Autoimmune diseases affect approximately 5%–7% of the population. Generally, autoimmune diseases are divided into organ-specific, such as autoimmune thyroiditis, or organ-non-specific, including conditions like systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (Figure 1). They are caused by immune dysregulation in various organs, such diseases as liver diseases (autoimmune hepatitis, sclerosing cholangitis), endocrinological disorders (autoimmune thyroiditis, diabetes mellitus), dermatological problems (vitiligo, psoriasis, pemphigus), and connective tissue diseases (CTDs) (Davidson and Diamond 2001). CTDs usually develop in reproductive age and may be characterized by antinuclear antibodies (ANAs). Identifying these antibodies is paramount in diagnosing autoimmune disorders (Fernandez et al. 2003). When ANA positivity aligns with clinical symptoms, it enables the specific diagnosis of CTDs (Grygiel-Górniak et al. 2018). Significantly elevated ANAs titers are detectable in SLE, systemic sclerosis (SSc), primary Sjögren's syndrome (pSS), mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD), and idiopathic inflammatory myopathies (such as polymyositis [PM] and dermatomyositis[DM]). However, ANAs in low to medium titers are also present in 20%–30% of the average healthy population without autoimmune diseases (Kumar et al. 2009).

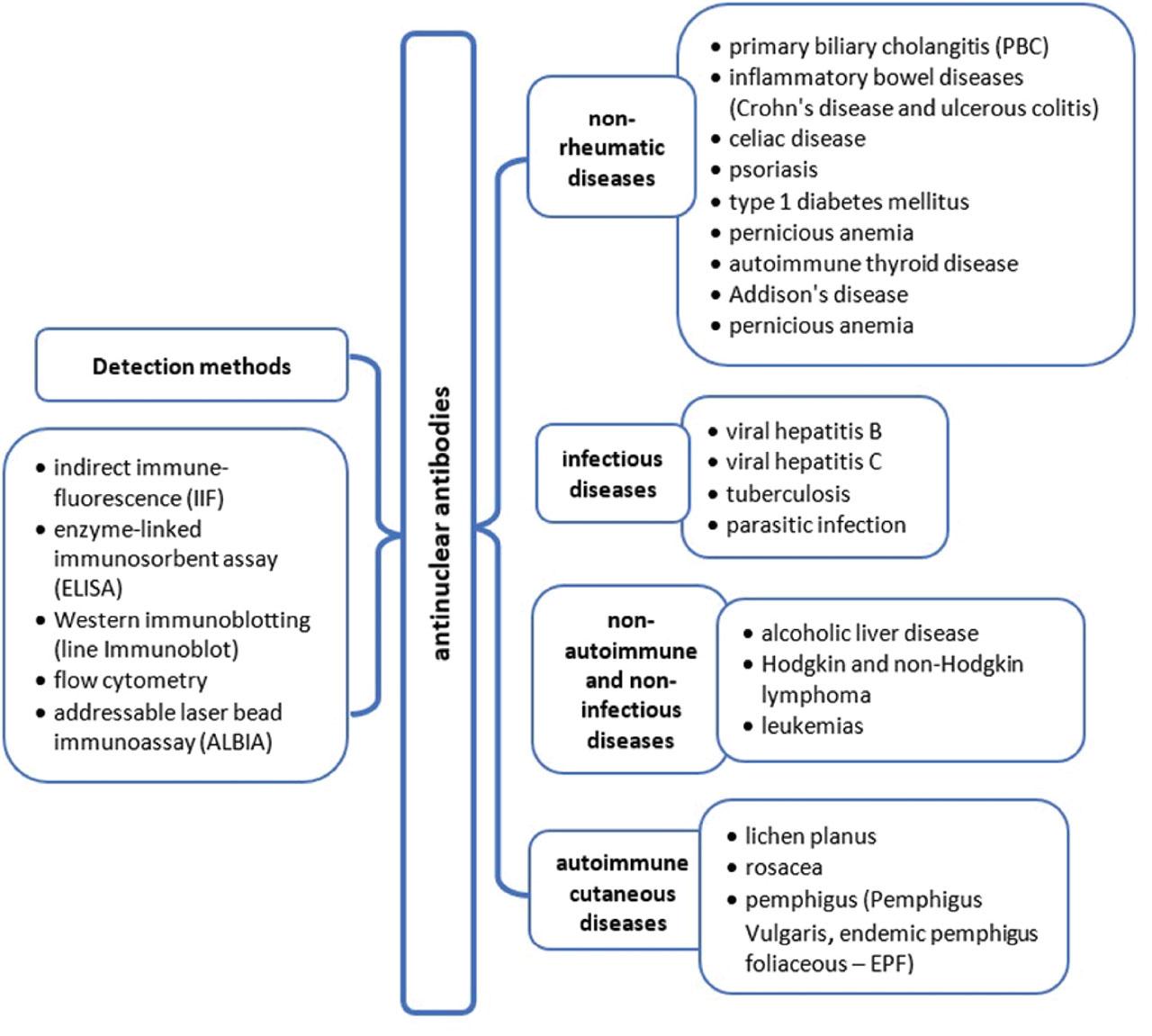

ANAs in non-rheumatic diseases. ALBIA, addressable laser bead immunoassay; ANAs, antinuclear antibodies; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; EPF, endemic pemphigus foliaceous; IIF, indirect immunofluorescence; PBC, primary biliary cholangitis.

The measurement of ANAs includes analysis of ANA titer, type of fluorescence, and ANA profiles, which allows for estimating many subtypes of ANA specific to particular CTDs. Thus, ANAs are helpful immunological markers of many rheumatic diseases, enabling their diagnosis and differentiation (Bossuyt et al. 2020). In certain conditions, the presence of ANAs is pivotal for diagnosis; for instance, SLE cannot be diagnosed without these antibodies (Chakravarty et al. 2007). According to the new 2019 SLE classifications criteria, ANA titers should be in a minimum of 1:80 by human epithelial type 2 (Hep-2) indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) or an equivalent test by solid phase immunoassays. ANAs profile enables the analysis of specific systemic CTD antibodies. While anti-double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) (43%–92%), anti-nucleosome (59.8%–61.9%), and anti-Sm (15%–55.5%) antibodies are commonly associated with SLE and are included in the immunological criteria for diagnosis (Kumar et al. 2009), other antibodies, such as anti-Ro/SSA antibodies (anti-Ro)/SSA (36%–64%) and anti-La/SSB (8%–33.6%), may also be presented in the disease. Although antibodies against Sjögren's-syndrome-related antigen A (anti-SSA) and anti-Sjögren's-syndrome-related antigen B (anti-SSB) are characteristic of pSS, other antibodies, such as anti-Ro52 (33%–77.1%), can also be detected in this condition (Didier et al. 2018). Typical for SSc are anti-topoisomerase 1 (anti-Scl-70), anti-centromere protein B, and anti-RNA polymerase III antibodies. While anti-Scl-70 is strongly associated with diffuse cutaneous SSc (dcSSc) and significant organ involvement, anti-centromere antibodies (ACA) and anti-RNA polymerase III correlate with specific clinical features and subtypes of scleroderma. ACA is mainly associated with limited cutaneous SSc (lcSSc) and its distinct clinical manifestations, including a higher risk of pulmonary hypertension. Anti-U1 ribonucleoprotein antibodies are distinguishing for MCTD, while anti-Jo1 are detected in inflammatory myopathies such as PM/DM (Bossuyt et al. 2020).

