Ecosystem services are all material and non-material benefits that humans derive from nature and are key components of their overall well-being. The classification of ecosystem services includes four main categories: (i) provisioning services (e.g., provision of food, timber); (ii) regulating services (climatic conditions, water and soil quality); (iii) cultural services (recreational, esthetic); and (iv) supporting services (biodiversity, nutrient cycling) (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment 2005).

Forest ecosystems serve as vital sources of a diverse range of ecosystem services. The key ecosystem services provided by forests include the following: (1) conservation of biodiversity; (2) sequestration and storage of carbon contributing to the regulation of the global carbon cycle; (3) protection of soils and regulation of groundwater; (4) reduction of the risks of adverse or even dramatic weather anomalies; (5) provision of various recreational services and opportunities to meet esthetic needs; and (6) provision of valuable forest products (Jenkins et al. 2018). Over the past two decades, several thousand scientific studies have been published, addressing various aspects of the scientific problem of forest ecosystem services (Aznar-Sánchez et al. 2018). To date, a range of methodological approaches has been developed for evaluating the quality and extent of these ecosystem services of forest ecosystems (Dobbs et al. 2011; Ninan et al. 2013; Grammatikopoulou et al. 2021; Tiemann et al. 2022; Raihan 2023).

Among all forest-forming species of woody plants capable of generating numerous ecological services, poplar species and cultivars occupy a special place (Broeckx et al. 2012; Hayda et al. 2024). Due to their rapid growth at a young age, poplar cultivars can accumulate significant amounts of biomass in a short period, which, on the one hand, accelerates the sequestration of atmospheric carbon dioxide and, on the other, contributes to the formation of a reliable, renewable bioenergy source (Fuchylo et al. 2018). Given this, in regions of the world suitable for poplar plantation cultivation, extensive multifaceted research has been conducted over the years focusing on current issues of the breeding of poplar cultivars (Riemenschneider et al. 2001), the technology of their cultivation (Dani et al. 2024), biomass harvesting (Fang et al. 2007), plant protection from diseases and pests (Kwaśna et al. 2021), and assessments of the types, quality, and volume of ecosystem services they provide (Zalesny et al. 2012; Fortier et al. 2016).

In Ukraine, particularly in its western region, poplar cultivars have significant potential for their use for bioenergy applications. Poplar plantations play a crucial role as a depository of atmospheric carbon, helping to reduce atmospheric concentrations of one of the most critical greenhouse gases – carbon dioxide. To identify and assess the bioenergetic and carbon-sequestration potential, as well as the oxygen-producing capacity of poplars, an essential scientific task remains the experimental testing of various poplar cultivars under specific forest-growing conditions and within different natural zones of Ukraine.

The aim of the study was to examine the peculiarities of the growth dynamics and productivity of poplar cultivars in the Western Forest-Steppe of Ukraine, to assess trends in their efficiency in providing ecosystem services, and, based on this, to determine the optimal maturity age of poplar cultivars at which they most effectively generate a range of ecosystem services.

The object of the research was an experimental poplar plantation established in section 11 of the 17th quarter of the Ternopil Forestry, part of the “Kremenets Forestry Branch” of the Podilsk Office of the State Enterprise “Forests of Ukraine.” Four poplar cultivars are being tested on the plantation: ‘Canadian-Balsamic,’ ‘Tronko’, ‘Druzhba’, and ‘Strilopodibna’. Each cultivar is planted in paired rows, 100 meters long, with a planting density of 2 × 0.8 meters (6250 plants per hectare).

The cultivar ‘Canadian-Balsamic’ is an artificial hybrid of the P. deltoides Marsh. and P. balsamifera L. The cultivar ‘Tronko’ is a natural Euro-American hybrid of Italian selection (P. × euramericana (Dode) Guinier). The cultivar ‘Druzhba’ was bred at the Ukrainian Research Institute of Forestry and Forest Melioration (URIFFM) through the crossbreeding of P. trichocarpa Torr. & A. Gray ex. Hook. and P. laurifolia Ldb., followed by the selection of elite seedlings from the hybrid offspring. The cultivar ‘Strilopodibna’ is an artificial hybrid of P. × euramericana (Dode) Guinier and P. pyramidalis (Torosova et al. 2015).

