Publisher's note: A correction article relating to this article has been published and can be found at https://transactions.ismir.net/articles/10.5334/tismir.260/.

1 Introduction

Salsa is a renowned musical style that came to life in the second half of the 20th century (the word “salsa” translates to “sauce” in English) and was designed by urban musicians of Latin American and Caribbean descent living in New York City (Rondón, 2008). While the term “salsa” encompasses a wide range of subgenres and, as its name suggests, represents a fusion of diverse influences, several key characteristics consistently define this musical genre. It combines polyphonic percussion arrangements, inherited from its Afro‑diasporic origin, with Western traditional instruments to derive a dance‑oriented urban folk music style (Flores, 2016). As we will expand upon below, the rhythmic construction of salsa music, specifically the interplay of percussive sounds, with each other and with the beat, causes it to be experienced as a complex aural stimulus. Especially when listening intention is focused on following the music with the body, dancing or playing, finding the beat (that comfortable sensation of anticipating repetition in a temporal event) can become a difficult activity. Our aim in this text is to introduce concepts that account for some of the complexity of human beat estimation in salsa, then present a salsa music dataset with precise beat annotations that is suited for rhythm research, and finally assess state‑of‑the‑art beat estimation algorithms with this dataset.

There are different projects that have been involved with Latin American music rhythm analysis (Cano et al., 2020; Maia et al., 2018; Nunes et al., 2015), and another has explored beat estimation in salsa (Dong et al., 2017). However, there is a lack of a common ground truth among scientific peers when it comes to training and testing robust beat estimation models for salsa. Having this common ground will allow researchers to create a benchmark associated with such a ground truth. Consequently, accuracy claims of different research endeavors could be tested and compared. To provide this ground truth, we have developed a reliable corpus of beat‑annotated salsa music songs. Specifically, we have undertaken three key activities, each of which will be elaborated upon in this text:

Definition of a salsa music dataset: We curated a comprehensive dataset of salsa music, featuring various musical compositions representing salsa’s diverse subgenres. This dataset was meticulously assembled using the expertise of music professionals.

Expert annotation of beat occurrences: Our experts painstakingly annotated beat occurrences across 124 salsa songs. To ensure accuracy, these annotations underwent a rigorous double‑checking process by a second group of experts, resulting in the creation of the first robust salsa beat dataset designed for music research.

Evaluation of two contemporary beat estimation models using the songs in our salsa dataset as the ground truth.

The following sections of this text offer insights into salsa music, followed by a comprehensive description of the methods used for its development and an evaluation of contemporary beat estimation models in the dataset. Finally, we conclude with an outline of how this work can contribute on further research.

2 The Cognitive Experience of Salsa

2.1 Musical traits of salsa

A fundamental element of salsa rhythm is the clave, a five‑note rhythmic pattern that interacts with music at different levels, aiding the cognitive construction of pulse and meter (Simpson‑Litke and Stover, 2019; Stover, 2017; Toussaint, 2003). In many musical cultures of African origin, the notion of clave plays an essential role, which has propagated further to Afro‑diasporic music. On a performative level, the clave acts as a herald, announcing the anticipated patterns to be executed by all instruments within the salsa ensemble. At a stylistic level, it also conveys the song’s distinctive style. A clave pattern is used as a rhythmic reference for instrumental and embodied articulation, and it can be explicitly played (usually by the homonymous wooden instrument) or be implicit in the minds of expert listeners, musicians, and dancers.

The central role of clave highlights the percussive nature of salsa music above other musical features, which in a typical salsa ensemble is manifested as a rhythm section composed of six different instruments, namely congas, bongos, timbales, clave, cowbell, and maracas—each instrument playing different rhythmic patterns simultaneously. The sonic richness of this percussive ensemble is vastly expanded by the hand strikes of its performers, increasing the polyphonic diversity, uniquely unfurling in a multiplicity of timbres and rhythmic patterns that are played simultaneously. Traditional Western instruments, such as the double bass, piano, a brass section, and vocals, often complement this ensemble, further enhancing the richness of salsa music.

