1. Introduction

As flooding events become increasingly present in urban areas, Brussels Capital Region (referred to as Brussels) struggled to find innovative means to fight a deep-rooted problem: how to tackle urban flooding while increasing the well-being of communities living in flood-prone areas. This is the type of complex question fit to be explored by urban living labs (ULLs). Brusseau’s (Brussels Sensitive to Water) living labs (LLs) addressed the challenge by fostering residents’ expertise as a key source of knowledge. Researchers from different disciplines worked together with activists, practitioners and public authorities to apply this approach. The roles of researchers changed from one LL to the next, sometimes even within the same event; the researchers often struggled to keep up to this new environment or to find their own way to produce knowledge. As participants in this experience, the authors of this paper wondered whether, how and why researchers change and adapt their practice to the LL.

This type of reflection has entered the growing literature about ULLs. As an emerging action-research practice, a ULL involves citizens, civil society organisations, researchers and public authorities in implementing place-based local solutions to respond to growing urban challenges (Bulkeley et al. 2016). As spaces for experimentation, LLs are known for creating the conditions for transdisciplinary action research where researchers develop knowledge, with both practical and reflective dimensions together with other actors, including those from different fields (Reason & Bradbury 2008). At the core of this process is knowledge co-production, ‘a collaborative and dynamic knowledge-generation process that more fully grounds scientific understanding in a relevant social, cultural, and political context’ (Schuttenberg & Guth 2015: 1).

In this new research environment, research indicates that the role of researchers (affiliated to academic institutions) broadens from observers of a phenomenon to engaged participants who trigger and sustain change such as facilitators, issue advocates or reflective scientists (Herr & Anderson 2015; Kruijf et al. 2022). Researchers change roles and methods during their actions in LLs to, among other objectives, facilitate better understanding of the conditions in which knowledge co-production occurs; integrate the perspectives of the most vulnerable actors; create space for learning and empowerment; and translate complex ‘technical’ products, such as hydrological and climate models, into usable and ‘easy-to-understand’ language (Brandsen et al. 2018; Rickards et al. 2014). In this context, a more structural understanding is needed on the roles of researchers and their impact on knowledge co-production to support researchers in navigating these new and turbulent waters. The aim of this paper is to address this identified need. It investigates the question: what roles do researchers assume during LLs and what are the drivers behind these roles?

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 shows the state of the art on the questions. Section 3 explains the process of data collection and analysis. Section 4 follows the development of the conceptual framework of the research, inspired by Schuttenberg and Guth (2015) and Kruijf et al. (2022), to identify knowledge co-production conditions as drivers for a typology of roles taken by researchers within LLs. Section 5 presents the application of the framework to in-depth research involving two Brusseau LLs, linking knowledge co-production conditions to the roles taken by researchers. Sections 6 and 7 offer a list of elements to consider as recurrent conditions that influence researchers’ roles as baseline for strengthening researcher’s capacity in engaging in LLs.

2. Roles of researchers in living labs

LLs have emerged across Europe as place-based platforms for co-creating innovative, context-sensitive solutions to urban and societal challenges. These environments foster collaboration between diverse stakeholders – citizens, public authorities, researchers or private actors – within physical or virtual settings to develop, experiment and validate technologies, services, and policies in real-life scenarios (Hossain et al. 2019; Leminen et al. 2012; Westerlund & Leminen 2011). Rooted in the principles of open innovation, LLs are conceived as networks or spaces, characterised by openness and user engagement, fostering innovation through mutual learning and iterative development (Nyström et al. 2014). Common across this perspective are various key features: user involvement, real-life environment, service co-creation, multistakeholder participation and the use of diverse tools and methods (Greve et al. 2020). Particularly within urban research, LLs have been recognised for their potential to bridge diverse knowledge systems and foster co-creation across sectors. Franz (2015) highlights their relevance in addressing socially driven research questions, noting that LLs can serve as inclusive spaces where residents, policymakers and researchers co-develop solutions tailored to local needs.

Existing research on LLs has primarily concentrated on analysing their foundational paradigms, with particular emphasis on open and user-driven innovation (Edwards-Schachter et al. 2012; Hossain et al. 2019), as well as on identifying their defining characteristics (Ballon & Schuurman 2015; Greve et al. 2020). Other authors have specifically investigated the different roles that actors play in LLs. Among them, Westerlund and Leminen (2011) have proposed a typology of four actor categories:

enablers, who provide resources and institutional legitimacy (e.g. public institutions, financiers and NGOs) (Hossain et al. 2019; Leminen et al. 2012);

providers, such as universities and consultancies, who supply knowledge and support (Hossain et al. 2019; Leminen et al. 2016);

users (e.g. citizens), who actively participate in co-design and evaluation (Hossain et al. 2019); and

utilisers, including businesses and public authorities, who apply the outcomes of innovation (Hossain et al. 2019; Leminen et al. 2012).

Nyström et al. (2014: 485) have further conceptualised actors’ roles in LLs by considering them as dynamics, often negotiated and reconfigured throughout the LL life cycle.

Despite this growing scholarly interest on the role of actors enabling innovation in LLs, a nuanced and systematic understanding of the specific role of intermediary actors, like researchers, remains underdeveloped in the academic literature on LLs (Hossain et al. 2019; Nyström et al. 2014). While researchers are often categorised as providers (Hossain et al. 2019), practical experience demonstrates that their contributions often go beyond technical support or knowledge transfer.

Researchers can adopt multiple and shifting roles depending on the context, the phase of the project and the stakeholder constellation. The hybrid and multifaceted involvement includes designing research protocols, managing data, and supporting co-creation or capacity-building. Their actions can be influenced by different drivers and motivations, including the broader governance and power distribution structures within the LLs (Greve et al. 2020; Hossain et al. 2019). Notably, there remains a significant gap in both theory and practice regarding how researchers navigate and negotiate these hybrid roles in LLs and what this engagement entails in their research practice and environment.

