1. Introduction

This study examines open space urban commons (UC) in Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries in the context of post-socialist governance and the implications of neoliberalism’s failures during and after the transition (Haase et al., 2019; Zupan and Büdenbender, 2019). The concerned UC include large city squares, neighbourhood squares, playgrounds, plazas, and parks, and have different levels of openness to the public, as well as different forms of ownership and co-governance. Such spaces are complex UC and are often contested in the frame of urbanisation trends and market-led processes of city-making (Harvey, 2018; Foster and Iaione, 2016; Sassen, 2015). They are also contested for what they represent as constructs of values and identities.

Open space UC in the CEE, like the context in which they evolve, exhibit diversity and equivalences. In CEE countries, commons have a particular history rooted in custom and tradition and challenged by imposed social collectivism during socialist times. In cities, open spaces, usually labelled as ‘public,’ have become subject to urbanisation and commodification after the socialist period, with governments often failing to protect them or deliver adequate related services. As a result, urban actors have responded in various ways; some turning to activism in the form of street protests, rooted in criticisms of government policy and the socio-economic model it promotes, and others, mostly neighbours, cooperating for the maintenance of their urban gardens. The resulting commoning practices are relatively small-scale, self-governing experiments unrelated to the current systems of urban governance. Indeed, studies of UC in CEE countries (Toto et al., 2021; Čukić and Timotijević, 2020a; Tomašević et al., 2018; Łapniewska, 2017; Ondrejicka et al., 2017; Poklembová et al., 2012; Borčić et al., 2016) reveal that the governance of urban spatial commons (including squares and parks) is far from common and is marked by detachment between local governments and user groups.

A significant part of the CEE UC literature is concerned with the ideology of the commons and the societal struggles to re-appropriate the city and its resources, enclosed by state and powerful economic actors (Čukić and Timotijević, 2020a; Tomašević et al., 2018). Indeed, UC may have the potential to address some of the key drawbacks and disadvantages of the neoliberal system. Cases of place-based, bottom-up commoning practices are documented, which produce examples of struggles for an alternative society – one that is just, fair, sustainable, and socially regulated (Helfrich, 2012). Other cases, however, are limited to neighbourhood actions or to social movements against the [local] government.

This paper examines UC governance within the current setting of the state and market in CEE rather than as a governance-shifting alternative that is independent of its context (Huron, 2017; Jerram, 2015; Helfrich, 2012). We also take the position that the study of UC should pay closer attention to the [often-antagonistic] relationship between the UC and the local government as a means to inspire/provoke innovations in local governance in CEE. Foster and Iaione (2016) and Iaione (2016) examine the relationship between UC, government, and the role of law, placing UC cases in a broader framework of city co-governance. They also provide the first contribution to design principles for UC. Dellenbaugh-Losse et al. (2020), amongst others, describe cases of various UC and strategies for creating and maintaining them. Toto et al. (2021), looking at UC in the CEE, argue that local governments can learn from community practices of commoning and create the conditions for further commoning to take place in the city, building on the system of values that commoners attach to space.

This paper develops a hypothesis that, against the rich and long pre- and socialist history of sustained collective land use in CEE, the region’s UC bear uncommonness to date. Uncommonness relates to the already known diversity of the national contexts and of the cases, but the examination of the latter reveals its dimensions in terms of rarity, exceptionality, and unevenness and asymmetry. Former collective relations, forcefully established in the socialist era, serve as the very fabric on top of which neoliberal forms of urban development take place. As Golubchikov et al. (2014) argued, these conditions of mutually coexisting neoliberal and socialist legacies, in particular in urban spaces, create “hybrid spatialities” – “‘strange’ geographies that function according to the tune of capital but often conceal their capitalist nature with socialist-era ‘legacies’” (ibid., 618). In particular, the pockets of collective governance create spaces where private and state interests are interwoven with collective ones in lucrative ways, and the diversity of these scenarios across the post-socialist space is vast.

In some UC cases, the existing co-governance frameworks that were left over from the post-socialist transition are challenged/corrupted by political interests, characteristic of the post-socialist context – namely, a mixture of powerful private interests with top-down state apparatus. In other cases, these co-governance frameworks are yet in their infancy, but their appearance is being disputed by the political elites as commoners are seen as competitors in political regimes and bearers of progressive values.

We initiate from a context of people participating in co-governance scenarios but not defining them as ‘commons.’ Indeed, there is no unified framework for commons, or collective governance across post-socialist spaces despite the long traditions of collective ownership, erasing the definition of the commons from the legal and public field. Moreover, collective relations within urban spaces are often seen as remnants of the socialist era, which paints them in a bad light in the public sphere in terms of their viability and longevity.

While discussing uncommonness, this paper unpacks the existing social relations that could be studied from the collective governance standpoint. The purpose is to examine and discuss the governance of open space UC in CEE, including relations between local governments and commoners, revealing the UC’s uncommonness. This is illustrated with depictions of commoning in and of urban open space in Albania, Montenegro, Poland, and Russia, investigating co-governance shaped by internal and external factors. In our analysis of UC internal factors, we look at four dimensions of sharing that mutually connect commoners, resources, and commoning practices into the full UC spectrum. The external factors come from the broader context, producing dynamics of different significance for every CEE country, but summarised under the transformation of societal process and urban space since 1990, governmental shifts, and socialist legacies. In transiting between external and internal factors, commoners have to collaborate with partners (particularly local governments) and bridge their mindset with that of cities, states, and markets, while the commons have to withstand enclosure (Sevilla-Buitrago, 2015). Finally, the paper highlights the need for further investigation of open space UC within and between CEE countries, not only to critically assess findings on uncommonness but also to contribute to the knowledge and repository of cases for this region.

