Introduction

Imagine two classrooms in which the teachers are pressured by parents and school officials to help students achieve the highest levels of academic excellence, while dealing with anxious students facing environmental pressure to achieve high grades. In the first classroom, the teacher is highly stressed, and regularly fails to control her anxiety, and this adversely affects the classroom environment. In the second classroom, the teacher is able to flexibly control her cognitive and emotional state of mind, so that she can act as a calm mentor and create a pleasant and supportive atmosphere.

It is easy to see how both the teachers and students in these two classrooms would have very different outcomes. What is harder to see is which factors determine whether a teacher is more likely to be like the one in the first classroom or the second classroom. Given the stakes, this is a critical question. To date, most research concerned with these sorts of questions has focused on teachers’ academic background (Fung et al., 2017), experience (Brandenburg et.al, 2016), and salary (for a cross-national analysis, see Akiba et al., 2012). Recent studies, however, have highlighted the need to consider other factors (Escalante Mateos et al., 2021), such as the teacher’s affective functioning (Frenzel et al., 2021; Jeon & Ardeleanu, 2020).

In what follows, we consider the unique emotional demands of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) teaching in the K-12 classroom. We then present the process model of emotion regulation and discuss the effectiveness of emotion regulation-based intervention in educational settings. Next, we propose an emotion regulation framework for STEM teachers: STEM-Model of EmotioN regulation: Teachers’ Opportunities and Responsibilities (STEM-MENTOR). Our model targets STEM teachers because they may be more sensitive to school environments than non-STEM teachers (Wang et al., 2018), but it may be suitable for a wider population. STEM-MENTOR identifies contextual factors in STEM teaching that can influence the current emotional state of teachers and their decision as to which emotion regulation strategy to use. According to this model, STEM teaching-related stressors create a challenging situation for the implementation of effective emotion regulation. If STEM teachers cannot regulate their emotions, learning processes are impaired, and students adopt biased, inaccurate beliefs that shape their cognitive processing of STEM-related information and events. We conclude by explaining the implications of the STEM-MENTOR framework for theory and interventions that focus on cognitive-emotional processes.

Emotional Demands of STEM Teaching

Teaching is considered to be an occupation that involves ‘emotional labour’ (Hargreaves, 2000), causing teachers to experience intensified negative emotions, including stress and job dissatisfaction, and diminished psychological well-being (Chan, 2006). Work overload makes it difficult for teachers to focus on teaching (Ramachandran, 2005). Teachers and principals report frequent job-related stress at twice the rate of the general population of working adults (Steiner et al., 2022). Forty-six percent of K-12 teachers in the US report high levels of daily stress (Gallup, 2014; Greenberg et al., 2016), and 61% describe their work as always or often stressful (American Federation of Teachers, 2017). The high stress levels accompanying teaching have profound effects on teachers’ well-being (Buettner et al., 2016) and students’ educational outcomes (Burić, 2019; Harley et al., 2019; Herman et al., 2018).

Three common sources of stress are teachers’ perceptions of unusual working time (i.e., workload stress), students’ misbehavior, and high or unrealistic expectations of authorities and parents with respect to students’ achievement (Collie & Mansfield, 2022). These stressors are particularly relevant in the context of STEM education. STEM subjects are considered stressful to teach (Cui et al., 2018) and learn (Barroso et al., 2021; Becker et al., 2014). Teachers tend to express uncertainty about how to teach STEM courses that have integrated elements such as problem- or project-based learning. They also report uncertainty about how to design STEM courses without losing disciplinary integrity (Estapa & Tank, 2017; Johnson, 2012; Shernoff et al., 2017).

Yet the importance of STEM in Western societies (Hafni et al., 2020), now and in the future (Kaku, 2012), puts these courses at the forefront of education systems. The societal and personal significance (National Research Council, 2014) of STEM professions means STEM students and STEM teachers receive stressful implicit messages from their respective environments. For example, STEM students are pressured to achieve by their parents (Daches Cohen & Rubinsten, 2017). In addition, as the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) shows, many countries struggle with STEM performance. For example, Canada performs well internationally, but one in six and one in eight Canadian students did not meet the benchmark levels of mathematics and science, respectively (O’Grady et al., 2018). STEM teachers are expected to lead these students to high levels of success while being watched and criticized more than teachers of non-STEM courses (Bybee, 2013). Supporting students’ academic learning has been found to be a top-ranked source of job-related stress for teachers (Steiner et al., 2022), and STEM teachers are particularly affected (Cui et al., 2018). Not surprisingly, the teacher shortage crisis (Holmqvist, 2019) is more pronounced in STEM than non-STEM fields (Cowan et al., 2016).

We argue that teachers’ emotional state matters and emotion regulation skills should therefore be considered a crucial component of teaching opportunities and responsibilities (Braun et al., 2020; Frenzel et al., 2021; Jeon & Ardeleanu, 2020), especially in STEM fields (Bellocchi et al., 2017; Zembylas, 2002).

Emotion Regulation

There is general consensus that affective and cognitive processes are deeply intertwined (Gardner, 1995), including in STEM learning (Winne, 2019). One particularly important type of affect in this regard is emotion, which is generated when stimuli are meaningful or relevant to the individual, attract his/her attention, and are evaluated in relation to valued goals (Gross, 2015), suggesting the central role of appraisals in generating and shaping emotion (Conte et al., 2022). According to the appraisal-driven componential approach (Sander et al., 2018), five complementary and interrelated brain networks comprise the emotional brain: elicitation, expression, autonomic reaction, action tendency, and feeling. Emotion elicitation is dependent on an appraisal process, while the other components are generally considered to reflect the emotional response.

Emotional states depend on how the individual evaluates the situation (i.e., cognitive appraisal; Lazarus, 2001), and emotion regulation refers to whether and how the individual attempts to change an appraisal (Yih et al., 2019). Emotion regulation includes an array of processes (Rottenberg & Gross, 2003) by which the individual influences the type, intensity, duration, and expression of both positive and negative emotions (Gross, 2015). In the classroom, teachers tend to express positive emotions (Taxer & Frenzel, 2015) and are confident in their ability to communicate and up-regulate these emotions (Sutton et al., 2009). Compared to this, they are less confident in their ability to down-regulate their negative emotions (Sutton et al., 2009), although most of their regulation attempts are to down-regulate negative emotions by trying to hide them, while simultaneously faking positive emotions (Taxer & Frenzel, 2015; Taxer & Gross, 2018).

