In an era characterised by rapid change and uncertainty, organisations are increasingly confronted with unforeseen threats that often escalate into full-blown crises before they are fully recognised (Bell 2002; Kerr 2016; Seville 2016). The competitive landscape they navigate has become notably challenging, particularly within military organisations where the stakes are exceptionally high (Baker and Refsgaard 2007; Jakob Sadeh 2024). Despite efforts, it is virtually impossible for organisations to preemptively identify and plan for all potential hazards and their repercussions. Recent global events such as the COVID-19 pandemic, military conflicts and geopolitical instability, energy crises, cyberattacks and natural disasters provide examples of these challenges, exemplifying extreme disruptions, underscoring the critical need for robust organisations with a capability to thrive in such turbulence (Masten 2007; Burnard and Bhamra 2011; Raetze et al. 2021; Zhang et al. 2021; Ingram et al. 2023). Understanding and quantifying resilience in organisations has become essential for strategic planning and operational continuity. Despite the importance of this construct, the current research landscape reveals a scarcity of rigorous tools to measure organisational resilience (OR) quantitatively (Hillmann and Guenther 2021), underscoring the urgency for research in this vital area. This article explores the development of a new measurement for OR, aiming to fill the existing gap in quantitative, statistically validated metrics. The 6-factor organisational resilience tool (6FORT) described in this study aims to provide military leaders, organisational researchers and practitioners with data for more accurate and effective emergency preparation and recovery plans, thus enhancing OR and its development process.

Definitions of OR abound in the literature, reflecting a growing interest and awareness amongst organisations (Coutu 2001; Stephenson 2010; Weick 2018; Kołodziej et al. 2024). However, establishing a cohesive and measurable theoretical framework that encapsulates OR remains a challenge (Lee et al. 2013; Whitman et al. 2013; Kołodziej et al. 2024). Whilst much of the research has been qualitative and descriptive (Somers 2009), the development of empirical tools to measure OR lags (Carpenter et al. 2001; Norris et al. 2008; Stephenson 2010; Lee et al. 2013; Leykin et al. 2013; Patriarca et al. 2018). Recent studies have underscored the evolving landscape of measuring OR, emphasising both the necessity and complexity of this endeavour, highlighting the need for standardised frameworks and for integrating more theoretically grounded approaches to measuring resilience in organisations. Bridging this theoretical framework with robust empirical evidence linking everyday organisational activities to resilience-building and adaptive responses to adversity is crucial to incentivise investments in resilience development (Somers n.d.; Carpenter et al. 2001; Lee et al. 2013; Nilakant et al. 2014; Walker 2020). Whilst various tools have been developed to measure resilience within organisations, many of these existing metrics fall short in several critical areas. A significant limitation is their often qualitative nature, which can lead to subjective interpretations and inconsistencies in assessment. Furthermore, many current tools lack a statistical validation framework, making it difficult to reliably compare resilience across different units or organisations. Additionally, existing measures may not capture the dynamic interplay of factors affecting resilience, such as organisational culture, leadership and external threats. This gap underscores the necessity for a more robust, quantitative approach that provides actionable insights and supports strategic decision-making in complex, high-stakes environments (Bartone 2006; Whitman et al. 2013; Gordon et al. 2021; Hillmann and Guenther 2021; Raetze et al. 2021).

Traditionally, OR has been viewed as the ability to rebound from crises, akin to ‘bouncing back’ in physical sciences (Horne and Orr 1998; Mallak 1998; Sutcliffe and Vogus 2003; Lengnick-Hall et al. 2011). This perspective emphasises coping strategies and the swift restoration of normal operations (Masten and Obradovic 2008), also referred to in literature as anti-fragility, which focuses on withstanding shocks and stressors (Taleb 2007). Alternatively, a more contemporary view extends resilience beyond mere recovery to include the development of new capabilities and opportunities in response to challenges, thus growing from adversity (Coutu 2001; Sutcliffe and Vogus 2003; Caza and Milton 2012; Coldwell 2012; Weick 2018). Here, resilience is regarded as a dynamic process involving many organisational capabilities, enabling organisations not only to navigate crises but also to innovate and thrive in changing environments (Lengnick-Hall et al. 2011).

There are various viewpoints regarding the scope of resilience within organisations. Some perspectives emphasise personal resilience, suggesting that the resilience of individual employees is crucial for navigating crises (Hillmann and Guenther 2021). The literature has categorised resilience across multiple levels, highlighting that it can be fostered at personal, group and collective levels (Linnenluecke 2017) within both individuals and teams. Lengnick-Hall, for example (2011), has constructed resilience at the organisational level, where resilience is derived from a specific set of processes and organisational characteristics, such as routines, practices and capabilities. However, a comprehensive measurement encompassing all these levels remains elusive.

Empirical evidence highlights a positive relationship between OR and performance across various contexts (Bass et al. 2003; Dalziell and Mcmanus 2004; Quigley et al. 2018; Yang and Hsu 2018; Bustinza et al. 2019; Rodriguez-Sanchez et al. 2021). This connection underscores the importance of resilience in enhancing organisational learning, effectiveness and overall operational performance (Sutcliffe and Vogus 2003; Reason 2007).

