1. Introduction

The Eighth Environmental Action Programme of the European Union (Decision 2022/591; European Union 2022) requests that member countries reduce their consumption footprints to comply with the limits of planetary boundaries. The required reductions, especially in energy-intensive consumption categories of housing, food and household goods (EEA 2023b), are notable and hard to achieve. The European Environmental Agency (EEA) (2023a) emphasises three different strategies for reducing the footprint: consuming differently, scaling up eco-design and consuming less.

Consuming less or setting caps on consumption is a solution suggested by researchers under different conceptual frameworks, e.g. strong sustainability (Lorek & Fuchs 2013), one planet living (Desai & Goncalves 2008), 8-ton material footprint (Lettenmeier et al. 2014), safe and just space for humanity (Raworth 2012) and degrowth (Kallis 2017). The sufficiency concept was articulated by Princen (2003) and developed further by several other scholars (e.g. Dietz & O’Neill 2013; Spangenberg & Lorek 2019; for an overview, see also Jungell-Michelsson & Heikkurinen 2022). Promoting sufficiency in consumption (i.e. avoiding both overconsumption and scarcity) is a considerable challenge for policymakers due to potential opposition from the public.

Sufficiency policies can be defined as:

a set of measures and daily practices that avoid demand for energy, materials, land, and water while delivering human wellbeing for all within planetary boundaries.

Identification of potential policies that could be both acceptable and yet impactful is not simple (e.g. Ahvenharju 2020). Foulds et al. (2022) found that current understandings of energy policy instruments and energy efficiency are often based on the assumptions and expectations of experts and maintained by those who benefit from the status quo, such as the wealthy. Furthermore, as researchers of a study including 1500 households suggest, there is no universally acceptable way to set consumption limits (Lavelle & Fahy 2021). Instead, tailored, context-specific solutions are needed.

This paper examines the acceptability of energy sufficiency policies by households in Finland in order to provide insights into households’ attitudes regarding sufficiency as a guiding principle for sustainable energy consumption. The research questions were as follows:

In what ways do the Finnish households find the proposed sufficiency policies acceptable?

How do the Finnish households justify their position towards the sufficiency policies?

How do the circumstances of households influence the acceptance of sufficiency measures?

The context of this study, Finland, is often considered a European forerunner in climate policy. The research will thus provide insights into energy policy, sustainable consumption and the built environment in Western and especially Northern European welfare state contexts.

The focus of the paper is on housing, first, because it accounts for over a fifth of the final energy consumption in Finland (Odyssee-Mure Database 2024) and nearly a third of the carbon footprint of an average Finn (Nissinen & Savolainen 2019). Second, the emissions from housing are largely determined by energy efficiency and the source of energy as well as consumption patterns, the latter of which currently undermines the emission reduction potential of this consumption category (Nissinen & Savolainen 2019).

A total of 39 household interviews were conducted in Finland in 2023. Inspired by earlier studies on consumption reduction in Finland (Ahvenharju 2020, 2021), a set of sufficiency policy measures (SPMs) was presented to the participants to evaluate the acceptability of these SPMs. Since citizens have limited experience of SPMs, a qualitative study with the opportunity to discuss the policy instruments was deemed more appropriate than a survey. The SPMs chosen for this study include those that promote new norms of a less resource-intensive lifestyle (enabling), improve one’s knowledge (informative) and limit the overconsumption of energy and other natural resources (disabling).

The article is structured as follows. Section 2 describes some Finnish energy and housing policies relevant to this study. Section 3 introduces the key concepts and theoretical background of the study. Section 4 describes in more detail the materials and methods of the study. Section 5 presents the results of the interviews. Section 6 concludes.

2. Climate policies and household energy consumption in Finland

Finland has a long tradition of being a pioneer in sustainability policies and it has scored highly on many global environmental policy rankings as well as social policy comparisons (e.g. Block et al. 2024; Helliwell et al. 2023). Despite all the active environmental policies, Finland exceeds the limits of at least six of the biophysical indicators identified by Fanning et al. (2022), most of them by nearly three or four times. Also, while its territorial climate emissions have decreased by 21% since 2005, if consumption-based emissions are included in the calculations, the level of emissions has not decreased at all (Linnanen et al. 2020).

In 2021, the largest share of Finnish energy consumption in housing originated from space heating (63%), followed by water heating (15%), appliances and lightning (13%) and saunas (4%). The final energy consumption of Finnish housing has increased during the 21st century, mainly due to the growth in the number and size of dwellings (Odyssee-Mure Database 2024). The floor area per person has increased partly due to the change in the comfort norms of living conditions (Aro 2016), but also because single-person households have become increasingly common. Smaller household sizes increase the need for space heating on a macro-level (Heiskanen & Laakso 2019), which increases the energy consumption of housing overall. Therefore, to curb the growing energy consumption and to provide adequate floor space for everyone, individual consumption moderation needs to be accompanied by changes in societal structures and climate policies (Cohen 2021).

