Vibration phenomena are commonly encountered in various aircraft processes such as taxiing, takeoff, flight maneuvering, weapon launch, and landing. These vibrations can lead to fatigue failure of aircraft components and significantly affect the service life of aircraft structures. The aircraft engine, as the most critical core component, plays a decisive role in overall reliability but is also one of the main sources of vibration. The connection between the engine and its fuel accessories is primarily achieved through bolted joints. The internal bolts of the engine are subjected to complex stress conditions, including high pre-tightening forces, explosive loads generated by gas combustion, and continuous engine vibrations. In addition, the high operating temperatures inside the engine create an especially harsh environment for bolts (Zhou, 2016). The performance of bolts directly affects the reliability of the engine and its fuel accessories, and consequently the safety and reliability of the entire aircraft. Fatigue fracture or failure of bolts can compromise the function of critical components, and in some cases, may lead to catastrophic personal and economic losses.

Fatigue performance analysis of bolts is therefore an essential element in the broader fatigue analysis of engine structures, particularly for key load-bearing bolts, and represents a fundamental area of research for ensuring flight safety. For example, Liu (2009) employed the finite element method to calculate the pre-tightening force of rotor connecting bolts in an aircraft engine, obtained the stress–strain distribution of the bolts, and analyzed their fatigue life. Ma (2014) compared and validated theoretical stiffness calculation methods for bolted connections subjected only to pre-tightening forces, and proposed an improved cylindrical model capable of more accurately determining the equivalent stiffness of fastened parts.

Building on these works, this paper proposes a method for estimating the random vibration fatigue life of engine fuel accessory bolts. A detailed connection model of the bolts within the engine fuel system was established, with excitation boundary conditions defined according to the assembly configuration. Frequency response and random response analyses were then performed to obtain the stress power spectral density (PSD) function of the bolt. Finally, based on the material’s S–N curve, and accounting for vibration loads combining broadband and narrowband excitations, the Dirlik method was applied to calculate the random vibration fatigue life of the connecting bolt, yielding an estimate of its service life.

Vibration fatigue refers to fatigue failure caused by structural resonance when dynamic alternating loads – such as vibration, impact, or acoustic loads – are applied, and the frequency bandwidth of the load distribution includes or approaches the natural frequency of the structure. In other words, it can be described as fatigue failure resulting from resonance induced by dynamic loads.

The vibration fatigue life analysis of a structure should begin with a dynamic response analysis under dynamic load excitation, followed by an estimation of vibration fatigue life based on the results of that analysis. With the development of random vibration theory and structural dynamics, linear vibration response calculation methods have become increasingly mature, and vibration fatigue life estimation has become an important part of vibration fatigue research (Song, 2014; Mei, 2014; Wang, 2009). Unlike conventional cyclic fatigue, where the load is typically deterministic, vibration fatigue involves random loading, and the structural response is also a random process. Methods for studying and analyzing it mainly include time-domain and frequencydomain approaches.

Time-domain analysis is a direct method for studying fatigue life, which evaluates the stress state of a structure by analyzing the statistical characteristics of the stress time history. According to cumulative damage theory, the fatigue life of materials depends only on stress amplitude and mean stress. The basis of time-domain analysis is cycle counting of random stresses, with rainflow counting being the most widely used method. After obtaining statistical information on stress, and combining it with the fatigue performance of the material, fatigue damage is calculated using either the nominal stress method or the local stress–strain method, and fatigue life is then determined based on cumulative damage theory. Time-domain analysis provides a direct and relatively accurate approach to fatigue assessment, but it requires significant computational effort. During testing, a high sampling frequency is needed to measure time-domain signals, and large storage capacity is required for recording and processing data. In terms of data handling, the complexity of the rainflow counting method makes it difficult to fully characterize its statistical properties. Moreover, accidental factors during data sampling can significantly affect fatigue life analysis. As a result, current research and applications of time-domain methods remain limited.

