Traditional drug delivery systems (DDSs) often require high doses and frequent administration, which can lead to unwanted drug exposure and potential toxicity in tissues and organs. To address these issues, innovative systems like hydrogels are emerging as promising tools for delivering medication in a more targeted and controlled manner (Mahmood et al., 2022; Słota et al., 2024). Hydrogels are network structures which are formed due to crosslinking of polymeric chains leading to formation of the free volume into which the absorbed water is filled and swelling occurs without disturbing the structure (Mali et al., 2018). They do not get solubilized in aqueous solvents because of the physical or chemical crosslinks which are insoluble (Ghorpade et al., 2016). Due to properties such as high swelling, simplified process, and comparatively less manufacturing energy requirements, hydrogels have greater use in biomedical field (Ahmed et al., 2025; Sepe et al., 2025). Due to its porous structure, hydrogel serves as an efficient DDS by loading or incorporating therapeutic agents within its matrix (Mali et al., 2017a). The unique structural properties and viscoelastic nature of hydrogels closely mimic the characteristics of the cell membrane, making them highly suitable for biomedical applications, including tissue engineering and targeted drug delivery (Mali et al., 2023).

Nowadays, chemically modified natural polymers have gained a lot of attention as they provide enhanced stability and properties. Carboxymethyl tamarind gum (CMTG) is a cheap, semi-synthetic, anionic polymer which is obtained by carboxymethylation of the tamarind gum (Mali et al., 2023). Carboxymethylation of tamarind gum enhances its cell proliferative property and viscosity and offers an improved resistance to microbial degradation (Yadav et al., 2017). CMTG has enhanced shelf life, mucoadhesivity, in situ gelation, high drug loading capacity, hydrophilicity, stability, broad pH tolerance, and release kinetics. CMTG also shows antibacterial properties (Khushbu and Warkar, 2020). CMTG has good bioadhesive properties as well as good film-forming ability, which makes it a good candidate for its application in the preparation of hydrogel (Mali et al., 2019). Alone crosslinked CMTG films showed poor matrix integrity. So, to enhance the film stability, there is a need to use another biopolymer in combination with CMTG, which will help in enhancing the matrix integrity and swelling (Mali et al., 2023).

Despite numerous advances, there is a lack of systematic research exploring the use of natural mucilages, such as flaxseed mucilage (FSM), in the development of hydrogel films. FSM is extracted from the seeds of Linum usitatissimum L. For improving oil production and quality, the FSM is extracted as a by-product at the industrial level. The FSM is also extracted from the pulp which is considered as a biowaste that remains after the extraction of flaxseed oil (de Paiva et al., 2021). FSM is primarily found in the outermost layer of the hull. Approximately 3 %–9 % of mucilage is present in a seed (Bekhit et al., 2018). The fiber-rich hull readily releases mucilaginous substances when soaked in water. Upon hydration, the mucilage cells expand, allowing their contents to seep onto the seed's surface (Beikzadeh et al., 2020). FSM is a heterogeneous, hydrophilic polysaccharide composed of two components: arabinoxylan (75 %), which is neutral in nature, and rhamnogalacturonan (acidic) (Safdar et al., 2019). The neutral fraction contains d-galactose, l-arabinose, and d-xylose in a molar ratio of 1:3.5:6.2, whereas l-fucose, l-rhamnose, and d-galacturonic acid are the components of acidic fraction in a molar ratio of 1.4:2.6:1.7. FSM has properties such as thickening, swelling, and adhesiveness, and therefore, it has several applications in pharmaceutical formulations (Haseeb et al., 2016). Such a polysaccharide which occurs naturally possesses remarkable properties such as hydrophilicity, biodegradability, and biocompatibility. These unique characteristics position polysaccharides as promising biomaterials for DDSs, enhancing their potential in pharmaceutical applications. Due to such properties of FSM, it is used as a gelling agent (Jia et al., 2022), a mucoadhesive agent (Haseeb et al., 2024), a foaming agent (Kaewmanee et al., 2014), and a film-forming agent (Beikzadeh et al., 2020; de Paiva et al., 2021; Karami et al., 2019; Tee et al., 2016). Beyond medical applications, FSM is also employed as a food additive, enhancing taste and texture, and is incorporated into functional foods, dairy products, and food packaging materials (Safdar et al., 2019).