Various intrinsic immunological dysregulations can stimulate ANA synthesis in healthy subjects. Recent data confirm that up to 20% or more of healthy people can express an ANA, though the actual frequency of positive assays varies with the type of immunological tests (Pisetsky 2011; Li et al. 2019; Ge et al. 2022). Nevertheless, in healthy populations, these antibodies are more commonly expressed in women than men. Hormonal drugs, including extrinsic estrogens, seem to play a crucial role in the synthesis of ANA, and their elevated level is found in women using oral contraception (Grygiel-Górniak et al. 2018). The higher titers of ANAs are observed in African Americans than in Caucasians and Asians (Pashnina et al. 2021). Moreover, latent infection can stimulate the synthesis of these antibodies. ANAs are also elevated by various medications, food additives, and harmful environmental factors, as well as in patients with non-rheumatic autoimmune diseases (Satoh et al. 2012).

Positive ANA titers greater than 1:100 are observed in 2%–8% of healthy individuals in Lebanese and Mexican populations (Marin et al. 2009; Racoubian et al. 2016). The authors of both analyses underline that the prevalence of these antibodies depends on gender, age, or ethnicity. Nevertheless, ANAs are detected twice as often in healthy women than in men (Marin et al. 2009; Racoubian et al. 2016; Li et al. 2019). The prevalence of ANAs and their amount (titer) increases with age, reaching 54.3% in patients between 50 years old and 69 years old (Giannouli et al. 2013).

Although ANAs can be detectable in healthy individuals, markedly elevated levels are observed in merely 2.5% of the populace (Davidson and Diamond 2001). However, recent data show that the prevalence of ANAs varies from 7.09% to 14% of healthy subjects. The study of Li et al. (2019), analyzing 25,110 individuals for a routine examination, found positive ANAs titer >1:100 in 14.01% of subjects—19.05% of females and 9.04% of males. The specific antibodies were detected in 1489 ANA-positive people with titer >1:320, and the most often present antibodies were anti-Ro-52 (n = 212), AMA-M2 (n = 189), and anti-SSA (n = 144) (Li et al. 2019). According to international reports, ANAs may be detected in low titer in 40%–45% of healthy individuals, and their prevalence increases with age (Op De Beéck et al. 2012). Asymptomatic (healthy) people frequently have these antibodies present for extended periods, sometimes for years (Fernandez et al. 2003). Many of them usually do not develop autoimmune diseases; however, it is unclear whether high concentrations of ANAs have potential damage to the body (Chakravarty et al. 2007).

ANAs tests are based on detecting antibodies directed against the cell nucleus. The most commonly used test is the IIF test, which is the most frequently used method. The IIF test is considered the “gold standard” for screening and is preferred by most expert panels and guidelines (Table 1). The substrate for this assay is Hep-2 cells. This method employs fluorescently labeled anti-human immunoglobulins to reveal ANAs presence within a patient's sample. Hep-2 cells are cultured to make their nuclei accessible for ANAs binding, and the labeled antibodies facilitate clear visualization of these interactions under a fluorescence microscope. This technique not only confirms ANA's existence but also aids in recognizing patterns that assist in diagnosing specific autoimmune conditions. It enables the estimation of ANA's titer and their fluorescence pattern (e.g., speckled, homogeneous, nuclear mixture, and cytoplasmic mixture patterns; Peng et al. 2014). It is a valuable approach for ANA detection and analysis, commonly used in clinical practice (Kumar et al. 2009).

Methods used for ANA detection

| Methods for ANA measurement | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Method | Method description | Advantages | Limitations |

| IIF |

|

|

|

| ELISA |

|

|

|

| Western immunoblotting (line ImmunoBlot) |

|

|

|

| Flow cytometry |

|

|

|

| ALBIA |

|

|

|

ALBIA, addressable laser bead immunoassay; ANAs, antinuclear antibodies; CIE, counter-current immunoelectrophoresis; CTD, connective tissue disease; DID, double immunodiffusion; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; Hep-2, human epithelial type 2; IIF, indirect immune-fluorescence.

Moreover, the IIF method enables the assessment of both the titer and type of fluorescence of ANAs. Most laboratories use single dilutions during initial screening, e.g., 1:40 or 1:80 (Deng et al. 2016). According to specific statistical data, the level of ANA in non-rheumatic diseases can be as low as 1/80 compared to the ratio observed in healthy individuals. It is worth emphasizing that false-positive results may occur in some patients due to antibodies' non-specific binding and closely related antigens sharing similar epitopes (Scholz et al. 2015). A poor specificity and low positive predictive value of IIF can cause false positive results in 30% of healthy individuals at low serum dilution (e.g., titer 1:40) and older age (Solomon et al. 2002). The clinical significance of the test is better with increasing titers and the precise identification of the responsible specific autoantigen (American College of Rheumatology Ad Hoc Committee on Immunologic Testing Guidelines 2002; Op De Beéck et al. 2012). The estimation of the correct dilution titer depends on the technician's experience reading the immunofluorescence slides (Agmon-Levin et al. 2014; Alsaed et al. 2021).

A negative IIF result is conclusive, while a second independent method must confirm all positive results. The second stage of ANAs diagnostics is based on monospecific tests (ELISA or ImmunoBlot), in which the antigenic specificity of the tested antibodies is determined (Murdjeva et al. 2011).

As mentioned above, the IIF method is susceptible to interobserver variability, making it subjective. Staff training is crucial for the measurement method. The photobleaching effect can alter the information content of images, and the lack of automated procedures can affect the variability of cellular substrates (Pham et al. 2005; Rigon et al. 2017). Adopting a double-blind reading method to reduce subjectivity in result interpretation is strongly recommended, depending on the reader's experience. The American College of Rheumatology ANA task force has endorsed the IIF on Hep-2 cells as the gold standard test for ANA detection, which, along with advancements in IIF automation, has led to a “renaissance” of IIF (Meroni and Schur 2010; Agmon-Levin et al. 2014). Many laboratories follow the practice of initial ANA IIF screening on antibody patterns and titers, followed by a confirmatory monospecific test (e.g., ELISA or immunoblot) to identify the autoantibody (Ricchiuti et al. 2018; Tabatabaei and Ahmed 2022). Computer-aided diagnosis systems can further support the interpretation of ANA IIF slides (Rigon et al. 2011; Soda et al. 2011).