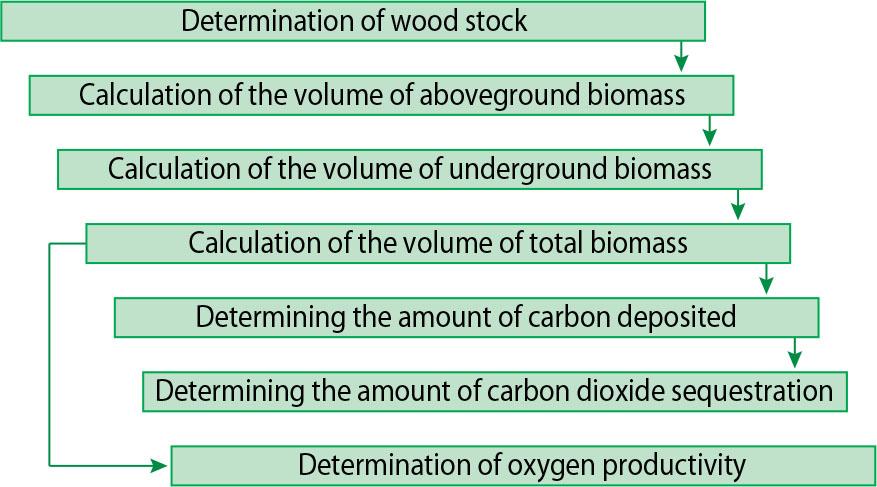

To assess carbon-sequestration potential and oxygen productivity of poplar cultivars, the following methodological scheme was used ( Fig. 1):

Stages of assessing the carbon-sequestration potential and oxygen productivity of poplar cultivars (Hayda et al. 2024)

As we can see, the first four stages are common for determining the volumes of both ecosystem services, that is, the final stages of assessing the volumes of carbon deposition, CO2 sequestration, and the oxygen productivity of poplar cultivars require the completion of calculations of the total biomass of poplar trees on the plantation. It should be noted that when assessing the volumes of oxygen production, a methodical approach was used (Başkent et al. 2011, Guo et al. 2001), based on which a conversion factor of 1.2 was applied in the formula for determining the plant oxygen productivity based on the calculated volume of dry biomass.

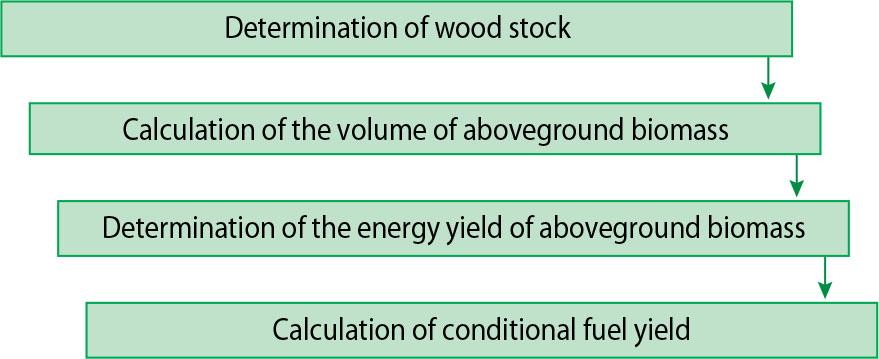

The quantitative assessment of the bioenergetic productivity of poplar cultivars was carried out according to the following methodological scheme (Fig. 2).

Stages of assessment of bioenergetic productivity of poplar cultivars (Hayda et al. 2024)

To assess the energy yield from poplar biomass, the average value of the specific heat of combustion of poplar biomass (18.53 KJ/g) was used, determined for 19 poplar cultivars (Kutsokon et al. 2017).

The calculation algorithms for individual elements of the aforementioned methodological schemes are presented below. The determination of stem wood volume was carried out using generally accepted forest taxation methods: trunk diameters at a height of 1.3 m and tree heights were measured, and the cross-sectional area of the trunks and form factors were calculated. By comparing the number of poplar trees that remained on the plantation with the total number of planting sites, the survival rate of poplar cultivars was determined.

Aboveground biomass (AGB) was calculated using the following formula (IPCC 1996):

Wood Stock – the stock of stem wood (m3∙ha−1), Wood Density – the basic density of wood (for poplar, 0.440 t∙(m3)−1), Biomass Expansion Factor – a biomass “expansion” coefficient that accounts for all components of aboveground biomass, except for the trunk with bark, as well as leaves and branches (Brown et al. 1992; IPCC 2006). In our study, a BEF value of 1.37 was used (Debryniuk et al. 2020).

To estimate belowground biomass (BGB), the aboveground biomass (AGB) was multiplied by a conversion factor of 0.25 (IPCC 2006):

Total biomass (TB) was calculated by summing the biomass of all components (aboveground and below-ground):

Carbon stock (CS) was estimated by multiplying the total biomass by the carbon concentration factor (CF), which was assumed to be 0.50 (IPCC 1996):

Carbon dioxide (CO2) sequestration was estimated by multiplying the carbon stock by a factor of 44/12 (IPCC 1996):

Periodic measurements and records on the experimental plantation of poplar cultivars were conducted at 7, 9, and 15 years of age. This allowed us to assess the dynamics of the volumes of ecological services that poplar plantations can generate over a relatively long period.