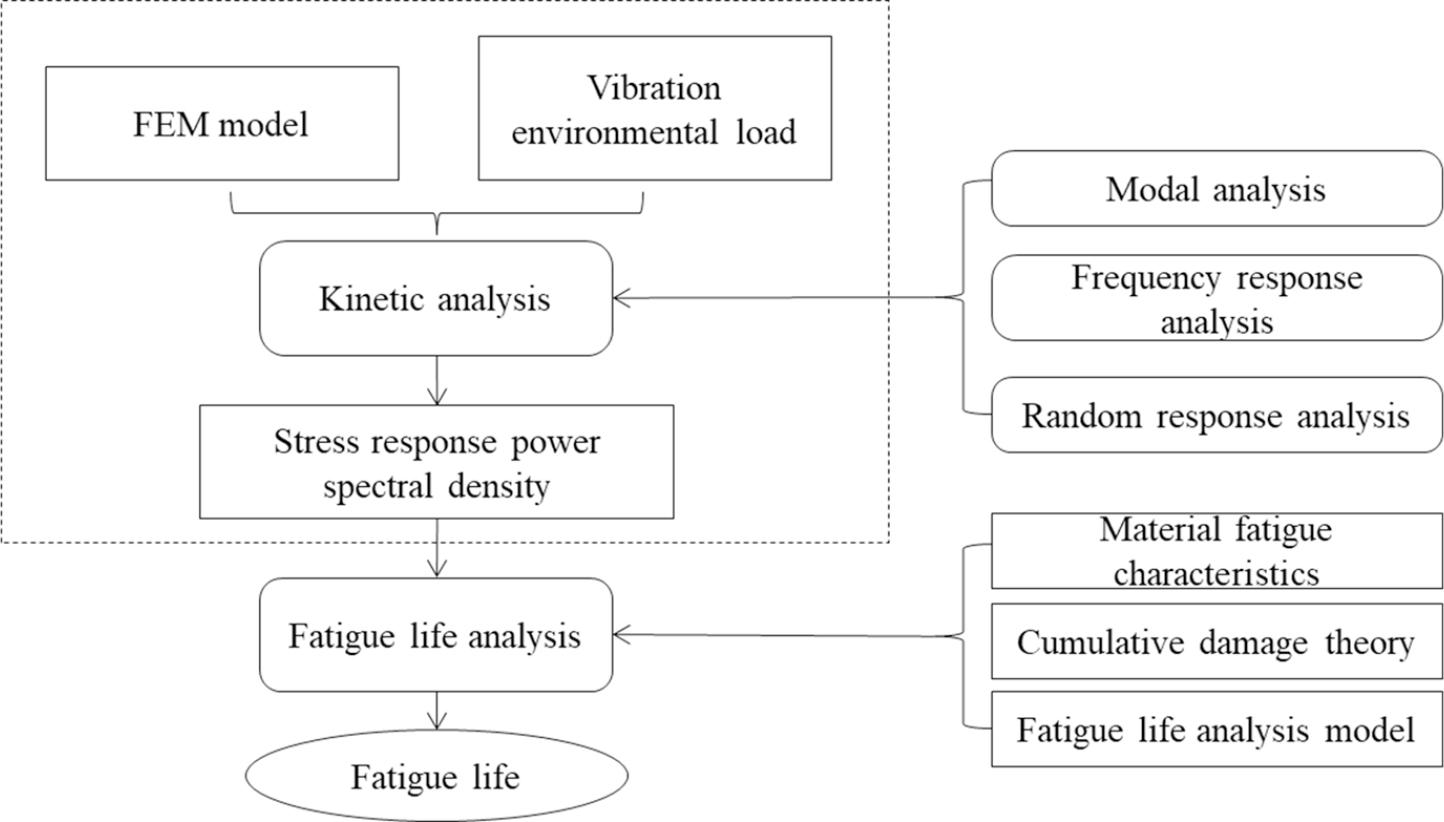

The frequency-domain method uses the response power spectral density (PSD) to represent stress information in the frequency domain, and then estimates structural fatigue life based on the material’s fatigue performance curve and cumulative damage theory. Depending on the statistical parameters used, frequency-domain methods can be divided into the peak distribution method and the amplitude distribution method. The peak distribution method is mainly applied to broadband Gaussian processes, while the amplitude distribution method relies on the rainflow amplitude distribution model, which captures the response of random processes and is directly used to estimate vibration fatigue life. Based on this model, two approaches are distinguished: the narrowband approximation method and the broadband distribution method. Many studies indicate that the Dirlik empirical formula outperforms other algorithms and is more broadly applicable to Gaussian stationary broadband stochastic processes. In fact, several commercial vibration fatigue analysis software packages are primarily based on this algorithm. Because of its simplicity and low computational cost, the present study employs the frequency-domain method to estimate the vibration fatigue life of engine connecting bolts. The flowchart of the frequency-domain approach is shown in Figure 1.

Frequency-domain method process for vibration fatigue analysis.

The power spectral density function Sx(ω) and its autocorrelation function of any sample function x(t) in a random process X(t) together form a Fourier transform pair:

Among them, the autocorrelation function Rx(τ) is defined as follows:

The correlation function describes the time-varying characteristics of a stationary stochastic process, also referred to as its time-domain characteristics. The power spectral density (PSD) function, on the other hand, describes the frequency-dependent characteristics of a stationary stochastic process, also referred to as its frequency-domain characteristics.

The PSD function can be expressed as either a bilateral (two-sided) or unilateral (one-sided) function. Formula (1) defines the bilateral PSD, Sx(ω). In practical engineering applications, because frequency is considered only in the non-negative range, and due to the even-function property of the bilateral PSD, the amplitude of the negative frequency range is symmetrically mapped to the positive frequency range. This leads to the unilateral power spectral density function, G(ω), expressed as:

The frequency unit commonly used in engineering practice is Hz, rather than rad/s as in mathematics. By letting f = ω / 2π, the form of the power spectral density function form commonly used in engineering can be obtained.

The n-th moment of inertia of the power spectral density function is defined as follows:

When n = 0, then

Formula (5) shows that the 0-order moment of inertia m0 is the area enclosed below the power spectral density function curve. Thus, the Root Mean Square (RMS) value of the random process can be obtained.