Two important automated methods, ELIA CTD screen/enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), are currently used for ANA testing. ELIA is a bland test that detects ANAs of broad specificity comparable to an indirect immunofluorescent test. The ELISA method is the most commonly used in clinical practice and research. ELISA is a precise method of ANA testing for detecting autoantibodies targeting nuclear antigens within serum or plasma samples (Jaskowski et al. 1996; Kohl and Ascoli 2017). In this method, specific antigens coated onto microtiter plates enable the detection of various antibodies such as anti-dsDAN, anti-SSA/Ro, anti-U1-RNP, anti-SSB/La, anti-Sm, anti-Jo-1, anti-Scl70, and many others. Compared to the indirect immunofluorescent test, the ELISA method is more specific and sensitive and does not require a lengthy analysis time (Jaskowski et al. 1996). The line blot immunoassay method is a qualitative technique used to assess antibody reactivity. This method involves the application of antigens onto a membrane in distinct lines. Its advantages extend beyond the ELISA test, encompassing high sensitivity, specificity, ease, rapidity of execution, and the potential for automation. This technique is particularly relevant in detecting and analyzing ANAs in non-rheumatic diseases, as it precisely identifies antibody reactions against nuclear antigens. The line blot immunoassay employs a nitrocellulose membrane with a necessary number of strips, each placed in its respective row on an incubation tray (Damoiseaux et al. 2005). This setup facilitates the simultaneous assessment of multiple ANA reactivities, comprehensively estimating the antibody profiles in non-rheumatic conditions. Many factors limit accurate, reproducible western blot quantification; therefore, the method is considered to be only semiquantitative (Gilda et al. 2015; Butler et al. 2019; Lallier et al. 2019).

The reflex ANAs flow cytometry test evaluates antibody reactivity using beads with fluorescent signals and antigens. This strategy confers many advantages, including concurrent antigen recognition, increased sensitivity for subtle responses (low titer of specific ANA), economical multi-antigen testing, and the potential for automation (Bonilla et al. 2007). This approach may result in significant false negative and false positive findings, causing clinical confusion. Some disorders, including non-rheumatic conditions such as autoimmune hepatitis, may yield negative results on reflex ANA, while IIF testing may reveal positive results for these conditions. Reflex ANA testing should be done cautiously to guarantee an accurate diagnosis, and its findings should be verified by additional diagnostician techniques such as IFF.

The advent of multiplex bead assays, also known as addressable laser bead immunoassay (ALBIA) or Luminex® (Austin, TX, USA) technology, is based on the application of autoantigen array and flow technologies (Satoh et al. 2015; Swana et al. 2019). This new-age method is used in various immunoassay, genomic, and proteomic analyses (Giavedoni 2005). The exquisite feature of ALBIA is the ability to assess several antibody specificities simultaneously in a small serum sample, and it is considered an alternative to the use of ELISA (Satoh et al. 2015). For example, ALBIA enables the measurement of many antibodies (including ANA) in biological fluids, screens supernatants for monoclonal antibodies, quantitates cytokines in cell extracts and biological fluids, and some genetic evaluations (Rouquette et al. 2003; Gilburd et al. 2004; Fritzler et al. 2006). Even though ALBIA technology is widely used, this method also has disadvantages. For example, one serum may react with many autoantigens in a multiplexed ALBIA (Fritzler et al. 2006). Nevertheless, many data confirm that ALBIA technology is reliable, accurate, cost-saving, and efficient, has a rapid turnaround time, can be applied for limited-volume samples, has high sensitivity, and has less dependence on highly skilled operators (Fritzler et al. 2006). ALBIA technique offers the advantages of simultaneous assessment of multiple autoantibodies. ALBIA method used with the Luminex platform enables similar performance characteristics and a high level (>90%) of agreement with ANA and conventional ELISA techniques (Shovman et al. 2005). ALBIA method can be broadly used in CTD, vasculitis, and autoimmune thyroid disease (Gilburd et al. 2004; Hanly et al. 2010; Austin et al. 2012; Swana et al. 2019).

ANAs can be present in patients with autoimmune not-rheumatic diseases, such as primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) (Crohn's disease and ulcerous colitis), psoriasis, type 1, celiac disease (CD), pernicious anemia (PA), autoimmune thyroid disease, and Addison's disease (AD) (Table 2).

The prevalence of ANAs non-rheumatic autoimmune diseases

| Disease | Analyzed groups | ANAs presence/detection of specific antibodies | ANAs detection method | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBC | n = 32 |

| IIF | Walker et al. (1965) |

| Psoriasis |

|

| IIF | Patrikiou et al. (2020) |

|

| ELISA | Singh et al. (2010) | |

| DMt1 |

|

| IIF | Heras et al. (2010) |

|

| IIF | Notsu et al. (1983) | |

| CD | n = 101 |

| IIF | Carroccio et al. (2015) |

| n = 161 |

| IIF | Almeida et al. (2019) | |

| Autoimmune thyroid disease |

|

| IIF | Lanzolla et al. (2023) |

|

| IIF using Hep-2 cells as substrate | Tektonidou (2004) | |

| n = 104 |

| IIF using Hep-2 cells as substrate | Torok and Arkachaisri (2010) | |

| PA |

|

| Indirect IIF | Morawiec-Szymonik et al. (2019) |

| AD | n = 1 |

| Serological screening | Yazdi et al. (2021) |

| 29-year-old with clinical features of acute Addisonian crisis and SLE |

| Serology screening | Godswill and Odigie (2014) |

21-OH Abs, AD-21-hydroxylase antibodies; ACA, anti-centromere antibody; aCL, anti-cardiolipin antibodies; AD, Addison's disease; ANA, antinuclear antibody; anti-dsDNA, anti-double stranded DNA; anti-Ro, anti-Ro/SSA antibodies; ATD, autoimmuine thyroid diseases; ATG, anti-thyroglobulin; ATPO, anti-thyroperoxidase; CD, celiac disease; ELISA, enzyme linked immunosorbent assay; GD, Graves' disease; GO, Graves' orbitopathy; Hep-2, human epithelial type 2; IIF, immunoflurosecence; PA, pernicious anemia; PBC, primary biliary cholongitis; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; DMt1, diabetes mellitus type 1.

PBC is an autoimmune liver disease (AID) characterized by slow progressive destruction of the small bile ducts and can cause cirrhosis of liver tissue. PBC is characterized by anti-mitochondrial antibodies (AMA), which target the E2 subunits of the 2-oxo acid dehydrogenase complexes (PDC-E2) on the inner mitochondrial membrane. These antibodies serve as hallmark indicators of the disease and are detected in approximately 90% of patients (Colapietro et al. 2021). Furthermore, ACA has also been detected in up to 30% of patients with PBC and 80% of those with an overlap syndrome of PBC and SSc (Liberal et al. 2013). Moreover, about one-third of PBC patients may exhibit ANAs. The frequency of ANA-positivity tends to increase as the disease progresses (Invernizzi et al. 2005). PBC can be associated with other diseases of autoimmune origin, such as secondary Sjögren's syndrome, Hashimoto thyroiditis, non-rheumatoid arthritis, and rarely limited scleroderma.

The initial study by Walker et al. (1965) analyzed the ANA titers in 32 patients diagnosed with PBC. The ANA tests were positive in 10 patients, with titers ranging from 1/20 to greater than 1/1600. Four displayed diffuse nuclear staining patterns among these individuals, while five exhibited the “speckled” staining pattern (Walker et al. 1965).

PBC is the most common liver disorder in patients with SSc but is not a scleroderma feature (Abraham et al. 2004). The prevalence of clinically evident PBC among patients with SSc varies from 2.0% to 2.5% (Assassi et al. 2009; Rigamonti et al. 2011). Conversely, the prevalence of SSc in patients with PBC is about 8% (Watt et al. 2004; Rigamonti et al. 2011). Nevertheless, many case reports show a higher prevalence of SSc (mainly localized SSc) in PBC patients (Rigamonti et al. 2011). ANA, typically for SSc and PBC, predominates in antibody profiles in such patients.

