(1) Overview

Context

The study of change and continuity in human societies over time has been a foundational concern in archaeology. In this context, time serves not only as an analytical dimension but also as a conceptual structure for organizing, comparing, and interpreting material remains. The need to temporally situate archaeological findings has historically led to the development of various periodization schemes, based on methods such as absolute dating (mainly radiocarbon), stratigraphic associations, typological sequences, and historical or geological correlations.

In Argentina -and particularly in the provinces of Mendoza and San Juan- archaeologists have produced temporal categories over more than a century of research. These definitions were generated by different research teams using diverse and often incompatible criteria, resulting in a fragmented chronological landscape. This situation has been reinforced by theoretical legacies inherited from culture-historical archaeology, which promoted linear and homogeneous visions of cultural change [1]. Although the use of absolute dating techniques has increased in the region in recent decades [23], little critical attention has been given to the temporal categories that structure archaeological interpretation, and almost no effort has been made to analyze their epistemological foundations.

Dividing time into units, labels, and scales raises at least two major challenges. First, temporal expressions in the regional literature tend to be presented as fixed and linear structures, which do not necessarily reflect the complexity of sociocultural processes. Time has often been treated as a passive organizational input, rarely questioned despite its centrality in the discipline [45]. Second, chronological categories lack intrinsic meaning: they are constructed and attributed by specific actors under specific conditions, and their interpretive value depends on those contexts [6]. As a result, no broad consensus exists, and parallel periodization models coexist in the archaeological literature.

Theoretical interest in the construction, use, and validation of periodization schemes remains limited within Argentinian archaeology. At the regional level, scholars have pointed to analytical fragmentation caused by limited dialogue among research traditions [7]. This has led to diverging narratives and chronological frameworks, with little effort to articulate shared structures. Gil [8] has emphasized the importance of developing models to understand how human populations responded to environmental and cultural changes over time, noting the need to analyze the temporal structure of variability and the different scales at which such processes occurred. For instance, even well-recognized phenomena such as the Inca presence in the region are described through several different and partially overlapping period labels in the literature, which refer to equivalent temporal spans but lack a shared nomenclature (see dataset IDs 69–77 in the PDF source files).

The dataset presented here is intended as a methodological response to this problem. It comprises a systematic compilation, standardization, and digital curation of temporal definitions employed in archaeological research from Mendoza and San Juan provinces. Based on a comprehensive review of the archaeological literature of both provinces, this study identifies 93 temporal periods attributed to 32 scholarly authorities. Each entry was curated following the data model of the PeriodO Project, an open gazetteer for historical and archaeological periods designed for Linked Open Data publication [9]. Entries include a preferred label, temporal coverage (expressed in ISO 8601 dates), spatial scope, and a verifiable bibliographic source.

This initiative does not aim to impose a single canonical chronology. Instead, it provides a shared infrastructure to preserve, trace, and reuse the diverse temporal frameworks produced by the regional archaeological community. By integrating the dataset into PeriodO, it becomes possible to approach this heterogeneity through an interoperable model that promotes efficient data management and supports the development of a more open, connected, and epistemologically self-aware archaeological science. The use of ISO 8601 with a year zero further enables direct comparison with chronological schemata employed in other regions beyond Argentina.

