Cancer-related hypercalcemia is a common occurrence in patients with advanced cancer, affecting approximately 20–30% of individuals.[1] This condition, known as hypercalcemia of malignancy, refers to elevated calcium levels in the bloodstream beyond the normal range.[2–4] Unfortunately, hypercalcemia of malignancy is associated with a poor prognosis in cancer patients.[1]

Among hospitalized patients, malignancy-related hypercalcemia is the most prevalent cause, affecting both those with solid tumors and hematologic malignancies.[1] Various types of cancer are commonly associated with hypercalcemia of malignancy, including breast, multiple myeloma, squamous cell carcinomas, lung, renal, and ovarian cancer, and certain lymphomas.[2]

Symptoms of hypercalcemia can range in severity from mild to potentially life-threatening.[1] These symptoms include fatigue, constipation, increased urine output (polyuria), and excessive thirst (polydipsia). Typically, mild-to-moderate hypercalcemia is observed during the early stages.[5] However, as the condition progresses, more serious complications may arise, such as cognitive dysfunction, kidney failure, and abnormal heart rhythms (arrhythmias). These severe manifestations often occur when calcium levels rise rapidly or when severe hypercalcemia is present.[5]

The pathophysiology underlying the hypercalcemic crisis involves several mechanisms.[6] First, there can be the production of parathyroid hormone (PTH)- related peptides. They bind to the same receptors as PTH, stimulate osteoclasts, and release calcium into the bloodstream. In addition, bone metastases can release factors that activate osteoclasts, leading to bone resorption and subsequent calcium release. Finally, an excessive production of calcitriol, the active form of Vitamin D, can occur, enhancing intestinal calcium absorption and further contributing to elevated calcium levels.[6]

Hypercalcemia treatment options include IV hydration, calcitonin, bisphosphonates, denosumab, gallium nitrate, prednisone, and hemodialysis.[7] IV hydration helps increase urine production and excretion of excess calcium.[8] Calcitonin inhibits bone resorption,[9–11] while bisphosphonates reduce calcium release from bones and block osteoclastic activity.[12,13] Denosumab targets osteoclast activity,[14,15] and gallium nitrate directly interferes with bone resorption.[16,17] Glucocorticoids such as prednisone inhibit calcium release and promote renal excretion.[18,19] In severe cases, hemodialysis may be used.[20,21] Treatment choice depends on factors such as severity and underlying causes.

Considering the limited number of studies examining the influence of cancer treatment on the prognosis of patients with hypercalcemia,[22–25] our objective was to assess survival outcomes in individuals with malignancy-related hypercalcemia.

The Institutional Review Board of Shaukat Khanum Memorial and Cancer Hospital and Research Centre, Pakistan, approved this retrospective study (#EX-19-05-20-04) and granted the waiver for informed consent, which follows the Declaration of Helsinki.

This retrospective analysis included patients who presented at Shaukat Khanum Memorial and Cancer Hospital and Research Centre, Lahore, between July 2019 and June 2020 with hypercalcemia. The study focused on patients whose hypercalcemia was attributed to an underlying malignancy and identified by the hospital information system (HIS) medical record.

To be included in the analysis, patients had to meet the following criteria: Be above 18 years of age, have biopsy-proven solid or hematological malignancies, and have elevated levels of corrected calcium >10.5 mg/dL (normal range 8.5–10.5), total calcium >10.5 mg/dL (normal range 8.8–10.2), or ionized calcium is >5.5 mg/dL or 1.4 mmol/L (normal range 1.15–1.35) with low or normal levels of PTH. Patients with hypercalcemia unrelated to malignancy, such as those with primary hyperparathyroidism, sarcoidosis, or chronic kidney disease with a glomerular filtration rate <30 mL/min/1.73 m2 before the onset of hypercalcemia, were excluded from the study. The final data analysis was conducted on 173 patients [Table 1]. This cohort of patients was subjected to a longitudinal follow-up for 2.5 years, culminating on December 15, 2022. Data regarding patients’ clinicopathological and radiological parameters were retrieved from the HIS medical records. The acquisition of patient data adhered to applicable data protection and privacy regulations.

