Introduction

In recent years, there has been an increase in the prevalence of research focused on the use of video games as a pedagogical tool for the instruction of history, archaeology, and classics (Brown 2008; Clark Tanner-Smith and Killingsworth 2016; McCall 2013; Mitchell and Savill-Smith 2004; Squire and Jenkins 2011; Young and Slota 2017). This trend reflects a growing recognition of the potential of video games to engage and educate students in a way that transcends traditional teaching methods by making students a more active part of the learning process (Squire, DeVane and Durga 2008). The intersection of history, archaeology, and classics in this context is particularly promising, as these disciplines provide a rich reservoir of content that can be effectively conveyed through interactive and immersive gaming experiences (McCall 2013, 2016, 2019; Mol et al., eds. 2017; Politopoulos et al. 2019b; Reinhard 2012). This burgeoning area of research not only underscores the evolving landscape of educational paradigms but also signifies a substantial shift in the way educators and institutions are adapting to the dynamic needs and preferences of modern learners.

This project seeks to better understand students’ perspectives regarding the use of video games as a teaching tool in the classics classroom. In particular, it seeks to highlight the impact of video games on student satisfaction and on student perceptions of learning. To accomplish this, this paper provides a systematic case study focused on a single classics course at the University of Arizona (Classics 160B1: Meet the Ancients: Gateway to Greece and Rome) in which students had the option to choose either a video game-based assignment sequence or a traditional reading response assignment sequence. After the course, students were provided with short quantitative and qualitative survey in which they could reflect upon their learning experience, and these results were then compared between the students who opted for the video game-based assignment sequence and those who chose more traditional assignment sequence.

While the impact of the learning modality on effective learning has been debated (Aslaksen and Loras 2018), several studies suggest that tailoring teaching modalities to students’ preferred modes of learning can have a substantial impact on the achievement of outcomes (Dekker et al. 2012). As a result, developing a better sense for the way in which students perceive the use of video games as a teaching tool, both its strengths and weaknesses, provides the potential to impact the achievement of learning outcomes in archaeology, history, and classics courses.

Literature Review

Video Games as Pedagogical Tools

The idea behind using video games as a pedagogical instrument is to meet students where they currently are. The prevalence of video games and gaming has increased dramatically in recent years, and the industry as a whole has recently surpassed a valuation of $100 billion, catering to more than 2.5 billion gamers globally (Gough 2018). University campuses in particular are hubs for gaming activity, with over half of students engaging in video games occasionally or regularly, as shown by a comprehensive study involving 1,000 student responses from 27 universities (Jones 2003). These habits are cultivated at younger ages, with Cole (2012) highlighting that high-schoolers, on average, play approximately 12 hours of video games per week. Moreover, the frequency with which games have been used as teaching tools has been increasing as well, with Takeuchi and Vaala (2014) suggesting that nearly three-quarters of teachers have used video games in their pedagogy at least once during a five-year span in the 2010s. Most university students, then, have experience playing video games, and many play video games for fun in their free time.

Educational research spanning two decades has demonstrated the advantages of integrating video games into classrooms (Brown 2008; Barr 2018; Gibson, Aldritch and Prensky 2007; Khine 2011; Pitarch 2018, Squire and Jenkins 2011; Young and Slota 2017), particularly in history and archaeology (Mol et al., eds. 2017; Mol et al. 2016; Politopoulos et al. 2019b; Reinhard 2012; Reinhard 2018). These studies have suggested several benefits with regard to learning. Empirical evidence suggests that video games help foster students’ emotional connection toward the subject material, provide them a platform for iterative feedback and skill honing, promote dynamic engagement, nurture innovative cognitive processes, and enable the broadening of perspectives (Griffiths 2002; Mitchell & Savill-Smith 2004). This assertion finds reinforcement in a meta-analysis conducted in 2016, encompassing 57 studies centered on video game pedagogy, which substantiated a noteworthy and statistically meaningful enhancement in the attainment of educational objectives among students who participated in digital gaming interventions, as compared to their non- participatory counterparts (Clark, Tanner-Smith, and Killingsworth 2016).

