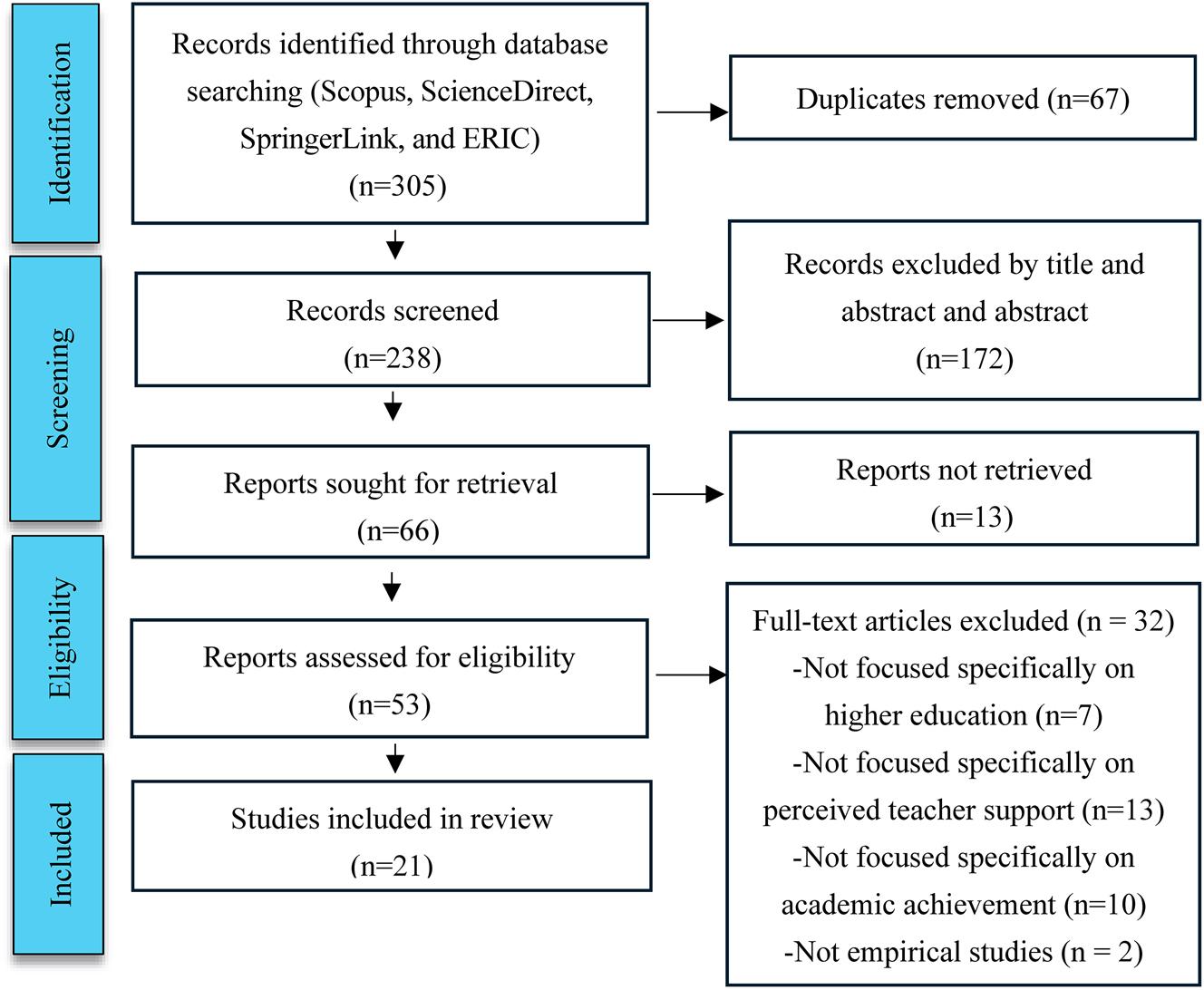

Information sources included the Scopus and ERIC databases, together with the publisher platforms ScienceDirect and SpringerLink. The search strategy combined three keyword blocks with Boolean operators, using “OR” within each block and “AND” across blocks. The first block captured teacher-support terms (e.g., “perceived teacher support”, “teacher support”, “autonomy support”, “competence support”, “relatedness/emotional support”); the second focused on academic achievement (e.g., “academic achievement”, “academic performance”, “academic success”, “learning outcome”, “GPA”); and the third targeted higher-education contexts (e.g., “university”, “undergraduate”, “college”, “vocational”, “higher vocational education”). Counts of records identified, screened, excluded, and included are presented in the Results section and depicted in the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram.