To address this gap, the present study adopts the perspective of the researcher, considering the LL as a transdisciplinary research space where innovations are explored within boundaries shaped by the knowledge co-production process (Hermesse & Vankeerberghen 2020; Kruijf et al. 2022). This perspective places the researcher at the core of the analysis, emphasising the mobilisation of diverse forms of knowledge – both experiential and scientific – within a transdisciplinary framework as a key element for driving innovation, i.e. including the root causes of urban sustainability problems, the proposed solutions and the potential for societal uptake (Armitage et al. 2011).

The literature on transdisciplinary research for sustainability transitions offers a broader framework to examine the role of researchers engaged in action research and knowledge co-production processes within LLs (Kruijf et al. 2022; Pohl et al. 2010; Wittmayer & Schäpke 2014). Previous studies have distinguished between the position of an ‘insider’ (a researcher who produces knowledge while actively participating as an actor) and an ‘outsider’ (a researcher who maintains a distance from the field of study) (Louis & Bartunek 1992). However, Herr and Anderson (2015) stress that researchers operate along a continuum between these two extremes.

In-betweenness is another way of characterising the fluid positionality of researchers, according to studies on qualitative inquiry in global south contexts (Jimenez et al. 2022). This concept refers to the intermediary space in which researchers’ practices and relationships with actors become hybridised (Jimenez et al. 2022). In this space, researchers’ positionalities multiply and shift, leading to different knowledge outcomes (Kerstetter 2012). How researchers position themselves in this space is shaped by demographic attributes (such as ethnicity, age, gender and class) (Soedirgo & Glas 2020; Sultana 2007) but also by other factors tied to personal and professional experience (Berger 2015). Others challenge the insider/outsider dichotomy, emphasising that researchers’ positionality is equally influenced by contextual factors linked to institutional, social and political realities in which the research is embedded, which in turn shape researchers’ identity in engaging with these settings (Jimenez et al. 2022). Recognising this in-between space complicates efforts to define researchers’ roles and boundaries in transdisciplinary research, calling for a more nuanced understanding of how these roles are negotiated and redefined.

Recent scholarship has proposed a more nuanced categorisation of the possible roles that researchers may assume when engaging in science–society interfaces (Kruijf et al. 2022; Wittmayer & Schäpke 2014). Within this context, researchers are often viewed as initiators and frontrunners in knowledge co-production processes oriented towards sustainability transitions. Beyond generating data and offering technical expertise, they are frequently involved in leading practical experimentation, fostering trust and collaboration among diverse stakeholders (Qiao et al. 2018) and enhancing the capacity and willingness of local governments to adopt and implement adaptive solutions (Burns et al. 2015).

The present study has built upon this literature on transdisciplinary research and knowledge co-production to develop a conceptual framework for examining the multiple roles of researchers within LLs and the underlying drivers that shape these roles – thereby broadening the understanding of the diverse positionalities that researchers may occupy within the space of in-betweenness.

3. Methods

Driven by their experiences in LLs, the authors’ research began with self-reflection and continued with a more structural understanding of these experiences. The first guiding questions – whether, how and why researchers change and adapt their practice to the LL – were confronted with existing literature on the topic. After a literature review on LLs (both from English- and French-speaking research), the main research question was determined: what roles researchers take during LLs and the drivers behind them. The core of our approach is a conceptual framework that identifies drivers from the process of knowledge co-production (i.e. contextual factors, individual capacities, co-production process and outputs/outcomes) as motivation for the different roles taken by researchers.