Flowchart of malignancy-related hypercalcemia patients admissions at SKMCH&RC (July 2019 to June 2020)

| Category | Count |

|---|---|

| Total patients presented with hypercalcemia from July 2019 to June 2020 | 298 |

| Excluded patients (other causes) | 81 |

| - Primary hyperparathyroidism | |

| - Multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome | |

| - Chronic kidney disease with GFR < 30 ml/min/1.73 m2 | |

| Admitted with symptomatic malignancy-related hypercalcemia | 217 |

| Lost to follow up among malignancy-related hypercalcemia | 44 |

| Followed till 15th Dec 2022 | 173 |

| - Died | 150 |

| - Alive till last follow up | 23 |

We categorized the severity of hypercalcemia into three categories. Mild hypercalcemia was identified when total calcium ranged from 10.5 to 11.9 mg/dL or corrected calcium ranged from 10.5 to 11.9 mg/dL or ionized calcium ranged from 5.6 to 8 mg/dL or 1.4 to 2 mmol/L. Similarly, moderate hypercalcemia had target ranges of total calcium 12–13.9 mg/dL or corrected calcium 12–13.9 mg/dL or ionized calcium 8–10 mg/dL or 2–2.5 mmol/L. Severe hypercalcemia occurs when total calcium is more than 14 mg/dL or corrected calcium is 14 mg/dL or ionized calcium is more than 10 mg/dL or 2.5 mmol/L. The laboratory variables for the patients were determined using identical kits, as illustrated in Table 2.

Demographics and clinicopathological characteristics of the patients included in the study

| Demographics | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 78 (45.1) |

| Female | 95 (54.9) |

| Median Age, years (Range) | 54 (22–95) |

| Histology | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 49 (28.3) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 13 (7.5) |

| Lobular/ductal invasive | 59 (34.1) |

| Lymphoma | 16 (9.2) |

| Multiple myeloma | 8 (4.6) |

| Others | 28 (16.2) |

| Primary site of malignancy | |

| Head and neck | 21 (12.1) |

| Lung | 14 (8.1) |

| Breast | 61 (35.3) |

| Gastrointestinal | 18 (10.4) |

| Hematology | 23 (13.3) |

| Others | 36 (20.8) |

| ECOG PS | |

| 1 | 11 (6.4) |

| 2 | 50 (28.9) |

| 3 | 63 (36.4) |

| 4 | 49 (28.3) |

| Bone metastasis | |

| Yes | 122 (70.5) |

| No | 51 (29.5) |

| Type of bone metastasis | |

| Vertebral and non-vertebral metastasis | 77 (44.5) |

| Vertebral | 25 (14.5) |

| Non-vertebral | 20 (11.6) |

| None | 51 (29.5) |

| Symptoms | |

| Altered mental State | 67 (38.7) |

| Bony aches | 77 (44.5) |

| Constipation | 5 (2.9) |

| Fatigue | 24 (13.9) |

| Liver metastasis | |

| Yes | 66 (38.2) |

| No | 107 (61.8) |

| Severity of hypercalcemia | |

| Mild | 106 (61.3) |

| Moderate | 41 (23.7) |

| Severe | 28 (15.0) |

| Type of malignancy | |

| Solid | 148 (85.5) |

| Hematological | 23 (13.3) |

| Laboratory variables | Median (Range) |

|---|---|

| Hemoglobin, (12–15 g/dL) | 10.5 (0–16) |

| C-reactive protein, (<5 mg/L) | 9 (0–481) |

| Albumin, (3.5–5.2 g/dL) | 3.11 (0–5.06) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.22 (0–44.9) |