Furthermore, SSc can be categorized into two main subtypes based on the extent of skin involvement: lcSSc and dcSSc. ACAs are a hallmark of SSc, found in up to 90% of patients with lSSc. Interestingly, ACA is also detected in up to 30% of patients with PBC and 80% of those with overlapping PBC and SSc. Recent research has focused on the diagnostic and clinical implications of ACA positivity in PBC patients who do not have SSc. These studies suggest that ACA positivity in PBC is associated with more severe bile duct damage and an increased risk of portal hypertension, underscoring the importance of ACA as a potential marker for disease severity in PBC (Liberal et al. 2013; Favoino et al. 2023).

The prevalence of ANA in patients without SSc is different, and usually, typical AMA are detected. AMA titers do not correlate with the course of the PBC or histological progression. After liver transplantation, AMA reoccurs nearly 100% (Leuschner 2003). However, ANAs are only sometimes detected.

In the literature, two different IIF ANA patterns specific to PBC have been described as AMA-negative (Leuschner 2003; Invernizzi et al. 2005). One of them is “multiple nuclear dots” typical for the antigens Sp100, Sp140, promyelocytic leukemia nuclear body proteins (PML), and small ubiquitin-like modifiers (SUMO) (Sternsdorf et al. 1995; Granito et al. 2010). Another one is the “nuclear membrane” (rim) pattern present in the case of antibodies against nucleoporin p62 and gp210 (Courvalin et al. 1990; Wesierska-Gadek et al. 1996; Invernizzi et al. 2005). Both ANA patterns are specific for PBC and are detected in 30% of this disease (Rigopoulou et al. 2005). They are crucial in diagnosing PBC cases with a clinical suspicion of PBC and lack AMA (Vergani and Bogdanos 2003). Thus, anti-Sp100, anti-Sp140, anti-PML, anti-SUMO, anti-p62, and anti-gp210 are strongly linked with PBC and are present in approximately 25% of individuals diagnosed with this biliary disease (Worman and Courvalin 2003).

IBD, such as Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis ulcer, are immune-mediated diseases associated with gastrointestinal inflammation and extraintestinal manifestations in about one-third of patients (Vavricka et al. 2015). In irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), there is significant variability in the prevalence of ANA, which depends on the methods used and selected detection titers (Barahona-Garrido et al. 2009). For example, the study of Garcia has shown positive ANAs in 13% of patients with IBD (García et al. 2022).

In the course of IBS, ANA synthesis is observed; however, treatment might also increase ANA synthesis, particularly mesalazine use. In IBS patients treated with mesalazine, ANAs are detected in 66.8% of subjects without any other autoimmune diseases (also without CTD). These antibodies in 5% of patients cause lupus-like syndrome (LLS) (Aghdashi et al. 2020). Other medications, such as anti-tumor necrosis factors (anti-TNF) used for IBS treatment, such as anti-TNF therapeutics (infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol), stimulate ANA synthesis in 20%–45% of patients (Vaglio et al. 2018). However, recent studies point out that conversely to mesalazine, anti-TNF treatment (even added to mesalazine) reduces ANA synthesis in IBS patients (Beigel et al. 2011; García et al. 2022). Interestingly, such treatment also decreases the production of antibodies against anti-TNF (Kennedy et al. 2019). The exact mechanism of the mentioned processes is not known, but it is suspected that the reduction in memory T cells through Rac-1 can be responsible for decreasing ANA synthesis (Tiede et al. 2003). Thus, most IBS patients experience seroconversion after the beginning of biological treatment and with a slight risk of suffering LLS (García et al. 2022).

CD is a well-characterized autoimmune disorder with a prevalence of approximately 1 in 100, occurring predominantly in individuals carrying HLA-DQ2 or HLA-DQ8 genotypes. The disease pathogenesis involves a robust CD4+ T-cell response to post-translationally modified gluten and specific B-cell responses to deamidated gluten and the self-protein transglutaminase 2. Understanding these immune mechanisms provides crucial insights into CD's development and progression (López Casado et al. 2018).

Recent studies have investigated the prevalence of ANA in individuals with CD, revealing notable findings. One Italian study found that ANA was present in 24% of the CD population. This study utilized an indirect immunofluorescence method on Hep-2 cells, with a titer of 1:40 or above considered positive. The study cohort, predominantly female (91 out of 101 participants), had an average age of 40.1 ± 12.3 years. Additionally, the study identified a positive correlation between the presence of ANA and HLA DQ2/DQ8 haplotypes. Specifically, 49 out of 59 individuals with non-celiac wheat sensitivity who tested positive for ANA carried these haplotypes, as did all participants with CD (Carroccio et al. 2015).

Another study evaluated the sera of 161 individuals with biopsy-confirmed CD (103 females; average age 17 ± 14 years) for ANA using immunofluorescence on Hep-2 cell substrates. ANA positivity was identified in 14 samples (8.7%). The positive sera exhibited distinct nuclear staining patterns, categorized as homogeneous nuclear, nuclear fine-speckled, and nuclear coarse-speckled (Almeida et al. 2019). The presence of ANA in CD patients might serve as an indicator of adaptive autoimmunity. It could be a valuable screening tool for identifying individuals at risk of developing additional autoimmune conditions. However, the clinical implications of ANA positivity in CD patients are not yet fully understood (Yang et al. 2018).

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by silvery scale plaques on the skin that occur above the joints on the extensor surfaces, scalp, and lumbosacral regions (Grygiel-Górniak and Skoczek 2023). In psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis (PsA) patients, the innate immune system is activated due to endogenous signals and the synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Rendon and Schäkel 2019). In both diseases, ANA antibodies might be synthesized; however, they usually have no clinical meaning. The study of Singh et al. (2010) shows that anti-dsDNA antibodies are found in about 17% of patients with psoriasis with an average psoriasis duration of 6.67 ± 8.7 years and a greater prevalence in males (in 57.1% of males vs. 42.9% of females). The results of this study reveal that even in the absence of apparent clinical signs of autoimmune disease, ANAs can be found in people with psoriasis. Thus, such patients should be consulted by a rheumatologist in case of symptoms typical for CTDs, which can co-exist with psoriasis or PsA (Singh et al. 2010).

ANAs can also be synthesized during psoriasis or PsA therapy, for example, by implementing anti-IL-17 therapy (secukinumab). The results revealed that 20.4% of patients with psoriatic disease exhibited antibody reactivity to at least one nuclear antigen, with a higher prevalence in Ps patients (25.7%) than those with PsA (15%). However, this was not statistically significant compared to healthy controls (8%). Among the various nuclear antigens, the most common autoantibody specificity was against dense fine speckled 70 (DFS70), detected in 6.5% of psoriatic patients (13/201) with female predominance compared to 2% of healthy controls (1/50); though, this difference was not statistically significant. Notably, 76.9% (10/13) of anti-DFS70 positive patients exhibited the corresponding dense fine speckled pattern. Furthermore, in patients achieving remission with secukinumab, a reduction in DFS70 and other nuclear antigen reactivity was noted, alongside decreased plasmablasts, follicular B cells, and follicular T cells. This suggests secukinumab may reduce nuclear antigen autoreactivity, providing insight into its immunomodulatory effects in psoriasis (Patrikiou et al. 2020).

