An aircraft is composed of several primary components – wings, fuselage, tail, landing gear, and engines. Of these, the wings are the most critical, as they generate lift, which makes flight possible. To fulfil their function, wings must satisfy stringent structural requirements, particularly strength, to withstand the loads and forces encountered in service. The wing structure must therefore be exceptionally robust, with internal components designed to resist all stresses that arise under a wide range of conditions, including take-off and landing.

Fig. 1 presents a preliminary study of the structural strength of the wing. The presence of inspection holes in the lower wing surface can significantly influence the fatigue life of the component. While essential for structural checks, these openings also create stress concentrations that weaken the surrounding material, especially under dynamic loading. Repeated stress cycles at these points can initiate cracks, progressively reducing fatigue life. If left unchecked, such cracks may propagate and ultimately lead to catastrophic failure and total loss (Dewa et al, 2023; Dewa & Kepka, 2021; Fatemi, 2009, 2010).

(a) Stress Analysis Results on the Wing of the STOL Aircraft; and (b) Center Wing Box.

In this study, a Finite Element Method (FEM) modification is performed by introducing rivet (fastener) holes around the inspection hole to analyze stress concentrations during the operation of a new-generation Indonesian short take-off and landing (STOL) aircraft. The research evaluates fatigue damage at these rivet holes using the Palmgren–Miner equation in combination with the S–N curve (constant load) for aluminum 2024-T3, with the corresponding stress concentration factor (Kt) included. The fatigue life of the lower wing structure – specifically at the rivet holes surrounding the inspection opening, identified as a critical crack-initiation site – is then calculated. Finally, a scatter factor is incorporated to account for external uncertainties in predicting fatigue life.

When predicting the fatigue life of an aircraft structure, the local stress–strain approach is often used as a simpler and more accurate method. Its basis is the assumption that the local fatigue response of a material at critical points – where cracks initiate – is comparable to the response of small, standardized specimens subjected to the same stress and strain cycles. This makes it possible to determine the cyclic stress– strain behavior at critical material locations using simplified specimen geometry and idealized loading patterns that replicate the actual loads applied to the component. Fatigue damage is assumed to occur at the critical point of the structural element – the crack initiation site – where cyclic hardening, cyclic softening, and sequential loading are simulated (Dewa et al., 2023). To apply this method correctly, it is also necessary to account for elastic–plastic behavior (Maksimović, 2025).

Principal stresses represent the maximum and minimum normal stresses acting on an element when it is oriented such that shear stresses vanish. The concept of principal maximum stress is fundamental in structural analysis, as it defines the highest stress a structure may experience. Stresses within a component may arise from various sources, including applied loads, shear forces, and thermal effects, making it vital to identify the points where maximum stress occurs. The principal stress concept enables this by specifying both the magnitude and direction of the maximum stress. Typically, a stress matrix is used to describe all stress components at a given point in the structure, from which the principal stresses (σ1, σ2) can be calculated. The principal stress is given by the following equation:

The Finite Element Method (FEM) is a numerical technique widely used to solve engineering and physical problems. As Hendra (2013) states: “In the finite element method, modeling is performed by dividing the model being analyzed into several elements, and these elements serve as the basis for calculations and analysis.” The general steps of FEM involve subdividing the model into smaller elements, representing each element with a simple model (for example, a spring model where stress is proportional to deformation), and applying the governing law of the element. The elements are then assembled into a system of equations that account for all variables. This procedure can be expressed as:

{k} – Matrix of stiffness

{u} – Vector of displacement

{f} – Vector of node

The first step is to identify the regions of the component most vulnerable to metal fatigue. Stress analysis then plays a crucial role in developing alternative solutions to minimize stress concentrations and reduce the likelihood of fatigue failure. Stress concentrations are well established as a major factor in fatigue and remain central to advances in fatigue life prediction. For example, Teng and Chang (2003) applied FEM to a base plate with a central hole, in work comparable to that of Maksimović (2005).

In FEM simulations, rivets are also modeled to capture the forces experienced during flight. For structural analysis, rivets in the lower skin of the aircraft wing can be represented using the HUTH (Hancock–Useless–Talbot–Hawkins) calculation method. This approach determines rivet stiffness and shear strength characteristics, making it possible to account for their role in supporting loads and transferring shear forces between structural panels. By applying the HUTH equation (Eq. 3), rivet modeling can be carried out more accurately, producing FEM results that more closely reflect the actual behavior of the aircraft wing structure.

In the analysis, the variables are defined as follows: E1 – upper membrane modulus of elasticity, t1 – shell thickness, E2 – lower membrane modulus, t2 – spar thickness, E3 – rivet modulus of elasticity, d – rivet diameter, a, b, n – joint-related coefficients. Specifically, n = 1 for single shear and n = 2 for double shear, as shown in Table 1. Finally, F indicates the force acting on the rivet, measured in Newtons.

