Geopolymer concrete (GPC), recognized for its environmentally friendly and long-lasting characteristics, has garnered significant attention in the field of building [1]. The excellent mechanical properties of geopolymer, particularly in harsh environments, are responsible for this [2, 3]. The growing popularity of concrete constructions places a significant burden on the concrete industry, resulting in a higher consumption of cement and aggregate [4, 5]. Furthermore, GPC offers a more environmentally friendly alternative to Ordinary Portland Cement concrete in terms of carbon dioxide equivalent emissions [6, 7]. In light of the environmental issues at hand and the growing need for sustainable and eco-friendly materials, recent studies have suggested using recycled waste materials as complete or partial replacements for natural aggregates, which make up nearly 70% of the concrete volume [8, 9]. Many studies have been carried out to explore the possibility of substituting natural coarse aggregate with reclaimed asphalt pavement (RAP) aggregate in traditional cement concrete mixtures [10, 11]. RAP mostly comprises asphalt mixtures that have been recovered from existing infrastructure [12]. Additionally, it may include a small amount of discarded or rejected mixtures from the production processes. Annual milling of hot-mix asphalt can reach 100 million tons, as reported by the Federal Highway Administration [13]. As it is made up of one precious nonrenewable resource (i.e., aggregates), it can make construction more sustainable. Although, in 2018, RAP reuse accounted for over 88% of its weight in the United States and 72% of its weight in Europe as aggregates for asphalt mixtures and unbound layers. Nevertheless, numerous countries continue to impose restrictions on the proportion of RAP in recycled asphalt mixtures, typically limiting it to an average of 15–20% by weight [14]. Recycling and reusing removed bituminous mixture exemplifies sustainable growth in the infrastructure industry. The effort to advocate for its use promotes a global trend to address environmental problems by attempting to diminish carbon emissions and make better use of available resources.

By contrast, there are few studies regarding the use of RAP in GPC for structural and non-structural application [15]. Although extensive research is being conducted on the use of GPC as a structural material, there is a noticeable gap in the exploration of the impact of various types and levels of confinement on geopolymer concrete [5]. GPC may be susceptible to fire-induced damage, potentially reducing its structural integrity [15, 16]. The performance of GPC under high temperature conditions compared with traditional concrete is an area that requires further exploration. Investigating the strengthening of heat-damaged GPC is crucial to understanding its behavior and increasing the compression strength of concrete cylinders exposed to heat.

The adoption of fiber-reinforced polymers (FRPs) plays a pivotal role in advancing the structural performance of concrete elements, offering a range of types with distinct properties tailored to various engineering needs [17, 18]. The advantages of FRPs in concrete applications are various [19, 20]. They exhibit high strength-to-weight ratios, enabling efficient structural improvement without significant additional loads. Moreover, FRPs are non-corrosive, which contributes to a longer service life and reduced maintenance costs. The lightweight nature of FRPs simplifies handling during construction, and their versatility allows for tailored solutions to specific engineering challenges [21, 22]. In summary, FRPs represent a diverse and practical toolkit for engineers, offering tailored solutions for reinforcing concrete structures with increased durability, strength, and adaptability to various applications. Carbon-fiber reinforced polymer (CFRP) composites are being widely studied for their capacity to improve the mechanical characteristics and durability of concrete structures. This type of FRP is extensively used in applications in which increased structural performance is crucial, such as in strengthening beams, columns, and bridge components [23, 24].

Carbon fibers can be used in many forms in the GPC matrix. The incorporation of short fibers in manufacturing processes typically does not necessitate substantial modifications, even when long fibers or textiles are used [25]. Textiles, grids, and fabrics that are strengthened with a geopolymer matrix are frequently used to improve mechanical characteristics, particularly at high temperatures [5, 26]. This type of strengthening is utilized by applying one or several layers of two-dimensional or three-dimensional textiles or grids [26, 27]. The primary difficulty in geopolymer strengthening often lies in achieving a suitable bond between the geopolymer and the textile. The bonding is typically the least strong component of the composite, and it is where the failure process initiates [26, 28].

FRPs excel in concrete applications, mainly in confined concrete elements [29]. Confinement refers to the practice of enveloping concrete columns or members with FRP materials, proving exceptionally effective in improving the structural performance of these elements [30, 31]. FRP provides lateral support to the concrete, restricting its expansion under axial loads and conferring numerous benefits. FRP’s inherent high tensile strength, especially in the case of CFRP, plays a pivotal role [8, 32, 33]. As concrete is typically strong in compression but relatively weak in tension, using FRP in confinement addresses this disparity by significantly increasing the tensile strength of the composite system [34]. This results in improved ductility and resistance to cracking, particularly in scenarios involving high axial loads or seismic events. The confinement effect of FRP on concrete also contributes to increased deformability. FRP-wrapped columns exhibit controlled and predictable deformation under loading, allowing them to absorb and dissipate energy during seismic events. This behavior significantly improves the seismic resilience of structures, a critical consideration in regions prone to earthquakes [5, 35]. The lightweight nature of FRP simplifies the installation process and minimizes the additional dead load on the structure, making it an efficient and practical solution for retrofitting existing concrete elements. In addition to its mechanical advantages, using FRP for concrete confinement offers notable corrosion resistance [36]. Unlike traditional steel reinforcement, FRP materials do not rust, contributing to the longevity and durability of the structure. This makes FRP an ideal choice in aggressive environments or marine applications where corrosion poses a significant threat to the integrity of concrete elements.