Some organisations are more equipped than others to deal with adversity. Organisational crisis most often conveys a fundamental threat to the very stability of the system, questioning core assumptions and beliefs, challenging the ability to perform the main tasks (Pearson and Clair 2016). High reliability organisations (HROs) (Reason 2007), which originated from the military, hold a collective preoccupation with the possibility of failure. These organisations optimise to ensure operational continuity and reliability, during routine interruptions and during emergencies. These organisations, operating under constant threat with critical operational requirements, exemplify resilience in action (Dautoff 2001; Paton and Johnston 2001; Shin et al. 2012; Pearson and Clair 2016; Barasa et al. 2018). Military organisations are such HROs; they are designed to harbour adaptive forms of conduct so they can perform during a crisis.

Military leaders have long sought to understand and influence unit resilience due to the high-stress nature of military service. Soldiers face challenges such as isolation, ambiguity, demanding workloads and dangerous conditions, contributing to stress, anxiety, PTSD, and retention issues (Tannenbaum et al. 2024). Whilst resilience programmes exist, most focus on individual resilience rather than organisational factors such as teamwork, cohesion and processes (Meredith et al. 2011). Research suggests that OR is not simply the sum of individual resilience but a distinct phenomenon (Lengnick-Hall et al. 2011; Powley 2013). Even highly resilient individuals may struggle in teams due to communication breakdowns and coordination issues, highlighting the need to study resilience at both individual and team levels (Stoverink et al. 2020).

When considering operational continuity in the military, numerous factors influence the overall position, and leaders strive to ground their decisions on data-driven insights. Gaining a clear understanding of the elements that affect a unit’s resilience, along with establishing specific metrics for each unit, can serve as a crucial decision support tool. This approach allows military leaders to identify weaknesses, highlight and enhance strengths and target resilience development efficiently.

Over the past decade, several tools have been developed to measure OR, each using unique frameworks and methodologies. Quantitative studies often rely on surveys and self-reported attitudes, but challenges arise in reaching organisations during crises, resulting in a scarcity of data collected during or immediately after such events (Lee et al. 2013; Whitman et al. 2013; Raetze et al. 2021). Common measurements utilise multidimensional scales to assess attributes such as planning, agility, resourcefulness and overall capacity to manage adversity (Twigg 2007; Stephenson 2010; Lee et al. 2013; Leykin et al. 2013; Raetze et al. 2021). For instance, the conjoint community resilience assessment measure (CCRAM) focuses on community resilience and includes five factors – leadership, collective efficacy, preparedness, place attachment and social trust (Leykin et al. 2013). Another example is the Benchmark Resilience Tool (BRT-53), which was derived using qualitative research in organisations experiencing natural disasters. It comprises 53 items, providing organisations with insights into their resilience strengths and weaknesses on a two-factor scale of adaptive capacity and planning (McManus 2008; Lee et al. 2013). The Organisational Resilience Potential Survey (ORPS, Somers 2009) and the Communities Advancing Resilience Toolkit (CART) (Pfefferbaum et al. 2013) are additional tools that assess resilience potential and community strengths, respectively, each utilising quantitative methods to gather relevant data. Collectively, these tools strive to offer practical frameworks for organisations to monitor resilience and develop effective interventions, but none were quantitatively validated and customised for HROs. A validated measure of team resilience in the U.S. Army is the Team Resilience Scale (TRS; Tannenbaum et al. 2024), a 12-item tool assessing team resilience as a capacity across three dimensions: physical, affective and cognitive. Whilst this study provides a valuable group-level measure, it overlooks key organisational and cultural factors that, from our perspective, impact operational resilience.

This study aims to contribute to the understanding of OR by examining the development and psychometric characteristics of the 6FORT model. The study conceptualised OR as a latent construct that cannot be directly observed but can be inferred based on responses to indicators (i.e., items). Latent constructs may also give rise to certain behaviours; thus, it is important to monitor and develop. The paper will describe the factor structure for measuring OR and demonstrate its efficacy as an assessment tool in environments where few empirical tools exist. The novelty in this tool is that it provides a statistically validated qualitative measure of OR, based on a vast body of data, providing a multi-level perspective and a practical model for simple implementation. The tool is introduced as a key component in the process of preparing Israeli Air Force (IAF) squadrons for their missions in combat.

The IAF is a classic military organisation, hierarchic and centralised in war, with a unique culture of excellence, task-driven teams, orderly processes, widely known for its debriefing and learning culture (Gordon 2003). The past few years have been exceptionally challenging for IAF squadrons, dealing with natural disasters, the COVID-19 outbreak and several military conflicts, including ‘Iron Swords’, which is still in effect. Other organisational challenges facing the IAF, like other military organisations are fatal accidents, organisational and leadership changes and HR management. Retaining continuity of operations is one of the main issues occupying IAF leadership today, so the organisation must invest in developing resilience.

This study was conducted in IAF operational squadrons, from flight sectors (fighter jets, rescue helicopters and cargo-reconnaissance) and remotely piloted aircraft (RPA) squadrons. These squadrons are different from each other by the type of mission they hold, the professional training they go through (pilots and operators) and the degree of exposure to threat is higher in flight squadrons, although a moral, emotional and also some physical threat exists in RPA squadrons (Gal et al. 2016). Due to all of these, there are some specific characteristics to each squadron. However, all squadrons spend most of their time preparing to operate in wartime, contingencies and other engagements and preparing aircrews and operators (in RPA) for various assignments. OR enhancement is relevant in all these squadrons.

