Carbon fiber–reinforced thermoplastics have the potential to transform the aerospace sector in much the same way that composite materials once did. Replacing the currently used epoxy resin matrices with thermoplastic polymers offers a range of new advantages. Because thermoplastics can be thermoformed, they enable faster, simpler, and more repeatable manufacturing processes, ultimately improving cost-effectiveness (Dinu et al., 2022; Guo, 2018).

Another key benefit is the possibility of welding thermoplastics – not only to other thermoplastics, but also to resin-based composites (thermosets) or even metals. This approach makes it possible to create joints without mechanical fasteners such as bolts or rivets. Fasteners inherently require holes, which serve as natural initiation sites for cracks and have long been a concern for aircraft engineers. In addition, fasteners add weight and demand extra design, calculation, and installation time, all of which increase overall production costs (Ageorges et al., 2001; Sankaranarayanan & Hynes, 2019).

Adhesive bonding has traditionally been the preferred alternative. However, like rivets, adhesive joints cannot be disassembled without damaging the bonded components. They also involve long curing times, vacuum bagging, and autoclaves. Without automation, adhesive processes are difficult to reproduce, time-consuming, and labor-intensive—factors that further drive up manufacturing costs (Hoang-Ngoc & Paroissien, 2010; Loureiro et al., 2010).

A promising alternative is welding, which can be carried out using laser, ultrasonic, or resistance techniques. This study focuses on resistance welding. Specifically, aerospace-grade aluminum 7075 and carbon fibre reinforced polyamide plates were joined using this method. The research investigates the challenges of welding carbon fiber–reinforced thermoplastics to aluminum, as conducted at the Łukasiewicz Research Network – Institute of Aviation in Warsaw, Poland.

Resistance welding is a widely used method for bonding thermoplastics to themselves, and it has proven to be efficient and reliable (Geng et al., 2024). It offers a significant advantage over resin bonding due to the possibility of fully automating the process, similar to practices in the automotive industry (Curiel et al., 2023), leading to faster, more reliable, and cheaper production – reducing costs by up to 40% (Waśniewski, 2016). But how does this technique translate when “welding” thermoplastics with aluminum? The answer is not straightforward.

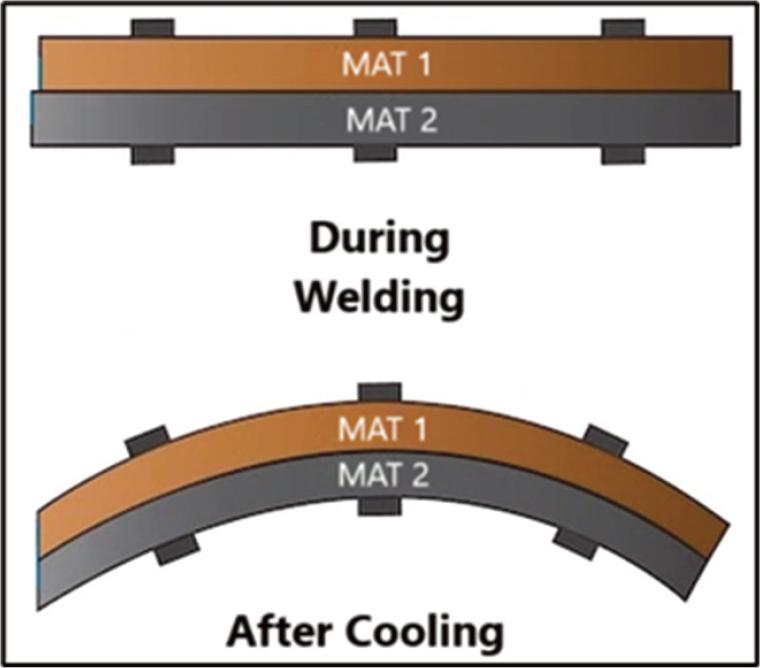

The key issue lies in the difference in the coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE). During the welding process, both materials experience thermal expansion. However, because of their differing CTEs, one material expands more than the other, and at the peak of this expansion, they begin to form a bond. As the materials cool, both bonded plates attempt to return to their original dimensions. The welded joint, however, restricts this movement, creating internal stresses that generate a bending moment and cause deflection (Figure 1).

The effect of thermal bending.

Figure 2 illustrates, in an exaggerated manner, the destructive forces caused by thermal stresses. As this visualization makes clear, it is crucial for aerospace engineers to understand the impact of these stresses. Proper measures must be taken to mitigate them to ensure the structural integrity and overall safety of the aircraft.

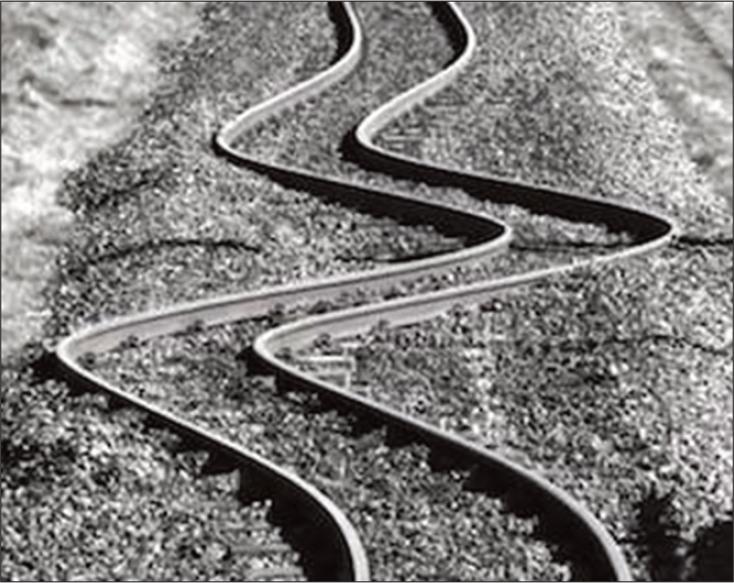

Railroad tracks bent due to linear thermal expansion (image source: https://thermtest.com/what-is-coefficient-of-thermal-expansion-how-to-measure-it).

When subjected to a thermal gradient, materials will typically expand; the change in the linear dimension can be estimated by Equation 1.