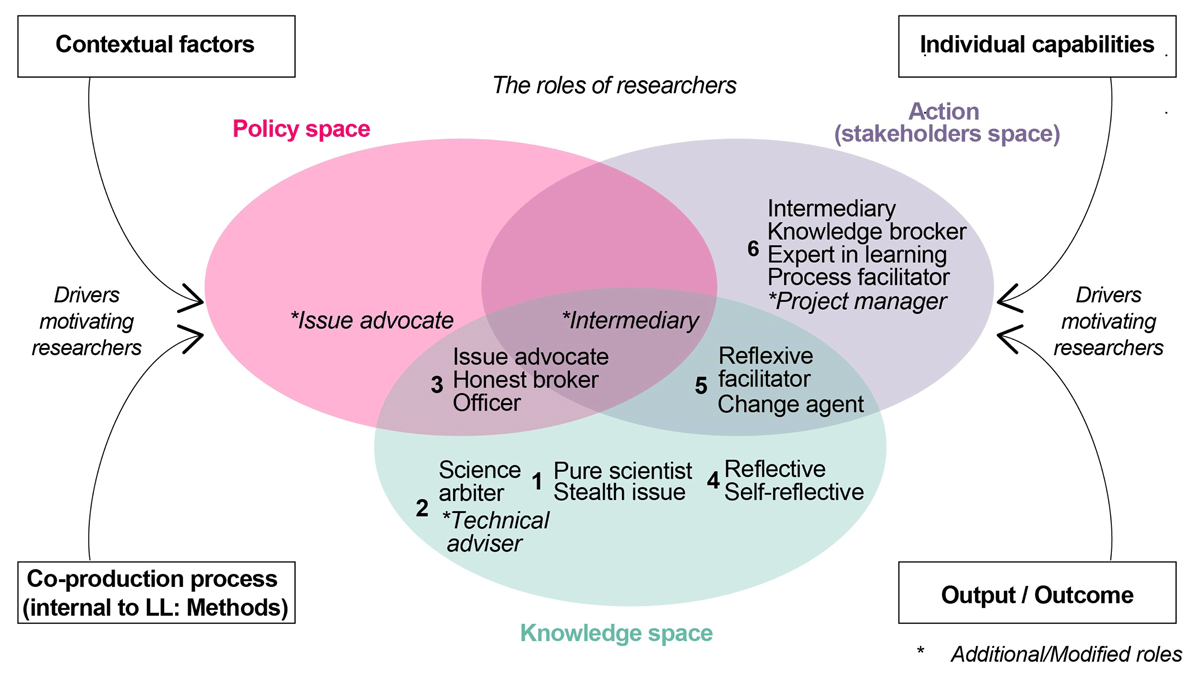

The conceptual framework was adapted and tested through a process of data collection and analysis divided into three main parts carried out in parallel (2022–24) (Figure 1). The first part focused on the conditions of knowledge co-production based on the framework of Schuttenberg and Guth (2015) as drivers for researchers’ roles. Three focus groups were organised with researchers with experience in working in various LLs (Belgium, the Netherlands, Italy, Senegal, Ethiopia, Democratic Republic of the Congo and Tanzania). The wide variety of contexts allowed the exploration of a wide range of conditions to develop the most comprehensive perspective possible that accounts for the evident and relevant contextual differences. The researchers were from natural, spatial and social sciences, and the thematic of their LLs included environmental issues. Carried out in the form of workshops, the focus groups refined the research questions and modified and completed the conditions proposed by the framework.

Figure 1

Scheme of the conceptual framework.

Source: Based on the conditions for knowledge co-production proposed by Schuttenberg and Guth (2015) and the typology of the role of researchers proposed by Kruijf et al. (2022).

The second part concerned the identification of a typology of researchers’ roles, starting from the work of Kruijf et al. (2022). For this purpose, five semi-structured interviews with researchers working within LL in Brussels were used. During the interviews, a mental map (Appendix 1 in the supplemental data online) was created with each researcher identifying their different roles and linking them with the four main conditions (contextual factors, co-production process, individual capabilities and output/outcomes). The third part of the research entailed case study research on two LLs located in Brussels. During this part, the framework was completed with a link between drivers (knowledge co-production conditions) and the roles of actors. The choice of the LLs is related to the authors’ personal involvement in the process that allowed using the data collection archives, documentations and participatory observations collected during the six-year span of the LLs’ activities. Furthermore, the data analysis included the answers from the five semi-structured interviews carried out in the second part of our study, focusing on the relation between conditions and roles of the researchers.

4. Roles of researchers in knowledge co-production framework

4.1 Knowledge co-production conditions

Schuttenberg and Guth (2015) identify three elements of co-production capacity (individual and organisational capacities, socio-ecological system context and co-production process) and three types of outcomes from knowledge co-production (immediate, intermediate and ultimate outcomes). For the present research, the authors organised them into four types of knowledge co-production conditions fitted to LL by maintaining the first three elements proposed by the authors and by merging the outcomes into one condition (output/outcomes).

The first two conditions characterise the context in which co-production occurs: a) the pivotal role of the co-production environment (we use the term contextual factors to refer to the socio-ecological system context); b) the existing individual and organisational competencies of actors involved in the process, here termed individual capabilities. The third and fourth conditions concern c) the knowledge co-production process itself, which refers to the capacity of engaging representative stakeholders, i.e. the co-production process (Schuttenberg & Guth (2015); and d) the results of this process, i.e. output for immediate outcomes and outcomes for intermediate and ultimate outcomes.

During the focus groups’ discussions, the conceptual framework of knowledge co-production of Schuttenberg and Guth (2015) was adapted and further detailed (Table 1 and Appendix 2 in the supplemental data online).

Table 1

Conditions and potential drivers to influencing the roles of researchers, as adapted during the focus group discussions.

| MAIN CATEGORY | CONDITIONS AND POTENTIAL DRIVERS FOR THE ROLES OF RESEARCHERS |

|---|---|

| Contextual factors | Characteristics of social movements |

| Governing institutions and governance systems | |

| Funding schemes | |

| Academic environment* | |

| Cultural and social characteristics and values | |

| Consolidated power dynamics | |

| Ecosystems characteristics and services | |

| Co-production process | Consortium partnership* |

| Funding constraints* (specific to the LL) | |

| Engagement of representative stakeholders | |

| Facilitation of iterative learning (translation) | |

| Employ of adequate methods | |

| External recognition* | |

| Focus on meaningful issues | |

| Use conflict-resolution processes | |

| Individual capabilities | Management skills |

| Legal and policy expertise | |

| Cultural knowledge and practice (relation with the community) | |

| Facilitation capacities | |

| Physical, natural and social sciences | |

| Personal motivations and career status* | |

| Spatial analysis | |

| Outputs/Outcomes | Empowered stakeholders, transformative learning, social capital |

| Salient, legitimate and credible knowledge for policymaking | |

| Knowledge relevant for other scientists (academic products) | |

| Sustainability solutions and changes (effective for the territory) |

[i] Notes: Drivers with * were not mentioned in the Schuttenberg and Guth framework (2015) or were moved from one category of conditions to another.

Drivers in italics were not included.

For more details about each condition, see Appendix 2 in the supplemental data online.

