1. Introduction

Living labs (LLs) have increasingly been utilised to foster urban sustainability transitions in European cities through experimental methods, collective problem-solving, and innovative participatory approaches for citizen engagement (Evans & Karvonen 2014). They take on diverse forms, emerging from both grassroots movements and top-down initiatives, always emphasising contextual problem-solving (Aquilué et al. 2021; Scholl et al. 2022). Their application in academic research has surged in the last decade, partly due to substantial institutional funding from JPI Urban Europe. These specific urban living labs (ULLs) address urban sustainability challenges and transitions, promoting innovation through collaborative research inquiries in urban contexts (Voytenko et al. 2016). They are often deployed as part of the broader ‘just transitions’ movement towards low-carbon economies, which recognise that any ‘transition’ must also demand social and ecological justice in achieving this goal (Routledge et al. 2018).

Each laboratory has its own focus, but civic learning is embedded in all LL processes (Karvonen & van Heur 2014). This emphasis on knowledge co-production, flattening knowledge hierarchies and supporting collective actions towards socio-ecological transitions makes LLs well-suited to nurturing civic resilience across diverse contexts. LL methods require citizen co-researchers to embody certain capabilities (skills, knowledge, confidence) for action. However, this capacity does not always exist when working with challenging socio-economically marginalised urban communities.

The focus of this paper is on how agency and resilience are nurtured through co-designed learning programmes within diverse living lab settings. It is based on one long-term living lab in London: the R-Urban Poplar Eco-Civic Hub.

This hub was established in 2017 by public works and is part of a network of resilience hubs created by Atelier d’Architecture Autogérée in 2011 (Petrescu et al. 2022). These hubs are unique in that they were initiated by architects, governed by collaborative grassroots groups and incorporate academic researchers in specific LL projects (e.g. neighbourhood sharing, supporting neighbourhood climate action) (Belfield & Petrescu 2024). The R-Urban strategy aims to directly cultivate civic resilience among participants who steward the hub’s resources through the ongoing everyday reproduction of the space (Petrescu et al. 2016). Civic resilience reflects community ‘resourcefulness’ rather than their adaptability to systemic crises (MacKinnon & Derickson 2013); it highlights civic capacities in realising more just and equitable futures. Essentially, these are physical hubs that support diverse groups of citizens in realising collective agency for the transition to low-carbon and socio-ecologically just futures (Petcou & Petrescu 2018).

Most ULL research focuses on the extent to which sustainable transformations are achieved (e.g. environmental innovations, smart city initiatives, policy change) (Bulkeley et al. 2019). This is largely due to the LL framing, which focuses on tackling systemic challenges and the aim of replication in other spatial contexts, e.g. urban mobility and sustainable transport (Ebbesson 2023).

Research on ‘agency’ within ULLs highlights how the lab setting supports sustainable transitions through ‘distributed agency’ between institutional, business and citizen stakeholders (Anil Engez et al. 2021). According to Brons et al. (2022), it may support citizens in achieving a ‘reflexive agency’ towards sustainable futures by actively participating in a collective remaking of urban systems, e.g. local food systems. However, there is a lack of research into ‘how’ these lab processes cultivate and nurture agency through their research methods.

The present paper examines the by-product of LL processes: the formation of new agencies and resilience among citizen participants in ULL processes. Agency is explored via citizen participants’ personal reflective accounts during a one-year LL as part of the R-Urban Poplar hub. It seeks to better understand how agency materialises through the lab, with a particular emphasis on citizen participants without formal design training, institutional support or higher education training. The research questions addressed are:

How can living labs mobilise agency and resilience in citizens?

What methods enable this?

What role do design-researchers play in supporting the formation of resilient communities?

In this case, and other participatory research practices, it is essential to recognise that citizens are ‘experts’ in their context, bringing valuable but often overlooked situated knowledges and rich everyday experiences into the lab process. This research focuses on the impact of the lab on these diverse citizen perspectives, what was learnt, and what agency was achieved on a personal and collective level. In doing so, the paper gives insight for LL researchers into how to meaningfully support citizens in recognising existing capabilities for action and change.

The paper is structured as follows. First, it introduces existing literature on ULLs, urban commons as laboratory ‘hosts’ and how specific lab methods (co-designed civic pedagogies) support the production of agency. The paper then introduces the specific empirical case on which the study is based (Climate Companions 2022–23), a one-year lab within the R-Urban Poplar hub. Through citizen co-learner interviews, the paper elaborates on the forms of agency and capabilities achieved through this embedded research. This leads to a discussion on the methods that enabled agency in this context and the role of design-researchers in support of civic agency.