The chemical crosslinked hydrogels are strong and durable, but the drawback is that the chemical agents used as crosslinkers are reported to be toxic, cytotoxic, and erosive (Mali et al., 2018). Recently, citric acid (CA) emerged as a nontoxic, cost-friendly, and green crosslinker (Pargaonkar et al., 2023; Salihu et al., 2021). At high temperatures, CA is transformed into cyclic anhydride, which esterifies the hydroxyl groups on nearby polymer chains, resulting in formation of crosslinks. As it provides a greater number of sites for crosslinking, it aids in increasing the mechanical strength of hydrogel films (Mali et al., 2017a). In literature, CMTG hydrogel films exhibited low matrix integrity as well as less swelling; so, it is hypothesized that addition of FSM will enhance the matrix integrity by increasing the entanglement of FSM polymer chains. While, due to the hydrophilic nature of the FSM, will also enhance the swelling of the hydrogel films. However, till today, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that evaluates the synergistic effects of FSM combination with CMTG for enhancing matrix integrity and swelling response of CA-crosslinked CMTG hydrogel films. This novel combination provides a sustainable route to develop hydrogel films using biowaste-derived polymers aligns with sustainable material innovation and may offer ecofriendly alternatives for wound dressing.

This study aims to develop and characterize composite hydrogel films by incorporating FSM into the CMTG matrix to improve film integrity and swelling behavior. The films were synthesized via a solvent casting method and were evaluated for weight loss, thickness, total carboxyl content (TCC), contact angle, water vapor permeability, microbial permeability, protein adsorption, and hemocompatibility. Metronidazole (MTZ) was selected as the model drug, and drug loading and release of the hydrogel films were evaluated.

CMTG with a degree of substitution of 0.2 was kindly gifted by Chhaya Industries (Barshi, India). A gift sample of MTZ was obtained from JB Chemicals and Pharmaceuticals (Gujarat, India). Flaxseeds were purchased from the local market (authenticated by Dr. Shankar M. Shendage, Department of Botany, Balwant College, Sangli, India; identified as Linum usitatissimum L., family Linaceae). CA anhydrous, isopropyl alcohol, and acetone were procured from Loba Chemie (Mumbai, India). All the additional chemicals were of analytical grade.

Initially, before starting the extraction process, high-quality flaxseeds were selected and washed thoroughly, so that the impurities were removed. Later on, these (200 g) flaxseeds were soaked in distilled water in 1:5 (% w/v) ratio for 24 h. After completion of soaking, the mixture was heated at 80 °C–90 °C for 1 h with constant stirring to let the mucilage get leached out from the hull into the aqueous phase. This mixture was then taken into bags prepared by using cotton cloth/muslin cloth. The bags were squeezed to separate the mucilage from seeds. The separated mucilage was isolated by treating it with 95 % ethanol in 1:2 ratio to precipitate the mucilage, and the excess water was removed by using acetone. For defatting the mucilage, the isolated mucilage was treated with n-hexane.

Then the mucilage was dried, finely grounded, and stored in a proper place (Mohanta et al., 2023; Puligundla and Lim, 2022; Safdar et al., 2019). Phytochemical screening of the extracted mucilage was conducted to detect the presence of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats.

CMTG–FSM composite hydrogel films were prepared by using a previously reported method with slight modifications (Salunkhe et al., 2025). In brief, dry CMTG and FSM powders were taken in the desired ratios and dissolved in distilled water, followed by continuous stirring for 1 h using a mechanical stirrer (Remi, India) at room temperature. Then, CA as a crosslinker was added in different concentrations to the above solution and stirred for another 1 h using mechanical stirrer. The solution was kept overnight to remove entrapped air bubbles. Then the solution was poured into uniform sized Petri plates and kept for drying at 50 °C for 24 h in a hot air oven. The dried films were cured at 140 °C for 10 min to achieve the required crosslinking. Later, the films were washed with distilled water for 45 min followed by isopropyl alcohol and acetone to remove entrapped water. Residual solvents were removed by drying the films in a vacuum oven at 40 °C for 24 h and stored in desiccator until further use. The composition of hydrogel batches is given in Table 1.