Where:

| Symbol | Description | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| ΔL | Change in length due to thermal expansion | mm |

| L | Original length | mm |

| αL | Linear coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) | [-] |

| ΔT | Temperature change | °C or K |

And the resulting thermal stress can be calculated by Equation 2.

| σ | Thermal stress | MPa |

| E | Young’s modulus | MPa |

These are stresses that can cause severe damage even to railway tracks – let alone thin and lightweight aircraft structures. Thermal stress can significantly affect fatigue life, particularly in airplane wings and fuselage, which are exposed to large temperature gradients between sunlit and shadowed regions, especially at high altitudes. This results in alternating compression and tension, similar to pressurization cycles, leading to low-cycle fatigue. These destructive stresses occur in constrained and heated materials with different CTEs.

In the panels welded for this study, thermal expansion was allowed to occur freely, but contraction during cooling was constrained by the weld. As a result, the panels were left with residual stresses – internal stresses that remain in a structure after the external forces or thermal gradients causing them have been removed. They exist even in the absence of external loading and can arise from various factors, such as welding. Residual stress can be classified as either macro stress (affecting larger areas) or micro stress (localized at the microstructural level). These stresses influence the material’s mechanical properties, including strength, fatigue life, and crack propagation, making their assessment crucial in engineering, particularly in aerospace applications (Tabatabaeian et al., 2022a). To properly evaluate the residual strength of the joints, it is essential first to calculate the internal residual stresses that weaken the connection.

Using software based on the Finite Element Method (FEM), a residual stress prediction can be reliably obtained. Thanks to advances in high-speed processors and the growing capabilities of numerical analysis software, determining the overall strength and durability of aircraft structures has become easier, faster, and more cost-effective than ever before. These tools have significantly improved the design of safer, more reliable aircraft. To achieve this, establishing a robust method for determining residual stresses that arise from various mechanical processes during aircraft manufacturing is crucial for accurate strength and fatigue assessments. In this study, the focus is placed on the welding process, with particular attention to specimens welded in the thermoplastic laboratory of the Łukasiewicz Research Network – Institute of Aviation.

Residual Stresses impact the bonds fatigue strength. Resistance welding provides a fast and efficient method for joining two components, but the localized heating during welding causes a sharp temperature rise, followed by rapid cooling to room temperature. This thermal cycle results in defects, misalignments, and residual stresses due to the restrained shrinkage of the heated zone by the surrounding cooler material. These residual stresses have a direct impact on fatigue crack initiation and propagation at welded joints (Teng & Chang, 2004a). Therefore, to fully assess the fatigue performance of a joint, it is essential first to determine the residual stresses – a process undertaken in this study.

When referring to the joining of metals with polymers, the term welding is not strictly accurate, as aluminum is never brought to its melting temperature and does not fuse with the polymer. However, as this joining process is commonly referred to as welding, this terminology will be used throughout this paper.

PA6 is a semi-crystalline thermoplastic with a melting temperature (Tm) of around 220°C and a glass transition temperature (Tg) starting near 50°C. During welding, polyamide must be heated to its melting temperature, at which point the heat energy breaks the hydrogen bonds between amide groups, destabilizing the crystalline lattice and causing it to break down. At this stage, the molten polyamide can penetrate the porosity of the aluminum surface, aided by the applied pressure from the actuator.

Directly welding PA6 to aluminum, however, is a challenging process due to several factors. The significant difference in the coefficients of thermal expansion (CTE) between PA6 and aluminum leads to residual stresses forming as the joint cools to room temperature. In addition, PA6 is hygroscopic and absorbs water; if heated without prior drying, hydrolytic degradation can occur, breaking amide bonds and reducing molecular weight. Exposure to temperatures above 300°C causes oxidation and material degradation, which lowers the mechanical properties of the polymer. Furthermore, postweld cooling must be carefully controlled, as a rapid drop in temperature reduces crystallinity and negatively affects joint strength.

For aluminum, with a melting temperature of approximately 660°C, the short-term heat exposure during welding (up to around 300°C) has only a marginal effect on its mechanical properties, resulting in a slight decrease in ultimate tensile strength (Alexander et al., 2014; Saruwatari et al., 2023).

Resistance Welding (RW) is a widely adopted technology for fast and modern manufacturing in the automotive and aerospace industries. It enables high-volume production with excellent repeatability. The process relies on Joule’s First Law, which states that the heat generated by an electrical conductor equals the product of its resistance and the square of the current:

Where:

Q – Heat generated, I – Current, R – Resistance, and t – time.

Fundamentally, RW involves passing an electric current through electrodes to the workpieces being joined. The resistance to current flow at the contact points generates localized heat, causing the material to soften or reach its melting point. Simultaneously, the application of pressure ensures that the materials form a tight connection while countering elastic deformation, thereby reducing the risk of trapping air bubbles inside the joint. This method can be successfully applied to both metals and thermoplastics.

In this study, the objective is to determine the level of residual stress within the aluminum and polyamide 6 (PA6) bonds. To achieve this, a dedicated resistance welding setup was prepared (Figure 3). Its key components include:

Power supply – provides the electrical energy necessary for heating the workpieces.

Electrodes – conduct the current and apply pressure; typically made of copper alloys to ensure high conductivity and durability.

Workpieces – the materials being joined, in this case aluminum and PA6 plates.

Control system – regulates current, pressure, and welding time to ensure consistent weld quality. (Mallaradhya et al., 2018; Stavropoulos & Sabatakakis, 2024)

Resistance Welding Station.

