In our study, we focus our attention on sustainable food purchasing behaviour. Consumers' food behaviour consists of the food product journeys: planning, purchasing, storaging, preparation, and consumption of food. Food waste is an outcome of the way households deal with these different stages (S. Li et al., 2022; Stancu & Lähteenmäki, 2022). The aim of the study is to measure sustainable food purchasing behaviour among consumers aged 55+, identify its determinants and develop recommendations to support sustainable food consumption among silver consumers.

We analyse three types of sustainable food purchasing behaviour distinguished on the basis of the literature review: purchasing organic and healthy food (Vittersø & Tangeland, 2015), purchasing food in the right quantity to minimise food waste (Grizzetti et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2021), and packing purchased food in consumers' own reusable bags or containers that reduce packaging waste (Nemat et al., 2020; White & Lockyer, 2020). This integrated approach to analysing sustainable food consumption allows for a comprehensive coverage and is new to the literature.

Researchers point out that there is still little known about factors that may explain food shopping and consumption behaviour and practices (Janssens et al., 2019). Existing studies focus primarily on the determinants of organic food purchases (Avşar, 2024; Teixeira et al., 2021; Zagata, 2012). Our paper also makes a contribution to knowledge about predictors of green, healthy food purchasing and we also try to identify the predictors (personal and contextual) for the other two types of food purchasing behaviour: buying food in appropriate quantities and packing food in consumers' own reusable packaging.

To achieve the above goal, we will seek answers to the following research questions:

- (1)

What kinds of consumer behaviours shape a sustainable approach to food consumption?

- (2)

What are sustainable food purchasing behaviours among consumers aged 55+?

- (3)

What are the behavioural and contextual determinants of sustainable food purchasing behaviour among consumers aged 55+?

- (4)

What sociodemographic factors determine interest in sustainable food purchasing behaviour among consumers 55+?

In our research, we adopt the age limit of 55+ for older consumers, in line with the analysis results of Zheng et al. (2024). They present the following justifications commonly used by other researchers: most older individuals accept this age limit; prior studies use similar definitions; reviews support this age threshold; it aligns with census age categories; people aged 55 and above share similar values; it facilitates comparisons between “young-old” and “old-old”; research on retired persons often starts at this age; and it helps in studying active older individuals. Additionally, in Poland, individuals performing work under special conditions (e.g., determined by natural forces such as underground or underwater work) or of a special nature (requiring exceptional responsibility and specific psychophysical fitness) are entitled to the so-called “bridge pension” (Ustawa z Dnia 19 Grudnia 2008 r. o Emeryturach Pomostowych, 2008). The age required to qualify for this benefit is 55 for women and 60 for men.

The focus on consumers 55+ stems from several premises. Firstly, the studies of consumer behaviour throughout the lifespan are becoming increasingly popular as the number of consumers aged 55+ steadily increases (Carpenter & Yoon, 2015; Venn et al., 2017). Few studies to date have focused on responsible and sustainable consumption among mature adults (Grasso et al., 2019; Zbuchea et al., 2021) or responsible consumption in a broader – generational – context (Bulut et al., 2017; Diprose et al., 2019; Gordon-Wilson & Modi, 2015; Morrison & Beer, 2017). However, research among older consumers focuses on determinants other than psychological ones. They indicate that important sociodemographic factors determining interest in sustainable food consumption include gender, age, education, product prices and consumer income (Niva et al., 2014; Schäufele & Hamm, 2017).

In Poland the age group of consumers aged 55+ is growing due to the rapid rate of population ageing and increasing life expectancy (Podgórniak-Krzykacz, Przywojska, & Warwas, 2020; Podgórniak-Krzykacz, Przywojska, & Wiktorowicz, 2020). This means that the elderly represent a significant consumer segment. Silver consumers' demand potential in Poland is also evidenced by data on their income. The average monthly disposable income in retirees' households is slightly higher than that of workers' and farmers' households, and only slightly lower than that of self-employed households. Moreover, the share of average monthly per capita spending on food and non-alcoholic beverages in the total spending of retirees' households in 2021 was as high as 28.5% (Główny Urząd Statystyczny, 2021). This means that the silver consumer segment in Poland is not only numerous, but quite affluent and very active in food consumption. In addition, older adults in Poland show a fairly high environmental awareness (Ministerstwo Klimatu i Środowiska, 2020; Włodarczyk, 2019). Thirdly, this age group of consumers exhibits an increased risk of falling ill and deteriorating health (Szukalski, 2021), which should favour the consumption of organic, healthy food products (Grochowicz et al., 2021). As a result, improving the quality of life through health and the prevention of many diseases has become a challenge for public policy and the food industry. Finally, the challenge of demographic transition is currently affecting many countries in the EU, Asia and North America (J. Li et al., 2019). Understanding and anticipating this transition is vital as the world seeks to chart a path to sustainable development. Countries with ageing populations should adjust their public programs to accommodate the growing number of older people. Under these conditions, the results of our research conducted in Poland along with our recommendations may prove helpful in formulating public policies in other countries as well. Furthermore, the sustainable purchasing behaviour of silver consumers is rarely investigated, thus our paper fills a knowledge gap in this area.

Based on the literature review, we assume that sustainable grocery shopping behaviour consists of three types of consumer behaviour: shopping for organic and healthy food, shopping for food in appropriate quantities to minimise food waste, and packing purchased food in consumers' own bags. This is a novel approach, the validity of which we will test through a study conducted among consumers aged 55+.