| GFR, (>60 mL/min/73 m2) | 70.2 (0.46–984) |

| TLC, (4–10×103/uL) | 10.88 (0.73–99) |

| Platelet, (150–450×103/uL) | 274 (0–681) |

| Creatinine, (0.50–0.90 mg/dL) | 0.88 (0–211) |

| Alkaline phosphatase, (35–104 u/L) | 139.77 (36.29–2953) |

| Magnesium, (1.6–2.4 mg/dL) | 1.78 (0–296) |

| Sodium, (136–145 mmol/L) | 136 (0–174) |

| Potassium, (3.5–5.5 mmol/L) | 4.38 (2.57–145) |

| Parathyroid hormone, (18.5–88 pg/mL) | 8.1 (4.6–86) |

| Vitamin D, (40–100 ng/mL) | 19.1 (8.7–73.5) |

| Phosphate levels, (2.5–4.5 mg/dL) | 3.4 (1.6–8.4) |

| Hypercalcemia | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| MILD: (total calcium 10.5–11.9 mg/dL or Corrected calcium 10.5–11.9 mg/dL or ionized Calcium 5.6–8 mg/dL or 1.4–2 mmol/L) | 106 (61.3) |

| MODERATE: (total calcium 12–13.9 mg/dL or Corrected calcium 12–13.9 mg/dL or ionized Calcium 8–10 mg/dL or 2–2.5 mmol/L) | 41 (23.7) |

| SEVERE: (total calcium >14 mg/dL or Corrected calcium >14 mg/dL or ionized Calcium >10 mg/dL or >2.5 mmol/L) | 26 (15) |

ECOG PS: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, BMI: Body mass index, GFR: Glomerular filtration rate, TLC: Total leukocyte count

In this study, the overall survival (OS) was defined as the time interval from the first episode of hypercalcemia until death. Individuals who were still alive were followed until December 15, 2022. Survival factor refers to any variable or characteristic that has a significant impact on the survival outcomes of cancer patients with hypercalcemia.

Statistical analysis was done using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Mean and standard deviation or median and range were presented for quantitative/continuous variables. Frequency and percentages were reported for qualitative/categorical variables. Survival curves were generated using the Kaplan-Meier tool to estimate the probability of survival over time. The survival difference between different factors was assessed using the log-rank test. Variables that yielded a P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant and were associated with worse outcomes.

Table 2 presents the characteristics of the patients included in the study. The majority of the patients were female, accounting for 54.9% of the total sample, with a median age of 54 years. The most common histological subtype observed was lobular/ductal invasive carcinoma, representing 34.1% of the cases, followed by squamous cell carcinoma, which was found in 28.3% of the patients.

In terms of the primary tumor sites, breast cancer was the most frequently observed, accounting for 35.3% of the cases. Hematological malignancies accounted for 13.3% of the cases, and head and neck cancers were identified in 12.1% of the patients. The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG PS) was evaluated to assess the patient’s overall health and functional status at admission with hypercalcemia. A vast majority of the patients, 93.6%, had an ECOG PS score > 1, indicating a significant impact of the disease on their daily activities. Patients presenting with ECOG PS 1 accounted for 6.4%, those with ECOG PS 2 constituted 28.9%, while individuals with ECOG PS 3 and 4 comprised 36.4% and 28.3%, respectively, at the time of admission.

Bone metastasis was prevalent in the study cohort [Figure 1], observed in 122 (70.5%) patients. Among these patients, 77 (44.5%) had both vertebral and non-vertebral metastasis, whereas 25 (14.5 %) had only vertebral metastasis and 20 (11.6%) had non-vertebral metastasis.

Radiological representative images of bone metastasis: Images of a 50-year-old female patient of breast cancer with extensive axial skeleton osseous metastasis. Magnetic resonance imaging whole spine (a) T2 weighted, (b) T1 weighted, (c) contrast-enhanced mid-sagittal slices, (d) computed tomography scan mid-sagittal slice, bone window settings, and (e and f) Bone scan, anterior and posterior planer images. Blue arrows are sites of axial skeleton osseous metastasis.