2. Open Space Urban Commons – internal factors

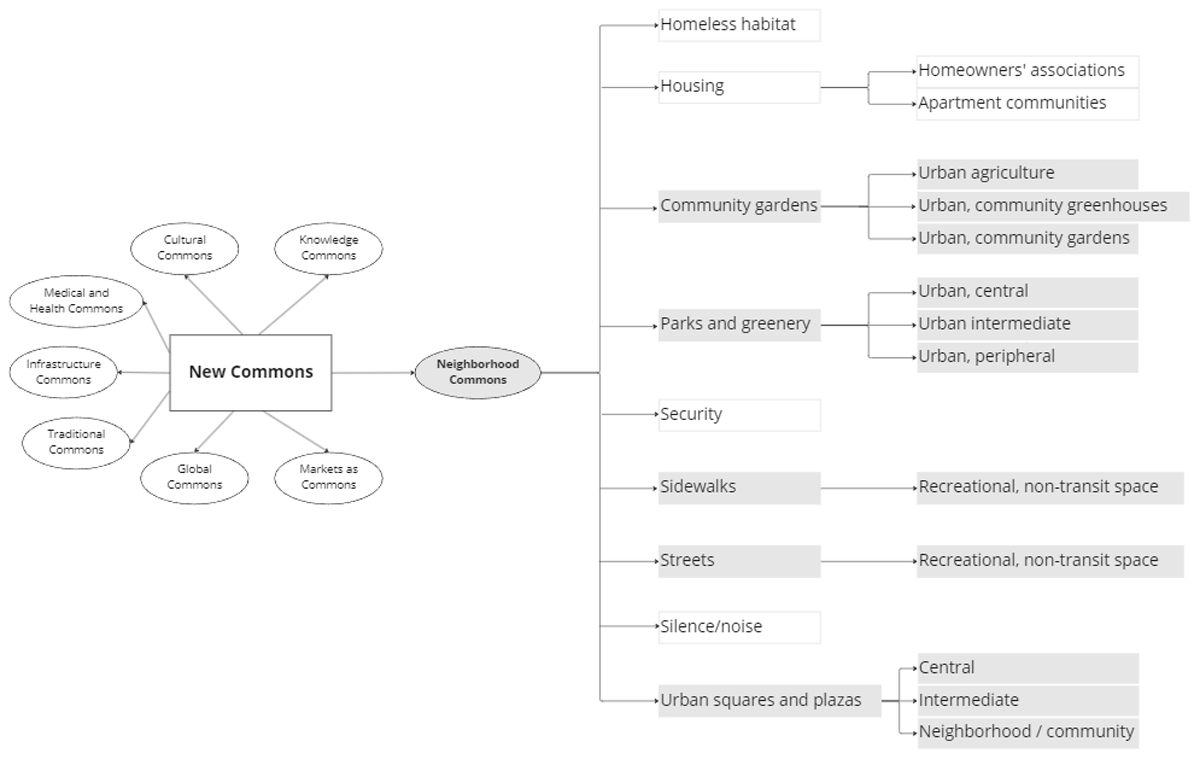

Open space, as discussed in this paper, is a specific type of UC (Feinberg et al., 2021; Čukić and Timotijević, 2020a; Arvanitidis and Papagiannitsis, 2020; Moss, 2014; Hess, 2008), and is territorial (Bauwens and Niaros, 2017). These spaces (Figure 1) are located within the urban fabric and have multiple uses and a large variety of design rules with multiple implications within urban governance, which is specific for UC with a visible and tangible spatial character (Davy, 2014; Needham, 2006). Their spatiality relates to their placement within the urban core as ‘void’ nodes of magnetism, intending to unify the solid and resonating character across various spatial scales.1 Open space is ubiquitous and ephemeral in the city. It is created and recreated physically and socially, developing its own identity, and is subject to rescaling processes due to governance shifts and socio-economic and political changes. The spatiality of open space defines the intertwined relations between the space, commoners, and commoning in at least four dimensions: shared property, shared use and effects, shared management and shared identity and values.

Figure 1

Typologies of Urban Open Space as Urban Commons*.

Source: Authors, adapted from Hess (2008) and Feinberg et al. (2021).

*The types of neighbourhood commons after Hess (2008) and Feinberg et al. (2021) that are subject to this paper are highlighted in grey. We have added urban squares and plazas to the diagram, as explained in the paper.

Shared property and space. Open spaces are perceived as of different importance in the city depending on their functions and on who owns the pertaining property rights (access, use, maintenance, exclusion, etc.). Chan (2019) suggests that common spaces differ from public spaces, as in the latter case, the state maintains the resources, while in the former, it is the commoners. Colding et al. (2013) argue that if users hold only access rights, they are not commoners, and the space is classified as within the public realm. However, in the case of urban open spaces, usually recognised as ‘public,’ the legal ownership becomes secondary to the feeling of ownership resulting from the use of the space and from the right not to be excluded (Blomley, 2020) making users feel that they can enhance stewardship behaviour without actually holding legal rights to the land (Peck et al., 2021). Referring to the bundle of rights2 (Ostrom, 2003; Schlager and Ostrom, 1992), all UC spaces are open access, while the other rights may vary. Withdrawal rights usually come under sets of rules that vary according to the space. People may use the space in central plazas for fairs, protests, artistic events, exhibitions, or street vending while complying with local government rules. In a neighbourhood square, it is common for children to play without permission from the residents, assuming quiet hours are respected. Hence, legal ownership suggests management arrangements, but only to a certain extent, and it cannot exclusively define whether a resource is an urban common or not (Williams, 2018; Marella, 2017; Iaione, 2016).

Shared use and effects. The governance of open space UC is subject to the scale of the resource as seen in its shared use and in the shared effects and benefits borne as commoning happens across various scales (Ostrom, 1990a; Kip et al., 2015; Harvey, 2011). For instance, the central plaza has a radius of attraction that is often beyond the scale of the city. Users beyond city limits are mostly visitors, while the citizens living close to the space may develop a connection to it and identify themselves with the space. They may identify the city through that particular space and appropriate the space in several little ways every day. They also pay taxes and/or fees for its management and would withdraw less value if the space suffered from abuse or a lack of maintenance. In a neighbourhood square, the users’ catchment area is smaller though it still has malleable boundaries.

Shared management. In the case of neighbourhood squares, management is usually shared between the local government and the residents, and in certain cases, more responsibility is taken by the latter. The role of the residents depends on their degree of ownership (access, withdrawal, management, exclusion, and alienation) and on the type and strength of attachment they have to space and the community bonds (Toto et al., 2021; Dellenbaugh-Losse et al., 2020; O’Brien, 2012). In central squares, citizens typically expect that local governments organise maintenance and management, paid out of their taxes. With the increase of scale and free-riding potential, the management of open spaces becomes complex, if not muddled. But, this complexity and the [often] blurry lines between rights and responsibilities of different groups of owners and users contribute to these spaces being fertile grounds for the development of commoning practices and modalities of co-governance.

Shared identity and values. In depicting commoners, we refer to their multiple relations in commoning as co-management (Dellenbaugh-Losse et al., 2020) or as a social practice (Harvey, 2011; 2008). Commoners share the resource by using it, managing it, claiming it, and even struggling over it (Čukić and Timotijević, 2020a; Huron, 2017; Iaione, 2016; Ferguson, 2014); they engage in the “production and reproduction of commons” (Kip et al., 2015, p. 13), sharing values, norms, needs, (Čukić and Timotijević, 2020a; O’Brien, 2012) and holding the right to the space as set out by Lefebvre (1967; 1972), Purcell (2013) and extended by Harvey into “the right to change ourselves by changing the city” (2008, p. 23). Their level of self-organisation varies from one space to another, and engagement in management is different for different categories of commoners. Building on Harvey (2011) and Davy (2014), who suggest that spatial UC are open access but regulated by land and urban policies, commoners include residents,3 citizens, and landowners, with diverse commoning practices, based on their relation to the space, property rights, and space typology.

Finally, crosscutting to the four internal dimensions, is that UC suffer from a lack of agreement and attention as a legal concept (Noterman, 2022; Marella, 2017; Łapniewska, 2017; Foster and Iaione, 2016). Commons did/do exist in law – statutory and customary laws – but “given the persistent dominance of the individual-based property paradigm, the legitimacy of the commons on legal grounds remains problematic” (Marella, 2017, p. 61). Yet, as commons are [re]emerging worldwide, law and governance are being challenged. For now, commons appear as nodes in an existing system dominated by the private-public dichotomy, exhibiting attributes that can potentially transform and heal the system, assuming obstacles such as scale, past failures, legal legitimacy, and individualistic behaviour/ideology of individualism are addressed. Hence, for open space UC to take on a significant institutional role in urban governance, there is a great deal that needs to happen.