Coefficient values for different types of joints (Huth, 1986).

| Joint type | Coefficient values | |

|---|---|---|

| Single shear joint | n = 1 | |

| Double shear joint | n = 2 | |

| Bolted metallic | a = 2/3 | b = 3.0 |

| Riveted metallic | a = 2/5 | b = 2.2 |

| Bolted graphite/epoxy | a = 2/3 | b = 1.2 |

In experiments designed to determine the fatigue life of structural materials, load spectra are a crucial source of input data for evaluating fatigue resistance. A load spectrum captures variations in the amplitude and frequency of loads applied to a structure over time. Experimental data from operational environments – including vibrations, pressures, and cyclic loads – are compiled into a spectrum to represent the real conditions experienced by the material. Using load spectra in fatigue testing provides a more realistic assessment of how a structure will respond to variable loading throughout its service life.

When a component contains discontinuities such as holes or notches, the stress distribution around these regions becomes uneven. Stress near discontinuities is typically higher than the average stress in areas far from them. To generate an appropriate S–N curve, the stress concentration factor (Kt) can be determined by comparing the maximum stress with the far-field stress obtained from finite element simulations. According to Konieczny et al. (2019), the stress concentration equation is expressed as follows:

Stress max refers to the maximum stress experienced by the material during a load cycle. This value represents the peak stress that the material encounters under the applied loads. Stress farfield is the maximum stress that the material can endure without failure over an infinite number of cycles. This value indicates the stress level at which the material remains safe and does not fail, regardless of the number of load cycles applied.

The Palmgren-Miner rule is applied to assess fatigue damage under a spectrum of repeated loading with varying amplitudes. This rule was also utilized by Maksimović (2005) to estimate fatigue damage caused by various amplitudes of cyclic loading, which represents the stress that the structure and aircraft components must endure throughout their service life. The Palmgren-Miner rule is expressed by the following equation:

In this study, Eq. 5 will be adapted to align with the stress-life approach for estimating fatigue life. The design stress spectrum used is derived from the stress-time data in this study, and it is represented by a bilinear S–N curve. The stress range below the material’s fatigue strength is considered in the analysis by using a modified Haibach model to account for increased damage due to lower stresses. The resulting fatigue life (in cycles/mileage) can then be determined using the following formula (Dewa et al., 2023; Dewa & Kepka, 2021):

This formula takes into account the contributions of varying stress ranges to the overall fatigue life, providing a more accurate estimate of the component’s endurance.

The scatter factor is a statistical divisor applied to fatigue test results to account for the variability in fatigue performance across structures consisting of multiple components. It addresses factors that are challenging to predict accurately, as fatigue performance can vary due to material quality, structural design, and environmental conditions (Kasim, 2025; Aziz et al., 2022; Liao et al., 2020). Incorporating the scatter factor into fatigue analysis accounts for these variations and provides a more accurate estimate of a structure or component's fatigue life. According to MMPDS (Metallic Materials Properties Development and Standardization) (Federal Aviation Administration, 2024), this approach helps ensure that the predictions of fatigue life are more reliable and reflective of real-world conditions. Table 2 shows scatter factor for Aluminum structures.

Full-Scale Fatigue Test Scatter factor for Aluminum structures (Federal Aviation Administration, 2024).

| Notes | Number of tests specimens | Required scatter factor |

|---|---|---|

| Probability of Detectable crack-free safe-life 99.97% (Zp = 3.511) | 1 | 4.96 |

| 2 | 4.0 | |

| 3 | 3.70 | |

| 4 | 3.54 | |

| Standard Deviation of Log fatigue life | ||

| 0.14 for Aluminum structures | ||

Zp is the Z-value, representing the number of standard deviations an observation lies from the mean for a given set of data.

