1 Introduction

In 2023, diversity and inclusion are hot topics within the Swiss public sphere. However, these issues are discussed more intensively in public not because diversity is celebrated but because of discrimination based on race, ethnic origin, religion, language, gender, sexual orientation, age, and so on (Hapig, 2022). In 2021, almost one-third of people in Switzerland reported being a victim of discrimination in the past five years. The most common reasons are nationality, language, or gender (Federal Statistical Office, 2021).

One player that can contribute to counteracting discrimination is the public school. This potential is acknowledged by the Swiss-German Conference of Cantonal Ministers of Education (D-EDK) as they state the following in their joint curriculum for public schools in the German-speaking part of Switzerland:

‘Schools make a significant contribution to integrating children and young people from different social, linguistic and cultural backgrounds, thereby supporting peaceful coexistence.’

And further:

‘It is part of the school’s task to promote equality for pupils in everyday school life so that they can develop their personality and potential as freely as possible from attributions of certain characteristics and behavior based on their gender. As a cross-curricular topic and interdisciplinary competence (dealing with diversity), equality flows into all subject areas.’ (Deutschschweizer Erziehungsdirektoren-Konferenz, 2017)

However, public schools have not yet implemented these goals. It is striking that the word ‘racism’ is not even mentioned in the Curriculum 21. The Curriculum 21 harmonizes elementary and lower secondary school in the 21 German-speaking cantons of Switzerland as a joint curriculum. We argue that there is a lack of knowledge on how to implement the goals set in the Curriculum 21. Our study sets out to fill this gap and develop a lesson plan for public schools to promote anti-discriminatory behavior among students.

One approach to do so is Anti-Bias Education (ABE) (e. g. Bartoş et al., 2014; Derman-Sparks, 1989; Panesar, 2022; Winkler, 2009; Yu, 2020). ABE, as a pedagogical concept, aims to reduce discrimination. While the impact and implementation of ABE have been broadly discussed in literature, the majority of this research is dedicated to early childhood education (Doucet & Adair, 2013; Yu, 2020). These studies report a positive impact of introducing topics on race and sexuality at an early age. It seems crucial to continue this discussion at the secondary level where currently there is a lack of studies on implementing ABE. This study contributes to further exploring the research on applying an anti-discriminatory behavior stance to education at the secondary school level. Furthermore, it offers a practical contribution by developing a lesson plan that implements the Curriculum 21’s goals on discrimination. Therefore, it attempts to fill the research-practice gap on this topic. More specifically, this research is dedicated to shedding light on how ABE lessons can be designed to have a positive impact on students’ attitudes toward race and sexual minorities. To achieve this goal, this study sets out to answer the following research question:

What are promising pedagogical considerations that could be included in an ABE lesson plan for a Swiss secondary-level class?

To answer this research question, a literature review was carried out. Based on these findings, a lesson plan was developed. This lesson plan was tested with a secondary-level class in Bülach, Switzerland. Using participant observation, qualitative data was gathered to make suggestions for creating a lesson plan to increase secondary-level students’ awareness of discrimination.

This study is structured as follows: Chapter 2 provides an overview of the current body of knowledge dealing with anti-discriminatory behavior and the role public schools have in this context. Chapter 3 describes the methodological approach. Chapters 4 and 5 present and discuss the results for literature and practice, elaborating on ways to incorporate anti-discriminatory behavior lesson plans effectively in secondary schools. The study concludes with an answer to the research question as well as discussing the limitations and suggesting possibilities for future research.

2 Theory

After defining and discussing the core concepts of this study, this section presents an overview of the theoretical background of discrimination and discusses the current body of knowledge dealing with ABE’s potential for schools to raise awareness among students regarding anti-discriminatory behavior.

2.1 The concept of discrimination

In Switzerland, the Federal Constitution states in Article 8 that all people are equal before the law, and later in the same article, that discrimination is prohibited. Specifically, the law states that no one may be discriminated against based on their origin, race, gender, language, religion, or way of life (§8 para. 2 of the Federal Constitution of the Swiss Confederation of 18 April 1999). According to the Swiss Federal Statistical Office, however, self-reported discrimination has increased in recent years. In 2010, around 15 percent of the Swiss population reported being victims of discrimination. This figure rose to almost 30 percent in 2020. When asking people (N = 3258) how they perceive discrimination, most mention nationality (55.6%), language (35.3%), and gender (26.6%). Further, the report states that 15.7% feel victimized due to their skin color and 9.2% due to their sexual orientation. Between 2016 and 2020 these figures increased sharply (Federal Statistical Office, 2021).

To fully understand what these figures mean, the term discrimination needs to be defined. The word discrimination stems from the Latin word discrimino, which can be translated to ‘make distinctions, discern differences, to separate or categorize’ (Hálfdanarson & Vilhelmsson, 2017). Discrimination as a concept appeared in the early seventeenth century, while the term only acquired a negative connotation in connection with racial discrimination in 1860. Nowadays, different scholars use different definitions of the term discrimination, depending on their research field (Hálfdanarson & Vilhelmsson, 2017). For this study, the definition of the Swiss Federal Office is being used, as their data on the topic was presented earlier. They define discrimination as ‘actions or practices that discriminate against, humiliate, threaten or unjustifiably endanger the integrity of persons on the basis of characteristics such as appearance, ethnicity, religion or gender.’ (Federal Statistical Office, 2021).