The moment of inertia also characterizes the important time-domain characteristics of stochastic processes x(t). The relationship between some time-domain parameters and their derivatives and the moment of inertia in the frequency domain is as follows:

In the frequency domain, the above moments of inertia are commonly used to approximate the zero mean forward crossing frequency E[0] and the peak frequency E[P].

The bandwidth factor αn is also an important parameter for describing the power spectral density function, defined as:

As shown in formula (9), αn is a dimensionless number, 0 ≤ αn ≤ 1, where n can take a non-integer value.

Specifically, when n = 2 in formula (9), the spectral irregularity factor γ and spectral width coefficient ε that describe the bandwidth distribution of the power spectral density function with frequency can be obtained as follows:

When ε → 0 (or γ → 1), it is represented as an ideal narrowband process (similar to a harmonic process). When ε → 1 (or γ → 0), it is represented as an ideal broadband process (similar to a white noise process).

Assuming the critical stress level is S, the expected critical crossing frequency is expressed as E[S]. The peak distribution function of a stationary Gaussian stochastic process at time t can be written as:

The probability density function of the peak can be obtained by taking the differential equation of formula (12), as follows:

Formula (13) can be used to obtain a more general representation of the peak probability density function, which is:

Where erf(x) is the error function:

When γ → 1, the peak probability density function of formula (14) can be expressed as:

Where 0 ≤ S < ∞. This peak probability density function exhibits a Rayleigh distribution.

When γ → 0, the peak probability density function of formula (14) can be expressed as:

According to the theory of structural fatigue damage, it is the amplitude of stress cycles – rather than the peak value – that causes structural damage. Therefore, in fatigue life analysis, the first step is to obtain the corresponding stress amplitude probability density function based on the above stress peak probability density function.

When the probability density function of the amplitude of the stress cycle is obtained, it can be concluded that n (Si) in the Miner linear damage accumulation formula is:

Where n (Si) represents the actual number of stress cycles during time T when the stress amplitude is Si, and p (Si) represents the probability density function when the stress amplitude is Si.

By substituting formula (18) into the S-N curve equation, the estimated value of damage can be obtained as follows:

When ΔSi → 0, formula (19) can be written in the following integral form:

Under random loading, the sequential effect of load cycles is generally negligible. It is commonly assumed that fatigue failure occurs when the accumulated damage reaches a critical value, DCR = 1. Therefore, the fatigue life of the structure can be derived as:

As shown in formula (21), the key to estimating the fatigue life of a structure using frequency domain analysis is to convert the power spectral density function of the stress response spectrum into the amplitude probability density function of the stress cycle.

In engineering, it is generally believed that when the spectral width parameter ε < 0.3, the stochastic process can be regarded as a narrowband process, and its amplitude probability density function is generally approximated as a Rayleigh distribution; When the spectral width parameter ε > 0.3, the random process is considered a broadband process, and its amplitude probability density function is relatively complex, with multiple descriptive models.

A system with an irregular factor close to 1 has a load time history that looks like an amplitude-modulated sine wave. In fact, there are no troughs above the average value of the signal, so for any given level S, the expected number of peaks above S is equal to the expected value of the positive intersection with S level. Therefore, for narrowband processes, the estimation of the fraction of cycles with peaks greater than x(t) = S is given by the following equation:

The probability [1 – pp(S)] that the peak value is less than S is defined as the distribution function of the peak value, and the derivative of this quantity yields the peak probability density function:

Therefore, for the special case of narrowband processes, the probability density function of the peak amplitude obtained will be a Rayleigh distribution function.

Since the peak frequency of the narrowband process is similar to the zero mean forward crossing frequency (i.e. the center frequency of the narrowband process), it can be assumed that E[P] = E[0]. Substituting formula (23) into formulas (19) and (20) yields the fatigue damage and life as follows:

When the expected damage is equal to 1, fatigue failure occurs.

Dirlik conducted simulations using the Monte Carlo method to study the power spectral density functions of 70 different spectral types. In Dirlik (1985), he proposed a quasi-empirical model that no longer uses a Rayleigh distribution to represent the probability density function of stress amplitude in broadband processes. It is believed that the probability density function of stress amplitude in broadband processes is a combination of an exponential distribution and two Rayleigh distributions. Then, based on the minimum regularization error between the model and the rainfall amplitude, relevant fitting parameters are extracted. The Dirlik equation is:

Where Z = S/σ is the regularized stress amplitude, and the other parameters in the equation are:

As can be seen from the above equation, the Dirlik equation involves four moments of inertia of the power spectral density function. Although the Dirlik equation did not take into account the influence of the mean values of each stress cycle, practice has shown that it usually provides relatively accurate life estimation results.

