1 Introduction

In the age of digital transformation, data has become a key asset for communities that improve governance, optimize public services, and drive sustainable local development. Data-based business models offer innovative approaches to use data to create value, optimize resources, and engage audiences. This paper examines the concept of data-based business models as a bundle of innovation strands. The aim is to implement such models in a new governance framework for Swiss municipalities. By analyzing two significant studies and corresponding theoretical frameworks, this paper aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms, challenges, and opportunities associated with data-driven governance.

The scientific examination aims to show how data-based business models in public institutions can act as a key to improve operational efficiency, transparency and decision-making through working out critical success factors, potential obstacles, and opportunities to strengthen innovation and organizational identity through governance, while at the same time solving challenges related to data protection and internal capacity (Ekbia et al., 2015). The study also includes acceptance management of decision-makers and employees in various public institutions to determine their perceptions and experiences in the field of data-based business models. The results are intended to demonstrate both the benefits of such models, but also to demonstrate many concerns about implementation (Cortez et al., 2019). Finally, indications of the need for strategic data alignment and feasible solutions to these challenges for public institutions will be presented (Zuiderwijk et al., 2020).

2 Theoretical Foundation

This analysis examines how public institutions can define data-based business models to increase their performance and increase added value for citizens. Therefore, both technological and organizational aspects need to be taken into consideration. A special focus lies on the adaptation of value-added-driven, which describes activities to enhance the product or service to make it worth more or more desirable in the eyes of the customer, such as energy product portfolios for green electricity, or automated awarding for licences for telecommunication, in distinction to community-oriented elements, which focus on decision making with a strong emphasis on community welfare, such as innovation labs to introduce and promote innovations and to hold community workshops, or digital platforms for public forums, for the creation of a data-based administrative culture.

Data-based business models are characterized by the fact that data plays a central role in value creation. They use data as a key resource to improve products and services, develop new offerings, or optimize processes (Stechow et al., 2022).

There are various approaches to defining data-based business models in the literature. A basic definition describes them as models in which digitized data in different processing stages provide the central added value for customers or consumers (ECLA & Osborne Clarke, 2022).

According to the study, data-driven business models combine two central trends of the digital age with the emphasis on the outstanding importance of (‘big’) data and the increasing focus on ‘data-driven’ conceptual frameworks. Strahringer & Wiener (2021) present such a conceptual framework for data-driven business models. The model includes three main elements: data sources from internal systems to social media to IoT devices, data values obtained through insights from data refinement actions through technologies such as machine learning, and data use for better business processes or services.

The core business is based on data, whereby data orientation can affect all dimensions of the business model – from the value proposition (e.g. a quick and reliable response to a submitted application) to value creation (e.g. digitized processes, data transformation into personalized dashboards) to the revenue model (e.g. subscription-models, data sharing, sponsoring of NGOs). Based on the literature, the following other core components – except from the already mentioned ‘value proposition: What does the organization offer?’ and ‘value creation: How is data used to generate value?’ – of data-based business models can be identified alternately (Dehnert et al., 2021):

Data sources: Where does the data used come from?

Data activities: How is the data processed and analyzed?

Customer interaction: How are the results made available to users?

These components form a conceptual framework can also be transferred to public institutions, as these need to be innovative to meet the citizens’ needs, to define concepts for internal processes, and to conduct organizational transformation. A frequently cited pattern of data-based business models is ‘data as a service’, in which a central organization collects data from users and then offers it as a service (Wang et al., 2020).

It is important to emphasize that while ‘data-based’ and ‘data-driven’ business models are closely related, they differ in nuances. While data-based models use data as the primary function to create new value, data-driven models use data more as a supporting element to optimize existing business processes (Winter, 2017).

The Service Business Model Canvas (SBMC) operationalizes the application of the basic theses and is a further development of the classic Business Model Canvas (BMC), which is specifically tailored to the specifics of service business models. The service sector is also largely responsible for the tasks of public procurement in public administration. It is based on Osterwalder & Pigneur (2010), but expands it to include specific elements that are relevant for a holistic view of services. The nine building blocks (key partners, key activities, key resources, value propositions, customer relationships, channels, customer segments, cost structure, revenue streams) of the classic BMC are retained in the SBMC, but additional aspects are added: customer segments, value propositions, channels, customer relationships, revenue streams, key resources, key activities, key partnerships, and cost structure. SBMC is often used in workshop formats, where interdisciplinary teams work together to analyze and further develop the business model. (Zolnowski & Böhmann, 2014).