In terms of contextual factors, the focus groups’ discussions confirmed three conditions proposed by Schuttenberg and Guth (2015): characteristics of social movement, governing institutions and governance systems, and funding schemes. Critical issues were discussed regarding each condition. For instance, the characteristics of social movements were described by experts in terms of relations with communities. Sometimes, these were perceived as a challenge: ‘Sometimes you feel like a slave to local processes’ (Expert 2, focus group 3, 2024). Sometimes they were regarded as a duty: ‘How to do research otherwise in context if we do not use transdisciplinary approaches?’ (Expert 1, focus group 3, 2024). As another example, the funding schemes were discussed in terms of how to adapt to calls of funding and to ‘what the territory needs’ (Expert 1, focus group 3, 2024). Furthermore, two conditions were modified: consortium partnership condition was moved to the co-production process category, and a new condition was included specific to researchers: academic environment. Two subcategories from Schuttenberg and Guth’s (2015) framework – consolidated power dynamics and ecosystems characteristics and services – were not included.

For the co-production process category, three conditions were kept from the base framework: engagement of representative stakeholders, facilitation of iterative learning and employment of adequate methods. Three additional conditions were added: consortium partnership, funding constraints and external recognition. As an example, the influence of consortium partnership was a recurrent topic expressed by experts as the ‘tendency to jump in a gap rather than strategically thinking what is better on the longer run’ (Expert 1, focus group 1, 2023). Regarding the co-production process, experts expressed different limitations that might hinder the process of knowledge co-production, such as the great responsibility placed on the LL despite its precarious status or the fear that LL would replace public actions and not lead to new actions.

In the individual capabilities category, the conditions discussed by the experts included all but one of the conditions proposed by the base framework: spatial analysis. The spatial methods used in the fields of architecture and urban planning were included in the physical, natural and social sciences condition. An additional condition was included: personal motivations and career status. As an example of the discussion carried out by the experts, in terms of the cultural knowledge and practice (in relation to the community), experts had a general sense of personal responsibility that was inflicted by the process. This was perceived as a fear: ‘My fear is not towards the neighbourhood, but opposite one, that I am transmitting their voices without being elected’ (Expert 2, focus group 3, 2024). Alternately, it was viewed as part of the research protocol: ‘When we produce knowledge, we participate to it, we distribute it […] it is not just our thinking, but something emerging from the interaction’ (Expert 2, focus group 3, 2024).

In terms of output/outcomes, the conditions proposed by Schuttenberg and Guth (2015) were confirmed: empowered stakeholders, transformative learning, social capital; salient, legitimate and credible knowledge for policymaking; and sustainability solutions, changes and knowledge relevant for other scientists. The conditions proposed are expressed as outcomes rather than outputs. While outputs are developed during the process of LL, outcomes can only be perceived after a certain period after the end of the LL. Experts identified several challenges that might hinder the expected outcomes:

keeping a stable relationship with local actors beside the LL’s timing and following the territorial processes going on

finding time to write, a step usually accomplished after the LL is finalised

developing of generic tools that require adaptation to changing contexts

following up after the end of the project to ensure the impact of outputs.

Additionally, experts expressed their view that researchers should not take the place of local actors: ‘the territory does not need us, we should disappear’ (Expert 1, focus group 3, 2024).

4.2 Researchers’ roles

In terms of the potential roles of researchers, Kruijf et al. (2022) provide a typology of roles from transdisciplinary research. This typology is relevant to the study of LLs for the holistic regrouping of roles among three spheres:

policy, i.e. focus on the production of knowledge in the LL to be used in policymaking processes (Steen & van Bueren 2017)

action (stakeholders), i.e. the capacity of the LL to include needs and to provide value for different stakeholders (Greve et al. 2020)

knowledge, or active ‘testing, trialling, demonstrating and initiating the spread of knowledge’ through a learning-by-doing process (von Wirth et al. 2019: 250).

During the study, the typology proposed by Kruijf et al. (2022) was adapted according to the discussions and interviews carried out with the researchers participating in the study. Two main findings emerged (Table 2).

Table 2

Categories and typologies of roles proposed by Kruijf et al. (2022) with the results of the research.

| CATEGORIES AND ROLES | MAIN OBJECTIVES OF EACH TYPOLOGY OF ROLES | OBJECTIVES IDENTIFIED BY RESEARCHERS INTERVIEWED DURING THE RESEARCH |

|---|---|---|

| Category (1) Knowledge space | ||

| Pure scientist | Deliberate distance from policy | N/A |

| Stealth issue advocate | Production of knowledge disconnected from decision-making process | N/A |

| Technical expert* | Data collection and analysis and restitution towards public authorities and residents. Integration of local knowledge from residents | |

| Category (2) Knowledge space close to policy space | ||

| Science arbiter | Production of evidence for policy | Support on the theoretical concepts used in the LL together with academic and non-academic partners |

| Category (3) Policy space | ||

| Issue advocate | Active contribution to policymaking | Provide knowledge on issues less known by public authorities |

| Honest broker | Production of policy alternatives | Convince public authorities and residents to take certain actions and get involved in experiments |

| Officer | Production of evidence for policy specific to environmental sciences | N/A |

| Category (4) Knowledge space close to action space | ||

| Reflective scientist | Production of knowledge with awareness of the power relationships involved in the process | Connection between the territory and involved communities with relevant theory. Little scientific production owing to time constraints |

| Self-reflective scientist | Production of knowledge with the focus on the own’s involvement in the process | N/A |

| Category (5) Knowledge and action spaces – engagement in the process of facilitation but with an objective to produce knowledge | ||

| Reflexive facilitator | Production of knowledge through an active participation in the process | Production of knowledge about the process in collaboration with others targeting other researchers |

| Change agent | Focus on motivating and providing advice for stakeholders to engage in processes of experimenting alternative practices | N/A |

| Category (6) Action space | ||

| Intermediary | Setting up connections between stakeholders from different spheres | Act between action and production of knowledge |

| Knowledge broker | Translation and combination of knowledge from different sources | N/A |

| Expert in learning | Assistance for stakeholders to learn from the process they engage in | Translate complex and technical knowledge to wider audience |

| Process facilitator | Organisation of the process in terms of who is involved and how | Animation and facilitation of activities without a purpose to produce knowledge. Mediation of internal conflicts (e.g. to find common grounds between partners) |

| Project manager* | Coordination and management of the LL | |

[i] Notes: N/A = not applicable to the researchers who participated in the study.