As shown in Table 1, the survival rate of poplar cultivars gradually declined over the 15-year period. On the 7-year-old plantation, the average survival rate was 83.5%, decreasing to 67.5% at 9 years and further to 32.5% at 15 years. The trend of this indicator under conditions of natural thinning was almost linear (R2 = 0.995). At 7 years of age, the average height of the cultivars varied slightly, ranging from 9.5 to 10.3 m, while trunk diameter ranged from 6.5 to 7.4 cm. At 15 years, the height variation increased significantly (14.4–15.8 m), and trunk diameter at breast height varied even more (10.5–14.5 cm). The dynamics of the poplar stem wood stock on the experimental plantation showed an overall increase from 108.3 m3∙ha−1 at 7 years to 134.5 m3∙ha−1 at 15 years. However, in terms of cultivars, the dynamics of their productivity are somewhat different. Thus, the poplar Strilopodibna, due to its slightly lower growth rate in height and diameter, had the smallest stem wood stock at 7 years (93 m3∙ha−1). However, due to its lower natural tree loss rate, it ranked the second place in this indicator at 9 years and rose to the first place at 15 years, nearly doubling its stock to 171 m3∙ha−1 over 8 years. Accordingly, the rate of decline in stock accumulation for this cultivar was slower than that of others. At 15 years of age, this indicator for the poplar Strilopodibna remained above 10 m3∙ha−1∙year−1.

Dynamics of growth and productivity of poplar cultivars

| Cultivars | Number of trees, pcs.·ha−1 | Survival, % | Height (Н), m | Diameter at breast height (DBH), cm | Wood stock, m3∙ha−1 | Annual stock change, m3∙ha−1∙year−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 years | ||||||