By substituting formula (26) into formulas (19) and (20), the fatigue damage and life can be obtained, and then expressed in the form of a Gamma function through mathematical transformation, that is:

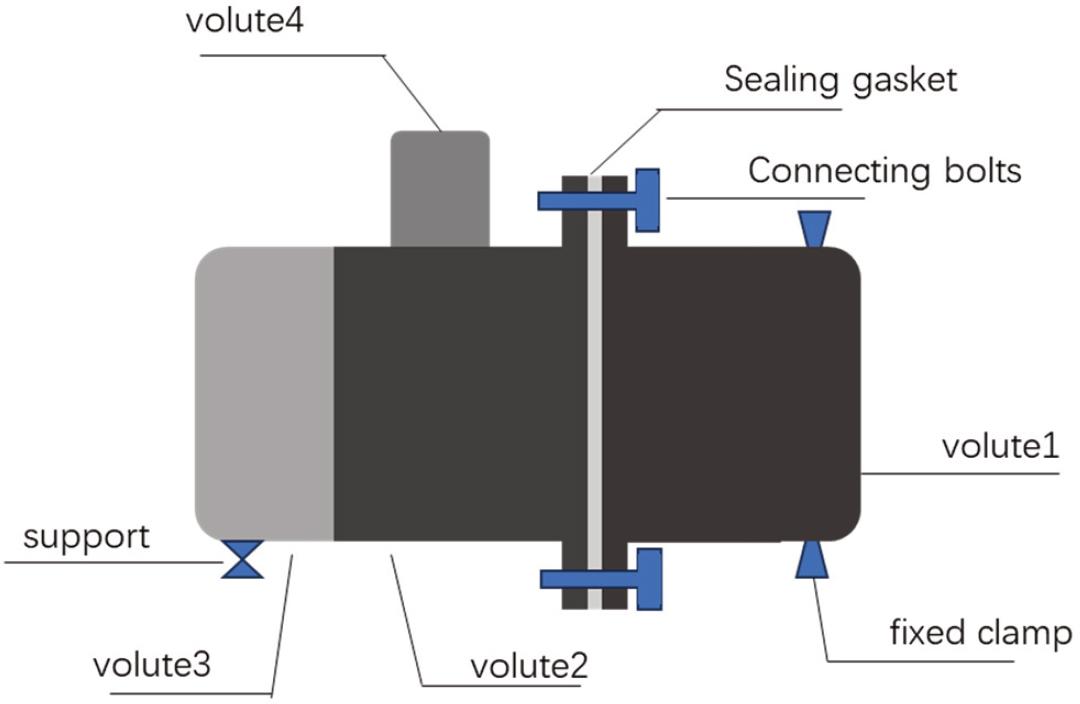

The fuel accessories of the aircraft engine examined in this study consist of four volutes, which are connected to each other using bolts and sealing gaskets. The volutes have transmission gears inside, and the bolt connection relationship is shown in Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of engine fuel accessory structure.

