Introduction

This paper explores the role of resource constraints in shaping industrial cycles by assessing the woody biomass carrying capacity of the Northern Omani interior, specifically focusing on Wadi Raki, and the availability of raw materials necessary to sustain copper production. This analysis is based on archaeological evidence from slag heaps, which provide data on the scale and periodicity of past production. We hypothesize that if production demands exceeded the environment’s baseline carrying capacity, human groups would have needed to develop strategies to secure reliable access to resources or limit their activities accordingly.

Understanding these constraints is essential for examining broader patterns of human-environment interaction, a central challenge in archaeology. Throughout human evolution, communities have innovated and adopted diverse cultural and technological traditions that allowed populations to thrive in various natural and social landscapes and rapidly expand into and develop new ecological niches (Frieman 2021, Pollard and Gosden 2023, Roux 2010). As communities expanded, many societies pursued resource intensification strategies, inadvertently impacting the environment and catalysing major societal changes (Ellis 2021, Kirch 2005).

For millennia, wood has been pivotal in sustaining human subsistence and economic activities, making trees and forests key enablers of socioeconomic transformation toward wealth accumulation, growth, and expansion (Asouti and Kabukcu 2021, Marston 2009). The utilization of wood can serve as a proxy for assessing the intensity of human-environment interactions and as an indirect indicator of demographic, social, and cultural transformations, as well as historical ecological dynamics (Dufraisse et al. 2022, Smith et al. 2015). Early agricultural communities used wood for domestic and subsistence purposes, including fuel and construction. Wood played a crucial role in extractive metal economies, where it was essential for mining, ore preparation and roasting, smelting, and melting (Chew 2001). Traditional technologies required substantial wood charcoal volumes for ore reduction, potentially leading to significant deforestation as a byproduct of metal production (Iles 2016). Forests are dynamic ecosystems, hosting diverse tree species with varying reproductive and regrowth cycles, which could be extended or shortened by anthropogenic intervention. Thus, the extent and duration of environmental impacts not only would have depended on levels of fuelwood consumption, but also woodland management strategies, such as coppicing or pollarding, and cultural logging restrictions.

Furthermore, metallurgy’s impact on forests could have ranged from reversible temporary effects to sustained depletion of forest resources, a factor potentially contributing to periodicity involving pronounced increases and decreases (or gaps) in metallurgical activity. Archaeologists refer to this pattern as the periodicity problem (Weeks 2003). To locate such patterns in the archaeological record, archaeologists have often analysed archaeometallurgical, archaeobotanical, and geoarchaeological datasets to reveal intertwined cycles of environmental degradation and metallurgical practice intensification (Iles 2016). However, natural climate variations and human activities, such as agriculture and grazing, make it difficult to disentangle the specific factors contributing to environmental degradation and to accurately assess carrying capacity and human impact at any given time.

Background

Studies of the ecological consequences of ancient metallurgical activities commenced in sub-Saharan Africa in the latter part of the 1970s and early 1980s. This research was initiated primarily due to the abundance of ethnobotanical information still preserved in the region (Iles 2016: 1227). These investigations quantified woodland degradation using a sequence of calculations. First, they approximated the volume of slag residue, which is the most conspicuous remnant of past metallurgical practices. Second, through a series of rough estimations, they calculated the quantity of charcoal necessary for the entire metallurgical process. Finally, to evaluate the environmental impact, the charcoal consumption was converted into wood volume and then extrapolated to individual trees or woodland acreage. Early approximations in West Africa ranged from 300,000 individual trees (Goucher 1981) to 480,000 m3 of charcoal (Håland 1980) consumed at different locations over a span of several centuries of production. Since the early 2000s, there has been a revived interest in anthracological research, with contributions from paleobotanists and paleoenvironmentalists increasingly enriching this field of study (Iles 2016). These recent projects have embraced a more comprehensive approach, including detailed dendroanthracological analyses of charcoal remains to detect and assess the impact of management practices such as the utilisation of deadwood (Asouti and Austin 2005), coppicing (cutting the tree to stump to encourage the growth of new shoots), pollarding (pruning all top branches of a tree), shredding (the technique of pruning side branches leaving the main trunk and top growth), lopping (pruning indiscriminately to the stubs or lateral branches between the nodes), and others (Kabukcu 2018). Notably, recent studies have continued the tradition of quantitative analysis while integrating archaeology, archaeobotany, and ethnohistory into their assessments (Crew and Mighal 2013; Eichhorn et al. 2013).

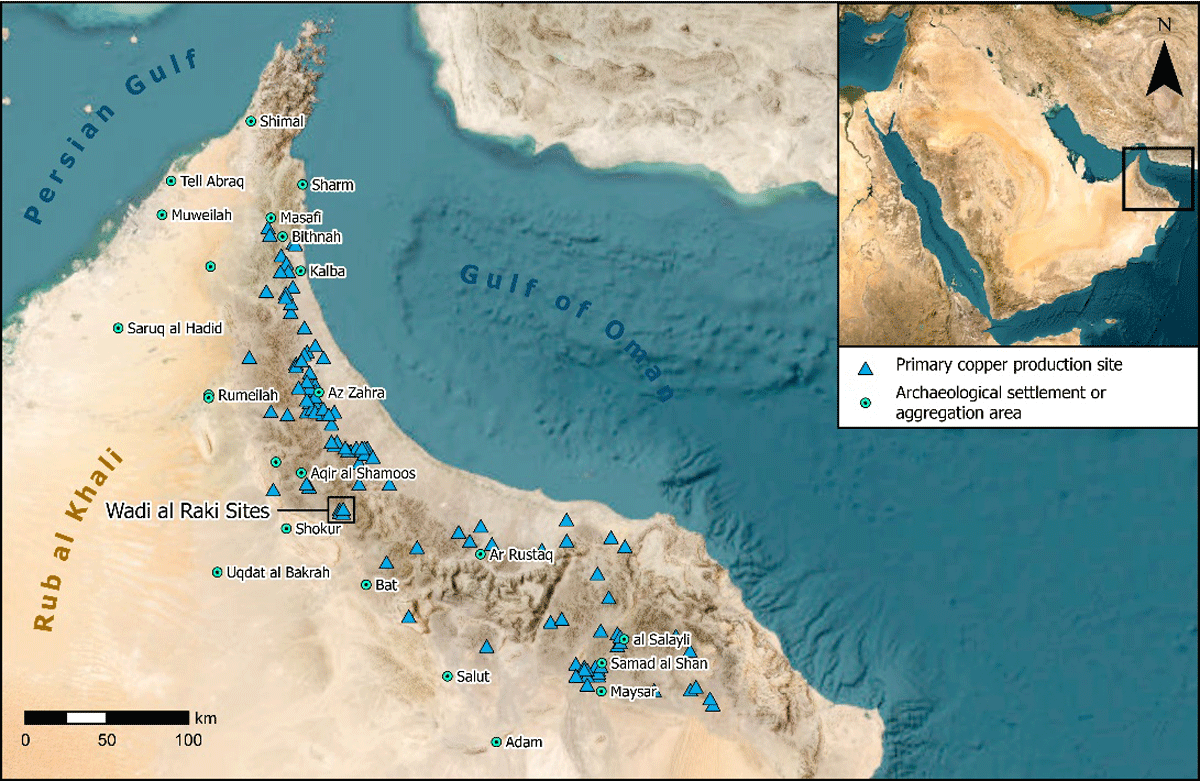

The investigation of archaeometallurgical practices in Oman commenced in the late 1970s and early 1980s with the aim of shedding light on the previously unknown large-scale copper production in the country (Weisgerber 1978a, Weisgerber 1980). These studies identified the most intensive period of copper production as occurring during the Early Islamic period (635–1055 CE) (Zaribaf et al. 2024) when 240,000 tons of slag were produced. Based on these findings, it was estimated that more than 280,000 tons of charcoal were required to sustain this level of production, equivalent to 1,400,000 tons of wood assuming a 20 percent charring efficiency. If domestic consumption and roasting were considered, then 2 million tonnes of wood would have been consumed during the main phase of early Islamic copper production (Weisgerber 1980). This would have driven the extraction of 22–25 million trees for fuelwood (Hauptman 1985, Eckstein et al. 1987, Yule 2021), suggesting to scholars that charcoal production would have led to widespread deforestation and desertification. This provided early researchers with an explanation for prolonged periods of inactivity of primary copper production across the region (Figure 1). When copper production resumed in the Middle Islamic Period (1055–1500 CE), neither the scale nor the complexity of the operation matched that of the earlier phase (Hauptman 1985). The slag scatters, which were much smaller in absolute volume and consisted of fragmented bowl-slags compared to the earlier massive heaps, indicated a simpler smelting practice, possibly involving the reworking of slags from the previous periods of copper production (Weisgerber 1978b). Notably, the slag fields were located closer to residential sites in wadis, where vegetation cover was denser. Consequently, earlier studies concluded that “in the main period, the fuel came to the ore, but in the second, minor period, the ore was transported to the vegetation” (Weisgerber 1980: 119).