In the past, these squadrons received a general measure of personnel satisfaction, measuring squadron climate. For example, motivation, safety climate, professional capabilities and combat readiness. These factors were not integrated into an operational framework, nor were they professionally framed as important to the resilience development process.

This manuscript outlines the development of 6FORT in the following structure: The next chapter presents the methodology used in the tool’s development. This is followed by a detailed description of the tool, its key characteristics and the multi-level framework derived from its creation. The subsequent chapter covers the validation and analysis process of the tool. A discussion on its applications follows, and the manuscript concludes with final thoughts.

6FORT is a self-report measure, which assesses the attitudes and perceptions of squadron members about various aspects of their organisation’s resilience. The tool is based on a multilevel model of OR, which will be described shortly in this manuscript. 6FORT was developed considering multiple perspectives, using a mixed methods research design, in a process extending over 3 years, and was based on a large organisational database. The process followed common practices described in the literature regarding scale development and validation processes (Hinkin 1995). Additional criteria for developing 6FORT included ensuring content validity, demonstrating internal consistency, being recognised as relevant by military subject matter experts (SMEs), and showing expected correlations with related variables (Tannenbaum et al. 2024).

There were three main phases to the process. The current study presents data from the validation process. This is an overview of the research phases:

- (1)

Contextualisation

An extensive literature review helped to form a framework for the contextualisation of OR in IAF squadrons. This stage helped to deeply understand the resilience phenomenon, as it pertains to the relevant field of research, whilst strengthening the ability to achieve content validity in the item generation stage.

- (2)

Item generation and scale development:

This stage was based on both qualitative and quantitative methods. Qualitative methods were used to establish a link between practical knowledge and theoretical constructs and to generate new items. First, the quantitative part of this stage included a statistical exploration of an existing IAF database of annual organisational assessment surveys from 2008 to 2019, for a total of 17,181 participants. The surveys are based on the Michigan Organisational Assessment Questionnaire (MOAQ), first developed by Lawler et al. in 1983 (Bowling and Hammond 2008) and include leadership assessment items based on Bass and Avolio’s Full Range Leadership Model (Bass et al. 2003). Items were sorted using exploratory factor analysis (EFA), and factors relating to OR according to the literature review were chosen by the authors. At this stage, 13 factors were found (including, for example, leadership, execution ability, social trust, learning and resource management).

In the qualitative part of this stage, workshops were conducted, with semi-structured interviews with key informants (SMEs) and discussions investigating practical and theoretical definitions of OR and items, which should measure it in the IAF. Thirteen new items were phrased at this stage for subjects, which were not sufficiently represented in the initial questionnaire, considering the literature review (the multilevel framework) and expert opinions. Next, the Delphi method was used to construct the scales. This is a structured and scientifically valid consensus reaching method for content validity (Hasson et al. 2000). A team of 40 OR and IAF SMEs was given a list of 80 items to sort according to their relevance for measuring OR in IAF squadrons. This stage derived 55 items measuring OR, 5 items measuring performance and 1 item measuring OR directly, for a total of 62 items to go into the pilot study.

- (3)

Instrument validation:

This stage provided scale evaluation information. First, in 2021, a pilot study was conducted to test the internal and external validity of the tool, using a sample of 493 participants from operational squadrons. A reliability assessment was performed, and 43 items were chosen for the OR scale. Then, in 2023, instrument validation was conducted, using an independent sample of 1,097 participants from operational squadrons.

The following chart summarises the research process:

| Phase | Key steps | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Contextualisation |

|

|

| Item generation & scale development | Quantitative methods:

|

|

Qualitative methods:

|

| |

| Instrument validation |

Pilot study (2021):

|

|

Validation study (2023):

|

|

EFA, exploratory factor analysis; IAF, Israeli Air Force; OR, organisational resilience; SMEs, subject matter experts.

Participants in the pilot study included 493 IAF operational squadron members. Participants were in reserve duty (about 50%), and the other half of the group was on emergency posting and mandatory duty, split equally. Emergency posting members are on active duty in different parts of the IAF (such as positions at Head Quarters (HQ)) and are an active part of the squadron. Both emergency posting and reserve duty members train once a week with the squadron. A total of 10 squadrons participated in the study, with a 55%–75% response rate, out of all squadron personnel.

Participants in the validation stage included 1,097 IAF operational squadron members. A similar distribution of types of duty as mentioned above applies to this group. A total of 25 squadrons participated in the study, with a 75%–90% response rate out of all squadron personnel.

Other demographics – 2% were female and 98% male, which is close to the overall gender distribution in the operational squadron population. The average age is 35.2 years. The participants included personnel from mandatory duty, reserve duty and emergency posting (as part of the mandatory duty), with percentages similar to their representation in the IAF population (25%, 50% and 25%, respectively).

The final questionnaire includes 43 items measuring OR and 5 items measuring squadron performance on a 5-point Likert scale (1-very poor, 5-very high). No reverse items exist in 6FORT, and it takes approximately 15 min to complete. The 6FORT version, which was used in the present study, was the original Hebrew version of the scale. The English items presented in this manuscript are the English version of 6FORT, which was translated and back-translated to ensure meaning preservation.