Composition of CMTG:FSM composite hydrogel films

| Batch | HM1 | HM2 | HM3 | HM4 | HM5 | HM6 | HM7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMTG:FSM ratio (2 % w/v) | 1:0 | 9:1 | 9:1 | 9:1 | 8:2 | 7:3 | 1:1 |

| Citric acid (% w/v) | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

CMTG: carboxymethyl tamarind gum, FSM: flaxseed mucilage

The percent weight loss of hydrogel film was determined by calculating the percent practical yield of hydrogel films. The thickness of the prepared hydrogel films was measured by using a micrometer screw gauge. The thickness of the film was measured at six random points, and the average thickness was calculated.

TCC of hydrogel films was determined by acid–base titration (Mali et al., 2017), which quantifies residual carboxyl groups. Before analysis, the films were thoroughly washed with water, isopropyl alcohol, and acetone to remove unreacted CA. Approximately 100 mg of film was dispersed in 20 mL of CO2-free 0.1 N NaOH and stirred for 2 h. The excess alkali was then back-titrated with CO2-free 0.1 N HCl using phenolphthalein as the indicator. Thus, the measured values primarily reflect CA covalently incorporated into the crosslinked network, with any free molecules minimized by the washing process. TCC of the hydrogel films was calculated using the following equation:

The wetting property of hydrogels was determined by a manual water contact angle technique. With the help of micro-liter pipette, 10 μL of distilled water was dropped on the surface of the hydrogel film. A digital camera (Canon EOS 1500D, Haryana, India) was used to capture the image of the drop within 5 s. The analyses of the image were done by using ImageJ software, and the contact angle between the surface and the drop was measured. All the readings were recorded in triplicate and reported as the mean value of each hydrogel.

The desiccant method was used to evaluate the prepared hydrogel films for the water vapor transmission rate (WVTR). These hydrogel films were cut into circular pieces with 1 cm diameter and were fixed on the mouth of vials with 1 cm diameter containing anhydrous CaCl2. The CaCl2 was filled in such a way that the lower side of the fixed film and CaCl2 had a gap of 10 mm between them. For comparison, a reference vial was also prepared without films. Then these vials were placed in a desiccator containing saturated solution of NaCl. At specific time intervals including 0, 6, 24, 36, 48, and 72 h, the vials were weighed on an analytical balance. The weight gain (ΔW) of the vials was recorded over the period. For calculating WVTR through the hydrogel films, the following formula was used:

The prepared hydrogel films were evaluated for microbial permeability by using microbial permeability test. In this test, onto the 10-mL vials, the round hydrogel films containing 5 mL nutrient broth were fixed. As a comparison, negative and positive controls were prepared. In case of negative control, a vial having 5 mL nutrient broth was sealed with a sterilized cotton ball to prevent microbial entry from the environment, whereas for positive control, the vial containing 5 mL nutrient broth was left open to the environment, allowing entry and microbial contamination. Incubate all the vials including both the controls for a period of 1 week. After the incubation period, the vials were observed for any cloudiness or turbidity in the nutrient broth, which would indicate microbial contamination.

To determine the amount of protein absorbed on the hydrogel film, Lowry method was used with a slight modification. The prepared hydrogel films (1 × 1 cm) were immersed in Tris HCl buffer pH 7.4 containing 200 μg/mL bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 6 h under 100 rpm with constant stirring at 37 °C. When stirring was completed, the films were taken out and rinsed with Tris HCl buffer pH 7.4 for five times. Then, they were placed in 5 mL of aqueous solution of sodium dodecyl sulfate (1 % w/v) and shaken in an orbital shaker at 100 rpm for 1 h at 37 °C to remove the protein absorbed on surface of the hydrogel films. Later, UV spectrophotometric estimation was done at 660 nm by doing proper dilutions (Mali et al., 2023).