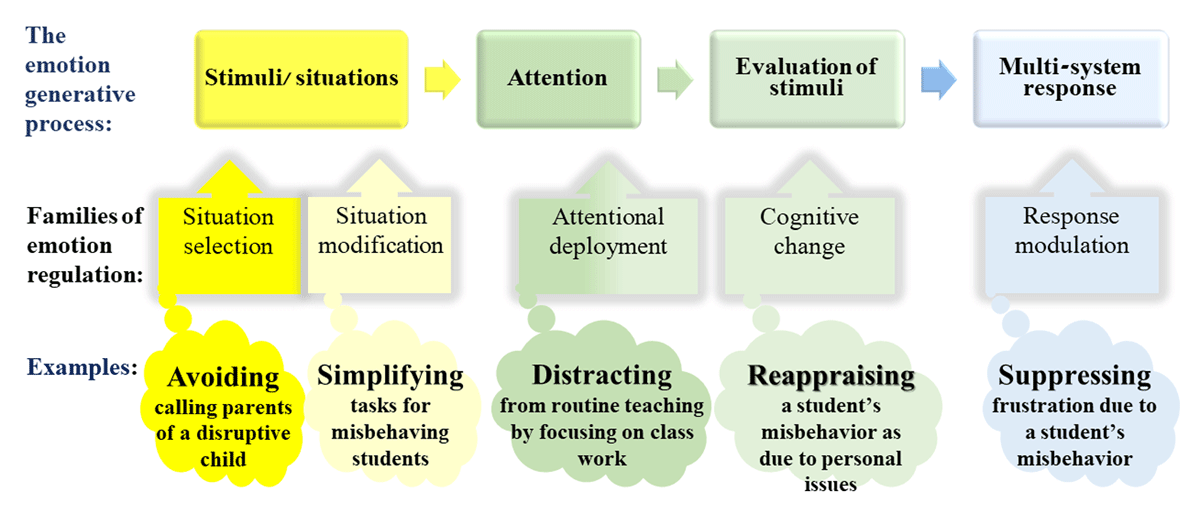

In the process model of emotion regulation, Gross (2015) distinguishes between regulatory strategies (Figure 1, second row) at various stages of the emotion generative process (Figure 1, first row). Two widely studied emotion regulation strategies are cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression (Bigman et al., 2017; Gross, 2015). Cognitive reappraisal constitutes an antecedent-focused strategy that involves the adoption of an objective perspective (reappraisal as rethinking; e.g., Sheppes & Meiran, 2008) or active attempts to adopt a positive perspective (reappraisal as reframing; e.g., Ochsner et al., 2002) in order to change the way the situation has been appraised (Gross, 2015). In contrast, expressive suppression is a response-focused strategy in which the individual attempts to conceal feelings, behaviors, and physiological activity (Gross, 2015).

Figure 1

Process model of emotion regulation (Gross, 2015) applied to a classroom context.

Difficulty regulating emotional states, or emotion dysregulation (Gross, in press) can manifest in emotion regulation failure (e.g., Kwon et al., 2018; Pizzie & Kraemer, 2017), emotion misregulation that does not well match the situation, and emotion regulation misexecution (e.g., Harley et al., 2019; Pizzie & Kraemer, 2021; Skaalvik, 2018; Xu et al., 2019). Drawing on the documented costs and benefits of different emotion regulation strategies in the process model of emotion regulation (Gross, 2013; Sheppes et al., 2015), each of these types of emotion dysregulation can be analyzed (Gross, in press).

At the intra-personal level, reappraisal has been found generally effective in reducing subjective negative affect (Balzarotti et al., 2017; Goldin et al., 2019; Gross, 2013, 2015; Troy et al., 2018) in math-related situations (e.g., Jamieson et al., 2016; Pizzie & Kraemer, 2021) and leads to more adaptive behavioral (Balzarotti et al., 2017; McRae, Ciesielski, et al., 2012; Schönfelder et al., 2014), physiological (Liu et al., 2019; McRae, Ciesielski, et al., 2012; Sammy et al., 2017), and neural responses to emotionally evocative events (Goldin et al., 2019; Schönfelder et al., 2014). Suppressing emotions is less effective than reappraisal (Gross, 2013, 2015) and is linked to increased strain and emotional exhaustion among teachers (Burić et al., 2021; Chang, 2013; Hülsheger et al., 2010; Taxer & Frenzel, 2015) and lower quality of instruction (Burić & Frenzel, 2021). At the inter-personal level (Zaki & Williams, 2013), teachers’ emotion regulation tendencies are thought to influence teacher-student interactions (Braun et al., 2019) and teachers’ supportive reactions to students’ emotions (Jeon et al., 2016; Swartz & McElwain, 2012). Moreover, by modeling effective emotion regulation, teachers can impact their students’ emotion regulation tendencies (Brady et al., 2018; Fried, 2011; Harley et al., 2019).

To effectively regulate emotion, the individual must be aware of the emotion and the relevant context, know and activate his/her emotion-regulatory goals, and make a skillful choice and implementation of an emotion regulation strategy while protecting the emotion-regulatory goal and adjusting it when/if the situation changes (Gross, 2013; Gross & Jazaieri, 2014). People may implement multiple regulatory strategies in a given emotional episode (Aldao & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2013), a phenomenon recently termed emotion polyregulation (Ford et al., 2019). It is not simply the depth of the emotion regulation repertoire that matters (Bonanno & Burton, 2013). The specific class of strategies included in the repertoire (Grommisch et al., 2019; Southward & Cheavens, 2020) and the ability to choose strategies synchronized with contextual demands and personal goals (emotion regulation flexibility; Aldao et al., 2015) also matter (Greenaway et al., 2018; Wilms et al., 2020). For example, choosing a less effortful distraction strategy has been associated with adaptive functioning among young children with low, but not high, working memory (Dorman Ilan et al., 2019). In this vein, there are times when it may be beneficial not to regulate negative emotions but to express them genuinely, due to the important role they may serve, such as guiding appropriate behavior and motivating the individual to improve his/her circumstances (Feinberg et al., 2020; Ford & Troy 2019). For instance, the use of reappraisal to control guilt and shame results in increased job satisfaction and decreased burnout, but also increased counterproductive workplace behaviors (Feinberg et al., 2020).