3. Processes that Affect Urban Commons in Central and Eastern European Countries

Pemán and De Moor (2013) track centuries of common pool resources evolution to argue that institutions for collective action appeared earlier and with a higher degree of formalisation in Western Europe than in Eastern Europe. However, the complicated histories of commons in Eastern Europe inform how the common resources are understood – and how the commons are often employed as tools for social activism and practical criticism of the socio-spatial consequences of the post-socialist transition.4

In CEE countries, space appropriation for infrastructure, public open space, and housing, for instance, is strongly related to the socio-political processes that have taken place with the establishment of socialist governments and the abrupt societal transformation each country went through after 1990. During socialism/communism, land ownership was nationalised/socialised, and private property was abolished. This implied various physical configurations of space and modes of organising work in the different countries under collective dominion (Grabkowska, 2018). “In urban contexts, infrastructure remained auxiliary to industrialisation rather than a value in itself” (Tuvikene, Sgibnev, and Neugebauer, 2019, p. 10). Under the principle of equity, public space available and accessible to all was one of the targets of city planning, achieved based on per capita allocation standards (Haase et al., 2019). The government was responsible for producing, regulating, and managing public open space. This contributed to cultivating passivity among residents regarding their role in enhancing the urban quality of life (Theesfeld, 2019; Tuvikene, Sgibnev, and Neugebauer, 2019; Toto et al., 2021). Citizens were involved in the production and maintenance of urban space through ‘planned voluntary’ actions or imposed joint actions. Urban open space, publicly used, was meant for recreation, socialisation, political education, and often ideological indoctrination. It served, inter-alia, political systems as an artefact to expose its own greatness and power through parades, monuments, and palaces of culture and people. The fact that everybody could use such spaces but no one was personally responsible for their upkeep had, over time, created the idea that these spaces belonged to everyone and yet to no one. Once the political tides turned, this notion had grave consequences for the use of [public] open space.

The collapse of the socialist system in 1990 brought about transformative shifts in CEE societies, with narratives linked to privatisation, stabilisation, liberalisation, cost-effectiveness, decentralisation and democratisation, new nation-building projects, internationalisation, and in many cases, Europeanization (Tuvikene, Sgibnev, and Neugebauer, 2019; Čukić and Timotijević, 2020b; Tomašević et al., 2018; Stenning et al., 2010). In many CEE countries, cities were faced with uncontrollable demographic changes, urbanisation/suburbanisation, privatisation of space, austere infill development, land fragmentation, and gentrification. Urban open space, often unprotected by new policies and legislation, was either neglected and abandoned as a relic of the past or exploited by a myriad of small, commercial, private activities and later commodified by developers (Haase et al., 2019; Zupan and Büdenbender, 2019). Public institutions and planning systems were slow to adapt to these changes and protect open spaces in cities (Theesfeld, 2019). In a later phase, public institutions embarked on urban space redevelopment aimed at landscape beautification and further commodification through densification (Zupan et al., 2021).

The establishment of common-property systems over publicly used open space was not and still is not a widespread practice in the CEE countries. Furthermore, a living legacy in countries that have undergone a post-socialist transition (Müller, 2019) is the negative association of commons with the collective (Grabkowska, 2018) or as another nice-sounding way for the public to devour the private (ibid.). Theesfeld (2019) suggests that in CEE, there is resistance to and mistrust in common management due to the imposed collectivism of the socialist period. Therefore, even when property systems allow common ownership, there is still a huge cultural barrier to commoning.

Such resentment is not universal in CEE but varies per country and sector. Pockets of the left-over collectivist identity of shared spaces and common pool resources exist even in the highest citizen-mistrust contexts. Studies on public open spaces and commons show that there is no single post-socialist case, type, or pattern). The contexts have been different, and so are the socialist paths and post-socialist transformations (Haase et al., 2019; Čukić and Timotijević, 2020b; Tomašević et al., 2018; Staniszkis, 2012; Stenning et al., 2010). Yet, the socialist legacy has influenced the post-1990 transformations in all countries, making the latter subject to fast and major transformative shifts in the economy, government, social relations, and space, often imposed by international actors (Haase et al., 2019; Zupan and Büdenbender, 2019). In this context, urban practices appeared to stipulate that “something owned by the state is not necessarily used for the benefit of the general population and something that is a public good is not necessarily accessible to the public” (Tomašević et al., 2018, p. 67). These practices have incited activism and struggle over urban open space, and [re]appropriation has gained a new meaning. Thus, prior to 1990, the space ‘belonged’ to the people. Immediately after the change of regimes and in the absence of rules, people exploited urban open space in many CEE countries, mainly for small commercial activities. This transitory period led to the devaluation of such space and, coupled next with privatisation, it enabled its commodification under public programmes. The latter phenomenon gave rise to protests from people claiming urban open space as common space while often implying commoning for [re]appropriation of space. Though common governance of resources has its own challenges due to historical legacies, property systems, and the prevailing market paradigm, a UC narrative is now slowly and steadily emerging in CEE countries.

4. Case Study Research

For the study of the governance of open space UC in CEE, including its embeddedness in local governance, we adopted a case study method best suited for exploring complex, real-world phenomena, especially in under-searched contexts. As theory is yet rather undefined and UC research in CEE is still limited (very few identifiable cases), a qualitative, exploratory approach was expected to generate empirical findings to support further development of theory. Our study builds on earlier work related to open spaces UC, such as Toto et al. (2021); Čukić I. and Timotijević, J. (eds., 2020b) and Tomašević et al. (2018), and contributes to a joint effort of planning and geography scholars in the region on establishing a CEE Commons Workshop. In this paper, the case studies address the following items: i) conceptualisations of open space UC in each country, including related challenges and influences from post-socialist legacies and transformation processes; ii) the inclusion of UC in legislation (customary or statutory) and any historical law-related changes; iii) observations of the four aspects of sharing (uses and effect, property, management/governance, values and identity, and social production) and of the derivative complexities; and iv) potential prospects for open space UC in the CEE.

To select the cases, a preliminary list was prepared with cities and potential cases from participants of the researchers’ network, who have intimate knowledge of their cities and were engaged with the cases. The four cities/cases that were eventually selected for analysis, ensuring both variety (geographical and for UC processes) and comparability, are: Gdansk in Poland, Moscow in the Russian Federation, Podgorica in Montenegro, and Tirana in Albania. For each case, desk research, field visits with observations, and non-structured interviews were conducted. The following narratives build on the analysis of commoners and their roles, the spatiality of the resource, the uses with respective scales of effects and benefits, the boundaries of the UC in terms of property rights from Ostrom’s bundle (2003), and the governance rules and decision-making mechanisms. As for the external dynamics affecting each case, we considered the relevance of four post-socialist processes: Modernization and transformation of societies, embracing the neo-liberal ideology, free-market approach, sanctioning of private property and massive privatisation processes; Government shifts from centralisation to gradual decentralisation and the reappearance of management and control, with the potential development of authoritarian regimes under the guise of democracy; Social legacy of public as collective, a negative connotation due to which common spaces are either disregarded by the community or exploited by individuals who sense profit and direct utility; Urban space transformation, fuelled and supported by a varying combination of state and entrepreneurial spirits, resulting in densification, mega-projects, and endlessly growing suburbs.