Spatial coverage

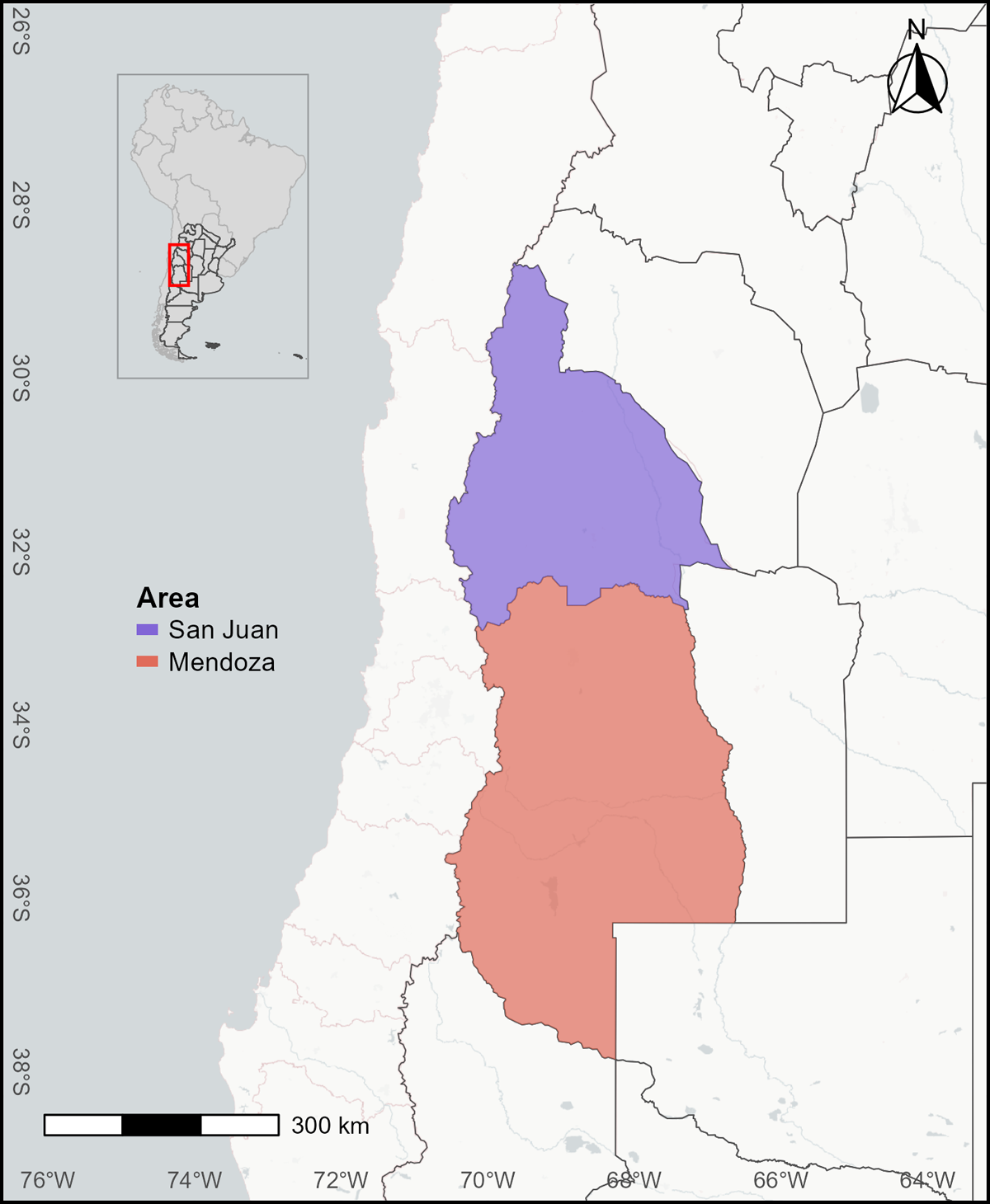

The dataset focuses on archaeological period definitions from the provinces of Mendoza and San Juan, located in west-central Argentina. These territories were selected not on the basis of fixed administrative boundaries, but due to their shared environmental conditions and factors that reflect both the cultural similarities shared by the human groups that inhabited the region and the historically distinct research trajectories and theoretical filiations developed by the archaeological community. Both provinces are situated along the eastern slopes of the Andes and have historically served as zones of interaction between highland and lowland populations, with archaeological sequences shaped by diverse cultural affiliations and research agendas.

In the literature, these regions have been variably conceptualized as part of the Central Andean region of Argentina and Chile, which includes the eastern and western Andean slopes between 31° and 35° south [10], or more specifically as the Central-Western Argentine subarea (Centro-Oeste Argentino, COA), a transitional zone between Andean and Patagonian cultural spheres within the broader Southern Andean Area [1112]. Additionally, the southern part of Mendoza overlaps with what has been defined as the Norpatagonian Mendocino-Neuquina subarea, a zone with transitional archaeological features [13].