The most common presenting symptom of malignancy-related hypercalcemia was bony aches, reported by 77 patients (44.5%). The altered mental state was also a significant presenting symptom observed in 66 patients (38.7%). Furthermore, the prevalence of hypercalcemia was found to be higher in patients with solid malignancies, with 85.5% of these patients experiencing elevated levels of calcium in their blood. This finding suggests a higher propensity for hypercalcemia in patients with solid tumors than other malignancies. Almost 61.3% of patients were admitted with mild hypercalcemia, whereas 23.7% had moderate and 15% had severe hypercalcemia of malignancy at the time of admission. In addition, Table 2 provides the reference ranges for the remaining laboratory variables.

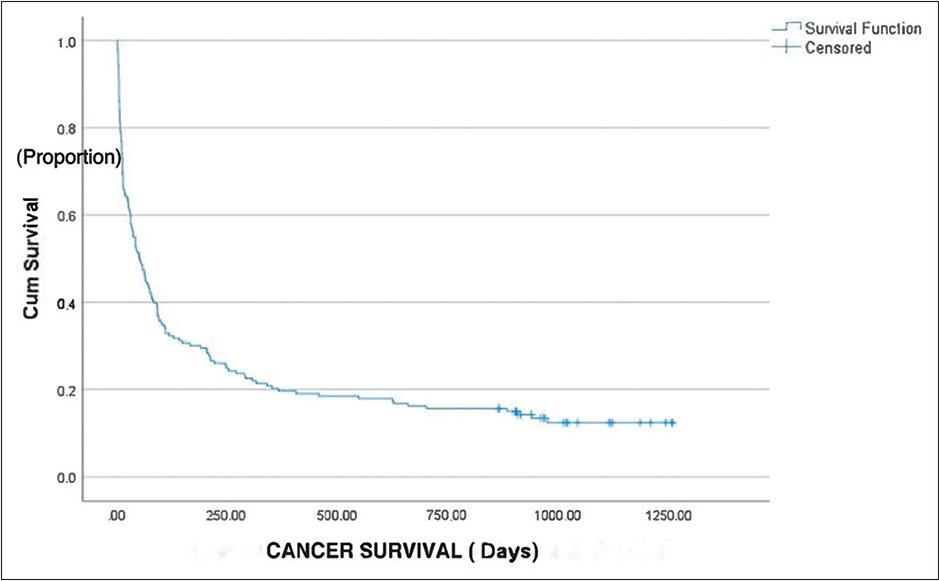

We conducted a follow-up of the patients until December 15, 2022. Among the initial 173 patients included in the study, a significant majority of 150 patients (86.7%) died. In comparison, only 23 patients (13.3%) remained alive until the last follow-up, as depicted in Table 3. The data revealed that a substantial proportion of patients, 39.9%, passed away within the first 30 days of presentation, followed by 12.7% in the 2nd month and 8.7% in the 3rd month. In addition, 25.4% of patients experienced mortality beyond 3 months from their initial presentation. The median OS for the patients was found to be 51 days, indicating that approximately half of the total patients passed away within 51 days of hypercalcemia presentation, with a range of 31–70 days, as shown in Figure 2. These findings highlight that hypercalcemia in cancer patients is associated with survival outcomes.