Scherr et al. (2017) indicated in their discussion about the meaning of the concept of discrimination that the term should be interpreted in an interdisciplinary way in order to fully grasp it. First, from a legal perspective, discrimination is understood as not illegal unequal treatment per se, but instead inquires of which forms of discrimination can be politically and legally justified, and which ones cannot. Second, from a historical and social-scientific point of view, it is noted that discrimination is not only the consequence of disadvantageous actions but a complex social phenomenon. As a social phenomenon, discrimination can be structural, institutional, or individual.

According to the work of Pincus (1996) on different forms of discrimination, these three levels of discrimination can be described as follows: Structural discrimination is a form of unequal treatment that is created through the policies of the dominant group in a state that treats their own group differently or has a different effect on the minority groups. Institutional discrimination refers to unequal treatment that is committed by state institutions (e.g. public schools). Individual discrimination, on the other hand, is linked to the behavior of individual members of society that exerts negative effects on members of different social groups.

2.2 Schools’ role in reducing discrimination

In Switzerland, the Swiss-German Conference of Cantonal Ministers of Education (D-EDK) developed the so-called ‘Curriculum 21’. With this joint curriculum, the D-EDK harmonized the goals of the mandatory public schools in 21 German-speaking cantons (Deutschschweizer Erziehungsdirektoren-Konferenz, 2017). One of the goals formulated in the Curriculum 21 is that public schools promote ‘mutual respect in living together with other people, especially with regard to cultures, religions and ways of life’ and further, that public schools teach students to ‘respectfully deal with people who have different learning different learning conditions or differ in gender, skin color, language, social origin, religion or way of life’ (Deutschschweizer Erziehungsdirektoren-Konferenz, 2017).

However, a report by the Federal Commission against Racism (FCR) clearly states that this goal has not yet been achieved. In this report, Scherrer and Ziegler (2016) state that the term ‘racism’ – or any of its synonyms – is not included in the Curriculum 21’s lesson plan. Furthermore, they mention that when looking at the curricula of different universities of education, there are no courses on the topic either. Therefore, neither do schools include the sensitization to various forms of discrimination in their curriculum, nor are teachers trained to raise awareness of discrimination among their students (Scherrer & Ziegler, 2016). It seems that the need and potential of schools to sensitize students against discriminatory behavior is recognized, but currently not thoroughly implemented.

Drawing on these findings, we argue that there is a lack of knowledge on how schools can fulfill the goals set by the Curriculum 21 and contribute to reducing discriminatory behavior amongst students. Focusing on developing lesson plans for students, our study searched for pedagogical concepts that have proven successful in this area. In literature, the most referenced concept is ABE.

2.3 Anti-bias education (ABE)

Derman-Sparks (1989) is widely seen as the originator of anti-bias approaches. She both defined ABE, as well as gave inputs for possible implementations. While biases were mostly associated with racial biases in the beginning, it soon became clear that other biases had to be challenged with ABE too. Already Derman-Sparks (1989) saw the duty of ABE in ‘challenging prejudice, stereotyping, bias, and the isms’ (p. 3). The inclusion of other biases such as sexism, ableism, or weightism sets ABE apart from the anti-racist movement within anti-racist curricula (Godley et al., 2020; Schick & Denis, 2005).

Ideas for implementing ABE in classrooms can be diverse. Although there are numerous studies pointing out general ways of proceeding, few can be found that give more concrete ideas for classroom activities. According to Derman-Sparks and Edwards (2019), anti-bias activities in school come from three main resources: the children’s own questions and thoughts, teacher-initiated activities, and significant events that occur in the students’ communities. They suggest that whenever there is a situation arises that’s worth discussing with regard to bias awareness, educators should implement a short intervention. Equally important, on the other hand, is to plan certain activities that will help students to deal with their biases in the future. When addressing a critical situation that occurred in the classroom, Winkler (2009) underlined the importance of discussing the issue in a concrete way and allowing students real participation. Winkler (2009) further elaborated that when confronting students, teachers should avoid using vague statements, such as ‘hurting feelings’ or ‘being mean’.

Research in ABE has been carried out mostly in the field of primary education or even early childhood education (e. g. Derman-Sparks & Edwards, 2019; Escayg, 2018; Robinson & Jones-Diaz, 2006; Vandenbroeck, 2007). The extent to which the findings are applicable to secondary education is part of this study.

3 Methodology

This chapter provides a comprehensive overview of the research design and methodology employed in this study. It outlines the setting of the study, the process of elaborating the lesson plans, and the method of participant observation during the conduction of lessons.

3.1 Research design

This paper adopts a practical research design, focusing on the development and evaluation of a lesson plan based on ABE principles to raise awareness of racial and sexual minorities among secondary-level students. We chose to focus on discrimination based on skin color and sexual orientation, as these are among the most common causes of discrimination according to the Swiss Federal Statistical Office. The verification of the lesson plan is exploratory in nature, providing specific elements that might be promising to implement in future lesson plans. To gather data from the conducted lessons, participant observation as a qualitative method was chosen.

The four lessons were conducted within a period of four months. Each lesson lasted roughly 45 minutes. The central part of each lesson consisted of a sequence of interventions. Each intervention, moreover, was composed of an activity followed by a discussion. We were observing and participating in the interventions at the same time, in order to guide the discussion and ask critical questions. The four lessons were devoted to discrimination in general or – more importantly – either discrimination based on skin color or sexual orientation.

3.2 Elaboration of the lesson plans

The lesson plans were developed drawing on insights from the original research and relevant literature on ABE, specifically the work of Derman-Sparks (1989).

The lessons were designed to challenge students’ prejudices and promote a more inclusive and accepting classroom environment, in line with the principles of ABE. The main outline of the content was planned in advance. The detailed lesson structure, however, did not follow a predetermined plan, but was developed iteratively based on the experiences and insights gained from each lesson. This approach allowed for the lessons to be responsive to the dynamics of the class and the specific needs and experiences of the students.