| ‘Strilopodibna’ | 5125 | 82 | 9.6±0.46 | 6.5±0.27 | 93 | 13.3 |

| ‘Druzhba’ | 5375 | 86 | 10.3±0.33 | 6.8±0.32 | 122 | 17.4 |

| ‘Canadian-Balsamic’ | 4875 | 78 | 9.8±0.36 | 7.4±0.33 | 113 | 16.1 |

| ‘Tronko’ | 5500 | 88 | 9.5±0.46 | 6.6±0.27 | 105 | 15.0 |

| 9 years | ||||||

| ‘Strilopodibna’ | 4875 | 78 | 11.3±0.27 | 7.7±0.30 | 117 | 13.0 |

| ‘Druzhba’ | 5000 | 80 | 11.8±0.21 | 8.1±0.31 | 139 | 15.4 |

| ‘Canadian-Balsamic’ | 3250 | 52 | 11.2±0.53 | 9.1±0.46 | 111 | 12.3 |

| ‘Tronko’ | 3750 | 60 | 11.3±0.34 | 8.2±0.33 | 102 | 11.3 |

| 15 years | ||||||

| ‘Strilopodibna’ | 3675 | 59 | 15.5±0.53 | 10.6±0.22 | 171 | 11.4 |

| ‘Druzhba’ | 2225 | 36 | 14.4±0.42 | 10.5±0.20 | 134 | 8.9 |

| ‘Canadian-Balsamic’ | 900 | 14 | 15.8±0.72 | 14.5±0.58 | 122 | 8.1 |

| ‘Tronko’ | 1300 | 21 | 15.7±0.49 | 11.9±0.26 | 111 | 7.4 |

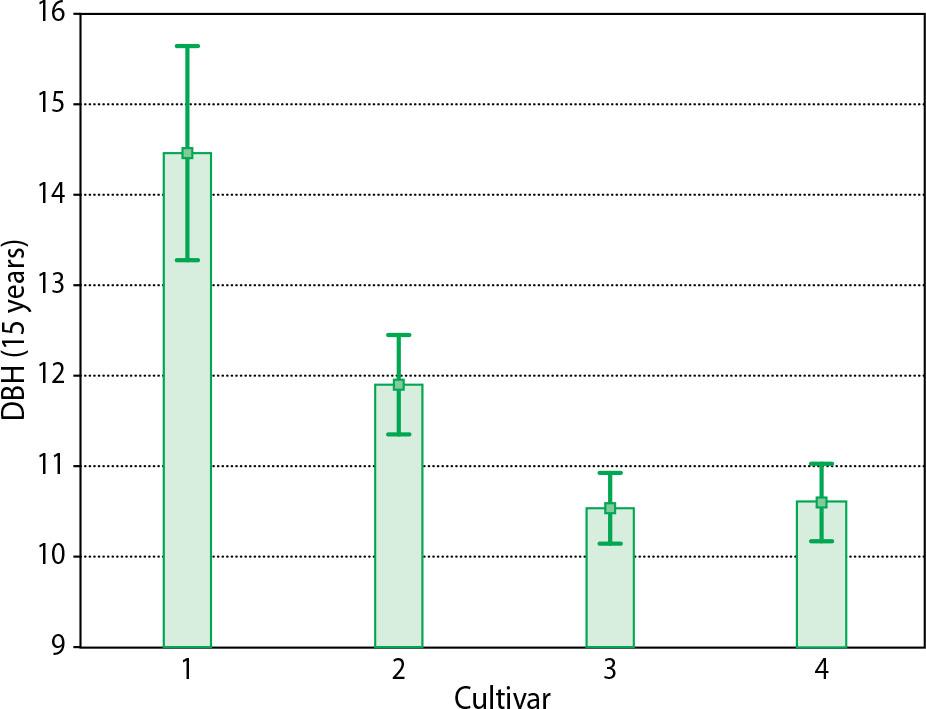

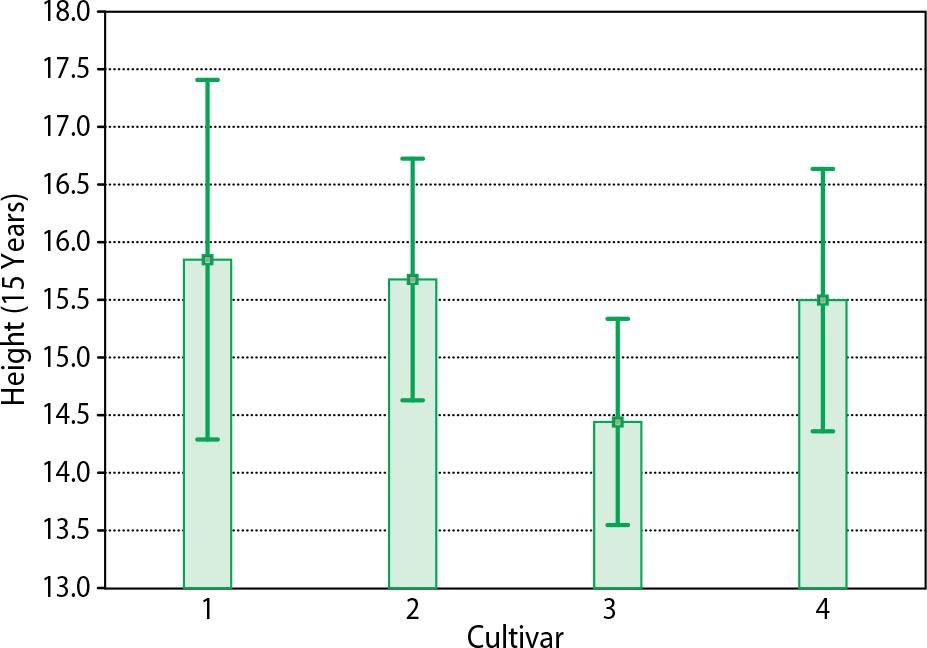

For a more detailed assessment of the differences between cultivars in taxation indicators, a comparative analysis of their growth at the age of 15 years was conducted using the one-way ANOVA method. As shown in Table 2 and Figure 3, the “cultivar” factor significantly affects only the trunk diameter. A pairwise comparison of the average trunk diameters of poplar cultivars, performed using Fisher’s LSD test, revealed that the differences between all cultivar pairs were statistically significant, except for the pair ‘Strilopodibna’–‘Druzhba’ (Tab. 3). By contrast, the differences in mean heights between all pairs of poplar cultivars ( Tab. 4, Fig. 4) were not statistically significant.

Results of one-way ANOVA analysis of variance for the height and diameter of poplar cultivars

| Index | Effect | LS | SS | DF | MS | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Height | intercept | *** | 13,917.88 | 1 | 13,917.88 | 3181.2 | <0.0001 |

| cultivar | n.s. | 17.79 | 3 | 5.93 | 1.355 | 0.2661 | |

| error | 240.63 | 55 | 4.38 | ||||

| Diameter at breast height (DBH) | intercept | *** | 34,059.12 | 1 | 34,059.12 | 5641.3 | <0.0001 |

| cultivar | *** | 498.99 | 3 | 166.33 | 27.6 | <0.0001 | |

| error | 1,913.86 | 317 | 6.04 |

Note: LS – signif. codes:

– p < 0,001,

– p < 0,01,

– p < 0,05;

n.s. – non-significant; SS – sum of squares; DF – degrees of freedom; MS – mean square; F – test statistic; p – p-value.

Mean plot of poplar cultivars diameters at breast height and mean±0.95 CI (1,–‘Canadian-Balsamic’; 2,–‘Tronko’; 3,–‘Druzhba’; 4,–‘Strilopodibna’)

Results of pairwise comparisons of the poplar cultivars average diameter at breast height (Fisher LSD test)

| Cultivar | ‘Canadian-Balsamic’ | ‘Tronko’ | ‘Druzhba’ | ‘Strilopodibna’ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ‘Canadian-Balsamic’ | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| ‘Tronko’ | <0.0001 | 0.0020 | 0.0015 | |

| ‘Druzhba’ | <0.0001 | 0.0020 | 0.8482 | |

| ‘Strilopodibna’ | <0.0001 | 0.0015 | 0.8482 |

Note: p-values for pairs of cultivar with significant differences shown in grey.