Regarding limitations, the case study research does not allow for generalisation, and each city/case is specific, embedded within national contexts with varying narratives of post-socialist transition. Yet, because the research is taking place in a region with currently low recognition of commons in its theoretical/classical meaning, and with far from proliferating numbers of open space UC, the case study approach is not only the most feasible but also one that allows the in-depth study of nuances and uncommonness.

5. Case Studies

Poland: Podleśna Polana in Gdańsk

Although the concept of communal infrastructure in Poland was at the core of socialist urban development, it was discredited long before 1989. Abuses and injustices of the former political system corrupted even such useful institutions as allotment gardens and housing cooperatives. The once central idea of ‘the common’ fell away, and the neoliberal discourse introduced after 1989 only contributed to its bad press. Under the auspices of neoliberalism, institutions of the commons were either disregarded or forced into excessive privatisation and commercialisation. In 1990 the Act on Local Self-Government empowered local residents by defining a commune5 as a ‘self-governing community and the relevant territory’ but failed to equip them with adequate tools for participation in decision-making. New legislation regarding spatial management gave individual interests and private property precedence over the common good. Investors and developers became leading actors in the transformation of urban space, relegating local communities to background roles.

Consequently, ‘common’ equaled ‘no one’s.’ In the mid-2010s, around 50% of Poles showed insensitivity to the common good through, e.g., tolerance for the avoidance of taxpaying or free-riding on public transport (Czapiński and Panek 2015). Increasingly, however, harbingers of commoning practices have been observed across Poland, including various incarnations of commoning, from the reappropriation of municipal housing resources by formal and informal protest groups (Zielińska, 2015; Augustyn et al., 2017), to a renaissance of cooperatives (Matysek-Imielińska, 2020), and reclamation of the right to local decision-making via participatory budgeting (Pancewicz, 2013; Łapniewska, 2017). These pioneering UC experiments meet a lot of challenges and seldom succeed, but they persist nonetheless. Partly in response to these actions, urban space and infrastructure have been recognised as common goods in the media and research studies (Dymnicka, 2013; Grabkowska, 2018; Kubicki, 2020). This discourse builds primarily on a Western conception of commoning and only occasionally draws from the socialist tradition of collectiveness (Sowa, 2015).

Podleśna Polana in Gdańsk is an example of informal commoning of open green urban space. Even though UC are not provided for in Polish law and operate outside of an institutionalised framework, this does not deter collective action. Yet, weak management and governance structures have led to unstable and unsustainable commoning practices and results. Podleśna Polana consists of three hectares of undeveloped land in Wrzeszcz Górny, a centrally located district of Gdańsk, with tenement houses and villas from the early 20th century. A hilly meadow nestled between an urban forest and a rather affluent neighbourhood has functioned as an open green space for over 200 years. Historically, Podleśna Polana developed out of a recreational field in the vicinity that was arranged on private premises and made available for public use by a merchant based in then-Prussian Danzig in 1803 (Püttner, 2015). Having suffered significant damage during the Napoleonic wars, it was restored by the authorities as a much bigger public park. Numerous attractions, including cafes, promenades, sports fields, and an amphitheatre, accounted for its popularity until World War II. After 1945, the park was degraded into a communal forest and fell into disrepair due to political reasons (Rozmarynowska, 2011). Attempts to restore its former prominence, undertaken since the 1990s by local enthusiasts, were limited to small aesthetic interventions.

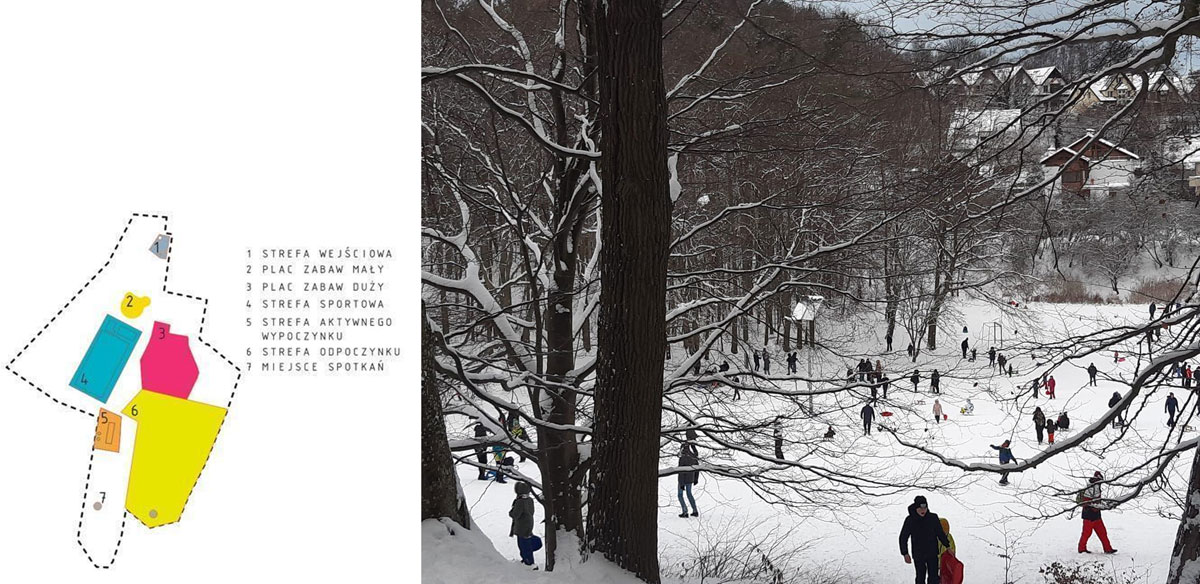

Despite being neglected during both the socialist and the transition period, Podleśna Polana remained frequented by the locals – people walking dogs, families with children, and youngsters playing football in the summer and sledding in the winter. In 2011, a group of residents (several district councillors among them) advocated for a rearrangement of the site. In opposition to the local authorities not prioritising green infrastructure, the initiative aimed at reorganising the open space to better serve the community. From the outset, the idea was to redesign the space through participatory planning and collective management. Several meetings with local residents nurtured a project developed by a local design studio. The concept addressed various user groups, maintained the site’s woodland character, and used natural materials for furniture. Other key elements included a symbolic entrance gate and a picnic area with a barbecue unit (Figure 2). By 2016, the grounds were drained, and the new paths were covered with permeable surfaces suitable for prams, strollers, and wheelchairs.

Figure 2

The spatial arrangement of Podleśna Polana (1 – entry zone, 2 – smaller playground, 3 – bigger playground, 4 – sports fields, 5 – active recreation zone, 6 – relaxation zone, 7 – meeting space) and the view from the south-east corner in January 2021.

Sources: Podleśna Polana… 2013, photograph by M. Zakrzewska-Duda.

The district council provided nearly one-fifth of the total cost of the renovation, which exceeded 120,000 EUR. The remaining amount was collected through two consecutive editions of the Gdansk Participatory Budgeting (GPB) and private sponsors. No direct funding was received from the city of Gdansk – the formal landowner, which, however, granted the permission for the rearrangement of the site and which is the organiser of GPB. After the planning and fundraising stages, the investment still relied on the bottom-up motivation of the commoners. In addition to the small group that initiated the project, participants were mobilised via a mailing list and social media. The site became one of the hotspots of local integration (Peisert, 2019). However, the later phases of the project lacked a clear strategy and specific rules regarding use and decision-making. Moreover, while the agency of the district council was crucial to the process, the latter hinged upon the leadership of two of its members. Their withdrawal marked a loss of momentum while the site’s popularity continued to grow, far exceeding the financial and organisational capacity of the commoners.