Rather than adhering to rigid cultural or ecological boundaries, this project adopts a flexible spatial framework that centers on the archaeological research production specific to Mendoza and San Juan (Figure 1). This approach follows Gil and Neme’s [14] argument that segmentation schemes often reflect scholarly agendas more than the lived spatiality of past populations. By organizing the dataset around these two provinces, we ensure a consistent scope that facilitates the systematic curation of temporal definitions while avoiding reductive or externally imposed classifications.

Figure 1

Spatial location of the provinces of San Juan and Mendoza.

In order to ensure semantic interoperability and facilitate reuse in Linked Open Data (LOD) environments, the spatial scope of the dataset is aligned with standardized geographic identifiers. Specifically, the provinces of Mendoza and San Juan are linked to persistent URIs from the TGN.1,2 These thesaurus entries offer machine-readable geographic metadata and hierarchical relationships that support integration into ontologies and digital heritage infrastructures.

Northern boundary: –30.300000

Southern boundary: –37.500000

Eastern boundary: –66.000000

Western boundary: –70.900000

Coordinate reference system: WGS 84. Coordinates follow the decimal degree format used in the TGN.

Temporal coverage

This dataset spans archaeological periods from approximately –9550 to 1875, corresponding to ca. 11,500 BP to AD 1875. In this dataset, “BP” is expressed using the conventional reference year AD 1950. These values reflect the earliest and latest boundaries among the 93 period definitions curated in the dataset. Chronological expressions follow the Gregorian calendar using ISO 8601 extended year notation, where negative values denote years prior to the Common Era (with 0 corresponding to 1 BCE). This nomenclature is employed because the dataset adheres to the temporal standard used by the PeriodO Project [9]. We explicitly follow the ISO 8601 recommendation that includes a year zero, consistent with PeriodO’s implementation.

However, this temporal range does not derive from a unified chronological framework. Rather, it reflects the complex development of archaeological research in Mendoza and San Juan, shaped by a variety of theoretical traditions, institutional contexts, and methodological approaches over more than a century. The temporal categories compiled here were generated under diverse and often incompatible criteria-ranging from typological classification and historical documentation to geological correlations and absolute dating techniques such as radiocarbon and thermoluminescence [6].

Early archaeological studies in both provinces were deeply influenced by ethnohistorical approaches and focused on assigning artifacts to specific ethnic or cultural identities, often using historical documentation rather than stratigraphic or contextual data [16]. These traditions were especially dominant until the mid-20th century, under the influence of the culture-historical approach and, to a lesser extent, evolutionist and diffusionist models [10111215].

In Mendoza, this led to the creation of culture-historical sequences such as the Coroneles culture, defined in three lithic phases [15], and the Atuel culture, divided into four chronological units based on data from La Gruta del Indio [16]. Parallel typological debates surrounded the Agrelo and Viluco cultures [13]. In San Juan, similar efforts led to the formulation of synthetic models like the Ansilta and Los Morrillos cultures, as well as typological phases such as Punta del Barro and the classification of ceramic styles associated with Angualasto, Calingasta, and Aguada traditions [101721].

From the 1980s onward, regional archaeology diversified. New theoretical and methodological frameworks, such as historical materialism [6], biogeographical models [2], and Bayesian chronologies using absolute dates [3], enriched the field. This shift also produced novel temporal classifications in areas like historical archaeology, with new sequences developed for colonial Mendoza based on archaeological excavations [18], and in Norpatagonian contexts, where cultural-historical frameworks were reconstructed using multi-site data [19]. In addition, some researchers adopted geological categories (e.g., Late Holocene, Middle Holocene) as temporal anchors [2], while others employed arbitrary temporal blocks (e.g., 1000-year or 500-year intervals) to structure chronologies in the absence of diagnostic cultural or stratigraphic markers [2223]. Meanwhile, inherited schemes from Northwest Argentina (such as the Early, Middle, and Late periods) continued to be used [7820].

As a result, the temporal landscape of archaeology in Mendoza and San Juan is characterized by fragmentation, overlapping categories, and a lack of standardization. The dataset offers a structured yet pluralistic representation of this diversity, enabling researchers to trace and critically reuse these temporal models in an open and interoperable format.