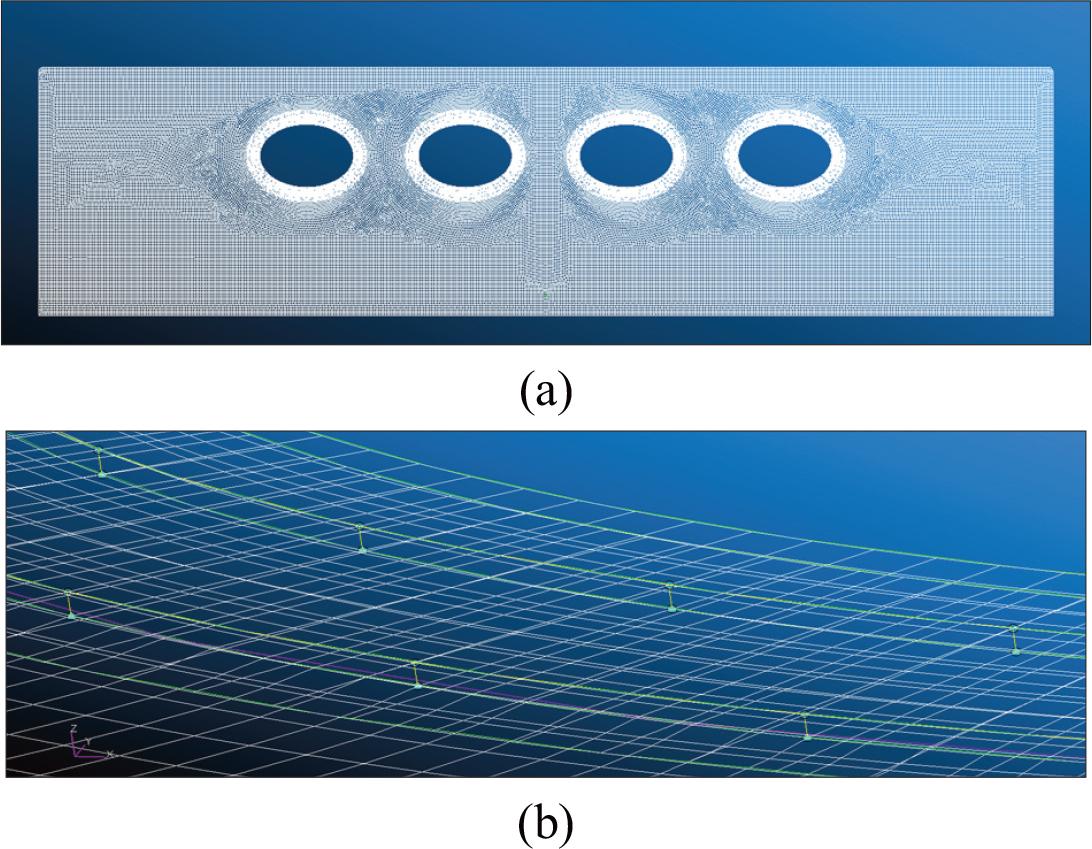

In this study, a numerical simulation was carried out as a static analysis during the cruising phase of the aircraft, representing the dominant load conditions. Tables 3 and 4 present the input dimensions and material properties for the STOL aircraft. The objective of the simulation is to determine the stress distribution around the inspection hole. This stress data is then used to identify the placement of rivets in critical areas for further analysis. Because the research focuses specifically on the fatigue life of rivet holes surrounding the inspection hole, the finite element model is limited to the lower wing skin. The model includes only the skin and doubler components, which are represented using shell elements. This approach is shown in Fig. 2, which illustrates the finite element model.

(a) FEM modelling for the lower skin of an aircraft wing; (b) Rivet element modelling.

Dimensions of the Lower Skin.

| Geometry | Value |

|---|---|

| Length of Lower Skin | 2600 mm |

| Width of Lower Skin | 591 mm |

| Hole Inspections | 240 × 150 mm |

| Rivet Diameter | 3.97 mm |

| Skin width | 2 mm |

| Doubler width | 1.5 mm |

Material properties of Aluminum 2024-T3 (MSC Software Corporation, 2024).

| Properties | Value |

|---|---|

| Modulus Young | 70 GPa |

| Poisson Ratio | 0.33 |

| Yield Stress | 360 MPa |

| Yield Ultimate | 488 MPa |

| Elongation strain | 23% |

| Hardening coefficient | 450 MPa |

| Hardening exponent | 0.072 |

| Ductility coefficient | 0.409 |

| Ductility exponent | -0.713 |

| Fatigue coefficient | 927 |

| Fatigue exponent | -0.113 |

In the finite element analysis, 1D elements are introduced to represent rivets that connect the skin to the doubler. Rivet constants are defined using the Huth–Schwarmann method, yielding values of k2 = 25,231.2 and k1 = 247,446.1. These constants are used to determine the direction of the forces acting on the rivets. After defining the material properties of both the lower skin and rivets, a tensile test simulation was conducted by applying a 350 N force to the right and left ends of the element. This load was calculated based on the average stress experienced during the aircraft’s cruising phase.