Hemolysis assay was performed to determine hemocompatibility of the prepared hydrogel films. The hydrogel films were cut to get a surface area of 2 cm2. These films were allowed to swell in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) maintained at 37 °C for 1 h. Then, the PBS was removed and 0.5 mL of goat citrate-phosphate-dextrose (CPD) blood was added over the films. By adding 4 mL of 0.9 % NaCl, the hemolysis process was stopped after 20 min. This was followed by incubation of the sample for 1 h at 37 °C. The incubated samples were centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 10 min, and the supernatant was subjected to spectrophotometric analysis at 545 nm (Alexandre et al., 2014; Mali et al., 2017a). Hemolysis (%) was determined using the following formula:

To determine the swelling index of the prepared hydrogel films, they were allowed to swell in various media such as Tris HCl buffer pH 7.4 and 0.1 N HCl. Hydrogel films of 1 × 1 cm were used. Initially, the weight of dry films was recorded, followed by immersing them in various media. Later on, weight of the swollen hydrogel films was recorded at definite time intervals. Then, by using the following formula, the swelling index was calculated:

Approximately 500 mg of hydrogel fwas weighed and allowed to swell in 20 mL Tris HCL buffer pH 7.4 solution containing MTZ (5 mg/mL) for 6 h. Then the swollen hydrogel films were dried in a hot air oven at 40 °C for 24 h.

Small pieces of hydrogel films weighing 50 mg were allowed to immerse in 20 mL of 0.1 N NaOH. The dispersion was stirred using a magnetic stirrer at 100 rpm for 1 h, so that the films broke and solubilized. The solution was filtered to remove the particles of hydrogel films. The amount of MTZ loaded onto the hydrogel film was determined spectrophotometrically at a wavelength of 320 nm.

For conducting drug release study, the prepared hydrogel films loaded with MTZ (about 50 mg in weight) were placed into a 10 mL solution of Tris HCl buffer pH 7.4 that was kept at 37 °C. Samples were withdrawn at predetermined time intervals and replaced with fresh dissolution medium to ensure the sink condition was maintained. The amount of MTZ released was determined spectrophotometrically using a spectrophotometer at 320 nm. To ensure accuracy and reliability of the results, the experiments were performed in triplicate.

The release data were fitted to zero-order, first-order, Higuchi, and Korsmeyer–Peppas models, and the best-fit model was identified based on the coefficient of determination (R2) (Costa and Sousa Lobo, 2001). For the Korsmeyer–Peppas model, release data up to 60 % of the total drug released were considered, and data fitting was performed using the following equation:

The infrared spectrum of FSM, CMTG, CA, and composite hydrogel films was obtained by using attenuated total reflectance–Fourier transform infrared (ATR–FTIR) spectrophotometer (Alpha ll, Bruker, Japan). The sample to be analyzed was placed onto ATR, and spectra were recorded in the range of 500–4000 cm−1 at an average of 25 scans and resolution of 4 cm−1 (Mahmood et al., 2022).

