AI, introduced in the late 20th century, revolutionized library operations by automating tasks such as cataloging and information retrieval using rule-based algorithms to conduct keyword searches and organize data. AI technology has enabled libraries to enhance services like discovery systems, automated indexing, and resource suggestions using tools for natural language processing and machine learning (Mallikarjuna, 2024). The primary responsibility is managing vast amounts of information in physical and digital formats, as conventional approaches find it challenging to keep up with the multidisciplinary resources and scholarly publications that are growing rapidly. Furthermore, users expect more personalized (Müngen, 2024) and intuitive experiences, necessitating the provision of sophisticated search and recommendation systems (Dogan et al., 2024) in addition to basic keyword searches. AI can enhance resource discoverability and user satisfaction by employing tools like semantic search, natural language processing, and intelligent discovery platforms.

Another significant challenge for library staff is the limited time and resources available. Routine tasks such as metadata creation, resource classification, and user support are timeconsuming and distract from more strategic activities. AI applications, such as automated metadata generation and chatbots, may simplify processes, freeing employees to concentrate on higher-value work (Malakar et al., 2025). Furthermore, academic libraries must provide data-driven insights to align their searches with emerging research trends and changing user behaviors (Tomiuk et al., 2024). However, manually analyzing large datasets, such as publication trends and usage patterns, is time-consuming and error-prone.

Interest in using AI to support academic libraries has grown due to recent technological advancements and rising demand for efficient, user-centered library services. A few notable trends include the use of NLP-based chatbots to interact with users (Li & Coates, 2025; Nguyen et al., 2024), data mining to improve data management (Vasishta et al., 2024), intelligent recommendation systems to integrate information retrieval and personalized AI learning support (Mabona et al., 2024). In addition to meeting the demands of academic communities today, these lead the way for a future in which AI will be an essential component of library administration (Torres, 2024), resulting in a flexible and intensely engaging learning environment (Deschenes & McMahon, 2024). Libraries can improve their collections to better serve their communities by using AI-powered collection management technologies that examine user preferences (Kaushal & Yadav, 2022), citation trends, and circulation patterns (Senthilkumar et al., 2024). These systems estimate demand for specific material types, suggest new acquisitions, and identify resources that may no longer be relevant using data mining algorithms (Ali et al., 2024). By enhancing the value of their collections and enabling data-driven purchasing decisions (Cox, Pinfield, et al., 2019), this approach also ensures that libraries remain active and user-friendly.

Research on bibliometric analysis plays a vital role in tackling these challenges. Additionally, bibliometric analysis can guide the strategic implementation of AI by highlighting key technologies and applications relevant to academic libraries (Mukherjee & Basak, 2024; Yumnam & Charoibam, 2024). For instance, by understanding trends in natural language processing or data mining, libraries can invest in tools that meet their users’ needs (Kaushal & Yadav, 2022). Artificial intelligence (AI) is being increasingly explored as a transformative tool in library services, and academic libraries can enhance user experiences and address operational challenges, ensuring they remain vital hubs for innovation and knowledge exchange (Adewojo et al., 2024; Barsha & Munshi, 2024).

Bibliometric analysis serves as an effective method for examining scholarly literature, particularly in understanding the development and influence of artificial intelligence (AI) applications and tools within academic libraries (Borgohain et al., 2024). By utilizing databases like Scopus, researchers can tap into a vast collection of published articles, enabling a systematic evaluation of trends, prominent authors, significant journals, and contributions from various institutions in this area (Hussain & Ahmad, 2024). This method highlights the growth of AI applications in library environments and the wider effects these tools have had on the academic information landscape. Indicators such as citation analysis, publication volume, and co-authorship patterns offer quantitative insights into scholarly engagement with AI technology in academic libraries (Khan et al., 2023).

Doing a bibliometric analysis of academic research on AI tools and applications in academic libraries is the driving force behind methodically investigating the scholarly landscape of this quickly developing field. The study attempts to clarify how AI has improved library efficiency and functionality while identifying future directions, implementation opportunities, and current research gaps by looking at trends, significant advancements, and thematic focuses over the last ten years. Five research questions will be the main focus of the bibliometric analysis:

- RQ1:

What have been the primary advancements in academic library research on AI tools and applications over the last 10 years?

- RQ2:

Whose articles in this discipline have the greatest impact, and whose authors are the most influential?

- RQ3:

Which academic libraries are at the forefront of AI research, and how has their role changed over time?

- RQ4:

What are the main co-authorship patterns, and how are collaborative networks organized when researching AI applications in libraries?

- RQ5:

What thematic clusters and emerging trends can be identified from bibliometric analysis of AI in academic libraries?

This study will significantly enhance academic libraries’ understanding of AI tools and applications. It will first summarize the academic environment thoroughly, looking at the most influential research and authors influencing the field. This is essential for scholars and practitioners looking to expand on current knowledge. Secondly, it will highlight innovative areas and demonstrate how AI technologies have been used to enhance library services. Third, by mapping collaboration networks, the study will promote global partnerships by highlighting top institutions and areas at the leading edge of AI research in libraries. Finally, the analysis will identify new trends and gaps in the literature, directing future studies and empowering libraries to deploy AI solutions to meet changing user needs strategically. Bibliometric analysis is a tool for understanding how AI is used in academic libraries and guiding future research and advancement in this crucial field. This research will assist in shaping the next generation of AI-driven library services by uncovering key insights.

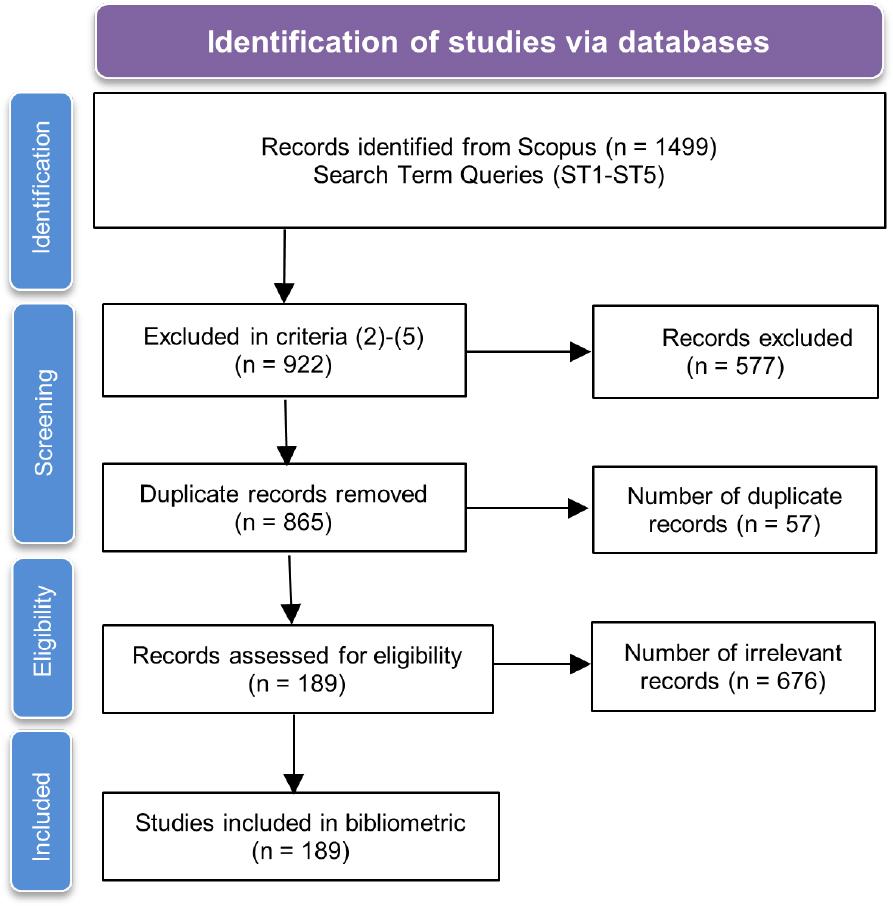

This study uses two different approaches: a systematic review and a bibliometric analysis. The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis) guarantees a systematic and transparent review process protocol (Page et al., 2021) (Figure 1), and The academic literature on the application of AI in academic libraries during the past ten years is comprehensively reviewed by the bibliometric analysis. Applying the PRISMA protocol (Moher et al., 2015) in Figure 1 divided the review process into four key phases: identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion. During the identification stage, a comprehensive search of the Scopus databases was conducted using targeted search queries (ST1-ST5). Only papers published in peer-reviewed journals between 2014 and 2024 were included in the search. After eliminating duplicate records, the articles were screened based on their abstracts and titles. Articles that did not have enough context or AI-driven innovations in academic libraries or that did not concentrate on an academic library setting were eliminated. A more comprehensive examination of the full-text articles was part of the eligibility phase to ensure that they were pertinent to the study’s objectives. The final set of studies included in the bibliometric analysis was chosen during the inclusion phase.

Data filtering and screening using PRISMA flowchart.

The results of searches in the Scopus database were evaluated, and the VOSviewer (van Eck & Waltman, 2009) tool was used to analyze the data. The methodology will involve five key steps: The research structure presents five steps, as detailed in Figure 2. The first step corresponds to data collection; five criteria were used for data extraction (Table 1), i.e., (i) search in article title, abstract, keywords, (ii) document type of article and conference paper, (iii) only English language paper, (iv) final publication stage, and (v) period during 2014-2024. The database download in Scopus, dated October 2024, had the following search formula in Table 1. Therefore, 1,499 records were retrieved. The second step checks for duplicates with the Boolean Expression in five research category (RC) criteria and search term queries (Table 2). Based on the chosen terms, 922 documents were obtained. After removing 57 duplicates, the search was reduced to 865 papers. Following the exclusion criteria, 676 records were excluded as irrelevant. Thus, 189 papers eligible for this review were approved. This was analyzed in detail in the fourth step, “inclusion,” and was considered entirely relevant, forming this study’s sample. At the end of this step, appropriate data were extracted and exported in CSV file format. Citations, bibliographical information, abstract, keyword fields, and references are all included in the download. In the third step, 189 scientific publications were gathered and incorporated into the pre-existing bibliometric analysis. The third step is to employ detailed bibliometric analysis: content analysis, keyword analysis, citation analysis, co-authorship analysis, and descriptive analysis. The data analysis in the fourth step included three software applications, i.e., Microsoft Excel365, VOSviewer, and Rstudio (Bibliometrix (Aria & Cuccurullo, 2017) Rpackage and Biblioshiny function), to analyze and visualize the findings. In the fifth step, “interpretation and discussion,” 189 records have studied the findings, identified trends and patterns, highlighted significant contributions, and proposed future research directions.

Outline of the research methodology.

Summary of research category with search term queries criterion.

| Research Category | Linked RQs | Justification of Search Term (ST) Queries | Search Term (ST) Queries |

|---|---|---|---|

| RC1: AI-Based Library Services | RQ1, RQ4, RQ5 | This category focused on AI tools used in front-facing library services such as cataloging, virtual assistants, book recommendations, and chatbots. The search string ST1 emphasizes keywords like library catalog, AI-powered services, virtual assistant, and chatbot, highlighting efforts to automate and enhance user service delivery within academic libraries. | ST1: (AI AND librar* catalog* OR academ* librar*) OR (AI AND librar* service* OR chatbot* OR virtual* assistant*) OR (AI-power* book recommen* OR person* service* AND librar*) |

| RC2: AI and User Experience in Libraries | RQ1, RQ4, RQ5 | ST2 captures research on how AI impacts user behavior, personalized content delivery, and digital user experience. Key phrases include user behavior, AI-enhanced user experience, and personal content. This aligns with studies analyzing how AI shapes patron engagement, interface design, and satisfaction within academic libraries. | ST2: (user* behav* AND AI OR mach* learn* AND librar*) OR (infoma* retriev* AND AI OR digital* librar*) OR (AI-enhanc* user* experie* OR personal* content* OR academ* resour*) |

| RC3: AI for Collection Management | RQ3, RQ4, RQ5 | This search string (ST3) explores the application of AI in managing and analyzing digital assets, predictive analytics, document digitization, and resource curation. Phrases like digital asset management, predictive analytics, and collection development focus on back-end library functions such as digital archiving, metadata classification, and trend-based resource planning. | ST3: (digital asset managem* AND AI OR mach* learn* AND lbirar*) OR (resource* curati* AND classificat* OR predictiv* analytic* AND academ* collect*) OR (predictv* analytic* AND collecti* develop* OR librar* managem*) OR (docum* digitiz* AND AI OR image* recognit* AND universit* archive*) OR (trend* analys* AND collect* enhance* OR librar* collecti* AND AI) |

| RC4: AI in Library Information Security and Data Management | RQ2, RQ4, RQ5 | In academic libraries, ST4 acknowledges the literature that discusses AI’s function in cybersecurity, data integrity, anomaly detection, and user authentication systems. The literature covers anomaly detection, AI-enabled security, and data privacy. Understanding how libraries safeguard their digital spaces and private data about AI technologies requires knowledge of this field. | ST4: (data privacy* OR securit* OR encrypt* AND AI OR mach* learn* AND librar* system*) OR (anomaly* detect* OR data securit* AND academ* librar*) OR (user authentica* OR AI-enhance* securit* AND academ* librar*) OR (anamaly* detect* AND user access OR data integrit* AND academ* librar*) |

| RC5: AI for Research and Academic Support in Libraries | RQ1, RQ3, RQ4, RQ5 | Studies on artificial intelligence tools support research activities, automated literature reviews, natural language processing, plagiarism detection, and research data management captured by ST5. This group captures the increasing integration of artificial intelligence into academic integrity tools, citation checking, resource discovery, and scholarly support services. | ST5: (literature* review* automat* AND AI OR natur* lang* process* AND resear* librar*) OR (resear* data manage* AND mach* learn* OR AI-drive* analy* AND librar*) OR (plagia* detect* AND citat* check* OR academ* integri* AND univers* librar*) OR (digit* content* analy* AND AI OR mach* learn* AND academ* resource*) OR (mach* learn* AND resource* discov* OR digit* librar* collect* AND AI) |