These findings have been supported within the fields of archaeology and history. In 2008, a study conducted by Squire, DeVane and Durga exhibited that students engaging with the historically-embedded game series Civilization expressed heightened enthusiasm for historical subject matter in contrast to their peers who were exposed to conventional text-based and lecture-based instructional approaches. Over the course of the last decade, McCall and other scholars have consistently advocated for the utility of video games in inciting interest within the field, replicating historical scenarios, and facilitating dynamic involvement in historical decision-making (McCall 2013, 2014, 2016, 2019). Mol et al.’s work, The Interactive Past: Archaeology, History and Video Games (2017), presents a compelling argument regarding games’ efficacy in conveying cultural knowledge and engaging users actively with archaeological sites. Minecraft, for instance, has been employed to give users the ability to construct and explore cultural heritage (Mol et al. 2016: 14; Boom et al. 2020: 39–41), and Politopoulos et al.’s (2019b) RoMeincraft lets students reconstruct infrastructure and explore a digital version of the Roman frontier.

There are, however, significant obstacles to implementing games in the classroom. Financial constraints arise due to costly software (around $60 per student) and premium hardware requirements for graphics-intensive games, which can exceed $300. Steep learning curves and mature content ratings pose challenges, with games like Red Dead Redemption 2 demanding considerable time and often containing violent elements. Moreover, balancing fiction with factual content presents pedagogical difficulties, as seen in everything from Civilization to Assassin’s Creed.

Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey

This case study uses Ubisoft’s 2018 epic adventure Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey as the focal point for its video game assignment sequence. The game itself is an action-adventure role playing game, and the user plays as a protagonist caught in the middle of the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta (431–404 BCE) within the larger setting of the Classical Greek world.

Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey has garnered both critical acclaim and commercial success. Within its debut week, it sold more than one million copies, contributing to the series’ cumulative worldwide sales of over 140 million copies to date. The game has received nominations for numerous industry awards and has consistently received laudatory reviews, with particular emphasis on its meticulously crafted setting (Metacritic 2018). The game’s intricate depiction of the ancient Greek terrain, encompassing cities, temples, and everyday life is particularly noteworthy. This accomplishment is not merely a driver of the game’s excellence or popularity; it also highlights the potential utility of this immersive digital environment as a novel means to engross students in the landscape of ancient Greece.

However, the game was designed for commercial success, resulting in the inclusion of several elements that raise issues concerning its suitability for educational settings. The levels of historical accuracy within the game exhibit a notable variance. While the portrayal of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia largely adheres to the archaeological and historical evidence, other architectural details lack comparable accuracy. The Parthenon, for instance, is presented as a Doric temple replete with triglyphs, metopes, and pedimental sculptures; however, this sculptural arrangement deviates from established archaeological and historical evidence. Furthermore, the characterization of historical figures prioritizes alignment with the game’s narrative progression over strict historical precision, and the game’s focus on an individual protagonist results in a style of warfare that markedly contrasts with the phalanx-based combat of Archaic and Classical Greece. While certain locales such as Athens offer an immersive urban environment, others, such as the plethora of wooden forts, are criticized for their repetitive and generic nature (Politopoulos et al. 2019a: 319–22). Moreover, the inherent violence embedded within the game poses a substantial impediment to its applicability in pedagogical contexts, and the central questline can require over 50 hours to complete, making it difficult to use, and the engagement in optional quests necessitates an additional gameplay duration exceeding 100 hours (HowLongToBeat 2019). In fact, it demands more than five hours of gameplay to reach the introductory credits alone.

Ubisoft has aimed to solve these concerns through the introduction of the Discovery Tour mode in its development efforts. This mode offers game players unrestricted access to the entire virtual world, eliminating the warfare component while enabling exploration of the digital landscape (Dingman 2019). Moreover, it presents curated guided tours led by archaeologists and historians, encompassing diverse locales, urban areas, and landmarks, with the explicit aim of educating interested gamers and students. Perrine Poiron, a consultant on the Assassin’s Creed: Origins Discovery Tour mode, underscores the meticulous research and curation underpinning the creation of these educational segments (Poiron 2021). While some scholars perceive this as a valuable educational instrument (Hotton 2018), others critique the Discovery Tour mode for its diminished interactive quality compared to the core gameplay (Mol 2018). While it was not mandated that students in this study use the Discovery Tour mode or modules, they were made aware of the feature and its ability to open the complete map and remove the element of violence from the gaming experience.