2. Background

2.1 ULL typologies and settings

ULLs establish collaborative environments for urban innovation to address various local and regional challenges. They aim for both specific urban improvements and broader systemic transformations (Aquilué et al. 2021; Scholl et al. 2022). Employing both bottom-up and top-down strategies, always emphasising participation, experimentation and collective problem-solving (Evans & Karvonen 2014; Karvonen & van Heur 2014). ULLs focus on multistakeholder collaboration, utilising expertise from civil society, government, academia and the private sector to collectively innovate in local urban contexts (Bulkeley et al. 2019: 319). In their study of European ULLs, Bulkeley et al. (2019) suggest three main models of governance:

‘strategic’ ULLs, which are typically funded and directed by the state

‘civic’ ULLs, which are led by institutional partners such as universities or research bodies

‘organic’ ULLs, initiated and managed by civic associations and non-profit groups.

The present study was embedded within what could be termed a ‘civic-organic’ ULL, as a range of non-profit organisations and citizen members steward the R-Urban hub. This group is supported by universities and a local housing association, which provides resources and facilitates research that aligns with the hub’s aims (Belfield & Petrescu 2024).

A key characteristic of ULLs is their geographically embedded research approach, which enables the contextual translation of knowledge across different settings (Karvonen & van Heur 2014). There is no fixed setting for ULLs: they can exist as comfortably in the digital sphere (e.g. collaborative digital innovations with geographic applicability) or be embedded within physical community-managed spaces (Anil Engez et al. 2021). Brons et al. (2022) argue that physical ULL settings, such as community gardens, are more productive when engaging diverse citizen audiences, as relations and networks manifest physically around the centralising location. It also supports academic researchers to collaborate with ‘hard to reach’ civic participants.

This paper builds on previous scholarship around ULLs that are embedded within urban commons as physical hubs for research projects (Feinberg et al. 2020; Seravalli et al. 2017). They are productive settings for integrating the ULL method, primarily owing to their porous governance mechanisms (De Angelis 2017) and their sustained focus on equitable resource sharing (Petrescu et al. 2022), which enables deep citizen participation in research. Urban commons come from the grassroots, bringing together citizens to mutually explore community-led stewardship and management of urban resources (Foster & Iaione 2019). As such, they closely align with ULL aims to support sustainable transitions in urban contexts through collaborative innovations and prototypes.

2.2 Co-design in ULLs

Although governance structures and settings may vary, ULL methods strongly emphasise knowledge co-production, attempting to flatten knowledge hierarchies from the outset. The use of horizontal decision-making emphasises the selection of relevant lab methods that enable meaningful research co-creation (Menny et al. 2018). One such lab method is co-design. Co-design can be understood as a systematic process for enabling multistakeholder groups to collaboratively pool knowledge and resources to collectively design ‘innovative solutions’ to local challenges (Manzini 2015; Mattelmäki & Sleeswijk Visser 2011). Co-design approaches are well-researched within ULLs, for example those fostering collaborative digital prototypes for sharing (Bassetti et al. 2019) or innovating neighbourhood mobility schemes (Ebbesson et al. 2024). These examples highlight the possibility of utilising co-design methods in LL settings, supporting broad stakeholder groups with diverse capabilities to collaborate in delivering local sustainable innovations.

Co-design processes are often facilitated by design-researchers, who are embedded within universities and bring design expertise and cultures to the project. Designers may act as ‘cultural intermediaries’ in ULLs, utilising skills as translators and mediators of viewpoints in the co-creative process (Teli et al. 2022). Manzini (2015) speaks about co-design processes bringing together ‘expert’ and ‘diffuse’ designers into collaborative dialogue around innovation challenges. In the present paper, the term ‘diffuse designers’ refers to citizens with no formal design training or qualification but it acknowledges their situated knowledge(s) and deep understanding of the neighbourhood as a form of ‘expertise’ in the process.

2.3 Civic learning and agency through ULLs

An outcome (or by-product) of ULL research can also be understood through the transformation of the actors participating: shifting viewpoints, developing understandings of complex urban dynamics, and nurturing capabilities. Under certain conditions, these skills and capabilities may support key stakeholders in taking wider civic actions as an extended outcome of the process (Belfield & Petrescu 2024). Lab participation can support civic resilience among ‘organic’ or grassroots groups that may mobilise agencies within the group in continued work towards equitable urban futures (Brons et al. 2022). In such cases, ULLs create rich civic learning environments, supporting stakeholders in acquiring the knowledge(s) and skills required for ongoing transitions. The labs themselves can be spaces in which ‘agency’ is developed.