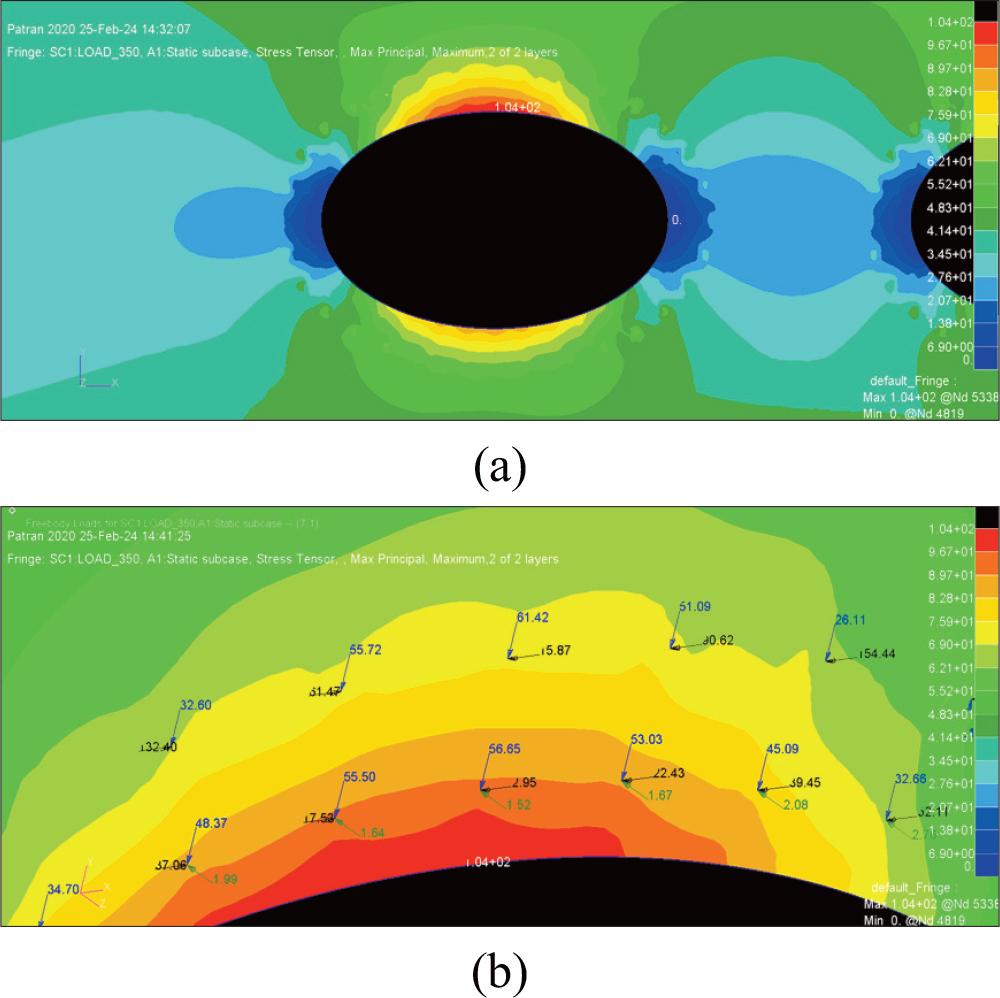

Based on the numerical simulation results, Fig. 3(a) shows that the highest stress occurs at the top of the inspection hole, with a maximum value of 104 MPa – approximately three times higher than the far-field stress of 35 MPa. Fig. 3(b) presents the reaction forces on the rivet along the three coordinate axes (x, y, and z). These six reaction forces, corresponding to rivets located in critical areas, are used as input for the rivet hole simulation.

(a) Stress concentration on the skin; (b) Rivet reaction force.