Figure 1

Iron Age and Early Islamic primary copper production sites and associated aggregation areas in southeastern Arabia.

The estimates presented above involve a significant level of uncertainty and are influenced by multiple sources of cumulative error. Iles (2016) highlights key sources of cumulative error in estimating wood consumption, including: 1) inaccuracies in slag volume estimation, 2) uncertainties in fuel consumption calculations, 3) variability in wood-to-charcoal conversion ratio, 4) challenges in translating wood usage into estimates of woodland acreage, and 5) difficulties in reconstructing the intensity and chronology of production over time. Similarly, assessing the environmental impact of archaeometallurgical practices is complicated by several uncertainties: 1) the challenge of accurately estimating ecological resilience and woodland regrowth rates at the time of consumption, 2) limited knowledge of past socio-cultural woodland management practices, including species selectivity (Proctor et al. 2024) and cultural taboos, 3) the influence of technological innovations and advancements in pyrotechnology, 4) the cumulative impact of other pyrotechnological, agropastoral, and domestic activities, and 5) the low resolution of available paleoclimatic data.

Given these challenges, our research aims to establish a baseline assessment of modern wood biofuel availability. This assessment will serve as a basis for spatial and temporal extrapolations to estimate the environmental impact of ancient copper production. The waste products of copper-rich slags from the smelting process can be utilized to gauge the intensity of production, including the required charcoal and fuelwood. Hauptman (1985) estimated that sustaining the surge in copper production in Oman during the 9th and 10th centuries CE – when the region was part of the Abbasid Caliphate’s economic and political sphere – required between 22–25 million trees. The period corresponds to the Golden Age of the Abbasid Caliphate (Bennison 2011). Over recent years, the ArWHO team has implemented a semi-automatic method to identify slag heaps and their boundaries (Sivitskis et al. 2019). These spatial delineations, in conjunction with on-the-ground elevation models, can more accurately calculate the total volume of slag heaps. Slag densities derived from systematic excavations allow for the calculation of total mass. Subsequently, the biofuel requirements can be more accurately estimated. Comparing these results with the biomass map of the region can illustrate the spatial extent of environmental impact on the rangeland landscape. Oman provides an ideal case study for reconstructing ancient metallurgical industries, as its semi-arid mountainous landscape allows for the clear identification of both slag heaps and individual tree stands through satellite imagery. Dating archaeological evidence of industrial production can be achieved through radiocarbon analysis of charcoal fragments embedded in slag, while biomass quantification in the present environment is feasible and well within current methodological capabilities. However, obtaining more precise chronological data and accurately estimating production output — and consequently, biomass consumption in each phase of production — requires further investigation. This includes more extensive excavations and a greater number of radiocarbon dates to refine chronological resolution.

Southeastern Arabia encompasses a diverse range of ecological zones, from the sand dunes of Rub’ al-Khali to the seasonal pasturelands of Dhofar, the rocky outcrops of the Musandam Peninsula, and the golden beaches of the Persian Gulf and Gulf of Oman. In the ecological study by Ghazanfar (1991), plant communities in Oman were classified into nine categories. Wadi Raki can be placed in the second category, characterised by a predominance of Acacia tortilis. Over time, the area’s indigenous plant communities have been altered by settlement expansion, date palm cultivation, and animal husbandry, leading to their gradual degradation and replacement with cultivated genera.

A defining feature of the environment in Wadi Raki, our study area, is the Al-Hajar Mountain range, which stretches across Oman from Musandam in the north to Ras al-Hadd in the south. The lowland plains of the interior reveal a complex geological history and rich mineral deposits, including copper, chlorite, limestone, and marble, which have been historically exploited. Copper production has left the most environmentally costly footprint and is both archaeologically detectable and quantifiable. Copper ores in Oman occur in two geological settings: the Semail Nappe ophiolite and the ophiolite sequence of Masirah Island. The former has been intermittently exploited from the Chalcolithic (Hafit) and Bronze Age (Umm al-Nar and Wadi Suq) through the Iron Age to medieval times (Weisgerber 2008).

Wadi Raki carves a path southward from the rugged ophiolite mountains to the gravelly alluvial plain, standing out as a key location for copper production in ancient Arabia. Archaeological sites along Wadi Raki consist of three clusters of slag heaps, spread over 12 sq km, known as Raki 1, Raki 2, and Tawi Raki (Figure 2). Raki 2 is associated with a sizable Early Iron Age settlement (1300–800 BCE), while the other two are primarily attributed to the Early Islamic period (635–1055 CE) with minimal residential remains (Sivitskis et al. 2019, Lehner et al. 2023). Major bursts of copper exploitation followed by long intervals of inactivity have also been observed at other copper production sites in the region (Weisgerber 2008), such as Arja (Weisgerber 1987), Mullaq (Ibrahim and Elmahi 2000), and Maqsad (Weisgerber 1980).

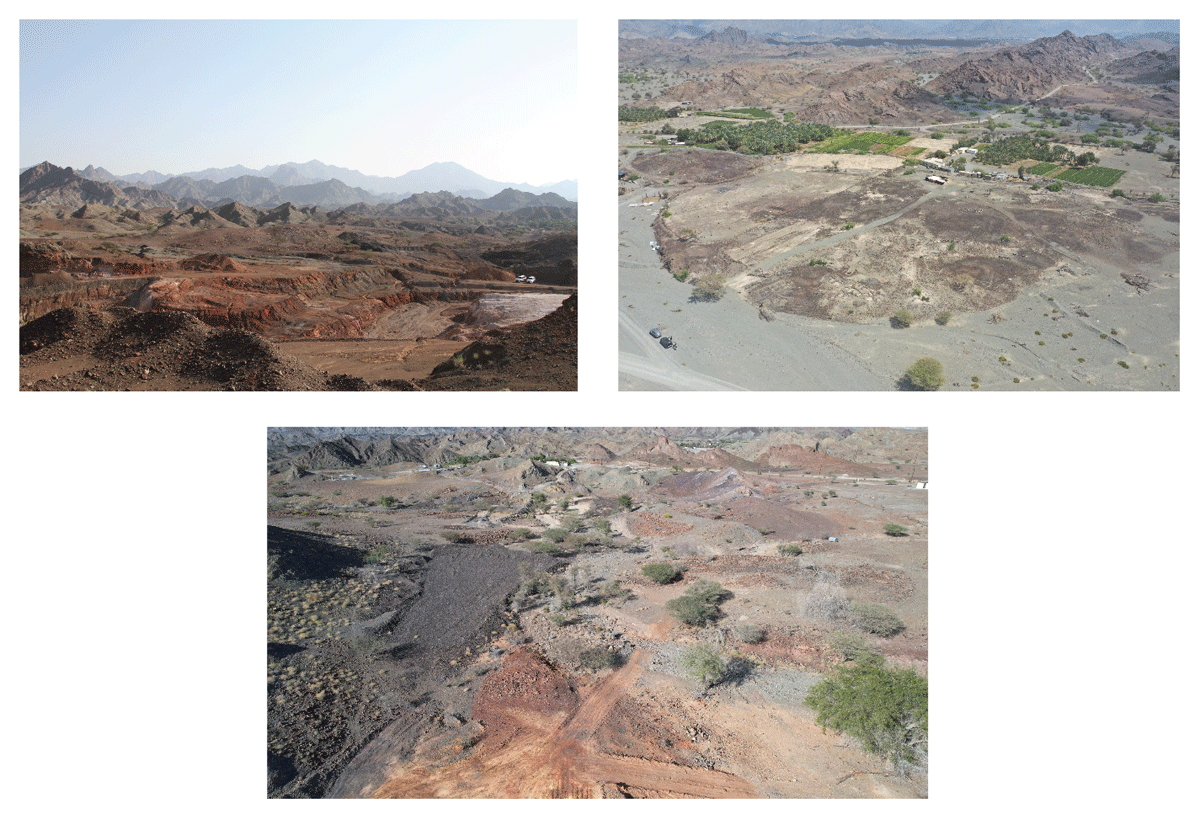

Figure 2

Sites from top to bottom, left to right: Raki 1, Raki 2, and Tawi Raki.