* = additions or modifications to roles (in terms of the categorisation in one of the three spaces) to the framework.

First, only two roles specific to the knowledge space were identified as pertinent to this project: the science arbiter and the reflexive scientist. Both roles are oriented towards producing knowledge that is usable for the community and territory under study. This had important consequences for the variety of methods used during the co-production process: ‘Each method brings something different: interviews delve deeply, observations capture gestures and interactions, mental maps explore perception, and questionnaires provide an overview’ (Interview 3, 2024). One of the researchers interviewed explained the lack of the role of pure scientist: ‘We are never pure scientists. We use our status in academia as a guarantee, but research (i.e. production of scientific outputs) is never a priority’ (Interview 1, 2024).

Second, two main differences from the proposed framework were observed. The interviewees identified two additional roles that could not fit among the ones proposed by the developed framework in both LLs: project manager and technical expert. These roles were placed by the researchers in the action and knowledge spaces, respectively. Often, the two roles were difficult to combine as they required different temporal dynamics. ‘Time […] is never truly evaluated properly, especially when talking about the time required to complete a task. The time for research is different from the time for a project’ (Interview 4, 2024). On the other hand, two researchers identified the role of the intermediary at the intersection of the three spaces (action, policy and knowledge), while the framework proposes the intermediary between action and knowledge.

5. Results

5.1 Conditions for brusseau living labs

5.1.1 Contextual factors

Brussels has faced water-related challenges in terms of urban flooding in both public and private spaces. Starting in the 1960s, the vulnerability of the territory increased with the growing pace of urbanisation coupled with the changes in precipitation patterns (Davesne et al. 2017). The conventional system of managing stormwater showed its weaknesses, as the increased quantity of stormwater could no longer be managed during storm events by the underground combined wastewater infrastructure (Davesne et al. 2017). Alternative practices, referred to as nature-based solutions (NBSs), manage stormwater as a resource for the urban environment (e.g. to infiltrate in the ground, to store and reuse in households) rather than a source of damage (Fletcher et al. 2014). This movement from managing stormwater underground to the built environment required the reconfiguration of the planning and design process to accommodate collaboration among multiple actors with contrasting needs, including residents (Chaffin et al. 2016). These conditions triggered social movements; in the early 2000s, committees representing neighbourhoods that faced flooding events in Brussels began, with the support of non-profit organisations, to advocate for using NBSs rather than extending the capacity of existing underground infrastructure with large underground retention basins (Kohlbrenner 2010). Slowly, the governing institutions and governance system in Brussels begin to recognise both NBSs – referred to in Brussels as integrated rainwater management – and underground retention basins as complementary practices for flooding protection (Bruxelles Environnement 2016).

To support experimentation, funding schemes proposed by the Regional Agency for Research and Innovation (Innoviris) were created for diverse stakeholders (comprising academics, non-profit organisations, practitioners and public authorities) to collaboratively develop innovative solutions (including NBSs). This favoured the emergence of LLs (De Muynck & Nalpas 2021). Further, the academic environment in Brussels following the examples of European LLs and the opportunities of funding from Innoviris supported the popularisation of research and science within LLs and co-creation. But the researchers involved in the process faced significant challenges to rise to the action-research demands (Damay & Schaut 2022).

5.1.2 Co-production process internal to LLs

Brusseau LL (Brussels sensitive to water) (2017–19) aimed to experiment with NBSs in Brussels through a co-creative process among different actors (including residents) and to demonstrate how this approach to spatial planning and design could increase the resilience of the territory to flood risks. The LL had as a funding requirement to develop a co-creative approach with concerned stakeholders. This consortium partnership was coordinated by a non-profit organisation and was composed of three research centres from the disciplines of hydrology, history of urbanism and architecture, two practice-based organisations and one small or medium-sized enterprise for quantitative measurements (Brusseau, n.d.). The initial objective was to establish hydrological communities driven by a spirit of watershed solidarity; i.e. residents living in the upper parts of the valley would manage stormwater to avoid flooding of the residents living in the lower parts of the valley (Aragone et al. 2022). In this space, the LL focused on actions to bring together residents and users on one side and researchers and practitioners on the other to co-produce knowledge for the diagnostics, planning and design of NBS. The interaction in the LL developed through a variety of methods among researchers, practitioners and citizens was able to offer high-quality co-expertise that enabled collective creativity in the search for solutions to make NBSs more suited to the Brussels territory and the needs of its inhabitants (Dobre & Nalpas 2020).

Brusseau bis LL (2021–23) was the continuation of Brusseau LL. Funded by the same regional agency, the LL experimented and tested a combination of technical, social and environmental tools aimed at addressing various blockages encountered in the planning, design and implementation of NBSs (Dobre et al. 2023). The main change from the Brusseau LL was the focus on policy and action with specific funding requirements to generate replicable tools. Included in the consortium partnership were four municipalities and two regional institutions. Brusseau bis tested the tools during different phases of urban project implementation in a co-creative approach. The LL covered specific issues in governance and legal aspects, economy and finance, community life, landscape and climate, and technical innovations in three of Brusseau LL’s hydrological communities, extending them to three other areas in Brussels. Brusseau bis faced challenges concerning its external recognition of the validity of its results in other areas in Brussels.