Despite its usefulness, the SBMC also has limitations: It is rather static, which means it can only map dynamic aspects of the business model to a limited extent. The SBMC provides a solid foundation for this, which practitioners and researchers alike can use to address the challenges and opportunities of the service economy.

Two elements from this will receive special attention here, as they have a mission-critical effect on data-based business models for public administration services and have particularly high requirements for changed governance.

On the one hand, the key activities should be mentioned here. These are the core activities that an organization must perform in order to deliver its value proposition, maintain its customer relationships, and generate revenue. In the context of the SBMC, key activities include not only operational processes, but also activities that contribute to the co-creation of value with customers.

Zolnowski & Böhmann (2014) identify several categories of key activities that are important for service companies: operational activities, innovation activities, customer-related activities and management activities.

The investigation of key activities in the SBMC is based on a qualitative analysis of case studies and expert interviews. Zolnowski & Böhmann (2014) used the method of the ‘Thinking Aloud Protocol’ to evaluate the application of the SBMC by industry experts. This method made it possible to gain insights into the thought processes of the participants and to evaluate the practicality of the SBMC (Zott et al., 2011).

Another central component of the SBMC is the ‘revenue model’, which is mapped in the ‘revenue streams’ dimension. In contrast to the classic BMC, this dimension is considered separately in the SBMC for all three perspectives: revenues captured by customers, revenues captured by the focal company and revenues captured by partners. This differentiation is intended to make it clear that in service business models, not only the focal company generates revenues, but also customers and partners can potentially participate in the value. Zolnowski & Böhmann (2014) remain relatively vague in their explanations of the revenue model. It is not clearly defined what exactly is meant by ‘revenues captured’. In this case, it would have made sense to link it to established methods of revenue modelling, such as the Revenue Model Framework by Amit & Zott (2001). A promising extension would be the explicit consideration of pricing mechanisms in the revenue model. Innovative pricing models such as ‘dynamic pricing’ or ‘pay-per-use’ play an important role, especially in digital service business models (Hinterhuber & Liozu, 2014).

The concept of value co-creation is central to understanding service business models (Vargo & Lusch, 2008). A stronger theoretical foundation of the revenue model in the SBMC by recourse to the service-dominant logic would be desirable. Many innovative service business models are based on multi-sided platforms. The associated network effects and scaling dynamics should be explicitly mapped in the revenue model (Parker et al., 2016).

Data-based business models are based on the collection, analysis and use of data to create value on a flexible and modular approach. Unlike rigid and monolithic systems, these allow for the integration of different data sources and technologies, allowing organizations to adapt and scale their data initiatives to specific needs and contexts. This flexibility is critical to meeting the dynamic and complex nature of technical environments. These models can be categorized into different types, including ‘data-as-a-service (DaaS)’, ‘data-driven products’, and ‘data-driven services’ (Terzo et al., 2013).

Effective data governance therefore seems to be crucial for the success of data-based business models. The transition from traditional governance models to data-based approaches presents communities with both challenges and opportunities. There are no scientific treatises on special features for Swiss municipalities, so that first definitional approximations are derived on the basis of data-based projects of public services in the D-A-CH area.

According to the Irish Government’s Public Service Data Strategy 2019–2023, which is a global reference, transparency, reuse and governance are central principles for the handling of data in public administration (Office of the Government Chief Information Officer, 2019). This strategy emphasizes the importance of a holistic approach that promotes collaboration between different agencies and the reuse of data.

The term ‘technological activism’ (Staemmler, 2021) in this context refers to the active use and promotion of technology to achieve social, political or economic goals. In public administration, this means the conscious and strategic use of data and technology to improve public services and increase efficiency and transparency. Technological activism also includes the promotion of open data and the creation of platforms that facilitate access to and use of data.

With regard to local data-based management tools, three functional requirements in the political-administrative implementation process seem to be particularly challenging (Aiello, 2023):

Localization of data-based management tools refers to the customization of these tools to the specific needs and requirements of a particular region or administrative unit.

Interpreting data involves analyzing and visualizing data to identify patterns and trends that are relevant to decision-making.