Ghazanfar’s (1991) ecological study indicates Wadi Raki falls within the category dominated by Acacia tortilis. This species played a crucial role in metallurgy, as Weeks (2003: 35) estimates that several million Acacia trees were harvested for copper production during the Iron Age. This aligns with Weeks’ (2003: 34) observation that no primary production sites have been identified for the Late Iron Age, suggesting that peak copper production lasted for approximately 500 years. The minimum estimated total of Iron Age slag is around 80,000 metric tonnes, indicating the production of approximately 10,000 metric tonnes of copper (Weeks, 2003: 35). However, the limited archaeological and metallurgical research, as well as the lack of experimental studies on Iron Age copper smelting, pose significant challenges to understanding the chronological development of metallurgy in Southeast Arabia during the second and first millennia BCE (Weeks, 2003: 42). The lack of archaeometallurgical evidence and limited knowledge of Iron Age metallurgical techniques make it difficult to accurately reconstruct the smelting process, which in turn affects the precision of fuelwood requirement estimates. The Early Islamic period (635–1055 CE) witnessed the production of an estimated 600,000–650,000 tonnes of slag, with varying yields at different sites, ranging from 5 tonnes at Bayda to 100,000 tonnes at Lasail (Hauptmann 1985: 114–116). This era marked significant progress in copper processing technology, likely influenced by the exploitation of copper resources during the late-pre-Islamic/Sassanian period (Weisgerber 1987: 149) and trade connections across the Hormuz strait (Hauptmann 1985: 101). Scholars hold slightly differing views on the duration and specific dates of copper production during this time, with estimates ranging from 100 years (Weeks 2003: 34, 35) to 150 years (Weisgerber 1980: 119, 1987: 149) to 200 years (Hauptmann 1985: 114). Excavations at major Early Islamic sites such as Tawi Raki and Raki 1 suggest a production continuity between 750 and 900 CE, aligning with the historical dates of the second Ibadi Imamate. The ongoing investigation into the relationship between the socio-political conditions of the Early Islamic period and the advancement of copper production is a topic of scholarly interest, with Zaribaf et al. (2024) exploring how political stability, economic networks, and technological innovations influenced the scale and organization of copper production during this time.

Methods

To assess the ecological impact of ancient copper production, accurately estimating fuel consumption—particularly the charcoal derived from native woody biomass—is crucial. This can be achieved by analysing the volume and total mass of slag heaps, which serve as a proxy for reconstructing the carbon footprint of the entire pyrotechnical process. The primary production phases at Raki 1, 2, and Tawi Raki date to two distinct periods: the Early Iron Age and the Early Islamic Period (Lehner et al. 2023). Based on our remotely piloted aerial survey and geospatial analysis, the total amount of slag present at the sites of Raki 1 and Tawi Raki is approximately 15,233 tonnes. However, it is crucial to note that modern mining activities at Raki 1 may have obliterated more than 50% of the archaeological evidence, including a significant portion of the slags. At Raki 2, the production of slag exceeded 44,000 tonnes.

It is necessary to determine the efficiency factor of converting wood to charcoal to evaluate the ecological impact of ancient copper production. Much work has been done on the fuelwood selection, which has provided a list of preferred species for various purposes such as the survey done by Al Hatmi and Lupton (2021). However, there remains a significant gap in the ethnographic literature concerning the methods of wood harvesting, kiln construction, and charcoal production, particularly in relation to raw metal smelting in Southeast Arabia. This deficiency has been noted by Horne (1982: 9) and further discussed by Ibrahim and el Mahi (2000: 216). The closest detailed description of traditional charcoal production comes from Mojtahedi’s (1955) work in northeastern Iran, and Lalmuankima’s (2019) work in northeastern India. The highlighted works provide detailed descriptions of traditional charcoal production methods, including images, dimensions and sketches of various kiln types. This information is essential for reconstructing the production process and aids in deriving more accurate estimations of the wood-to-charcoal conversion rate.

Based on field experiments and research —including tests using local species and insights from ethnobotanical literature —we have identified a conversion rate consistent with Eckstein et al.’s (1987) projections. These projections account for the calorific values of wood and the inefficiencies of traditional charcoal kilns. As a result, we propose that the efficiency of converting woody biomass to charcoal falls within the range of 11.2 to 5.8%. For the pyrotechnical processes, our field observations and literature review support a slag-to-charcoal ratio of 1:1.5 for the Early Islamic Period. For the Early Iron Age, an external literature suggests a broader range, from 1:0.13 to 1:1.5.1

Fuel Biomass Survey

The Fuel Biomass Survey (FBS) conducted during the 2020 field season in Wadi Raki and its surroundings collected data on aboveground biomass (AGB) to understand the availability of wood biofuel, a critical resource for large-scale copper production. Specifically, the survey was designed to model AGB in the vicinity of Wadi Raki (Lehner et al., 2020). The study aimed to investigate the role of resource constraints by modelling the carrying capacity of the environment and estimating the material required to support the scale of production suggested by slag heap volumes.

The FBS was a systematic survey in four established areas of interest with the goal of recording the total count and physical measurements of trees for allometric calculations. The survey was designed to represent tree species distribution within all recognized landform classes in the areas of interest. The sampling strategy required a minimum of three 100 × 100 m squares per landform class. Squares were assigned to landform classes based on a judgemental approach, prioritising those that appeared most prevalent in satellite imagery. Despite this, many squares still contained a mix of landform classes.

Two Fuel Biomass Surveys were conducted in two separate regions in northern Oman, namely Wadi Raki and ‘Uqdat al-Bakrah. The former region is located in the northwestern foothills of the al-Hajar Mountains, while the latter is located along the eastern edge of the Rub’ al-Khali Desert sand dunes (Yule and Gernez 2018, Wiig et al. 2018).