Mean plot of poplar cultivars heights and mean±0.95 CI (1,–‘Canadian-Balsamic’; 2,–‘Tronko’; 3,–‘Druzhba’; 4,–‘Strilopodibna’)

Results of pair-wise comparisons of the poplar cultivars average height (Fisher LSD test)

| Cultivar | ‘Canadian-Balsamic’ | ‘Tronko’ | ‘Druzhba’ | ‘Strilopodibna’ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ‘Canadian-Balsamic’ | 0.8262 | 0.0758 | 0.6539 | |

| ‘Tronko’ | 0.8262 | 0.1115 | 0.8157 | |

| ‘Druzhba’ | 0.0758 | 0.1115 | 0.1722 | |

| ‘Strilopodibna’ | 0.6539 | 0.8157 | 0.1722 |

Note: p-values for pairs of cultivar with significant differences shown in grey.

An important objective of the study was to identify trends in the efficiency of ecosystem service generation by these cultivars, as well as to determine the optimal age for harvesting plantations of such cultivars (the maturity age for ensuring specific types of ecosystem services).

The study found that all poplar cultivars in the experimental plantation exhibit a high potential for sequestering atmospheric carbon ( Tab. 5). At the age of seven, the cultivars can store between 35 and 46 t·ha−1 of carbon, which corresponds to the removal of 128.5–168.5 t·ha−1 of CO2 from the atmosphere. By the age of 15, these indicators increase further due to the positive growth in total phytomass. However, an analysis of annual and current change in CO2 sequestration across different years reveals distinct trends for different cultivars. Similar to changes in stemwood reserves, the annual CO2 sequestration of the cultivar ‘Strilopodibna’ declines at a significantly slower rate than that of ‘Druzhba’, ‘Canadian-Balsamic’, and ‘Tronko’. At the same time, the current change in CO2 sequestration for the cultivar ‘Strilopodibna’ remains positive and high at both 9 and 15 years of age, whereas for other cultivars, it is low and often even negative.

Dynamics of carbon and CO2-sequestration capacity of poplar cultivars

| Age | Traits | Cultivars | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ‘Strilopodibna’ | ‘Druzhba’ | ‘Canadian-Balsamic’ | ‘Tronko’ | ||

| 7 years | stock of stemwood, m3·ha−1 | 93 | 122 | 113 | 105 |

| total biomass, t·ha−1 | 70.1 | 91.9 | 85.1 | 79.1 | |

| sequestered carbon, t·ha−1 | 35.0 | 46.0 | 42.6 | 39.6 | |

| CO2 sequestration, t·ha−1 | 128.5 | 168.5 | 156.1 | 145.0 | |

| annual CO2 sequestration, t·ha−1 | 18.4 | 24.1 | 22.3 | 20.7 | |

| 9 years | stock of stemwood, m3·ha−1 | 117 | 139 | 111 | 102 |

| total biomass, t·ha−1 | 88.2 | 104.7 | 83.6 | 76.9 | |

| sequestered carbon, t·ha−1 | 44.1 | 52.4 | 41.8 | 38.4 | |

| CO2 sequestration, t·ha−1 | 161.6 | 192.0 | 153.3 | 140.9 | |

| annual CO2 sequestration, t·ha−1 | 18.0 | 21.3 | 17.0 | 15.7 | |

| current change in CO2 sequestration, t·ha−1 | 16.6 | 11.7 | –1.4 | –2.1 | |

| 15 years | stock of stemwood, m3·ha−1 | 171 | 134 | 122 | 111 |

| total biomass, t·ha−1 | 128.8 | 101.0 | 91.9 | 83.6 | |

| sequestered carbon, t·ha−1 | 64.4 | 50.5 | 46.0 | 41.8 | |

| CO2 sequestration, t·ha−1 | 236.2 | 185.1 | 168.5 | 153.3 | |

| annual CO2 sequestration, t·ha−1 | 15.7 | 12.3 | 11.2 | 10.2 | |

| current change in CO2 sequestration, t·ha−1 | 12.4 | –1.2 | 2.5 | 2.1 | |

A comparison of indicators of annual CO2 sequestration and current change in CO2 sequestration at different time points makes it possible to determine the maturity age of poplar in delivering ecosystem services such as CO2 sequestration and sequestered carbon (since these variables are linearly related). Maturity age is reached when annual CO2 sequestration and current change in CO2 sequestration become equal, with annual CO2 sequestration reaching its peak value. After this point, current change in CO2 sequestration falls below annual CO2 sequestration, although it may initially remain positive.