2.2 Why salsa is experienced as a complex rhythm

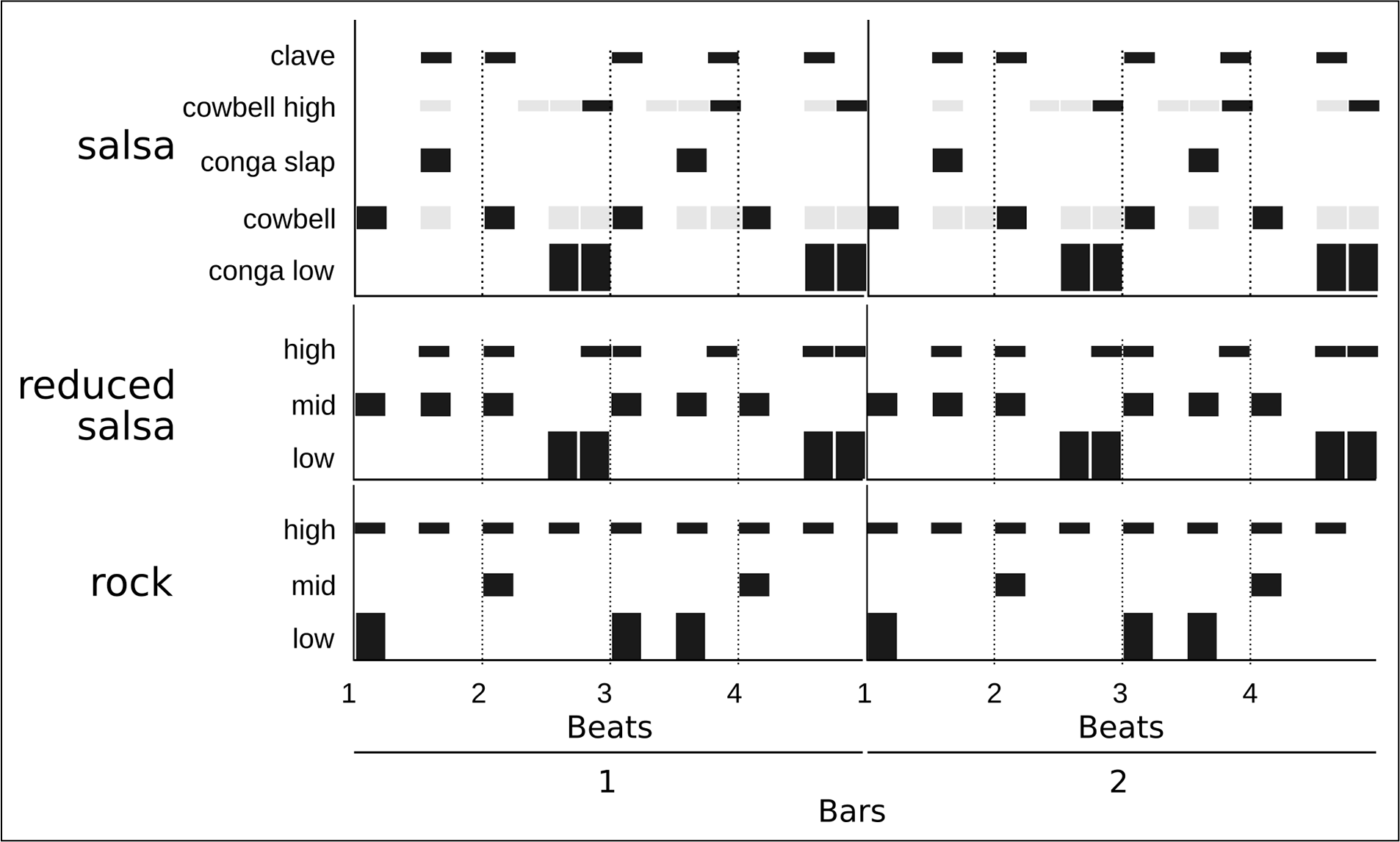

From a listener’s perspective, noting each overlapped rhythmic layer of an ensemble all at once can be a complex activity, but as the sound sources come together in a salsa song, there is a sense of unity and rhythm. This perception of agreement is the product of our auditory system, as our mind blends multiple musical tracks into a few so we can process such complexity using reduced bandwidth (Bregman, 1994). This attentive process is dynamic, as diverse sounds are blended to ease the resources needed for their perception, but detail can be attained by the listener singling out specific sounds (i.e., listening to the whole song or just paying attention to the congas). The unified rhythm derived from the different sound streams present in salsa music is rather sophisticated, especially for the Western listener, as the strongest sounds do not accentuate all the beats induced by the music (Fitch, 2016; see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Salsa pattern (top) and three‑instrument reductions of salsa and rock (center and bottom). The salsa pattern (top) presents accentuated onsets in a dark color and unaccentuated onsets in grey.

To have a complete picture of this phenomenon, it has to be understood that the periodic pulse sensation one feels when listening to music (that feeling that makes us move our head or tap our toe rhythmically) is a cognitive response to music. It is a mental grid that our minds impose on top of music to be able to process and understand it. This “grid,” or more commonly our pulse sensation, is highly influenced by explicit, strong, low‑frequency, and high‑energy sounds (such as the ones produced by the kick drum). By exposing ourselves to sounds with some degree of repetition (such as music), our mind deduces beats by studying their surface, specially guided by low‑frequency high‑energy sounds, and is able to distinguish pulses and anticipate upcoming ones (Lenc et al., 2018). The term “pulse” is used to describe the internalized periodic sensation, and the term “beat” is used to describe its objective manifestation in music. Beat keeping is based on a feedback system where pulse sensations are expected to be confirmed by the beats in the music.

When listening to rhythmic music, individuals often spontaneously organize beats into groups and establish hierarchies among them, perceiving certain beats as more accentuated than others. A recurring group of beats that commences with an accentuated one is termed a “bar,” with the most accentuated beat being referred to as the “downbeat.” Furthermore, it is also common to visualize even subdivisions within the beats of a bar. The resultant internalized structure from grouping and subdividing beats is known as “meter.” This innate ability to discern a metrical structure is crucial in musical activities such as singing, playing instruments, and dancing. Nevertheless, this cognitive process can present challenges in certain instances, as observed when engaging with genres such as salsa music.