This case was never officially an UC.6 Although the site remained the property of the city of Gdańsk, its management and governance were taken over by the local community, attempting to better leverage its potential through collective design and management. The social production took place through participatory planning and budgeting. However, the successful transformation of Podleśna Polana was overshadowed by the dilapidation of the site, which fell victim to its own popularity. In addition, the withdrawn leadership and lack of a coherent set of use rules were decisive factors for failure. Finally, the practically non-existent cooperation with the Gdańsk administration contributed to the unsustainability of the project. Podleśna Polana thus represents an imperfect model of shared governance (Iaione, 2016). Although the citizens volunteered and were granted permission (by the City of Gdańsk and via the District Council) to govern the site, they were unable to enter into any binding “pacts of collaboration” with the local government (ibid, p. 422).

Though nowadays the area is a slightly rundown ‘common pasture,’ the social impact of the spatial transformation and the residents’ relational attachment to the space are unquestionable. Podleśna Polana still has the potential to become a successful UC Bottom-up, formalised community engagement in cooperation with the local government, with short-to-long-term planning actions, robust governance mechanisms, and rules of commoning, are critical to a successful restart.

Montenegro: The ‘100,000 Trees’ Initiative, Podgorica

Urban commoning in Montenegro has been shaped by three distinct but related notions: the Yugoslav experience of social ownership and self-management, the three decades of transition from socialism to neoliberalism, and citizen reactions to the neoliberal policies of privatisation and commodification (Harvey, 2003). In the experience of socialist self-management, the Yugoslavian social and economic experiment, which did not endure the failure of its political system, might still be considered one of the reasons that the citizens of former Yugoslavia turn away from contemporary commoning practices (e.g., shared ownership, common management, joint volunteer actions), as they are associated with the Yugoslavian model of socialism. However, it seems that in recent years this reluctance has been overpowered by the necessity to articulate a critique of neoliberal development. An interesting attempt at this articulation has been found in various forms of urban commons, which, although seldom using the theoretical framework of commons to describe their practices and struggles, are, in fact establishing new ways of creating, managing, and improving shared resources and spaces (Čukić & Timotijević, 2020a).

One recently established UC practice is the ‘100,000 Trees’ initiative (Figure 3), which started in the fall of 2018 in Podgorica. The initiative began as a response to Podgorica’s urban deforestation,7 the consequences of which are laid out in the ‘European capital greenness evaluation’ by Gärtner (2017). It originated with the local organisation ‘Kod.’ established in 2017 under the slogan ‘(Re)action to Reality.’8 For ‘Kod,’ launching the ‘100,000 Trees’ initiative was a way to confront a pressing urban issue through bottom-up tree planting. As the organisation had, at this point, already developed an online presence and established interaction with the community, the ‘100.000 Trees’ campaign managed to attract considerable interest. People were invited to engage in planting by donating money for seedlings or participating in planting actions, which were first organised once a week in the fall of 2018. Each action was followed by an online report detailing the number of trees planted and the amount of money collected and spent, with bank statements and receipts attached. The transparency of the process was considered vital for its success by the organisers.9 Bank statements showed that most individual donations amounted to between 5€ and 20€. Businesses usually donated more (up to 200€), while several tenant councils also collected money for the new trees, which they then planted with the technical support of the ‘100,000 Trees’ initiative. To make the most out of the crowdfunded resources, the initiative started cooperating with local and regional nursery gardens and seeking out smaller producers of seedlings for native species; many of them made special discounts or donated seedlings to support the effort.

Figure 3

The ‘100 Trees’ in Podgorica.

Source: Kod.

By the end of 2018, ‘Kod’ had successfully organised ten planting actions and published ten detailed reports. The initiative managed to raise 4,099€ and plant 1,228 trees, with the support of around 200 citizens who participated as donors, volunteers, or both. The role of virtual social networks can hardly be overstated: people learned about the initiative via social media and were able to communicate with the organisers through these channels, but also promote their own contribution to the campaign and invite others to join.10

The initiative faced three main challenges in its inception: a lack of detailed information about various urban infrastructures vital to the process of urban greening, the issue of care for the planted seedlings during the hot summer months, and insufficient local production of native tree species seedlings. These issues were addressed in ways that allowed for the various commoning aspects of the initiative – knowledge and resource sharing, local organising and production, to develop further. However, the local government did not get involved. The city institutions did not respond favourably to the initiative’s requests for help and proposals for collaboration, citing their own forthcoming plans for improving the urban greenery and declining to consider the approach put forward by this initiative. They did not forbid/halt the activities, but did not provide guidance on the placement of underground utility installations, which were at risk of being damaged during the planting process. The initiative answered this challenge by crowdsourcing the necessary information: participants offered suggestions for planting locations, along with their own knowledge of what installations might be under the surface. Every neighbourhood was able to gather this kind of information, thereby creating a new communal resource in the form of shared knowledge and enabling the initiative to overcome the obstacle posed by a lack of institutional support. The issue of care for the planted trees was addressed in a similar fashion: as the new trees were not being watered by the municipal services, volunteers of the initiative watered them during the summer of 2019 in 24 locations in Podgorica. This offered opportunities for involving more people and forging new neighbourhood connections while strengthening commitments to the resources created in this process. Finally, the insufficient production of seedlings was addressed by starting an experimental oak tree nursery garden within the framework of the initiative. A small plot of land was donated by one of the supporters, and the first batch of 10,000 acorns planted in this plot was collected through community actions. The organisers’ hope that the nursery garden would have a 70% success rate and produce new seedlings came true, and they plan to continue nursing these and then use them to reforest one of the hills in the wider Podgorica region. The snowball approach, through which the initiative continues accumulating knowledge and making use of it in the process, is one of the essential qualities of this commoning process.

This initiative has successfully introduced several innovative practices – social media mobilisation, crowdfunding, and crowdsourcing – proving that these can be effective mechanisms for commons organising. It has also managed to bring together different participants and stakeholders: not just individual users of public space and everyday city-makers (Foster and Iaione, 2016) but also neighbourhood associations and private businesses. Together, they created a network for the production and maintenance of new urban trees – indeed, a way of pursuing the common good, which is “collaborative and mutually supportive” (Iaione 2016, p. 433). However, a lack of support from the local government has kept this practice from being fully embedded within the local administration. By making such a decision, the City of Podgorica has not only thwarted the ‘100.000 Trees’ initiative, but also hurt its own chance to develop organisational and institutional innovations, which might have emerged from closer cooperation with this initiative.

One of the driving factors of the transition from a controlling or competitive state to a sharing, collaborative, and coordinating state (ibid, p. 446), apart from knowledge and technology, is the willingness to collaborate (Iaione, 2015) – which, in this case, is lacking. This hinders the development of more advanced (collaborative, cooperative, and polycentric) forms of urban governance in Podgorica and or the whole of Montenegro, for that matter. This, however, remains in line with the continued centralization of power and discouragement of meaningful citizen participation, which constitute the main governing strategies in Montenegro (Dragović, 2021), and which are currently being challenged through urban commons practices and initiatives such as ‘100,000 Trees’ (Čukić and Timotijević, 2020a).