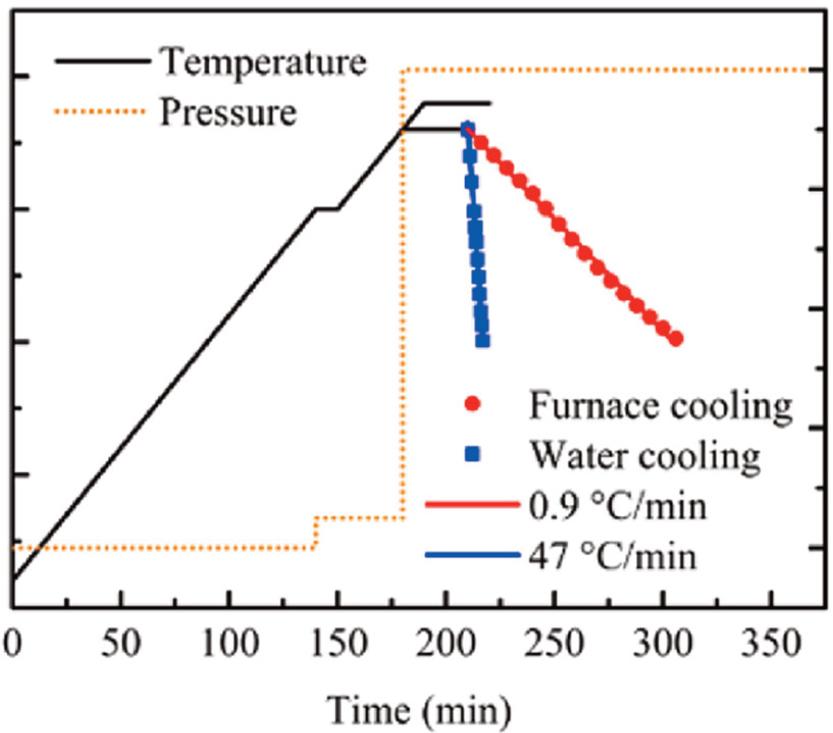

The process curve for fabrication (Zhang et al., 2023).

After careful preparation of the welding station, the next step is to plan the resistance welding process. Resistance welding relies on resistive heating to join materials by creating a molten layer at the interface. The generated heat allows the polymer chains to flow and intermingle under applied pressure, forming a strong bond as the joint cools and solidifies. The process consists of three key stages.

Heating: Components are aligned under pressure, and an electric current heats the interface, melting the polymer to enable bonding.

Consolidation: Current is maintained to ensure complete melting and fusion.

Cooling: The current is adjusted for controlled cooling, solidifying the joint.

In some resistance welding processes, the applied pressure is varied – starting lower during heating and increasing during cooling – to enhance bond quality. This approach ensures precise thermal and mechanical control throughout the welding process (Guillén & Cantwell, 2002; Li et al., 2021; Stankiewicz et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2023).

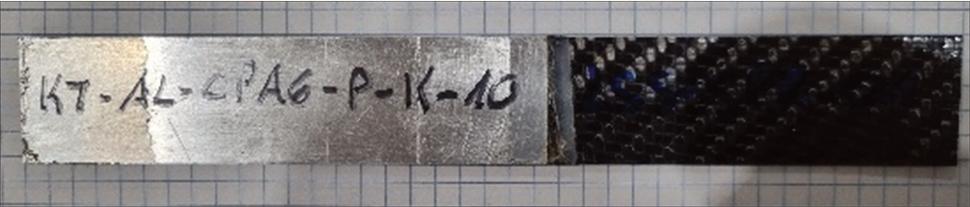

After following this detailed resistance welding procedure (for more information on the welding process, please refer to the cited sources), the Resistance Welded CF/PA6– Al7075 samples were prepared (Figure 5). These samples formed the basis for the FEM model used in the residual stress calculations. Figure 6 shows a deflected sample, where the observed deflection results from the residual stresses accumulated during welding.

AL-CPA6 RW Sample.

Deflected sample.

These samples will later undergo uniaxial tension testing, which will provide crucial data on the residual strength of the welds. However, before performing these tests, it is important to understand the internal mechanisms governing the joint’s behavior. The parameters of the prepared samples are summarized in Table 1. The last column presents the measured deflection, calculated after subtracting the thicknesses of the weld and plates. Variations in the results arise from differences in the applied welding parameters, while thickness differences are caused by the specific welding techniques used.

The sample dimensions.

| Sample | Length L [mm] | Join Length [mm] | Width [mm] | Thickness AL. [mm] | Thickness CF [mm] | Thickness [mm] | delta (deflection [mm]) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 110 | 27 | 25 | 1 | 1.8 | 2.8 | 2.2 |

| 2 | 110 | 27 | 25 | 1 | 1.8 | 2.8 | 2.3 |

| 3 | 110 | 27 | 25 | 1 | 1.8 | 3 | 2.9 |

| 4 | 110 | 27 | 25 | 1 | 1.8 | 3 | 4 |

| 5 | 110 | 27 | 25 | 1 | 1.8 | 3 | 4.4 |

| 6 | 110 | 27 | 25 | 1 | 1.8 | 3 | 2.2 |

| 7 | 110 | 27 | 25 | 1 | 1.8 | 3 | 3.6 |

| 8 | 110 | 27 | 25 | 1 | 1.8 | 3 | 3.7 |

Creating analytical models using the Finite Element Method (FEM) begins with a thorough understanding of the physical aspects of the phenomenon being studied. It is important to remember that, within the numerical “matrix” of the simulation, the model is always a simplification of the real world. Therefore, the engineer responsible for the calculations must remain fully aware of the limitations imposed by the numerical software, how best to simplify the model, and how to correctly interpret the results obtained. The analysis will always produce an output, but its accuracy depends on the assumptions and constraints defined at the outset.