In our study, starting from the age of 9, current change in CO2 sequestration becomes lower than annual CO2 sequestration, while the annual CO2 sequestration indicator reaches its highest value at 7 years of age. Based on this, it can be assumed that the maturity age of poplar in providing ecosystem services such as sequestered carbon and CO2 sequestration occurs before the 7th year of age.

Another important ecosystem service, classified under regulating services and generated by poplar cultivar plantations, is oxygen production through photosynthesis. As shown in Table 6, plantations of the studied poplar cultivars can provide annual oxygen production of 12.0–15.8 t·ha−1 over a 7-year period, but only 6.7–10.3 t·ha−1 over 15 years. This suggests that the dynamics of oxygen production follow a similar trend to the changes observed in sequestered carbon and CO2 sequestration indicators. Therefore, the maturity age of poplar cultivars in delivering the ecosystem service of oxygen production is likely the same – before the 7th year.

Dynamics of oxygen productivity of poplar cultivars

| Age | Traits | Cultivars | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ‘Strilopodibna’ | ‘Druzhba’ | ‘Canadian-Balsamic’ | ‘Tronko’ | ||

| 7 years | total biomass, t·ha−1 | 70.1 | 91.9 | 85.1 | 79.1 |

| oxygen productivity, t·ha−1 | 84.1 | 110.3 | 102.1 | 94.9 | |

| annual oxygen productivity, t·ha−1 | 12.0 | 15.8 | 14.6 | 13.6 | |

| 9 years | total biomass, t·ha−1 | 88.2 | 104.7 | 83.6 | 76.9 |

| oxygen productivity, t·ha−1 | 105.8 | 125.6 | 100.3 | 92.3 | |

| annual oxygen productivity, t·ha−1 | 11.8 | 14.0 | 11.1 | 10.3 | |

| current change in oxygen productivity, t·ha−1 | 10.9 | 7.7 | –0.9 | –1.3 | |

| 15 years | total biomass, t·ha−1 | 128.8 | 101.0 | 91.9 | 83.6 |

| oxygen productivity, t·ha−1 | 154.6 | 121.2 | 110.3 | 100.3 | |

| annual oxygen productivity, t·ha−1 | 10.3 | 8.1 | 7.4 | 6.7 | |

| current change in oxygen productivity, t·ha−1 | 8.1 | –0.7 | 1.7 | 1.3 | |

In parallel with the provision of the above-mentioned ecosystem services by poplar cultivar plantations, once they reach maturity, poplar plantations are used for the harvesting of bioenergy raw materials, thereby generating another service, but this time from the provisioning services category. Various types of renewable biofuels can be produced from poplar wood (An et al. 2021).

When calculating the energy yield from poplar plantation wood, we considered only the aboveground biomass (available for harvesting), the volumes of which vary across cultivars similarly to wood stock volume. Consequently, the energy yield and conventional fuel output turned out to be the highest in cultivars with intensive growth and high productivity.

The data in Table 7 indicate that for two poplar cultivars – ‘Strilopodibna’ and ‘Canadian-Balsamic’ – a gradual increase in total energy productivity is observed up to 15 years. Trees of the ‘Druzhba’ cultivar reached their maximum total energy productivity potential at 9 years, whereas for the ‘Tronko’ cultivar, the trend of this indicator initially declines before shifting to an upward trajectory.

Dynamics of total, average, and current bioenergetic productivity of poplar cultivars

| Age | Traits | Poplar cultivars | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ‘Strilopodibna’ | ‘Druzhba’ | ‘Canadian-Balsamic’ | ‘Tronko’ | ||