Russia: Systemic Encroachment on Neighbourhood Courtyards, Moscow

Amongst the post-Soviet countries, Russia represents an emblematic case of both the tragedy of private property and the tragedy of the commons. Throughout its long imperial and socialist history, Russian citizens have seen their land collectively managed in the rural communes and urban housing associations, gradually appropriated during the first land privatisation reforms (1906–1911), forcefully collectivised by the socialist state in the 1930s, and finally reprivatized again in the 1990s, often ending up in the hands of the few. Russia’s history and value of the ‘private’ are as contested as its history and the meaning of the ‘common.’ Pre-Soviet Russia is known as a classic case of rural commons that relied on a customary culture of land management and the spiritual relations between the peasant society and their soil (Nafziger, 2016; Smirnova, 2019; Shanin, 1971). During the Soviet period, however, collective property relations were heavily reconstructed by the state (Humphrey and Verdery, 2020).

In the urban realm as well, Soviet public space was an expression of collectivism and solidarity, but under the guise of the central state – open urban places became centres for state-organised demonstrations and rallies. Spontaneous collective uses were prohibited and often moved to the private realm of people’s homes or the so-called kommunalki (communal apartments) (Zhelnina, 2013). Moreover, in the institutional discourse of urban planning, the idea of public space lacked the social component – “terms’ public space’ and ‘common area’ both of which designate spaces for use by the general public, yet the ‘use’ itself was not clearly defined” (Kalyukin et al., 2015, p. 680). With the post-socialist transition, private life became even more sought after, and decisions to enclose or appropriate a piece of shared open space were commonplace (Chernysheva and Sezneva, 2020). Hirt (2012, p. 4) frames this fracturing and subsequent fragmentation of the collective space under the umbrella of privatism – “a popular ideology driven by multiple intentions: sometimes to withdraw from the public realm, sometimes to appropriate parts of it, and sometimes to protest against it.” Despite widespread practices of privatism in Russia’s urban areas, there are still islands of collectively managed and owned spaces.

One illustrative example of open space UC in post-Soviet Russia is the case of residential courtyards – an inner territory of a typical residential block (a dvor), often adjacent to the multi-story apartment building (Figure 4), shared collectively by the tenants but also available to other citizens that pass by. These courtyards represent a rare institutional case of collective land management and even ownership since everything that is located on and even under a courtyard is registered as ‘common property.’ This includes the land plot on which the apartment building is located and the yard itself, with its borders defined on the basis of the state cadastral account. This implies that residents can dispose of collective property at their own discretion – from arranging the parking lot and flower beds to collectively delegating maintenance and hiring a managing company to upkeep the courtyard and its infrastructure. This also entails a set of collective responsibilities, wherein each resident pays a local tax for maintaining the territory. Though communal courtyards still carry a strong ideological legacy of the ‘Soviet collectives’ that all residents equally participated in creating (Humphrey, 2005), today, they are the expressions of contested relations between tenants managing their personal uses of the commons and the city officials encroaching on open land parcels in prime urban locations.

Figure 4

Residential courtyards UC.

Drawn and registered back in 2005, when the Housing Code of Russia came into force, all courtyard properties were automatically assigned to their residents, who received ownership rights to the property inside and on the premises of their apartment buildings. The plots’ boundaries were delineated when the residential blocks were built and recorded by the local Bureaus of Technical Inventories. Until now, even when residents knew about their collective ownership rights and borders, they lacked the knowledge or necessity to understand the value of the common property and obtain their property passports. The bureaucratic procedures for allocating and/or registering the boundaries of collective plots are notoriously complex, and many residents cannot afford the extra time or resources it takes to complete this process (Inizan and Volkova, in press). Moreover, after obtaining the documents, it may happen that the plots’ borders do not match archival records or overlap with planned or actual commercial use (Kozlov, 2020). In principle, it is impossible to reduce the original area of the plot without the documented consent of residents, therefore, these changes in the original boundaries of the courtyards’ plots are extra-legal (Narodnaya, 2020).

This was not a problem until the urban authorities initiated a new demarcation of courtyard territories, changing the borders of the large plots and opening them up for new construction. Moscow provides one such example. The attack on these spaces began with psychological pressure on residents, convincing them of the rising collective expenses required for the maintenance of the courtyards, whether residents used them or not. Most often, people were “deliberately misled into approving projects for the minimization of the amount of land assigned to their residential community” (Kommersant, 2014). In the Trekhprudny Lane neighbourhood of Moscow, residents later discovered the plans for new residential construction in their yard after they were convinced to reduce the common property to its minimum or to the immediate borders of the building (Kommersant, 2014). In the Presnensky rayon the residents discovered that their piece of common land was leased illegally to one of the biggest development corporations in Moscow, which had already built a new residential complex on the location of the common land and now refuses to sign documents for the restitution of the previous boundaries and its subsequent registration (Activatica, 2020). Though each case is unique – ranging from the cadastral land re-surveying (the so-called peremezhevaniye) to post-factum registration of new cadastral plans with illegal buildings erected on the collective land plots some time ago (often during the 1990s) – this practice remains commonplace. Areas with high potential for commercial use have seen systemic encroachment on their common property since the housing and communal services reform in the city of Moscow (2002–2007), whereby city authorities rezoned existing residential areas and changed the configurations and dimensions of land plots built before 1999. In some cases, authorities reduced the plots’ areas by 35–40% (KPRF, 2014; Svirin, 2020; Narodnaya, 2020).

Moscow has been an illuminating case of systemic attacks on common property, especially with the new Housing Renovation Program launched in 2017, which expands the power of local developers to densify Soviet-era urban blocks. Cutting off plots from the collective property for new construction has been justified in many cases by the fact that not all of the adjacent territories were registered in the cadastral system in a timely manner (Voronov and Zanina, 2020). Moreover, the recent Amendments to the City Planning Code, approved in December 2020, have institutionalised the practices of land encroachment by further simplifying the procedure for seizing land plots and expanding the rights of local authorities to improve “the territory within urban settlements in order to maximise their settlement” (Khovansky in Sudakova, 2018; see also Torocheshnikova, 2020). Here again, the concept of urban commons does not carry as much institutional value as the right to private property and, therefore, often becomes a victim of enclosures – a common issue for neoliberal urban development across both the East and the West. In Russia, urban commons once again have become a ‘national priority project’ of the Russian state, and a tool of political economic power since those receiving federal funds and subsidies for urban redevelopment in Moscow’s courtyards often use them to pay allegiance to the central state and help to maintain the ‘power vertical’ (Smirnova and Adrianova, 2022; Zupan et al., 2021).

Albania: The National Theatre Square of Tirana

Urban commoning is not a common discourse in Albania, and urban commons do not appear in legislation, institutional frameworks, local literature, or media. Additionally, in lay language, commoning bears a negative connotation due to the socialist legacy of the collective. The only law recognising commons is that on forests, under the terminology ‘forests managed by the community.’ Yet, urban commoning practices exist. Toto et al. (2021) describe four cases of public open space located in Tirana, with varying governing practices, user values, uses, and property rights. These four cases speak to a potential for urban commoning, revealing small-scale commons (with a limited number of commoners) as more successful for governance and larger-scale commons as richer for shared values.