Papers found in Scopus until October 2024.

| Record Identified | Search Term | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ST1 | ST2 | ST3 | ST4 | ST5 | |

| (1) Scopus searches within article title, abstract, keywords | 417 | 205 | 105 | 480 | 292 |

| (2) Document type criteria (article, conference paper) | 301 | 163 | 71 | 371 | 183 |

| (3) Only English Language | 400 | 203 | 100 | 465 | 282 |

| (4) Publication stage: Final | 384 | 204 | 102 | 473 | 286 |

| (5) Period: 2014-2024 | 386 | 174 | 103 | 449 | 262 |

| Number of articles that have been included in criteria (1)-(5) | 237 | 134 | 64 | 334 | 153 |

| Number of articles retrieved | 922 | ||||

| Duplicate articles removed | 57 | ||||

| Papers irrelevant to the research topic and research aim were removed | 676 | ||||

| Total number of articles in the bibliometric studies | 189 | ||||

Papers deemed irrelevant to the research topic and aim were excluded during the eligibility screening stage to ensure the integrity and thematic alignment of the bibliometric dataset. Although the initial search queries (ST1-ST5) were designed to be inclusive and comprehensive, they also retrieved publications that mentioned AI or library-related terms without explicitly addressing the integration, application, or conceptual discussion of AI in academic library contexts. Reasons for excluding irrelevant papers (n=676) are shown in Table 3.

Summary of the criteria for irrelevant record exclusion.

| Exclusion Category | Description |

|---|---|

| Library Context Mismatch | Emphasized school and public libraries over academic ones |

| Superficial Keyword Use | Included keywords that were not thematically relevant (e.g., AI, library) |

| Domain Irrelevance | Applications of AI outside of libraries (e.g., health, robotics, engineering) |

| Non-AI Focus | Discussed digital tools or systems that do not involve machine learning or artificial intelligence |

| Non-Analytical Content | Theoretical works devoid of models or data |

| No Library Focus | Discussed educational technology that has nothing to do with the services or operations of libraries |

Only studies that significantly advanced our understanding of AI-driven innovations, applications, services, or research discourse in academic libraries were retained to preserve methodological rigor and relevance to the research questions. The final dataset of 189 articles has been filtered to reflect the intellectual landscape under analysis accurately.

In response to RQ1, the past decade’s publication trends will be examined, emphasizing growth rate, publication patterns, and theme progression. RQ2 finds the field’s most productive and highly referenced authors and the most cited articles and examines their impact on subsequent research. RQ3 identifies the top-producing institutions and their contributions to the field and the collaboration links between them to understand knowledge transfer and dissemination trends better. RQ4 findings responded to a co-authorship network to visualize collaborative links between organizations and authors, locating groups of organizations and productivity mapping of items by country. RQ5 identifies underrepresented or underexplored study topics and provides relevant research directions for future investigations.

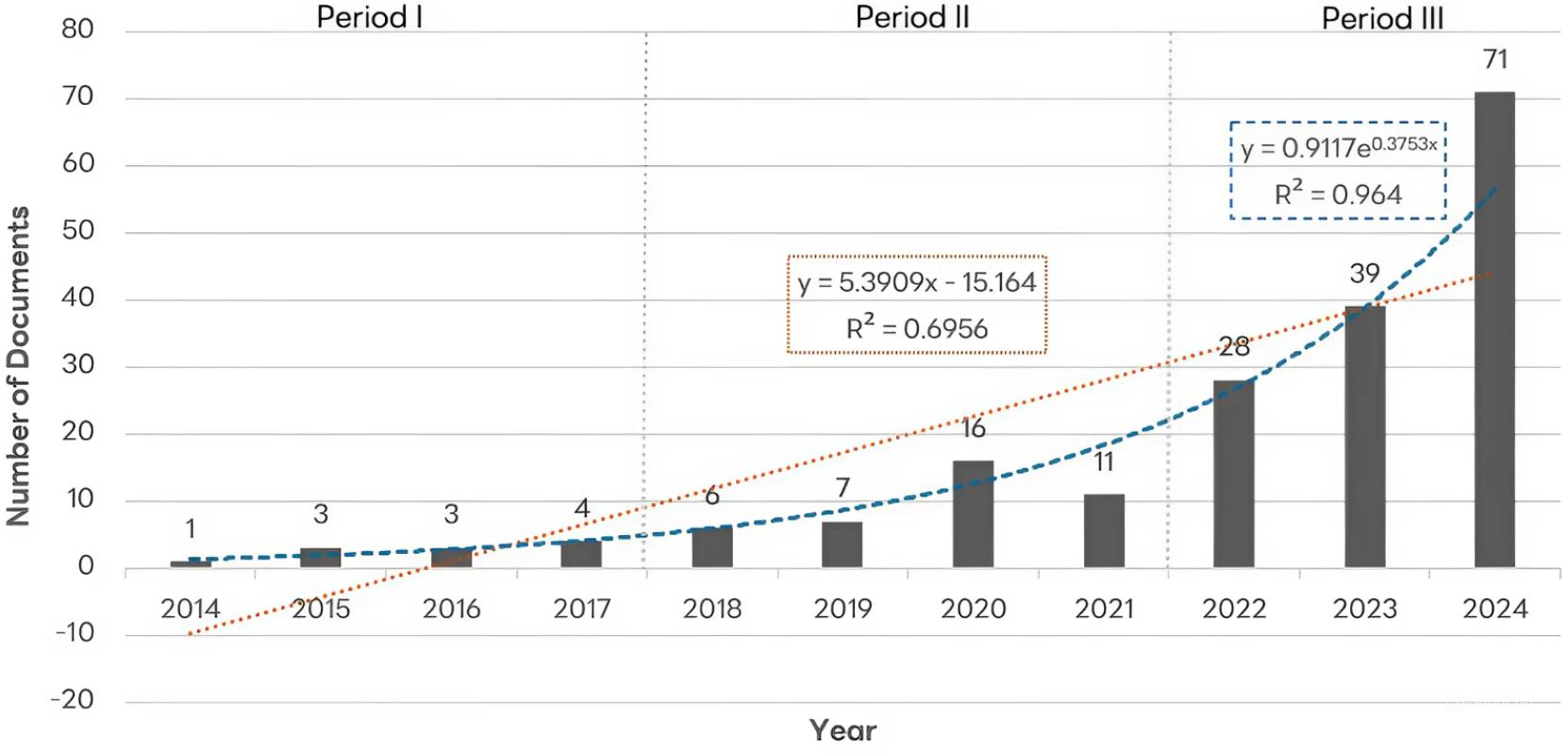

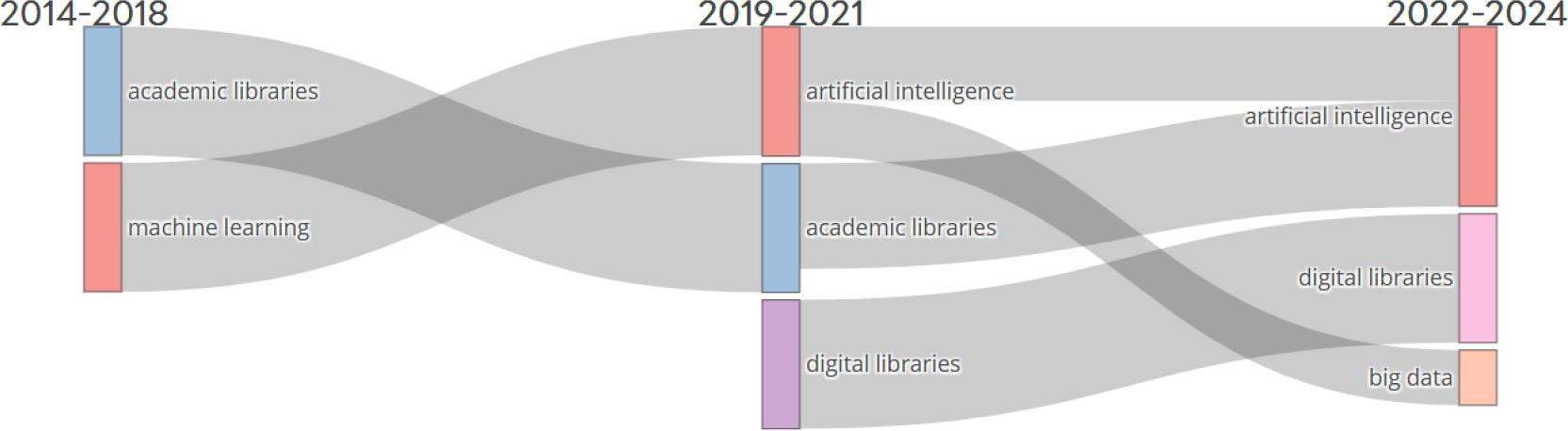

Figure 3 illustrates the increase in scientific output between 2014 and 2024, broken down into three years: 2014-2017 (Period I), 2018-2021, and 2022-2024. The bar chart displays the number of documents published annually, while linear and exponential trend lines reveal changes in growth patterns. The first trend line is a linear regression line with the equation of the type y = 5.3909x – 15.164 and a coefficient of determination R2 = 0.6956. The second trend line is an exponential regression line with the equation of the type y = 0.9117e0.3753x and a coefficient of determination R2 = 0.964. The exponential productivity curve’s value (R2 = 0.964) was more significant than the linear value (R2 = 0.6956), indicating that according to both equations’ coefficient of determination (R2), the study topic is in an exponential development phase.

Annual growth trend on AI applications and tools in academic libraries from 2014 to 2024.

According to the curve’s behavior, the 189 documents produced by the scientific community during ten years (2014-2024) are separated into three periods: introduction, development, and maturity (Figure 3). The number of documents is displayed on the y-axis, and the years are represented on the x-axis. Period I (2014-2017), Period II (2018-2021), and Period III (2022-2024) are the three time periods into which the graph is divided.

The number of documents stayed steady and comparatively small; 2014 saw one, 2015 and 2016 saw three, and 2017 saw four. Eleven papers with 116 citations were published during this time, accounting for 0.06% of the total output in this field of study. The most cited articles were “Content based image retrieval based on geo-location driven image tagging on the social Web” (Memon et al., 2014), published in 2014 with 25 citations, followed by an article published in 2016 by (Khabsa et al., 2016), with 21 citations in all ACM/IEEE Joint Conference on Digital Libraries proceedings. Exploratory studies marked this period focused on developing theoretical frameworks for academic libraries (Dabbour & Kott, 2017; Ellern et al., 2015; Zhu et al., 2016), academic search (Khabsa et al., 2016), and proof-of-concept applications in libraries, i.e., linked open data (Sateli et al., 2017), visual analytics (Ventocilla & Riveiro, 2017), behavior analytics (Fernandez & Ponnusamy, 2015), and using AI applications and tools in libraries, for example, recommendation system (Beel et al., 2017; Chadha & Kaur, 2015), data mining, machine learning, and natural language processing (Bohra et al., 2015; Sateli et al., 2017). This foundational stage was critical for laying the groundwork and creating a foundation for subsequent growth.

There is a gradual increase in the number of documents, with 6 in 2018, 7 in 2019, and peaking at 16 in 2020 before slightly dropping to 11 in 2021. Forty papers were published. The most cited article was “The Intelligent Library: Thought Leaders’ Views on the Likely Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Academic Libraries” (Cox, Pinfield, et al., 2019), published in 2019 with 141 citations in Library Hi Tech, followed by the article “UTAUT as a Model for Understanding Intention to Adopt AI and Related Technologies among Librarians” (Andrews et al., 2021) published in 2021 with 77 citations in the Journal of Academic Librarianship. During this period, research likely expanded into perceptions and awareness of artificial intelligence in managing academic libraries (Abayomi et al., 2021; Hervieux & Wheatley, 2021), including AI tools and perspectives of academic librarians (Ali et al., 2020; Wheatley & Hervieux, 2020). There are early natural language processing tools (Wang et al., 2020), linked data integrated with AI in the transformation of library services (Schreur, 2020), enhanced digital libraries with book recommendation systems (Nugraha et al., 2020), and data mining approach that emerged in the library collection and services (Friedman et al., 2021; Giannopoulou & Mitrou, 2020; Li & Daoutis, 2021; Patel et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020).