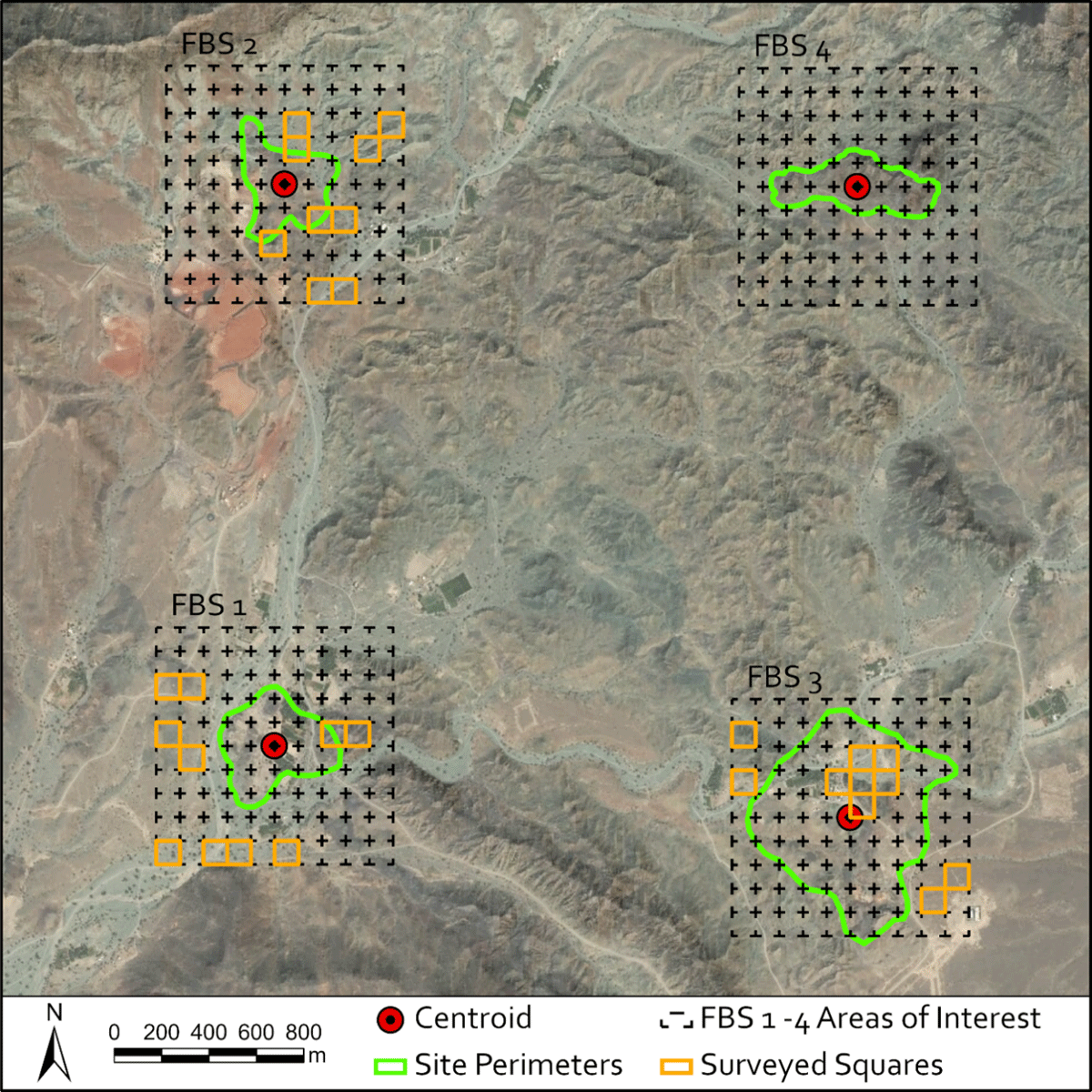

To create each area of interest, the ArcGIS Pro Centroid builder function was used to generate a point in the centroid of each site polygon. A 1 km2 buffer was then created around each centroid using the Buffer tool. The feature Envelope to Polygon tool was then utilised to create a square polygon around the centroid. Finally, the 1 km2 area was divided into 100 squares, each measuring 100 × 100 m using the Create Fishnet tool (Figure 3). While surveying the squares, the height, diameter at breast height (DBH), diameter at stump height (DSH), and crown area of each tree were recorded.

Figure 3

Fuel biomass survey in Wadi Raki. FBS1: Raki 2, FBS2: Raki 1, FBS3: Tawi Raki, FBS4: Qurun al Khabab.

The survey modelled the carrying capacity of the environment and estimated the material required to support production, suggested by the slag heap volumes. The survey’s sampling strategy aimed to represent tree species proliferation within recognized landform classes in the areas of interest. These landform classes were derived from Harrower et al.’s (2002: 38) publication on field survey methods in Hadramawt, Yemen, and have been used by the ArWHO project since 2011:

Bedrock Slope – Greater than a 15-degree slope or cliff (sometimes partially covered in talus or scree) that often separates upland plateaus from other landform classes.

Scree Slope – Angular clasts often on a low (<20 degrees) gradient between bedrock slopes, terraces, and wadi sediments.

Plateau – Upland bedrock surfaces above bedrock slopes and cliffs, primarily covered in small cobble-size clasts.

Gravel Terrace – Sub-rounded to rounded clasts often capping wadi silts and/or in close proximity to wadi channels.

Bedrock Terrace – Low angle (<5 degrees) or horizontal bedrock surface adjacent to Wadi sediments and/or scree slopes primarily covered in small cobble size clasts.

Wadi Silts – Pinkish, tan-coloured areas of very fine sand and silt above wadi channels, which often contain isolated lenses and scattered cover of gravel and/or scree.

Wadi Channel – The lowest and most fluvially active area often demarcated by whitish-grey rounded cobbles, boulders, and more prevalent vegetation.

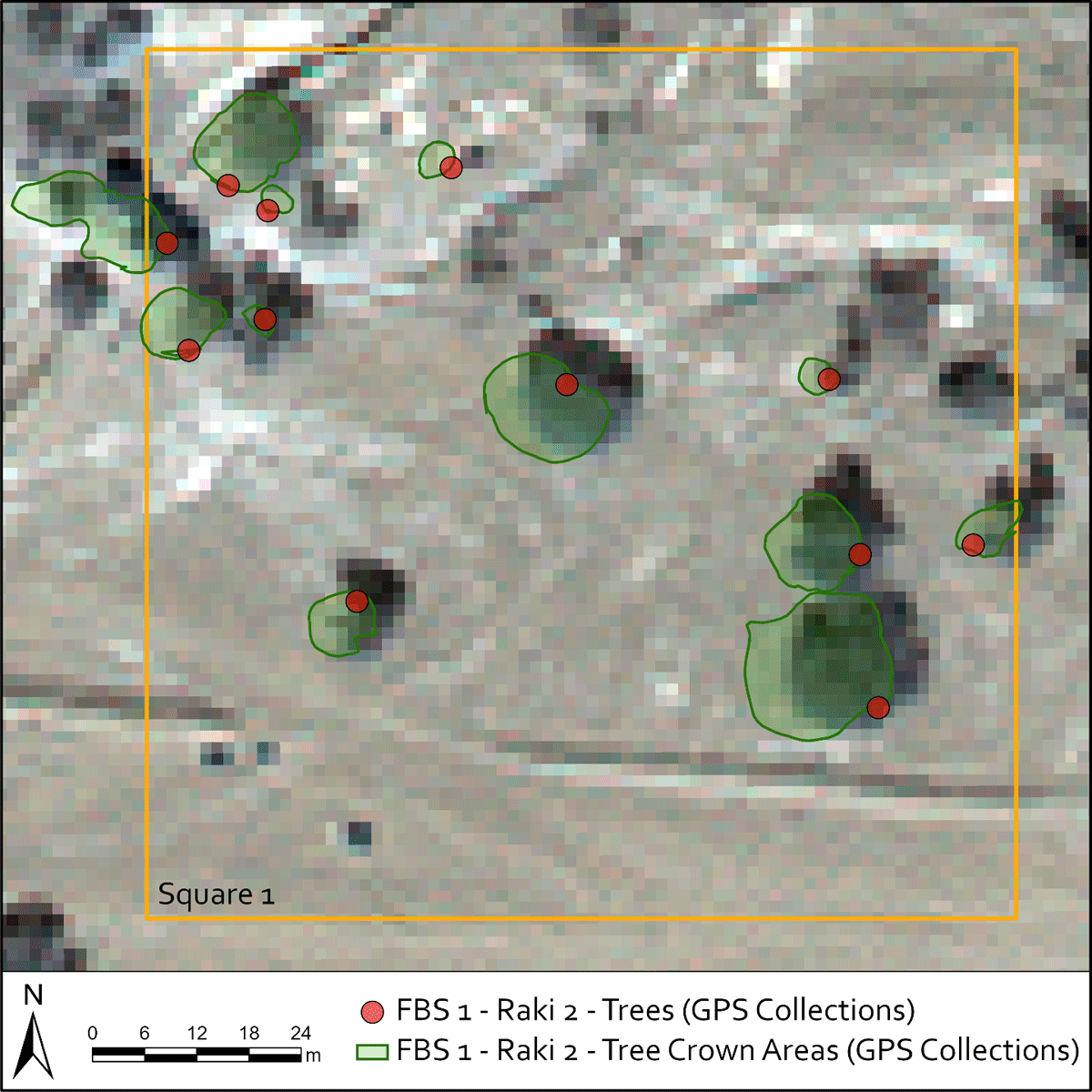

Upon arrival at a randomly selected square (of the total 28 in Wadi Raki), the FBS team used the satellite basemap to pinpoint and navigate to each tree. An iPad was used to record each surveyed tree as a point (as shown in Fig. 6.4). Subsequently, the team recorded two feature classes using a Trimble GPS GeoExplorer 6000 rover: a point feature (to document the information in Table 1) and a polygon feature to encircle the canopy (Figure 4).