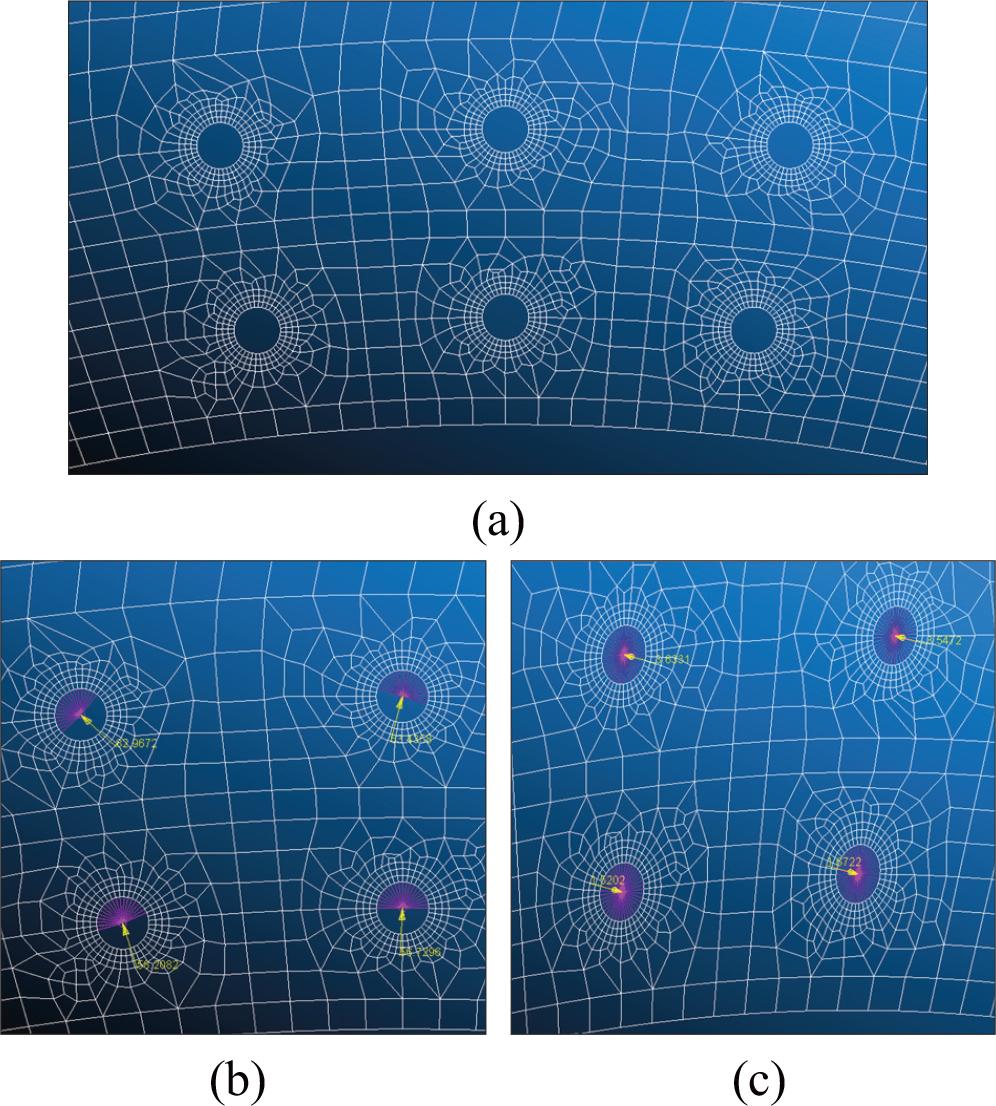

A second numerical simulation was then performed by adding rivet holes to the previously developed element model and applying the same tensile load as in the initial analysis. The purpose of this simulation is to determine the highest stress concentrations around the rivet holes. Fig. 4(a) shows the updated model of the lower skin with six rivet holes placed around the inspection hole. The rivet holes are modeled with higher geometric detail to achieve more accurate stress predictions. Figs. 4(b) and 4(c) illustrate the application of reaction forces on the rivets: in-plane forces aligned with the rivet hole plane and out-of-plane forces acting perpendicular to the surface.

(a) Element generation after hole addition; (b) Application of in-plane rivet reaction force; (c) Application of out-plane reaction force.