The study of Ozaki et al. (2022) showed the presence of ANA in 27 patients (21.3%) from a group of 127 subjects with psoriasis before starting biologics. The ANA titers were ×40, ×80, ×160, and ×640 in 18 (14.2%), 7 (5.5%), 1 (0.8%), and 1 (0.8%) patients, respectively. Among ANA-positive patients, homogeneous, speckled, nucleolar, and granular patterns were observed (Ozaki et al. 2022). Fine-speckled fluorescence has very low specificity and may indicate the presence of CTDs and psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and cancers (Lundgren et al. 2021). Most literature on ANA in psoriasis includes case reports or biologic-induced antibody synthesis (causing SLE-like syndrome). A case report by Astudillo et al. (2003) reported three cases of psoriasis preceded the diagnosis of SLE during 7-year observation. An extensive analysis of 9400 psoriasis patients in a 10-year retrospective study identified 42 cases of SLE (Zalla and Muller 1996). Since psoriasis may co-exist with other autoimmune diseases, the Biologics Review Committee of the Japanese Dermatological Association for Psoriasis recommends blood examination tests for ANA and other autoantibodies tests before initiation of biologics at screening (Saeki et al. 2023). The detection of ANA is also important during biological treatment because ANA and anti-dsDNA antibody synthesis in anti-TNF treatment may be a marker of forthcoming treatment failure (Golberg et al. 2011).

In the course of type 1 diabetes (DMt1), autoimmune destruction of insulin-producing beta cells is observed due to the invasion of pancreatic islets by CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes, macrophages, and other immune cells (Gillespie 2006; Buzzetti et al. 2017). Data on the presence of ANAs in type 1 diabetes indicate their presence in 27% of patients. Additionally, approximately 53% of ANA-positive patients exhibited a diffuse staining pattern upon immunofluorescence analysis, often linked to rheumatological conditions like SLE and rheumatoid arthritis. Since ANA tests are usually performed only once, it is not known whether the ANA association is transient in the course of type 1 diabetes or whether it is associated with the potential development of systemic CTD in the future. Therefore, long-term studies including a bigger population are required to prove such a relationship (Heras et al. 2010).

ANAs are also detected in the pediatric population with diabetes. The study of Notsu et al. (1983) analyzed 80 children with DMt1 aged 7–18 years and 473 healthy children aged 6–16 years without diabetes (control group). Additionally, 1125 adults took part in the study. The study used a standard IIF technique for ANA detection. The results showed that 1.1% of adult participants (12/1125) and 16.2% of children with diabetes (13/80) tested positive for ANA. Thus, a significantly higher prevalence of ANAs among children with type 1 diabetes is observed compared to adult populations as well as healthy children (ANAs were detected in 0.6% of pediatric controls) (Notsu et al. 1983).

Autoimmune thyroid diseases (ATD) arise from immune system dysregulation due to the synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines and anti-thyroid antibodies. ATD encompasses T cell-mediated autoimmune disorders specific to the thyroid. Recent research emphasizes the relevance of cytokines and chemokines in the development of autoimmune thyroiditis and Graves' disease (GD) (Antonelli et al. 2015). Thyroid tissues frequently show activation of CD8+ and/or CD4+ cells, with CD4+ cells predominating in ATD patients. Additionally, there is a higher presence of active T lymphocytes expressing HLA-DR (Ragusa et al. 2019).

Lanzolla et al. (2023) examined the prevalence and impact of ANAs in ATD, particularly GD and toxic nodular goiter (TNG). In a cohort of 265 GD patients, 80% had detectable ANAs, predominantly at low titers (1:80 or 1:160). The presence of ANAs did not differ significantly between those with or without Graves' orbitopathy (GO), though higher ANA titers were more common in GO patients. ANA-positive GO patients exhibited milder symptoms, such as reduced proptosis. Interestingly, TNG patients had a higher ANA prevalence (91%) than GD (80%). Still, GD patients displayed the nuclear speckled ANA pattern more frequently, while TNG showed a trend toward the nuclear dense fine speckled pattern. These findings suggest that ANAs, especially the nuclear-speckled pattern, may be associated with reduced GO severity and could have a protective role in GD (Lanzolla et al. 2023).

A higher prevalence of ANAs in ATD was also confirmed in the study of Tektonidou (2004), which showed ANAs presence in 35% of ATD patients (n = 168) and 9% of controls. ANA-positive ATD patients displayed anti-dsDNA and anti-Ro. Interestingly, around 9% of ANA-positive ATD patients in this study met Sjögren's syndrome criteria (Tektonidou 2004).

Elevated level of ANAs was also detected in the pediatric population (n = 104) with autoimmune thyroiditis devoid of rheumatologic diseases. ANA-positive patients have a higher incidence of thyroid antibodies anti-thyroglobulin (ATG) and anti-thyroperoxidase (ATPO) associated with chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis, which was also demonstrated. Thus, in children with detected ANAs and thyroiditis, routine evaluation of ATG, ATPO levels, and thyroid (Kumar 2007; Torok and Arkachaisri 2010).

PA, a severe form of anemia primarily affecting older adults, stems from impaired vitamin B12 absorption in the stomach. This condition is part of a cluster of autoimmune disorders known as polyglandular autoimmune syndrome (PAS) (Ramirez De Oleo et al. 2017). Diagnosing PA involves detecting intrinsic factor gastric parietal cell antibodies or both. Patients with PA exhibit higher frequencies of HLA-A24, -A31, -B8, -B51, -B62, -DR3, and -DR4, which may predispose to rheumatic diseases. However, ANAs and endomysium antibodies are detected in 16.1% of patients with PA, but their frequency does not differ from that of healthy subjects (Morawiec-Szymonik et al. 2019).

AD is predominantly of autoimmune origin, frequently occurring within the context of PAS-2, often accompanied by ATD and/or DMt1. Around 11% of AD patients may also exhibit concurrent autoimmune conditions, including premature ovarian failure, gastritis, vitiligo, alopecia, hepatitis, hypophysitis, and CD (Betterle et al. 2019). AD can co-exist with autoimmune CTDs like SLE (Godswill and Odigie 2014). The presence of ANAs is also reported in AD patients in many case reports. ANAs with a positive 1:320 titer and anti-double stranded DNA antibodies are reported in an 18-year-old female with SLE symptoms and adrenal insufficiency (Abdullah et al. 2006) and a 44-year-old patient with photodermatosis, nephropathy, pancytopenia, and adrenal failure (Da Costa et al. 1992), as well as a 34-year-old female with adrenal insufficiency and antiphospholipid syndrome (Yazdi et al. 2021).

The production of ANA is intricately linked to the activation of B cells, a central component of the immune response, particularly in the context of chronic infections. During this process, microorganisms can trigger polyclonal activation to bypass the host-specific immune response by stimulating various B cell clones. As a result, the synthesized antibodies that are not specifically targeted against the microorganisms allow the pathogens to evade a focused immune attack (Montes et al. 2007). The sustained immune response to chronic infections thus plays a crucial role in the aberrant production of ANAs, highlighting the complex interplay between infection and autoimmunity.