To better situate this research, a common understanding to a broad social research concept is needed. In its most direct form, agency is often understood as our ‘ability to act’ (or choose not to) in spite of structural constraints within society (Giddens 1984). It has also been theorised through education as an ‘ability’ that can be partially nurtured through education and teaching (Priestley et al. 2015). In recognising that people can hold agency in some circumstances but not others, Biesta and Tedder (2007) make a case for ‘achieving agency’ over the ‘life course’, recognising that knowledge, confidence, skills and capabilities are integral to being able to act within the world. This research is concerned with civic pedagogies that nurture learners’ agentive capability. Civic pedagogies are situated and critical learning practices embedded within neighbourhoods that aim to foster civic action for sustainable urban transformations (Antaki, Belfield and Moore 2024).

The present research utilises ULL methodologies and frameworks to support the production of two trial civic pedagogies. These design-driven learning programmes brought together culturally diverse stakeholders, alongside civic associations, architects and academics, to collectively explore the potential for civic empowerment and agency in a neighbourhood setting. Citizen agency is integral to the cultivation of ‘civic resilience’ by supporting groups to ‘resist, adapt and transform their living environment’ (Antaki, Petrescu and Marin 2024).

3. Case study and methods

3.1 R-Urban Poplar as lab host

This paper focuses on a single project case, Climate Companions 2022–23 (CC). This was a two-year ULL embedded within the R-Urban Poplar Eco-Civic hub in East London. The research and fieldwork formed part of PhD research into the transformative role of radical civic learning in supporting sustainable transitions and civic resilience in a culturally diverse and socio-economically marginalised neighbourhood (Belfield 2025).

This case took a grounded approach, situating the ULL within an existing hub of neighbourhood action, R-Urban Poplar (Figure 1). This was started in 2017 by critical design practice public works, following the first London hub in Hackney Wick (aaa & public works 2015). The Poplar hub is part of a wider R-Urban network, which was founded by Atelier d’Architecture Autogérée in 2011. Five hubs have been established in suburban Paris and two in inner London, and a further site is being constructed in Romania. Collectively, these ‘R’ (resilience) hubs make up a strategy for supporting neighbourhood communities in sustainable transitions to lower-impact, more resourceful and just urban futures (Petrescu & Petcou 2020). Each hub is unique spatially and in its governance, but all have a focus on resource circularity and fostering agency within participants towards more resilient futures.

Figure 1

R-Urban Poplar Eco-Civic Hub 2021

Note: Located on a former carpark of the adjacent Teviot Housing Estate, the land is leased from Poplar HARCA, a housing association and social landlord.

Source: public works (with permission).

R-Urban hubs are synonymous with the growth of urban commons across Europe; they act as physical common pool resources, which are collectively shared by networks of locally based commoners (Akbil et al. 2021). In the case of Poplar, the hub is now governed by a number of non-profit associations, civic groups and citizen members, who collectively manage and sustain the hub operations (see Table 1). These involve weekly volunteering and skill-based learning programmes aimed at widening participation and supporting these learners in developing skills, knowledge and capabilities in everyday life.

Table 1

R-Urban Poplar Eco-Civic Hub

| CATEGORY | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| Hub size | 450 m2 |

| Hub governance | Informal polycentric governance model Five non-profit associations working with sustainability and/or social change missions 15+ resident food growers and citizen members |

| Hub users | 500+ annual participants/volunteers 50% within five-minute walking radius 50% across London, motivated by interest in workshop content |

| Hub infrastructures | Growing beds, kitchen, classroom, workshop, anaerobic digester, composting systems, compost toilet, mushroom farm, three studio/offices, material storage and harvesting |

| Hub learning programmes (2021–23) | Green skills training (weekly) Repair café workshops (bi-weekly) Community meals (monthly) |

3.2 Climate companions: methods and research

CC built on this existing hub framing, aiming to test new ‘co-designed civic pedagogies’ to develop deeper understandings of localised climate change at the neighbourhood scale and ultimately support learner agency for wider civic action through increased consciousness (Belfield 2025). This ULL research brought together a diverse network of existing civic associations and groups to collectively co-produce and innovate new civic learning programmes and support R-Urban to open up to new citizen members.

The research was conducted in 2022–23. The research was iterative, running two different trial pedagogies, the first in September 2022. Co-design workshops were the primary means of collaboration and co-inquiry, allowing civic actors to have something ‘at stake’ in the process (Binder & Brandt 2008). The first CC programme in 2022 was co-curated with existing R-Urban hub members, collectively organising a learning programme that responded to the theme of climate care. This was followed by a reflective period (analysing and evaluating the curriculum successes and failures) before co-designing a second learning programme from March to July 2023 (Figure 2). This second process was integral in diversifying participation by inviting new participants and partners to join the collaborative learning inquiry. The lab supported a new co-design group from the local neighbourhood, nine (of 10) participants were women, all aged between 30 and 60, and from diverse ethnic backgrounds (Bengali-British, British-Bengali, British-Somali, British-Vietnamese, European, British-Caribbean, North American). Most had previously participated as learners in CC22; none of the group had formal design training or considered themselves climate activists.