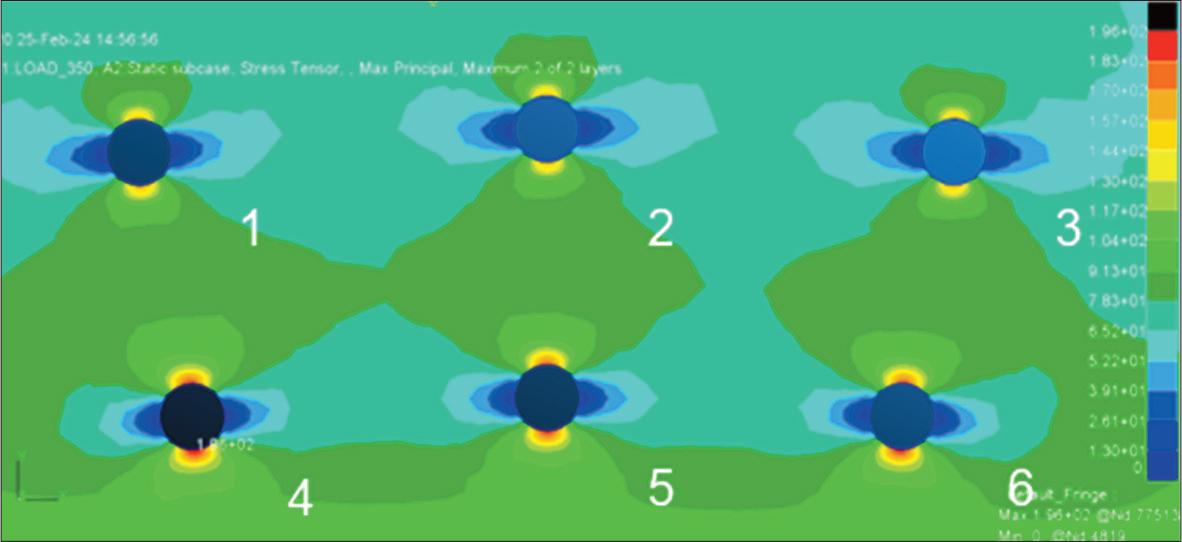

Fig. 5 shows the simulation results for the rivet holes, indicating that the highest stress concentration occurs at rivet hole number 4, at the bottom of the hole, with a maximum value of 196 MPa – 5.6 times higher than the far-field stress of 35 MPa. This stress concentration value is then used to determine the material’s S–N curve based on the MMPDS (Federal Aviation Administration, 2024). However, the MMPDS only provides stress concentration factors in the range of kt = 1 to kt = 5. To reconcile this, the stress value in the spectrum data must be multiplied by 1.12, ensuring that the far-field stress, when multiplied by the ktkt value, corresponds to the maximum stress obtained in the analysis.

Stress concentration at rivet holes.

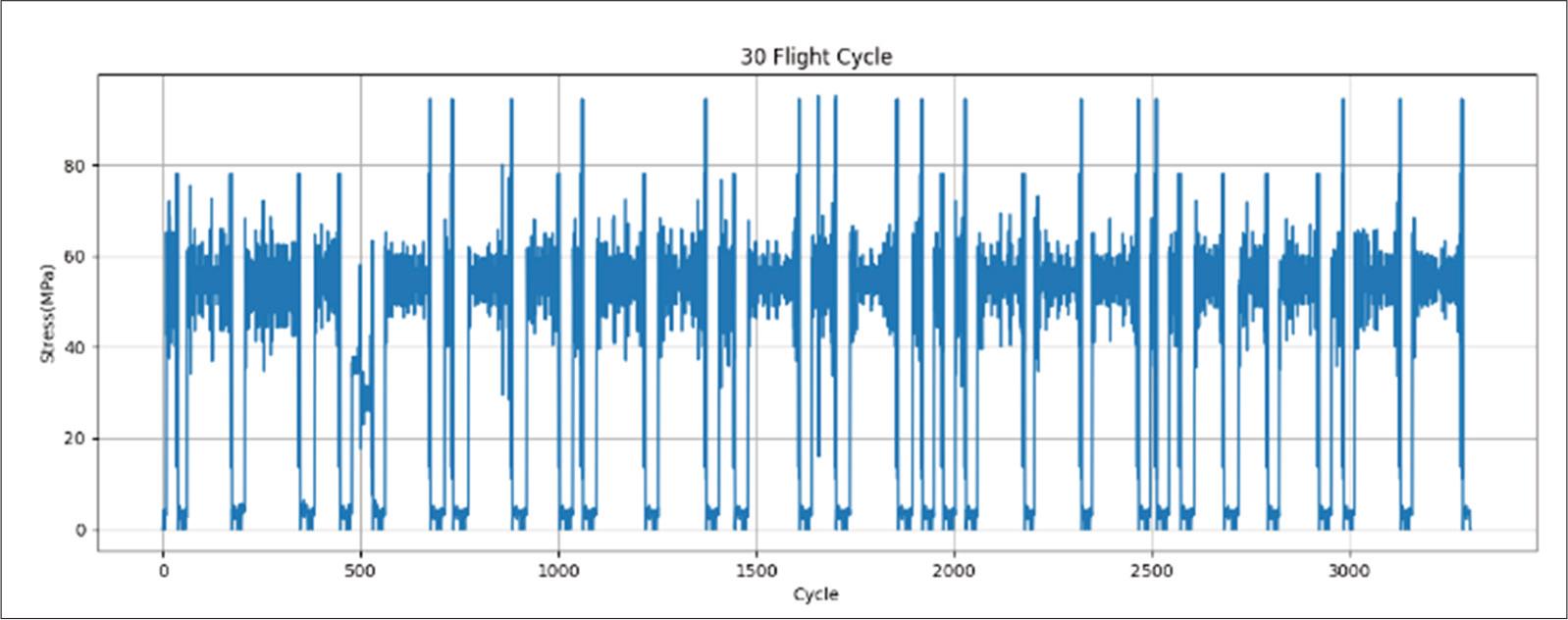

Fatigue life analysis requires stress spectrum data representative of the loads experienced by the lower wing skin during flight. The cyclic loads considered in this study include those from ground operations, gusts, and maneuvers. Ground operation loads arise from uneven surfaces; gust loads result from wind disturbances that cause turbulence; and maneuver loads occur during pitch, yaw, and roll motions. The data used here were obtained directly from strain gauges installed on the lower wing skin. Fig. 6 presents cyclic load measurements collected over 3,000 flights. After acquiring the cyclic load data, the loads were compiled into a stress spectrum using an algorithm. In this study, the stress spectrum shown represents 30 flights, illustrating the cyclic load patterns as a representative sample. It is assumed that the repeating load patterns observed in the graph are consistent with those experienced in service and therefore represent a total spectrum equivalent to 30,000 flights.