A standardized form was developed to systematically capture essential information from each study, including author(s), publication year, research setting, and primary outcomes. To ensure rigor and accuracy, data extraction was conducted independently by two researchers, with discrepancies resolved through discussion. This dual-reviewer approach helped reduce potential bias and ensured consistency in the extracted data.

The quality assessment process was carefully structured to evaluate the reliability and applicability of each study. Key criteria included the appropriateness of the research design for addressing the review questions, the representativeness of the study sample, and the suitability of the recruitment strategy. In addition, the robustness of the methods used for data collection and analysis was assessed in relation to the stated research objectives. This systematic evaluation enhanced the credibility of the review and ensured that the conclusions were grounded in sound empirical evidence.

The analysis employed a descriptive synthesis to examine the relationship between perceived teacher support and academic achievement. The review focused on three dimensions: direct associations, mediating mechanisms, and moderating factors. This approach enabled the identification of common patterns and variations across studies, thereby contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of how teacher support is linked to academic success in higher education.

The database searches initially identified 305 records. After removing 67 duplicates, 238 records remained for screening. Following title and abstract review, 172 records were excluded as irrelevant, leaving 66 full-text articles for eligibility assessment. Of these, 13 reports could not be retrieved, and the remaining 53 full-text articles were assessed in detail. A total of 32 articles were excluded for the following reasons: not higher-education population (n = 7), no measure of perceived teacher support (n = 13), no academic-achievement outcome (n = 11), and not empirical (n = 2). Ultimately, 21 primary studies met all inclusion criteria and were retained for this review. The whole selection process is illustrated in the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram (Figure 1).

Flow diagram of search strategy and study selection.

This systematic review analyzes the link between perceived teacher support and academic achievement in higher education environments from 2020 to 2025. The dataset comprises 21,202 students across 10 countries (Table 1). The largest group of participants is from China, comprising 9,491 students (44.8 %). Other notable cohorts include Spain & Portugal (474 students, 2.2 %), Malaysia (400 students, 1.9 %), Lebanon (350 students, 1.7 %), the United States (328 students, 1.5 %), Saudi Arabia (225 students, 1.1 %), Yemen (209 students, 1.0 %), Thailand & Indonesia (197 students, 0.9 %), Thailand (57 students, 0.3 %), and Japan (53 students, 0.2 %). In addition, Zou and Zou (2024) reported a global sample of 9,418 students from 41 countries, accounting for 44.4 % of the total.

Summary of sample characteristics, study design, background, and data analysis methods in the research.

| Authors (year) | Country | Sample size | Study design | Research method | Educational background | Teaching mode | Data analysis method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xu (2024) | China | 800 | C | Q | UE | FL | SEM |