The implementation of data-based management tools often requires changes in the existing processes and structures of public administration.

New opportunities and potentials for data-based governance for improved decision-making and stakeholder engagement, resource optimization and citizen participation can be found in the following case studies:

The Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action (2023) has investigated the potential of municipal open data for the development of business models in the energy industry. The project highlighted the need for clear concepts of organisational governance, data ownership and data maintenance to ensure the success of data-driven initiatives.

The AI4PublicPolicy (2024) project, funded under the Horizon 2020 programme, aims to integrate AI technologies into political decision-making processes. The project adopted the CRISP-DM methodology to develop data-driven strategies involving stakeholders from policymakers to citizens. This approach promoted evidence-based policy-making and facilitated the exchange of models and datasets between authorities.

In conclusion, the definition and implementation of data-based business models is a complex and dynamic field. Continuous adaptation and improvement through feedback loops and data analysis is critical to the long-term success of such models in today’s digital workforce (Hunke et al., 2019).

3 Methodology

In the previous theoretical part, a comprehensive overview of the topic of data-based business models was provided. In the following empirical part, three main research questions will be addressed in more detail by analysing a large number of publications.

3.1 Research Questions

The development of a systematic search for empirical evidence of the theoretical elaboration is intended to lead to knowledge gained with regard to three scientific questions. The research questions aim to investigate the intersection of data-based governance, innovation and organizational identification in the context of Swiss public institutions:

What are the critical success factors for implementing a data-based governance model that promotes innovation and identification in public institutions in Switzerland?

What are the potential obstacles and challenges in the transition to a data-based governance model for Swiss public institutions, especially in terms of innovation and identification?

How can Swiss public institutions effectively align data-drivebased governance with traditional principles of public administration to strengthen innovation and organizational identity?

Thus, the research focuses on various aspects of the implementation and use of data-driven approaches to improve organizational performance and employee engagement.

3.2 Research Methodology

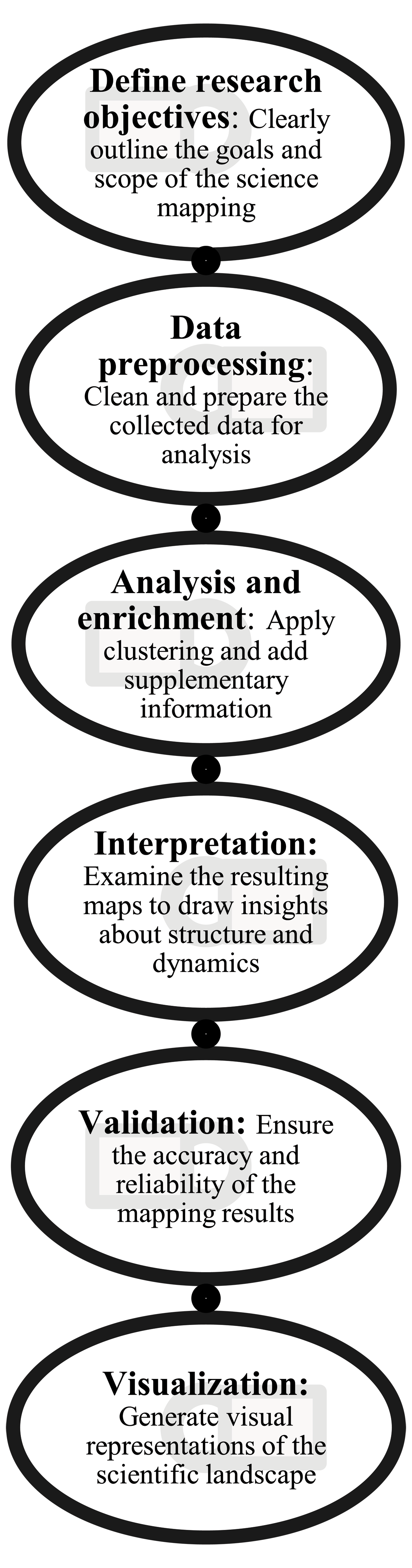

The method of science mapping, structured by the design descriped by Pessin et al. (2023), was used. This approach ensures a comprehensive and transparent synthesis of research results and provides robust evidence for the perceptions and experiences of government staff. The detailed steps on how to proceed in the scientific method are shown below in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Methodological design of science mapping.