Salsa music, despite its widespread popularity, introduces complexities due to its polyphonic rhythmic ensemble, which can challenge both listeners and dancers. While salsa always maintains a discernible beat, the music’s texture does not consistently emphasize beats with strong low‑frequency and high‑energy instruments. For instance, salsa often features a syncopated bass pattern, such as the tresillo or tumbao, where the bass plays offbeat eighth notes just before the “three” downbeat, remaining silent on the “one” (Fitch, 2016; Moore and Moore, 2010; Rebeca, 1993; refer to Figure 1 for a simple salsa pattern and its three‑instrument reduction).

This lack of confirmation of the anticipated periodic beats , known as syncopation, contributes to a perceived sense of rhythmic complexity in salsa and similar genres, where maintaining the beat can be challenging (Fitch, 2013). Recent studies in polyphonic settings (Hove et al., 2014) suggest a hierarchy wherein the timbre brightness1 (Pearce, 2017) inversely correlates with the salience of syncopation sensation in polyphonic rhythms. In simpler terms, when exposed to various sounds with different brightness levels and playing diverse patterns, the lowest frequency sound (opposite to bright) has the most significant impact on suggesting the beat. Consequently, in salsa music, where low‑frequency sounds anticipate rather than accentuate the beat, the entire percussive arrangement can create friction with our beat‑keeping mechanisms.

This specific feature of salsa has been described in detail, suggesting how, “To those unfamiliar with salsa music, this concentration of low‑frequency energy on offbeats makes it a challenge to even locate the downbeat cognitively (although other instruments, including both vocals and percussion, make the meter clear nonetheless). But to an experienced salsa listener/dancer, the context of the other instruments (particularly the clave, a percussive ostinato at the heart of salsa rhythms) makes the meter obvious, and the injection of bass energy at the syncopated upbeat point in the dance step is precisely what makes salsa groove” (Fitch, 2016).

This contrast is exemplified by juxtaposing a traditional salsa percussion pattern (Figure 1, top and center) with a classic rock drum pattern (Figure 1, bottom). By categorizing salsa and rock instruments into three frequency ranges—low, mid, and high (Figure 1, center and bottom)—it becomes apparent that, in salsa music, only mid‑frequency onsets emphasize the downbeat, while low‑frequency sounds introduce syncopation against the beat. This introduces a challenge when it comes to beat prediction, as low‑frequency sounds play a significant role in pulse entrainment. Additionally, high‑frequency instrument onsets in salsa exhibit syncopation and are not uniformly distributed across the two bars, contributing to a sense of complexity and intricacy in the arrangement (Milne and Herff, 2020).

In contrast, in rock music, the downbeat is distinctly emphasized by the onsets of low‑frequency instruments, such as the kick drum; subsequent beats are accentuated by mid‑ and low‑frequency instrument onsets; and high‑frequency instrument onsets are evenly spread throughout the two bars. Consequently, the overall rhythmic perception between the two genres differs significantly. Rock music offers clear structural and timbral cues to the human beat‑tracking system, making pulse prediction less demanding, whereas salsa music presents challenges in this regard, complicating the task for the listener.

Salsa music patterns comply with the observations posed above about multiple polyphonic and syncopated rhythms and loosely accentuated beats; therefore, they are perceived as complex stimuli in which the beat is hard to keep, essentially because salsa does not offer clear affordances for the beat‑keeping system. For listeners growing up with music that explicitly emphasizes beat occurrences (as happens in most Western popular musical genres), the implicit or unaccented beats are cumbersome, as the cognitive system in charge of defining the beats has not been trained with such information.

3 Technical Background

There are notably few studies of salsa music from a technological perspective (Dong et al., 2017; Peeters, 2005; Romano et al., 2019), perhaps because there is a lack of common and appropriately annotated datasets or even the means to obtain the annotations accurately. This translates into an absence of predictive or analytic algorithms in that context and, particularly, of algorithms specifically designed to predict the beat in salsa music. Regarding the existing works dealing with salsa, one of them focuses on helping to improve salsa dancing technique by providing sound feedback on the beat position (Dong et al., 2017); another one uses digital signal processing to compute an approximation of the beat position on the basis of onset detection (Peeters, 2005); and a third one focuses on multiple genres, including a few samples of salsa songs, to compute the tempo on the basis of digital signal processing (Romano et al., 2019).

A non‑exhaustive review of reported and available datasets for beat estimation, suggests 21 datasets commonly used in the music information retrieval (MIR) literature (Table 1). The total beat annotations included per dataset vary from 692,633 (Aligned Scores and Performances [ASAP] dataset) to 738 (Cuban son and salsa), with a mean value of 109,140. Some datasets (10) contain elements of a single musical genre (classical piano music, Carnatic music, Western pop, jazz, rock, samba, bambuco, or candombe), while others (11) contain mixed genres and subgenres (classical, chanson, jazz, blues, solo guitar, cha cha, rhumba, jive, quickstep, samba, tango, Viennese waltz, slow waltz, pop, rock, salsa, son, hardcore, jungle, and drum and bass). The total number of annotations per genre (when specified in the respective paper) varies from 379,065 (HarmonixSet) to 738 (Cuban son and salsa). Some Afro‑Latin genres are present in the reviewed datasets with a large number of annotations, namely candombe, samba, bambuco, and a mix of Brazilian genres. However, one of the genres with the smallest number of beat annotations (738) and songs (5) is the Cuban son and salsa dataset. Given that it combines two different genres in five songs, we believe it is not a meaningful corpus for training robust beat estimation systems. Considering the previous context, the salsa dataset contains more annotated beats than the median (median = 44,605) and focuses on this specific underexposed musical branch of Afro‑Latin music. Therefore, the salsa dataset composed of 124 songs with beat annotations is the most robust dataset available to carry out beat estimation research in salsa music and the largest number of annotations in a specific Latin American musical genre.