In developing the lesson plans, we drew on the three main resources for anti-bias activities in school as identified by Derman-Sparks and Edwards (2019): the children’s own questions and thoughts, teacher-initiated activities, and significant events that occur in the students’ communities. The lessons were designed to be interactive and participatory, encouraging students to share their thoughts, ask questions, and engage in discussions. We also took into account the importance of discussing issues in a concrete way and allowing students active engagement and real participation, as emphasized by Winkler (2009).

Given the study’s focus on discrimination against lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, and asexual people (LGBTQIA) and People of Color (PoC), we incorporated specific strategies to tackle these topics. For instance, we considered the findings of Bartoş et al. (2014), who concluded that the most effective approach to challenging sexual bias is the manipulation of social norms. In our study, we decided to include short videos that show the perspectives of the minority group. This kind of intervention is also in line with the findings of Burk et al. (2018) who showed the effectiveness of media-based interventions in reducing homophobic and verbal discrimination.

In addressing discrimination based on skin color, we drew on the recommendations of Darling-Hammond (2017)and Magno et al. (2022)emphasizing the importance of building sustainable relationships with students and engaging in practices of anti-racist pedagogy. Specifically, we included activities where students reflected on personal experiences of racism and expressed their own identity in racial, ethnic, and cultural terms.

3.3 Data collection

The class consisted of 13 students from diverse backgrounds, providing a rich context for implementing and evaluating the lesson plan. Being an 8th-grade class, all students were between 14 and 15 years old, with eight identifying as male and five as female.

We used the participant observation approach to collect data in the form of field notes. According to Ary et al. (2010, p. 459), the teacher can witness the ‘naturally occurring behavior within a culture or entire social group.’ Angrosino (2007) described participant observation in education as a method where teachers become ethnographers within their classroom, which was precisely the goal of this study.

Measuring student engagement is a challenging task (e. g. Fredricks & McColskey, 2012; Skinner et al., 2008; M.-T. Wang et al., 2016). It offers important insights and objective data, however, which educators otherwise could not assess. It allows retracing certain attitudes over a long period of time. Erdogan et al. (2011) developed an instrument to monitor student-centered actions in science classrooms. The result was the student actions coding sheet (SACS), consisting of a protocol sheet, where observers can mark the number of occurrences of specific actions, for example, when a student asks a question. Although the SACS was intended for science classes, the tool was adapted and changed to use for this study to assess the students’ behavior and actions during the ABE lessons. The resulting SACS consisted of seven different student actions shown in Table 1.

Table 1

SACS template.

| STUDENT SHOWING DISAPPROVAL ABOUT ACTIVITY | STUDENT DEMONSTRATING EXCITEMENT ABOUT ACTIVITY | STUDENT SHARING IDEAS WITH THE TEACHER | STUDENT SHARING IDEAS WITH OTHER STUDENTS | STUDENT RESPONDING TO TEACHER QUESTIONS | STUDENT ASKING QUESTIONS TO THE TEACHER | STUDENT ASKING QUESTIONS TO OTHER STUDENTS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Student 1 | |||||||

| Student 2 | |||||||

| … | |||||||

| Student 13 |

3.4 Data analysis

The results from the SACS were analyzed descriptively using R. For the analysis of the field notes, we conducted a qualitative data analysis with the software MAXQDA. Tools for coding and creating concepts and categories allow an in-depth computer-assisted text analysis suitable for this study. The codes were given inductively using the constant comparative analysis technique (Kolb, 2012). Coding was done using open, axial, and selective phases following the procedure suggested by Corbin and Strauss (2008). Open coding is done closely with the text while many different codes are assigned. During axial coding the codes are categorized through relationship identification. Finally, coding is done selectively, ignoring concepts with no or little significance to the core. The whole procedure was done by one researcher as this approach offers advantages in terms of reliability and time efficiency (Olson et al., 2016). After the three coding steps, 20 codes grouped into three categories emerged (see Appendix: Code system with examples). The list is provided with text examples from the field notes.

4 Results

This chapter is dedicated to sharing the lesson plan and the data from the participant observation.

4.1 Lesson plans

The lesson plans showed how they were taught. Each lesson is divided into different sequences, so-called interventions.

Table 2 presents the first lesson containing interventions about biases and prejudices in general, as well as a first glance at sexual and racial biases specifically.

Table 2

Lesson 1 – Introduction.

| TIME [MIN] | CONTENT, LEADING QUESTIONS | OBSERVATIONS, DATA COLLECTION | DIDACTIC CONSIDERATIONS |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0–5 | Introduction: What is prejudice? | Students type in their ideas on mentimeter. Directly over mentimeter. After the exercise, the result will be saved. | This activity encourages students to reflect on their understanding of prejudice, which is a crucial first step in addressing biases. |

| 5–10 | What are typical stereotypes about Swiss people? | Students type in their ideas on mentimeter. Directly over mentimeter. After the exercise, the result will be saved. | This activity helps students to recognize stereotypes in their own environment, which can make the concept of bias more relatable. |

| 10–15 | What are typical stereotypes about your home country? | Students type in their ideas on mentimeter. Directly over mentimeter. After the exercise, the result will be saved. | This activity allows students to reflect on their own experiences with stereotypes, which can foster empathy for others who face bias. |

| 15–25 | Watching an interview with a black Swiss and the stereotypes he is exposed to. | Students react in an open discussion. Noting the answers of the representing students. Sharp opinions or points of particular interest are noted too. | This activity exposes students to real-world experiences of bias, which can make the issue more tangible and urgent. |

| 25–35 | Watching a documentary about hatred against gay people in Switzerland. | Students react in an open discussion. Noting the answers of the representing students. Sharp opinions or points of particular interest are noted too. | This activity provides students with a broader context for understanding bias, which can help them to see the systemic nature of the problem. |

| 35–45 | Students fill out a multiple-choice sheet. The questions are about their perceived prejudice towards themselves and towards others (concerning race and sexuality). | Sheets are collected and evaluated regarding their group affiliation. | This activity gives students an opportunity to reflect on their own biases, which is a crucial step in the process of change. |

Table 3 shows lesson 2 dealing with racial biases.