The hepatitis B virus (HBV) is often described in the literature due to the possibility of iatrogenic infection. The infection is transmitted mainly through contact with contaminated blood and semen of infected people (Trépo et al. 2014). Due to the diversity of synthesized antigens such as HBs, HBe, and HBc, HBV stimulates the immune response, synthesizing appropriate antibodies, which serologic conversion is observed in active infection. Unfortunately, in some cases, HBV can evade the immune response, leading to chronic hepatitis caused by long-term infection of liver cells (Woodland 2014).

In the case of HBV, the same antigens that influence the synthesis of immune antibodies (anti-Hbs, anti-HBc, anti-HBe) may also trigger the synthesis of ANA (Table 3). Increased ANA synthesis is mainly observed in idiopathic chronic active hepatitis (CAH), PBC, and alcoholic liver disease (ALD). Their presence is found in approximately 78% of patients with CAH, and in which dominant anti-SS-B antibodies (39% of respondents), anti-single-stranded DNA (anti-ssDNA), and anti-synthetic RNA (poly-A) (Kurki et al. 1984). ANAs are also detected in 17% of patients with histologically confirmed chronic hepatitis B (CHB), characterized by mixed (homogeneous and nucleolar) and cytoplasmic antibodies against the Golgi. No other antibodies, such as AMA, anti-smooth muscle antibodies (ASMA), and liver/kidney microsomal antibodies, are synthesized in this type of hepatitis. These findings suggest a potential tendency toward autoimmunity in newly diagnosed (yet untreated) CHB patients (Şener et al. 2018). However, further research is necessary to understand the underlying mechanisms of immune stimulation and their potential influence on the course of viral infections.

Characteristics of ANAs antibodies in infectious and non-infectious diseases

| ANAs antibodies in infectious diseases | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease | Number of patients | Number of ANAs (+) patients/clinical characteristics | Method of ANAs measurement | Reference |

| Hepatitis C |

|

| IIF | de Castro et al. (2022) |

| N = 48 |

| IIF | Pisetsky (2011) | |

| TB |

|

| ELISA | Shen et al. (2013) |

| n = 1 (case report) |

| IIF | Win et al. (2003) | |

| Parasitic infection | n = 613 |

| ELISA | Mutapi et al. (2011) |

| n = 125 |

| IFAT | Wang et al. (2018) | |

| ANA in non-infectious diseases | ||||

| Diseases | Number of patients | ANA-characteristics | Method | Reference |

| ALD | n = 90 | 63.8% (44 out of 69) | IIF | Lian et al. (2013) |

| n = 47 |

| Quantafluor fluorescent autoantibody test kit. | Laskin et al. (1990) | |

| NHL |

|

| IIF | Altintas et al. (2008) |

|

| IIF—Hep2 cells | Guyomard et al. (2003) | |

| Leukemia | n = 196 |

| IIF | Wang et al. (2021) |

| n = 216 |

| IIFT | Sun et al. (2019) | |

| ANAs in autoimmune cutaneous diseases | ||||

| EPF |

|

| IIF | Nisihara et al. (2003) |

| PV |

|

| IIF | Saleh et al. (2017) |

| LP | n = 47 |

| IIF on Rat esophagus, Monkey esophagus, Hep-2 cells, and rat liver | Carrizosa et al. (1997) |

| n = 100 |

| IIF | Rambhia et al. (2018) | |

| Rosacea | n = 101-ANAs with titre 1:160 |

| IIF on Hep-2 | Woźniacka et al. (2013) |

AID, autoimmune liver disease; ALD, alcoholic liver disease; ANA, antinuclear antibody; anti-dsDNA, anti-double-stranded DNA; anti-ssDNA, anti-single-stranded DNA; CAH, chronic active hepatitis; ELISA, enzyme linked immunosorbent assay; EPF, endemic pemphigus foliaceous; Hep-2, human epithelial type 2; IFAT, indirect fluorescent antibody test, IIF, indirect immunofluorescence; LP, lichen planus; NHL, non-Hodgkin Lymphoma; OS, overall survival; PV, pemphigus vulgaris; TB, tuberculosis.

Chronic hepatitis resulting from the hepatitis C virus (HCV) is frequently associated with the presence of non-organ-specific autoantibodies (Muratori et al. 2003). The prevalence of these antibodies extends to over 50% of the infected population. Serum non-organ-specific ASMA and ANAs are identified in approximately one-third of cases (Cassani et al. 1997). However, there is insufficient data to fully describe their pathogenicity and the influence on the prognosis and lifespan of infected patients (Muratori et al. 2003).

In a study by de Castro et al. (2022), 89 individuals with chronic HCV were examined for ANAs presence using the IIF method. The results indicated that 18 patients (20.2%) were ANAs positive, compared to 2% ANAs positive control (P < 0.0001) (de Castro et al. 2022). Another study showed that 11 individuals (23%) of the 48 with HCV infection (confirmed HCV RNA and anti-HCV antibody levels) exhibited ANA presence. The prevailing ANA expression pattern observed during HCV infection was a speckled pattern. (Peng et al. 2001). In individuals with chronic hepatitis C (CHC), ANA's seropositivity correlates with clinical features such as advanced fibrosis, reduced serum HCV RNA levels, and older age (Hsieh et al. 2007).

Mycobacterium tuberculosis deploys various virulence factors that impede alveolar macrophages—the immune cells tasked with clearing infections. For example, a high mycolic acid content in the bacterial capsule renders it challenging for macrophages to engulf the bacteria. Furthermore, the bacterial cell wall components, such as the cord factor, can directly damage alveolar macrophages (Koch and Mizrahi 2018). Research has shown that M. tuberculosis disrupts the formation of effective phagolysosomes, which are crucial structures for eliminating the bacteria. This mechanism allows the infection to evade detection by the immune system and survive within the host. An individual's immune condition, genetic predisposition, and earlier exposure to the pathogen can all impact the body's ability to contain or eradicate the infection (Koch and Mizrahi 2018).

Persistent chronically active infection may affect ANA synthesis. In patients with TB many types of antibodies are synthesized, which are directed, among others against anti-Ro (SAA), anti-La (SSB), anti-centromere protein, anti-dsDNA, anti-topoisomerase I (anti-Scl-70), anti-Smith protein, anti-ribonucleoprotein III, anti-histone, and histidyl-transfer RNA synthetase (anti-Jo1) (Shen et al. 2013). Similar studies by Shen et al. (2013) confirmed the presence of ANAs (anti-Scl-70 and anti-histone) in 9 of 32 TB patients. Thus, in cases where patients show elevated serum ANA levels without clear signs of autoimmune diseases, mycobacterial origin might be suspected (Shen et al. 2013). A case report of a patient with tuberculous pleural effusion may serve as an example of elevated ANAs IgG (1:1280) levels in pleural fluid and with a characteristic speckled pattern and pleural fluid-to-serum ANAs ratio exceeded 1 (Win et al. 2003).