To establish preliminary evidence for the criterion-related validity for the 6FORT, five performance evaluation items were constructed, intended to assess the performance of the squadron as it is perceived by its members. In addition, as this survey was used in actual field practice, performance measures were critical for squadron commanders receiving the feedback. These items are based on suggestions from OR and IAF experts and were also reviewed by them during Delphi Rounds, but they were not intended to be part of the OR scale. Participants were asked to rate their squadron on a 5-point Likert scale (1-very poor, 5-very high), on different functions of the squadron (e.g. ‘The quality of task performance in the squadron’, ‘Current operational level of your squadron relative to its missions’ and ‘Squadron’s general readiness for war’).

In the pilot study, participants were presented with the following phrase: ‘Resilience is defined as the ability to quickly return to routine after an emergency event. To what extent do you agree with the following sentence’. Then they were asked to rate the item, ‘What is the level of OR in your squadron today’ on a 5-point Likert scale with the same labels used above. This validation method was previously used in the development of CCRAM, a measure of community resilience (Leykin et al. 2013).

The literature review conducted in this study developed a conceptual framework for OR, which was subsequently refined using insights obtained from the qualitative phase of the research. The framework describes multiple organisational levels contributing to OR in IAF squadrons. Figure 1 shows a summary of these levels.

Multilevel framework of OR. OR, organisational resilience.

Individual resilience in the squadron context refers to personal abilities to cope with crises, as highlighted in previous research (Masten and Reed 2002; Bolton 2004). This includes professional skills, alignment with squadron values and self-efficacy (Hobfoll 1989; Coutu 2001; Dautoff 2001; Bartone 2006; Youssef and Luthans 2007; Lengnick-Hall et al. 2011). This includes individuals’ attitudes towards their role in the squadron and their alignment with organisational goals (Omer and Alon 1994; Coutu 2001; Dautoff 2001).

Group Level of Resilience encompasses the interactions amongst squadron members, their shared norms and distinctive organisational characteristics. It includes key factors such as teamwork, cohesion, governance and learning processes, resourcefulness and emergency preparedness (Tierney 2003; Norris et al. 2008; Powley and Lopes 2011; Leykin et al. 2016; Barasa et al. 2018; Hartmann et al. 2020; Lombardi et al. 2021; Raetze et al. 2021).

Resilient leadership defines how leaders motivate, build trust, inspire and prepare squadrons for diverse scenarios. Leadership style and capabilities, particularly in crisis situations, play a crucial role in operational effectiveness (Omer and Alon 1994; Bartone 2006; Sutcliffe and Vogus 2007). Strong leadership fosters confidence and trust within the squadron, directly enhancing performance (Masten and Obradovic 2008; Uhl-Bien and Arena 2018). Open communication and trust between leaders and squadron members are critical, as supported by the literature and emphasised later by SMEs (Weick 1996, 2003; Weick et al. 1999; Barasa et al. 2018). Notably absent from the initial questionnaire was consideration of the leadership team’s interaction with squadron members, and this was later incorporated.

Ecosystem Resilience refers to external factors that influence squadron preparedness and ability to deal with adversity. Drawing on Bronfenbrenner’s Systems Theory, this level encompasses elements beyond the squadron’s direct control, including the broader organisational context, such as the wing, air bases and larger military structures (Bronfenbrenner 1992). Key aspects include resource allocation and the availability of adequate resources, external partnerships that support operational continuity and the effective utilisation of external information for situational awareness and to promote learning (Dalziell and Mcmanus 2004; Redman 2005; Kantur and Iseri-Say 2012; Pfefferbaum et al. 2013; Powley 2013; Seville 2016; Martin 2021).

This framework was further refined through consultations with SMEs in the next stage of the research. It guided the development of an additional 6FORT questionnaire item to address previously unrepresented aspects. The newly added items are detailed in Appendix 2.