Load spectrum from flight test.

The final step involves calculating the fatigue life of the lower wing structure including rivet holes using the Palmgren-Miner method. This method estimates the total number of cycles to failure of the structure due to cyclic loads by considering the contribution of each load cycle to cumulative damage (Tavares & de Castro, 2017; Talreja & Phan, 2019). To determine the number of cycles to failure.

The final step is to calculate the fatigue life of the lower wing structure, including rivet holes, using the Palmgren–Miner method. This method estimates the total number of cycles to failure by accounting for the contribution of each load cycle to cumulative damage (Tavares & de Castro, 2017; Talreja & Phan, 2019). To determine the number of cycles to failure (Nf) in accordance with MMPDS guidelines, the stress equation is modified to reflect cyclic loading conditions. Equation (7) provides the relationship specified in the MMPDS (Federal Aviation Administration, 2024):

The calculation of Nf from the minimal and maximal stress data obtained from the strain gauges was performed using algorithm software. This approach was chosen due to the large volume of data from the 3,000 simulated flight, which required programming tailored to the specific equations used. The calculation involved determining 1/Nf for each cycle and summing these values for each simulated flight. In the final stage, the sums for all 3,000 simulated flights were aggregated to obtain the total 1/Nf value for all load cycles. The program yielded a total 1/Nf value of 0.04428.