In recent research endeavors, there has been a growing focus on applying FRP for the confinement of recycled aggregate concrete (RAC) in various geometries, including cylinders, prisms, and cubes [37, 38]. The motivation behind this exploration lies in addressing sustainability challenges by incorporating recycled aggregates into concrete mixtures and concurrently optimizing the mechanical properties of these structures through FRP confinement. The mechanism involves wrapping the RAC specimens with FRP materials, typically CFRP, to improve their mechanical performance [39, 40]. The primary objective of FRP confinement in RAC is to mitigate the inherent drawbacks of using recycled aggregates, such as lower compressive strength and higher porosity [8, 35]. By enveloping RAC specimens with CFRP, researchers aim to improve the concrete’s tensile and shear strength, ductility, and overall durability. The CFRP acts as an external strengthening, providing lateral support to the RAC and increasing its ability to withstand compressive forces [41, 42]. The confinement effect of CFRP on RAC is particularly crucial in the context of cylindrical, prismatic, and cubic specimens, in which the potential for premature failure and reduced performance due to recycled aggregates is more pronounced. The mechanical mechanism involves the interplay between CFRP’s tensile strength and RAC’s compressive strength. The CFRP confines the RAC, preventing lateral expansion and increasing its ability to carry axial loads [43, 44]. This confinement effect results in improved stress distribution, reduced crack propagation, and increased energy absorption capacity [45, 46].

Furthermore, the FRP-confined RAC exhibits increased ductility and strain capacity, critical factors for structural elements subjected to dynamic loading or seismic events. Researchers are exploring various parameters in these studies, including the type and amount of recycled aggregates, FRP’s configuration and wrapping techniques, and the curing conditions to optimize the performance of FRP-confined RAC specimens [47, 48]. The goal is to comprehensively understand these composites’ mechanical behavior and structural performance, thereby contributing to the development of sustainable and durable construction materials [43, 49]. This research addresses environmental concerns by promoting the use of recycled materials and advances the application of FRP in sustainable construction practices. However, the high rigidity of CFRP is accompanied by a significant increase in its production [50]. Although CFRP is an expensive material, large corporations are now looking for innovative ways to manufacture it from sustainable or waste-based materials. Yet, it is critical to use external reinforcement when a rapid strengthening procedure is required that minimizes disruption to the existing structure, particularly after it has been subjected to fire. Furthermore, certain strengthening procedures require an increase in the dimensions of structural elements, emphasizing the advantages of using CFRP, which has minimal thickness. Nevertheless, if the use of CFRP results in a decrease in the need for maintenance and repair, it has the potential to become more costeffective in the long run. Although CFRP’s material cost is disadvantageous, its lightweight nature and easy implementation can result in an overall cost reduction of approximately 17.5% compared with typical steel repairs [51].

Current research efforts primarily focus on investigating FRP confinement in concrete, particularly in waste-containing concrete. Although numerous studies [1, 31, 52] have demonstrated the effectiveness of CFRP composites in repairing damaged concrete structures and restoring the mechanical performance of post-heated reinforced concrete columns [53, 54], there is a lack of studies assessing the use of CFRP composites on heatdamaged GPC cylinders composed of recycled aggregate. This highlights the need for further research into the impact of various types of confinement on the behavior and characteristics of heatdamaged GPC. In addition, RAP mostly comprises asphalt mixtures that have been recovered from existing infrastructure, which can reach 100 million tons annually. Therefore, it is important to use recycled waste materials as partial or complete replacements for natural aggregates, which make up nearly 70% of the concrete volume, addressing environmental concerns and the growing desire for green alternatives. This study aims to explore the effectiveness of strengthening heat-damaged GPC cylinders containing recycled asphalt aggregate using CFRP composites. Different mixtures of E concrete containing different percentages of waste RAP aggregate (0%, 25%, and 50%), were prepared and tested under compression. Some samples were kept as controls, whereas others were exposed to an elevated temperature of 300°C. Both samples before and after exposure to high temperature were confined with CFRP sheets and tested in compression. The stress-strain response, stiffness, and toughness of the strengthened and unstrengthened samples, both heated and unheated, were evaluated and compared.