Figure 2

Climate Companions research design timeline showing iterative research cycles of design, action, reflection, co-design, action and reflection

This CC23 curriculum co-design process utilised co-mapping methods in order to reflect participant learning needs and desires and to collectively map alliances and neighbourhood groups to partner with (Belfield 2025). The design workshops took place via a ‘Discursive Dinner’ format (Aßmann et al. 2017), where food and its collective preparation and eating were used to structure design workshop activities. This supported the formation of trust within the group and enabled a shared ‘community of practice’ (Wenger 1999), creating a core citizen participant group with a reciprocal desire to co-learn together.

During both CC programmes, the research reached a public audience of over 250 co-learners, involving a further 13 civic and non-profit associations from the local neighbourhood in the delivery of the programme. In total, 32 workshops were held across two ‘festivals of learning’ at R-Urban Poplar. The learning programmes engaged diverse public audiences through three main modes:

Learning by doing (Figure 3):

hands-on, skills-based learning focusing on sharing knowledge around low-impact living, e.g. ecological construction methods, seed harvesting, and herb propagation techniques.

Learning from place (Figure 4):

neighbourhood explorations by walking and sensing physical environments, often linked to investigatory themes, e.g. wild food foraging walks and multi-species habitat identification walks.

Learning through togetherness (Figure 5):

performative and creative workshops which centred community cohesion, well-being and building relations between groups, e.g. community feasts and collective cooking workshops.

Figure 3

Learning by doing: participants working together in an eco-construction workshop to build formwork for the hempcrete casting

Source: Author.

Figure 4

Learning from place: a neighbourhood foraging walk led by a wild food expert explained how and when to harvest a variety of edible street foods

Source: Nana Maolini and public works.

Figure 5

Learning through togetherness: ‘a discursive dinner feast’ in which the group reflected on the two-week curriculum and the knowledge learnt and built companionships

Source: Author.

The impact of the lab process was evaluated by focusing on the accounts of lab participants and triangulating these findings with auto-ethnographic observations from the author. Following the completion of the learning programmes, qualitative post-evaluation interviews were conducted with five citizen participants, and a further focus group was held with five R-Urban members.

These interviews investigated learner and facilitator perspectives on lab participation: what was learnt, which methods were effective and what impact the pedagogies and process had on participants individually or collectively. Interview data was analysed as part of a grounded theory approach, where findings emerge in the ‘back and forth’ between data gathering and iterative analysis and are shaped through the researchers’ and participants’ subjectivities (Thornberg & Charmaz 2014).

In parallel, the author documented both pedagogies through journaling and the production of a design portfolio, which analysed photos, video excerpts, learning environments through drawing, and ethnographic observations via daily diary. This supported the triangulation of key concepts emerging from the process and developed initial codebooks for transcript analysis in NVivo. This ‘back and forth’ between design portfolio, transcript coding and further informal conversations and reflections with R-Urban members ultimately shaped the emergence of the research findings.

4. Research findings

4.1 Altering habits of the everyday

When discussing the impact of the CC programmes with lab participants, all responses highlighted the knowledge and skills gained and how they continued to shape everyday experiences. Multiple reflections centred on the space of the home and within work lives as spaces to apply newly acquired knowledge, for example by shifting mindsets:

I’ve learnt so much, honestly. I can’t even begin to say. My mindset has completely changed. Even though I knew how to do it was in me, but I wasn’t quite active enough. I think I’m consciously doing a lot of things. Recycling, thinking about food waste, limiting food waste. Thinking about the way I grow things. Thinking about pesticides. Thinking about the composting.

In this extract, the learner emphasises ‘doing’ and what could be considered small everyday actions in response to altered mindsets. It highlights a consciousness mobilised to think critically about their daily routines before demonstrating how changes in lifestyle were encouraged. In certain accounts, this expands beyond the self, moving towards wider advocacy with others, e.g. family networks or colleagues:

When people come to this kind of programmes, everyone takes away something, but for myself, I’ve taken away so much. For me, the biggest thing is sustainability […] I’m sure a lot of people are doing different things at homes because they’re trying different things, and even changing my lifestyle around where I’m walking a lot more. Even limiting using my car. Changing the way my children and my family think about things. For me, I’m not just doing it, I’m doing it at work. I’m doing it with family. I’m doing it with my neighbours.

This scaling beyond the individual shows a certain degree of consciousness and belief in lower-impact living and a commitment to encourage others within their social sphere. This reflection is emphasised by R-Urban members, who described how the learning process had a ‘legacy effect’ that changed their experience of the everyday in unexpected ways:

It makes people feel good. Feel good and feel that they have the power, or feel empowered maybe to do stuff, to take action and do things to take home with them, I think. That’s often a thing. People are like, ‘Oh, I’m going to go try that at home.’