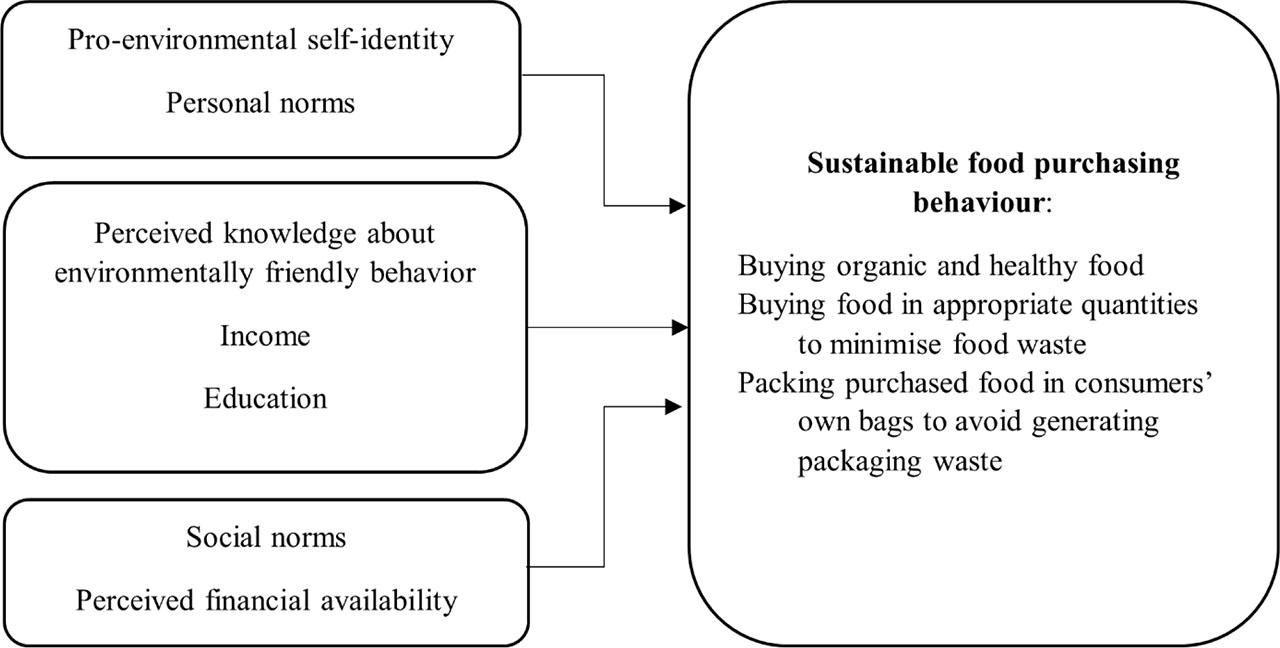

Our research framework (Figure 1) takes into account the following determinants of sustainable food purchasing behaviour attributed to 3 groups of factors selected on the basis of the literature review section:

- (1)

Personal value: pro-environmental self-identity (Stets & Biga, 2003) and personal norms (Thøgersen & Ölander, 2006).

- (5)

Individual capacity: perceived knowledge about environmentally friendly behaviour (Peattie, 2010), income (Gracia & De Magistris, 2007; Rimal et al., 2005), and education (O'Donovan & Mccarthy, 2002).

- (6)

External conditions: social norms (Biel & Thøgersen, 2007; Salazar et al., 2013) and perceived financial availability of environmentally friendly products (Botonaki et al., 2006; Gleim et al., 2013; Hughner et al., 2007; Vermeir & Verbeke, 2006).

Research framework for sustainable food purchasing behaviour

Due to the empirically proven importance of gender and age factors for sustainable consumption behaviour of older persons (Azzurra et al., 2019; Griffin & Sobal, 2013; Grubor & Djokic, 2016), we include these control variables in our study.

A scale to measure sustainable food purchasing behaviour (SFPB) was developed by the authors and initially included 17 variables measured on a 4-point Likert scale (4 variables describing purchasing organic food and 3 variables describing purchasing food in appropriate quantities to reduce waste were measured using a scale: 1 - definitely not, 2 - rather not, 3 - rather yes, 4 - definitely yes; 10 variables describing packing purchased food in consumers' own packaging to avoid generating packaging waste were measured using a scale of 1 - never, 2 - sometimes, 3 - often, 4 - always).

To measure the constructs: pro-environmental self-identity (PESI), personal norms (PN) and social norms (SN), perceived knowledge of environmentally friendly behaviour (PK) and perceived financial availability of organic food (PFA), existing scales were used, which were modified and adapted for the purposes of the study. The items that were used to measure the constructs are shown in Table 1.

Constructs, items, and references

| Construct | Items | Scale | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pro-environmental self-identity (PESI) |

| scale of 1 to 5, where: 1 - definitely not, 2 - not, 3 - partially 4 - yes, 5 - definitely yes | (Whitmarsh & O'Neill, 2010) |

| Personal norms (PN) |

| scale of 1 to 5, where: 1 - definitely not, 2 - not, 3 - partially 4 - yes, 5 - definitely yes | (Park & Ha, 2012) |

| Social norms (SN) |

| scale of 1 to 5, where: 1 - definitely not, 2 - not, 3 - partially 4 - yes, 5 - definitely yes | (Park & Ha, 2012) (Rausch & Kopplin, 2021) |

| Perceived knowledge of environmentally friendly behaviour (PK) | I know how to reduce the negative environmental consequences of my behaviour | scale of 1 to 5, where: 1 - definitely not, 2 - not, 3 - partially 4 - yes, 5 - definitely yes | (Whitmarsh & O'Neill, 2010) (Rausch & Kopplin, 2021) |

| Perceived financial availability of organic food (PFA) | - In my opinion, organic food is more expensive than other products | scale of 1 to 4, where: 1 - definitely not, 2 - rather not, 3 - rather yes, 4 - definitely yes | (Rausch & Kopplin, 2021) |

Education was measured on the following scales: primary, basic vocational, secondary, higher bachelor/engineer, higher master's degree. Income was measured on a scale of 2000 PLN (515.5 $) or lower, 2001–3000 PLN (515.7$ – 773.2$), 3001–4000 PLN (773.4$ – 1030.9$), over 4000 PLN (1030.9$). The following demographic control variables were measured: gender (female, male), age on a scale of 55–59, 60–64, 65–74, 75–84, 85+.

In order to test the research assumptions, we conducted our own study among 401 people over the age of 55 in Poland using the CATI technique. The research sample was selected proportionally from the population living in Poland aged 55+, taking into consideration the gender and age, as well as the voivodeship where they live and the respondents' place of residence (i.e., the city or the village). The total population from which the research sample was selected consists of 24.2 million people (as of 31.12.2019). The optimal sample size was calculated as n = 384 people. Such a number for the study group allows us to generalise the results of the study to the entire population with parameters customarily accepted in social research, that is, a 95 percent confidence level with a margin of error of +5 percent. In the end, the size of the research sample, as mentioned before, was 401 people. The structure of the examined sample is as follows (Table 2). Given the random selection of the sample, its size n = 401 enables us to generalise the results at an error rate of 4.89 percent. The data were analysed anonymously, therefore, the authors did not have access to personal identifying information. The ethics approval for survey studies is not required.