Table 3

Lesson 2 – Racism part of our culture?

| Time [min] | Content, Leading Questions | Observations, Data Collection | Didactic Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0–5 | Introduction: What is racism? | Students type in their ideas on mentimeter. Directly over mentimeter. After the exercise, the result will be saved. | This activity encourages students to define racism in their own words, which can help them to better understand the concept. |

| 5–10 | Is there racism in Switzerland? If so, where? | Students type in their ideas on mentimeter. Directly over mentimeter. After the exercise, the result will be saved. | This activity encourages students to identify instances of racism in their own environment, which can make the issue more relatable and urgent. |

| 10–15 | Have you ever felt, that people are racist towards you? | Students type in their ideas on mentimeter. Directly over mentimeter. After the exercise, the result will be saved. | This activity allows students to share their own experiences with racism, which can foster empathy and understanding among the class. |

| 15–25 | Watching an interview with a black German and the stereotypes he is exposed to. | Students react in an open discussion. Noting the answers of the representing students. Sharp opinions or points of particular interest are noted too. | This activity exposes students to the real-world experiences of individuals who face racism, which can make the issue more tangible and urgent. |

| 25–35 | Watching the short film ‘Schwarzfahrer’. Discussing the meaning behind it. | Students react in an open discussion. Noting the answers of the representing students. Sharp opinions or points of particular interest are noted too. | This activity uses a creative medium to explore the issue of racism, which can engage students on an emotional level and foster deeper understanding. |

| 35–45 | Grouping the students according to different principles, skin tone being one of them. | Noting the answers of the representing students. Sharp opinions or points of particular interest are noted too. | This activity encourages students to reflect on the arbitrary nature of racial categorizations, which can challenge their existing beliefs and assumptions. |

Table 4 presents lesson 3 where the students dealt with biases against LGBTQIA people.

Table 4

Lesson 3 – Biases against LGBTQIA.

| TIME [MIN] | CONTENT, LEADING QUESTIONS | OBSERVATIONS, DATA COLLECTION | DIDACTIC CONSIDERATIONS |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0–5 | Introduction: What is homophobia? | Students type in their ideas on mentimeter. Directly over mentimeter. After the exercise, the result will be saved. | This activity encourages students to define homophobia in their own words, which can help them to better understand the concept. |

| 5–10 | Is there homophobia in Switzerland? If so, where? | Students type in their ideas on mentimeter. Directly over mentimeter. After the exercise, the result will be saved. | This activity encourages students to identify instances of homophobia in their own environment, which can make the issue more relatable and urgent. |

| 10–15 | Have you ever experienced homophobia in public? | Students type in their ideas on mentimeter. Directly over mentimeter. After the exercise, the result will be saved. | This activity allows students to share their own experiences with homophobia, which can foster empathy and understanding among the class. |

| 15–27 | Watching an interview with a group of gay men and the stereotypes they’re exposed to. An important point they mention is the difference between opinion and discrimination. | Noting the answers of the representing students. Sharp opinions or points of particular interest are noted too. | This activity exposes students to the real-world experiences of individuals who face homophobia, which can make the issue more tangible and urgent. |

| 27–35 | Showing a PowerPoint presentation with celebrities and letting the students guess, who is LGBTQ and who’s not. Observing their reaction. | The students additionally fill out a survey where they have to guess between ‘not LGBTQ’ or ‘LGBTQ’ for each celebrity. Answers collected from the online survey. Noting the answers of the representing students. Sharp opinions or points of particular interest are noted too. | This activity challenges students’ assumptions about sexual orientation, which can help them to recognize and question their own biases. |

| 35–45 | Mentimeter: Would it bother you if a friend of you came out as gay? Discuss the opinions. | Noting the answers of the representing students. Sharp opinions or points of particular interest are noted too. | This activity encourages students to reflect on their own attitudes towards homosexuality, which is a crucial step in the process of change. |

Table 5 shows the last lesson, that was shortened to about 20 minutes as it just worked as the recap.

Table 5

Lesson 4 – Recap.

| TIME [MIN] | CONTENT, LEADING QUESTIONS | OBSERVATIONS, DATA COLLECTION | DIDACTIC CONSIDERATIONS |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0–5 | Question: Where do Prejudices occur? | Students type in their ideas on mentimeter. After the exercise, the result will be saved. | This activity allows students to reflect on their own experiences and perceptions of where prejudices occur, fostering critical thinking. |

| 5–10 | Question: What is your relation to prejudices? | Students type in their ideas on mentimeter. After the exercise, the result will be saved. | This activity encourages self-reflection and helps students to identify and acknowledge their own biases. |

| 10–20 | The students will do the same survey from intervention 1 again. | The answers will be saved in the online survey. | Repeating the survey allows for the assessment of any changes in students’ attitudes and perceptions following the interventions. |

4.2 Lesson evaluation

To evaluate the different lessons, we examined the codes stemming from field notes and the data collected with the SACS.