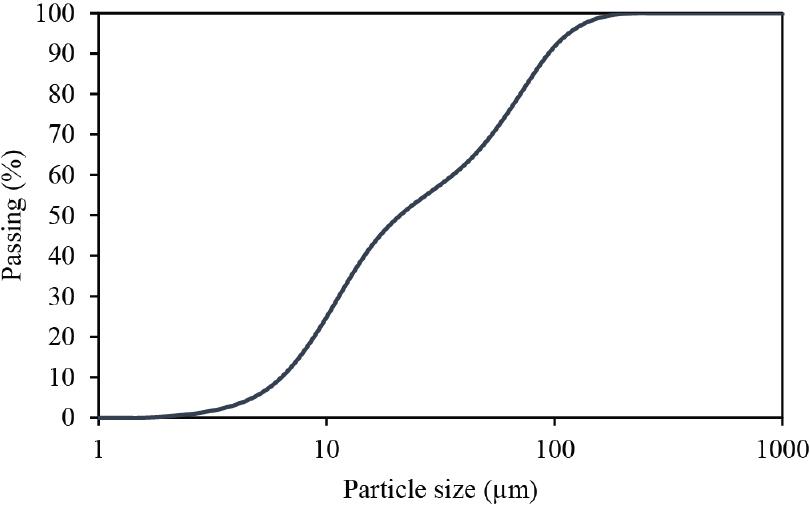

The major component used in the current study was metakaolin (MK), obtained through the process of calcination of locally sourced kaolin. Figure 1 shows the particle size of the MK used in the current study. Table 1 provides the chemical composition of the RAP. The aggregate used in the manufacturing process of the GPC consisted of a combination of fine and coarse aggregates. Two categories of coarse aggregates were used, namely limestone aggregate (conventional aggregate) and RAP aggregate, with a maximum size of 10 mm for both types. The fine aggregate consisted of a combination of crushed limestone aggregate and white sand, with a maximum size of 4.75 mm for both types. The sieve analyses of fine and coarse aggregate are shown in Figure 2. Figure 3 displays samples of the coarse aggregates. The chemical composition of the reclaimed asphalt element compound of RAP was mostly as follows: 48%–38% SiO2, 30%–26.8% Fe2O3, 16.3%–20% CaO, by weight percentage [12]. The geopolymer binder was activated by using a sodium-based activator that consisted of sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and sodium silicate (Na2SiO3) solutions. The sodium hydroxide solution was prepared with a concentration of 14 M 1 day before sample preparation. The Na2SiO3 solution had a silica modulus of 3.3, which is the ratio of SiO2 to Na2O. The CFRP used in this study was produced by Horse Company, a unidirectional carbon fiber fabric used in structural strengthening applications. The epoxy adhesive resin used was Sikadur-300, as per the manufacturer’s recommendation. Sikadur-300 is a resin used for impregnation, consisting of two parts and made from epoxy. The tensile strength of the material was 71.5 MPa and its elastic modulus was 1.86 GPa. Table 2 provides the properties of the CFRP sheet and epoxy adhesive. The tensile strength of the CFRP sheet was evaluated by conducting tests on standard coupons in compliance with the guidelines provided by ASTM D3039 [55].

The MK particle size used in this study

Sieve analysis of the fine and coarse aggregates

Samples of the coarse aggregates used in this study. (a) Limestone aggregate. (b) RAP aggregate

Chemical analysis of MK (% weight)

| Composition | SiO2 | Fe2O3 | Al2O3 | Na2O | CaO | SO3 | TiO2 | K2O | MgO | P2O5 | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value (%) | 50.995 | 2.114 | 42.631 | 0.284 | 1.287 | 0.439 | 1.713 | 0.337 | 0.127 | 0.051 | 0.022 |

Properties of the CFRP sheet and epoxy adhesive

| Material | Property | Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| CFRP sheet | Thickness | 0.6 mm | Experimental values |

| Ultimate tensile strength | 1122 MPa | ||

| Ultimate tensile strain | 1.7% | ||

| Tensile modulus of elasticity | 68.9 GPa | ||

| Epoxy adhesive | Tensile strength | 71.5 MPa | Given by the manufacturer |

| Tensile strain at break | %5.25 | ||

| Tensile modulus of elasticity | 1.86 GPa |

The experimental test program consisted of three concrete mixtures. The first mixture was used as a control mixture (A0) that was made with 100% conventional aggregate (i.e., without RAP). The preparation of the two remaining mixtures involved the substitution of conventional aggregate with RAP aggregate at volumes of 25% and 50%, which were named A25 and A50, respectively. Before mixing, both of the aggregate types (i.e., limestone and RAP) for all the mixtures (A0, A25, and A50) were prepared in a condition in which they were saturated but appeared dry on the surface. Table 3 provides the mixture proportions for different mixtures.

Properties of the CFRP sheet and epoxy adhesive

| Material | A0 mixture | A25 mixture | A50 mixture | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MK | 350 | 350 | 350 | |

| Alkaline solutions | NaOH | 110.04 | 110.04 | 110.04 |

| Na2SiO3 | 196.98 | 196.98 | 196.98 | |

| Water | 5.74 | 5.74 | 5.74 | |

| Fine aggregate | White sand | 419 | 419 | 419 |

| Crushed limestone | 180 | 180 | 180 | |

| Coarse aggregate | Limestone | 1,272 | 954 | 636 |

| RAP | 0 | 334.9 | 669.7 | |

The aggregates for mixtures A0, A25, and A50 were produced under saturated surface dry conditions and subsequently dry mixed with MK for 2 min. The combination of alkaline solutions and water was incorporated into the dry concrete components. The mixing process was continued for a few minutes until the combination achieved homogeneity. Subsequently, molds were filled with concrete slowly to avoid separation, and to prevent the formation of voids, a vibrating table was used. Figure 4 depicts the concrete vibrating while being cast into the molds. The top layer was meticulously leveled using a steel trowel to provide a perfectly even surface. The prepared specimens were subsequently cured for 28 days in the lab at ambient temperature (24°C ± 2°C) and relative humidity (20% ± 2%). The selection of this curing scheme was based on the findings of Alghannam et al. [56]. The experimental test matrix of this study is presented in Table 4. It should be noted that Table 4 uses the abbreviations “A0”, “A25”, and “A50” to refer to various types of mixtures: concrete mixtures without RAP, concrete mixtures with 25% RAP, and concrete mixtures with 50% RAP, respectively. The test cylinders were carried out three times for each of the strengthened, unstrengthened, heated, and unheated specimens to ensure data consistency and increase confidence in the study’s findings. The total number of specimens in this study was 36 concrete cylinders measuring 150 mm in diameter and 300 mm in height. The specimen IDs consisted of numbers and letters. The first string refers to the concrete mixtures that were used. The “R” represents the specimen exposure to 26°C, “300” represents the specimen exposure to 300°C, and “S” represents the strengthened specimens.

Specimen preparation. (a) Cylinders during casting. (b) Cylinders ready for testing