Reappraisal-Based Interventions in Educational Settings

There is growing interest in emotion regulation interventions in pedagogical settings in general and in STEM contexts in particular. Two types of these interventions can be found in the literature, one aimed at changing the interpretation of an emotional event (i.e., situation-focused; Yeager & Dweck, 2020) and the other targeting the response appraisals (i.e., response-focused; Jamieson et al., 2013). An example of event-focused intervention is the growth mindset (Ford & Gross, 2019; Yeager & Dweck, 2020) which teaches people that ability is not fixed but can be developed with effort, effective strategies, and support, leading to a reinterpretation of challenges as facilitators of personal development and controllable (Yeager et al., 2022). Three different large studies have replicated the efficacy of such interventions in improving achievements for low-achieving adolescents and increasing participation rate in harder math classes (Rege et al., 2021; Yeager et al., 2016, 2019). Response-focused interventions target the interpretation of arousal as a functional resource for psychological, biological, and behavioral outcomes (Jamieson et al., 2010, 2016; John-Henderson et al., 2015; Sammy et al., 2017). This line of research has demonstrated that teaching people about the adaptive benefits of stress arousal before a standardized test directly reduces adults’ and adolescents’ acute stress responses (e.g., math anxiety; Jamieson et al., 2016; Pizzie & Kraemer, 2021) and improves performance (e.g., Brooks, 2014; Jamieson et al., 2010; Pizzie et al., 2020; Rozek et al., 2019; but see Ganley et al., 2021).

In more recent work (Yeager et al., 2022), a self-administered online training module integrated the two main types of reappraisal manipulations by suggesting difficult challenges should be perceived as valuable opportunities for self-improvement (i.e., situation-focused), and physiological stress responses can fuel optimal performance (i.e., response-focused). This intervention showed a high level of promise in reducing evaluative stress and stress-related physiological responses and increasing psychological well-being among secondary and post-secondary students. Although these intervention studies did not focus on teachers, they suggest that reappraisal-based interventions may help teachers reappraise their view of stressful situations. Research has indicated the benefits of teachers› use of reappraisal, including in managing the stress associated with classroom activities (Chang & Taxer 2021; Jiang et al., 2016; Katz et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2016) and the overall teaching experience (Braun et al., 2019; Chatzistamatiou et al., 2014; Feldman & Freitas, 2021; Jeon et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2016; Moè & Katz, 2020; Oberle & Schonert-Reichl, 2016; Russo et al., 2020; Sutton & Harper, 2009; Swartz & McElwain, 2012; Yan et al., 2011). Emotion regulation interventions may change the ‘cognitive story’ that teachers tell themselves in relation to their experiences of stress and pressure, improving the way they deal with stressors in the future (Rozek et al., 2019). Stress reappraisal interventions may be particularly suitable for STEM teachers because they may experience increased stress at work (Schleicher, 2019) and often report intensified negative emotions (Cowan et al., 2016; Cui et al., 2018; Hembree, 1990).

A number of therapeutic approaches incorporate emotion regulation training to encourage awareness of emotions and the use of more adaptive emotion regulation strategies, including emotion regulation therapy (Mennin & Fresco, 2009) and acceptance of emotional responses (Roemer et al., 2008). These interventions can reduce teachers’ emotional dissonance between the experienced emotion and the emotional expression (Keller et al., 2014). This dissonance can be detrimental to teachers’ occupational well-being (Näring et al., 2006) and students’ emotions (Keller & Becker, 2021). Roeser et al. (2012) reviewed mindfulness training for teachers that included explicit instructions on emotions and stress and explained how to regulate them more effectively using mindfulness. An example is Cultivating Awareness and Resilience in Education (CARE; Jennings et al., 2019). Elementary school teachers who participated in mindfulness-based professional development through CARE reported both sustained and new benefits in well-being at a follow-up assessment almost one-year post-intervention compared to teachers in a control group.

Given the high stress levels accompanying the teaching (Cui et al., 2018) and learning (Barroso et al., 2021; Becker et al., 2014) of STEM subjects, the dearth of research-based interventions that incorporate aspects of reappraisal in educational settings is surprising. Most existing interventions were designed for students in STEM fields. These interventions have been found to have positive emotional (e.g., Jamieson et al., 2016; Pizzie & Kraemer, 2021) and academic outcomes (e.g., Brooks, 2014; Pizzie et al., 2020; Rege et al., 2021; Yeager et al., 2016, 2019).