Table 1

Recorded data sheet for individual trees.

| CATEGORIES | ATTRIBUTES |

|---|---|

| Tree | Numerical |

| Area of Interest | FBS 1, FBS 2, FBS 3, FBS 4, or FBS 5 |

| Square | Numerical |

| Stems at Stump Height | Numerical |

| Stems at Breast Height | Numerical |

| Circumference of Stem(s) at Stump Height | cm values divided by commas |

| Circumference of Stem(s) at Breast Height | cm values divided by commas |

| Tree Height | Numerical |

| Tree ID | Genus and Species |

| Confidence of ID | Possible, Probable, Likely, or Unidentified |

| Condition | Alive, Dead, or Horizontal |

| Landform Class | Bedrock slope, scree slope, plateau, gravel terrace, bedrock terrace, wadi silts, wadi channel |

| Slope | 0–5 degrees, 5–15 degrees, 15–30 degrees, >30 degrees |

| Deposition | Alluvium, colluvium, or other |

| Camera Type | Make and Model |

| Photo Range | Unique Photo Number |

Figure 4

Point and Polygon features recorded in the field. Note that the misalignment between the GPS-collected polygons representing tree canopies and the satellite imagery basemap is a consequence of inaccuracy of satellite imagery georeferencing.

The GPS data was processed daily using Trimble Pathfinder Office software, a Post-Processed Kinematic (PPK) workflow, and base station data collected using a Trimble R10 GNSS Receiver. A field manual, derived from Ghazanfar’s (2007) Flora of the Sultanate of Oman (Vol. 2), was created to aid in identifying local native tree species, featuring a species list and laminated color photographs. Tree heights were measured using a TruPulse Laser Rangefinder (Model 360B) and transmitted in real-time via a Bluetooth connection, automatically linking the data to the GPS records (Figure 5). Stem circumferences were measured in centimetres at both stump and chest height, with each stem recorded individually in the relevant attribute field of the GPS data.

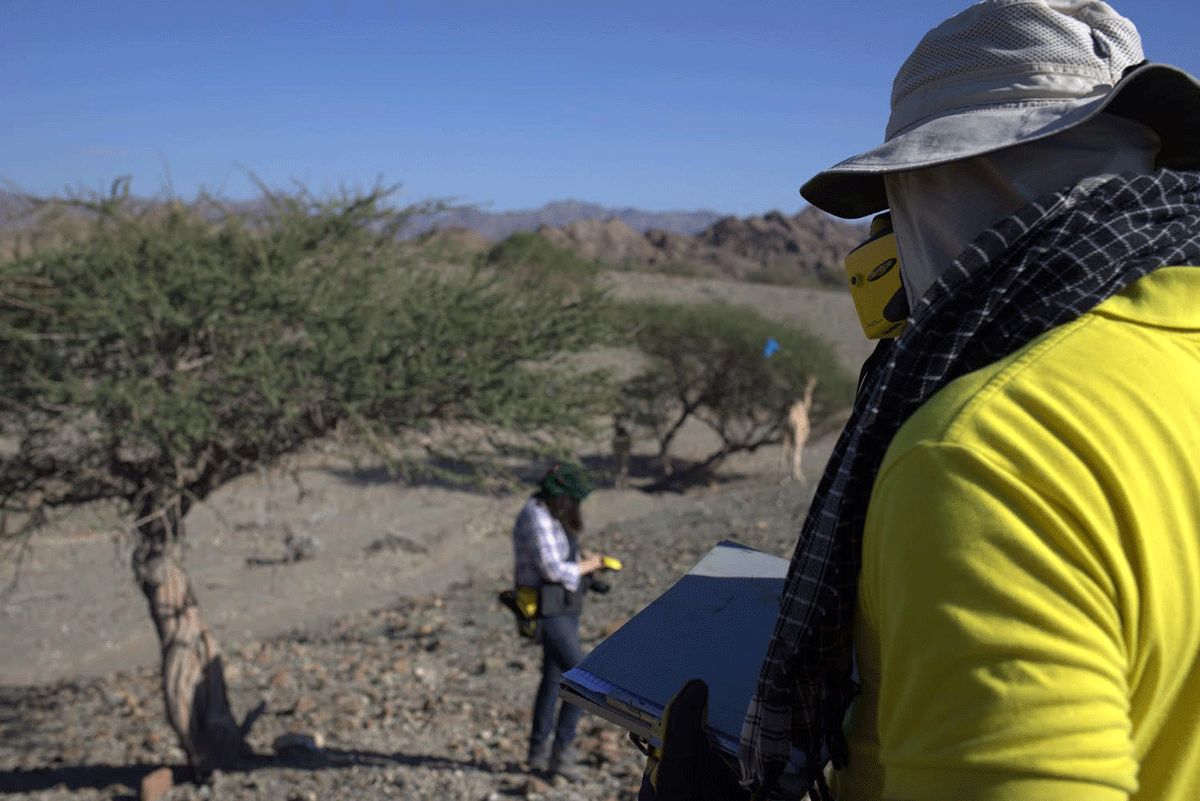

Figure 5

Fuel biomass survey measurements of trees being taken in the field.

Analysis

Tree measurements were aggregated for allometric calculations, which relate the biomass or dry biomass of a tree to its measurable physical attributes such as height, crown area, diameter at breast height (DBH), and diameter at stump height (DSH). Various published forestry sources were reviewed to identify the most suitable formulas for our study, selecting those based on practical measurement methods, comparable geomorphological and environmental conditions, and reliably estimated biomass values (Table 2).

Table 2

Above Ground Biomass (AGB) allometric equations estimated from DBH: Diameter at Breast Height 1.3 m above ground (cm) H: Height (m) stem_Circum: Stem Circumference and DSH: Diameter at Stump Height (cm) measured at 0.3 above ground.

| TREE ID | FORMULA | REFERENCE |

|---|---|---|

| Acacia ehrenbergiana | 1.07 exp(–4.23 + 1.63 ln(DBH) + 1.05 ln(H) – 1.89 ln(0.72) | (Moussa et al. 2019) |

| Acacia nilotica subsp. indica | 0.071 + 0.0818(DBH2 × H) | (Maguire et al. 1990) |

| 6.9319 × (DSH) – 43.731 | (Raizada et al. 2007) | |

| Acacia tortilis | exp(–3.043) × (DBH)1.411 × (H)2.266 | (Feyisa et al. 2018) |

| Acacia gerrardii subsp. negevensis | 2.692 × (Stem_Circum) – 2.699 | (Shackleton and Scholes 2011) |

| Ziziphus spina-christi | 1.07 exp(–4.23 + 1.63 ln(DBH) + 1.05 ln(H) – 1.89 ln(0.72) | (Moussa et al. 2019, Vreugdenhil et al. 2012) |

| Salvadora persica | 1.07 exp(–4.23 + 1.63 ln(DBH) + 1.05 ln(H) – 1.89 ln(0.6) | (Moussa et al. 2019) |

| Prosopis cineraria | (Jaiswal et al. 2018) | |

| Moringa peregrina2 | – 852.262 + 433.93 ln(DSH) | (Abdoul-Salam et al. 2021) |

Subsequently, the biomass of each tree and the total biomass within the selected 100 × 100 m squares was calculated from these formulas and the collected measurements. It is important to note that for an accurate reconstruction of the exploitation, biomass production, regrowth rate, and charcoal yield must be calculated separately. For example, studies on the biomass production and regrowth rate of Acacia species have indicated that managed coppicing at 12–14 years of age significantly improves regrowth rate and subsequently increases biomass yield in the next harvest cycle (Okello et al., 2001).