Table 1

List of published datasets (including salsa) focused on beat estimation including their year of publication, total music time, total beat annotations, genres, and number of songs per style

| Name | Year | Time (s) | Beats | Genres | Pieces |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hainsworth | 2004 | 11,940 | n/r | Multiple | 221 |

| Klapuri | 2005 | 30,240 | 60,600 | Multiple | 505 |

| Simac | 2005 | 11,960 | n/r | Multiple | 595 |

| Mirex06 | |||||

| Train | 2006 | 600 | n/r | n/r | 20 |

| QMUL: | |||||

| Beatles | 2009 | 29,333 | 52,729 | Rock | 180 |

| QMUL: | |||||

| Zweieck | 2009 | 3,200 | 6,553 | Pop | 18 |

| SMC Mirex | 2012 | 8,680 | 10,700 | Multiple | 217 |

| Hardcore | |||||

| HJDB | 2012 | 11,940 | n/r | jungle | 236 |

| drum ’n’ bass | |||||

| Ballroom | 2013 | 20,940 | 44,605 | Multiple | 698 |

| RobbieW. | 2013 | 16,200 | 6,787 | Pop | 62 |

| CarnaticR | 2014 | 57,600 | 89,627 | Indian | 176 |

| Candombe | 2015 | 7,200 | 4,700 | Candombe | 26 |

| GTZAN | 2015 | 30,000 | 204,784 | Blues, | 1,000 |

| Classical | |||||

| Jazz | |||||

| Audio‑Alig. | 2018 | 25,200 | 68,570 | Jazz | 113 |

| Harmony | |||||

| Dataset | |||||

| BRID | 2018 | 8̃200 | N/A | Brazilian | 274 |

| Cuban son | 2019 | 1,990 | 738 | Salsa, son | 5 |

| and salsa | |||||

| Harmonix | 2019 | 27,360 | 379,065 | Western | 912 |

| Set | pop | ||||

| Sambaset | 2019 | 144,000 | n/r | Samba | 486 |

| Dagstuhl | |||||

| ChoirSet | 2020 | 2,600 | 3,242 | n/r | 20 |

| ASAP | 2020 | 331,200 | 692,633 | Western | |

| classical | 519 | ||||

| piano | |||||

| Acmus‑mir | 2020 | N/A | 10,270 | Bambuco | 337 |

| Salsa | 2024 | 35,488 | 50,511 | Salsa | 124 |

4 Data Preparation

As mentioned above, a stable and reliable dataset with beat‑annotated songs is the basis for developing diverse musical research in salsa music. To create this asset, we engaged in the process of curating and annotating a corpus of salsa music songs. The annotation process took place in four stages: first, songs were selected to span over the period when salsa music has been most active. Second, we held an open “tagathon” session (a collective annotation session) with expert musicians, to obtain three annotation tracks per song. Third, an integration algorithm weighted by the annotator’s precision was employed to convert three beat tracks into a single one for each song. Finally, the resulting beat track was revised and adjusted by expert subjects, if required.