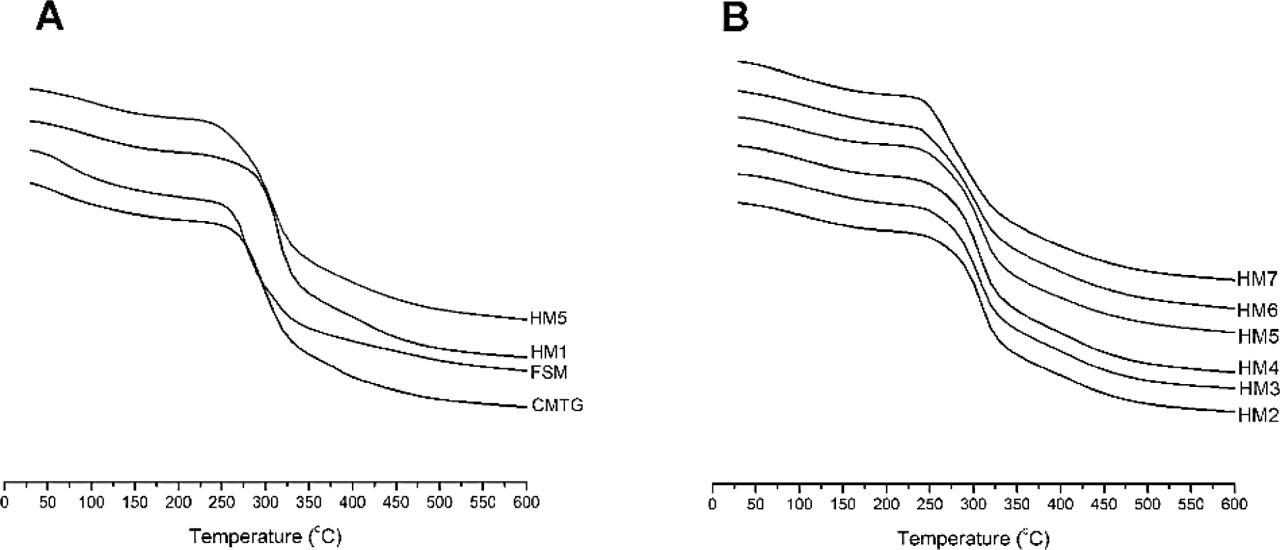

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) of FSM, CMTG, CA, and composite hydrogel films was performed using Mettler-Toledo TGA/DSC1 thermogravimetric analyzer. The samples were heated from 30 °C to 600 °C at the rate of 10 °C/min under nitrogen atmosphere (flow rate: 50 mL/min) (Mahmood et al., 2022).

The mucilage was successfully extracted from flaxseeds by using hot water extraction process. The yield of FSM was found to be 9 % w/w and was higher than the yield obtained by de Paiva et al. (2020). The extracted FSM appeared to be brownish in color due to the high levels of phenolic compounds in brown flaxseeds. High temperature and prolonged heating may result in browning of mucilage. Browning of extract might be also due to degradation of polysaccharide and proteins present in it (Barbary et al., 2009). The extracted FSM was found to be odorless and tasteless, whereas it was found to be water soluble. In addition, it was soluble in hot as well as cold water, making it a potential polysaccharide to be used in various industries including food and pharmaceuticals (Mohanta et al., 2023). The extracted mucilage was free from proteins, amino acids, and fats.

At the beginning, the primary aim was to optimize the concentration of the polymers to get a proper and optimal hydrogel film formation. Initially, the concentration of polymers was varied between 1 % and 4 % by maintaining the concentration of the crosslinker constant. However, it was observed that films having polymer concentration between 1 % and 2 % were formed, but in case of hydrogel films having polymer concentration above 2 %, films formed were of very weak strength and brittle. However, at 1 % polymer concentration, the films developed were very thin and not handleable ones. Based on the above findings, 2 % polymer concentration was selected as the optimal one to achieve proper hydrogel film formation.

The next step was to optimize the concentration of crosslinker, that is, CA, in correlation with 2 % polymer concentration. In the preformulation phase, the CA concentration used was 0.4 % w/v, 0.6 % w/v, and 0.8 % w/v. When 0.8 % w/v CA concentration was used, the films formed were hard and showed very low swelling because of increase in the crosslinking density leading to dense structure. At 0.4 % w/v concentration of CA, proper films were formed and they exhibited good swelling. But when exposed to buffer solutions, the films began to erode. So, to overcome the erosion, the concentration of CA was increased to 0.6 % w/v. At 0.6 % w/v, proper film was formed and optimum swelling was observed. In addition, enhancement in stability was obtained for the buffer solution.

Curing temperature and time plays an important role in formation of hydrogel films. In the preformulation phase, curing conditions of 130 °C, 140 °C, and 150 °C (for 5 or 10 min each) were evaluated. Films cured at 140 °C for 10 min demonstrated the best balance of strength, integrity, and swelling capacity, and therefore, this condition was selected as optimal.