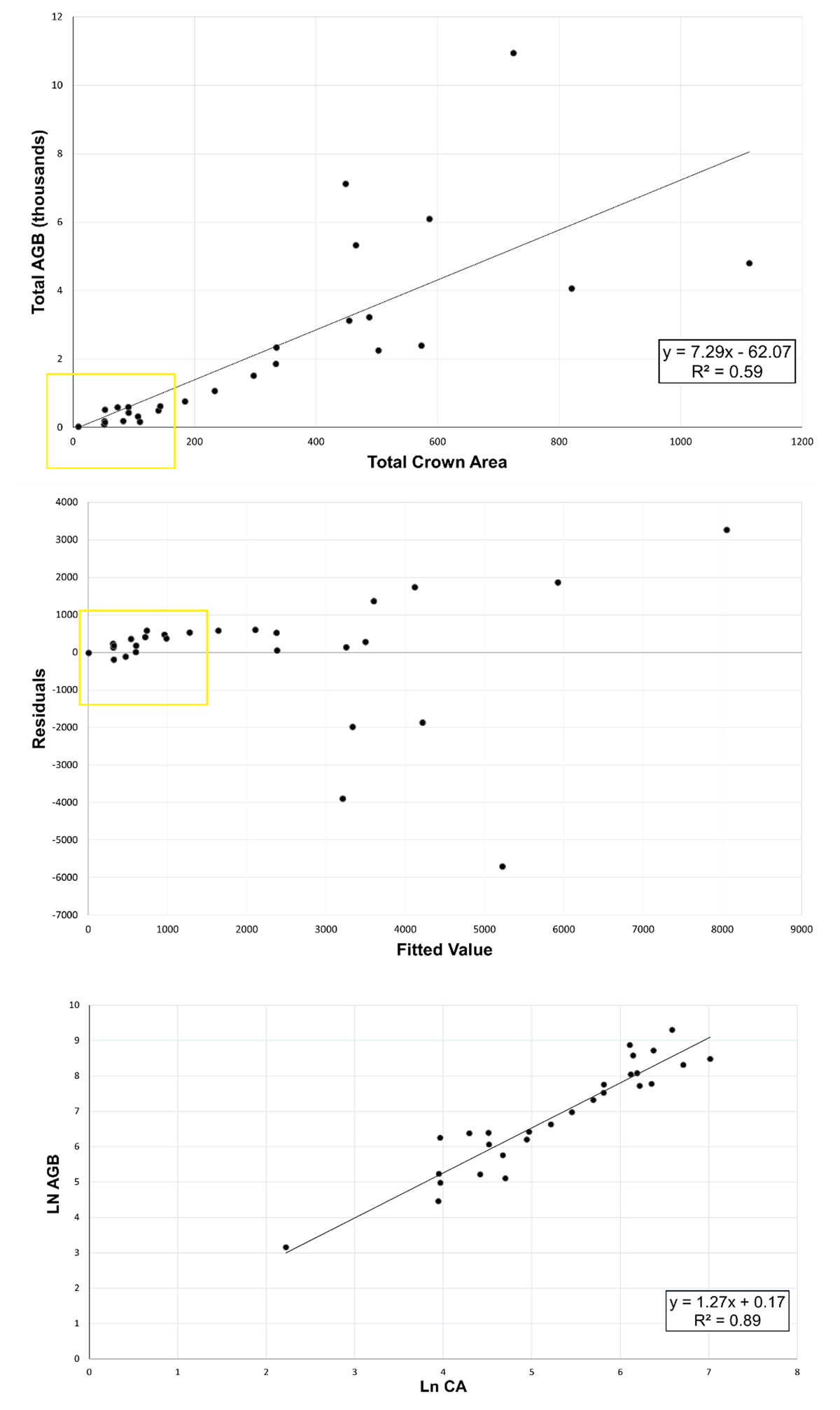

The coefficient of determination for the regression did not demonstrate a strong correlation between individual crown areas and tree biomass. This was primarily due to only two Acacia species showing an acceptable regression between their individual crown area and height, despite being the most common species in our area (Figure 6). This regression is crucial for the allometric equation used to calculate AGB. We excluded the ‘Uqdat al-Bakrah data from the regression analysis due to its unique ecological conditions, singular woody biomass species, and uncertainties about its role as a primary copper production site. Even with this precaution, the individual tree AGB did not show a strong enough correlation with the individual tree crown area, resulting in an insufficient coefficient of determination or R-Square for acceptable extrapolation (Table 3). To address this issue, we attempted a log-log regression model but had to substitute individual tree values with aggregated crown area and AGB per hectare to minimise the impact of species diversity in biomass estimations. We then applied a linear model to the aggregate values and examined the residuals against the fitted values. Observing heteroscedasticity in the residuals versus the fitted values, we tested a log-log regression model. Based on various regression statistics, this last model demonstrated the best overall goodness-of-fit for our data and was therefore selected for the next step of our analysis (Figure 7).

Table 3

Regression models and their parameters.

| PARAMETERS | INDIVIDUAL LOG-LOG MODEL | AGGREGATE LINEAR MODEL | AGGREGATE LOG-LOG MODEL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficients (Slope, Intercept) | 1.255, 0.400 | 7.294, –62.078 | 1.272, 0.176 |

| Slope and Intercept [Lower 95% to Upper 95%] | [1.082 to 1.428] [–0.161 to 0.963] | [4.844 to 9.745] [–1069 to 945] | [1.087 to 1.456] [–0.819 to 1.159] |

| Multiple R | 0.673 | 0.768 | 0.941 |

| R Square | 0.454 | 0.59 | 0.885 |

| Adjusted R Square | 0.451 | 0.574 | 0.881 |

| Standard Error | 1.203 | 1717.90 | 0.522 |

| F | 204.669 | 37.446 | 200.825 |

| Significance F | 3.434E-34 | 1.811E-06 | 9.669E-14 |

| t-Stat | 1.403, 14.306 | –0.127, 6.119 | 0.354, 14.171 |

| P-value | 0.161, 3.434E-34 | 0.9, 1.811E-06 | 0.726, 9.669E-14 |

| Observations | 248 | 28 | 28 |

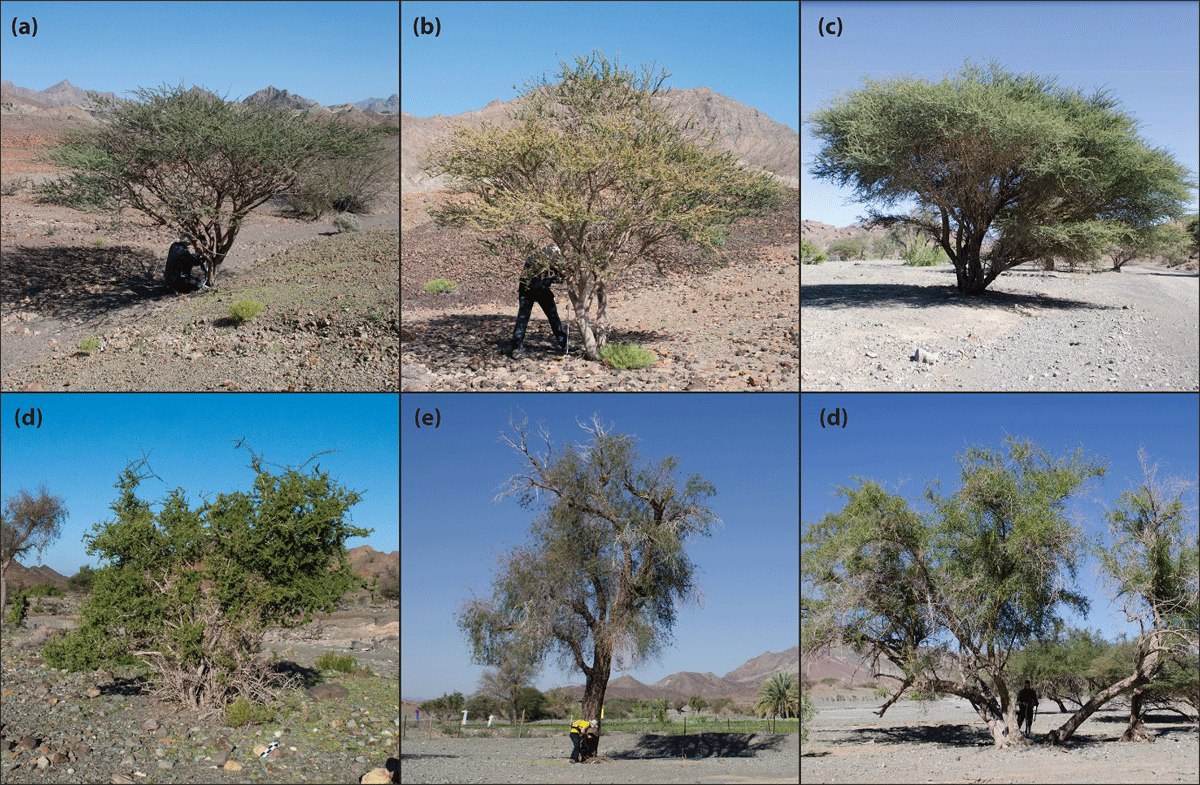

Figure 6

Six most common tree species observed during the Wadi Raki biomass survey. (a) Acacia tortilis, (b) Acacia nilotica, (c) Acacia ehrenbergiana, (d) Salvadora persica, (e) Prosopis cineraria, and (f) Ziziphus spina-christi.