| Shatila et al. (2024) | Lebanon | 350 | C | Q | UE | FL | SEM |

| Almarwani et al. (2024) | Saudi Arabia | 225 | C | Q | UE | FL | MLR |

| Wang et al. (2024) | China | 247 | C | M | UE | FL | SEM |

| Shao et al. (2023) | China | 3,514 | C | Q | UE | OL | SEM |

| Huang and Wang (2023) | China | 651 | C | Q | UE | OL | SEM |

| Zhou and Wu (2023) | China | 387 | C | Q | HVE | FL | SEM |

| Abdullah et al. (2022) | Malaysia | 400 | C | Q | UE | OL | SEM |

| Al-Awlaqi et al. (2022) | Yemen | 209 | C | Q | UE | BL | PLS-SEM |

| Chen et al. (2022) | China | 40 | E | Q | UE | BL | ANOVA |

| Goodman et al. (2021) | USA | 328 | C | Q | UE | FL | SEM |

| Aizawa (2025) | Japan | 53 | Not reported | M | UE | FL | T |

| Cai and Meng (2025) | China | 440 | C | Q | UE | FL | SEM |

| Dai (2024) | China | 100 | E | Q | UE | OL | G |

| Du et al. (2024) | China | 202 | C | Q | UE | FL | HR |

| Homyamyen et al. (2025) | Thailand & Indonesia | 197 | C | Q | UE | OL | SEM |

| Huéscar Hernández et al. (2020) | Spain & Portugal | 474 | C | Q | UE | FL | SEM |

| Taylor (2024) | Thailand | 57 | Not reported | M | UE | BL | T |

| Zhang (2024) | China | 2,543 | C | Q | UE+ HVE | BL | SEM |

| Zhang et al. (2024) | China | 567 | C | Q | ME | FL | SEM |

| Zou and Zou (2024) | 41 countries (global sample) | 9,418 | C | Q | UE | OL | SEM |

C, cross-sectional; E, experimental; Q, quantitative; M, mixed methods; UE, university education; HVE, higher vocational education; ME, master’s education; BL, blended learning; FL, face to face learning; OL, online learning; MLR, multiple linear regression; PLS-SEM, multigroup PLS-SEM; ANOVA, two-way repeated measures ANOVA; HR, hierarchical regression analysis; G, group mean comparison; T, thematic analysis.

Among the studies contributing to the sample size, the majority focused on university education (n = 18), with only one study focusing on higher vocational education, one on master’s education, and one that simultaneously addressed both university and higher vocational contexts. Regarding instructional modes, 11 studies investigated face-to-face learning (4,073 participants, 19.2 %), six studies focused on online learning (14,280 participants, 67.3 %), and four studies examined blended learning (2,849 participants, 13.5 %).

In terms of research method, the overwhelming majority relied on quantitative approaches (n = 19; 90.5 %), whereas three studies employed mixed-methods approaches (n = 3; 14.3 %) ( Aizawa 2025; Taylor 2024). Regarding study design, most studies adopted a cross-sectional approach (n = 17; 81.0 %), while two employed experimental designs (n = 2; 9.5 %) (Chen et al. 2022; Dai 2024), and another two did not explicitly report their study design (n = 2; 9.5 %) (Aizawa 2025; Taylor 2024).

As for data analysis methods, structural equation modeling (SEM) was the most widely used, appearing in 14 studies (66.7 %). Other regression-based techniques were also applied, including multiple linear regression (MLR), hierarchical regression (HR), and multigroup PLS-SEM, each reported in one study. Experimental designs drew on two-way repeated-measures ANOVA (Chen et al. 2022) and group-mean comparison (Dai 2024). For studies using qualitative components within mixed-methods designs, thematic analysis was employed (Aizawa 2025; Taylor 2024).

These findings demonstrate that research on perceived teacher support and academic achievement in higher education between 2020 and 2025 has been primarily cross-sectional, quantitative, and SEM-based, supplemented by a smaller number of experimental and mixed-methods contributions employing diverse analytic strategies. The detailed summary is presented in Table 1.

Among the reviewed studies, four did not employ questionnaires or standardized scales: Aizawa (2025) and Taylor (2024), which applied mixed-methods approaches; and Dai (2024), which used an experimental design. Although Wang et al. (2024) also conducted a mixed-methods study, its examination of the relationship between teacher support and academic achievement relied on quantitative data and thus incorporated standardized measures. Accordingly, a total of 18 studies in this review utilized scales to assess perceived teacher support and academic achievement. The details of these instruments are summarized in Table 2.