STEM-MENTOR Model

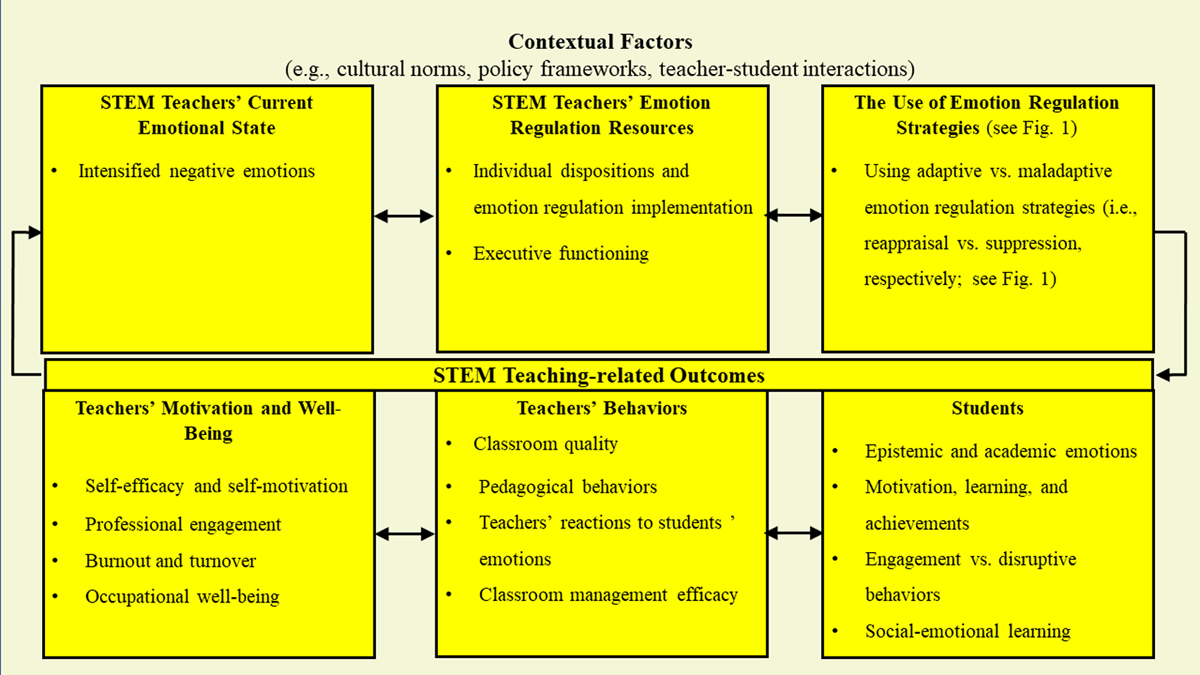

We argue that emotion regulation-based interventions targeting STEM teachers’ emotion regulation skills have the potential to create an emotionally supportive atmosphere in the classroom. Developing STEM teachers’ knowledge of and ability to regulate their own emotions will, in turn, help students develop regulatory skills and succeed academically (Denham et al., 2012; Taxer & Gross, 2018). Applying the process model of emotion regulation (Gross, 2015; Figure 1) to STEM teaching, we propose a framework (see Figure 2) suggesting that STEM teachers’ emotions and emotion (dys)regulation may have profound effects on their students’ cognitive processing of STEM-related information. Specifically, STEM teachers’ emotional expressions constitute top-down environmental-emotional knowledge that extends beyond the teachers to influence their students’ emotions and behavior. By modeling, teachers can affect the development of students’ emotion regulation tendencies (Brady et al., 2018; Fried, 2011; Harley et al., 2019; Zaki & Williams, 2013).

Figure 2

STEM-Model of EmotioN Regulation (STEM-MENTOR).

As shown in Figure 2, STEM teachers’ current negative emotional state (upper left square) disrupts their emotion regulation resources (upper middle square), leading to the use of maladaptive (vs. adaptive) emotion regulation strategies (upper right square). The broader context can also influence the teachers’ current emotional state and their decision as to which emotion regulation strategy to use (the external frame). The use of a maladaptive emotion regulation strategy negatively affects the teachers’ motivation and well-being (bottom left square), and this, in turn, creates a challenging situation for the implementation of effective STEM teaching-related behaviors (bottom middle square). The emotional experiences (via STEM environment) and emotional expressions (via emotion regulation) of STEM teachers also shape students’ STEM-related emotions and behaviors (bottom right square). In the following sections, we elaborate on each of these in turn.

Contextual Factors (External Frame)

An integrative affect-regulation framework (Troy et al., 2022) highlights the role of contextual features in the use of emotion regulation strategies, their short-term consequences, and the relationships between emotion regulation strategies and resilience. These contextual features include characteristics of the negative situation, such as intensity (Bonanno et al. 2015), controllability (Haines et al. 2016; Troy et al. 2013), timing, and duration (Epel et al. 2018). For example, reappraisal has been linked to increased resilience in relatively uncontrollable adversity but not in relatively controllable adversity (Haines et al. 2016; Troy et al. 2013) because reappraising controllable situations may decrease one’s motivation to change it (Ford & Troy 2019).

Broader aspects, such as one’s culture, have also been recognized as playing a key role in the use of emotion regulation strategies (Markus & Kitayama 1991; Mesquita 2001). For example, a meta-analysis revealed cultural differences in the effect of suppression on resilience (Hu et al. 2014), possibly due to the higher value of suppressing negative emotions in collectivistic-oriented cultures, such as Asian cultures, compared to more individualistic-oriented cultures, such as European ones (Markus & Kitayama 1991; Mesquita 2001).

Cultural norms on emotions related to STEM (Foley et al., 2017; Stoet et al., 2016) and their expression (Stoet et al., 2016) are especially relevant to our proposed theoretical framework. For example, math anxiety tends to be more prevalent in Asian countries than Western European countries (Lee, 2009). In addition, economically-developed and gender-equal countries show a lower prevalence of math anxiety (Stoet et al., 2016). Cultural norms also shape emotional display rules guiding teachers’ decisions either consciously or unconsciously about the appropriate expression of emotions in the classroom (Butler et al., 2007; Ford & Gross, 2019; Ford & Mauss, 2015; Hagenauer et al., 2016; Schutz et al., 2009). To promote a positive learning environment, for example, teachers are expected to display enthusiasm and caring behaviors in the classroom. In two studies, teachers who endorsed display rules were more likely to use suppression as their habitual way to regulate emotions (Chang, 2020; Taxer & Frenzel, 2015). A recent meta-analysis (Stark & Bettini, 2021) found teachers perceived emotional display rules as promoting their emotional support of students, contributing to their professional development, and fostering students’ academic development. Two-thirds of the teachers in Sutton et al.’s (2009) study reported less teaching effectiveness after expressing negative emotions, possibly leading them to suppress their negative emotions in the classroom.

Larger policy frameworks and school contexts may also affect teachers’ emotions (Jiang et al., 2021; Richardson & Watt, 2018). STEM teachers have experienced a stream of educational changes and reforms (Li et al., 2020; Stehle & Peters-Burton, 2019), and their emotions can be strongly affected by these changes (Jiang et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2013; Tsang & Kwong, 2017). If educational changes and reforms do not support their professional needs, goals, and development, they may have negative feelings (Jiang et al., 2021; Tsang & Kwong, 2017), and this emotional state, in turn, may have significant implications for teacher-student interactions (Aldrup et al., 2018; Braun et al., 2019; Collie et al., 2012; Frenzel et al., 2016; Whitaker et al., 2015). The quality of the teacher-student relationship has been found at affect students’ emotions (e.g., Jamal et al., 2013) and their academic performance (e.g., Malmberg & Hagger, 2009).

Yet teachers have a basic need for relatedness with their students (Spilt et al., 2011). Thus, the emotions of teachers and their relations with their students have effects on teachers’ physical and psychological well-being and also on their professional engagement, burnout, and turnover (Buettner et al., 2016; Harding et al., 2019; Montgomery & Rupp, 2005; Steinhardt et al., 2011; Taxer & Frenzel, 2015). Good relationships with students can have positive emotional impacts on teachers (Aldrup et al., 2018; Veldman et al., 2013), while negative relationships have been associated with negative affective outcomes (Gastaldi et al., 2014; Hagenauer et al., 2015). From the perspective of the transactional model of stress and coping (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984), the failure to establish a caring relationship with students leads to a negative emotional experience for the teacher because this goal is inherent to the teaching profession (Butler, 2012) and is at the core of teachers’ professional identity (van der Want et al., 2015).