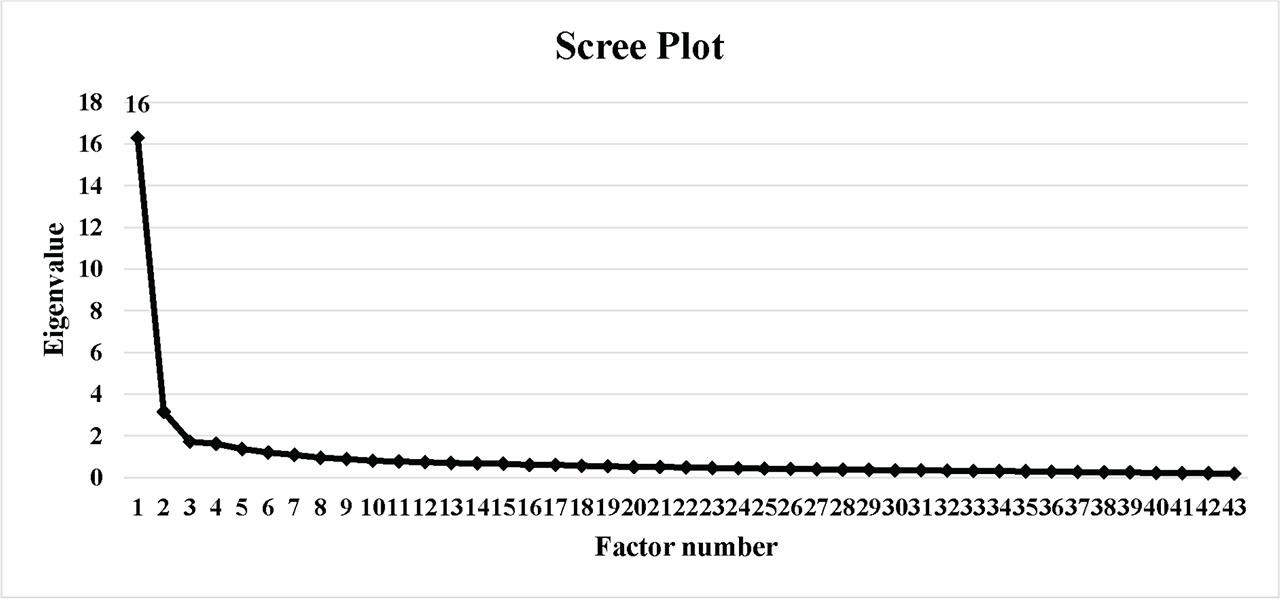

In the pilot study, principal axis factoring (PAF) was used as the method of extraction, as it is the recommended method when the goal is to identify latent constructs (Watkins 2018). Furthermore, as the latent constructs here were hypothesised to be correlated, oblique rotation was chosen over varimax rotation of the factors. The scree test was applied to determine the optimal number of factors, observing the scree plot for Eigenvalues greater than 1 and to the point where the eigenvalues level off (Cattell 1966; Costello and Osborne 2005). Items removed included items with no loading or double loading to factors and items with similar meaning (considering Pearson’s correlations, with r = 0.65 or above). An exception was made for items that were perceived as contextually important by the authors, and these two items were retained in the questionnaire. There were three stages of omissions, after which the analysis was rerun, and the rotated structure was examined.

The process began with 55 items on the OR scale. After several runs and deletion of items with similar meaning and high correlations, the analysis resulted in 43 items remaining in the questionnaire, yielding six factors with eigenvalues between 1.2 and 16.3. The scree test, as shown in Figure 2, shows six points remaining above the flattened line of the eigenvalues.

Scree test plot for EFA of the initial pilot 6FORT questionnaire. 6FORT, 6-factor organisational resilience tool; EFA, exploratory factor analysis.

The following factor structure was first composed of these six factors: leadership, professionalism, task readiness, open communication, organisational learning and connectedness. Appendix 1 provides a summary of the final EFA (which is in fact the final 6FORT questionnaire, since no additional changes were made in the validation study).