| 7 years | stock of stemwood, m3·ha−1 | 93 | 122 | 113 | 105 |

| aboveground biomass, t·ha−1 | 56.1 | 73.5 | 68.1 | 63.3 | |

| energy yield, GJ·ha−1 | 1038.8 | 1362.7 | 1262.2 | 1172.8 | |

| yield of standard fuel, t·ha−1 | 35.4 | 46.5 | 43.0 | 40.0 | |

| annual energy yield, GJ·ha−1 | 148.4 | 194.7 | 180.3 | 167.5 | |

| 9 years | stock of stemwood, m3·ha−1 | 117 | 139 | 111 | 102 |

| aboveground biomass, t·ha−1 | 70.5 | 83.8 | 66.9 | 61.5 | |

| energy yield, GJ·ha−1 | 1306.9 | 1552.6 | 1239.9 | 1139.3 | |

| yield of standard fuel, t·ha−1 | 44.6 | 52.9 | 42.3 | 38.8 | |

| annual energy yield, GJ·ha−1 | 145.2 | 172.5 | 137.8 | 126.6 | |

| current change in energy yield, GJ·ha−1 | 134.0 | 94.9 | −11.2 | −16.8 | |

| 15 years | stock of stemwood, m3·ha−1 | 171 | 134 | 122 | 111 |

| aboveground biomass, t·ha−1 | 103.1 | 80.8 | 73.5 | 66.9 | |

| energy yield, GJ·ha−1 | 1910.1 | 1496.8 | 1362.7 | 1239.9 | |

| yield of standard fuel, t·ha−1 | 65.1 | 51.0 | 46.5 | 42.3 | |

| annual energy yield, GJ·ha−1 | 127.3 | 99.8 | 90.8 | 82.7 | |

| current change in energy yield, GJ·ha−1 | 100.5 | −9.3 | 20.5 | 16.8 | |

The annual energy yield for all cultivars gradually decreases from a 7-year-old plantation to a 15-year-old plantation. Initially, it ranged from 148.4 to 194.7 GJ·ha−1, whereas at an older age, it ranged from 82.7 to 127.3 GJ·ha−1, and the current change in energy yield for all cultivars, both at 9 and 15 years of age, is lower than the annual energy yield. Thus, it can be assumed that, in terms of maximizing energy biomass productivity in the conditions of the Western Forest-Steppe of Ukraine, it is advisable to establish mini-rotational plantations with a harvesting cycle (logging) of up to 7 years when using the studied poplar cultivars.

High biomass productivity in a short period of time is a distinctive feature of poplar species and cultivars (Hansen 1991; Truax et al. 2014; Stanton et al. 2021). However, it should be noted that this important phenotypic characteristic is not always and everywhere fully expressed in all environment conditions. One of the reasons for the low efficiency of the state program for establishing poplar plantations in Ukraine in the late 1950s and early 1960s, when 73,000 hectares of plantations were created, was the planting of poplar species and cultivars in conditions unfavorable for intensive growth. This highlights why it is important that plantations should be created in optimal sites and by careful establishment (Stanturf et al. 2002). It was in such favorable conditions in terms of soil trophicity and moisture (in a fresh oak grove, D2) that our experimental plantation was established. It is clear that under more favorable conditions, poplar can produce significantly higher biomass yields. Studies conducted under favorable forest-growing conditions for poplar (in a fresh oak grove) in the eastern Forest-Steppe of Ukraine (Kharkiv region) have shown that the cultivar ‘Strilopodibna’, which is also being tested near Ternopil, is among the best of the many tested varieties in terms of survival rate, growth, and biomass productivity both at the age of 2 and 30 years (Los and Zolotych 2014; Kutsokon et al. 2020).

According to Indian researchers (Lodhiyal et al. 1997), poplar plantations in the foothills of the central Himalayas can yield 113 t·ha−1 at 4 years of age, while in our conditions, a similar biomass stock is achieved only after 9 years (Tab. 5). However, if we take into account the data on the mean annual productivity of dry aboveground biomass in poplar, obtained on the basis of a generalization of studies on hundreds of plantations in China (4.4 t∙ha−1∙yr−1), Europe (5.1 t∙ha−1∙yr−1), and the United States (8.1 t∙ha−1∙yr−−1) (Wang et al. 2016), the poplar cultivars tested in the Western Forest-Steppe of Ukraine at 7 years of age proved to be quite productive, with indicators ranging from 8.0 to 10.5 t∙ha−1∙yr−1. This exceeds the productivity observed in Sweden, where the mean annual increment for poplar cultivars and aspen hybrids ranged from 3 to 10 t∙ha−1∙yr−1 (Christersson 2010), and in Romania, where productivity of 10-year-old planted poplar forest was 7.14 t∙ha−1∙yr−1 (Gheorghe 2024). It is also important to consider that the yield of energy poplar plantations largely depends on the harvesting cycle of phytomass (Martinik et al. 2015).

As demonstrated in the Global Analysis of Temperature Effects on Populus Plantation (Kutsokon et al. 2015), the growth of poplar cultivars and species is highly sensitive to rising air temperatures, which is one of the indicators of global climate change. Therefore, the continued selection of drought-resistant poplar clones is crucial for maintaining the high resource potential of poplar plantations in the future (Marchi et al. 2022). On the other hand, an equally important aspect in this pair of natural phenomena “poplar–climate” relationship is the potential impact of the first element on the second one—that is, the influence of poplar plantations on climate change itself. Numerous studies indicate that large-scale cultivation of poplar plantations can, to some extent, slow down and mitigate the effects of ongoing climate change (Niemczyk et al. 2019; Hao et al. 2021). This is primarily due to the ability of poplar cultivars to sequester part of the excess carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and store large amounts of carbon in their aboveground and underground biomass (Chauchan et al. 2015; Chavan et al. 2022), as well as in other components of artificial plantation ecosystems, such as litter and soil (Garten et al. 2011).

The clone type is often the primary factor determining the volumes of carbon sequestration and biomass production in poplar plantations (Meifang et al. 2017). This is fully confirmed by the results of our research, which demonstrate statistically significant differences between poplar cultivars in terms of growth parameters, biomass productivity, and the volume of other ecosystem services provided ( Tab. 5–7).