Sample structure

| Variable | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Men | 171 | 42.6 |

| Women | 230 | 57.4 | |

| Age | 55–59 | 88 | 21.9 |

| 60–64 | 82 | 20.4 | |

| 65–74 | 144 | 35.9 | |

| 75–84 | 61 | 15.2 | |

| 85+ | 26 | 6.5 | |

| Education | Primary | 25 | 6.2 |

| Basic vocational | 82 | 20.4 | |

| Secondary | 214 | 53.4 | |

| Higher Bachelor/engineer | 27 | 6.7 | |

| Higher master's degree | 53 | 13.2 | |

| Income | 2000 PLN or lower | 246 | 61.3 |

| 2001–3000 PLN | 115 | 28.7 | |

| 3001–4000 PLN | 32 | 8.0 | |

| over 4000 PLN | 8 | 2.0 |

The following analytical methods were used in the study: the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) to validate the measurement of latent variables; reliability of measurement of all constructs; correlation and regression analyses, to examine the presence of relationships between food purchasing behaviour and its predictors.

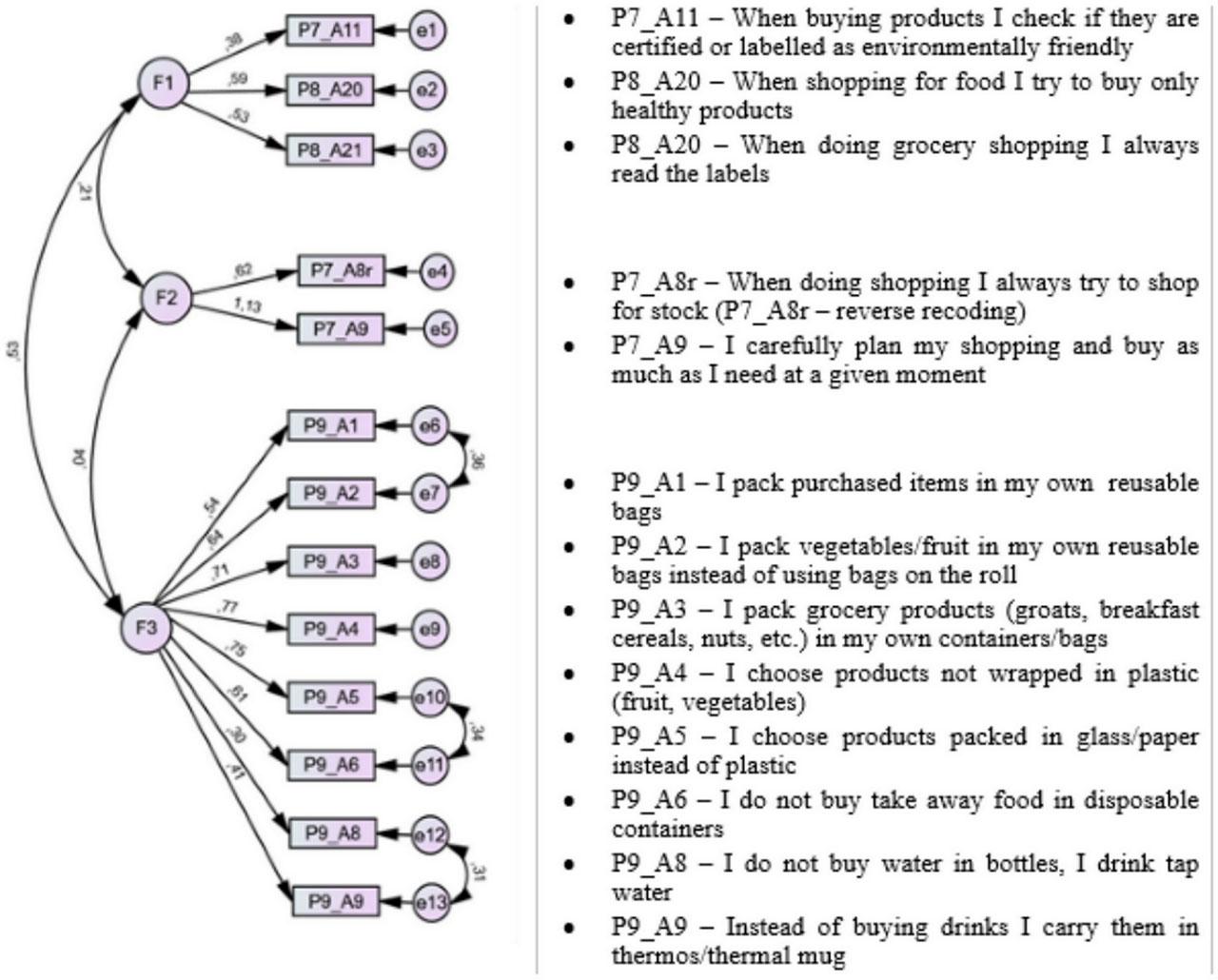

In line with the theoretical assumptions, the measurement tool for sustainable purchasing behaviour of people aged 55 and over includes three sub-dimensions:

F1 – buying organic and healthy food,

F2 – buying appropriate quantities of food to reduce food waste

F3 – packing purchased food in customers' own bags to avoid generating packaging waste.

The CFA confirms the validity of extracting the above-mentioned three sub-dimensions. Factor structure of the model together with the values of standardised coefficients are presented in Figure 2.

Factor structure of measurement model for sustainable food purchasing behaviour of people aged 55+

The average level of the sustainable food purchasing behaviour (SFPB) of people aged 55+ is quite high: around 2.36, with a scale ranging from 1 to 4 (Table 3). At the same time, the results are quite homogeneous (SD = 0.37, i.e., 16 percent of the mean). Also, for the subscales of the sustainable food purchasing decisions scale, the results are quite poorly differentiated (the standard deviation represents 20–29 percent of the mean). Half of the individuals score not lower than 2.38 on the SFFB scale, not lower than 2.00 on the F1 subscale (buying organic and healthy food), not lower than 2.50 on the F2 subscale (buying appropriate quantities of food to reduce food waste), and not lower than 2.38 on the F3 subscale (packing purchased food in customers' own bags to avoid generating packaging waste), the F1 subscale performs less well compared to scores in other areas, and the F2 subscale performs best. This means that mature Poles exhibit sustainable food shopping behaviour patterns. In particular, they are doing their best to buy food in appropriate quantities to reduce food waste. In contrast, they attach far less importance to buying organic food.