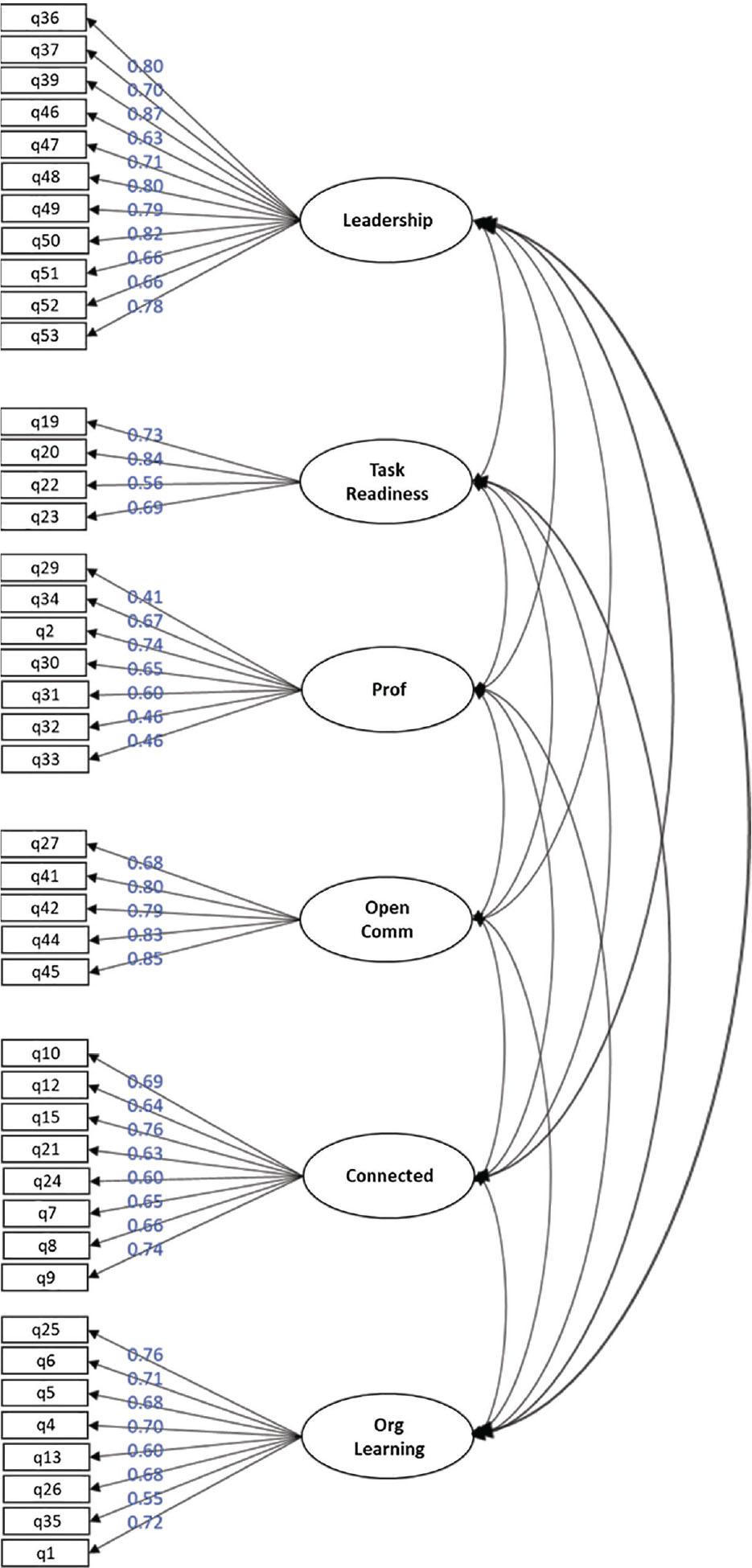

CFA was calculated based on the factors identified in the EFA. Fit indices that were used were: comparative fit index (CFI), non-normed fit index (NNFI) and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) with its 90% confidence interval (CI). As a rule of thumb, values of RMSEA less than 0.08 indicate an acceptable fit, and values of CFI and NNFI larger than 0.90 indicate an acceptable fit (Hu and Bentler 1999).

The model (Table 1) was found to have an acceptable fit: CFI = 0.915, NNFI = 0.902, RMSEA = 0.049 (90%CI = 0.047, 0.051). Figure 3 shows the standardised parameter estimates for the factor structure of 6FORT. No items were deleted at this stage. The loadings on each arrow represent the association between items and their respective factors.

Fit indices of the CFA of 6FORT (N = 1097)

| Goodness-of-fit indices | χ2 (df) | p | CFI | NNFI | RMSEA | 90%CI for RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFA | 2,988.36 (823) | <0.001 | 0.915 | 0.902 | 0.049 | 0.047, 0.051 |

6FORT, 6-factor organisational resilience tool; CFA, confirmatory factor analysis; CFI, comparative fit index; NNFI, non-normed fit index; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation.

Standardised parameter estimates for the factor structure of 6FORT. 6FORT, 6-factor organisational resilience tool.

The final version of the 6FORT includes a total of 43 measuring OR, and an additional 5 items measuring performance were added. Table 2 presents the detailed attributes of these factors.

6FORT list of factors and their attributes

| Factors and definitions | Item | M | SD | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leadership: | 11 | 4.29 | 0.64 | 0.93 |

| Leadership evaluation of the squadron commander’s abilities. | ||||

| Professionalism: | 7 | 4.07 | 0.50 | 0.80 |

| Skills and capabilities of squadron members referring to individuals, formation leaders and flight teams (including cockpit CRM). | ||||

| Task readiness: | 4 | 3.81 | 0.63 | 0.80 |

| Squadron’s level of preparedness for its primary task in an emergency, collective efficacy regarding adversity and combat. Includes the evaluation of resources to achieve operational continuity in the squadron. | ||||

| Open communication: | 5 | 4.10 | 0.76 | 0.91 |

| Regarded as a leadership practice and a cultural attribute, referring to squadron communication style, the ability to create trusting and open conversations between members and with squadron leaders. | ||||

| Connectedness: | 8 | 4.29 | 0.54 | 0.88 |

| Group dynamics, cohesion and social trust, sense of belonging and identification, role clarity in critical times. | ||||

| Organisational learning: | 8 | 3.9 | 0.61 | 0.87 |

| Squadron’s ability to develop and accumulate knowledge, enhance competencies and increase the capacity to perform better through a learning culture and processes. | ||||

| Total | 43 | 4.11 | 0.49 | 0.96 |

| Performance scale | 5 | 4.20 | 0.54 | 0.81 |

6FORT, 6-factor organisational resilience tool; CRM, crew resource management.

Pearson’s correlations were run to examine the correlations between the factors of 6FORT. Each factor was defined according to its specific items. The correlation analysis resulted in positive and significant (p < 0.001.) correlations, with moderate to high effects amongst all factors (with r = 0.43 for open communication and task readiness, and r = 0.90 for leadership and open communication). All correlations are presented in Table 3.

6FORT factor correlations*

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Leadership | _ | |||||

| 2. Professionalism | 0.68 | |||||

| 3. Task readiness | 0.55 | 0.84 | ||||

| 4. Open communication | 0.90 | 0.62 | 0.43 | |||

| 5. Organisational learning | 0.80 | 0.89 | 0.78 | 0.73 | ||

| 6. Connectedness | 0.69 | 0.82 | 0.72 | 0.65 | 0.83 | - |

All correlations were significant (p < 0.001).

6FORT, 6-factor organisational resilience tool.

Participants were asked to evaluate the performance of their squadron using 5 items – creating a performance scale score. In accordance with the evaluations of OR, evaluations of performance were high (M = 4.2, SD = 0.54), ranging from 1 to 5. That is, the participants evaluate their squadron’s performance rather highly.

In addition, a single item measuring OR was added to the questionnaire (described above) and was answered by 1,071 participants (M = 4.0, SD = 0.65), ranging from 1 to 5.