4.1 Dataset

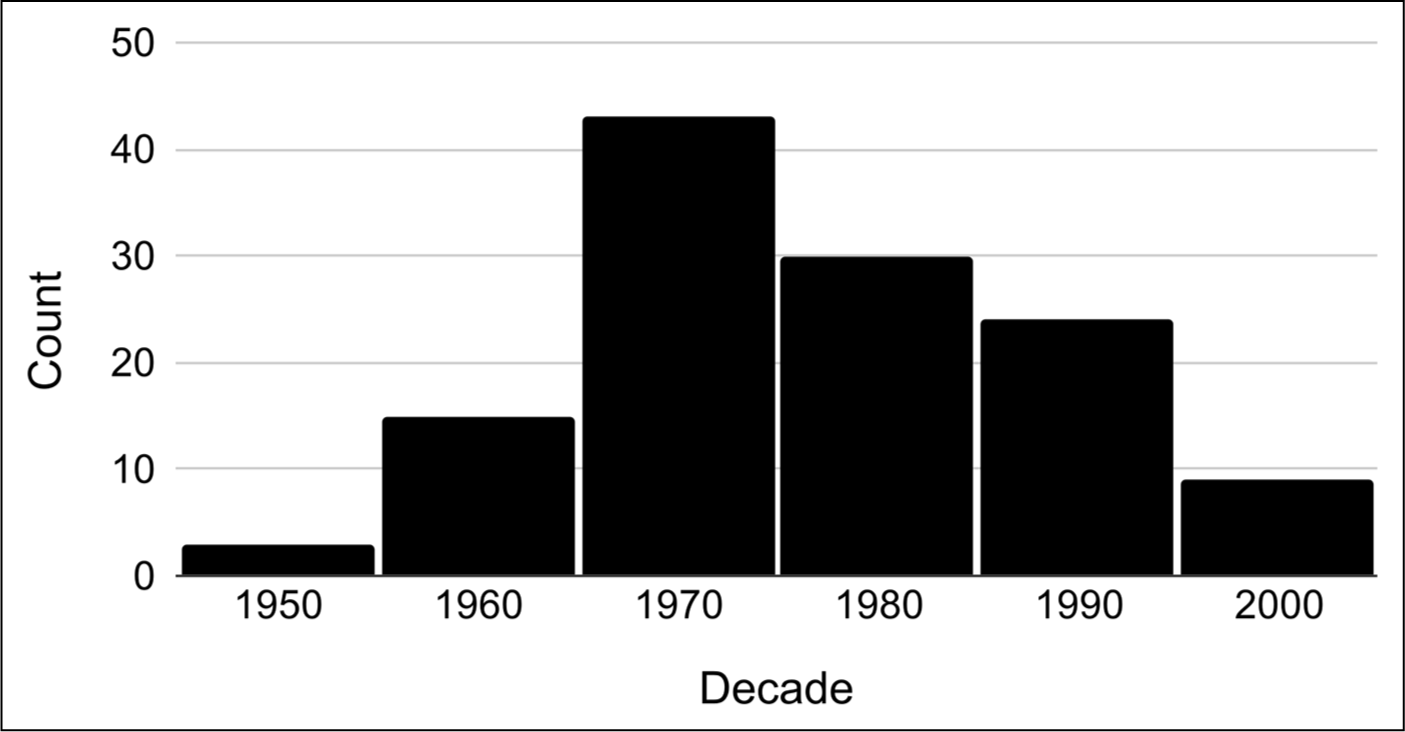

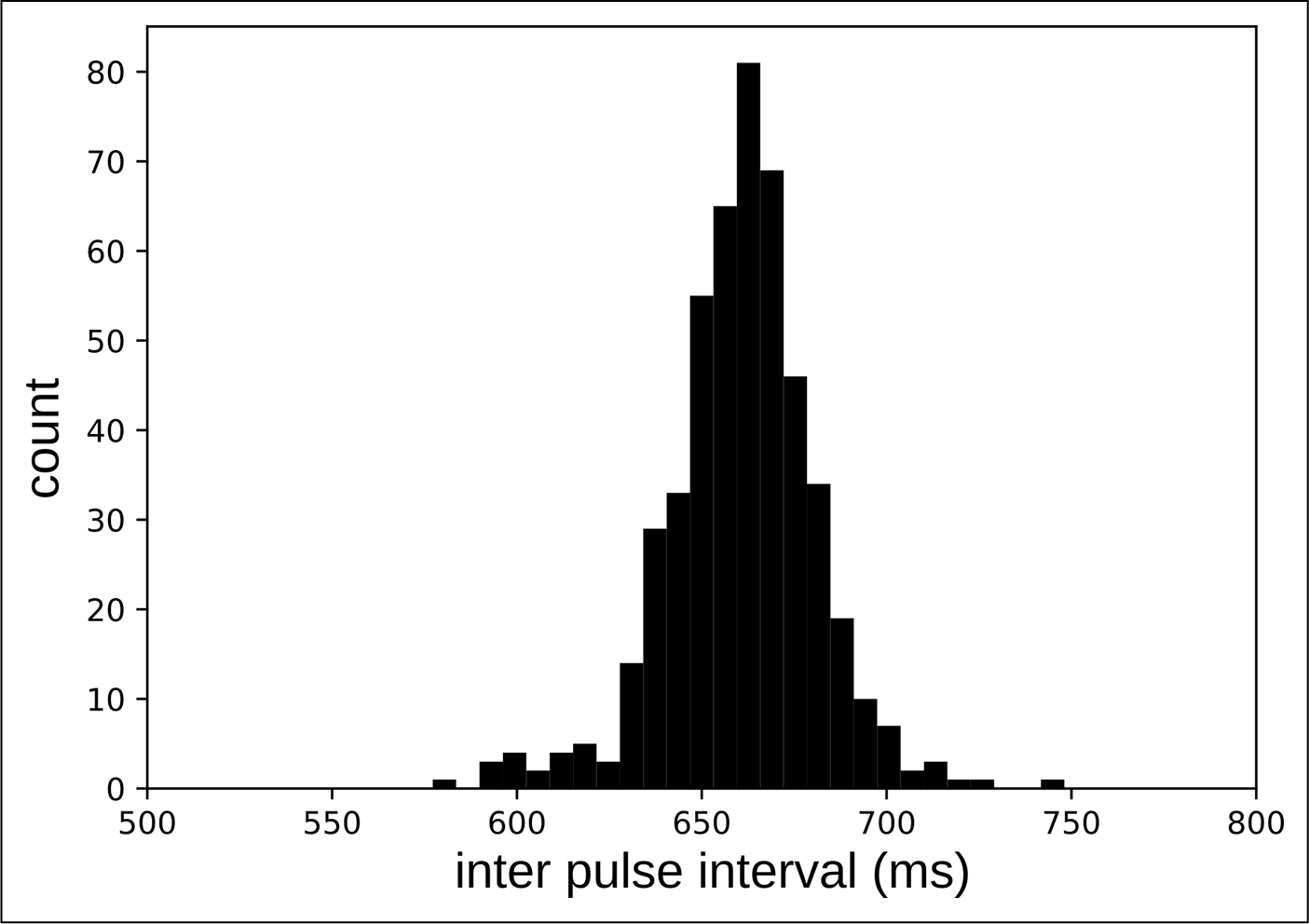

We compiled a dataset featuring 124 songs in .wav format, with a sample frequency of 48 KHz and a bit depth of 16 bits. This dataset encompasses a total audio duration of 9 hours and 52 minutes and includes 49,433 beat annotations. It spans a broad timeframe, covering the active release periods of various salsa subgenres (from the 1950s to the 2000s; Figure 2). All songs in the dataset have uni‑modal behavior for the inter‑beat interval (IBI; Figure 3). That is, songs in the dataset may drift in IBI, given the natural imprecision of human musical performance, but there are no songs with changes nearing double or half tempo. The salsa dataset is available online for the music research community.

Figure 2

Number of songs in the dataset per decade.

Figure 3

Frequency histogram for song 316’s inter‑beat intervals. Note the unimodal distribution.

4.2 Annotation procedure

Custom software was developed for the annotation sessions using the Python programming language.2 This software had two main uses: it first tested subjects for precision (calibration) and then reproduced song after song for subjects to annotate the beat. This software has a client–server architecture: clients run on the subjects’ computers, and a remote server keeps track of the precision evaluations. Once the precision evaluation was over, the server randomly assigned songs for reproduction and annotation on annotators’ (clients’) computers. Finally, after completion, the server received the annotation tracks from the subjects’ client application and sent another track to be annotated. The annotation process required subjects to listen to songs and press the space bar key on their keyboards every time they experienced a beat sensation.