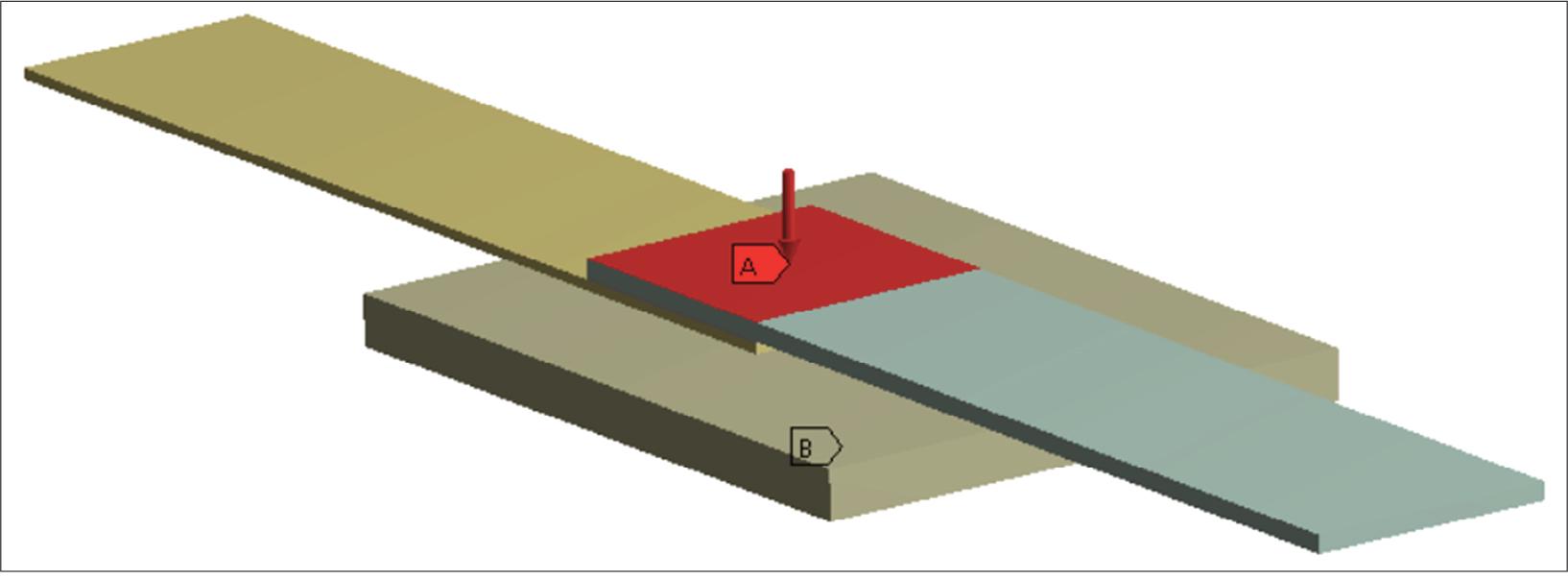

After meticulous preparation, the next step is to create the Computer-Aided Design (CAD) model of the welded sample (Figure 7). This model consists of four main components:

The aluminum plate

The CF/PA6 laminate plate

The PA6 film

The steel “station”.

CAD model of the welded sample.

In a Finite Element Method (FEM) model, Boundary Conditions (BCs) are essential for defining how the model interacts with its environment and for ensuring accurate simulation of real-world scenarios (Figure 8). In this case, the figure illustrates the placement of the applied pressure and temperature. The steel support is fixed at the bottom, while the plates are set in contact with a friction coefficient of 0.3. When the temperature reaches the melting point of Polyamide 6 (analysis time: 130–250 s), the contact condition is changed from frictional to bonded to simulate the welding process.

Pressure application in the model.

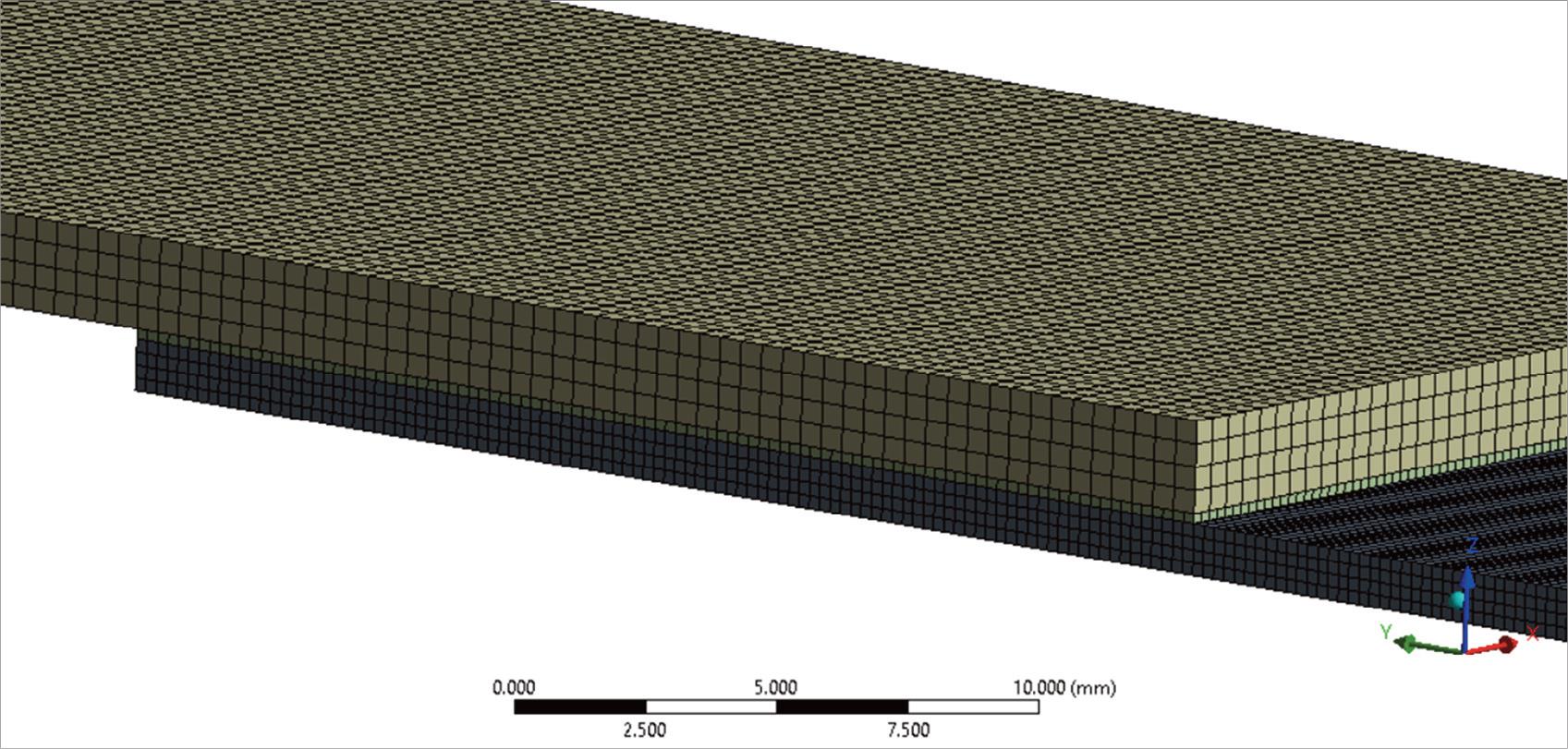

The station serves as a platform, replicating the real-life setup, against which the plates are pressed. The CAD model is then discretized into a mesh within the FEM software (Figure 9).

Closeup of the FEM mesh.