Regarding the incentives for energy-saving, most urban areas in Finland have municipally owned district heating, and residents pay a fixed fee independent of their actual consumption (Kyrö et al. 2011). Exceptionally, the inhabitants of detached houses are billed for their actual consumption of energy and water. The government has invested especially in awareness-raising: free energy advice is available for all households, and energy companies are obliged to inform their customers about their consumption (Apajalahti et al. 2015). Energy prices have traditionally been relatively stable and low in Finland (Laakso et al. 2024), which has not encouraged saving energy.

However, the energy crisis, which began in late 2021 and was accelerated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 (Laakso et al. 2024), had a major impact on the general level of awareness among Finnish inhabitants: During the crisis, households were encouraged to save energy by the national energy saving campaign ‘Down a Degree’ (Motiva 2023), and in 2022, nine out of 10 people reported to have made efforts in energy-saving (Matschoss et al. 2024).

3. Acceptability of sufficiency as a policy challenge

Various SPMs have been proposed by researchers to increase energy sufficiency in housing. These include increasing co-sharing of building spaces, providing advice on energy consumption and living space, instruments for limiting average dwelling floor area per person, stopping incentives for single-family housing, personal carbon quotas, consumption feedback with smart meters or smart billing, carbon or energy taxes, carbon allowances for buildings, efficiency standards and building codes (e.g. Thomas et al. 2019; Bertoldi 2022; Sandberg 2021). However, these opportunities for sufficiency in housing have hardly been utilised (Bagheri et al. 2024; Zell-Ziegler et al. 2021). As a recent review of Finnish Climate Policy Plans shows, SPMs have not yet been included as part of energy policies in Finland (Nuorivaara 2024). However, the potential for sufficiency-oriented policies has been brought to the public discussion in a report by the Finnish Climate Change Panel (Linnanen et al. 2020).

The challenge with SPMs is in their presumed (un)popularity with policymakers as well as inhabitants. SPMs may be considered efficient, but their acceptability low (e.g. Ahvenharju 2021; Lehner et al. 2024; Ruokamo et al. 2024). Policies that present absolute limitations are generally considered a breach of individual freedom as well as a threat to the paradigm of economic growth. However, if the policies are perceived reasonable and fair, citizens might also be supportive of SPMs (Lage et al. 2023; Jenny et al. 2024). The present article contributes to this scattered field of studies on the opinions of the public on the acceptability of SPMs. The acceptability of public policy initiatives has been studied widely, and multiple contributing factors have been identified in various studies. Four aspects that influence popular support for policy measures are as follows:

type of policy measures

policy goals

perceived quality of the policies

attitudes and worldviews of the individuals making the assessment.

Regarding the types of policy measures, environmental policies that are informative or based on nudging (soft measures) are found in many studies to be more popular than policies that introduce laws or taxes (hard measures) (e.g. Cherry et al. 2012; Ejelöv et al. 2022). While soft measures leave the freedom of choice to the consumer, hard measures often limit that choice or make it very expensive. However, it has been suggested that the differences in preferences between soft and hard policies may not be that notable, and they have been exaggerated by study designs including small numbers of varying policies (Ejelöv et al. 2022). Another aspect in terms of the type of policy measure is the extent of the behaviour change the policy is aiming to achieve. Policies requiring only little effort from individuals target so-called low-cost behaviour change, whereas high-cost behaviour change requires a notable effort, and hence raises more opposition (de Groot & Schuitema 2012).

Research in the UK and Switzerland during the COVID-19 pandemic indicated that government regulation requiring high-cost behavioural change was more acceptable to those who were committed to the policy goal of mitigating the pandemic (Kukowski et al. 2021). Hence, the more the aims of the policies coincide with the goals of individuals, the more popular they are. This emphasises the importance of problem awareness. In addition to being knowledgeable of the problem itself, e.g. climate change, the awareness of potential negative impacts and concern for their risks determine favourable attitudes towards policy measures (Drews & van den Bergh 2016; Grelle & Hofmann 2023).

Concerning the perceived qualities of policies, acceptability of environmental policies is influenced by their perceived efficiency or effectiveness (for an overview, see e.g. Drews & van den Bergh 2016). Also, perceived fairness plays an important role: who is seen to lose or gain from the policies? Interpretations of the impacts, e.g. how the costs will be distributed and who will be carrying the main responsibility for changing behaviour, have a significant impact on policy acceptability (Drews & van den Bergh 2016; Grelle & Hofmann 2023).

Finally, studies on the acceptability of policy measures have identified multiple factors related to the attitudes and worldviews of individuals. Personal norms and sense of personal responsibility as well as biospheric values have been shown to influence the acceptability of energy policies (Steg et al. 2005). Lack of trust in the cooperation of others increased support for governmental intervention during the pandemic (Kukowski et al. 2021). A similar finding was made in Switzerland and Germany: the acceptability of climate policies was strongly predicted by distrust in the pro-environmental behaviour of others (Kukowski et al. 2022). In addition, political ideology has an impact: individuals with a preference for a left-wing political ideology have been found to be more positive towards climate and environmental policies (Drews & van den Bergh 2016; Ejelöv et al. 2022). Furthermore, the extent of trust in the intentions of governmental institutions to promote the common good and welfare of voters plays an important role in the assessment of the necessity and impact of governmental intervention, and hence the acceptability of the policies to be introduced (Faure et al. 2022; Grelle & Hofmann 2023).