Subjects were recruited from the Music Production Program at Universidad Icesi in Cali, Colombia, a city renowned for its love of salsa music (Hutchinson, 2013). A total of four tagathons were carried out, in which 12 different subjects participated (11 males and 1 female). They had a mean age of 20.8 years (standard deviation of 0.98 years) and an average of 7 years (standard deviation of 4.7 years) studying salsa. Those who attended the tagathons were paid per session and given refreshments during the annotation sessions. The duration of the tagathons varied for each annotator, ranging from 1 to 3 hours.

4.2.1 Three‑expert annotation

Each song selected for the dataset was fully listened to and annotated by three expert subjects in different annotation sessions. Sessions had a maximum duration of 1 hour, during which subjects annotated between 10 and 15 random songs, depending on their duration. At the beginning of each session, and after completing 10 annotated songs, subjects took precision tests, tapping along a sound probe that contained a control salsa loop audio with a quantized rhythm.

The precision test allowed a subject’s attention and tapping accuracy during the session when pressing the space bar key repeatedly to be evaluated against the known beat position of the control audio sample. It has been observed that subjects with higher musical experience tap with higher inter‑tap interval (ITI) precision (Beveridge et al., 2020); therefore, we measured all ITIs made while listening to the control audio, and then consolidated the ITI times in a histogram and computed a kernel density estimation (KDE). The KDE was used as the rating for a subject’s precision and was associated with all the songs annotated during that specific session (i.e., one KDE associated with 10–15 songs).

Once the precision test was over, the server would assign a random song from the dataset, which had not been previously annotated by the subject and that had fewer than three annotations. After the song was fully annotated, a new song would be assigned for processing, with this process continuing until 1 hour of tagging was completed. At this point, subjects were invited to take a break and come back to start the process again: they would re‑take the precision test and then annotate another batch of songs. This process was iterated over four sessions until all the 124 songs had been annotated three times.