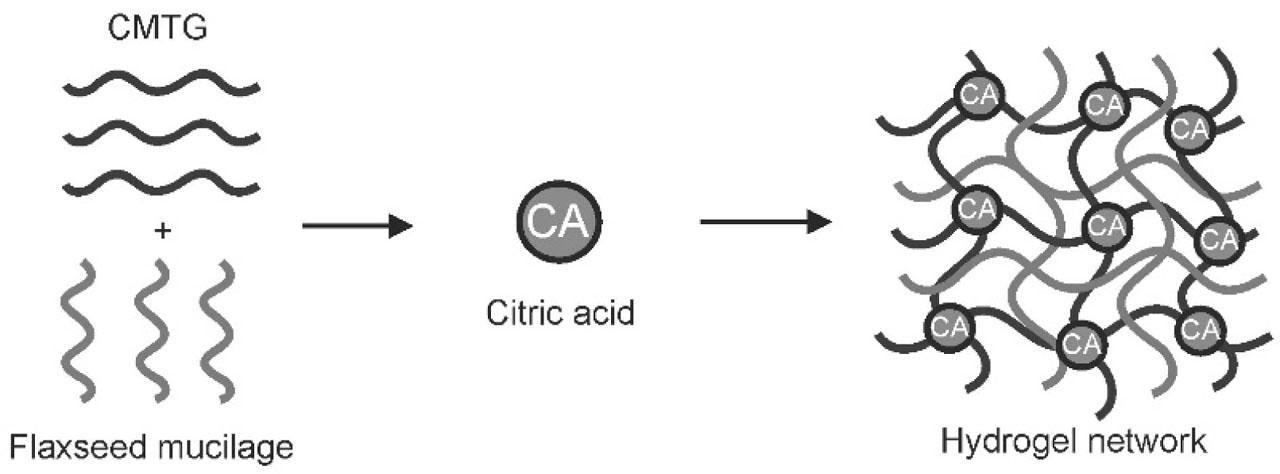

FSM is a natural polysaccharide, and CMTG is a semisynthetic derivative of TG. In literature, previously, CMTG was proven to undergo crosslinking with CA. In the present work, CMTG–FSM composite hydrogel films are developed, in which CMTG gets crosslinked by CA, that is, when CA is heated to a high temperature, it undergoes conversion from CA to its anhydride form. Later, this anhydride form esterifies the hydroxyl (OH) groups present on the CMTG polymer chains (Mali et al., 2017a). However, FSM does not get crosslinked by CA; so, the polymeric chains of FSM get entangled between the matrix structure formed by CMTG and CA crosslinking. This entanglement contributes to overall mechanical integrity of the matrix, even though they are not chemically bonded. That is why it is called as a composite hydrogel film, in which at least one polymer should get crosslinked and the other gets entangled. This is also called as semi-interpenetrating network. Although there may be formation of hydrogen bonding in between FSM-FSM and FSM-CMTG (Mali et al., 2023, 2017a). Figure 1 shows the schematic representation of formation of hydrogel films.

Schematic representation of formation of hydrogel film.

After washing the hydrogel films with water, isopropyl alcohol, and acetone, the percentage weight loss of dried films was calculated and found to be between 29.89 % and 37.21 % (Table 2). In batches HM2 to HM4, weight loss increased with higher concentrations of CA, which may be attributed to the washing of unreacted CA, CMTG, and FSM. In the prepared composite hydrogel films, CMTG undergoes crosslinking with CA, while FSM becomes entangled within the crosslinked CMTG network. The percent weight loss was further influenced by FSM concentration (batches HM5 to HM7), likely due to the removal of entangled FSM chains from the CMTG mesh (Mali et al., 2023, 2017b).

Percent weight loss, thickness, TCC, and contact angle of CMTG–FSM composite hydrogel films.

| Batch | Weight loss (%) | Thickness (μm) | TCC (mEq/100 g) | Contact angle (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HM1 | 30.28 ± 7.93 | 575.00 ± 7.26 | 350.33 ± 6.5 | 63.29 ± 0.47 |

| HM2 | 29.89 ± 5.44 | 593.86 ± 4.79 | 370.67 ± 4.4 | 60.31 ± 0.49 |

| HM3 | 32.33 ± 9.74 | 590.00 ± 4.41 | 407.00 ± 3.2 | 65.92 ± 0.38 |

| HM4 | 34.17 ± 11.84 | 578.33 ± 6.01 | 427.35 ± 6.6 | 69.91 ± 0.39 |

| HM5 | 33.03 ± 6.13 | 587.44 ± 7.43 | 390.33 ± 3.8 | 66.64 ± 0.22 |

| HM6 | 35.15 ± 5.35 | 584.33 ± 6.89 | 331.67 ± 6.2 | 69.85 ± 0.55 |

| HM7 | 37.21 ± 6.60 | 572.22 ± 3.47 | 304.33 ± 5.4 | 74.29 ± 0.18 |

CMTG: carboxymethyl tamarind gum, FSM: flaxseed mucilage, SD: standard deviation, TCC: total carboxyl content Values are expressed as mean ± SD

The thickness of the prepared films ranged from 572.22 to 593.86 μm (Table 2). A trend was observed where films with higher weight loss exhibited reduced thickness, indicating that removal of loosely bound polymer chains decreased the final film thickness (de Paiva et al., 2021; Mali et al., 2023).