Table 4 presents Pearson’s correlations between the factors of OR and the participants’ perception of performance, and their evaluation of OR with a single-item measure. Results show that all correlations are positive and significant, with moderate to high effects. Higher OR calculated by the compound 6FORT index was related to a higher performance evaluation, as was expected and discussed by the existing literature, thus lending support for the criterion-related validity of the measure of OR. Convergent validity is demonstrated through the positive relationship between a single item measuring OR and the 6FORT factors, also shown in the table.

Pearson’s correlations between 6FORT factors with performance evaluations and with a single-item measure of OR (N = 1097)

| OR factors | Performance evaluation | Single-item measure of OR |

|---|---|---|

| Leadership | 0.67 | 0.50 |

| Professionalism | 0.72 | 0.51 |

| Task readiness | 0.63 | 0.49 |

| Open communication | 0.58 | 0.40 |

| Organisational learning | 0.81 | 0.56 |

| Connectedness | 0.74 | 0.61 |

6FORT, 6-factor organisational resilience tool; OR, organisational resilience.

OR is widely recognised as crucial during crises by both researchers and practitioners (Burnard and Bhamra 2011; Duchek 2020; Hillmann and Guenther 2021). A quantifiable and valid measurement of OR is essential for translating this complex theoretical concept into a practical tool for organisational practice and intervention planning before, during and after adversity. The present study introduces the 6FORT as a tool and describes its psychometric properties and factor structure.

The development of 6FORT represents a significant innovation in measuring OR as an operationalised construct in a military environment. By serving as a comprehensive database for decision-making, 6FORT enables operational squadrons to identify their actual strengths and weaknesses concerning resilience. This clarity provides a foundation for designing emergency readiness plans that are highly customised to the specific needs and dynamics of each squadron, enhancing their overall preparedness and adaptability in challenging environments.

Measuring OR over time using 6FORT serves as an asset to squadron leadership, providing baseline data for evaluating resilience during steady-state and crisis conditions. Continuous assessment of determined iterations allows leaders to monitor resilience domains and track changes and improvements over time. Conducting a diagnostic pulse check of a unit ‘in action’ could be applied following both interventions and actual adversities, aligning resilience measures with other operational criteria and performance metrics and providing a research base, enhancing organisational learning about coping processes. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the IAF utilised 6FORT to assess how each squadron was managing challenges, offering valuable insights for predicting operational continuity issues and delivering feedback and support to squadron and wing commanders.

The following section dives into each of the six factors identified in 6FORT, exploring their connections to existing research and providing examples of how they manifest in IAF squadrons. Understanding the implications of each factor is important, as 6FORT can be used by military leaders as a theoretical model as well as a tool for unit assessment. Each factor aids in highlighting unique OR properties and possible vulnerabilities within the squadron, thus pointing to distinct areas for OR development and improvement.

Existing resilience tools such as CCRAM (Leykin et al. 2013), ORPS (Sommers 2009) and CART (Pfefferbaum et al. 2013) guided the development of 6FORT. Amongst them, the BRT-53 is the most comparable, sharing content similarities despite being designed for different populations (McManus 2008; Stephenson 2010; Whitman et al. 2013).

Leadership emerged as the most significant factor in 6FORT. Squadron leadership plays a pivotal role in crisis management by contextualising crises, translating objectives into actionable plans, instilling confidence and fostering morale through sense-making, effective training and resource management (Timmons 1993; Gordon 2003; Masten and Obradovic 2008; Ausink et al. 2018). Strong leadership is critical for navigating uncertainty and cultivating purpose and direction during crises (Weick et al. 1999; Bass et al. 2003; Powley and Lopes 2011). This research highlights leadership practices and development as pivotal for fostering resilience in IAF squadrons. Following the implementation of 6FORT, leadership development processes are designed to focus on operating effectively under stressful conditions, understanding one’s responses to stress, refining crisis management skills and strengthening day-to-day leadership capabilities that support combat operations. These efforts aim to cultivate strong commanders who excel both in routine operations and during emergencies.

Open communication, though conceptually related to leadership, emerged as a distinct factor in 6FORT’s analysis. It reflects both a leadership practice and a cultural trait, fostering cohesion through building trust and meaningful relationships (Mudrack 1989; Sampson et al. 1997; Norris et al. 2008; Cohen et al. 2017; Kwon 2019). Effective communication includes, for example, encouraging squadron members to speak their mind, being open to criticism, awareness of squadron members’ expectations. These promote psychological safety, which is essential for innovation, critical thinking and adaptability during crises (Graen and Uhl-Bien 1995; Weick 2003; Stephenson 2010; Coldwell 2012; Barasa et al. 2018). In HROs such as IAF squadrons, open communication is vital for creating an effective learning environment and encouraging constructive feedback (Frazier et al. 2017; Oster and Braaten 2017). Given the reliance on small, highly interdependent teams, poor communication has been known as a potential cause for accidents, so this factor also contributes to safety climate formulation.

Professionalism in 6FORT focuses on the ability to perform missions effectively before, during and after adversity, specifically preparing for combat and during war. At the personal level, this concerns individuals’ self-perceptions and actual abilities to perform (Weick 1993, 2003; Caza and Milton 2012). At the group level, professionalism also deals with crew resource management (CRM), which highlights the importance of crew members’ role execution in the cockpit and team coordination during missions and on the ground (Salas et al. 2001).