Preliminary scholarship on the use of Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey as a teaching tool has produced mixed results. Essentially, scholars are grappling with Politopoulos et al.’s (2019a) question, “do we engage in meaningful play with the past, or are we simply assassinating our way through history? (2019a: 317).” Gilbert’s 2019 study that assessed student feedback regarding video game-based learning suggested that students were indeed more engaged in the material but often missed opportunities for deeper investigation. And Politopoulos et al. (2019a: 322) suggest that the action of Assassin’s Creed is more akin to a blockbuster movie than to a simulation of historical social, economic, political, or military dynamics. These studies suggest, then, that the game holds potential as a useful pedagogical tool, but it is necessary to thoughtfully design learning activities for students rather than rely solely on the game’s main storyline or Discovery Tour mode.

Methods

This case study took place during the Fall 2021 semester within my asynchronous online course, Classics 160B1: Meet the Ancients: Gateway to Greece and Rome. The course itself is a freshman-level general education course. At the University of Arizona, this meant that it was both high enrollment (266 students) and that most of those students were fulfilling university-level requirements rather than taking the course to pursue a career in classics. The course runs annually both in in-person and online modalities. As long as instructors pursue the same learning outcomes, they have the freedom to tailor the content and teaching methods to their own strengths and interests within the classical world.

The goal of the study was twofold. First, it aimed at gathering qualitative and quantitative student feedback regarding the use of video games as a teaching tool in the university classroom. Second, the study aimed to evaluate the relative strength of this new teaching method by comparing it to more traditional pedagogical methods.

To accomplish this, the 266 students enrolled in the course were given the option to complete one of two assignment sequences. The video-game based sequence asked students to complete a series of 6 assignments in which they would explore some component of the game, read an excerpt from an ancient text, and write a 300+ word essay. The traditional sequence asked students to complete a series of 6 assignments in which they focused solely on reading an ancient text and writing a 300+ word response. Thus, in both sequences students were asked to engage with ancient texts and produce 300+ word written responses.

While the course was designed to produce identical deliverables (i.e., 300+ word written essays) for each assignment sequence, the topics of each module’s written assignment often differed between the two sequences. This was, in large part, because the game did not have content adjacent to the topics that had been previously developed for the traditional assignment sequence. For example, in Module 2, the traditional assignment sequence that’s been in use for the past several years has students read an excerpt from the Iliad and then reflect on what makes it “epic” in nature. This does not translate particularly well to the content within Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey, which is focused on the Peloponnesian War rather than the Trojan War. Thus, the Module 2 topic within the video game sequence focused on religious practice at the site of Delphi with students reading excerpts from Pausanias’ Description of Greece. Standardizing the content of these assignment sequences would be a productive goal for future studies since it could help reduce variance due to content topic and better isolate the impact of video games as a pedagogical tool for teaching archaeology.

By running parallel assignment sequences within a single course, and by constructing similar assignment deliverables, the aim was to better isolate the impact of video games on student perceptions of the teaching and learning process. The secondary goal, however, was more pedagogically focused than research-based; that is, I sought to provide students with the opportunity to undertake an educational experience tailored to their personal learning styles (Ambrose et al. 2010). Future studies may improve upon this by having all students complete both assignment sequences. However, due to time constraints and the fact that these written assignments were only one facet of the work students completed for the course, students in this class only pursued one sequence or the other.