Poplar species and cultivar plantations are also recognized today as important renewable sources of bioenergy, serving as an alternative to traditional fossil fuels (Klasnja et al. 2006). This further reinforces their contribution to addressing the problem of global climate change (Niemczyk et al. 2019). In this regard, our findings are fully consistent with similar studies conducted in other countries – Sweden (Böhlenius et al. 2023), the United States (Hart et al. 2015), China (Hao et al. 2021), Great Britain (Aylott et al. 2008), and Denmark (Nielsen et al. 2014).

According to our research results, the rotation period for poplar plantations intended for biomass production for fuel or wood chips should be less than 7 years. Similar conclusions were made by Chinese scientists who studied the growth dynamics and biomass production in short-rotation poplar plantations of three poplar clones. They recommend that the best option for ground pulp timber production is to choose 6 years for rotation length, with a planting density of 833 or 1111 stems per hectare (Fang et al. 1999). The quantitative maturity of Toropohrytskyi poplar plantations, with an initial planting density of 4,000–6,000 seedlings per hectare in southern Ukraine, is reached at 4–5 years of age, with a wood stock of 80–85 m3∙ha−1 (Fuchylo et al. 2009), and in the northern part of the Right-Bank Forest-Steppe, at 5 years of age, the mean annual productivity of dry aboveground biomass in a Robusta poplar plantation is 8.84 t∙ha−1∙yr−1 (Bordus et al. 2024).

It has been observed that after the age of 8, poplar clones exhibit a stabilization in several important physical and mechanical properties of wood, such as basic density, fiber length and diameter, and cellulose content, and based on this, it has been suggested that the technical maturity of poplar plantations is about eight years for plywood and fiberboard. However, when the intended purpose of poplar plantations shifts (the cultivation of large-sized timber), which requires a 6 × 6 m spacing, quantitative maturity is reached within 14–17 years (Zhang et al. 2020).

Despite significant progress in studying the problem of creating and using of poplar species and cultivar plantations, several issues such as the feasibility of using transgenic poplars for the provision of ecosystem services (DesRochers et al. 2006; Sperandio et al. 2022; Thakur et al. 2021), the technologies for cultivating poplar plantations (such as the use of fertilizers and irrigation) (Xi et al. 2021), the selection of clones resistant to environmental stress (Biselli et al. 2022), and the use of specific categories of forest and non-forest lands for plantation establishment (Dimitriou et al. 2017) remain unresolved.

In Ukraine, continuing the development of new, highly productive poplar cultivars, which will also exhibit high drought resistance, remains an urgent task. Additionally, further research is needed on the role and methods of using poplar plantation forestry to address the effective utilization of lands affected by industrial and agricultural activities. This includes land reclamation, afforestation of areas impacted by hazardous emissions, integration of plantations into forest–agricultural landscapes, and biological land conservation, etc.

The poplar cultivars (‘Canadian-Balsamic’, ‘Tronko’, ‘Druzhba’, and ‘Strilopodibna’) tested on an experimental plantation in the conditions of the Western Forest-Steppe over 15 years demonstrated high growth energy in both height and diameter, as well as significant stem wood stock volume. At 15 years of age, the poplar cultivar ‘Strilopodibna’ exhibited the highest productivity (171 m3·ha−1), while ‘Tronko’ had the lowest productivity (111 m3·ha−1). The results of ANOVA and Fisher’s LSD test indicate that at this age, studied poplar cultivars do not show significant differences in average height, whereas the differences in average trunk diameter are statistically significant.

Poplar plantations serve as an important source of not only provisioning ecosystem services, such as timber and biofuel, but also regulating services, contributing to the ecological well-being of the population. By sequestering atmospheric carbon in their aboveground and belowground biomass, poplar cultivars can contribute to solving the problem of mitigating global climate change. Seven-year-old poplar plantations are capable of storing between 35 and 46 t·ha−1 of carbon, effectively removing between 128.5 and 168.5 t·ha−1 of CO2 from the atmosphere. At 15 years of age, these values increase further due to the positive accumulation of total biomass.

Poplar cultivars make a certain contribution to the balance of atmospheric oxygen through photosynthesis and respiration. During the first seven years, plantations of the studied poplar cultivars can generate an annual oxygen production of 12.0–15.8 t·ha−1.

The bioenergy potential of poplar plantations depends on the cultivar type and, at 15 years of age, ranges from 1239.9 to 1910.1 GJ·ha−1.

A comparison of trends in average annual values and current changes in the volumes of ecosystem services generated by poplar cultivars (carbon sequestration, oxygen production, and energy biomass) suggests that under the conditions of the Western Forest-Steppe of Ukraine, the age of maturity for maximizing ecosystem service provision occurs before the seventh year.