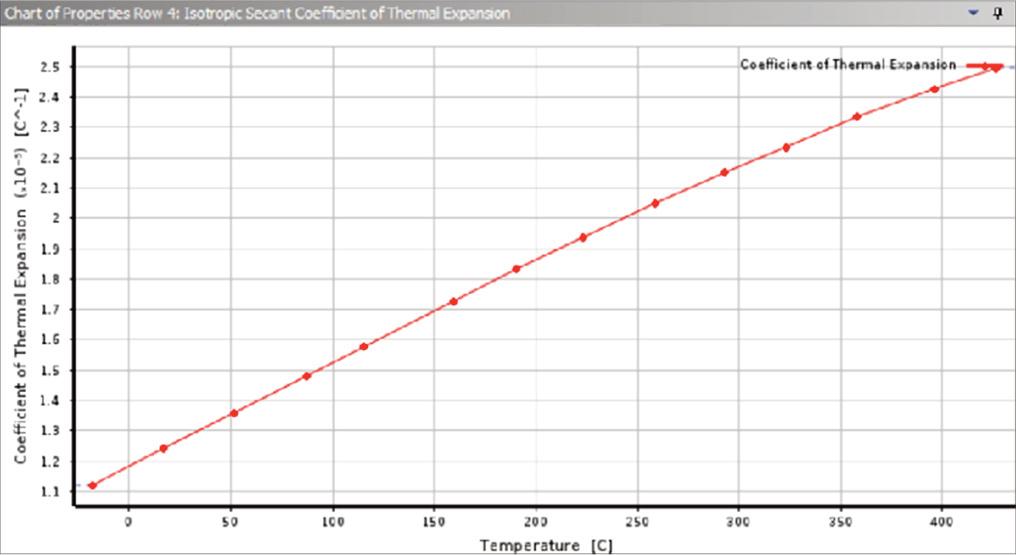

Accurate Finite Element Method (FEM) analysis requires detailed input of material properties, including yield strength, modulus of elasticity, and coefficients of thermal expansion. In more advanced models, additional factors may also be incorporated, such as anisotropic behavior, temperature-dependent properties, or even microstructural changes.

Figures 10 to 12 present graphs showing the effect of temperature on the properties of the materials involved in the welding process. When preparing the analysis, implementing highly accurate material cards based on these data provides the user with very precise results. This represents a rigorous and academic approach to FEM modeling but is also both time- and resource-intensive.

Isotropic secant coefficient of the thermal expansion of Aluminum 7075 (Rice et al., 2011).

Influence of temperature on the isotropic elasticity of Aluminum 7075 (Rice et al., 2011).

Stress–strain relationship of Polyamide 6 samples (Farina et al., 2019).

When time efficiency is a priority, a more pragmatic method can be used by applying only the worst-case material parameters – those corresponding to the highest temperatures. This practice, often referred to as “engineering conservatism,” simplifies the model while ensuring safety margins. Although this approach produces more conservative outcome values at each time step of the analysis, it significantly reduces the computational time required for the calculations.

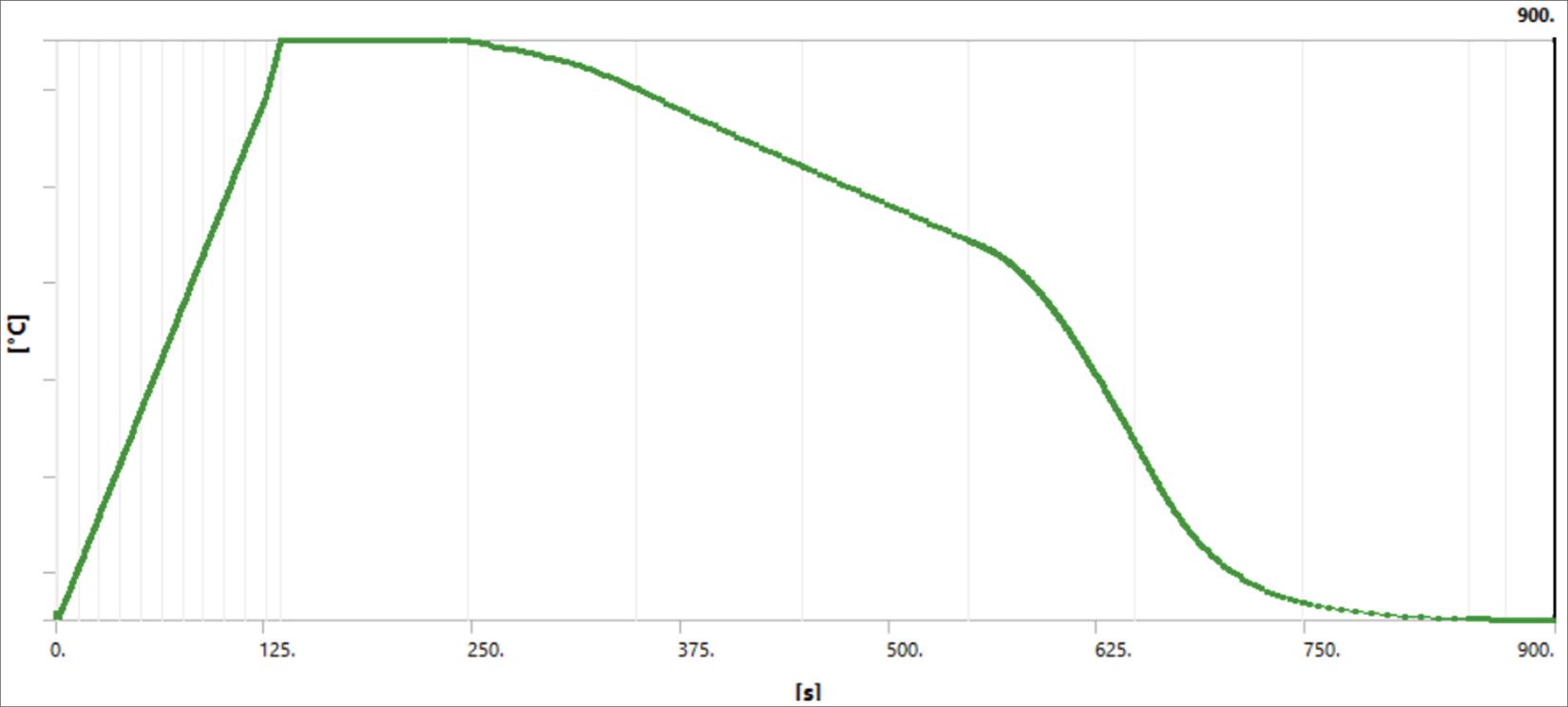

Thermal Analysis is the gateway to determining the residual stresses that arise from thermal gradients. This step simulates heat transfer within the material during processes such as welding or additive manufacturing. The model incorporates heat input data, boundary conditions, and material thermal properties, including thermal conductivity and specific heat capacity. The thermal analysis generates a temperature distribution map, which serves as the foundation for subsequent stress calculations. In this study, a transient thermal analysis was performed using multilinear material data. The temperature was applied to the aluminum plate and transferred to the laminate through contact interactions. The complete heating and cooling cycle is shown in Figure 13, closely replicating real-world conditions.