The data was collected from a combination of quantitative and qualitative studies, including surveys, case studies and expert interviews. The collected data were analysed using both quantitative and qualitative methods. Quantitative data was synthesized using statistical techniques to identify common trends and patterns. Qualitative data was analyzed thematically to derive insights into employee experiences and perceptions.

However, in order for science mapping to be carried out reasonably, appropriate data quality, suitable tools for data processing and appropriate application knowledge for data analysis should be available (Börner et al. 2015).

The three most commonly used methods are co-word analysis, co-citation analysis, and a hybrid analysis of a composition of the other two analyses. In the present work, the science maps were created using the software CiteSpace and Web of Science™ was accessed. Derived from the idea of co-word analysis, the software looks at the co-frequencies of different elements, such as publishing organizations. For this purpose, the software uses an iteration model that calculates the bibliometric relationships of the co-words.

3.3 Data Source and Data Preparation

In order to deliver the most comprehensive results possible, in addition to the terms ‘data-based business models’ and ‘public administration’, other synonymous terms are included in the search for title, abstract and author keywords. In order to be able to refine the search, the Boole search operator ‘OR’ was used, with which terms with the same meaning can be taken into account in the search. Due to the use of word combinations with the selector ‘empirical data’ etc., the more general term ‘study’, other relevant topics such as eGovernment or artificial intelligence related to public administration were also found. Further restrictions on the databases used or the search period have been waived. The data search was carried out on 27.06.2024 in Web of Science (WoS) and 314 relevant publications were identified. Results should not have been collected before 2020.

The results are prepared graphically in the form of maps or tabular forms and are additionally discussed. For the more detailed analysis of the content in Citespace, semantic networks are created on the basis of ‘disciplines’, ‘keywords’, ‘authors’, ‘organizations’, ‘references’ and ‘research fronts’. To calculate the measure of similarity between two objects, the Jaccard index is used, which can be between 0 and 1. Furthermore, the number of objects for the analyses has been limited. Only those objects that appear in a minimum number of publications were taken into account. In order for an author to appear in the analysis, he or she must have published at least three publications. The final selector ‘language German’ made it possible to reduce the number of objects to be processed to an acceptable level. Due to the differences in the legal systems and the reusability for Swiss municipalities, this regional feature of the D-A-CH region was used.

4 Results and Derivatives

The following passages intend to show the findings and their further development into solutions for further steps for practice and further abstractions in models for the further development of the state of research.

4.1 Empirical Results

Basic scientific research on data-based government models is mainly carried out at universities. Among the top 20 organizations appearing in the WoS are fifteen universities. The document type listed in the WoS is 55% conference proceedings and 36% journal articles.

In WoS, publications can also be divided into WoS categories, which divide the upper research areas into subcategories. The most frequently mentioned are ‘data-based business models’ (31.5%), ‘digital transformation’ (25%), ‘technology and innovation management’ (20%) and ‘digital public governance’ (15%). It should be noted that a publication can also be assigned to several categories. Thus, an accumulation of publications and their authors in a field of research, which often stands out from the rest of the publications due to their frequent mutual citation, created so-called research fronts (Solla Price, 1965). In this respect, qualitatively with regard to the objective was condensed and a TOP 4 number of studies was compiled for further derivations. The studies were selected based on their relevance to the topic and the quality of their methods. The inclusion criteria focused on studies that examined the views of employees in different positions and areas within the public sector on data-based business models.

Limitations arise in the results because the data search for the analysis in Citespace was limited to WoS. For this reason, only data that was available in the database at the time of analysis was included. Furthermore, due to the focus of empirical studies on the German-speaking area, the database research has left numerous publications out of account. During the research, all synonymous terms for ‘data-based business models in the public sector’ used by Wirtz et al. (2023) were also taken into account. However, this led to the fact that publications were also found that had little or no connection to the municipal level. Reference is primarily made to the empirical evidence of the most frequently discussed problems.

The following Table 1 shows findings of the list of case studies for the validation of theoretical research, which is selected as a Top-Level-Listing by the named Validation basis.