Test matrix

| Group | Concrete mixture | Specimens ID | RAP aggregate | Exposure to temperature | Strengthening | No. of specimens |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group “1” | A0 | A0-R | 0% | 26°C | – | 3 |

| A0-300 | 300° C | 3 | ||||

| A0-S-R | 26°C | CFRP | 3 | |||

| A0-S-300 | 300°C | 3 | ||||

| Group “2” | A25 | A25-R | 25% | 26°C | – | 3 |

| A25-300 | 300°C | 3 | ||||

| A25-S-R | 26°C | CFRP | 3 | |||

| A25-S-300 | 300°C | 3 | ||||

| Group “3” | A50 | A50-R | 50% | 26°C | – | 3 |

| A50-300 | 300°C | 3 | ||||

| A50-S-R | 26°C | CFRP | 3 | |||

| A50-S-300 | 300°C | 3 | ||||

| Total no. of specimens | 36 | |||||

The cylinders that were damaged by heat were strengthened using CFRP sheets with one layer with an overlap of 100 mm. Before implementing the CFRP sheet, the specimens underwent surface roughening using sandblasting. This was carried out to establish a robust bond between the concrete surface and the CFRP sheet. In the initial phase, the specimen surface was meticulously cleaned to eliminate any surface impurities (i.e., dust particles). The next phase involved applying an epoxy primer layer to the concrete’s surface. This was carried out to fill any air voids on the cylinder surface and ensure strong adhesion. Subsequently, a light coating of epoxy was applied to the cylinders. Afterward, the CFRP layer was meticulously wrapped around the concrete cylinders. A roller was employed to eliminate the trapped air between the CFRP sheet and cylinder surfaces, facilitating improved impregnation of the saturant. Stringent measures were implemented to guarantee the absence of any air voids. Figure 5 depicts the specimens strengthened by CFRP sheets.

The specimens strengthened by CFRP sheets

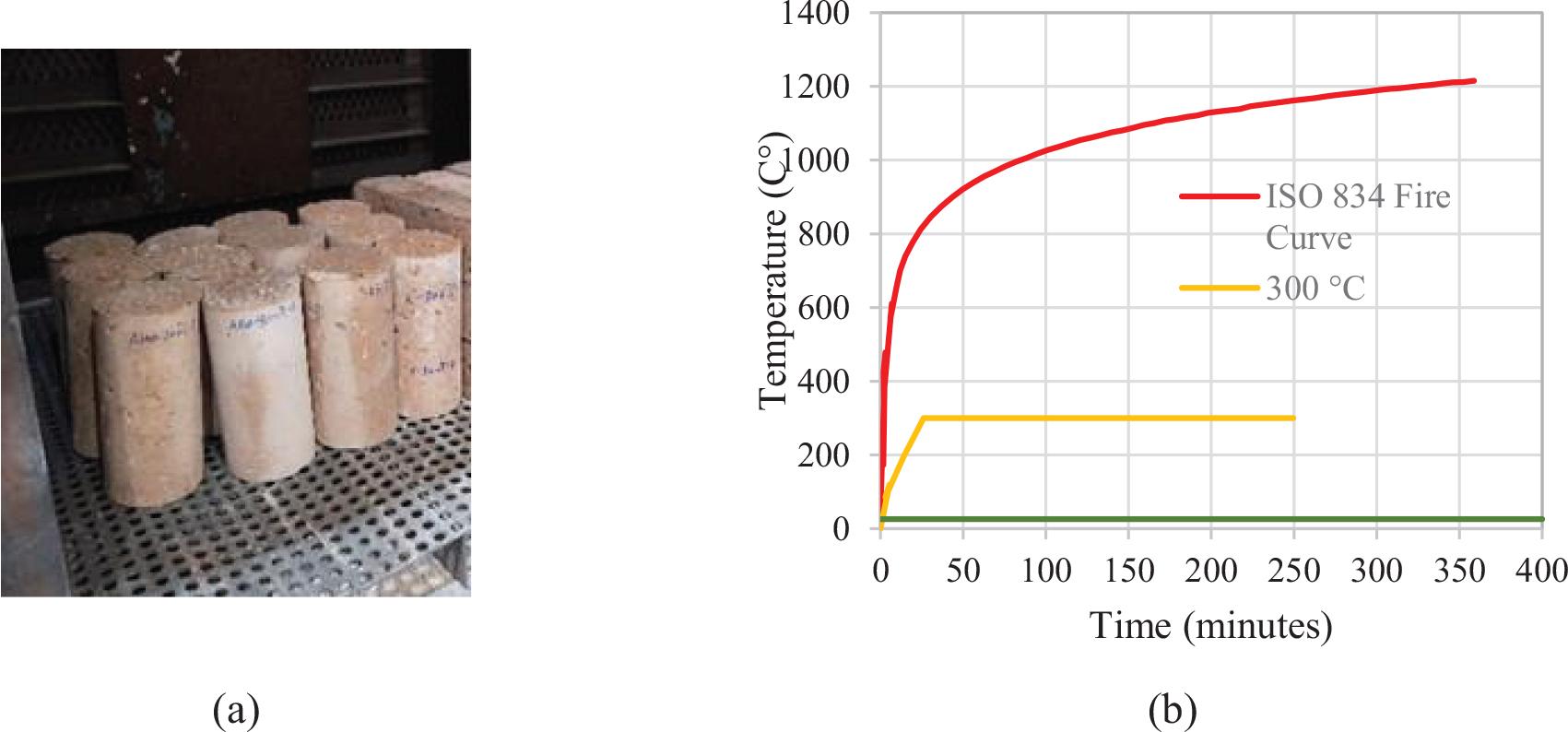

The cylinders were subjected to heating in an electric oven (refer to Fig. 6) to the desired temperature of 300°C. On the day before conducting specimen testing, several specimens were moved from the lab to the oven, as shown Figure 6(a). The specimens in the oven were heated at an increased average rate of 8°C/min until the desired temperature of 300°C. Once the specimens reached 300°C, they were left in the oven for a duration of 3 h before turning off the oven. Subsequently, the specimens were allowed to cool down to the surrounding temperature. Figure 6(b) displays the time-temperature curve used for 300°C temperature exposure compared with the standard curve of ISO 834.

Specimen preparation. (a) Cylinders inside the oven. (b) Time-temperature curves

The cylinders tested in this investigation were exposed to an axial compressive pressure. To achieve full leveling of the specimen during compression testing, the top surface of the specimen was sealed with sulfur. For measuring the axial strain during the test, each specimen was connected to a compressometer, as depicted in Figure 7. The compressometer was equipped with two linear variable differential transformers (LVDTs), which were positioned on two circular sleeves placed around the specimen. To prevent the sleeves from affecting the specimen’s dilation, they were fastened to the specimen using pin-type support. The LVDTs’ wires were connected to a data acquisition system to capture the measurements during the experiment. Every specimen underwent uniaxial compression until it failed. The concrete’s compressive strength was determined using the procedure outlined in ASTM C39 [57].