5.1.3 Individual capabilities

In total, five researchers worked principally in the two LLs. Three researchers worked with Brusseau LL and four with Brusseau bis LL. Two of these researchers participated in both LLs, and another researcher acted as a practitioner in Brusseau LL and as a researcher in Brusseau bis LL. They had diverse, interdisciplinary academic backgrounds: three were affiliated to research centres in architecture and urban design, one with history of urbanism and one with hydrology. The three disciplines are traditionally classified as natural, applied and social sciences, but the host research centres all had expertise in carrying out interdisciplinary research. Their management skills, legal and policy expertise and facilitation capacities were reduced, as only one of the researchers had previous experience in practice. Another had brief experience in other LL projects. Nevertheless, all but one researcher had in-depth cultural knowledge and practice in developing research or practice-based projects located in Brussels.

In terms of their career status all researchers were either at the beginning of their research or were junior researchers. Their work in the LL was supported by senior academics acting as official coordinators on behalf of the research centre. Only researchers directly funded by the projects were included in the analysis. As testament to the researchers’ close relations, four of the researchers created an independent collective to continue working together after the end of the LLs.

5.1.4 Outputs/outcomes

The main outputs of Brusseau LL were sustainability solutions and changes in the form of reports that included detailed diagnostics and proposals of implementation of NBSs in eight areas in Brussels. The knowledge produced was valued as salient, legitimate and credible for policymaking during feedback sessions but no visible outcomes in terms of influencing policy or triggering new projects were attained. The results were presented during a month-long exhibition punctuated by conferences and guided visits before Brussels entered Covid lockdown. The process of knowledge co-production was presented using short video compilations. Scientific outputs were produced by two researchers carrying out their work in parallel to their PhD thesis. Brusseau LL contributed to an overall increased awareness in Brussels of planning for NBSs through knowledge co-production indicating an outcome of empowered stakeholders and transformative learning. The stability of the consortium partnership and the positive feedback from the funding agency set up the conditions to continue the process.

Brusseau bis LL started with a sense of hope and challenges owing to the uncertainty around doing participatory activities during the Covid pandemic. The long delays at the beginning of the LL were felt towards the end when outputs were expected. The outputs were reports on the use of 11 created tools focusing on salient, legitimate and credible knowledge for policymaking. Knowledge was produced for other researchers and practitioners in the form of guidelines and scientific articles by a researcher carrying out his work in parallel to his PhD thesis. In contrast to Brusseau, Brusseau bis led to the realisation of NBS in six gardens; this had a pronounced effect on those residents who were directly involved in terms of ‘empowered stakeholders and transformative learning’ (Aragone et al. 2023).

5.2 Researchers’ roles in LLs

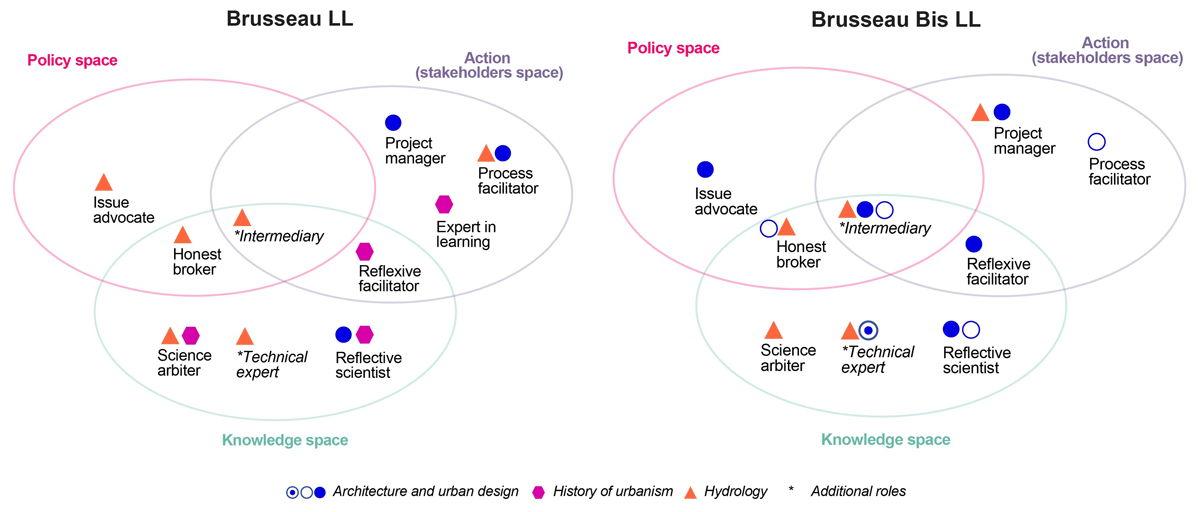

During the two LLs, researchers with different expertise worked in collaboration in a transdisciplinary approach. Their interactions did not follow a continuous line. During each LL, they engaged with the LLs, withdrew from them, and took on different roles within them. Their roles combined covered the three spheres of policy, action and knowledge (Figure 2). Several findings can be drawn from the analysis.

Figure 2

Scheme representing the roles taken by researchers in the two living labs.

Note: Each researcher is represented based on the main field of their affiliated research centres.

First, by looking at the sum of the roles taken by researchers in Brusseau and Brusseau bis LLs, no substantial difference can be observed. Nevertheless, individual researchers changed roles from one LL to another or left the consortium as new researchers joined. As one of the researchers observed, ‘The roles were defined on a case-by-case basis, often depending on availability and needs during coordination meetings’ (Interview 1, 2024). This implies that the type of LL – either action research for Brusseau or policy action for Brusseau bis, changed the individual trajectory of researchers, while the needs of expertise within the LLs remained similar. The differences observed revealed a reduction in the capacity of researchers to act in terms of production of meaningful output/outcomes or to play more reflexive roles (i.e. disappearance of the role of reflexive scientist). The conditions identified by the researchers were financial restrictions, the Covid pandemic and the involvement of public authorities:

[Brusseau Bis] became more technical and less opened to residents. We lost the initial enthusiasm. It was a very difficult period for all the partners and stakeholders involved. In the end the results did not have the expected impact, mostly because of the resistance to change of public authorities.