Although the number of documents slightly dropped to 11 in 2021, the publications addressed critical topics, reflecting the growing interest in and adoption of advanced technologies within academic and public libraries globally. One of the most highly cited works, “Awareness and Perception of the Artificial Intelligence in the Management of Academic Libraries in Nigeria” (Abayomi et al., 2021), has 23 citations. This study explored how librarians in Nigeria perceive and adopt AI technologies, highlighting gaps in awareness and challenges to implementation. Its high citation count underscores the relevance of AI adoption in developing regions. Similarly, the 42-citation paper “Perceptions of Artificial Intelligence: A Survey of Academic Librarians in Canada and the United States” (Hervieux & Wheatley, 2021) offered information on how academic librarians in North America were utilizing AI in their work. This study is highly cited because it highlighted the value of virtual assistant technologies and training in enhancing library services. The paper “Using AI/Machine Learning to Extract Data from Japanese American Confinement Records” discussed the use of AI in digital collections and archives (Friedman et al., 2021). This study illustrated AI’s multidisciplinary reach in libraries by showcasing the real-world implementation of machine learning to enhance archival data accessibility.

The 2021 publications place a particular emphasis on using AI, data mining, and machine learning to address emerging technologies in academic libraries. These studies concentrate on awareness, perceptions and practical applications, highlighting the field’s transition to digital transformation and user-centered innovations. The high citation counts of individual works demonstrated their major impact on subsequent studies and the rising understanding of technology’s role in changing library systems around the world.

Between 2022 and 2023, the number of research articles grew rapidly from 28 to 39 and 71, respectively. The paper “Artificial Intelligence (AI) Library Services Innovative Conceptual Framework for the Digital Transformation of Academic Education” (Okunlaya et al., 2022), which had 96 citations, is one of the highlights. There are also 92 citations in the paper “The CLEAR path: A framework for enhancing information literacy through prompt engineering” (Lo, 2023). Research on AI, data mining, machine learning, and cutting-edge technology for libraries and information management achieved tremendous breakthroughs in 2022. Twenty-eight papers covering a range of topics, from digital transformation strategies to AI-powered library services, have added to this growing body of knowledge. The fact that these papers received 366 citations shows how important and current they represent.

The significance of investigating how AI might change academic libraries was underlined by one of the most frequently cited publications in (Okunlaya et al., 2022). This paper established a thorough framework for applying AI to enhance library services, engage with initiatives for digital transformation, and address evolving needs in education. Thirty-seven citations were included in another interesting study that examined librarians’ attitudes and capability to use AI technologies (Yoon et al., 2022). These results made AI a valuable tool for professionals and researchers, highlighting the need for training and addressing reservations about integrating it into library operations. With 39 citations, (Kaushal & Yadav, 2022) showed increasing interest in conversational AI and its uses to increase service efficiency and optimize user interactions. As libraries adapt to the needs of patrons in the digital age, chatbots are becoming popular. This study concentrated on the practical implications of implementing them in libraries.

The articles by (Ajani et al., 2022) (25 citations) and (Rodriguez & Mune, 2022) (25 citations) illustrated how AI technologies are applicable globally in a range of institutional and geographic situations. These studies highlighted the difficulties and advantages of applying AI solutions, automated processes, and virtual reference tools in educational contexts. Additionally, by offering state-of-the-art computational techniques for data analysis, content management, and user interaction, the article in (Wang, 2022) explored the innovative application of data mining and expanded the boundaries of traditional academic libraries (Thornley et al., 2022). Emerging concerns included the moral implications of applying AI and cutting-edge information extraction methods for conserving cultural collections, as illustrated in (Bergamaschi et al., 2022).

Publication in AI and its library applications increased significantly in 2023. Thirty-nine articles (346 citations) showed a wide range of interest and influence in areas from ChatGPT applications to AI integration in library workflows. For example, the 26-citation study in (Houston & Corrado, 2023) highlighted its impact on the discussion of generative AI in academic library environments. Similarly, (Brzustowicz, 2023) (9 citations) investigated how AI could transform cataloging systems. Publications from 2023 also emphasized the beneficial use of AI in libraries. The contribution of ChatGPT to enhancing educational environments was examined in another highly cited paper in (Vargas-Murillo et al., 2023) (28 citations), indicating its multidisciplinary applicability in libraries and education. In (Narendra et al., 2025) and (Jha, 2023), the potential of AI to enhance user services and expedite library operations was examined. These studies demonstrated how AI can solve operational problems and increase user satisfaction. For example, In (Clark & Lischer-Katz, 2023) highlighted the challenges associated with implementing AI in libraries. In (Sala, 2023) explored innovative uses of AI beyond traditional domains emphasizing the use of data mining and natural language processing systems to enhance the accessibility of multilingual content.

With 71 articles, research on artificial intelligence and its use in academic libraries increased significantly in 2024. The study covered a wide range of subjects, such as the use of AI in library services, user-centered innovations, ethical issues, and recent developments in generative AI tools. While some articles were highly cited, others, as is common with recent publications, have yet to receive considerable citations. The use of AI-powered adaptive systems for customized library services was a common theme (Sowmiya et al., 2024). AI and machine learning technologies can enhance library services and streamline operations when put into practice (Bhattacharya, 2024). As AI capabilities proliferate in the creative industries, this issue becomes increasingly important.

ChatGPT was one of the generative AI technologies that was discussed significantly in (Torres, 2024). Another interesting study emphasized the importance of AI literacy among librarians and the necessity of training to optimize the effective use of generative AI technology (Lo, 2024). The creative industry makes greater use of AI tools. (Liu et al., 2024) looked at the transparency and ethical concerns with AI-powered search engines, highlighting the importance of responsibility in both their creation and application. The literature makes considerable use of generative AI technologies, including ChatGPT, and explores how they could be useful for tasks like virtual assistance, instructional design, and content generation. Another significant study in (Lo, 2024) focused on the significance of AI literacy among librarians and emphasized the role of training in enhancing generative AI methods. Research on the application of AI in African academic libraries with a particular emphasis on regional and global perspectives was conducted by (Alam et al., 2024). This pattern emphasizes AI’s worldwide applicability and capacity to solve regional academic library issues. Some studies, such as (Harisanty et al., 2024) (45 citations), stood out despite the variety of topics because of their high citation counts, proving their substantial impact on the scholarly community. This work reflects the growing awareness and interest in AI among key stakeholders in the library sector.

Table 4 highlights the bibliometric trends in publications and citations in library science research, focusing on AI and related technologies, from 2014 to 2024. Over this decade, total publications increased significantly, from just one in 2014 to 71 in 2024, showcasing this field’s growing interest and relevance. Similarly, total citations rose from 25 in 2014 to 150 in 2024, although the pattern of citation accumulation varied significantly across years. Total citations per year show a steep increase, particularly in recent years, peaking at 968 in 2024, demonstrating the rising impact of recent publications. However, Mean Total Publications (Mean TP) and Mean Total Citations (Mean TC) illustrate fluctuating trends, reflecting changes in the quality and focus of research over time. Mean TP peaked in 2014 at 25 due to the low volume of publications, while Mean TC steadily increased, reaching its highest value of 13.63 in 2024, suggesting a shift towards impactful and widely cited works in recent years.

Annual publication and citation of AI in academic libraries (2014 to 2024).

| Year | Total Publications | Total Citations | Total Citations per Year | Mean TP | Mean TC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 1 | 25 | 0 | 25 | 0 |

| 2015 | 3 | 11 | 1 | 3.67 | 0.33 |

| 2016 | 3 | 39 | 4 | 13 | 1.33 |

| 2017 | 4 | 41 | 15 | 10.25 | 3.75 |

| 2018 | 6 | 66 | 20 | 11 | 3.33 |

| 2019 | 7 | 176 | 26 | 25.14 | 3.71 |

| 2020 | 16 | 251 | 44 | 15.69 | 2.75 |

| 2021 | 11 | 155 | 63 | 14.09 | 5.73 |

| 2022 | 28 | 366 | 137 | 13.07 | 4.89 |

| 2023 | 39 | 346 | 335 | 8.87 | 8.59 |

| 2024 | 71 | 150 | 968 | 2.11 | 13.63 |

The data reveals several key patterns and insights:

Early Growth Phase (2014-2017): this period represents the foundational research stage in AI and library science, with a steady rise in the overall number of citations and publications. The total citations per year and Mean TC remained relatively low, reflecting the nascent stage of AI adoption in library science. Despite the limited number of studies, early works laid the groundwork for subsequent advancements, establishing methodologies and exploring initial applications of AI in library systems.

Expansion Phase (2018-2021): 2018 to 2021 saw a noticeable increase in publications, rising from 7 in 2019 to 16 in 2020 and 11 in 2021. Total citations per year also climbed significantly, reaching 63 in 2021, indicating the growing influence of these works. This stage aligns with the globalization of technology related to AI, such as machine learning, data mining, and natural language processing, and how these are integrated into library services. The relatively high Mean TC during this period (e.g., 5.73 in 2021) suggests that the research produced was impactful and relevant.

Acceleration Phase (2022-2024): 2022 to 2024 marks a dramatic expansion in total publications and total citations per year, with 71 publications in 2024 and 986 citations per year. Although the Mean TP dropped to 2.11 in 2024 due to the sheer volume of new publications, the Mean TC reached its highest value (13.63), signifying the increasing influence of individual works. The exponential growth in citations affects the broad recognition and adoption of AI technologies like ChatGPT, generative AI, and data mining in library science. The sharp rise in total citations per year in 2024 suggests a shift toward timely and practical research addressing real-world challenges, such as AI-driven personalization, ethical AI use, and digital transformation in library systems.

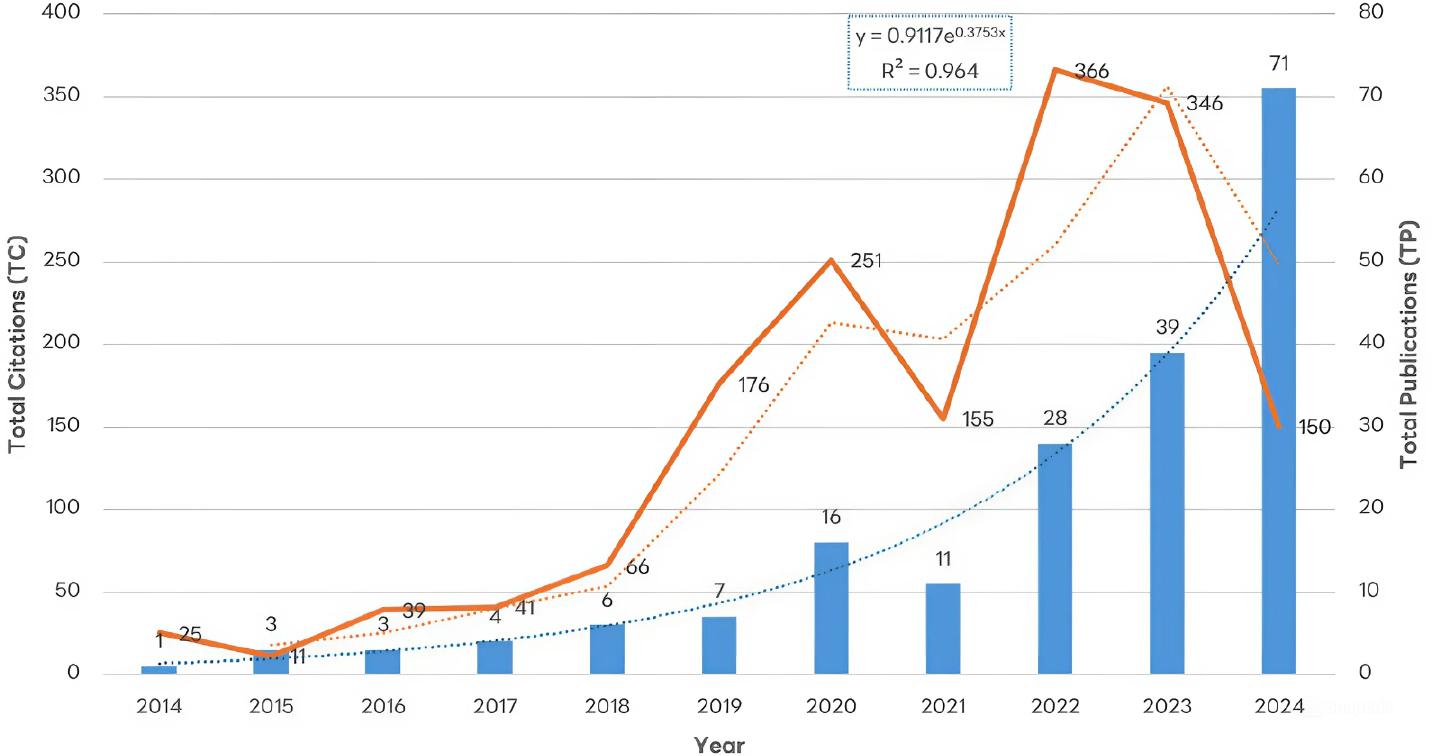

Total Publications (TP) and Total Citations (TC) trends from 2014 to 2024 are shown in Figure 4, demonstrating the expansion and significance of AI and academic library research. The blue bars represent the steady increase in TP, from only one publication in 2014 to 71 publications in 2024, reflecting a significant rise in research activity. Conversely, the orange line shows fluctuations in TC, with peaks in 2020 (251 citations) and 2022 (366 citations) before declining slightly to 150 citations in 2024.