Test setup

Figure 8 displays the failure patterns of all specimens after undergoing compression testing and heat exposure. In general, the inclusion of RAP aggregate in the mixtures did not significantly affect the ultimate failure mode of the concrete specimens. Both mixtures, with and without RAP aggregate, exhibited fine vertical cracks, as depicted in Figure 8. It should be noted that the pictures in Figure 8 were captured after the test had advanced beyond the point of peak load. The failure mode of the unheated control specimens was depicted from a similar investigation by Albidah [15] for the purpose of comparison. The concrete cylinders displayed more cracks and crushing when subjected to an elevated temperature of 300°C, as shown in Figure 8. Exposure to a temperature of 300°C resulted in thermal cracking on the surface of the concrete cylinders. Generally, the heated specimens emitted a more subdued failure sound but the unheated specimens abruptly failed with a loud failure sound, such as a little explosion sound. The unstrengthened specimens that were exposed to ambient temperatures had brittle failures. Conversely, the unstrengthened specimens showed a decreased tendency toward brittle failure (more ductile) when exposed to high temperatures (300°C). Consequently, there was no sudden failure compared with specimens of the same type that were exposed to ambient temperature. The strengthened specimens exhibited concrete crushing, with CFRP rupture as the mode of failure. The detachment of the CFRP layer from the concrete surface is associated with the CFRP’s ringed rupture, as seen in Figure 8. All strengthened specimens (refer to Fig. 8) exhibited the rupture of the CFRP sheet in the upper portion. The specimens strengthened with a CFRP sheet exhibited failure at the ends (i.e., loading point), followed by subsequent failure at the center of the cylinder. Following the rupture of the CFRP, the bonding strength was inadequate to withstand the hoop tensile stress, which was caused by the radial expansion. As a result, debonding failure occurred simultaneously with the rupture of the CFRP. Furthermore, when subjected to the same temperatures, the strengthened specimens showed increased ductility in comparison with the unstrengthened specimens. Similarly, Albidah [15] observed that the inclusion of RAP aggregate in the GPC mixtures did not have a noticeable impact on the failure patterns of the specimens, which exhibited fine vertical cracks. Moreover, Albidah et al. [58] reported that there were no minor or major cracks observed, even when subjected to increased temperatures reaching up to 600°C.