STEM Teachers’ Current Emotional State (Top Left Box)

As a result of the contextual factors and the environmental pressures to achieve in STEM (Cui et al., 2018), academic anxiety is common in STEM fields (e.g., math anxiety) (Hart & Ganley, 2019), extending beyond the general population (Beilock & Willingham, 2014; Foley et al., 2017) to include those learning and teaching math (Ganley et al., 2019; Hembree, 1990). For example, students studying early education have higher levels of math anxiety than those in other fields of study (Hembree, 1990), possibly because of the minimal mathematics requirements to major in elementary education (Malzahn, 2013). However, it is likely that other teachers also experience math anxiety. Most teachers are women (Beilock et al., 2010), and women often are more emotionally reactive to numerical information (Daches Cohen et al., 2021) and display greater academic anxiety in STEM fields than men (Devine et al., 2018; Hart & Ganley, 2019). In general, math-related stimuli are associated with negative emotional reactions (Daches Cohen et al., 2021; Hart & Ganley, 2019). For example, exposure to math-related stimuli, like exposure to negative stimuli, leads to delayed and increased pupil dilation compared to neutral valence stimuli (Layzer Yavin et al., 2022). These findings hint at both the cognitive effort (Shechter & Share, 2021) and the emotional effort (e.g., pleasant and unpleasant stimuli, Bradley et al., 2008) required when exposed to math-related stimuli.

Teachers’ math anxiety has been found to impact their teaching self-efficacy (Gresham, 2008), confidence (Bursal & Paznokas, 2006), and pedagogical behavior (Ramirez et al., 2018), with a concomitant effect on their students’ achievements (Beilock et al., 2010; Ramirez et al., 2018; Schaeffer et al., 2021) and learning regardless of the educational level (Beilock et al., 2010; Schaeffer et al., 2021). The tendency of high math-anxious individuals to avoid math activities (Choe et al., 2019; Hembree, 1990) may cause high math-anxious teachers to provide lower quality math instruction (Akinsola, 2008) and to have lower expectations of their students, either explicitly or implicitly, than lower math-anxious teachers (Ramirez et al., 2018).

STEM Teachers’ Emotion Regulation Resources (Top Middle Box)

Under the transactional model of stress and coping (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984), teachers’ perceived emotions can be seen as not just a function of exposure to environmental factors, but also as a function of their ability to handle these emotions. Emotional stimuli capture attention; thus, cognitive effort is required (Banich et al., 2009). High executive functions, a set of higher cognitive processes that enable planning, forethought, and goal-directed behavior (Daches Cohen & Rubinsten, 2022), may serve as a protective factor for STEM teachers’ stress (Friedman-Krauss et al., 2014), enabling them to use adaptive emotion regulation strategies in response to emotionally arousing events (Cohen & Mor, 2018; McRae, Jacobs, et al., 2012; Quinn & Joormann, 2020; Wante et al., 2017). For example, neuroimaging studies found reappraisal was associated with the activation of the fronto-cingular network (Buhle et al., 2014) which is involved in domain-general executive control (Niendam et al., 2012). Against this background, several researchers found reappraisal ability (McRae, Jacobs, et al., 2012; Quinn & Joormann, 2020; Toh & Yang, 2022) and frequency (Wante et al., 2017) were linked to executive control of attention. Importantly, Toh and Yang (2022) found a significant link between common executive functions and reappraisal, even when covariates were controlled for, including intelligence, gender, depressive symptoms, age, and social desirability. Hence, the link between executive function and reappraisal seems to be a replicable phenomenon.

In a study relevant to our proposed framework, Daches Cohen and Rubinsten (2022) investigated the relations between math anxiety, emotion regulation, and executive control of attention using multiple two-stage hierarchical linear regression models. Their analyses indicated that the ability of math-anxious university students to use reappraisal in daily life was associated with their ability to avoid heightened emotional reactions when encountering math-related (i.e., threatening) but not negative (i.e., emotional distractions induced by irrelevant words with negative valence) information when executive control of attention was required (i.e., incongruent trials). It bears noting that the contribution of suppression to the regression model was not significant. Indeed, intervention studies have suggested that training in executive control of attention can lead to reduced use of maladaptive regulatory strategies, such as rumination (Cohen et al., 2015; Daches & Mor, 2014), and higher and better implementation of an adaptive reappraisal strategy (Cohen & Mor, 2018).

However, executive functioning is also generally thought to be impaired by stress (Shansky & Lipps, 2013; Shields et al., 2016; Uribe-Mariño et al., 2016), burnout (Deligkaris et al., 2014), and emotional fatigue (Grillon et al., 2015). For example, among preschool teachers, higher executive function skills were related to lower job stress (Friedman-Krauss et al., 2014). Stress affects multiple biological processes with known effects on executive functions, such as catecholaminergic activity and corticotropin-releasing hormone (Shansky & Lipps, 2013; Uribe-Mariño et al., 2016). Psychological factors may contribute to the effects of stress on executive function as well (Shields et al., 2016). For example, negative social evaluation associated with common stressors may result in rumination on perceived poor performance (De Lissnyder et al., 2012), leading to reduced executive control (Philippot & Brutoux, 2008).

Teachers’ emotions are also determined by individual dispositions (Schutz et al., 2006). Some STEM teachers may initially use maladaptive emotion regulation strategies (see Figure 1) as a core maladaptive skill. The literature has suggested specific neurobiological markers for the use of reappraisal, such as decreased resting-state functional connectivity (rs-FC) between the Middle Temporal Gyrus and occipito-parietal regions and between prefrontal and occipito-parietal brain regions and microstructural anomalies across white matter tracts connecting temporal, parietal, and occipital brain regions (Vitolo et al., 2022). In another line of research, personality traits such as low urgency and high distress intolerance, were linked to disengagement emotion regulation strategies (e.g., suppression) when exposed to high arousal negative affect (Sandel-Fernandez et al., 2022).

Some STEM teachers may have initial or core adaptive emotion regulation skills, but the stress (Shields et al., 2016; Vogel et al., 2016) and burnout (Golkar et al., 2014) in STEM teaching (Cowan et al., 2016; Cui et al., 2018) may disrupt their typical prefrontal cortical function, thus interfering with the successful execution of emotion regulation (Ochsner et al., 2012). For instance, in a sample of elementary and high-school teachers, negative emotions decreased the teachers’ reappraisal and coping abilities (Chang, 2013). These findings are consistent with previous research identifying the tendency to reappraise relatively low-intensity stimuli and to distract oneself from relatively high-intensity stimuli (e.g., Dixon-Gordon et al., 2015; Levy-Gigi et al., 2016; Shafir et al., 2015, 2016; Sheppes et al., 2011, 2014; Wilms et al. 2020). Compared to attentionally engaging and appraising emotional information (i.e., reappraisal), attentional disengagement from emotional information may be effective in modulating high-intensity emotions while requiring minimal cognitive resources (Sheppes, 2020).