The dynamic evolution of research output and its citation impact over time.

The overall trend indicates exponential growth in research output (TP), as evidenced by the exponential trendline with an R2 of 0.964. This steady increase in publications aligns with AI technologies’ growing relevance and application in library science. However, the total citations (TC exhibit variability, with significant peaks in 2019-2022, suggesting that the research produced during these years had a substantial influence. The notable decline in TC from 2023 to 2024 may reflect the “citation lag” effect, as recent publications have not yet accumulated significant citations.

The result reveals three key patterns:

Initial growth (2014-2017): A slow increase in TP and TC, reflecting foundational work in AI and its exploratory applications in library science.

High-Impact Phase (2018-2021): A sharp increase in citations indicates that publications from this period addressed pressing challenges and introduced innovative technologies. Key topics like data mining, machine learning, ChatGPT, and ethical AI likely contributed to the high citation impact.

Recent expansion (2022-202): The exponential Growth in publications highlights the field’s maturity and widespread interest in implementing AI in libraries. However, the decline in TC suggests a temporary lag as recent studies gain recognition.

The growth in TP signifies increasing interest and investment in the field, but the variability in TC highlights the challenge of maintaining consistent research impact amidst the surge in output.

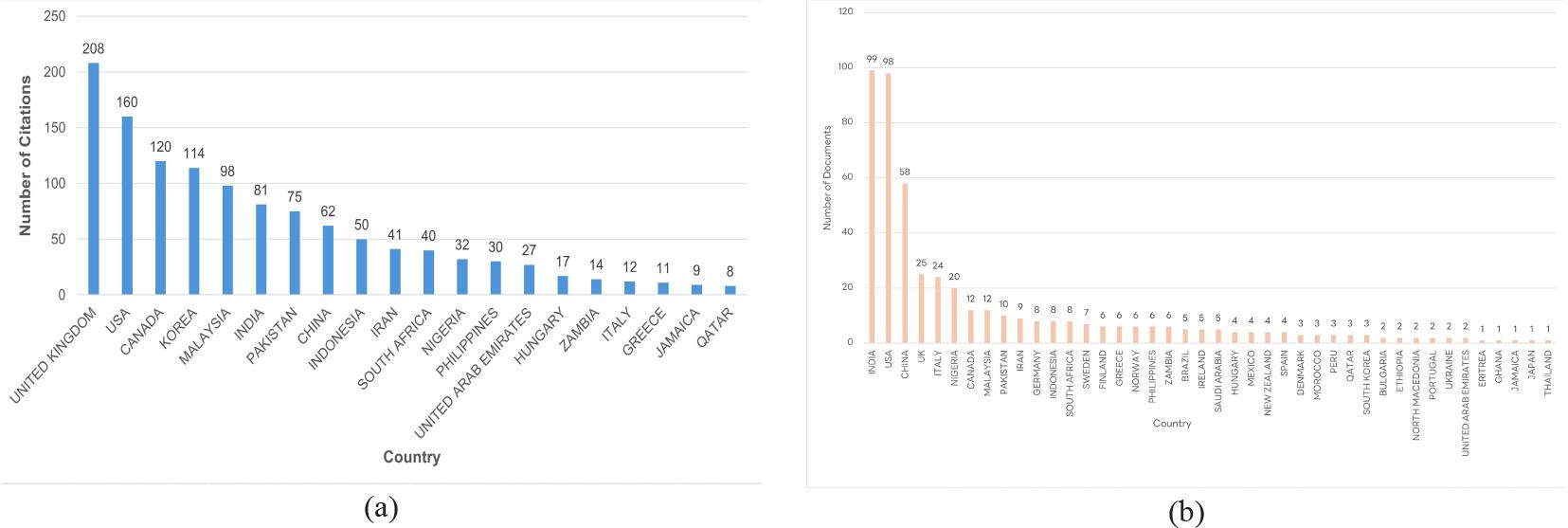

The two graphs (Figure 5(a), 5(b)) highlight the distribution of citations and publications by country, showcasing the research’s global contribution and impact on AI in academic libraries.

Country contributions to citations and publications from 2010 to 2024, (a) total number of articles published by country, (b) total citations by country.

Figure 5(a) presents the number of citations by country, with the United Kingdom leading at 208 citations, followed by the USA (160), Canada (120), Korea (114), and Malaysia (98). These top-performing countries demonstrate significant influence in the field, with their publications garnering wide recognition. Countries like India, Pakistan, and China also have notable citation counts, ranging between 75-81 citations, suggesting the emerging influence of AI applications in libraries. Figure 5(b) shows the number of publications by country. India and China are the leading contributors, with 99 and 98 publications, respectively, followed by the USA (58), Italy (25), and the UK (24). These figures highlight India’s and China’s significant research activity in the field; however, compared to nations like the USA and the UK, their citation impact is comparatively low.

The graphs reveal an essential distinction between research output and impact. Despite being major contributors, nations like China and India do not have the same impact on research as their output. This can indicate that their work is still gaining recognition and that they are focusing more on local or regional issues. However, there is a substantial correlation between the output and effect of countries, i.e., the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom, suggesting that their research is important and well-known. Smaller countries of Malaysia, Korea, and Pakistan have a big influence on citations while having fewer publications. This demonstrates how excellent and relevant their work is and highlights the significance of carrying out important research that addresses global concerns in academic libraries and AI. The results also show the growing participation of countries from different regions including South Africa, Nigeria, and Zambia. This trend demonstrates the global applicability of AI in resolving issues faced by academic libraries as well as its potential to address particular concerns in emerging nations.

Table 5 displays the top 15 most cited articles during the specified period, with the article “The intelligent library: Thought leaders’ views on the likely impact of artificial intelligence on academic libraries” by Cox, A.M., Pinfield, S., and Rutte, S. at the top of the list with 141 citations out of the 189 scientific documents that were examined.

Top 15 most cited documents on AI applications and tools in academic libraries.

| Title | Authors | Journal | Total Citations | TC per Year | Normalized TC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The intelligent library: Thought leaders’ views on the likely impact of artificial intelligence on academic libraries | Cox, Pinfield, et al. (2019) | Library Hi Tech | 141 | 20.14 | 5.61 |

| Artificial intelligence (AI) library services innovative conceptual framework for the digital transformation of university education | Okunlaya et al. (2022) | Library Hi Tech | 96 | 24.00 | 7.34 |

| The CLEAR path: A framework for enhancing information literacy through prompt engineering | Lo (2023b) | The Journal of Academic Librarianship | 92 | 30.67 | 19.37 |

| UTAUT as a Model for Understanding Intention to Adopt AI and Related Technologies among Librarians | Andrews et al. (2021) | The Journal of Academic Librarianship | 77 | 15.40 | 5.46 |

| Artificial intelligence in academic libraries: An environmental scan | Wheatley & Hervieux (2020) | Information Services & Use | 61 | 10.17 | 3.89 |

| Artificial intelligence tools and perspectives of university librarians: An overview | Ali et al. (2020) | Business Information View | 54 | 9.00 | 3.44 |

| Perceptions toward Artificial Intelligence among Academic Library Employees and Alignment with the Diffusion of Innovations’ Adopter Categories | Lund et al. (2020) | College & Research Libraries | 46 | 7.67 | 2.93 |

| Leaders, practitioners and scientists’ awareness of artificial intelligence in libraries: a pilot study | Harisanty et al. (2024) | Library Hi Tech | 45 | 22.50 | 21.30 |

| How artificial intelligence might change academic library work: Applying the competencies literature and the theory of the professions | Cox (2023) | Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology | 42 | 14.00 | 4.73 |

| Perceptions of artificial intelligence: A survey of academic librarians in Canada and the United States | Hervieux & Wheatley (2021) | The Journal of Academic Librarianship | 42 | 8.40 | 2.98 |

| The Role of Chatbots in Academic Libraries: An Experience-based Perspective | Kaushal & Yadav (2022) | Journal of the Australian Library and Information Association | 39 | 9.75 | 2.98 |

| Perceptions on adopting artificial intelligence and related technologies in libraries: public and academic librarians in North America | Yoon et al. (2022) | Library Hi Tech | 37 | 9.25 | 2.83 |

| Readiness of academic libraries in South Africa to research, teaching and learning support in the Fourth Industrial Revolution | Ocholla & Ocholla (2020) | Library Management | 35 | 5.83 | 2.23 |

| Exploring the implementation of artificial intelligence applications among academic libraries in Taiwan | Huang (2024) | Library Hi Tech | 34 | 17.00 | 16.09 |

| Artificial intelligence (AI) application in library systems in Iran: A taxonomy study | Asemi & Asemi (2018) | Library Philosophy and Practice | 29 | 3.63 | 2.64 |

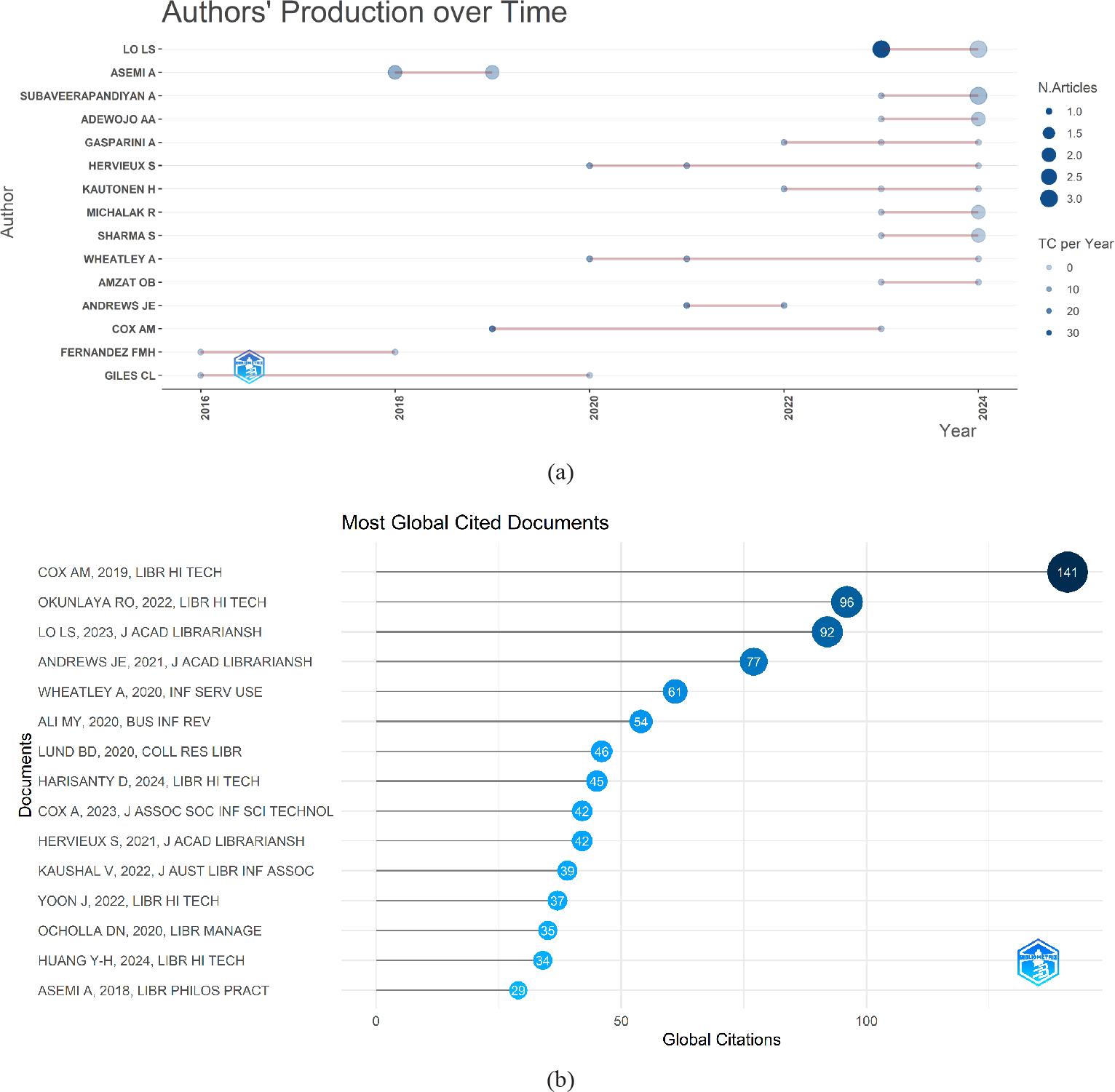

Figure 6(a) visualizes individual authors’ publications over the last decade. The horizontal lines represent each author’s active publishing span. Circle size indicates the number of articles published yearly, while the color intensity reflects the total citations (TC) per year. The chart displays the scholarly contributions of 16 key authors in the domain of AI in academic libraries between 2014 and 2024. Authors such as LO LS and ASEMI A appear as recent yet prolific contributors, with LO LS showing both high output and notable citation impact in recent years. In contrast, authors like GILES CL and FERNANDEZ FHM have earlier publications (as early as 2015) but show limited activity in recent years, suggesting earlier influence or foundational contributions.