Failure mode for all specimens

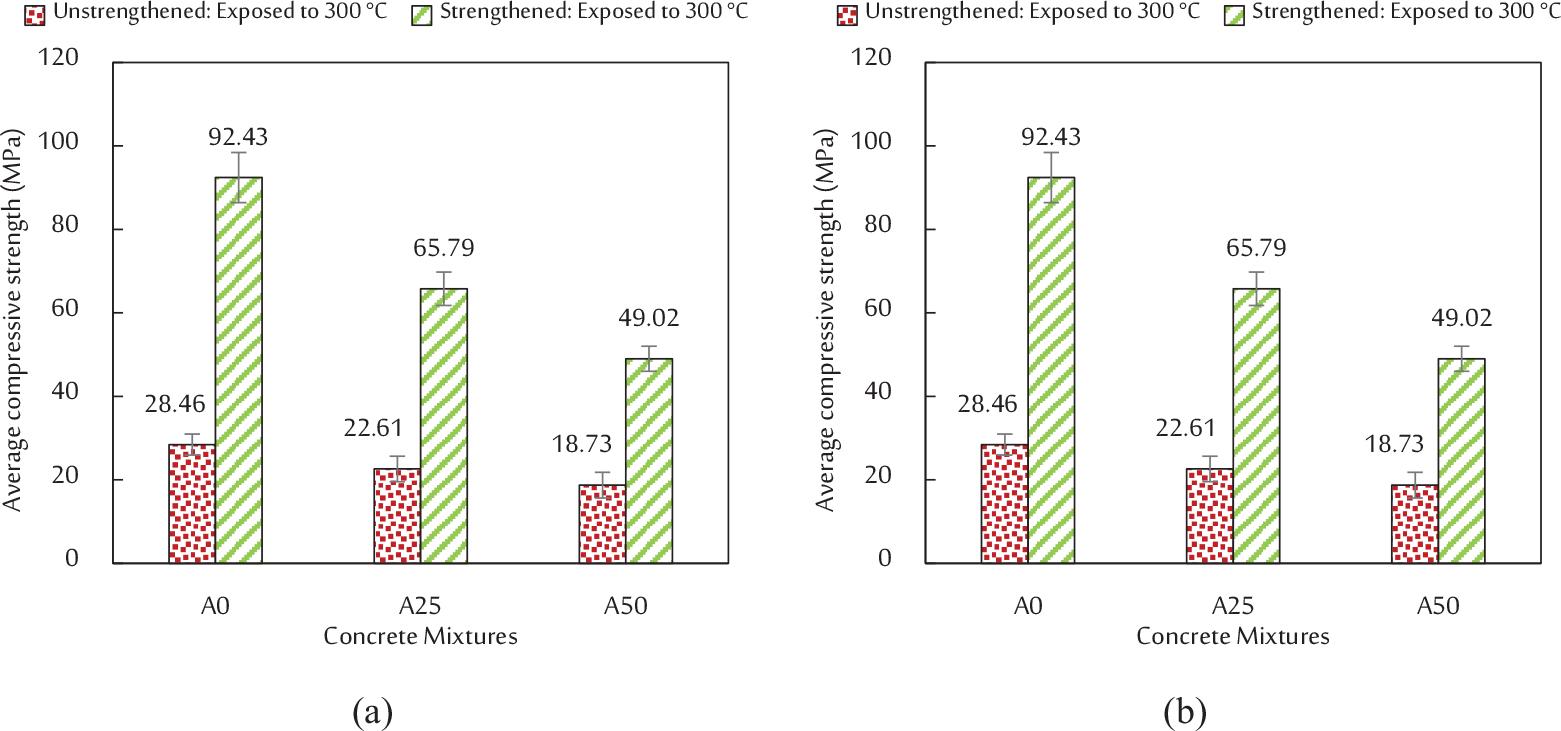

Figure 9 displays the average compressive strengths of the three samples for all mixtures. For the unheated specimens, after exposure to ambient temperatures (i.e., 26°C), the control mixture (i.e., A0), which was without RAP aggregate, attained a compressive strength of 58.20 MPa after 28 days. The substitution of 25% RAP aggregate (i.e., A25 mixture) led to a substantial decrease in compressive strength, amounting to a loss of 39.1% compared with the A0 mixture, whereas with the increased replacement amount to 50% (i.e., A50 mixture), the decrease in compressive strength was 66.8%. The descending trend indicates that the rate of compressive strength reduction increased as the RAP increased in comparison with the control mix. Previous investigations on cement concrete mixtures that include coarse RAP aggregate have documented a decrease in compressive strength [59, 60]. Therefore, using RAP at a higher percentage increases the decrease in strength. For instance, a study conducted by Hassan et al. [61] demonstrated that completely substituting natural aggregate with RAP aggregate led to a 65% decrease in compressive strength. Similarly, Erdem and Blankson [62] observed a decrease of 56.5% in their study. Previous investigations on cement concrete using RAP aggregate have demonstrated that the decrease in compressive strength is due to the insufficient bonding between the cement mortar and RAP aggregate [10, 15]. This weak bonding is caused by the presence of a bituminous coating at the interfacial transition zone (ITZ), which is a weak point and ultimately leads to failure [62]. The diminished compressive strength of GPC mixtures that include RAP aggregate is thought to be comparable with that of cement concrete [15]. Figure 9 illustrates the contrast in compressive strengths between ambient temperature and 300°C. The compressive strengths of heated specimens were reduced by 51.1%, 36.2%, and 3.0%, respectively, for A0-300, A25-300, and A50-300, compared with the unheated specimens A0-R, A25-R, and A50-R. It can be noticed that the reduction in the compressive strength decreased as the RAP ratio increased. The decrease in GPC’s compressive strength after being subjected to high temperatures can be related to the difference in thermal expansion between the aggregate and geopolymer matrix, as emphasized by Kong and Sanjayan [63]. In addition, when subjected to high temperatures, water that is trapped within the specimens moves toward the outer surface and evaporates. This process ultimately results in the deterioration of the internal microstructure and a decrease in its compressive strength [64]. Regarding the strengthened specimens, the compressive strengths increased by 87.7%, 149.6%, and 368.8%, respectively, for A0-S-R, A25-S-R, and A50-S-R, compared with the unstrengthened specimens A0-R, A25-R, and A50-R when subjected to room temperature (26°C). After strengthened specimens were subjected to a higher temperature (300°C), the same trend for the unstrengthened specimens was noticed. The compressive strengths of heated strengthened specimens were reduced by 15.4%, 25.7%, and 45.9%, respectively, for A0-S-300, A25-300-S, and A50-S-300, compared with the unheated strengthened specimens A0-S-R, A25-S-R, and A50-S-R. The outcomes demonstrated that the CFRP sheets had a favorable influence on confinement for the core concrete. When the load exceeded the ultimate load, concrete expanded as a result of axial compression, which improved the interaction between the two materials and led to increased strength. The results of this study confirm that MK-based GPC provides a feasible substitute for conventional Portland cement concrete. Research indicates that it is possible to attain compressive strengths that are similar or slightly higher, as mentioned in the Introduction section. Nevertheless, the inclusion of RAP affects compressive strength. The asphalt composition and its interaction with the geopolymer matrix are significant factors that need more investigation. Efficiently strengthening GPC mixtures is essential to attaining the necessary strength, which was achieved in this study by using CFRP sheets.

Compressive strength of all specimens

The stress-strain relationship of concrete is a crucial characteristic for assessing the overall performance of structures after being exposed to elevated temperatures (i.e., 300°C). The stress versus axial strain curves of all specimens are shown in Figure 10. Figure 10(a) displays the curves for unheated specimens and Figure 10(b) displays the curves for heated specimens. The stress was calculated by dividing the compressive force by the cross-sectional area of the cylinder. The axial strains were obtained by dividing the downward displacement (recorded by the LVDTs) by the length of the LVDT gage. For the unheated specimens, the stresses exhibited a consistent linear increase during the initial loading phase. In the elastic stage, the strains were quite small, as shown in Figure 10(a). The same trend was noticed in the heated specimens, which exhibited higher strains compared with the heated specimens, as shown in Figure 10(b). As the load increased, the strains gradually reached their maximum limit. The curves started to change to be non-linear until the stresses approached their maximum limits, and then the curve’s slope started to decline and nearly all strain readings surpassed the yield strain limits. Before failing, concrete cylinders showed a significant decrease in stress. Mixtures including RAP aggregate exhibited a decreased stiffness. The decrease in the stiffness with higher RAP aggregate ratios was comparable with the trend reported for the compressive strength. However, the rate of decrease was generally lower. The curve slope decreased with the increases in temperature from 26°C to 300°C, as shown in Figure 10. These curves demonstrate that both the concrete mixtures with and without RAP when exposed to a temperature of 300°C undergo a more significant decrease in initial stiffness. The reduction in strength caused by exposure to a temperature of 300°C can be linked to weak bonding between the geopolymer paste and RAP aggregate, and the loss of moisture content. The findings demonstrate that the CFRP confinement offers efficient strengthening for the core concrete and increases the strength of the specimens. Figure 10(a) and Table 5 demonstrate that the A0-S-R specimens have the highest maximum stresses among all specimens, which indicates that the CFRP sheets successfully improved the resistance of heated specimens by exhibiting greater confinement energy before reaching their ultimate failure point. The effects of CFRP confinement were most apparent when analyzing the increase in axial ultimate strains. The axial strains experienced a significant increase, averaging over 200% compared with the strains of the unstrengthened specimens at ultimate stress. In terms of increasing the ultimate strain, the strengthened specimens demonstrated significantly superior performance to the unstrengthened specimens [53]. For the strengthened specimens after being exposed to high temperatures (300°C), the curves continued as linear until the maximum stress then showed a sudden decrease in the strength. Moreover, it was noticed that the strengthened specimens demonstrated a higher ability to absorb energy (measured by the area under the curve) and post-peak response after being exposed to high temperatures, compared with the unstrengthened specimens. A similar observation was reported in previous studies [1].