4.2.2 Consolidation

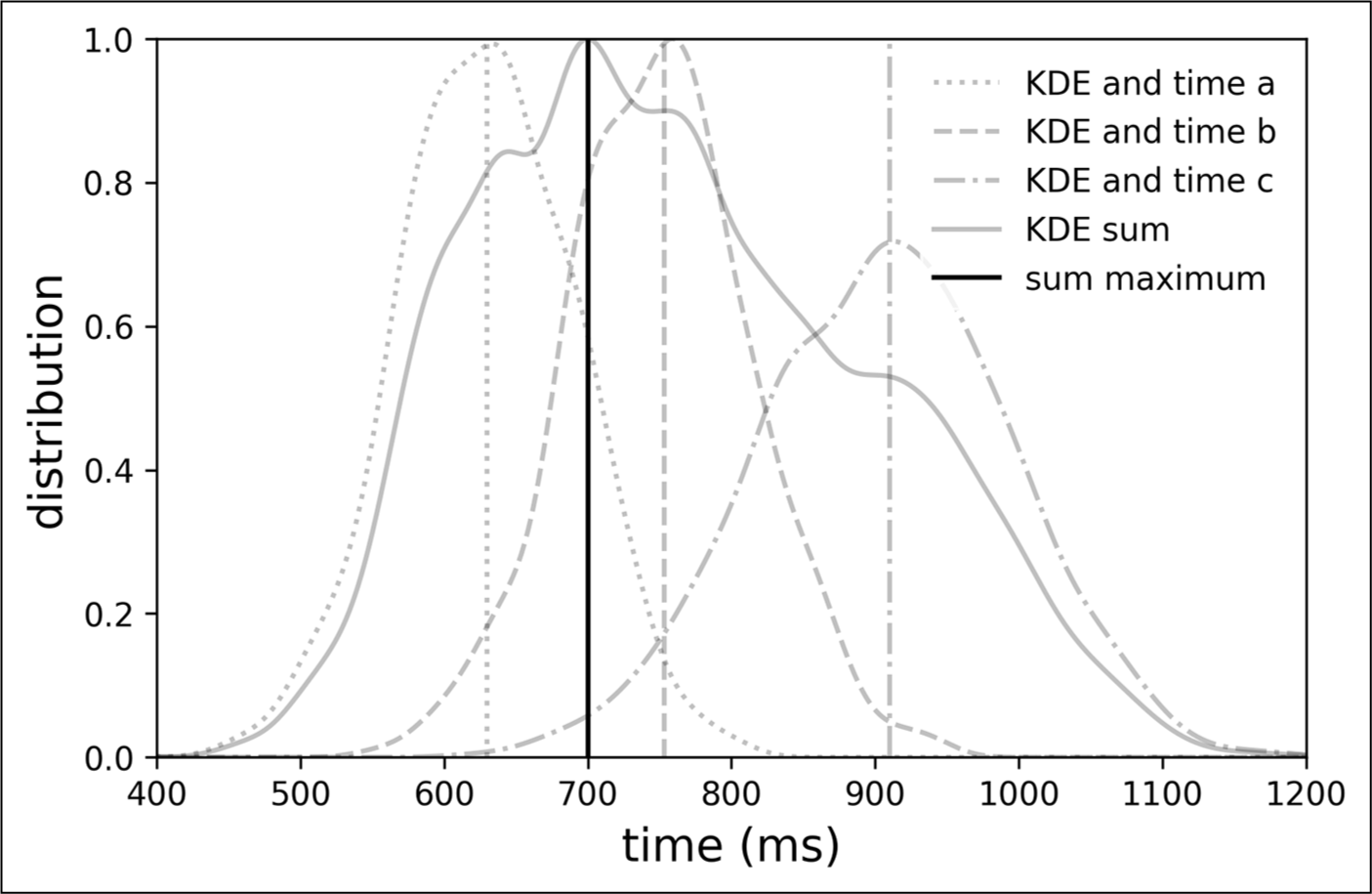

The process of unifying beat annotations from multiple subjects was a crucial step in our methodological approach. As previously mentioned, each annotation provided the temporal locations (in milliseconds) of beat occurrences, as well as the precision KDE recorded at the beginning of the session for the respective subject. We hypothesized that a lower dispersion of the KDE would indicate higher precision, and thus established a rating hierarchy among the three raters of the same song: the sharper the KDE, the lower the intra‑tap interval fluctuation, and consequently, the higher the precision of the subject for the session.

This consolidation approach is taken to minimize possible imprecision caused by fatigue during the tagathon sessions. Although all subjects are experts in salsa music, their precision when tapping on the sound probe would reveal their levels of attention and fatigue due to the repetitive annotation process. Therefore, producing a sharp KDE suggests higher confidence for all the beats annotated during the session.

To consolidate the three annotations into a single, unified representation, we mapped each subject’s KDE around their respective suggested beat times. It was ensured that the maximum value of the KDE coincided with the time proposed by the corresponding rater. Considering the KDE to be a probability density function for each beat annotation, temporal values surrounding all beats annotated by a subject acquire a probability distribution maximized at every beat annotation (see KDEs and times a, b, and c in Figure 4). As there is a temporal proximity of three annotated beats, the areas of the probability density functions (PDFs) of the subjects overlap (see KDE sum in Figure 4). Finally, the three probabilities are summed, and the time with the highest cumulative probability is the final, unified beat time (see sum maximum in Figure 4).

Figure 4

Consolidation of one annotation. Three annotations by subjects a, b, and c and their respective precision KDEs are indicated by gray lines (dotted, dashed, and dash‑dot). The sum of the KDEs is indicated by a continuous gray line. The maximum value of the sum is indicated by a continuous black vertical line.

4.2.3 Expert revision and refinement

In this final refinement stage, custom software was developed and was used by experts to revise and refine the annotations if necessary. Three salsa music experts with music production skills were recruited to carry out this task. The application loads a song and its consolidated annotation and allows subjects to visualize the sound wave and each beat marker and to listen to the original song and a tick sound at every beat occurrence. If a beat marker was missing (not seen and heard) or misaligned with the correct beat position, experts were able to displace the markers and adjust them to the correct position within a millisecond precision. The annotations for the 124 musical pieces were revised and refined using this method. All songs had to be adjusted in at least one beat annotation.

5 The Salsa Dataset

The Salsa dataset is materialized as a folder containing a main file with song information, a sub‑folder with one text file per song with beat annotations in milliseconds, and a sub‑folder containing one mel spectrogram per song. The main file is called “songs and beat data.csv” and presents a song’s basic information. In this file, each row represents a song, and columns contain the following information:

song ID,

song title,

artist,

year of the recording,

name of the recording,

acoustID of the recording.