In both cases, the environmental or contextual factors related to the STEM profession (i.e., stress and negative emotions) may affect STEM teachers’ motivation to regulate emotions (Yin et al., 2018). The motivation for emotion regulation can be hedonic or instrumental; the former includes approach and avoidance motivations to change the immediate phenomenology of emotion (Tamir, 2016; Tamir & Millgram, 2017), and the latter targets potential consequences of the desired emotional state (e.g., Tamir et al., 2015). Teachers’ hedonic goals for regulating emotions mainly focus on reducing the intensity of their own (intrinsic regulation functions) or their students’ (extrinsic regulation functions) experienced or expressed negative emotions (Taxer & Gross, 2018; Uzuntiryaki-Kondakci et al., 2022). Their instrumental goals are to increase teaching effectiveness and professionalism and manage students’ misbehavior (Gong et al., 2013; Sutton, 2004; Sutton et al., 2009; Taxer & Gross, 2018).

Use of Emotion Regulation Strategies (Top Right Box)

In the classroom, teachers use emotion regulation on a daily basis and even from lesson to lesson (Keller et al., 2014). They may have a wide repertoire of emotion regulation strategies (Chang & Taxer, 2021; Taxer & Gross, 2018), but findings show they most frequently use suppression (Gong et al., 2013; Taxer & Gross, 2018) and hide their negative emotions in classroom situations (Keller et al., 2014; Taxer & Frenzel, 2015). For example, teachers may use suppression to hide their negative emotions in response to students’ behavioral problems (Jeon & Ardeleanu, 2020; Jeon et al., 2016; Taxer & Gross, 2018).

Although suppression can be an effective form of emotion regulation for managing the classroom environment (Jeon & Ardeleanu, 2020), studies show teachers who use more suppression are less likely to have social support and more likely to have difficulty connecting emotionally with students (Gross, 2013, 2015) in the everyday school context (Jiang et al., 2016), and this could contribute to more negative emotions (Gross, 2002; Jiang et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2016). In addition, the use of suppression requires the individual to control the emotional expression and thus consumes cognitive resources (Gross, 2002; Gross & John, 2003), ultimately leading to increased stress levels and burnout (Chang, 2009, 2013, 2020; Jeon & Ardeleanu, 2020; Lee et al., 2016). Using a daily diary method, Lavy and Eshet (2018) documented the negative spiral of K-12 teachers’ negative emotions and their use of suppression.

In contrast, the use of reappraisal diminishes the negative influence of reencountered emotional information (Blechert et al., 2012; Denny et al., 2015). For instance, it has been shown that reappraisal-related behavioral (negative affect) and neural (right amygdala) effects can last for periods of up to a week, and these enduring neural changes do not require ongoing recruitment of cognitive resources (Denny et al., 2015).

STEM Teaching-Related Outcomes (Bottom Three Boxes)

Answering calls to incorporate an interpersonal perspective on emotion regulation, which involves regulation processes by and with the help of others (Zaki & Williams, 2013), researchers have recently drawn attention to the effects of teachers’ emotion regulation skills on both themselves and their students (Jeon & Ardeleanu, 2020; Taxer & Gross, 2018). Interpersonal emotion regulation may be particularly beneficial in the STEM classroom. Teachers can be immensely helpful in managing the emotions of learners exposed to sensitive and emotionally-loaded STEM content (Daches Cohen et al., 2021; Hart & Ganley, 2019; Layzer Yavin et al., 2022).

Teachers’ Motivation and Well-Being (Bottom Left Box)

Teachers’ emotions have been associated with self-efficacy (Klassen & Chiu, 2010) and self-motivation (Kazén et al., 2015; Parr et al., 2021) and have been shown to affect their professional engagement, burnout, and turnover (Bodenheimer & Shuster, 2020; Buettner et al., 2016; Burić et al., 2019; Taxer & Frenzel, 2015; Torres, 2020). In addition, teachers seem to be more prone to burnout when they frequently regulate emotions by using avoidance or suppression (Carson, 2007; Chang, 2013; Lee et al., 2016; Tsouloupas et al., 2010). Suppression has been linked with increased anxiety (Lee et al., 2016), strain, and emotional exhaustion among teachers (Chang, 2013; Moè & Katz, 2020; Taxer & Frenzel, 2015). Similarly, research on emotional labor in teachers found surface acting, which does not distinguish between faked, hidden, or masked emotions, was negatively associated with teachers’ well-being (Hülsheger et al., 2010; Kenworthy et al., 2014). Hiding, masking, or faking emotional expression can lead to an ongoing internal state of emotional dissonance between the experienced emotion and the outwardly displayed one (Keller et al., 2014). This emotional dissonance can be detrimental to teachers’ occupational well-being (Näring et al., 2006).

Secondary school teachers who use reappraisal to reinterpret stressful classroom situations have been found to demonstrate more positive emotions (Jiang et al., 2016), such as enjoyment (Lee et al., 2016), and manifest less emotional exhaustion (Donker et al., 2020), blunted physiological indicators of chronic stress (Katz et al., 2018), less negative affective experiences in the context of student misbehavior, and less suppression of their in-the-moment negative emotions (Chang & Taxer 2021). In general, teachers at various teaching levels with higher emotion regulation skills report a lower level of depressive and anxious symptoms (Mérida-López et al., 2017).

Teachers’ Behaviors (Bottom Middle Box)

The emotional state of teachers is arguably one of the key factors in creating a positive classroom environment (Yan et al., 2011). For example, preschool (Zinsser et al., 2018) and special education (Wong et al., 2017) teachers’ stress has been associated with classroom quality, teachers’ caregiving behaviors, and their relationships with students (Whitaker et al., 2015). When teachers regulate their negative emotions through reappraisal, teacher-student interactions may be more positive (Braun et al., 2019) and teachers may react in a more supportive way to students’ emotions (Jeon et al., 2016; Swartz & McElwain, 2012). Primary school STEM teachers who reported higher enjoyment during teaching sustained their positive attitudes when students struggled, and they spent more time on teaching (Russo et al., 2020), planning instruction, and evaluating teaching goals and teaching strategies supporting self-regulation (Chatzistamatiou et al., 2014).