After completing the course, students were sent an IRB-approved survey that consisted of 14 questions, including yes/no, Likert scale, and free response questions. These questions were meant to get a sense for prior video game experience, assignment sequence enjoyment, and specific characteristics of each assignment that increased student learning. The survey included the following questions:

Do you play video games outside of this class? (yes/no)

About how many hours a week, if any, do you spend playing video games for fun? (numerical)

Have you played any games in the Assassin’s Creed series before this class? (yes/no)

Have you played Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey before this class? (yes/no)

Which assignment sequence did you complete? (binary)

How much did you enjoy the assignment sequence you chose? (1 = a little, 10 = a lot)

How much do you feel you learned through your assignment sequence? (1 = a little, 10 = a lot)

What do you think worked particularly well about your assignment sequence? (free response)

Which module’s assignment did you enjoy the most? (1 through 6)

Why was that assignment your favorite, and how did it help you learn? (free response)

What do you think did not work very well with your assignment sequence? (free response)

How would you modify your assignment sequence for future classes? (free response)

What are your overall thoughts on your assignment sequence? (free response)

Are there any other games you think would work well to help teach about the past? (free response)

Student responses from the two assignment sequences were then compared to assess their relative enjoyment, self-perceived learning, and qualitative thoughts on the assignment sequence of choice. The goal of this comparison is to isolate the marginal benefit or cost of employing video games as a teaching tool in a more controlled and systematic manner.

Results

Quantitative Student Feedback

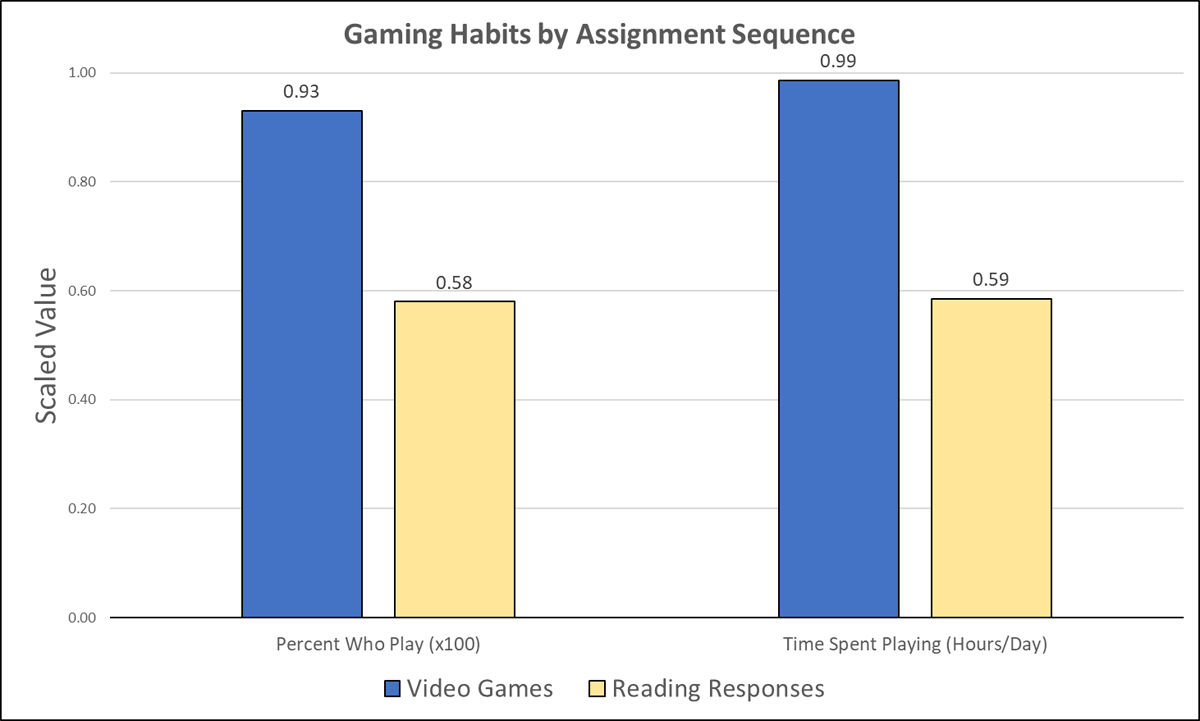

Out of the 266 students in the course, only 26 students (9.8%) completed the survey. These responses were relatively evenly split between students who completed the video game assignment sequence (n = 14) and the traditional assignment sequence (n = 12). The first clear takeaway from these responses is that students appear to have selected their assignment sequence based on their previous gaming experience (see Figure 1). Nearly all students who chose the video game sequence (93%) played video games recreationally outside of class, while only about half (58%) of students who chose the traditional sequence played games for fun. Likewise, more than 1/3 of students (36%) who chose the video game sequence had played Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey, while none of the students who chose the traditional sequence had played the game. In short, previous gaming experience appears to have a major impact on the appeal of the video game learning modality.