First, we were looking into the codes resulting from the field notes. They were visualized using network graphs and MAXQDA’s tool codeline. To create the network graphs, we used a method called classical multidimensional scaling (J. Wang, 2012) which will be described in the following paragraphs.

The first step is counting the number of events that two different codes overlay. The larger this number, the more similar the codes are. By choosing any amount of codes and putting them in a table as rows and columns, a matrix is created with the cells containing the “overlay numbers”, i. e. the intersection of the two corresponding codes. This number is an absolute value, however, which ignores the total combinations theoretically possible. In other words, it neglects all the missed opportunities where there could have been an overlay. This can be corrected by calculating the maximum possible similarity and noting the actually counted similarities relative to it. By subtracting the counted similarities from the maximum possible similarities, the cases where there were no overlays are calculated. A large number represents two less-related codes while a low number determines two closely related codes. Visualizing the similarities between the codes is done by placing the codes as dots on a map and setting the calculated numbers as distances between them. This results in a map containing all the different relations between the selected codes. Two closely related codes are placed closely together on the map. The links are made visible by inserting lines between the codes. The thickness of the line is determined by the number of overlays while the dot size represents the number of segments coded with it.

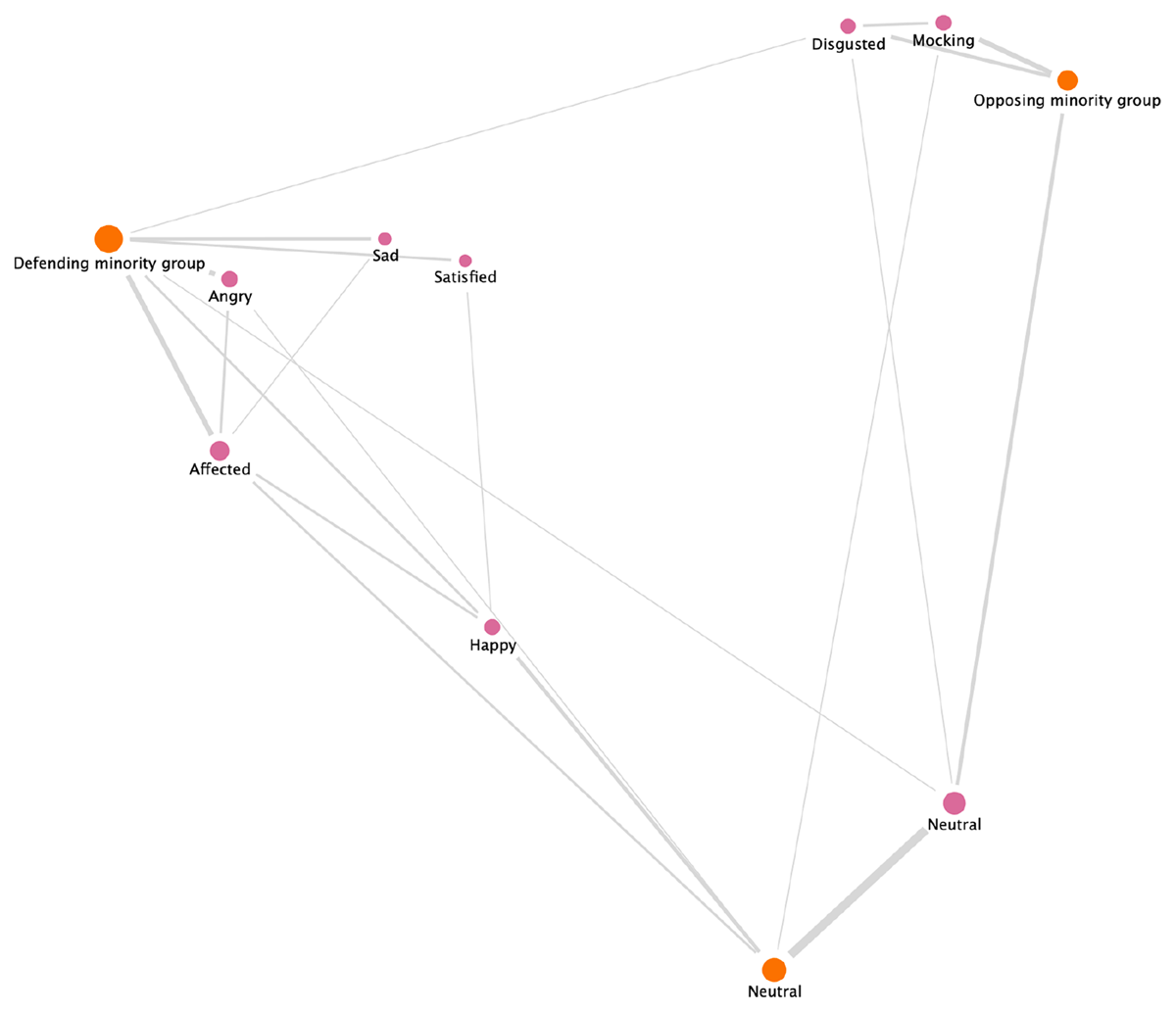

When it comes to raising awareness for sensitive topics, emotions are important. It is therefore useful to compare the lesson’s content with the students’ emotions. Figure 1 presents the relation between students taking sides for or against a minority group and their emotions. The emotions affected (angry, sad, and satisfied) are closest related to defending the minority group. Disgusted or mocking comments were most likely to oppose the group, while neutral remarks were mostly linked with neutral intentions. These links suggest that students’ decisions to support or oppose are strongly related to their emotions. While students who show affection or even get sad and angry with a topic tend to defend the discussed minority group. When they show deprecating emotions, on the other hand, they are likely to oppose.