The median overall survival (OS) for the patients was found to be 51 days. X-axis: Cancer survival days. Y-axis: Cumulative survival proportion. The median OS curve represents the relationship between the onset of hypercalcemia and the proportion of patients who survive beyond that time. X-axis represents the time (number of days) from the onset of hypercalcemia till death. Y-axis represents the cumulative proportion of patients who survive beyond a certain time point. Curve starts at 1 (100 %) on Y-axis indicating that all patients are alive at the beginning of the study. As time progresses, the curve descends gradually, reflecting the decrease in the proportion of patients surviving as time goes on. Median OS represents the time at which 50 % of patients have survived beyond. Median OS was 51 days (95% confidence interval 31–70 days)

Survival outcome of the patients included in this study

| Status | Number (Percentage) |

|---|---|

| Dead | 150 (86.7) |

| Alive | 23 (13.3) |

| Death within days | Number (Percentage) |

|---|---|

| Within 30 days | 69 (39.9) |

| 30–60 days | 22 (12.7) |

| 60–90 days | 15 (8.7) |

| >90 days | 44 (25.4) |

Only 23 (13.3%) remained alive till the last follow-up

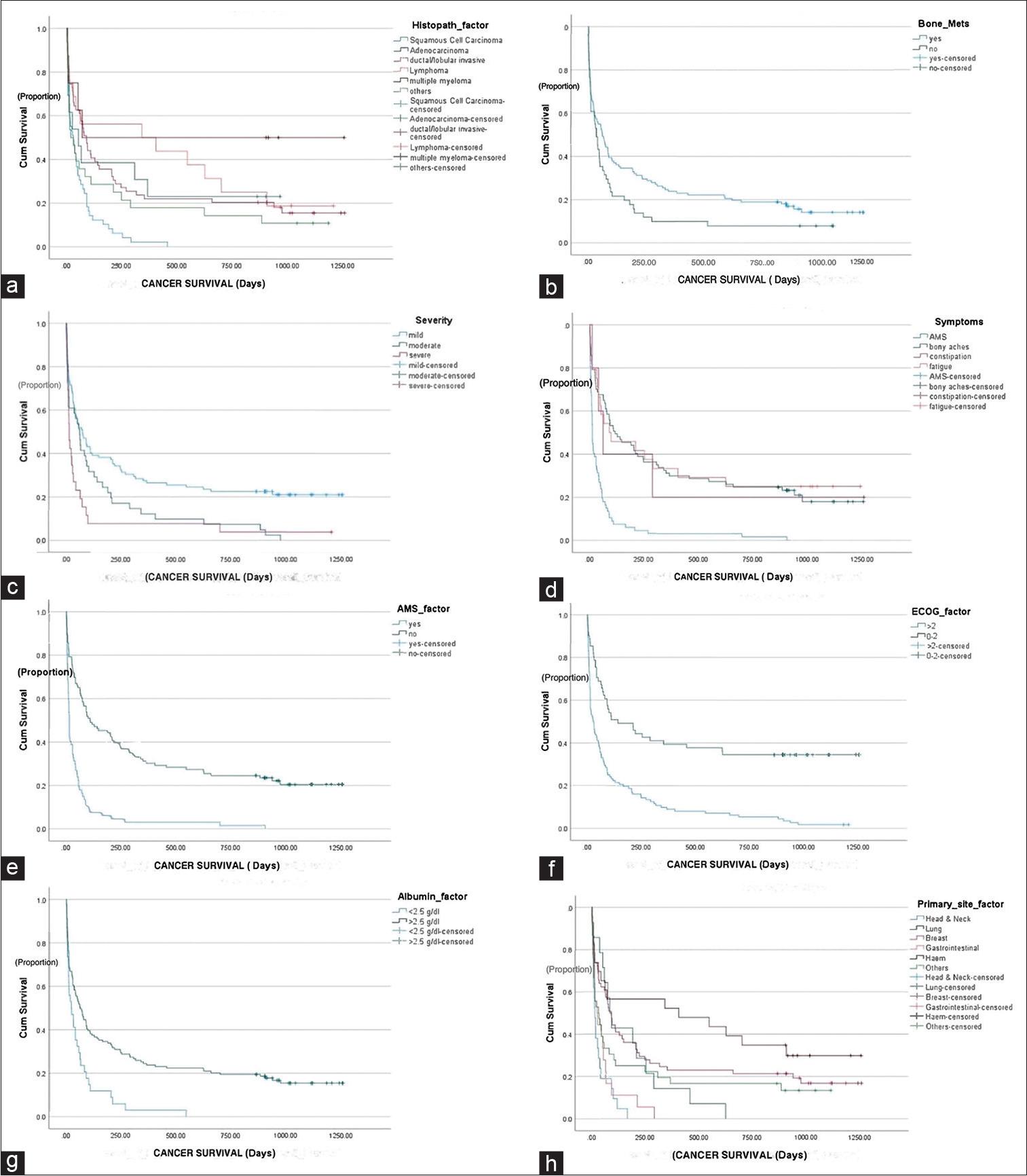

We investigated several factors such as histopathology, the presence of bone metastasis, the severity of hypercalcemia, symptoms of hypercalcemia, altered mental state, ECOG performance status, albumin levels, the primary site of malignancy, presence of hepatic metastasis, type of malignancy (solid or hematological), and site of bony metastasis, as presented in Table 4. The P-values for the examined variables, such as ECOG, altered mental state, albumin, primary site, severity, histopathology, bone metastasis, and symptoms, all were below the 0.05 threshold. This indicates a statistically significant survival difference associated with these factors. In addition, variables featuring more than two categories possess clinical significance. However, it is essential to note that the statistical significance applies to the variables and not necessarily among their individual categories.