This demonstrates a pathway for learners by first reflecting on personal lifestyles before adopting and advocating for alternatives within social networks. Several participants discussed how taking action individually was easiest because it is the only sphere one has direct ‘control over’:

I think it’s actually probably quite effective with some of the skills or the knowledge learned here, because it makes it very tangible. It’s those little elements where I feel like those are at least, the things we have control over.

The CC programmes seemed effective in raising consciousness within learners for sustainability in broad terms through the adoption and altering of everyday habits and life. The ‘legacy effect’ of the pedagogies is most keenly felt in learners’ ability to reshape their personal habits and attitudes and in some cases advocate for these viewpoints with others in closer personal networks.

4.2 The empowering nature of ‘hosting’

The ULL created opportunities for learners to become teachers or the term used at R-Urban ‘hosts’ of workshops. This was particularly evidenced in CC23, with four citizen co-design participants going on to host workshops. These workshops focused on sharing knowledge(s) and skills developed through self-directed learning and personal interests (e.g. horticulture, amateur ecology). For one participant, this was their first time acting as a host, something they acknowledged they ‘never had the courage to do [themselves]’. With encouraging support from R-Urban members and a design-researcher this participant developed a workshop that shared family recipes and food cultures from Bangladesh under a framing of local food justice. In their words, ‘I felt like I was doing something for my mum. I was living my nan’s memories and it felt really empowering.’

Equally, R-Urban members viewed civic learning as integral in developing ‘confidence’ to share knowledge and to act with others (families, friends, colleagues), which helped to scale the impact of the lab to broader networks:

I feel like it’s giving confidence maybe for some people that come. It’s not that they learn everything. Not everything is new to them, maybe something that they already had a lot of knowledge on or they carry that in themselves but maybe they felt a bit alone. Now I feel like they feel more robust to embody that maybe with their friends, family, or whatever. They feel maybe a bit more confident, feel that they can pass on some of the skills.

This highlights the importance of ‘confidence’ in being able to teach others in peer settings. In interviews, R-Urban members described their personal confidence being partially down to being both ‘sociable’ and ‘stubborn’ but always derived in a deep understanding of the topic being taught:

I think that’s what gives you the confidence, without knowing a bit, you can’t really do the workshops. I think my aim with the workshops is for those that come to the workshops to be able to do their own workshops because it means that they’ve learned and have that confidence to go and do their own.

This reflects one of the lab’s primary aims, nurturing participants’ abilities to ‘have the confidence’ to teach others, expand the potential of civic learning to new audiences, and to advocate for climate action.

4.3 Expanding relational networks and alliances

The CC programmes had a direct impact on the R-Urban hub (as a place and its members) through expanded audiences, building new networks and forming alliances with other local organisations. R-Urban members highlighted the curriculum co-design and outreach being important for the hub – ‘[We] drew in a different crowd, I felt like, our reach was further’ – before going on to reflect on how the entirety of the learning programme felt more coherent and connected with local interests and groups.

The pedagogies had a catalysing effect on the hub; through their co-production, they expanded audience participation, building local networks through the programmatic focus on the neighbourhood of Poplar. In 2021, R-Urban Poplar worked in partnership with five local associations and organisations; by 2023, this had expanded to 13. Two of these organisations, who were connected through the pedagogies, now have permanent offices at R-Urban, making use of available resources in exchange for continued civic learning programmes.

Ten of the 13 groups continue to work collectively as allies through new partnerships and other justice networks, such as the Tower Hamlets Food Partnership. Lab participation became the catalyst for forming relations by visiting other community spaces or by inviting groups to host workshops during the curriculum. CC became an opportunity to be generous with institutional resources and funding, paying local groups for their time and, in exchange, expanding audiences. Importantly, the open-ended nature of R-Urban enabled these new relations to be sustained after the pedagogies through new programmes and events or by sharing resources. This is significant, as the informal network needs ongoing reproduction and maintenance, which is now facilitated beyond the lab by R-Urban members.