Figure 1

Gaming habits by assignment sequence. Graph: Robert Stephan.

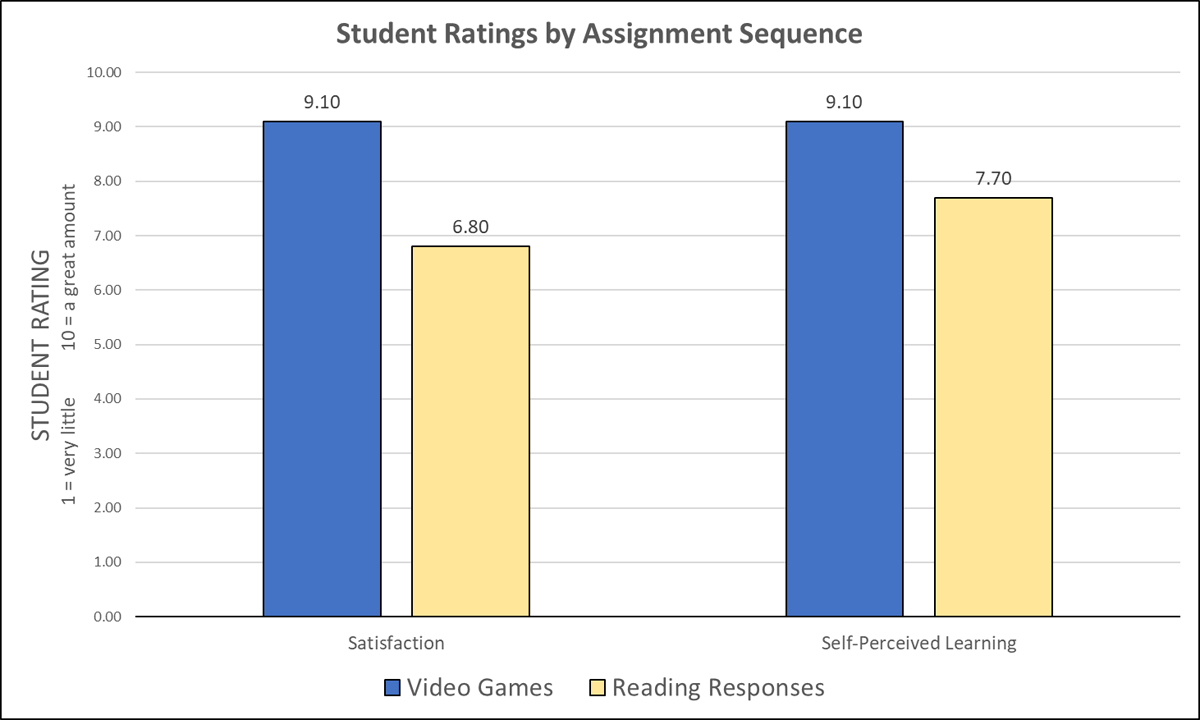

Quantitative student responses suggest strong levels of student satisfaction and self-perceived learning from those who opted for the video game assignment sequence (see Figure 2). The question regarding the degree to which students enjoyed their respective assignment sequences led to an average score of 9.1 from the video game students and an average of 6.8 from the traditional assignment sequence students. Average scores regarding students’ self-perceptions of learning led to similar results, with video game students producing a score of rated the amount they learned from the assignments as a 9.1 out of 10, while the traditional assignment students felt like they learned a 7.7 out of 10. It is important to reiterate that these are self-perceptions of student learning rather than differences in the actual achievement of learning outcomes, but nonetheless the differences seem substantial in scale.

Figure 2

Student ratings by assignment sequence. Graph: Robert Stephan.