Relationship between various factors and survival outcomes was investigated

| Factor | Median OS, days (range) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| ECOG | <0.001 | |

| >2 | 25 (8.5–41.4) | |

| ≤2 | 140 (2.2–277.7) | |

| Altered mental state | <0.001 | |

| Yes | 13 (10.3–15.6) | |

| No | 108 (24.7–191.24) | |

| C-reactive protein | 0.06 | |

| >30 | 30 (0.00–67.9) | |

| <30 | 245 (193.8–296.1) | |

| Albumin | <0.001 | |

| <2.5 | 23 (0.0–50.1) | |

| >2.5 | 64 (37.0–90.9) | |

| BMI | 0.75 | |

| <18 | 36 (33.0–38.9) | |

| >18 | 52 (30.6–73.3) | |

| Primary site of malignancy | <0.001 | |

| Head and neck | 13 (4.0–21.9) | |

| Lung | 82 (48.9–115.0) | |

| Breast | 89 (63.8–114.1) | |

| Gastrointestinal | 23 (0.1–45.8) | |

| Hematological | 405 (0–1151.5) | |

| Others | 30 (0–63.8) | |

| Severity of hypercalcemia | <0.001 | |

| Mild | 73 (38.3–107.6) | |

| Moderate | 61 (32.1–89.8) | |

| Severe | 13 (6.7–19.2) | |

| Type of malignancy | 0.31 | |

| Solid | 43 (19.1–66.8) | |

| Hematological | 405 (0–1151.5) | |

| Histopathology | <0.001 | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 30 (5.3–54.6) | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 52 (0–116.5) | |

| Ductal/lobular invasive | 89 (64.2–113.7) | |

| Lymphoma | 334 (0–1013.2) | |

| Multiple myeloma | 69 (0–0) | |

| Others | 18 (0–47.8) | |

| Bone metastasis | 0.045 | |

| Yes | 63 (33.6–92.3) | |

| No | 36 (23.7–48.2) | |

| Types of bone metastasis | 0.21 | |

| Both | 76 (48.9–103) | |

| Vertebral | 26 (5.6–46.3) | |

| Non-vertebral | 51 (0–108.9) | |

| None | 36 (24.3–47.6) | |

| Symptoms | <0.001 | |

| Altered mental state | 13 (9.0–16.9) | |

| Bony aches | 117 (23.3–210.6) | |

| Constipation | 62 (16.9–107) | |

| Fatigue | 91 (15.9–166) | |

| Liver metastasis | 0.102 | |

| Yes | 41 (13.1–68.8) | |

| No | 61 (28.7–93.2) |

ECOG PS: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, Median OS: Median overall survival, BMI: Body mass index. A P-value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant, Bold values represent statistically significant results.