As suggested above, finding generally acceptable measures for sufficiency may be challenging if the level of crisis awareness has not penetrated society. This concerns especially measures that focus on absolute reductions in total consumption, since they require the implementation of regulatory and tax policies. However, some recent studies have suggested that more stringent policies may be found acceptable by lay persons, while civil servants and experts are more hesitant to support such policies (Ahvenharju 2020; Defila & Di Giulio 2020; Lage et al. 2023).

4. Materials and methods

4.1 Sufficiency consumption policies

The SPMs in this study were selected based on a study that identified strong sustainability policy measures in the context of Finnish household consumption (Ahvenharju 2020). These measures were chosen because, first, they had been formed with Finnish environmental policy experts ensuring their contextual fit. Second, the measures adhere to the general ideas of sufficiency by being fair, radical in terms of demand-reduction targets for natural resources, and non-technical (i.e. not promoting certain types of technologies). The seven chosen measures (Table 1) were adjusted to better target the main uses of final energy consumption in housing.

Table 1

Sufficiency policy measures (SPMs).

| MEASURE | |

|---|---|

| Enabling |

|

| |

| |

| Informative |

|

| Disabling |

|

| |

|

Inspired by Ahvenharju (2020), the SPMs were classified into three types: enabling, informative and disabling measures. By producing new systems or rules, the enabling policy measures endorse and reward lifestyle choices that consume fewer resources: Shared use of living space refers to increasing the number of shared spaces, such as common living areas or guest rooms, to limit demand for space heating. It would also likely have an indirect effect on the number of electric appliances and lighting and the number and usage of saunas. Sharing saunas and washing facilities would reduce the frequency and duration of warm water consumption and limit the need for space heating. Trading working hours for free time, in other words, having the possibility to switch work more flexibly to leisure time, would reduce paid working hours and result in more free time, which could lead to people earning less money and, consequently, consuming less energy.

Informative policy measures, such as monthly report on individual electricity consumption, steer the consumption of energy in a preferred direction without obliging. Household-level consumption-reporting would inform citizens in an accessible and comprehensive format about their level of energy consumption and emissions compared with their neighbours, and the opportunities for energy savings.

A lifestyle that consumes many resources is made more costly and otherwise difficult by disabling policy measures. These include restricting the size of apartments, in other words, setting a maximum limit to the housing square metres per person, which would reduce the amount of energy needed for space heating. Setting in place specific resource taxes, which would target products or services that have a high impact on the environment and resource consumption, would limit the consumption of, for example, fossil fuels. By introducing higher income tax, especially the consumption of the most affluent, could decrease, and thus the overall housing related emissions could be limited.

4.2 Interviews as a form of deliberation

To investigate households’ views on SPMs, 39 qualitative semi-structured interviews were conducted between 26 January and 16 March 2023. The beginning of 2023 marked the end of the energy crisis. Thus, the households were reasonably familiar with having to consider their mundane energy usage, and it offered a unique opportunity to study sufficiency in a household context. The interview framework (see Appendix 1 in the supplemental data online) consisted of four parts. The focus of this paper is on the fourth and final part of the interview, in which the participants were presented the set of SPMs (Table 1).

After briefly introducing these policy prompts, the participants were asked to evaluate their acceptability and feasibility. The interviews allowed adequate time for the participants to reflect and reason on their opinions and arguments and explore them safely with the interviewer. This internal reflection process—the so-called ‘deliberation within’—has been noted to play a significant role in changing participants’ attitudes during deliberative processes (Goodin & Niemeyer 2003; MacKenzie & Caluwaerts 2021). It provided the authors with a more in-depth understanding of the logic of their argument as well as of the potential causes of hesitation.

Part of the interviews were conducted face to face (n = 14) and the rest (n = 25) remotely via Zoom or Teams. The interviews were conducted in Finnish by three researchers, including the first author. Each participant was asked to give written consent or a verbal agreement to participate in the study before the interview. To protect the privacy of the participants, the interview recordings were stored on a protected hard drive and the anonymised transcripts were kept in the personal home directory of the university network. The duration of the interviews varied from 49 to 164 minutes.

4.3 Characteristics of the interviewed households

A large majority of the participants (n = 30) were recruited through an energy questionnaire survey on energy saving and energy literacy conducted in 2022 (Numminen et al. 2023). All lived in the Uusimaa region, which is the most populated region in Finland. The rest of the participants (n = 9) were found through researchers’ personal connections from the Uusimaa region (n = 1), Päijät-Häme (n = 1), Central Finland (n = 3) and Lapland (n = 4). In addition to the place of residence, a variety of background information was gathered about the participants, their household and homes through a survey before conducting the interviews (Table 2). For a more detailed description of the participants, see Appendix 2 in the supplemental data online.