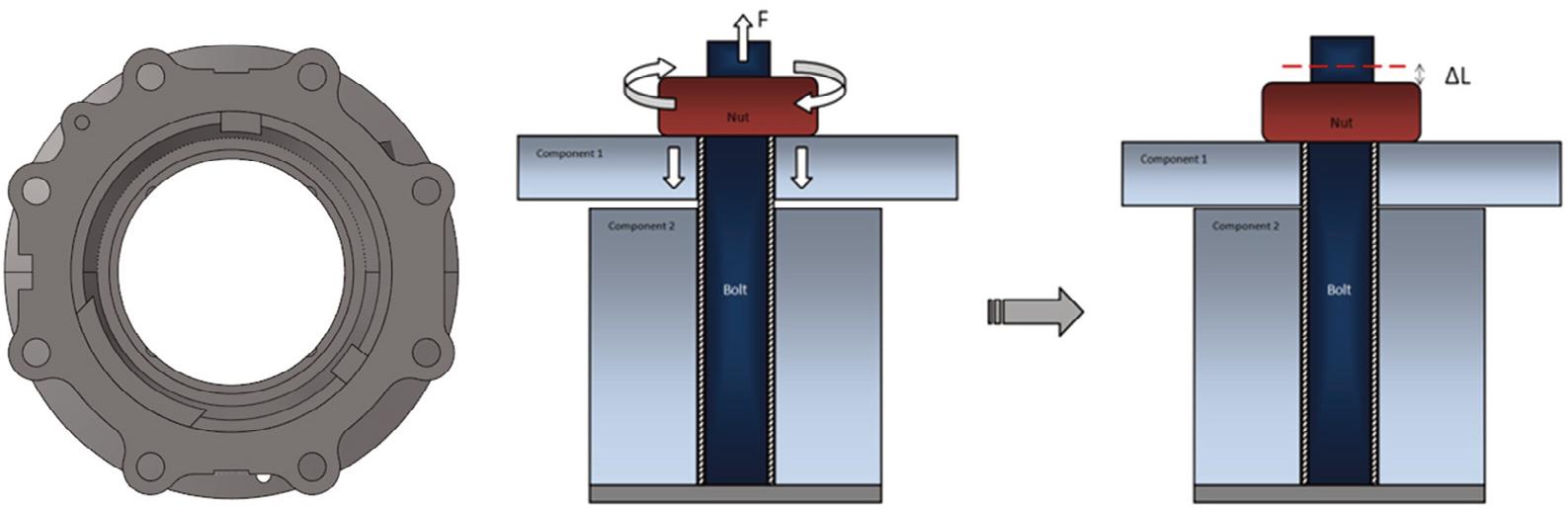

The primary research objective of this study is the fatigue life of the connecting bolts between volute 1 and volute 2, which are joined by eight bolts. Figure 3 illustrates the distribution of bolt positions and the bolt assembly. The connecting bolts are made of TC4, with a yield strength of 830 MPa (China Nonferrous Metals Industry Association, 2007). Each bolt has an M8 specification with a rod length of 32 mm. To reduce the computational scale of the finite element analysis, structures other than volute 1 and volute 2 were simplified using concentrated mass points, which were then connected to the model with MPC elements.

Distribution and assembly diagram of bolted connections.

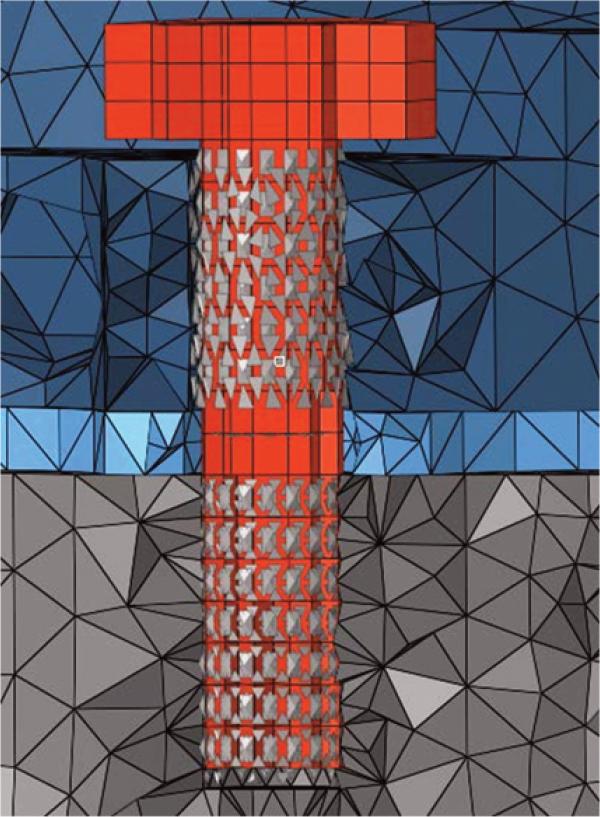

The part where the bolt engages with the shell uses a „binding” contact, and the sealing gasket between the two shells does not engage with the bolt or make contact with it. The interface of each component combination uses contact with friction coefficient, and the finite element model diagram of bolt connection assembly is shown in Figure 4. According to standard VDI 2230 of the German Institute of Engineers (Verein Deutscher Ingenieure, 2014), the pre-tightening force of bolts is usually 70% of the yield strength of the material, the effective cross-sectional area of the bolt is about 36.6 mm2, the yield stress of TC4 material is 830 MPa, and the pre tightening force is about 21265N.

Schematic diagram of bolt connection details.