By implementing reappraisal, teachers may demonstrate more effective pedagogical behaviors (i.e., autonomy supportive and structuring motivating styles; Lee et al., 2016; Moè & Katz, 2020) and greater classroom management efficacy (Sutton & Harper, 2009). Not surprisingly, teachers believe emotion regulation promotes more effective teaching and conforms to their image of an ideal teacher (Sutton, 2004; Sutton & Wheatley, 2003), possibly because of the effects of emotion regulation on the learning atmosphere (Yan et al., 2011). Taxer and Gross (2018) found elementary and secondary school teachers often described their own or their students’ negative emotions as impeding teaching quality and students’ learning, whereas positive emotions fostered teaching quality and student learning.

Students (Bottom Right Box)

A teacher’s emotional state can have a central role in students’ academic (Pekrun et al., 2009) and epistemic emotions (Arango-Muñoz, 2014) related to the emotional reaction of students during achievement situations and knowledge acquisition, respectively (Muis et al., 2018). Three aspects of this relationship may be distinguished.

First, teachers’ emotions affect students’ academic and epistemic emotions and perceptions (Becker et al., 2014; Frenzel et al., 2018; Keller & Becker, 2021; Muis et al., 2018; Rodrigo-Ruiz, 2016; Zinsser et al., 2013), a process often referred to as emotion transmission (Frenzel et al., 2018). Both teachers (Taxer & Gross, 2018) and students seem to be aware of the contagious effect of teachers’ emotions (Frenzel et al., 2009; 2018; Oberle et al., 2020). For example, elementary and secondary school teachers’ enjoyment was found to be positively related to students’ perceptions of teachers’ enthusiasm and enjoyment, which, in turn, was positively related to students’ enjoyment (Frenzel et al., 2018; Keller & Becker, 2021). Elementary students of teachers with poor occupational well-being were found to exhibit higher levels of morning cortisol, a biological indicator of stress (Oberle & Schonert-Reichl, 2016). A qualitative study demonstrated that secondary school teachers whose students perceived them as often experiencing negative emotions were hiding, masking, or faking their emotional expression (Jiang et al., 2016). In general, poor occupational well-being among teachers has been related to emotion dysregulation (Chang, 2013; Moè & Katz, 2020; Taxer & Frenzel, 2015). Students’ perceptions of teachers’ emotional dissonance can have negative effects on students’ emotions (Keller & Becker, 2021). In contrast, the degree to which teachers attempt to modify feelings to regulate their emotion (i.e., reappraisal; see Figure 1) has been negatively associated with students’ emotional distress (Braun et al., 2019).

Second, positive emotions in the classroom are at the core of students’ motivation, learning, and academic performance (Renninger & Hidi, 2015; Schubert et al., 2023). Epistemic emotions, such as surprise, confusion, and curiosity, are considered to have functional importance in STEM learning (Schubert et al., 2023; Schukajlow et al., 2017), and it appears that the teacher-student relationship may be a mediating factor (Harding et al., 2019). For example, enjoyment and happiness among preservice STEM teachers significantly improved their behavioral and cognitive engagement in STEM education (Kim et al., 2015). Teachers’ well-being (Malmberg & Hagger, 2009) and teacher-student relationships (e.g., Martin & Collie, 2019; Spilt et al., 2012), in turn, have been significantly associated with students’ long-term growth in academic achievement. Thus, social-emotional aspects of the teacher-student relationship are inherent in many instruction models (Kunter et al., 2013).

Third, teachers dealing with more disruptive classroom behaviors were found to experience poor occupational health and high levels of burnout (Herman et al., 2018; Rodrigo-Ruiz, 2016; Zinsser et al., 2013). Those teachers who also tend to hide, mask, or fake their emotional expression (Chang, 2013; Moè & Katz, 2020; Taxer & Frenzel, 2015) may transfer negative feelings and thoughts to their teaching and struggle with guiding and encouraging students’ expressiveness in challenging situations (Jeon et al., 2016). For example, students have to learn how to regulate and resolve confusion as it arises, as confusion is an unavoidable consequence of learning (Muis et al., 2018). In addition, based on the framework of interpersonal emotion regulation (Zaki & Williams, 2013), by modeling the use of maladaptive forms of emotion regulation, teachers may affect their students’ emotion regulation tendencies (Brady et al., 2018; Fried, 2011; Harley et al., 2019), building inaccurate inferences that do not support social-emotional learning (Braun et al., 2020; Jeon et al., 2019) and engagement (Burić & Frenzel, 2021; Kwon et al., 2017; Sutton & Harper, 2009) and increase emotional distress (Braun et al., 2020).

Reciprocal Relations between STEM Teachers’ Emotions and Emotion Regulation and STEM Teaching-Related Outcomes (Arrows)

Previous studies have suggested a bidirectional emotion transmission between STEM teachers’ emotions and teacher-related, teaching-related, and student-related outcomes. For example, teachers’ emotions and behaviors, teacher-student interactions (Frenzel et al., 2009, 2018, 2021), and students’ motivation and achievement (Chen, 2019; Uzuntiryaki-Kondakci et al., 2022) may influence the emerging emotions in teachers, with impacts on teachers’ self-concepts (O’Connor, 2008). Teachers’ self-concepts, in turn, may intensify the teachers’ positive emotions (Tsang & Jiang, 2018).

Accordingly, our model suggests that under conditions of stress, a negative cycle can be created: high STEM teachers’ stress levels → disrupted STEM teachers’ emotion regulation resources → STEM teachers’ emotion dysregulation → negative STEM teacher-related, teaching-related, and student-related outcomes → high STEM teachers’ stress levels, and so on.

In sum, emotion regulation (versus dysregulation), particularly reappraisal, is an important skill not only for STEM teachers (Jeon & Ardeleanu, 2020; Taxer & Gross, 2018), but also for their students (e.g., Braun et al., 2019; Oberle & Schonert-Reichl, 2016) and learning processes (e.g., Wong et al., 2017; Zinsser et al., 2018). Despite the environmental stressors in STEM teaching (Schleicher, 2019) and although STEM teachers may have negative feelings (Cowan et al., 2016; Cui et al., 2018; Hembree, 1990) that impair their ability to regulate emotion (e.g., Dixon-Gordon et al., 2015; Levy-Gigi et al., 2016; Shafir et al., 2015, 2016), STEM educators do not generally receive support to develop their own emotional skills (Patti et al., 2015) or those of their students (Reinke et al., 2011). The research on how teachers regulate their emotions and which strategies are effective in the classroom is sparse (Jeon & Ardeleanu, 2020; Taxer & Gross, 2018).