(2) Methods

Steps

The temporal definitions compiled in this dataset were extracted from a previously constructed corpus of archaeological literature focused on the provinces of Mendoza and San Juan. Each entry was incorporated into the PeriodO client (https://client.perio.do/), which organizes archaeological period definitions following a nanopublication data model [92425].

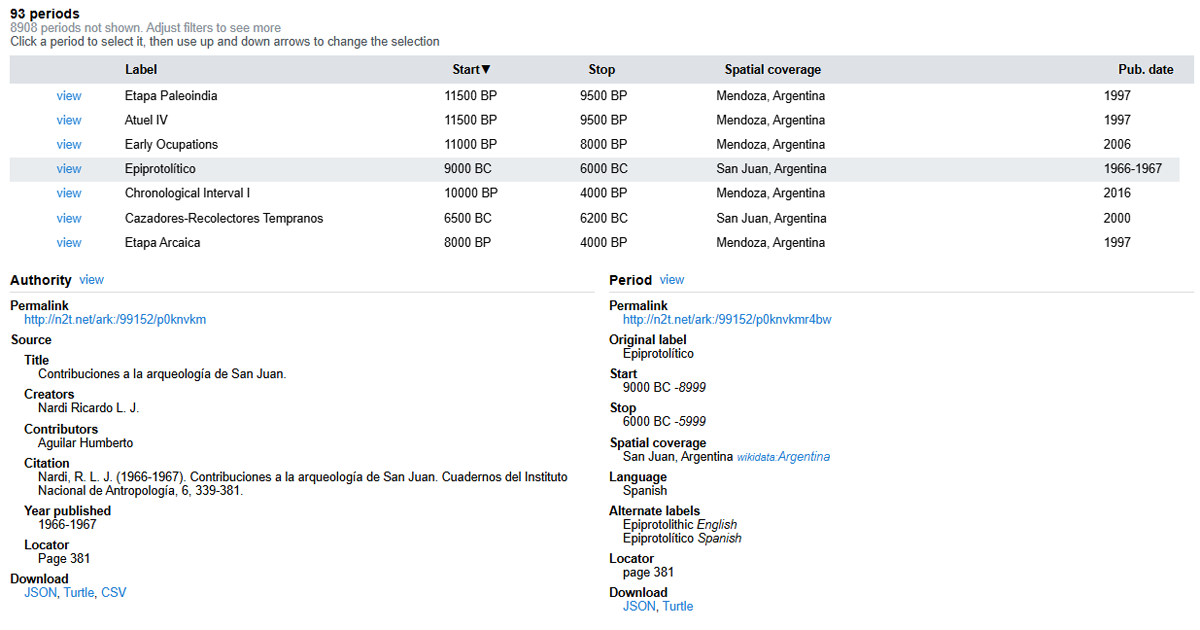

In order to be indexed in PeriodO, each period must meet a set of minimum requirements: (1) a clearly defined name or label; (2) an explicit temporal coverage, even if approximate; (3) a defined spatial scope; and (4) a verifiable bibliographic source (Figure 2) [9]. These requirements align with the three core components of a nanopublication: a precise assertion, the provenance of the statement (who, when, where), and the provenance of its extraction (who curated it and by what method) [25].

Figure 2

Example of a selection of periods from the dataset corresponding to Mendoza and San Juan in the PeriodO Project. In this case, the Epiprotolithic period is shown, where the minimum required metadata for its indexing can be observed (name, temporal coverage, spatial scope and source), along with additional information available and downloadable on the platform.

The spatial scope recorded for each period follows the original wording used in the sources and is expressed through the provincial denominations “Mendoza” and “San Juan”. In PeriodO, these spatial entities are linked to their corresponding Wikidata items, mirroring the platform’s current practice of aligning place definitions with external authority records.