Performance graph of the top 15 most productive authors from 2014 to 2024. (a) Author’s production over time; (b) top 15 most globally cited documents.

This visual distinction between publication volume and impact is especially informative: darker blue bubbles (e.g., LO LS in 2024) denote higher publication counts and annual citation rates, indicating influential and recent engagement. Meanwhile, lighter-colored circles, such as those for HERVIEUX S or GASPARYAN S, indicate a moderate volume of publications with limited citation traction. This pattern reflects broader library and information science trends, where rapid technological integration, particularly through AI tools like chatbots, predictive analytics, and NLP, has triggered fresh research interest and interdisciplinary collaboration. Authors with consistent contributions (e.g., COX AM, SHARMA S) may represent bridge figures between early conceptual work and current empirical studies. The limited citation impact for some authors with multiple publications may reflect the field’s still-maturing citation lifecycle or the varying visibility of publishing outlets. On the other hand, authors with fewer but highly cited works may have produced seminal or high-visibility studies.

In Figure 6(b), scholarly articles are ranked according to their total global citations. The bubble size and color intensity of each entry, which includes the authors, journal, and year of publication, indicate the quantity of citations received. This analysis clarifies the major publications impacting the field. The visualization reveals the 15 most cited publications globally in the area of artificial intelligence (AI) applications and tools in academic libraries. The leading article by Cox AM (2019) in Library Hi Tech has received 141 citations, significantly surpassing all others. It is followed by Okunlaya et al. (2022) and Lo LS (2023), with 96 and 92 citations, respectively. These three works’ larger and darker-colored bubbles indicate their most influential scholarly contributions. Citation counts gradually decrease in subsequent entries, with publications with 6128 citations indicating moderate but significant influence. The repeated engagements of journals like Library Hi Tech, Information Services & Use, and the Journal of Academic Librarianship highlight their importance in distributing AI research among libraries.

The popularity of articles published between 2019 and 2023 is consistent with the general acceleration of AI adoption in various fields, such as information management and education. Thematically, the most cited articles probably cover subjects like chatbot implementation, AI-based user services, data-driven library decision-making, and the moral ramifications of automation in academic settings. Geographic and institutional diversity in contributions is also revealed by the distribution of citations, indicating that researchers from both developed and developing contexts are driving AI research in libraries. Journal Library Hi Tech is an important channel for dissemination because it makes high-impact research visible. This also raises questions of methods: While citation count is a useful proxy for influence, it can be influenced by early article processing speed or if the highest citation papers come from highly quoted journals or self-citations. However, the data offers a strong foundation for tracing intellectual leadership across the discipline.

Table 5 lists the 15 most globally cited scholarly documents based on total citations, citation rate (TC per year), and normalized citation counts. Each entry includes title, authorship, journal of publication, and impact metrics, highlighting key contributions shaping the discourse on artificial intelligence in the academic library context. The most highly cited paper is Cox (2019), The intelligent library: Thought leaders’ views on the likely impacts of artificial intelligenct on academic libraries, with a total of 141 citations and TC/yr of 20.14. Conversely, Lo (2023) has the highest normalized citation rate (19.37), which implies its citation total is growing quickly despite only being published a short time ago, signifying that a piece of scholarship is meaningful to the academic community and suggests a growing interest in the area of inquiry. Other high-impact works include Okunlaya et al. (2022), with 96 citations, and Andrews et al. (2021), with 77, each published in highly visible journals Library Hi Tech and The Journal of Academic Librarianship. Citation velocity is an important indicator; for instance, Lo (2023) displays a TC per year of 30.67, suggesting that very recent publications are garnering attention at an accelerated rate.

The wide variety of topics among the top-cited documents suggests that AI’s integration with academic libraries is still in its infancy. The topics varying from strategic foresight and theoretical frameworks (Cox, 2019; Okunlaya et al., 2022) to empirical librarian perception studies (Ali, 2020) to adoption models (Andrews et al., 2021; Yoon et al., 2022) signify that AI research is beginning to transition from speculative inquiry to applied research and the implementation of systems. Specific journals, notably Library Hi Tech, repeatedly occupy the list of top documents, clearly establishing themselves as leading venues for scholarly conversation in this area. In addition, normalized citation values bring to light powerful but low-profile studies, providing a more comprehensive account of influence beyond total citation number. Finally, early citation momentum and relevance to practice play larger roles in an article’s impact in this rapidly emerging research field, as Lo (2023) and Huang (2024) references demonstrate, suggesting that this field values conceptual originality and practices that work.

This citation analysis verifies that a concentrated core of influential literature on AI applications within academic libraries has emerged. The data suggests that research interest around AI applications and tools in academic libraries is rapidly evolving, with newer articles achieving great impact in a short time frame. The works that have the most citations currently are foundational references that have collectively shaped both theoretical and applied understanding of AI in library environments.

Co-citation analysis reveals how frequently two sources are cited across the selected literature, providing insight into the relationships among scholarly works, the influence of specific journals or authors, and the formation of thematic clusters within the domain. Table 6 shows the top 15 scientific sources co-cited on AI applications and tools in academic libraries.

The top 15 academic libraries’ co-cited scientific sources on AI applications and tools.

| Ranking | Scientific Source | Co-Citations | Links | Total Link Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Library Hi Tech | 117 | 18 | 1247 |

| 2 | Library Hi Tech News | 100 | 17 | 836 |

| 3 | The Journal of Academic Librarianship | 66 | 17 | 712 |

| 4 | Scientometrics | 47 | 12 | 170 |

| 5 | Journal of Documentation | 34 | 17 | 485 |

| 6 | Journal of Australian Library and Information Association | 34 | 18 | 432 |

| 7 | The Electronic Library | 33 | 16 | 482 |

| 8 | Journal of Library Administration | 33 | 17 | 319 |

| 9 | Library Management | 28 | 17 | 327 |

| 10 | College & Research Libraries | 27 | 18 | 198 |

| 11 | International Journal of Information Management | 27 | 17 | 177 |

| 12 | Information Technology and Libraries | 24 | 17 | 332 |

| 13 | Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology | 24 | 18 | 258 |

| 14 | Journal of Librarianship and Information Science | 24 | 17 | 234 |

| 15 | Business Information Review | 23 | 17 | 340 |

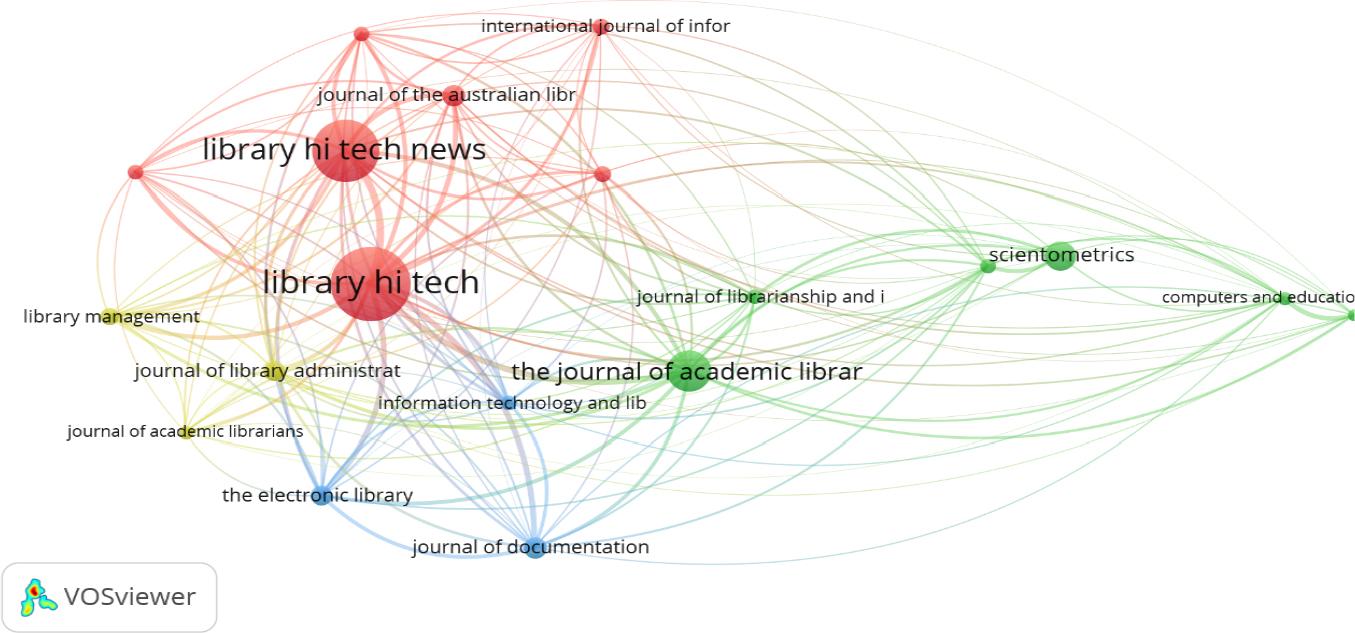

The journal co-citation map, shown in Figure 7, is represented by four clusters, 19 items, and 159 links, with a strength of 3659. Cluster 1 (red) comprises seven nodes led by the journals Library Hi Tech (117), Library Hi Tech News(110), and Journal of the Australian Library and Information Association (34). Cluster 2 (green) consists of 6 nodes headed by the Journal of Academic Librarianship (66), Scientometrics (47), Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology (24), and Journal of Librarianship and Information Science (24). Cluster 3 (blue) comprises three nodes led by the Journal of Documentation (34), the Electronic Library (33), and Information Technology and Libraries (24). Cluster 4 (yellow) comprises three nodes led by the Journal of Library Administration (33), Library Management (28), and Journal of Academic Librarianship(21).

Scientific source co-citation network.

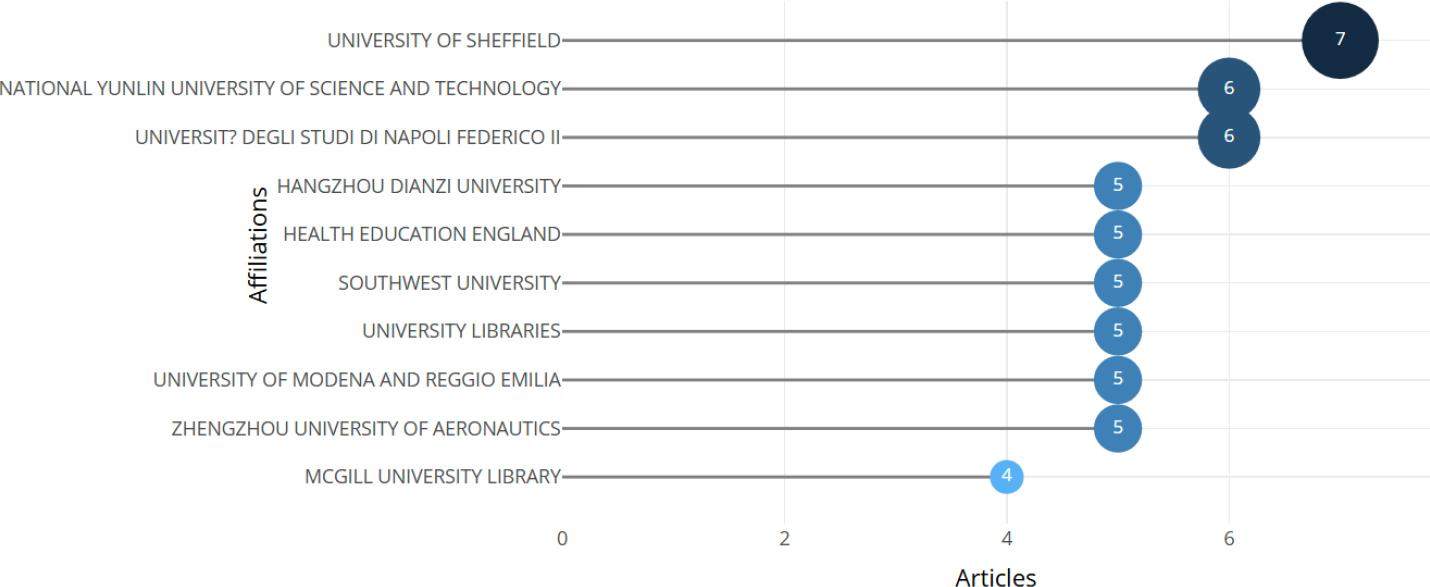

Figure 8 shows the most significant associations based on the number of articles published on AI tools and applications in academic libraries. Considering the number of articles they have written, the University of Sheffield is at the top with seven, followed by Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II and the National Yunlin University of Science and Technology, which have six articles.