Discussion

Implications

To avoid the negative outcomes of teaching-related stress, it is necessary to improve the emotional trajectory at each step in our framework. Actions must be taken to reduce STEM teachers’ job stress or at least to protect against escalating stress. A recent study (Han & Hur, 2021) examining the reasons for STEM teachers’ transition to external industries suggested education policies need to provide more support in areas of career advancement and the creation of autonomous classroom environments. The degree of autonomy in the classroom may be affected by the frequent changes and reforms in STEM education (Li et al., 2020; Stehle & Peters-Burton, 2019), possibly leading to negative emotions among STEM teachers (Jiang et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2013; Tsang & Kwong, 2017). In a qualitative study (Fisher & Royster, 2016), secondary math teachers proposed ways to alleviate their stress, including more support with student discipline problems, fewer events and meetings after school hours, and less paperwork and extra duties. Future studies in this direction may shed further light on ways to reduce STEM teachers’ work-related stress.

Previous work on reducing teachers’ occupational stress has included organization-level (Naghieh et al., 2015) and person-level approaches (Iancu et al., 2018). The limitations of such interventions include the need for extensive financial and organizational resources (Awa et al., 2010) and small levels of efficiency (Iancu et al., 2018). Person-level approaches include knowledge-based (i.e., informational or psychosocial training; Cicotto et al., 2014), behavioral (i.e., techniques to reduce stress; Chan, 2011), cognitive-behavioral (i.e., cognitive training and practice in behavioral strategies; Ebert et al., 2014), and mindfulness-based interventions (i.e., focusing on the process of feeling and thinking; Beshai et al., 2016).

Although emotion regulation skills have far-reaching implications in the context of teaching and learning (Braun et al., 2019; Frenzel et al., 2021; Jeon et al., 2016; Jiang et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2016; Moè & Katz, 2020; Sutton & Harper, 2009), and teachers consider these skills to be extremely important (Sutton, 2004; Sutton & Wheatley, 2003), there is a lack of such interventions for teachers (Chen & Cheng, 2022; Patti et al., 2015; Reinke et al., 2011; Uitto et al., 2015). As mentioned above, evidence suggests suppression is the most frequently used emotion regulation strategy in classroom situations (Gong et al., 2013; Keller et al., 2014; Taxer & Frenzel, 2015; Taxer & Gross, 2018), even though teachers have a wide repertoire of emotion regulation strategies (Chang & Taxer, 2021; Taxer & Gross, 2018). Thus, teachers could benefit from understanding how to use reappraisal in different situations in the classroom context (Taxer & Gross, 2018). Specifically, they should be familiar with the ways to use reappraisal in response to student misbehavior, an emotion-evoking situation that frequently causes teachers to use suppression (Jeon & Ardeleanu, 2020; Jeon et al., 2016; Taxer & Gross, 2018).

Reappraisal-based interventions for STEM teachers may benefit from the existing studies on similar interventions among students. Such interventions have multiple advantages. First, managing emotions is an integral part of teachers’ work (Lee et al., 2016). Second, reappraisal-focused interventions have translatability from laboratory to field contexts (Jamieson et al., 2016). Third, the interventions are generally short-term, non-invasive, simple to implement, and require limited time and resources from participants, making them perfectly tailored to the educational setting. Fourth, the work is grounded on strong theory (Jamieson et al., 2010). Fifth, the interventions promote leading principles of the educational system: innovation and relevance in education and learning, autonomy and trust of teachers, as well as equal opportunities for children to acquire valuable skills even when they involve engagement in stressful pursuits.

Note that such interventions may need to be adapted in different cultures because cultural norms shape individuals’ perceptions about the appropriate expression of emotions (i.e., emotional display rules) and which emotion regulation strategies are adaptive or maladaptive (Butler et al., 2007; Ford & Gross, 2019; Ford & Mauss, 2015; Hagenauer et al., 2016; Schutz et al., 2009). In addition, regulating negative emotions is not necessarily adaptive; these emotions sometimes provide important information about the best response in a given situation (Feinberg et al., 2020; Ford & Troy 2019). Therefore, an effective therapeutic approach might emphasize the functionality of negative emotions and encourage an appreciation of their usefulness, alongside promoting a reappraisal of negative emotions that create a negative bias in thoughts and behavior (Feinberg et al., 2020).

Considerable evidence in the literature confirms the validity of the units in our STEM-MENTOR model indicating the critical role of STEM teachers’ emotion regulation knowledge and abilities. Simply stated, effective emotion regulation yields benefits to teachers and students alike. However, the model should be tested in follow-up studies, especially meta-analyses examining the variables simultaneously in different cultures and at diverse educational levels. Our model may be fertile ground for research and interventions that will promote STEM teachers’ well-being, thus improving students’ epistemological experience and achievements.

Conclusion

Because of the emotional demands of STEM teaching, STEM teachers face a wide range of stressors, including low student achievement and negative attitudes towards STEM subjects. Applying the process model of emotion regulation to the STEM teaching context, the STEM-MENTOR framework designates how contextual factors increase STEM teachers’ stress and how STEM teaching-related stress impairs emotion regulation resources, thereby promoting emotion dysregulation. Importantly, we emphasize the effects of STEM teachers’ intensified negative emotions and emotion dysregulation not only on themselves, but also on their students’ emotions, behaviors, and learning processes. Given the positive emotional and academic outcomes of stress reappraisal interventions in the STEM fields of study, we suggest that future research should focus on developing STEM teachers’ emotion regulation knowledge and abilities.

Ethics and Consent

Ethical approval and/or consent was not required.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Author contributions

LDC and OR were the lead authors in conceptualizing the paper and writing the manuscript. JG and OR contributed to all steps of conceptualizing the theoretical framework and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. The authors accept accountability for the final version of the manuscript.

Author Information

LDC is part of the Edmond J. Safra Brain Research Center for the Study of Learning Disabilities. She studies the role of emotion regulation in the development of math anxiety and whether adaptive emotion regulation strategies can be developed in math-anxious individuals. JG is a leader in the areas of emotion and emotion regulation and has published nearly 600 frequently cited papers on emotion regulation and received numerous teaching and research awards. By integrating behavioural, physiological, and brain measures, his research seeks to clarify emotion-related personality processes and individual differences. OR is part of the Edmond J. Safra Brain Research Center for the Study of Learning Disabilities. She is a leading figure in the areas of typical and atypical development of numerical cognition, learning disabilities (e.g., developmental dyscalculia and ADHD) and math anxiety.