Table 2

Description of the study’s participants.

| Main occupation n (%) | Student/unemployed | Part-time employed | Full-time employed | Retired |

| 5 (12.8%) | 1 (2.6%) | 17 (43.6%) | 16 (41%) | |

| Age range (years) n (%) | 25–34 | 35–44 | 45–64 | ≥ 65 |

| 6 (15%) | 7 (18%) | 10 (26%) | 16 (41%) | |

| Level of education n (%) | Basic education | Upper secondary education | Higher education: bachelor’s degree or equivalent | Higher education: master’s degree or equivalent |

| 0 | 15 (38%) | 17 (44%) | 7 (18%) | |

| Place of residence n (%) | Uusimaa | Päijät-Häme | Central-Finland | Lapland |

| 31 (79%) | 1 (3%) | 3 (8%) | 4 (10%) | |

| Housing type n (%) | Apartment building | Terraced house | Semi-detached house | Detached house |

| 17 (43.6%) | 1 (2.6%) | 2 (5%) | 19 (48.7%) | |

| Area (m2) n (%) | 0–79 | 80–99 | 100–149 | ≥ 150 |

| 16 (41%) | 4 (10%) | 11 (28%) | 8 (21%) | |

| Permanent residents in the household n (%) | 1 | 2 | 3 | ≥ 4 |

| 10 (26%) | 23 (59%) | 2 (5%) | 4 (10%) | |

| Gross annual income of the household (€/year) n (%) | 0–39,999 | 40,000–79,999 | 80,000–99,999 | ≥ 100,000 |

| 13 (33%) | 16 (41%) | 4 (10%) | 6 (16%) |

Apart from one, the youngest participants (25–34-year-olds) were either students or part-time employed, who lived in apartment buildings with a smaller than average floor area (< 80 m2) (OSF 2022a) and belonged to the lowest income level (< €19,999/year). In fact, over half of all participants (n = 23/39) earned less than the Finnish mean gross income of €59,815year (OSF 2022b). Most of the full-time employed participants were 35–64-year-olds (n = 16/17) with a household gross annual income of €60,000/year or more (n = 11). They lived in detached houses (n = 10) (most of which were > 100 m2, n = 8), apartment buildings (n = 6) or in a terraced house (n = 1). All participants > 65 years old (n = 16) were retired, and most of them (n = 9) lived in detached houses > 100 m2. Their income level varied from low (€20,000–39,999/year) to very high (€100,000–150,000/year). Little over half of the participants (n = 23/39) lived in two-person households (the average household size in Finland; OSF 2017), and only five households were families with children.

4.4 Analysis of the interviews

The analysis was made in three steps. First, the responses of the participants to each suggested SPM were rated on a scale from ‘yes’ (agree), ‘maybe yes’ (mostly agree), ‘maybe’ (neutral/undecided), ‘maybe no’ (mostly disagree) to ‘no’ (disagree) to define their acceptability. If the participant was essentially in favour of a measure but they expressed even a slight hesitation towards it, the answer was classified as ‘maybe yes’ instead of ‘yes’. Likewise, if the participant was not completely against the measure, but they resisted it, the answer was classified as ‘maybe no’ instead of ‘no’. The response was put into the category of ‘maybe’ if the participant was not clearly for or against the measure.

Second, the opinions and arguments of the participants were thematically analysed using the qualitative data analysis tool ATLAS.ti. Their views on enabling, informative and disabling measures are systematically divided into supporting, opposing and hesitant ones (see Appendix 3 in the supplemental data online).

Third, the responses were categorised according to the aspects that influence popular support for policy measures derived from earlier studies (see Section 3), and an additional category of socio-demographic factors was added to complement the analysis.

5. Results

5.1 How acceptable are spms among households?

Overall, the SPMs gained more sympathy from households than might be expected based on studies with, e.g. the elite (Ahvenharju 2020) (Table 3). Several measures invoked a positive response. Considering all the SPMs, there were twice as many definite expressions of acceptance as there were definite rejections, while several measures were met with some hesitancy.

Table 3

Acceptability of the sufficiency policy measures (SPMs).

| YES | MAYBE YES | MAYBE | MAYBE NO | NO | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enabling |

| 15 | 10 | 9 | 3 | 2 |

| 14 | 8 | 12 | 3 | 2 | |

| 22 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 3 | |

| Informative |

| 21 | 7 | 5 | 0 | 3 |

| Disabling |

| 5 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 26 |

| 19 | 5 | 10 | 2 | 3 | |

| 12 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 14 | |

| Total numbers of expressions of acceptability | 108 | 41 | 49 | 19 | 39 | |

[i] Note: Bold numbers represent the most popular reaction to each policy measure and highlight the variation of responses: most policy measures were accepted, but some with met with resistance.

The most favoured SPMs were the enabling measure of trading working hours for free time and the informative report on electricity consumption. The disabling measure of specific resource tax was preferred (‘yes’) by nearly half of households, but it also caused relatively many uncertain (‘maybe’) reactions. The enabling measures of shared use of living space and shared use of saunas or washing facilities were relatively popular among households. However, the share of uncertain (‘maybe yes’, ‘maybe’ and ‘maybe no’) reactions to these measures is higher than positive (‘yes’) or negative (‘no’) answers. The disabling measure of higher income tax is the most divisive measure. There were almost as many households for as well as against or neutral towards it. The disabling restrictions to the size of apartments was the least favoured policy measure.