Descriptive statistics – sustainable food purchasing behaviour and its determinants

| Statistics | F1 | F2 | F3 | SFPB | PN | SN | PK | PESI | PFA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.13 | 1.38 | 10.00 | 6.00 | 3.00 | 6.00 | 1.00 |

| Max | 3.67 | 4.00 | 3.88 | 3.69 | 12.00 | 8.00 | 4.00 | 8.00 | 4.00 |

| M | 2.14 | 2.45 | 2.42 | 2.36 | 11.49 | 7.43 | 3.82 | 7.48 | 2.95 |

| Me | 2.00 | 2.50 | 2.38 | 2.38 | 12.00 | 8.00 | 4.00 | 8.00 | 3.00 |

| SD | 0.48 | 0.70 | 0.47 | 0.37 | 1.92 | 1.35 | 0.68 | 1.21 | 0.75 |

| S | −0.31 | 0.09 | 0.09 | −0.01 | −0.04 | −0.05 | −0.09 | −0.03 | −0.42 |

| K | 0.39 | −0.36 | −0.35 | 0.13 | −0.30 | −0.38 | −0.24 | −0.02 | −0.02 |

Notes: F1 - buying organic and healthy food, F2 - buying appropriate quantities of food to reduce food waste, F3 - packing purchased food in customers' own bags to avoid generating packaging waste, SFPB - sustainable food purchasing behaviour, PN - personal norms, SN - social norms, PK - perceived knowledge of environmentally friendly behaviour, PESI - pro-environmental self-identity, PFA - perceived financial availability of organic food, min – minimum, max – maximum, M – mean, Me – median, SD – standard deviation, S – skewness, K – kurtosis

Variables measuring the individual potential determinants of sustainable food purchasing behaviour are also characterised by a low degree of variability (Table 3). In line with the assumptions (Table 1), the personal norms construct (PN) was measured with three variables. It assumes values from 7 to 12, for which the Cronbach's alpha was 0.897. The pro-environmental self-identity (PESI) was measured by two variables and it takes values from 6 to 8 (Cronbach's alpha of 0.857). The social norms (SN) were measured using two variables and this factor assumes values from 6 to 8; the Cronbach's alpha was 0.868. The remaining constructs – perceived knowledge of environmentally friendly behaviour (PK) and perceived financial availability of organic food (PFA) – formed one variable each. Given that the maximum for PN is 12, for PESI and SN is 8, and for PK is 4, the median approaching these values confirms their high levels for Poles aged 55+. Only slightly lower results were obtained for PFA, where the max is 4 and Me = 3. More than half of the respondents perceive the prices of organic food as rather high, and 22 percent as definitely high.

According to the research framework (Figure 1), sustainable food purchasing behaviour relates to 5 constructs: pro-environmental self-identity (PESI), personal norms (PN), perceived knowledge of environmentally friendly behaviour (PK), social norms (SN), and perceived financial availability of organic food (PFA). In assessing these relationships, let us start with the correlation coefficients (Table 4). Only one of the variables – perceived financial availability of organic food – is not correlated with both the sustainable food purchasing behaviour total score and the sub-scores F1 (buying organic and healthy food) and F2 (buying appropriate quantities of food to reduce food waste). The other factors – personal norms and social norms, perceived knowledge of environmentally friendly behaviour, and pro-environmental self-identity – are significantly positively correlated with the overall SFPB score, as well as with two of its three dimensions: F1 (buying organic and healthy food) and F3 (packaging purchased food in customers' own packaging to avoid generating packaging waste). Correlation coefficients range between 0.3 and 0.4, suggesting a moderately strong relationship between the variables. Food purchasing behaviour is, in these two areas and in general, more balanced for those individuals with (on average) higher personal and social norms, environmental awareness and knowledge, while no such relationship exists for the perception of organic food prices (p > 0.05). None of the factors analysed are significantly related to the F2 area (buying food in appropriate quantities to reduce food waste).

Pearson's correlation between sustainable food purchasing behaviour and its determinants

| PN | SN | PK | PESI | PFA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | R | 0.323 | 0.340 | 0.283 | 0.303 | −0.002 |

| p | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | 0.964 | |

| F2 | R | 0,093 | 0,026 | 0,013 | 0,081 | 0.050 |

| p | 0,062 | 0,601 | 0,794 | 0,107 | 0.315 | |

| F3 | R | 0.300 | 0.305 | 0.265 | 0.283 | 0.056 |

| p | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | 0.262 | |

| SFPB | R | 0.360 | 0.349 | 0.297 | 0.336 | 0.058 |

| p | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | <0.001** | 0.247 |

Notes: F1 - buying organic and healthy food, F2 - buying appropriate quantities of food to reduce food waste, F3 - packing purchased food in customers' own bags to avoid generating packaging waste, SFPB - sustainable food purchasing behaviour, PN - personal norms, SN - social norms, PK - perceived knowledge of environmentally friendly behaviour, PESI - pro-environmental self-identity, PFA - perceived financial availability of organic food

Significance level: ** p < 0.01

The level of education does not significantly differentiate the assessment of sustainable food purchasing behaviour – both in general (SFPB) and its individual sub-dimensions (subscales). Income does, however, play a significant role (Table 5), albeit only for the F2 scale (buying appropriate quantities of food to reduce food waste). Those with the lowest incomes (2000 PLN (515.5 $) or lower) scored significantly lower than those whose income ranges between 2001 and 3000 PLN (515.7$ – 773.2$).