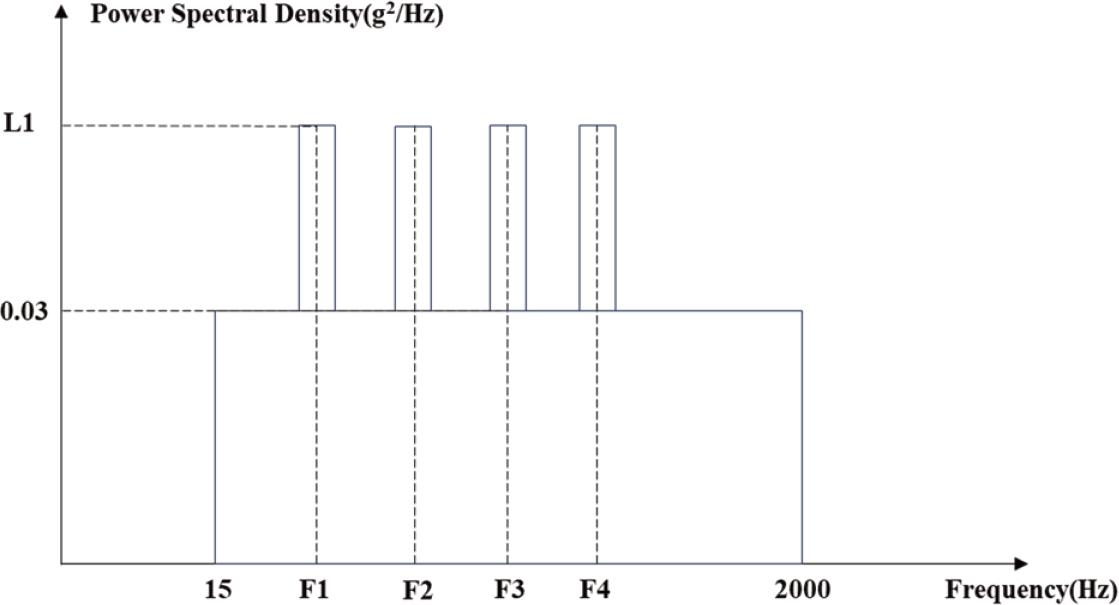

The environmental spectrum of random engine vibration consists of a combination of broadband and narrowband components, as shown in Figure 5. The acceleration power spectral density (PSD) function is defined as follows: L1 is taken as 1.0 g2/Hz, F1 as 188 Hz, F2 = 2F1, F3 = 3F1, F4 = 4F1, Peak bandwidth = ± 5%. Note: when inputting this curve, the acceleration PSD dimension should be converted from g2/Hz to (mm/s2) 2/Hz, that is, multiplying the values in the figure by 98,002 = 9.604 × 107. Apply acceleration excitation to the X, Y, and Z axes during analysis and calculation.

Vibration excitation spectrum

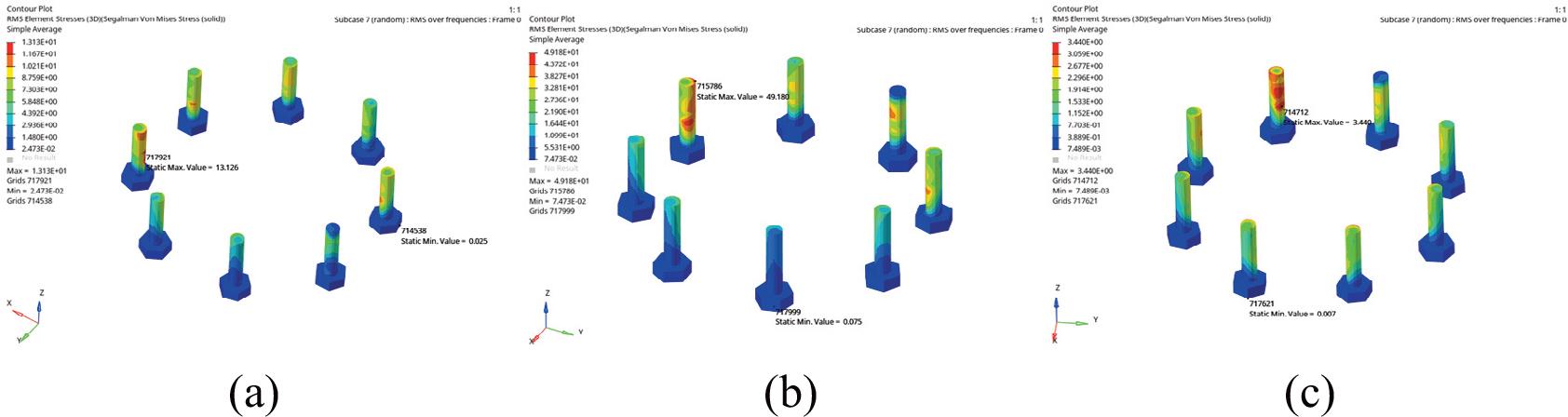

Following the procedure outlined in the diagram, a dynamic analysis of the structure was carried out, consisting sequentially of modal analysis, frequency response analysis, and random response analysis. The root mean square (RMS) stress results for the connecting bolts are shown in Figure 6.

RMS stress cloud maps of connecting bolts: (a) X-direction, (b) Y-direction, (c) Z-direction.