(Interview 2, 2024)

Second, researchers identified the motivation behind the roles (or the drivers) in relation to the four categories: contextual factors, co-production process (internal to LL – methods), individual factors and the requirements for outputs and outcomes. The mental maps (Appendix 1 in the supplemental data online) produced during the interviews facilitated the linking of the roles taken by researchers with drivers (Table 3). The results confirmed several of the potential drivers identified by the expert groups (Table 1).

Table 3

The drivers identified by researchers respecting their different roles in the Brusseau and Brusseau bis LLs.

| TYPE OF SPACE | ROLE OF THE RESEARCHER | CONDITIONS (DRIVERS) | MOTIVATING THE ROLES |

|---|---|---|---|

| Action (stakeholder) space | Process facilitator | Contextual factors | Characteristics of social movements – rising awareness of environmental challenges (Interview 2) |

| Co-production process | Consortium partnership (Interviews 1 and 3) | ||

| Individual capabilities | Physical, natural and social sciences (Interviews 3 and 4) | ||

| Project manager | Co-production process | Consortium partnership (Interview 3) | |

| Expert in learning | Individual capabilities |

| |

| Knowledge space | Reflexive facilitator | Contextual factors | Academic environment and protocol (Interviews 3 and 4) |

| Outputs/outcomes | Knowledge relevant for other scientists (Interview 4) | ||

| Science arbiter | Contextual factors | Characteristics of social movements – Need of the community (Interview 1) | |

| Co-production process | Consortium partnership (Interview 1) | ||

| Technical expert | Individual capabilities | Previous training in natural and applied sciences (Interview 1) | |

| Co-production process | Consortium partnership (Interview 5) | ||

| Individual capabilities | Cultural knowledge and practice (Interview 5) | ||

| Reflective scientist | Contextual factors | Institutional context (Interview 1) | |

| Contextual factors | Academic environment and protocol (Interview 3) | ||

| Outputs/outcomes |

| ||

| Policy space | Intermediary | Co-production process | Engagement of representative stakeholders (Interview 4) |

| Individual capabilities | Intellectual stimulation (Interview 2) | ||

| Honest broker | Individual capabilities | Researcher taking a militant stance even under external criticism (Interview 2) | |

| Issue advocate | Co-production process |

|

6. Discussion

6.1 Roles taken by researchers

The analysis of the results allowed for a deeper understanding of the role of researchers in LLs, across three key dimensions.

6.1.1 Multiplicity of roles

The findings confirm several insights from the existing LL literature regarding the multiple roles that actors tend to adopt (Hossain et al. 2019; Nyström et al. 2014). Throughout the two LLs examined, researchers were found to assume multiple roles – primarily facilitators, arbiters and brokers – and to perform different tasks depending on the situation and resources available. These roles were predominantly shaped both by the fluid interaction with the other actors in the course of the LLs and by the practical necessity of achieving a specific goal in an action-based perspective, here echoing Nyström et al. (2014).

This multiplicity of roles can be considered a strength for innovation, as it enables researchers to connect exploratory activities with practical actions, thereby bridging the gap between theory and practice within the LL context. However, the constant shifting between roles often leads to blurred boundaries between them. This hybridisation of roles introduces a degree of difficulty for researchers in adopting the appropriate posture, methods and practices required to effectively perform a specific role. In essence, it challenges their ability to navigate the complex space of intermediation, which is defined by the intersection of knowledge, action and policy spaces, which is where most knowledge co-production roles are situated. Further, the hybridisation of roles might lead to overlapping with activities conventionally practiced by other actors; for example, researchers in architecture and urban planning took the role of process facilitators to design projects that are usually done by professional architects. This process might raise questions of professional ethics and insurance of works.

6.1.2 Adaptability of roles

The multiplicity of roles adopted by researchers in LLs is directly linked to another element evident in the cases analysed: their capacity to adapt to existing situations or unfolding events. Rather than selecting roles through a systematic decision-making process, researchers generally adapted to roles through a learning-by-doing approach, guided by their internal understanding of the ongoing co-production process and by the consortium’s needs. They assumed the position they deemed most suitable at a given time to facilitate the co-production of knowledge. This indicates that continuous self-reflection – often implicit – is a recurrent feature underpinning each role that blends the different spaces researchers occupy over the course of an LL. This finding is consistent with the observations of Jimenez et al. (2022): researchers in Brusseau LLs experienced their own in-betweenness either by deciding to take a specific role or by moving fluidly across different roles determined by the multiple relationships established with the other actors in the LLs.

6.1.3 Intermediary space

The analysis has brought forward the specificity of two new roles – project manager and technical expert – that were not previously identified in the framework of Kruijf et al. (2022). Furthermore, the present research has brought more details to the role of the intermediary, located at the intersection of action, knowledge and policy. The findings support the perspective of Petit and Soulard (2015) regarding the different individual capabilities driving the role of intermediary: previous background as a practitioner (Interviewee 4), researchers arriving in the consortium as an external such as research associate (Interviewee 2) and researchers taking the role of project manager because of organisational competencies (Interviewee 3).

6.2 Drivers behind the roles

Analysis of the results from the focus groups and the in-depth case study research of Brusseau LL led to understanding the drivers that shape the roles taken by researchers divided in four categories: contextual factors, co-production process, individual capabilities and output/outcomes. These findings point out certain recurrent conditions that are of particular interest for researchers.