The carboxyl content of prepared composite hydrogel films is listed in Table 2. TCC was found between 304.33 ± 5.4 and 427.35 ± 6.6 mEq/100 g. In prepared batches, HM2 to HM4 showed an increase in CA concentration, which led to an increase in TCC. This might be due to increase in the crosslinking density leading to the formation of denser structure. Similarly, the polymer concentration also affects the carboxyl content of hydrogel films. It was found that as the concentration of FSM was increased from batches HM5 to HM7, TCC was decreased. This may be attributed to the fact that FSM does not undergo crosslinking with CA. So, less CA is used to crosslink CMTG and the remaining unreacted CA is washed out. Consequently due to which less number of COOH are available to react with NaOH leading to lowering of the TCC (Mali et al., 2018, 2017b).

Both CMTG and FSM are hydrophilic in nature. Table 2 shows the contact angles of prepared hydrogel films. The contact angle of the hydrogel films was found to be in the range of 60.31°–74.29°. Studies showed that as the concentration of CA was increased, the contact angle increased. This indicates that as CA is increased, the film becomes more hydrophobic in nature; this might be due to increase in the density of crosslinks. Leading in formation of dense structure resisting water to penetrate through surface. FSM concentration also affects the contact angle. An increase in the contact angle of hydrogel films was recorded with increase in FSM concentration, which might be due to increase in the entanglement leading to formation of dense structure, acting as a barrier for water to easily and rapidly spread on the surface (Kanwal et al., 2024; Khan et al., 2021)

Table 3 provides the results of WVTR of composite hydrogel film. The vial kept open, that is, control, showed a WVTR of 2042.61 g/m2. Compared to the control vial, the vial that was closed by mounting hydrogel films showed low WVTR. WVTR was observed to be between 820.18 and 987.96 g/m2. It was noted in the study that as the concentration of CA was increased from batch HM2 to HM4, WVTR decreased. This might be due to increase in crosslinking densities typically resulting in denser structure. This denser structure reduces the movement of water vapor. Similarly, increasing the FSM concentration (batches HM5–HM7) enhanced polymer entanglement, forming a denser network and further reducing WVTR. The observed WVTR results demonstrated that the CMTG–FSM composite hydrogel films effectively regulate moisture levels in the surrounding environment. By maintaining an optimal hydration balance, these films facilitate wound healing and epithelialization, while simultaneously preventing excessive dryness that could hinder tissue recovery (Sadiq et al., 2022).

Water vapor transmission rate, microbial permeability, protein adsorption, and hemolysis of CMTG–FSM composite hydrogel films.

| Batch | WVTR (g/m2) | Microbial permeability | Protein adsorption (mg/cm2) | Hemolysis (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HM1 | 987.96 | −ve | 0.044 | 4.561 |

| HM2 | 941.13 | −ve | 0.034 | 2.474 |

| HM3 | 905.00 | −ve | 0.040 | 3.464 |

| HM4 | 791.40 | −ve | 0.047 | 4.013 |

| HM5 | 887.36 | −ve | 0.035 | 3.813 |

| HM6 | 843.36 | −ve | 0.032 | 3.318 |

| HM7 | 820.18 | −ve | 0.029 | 2.212 |

CMTG: carboxymethyl tamarind gum, FSM: flaxseed mucilage, WVTR: water vapor transmission rate

The prepared composite hydrogel films were evaluated for microbial permeability by mounting them on vials containing nutrient broth for 1 week. At first, on day 0, no microbial growth was observed in all vials, including both positive and negative controls. On the fourth day, evidence of growth was observed in negative and positive controls, but there was no sign of microbial growth in all vials mounted with prepared composite hydrogel films. By the end of the seventh day, full growth was recorded in both negative and positive controls, but there were no signs of microbial growth in vials covered by composite hydrogel films. Results showed that CMTG–FSM composite hydrogel films are able to resist permeability of microbes and act as a barrier to it, and therefore, they can be used in wound care application and act as an alternative for conventional dressings (Mali et al., 2023). Table 3 shows the results of the microbial permeability study.