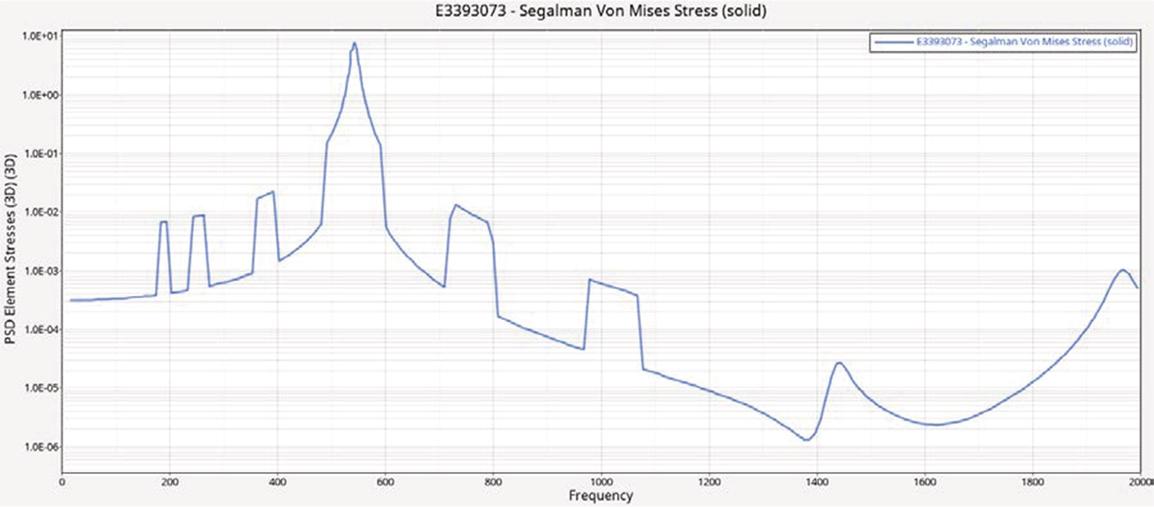

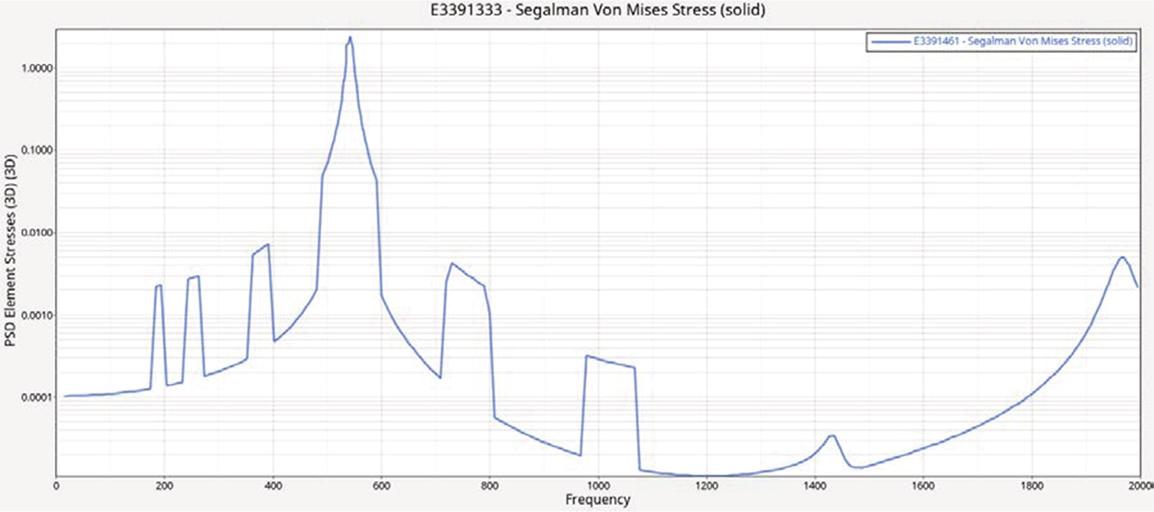

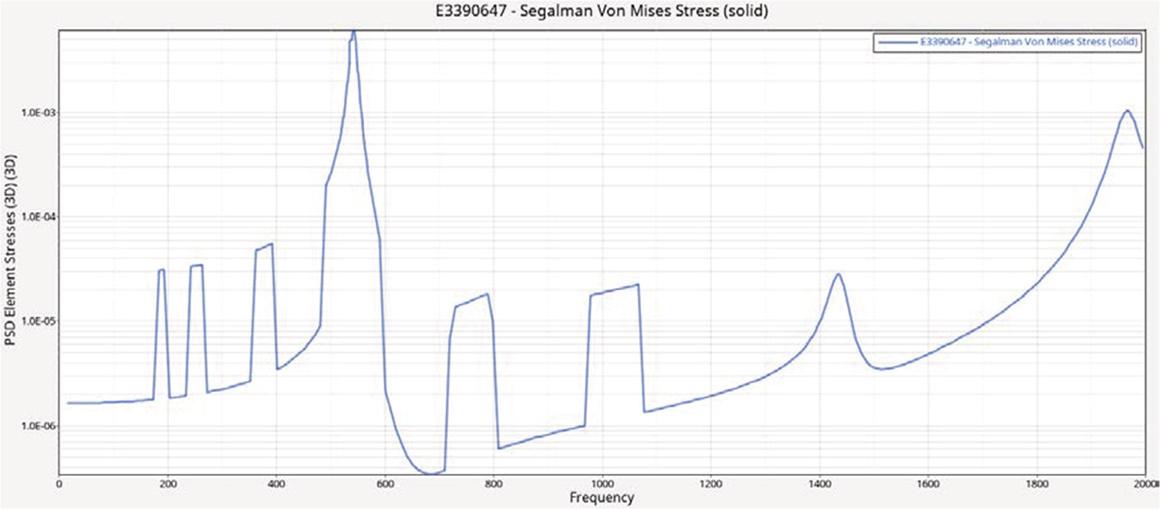

The stress power spectral density (PSD) curves at the critical points of the structure under different excitation conditions are presented in the following figure.

Stress PSD curve of dangerous points in the X direction.

Stress PSD curve of dangerous points in the Y direction.

Stress PSD curve of dangerous points in the Z direction.