Sustainable food purchasing behaviour by income (PLN)

| Scale | 2000 or lower | 2001–3000 | 3001–4000 | over 4000 | F(df) | p | Commentsa | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| F1 | 2.10 | 0.51 | 2.21 | 0.44 | 2.14 | 0.44 | 2.29 | 0.21 | F(3; 150) = 2.621 | 0.053b | X |

| F2 | 2.38 | 0.68 | 2.61 | 0.72 | 2.55 | 0.72 | 2.06 | 0.56 | F(3; 397) = 3.957 | 0.008** | 2000 or lower < 2001–3000 (p = 0.034) |

| F3 | 2.43 | 0.49 | 2.43 | 0.45 | 2.36 | 0.48 | 2.19 | 0.38 | F(3; 397) = 0.890 | 0.446 | X |

| SFPB | 2.35 | 0.38 | 2.41 | 0.34 | 2.34 | 0.38 | 2.19 | 0.29 | F(3; 397) = 1.275 | 0.282 | X |

Notes: F1 – buying organic and healthy food, F2 – buying appropriate quantities of food to reduce food waste, F3 – packing purchased food in customers' own bags to avoid generating packaging waste, SFPB – sustainable food purchasing behaviour

results of post-hoc test (Sidak test),

probability in the Brown-Forsythe test

Significance level: ** p < 0.01

Considering the control variables, we note that age does not significantly differentiate the assessment of sustainable food purchasing behaviour. Gender, on the other hand, is relevant (Table 6) – in the overall assessment of the phenomenon under study, as well as for sub-scales F1 (buying organic and healthy food) and F3 (packaging purchased food in customers' own packaging to avoid generating packaging waste), women score significantly higher than men.

Sustainable food purchasing behaviour by gender

| Scale | Men | Women | F(df) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |||

| F1 | 2.05 | 0.43 | 2.21 | 0.51 | F(1; 393.2) = 12.094a | 0.001** |

| F2 | 2.41 | 0.69 | 2.48 | 0.70 | F(1; 399) = 1.234 | 0.267 |

| F3 | 2.33 | 0.47 | 2.49 | 0.47 | F(1; 399) = 10.602 | 0.001** |

| SFPB | 2.28 | 0.34 | 2.42 | 0.38 | F(1; 399) = 15.361 | <0.001** |

Note: F1 – buying organic and healthy food, F2 – buying appropriate quantities of food to reduce food waste, F3 – packing purchased food in customers' own bags to avoid generating packaging waste, SFPB – sustainable food purchasing behaviour

probability in the Brown-Forsythe test

Significance level: ** p < 0.01

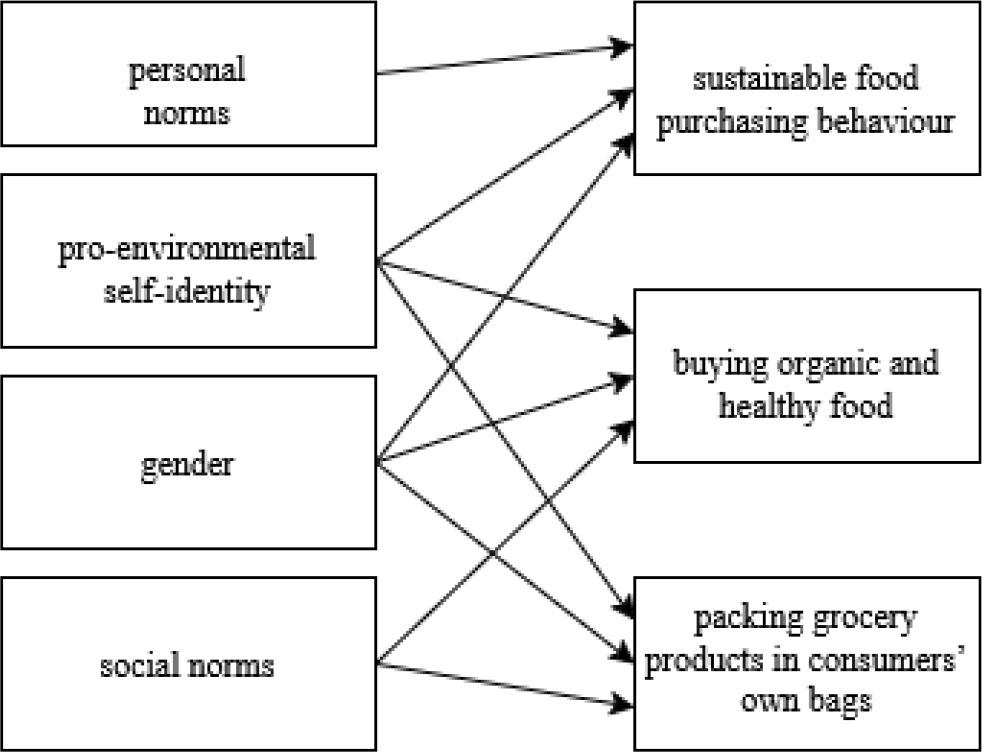

Taking into account as explanatory variables all the discussed factors together, as well as the control variables, linear regression models were constructed in which the individual indicators of sustainable food purchasing behaviour were taken – separately – as dependent variables (Table 7). The models were estimated using stepwise regression, thus the models already only include significant (at α = 0.05) factors (variables for which at subsequent steps p > 0.05 were not included in the models). The overall assessment of sustainable food purchasing behaviour remains, ceteris paribus, in a statistically significant relationship with three factors: personal norms, pro-environmental self-identity, and gender. Setting the other factors constant, higher personal norms score is associated with more sustainable food purchasing behaviour, which is also facilitated by higher pro-environmental self-identity. Gender also plays an important role: ceteris paribus, more sustainable food purchasing behaviour is related to women. Comparing the importance of these factors, personal norms play the greatest role in this respect (Beta = 0.222); slightly weaker is environmental awareness (Beta = 0.173).

Determinants of sustainable food purchasing behaviour of people aged 55+ – linear regression results

| B | Beta | t | p | VIF | ANOVA | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable: SFPB (model 1) | |||||||

| Const | 1.411 | 12.287 | <0.001** | F(3; 397) = 26.11 | 0.165 | ||

| PN | 0.043 | 0.222 | 3.581 | <0.001** | 1.828 | ||

| PESI | 0.053 | 0.173 | 2.810 | 0.005** | 1.804 | ||

| Gender | 0.104 | 0.139 | 2.986 | 0.003** | 1.026 | ||

| Dependent variable: F1 (model 2) | |||||||

| Const | 1.014 | 5.944 | <0.001** | F(4; 397) = 22.29 | 0.144 | ||

| SN | 0.084 | 0.232 | 3.947 | <0.001** | 1.614 | ||

| PESI | 0.058 | 0.148 | 2.522 | 0.012** | 1.603 | ||

| Gender | 0.117 | 0.108 | 2.281 | 0.023** | 1.038 | ||

| Dependent variable: F3 (model 3) | |||||||

| Const | 1.407 | 9.542 | <0.001** | F(1; 397) = 18.29 | 0.121 | ||

| SN | 0.069 | 0.198 | 3.306 | 0.001** | 1.613 | ||

| PESI | 0.113 | 0.149 | 2.503 | 0.013** | 1.603 | ||

| Gender | 0.058 | 0.118 | 2.494 | 0.013** | 1.019 | ||

Notes: F1 – buying organic and healthy food, F3 – packing purchased food in customers' own bags to avoid generating packaging waste, SFPB – sustainable food purchasing behaviour, PN – personal norms, SN – social norms, PESI – pro-environmental self-identity