Figure 1

Class’ inclination regarding emotions.

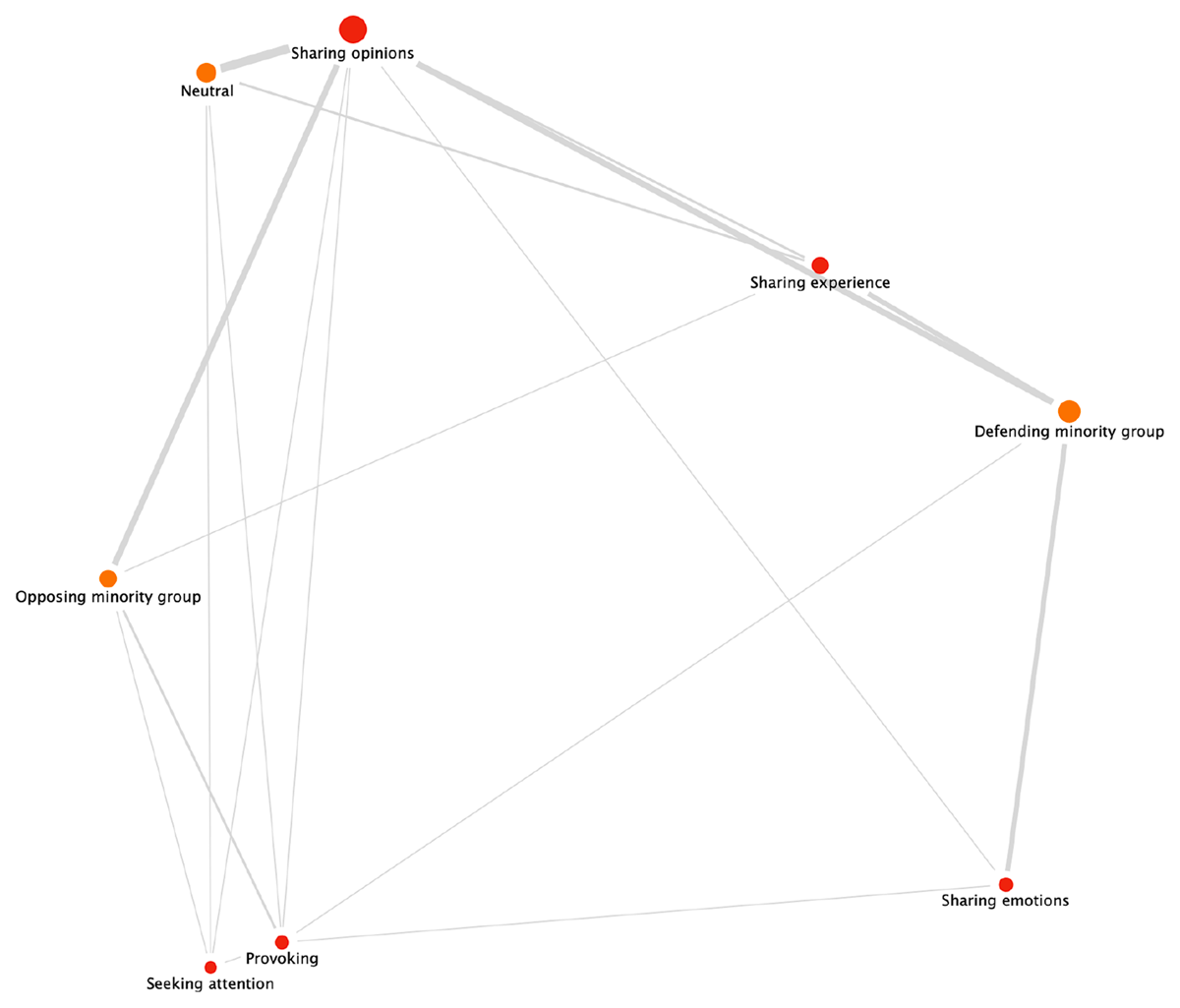

The conversations can be analyzed not only based on emotions but also based on their purpose. This facilitates understanding which statements lead to purposeful discussions. Figure 2 shows the relations between students taking sides for or against minorities and the purpose of their corresponding remarks. Close relations exist between a neutral attitude and when students shared their opinions, suggesting that by doing so, they did not tend to oppose a minority but did not likely defend it either. If the students wanted to provoke or seek attention, this was most likely combined with opposing the minority group, whereas students sharing experiences or emotions had low odds of defending the group.

Figure 2

Class’ inclination regarding purpose of remark.