Thermal analysis, maximum temperature output.

The governing equation for heat conduction through a solid is expressed as:

Or

Where:

k∇T – Rate of heat conduction,

q – Rate of convection (W/m2),

k – Thermal conductivity (W/k · m),

t – Time,

T – Temperature (K),

ρ – Density of the material (kg/m3),

c – Specific heat of the material (J/kg · K).

The solution from the thermal analysis is transferred to the next stage, Mechanical Analysis, where material expansion is calculated based on the temperature distribution. At the peak temperature (Figure 13), the materials are fully expanded and the frictional contact changes to bonded contact. When the heat dissipates, the bonded elements contract, and the residual stresses arise. During the heating phase, the thermal strain εth is computed as:

αsec(T) is the secant coefficient of thermal expansion,

Tref is the zero-strain reference temperature,

T is the current nodal temperature.

Thermal stresses (σ) resulting from constrained thermal deformation are described by Hooke’s law under thermal strain:

σ is the resulting thermal stress (MPa),

E is the Young’s modulus of the material (MPa),

ε is the total strain, combining mechanical and thermal contributions (-),

αLΔT is the thermal strain induced by the temperature difference.

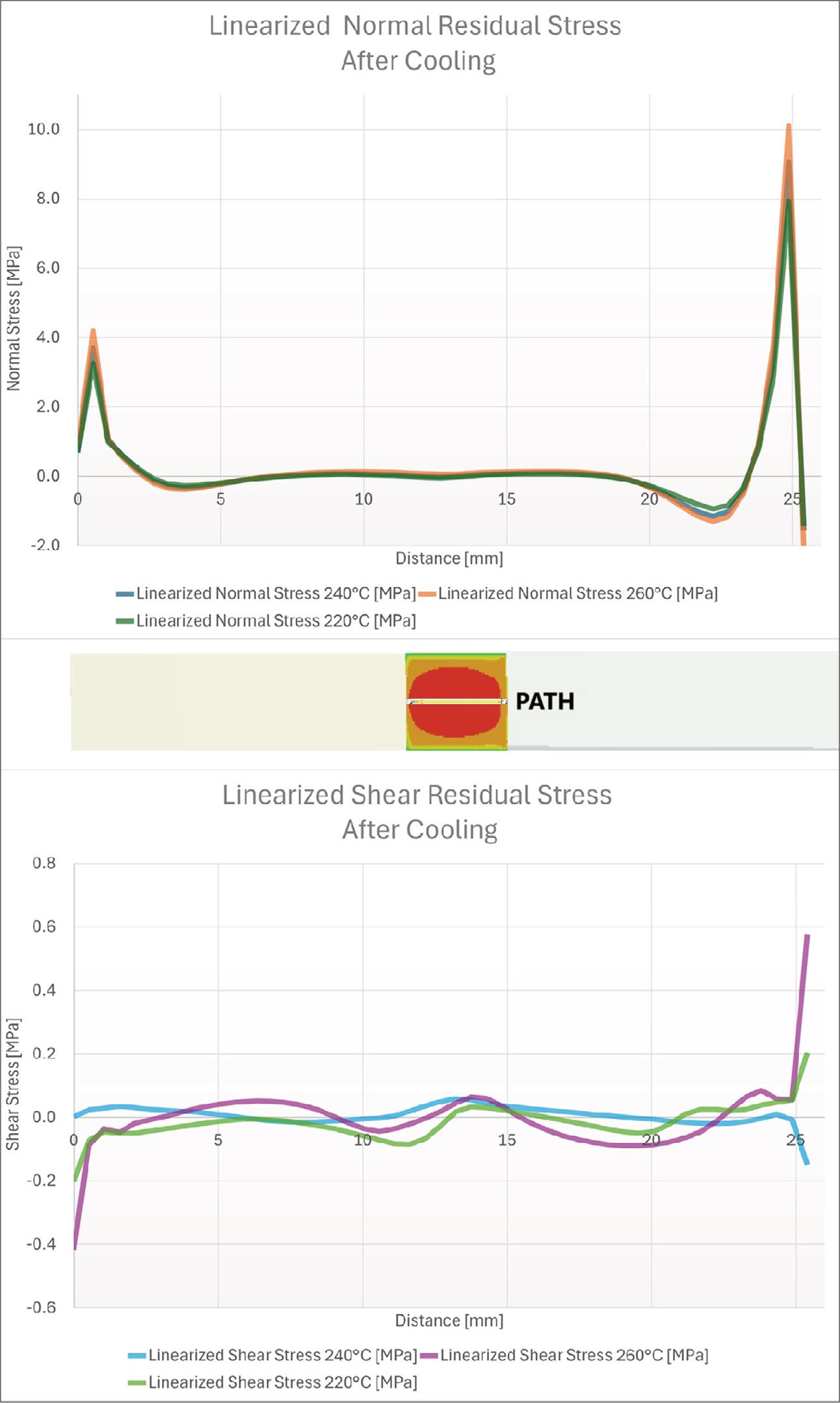

The stress results highly depend on the maximum temperature reached in the thermal analysis. Three cycles were considered (20°C→220°C→20°C, 20°C→240°C→20°C, 20°C→260°C→20°C). The middle cycle is shown as the reference and compared to the other cycles.

Stresses tangential to the plate surface or shearing the bond significantly impact the joint’s residual strength.

The following analysis examines the results on the aluminum face of the bond. The stresses on the aluminum side of the adhesion will help to predict the strength of the weld by providing information on how much the joint is weakened by the residual stresses occurring in its adhesion area.