Academic libraries’ most pertinent affiliations in AI research.

The findings show that certain institutions significantly concentrate their research efforts on AI applications for academic libraries. The University of Sheffield’s prominent position demonstrates its longstanding experience, expertise, and dedication to this developing field. Institutions such as Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II and the National Yunlin University of Science and Technology have also made interesting contributions, underscoring the international scope of research cooperation. They have made significant contributions, highlighting the global nature of research collaboration. The equal contribution of five articles from several institutions suggests a broad yet decentralized research interest, demonstrating a collaborative effort in exploring AI’s role in transforming academic library services. These findings reflect the growing interdisciplinary focus on leveraging AI technologies to address academic libraries’ information retrieval, user experience, and resource management challenges.

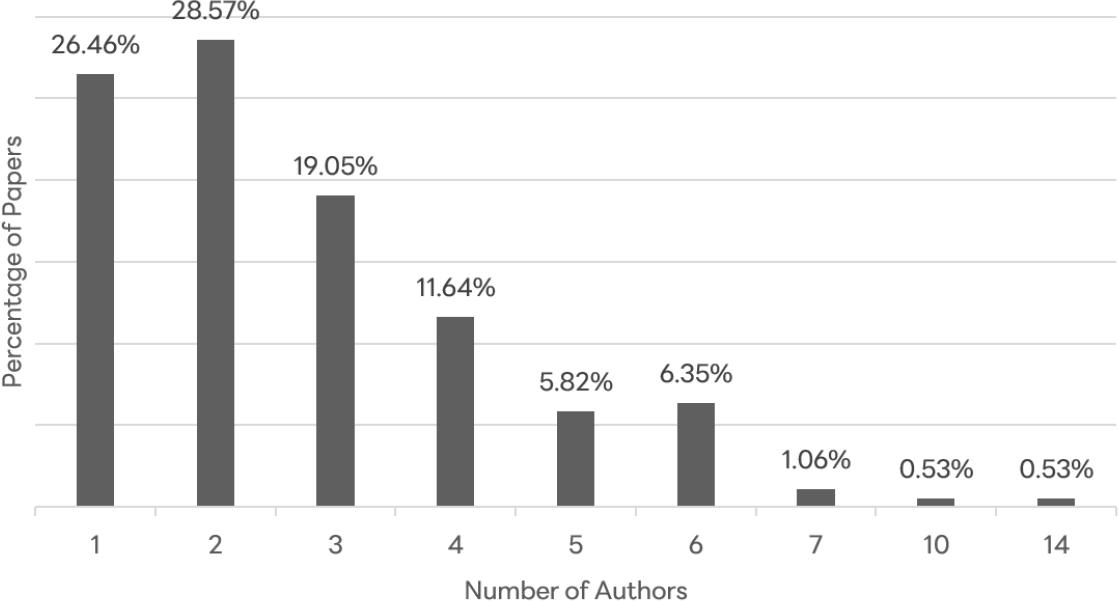

Before analyzing collaboration patterns in this section, there are 496 unique authors associated with these 189 publications. The average number of authors per study is 2.746, with a standard deviation of 1.813. Figure 9 demonstrates the distribution of publications based on the number of co-authors. The distribution of research papers based on the number of authors expressed as a percentage of total publications. This data reveals that papers with two authors are the most common, accounting for 28.75% of all papers, followed closely by single-author papers at 26.46%. Three-author papers represent 19.05%, while the percentage continues to decline as the number of authors increases. Notably, papers with four authors comprise 11.64%, and those with five and six authors constitute 5.82% and 6.35%, respectively. Very few papers have large author teams; less than 2% have seven or more authors, with papers involving 10 or 14 authors each making up only 0.53% of the total.

Distribution of AI in academic libraries papers by the number of authors expressed as a percentage of total publications.

This distribution shows that most AI research in academic libraries is produced through limited collaboration, usually between one and three authors. The prevalence of two-author works highlights a preference for small-scale collaboration, even though the number of single-author papers is still high. This pattern is consistent with past research showing that papers with multiple authors, especially those with two or more contributors, generally receive more citations. However, the relatively low frequency of papers with large collaborative teams suggests that large-scale collaboration is still rare in this research community. This realization can direct initiatives to promote more extensive and multidisciplinary cooperation, potentially increasing the prominence and influence of research. Furthermore, since they comprise the majority of collaborative activity, papers with two to six authors may offer the richest and most instructive structures for network analysis.

The annual number of single-author and multi-author publications from 2014 to 2024 is shown in Figure 10. There has been a noticeable increase in the overall number of articles, with publications rising especially sharply starting in 2020. Initially, between 2014 and 2019, both types of authorship showed low publication counts, and the difference between single- and multi-author papers was minimal. However, from 2020, multi-author publications began to rise significantly, surpassing single-author works in volume and peaking in 2024 with 51 multi-author articles compared to 20 single-author articles. This expansion demonstrates a noticeable trend in recent years toward collaborative research methods.

Yearly distribution of single-author and multi-author publications from 2014 to 2024.

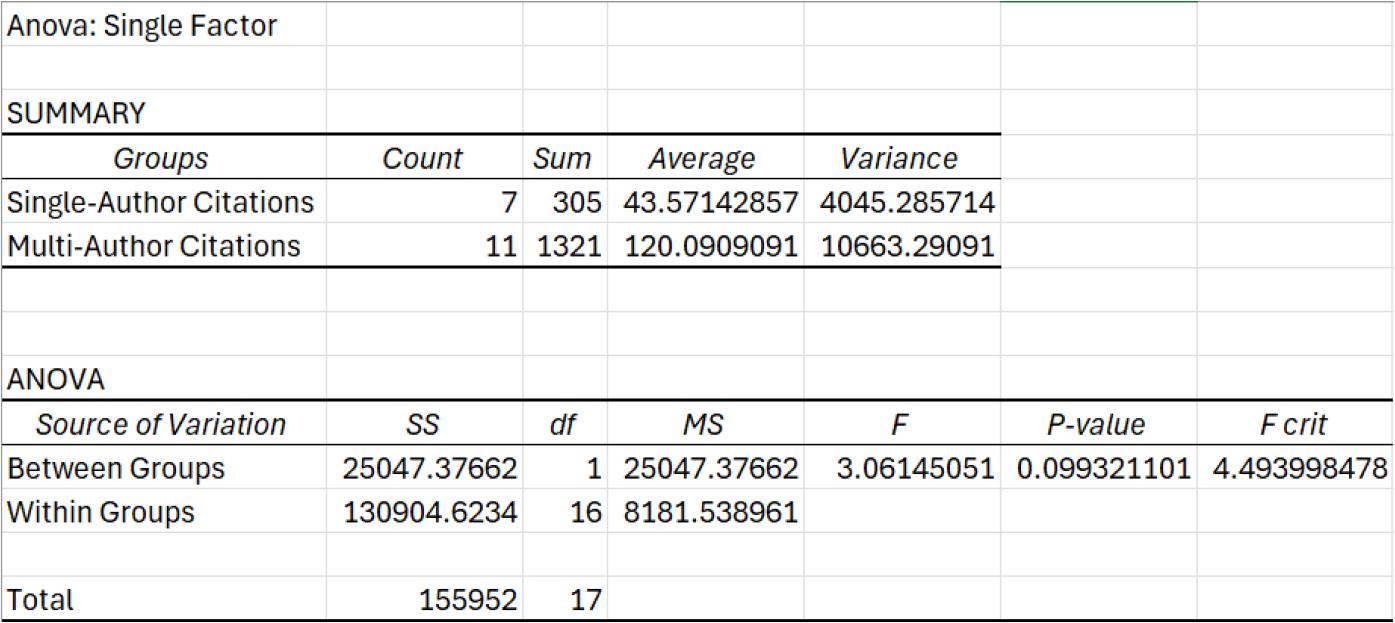

To investigate whether the number of authors on a scholarly article has a statistically significant effect on its citation performance, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted. The data were drawn from a sample of articles published between 2014 and 2024, categorized into two groups based on authorship: single-authored and multi-authored. The primary aim was to assess whether collaborative authorship is associated with a higher average number of citations. Figure 11, the summary statistics indicate that single-authored articles (n=7) had a mean citation count of 43.57, with a variance of 4045.29. Multi-authored articles (n=11) showed a significantly higher variance of 10663.29 and a significantly higher mean citation count of 120.09, indicating a higher degree of variability in their citation performance.

One-way ANOVA results comparing mean citation counts between single-authored and multi-authored articles from 2014 to 2024.

An F-statistic of 3.061 and a p-value of 0.0993 were obtained from the ANOVA test. The result is not statistically significant at the 5% level since the p-value is higher than the standard cutoff of 0.05. The calculated F-value is also less than the critical F-value (4.494), which supports the idea that the observed variations in mean citations between the two groups might have resulted from chance. The findings do not offer enough statistical support to rule out the null hypothesis of equal group means, even though there is a noticeable difference in the average number of citations between articles with one author and those with multiple authors. These findings suggest that having multiple authors has no statistically significant impact on an article’s citation in the dataset under observation. However, the test’s power may be limited by the small sample size (n=18), and any potential effects are obscured by the high within-group, particularly in the multi-author category.

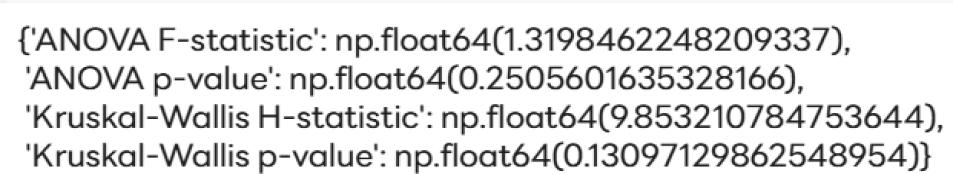

A robustness test using a cleaned dataset was conducted to evaluate whether the number of authors has a statistically significant effect on the citation impact of research articles. Articles were grouped based on the exact number of authors, and citation counts ranging from 1 to 7 authors were analyzed across these groups. Groups with insufficient data (such as “10 authors” and “14 authors”, each containing only one observation) were excluded to maintain statistical validity. The resulting dataset was balanced and analyzed using a one-way ANOVA and a non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test.

Figure 12 displays the statistical output of two analytical methods, ANOVA and Kruskal-Wallis, which were test-applied to test whether the number of authors on academic articles is associated with significant differences in citation counts. The ANOVA test yielded an F-statistic of approximately 1.32 and a p-value of 0.251, while the Kruskal-Wallis test, a non-parametric counterpart, reported an H-statistic of 9.85 and a p-value of 0.13. These results were derived from grouped data, in which articles were categorized based on the exact number of contributing authors (e.g., 1 to 7 authors), and each group’s citation counts were analyzed.

Results of a one-way ANOVA and Kruskal-Wallis test assessing the relationship between the number of authors and the number of citations received by scholarly articles.

According to the one-way ANOVA and the Kruskal-Wallis test results, the mean number of citations for each author group does not differ statistically significantly. Any observed differences in group means are most likely the result of random variation, as indicated by the ANOVA p-value (0.251), higher than the conventional alpha threshold of 0.05. Likewise, the non-significant p-value (0.131) obtained from the Kruskal-Wallis test, which loosens the assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variance, supported the parametric analysis’s conclusion. These results suggest that the number of co-authors on a paper has no discernible effect on its citation performance within the sample under investigation. Descriptive statistics might reveal differences in citation averages between author groups, but these variations are not statistically significant. In support of a more complex understanding of scholarly impact, this suggests that citation results may be more influenced by factors other than authorship numbers, such as research topic or institutional collaboration.

Building on the ANOVA and Kruskal-Wallis test results, a co-authorship analysis is a logical and valuable next step. While those tests assessed whether the number of authors influences citation impact, a co-authorship analysis focuses on the structure and dynamics of scholarly collaboration. Given that no statistically significant relationship was found between the number of authors and citation counts, a co-authorship analysis can help uncover more qualitative or structural insights, such as whether highly central or well-connected authors tend to produce more cited work; if there are distinct collaboration clusters or isolated individuals; how collaboration networks evolve over 2014-2024.