To evaluate the impact of specific factors on patient survival, cutoff values were established for certain variables, such as ECOG > 2, C-reactive protein (CRP) > 30 mg/dL, albumin < 2.5 g/dL, and body mass index (BMI) < 18 kg/m2. Analysis revealed that patients with squamous cell carcinoma had a median OS of 30 days. In contrast, lymphoma exhibited the highest median OS of 334 days, as depicted in Figure 3a. A notable disparity was observed among patients with bony metastasis, with a better median OS [Figure 3b]. Among patients admitted with severe hypercalcemia, the median OS was only 13 days, which increased to 61 days for moderate hypercalcemia cases and 73 days for mild hypercalcemia cases [Figure 3c]. In addition, patients exhibiting an altered mental state demonstrated a significantly reduced median OS of 13 days. Furthermore, it was identified as an independent and unfavorable factor, irrespective of the severity of hypercalcemia. In contrast, patients presenting with constipation (62 days), fatigue (91 days), or bony aches (117 days) demonstrated relatively better median OS [Figure 3d and e]. Notably, cardiac complications were not observed in this cohort. Patients with an ECOG performance status >2 at admission had an overall median survival of only 25 days (range: 8.5–41.4 days), while those with an ECOG performance status <2 exhibited a median OS of 140 days [Figure 3f]. Furthermore, malnourished patients with albumin levels below 2.5 g/dL had a median OS of 23 days, which improved to 64 days for patients with albumin levels above 2.5 g/dL at admission [Figure 3g]. Among the different malignancies examined, there were notable variations in median OS. Head and neck malignancies had the lowest median OS, with only 13 days, while gastrointestinal malignancies demonstrated a slightly longer median OS of 23 days. Conversely, hematological malignancies exhibited a significantly better survival, with a more favorable median OS of 405 days, as illustrated in Figure 3h.

Impact of various factors on overall survival (OS) was determined: (a) Delineated significant variance in OS across distinct histopathologies (P < 0.001). Squamous cell carcinoma exhibited better long-term survival compared to adenocarcinoma, ductal/lobular invasive, lymphoma, multiple myeloma, and others. In (b), the illustration depicted a notable survival discrepancy between groups based on the presence or absence of bone metastasis (P < 0.04). (c) Elucidated the gradation of hypercalcemia severity (mild, moderate, and severe) with superior OS observed in patients with mild hypercalcemia (P < 0.001). (d) Clarified OS differences among various reported symptoms (P < 0.001). (e) Illustrates the contrast in OS based on the presence or absence of altered mental state (AMS) (P < 0.001). In addition, (f) depicted a significant survival discrepancy across different Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) statuses (P < 0.001), with better survival rates observed in patients with ECOG statuses of 0–2 compared to those with statuses below 2. (g and h) demonstrated OS variation between albumin categories (<2.5 vs. >2.5) (P < 0.001) and primary cancer sites (P < 0.001), with marginal survival differences between albumin categories and no disparity observed among primary cancer sites

In contrast to these factors, no significant differences were observed in variables such as CRP levels, BMI, presence of liver metastasis, and type of bone metastasis. These factors did not show substantial associations with variations in median OS.

In this single-center retrospective study, the median OS for the patients was found to be 51 days, indicating that approximately half of the total patients passed away within 51 days of hypercalcemia presentation, with a range of 31–70 days. Among the initial 173 patients included in the study, a significant majority of 150 patients (86.7%) died. In comparison, only 23 patients (13.3%) remained alive until the last follow-up. Our data revealed that a substantial proportion of patients, 39.9%, passed away within the first 30 days of presentation. These findings highlight the significant impact and limited survival rates associated with hypercalcemia, as reported by previous studies.[25–27]