Summary of measurement tools in the research.

| Authors (year) | Perceived teacher support measures | Academic achievement measures | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scale | Dimensional structure | Scale | Dimensional structure | |

| Xu (2024) | Teacher support questionnaire | Autonomy support, emotional support, competence support | GPA | – |

| Shatila et al. (2024) | Perceived teacher support | Not reported | Academic performance scale | Single dimension |

| Almarwani et al. (2024) | Learning climate questionnaire | Perceived teacher autonomy support | GPA | – |

| Wang et al. (2024) | Tteacher autonomy support scale | Teacher autonomy support | IELTS speaking test | – |

| Shao et al. (2023) | Teachers’ emotional support scale | Positive classroom climate, teacher sensitivity, regard for students | Learning gains scale | Cognitive gains, skill gains, and affective gains |

| Huang and Wang (2023) | Course experience questionnaire | Single dimension | Academic achievement scale | Single dimension |

| Zhou and Wu (2023) | Learning climate questionnaire | Independent support, emotional support, ability support | Academic achievement scale | Learning cognitive ability, communication ability, self-management ability, interpersonal promotion. |

| Abdullah et al. (2022) | Teacher emotional support scale | Emotional support, academic support | Academic performance scale | Academic efficacy, self-perceived performance. |

| Al-Awlaqi et al. (2022) | Teacher academic support scale | Autonomy support, competence support | Learning performance scale | Not reported |

| Chen et al. (2022) | Teacher support scale | Cognitive support, emotional support | Chinese graduate psychology examination | – |

| Goodman et al. (2021) | Teacher support scale | Emotional support, academic support | GPA | – |

| Cai and Meng (2025) | Perceived teacher support scale | Learning support, emotional support, capacity support | GPA | – |

| Du et al. (2024) | Social support scale | School support, friend support, teacher support | Academic achievement scale | Single dimension |

| Homyamyen et al. (2025) | Teacher support scale | Teacher assistance, encouragement, accessibility, responsiveness | Learning achievement scale | Not reported |

| Huéscar Hernández et al. (2020) | Basic psychological need in exercise scale | Autonomy satisfaction, competence satisfaction, relatedness satisfaction | GPA | – |

| Zhang (2024) | Social support rating scale | Family support, peer support, teacher support, school support | Academic performance scale | Academic achievement, learning attitude, learning ability, innovation |

| Zhang et al. (2024) | Supervisor support scale | Not reported | Academic achievement scale | Academic dedication, academic performance, academic skills, and overall self-performance. |

| Zou and Zou (2024) | Perceived teacher support | Not reported | Learning outcomes scale | Not reported |

“–” Indicates that the study did not address the corresponding research aspect.

Perceived teacher support was measured with diverse instruments that varied in dimensionality. Some studies have adopted single-dimensional approaches, treating teacher support as a unified construct (e.g., Huang and Wang 2023; Shatila et al. 2024). In contrast, others employed multidimensional measures that distinguished between autonomy, emotional, competence, or ability support (e.g., Xu 2024; Zhou and Wu 2023; Wang et al. 2024; Cai and Meng 2025; Al-Awlaqi et al. 2022). Broader frameworks, such as the Social Support Scale (Du et al. 2024) and Social Support Rating Scale (Zhang 2024), also included teacher support as one of several subdimensions. Additionally, some studies targeted specific dimensions, such as emotional or academic support (Abdullah et al. 2022; Chen et al. 2022; Goodman et al. 2021; Homyamyen et al. 2025; Shao et al. 2023). A few papers only mentioned “perceived teacher support” without reporting dimensional structure (e.g., Zhang et al. 2024; Zou and Zou 2024), limiting comparability across studies.

In the included studies, academic achievement was measured in diverse ways, using both objective indicators and self-report scales (see Table 2). Objective indicators mainly included GPA (e.g., Xu 2024; Goodman et al. 2021; Cai and Meng 2025), standardized tests such as the IELTS speaking test (Wang et al. 2024), and national examinations (Chen et al. 2022). For self-report measures, all instruments were used by the original authors to assess academic achievement, but they differed in name and focus. The Academic Performance Scale (e.g., Shatila et al. 2024; Zhang 2024; Abdullah et al. 2022) was usually designed to measure students’ overall academic performance, sometimes as a single dimension, and sometimes divided into aspects such as achievement, learning attitude, or innovation. The Academic Achievement Scale was applied as a single-dimension indicator in some studies (e.g., Huang and Wang 2023; Du et al. 2024), while in others it was reported as a multidimensional structure (e.g., Zhou and Wu 2023; Zhang et al. 2024), covering areas such as cognitive ability, communication, self-management, and interpersonal promotion. The Learning Gains Scale (Shao et al. 2023) emphasized students’ progress in cognition, skills, and affective aspects rather than absolute performance. Other scales did not report their dimensional structure in detail. Overall, these measures reflect substantial heterogeneity in how academic achievement is operationalized across studies.