First, in terms of contextual factors, the characteristics of social movements, specifically the relationship to the community in which the LL acts, has a strong influence on the role of the researcher. Previous research has indicated that the connection can take the form of responsibility towards the community (Bergvall-Kåreborn et al. 2009) or adaptation of research to community needs (Franz 2015). Another driver often mentioned from this category was the academic environment.

Second, from the co-production process, the consortium partnership is a strong influence in the way it is organised, which roles are taken by the other partners, and what gaps remain. Researchers appear to have a certain flexibility in switching roles than the other partners (e.g. non-profit organisations, public authorities or practitioners). Another recurrent driver from this category was the engagement of representative stakeholders as a particular motivator for researchers to take roles closer to the policy sphere (e.g. issue advocate or honest broker).

Third, from the individual capabilities category, previous training in the disciplines of natural science (e.g. hydrology), applied spatial sciences (e.g. architecture and urban design) or social sciences (e.g. anthropology) was a guiding driver for researchers to take upon more action-oriented roles such as expert in learning, technical expert or process facilitator.

Fourth, the output/outcome category (in terms of producing knowledge relevant for other scientists and in developing sustainability solutions and changes) motivated in particular the reflexive roles: facilitator or scientist.

7. Conclusions

Drawing on a three-step analysis that includes an in-depth case study of the Brusseau LL experience in Brussels, this study has provided a reflective and empirically grounded exploration of the multifaceted and shifting roles that researchers may assume within LLs, along with the potential conditions that shape these roles. The study has highlighted the complexity and fluidity of researchers’ roles, which shifted dynamically across different LLs in response to internal and external conditions. By linking lived experience with theoretical insights, the study contributes to an emerging field of inquiry by interrogating the active role of intermediary actors, such as researchers, in co-producing actionable, context-sensitive knowledge within LLs. Furthermore, it proposes a coherent and structured approach to better equip researchers to navigate the complexities of transdisciplinary action research in response to pressing urban and environmental challenges.

The conceptual framework developed in this study is a valuable analytical tool to explore the different possible positionalities that characterise the in-betweenness of researchers’ roles within LLs at the intersection of knowledge, action and policy spaces. Furthermore, the conceptual framework details the conditions of co-producing knowledge in the context of LLs shaping researchers’ roles, which differ from traditional multidisciplinary research settings. The difference, for instance, is particularly visible in the weight of the consortium partnership and the engagement of relevant stakeholders on the activity of researchers. Practically, knowledge is produced predominately through a process of learning by doing concrete actions influenced by the constant input of ‘others’ members of the LL (from outside the academic realm).

While the framework has demonstrated relevant explanatory capacity, further refinement and empirical testing in other contexts would be beneficial to expand on the following issues. First, the framework could not capture the relationships between individual drivers and specific roles but rather the connections between drivers and the hybridisation of roles. Second, further development of the framework could allow following the evolution of individual researchers from one LL to another – for instance, researchers involved in both Brusseau LLs gained experienced in one role, which led them to take on a different role – and the complementarity of activities among researchers that are not fitted to a specific role, i.e. a realignment occurred among researchers to ensure no overlapping of activities and reinforcement of capabilities. Last, the framework could be enlarged in examining how other actors within the LL – e.g. NGOs, practitioners or public authorities – might assume complementary or overlapping functions. A more holistic analysis involving all actors would allow for a richer assessment of how tasks, responsibilities and knowledge practices are negotiated across the LL.

This study opens several avenues for future research. From a theoretical standpoint, it encourages deeper examination of the mechanisms that researchers employ to steer and sustain knowledge co-production. This includes understanding how researchers adapt their methods, manage their positionality and navigate power relations throughout the iterative phases of LLs. From a practical perspective, the findings offer guidance for researchers to create better knowledge co-production processes by recognising and articulating their roles, aligning expectations and making informed decisions. Such awareness can enhance both the quality of engagement and the integrity of the knowledge produced. However, this engagement also entails a significant epistemological shift: from detached observation to situated, co-productive participation. While LLs hold strong potential for transformative innovation, there is a risk that their product-oriented nature may overshadow the critical and reflective role of researchers. Care must be taken to ensure that knowledge production remains central to the process, rather than being subordinated to instrumental project outcomes.

The Brusseau LLs case demonstrates that the capacity of researchers to perform different roles is both a strength and a challenge. While adaptability is fundamental to enable researchers to bridge gaps between theory and practice and to contribute to the design and implementation of inclusive sustainability solutions, it also exposes them to role ambiguity, tensions in aligning academic and societal expectations, and difficulties in sustaining long-term engagement. In this regard, a key insight emerging from this study is the importance of individual and collective reflexivity as a guiding principle for researchers engaging in LLs. The ability to reflect on their positionality, motivations and interactions with stakeholders allows researchers to navigate complex environments and to better align their actions with the evolving needs of the co-production process.

Ultimately, future research should examine how researchers influence and are influenced by the dynamics of knowledge co-production, and how their identities, research practices and agency evolve within LLs. Longitudinal and cross-contextual studies are especially needed to trace these evolutions and to uncover how researchers mediate between scientific rigor and societal relevance in increasingly hybrid research environments.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the researchers involved in the study for sharing their reflections, and to the editor and the two reviewers for their valuable advice.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Data accessibility

The data that support the findings of this study are available in Diffusion ULB at http://hdl.handle.net/2013/ULB-DIPOT:oai:dipot.ulb.ac.be:2013/394632. The dataset includes results from the focus groups, extracts from the transcripts of interviews and mental maps, and has been anonymised to ensure participant confidentiality. Any additional data related to this article may be requested from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at: https://doi.org/10.5334/bc.622.s1