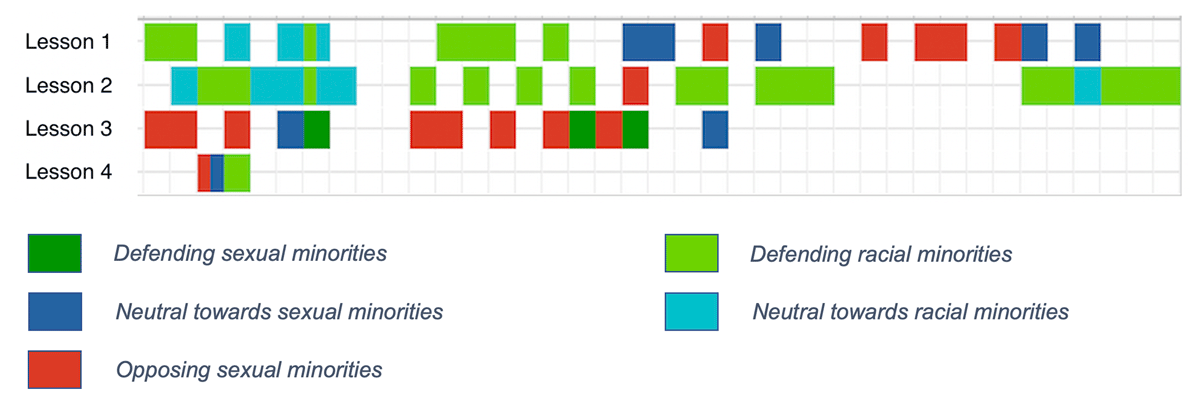

Apart from analyzing the interplay between lesson content and student responses, it seems useful to keep track of where students show strong biases and where not. Future lesson content can be tailored accordingly. Figure 3 shows the occurrence of the category ‘Taking sides’ with all the contained codes. It was created using codeline, a visual tool by MAXQDA. Each row represents a lesson in chronological order from left to right. The longer the bar, the more continuous observations of this code. The strong rejection of the students in the third lesson when we discussed mainly LGBTQIA is clearly visible, whereas the second lesson revealed supportive attitudes towards racial minorities. A repeated change of color indicates animated exchanges of opinion within the class, which happened for example towards the end of lesson 3 during the activity where the students had to guess which celebrities outed themselves as being non-heterosexual.

Figure 3

Class’ inclination throughout all four lessons.

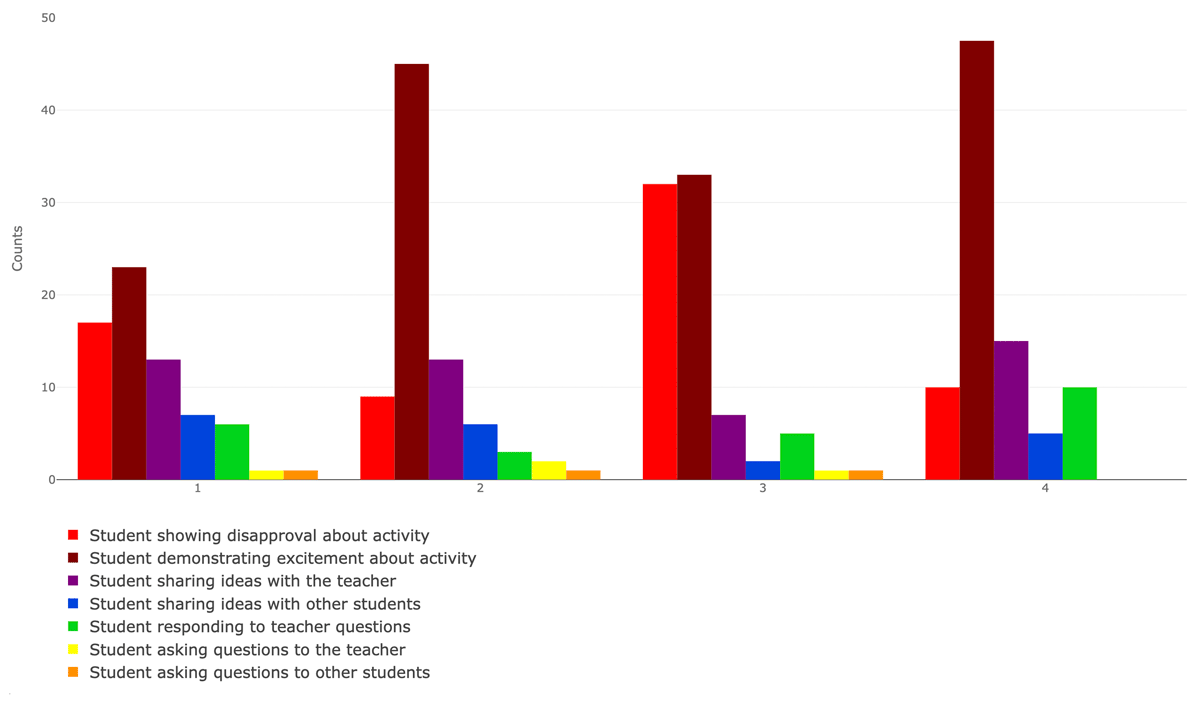

In addition, we investigated the data gathered with the SACS. The SACS measured students’ actions during the four lessons. Comparing the data among the lessons allows one to identify possible changes in student behavior. Figure 4 presents these results. Observations 1 to 7 refer to the observations described in Section 3.3. As lessons 1 to 3 lasted 50 minutes and lesson 4 only 20 minutes, the counts for lesson 4 were adjusted by multiplying with the factor 2.5. The first two observations occurred much more often than observations 3 to 7 because the latter represents a verbal action and not just an expression. Remarkable is the high count of observation 1 during lesson 3 which can be explained by the more uncomfortable topic in this lesson. Observation 2 showed an overall positive trend, although it was somewhat lower in lesson 3. Observations 4 and 7 showing a high involvement were about the same in all four lessons. In summary, while the students’ signs of disapproval or excitement depended on the lesson content, the lesson participation stayed about the same. The raw data with all single students’ results can be found in Appendix: Raw data SACS.

Figure 4

Students’ actions during lesson series.

Counts denote the counted occurrences of the observations in lessons 1, 2, 3, and 4, accumulated for all students.

5 Discussion

The conducted lessons of this study were orientated to current findings from the three suggested resources according to Derman-Sparks and Edwards (2019) which are children’s own questions and thoughts, teacher-initiated activities, and significant events that occur in the students’ communities. Besides, suggestions from Winkler (2009) were considered, meaning concretely discussing the issue and allowing students to truly participate. The interventions were mostly of a media-based nature, following suggestions of Burk et al. (2018). As most knowledge of ABE classroom implementation is rooted in primary or even early childhood education, this study aims to examine to what extent these findings can be adapted to the secondary level.