5.2 Households’ arguments and opinions pro and con sufficiency measures

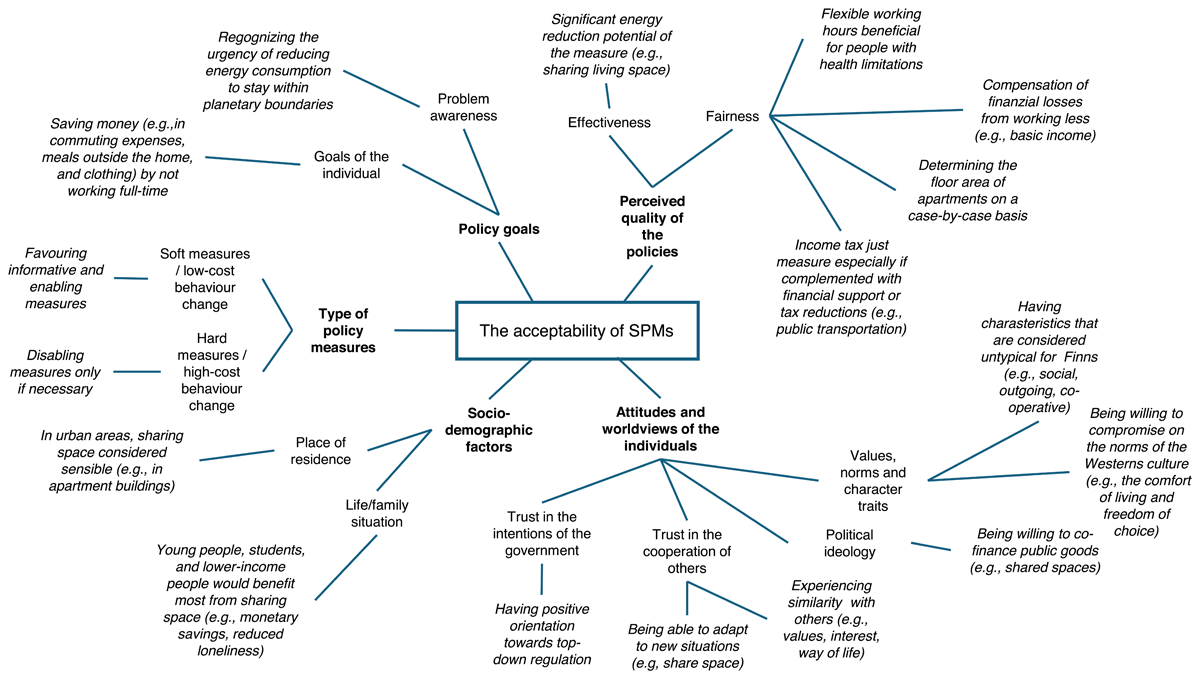

The arguments and opinions of the households presented in this section highlight the factors that influence the acceptability of each SPM. They are classified according to the four aspects discussed in Section 3: the type of policy measures, policy goals, the perceived quality of the policy measures, and the attitudes and worldviews of the respondents as well as socio-demographic factors (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Factors increasing the acceptability of sufficiency policy measure (SPMs).

5.2.1 Type of policy measures

Soft measures that required a low-cost behaviour change, such as the report on electricity consumption, were favoured over hard measures aiming at high-cost changes, although there is no clear-cut definition for which type of measure belongs to which category. Instead, it depends on the individual. For example, sharing living space or saunas and washing facilities was a major change for some while others found it relatively easy:

I would be willing to go to a [shared] sauna, even to a neighborhood sauna or to a common sauna of the residential area, there would not have to be a sauna in every house necessarily.

(H19)

Public support for and the political will to introduce any hard measures were estimated as low by the participants. Harder measures were considered justified if softer measures were not sufficient, and the grounds for using them are well-founded. Limitations should be explained to the public clearly to increase their acceptability, and for that reason informative measures should precede the disabling ones. The latter could be introduced gradually over time.

5.2.2 Policy goals

Discussion on higher income taxation triggered opinions on the goals of the individual and economic incentives to work. Similarly, some households stated that a specific product tax ‘undermines the rewarding nature of paid work’ (H13) and that it feels like a punishment for earning money and ‘succeeding’. Moreover, the households opposing trading working hours for free time identified themselves as ‘greedy’ or ‘workaholic’. However, the measure also provoked thoughts on the monetary savings from commuting expenses, meals outside home and working clothes:

It seems to me that some people have this mystic idea that one has to work full time in order to make a living. But then, working in its own way also takes money away from you.

(H1)

Problem awareness and alignment with the policy goals clearly had an impact on the level of acceptability of restricting the size of apartments. The arguments in favour recognised the urgency of reducing energy consumption, and planetary boundaries were mentioned as a suitable way to limit consumption comprehensively. The opposing arguments did not consider the current situation as a crisis, and thus they were unwilling to sacrifice their comfort of living:

I don’t accept this [laughter]. Well, not at the moment at least. Because in my view, the situation is not at all that bad. As a comfort-loving person, I need space around me [laughter].

(H21)

Likewise, some households argued that a predetermined baseline level of energy consumption that the report of individual electricity consumption would likely contain should be based on the carrying capacity of nature, whereas some wanted to determine the limits of one’s consumption independently.