4.4 Catalysing new roles and initiatives within the hub

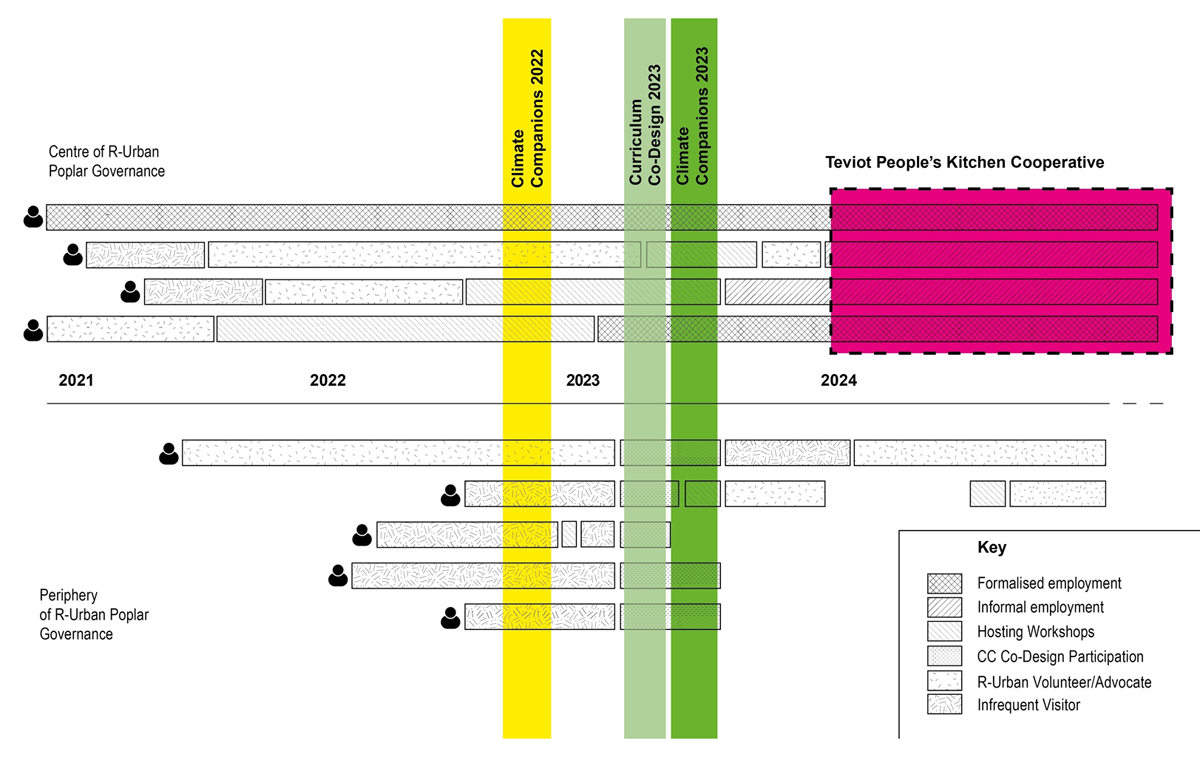

The CC programme supported the expansion of new individual roles and initiatives within R-Urban. The project co-design group has become centrally involved in the organisation and ongoing public programming at R-Urban. Figure 6 plots the co-design groups’ changing roles through the duration of the research process and beyond. It highlights individual journeys from ‘infrequent visitor’ to ‘formal employment’ and the different roles taken on.

Figure 6

Evolving roles within R-Urban, moving from the periphery to the centre of hub decision-making

Note: Some participants became formalised through employment

Six of the co-design groups remain closely involved: two through formal employment, three through informal paid work as workshop or programme facilitators, and one as a regular garden volunteer. The lab co-design process also catalysed the formation of a new cooperative, Teviot People’s Kitchen (TPK), which was initiated by four members of the CC co-design group. TPK tackles local food justice by organising workshops, fairs, events and training at R-Urban (Figure 7). The research process played a crucial role in fostering trusting relationships within this group, enabling them to act and gain the confidence necessary for this new collaboration. This group has now expanded to six members; the group has thus far run 13 workshops and two fairs, and conducted over 60 hours of employment/skills training.

Figure 7

Teviot People’s Kitchen Launch Event in 2024

Source: Author.

Since the CC programmes, the R-Urban hub has continued to expand its reach to new participants, reaching over 800 people through weekly climate learning programmes in 2024. The hub becomes a concentrating location for climate and neighbourhood action. It provides a free space and resources in which partners, collaborators and informal members can put their collective energy into action, a space in which they can nurture their civic agency. One example is R-Urban’s continued work within the neighbourhood on the ‘Poplar Green Futures’ project, leading a civic engagement process and supporting a co-design process on social housing estates to reimagine more climate-resilient green spaces.

5. Discussion

5.1 Civic pedagogies nurture our capability to act

The lab enabled participants to learn and demonstrate a newfound consciousness of low-impact and sustainable lifestyles by incorporating new habits into everyday rituals. However, learners ‘advocating’ with others for low-impact and sustainable choices reflects the capability to act beyond constraining societal structures and the self. CC gave learners the knowledge, skills and confidence to reclaim some personal (limited) control over the climate emergency.1 These ‘small acts’ contribute to a wider political consciousness that has greater transformative potential (beyond the lab), developing advocates and activists for climate justice struggles. In this case, starting with the immediate neighbourhood context and developing the knowledge ‘to act’ within the everyday was a first step towards more significant agencies and resilience.