Parasitic protozoans and helminths possess unique glycans and glycan-binding proteins (GBPs), triggering host immune responses. Chronic helminth infections shift the immune response toward T helper 2 synthesis, characterized by IgE production and activation of regulatory responses (Zandman-Goddard and Shoenfeld 2009). Epidemiological studies suggest that economically developed countries experience higher rates of allergies, including eczema, allergic rhinitis, and asthma, compared to developing nations. This pattern aligns with the hygiene hypothesis, proposing that the elevated living standards in developed nations reduce childhood illnesses but contribute to immunological dysregulation, thereby increasing the risk of allergic diseases. Multiple studies highlight a lower susceptibility to allergies, particularly in children infected with Schistosoma haematobium and Schistosoma mansoni (Strachan 1989; McSorley and Maizels 2012).

Clinical signs in schistosomatosis are caused by immune reactions to schistosome eggs trapped in host tissues. Besides, ANA are synthesized. Interestingly, in parasitic infection, ANA levels are attenuated in helminth-infected humans, and anti-helminthic treatment can significantly increase ANA levels. Such a relationship was observed by Mutapi et al. (2011), who showed an inverse association of ANA levels with the infection intensity of S. haematobium in 613 Zimbabweans independently of host age, sex, and HIV status. Furthermore, ANA levels increased significantly 6 months after anti-helminthic (praziquantel) treatment (Mutapi et al. 2011).

ANAs are also synthesized in Schistosomiasis japonicum infection (24% of 203 individuals). ANAs detection is more prevalent in the advanced stages of the parasitic infection. Advanced schistosomiasis patients usually exhibit a speckled pattern of ANA, suggesting potential autoimmune implications driven by Th17 cells. The incidence of ANAs in patients with schistosomiasis ranges from 6.7% in acute to 23.3% chronic and 70.0% in late stages of infection (Wang et al. 2018). The presence of auto-reactive antibodies is an important sign of autoimmunity. ANAs also prevent inflammation by facilitating the clearance of various waste products, such as oxidized lipids, proteins, and apoptotic cells (Lleo et al. 2010).

In conclusion, parasitic infections' interaction with host immune responses highlights intricate dynamics. The schistosome infection-ANAs connection underscores the complicated balance between infection and autoimmune response. These findings contribute to understanding immune modulation mechanisms and call for screening individuals with Schistosoma infections for potential autoimmune pathologies.

The clinical-histologic spectrum of ALD encompasses such conditions as alcoholic hepatitis, fatty liver, and cirrhosis (Singal et al. 2018). The development of ALD stems from three principal factors: (1) liver injury due to ethanol, (2) an ensuing immune response causing inflammation, and (3) modifications in intestinal permeability and the microbiome composition (Dunn and Shah 2016). Nevertheless, data on early-stage diseases are limited, and most patients are diagnosed in advanced stages (Singal et al. 2018).

The most prevalent ANA antibodies in liver diseases are AMA and ASMA. These antibodies are present in nearly 70% of patients with ALD, ALD overlapping with CHB, or CAH (Laskin et al. 1990; Lian et al. 2013). The level of ANAs increases if cirrhosis develops. ALD patients have a greater autoantibody incidence than CHB patients alone (69.6% vs. 37.5%, P 0.01). Moreover, 10.4% of ALD patients with positive autoantibodies exhibit systemic autoimmune or vascular diseases, and such a relation is not observed in CHB patients (Lian et al. 2013). The detailed analysis of the ANAs profile shows that nearly 60% of ALD or CAH patients have either anti-ssDNA or anti-dsDNA antibodies. These findings suggest a potential autoimmune background in individuals with ALD (Laskin et al. 1990).

Non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs) are a group of malignancies that arise from the lymphoid system. NHLs develop through an array of genetic modifications that give the malignant clone an edge in growth. Recurrent translocations are frequently the first step in B-cell differentiation, leading to aberrant expression of oncogenes that affect cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation (Nogai et al. 2011). NHL can develop in autoimmune diseases, particularly in the case of Sjogren syndrome.

Hodgkin's lymphoma is characterized by the presence of Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg (HRS) cells responsible for malignancy. Studies have provided evidence that, in most cases, HRS cells originate from a specific subset of germinal center B cells (Küppers et al. 2005).

ANAs are detected in 19% of patients with NHL, and their occurrence signifies a distinct biological anomaly, and its detection often precedes the formal diagnosis of NHL (Tiplady et al. 2000). ANAs in NHL are mainly directed against mitotic proteins (Guyomard et al. 2003). However, most patients with lymphoma and ANA-positivity do not develop autoimmune diseases, hence rejecting the correlation between ANAs and autoimmune diseases (Altintas et al. 2008).

ANAs have been increasingly linked to various cancers, though the specific implications of different ANA patterns in cancer, particularly leukemia, remain unclear.

A retrospective study explored the relationship between ANA patterns and leukemia outcomes. Since ANA results in this study were analyzed at least 2 months after treatment in the patients with leukemia. Therefore, the ANAs assessed in this study were therapy-induced ANAs. Among 196 leukemia patients sampled, 34% were ANA positive, of which 63% demonstrated a nucleolar pattern, and 37% demonstrated non-nucleolar patterns. Those with a nucleolar ANA pattern exhibited a two-fold higher mortality risk than patients with negative ANA, independent of factors such as sex, age, leukemia immunophenotype, cytogenetic abnormalities, treatment, and blood transfusion. The association was notably stronger in older patients (≥60 years) and those undergoing treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitors or chemotherapy (P for interaction = 0.042 and 0.010, respectively). Importantly, patients with a nucleolar ANA pattern demonstrated significantly shorter survival than those with non-nucleolar patterns or negative ANA (P < 0.001), making it a significant predictor of poor diagnosis (Wang et al. 2021).

Another study evaluated the role of ANAs as a prognostic factor in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Out of 216 patients, results reported that ANAs were abnormal in 13.9% of cases and, along with TP53 disruption, served as independent prognostic indicators for overall survival (OS). TP53 is the most commonly mutated gene in human cancers. The combination of positive ANAs and TP53 disruption yielded a higher predictive accuracy for OS (AUC: 0.766) compared to TP53 disruption alone (AUC: 0.706) or positive ANAs alone (AUC: 0.595). Moreover, incorporating positive ANAs into the CLL-international prognostic index improved its predictive power for OS in CLL patients. (Sun et al. 2019).

Lichen planus (LP) is a chronic inflammatory condition affecting the skin, mucous membranes, and appendages. A distinctive feature of LP is the accumulation of inflammatory T cells in the dermis, forming a characteristic band-like pattern (Solimani et al. 2021). ANAs are detected in 40.42% of LP patients (n = 47), with higher titers in erosive LP (Carrizosa et al. 1997). In the Indian population, 22% of LP patients showed positivity for ANAs (Rambhia et al. 2018). These studies shed light on autoantibody synthesis in various LP subtypes, suggesting complex interactions between immune responses and disease pathogenesis.

Rosacea, a chronic inflammatory dermatosis that primarily affects women in their third and fourth decades of life, is characterized by recurrent flushing, chronic erythema, phymatous changes, papules, pustules, and telangiectasia (van Zuuren et al. 2021). Over half (53.5%) of the rosacea patients exhibit ANA titers ≥1:160, with 13.86% at 1:320, 8.91% at 1:640, and 6.93% at 1:1280 or higher. The specific nature of these antibodies remains undetermined. Increased ANA titers in rosacea patients and facial erythema and photosensitivity could lead to a misdiagnosis of lupus erythematosus. Notably, higher ANA titers are more common in women (55.8%) than in men (44.15%) (Woźniacka et al. 2013).