5.2.3 Perceived quality of the policies

The perceived effectiveness increased the acceptability of measures in general. However, some households questioned the energy reduction potential of shared spaces and working fewer hours. For example, shared use of saunas could tempt people to use more water since ‘it is included in the ticket price’ (H17). Regarding trading working hours for free time, some worried that having more free time could lead to people consuming even more (H33). It was also pointed out that gathering and sharing information for the report on electricity consumption might be energy-intensive in itself. Additional information was not considered necessary by some, since the knowledge level of the public was estimated to be high:

But, indeed, now certainly this crisis at the latest has made everyone aware of what their own electricity bill is made up of.

(H12)

The possibility to decline receiving the consumption report was considered important among the households. Some expressed a worry that too frequent reporting could lead to an information overload. Instead of a monthly report, longer reporting periods or making the information more easily available, e.g. by attaching it to the electricity bill or by offering the information through an app, were argued to increase the acceptability of the measure. The report was considered useful if it were easy to understand and contain concrete examples of one’s energy consumption levels and tips on how to reduce consumption in practice.

In addition to effectiveness, fairness of the measure influenced the perceived quality of all policies. Socio-economic differences between people and their varying needs caused concern about the equality of the measures. While some households considered having more flexible working hours as beneficial, e.g. for people with health limitations, others doubted the fairness of the enabling measure of trading working hours for free time: would working fewer hours be possible for people from lower income levels in the current period of inflation? Some considered working less to be more suited for people with permanent employment, but not for people with a more uncertain source of income. Few participants argued that the financial losses from working for shorter hours should be compensated, e.g. by basic income, having a personal support system and vigilant management of household finances.

The general idea of the disabling instrument of restricting the size of apartments was supported, but the respondents found this difficult in practice. There were concerns, for example, how the needs of people with restricted mobility would be met. The fairness could be ensured, according to the participants, by determining the floor area of apartments on a case-by-case basis. Fairness of the higher income tax also raised discussion. The arguments in favour considered it a just policy measure because it treats everyone equally. The hesitant arguments expressed a concern that higher income tax would hit harder people with lower incomes, since the wealthy will always find ways to avoid such regulation. Thus, the income tax should be complemented with financial support or tax reductions for public transportation and cycling.

5.2.4 Attitudes and worldviews of the individuals

The perceived characteristics of Finns, which impacted the participants’ personal norms, influenced the acceptability of the measures regarding shared spaces. Sociability was mentioned as a personality trait of people to whom it suits well, whereas valuing alone time, peace and privacy were listed as characteristics of people less suited for sharing spaces. On the one hand, shared use of living space was argued to be beneficial for society as a whole because living in a community requires having to negotiate with others. On the other hand, it was regarded to be better suited for people from more collectivist cultures. As phrased by a household:

I think that kind of collective spirit is perhaps a bit more foreign to us, compared to other cultures, indeed, we are such an individualist bunch: me and my very own [are important]!

(H34)

The suggestion that the report of individual electricity consumption could include information of the consumption levels of one’s neighbours also sparked a discussion on its behavioural impacts: if a household consumed less than its neighbours, the report might encourage them to consume more as well, or to feel superior to their neighbours. Since the comparison between households might turn out to be confrontational, the reporting should be anonymous.

I am sure this is suitable for Finns. We are always comparing ourselves to our neighbors here.

(H8)

Reflecting the norms of Western culture, preserving freedom of choice was considered important for acceptability. Sharing living space was often considered the last resort and a temporary arrangement for people who lack any other option. By improving the living comfort of shared living, e.g. by organising spaces for loud and shared activities as well as silence and privacy, more people felt they could voluntarily choose shared living.

The specific product tax elicited discussion of the definition of luxury: it was considered suitable for non-essential products, which are unsustainable for the planet, consume a lot of energy and can be replaced with a more ecological option. Whereas the arguments in favour of taxing products considered the consumption of, for example, meat to be a conscious decision, the opposing arguments stated that it is ‘a normal food product’ (H1) and especially domestic meat should not be taxed to guarantee self-sufficiency of food production in Finland.

The attractiveness of sharing saunas and washing facilities would increase if, for example, there were free online booking and individual entrance codes to uphold cleanliness. However, some argued for a usage-based payment system to provide funding for public laundry rooms, thus reflecting their political ideology:

I am not such a socialist person, so as to believe that others should pay for my laundry bills.

(H5)

Enabling and informative measures were overall favoured over the disabling ones since they functioned within the mainstream political and economic system. The opposition towards restrictions was specifically clear in the case of restricting the size of living space because limiting freedom of choice was regarded as a threat to basic human rights:

That is kind of, sounds a bit like the old-time Soviet Union, it isn’t the way of a market economy.

(H36)

Similarly, voluntary, environmentally friendly individual choices were favoured over higher income taxation. However, the specific product tax was found a suitable measure in the prevailing economic system: ‘It [price instrument] is a pretty valid method in a market economy’ (H29).