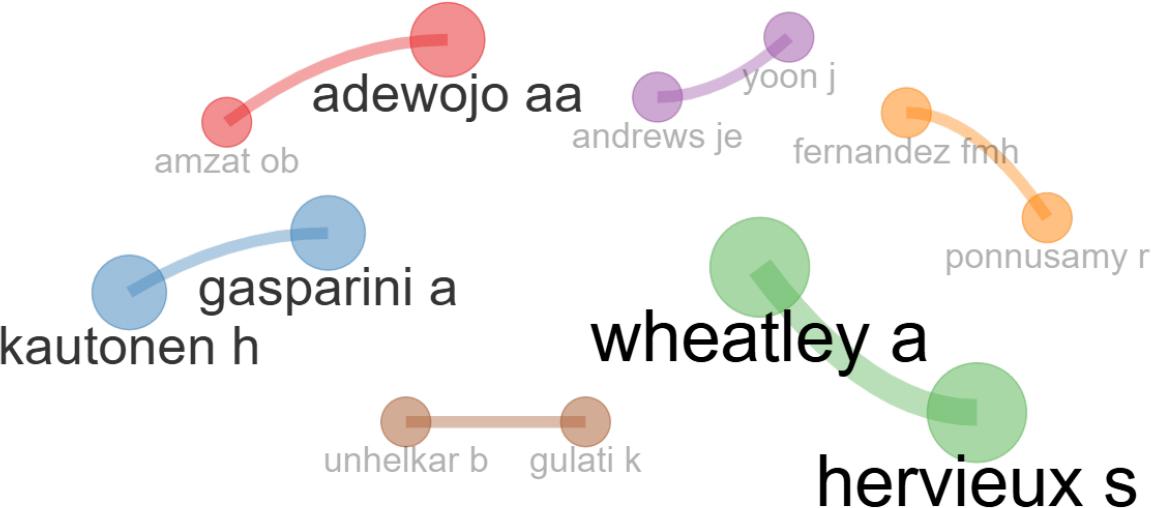

Author collaboration often considerably expands the area by facilitating knowledge and exchange. As anticipated, significant collaborative partnerships took place on several levels in the field of AI in academic library research. A co-authorship network of authors who contribute to the field is shown in Figure 13. With each node signifying a separate researcher and each edge denoting a co-authored publication, the network is represented by colored clusters that depict different author relationships. This network graph (Figure 13) was constructed using Biblioshiny in the Bibliometrix package, applying association strength normalization and Louvain clustering. Each cluster is color-coded to indicate a group of authors who frequently collaborate but are more loosely connected to authors outside their cluster. For example, the green, blue, and red clusters contain two authors linked by relatively thick edges, signifying strong collaborative relationships. On the other hand, some clusters, such as orange or purple, display weaker ties, which might suggest new or early partnerships. Each author’s contribution or centrality in the network was reflected in the label and node sizes, which were scaled for clarity.

Visualization of academic collaboration between the authors

The co-authorship network visualization has a structured but broken collaborative context, populated by six distinct author clusters shown in distinct colors. Each author is represented as a nodal point in the co-authorship network. The co-authorship collaborations among authors are indicated by edges connecting the author nodes. The no solo authorships support the focus to remain on active collaborations. The only co-authorship links included in the visualization are ones with at least two instances of co-authoring, thus eliminating the arbitrary collaborations and elevating the significance of the scholarly partnerships. As well, the sizes of the nodes are representative of author output or centrality in the network.

Table 7 presents key network metrics for each author, including cluster assignment, betweenness centrality, closeness centrality, and PageRank. Table 7 supports this visual interpretation through consistent network metrics across all authors. All authors exhibit a betweenness centrality of zero, suggesting that no individual acts as an intermediary or bridge between otherwise unconnected clusters. This absence of brokerage roles highlights a lack of cross-group collaboration within the current dataset. Furthermore, all authors display a closeness centrality of 1, which reflects the direct and sole connection within each dyad in the context of these isolated pairs. PageRank values are uniformly 0.083 for all nodes, indicating equal influence or importance within the local subnetworks but also revealing the lack of a dominant or highly cited figure within this community.

Centrality metrics and cluster membership of authors in the co-authorship network on AI in academic libraries.

| Node | Cluster | Betweenness | Closeness | PageRank |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adewojo aa (Adewojo et al., 2024) | 1 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.083 |

| Amzat ob | 1 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.083 |

| Gasparini a (Kautonen & Gasparini, 2024) | 2 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.083 |

| Kautonen h | 2 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.083 |

| Hervieux s (Hervieux & Wheatley, 2021; Wheatley & Hervieux, 2020) | 3 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.083 |

| Wheatley a | 3 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.083 |

| Andrews je (Andrews et al., 2021; Yoon et al., 2022) | 4 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.083 |

| Yoon j | 4 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.083 |

| Fernandez fmh (Fernandez & Ponnusamy, 2015; Provenzano et al., 2024) | 5 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.083 |

| Ponnusamy r | 5 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.083 |

| Gulati k (Kamal Gulati & Unhelkar, 2024) | 6 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.083 |

| Unhelkar b | 6 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.083 |

This is a new field where researchers are still creating foundational work alone or in small, isolated groups because scholars lack connections. On the other hand, it might represent institutional or disciplinary barriers that prevent more extensive cooperation. It recommends ways to promote collaboration between clusters, multi-author publications, and the creation of cooperative hubs. Promoting these relationships may improve the research domain’s general cohesiveness and productivity, aiding in developing more cohesive scientific communities.

Each node represented a country in the resulting network map, and its size reflected its total number of publications. The visualization revealed that countries or regions leading contributors to the literature on AI in academic libraries are the United States, with 56; India, with 36 documents; China, with 20; and the United Kingdom, with 10, as shown in Figure 14. Strong publication outputs from these countries indicate that academics actively use AI technologies in library settings. Strategic insights into the areas where AI-related library innovation is most actively pursued were made possible by this assistance in identifying global research hotspots.

Visualization of co-authorship by country.

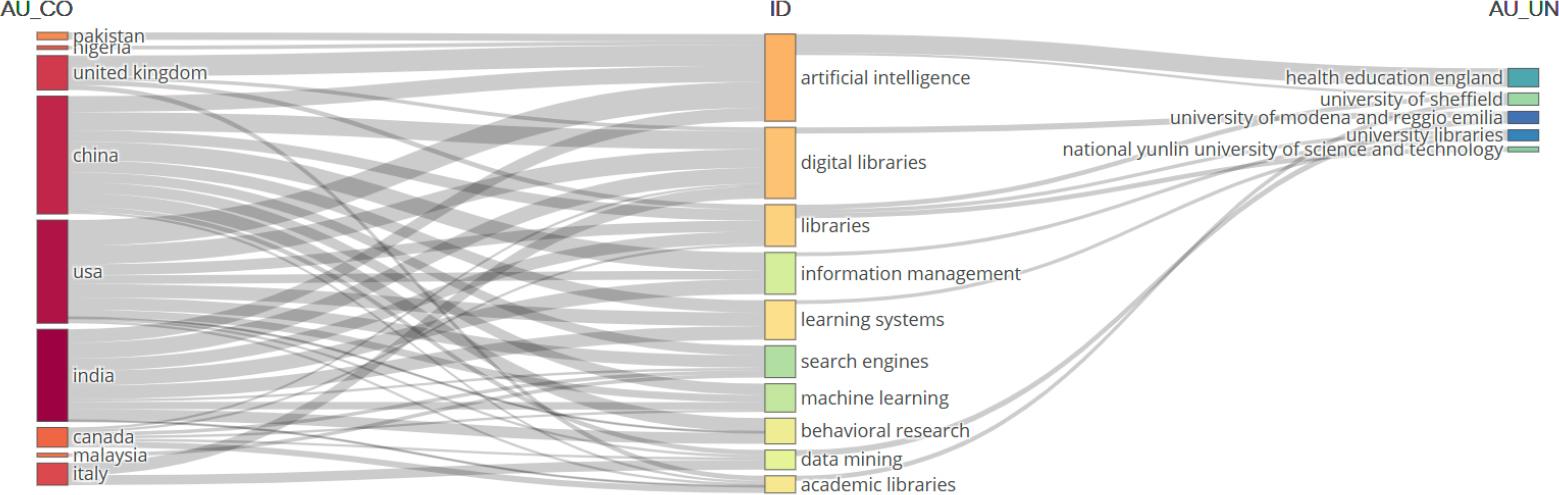

The three fields plot illustrates the relationship between contributing countries (AU_CO), keywords (ID), and affiliated institutions (AU_UN) in the domain of AI applications in academic libraries, as shown in Figure 15. The productivity mapping based on a three-field plot highlights the geographic distribution and thematic alignment of scholarly output related to AI applications in academic libraries. With a significant number of publications covering important topics like artificial intelligence, digital libraries, information management, and machine learning, China, the US, and India were the most prolific of the top contributing countries. China is investing heavily in AI, with a focus on both the research side and the application side. As a result, the future of the AI industry and the annual revenue generated from it may eventually shift the power balance of AI in the world (Masi et al., 2025). The United States exhibits a wide thematic range and longstanding research infrastructure supporting digital innovation in academic institutions (Cox, Kennan et al., 2019). India’s increasing contributions are noteworthy, especially in learning systems and search engines, which complement the country’s emphasis on automation and digital learning (Subaveerapandiyan & Gozali, 2024).

Three fields plot.

Significant productivity and institutional influence were also shown by the UK, as evidenced by its obvious ties to the University of Sheffield and Health Education England, which point to policy-aligned research and useful applications of AI in academic and health information services. Other countries, including Pakistan, Nigeria, Canada, Malaysia, and Italy, contributed to a smaller but growing body of literature, with research often focused on localized applications of AI in libraries, such as behavioral research, academic libraries, and data mining. These nations increasingly participate in the global conversation on AI in library science, though their collaborations tend to be more regionally concentrated. This analysis underscores disparities in research output and the potential for future international collaboration, especially involving countries with emerging AI agendas. Encouragingly, cross-country linkages suggest a moderate level of global knowledge sharing, though stronger transnational networks would benefit the equitable diffusion of AI tools and practices across diverse academic library environments (Buitrago-Ciro et al., 2025; Dezuanni & Osman, 2024).

Figure 16(a) illustrates the temporal evolution of key research terms with bubble size indicating the frequency of publications associated with each term. The years are shown on the x-axis, and the terms are listed on the y-axis. Figure 16(b) represents the frequency and importance of keywords in AI-related research for academic libraries. More significant words indicate more frequent or prominent topics in the analyzed literature.

Research topics on AI applications in academic libraries (a) temporal trends (2016-2024), (b) word cloud of author keywords.

Figure 16(a) reveals that early terms of “learning systems,” “behavioral research,” and “search engines” dominated from 2016-2018, reflecting the foundational exploration of AI in user behavior, education, and information retrieval. Post-2020, “artificial intelligence,” “digital libraries,” and “data mining” emerged as dominant themes, indicating the integration of advanced AI technologies in digital transformations and analytics. The emphasis on “artificial intelligence” and “digital libraries” demonstrates the increasing role of AI in automating and enhancing library systems, including cataloging, personalized recommendations, and resource management. The emergence of terms like “data mining” and “natural language processing” reflects advancements in using AI to extract insights from extensive data and improve information retrieval.

The word cloud (Figure 16(b)) visualizes the 50 most frequent author keywords related to the intersection of artificial intelligence (AI) and academic libraries based on word frequency. Using a circular layout, larger words indicate higher occurrence. Prominent terms include “academic libraries,” “machine learning,” “artificial intelligence (AI),” “chatGPT,” “generative AI,” and “digital libraries.” These keywords capture the expanding discussion about incorporating AI-powered technologies into library services. The prevalence of “academic libraries” and “machine learning” indicates a great deal of research being done on using intelligent systems to improve library operations like user interaction, classification, and information retrieval. The presence of “chatGPT” and “generative AI” signals a recent surge in interest in large language models and their implications for knowledge access, content creation, and library instruction. This keyword distribution, viewed thematically, demonstrates how traditional library concerns like information literacy, academic integrity, and user experience are coming together with new AI technologies. “Virtual assistants,” “digital libraries,” and “information services” are some terms that highlight how libraries are changing in the context of digital transformation.