B – regression coefficient, Beta – standardized regression coefficient, t – t-statistics, VIF – variance inflation factor, ANOVA – significance test for coefficient of determination, R2 – coefficient of determination

On the other hand, in the area: buying organic and healthy food (F1), social norms and also pro-environmental self-identity play an important role, ceteris paribus – the higher they are, the higher is the attitude towards buying organic food. Gender also plays a role: significantly higher scores are recorded for women than for men. Analogous findings apply to area F3 – packing purchased food in own packaging to avoid generating packaging waste. In both areas, ceteris paribus, social norms play the greatest role (+), followed by pro-environmental self-identity (+). The obtained models have satisfactory statistical properties; the coefficient of determination is significantly different from 0 (in ANOVA p < 0.001), the explanatory variables do not show collinearity (VIF < 10), in addition, the assumptions regarding the random component can be considered fulfilled. Nevertheless, the values of the coefficient of determination from the sample are not very high (personal and social norms, pro-environmental self-identity, and gender explain 12–17 percent of the variation). This means that, in addition to the factors indicated, it is worth including, in further studies, other variables (e.g., previous food purchasing behaviour, willingness to pay for organic products, concern for healthy eating, dietary habits, general propensity to save) that could potentially shape sustainable food purchasing behaviour. For F2 – buying food in the right quantities to reduce food waste – none of the explanatory variables analysed (including control variables) proved, ceteris paribus, to be significantly associated with it. Figure 3 presents the predictors of sustainable food purchasing behaviour of people aged 55+, identified through regression analysis.

Predictors of sustainable food purchasing behaviour of people aged 55+

Our research indicates that the food purchasing behaviour of older people in Poland is sustainable. Such a result confirms the previous few findings from studies on existence of segments of older consumers who demonstrate ecologically conscious consumer behaviour (Sudbury Riley et al., 2012) and from studies on the consumption strategies of Polish older people (Bylok, 2013; Zalega, 2018).

In our study the sustainable food purchasing behaviours manifest in the strongest way in buying food in appropriate quantities to reduce food waste and are the weakest for buying organic and healthy food. Purchasing food in sufficient quantities to reduce food waste can be justified by the savings-oriented attitude of older consumers. Research results indicate that mature people in Poland try to live frugally, as this is the attitude they have been taught at earlier stages of their lives (Przywojska et al., 2022; Zalega, 2018). In the years preceding the political changes of 1989 there were widely shared practices of “thrift” and self-reliance at the individual household level in many spheres of everyday life in Central and Eastern European countries (including key sectors relating to environmental sustainability such as energy, water, food, clothes and transport) (Smith & Jehlička, 2007). Włodarczyk (2019), on the other hand, argued that the environmental behaviour of Polish older persons is largely motivated by economic reasons rather than clear concern for the environment. Rejman et al. (2019) also emphasise that the need to limit food waste in households is seen from the perspective of own/individual budget rather than an ecological perspective. The results of our study do not confirm such a relationship.

In our research, packing food in the buyer's own packaging to minimise packaging waste was ranked as the second most commonly undertaken purchasing behaviour. We suppose that this shopping practice is grounded in the previous food shopping experiences of older people. The lack of access to packaging such as plastic bags, or the prevalence of reusable packaging such as glass or paper before 1989 in Poland, had resulted in the common use of consumers' own bags and participation in the circulation system of reusable packaging in the economy. Again, therefore, what may now be perceived in Western European environmental discourses as a sustainable pattern of consumption rarely was ecologically motivated in Poland, in the sense in which ecological motivation is understood in Western Europe. Instead, it was largely the result of the public policies of state-socialist governments (Smith & Jehlička, 2007).

The behaviour of seniors packing groceries in their own bags is also encouraged by the requirement to pay a fee for plastic shopping bags. In Poland, a recycling fee for single-use plastic bags was introduced in 2018 through an amendment to the Packaging and Packaging Waste Management Act (Ustawa z Dnia 13 Czerwca 2013 r. o Gospodarce Opakowaniami i Odpadami Opakowaniowymi Dz.U. 2013 Poz. 888, 2013). The Act implements Directive (EU) 2015/720 of the European Parliament and the Council dated 29.4.2015 (Directive [EU] 2015/720 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2015 Amending Directive 94/62/EC as Regards Reducing the Consumption of Lightweight Plastic Carrier Bags [Text with EEA Relevance], 2015). According to estimates by the Ministry of Climate and Environment, prior to the implementation of the Act, the average annual consumption of plastic shopping bags (across all thicknesses) per capita in Poland was approximately 300 bags. As a result of the Act, this number has decreased to around 9 lightweight bags and approximately 16 other bags (Portal Samorządowy, 2023).

The behaviour related to the purchase of organic and healthy food ranks lowest among the three analysed purchasing behaviours. This can be explained by the lower innovativeness of older consumers (Tellis et al., 2009), which according to researchers affects the intention to adopt pro-environmental behaviours (Alzubaidi et al., 2021), including the intention to purchase organic food (L. Li et al., 2021). Also the influence of past behaviour on future intentions and behaviour is confirmed by the work of other researchers (Rønnow et al., 2024). For example, Golob et al. (2018) note that past consumption of organic food is important for future purchase intentions, as well as for personal norms and attitudes towards buying organic food. In the case of Polish older persons, their lack of experience in purchasing organic products in the past (caused by the lack of availability of such products under the conditions of a centrally planned economy and during the political transformation of the country) may lead to less interest in such products at the present stage of life. Some other reasons for low interest in organic products are also indicated: higher prices, lack of trust, and lack of knowledge (Taghikhah et al., 2020). Other studies reveal further barriers to sustainable food choices, related to the above, which are food purchasing habits (Rejman et al., 2019) and food preferences (Dinnella et al., 2016).