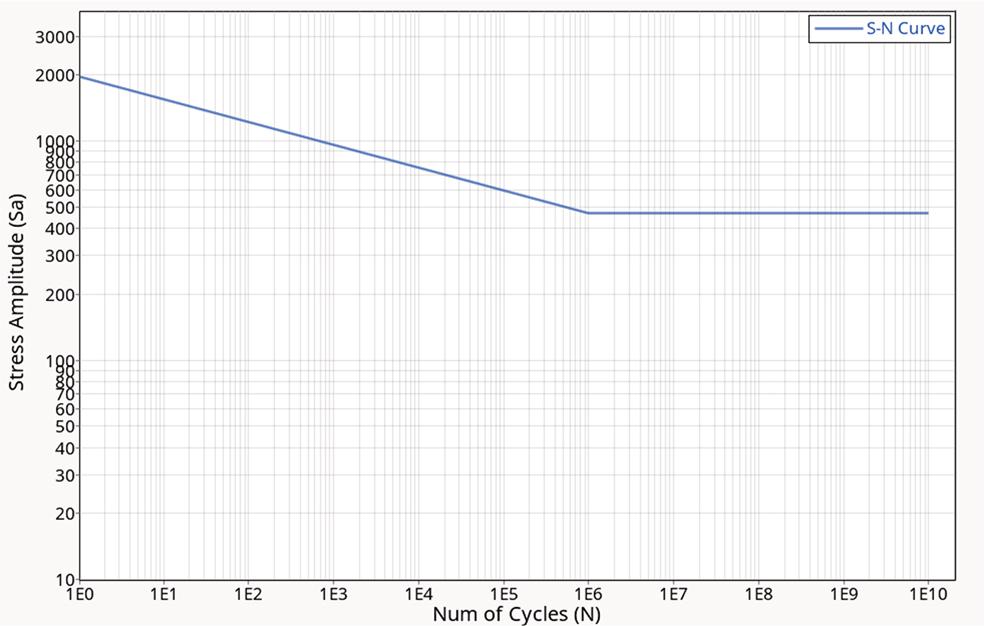

The S–N curve of TC4 material is shown in Fig. 10, where the fatigue strength coefficient is 1973 Mpa, the first fatigue strength exponent is -0.104, and the fatigue limit is 468.95 Mpa.

S–N curve of TC4 material.

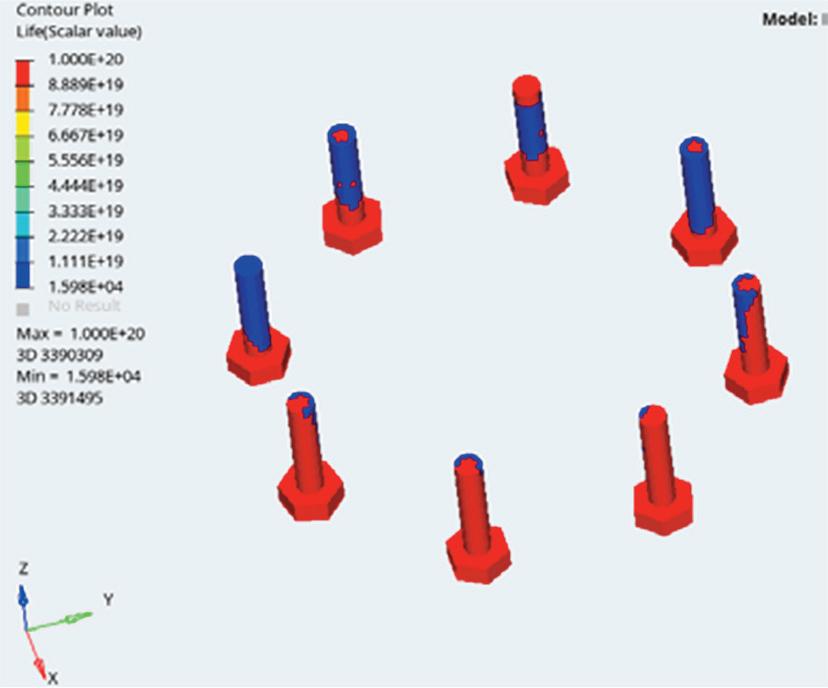

Under random vibration analysis, the RMS stress in the Y-direction was found to be the highest, resulting in the shortest fatigue life. Under these most critical conditions, the estimated fatigue life is 1.598 × 104 seconds, or approximately 4.44 hours, as shown in the figure. This service life is relatively low and does not meet design requirements. Therefore, a bolt model with higher fatigue strength should be selected during the design stage.

Fatigue life results of connecting bolts.

To address the problem of bolt fatigue failure caused by aircraft engine vibration, this paper has proposed a frequency-domain method for estimating the random vibration fatigue life of engine fuel accessory bolts:

The bolted connection structure was simplified, and detailed finite element models of the bolted joints were established.

A dynamic analysis was performed, including modal analysis, frequency response analysis, and random response analysis, to obtain the root mean square (RMS) stress at critical points.

The fatigue life of the critical bolt locations was calculated using the Dirlik method, based on the material’s S–N curve.

Compared with experimental testing, the proposed method enables rapid evaluation of bolt fatigue life under random vibration environments, providing a practical reference for bolt selection in engine design.