Table 1

Basic structure of the SGMC.

| NR. | STUDY | KEY ASPECTS | VALIDATION BASIS |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Müller & Schmidt (2022) |

| Qualitative, semi-structured interviews with executives from 15 public organizations in Germany |

| 2 | Bauer & Meier (2020) |

| Mixed methods survey with open and closed question types in an online survey in an iterative, semi-standardized survey design |

| 3 | Schneider & Weber (2021) |

| Quantitative questionnaire survey with companies dealing with the transition to the use of data based business models |

| 4 | NTT DATA (2023) |

| Quantitative online survey of technical service providers on IT requirements management in the segment of public legal customers |

4.2 Deriving a Service Governance Model Canvas (SGMC)

The SBMC is geared towards commercial applications and hardly takes into account the specifics of non-commercial organizations. In order to adapt the SBMC for use in public authorities and other non-commercial organizations, their specific requirements must first be analyzed. The following core aspects can be considered:

Orientation towards the common good instead of profit orientation: unlike private companies, public authorities pursue the fulfilment of a legal mandate that is intended to serve the common good. A service governance model for public authorities must therefore focus on social benefits, not financial indicators.

Political and democratic control: Authorities are subject to political control and democratic control. Decisions are often not made according to purely business criteria, but must take into account political requirements and social expectations.

Legal framework: Public administrations are bound by strict legal requirements. This applies to the services offered as well as internal processes and structures. A service governance model for public authorities must therefore explicitly take into account the relevant legal framework of public law.

Stakeholder diversity: Authorities must take into account the interests of a wide range of stakeholders – from citizens to companies to other authorities and politicians. A governance model should reflect this stakeholder diversity and offer opportunities to weigh up interests.

Efficiency and cost-effectiveness: even if public authorities do not work profit-oriented in all service areas, they must still act efficiently and economically. A service governance model should therefore take into account aspects such as resource deployment and process optimization according to service areas.

Digitalisation and innovation: many public authorities are faced with the challenge of digitising their services and developing innovative service concepts. A future-proof governance model must support these transformation processes.

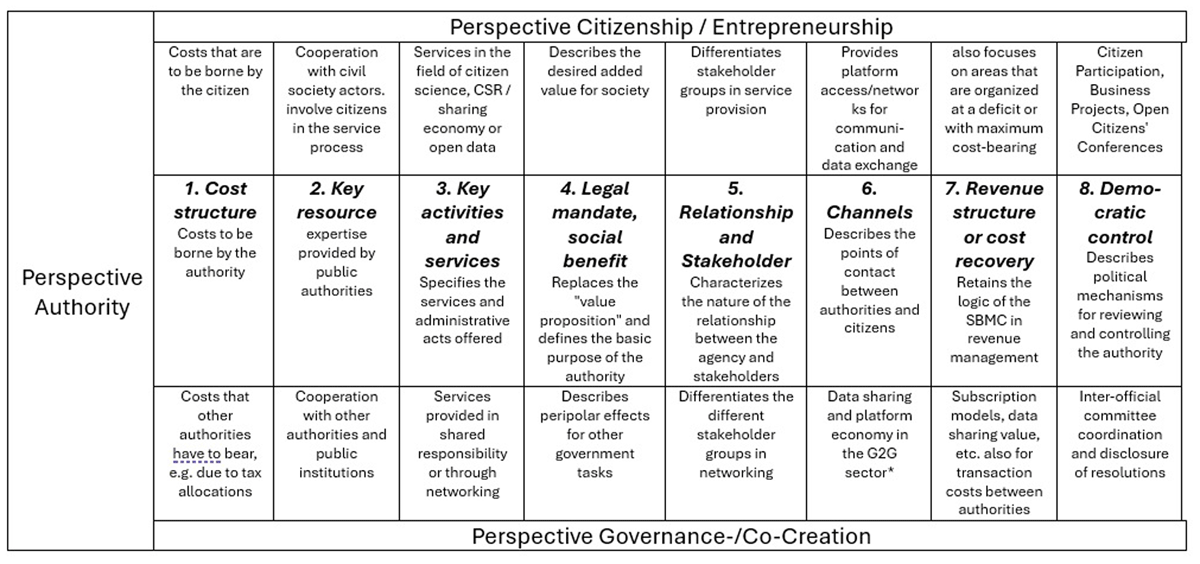

Based on the SBMC by Zolnowski & Böhmann (2014) and the specific requirements of authorities, a proposal for a Service Governance Model Canvas (SGMC) for non-commercial purposes is proposed in the following Figure 2 based on the state of research and the empirically collected requirements. The strengths of the SBMC will be retained and supplemented by authority-specific aspects.