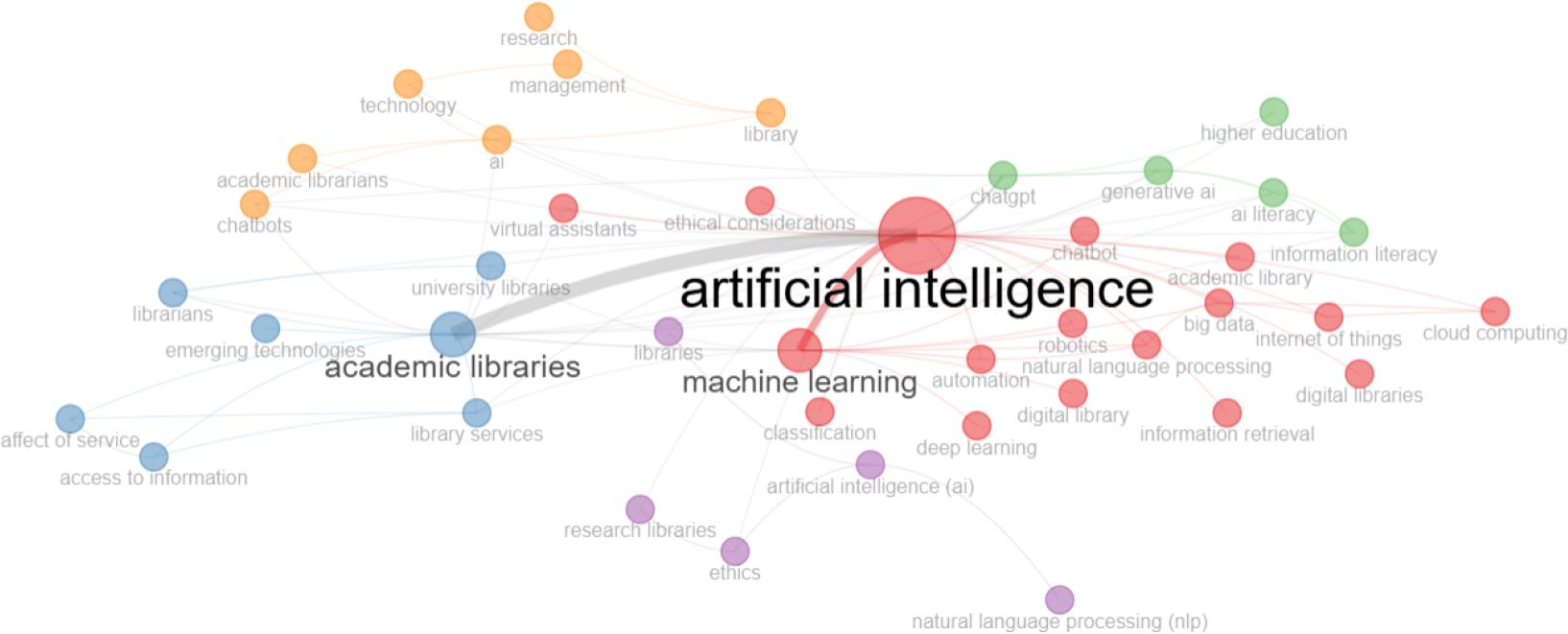

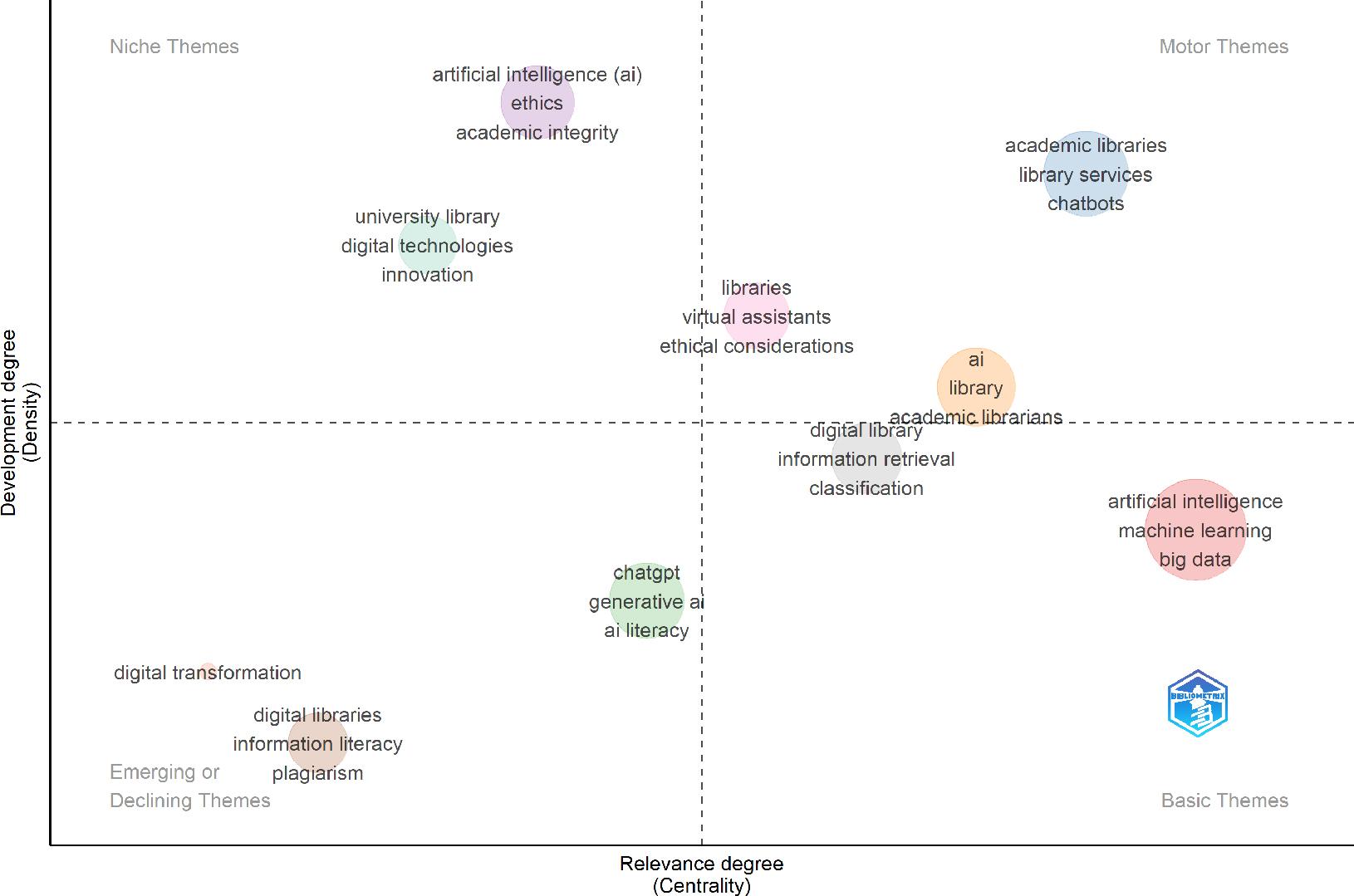

Figure 17 displays the co-occurrence network visualization generated using Biblioshiny (Bibliometirx), employing the Louvain clustering algorithm with association normalization and key parameters: 50 nodes, a minimum of 2 co-occurrences, and isolated nodes removed. The layout is automatic with dot-shaped nodes, and label overlap is suppressed for clarity. The conceptual landscape of artificial intelligence research in academic libraries, as well as thematic clusters, are revealed by this network, which offers a structural representation of how author-defined keywords co-appear in the literature.

The top 50 author keywords in academic library documents about AI applications. Notably, red cluster 1 is followed by blue cluster 2, green cluster 3, purple cluster 4, and yellow cluster 5.

At the network’s core, “artificial intelligence” and “academic libraries” emerge as the most central and highly connected nodes, indicating their dominance as focal topics. Closely linked to these are terms like “machine learning,” “digital libraries,” “chatGPT,” “natural language processing,” and “information literacy,” all of which form dense, well-connected clusters. This suggests an integrative research trend in which AI technologies are being increasingly applied to enhance academic library services, ranging from intelligent search and automation to educational support and digital infrastructure. Color-coded clusters representing various thematic communities were found using the Louvain clustering algorithm. Terms like “machine learning,” “robotics,” and “automatic” are included in the red cluster around “artificial intelligence,” for example, suggesting a strong emphasis on technological applications. The green cluster reflects a current interest in conversational AI and its implications for education and digital engagement by connecting terms like “generative AI,” “ChatGPT,” and “AI literacy.” The blue cluster around “academic libraries,” “library services,” and “university libraries” reflects traditional library science concerns now being re-contextualized through AI integration.

Table 8 presents the results of the author keyword co-occurrence network, organized into five distinct clusters using the Louvain clustering algorithm. Each cluster is color-coded and includes keywords along with network centrality metrics: Betweenness, Closeness, and PageRank, which help to identify the influence and positioning of keywords within the network structure.

Author keyword co-occurrence network results.

| Cluster | Betweenness | Closeness | PageRank | Author-Keywords |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Red (17 items) | 610.241 | 0.02 | 0.216 | artificial intelligence |

| 122.336 | 0.014 | 0.08 | machine learning | |

| 1.556 | 0.012 | 0.025 | big data | |

| 0 | 0.011 | 0.007 | digital libraries | |

| 0 | 0.009 | 0.007 | digital library | |

| 0 | 0.011 | 0.007 | information retrieval | |

| 0 | 0.011 | 0.01 | academic library | |

| 0 | 0.012 | 0.019 | automation | |

| 0.167 | 0.012 | 0.019 | natural language processing | |

| 0 | 0.011 | 0.007 | classification | |

| 0 | 0.009 | 0.007 | deep learning | |

| 0 | 0.012 | 0.013 | virtual assistants | |

| 0 | 0.009 | 0.007 | chatbot | |

| 0 | 0.011 | 0.014 | cloud computing | |

| 0 | 0.011 | 0.007 | ethical considerations | |

| 0 | 0.011 | 0.016 | internet of things | |

| 0 | 0.012 | 0.012 | robotics | |

| 2 Blue (7 items) | 120.121 | 0.014 | 0.1 | academic libraries |

| 9.094 | 0.013 | 0.026 | library services | |

| 0 | 0.012 | 0.021 | university libraries | |

| 0 | 0.009 | 0.015 | access to information | |

| 0 | 0.009 | 0.007 | emerging technologies | |

| 0 | 0.012 | 0.018 | librarians | |

| 0 | 0.009 | 0.014 | affect of service | |

| 3 Green (5 items) | 3.095 | 0.012 | 0.041 | ChatGPT |

| 0.625 | 0.012 | 0.026 | generative AI | |

| 0 | 0.012 | 0.017 | AI literacy | |

| 0 | 0.012 | 0.017 | information literacy | |

| 0 | 0.011 | 0.011 | higher education | |

| 4 Purple (5 items) | 39.5 | 0.008 | 0.023 | artificial intelligence (AI) |

| 36 | 0.012 | 0.014 | libraries | |

| 38 | 0.012 | 0.019 | ethics | |

| 0 | 0.006 | 0.01 | natural language processing (NLP) | |

| 0 | 0.011 | 0.012 | research libraries | |

| 5 Yellow (7 items) | 9.766 | 0.013 | 0.038 | AI |

| 54.348 | 0.012 | 0.024 | library | |

| 0 | 0.012 | 0.024 | chatbots | |

| 0 | 0.011 | 0.012 | academic librarians | |

| 0.5 | 0.008 | 0.012 | management | |

| 21.652 | 0.011 | 0.017 | technology | |

| 0 | 0.008 | 0.008 | research |

Cluster 1 (Red, 17 items) centers around “artificial intelligence,” which holds the highest betweenness (610.24) and PageRank (0.216), indicating its role as the most influential and connective term in the network. Other key terms include “machine learning,” “digital libraries,” “big data,” “chatbot,” and “cloud computing,” reflecting technological and systems-based applications of AI within library contexts.

Cluster 2 (Blue, seven items) is dominated by “academic libraries” (betweenness = 120.12), which serve as the thematic hub. This cluster reflects the institutional and service-related aspects of AI integration, including “library services,” “access to information,” and “university libraries.”

Cluster 3 (Green, five items) revolves around “chatGPT,” “generative AI,” and “AI literacy.” This cluster captures emerging trends and the rise of conversational AI and educational themes. The relatively high PageRank of “chatGPT” (0.041) suggests its growing prominence.

Cluster 4 (Purple, five items) includes terms like “ethics,” “libraries,” and “natural language processing (NLP),” pointing to a conceptual blend of ethical foundational and computational concerns surrounding AI use in libraries.

Cluster 5 (Yellow, seven items) captures broader and administrative themes such as “AI,” “technology,” “academic librarian,” and “research,” with moderate PageRank and betweenness values suggesting their supporting role in the overall structure.

Five distinct thematic communities are revealed by the network, which reflects the complex research environment at the nexus of academic libraries and artificial intelligence. The clusters are separate but linked, with “artificial intelligence” and “academic libraries” serving as key hubs that connect institutional implementation and technological innovation. Keywords like “chatGPT,” “machine learning,” and “AI literacy” indicate a change in the discourse from infrastructure-focused research to issues of ethics, education, and human interaction.

These findings emphasize the significance of both well-established and new research themes. The dominance of AI-related terms like “machine learning,” “automation,” and “deep learning” in the Red cluster show that the technical applications of AI are still central to scholarly attention. At the same time, the Green and Purple clusters emphasize the growing awareness of ethical and social considerations, especially regarding AI’s influence on education, information access, and professional roles in libraries. The separation of institutional and service-related terms (Blue cluster) suggests that while technological innovation is accelerating, the library profession remains grounded in service delivery, user experience, and information literacy, which are now being reframed in the context of AI.