The task readiness factor underscores the squadron members’ confidence in handling primary tasks through preparedness and self-reliance, essential for operational continuity (Paton and Johnston 2001; Weick 2003). Existing literature describes prepared and self-reliant individuals as the foundation of resilient organisations (Paton and Johnston 2001; Weick 2003). Prepared systems are considered more likely to deal with threats and adversity (Folke et al. 2002), but emergency preparedness is not always incorporated into models of OR (Uscher-Pines et al. 2012). In 6FORT, readiness was defined as having the required set of resources and processes to hold operational continuity in the face of adversity. Readiness was previously connected to training, exercises and planning for emergency (Barasa et al. 2018); thus, 6FORT offers measures of these elements. Task readiness was found to have a significant association with performance in this study.

Organisational learning assesses a squadron’s ability to gather knowledge and improve competencies based on past experiences, a vital capability for adapting and enhancing performance over time (Sutcliffe and Vogus 2003; Powley and Lopes 2011). Existing literature identifies learning from events as one of the most critical components of resilient organisations (Senge 1994; Dautoff 2001; Sutcliffe and Vogus 2003; Redman 2005; Saveland 2008; Lengnick-Hall et al. 2011; Martin 2021). The 6FORT tool evaluates this learning process by including items related to the effective use of organisational information (Horne 1997; Powley and Lopes 2011; Lee et al. 2013; Seville 2016; Uhl-Bien and Arena 2018), fostering innovation and creativity to promote new knowledge (Stephenson 2010), process management, governance and control (Stephenson 2010; Barasa et al. 2018; Uhl-Bien and Arena 2018) and developing adaptive responses to adverse situations (Redman 2005; Parmak 2015; Barasa et al. 2018; Martin 2021). The quality of squadron brief and debrief practices is strongly connected to the learning factor.

The connectedness factor in 6FORT encompasses interpersonal relationships and organisational belonging, aligning with concepts such as unit cohesion and social support in military contexts (Mudrack 1989; Sampson et al. 1997; Bailey et al. 2018). It highlights the role of strong inter-group relationships in enhancing confidence, efficacy and resilience at both individual and group levels (Bandura 1977; Lengnick-Hall et al. 2011). These dynamics influence how squadron members connect and collaborate during routine operations and critical missions. The factor also includes aspects of organisational connections, referred to as ‘place attachment’ in CCRAM research (Leykin et al. 2013). This involves shared values, identification of guiding principles that enhance performance during challenges (Altman-Dauttoff 2001; Coutu 2001), a sense of belonging (Jaitli and Hua 2013; Lahad 2017; Shakespeare-Finch and Daley 2017) and the ability to contribute meaningfully to the organisation (Masten and Obradovic 2008; Everly 2011). By fostering interpersonal bonds and connections to the squadron, this factor strengthens confidence, perceived capability (Lengnick-Hall 2010; Powley and Lopes 2011) and self-efficacy (Bandura 1977) across personal and group levels.

Comparisons with the BRT-53 highlight shared constructs such as staff engagement, information sharing, leadership effectiveness and organisational learning, underscoring the significance of resilience dimensions across different measurement tools.

This tool aims to address gaps in military resilience literature and crisis management practices, providing a practical resource for better understanding, measuring, developing and monitoring resilience across various unit types. Whilst it primarily targets operational squadrons, flight and RPA, the authors are confident it can be adapted for use in other military domains with minor adjustments in phrasing, as it has already been tested in different IAF sectors.

The literature on OR highlights the complexity of operationalising the construct, as it encompasses multiple characteristics and is shaped by the context in which it arises. 6FORT offers a structured framework for measuring OR in military organisations, recognising the interconnection of all factors and providing a holistic view of the squadron’s resilience. The network of relationships between factors should be further explored in future studies.

Limitations of the current study include the homogeneous research population within a specific organisational domain, limiting generalisability beyond military contexts. Future research should explore diverse organisational settings and include demographic variables to understand their impact on resilience factors.

6FORT measures OR by focusing on the unit’s psycho-social aspects. However, other critical factors – such as available resources, infrastructure readiness, operational fitness and clear orders – should also be considered. Whilst these elements are essential for assessing unit readiness and will most likely affect the OR, they fall outside the scope of this tool and should be incorporated separately through squadron commanders’ knowledge of their organisation.

Methodological refinements, such as reducing questionnaire length and addressing common source method variance, are also warranted to enhance tool usability across different cultural contexts. Additionally, future studies could explore resilience at the individual level within organisational frameworks, addressing the relationships between personal resilience and OR.

This article makes significant contributions to the existing literature on OR both theoretically and practically. The development of the 6FORT introduces new insights into OR, offering validated factors essential for measuring and fostering resilience within organisations. These factors not only advance theoretical understanding but also provide a foundational framework for future research in resilience and crisis management. Moreover, the study introduces a novel methodology for quantifying OR, filling a gap in OR research methodologies historically. Through rigorous factor analysis using extensive data from the IAF over the past decade, the study ensures both internal and external validity, establishing strong connections with established OR theories and measurement tools.

For practitioners and military leaders, the 6FORT emerges as a reliable, valid and practical tool for assessing OR. It serves as a valuable instrument for evaluating resilience pre- and post-event, laying the groundwork for effective crisis preparedness and intervention initiatives within organisations. By integrating 6FORT into organisational practices, leaders can strengthen overall OR and adaptive capacity, improving performance in both routine operations and emergency situations, ultimately fostering more prepared and capable units for combat.