Figure 2

Basic structure of the SGMC.

*G2G-Sector: Governance-to-Governance Areas of Responsibility.

The SGMC can be used in government agencies for a variety of purposes. When analysing existing services, the SGMC helps to take a holistic view of the current service provision and to identify optimisation potential. With regard to the development of new services, this can support the design of innovative administrative services, taking all relevant aspects into account. In strategic planning, the SGMC can serve as a tool for strategy development and communication. Or in stakeholder management, different perspectives can be presented in order to prepare the involvement and coordination with stakeholders.

In an exemplary application, the scenario could serve as an organizational investigation of a digital shared service center for citizen services To illustrate the application of the SGMC, the following is an example of a digital citizen’s office in the categories of the SGMC:

Cost structure: software development, data maintenance, training

Key resources: IT infrastructure, skilled personnel, databases

Key activities and services: Online appointments, digital application, video consultation

Legal mandate, social benefit: Efficient and citizen-oriented provision of municipal administrative services saves time for citizens, conserves resources and increases citizen satisfaction

Relationships and Target Groups: Self-service with support option for citizens, businesses, other authorities

Interaction channels: web portal, app, video conference

Revenue structure or cost recovery: framework agreements, data-sharing agreements with other local authorities

Democratic control: reporting to the city council, citizen consultations

This example shows how the SGMC enables a holistic view of a government service offering while taking into account the specific requirements of public administrations.

4.3 Success Factors for Implementing Data-Driven Governance Models

In order to overcome the challenges mentioned above and to fully exploit the potential of data-based business models in public institutions, various success factors must be taken into account. The following deductions can be made from the theory-driven and qualitatively sound findings:

– A clear data strategy is fundamental to the success of data-driven initiatives. This should define concrete goals and priorities and anchor the role of data in the organization.

– In addition, responsibilities and governance structures must be defined by specifying the implementation of Privacy by Design principles in all digital initiatives and documenting regular audits of data processing activities.

– Ethical guidelines for data use must be established and responsibilities in the event of misuse must be determined with consequences. This includes ensuring non-discrimination in data models, respecting privacy in data analysis, and critically reflecting on potential negative impacts of machine learning with unreflected datasets.

– The involvement of all relevant stakeholders requires targeted communication of the benefits of data-based approaches, the establishment of partnerships with research institutions and companies, and regular evaluation and reporting on progress and results to steering committees.

– Modern technological infrastructure is essential. These include data platforms and data lakes, analysis tools and AI solutions, as well as data interfaces between interoperable specialist procedures. The integration of new digital systems into the existing legacy infrastructure is accompanied by a shift in architecture to cloud-based solutions to reduce data silos and inefficiencies.

– The implementation of data quality management processes is carried out, the standardization of data formats and metadata, the establishment of data governance structures and the development and implementation of data analysis models for data transfer, quality control and visualization.

– Building data competencies at all levels of the organization is crucial in phases of data-based decision-making by executives, data modeling and interpretation by data specialists (data scientists, data engineers, data architects), and data processing in projects in interdisciplinary teams.

– The entry into data-based work should be accompanied by the promotion of a data-driven culture throughout the organization. Among other things, recognition and reward systems for early adopters and champions of change as well as multipliers to promote knowledge exchange should be introduced.

4.4 Additional Application and Implementation Requirements

Organizational infrastructure transformation requires a systematic, multi-phase approach. To begin, a thorough assessment of the existing infrastructure is required. On this basis, a roadmap for infrastructure upgrades should be planned, taking into account both short-term and long-term needs of interoperable data management. In the implementation phases of new architectures, phased implementation is recommended to minimize disruption and allow for customization. By modernizing and replacing legacy systems, data porting to cloud platforms is unproblematic and the desired flexibility and scalability is achievable. Finally, tools and processes for ongoing performance monitoring and optimization should comply with systemic quality assurance standards.

Collaborative data ecosystems, in which data is shared across organizational boundaries, require new governance models, after all, investments in data partnerships and ecosystems are becoming more relevant (Otto et al., 2019).