Figure 7

The regression analysis process on the aggregated crown areas (CA) in square meters vs. aggregated above-ground biomass (AGB) in kilograms in 27 observed 100 × 100 m areas of land. There are some overlapping points in the yellow rectangles.

We have developed a workflow in ArcGIS Pro to identify tree crown areas within our survey regions. These generated crown areas are used in combination with field-verified measures to estimate aggregate AGB across our areas of interest. WorldView-3 multispectral imagery was pan-sharpened using the Gram-Schmidt pan-sharpening tool in ArcGIS Pro and then used to calculate several spectral indices (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), WV-VI, and Optimized Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index (OSAVI)) to identify vegetation within the image. Ultimately, we chose OSAVI for this project as it is a soil-adjusted vegetation index most suitable as a biomass indicator for semi-arid rangeland environments characterised by both sparse vegetation and soils with high reflectance values, such as dry sandy soils (Fern et al. 2018). After applying the OSAVI spectral index, the resulting raster was reclassified with vegetation values (ranging between 0.2–1) being converted to polygons of vegetation features. This polygon layer contained anthropogenic vegetation features, such as cultivated fields, which were subsequently removed. When working on a larger area, a mask obscuring cultivated lands was created. Then the area of each vegetation feature was calculated using the geometry calculator in ArcGIS and added as an attribute. The crown area of each tree was then used in the regression formula to estimate the biomass of each vegetation feature identified in the multispectral imagery. The ultimate objective of our analysis is to produce a spatial distribution of wood biomass and growth rate to map out the environmental impact of the metallurgists’ activities by illustrating the extent of hindcasted deforestation during each period. Since we are using aggregate regression, it is more suitable to use aggregate crown areas to estimate the total biomass. The size of each square in which this aggregation is calculated would determine the precision of our biomass map. For example, if a grid size of 30 m is chosen, then the centroid at the centre of each 30 × 30 m square would bear the weight of biomass for the whole square, hence the precision would be 30 m, equal to the distance between the closest centroids. From here, different methods of spatial interpolation could be used to create a continuous surface from the centroids. We have opted for the Inverse Distance Weighted (IDW) tool from the ArcMap geoprocessing toolbox (Spatial Analyst) as our standard technique. We will repeat the same process for the regrowth map. We will use the calculated acquisition rate to draw accumulative exploitation expansion polygons around each locus of production, which will illustrate how far the ancient copper workers would have had to travel to acquire their fuelwood. Due to the lack of species data from our remote-sensing estimation and ongoing archaeobotanical investigations, we have assumed a general growth rate of 3% per year (Eckstein et al. 1987: 4). This assumption and generalisation have inevitably reduced the accuracy of our assessment. It is important to note that our analysis does not account for forestry management practices used to prevent deforestation. Regrettably, despite our best efforts, the condition of the excavated charcoal from Wadi Raki that we analysed did not allow us to identify woodland management methods such as coppicing and pollarding.

Discussion

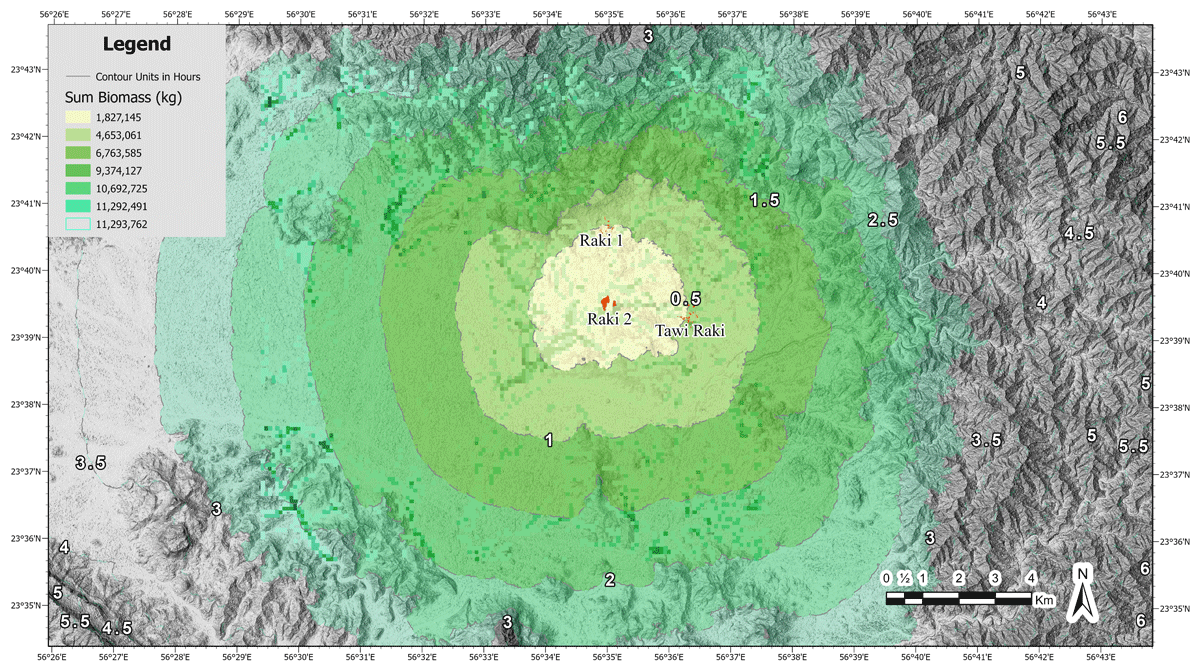

Based on the volumetric assessment of slag heaps and efficiency estimation of charcoal production, roasting pits and furnaces, we estimated that between 128 to 2,900 tonnes3 of biomass was consumed annually at the Early Iron Age site of Raki 2 to produce copper. The annual biomass consumption for the Early Islamic period lies between 1,360 to 2,626 tonnes. As observable in Figure 8, the total biomass availability in the three-hour vicinity of these sites contained 11,292 tonnes of harvestable biomass with a regeneration/carrying capacity of 112 to 565 tonnes per year.

Figure 8

Biomass availability in the vicinity of Wadi Raki divided by half-hour walking time intervals.

Paleoenvironmental studies indicate that environmental conditions in Oman and the broader Arabian Peninsula remained relatively stable during the periods under discussion, with a gradual trend toward desertification over the past 3,000 years (Fuchs and Buerkert 2008; Fleitmann and Matter 2009). Paleoclimatic evidence indicates that aridification associated with the southward retreat of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) occurred in two major steps at 5000 and 2700 cal yr BP (Lézine et al. 2017). This shift coincided with the disappearance of Rhizophora mangroves and the expansion of Prosopis cineraria along the coastline (Lézine et al. 2017).

More recent high-resolution paleoclimate data, derived from stalagmite records in Hoti Cave, Oman, provide additional nuance by revealing episodes of climatic instability over the last 2,600 years. These records indicate a severe and prolonged drought in the early sixth century CE, which was previously unrecognized in historical sources. This event likely played a role in undermining the resilience of the Himyarite kingdom in southern Arabia, contributing to broader socio-political changes in the region from the 520s to the early seventh century CE (Haldon and Fleitmann 2024). While these findings highlight the significance of long-term climatic fluctuations, the available paleoenvironmental data still lack the temporal and spatial resolution needed to reconstruct exact climatic conditions with confidence.