Qualitative Student Feedback

The free responses questions help illuminate the specific aspects of the video game assignments that students found both beneficial and frustrating. The most common aspect of the video game assignments that was noted by students as a positive contributor to their learning experience was the visualization of the ancient Greek natural and built environment (5 of 9 students). One student noted, “I think that the ability for us as students to explore the ancient world worked really well for the assignments. Actually seeing the different ruins and temples in the game really helped with learning about the ancient world.” Another commented, “The way the game was set up allowed me to be fully engaged and for once, learning history was not boring [and] seeing actual [the] representation of Greece allowed me to retain the information more. The Discovery Tour was very useful which allowed me to just learn and explore.”

The second most common positive quality for the video game sequence centered on the interactivity of the assignments (3 of 9 students). One student said, “I felt as if I retained the information learned throughout the assignments more than what I traditionally would with just a textbook reading. The video game assignment allowed me to get more interactive and I’ve always found that to help me more than anything when learning something new. It was a breath of fresh air for the semester!” While another stated, “I enjoyed the fact that it was different and more interactive than any other class I’ve done.”

In terms of drawbacks, students highlighted difficulties in finding correct locations within the virtual gaming environment (2 of 9 students). One student, for example, commented, “If I had to choose something I’d say it could improve by giving us a general idea of where exactly to go within the explorative setting just in case some people find it hard to know where to look.” Another noted, “The one thing I thought worked the least would have been at one point I couldn’t find a certain location but with the help of my husband I was able to find it within the game. Truthfully that wasn’t even that much of a hassle though, it’s just all I could think of to be a bump in the road.”

Students also found the alignment between some of the video game assignments and the lecture material to be misaligned at times (2 of 9 students). One mentioned, “I thought the early AC:O (Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey) assignments lined up very well with the course content every week. I thought it was an extension of our lectures and helped further our learning. I personally enjoyed the final three assignments the most, but it felt more disjointed from the lecture content that was more focused on the Romans.” A second student observed, “This course is split in two halves. Essentially an emphasis on Greece and another emphasis on Rome. Is it possible to incorporate gameplay that could accommodate Rome? Maybe the total war series have a historical battle of Cannae.”

Discussion

The results from this student survey suggest video games hold potential to increase student satisfaction and learning within the realm of history and archaeology courses. Student scores regarding their enjoyment of the assignments were substantially higher for the video game assignment sequence than the reading response sequence, and students also self-reported higher levels of learning from the video game assignments. These preliminary results align well with previous studies on the use of video games as teaching tools, especially the conclusion that students appear to find video games as useful for building interest in and satisfaction with the course (Mol et al. eds. 2017). Clark, Tanner-Smith and Killingsworth’s 2016 meta-analysis, for example, noted similar trends with student feedback with regard to these characteristics.

Despite this potential, the limited scale of this study raises several new questions and directions for future investigation. Simply increasing the scale and scope of the study would, of course, be beneficial. It would be useful, for example, to see whether these trends hold if the entire class of 260+ students were to respond to the survey, especially for those students who do not regularly play video games for enjoyment. Further study on that issue is certainly warranted. Since this was tested in a lower level, asynchronous online course, it would be helpful to know whether these trends hold at different levels and in different modalities. Do we see similar results in upper-level courses or in in-person or hybrid courses? Finally, one of the most important next steps would be to test the impact of video game integration on the actual achievement of student learning outcomes, rather than student perceptions of learning. Adžić et al.’s 2021 study suggests that this may, indeed, produce similar results, but running a similar study using these assignments would be a useful next step.

There is certainly room for far more robust research on the topic. The preliminary results of this study, however, suggest that integrating gaming into the history classroom has the potential to dramatically impact students’ perceptions of both enjoyment and learning of the course material.

Reproducibility

The data used in this study are available online: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10120150.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank the Department of Religious Studies and Classics and the College of Humanities at the University of Arizona for their generous funding that allowed me to participate in the conference that led to this publication. I would also like to thank the reviewers for their helpful and insightful comments. The paper is undoubtedly better because of your efforts and feedback. Most of all, I would like to thank the students who participated in this study for their hard work and thoughtful feedback. My teaching will improve as a result of your efforts.

Ethics and Consent

This research has been performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The methodology and anonymous student survey used to collect data was approved by the University of Arizona Internal Review Board on August 21, 2021 under project number 2108132953.

Competing interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.