Predictors of sustainable food purchasing behaviour among older people were found to be personal factors such as personal norms and pro-environmental self-identity and gender. Thus, these results support the conclusions formulated by Joshi and Rahmen (2015): that green purchase behaviour represents a complex form of ethical decision-making and is considered a type of socially responsible behaviour. In the case of behaviour related to buying organic and healthy food and packing grocery products in consumers' own bags, their predictors are social norms, pro-environmental self-identity, and gender. These results are in line with previous studies on organic food purchasing carried out among adults (Ruiz de Maya et al., 2011; Teixeira et al., 2021; Zagata, 2012). For example, research by Vermeir and Verbeke (2006) integrating personal and contextual factors proved that involvement with sustainability and experiencing social pressure from peers (social norms) have a significant positive impact on attitude towards buying sustainable dairy products.

In our study, gender is an important predictor of sustainable shopping behaviour. Women show sustainable purchasing behaviour to a greater extent than men. It can be justified by the traditional family model common in Poland. Women are more responsible for nutrition and purchasing decisions than men. This result is consistent with previous findings on sustainable consumption in various age groups (Azzurra et al., 2019; Rejman et al., 2019; Schäufele & Hamm, 2017).

Education and income, as manifestations of consumers' personal abilities, are not predictors of sustainable food purchasing behaviour of people 55+. In the case of education, this result is consistent with some previous studies on organic food purchases (Niva et al., 2014; Rejman et al., 2019). In contrast, income, indicated as a significant factor for organic food purchases in previous studies (Gracia & De Magistris, 2007; Rimal et al., 2005), is not a predictor of this type of behaviour among older adults in our case, as well as of packing food in consumers' own bags/containers. Instead, correlation analysis has shown a relation between income level and behaviour of buying food in appropriate quantities to prevent food waste. What is surprising, however, is the direction of this relationship, as the lower the income, the weaker this behaviour manifests itself, so wealthier older people show more concern for rational food shopping, and avoid wasting food. Existing analyses indicate that the scale of food waste depends on the wealth of countries (Hodges et al., 2011). as well as on consumer wealth (Yu & Jaenicke, 2020) and increases with increasing wealth. At the same time, it is in this dimension that a sustainable approach to food shopping manifests itself particularly clearly among mature Poles. In view of this, it is worth pursuing further research, looking for predictors of this behaviour, and consequently extending the range of explanatory variables in our proposed model. It seems that, given the age of the respondents, habits and routine in food purchasing may turn out to be important. Previous studies confirm that older consumers tend to have established consumer habits. They usually purchase familiar staple products and remain loyal to specific products and brands (Castelo Branco & Alfinito, 2023; Lee & Evenson, 2015). They also exhibit resistance to changing their shopping habits, which can limit their willingness to explore diverse food options. Therefore, an important direction for future research should focus on identifying effective strategies to influence the purchasing habits of this consumer group. Behavioural economics suggests that changes in the decision-making processes of elderly consumers can be achieved through targeted training and the influence of social groups (Chen, 2024).

Our research did not confirm the importance of the contextual factor: perceived affordability of green products (not a significant predictor of organic food purchases). Thus, we have not confirmed previous findings of a significant influence of price on the purchase of organic food (Gleim et al., 2013; Vermeir & Verbeke, 2006). Other authors point out the significant role of other external factors in the purchase decision of organic products, which is their availability (Vermeir & Verbeke, 2006). Given that in Poland the organic food market represents only 0.4 percent of the food market (the EU average is around 4 percent) (PMR Market Experts, 2020), it is worth including this predictor in further research when analysing green food purchases among older adults.

The regression analysis revealed that in our study group of silver consumers, declared knowledge on sustainability did not influence sustainable purchasing behaviour. Similarly, their education did not determine this behaviour. However, many other studies indicate knowledge as an important determinant of sustainable food consumption (Chan, 2001; Zameer & Yasmeen, 2022). Again, it seems that the reason for the lack of this dependency is the specificity of the study group. Mature Poles, in general, did not have the chance to acquire knowledge on sustainable development and green food products in the course of their formal education. The interest of politicians and educators in such issues began to develop in Poland after 2004, since the accession to the European Union. Prior to that, issues of sustainability and sustainable consumption were basically ignored.

The results obtained did not allow us to distinguish predictors for the behaviour “buying food in appropriate quantities to prevent food waste”. The most probable reason for this is the insufficient number of indicators describing this behaviour, which we consider to be the limitation of our study. The F2 factor is constructed by two indicators, which results in its incomplete measurement.