Eighteen studies reported a positive direct association between perceived teacher support and academic achievement. Among these studies, several further examined specific dimensions of teacher support—such as autonomy support (Almarwani et al. 2024; Huéscar Hernández et al. 2020) and emotional or academic support (Abdullah et al. 2022)—and also found positive effects on academic achievement. In contrast, one study (Chen et al. 2022) reported a non-significant or negative relationship.

Fifteen studies examined the indirect pathways linking perceived teacher support to academic achievement. Eleven of these focused on single mediators, including academic self-efficacy, academic emotions, perceived enjoyment, achievement motivation, student engagement, learning engagement, goal orientation, and positive academic emotions. Four studies tested chained mediation models, such as basic psychological needs → classroom engagement (Wang et al. 2024), mindfulness → test anxiety cognitive symptoms (Goodman et al. 2021), academic self-efficacy → learning engagement (Zhou and Wu 2023), and basic psychological needs → intrinsic motivation → grit (Huéscar Hernández et al. 2020). Among these mediators, academic self-efficacy and basic psychological needs emerged as the most frequently examined. In terms of mediation outcomes, fourteen studies provided evidence for significant mediation effects. Among them, three studies (Goodman et al. 2021; Huang and Wang 2023; Zhou and Wu 2023) identified full mediation, while nine reported partial mediation. For Dai (2024), who adopted an experimental design, learning engagement was suggested as a mediating variable but not formally tested, leaving the mediation pathway less clear. In contrast, Homyamyen et al. (2025) reported no significant mediation effect, with learning motivation as the proposed mediator.

In addition to mediation, one study investigated moderating mechanisms. Chen et al. (2022) found that task difficulty moderated the link between teacher support and academic achievement. Across the reviewed studies, mediation was examined more frequently than moderation. Table 3 provides an overview of the direct relationships, underlying mechanisms, and effect types.

Summary of the link between perceived teacher support and academic achievement in the research.

| Authors (year) | Direct relationship | Mechanisms | Effect type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Xu (2024) | Positive | Academic self-efficacy, academic emotions | Partial mediation |

| Shatila et al. (2024) | Not reported | Perceived enjoyment | Partial mediation |

| Almarwani et al. (2024) | Positive | Not reported | Not reported |

| Wang et al. (2024) | Positive | Basic psychological needs – classroom engagement | Partial mediation |

| Shao et al. (2023) | Positive | Achievement motivation, basic psychological needs | Partial mediation |

| Huang and Wang (2023) | Positive | Academic self-efficacy, student engagement | Full mediation |

| Zhou and Wu (2023) | Positive | Academic self-efficacy, learning engagement, | Full mediation |

| Abdullah et al. (2022) | Positive | Not reported | Not reported |

| Al-Awlaqi et al. (2022) | Positive | Not reported | Not reported |

| Chen et al. (2022) | Not significant | Task difficulty | Moderation |

| Goodman et al. (2021) | Positive | Mindfulness – test anxiety cognitive symptoms | Full mediation |

| Aizawa (2025) | Positive | Not reported | Not reported |

| Cai and Meng (2025) | Positive | Not reported | Not reported |

| Dai (2024) | Not reported | Learning engagement | Indirect pathway suggested |

| Du et al. (2024) | Positive | Goal orientation | Partial mediation |

| Homyamyen et al. (2025) | Positive | Learning motivation | Non-significant |

| Huéscar Hernández et al. (2020) | Positive | Basic psychological needs – intrinsic motivation – grit | Partial mediation |