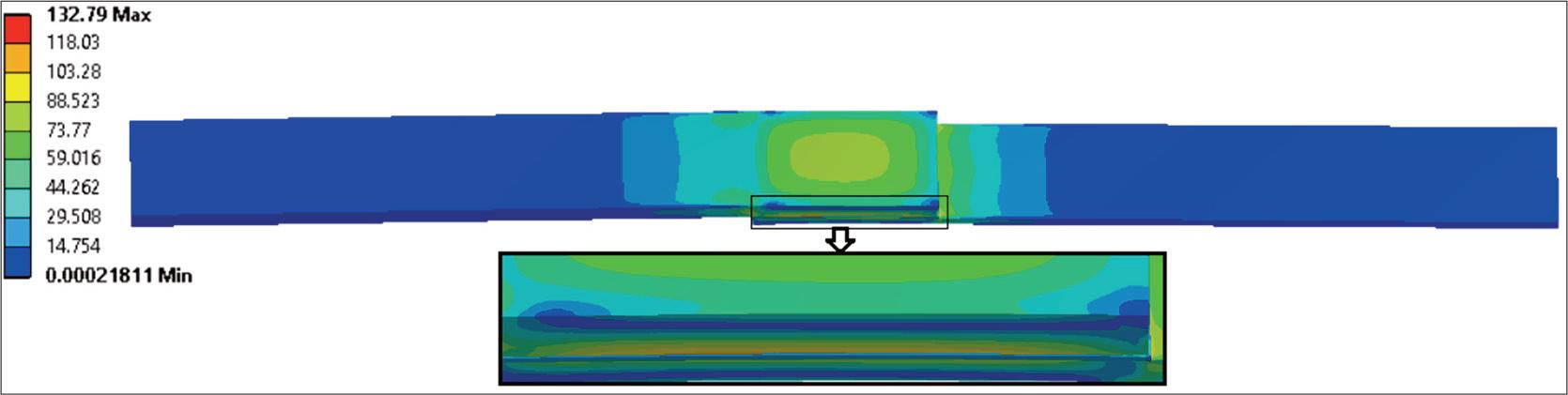

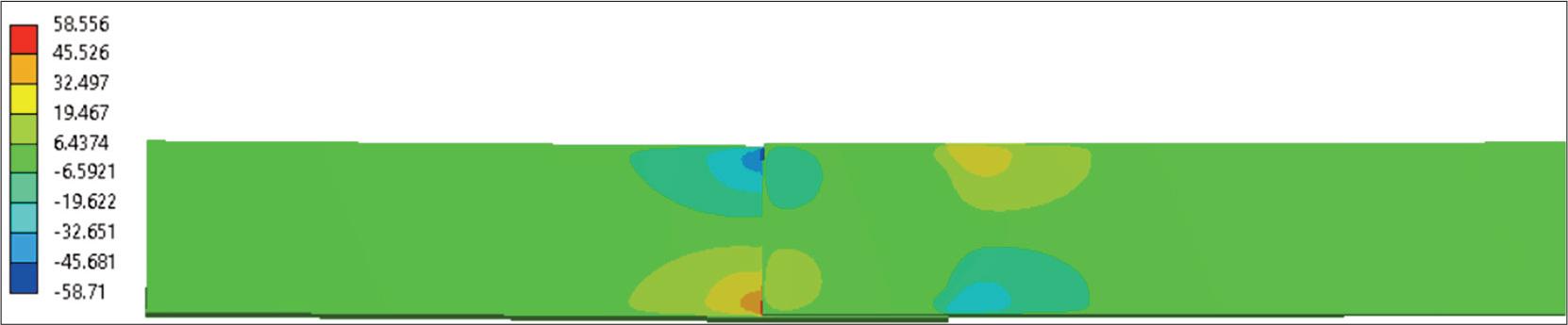

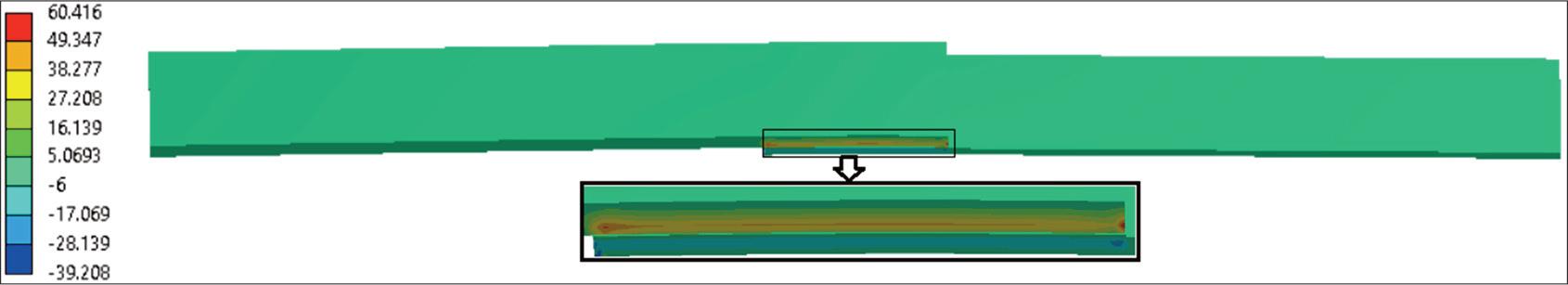

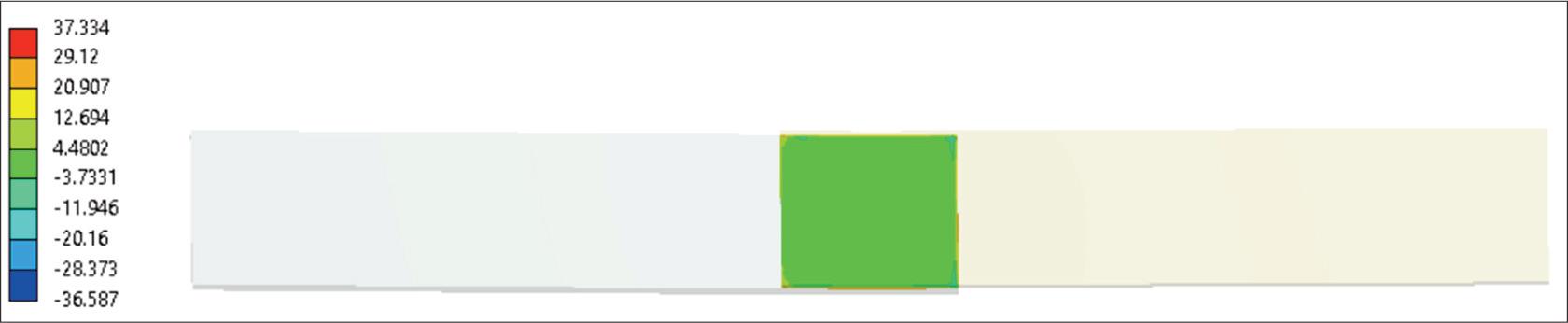

Residual stress stretches beyond the weld itself. Figures 14–15 illustrate the contours of these stresses, which gradually dissipate with increasing distance from the bonded area. This bonded region, by being constrained, is the source of the residual stress. Figures 16–17 highlight the face of the aluminum plate, showing the distribution of remaining shear and normal stresses. The legend indicates lower values than in the preceding illustrations, which is explained by the fact that stresses reach their highest levels at the far outer surfaces, while the stresses within the bonded area itself remain lower. Figure 18 provides deeper insight into stress development within a weld. Here, a path was defined along the aluminum face of the weld, and stresses were plotted. Following this path across the weld area, two peaks can be observed at the edges of the constrained zone. These appear in both normal and shear stresses; in the latter case, a reversal in direction is visible, indicated by a change in the sign of the stress value. The inner region of the weld carries relatively little stress, which suggests that the outer edges are the most vulnerable to debonding or delamination initiation. Lastly, sresses are shown to vary depending on the applied temperature gradient in the analysis. The results confirm the expected theorem: residual stresses increase as the thermal gradient rises. This outcome supports the correctness of both the applied boundary conditions and the overall analysis.

Residual Stress. Von Mises plot (20°C→240°C→20°C).

End of time, residual shear stress. Overall plot (20°C→240°C→20°C).

End of time, residual normal stress. Overall plot (20°C→240°C→20°C).

End of time, residual shear stress. Weld area plot, aluminum surface (20°C→240°C→20°C).

End of time, residual normal stress. Weld area plot aluminum surface (20°C→240°C→20°C).

Residual Stresses on the Weld Path.

The aim of this research was to develop a computational model capable of accurately predicting residual stresses in welded joints between thermoplastic composites and aluminum. The FEM model was constructed on the basis of welded samples, later cut for uniaxial testing, and the process was meticulously simulated as developed in the Thermoplastic Composites Department laboratory. Finally, the simulation results were compared with the physical samples.

The study focused on the interaction between carbon fiber–reinforced polycarbonate laminate and aluminum, with particular emphasis on the challenges arising from their differing coefficients of thermal expansion. These differences raised critical scientific questions concerning the magnitude of residual stresses within the joint, their impact on structural durability, and the need for an analytical model adaptable to other material combinations.

The results presented here are consistent with classical theoretical predictions provided by the Volkersen shear-lag model (Campilho, 2017), which describes shear stress distribution and concentration effects near the edges of bonded lap joints. In line with Volkersen’s theory, our FEM analysis revealed distinct peaks in both shear and normal stress components localized at the weld edges, underscoring the importance of targeted mitigation strategies in aerospace structural joints.