Dates were normalized using the ISO 8601 standard. OxCal v4.4 [26] and the ShCal20 calibration curve [27] were used exclusively for Period 5 [28], which is the only case in the dataset based on radiocarbon determinations. In cases where period boundaries were expressed in vague terms -such as “second half of the 16th century”- the OWL-Time ontology was applied to produce computable intervals. One example included in this dataset is the Colonial period defined by Ots et al. [29], whose original expression was formalized in PeriodO as starting in the year 1551.

Sampling strategy

The dataset includes only those temporal definitions that specify both a start and end date expressed in calendrical format. These quantitative categories were selected from an extensive corpus of archaeological literature on Mendoza and San Juan, comprising more than 500 bibliographic sources in various formats (articles, books, theses, conference proceedings, and grey literature). Although the entire corpus was reviewed, only 32 sources contained explicit, quantitatively defined period frameworks or formulations compatible with the OWL-Time ontology that met PeriodO’s minimum requirements, while many others did not present temporal schemes suitable for formalization. All of the data collection and systematization was carried out manually, through direct reading and extraction of each temporal definition. Only period definitions with both a clearly established temporal framework and verifiable bibliographic attribution were included in the dataset.

Quality Control

Each temporal definition included in the dataset was manually curated from its original bibliographic source. Entries including either new authorities and sets of definitions, or edits to existing authorities or definitions, were submitted to the PeriodO platform through its web client using an ORCID-authenticated account as proposed modifications (“patches”) to the canonical dataset.

Once submitted, these entries were reviewed by the platform’s editorial team. If a patch met the minimum requirements along with properly formatted spatial and temporal coverage extracted from the original source, it was approved and merged into the canonical dataset.

Upon validation, both the authority record and each individual period definition are assigned globally unique and persistent URIs within the Archival Resource Key (ARK) system. These identifiers follow PeriodO’s hierarchical structure, in which the base ARK is extended with a suffix for the authority and another for the specific definition, with final resolution handled by the n2t resolver. This ensures compliance with the platform’s content and formatting standards and provides a clear and documented trail of data provenance and editorial approval [9]. The importance of using persistent identifiers in archaeological contexts is particularly significant, as they help communicate aspects of context, avoid errors and misinterpretations, and facilitate integration and reuse across datasets [30].

Constraints

The main limitation encountered during data collection was the restricted accessibility of numerous bibliographic sources. A significant portion of the archaeological literature on Mendoza and San Juan existed in the form of undigitized printed materials or unpublished documents. Consequently, data acquisition required extensive manual effort, including in-person consultations with colleagues, direct communication with authors, and physical visits to local libraries and archives.

This limitation occasionally delayed the identification and verification of temporal definitions. Nevertheless, once the sources were obtained, the processes of data extraction and standardization followed a consistent methodology, ensuring the integrity of the final dataset as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1

Overview of the workflow used to extract, normalize, and prepare period definitions for inclusion in the dataset.

| STEP | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| 1. Source identification and attribute verification | Selection of publications containing explicit archaeological period definitions for Mendoza and San Juan. |

| 2. Manual data extraction | Extraction of the four mandatory elements: period name, temporal coverage, spatial scope and bibliographic reference. |

| 3. Chronological and metadata standardization | 3a. Chronological normalization: Standardization of temporal boundaries into ISO 8601 extended year notation. This included calibration of the only radiocarbon-based definition in the corpus (OxCal v4.4 + ShCal20) and the formalization of vague expressions (e.g., “second half of the 16th century”) into computable intervals using OWL-Time conventions. |

| 3. Chronological and metadata standardization | 3b. Structuring of core metadata for PeriodO ingestion: Organization of fields into the PeriodO data model (original label, temporal span, spatial coverage, language, bibliographic source and basic relations such as has parts). |

| 4. Quality control and editorial validation | Review by PeriodO editors to ensure adherence to platform standards. At this stage, system-generated fields (alternate labels, page locators, download formats, authority links) are incorporated, and a persistent ARK identifier is assigned upon approval. |

(3) Dataset description

Object name

Cultural chrono-categories from Mendoza and San Juan, Argentina – a single deposit that bundles six files:

temporal_definitions_mendoza_sanjuan_ESP.csv – main table, Spanish column names and labels.

temporal_definitions_mendoza_sanjuan_EN.csv – same table, English version.

tables_periodos_ESP.pdf – easy-to-read table of periods and their bibliography (Spanish).

tables_periods_EN.pdf – same content in English.