Malignancy-related hypercalcemia is a significant concern due to its prominent role as the leading cause of hypercalcemia and its substantial impact on the prognosis of individuals with cancer.[28] The prognosis of malignancy-related hypercalcemia is influenced by several factors, including the underlying cause and the specific type of cancer.[29] Early-stage diseases generally tend to have a more favorable prognosis. In contrast, advanced stages or delayed diagnosis of hypercalcemia may lead to a poorer prognosis.[29] This condition is observed in approximately 20% of cancer patients as their disease progresses.[30] It can manifest with varying degrees of severity, ranging from mild symptoms to potentially life-threatening manifestations.[28] In this study, we aimed to assess survival outcomes in individuals with malignancy-related hypercalcemia.

Solid tumors were more frequently treated at our hospital than hematological malignancies. Within our dataset, patients with hematological malignancies constituted 13.3%, while those with non-hematological malignancies comprised 85.5%. Interestingly, we noted no significant difference in OS between these two categories.

Our study identified several factors associated with survival outcomes in patients with malignancy-related hypercalcemia. Among our dataset, breast cancer was the most prevalent primary tumor site, accounting for 35.3% of cases, with lobular/ductal invasive carcinoma being the predominant histological subtype at 34.1%. These findings were consistent with a study conducted by Soyfoo et al., where breast cancer was also reported as the most frequent site (29%).[31] However, contrasting results were reported in the European series by Penel et al., which found the head and neck region to be the most frequent primary site.[26,27] The onset of hypercalcemia in cancer patients with well-differentiated neuroendocrine neoplasms poses a significant clinical challenge with a notable tendency for it to go undiagnosed.[32,33] Among its causes, systemic secretion of PTH-related protein and ectopic production of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D and PTH may be considered paraneoplastic causes of hypercalcemia.[33]

Patients with gastroenteropancreatic-neuroendocrine tumors face an elevated risk of osteopenia and osteoporosis due to various factors affecting bone metabolism.[34] In our dataset, we identified only two patients with neuroendocrine tumors. A study conducted by Degardin et al. revealed that performance status significantly impacts patients’ survival.[35] We also identified that patients with an ECOG performance status >2 at admission had an overall median survival of only 25 days. Our results are in compliance with the previously published data by Ramos et al.[25] In addition, hypoalbuminemia was identified as a predictor of poor survival by Penel et al.[26] We also observed that malnourished patients with albumin levels below 2.5 g/dL had a median OS of only 23 days which was less than the median OS identified by Ramos et al.[25]

Patients with an altered mental state, symptoms, and severity experienced shorter median OS in our findings indicating the poor survival outcomes which are in accordance with the previous studies.[25,26] While Penel et al. identified bone metastasis as a factor associated with poor survival,[26] we found that bone metastasis was not linked to worse outcomes. Our findings highlight the importance of considering these factors when assessing survival outcomes in patients with malignancy-related hypercalcemia.

The present study is constrained by certain limitations stemming from its retrospective design. A noteworthy constraint involves the relatively modest sample size employed in this investigation. It is essential to highlight that a majority of the participants in this study exhibited solid malignancies, as opposed to hematological malignancies. We followed the international guidelines for managing malignancy-related hypercalcemia, and the administration of treatments such as zoledronate and pamidronate was carried out based on the discretion of the treating physicians. Unfortunately, specific details regarding the treatment process were not systematically documented, rendering us unable to discern the impact of these medications on the current survival outcomes. Moreover, it is pertinent to emphasize that, to the best of our knowledge; this study stands as a pioneering endeavor in Pakistan. It represents the first comprehensive investigation encompassing both solid tumors and hematologic malignancies in Pakistan.

Malignancy-related hypercalcemia in cancer patients predicts unfavorable survival outcomes. The factors associated with malignancy-related hypercalcemia hold promise for potentially influencing patient survival outcomes. However, further studies involving larger cohorts are imperative to enhance our understanding and confirm these findings due to the need for more comprehensive data and a broader sample size.