Another vivid example of urban commoning, pertaining to city rights movements and an expression of community activism and struggle for urban open space, is the National Theatre Square of Tirana (Figure 5). The theatre and the respective public space are part of the central urban ensemble of Tirana, including seven11 government buildings surrounding the city’s central square, the main boulevard, and a cultural-educational-sport block on its southern end, all designed and built during the 1930s and 1940s. This urban ensemble carries a notable urban identity that has been very influential in the socio-political history of Tirana and Albania. The construction of the national theatre and square, initially known as the ‘Italian-Albanian Circle Skanderbeg’ (Plasari, 2018), ended in 1940. Over the decades, the theatre was an agora of cultural celebration and often also hosted political events. It was home to the theatre, cinema, art exhibitions, concerts, political meetings, and even the first ‘Institute of Albanian Studies,’ which made key contributions to Albanology (ibid.).12 Besides carrying a special meaning to generations of artists, it also embodied a space for recreation, cultural nourishment, and self-actualisation for the citizens of Tirana, turning into one of the symbols of the city’s common memory.

Figure 5

The National Theatre Square.

https://berati.tv/levizja-vetevendosje-tirane-sot-se-bashku-me-qytetaret-ne-proteste-per-teatrin/.

In 2018, the Government of Albania and the Municipality of Tirana decided to demolish the theatre to build a new one and transform the open space around it by transferring a significant part of public land to private developers in exchange for financial contributions toward the new project. The demolition (Figure 5) took place in May 2020 amidst the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions. Civil society, artists, and citizens nurtured an enduring and inclusive movement to oppose the government’s decision for more than 28 months, prior to and after the demolition and with international support. The Alliance for the Theatre (voluntarily established by activists and artists in 2018) galvanised even more citizen cooperation through an intensive information and awareness-raising campaign. They initiated a number of lawsuits, consisting of two cases at the constitutional court to dispute the special law passed by the Albanian parliament and the decision by the Municipality of Tirana to transfer the concerned public land to developers; of investigations by the Prosecutor’s Office of Tirana on the demolition; the Special Anti-Corruption and Organized Crime Structure of Albania on the decisions of the municipality; and the Ombudsman of Albania on the property transfer and violence against the protesters. Besides the legal violations, including those on the structure’s quality evaluation and the arbitrary revocation of theatre square’s cultural monument status,13 the demolition exposed the citizens of Tirana to three major risks. Firstly, it set the dangerous precedent of bypassing the current legislative hierarchy through the immediate approval of special laws for any public matter. Second, there was a lack of information and transparency regarding the development of public land and urban open space. The potential economic benefits for citizens were never discussed in public and likely not analysed for land value capture by the city, showcasing a typical example of urban open space enclosure by market forces. Lastly, it contributed to erasing common historical and city memory by obliterating a magnetic space that had generated and nourished common values for more than a century (Plasari, 2018).

The civic struggle (Figure 5) for the preservation of the National Theatre and Square was not framed institutionally and theoretically by the concept of UC. Yet, it represents a vivid case of the commons as an urban movement for urban space. The theatre commoners constitute a large community composed of citizens, artists, architects, urban experts, civil society organisations, and lawyers, among others. The movement was concentrated in Tirana, but several actions (protests and a petition signed by thousands of citizens) took place in other cities as well. This was a commoning action for the re-appropriation of space by citizens and key stakeholders with shared values, who engaged voluntarily and, in a bottom-up manner and institutionalised the movement into an alliance, with a program ranging from information and awareness-raising to active protests, lawsuits, and public debates in the media and in the open space. The commoners also received the support of the EU Commissioner for Culture, Mariya Gabriel, and Europa Nostra, a distinguished pan-European body committed to cultural heritage, who openly called upon the Albanian Government to withdraw the demolition plan. The commoners were ultimately unsuccessful in halting the demolition. Yet, in July 2021, the Constitutional Court repealed the above-mentioned special law and the decision of the municipality regarding the land transfer.

The movement faced mainly external challenges. The commoners mobilised citizen attention and involvement, but not to the level necessary to create a popular understanding of the risks of the government’s proposal. Society’s lack of concern was reversed, though not fully due partially to government claims of urban modernisation, and partially to public resistance towards activism and voluntarism. In addition, the movement happened during a long period of stalled political struggles, with the political opposition out of the parliament and the government holding all of the instruments to control the situation and public institutions. Furthermore, the Constitutional Court was suspended for a long time due to the ongoing justice system vetting process. The pandemic also added to the obstacles facing the commoning action. Finally, the local government did not welcome the theatre commoning initiative. On the contrary, it created barriers to it, favouring the enclosure of the space for development. The demolition took place in May 2020, in the middle of the night, to surprise the protesters and produce a fait accompli.

6. Discussion

The four cases of open space UC present their particular history and discuss their embeddedness within urban governance. The latter stems from the need to see UC as an enabler of change within the current state and market settings. Therefore, we observe the course of open space in cities’ developments and in urban planning, before and after the transition, vis-à-vis the governance implications of neoliberalism’s failures (Haase et al., 2019; Zupan and Büdenbender, 2019), which besides constituting a great case for commons, also reveals uncommonness. The observed uncommonness of open-space urban commons in CEE has multiple dimensions, as explained below.

The first dimension relates to rarity and scarceness. Public open space UC seems unusual in CEE cities. Regardless of the abundant literature, there are very few cases on the ground. This is due mostly to historical developments and the planning of urban open space in CEE during the socialist and post-socialist periods. These developments have given the conceptualisation of an urban commons a negative connotation. There are also cases where commoning for urban open space happens unrecognised or unnamed as such, for instance, in Tirana’s Theatre Square. Additionally, in three out of the four cases studied, there was no legal framework for open space UC. Even in the case of Moscow, where citizens managed to acquire legal rights to collective land ownership and full responsibility over its governance, urban commons became a centre for extra-legal enclosures from both market forces and the state. This might imply that the informal character of urban commons across CEE countries creates more security for urban commoning while legal recognition of use/ownership rights restricts it. In summary, open space UC could be considered a relatively new construct of governance, despite the collective’s long and contested history within the CEE countries. This history includes UC facing a number of obstacles, such as the lack of a legal conceptualisation and connection to urban governance; a prejudicial reputation of the ‘common,’ inherited from the communist period in some countries; and a recent prevalence of the logic of individual private property adopted by most CEE countries after the collapse of socialism.

The second dimension of uncommonness relates to exceptionality and remarkability. Thus, against all odds, and despite their ‘newness,’ open space UC have become more and more visible in CEE and represent robust and innovative responses to neoliberalism and socio-spatial injustices. Yet, in some cases, they become potential islands for the neoliberal appropriation of space (i.e., the cases in Moscow and Tirana). This duality makes them remarkable and exceptional relative to the features of national transitions and the common denominator of CEE countries – their socialist past. This context and these ideological shifts have defined or influenced the land ownership regimes, urbanisation, planning, value systems, urban public spaces, and the peoples’ rights in collectively sharing these spaces. As a result, commoning over urban open space has often taken shape as a vivid citizen movement for the reappropriation of the city. Although the different CEE countries have not equally absorbed the external factors, they have inherited a common path dependency, which has fuelled a myriad of behaviours and solutions for the co-governance of open space UC. In this sense, the second dimension could be refined as a dimension of the ‘hybrid state of urban commons in the CEE,’ defined significantly by the political-economic setting in which open space UC develop.