| Taylor (2024) | Positive | Not reported | Not reported |

| Zhang (2024) | Positive | Mental health | Partial mediation |

| Zhang et al. (2024) | Positive | Positive academic emotions | Partial mediation |

| Zou and Zou 2024 | Positive | Academic emotions | Partial mediation |

This review synthesizes evidence on the relationship between perceived teacher support and academic achievement in higher education. The discussion highlights inconsistencies in direct effects, examines mediating mechanisms such as basic psychological needs and academic self-efficacy, and reflects on methodological and contextual limitations. Together, these issues help explain variations in existing findings and indicate directions for future research.

Of the studies that explored the direct link between perceived teacher support and academic achievement, the evidence was largely consistent, with only one study (Chen et al. 2022) failing to identify a significant effect. The exceptional finding may be related to its experimental design in a non-traditional blended-learning context, which differs from the cross-sectional designs used in most of the remaining studies.

Differences in research design and context may partly explain these discrepancies, a view consistent with methodological literature suggesting that study design can shape outcomes (Lever 1981; Ojoboh and Igben 2024), analytic strategies affect the interpretation of statistical significance (Hasan 2024), and measurement choices, as well as contextual factors influence comparability across studies (Andriukhina 1997; Chang et al. 2023; Fávero et al. 2023). Thus, the value of these findings lies not in questioning the teacher support–achievement link, but in showing that its magnitude and detectability depend on design features, assessment types, and learning environments.

A wide range of mediating variables has been investigated to explain how teacher support influences academic achievement, with basic psychological needs (BPNs) and academic self-efficacy emerging as the most frequently examined. However, the evidence concerning their mediating roles remains far from uniform, reflecting both theoretical orientations and measurement practices.

Regarding BPNs, studies have demonstrated divergent pathways depending on the theoretical framework employed. Drawing on Self-Determination Theory (SDT), Shao et al. (2023) conceptualized BPNs as direct mediators linking teacher emotional support to academic achievement. In contrast, Wang et al. (2024), adopting the Self-System Model of Motivational Development (SSMMD), argued that BPNs must operate within a chained mediation pathway alongside classroom engagement. Similarly, Huéscar Hernández et al. (2020), also grounded in SDT, reported that BPNs partially mediated the relationship through a sequential pathway of BPNs → intrinsic motivation → grit, thereby indirectly contributing to academic achievement. These findings suggest that the same mediating construct can function through distinct mechanisms depending on the theoretical framework applied (William 2024). SDT posits that the fulfillment of autonomy, competence, and relatedness is essential for fostering intrinsic motivation and optimal functioning (Deci and Ryan 2000). Within educational contexts, teacher support is viewed as a critical contextual factor that facilitates the satisfaction of these needs, thereby enhancing students’ academic achievement (Niemiec and Ryan 2009). By contrast, the SSMMD emphasizes the interaction between social contexts (e.g., classroom climate, teacher support) and students’ self-perceptions, explaining how these processes shape learning motivation and achievement outcomes (Connell and Wellborn 1991). Taken together, these studies suggest that the theoretical orientation adopted in a given study not only influences the interpretation of mediating mechanisms but may also shape the conclusions derived. While such differences may yield divergent findings, they also offer a multidimensional lens for future research, enabling a more nuanced and comprehensive understanding of how teacher support contributes to academic achievement.

Academic self-efficacy has also been widely tested, but results are inconsistent. Huang and Wang (2023) and Zhou and Wu (2023) reported complete mediation, while Xu (2024) observed only partial mediation. One possible explanation for these differences lies in substantial variations in measurement practices. Xu (2024), for instance, employed a multidimensional teacher support scale and GPA as an outcome, finding that academic self-efficacy only partially mediated the relationship, suggesting that other unmeasured factors might also directly influence academic performance. In contrast, Huang and Wang (2023) treated teacher support as a holistic variable and used the Academic Achievement Scale, yielding evidence of full mediation. However, this approach of not differentiating dimensions may obscure potential complex relationships between variables (Preacher and Hayes 2008). Similarly, Zhou and Wu (2023) divided perceived teacher support into independent support, emotional support, and ability support, and used the Learning Engagement Scale to measure academic achievement. Their study underscored the independent mediating role of academic self-efficacy and even proposed the possibility of forming a chained mediation with learning engagement. These examples underscore how different operationalizations and dimensional distinctions can shape the observed mediating effects of academic self-efficacy.