Stress-strain curves for all concrete cylinders. (a) Room temperature. (b) Heated at 300°C

Summary of the test results

| Specimen ID | Average compressive strength | COV | Initial stiffness | Toughness index | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (MPa) | Relative variation * | (N/mm) | Relative variation * | % | Relative variation * | ||

| A0-R | 58.20 | – | 9.69 | 19562.6 | – | 1.55 | – |

| A0-300 | 28.46 | -51.1% | 12.98 | 3265.6 | -83.3% | 1.51 | -2.5% |

| A0-S-R | 109.24 | +87.7% | 4.29 | 26563.4 | +35.8% | 1.06 | -31.9% |

| A0-S-300 | 92.43 | +58.8% | 1.65 | 3409.2 | -82.6% | 1.01 | -34.8% |

| A25-R | 35.46 | – | 7.16 | 17900.7 | – | 1.73 | – |

| A25-300 | 22.61 | -36.2% | 13.62 | 2540.9 | -85.8% | 1.52 | -11.7% |

| A25-S-R | 88.50 | +149.6% | 3.43 | 16389.2 | -8.4% | 1.04 | -39.9% |

| A25-S-300 | 65.79 | +85.5% | 2.66 | 2501.5 | -86.0% | 1.01 | -41.3% |

| A50-R | 19.31 | – | 15.39 | 13431.9 | – | 2.00 | – |

| A50-300 | 18.73 | -3.0% | 15.27 | 2019.7 | -85.0% | 1.86 | -7.1% |

| A50-S-R | 90.51 | +368.8% | 5.90 | 9028.6 | -32.8% | 1.03 | -48.2% |

| A50-S-300 | 49.02 | +153.9% | 3.06 | 2152.2 | -84.0% | 1.02 | -49.0% |

Compared to each mixture’s control specimen, a positive sign represents an increase, whereas a negative sign represents a decline. COV, coefficient of variation.

The results clearly demonstrate that the strengthened specimens displayed higher compressive strength than the unstrengthened specimens, as shown in Figure 11. The presence of CFRP jacketing provided confinement for the core concrete, which significantly increased the compressive strength. The strengthened specimens that were exposed to room temperature showed increases in compressive strength for the A0-S-R, A25-S-R, and A50-S-R by 68.5%, 74.4%, 82.7%, and 63.2%, respectively, in comparison with the control specimens A0-R, A25-R, and A50-R, respectively, which were also exposed to room temperature. Furthermore, when specimens were subjected to a higher temperature (i.e., 300°C), the compressive strength decreased compared with strengthened specimens, which were also exposed to room temperature. Owing to the substantial volume of concrete that is occupied by coarse aggregate, the ITZ plays a crucial role in determining its behavior [65, 66]. Moreover, the thermal incompatibility between the aggregate and the geopolymer matrix has a direct impact on the decrease in the strength of concrete when it is exposed to high temperatures [67].

The effectiveness of CFRP strengthening. (a) Unheated specimens. (b) Heated specimens

However, the compressive strengths of the A0-S-300, A25-300-S, and A50-S-300 specimens increased by 224.8%, 190.9%, and 161.7%, respectively, compared with the control specimens A0-300, A25-300, and A50-300, respectively, which were also exposed to a higher temperature. Applying CFRP jacketing for strengthening damaged specimens (i.e., specimens subjected to high temperatures) led to 58.8%, 85.5%, and 153.9% increases in compressive strength for the A0-S-300, A25-S-300, and A50-S-300 specimens, respectively, compared with the compressive strengths of the undamaged specimens (i.e., specimens subjected to ambient temperatures) A0-R, A25-R, and A50-R. This demonstrates the efficacy of the strengthening method, particularly for the damaged specimens. These observation are consistent with previous findings [53, 68]. The strength of the damaged specimens after strengthening surpassed that of the control specimens, even in the presence of RAP with a replacement ratio of up to 50%. Furthermore, although substituting 50% of the coarse aggregate with RAP aggregate resulted in a decrease of up to 66% in compressive strength, the strengthening technique employed in this work effectively improved the compressive strength. The rate of increase in the strength of this specimen reached 13%, which supports the use of RAP as aggregate in GPC as an environmentally friendly alternative. According Bisby et al. [68] found that FRP confinement increases compressive strength at greater damage levels. This suggests that concrete strength increase depends on both unconfined compressive strength and fundamental concrete mix physical characteristics. Concrete mix parameters determine failure strength near the final limit state, which may behave like granular material. This causes shear failure like granular solids and soils.