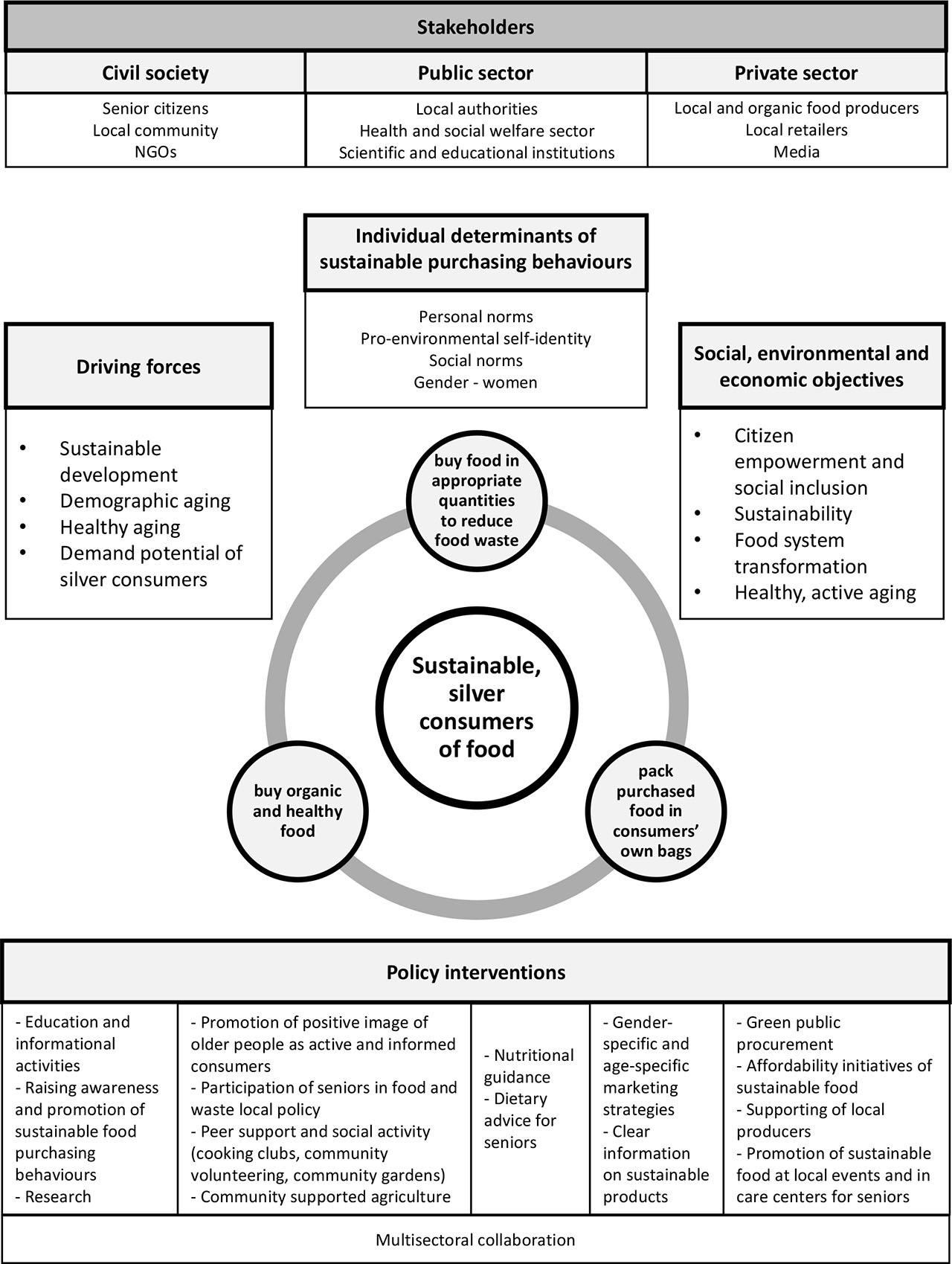

The results obtained enable us to propose specific methods of strengthening and shaping pro-environmental food purchasing behaviour among older consumers, which we integrate into the framework (Figure 4). They may be useful for shaping local food policies, especially in cities experiencing demographic transition and silver market food producers.

Framework for Shaping Sustainable Food Purchasing Behaviours of Silver Consumers at Local Level

The study identified a statistically significant relationship with three factors: personal norms, pro-environmental self-identity, and gender. When holding other factors constant, a higher score in personal norms is associated with more sustainable food purchasing behaviour, which is further facilitated by a stronger pro-environmental self-identity. Environmental awareness and a value system that incorporates sustainability into everyday purchasing behaviour can be fostered through educational and informational activities. These initiatives can be organized and implemented by NGOs, scientific institutions, science popularisers, doctors, local food producers and local authorities. The content provided should highlight the environmental, social, and health benefits of consuming healthy and sustainable food. Older consumers should be informed about how their choices contribute to sustainable agricultural practices, support local food producers, reduce waste, and contribute to a healthier planet. They can also actively participate in citizen science, local food policy-making, or social innovations such as community gardens. The mentioned educational activities may influence changes in the existing food purchasing habits of mature individuals.

Based on the findings of our research, individuals who value social norms in sustainable consumption are more likely to engage in behaviour such as purchasing organic and healthy food and using their own packaging for food products. It is worthwhile to emphasize, in educational and informational activities, that sustainable food purchasing behaviour is widely accepted, desired, and supported by the community. Sustainable food consumption can serve as the foundation for local support networks and social activities, with the backing of local authorities and food producers.

Social activities like cooking clubs, community volunteering, or community gardens provide opportunities for seniors with ample leisure time to connect, share experiences, and learn from one another. This fosters interaction among like-minded individuals who share pro-environmental values and beliefs, reinforcing personal and social norms regarding sustainable food purchasing among older people, as indicated by our research.

In light of the lower interest in purchasing organic food found in our study, an important area requiring public policy support is long-term research on the impact of organic food consumption on the health of older individuals. Educational activities based on the research findings should provide clear information on the potential health benefits of consuming organic products, with a specific emphasis on how organic food can positively impact the health issues commonly faced by seniors. To enhance the effectiveness of such educational activities, collaboration with health professionals, dietitians, and nutritionists is essential.

The role of food producers and retailers is also crucial in this regard. They should strive to provide clear and easily accessible information on the sustainability of products, including organic food options. This can help address knowledge gaps and enable older consumers to make informed choices based on their sustainability preferences and values. Additionally, the availability (accessibility and affordability) of organic products should be addressed through joint efforts by the private and public sectors. Supporting local producers and sellers of healthy food, advocating for the use of organic options in public and private senior care centres, cafeterias, and hospitals is worth considering. Introducing appropriate clauses in public procurement or offering preferential local tariffs for healthy food vendors and producers could be helpful strategies. Promoting local producers and vendors within the community is also of great importance.

The results of our study clearly demonstrate the significance of gender as a determinant of sustainable food purchasing behaviour. In the overall assessment of the studied phenomenon, as well as for sub-scales F1 and F3, women consistently score significantly higher than men. Therefore, it is crucial to establish a framework for women's participation in policymaking to support sustainable consumption among seniors. Local senior citizens' councils could serve as a suitable platform for their involvement in activities promoting the concept of sustainable consumption among mature individuals in Poland. These councils, established as a result of the amendment to the Act on Municipal Self-Government in 2013 (Journal of Laws 2013, item 1318), fulfil consultative, advisory, and initiative functions concerning the local elderly community. Similar advisory bodies exist in other countries in Europe and beyond, such as Denmark, Ireland, and Germany, where they have been operating since the 1970s (Falanga et al., 2020; Frączkiewicz-Wronka et al., 2019).

In addition to the senior citizens' councils, it is valuable to encourage women interested in sustainable consumption issues to share their experiences, knowledge, and best practices with other local organizations such as senior citizens' clubs and centres. Highlighting the sustainable shopping behaviour of older women can also serve as an important guideline for companies when designing their marketing strategies. Food manufacturers and retailers can target this demographic group with marketing activities that emphasize the sustainability of their products, promote environmental benefits, and demonstrate how women's everyday purchasing choices impact the environment.

Implementing the aforementioned methods necessitates multi-sectoral cooperation within local communities and on a national scale. Empowering older people themselves is also crucial in this endeavour.