These varying measurement approaches, along with the specific characteristics and limitations of each scale, likely contribute to the observed inconsistencies (Berbar et al. 2022; Gonzalez and MacKinnon 2021; Karpagam et al. 2011). Therefore, standardizing measurement dimensions and developing validated multidimensional tools in educational research are particularly important (Chang et al. 2020; Margulieux et al. 2019 ). Uniform measurement standards enhance the comparability of results across different studies and provide more systematic and consistent evidence for theory-building and practical application (Dickersin and Mayo-Wilson 2018; Sharma and Singh 2019). Such an approach will improve validity and reliability, thereby yielding deeper insights into the intrinsic mechanisms through which teacher support influences academic achievement.

In addition to these dominant constructs, other mediators such as academic emotions, perceived enjoyment, achievement motivation, student or learning engagement, goal orientation, and positive academic emotions have also been examined, albeit less consistently. While many of these studies reported significant indirect effects, their small number and diverse conceptualizations hinder the accumulation of systematic evidence. Importantly, not all mediators produced significant findings. Homyamyen et al. (2025), for example, tested learning motivation as a mediator but found no significant effect. As this remains the only study examining this pathway, the evidence is best regarded as exploratory rather than conclusive.

Taken together, the diversity of mediators illustrates both the richness and fragmentation of current research. On the one hand, it demonstrates that teacher support can enhance academic achievement through multiple psychological and motivational routes. On the other hand, the lack of replication, theoretical integration, and measurement standardization prevents firm conclusions about which mechanisms are most robust. Future studies should not only consolidate evidence for central mediators such as BPNs and academic self-efficacy but also revisit less studied or non-significant pathways, like learning motivation, to clarify whether they represent context-specific anomalies or genuinely weak mechanisms.

In contrast to the extensive focus on mediation, moderating mechanisms have been rarely examined. Only Chen et al. (2022) reported that task difficulty moderated the relationship between teacher support and academic achievement, indicating that the effect of teacher support can vary depending on contextual factors. Potential moderators, such as students’ self-efficacy, motivation, psychological capital, or instructional conditions (e.g., teaching modality, subject domain, cultural context), remain largely unexplored. Future studies should systematically investigate these conditional processes, including moderated mediation models, to capture how teacher support may operate differently across individuals and settings.

The reviewed studies drew on a variety of theoretical frameworks to explain how teacher support fosters academic achievement. The majority were grounded in Self-Determination Theory (SDT), underscoring its dominant role in conceptualizing teacher support as a contextual factor that satisfies students’ autonomy, competence, and relatedness needs, thereby enhancing motivation and performance. Beyond this dominant paradigm, several studies adopted alternative perspectives. For instance, Zhang et al. (2024) employed Social Support Theory and the Control-Value Theory of achievement emotions to frame teacher support as a form of social resource that reduces stress and regulates academic emotions. Similarly, Zhang (2024) utilized broader frameworks such as Ecological Systems Theory, Stress-buffering Theory, and Psychological Capital Theory to highlight the interplay between environmental contexts, psychological resilience, and student achievement. Homyamyen et al. (2025) integrated multiple perspectives, drawing on SDT, Cognitive Load Theory (CLT), and Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) to capture the motivational, cognitive, and self-efficacy dimensions of teacher support. In addition, Wang et al. (2024) adopted the Self-System Model of Motivational Development (SSMMD) to emphasize the role of students’ self-perceptions within supportive classroom climates. Notably, seven studies did not explicitly report any theoretical framework, limiting the interpretability and theoretical grounding of their findings.