Stiffness has a considerable influence on the distribution of loads on the reinforced concrete (RC) structures. Consequently, the strengthening approach for damaged specimens must be capable of restoring compressive strength and stiffness. The elastic behavior of strengthening heated specimens using CFRP jacketing can be understood by assessing the initial stiffness of the specimens. The initial stiffness was calculated by dividing the stress by the strain, which corresponds to 40% of the maximum compressive strength. At this level, there have been no indications of any cracks in the cylinder specimens. Table 5 presents the summary test results, including the compressive strength, initial stiffness, and toughness index of all concrete cylinders. Table 5 and Figure 10 indicate that heated specimens exhibited a significant decrease in their initial stiffness. In addition, the strengthened specimens that were subjected to a temperature of 300°C for 3 h exhibited a significant decrease in their initial stiffness. Moreover, the presence of RAP also caused a decrease in initial stiffness. The initial stiffness of heated specimens A0-300 and A0-S-300 was 83.3% and 82.6% less than that of unheated specimens A0-R and A0-S-R, respectively. Moreover, the same trend was noticed with the RAP, with replacement levels of 25% and 50%, in which the reduction ratios reached up to 86% compared with each mixture’s control specimen. In addition, the specimens with 50% RAP exhibited the lowest initial stiffness, regardless of whether exposed to 300°C or 26°C, which can be attributed to the poor bonds between the concrete geopolymer matrix and RAP aggregates. The findings indicate that the strengthening of damaged specimens has a minimal influence on the initial stiffness of the specimen. Nevertheless, the heated RAP specimens that were strengthened resulted in a decrease in the initial stiffness loss in comparison with the heated RAP specimens without CFRP jacketing. As an illustration, the initial stiffness of A50-S-300 decreased by 6.6% when CFRP jacketing was present, but it slightly increased for A25-S-300 by 1.5% in the RAP specimen with CFRP jacketing. However, the A0-S-300 specimen exhibited a reduction of 4.4% compared with the A0-300 specimen. The decreased initial stiffness of the heated specimens is mostly related to the formation of micro-cracks and the consequent water loss, which leads to the concrete softening and developing pores. As a result, it is expected that heated specimens will exhibit a higher degree of lateral expansion compression than unheated specimens [69].

The method of assessment proposed by Khaloo et al., [70] was used to determine the toughness index of the concrete mixtures. The toughness index was determined by applying Equation (1) to the stress-strain curves, as illustrated in Figure 12.

The toughness index calculation

The toughness index for the different mixtures is displayed in Table 5, indicating that substituting conventional aggregate with RAP aggregate results in a higher toughness compared with the control mixture. The toughness index showed an increase from 1.55 in the control mixture to 1.73 and 2.0 in mixtures A25 and A50, respectively, under the ambient temperatures. The study concludes that adding RAP aggregate to GPC mixtures improves the post-peak behavior by reducing the decreased rate of compressive strength, compared with mixtures that exclusively contain conventional aggregate. Moreover, the toughness index values of heated specimens A0-300, A25-300, and A50-300 were 2.5%, 11.7%, and 7.1% less than those of the unheated specimens A0-R, A25-R, and A50-R, respectively. Although the implementation of CFRP strengthening led to an increase in compressive strength by rates reaching 149.6%, the toughness index decreased compared with the control specimens. The same trend was observed when the strengthened specimens were exposed to high temperatures. The toughness index values of the strengthened specimens A0-S-R, A25-S-R, and A50-S-R were 31.9%, 39.9%, and 48.2% less than those of the unheated specimens A0-R, A25-R, and A50-R, respectively. In addition, the toughness index values of the heated and strengthened specimens A0-S-300, A25-S-300, and A50-S-300 were 4.2%, 4.0%, and 3.6% less than those of the unheated specimens A0-S-R, A25-S-R, and A50-S-R, respectively. It can be seen that the heated and strengthened specimens had a sudden failure (see Fig. 10), as the toughness index values were nearly equal to 1 and therefore deteriorated postpeak response.

The present study examined the strengthening of heat-damaged MK-based GPC cylinders incorporating RAP by the use of CFRP composite. The conventional aggregate was substituted with RAP aggregate at 25% and 50% replacement levels. In addition, the concrete cylinders were tested under ambient conditions and subjected to 300°C. The following conclusions were drawn:

The inclusion of RAP aggregate in the mixtures did not significantly affect the ultimate failure mode of the concrete specimens, while the concrete cylinders displayed more cracks and crushing when subjected to an elevated temperature of 300°C. The strengthened specimens exhibited concrete crushing, with CFRP rupture as the mode of failure.

The substitution of 25% RAP aggregate significantly reduced compressive strength by 39.1%, while an increased 50% replacement resulted in a 66.8% decrease compared with the A0 mixture.

The compressive strengths of both the RAP and strengthened specimens reduced significantly after being exposed to a temperature of 300°C, reaching up to 51.1% and 45.9%, respectively, compared with the same specimens exposed to an ambient temperature.

The use of CFRP sheets significantly increased compressive strengths, with increases ranging from 87.7% to 368.8% at 26°C and 58.8% to 153.9% at 300°C, compared with each mixture’s control specimen.

The use of CFRP sheets for strengthening successfully improved the resistance of heated specimens by increasing compressive strength and confinement energy before reaching their ultimate failure point.

The initial stiffness of both the RAP and strengthened specimens was reduced significantly regardless of whether they were exposed to 300°C or 26°C, except for the A0-S-R specimen, which showed an increased ratio of 35.8% compared with A0-R.

The study concludes that adding RAP aggregate to GPC mixtures improves the postpeak behavior by reducing the decreased rate of compressive strength, compared with mixtures that exclusively contain conventional aggregate.

The study was constrained by examining RAP aggregate at 25% and 50% replacement levels, suggesting the potential for further investigation with varying replacement percentages. Furthermore, the concrete cylinders underwent testing under ambient conditions and were exposed to temperatures of 300°C. Future studies may consider exploring a wider range of temperature rates and values to increase understanding of the subject matter.