The principle of earmarking is of particular importance. Data may only be collected and processed for pre-determined, explicit and legitimate purposes. This can lead to conflicts, especially in big data analyses and AI applications, as it is often only possible to see what insights can be gained from the data in retrospect. Questions of data ownership and data portability are also becoming increasingly relevant. In many cases, there is a lack of clear legal regulations here, which leads to uncertainties (Thouvenin et al., 2019). The planned EU regulation on a framework for the free flow of non-personal data could also be applied to Switzerland on the basis of the model.

The development of data-based business models also requires new approaches to system design. Traditional methods often reach their limits in view of the complexity and dynamics. Instead, agile and user-oriented approaches are gaining importance (Josuttis, 2015).

Design Thinking has established itself as a promising method for developing innovative data-based solutions. The approach combines creative and analytical elements and focuses on the user. Through iterative prototyping cycles, ideas can be quickly tested and refined. Another relevant approach is the concept of Minimum Viable Data Products (MVDP). Analogous to the minimum viable product in software development, the aim is to start with a minimum data set and expand it step by step. This makes it possible to obtain feedback at an early stage and to align development with actual needs.

There’s also an increase in using data-driven design methods. Here, user data is systematically included in the design process in order to make decisions and optimize solutions. A/B testing and other experimental formats play an important role in this.

Various studies have examined how and why public institutions implement these models and what the associated challenges are.

The study by Matthias Söllner et al. (2018) identifies changing requirements for system design in information technology (IT) and how these requirements can be formulated and implemented within the framework of Design Thinking processes. Traditional design approaches often deliver inconsistent requirements, measured by the importance of user experience and user needs in rapidly changing technological and social contexts. The authors call for further research to identify the best practices for the application of Design Thinking in IT system design.

Tumbas, Berente and vom Brocke (2018) emphasise the role of public institutions as data brokers and the importance of the role of the Chief Digital Officer (CDO). Through qualitative analysis of 30 global companies, they examine various data strategies of CDOs from ‘harmonizers’ to ‘utilizers’ and emphasize the need for public institutions to change the way they collect, store and use data to maximize the value of data-based management.

Paroutis, Bennett and Heracleous (2014) discuss the development of smart cities technology in public institutions, such as public safety or health services, using an interactive framework for strategy practice. They identify types of flexible and adaptable strategies and underline the need for public institutions to methodically address changing technological landscapes.

Especially, further research should focus on the use in real public cases in different empirical validation scenarios Some transfer to a usecase for practice is described in Magalhaes & Roseira (2020).

Conclusion

The use of data-based business models in public institutions differs in some aspects from the application in the private sector. While companies are primarily focused on maximizing profits, public institutions focus on the common good. The implementation of data-based approaches offers Swiss municipalities a wide range of opportunities. More efficient decision-making through systematic analysis of data enables decision-makers to make informed decisions and allocate resources optimally. Municipalities can meet the increased requirements for transparency in the Confederation by disclosing data and analyses, so that citizens’ trust in state institutions is strengthened. Data-driven services also make it possible to align citizen services more specifically with the needs of citizens. In addition, data analyses can make administrative processes more efficient and save costs by enabling innovation, e.g. through the provision of open data, to enable new cooperation models.

Despite the potential, public institutions face specific challenges and barriers when implementing data-based business models. In addition to the data protection of sensitive citizen data, regulations must be developed in the form of a data policy. In many places, interoperability between authorities still needs to be designed, and there is often a lack of specialists with the necessary data skills. After all, an innovation-friendly organizational culture for digital governance approaches still poses major acceptance challenges for many public institutions.

The development of the Service Governance Module Canvas (SGMC) based on the SBMC by Zolnowski & Böhmann (2014) thus represents an important step towards the transfer of modern service management concepts to the public sector. By taking into account authority-specific requirements such as orientation towards the common good, political control and legal frameworks, the developed SGMC enables a differentiated analysis and design of public services.

Future research in this area should address further questions related to necessary competencies in the field of data ethics, security and modelling. Challenges of digital transformation in public authorities go hand in hand with questions of implementing and operationalizing data management. The empirical validation of the governance models of administrative practice and their concrete operationalization of goals and outcome measurement should be collected. The SGMC presented is based on theoretical considerations and needs to be tested and validated in practice. This requires case studies in various authorities and administrative levels and also internationally.

Future research could also focus on the further development of the SBMC with regard to, for example, regulations such as the EU Data Act, in order to better map dynamic aspects and improve integration with other strategic tools.

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.