FEM Modelling: Detailed FEM simulations incorporated material-specific thermal and mechanical properties, allowing for accurate stress predictions. The study used three temperature cycles (20°C→220°C→20°C, 20°C→240°C→20°C, and 20°C→260°C→20°C) to examine the effect of peak temperatures on residual stresses.

Thermal Analysis: During the welding process, the heat generated caused the materials to expand at different rates due to their unique thermal expansion coefficients. This mismatch resulted in residual stresses after cooling, which were visualized using FEM models (Ahmad et al., 2019).

Residual Stresses: The study identified significant shear and normal stresses in the joints, primarily concentrated at the bond edges. These stresses were mapped and analyzed, showing how they dissipate with distance from the bonded area (Tabatabaeian et al., 2022b).

Residual stresses arise due to the mismatch in thermal expansion coefficients between aluminum and thermoplastic composites.

Stress peaks were observed at the bond edges, where bending and constraint effects are most pronounced, posing the highest risk for delamination or failure.

Average stresses within the weld are relatively low, but edge stress peaks remain inherently destructive.

Stress Superposition: Residual stresses are additive to externally applied stresses. This superposition results in elevated local stress levels during cyclic loading, even if the nominal external load is low (Pagliaro et al., 2011).

Crack Initiation Acceleration: Areas near the edges of the weld were identified as stress concentrators. FEM simulations in the study showed stress peaks at these zones, which are highly susceptible to crack initiation and debonding, particularly under cyclic thermal or mechanical loads (Teng & Chang, 2004b).

Delamination Risk: Residual shear stresses, particularly at the aluminum– composite interface, can drive interfacial delamination. Since thermoplastic–metal interfaces rely on mechanical interlocking and diffusion, residual shear stress can reduce bond integrity and accelerate fatigue damage (Tsivouraki et al., 2024).

Reduced Effective Strength: Even though average residual stresses across the bond might be moderate, localized peaks—especially at the outer edges—can significantly reduce the effective load-carrying capacity of the joint. This leads to earlier onset of fatigue failure compared to a stress-free joint (Houssam, n.d.).

Thermal Fatigue: In aerospace applications, parts are exposed to cyclic thermal gradients (e.g., sunlit vs. shadowed zones at high altitudes). These cycles add to the internal stress field, amplifying low-cycle fatigue mechanisms. If residual stress already exists, such cyclic thermal loading can trigger early failure.

The results presented in this study, together with the developed FEM model, will serve as the foundation for upcoming experimental investigations. Future work will include uniaxial tension tests and three-point bending tests to determine the residual strength of the welds. Additional research into the evolution of residual stresses within the weld will be carried out using tensometers. A key objective will be to evaluate the impact of residual stress on fatigue life. Residual stresses induced by thermal mismatch in aluminum–PA6 welded joints are expected to significantly reduce fatigue life, primarily by accelerating crack initiation and delamination at the weld edges. These effects are further magnified under the cyclic thermal and mechanical loading conditions typical of aerospace applications. Accurate prediction and effective mitigation of residual stresses through FEM analysis are therefore essential to ensure the long-term reliability of bonded repairs and hybrid aerospace structures.