Sharing living space was considered suitable for those who are similar in terms of their values, interest and way of life, thus reflecting the importance of having trust in the cooperation of others to increase the acceptability of SPMs. For example, so-called ‘eco-enthusiastics’ (H1) or ‘eco hippies’ (H38) were mentioned. Differences between people, e.g. in their styles on housekeeping, were believed to complicate sharing and create conflicts. When some considered the ability to share space as an innate, unchanging characteristic, others emphasised habituation:

I think it is a question of what you are used to. And then, also, that you can keep a certain amount of your own space, so your peace and quiet is respected, and you have your own space when you need it, well, then beyond that I am sure people would learn quite easily to socialize [and share].

(H1)

However, the bureaucracy of designing and constructing shared apartments was considered laborious and expensive, thus hindering their appeal. For example, the tax authorities were seen as an obstacle for self-organising living situations:

What comes to mind is that when relatives make some kind of mutual arrangement, exchange apartments without actually selling, then the tax authorities tend to intervene. It is somehow completely unfair.

(H35)

The arguments in favour of restricting the size of apartments considered it to be a just policy instrument and they reflected a positive orientation towards top-down regulation, in other words, trust in the intentions of government, whereas the arguments opposing the measure found it too controlling: ‘The state has an unnecessarily big role in defining how you are allowed to live’ (H6).

5.2.5 Socio-demographic factors

Households expressed two main socio-demographic factors that influence their policy acceptability: place of residence and life situation. In urban areas, sharing living space was regarded as sensible, due to a lack of free land area, the proximity of services and an abundance of apartment buildings, in which sharing spaces was considered practical and easily organised by a condo. In contrast, long distances and the popularity of detached houses made sharing spaces in rural areas seem less appealing. The specific product tax was also regarded as unsuitable in rural areas because people who live in the countryside are dependent on their vehicles and thus taxing fuel was considered inadvisable. In addition, restricting the size of apartments was considered unsuitable for rural areas due to the unavailability of small apartments in the countryside (H4). The measure was considered unnecessary in Finland because, first, ‘Finns live in quite cramped conditions compared to many other countries’ (H18), and second, Finland was considered to be a spacious country with enough room for everyone to live as they please:

Yes, I think that if you have the opportunity, then you can put up any kind of castle you want. It isn’t taking anything away from anyone else, after all. Especially in such a sparsely populated country.

(H23)

The participants argued that the suitability of sufficiency measures differs according to one’s life situation. The arguments of the households that were not clearly for or against the joint use of space emphasised that sharing living space was not possible for them right now, but it would be an option when in another stage of life. The benefits of sharing living space included monetary savings and a sense of community, which would enable sharing chores and reduce loneliness, and thus improve mental health. Hence, it was argued to be a valid option especially for young students, the elderly, the unemployed and single-person households. Sharing living space was perceived as unsuitable for families with children since it was considered too hectic and the requirement for living space would be too large. However, some argued that sharing living space with other families would improve social relationships and offer a possibility for help with childcare. Some also stated that sharing living space is not for the elderly because they have ‘earned their peace’ (H9) and ‘people tend to become more and more stubborn with age’ (H32).

Improved human wellbeing from having more time for rest and hobbies were listed as the main benefits of the trading working hours for free time. The measure was considered suitable especially for people whose job is to ‘sell useless things’ (H2) and for those who are nearing retirement and have enough wealth to sustain themselves. On the one hand, trading working hours for free time was considered especially suitable and beneficial for parents of small children. On the other hand, it was considered problematic, since the monthly expenses of families with children are often high:

Well, maybe one has built a kind of trap for oneself, since there is this consumption structure around you, so you can’t really reduce it an awful lot.

(H13)

Higher income tax was the only disabling measure clearly associated with a certain stage of life, such as people who have become wealthy over their life course and could manage higher taxes:

At this stage of life, when the kids have become independent and one is still working, and then one is at the end of one’s career and making a fairly good income, after all.

(H19)

Of all the participants, students, young people and lower income people (all groups that partially overlap in the data) opposed the proposed measures less frequently—even the disabling ones—which could suggest that their life situation would allow them to adapt to the suggested changes.

6. Discussion and conclusions

This paper studied the acceptability of seven sufficiency policy measures (SPMs) regarding energy consumption among Finnish households. The proposed measures were found mainly acceptable under certain conditions. The results are thus in line with previous studies (e.g. Lage et al. 2023; Jenny et al. 2024) by indicating that the acceptability of the SPMs among households may be higher than what might be expected based on studies with, for example, the elite (Ahvenharju 2020).

The households justified their positions towards the SPMs by referring to similar factors found to impact the acceptability of policy measures in earlier studies (see Section 3). Alignment with policy goals, the type and qualities of individual policies, and the attitudes and worldviews of the participants were all identified from the interview data. As a general finding, it was clear that the participants were obviously unaccustomed to think of or discuss sufficiency policies. Their level of awareness regarding energy prices and basic energy-saving measures was generally high, but their understanding of the systemic problem was quite narrow. For example, the feasibility of disabling measures was questioned if the current situation was not considered as an acute environmental crisis. Furthermore, the reasoning behind some of these policies was unclear to many, e.g. the link between high incomes and high energy consumption/environmental impact. One of the most favoured SPMs, the report on electricity consumption, might be widely accepted because it would likely be effective in reducing electricity consumption (Henry et al. 2019). However, the energy reduction potential of the disabling policies was not mentioned, which could suggest that people are not used to thinking about the impact these type of policy measures could have on the carbon footprint of energy consumption. Furthermore, the participants referred to the expectations set by the norms of Western culture, such as a high level of comfort, and expressed being ‘stuck’ in their consumption habits, which has also been noted in earlier studies (Lehner et al. 2024).