A third dimension of the uncommonness of open space UC in CEE countries is that of unevenness and asymmetry and, therefore, a diversity of approaches in sharing. Besides commonalities, there is significant diversity between the cases. For instance, the lack of formal recognition of UC by law has yielded success in the case of Podgorica, enabled strong commoning in Tirana and Gdansk (though without ensuring sustainability), and has enabled the private enclosure of the commons in the case of Moscow. The scale has also influenced the cases rather differently. The large group of (potential) commoners in Podgorica has nurtured further commoning, while in Tirana, it has intensified the sharing of values attached to space. The smaller scales of public open space in Gdansk and Moscow have had different results. In Gdansk, this affected the sustainability of the commoning, and in Moscow has inadvertently allowed space for extra-legal processes to override the commons. Furthermore, a lack of local government involvement was a common feature, but with different effects in each case. The local government created obstacles rather than advantages for commoning in Tirana; secured collective practices from market-based encroachments in Moscow; created space for success in Podgorica by not acting, and was silent in Gdansk, leading to a lost opportunity for boosting commoning. The diversity shown in these examples is rooted in UC’s various socio-cultural pathways and deserves more in-depth research to understand the factors contributing to the resilience of open space UC in the CEE socio-political realm (Perrings, 2006).

The uncommonness of open space UC informs the complexity that characterises its future. On the one hand, the shared socialist legacy and the societal trauma of state-imposed collectivism, together with the dual results of the appropriation intended by commoning, leads broadly to the alienation of UC. For instance, there is still no systemic public support for UC, and there is a lack of legal/institutional recognition within urban governance. On the other hand, the cases differ substantially in their outcomes. This illustrates that the thriving of open space UC is not conditioned by the presence of common legal property systems and local government support but is largely dependent on socio-cultural perspectives and political-economic contexts. Therefore, for city-scale open space UC, the presence of local government support and legislation might be an enabling factor that allows communities to preserve their control and agendas of space. Such support would benefit not solely the development of UC but also the evolution of urban governance towards co-governance through the development of organisational and institutional innovations useful to transparent and democratic participatory practices. This is important when seeking forms of co-governance that counteract the negative effects of the post-socialist transition.

7. Concluding Remarks

This paper is part of an effort to increase understanding of UC in CEE countries, particularly on urban open space. We have defined open space UC using a set of internal factors (shared property, use and effects, management, and identity and values) concerning the spectrum of commoners, the resource/s, and the formal and informal commoning practices. We take an alternative approach to categorising such space in legal ownership terms, arguing that more than a matter of property rights, this is a matter of citizens’ position towards open space as commoners who proactively engage in co-producing benefits from it while also preserving and governing it. The urban open space is government-owned, and in people’s perceptions and expectations, the government should take care of it. Citizens are distant from its management, limited mostly to paying taxes. This form of governance bears the failures of state-based collective action (Ostrom, 1990b), reinforced by the negative effects of the transition processes in the CEE. Alternatively, by taking up a position of commoners towards a public or common good, citizens engage as autonomous actors with power and strong odds of influencing decision-making and enabling urban co-governance.

The paper has observed the open space UC cases for uncommonness. Our findings add to the argument that there is no common post-socialist case or type of UC pattern (Haase et al., 2019). While the socialist legacy influenced post-revolution transformations in the CEE, including that of space, the latter did not develop equally in each country; commons’ ‘antipathy’ is not shared everywhere, and commoning approaches are unique to their contexts. In the frame of post-socialism and neoliberalism, open space UC in CEE has evolved as ‘the [re]appropriation of space,’ but with different scales, results, and motives and with different instruments and values attached to the various urban open spaces.

Furthermore, the embeddedness of open space UC in urban governance is unequal in form and outcome. We started with the assumption that UCs should not necessarily be influenced by government practices and frameworks and should maintain their independence and bottom-up energy. However, for UC to significantly influence current governance modes, such a relationship with government institutions, legal instruments, and governance mechanisms needs to be established, observed, and examined.

Finally, this paper explored four individual cases, each representing a different national-to-local context. This approach allowed for an in-depth review of the processes and aspects of the four internal dimensions of UC, but the findings pertaining to these cases cannot be generalised. More cases of open space UC should be added to the CEE repository to validate the unpacked features of uncommonness as observed in this paper and also enable the identification of design principles and attributes that could nurture sustainable models of urban co-governance in CEE cities.

Notes

[1] The solid and void are inherent concepts to architecture and urban design. The void is theorised by architects such as Peter Eisenman, Rem Koolhaas, etc. For a recent discussion see Stoppani, T., 2014. Relational Architecture: Dense Voids and Violent Laughter. Field: Urban Blind Spots, 6(1), pp. 97–111.

[3] Residents may also include shop owners or businesses that co-own or participate in co-managing the space.

[4] Despite generalised trends, Eastern Europe remains an emblematic case of the long history of collective land management in rural communes, based on the customs of peasant society and collectivism that predated the period of socialism in the early-to mid-twentieth century.

[6] In public discourse, it is referred to as a community project (Analiza zmian… 2014: 26) or an example of participatory planning (Gerwin, 2012).

[7] Among the causes for deforestation are increased numbers of forest fires (e.g., from 1486 in 2009 to 2679 in 2011, according to the municipal data) and effects of rapid urbanisation: the comparison between the general urban plans from 1990 and 2012 reveals 6.6 percentage points increase in the developed urban area across the same territory.

[8] The organisation’s work focuses on criticising government policies by publishing analyses of their effects and promoting solutions through campaigns and policy proposals. ‘Kod’ has gathered experts of various backgrounds, and have skillfully employed social media platforms (YouTube, Facebook, Instagram) to disseminate their findings and ideas.

[9] From an interview with Vuk Iković, biologist, member of ‘Kod’ and coordinator of the ‘100.000 Trees’ initiative.

[10] According to ‘Kod,’ content related to the initiative – calls to action, reports, promotional videos – garnered around 1,000,000 views across social media platforms.

[11] There were originally eight but one was demolished by the government in 1980 to build the National Museum.

[12] A summary of the National Theatre and Square history, from construction to demolition is found in https://www.archinternational.org/2020/08/11/teatri-kombetar-national-theater/.

[13] The status was given to the theatre [square] through a government decree in 2000 (no. 180) and it was taken away in 2017 through decree no. 325. This action is publicly contested and interpreted as a step towards enabling the legal environment for intensive urban development to take place along the historic boulevard and in the centre of Tirana.

Acknowledgement

As authors, we would like to show our appreciation to the three anonymous reviewers for their insightful suggestions and comments, helping us to critically review our arguments and improve the manuscript.

Funding Information

We would like to thank Co-PLAN, Institute for Habitat Development (Albania), the University of Gdansk (Poland), and the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology – FCT, grant no. 2021.07133.BD, for the financial support.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.