The beat annotation files are named after a song’s ID (i.e., 73.txt) and contain one beat annotation per row. Mel spectrogram files are also named after a song’s ID number. The dataset is published in the open science library zenodo.org.3 Additional audio material in .wav format will be shared upon request for fair nonprofit research purposes.

6 Beat Estimation in the Salsa Dataset

To assess the value of the salsa dataset, we carried out an analysis using two beat‑estimation models, TCN1 (MatthewDavies and Böck, 2019) and TCN2 (Böck and Davies, 2020). All songs in the salsa dataset were processed by both models, predicting all the beats in each song. To evaluate their performance, the positions of the predicted beats were compared with the annotations of the salsa dataset using the mir_eval library (Raffel et al., 2014; Table 2). To illustrate the challenges brought by the salsa dataset, results of TCN algorithms estimating beats for different classic datasets are presented. It is important to note that the F‑measure scores for these classic datasets have been reported to be improved by fine‑tuning the TCN algorithms (Pinto et al., 2021).

Table 2

Beat estimation performance for classic datasets and the salsa dataset.

| Dataset | TCN | F‑measure | CMLt | AMLt |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ballroom | 1 | 0.933 | 0.881 | 0.929 |

| 2 | 0.956 | 0.935 | 0.958 | |

| Hainsworth | 1 | 0.874 | 0.795 | 0.93 |

| 2 | 0.904 | 0.851 | 0.937 | |

| SMC | 1 | 0.543 | 0.432 | 0.632 |

| 2 | 0.552 | 0.465 | 0.643 | |

| GTZAN | 1 | 0.843 | 0.715 | 0.914 |

| 2 | 0.883 | 0.808 | 0.93 | |

| Salsa | 1 | 0.659 | 0.465 | 0.734 |

| 2 | 0.683 | 0.557 | 0.766 |

As can be seen in Table 2, the salsa dataset has a low performance in all metrics (CMLt: Correct metric level, total accuracy, AMLt: Any metric level, total accuracy) when compared with other classic datasets such as Ballroom, Hainsworth, and GTZAN. Only for the SMC dataset do the TCN algorithms perform slightly below the salsa dataset.

7 Conclusions

Throughout this research, we have expanded currently available music datasets with beat annotations. While there have been recent publications of beat‑annotated Latin American music (Cano et al., 2020; Maia et al., 2018; Maia et al., 2019; Nunes et al., 2015) fostering scientific research on them, there are still major musical strains that have not yet been researched, such as salsa music. Addressing this issue is crucial for the development of a cross‑cultural rhythmic artificial intelligence. We advocate for the broader inclusion of genres, particularly local traditions that exhibit idiosyncrasies beyond popular conventions. Expanding the scope of rhythmic datasets is a necessary step toward the creation of truly expert musical agents. To contribute to this endeavor, our dataset is available online for the music research community.

Our two‑step labeling methodology, although time‑intensive, has proven to be a robust approach for beat labeling in musical signals. Given our detailed methodological description, we believe it can be readily replicated in future musical studies aimed at establishing a solid ground truth for beat estimation.

Evaluating two TCN beat‑estimation models with the salsa dataset shows how current methods can still be improved to produce more accurate beat predictions for salsa music. Therefore, we believe the production of general‑purpose beat detection algorithms can profit greatly from the inclusion of the salsa dataset in their training tasks.

We see beat as an essential element upon which deeper and larger musical analyses (on structure, meter, tempo, tonal constructions, embodiment, etc.) can be carried out. We believe different research areas can profit from this dataset, for example, development of beat estimation algorithms, musicological studies of salsa, music production software, and dance and embodiment studies, among many others. We anticipate that the outcomes of this research, including the salsa dataset, will serve as a catalyst for further explorations into the vibrant tapestry of Latin American culture.

Notes

[1] Brightness has been defined using the mean frequency‑limited spectral centroid above 3 KHz and the ratio of energy over 3 kHz to the sum of all energy above 20 Hz.

[2] The tagging software can be found on a public repository: https://github.com/JesusPaz/tagathon.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to all subjects who participated in the tagathon sessions. Also thank you to Rogger Figueroa, Julián Céspedes, Mateo de los Ríos, Carlos Bonilla, and Margarita Cuellar for their support and opinions during the research process.

Data Accesibility Statement

The code for the annotation software can be found on a public repository: https://github.com/JesusPaz/tagathon. The dataset can be found on Zenodo: https://zenodo.org/records/13120822.

Funding Information

Activity was partially funded by an Universidad Icesi (Cali) grant and the European Union—NextGenerationEU, Ministry of Universities and Recovery, Transformation and Resilience Plan, through a call from the Pompeu Fabra University (Barcelona).

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Author Contributions

Daniel Gómez‑Marín was the main contributor when it came to writing the article, organizing the annotation sessions, and analyzing the dataset. Jesús Paz developed the annotation software and assisted the annotation sessions. Rafael Ospina‑Caicedo and Javier Díaz‑Cely carried out the data analysis, preparing the necessary code and running the beat estimation experiments. Sergi Jordà and Perfecto Herrera co‑supervised the work. All authors actively participated in the study design, contributed to writing the article, and approved the final version of the manuscript.