These new habits, skills and knowledge contribute towards individual ‘learning in the life course’ (Biesta & Tedder 2007). The pedagogies helped to raise consciousness, allowing participants to reclaim control over limited aspects of their personal lives. These small actions and individual responses can be understood as ‘achievement towards agency’, a gateway towards wider activism and neighbourhood action, the first step towards political bodies acting together rather than alone.

By learning in collective settings, barriers to access to knowledge were overcome, and learning how to participate within a ‘community of practice’ directly supports the labs impact. The CC programme nurtured a partially forgotten or overlooked resilience within co-learners, and it supported them in re-engaging sustainable transitions in domestic, work and civic settings. It supported citizens in nurturing their agentive capability, by learning to work together and collectively creating radically inclusive learning spaces. Bohm et al. (2018) describe this form of civic education as ‘learning to act’, altering subjectivities in everyday life with transformative future potential for action. This form of hands-on, civic learning in LLs can contribute towards systemic visioning projects by taking initial steps towards action.

5.2 Achieving agency through peer-teaching

For several reasons, becoming a workshop ‘host’ or ‘teacher’ was significant during the lab process. First, it demonstrates a degree of ‘confidence’ within the co-learner to put themselves and their knowledge ‘out there’ to strangers or unfamiliar audiences. Confidence was identified as an integral part of becoming a host, without which the possibility of being a host or teacher was more challenging. Second, it demonstrates a deep understanding of the topic, in some cases developed through tacit knowing, and through situated experiences. It supported ‘hosts’ in valorising their knowledge by giving it a platform and the support of the lab’s resources in bringing it to a public audience. Third, it indicates the critical consciousness of the subject and capability to act otherwise despite the constraints of societal structures.

The act of teaching others demonstrates the ‘achievement of agency’ (Biesta & Tedder 2007), the capability to act otherwise in support of an ecological transition in which they can play a small part. It reflects the empowering nature of learning and teaching, recognising its integral role in achieving personal and civic agency. Becoming a R-Urban ‘host’ indicates a significant transition for some learners, an empowering journey demonstrating their achievement and resilience.

5.3 Civic agency transforms the hub (and the neighbourhood)

The R-Urban setting for the lab was integral to the cultivation of civic agency in Poplar. Without designated and designed hubs of climate and civic resilience, the CC programme would have had a limited impact on an urban level. Civic pedagogies need a centralising and geographic locus for the activity and learning. Communities need spaces to physically assemble to form relations, ties and networks. R-Urban Poplar enabled this; as a space that was inclusive and porous to newcomers, the hub was central in forming strong social bonds that have the potential to be transformational on an urban scale.

Civic agency is defined as a ‘collective’ and ‘relational’ practice in which groups assemble to take action together (Koskela & Paloniemi 2023; Sara & Jones 2017). The hub acts as a condenser of relations and networks, a generous space that can incorporate multiple stakeholders from a range of institutions and diverse backgrounds simultaneously. This is most directly evidenced by the formation of the Teviot People’s Kitchen initiative. In this instance, the R-Urban hub supported this new group in taking on new roles and employment as an unplanned outcome of the living lab.

Having spaces within cities where groups are free to act, organise and mobilise collective agencies towards just transitions is essential in scaling their impact. Without this, the lab’s focus naturally shifts towards personal development rather than collective action. In this case, group agencies were mobilised towards transformative action directly within the host organisation, itself an urban common. This indicates the role of ‘host spaces’ and their polycentric governance frameworks in further supporting co-learners beyond the lab framework. They are spaces in which collective actions can be taken and citizen participants can continue to organise, mobilise and act beyond the lab process.

The expansion of the relational network of stakeholders who contribute to the R-Urban hub (post-lab) is a testament to the civic agency of the collective group that steers it. New self-organised initiatives (Teviot People’s Kitchen), new hub civic associations and continued civic learning programmes represent the expanded collective’s capability that governs the hub resources. In this case, the lab catalysed the transformation of the existing hub to reach new audiences and transform the day-to-day of R-Urban by expanding the pool of organisations and citizens who manage it.

R-Urban’s growing influence in the neighbourhood, through the ‘Poplar Green Futures’ projects, showcases the transformative potential of the hub’s collective agency. This influence is also reflected in the strength of local solidarity networks focused on climate and food justice. These networks function at a metropolitan level, extending beyond Poplar, and create opportunities for broader collective action concerning climate issues, such as advocating to the local government for food justice and support for vulnerable community organisations. Civic learning first mobilises communities around climate action within the neighbourhood; this agency is enacted through the reproduction of R-Urban, which, in turn, catalyses the expansion of the R-Urban agenda to a wider neighbourhood. Ultimately, the R-Urban Poplar hub enables learners to move beyond individual agency and towards civic concerns. It has become a collective space for citizens enacting a more just and resilient neighbourhood, a space to take action and influence future visions of the neighbourhood.