The restrictions posed by the disabling SPMs were easily referred to as belonging to totalitarian regimes and they seemed to be unacceptable under any conditions. This is puzzling in a Nordic welfare society which has many widely accepted strict regulations, hence one would expect there to be more refined and nuanced argumentation. A potential explanation is that both least liked policies (higher income tax and restrictions to the size of apartments) target private property and ownership, which are highly valued in Finnish society (Kuusela 2024). Sufficiency, in contrast, tends to emphasise the sharing of resources and a recognition of a minimum and maximum consumption of resources.

Whereas the discussion on efficiency in the field of building and planning often seems unpolitical and technocratic, sufficiency seems to benefit people in different situations differently. Socio-demographic factors did explain the acceptability of SPMs to a certain degree. The place of residence and life situation—often linked with one’s age, which has previously been shown to impact acceptability (Jenny et al. 2024)—impacted the acceptability of SPMs in terms of their reasonability and fairness. Similarly to Ruokamo et al. (2024), the households considered sharing space more appropriate for people living in urban areas. Reducing consumption to a sufficient level was probably considered more achievable for students, young people and lower income people since their consumption is already closer to the minimum and they would probably benefit from the measures the most.

The study has limitations. First, the households participating in the study were likely to be more aware of their energy usage than an average Finn because most of them had already taken part in the energy survey (Numminen et al. 2023). However, this probably eased the shift from mundane energy consumption to more challenging themes during the interview.

Second, the timing of the interviews most likely impacted the research outcomes. Since the ongoing energy crises kept energy consumption in the public discussion and increased general interest in mundane energy use in Finland (Motiva 2023), the participants were likely more aware of their energy consumption than they had previously been. It is thus possible that the opinions of the households would have been different if the interviews were conducted when the acute crises had passed.

Third, the background information gathered about the participants has its weaknesses, e.g. information about the dwellings’ ownership could have been used to further examine the household’s wealth and its impact on policy acceptability.

Fourth, if the interview questions were formulated in another way, the research results could have been different. A rather short description of the measures was given during the interview, which might have impacted their acceptance. In addition, the terms ‘enabling’, ‘informative’ and ‘disabling’ were used when presenting the third group of SPMs to households. This wording likely made the measures in the latter category seem less appealing, and vice versa; however, it did not impact the popularity of specific resource taxes. The desirability bias might have increased the acceptance of some measures, but not all of them since, for example, the disabling ones were generally met with resistance. Furthermore, concerning higher income taxes, it was not clarified clearly to the participants that it should be targeted at high-income earners, not low-income earners. Giving examples of targeted income levels could have made a difference to the results. Finally, the alternative selection of SPMs would most likely result in different responses by households. For instance, in addition to floor area, the demand for space heating is impacted by indoor temperature, which was not included in the SPMs chosen for this study.

Despite its limitations, this study is a promising exploratory endeavour in the field of energy sufficiency. It shows that it is important to normalise sufficiency thinking and to offer alternatives for the ever-growing need for space, for instance. In terms of work-time reductions, mentions of basic income by some households offered some indication of having a macro-level alternative to the prevailing economic system. In addition, there should be more discussion of policy alternatives, more attention paid to the root causes of environmental impacts and more emphasis on avoidance in terms of the consumption changes that sufficiency entails.

Future research could explore the willingness of civil society to engage with sufficiency in voluntary ways and a possibility to choose which SPMs to participate in. This raises the question if individual or household-level CO2 quotas would be found more acceptable. Although a body of research already exists, attitudes and perceptions may be changing. Another direction for further study would be to consider ways to increase public awareness regarding the connection between high income levels and high environmental impact (Koch et al. 2024). Finally, this study shows that the variation between opinions regarding different SPMs is notable, and hence more research is needed on various context- and perhaps even target-specific alternatives as well as altogether new innovations for policy measures.

This study found that the motivations and worldviews of participants generally aligned the goals of SPMs; however, the acceptability of the most restrictive policies was low. Strict external restrictions were found unacceptable under most circumstances: households prefer to keep the final choice of where and how to set limitations to themselves. SPMs that focused on increasing the possibilities to make choices according to sufficiency goals were generally accepted and supported. More innovative policies would be beneficial to simultaneously set limits and leave freedom for choice to households.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the referees for their valuable comments; and the supervisors of the first author, Senja Laakso and Eva-Karin Heiskanen, for reviewing the text.

Author contributions

E.N.: conceptualisation; methodology; investigation; data curation; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing; visualisation; project administration; funding acquisition. S.A.s: conceptualisation; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing; visualisation.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Data accessibility

The data protection statement provided to respondents prohibits publicly disclosing the data.

Ethical approval

An informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from participants prior to the interviews and the identity of the research subjects was anonymised. The research fully adheres to the guidelines of ethical research by TENK, the Finnish board of scientific integrity and ethics.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at: https://doi.org/10.5334/bc.573.s1