This distribution highlights both the strength and limitations of the current knowledge base. On the one hand, the dominance of SDT has provided a strong and coherent explanatory foundation, enabling the accumulation of insights into the motivational processes linking teacher support to academic outcomes. On the other hand, the fragmented use of alternative frameworks and the absence of explicit theoretical grounding in several studies suggest that theoretical pluralism remains underdeveloped. Moreover, little is known about whether studies guided by different theories yield systematically different findings – for instance, whether SDT-based studies are more likely to report significant mediating effects compared to those grounded in alternative perspectives.

Future research should place greater emphasis on theoretical clarity and integration. Explicitly situating studies within guiding frameworks not only enhances interpretability but also facilitates cross-study comparisons. At the same time, comparative research across multiple theories may deepen understanding of the mechanisms through which teacher support shapes academic achievement, moving the field beyond reliance on a single dominant paradigm and toward a more integrative theoretical landscape.

Most of the reviewed studies employed a cross-sectional design, which can identify associations but is insufficient for establishing causal relationships or capturing dynamic mechanisms. Although the findings on the indirect effects of perceived teacher support on academic achievement are consistently significant, the reliance on cross-sectional data restricts the ability to confirm temporal ordering and assess whether the mediating variables genuinely shape the relationship or whether the observed associations are driven by unmeasured confounding factors (Kelly et al. 2024; Voleti 2024). Notably, only two studies adopted experimental designs (Chen et al. 2022; Dai 2024), further highlighting the scarcity of rigorous causal evidence. Therefore, future research on mediating mechanisms would benefit from employing longitudinal designs, which trace changes in variables over time and clarify causal directionality (Lin 2023; McCormick et al. 2023; Ruspini 2023), as well as experimental approaches that allow stronger causal inferences under controlled conditions (Ashraf et al. 2024). Such designs can provide a more robust understanding of how perceived teacher support contributes to academic achievement over time.

Nearly half of all participants were drawn from China, with relatively few studies conducted elsewhere, raising concerns about cultural and regional bias. Educational levels were also unevenly represented, with most studies targeting undergraduates and only limited evidence from vocational or graduate contexts. Instructional modes showed a similar imbalance: two-thirds of participants were from online learning environments, while blended and face-to-face contexts were less studied. These asymmetries suggest that the role of teacher support may be shaped by cultural norms, educational levels, and learning modalities, yet existing evidence provides only partial insight into such variations. Moreover, although mediation has been widely examined, research on moderation remains limited, with only one study providing evidence so far. Building on these initial findings, future research could investigate whether other contextual or individual factors also moderate this relationship. Addressing these contextual and methodological gaps is crucial for building a more comprehensive and context-sensitive understanding of how teacher support contributes to academic achievement.

This review has several limitations that should be considered. First, the search strategy was restricted to four major databases (Scopus, ScienceDirect, SpringerLink, and ERIC) and English-language publications, which may have led to the omission of relevant studies published in other languages or indexed in different databases. Second, the review covered studies published between 2020 and 2025, which ensured currency but excluded earlier research that might have provided valuable insights into long-term trends. Third, although a standardized extraction and quality assessment process was applied, the inclusion of only 21 studies limits the breadth of evidence available for synthesis. Fourth, the review did not employ meta-analytic techniques to quantify effect sizes, which restricts the ability to draw statistical conclusions about the strength of associations. Finally, despite efforts to minimize bias through dual data extraction and structured analysis, subjective judgments in study selection and interpretation cannot be entirely ruled out.

This review provides comprehensive evidence on the relationship between perceived teacher support and academic achievement in higher education. Overall, the findings confirm that teacher support plays a vital role in promoting student achievement, both directly and indirectly through mediating mechanisms such as academic self-efficacy, basic psychological needs, and student engagement. At the same time, methodological and contextual imbalances highlight the need for more rigorous and diversified research designs. Future studies should adopt longitudinal or experimental approaches to strengthen causal claims, expand investigations to underrepresented educational levels and cultural contexts, and develop standardized measurement tools to enhance comparability across studies. By addressing these gaps, future research can contribute to a more nuanced and context-sensitive understanding of how teacher support fosters academic success, thereby informing theory building and guiding evidence-based educational practice.