In terms of developing inputs for anti-bias lesson plans, this study offers some approaches that are relevant to classroom implementation. Out of all the analyzed parameters, two seem to be particularly decisive for students’ inclinations. First, students who were emotionally involved were more likely to defend the minority group. The results suggest that this involvement can either be a direct identification or another circumstance to which they can relate (see Figure 1). Second, giving the students a platform where they could share their experiences created a discourse where students tended to defend the minority group (see Figure 2). This result ties in well with previous studies wherein the importance of including experiences of marginalized groups was highlighted (Doucet & Adair, 2013; Escayg et al., 2017; Yu, 2020). The choice of focusing on showing lesson contents from the minority group’s point of view verified the promising approach of manipulating the social norm according to Bartoş et al. (2014).

Obviously, lessons can only have a potential effect on bias awareness if the class in question exhibits attitudes that could cause discrimination. Therefore, it is important to customize the lesson contents according to the class. If the students do not have biases against or for a particular group, it is not target-orientated to do more anti-bias activities regarding this group. Therefore, tracking the students’ inclinations during the lesson series can be helpful in comprehending the reappearing biases of the class. In this study, ABE content regarding sexual minorities seemed to be more urgent than regarding racial minorities (see Figure 3).

Short movies showing the perspective of the minority group proved to be effective. Among the resources used during the lessons in this study were little games which stimulated reconsideration of their own preconceived opinions. For example, students had to guess whether celebrity people identified themselves as LGBTQIA (lesson 3) with sometimes astonishing resolutions for the students. This activity challenged the prejudicial idea that being non-heterosexual is always visible. The activity led to a vivid discussion with a lively exchange of views.

While the students’ signs of agreement or disagreement depended on the lesson content, participation in the lessons did not change (see Figure 4). This indicates that students can actively participate in class even if they disagree with the content, assuming the activities are planned appropriately.

5.1 Limitations

The results are subject to some limitations that are presented in the following. Firstly, our study was conducted in a single classroom with 13 students. This obviously does not allow for any generalizability of our findings. The results cannot be applied to other classrooms, schools, or regions with different demographics or cultural contexts. Furthermore, no comparison between different lesson developments can be made because a different approach to lesson design did not take place. Secondly, as the researchers were also the instructors, their observations and interpretations could be influenced by their own biases or expectations. Additionally, thematic analysis of qualitative data involves a degree of subjectivity, which could influence the identification and interpretation of themes. Thirdly, the study relied on the observation of students’ behaviors during the lessons. Some aspects of discriminatory behavior might not be readily observable, and some students might change their behavior because they know they’re being observed, a phenomenon known as the Hawthorne effect. Fourthly, the focus was put on biases against LGBTQIA and PoC. Other forms of discrimination (e.g., based on religion, disability, etc.) were not addressed in this study.

6 Conclusion

This study aimed to seek out promising teaching considerations that could be included in an ABE lesson plan for a Swiss secondary-level class.

Following the literature which was mostly rooted in studies investigating students of primary school age, this study was able to produce a lesson plan that follows the principles of ABE but was adapted for secondary-level students.

Overall, the study considers the findings from the primary level to be promising in terms of applicability to the secondary level. Prior findings, as well as the evaluation of this lesson plan, show that it should be designed to be interactive and participatory, to encourage students to actively engage with the content and reflect on their own biases. Additionally, the lesson plan should be flexible and responsive to the students’ own questions and thoughts, as well as significant events that occur in the students’ communities. For active student participation, it seems not to matter whether they agree or disagree with the lesson topic.

Furthermore, this study provides additional information about what parameters might be decisive while creating an ABE lesson plan. When students get emotionally affected, they are more likely to defend the addressed group. The results suggest that this effect is even stronger when students report experiences in which they have perceived discrimination. Lesson settings where the perspective of the minority group is shown and therefore the social norm is manipulated seem to be especially promising as they enable students to experience discrimination in the classroom. On the other hand, situations where the students express themselves in a derogatory manner, are counterproductive in raising awareness.

Integrating ABE into the Curriculum 21 presents a promising avenue to foster anti-discriminatory behavior among students. Nevertheless, it is important to acknowledge that classroom dynamics vary, necessitating teachers to tailor the lesson plans to suit their specific student composition. The findings underscore the pivotal role of personal involvement in shaping students’ reactions toward certain minority groups.

6.1 Further research

We suggest that future studies should focus on the following points to further investigate the mechanisms of preventing bias-related discrimination in secondary-level schools. Firstly, it could be interesting to conduct studies that will show whether biases are already more hardened and, therefore, more difficult to tackle at the secondary level compared to primary schools. Secondly, since there is almost no knowledge of whether ABE content affects students’ bias-awareness in the long run or even their discriminatory behavior, long-term studies should be done. This could involve longitudinal studies tracking the same group of students over several years to assess whether changes in attitudes and behaviors persist over time. To gather generalizable data, studies should include enough students to apply quantitative methods. Furthermore, future research should consider other types of bias and discrimination, such as biases based on religion, disability, socioeconomic status, or age. This could help to develop a more comprehensive understanding of bias and discrimination in schools and how best to address these issues.

Additional Files

The additional files for this article can be found as follows:

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Author Contributions

Florian Feuchter: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Writing – Original Draft, Visualization, Project Administration

Damaris Fischer: Conceptualization, Writing – Review & Editing