README_bilingual.html – user guide in both languages.

CHANGELOG_bilingual.html – file documenting all updates and version history of the dataset in both languages.

Data type

This resource records primary archaeological information derived from over 500 sources that define one or more cultural periods.

To help users navigate the table, the fields are organised into four thematic groups (Table 2).

Table 2

Field groups and key columns in temporal_definitions_mendoza_sanjuan_ESP.csv and temporal_definitions_mendoza_sanjuan_EN.csv.

| GROUP | MAIN FIELDS | PURPOSE |

|---|---|---|

| Identification | period (persistent URI), label/etiqueta, link source/enlace a la fuente | Gives each period a unique global identifier and a human-readable name. |

| Geographic | spatial coverage/cobertura espacial, getty tgn | Indicates the province and country where the period is used. |

| Chronological | start/inicio, stop/fin | Defines lower and upper bounds in Gregorian calendar years according to the extended ISO 8601 standard (negative values = BCE, with year 0 corresponding to 1 BCE), consistent with PeriodO’s implementation. |

| Relational | broader periods/períodos generales, narrower periods/subperíodos | Places each definition in a hierarchy so that broad cultural phases and local sub-phases can be queried together. |

The PDF tables reproduce the same information but add the full bibliographic reference next to each period for readers who prefer a printable format.

Format names and versions

CSV, PDF, HTML.

Creation dates

Data were systematized, curated and indexed from 2023 to 2025.

Dataset Creators

Humberto Aguilar designed the data structure, collected the period definitions, and normalised them in PeriodO; Andrés Darío Izeta reviewed and validated the dataset.

Language

Spanish and English.

License

CC-BY-NC 4.0 International – licence applied to the full package in the Digital Repository of the National University of Córdoba.

CC0 1.0 Universal – licence under which the normalised records are released within the PeriodO Project gazetteer.

Repository location

Digital Repository of the National University of Córdoba – http://hdl.handle.net/11086/556497

Publication date

The dataset was published in the repository on 21/07/2025.

(4) Reuse potential

This dataset is the first fully normalised catalogue of 93 archaeological periods for Mendoza and San Juan, and builds on the earlier standardisation for central Argentina published by Izeta & Aguilar [31]. Released in open CSV and PDF formats and preserved in the RDU repository, it is conceived as a living resource: the local scholarly community continually produces new dates, re-examines cultural sequences and refines period names, so the file is meant to grow and change alongside that ongoing work. As fresh information appears in articles, theses or field reports, researchers can incorporate it into PeriodO and refresh the RDU package, keeping both platforms synchronised.

Besides its regional focus, this dataset challenges archaeologists to critically examine the ontological frameworks underlying temporal classification systems. Disciplinary traditions, project agendas and local histories have produced heterogeneous — and at times conflicting — chronological schemes; several entries here refer to the same cultural span while bearing different names. By lining up those variants in a single, citable table, the catalogue offers a transparent baseline for dialogue, critical comparison and reciprocal adjustment, without pressing for a unified framework. Because the package is openly licensed (CC-BY-NC 4.0) and version-tracked in RDU, any specialist can propose updates, correct errors or add new definitions, ensuring that the resource remains current and useful to future research. In addition, the deposit provides a coherent and referenceable collection of authorities for the region, which strengthens its role as a curated set that can be cited and reused in broader comparative work.

Notes

[1] Mendoza: Getty Thesaurus of Geographic Names, http://vocab.getty.edu/page/tgn/1001427.

[2] San Juan: Getty Thesaurus of Geographic Names, http://vocab.getty.edu/page/tgn/1001519.

Acknowledgements

We thank the scholars who have built the archaeology of Mendoza and San Juan, the colleagues who generously shared unpublished information, and the staff of all the libraries who helped digitise and send paper materials. We are also grateful to Ryan Shaw and Adam Rabinowitz for their ongoing guidance on uploading data to PeriodO and for their words of encouragement throughout this effort.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.