Pemphigus vulgaris (PV) is an autoimmune blistering disorder driven by autoantibodies against desmogleins, key adhesion molecules in desmosomes. This type 2 hypersensitivity reaction disrupts keratinocyte–keratinocyte adhesion, leading to acantholysis and blister formation (Ingold et al. 2024). The specific targeting of desmoglein 1 and desmoglein 3 explains the pattern of blistering observed in PV, which is linked to the tissue-specific expression of these desmoglein isoforms. Research on T and B cells in mouse models and patients has clarified the autoimmune mechanisms. This review will examine the role of ANAs in PV, focusing on their impact on disease pathology and clinical features (Kasperkiewicz et al. 2017).

The study of Nisihara et al. (2003) analyzed a broad spectrum of autoantibodies in patients with endemic pemphigus foliaceous (EPF; n = 120). It showed that ANA was detected in three EPF patients (2.5%). One of these patients had ANA in a scattered pattern, with a titer of 1:320, and showed positivity for the anti-SSA (Ro) antibody; the other two patients showed a cytoplasmic pattern, both with a titer of 1:40. Since ANA was detected in comparable amounts in EPF and control group, it seems that EPF is an organ-specific autoimmune disease (Nisihara et al. 2003). In contrast, another study found a prevalence of ANAs in 40% of Tunisian and Brazilian patients with PV compared with only 2% (1 person) in a control group. Of these patients, 9 patients were previously untreated and 11 were undergoing treatment with systemic steroids and azathioprine. ANA patterns observed included a homogenous pattern in 10 patients, a speckled pattern in 9 patients, and a mixed speckled and homogenous pattern in 1 patient (Saleh et al. 2017).

Since pemphigus and CTD are B-cell-driven diseases, some studies analyzed whether they are significantly associated. For example, the study of Kridin et al. (2019) analyzed the co-existence of pemphigus and SLE. The prevalence of SLE was slightly higher among patients with pemphigus compared to controls (OR: 1.85; 95% CI: 0.89–3.82). The sensitivity analysis showed that the association between pemphigus-treated patients and SLE had been substantiated and was statistically significant (OR: 2.10; 95% CI: 1.00–4.48) (Kridin et al. 2019). Moreover, serological tests show that almost a third of patients with pemphigus have the presence of non-organ-specific autoantibodies, including ANA. The indirect immunofluorescence studies show that the most frequently recognized ANA fluorescent pattern among patients with pemphigus was a homogeneous pattern typical for SLE (Blondin et al. 2009). Furthermore, the molecular pathways between pemphigus and SLE showed many similarities. For example, IRF8 and STAT1 genes are essential regulatory genes in both diseases (Sezin et al. 2018).

ANAs are commonly detected in both healthy individuals and patients with a wide range of non-rheumatic diseases, including those with autoimmune and infectious origins. However, elevated ANA titers generally do not indicate subclinical systemic autoimmune disease. Instead, they are more likely to reflect underlying immune dysregulation in conditions such as PBC, AD, psoriasis, and autoimmune thyroid disease. For instance, over one-third of patients with DMt1 and autoimmune hepatitis, exhibit increased ANA levels, with a higher prevalence observed among females.

ANA plays a significant role in PBC, particularly in AMA-negative patients. Thus, specific ANA patterns, such as the multiple nuclear dots and nuclear membrane (rim) patterns, are crucial in identifying PBC when AMA is absent and are often associated with antibodies against Sp100, p62, and gp210. Additionally, ACA are found in a subset of PBC patients and are linked with more severe disease outcomes, including increased bile duct damage and a higher risk of portal hypertension. The presence of ACA is particularly notable in patients with overlapping PBC and SSc, highlighting the complex autoimmune interactions in these patients. Understanding the role of ANA and ACA in PBC is essential for refining diagnostic accuracy and enhancing treatment approaches.

In non-celiac wheat sensitivity and CD, patients demonstrate higher rates of ANA positivity and autoimmune disorders compared to those with IBS. The variability in findings across studies may stem from the frequent coexistence of autoimmune diseases in CD, which is often associated with conditions like DMt1, Sjögren's syndrome, and autoimmune thyroid disorders. This association underscores the potential utility of ANA testing in identifying individuals at risk for developing additional autoimmune conditions.

ANAs are also detected in non-AIDs, such as CAH, where they are more prevalent than in ALD, especially in advanced stages characterized by cirrhosis. In CHC patients, ANA positivity is a valuable marker for predicting disease activity. Additionally, in patients with NHL, ANA occurrence does not strongly correlate with the development of autoimmune disorders. This suggests that, in the context of NHL, ANAs represent a distinct biological feature rather than a marker for autoimmune disease.

Infectious diseases also influence ANA levels. For example, patients with schistosomiasis experience decreased ANA levels during infection, which rise following treatment. Similarly, ANA, particularly anti-Scl-70, is more commonly associated with extrapulmonary TB than other forms of TB. Elevated ANA titers are also observed in one-third of patients with erosive LP, a chronic inflammatory condition affecting the skin, mucous membranes, and appendages. ANA positivity has been reported in 40.42% of patients, especially in erosive subtypes. This suggests a role for autoantibodies in the pathogenesis of LP, although the exact mechanisms remain unclear.

In rosacea, another chronic inflammatory dermatosis, more than half of patients exhibit ANA titers of ≥1:160, with higher titers being more common in women. This finding raises concerns about the potential for misdiagnosis as lupus erythematosus due to overlapping symptoms such as facial erythema and photosensitivity. In some chronic or advanced disorders, ANA levels tend to be higher, and in cancer, particularly leukemia, ANAs have prognostic value. For instance, nucleolar ANA patterns are linked to increased mortality risk and shorter survival, especially in older leukemic patients and those receiving specific treatments like tyrosine kinase inhibitors. In CLL, the presence of ANAs, particularly when combined with TP53 disruption, is an independent predictor of OS, enhancing existing prognostic models.

The presence of ANAs in pemphigus presents a varied picture. EPF exhibits a low prevalence of ANA positivity, similar to control groups. However, PV patients show a significantly higher prevalence of ANA, with common patterns including homogeneous and speckled. This suggests a broader autoimmune activity in PV compared to EPF and hints at a possible connection between pemphigus and SLE, supported by shared molecular pathways involving IRF8 and STAT1.

When screening for autoimmune conditions, it is important to recognize that age plays a significant role in interpreting the presence of autoantibodies. While a positive autoantibody test in young and middle-aged individuals may indicate a predisposition to or an early stage of an autoimmune disease, this is not necessarily the case for older adults. In older men, for example, a positive ANA result is often a non-specific finding that may not provide meaningful diagnostic information. Therefore, age should be carefully considered when evaluating the significance of autoantibody positivity in assessing the risk of autoimmune diseases.

While low-titer ANA positivity is common in healthy individuals, a positive ANA test alone does not indicate an autoimmune disease. Similarly, in most non-rheumatic diseases, elevated ANA titers are not typically linked to the development of systemic autoimmune diseases. However, close monitoring is recommended in cases of high ANA titers, as CTD may develop. Despite this, long-term observational studies are lacking to conclusively demonstrate a link between ANA positivity in non-rheumatic diseases and the future development of specific CTDs.