5.4 Mediation and co-design

To a large extent, the agency ‘achieved’ through the lab is rooted in the co-design process. Mediation involves bringing together diverse groups and interests, building alliances and overcoming hierarchies (power, knowledge, resources) to facilitate a process where meaningful collaboration can take place. In this case, co-design and the role of design-researcher were integral.

For the author, acting as design-researcher involved initiating and facilitating the collaborative inquiry. Setting up and designing a workshop process that enables more diverse citizen participation and learning programmes that reflect these groups’ desires. In this process, the author started with the lab’s initiation, mediating and facilitating the co-design process towards the goal of trialling civic pedagogies. This then shifted through the process, moving from designer to educator and, ultimately, a co-learner during the process. It involved a movement from the very centre towards the edge of decision-making power, but always with a fundamental facilitating role. This is a reminder of Petrescu’s text ‘Losing control, keeping desire’ (Blundell Jones et al. 2005), recognising that in any participatory process those who initiate must be confident in letting go, guiding the process and potentially stepping back and handing over to others. The role of the design-researcher was to ‘make things happen’ (Manzini 2014), to enable others by relinquishing control, nurturing existing capabilities within the group, as part of a shared community of practice.

Co-design practitioners/researchers remained integral to the development of CC programme, utilising ‘designerly intent’ (to set the objective and aim) and ‘expert’ capabilities (design literacy, cultures and agency) to mobilise resources for the pedagogies (Manzini 2015). The role of initiation is fundamental and recognises the agentive capacity of design as a catalyst for social innovations (Antaki & Petrescu 2023). Ultimately, the role of co-design initiator is a delicate balance to tread: setting a project direction and course, while simultaneously taking the project in unexpected and unplanned trajectories as determined by the participants voices.

Through the co-production of the CC programmes, co-learners’ roles within the process are adapted, taking on new responsibilities and actions (promoters, facilitators, workshop hosts, etc.). The co-design group moved from the periphery to the centre of R-Urban Poplar’s organisation and activities. The process concentrated participant involvement within R-Urban, catalysing new relations, forming a community of practice and supporting many of this group to take on new responsibilities. The co-design process enabled participants to have ‘something at stake’ (Binder & Brandt 2008), responding to personal learning needs and desires. It also raised ‘the stakes’ in creating collective opportunities to take on new roles as ‘hosts’ and share their knowledge, skills and experience. This has extended beyond the lab into the continued operation and governance of the R-Urban site, supporting the wider civic action. In this case, the co-design process created opportunities to diversify the voices who steward the hub’s resources; it is a demonstration of a collective, civic agency and resilience achieved in the process.

6. Conclusions

This research has shown the potential for collective civic pedagogies in nurturing agency and civic resilience within lab participants. This agency is significant in supporting citizen-led grassroots actors in ‘learning to act’ collectively and in support of neighbourhood transformations. The labs embedded within physical community settings, such as urban commons, are integral to the process of creating a rich learning environment with the capacity to support citizens in wider neighbourhood actions. Co-design was equally important in reaching diverse audiences and supporting open-ended processes in which citizens were at least equal collaborators and the primary beneficiaries of the lab.

LL research tends to focus on the success of final outcomes, such as ‘designed innovations’ towards sustainable transitions through collaborative processes. However, the citizen participants’ transformations within the labs themselves is also a significant feature. Although this is often a secondary output or by-product of lab framing, design-researchers should consider foregrounding the latent agency within such participatory research approaches. Living labs have the capacity to support civic agency within existing communities of action, providing them with the tools, knowledge and resources to nurture emerging resilient communities.

Notes

Acknowledgements

The author thanks the Economic Social Research Council and the White Rose Doctoral Training Pathway for generously funding this research and the School of Architecture and Landscape at the University of Sheffield for providing such a welcoming home for it. Sincere thanks to all those who participated during the Climate Companions programme, as learners, hosts and wonderful new friends, who made the learning experience so rewarding. Thanks to all members of the R-Urban Poplar project and public works, whom without the research would not be possible. Lastly, thanks to my doctoral supervisor Doina Petrescu, for the years of guidance, support and mentorship.

Competing interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

The guest editor (Doina Petrescu) was recused from all decisions about this manuscript to avoid any potential competing interest from arising.

Data accessibility

All data supporting this study are openly available from University of Sheffield Data Repository (ORDA) at https://doi.org/10.15131/shef.data.30112993

Ethical approval

Data obtained from participants in this research were through informed consent and approved by the University of Sheffield’s ethics committee.