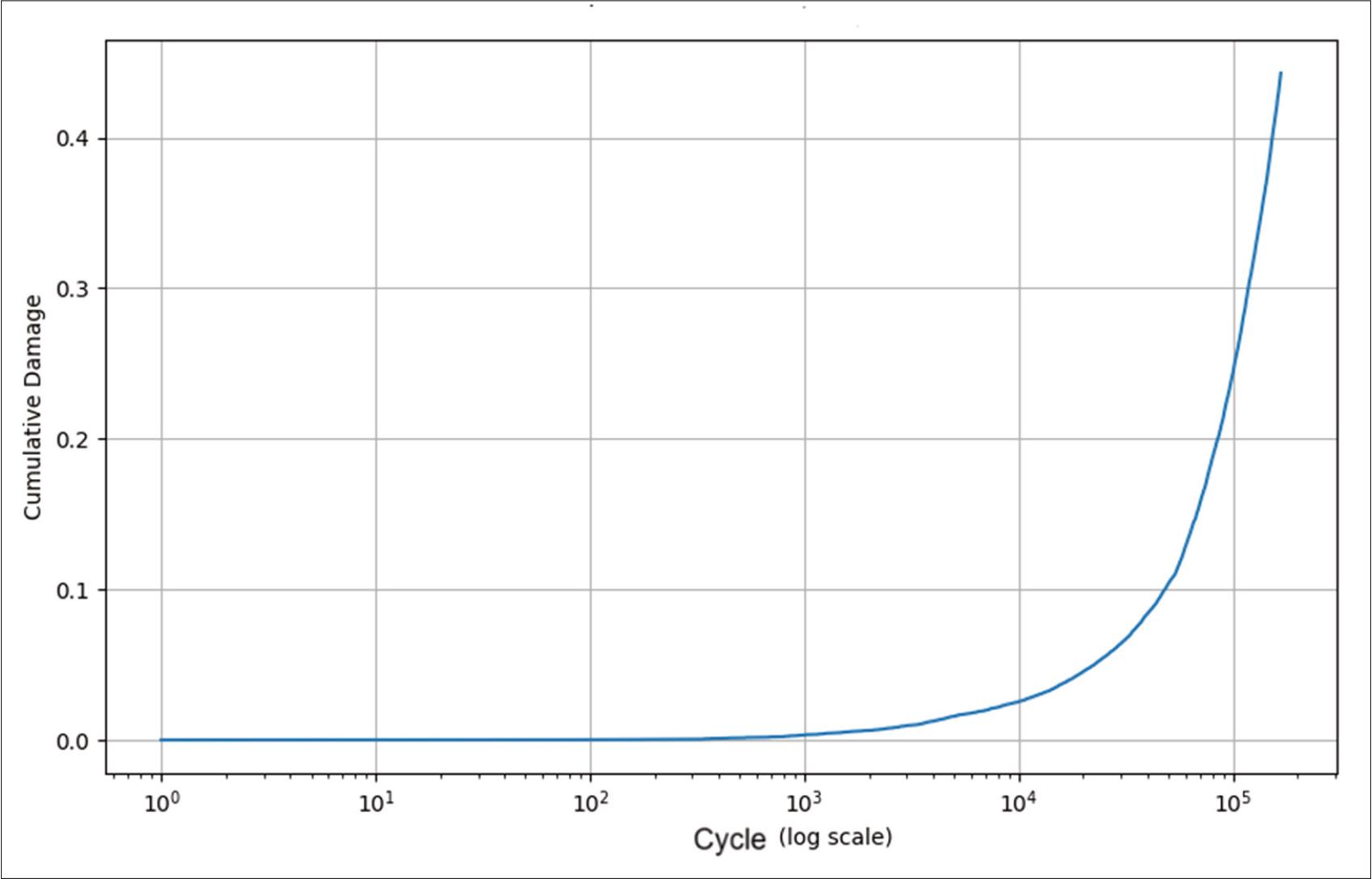

In this study, the manufacturer’s design target for the STOL aircraft was 30,000 simulated flights. To align with this target, the cumulative damage value obtained from the analysis of 3,000 simulated flight was multiplied by 10. This adjustment provides a more representative estimate of the fatigue life of the lower wing structure including rivet holes, under the operational target. Consequently, the updated cumulative damage value, after multiplying by the factor of 10 to reach the target of 30,000 simulated flights, is 0.4428. The cumulative damage curve for the rivet holes in the lower wing skin of the STOL aircraft is presented in Fig. 7.

Cumulative fatigue damage curve.

The cumulative damage result of 0.4428, or 44.28%, for the rivet holes in the lower skin indicates that significant damage develops over 30,000 simulated flights. Although this value is still below 1, which is the failure threshold, 44.28% is quite high in aviation terms and signifies that the rivet holes have experienced considerable deterioration. The curve shows that for load cycles between 103–104, the accumulation of damage increases gradually. However, between 104–105 load cycles, there is a steeper rise in damage accumulation. This steeper slope indicates that the material is entering a fatigue phase, where continuous cyclic loading accelerates degradation and increases the risk of failure over time.

Based on the fatigue life calculations, the result is 67,750 simulated flights. This suggests that cracks in the rivet holes are likely to initiate after the aircraft completes this number of cycles. The design life target set by the manufacturer for the STOL aircraft is 30,000 simulated flights. Therefore, the design requirement is satisfied, and the rivet holes can be considered safe under the established standards.

To ensure a higher level of safety, the fatigue life results must be adjusted using a safety (scatter) factor. The manufacturer follows the guidelines of the US Department of Transportation document “Fatigue, Fail-Safe, and Damage Tolerance Evaluation of Metallic Structure for Normal, Utility, Acrobatic, and Commuter Category Airplanes,” which sets standards for aluminum structures. According to these guidelines, a scatter factor of 5 is applied when only a single specimen is tested. Based on this requirement, the calculated fatigue life, when divided by the scatter factor, results in a revised service life of 13,550 simulated flights. To enhance structural safety, inspections of the rivet holes in the lower wing skin should therefore be conducted once the aircraft reaches this threshold. These inspections are essential for detecting cracks or other forms of damage that could compromise flight safety.

By following this inspection schedule, the manufacturer can ensure that the STOL aircraft remains safe and airworthy throughout its operational life. Extending the service life to 30,000 simulated flights would require reducing the scatter factor to 2.26. However, such a reduction would be a bold assumption given the simplified methodology used in the fatigue analysis. Achieving this level of confidence would require testing more than four specimens, which entails significant upfront investment. Nonetheless, establishing a clearly defined service life supports accurate lifecycle cost planning, which is particularly valuable for operators of smaller fleets or military trainer aircraft.

After conducting a series of analyses using FEM to determine stress concentration and the Palmgren–Miner method to calculate cumulative damage, it was found that the rivet holes experience 44.28% cumulative damage. The analysis also showed that the rivet holes can withstand up to 67,750 simulated flights. This result meets the target set by the manufacturing industry, which specifies a design life of 30,000 simulated flights for the STOL aircraft.

When a scatter factor of 5.0 is applied in the fatigue life calculation, the estimated service life is reduced to 13,550 simulated flights. Therefore, once the aircraft reaches this threshold, inspections of the rivet holes must be carried out to ensure their safety and structural integrity. The application of a scatter factor improves the reliability of fatigue life predictions and facilitates effective monitoring of structural wear, allowing timely preventive measures to be implemented to maintain overall aircraft safety and performance.

To reach the full design life of 30,000 simulated flights, the scatter factor would need to be reduced to 2.26. However, this assumption would be overly optimistic given the simplified methodology used in this study. Achieving such a reduction would require testing more than four specimens, which would involve significant cost.