Although no climatic event on the scale of the mid-Holocene monsoonal shift occurred during the periods of interest, smaller, shorter cycles of climatic variability affected the region from 2000 BP onward (Urban and Buerkert 2009; Miller et al. 2016; Fleitmann et al. 2022). These shifts would have influenced local resource availability and human adaptation strategies. Despite these environmental challenges, some populations in the arid and semi-arid zones of Arabia demonstrated remarkable resilience. Through a combination of socio-political organization, technological advancements, and adaptive water and land management practices, some communities were able to navigate climatic fluctuations and sustain their livelihoods (Cremaschi et al. 2018; Petraglia et al. 2020).

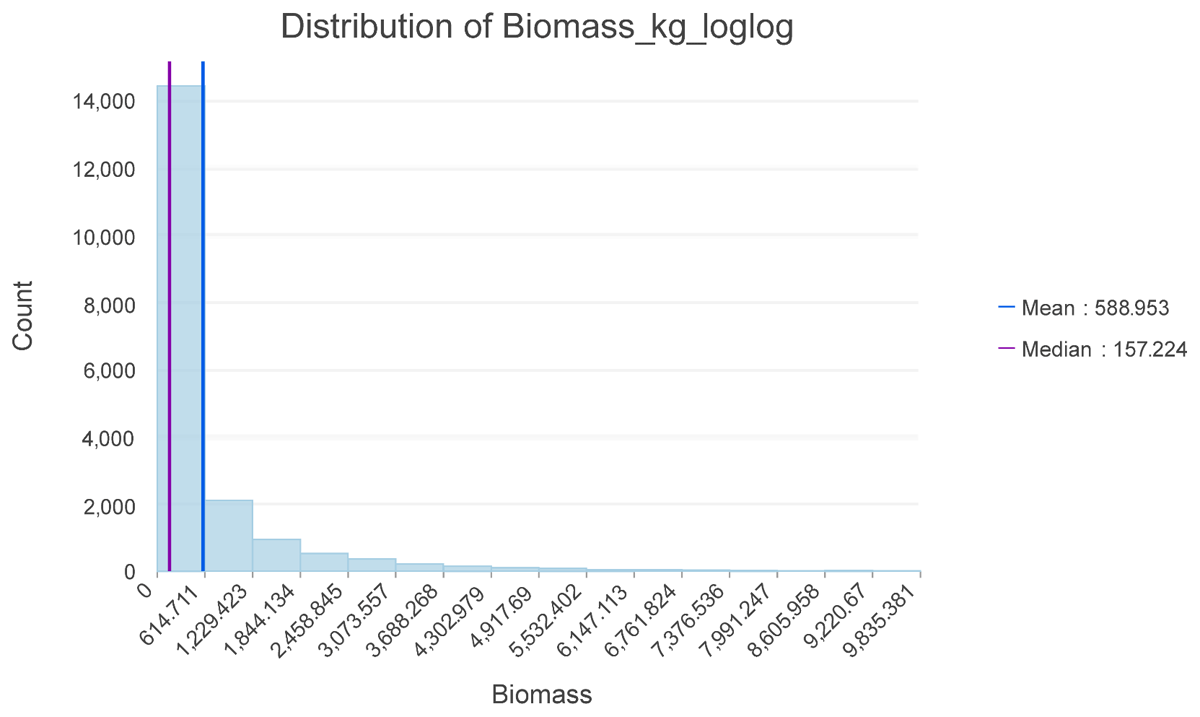

Based on our results, the environmental impact of copper production had effects that reached beyond a day’s travel (approximately 6 hours roundtrip) of the production sites. Those involved in charcoal production had to be resourceful in order to prevent the rapid depletion of their resources. The Yanqul Wilayat, where Wadi Raki is located, yields an average biomass availability of 588.953 kg per hectare (Figure 9), which may be representative of the biome in central and northern Oman. This provides us with average biomass production and a sustainable carrying capacity of 17.668 kg per hectare, assuming 3% annual growth (Eckstein et al., 1987).

Figure 9

Histogram of woody biomass (kg) per hectare.

Based on the fact that copper production was sustained over long periods of time despite the strict limitations of a semi-arid environment, it is hypothesized that through iterative experimentation and cultural transmission of ecological knowledge, copper smelters and their charcoal suppliers developed an understanding of their local environment’s carrying capacity, thereby avoiding its overexploitation especially during the Bronze and Iron Ages. This interpretation, supported by the sustained multi-century nature of their production activities, suggests the potential for large-scale sustainable copper production during the Iron Age. In the Early Islamic period, achieving sustainability would have posed significant challenges due to the concentrated and intensive nature of production activities. This was particularly pronounced in the northern Hajar Mountain region, where multiple production sites were clustered near each other and the major port city of Sohar. The minimum area necessary for each site to operate sustainably overlapped considerably with that of others. As a result, simultaneous operation of these sites while ensuring sustainability would have been practically unfeasible.

Achieving sustainability likely necessitated a sophisticated ability to forecast resource availability, a deep comprehension of the local environment, and the implementation of effective social mechanisms to manage resource harvesting practices and resolve territorial conflict. While there have been instances of imported “exotic” wood taxa, primarily in the form of finished products or for specific uses such as status signalling, construction, packaging (Tengberg 2002, Weeks et al. 2017: 37–40), utilising non-local fuelwood sources primarily for pyrotechnical purposes would likely have been economically unfeasible during this period. This impracticality stemmed from the vast scale of the operations and the logistical constraints regarding transportation.

A third alternative would be the supplemental use of dung fuel to assist in smelting practices. Dung has long been documented ethnographically, ethnohistorically, and archaeologically as an important fuel source in many regions of the world (Miller 1984, Smith et al. 2019). While dung fuel can theoretically be used in metal melting and smelting activities (Kaufman and Scott 2015, Verly et al. 2021), there is no evidence of intensive smelting which relied completely on dung as a fuel source. Archaeological and ethnographic evidence demonstrates that calorific charcoal is typically preferred given its optimal energy density and carbon content relative to dung, grasses, and green wood (Horne 1982). This is commonly expressed in archaeological assemblages related to smelting practices globally (Cavanagh et al. 2022, Humphris and Eichhorn 2019, Larsen et al. 2024).

Conclusion

This study sheds new light on the periodicity of copper production in Wadi Raki, Oman, revealing significant insights into the environmental and socio-economic factors driving ancient industrial activities. By integrating pedestrian surveys, remote sensing, targeted excavations, and laboratory analyses, we have established a comprehensive baseline understanding of the factors influencing the tempo of copper smelting in this region. Our findings highlight the complex interplay between environmental resource management and industrial production, characterized by intensive bursts followed by long periods of inactivity, underscoring the critical role of resource availability and sustainability in shaping ancient economic practices. The substantial fuelwood requirements for charcoal production and the consequent deforestation provide a tangible link between industrial activities and environmental degradation, further complicating our understanding of human-environment interactions in ancient societies. The innovative methodologies employed in this research, including the semi-automatic identification of slag heaps and biomass mapping, have enabled more accurate estimations of the environmental impacts of ancient copper production, offering valuable tools for future archaeological and ecological studies. Nonetheless, uncertainties regarding the paleoenvironmental conditions stemming from the low resolution and spatial and temporal gaps in our climate archives still hinder a comprehensive and unequivocal reconstruction of human-environment interactions in late Holocene Arabia. This issue is exacerbated by the absence of sufficiently accurate archaeological records for some of the periods in question. Overall, the research conducted at Wadi Raki not only enriches our knowledge of copper smelting in Southeastern Arabia but also contributes to broader discussions on sustainable resource use and the long-term consequences of industrial activities, highlighting the importance of interdisciplinary approaches in unravelling the complexities of ancient industrial landscapes.

Data Accessibility Statement

The data can be made available upon request from the corresponding author.

Notes

[1] Comprehensive details of our investigations including the survey methods and geospatial analysis of the slag heaps will be published in an upcoming article.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the Ministry of Heritage and Tourism of the Sultanate of Oman, including Sultan Al-Bakri, Khamis Al-Asmi and Suleiman Al-Jabri, for their collaboration and permission to conduct fieldwork in Oman. We thank the communities in Wadi al-Raki, Yanqul and Dhahir al-Fawaris for welcoming us through the course of our fieldwork in the region. We are grateful to the editors of this volume for their patience and feedback. Finally, we would like to thank the organisers of the Human-Environment Interactions in Ancient Arabia meeting held in Tübingen for producing a stimulating discussion and feedback on an earlier version of this paper.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.