Protein adsorption study was carried out using Lowery method. As blood consists of high amount of albumin proteins, BSA was used as the model protein in this study. In this method, final solution consists of color. This color is formed in two steps: initially, copper reacts with alkali, whereas reduction of the Folin–Ciocalteu reagent due to copper treated proteins leading to formation of the blue color solution which can be analyzed spectrophotometrically (Lowry et al., 1951). When it comes to wound dressing, protein adsorption is important for finding how dressing adheres to cells (Mali et al., 2023). The results of protein adsorption of the prepared composite hydrogel films are given in Table 3. Hydrogel films' protein adsorption was found to be between 0.029 and 0.047 mg/cm2. The results indicated that there is very less protein adsorption on the composite hydrogel films. The very low adsorption of protein might be because of the hydrophilic nature of hydrogel films. This hydrophilicity is proved by the broad peak observed of -OH stretching. In case of hydrogels, films exhibiting low protein adsorption are preferred generally (Singh and Dhiman, 2015).

To assess the hemocompatibility of prepared composite hydrogel film, the hemolysis assay was done. This test analyzes the breakdown of red blood cells (RBCs) when they are exposed to hydrogel films. Injury or rupturing of RBCs leads to production of hemoglobin, which gets solubilized in the nearby fluid during the process. This fluid was analyzed spectrophotometrically for evaluating its content. Table 3 shows the results of hemolysis assay. The negative and positive controls showed 0.001 % and 3.436 % hemolysis, respectively. Hemolysis was found to be in the range of 2.212 %–4.561 %, which was in permissible range of 5 % (Ghorpade et al., 2024). Findings showed that as the CA concentration was increased, hemolysis increased, whereas as the concentration of FSM was increased, the percentage of hemolysis appeared to be decreased. The reason for the same is that as FSM is increased, hydrophilicity is enhanced, which therefore reduces the polymer and RBC's interactions and overall reduce destruction of RBC's (Alexandre et al., 2014; Mali et al., 2023).

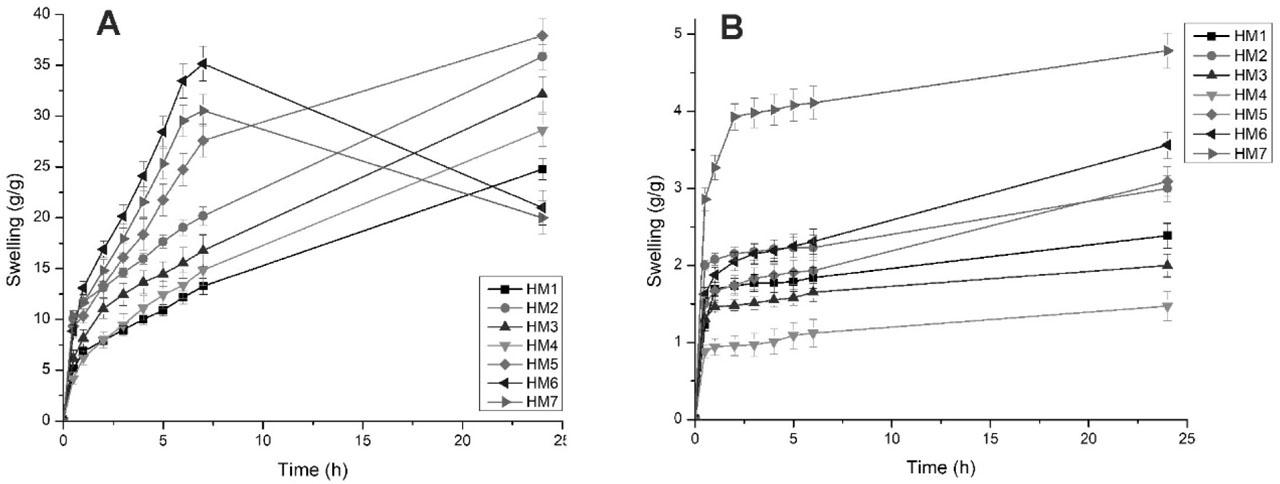

Hydrogel films have the tendency to swell by absorbing aqueous medium into their matrix (Sulastri et al., 2021). To mimic the ability of hydrogel films to absorb wound exudates, swelling studies are conducted (Mahmood et al., 2022; Sadiq et al., 2022). For determining the swelling index of the prepared hydrogel films, they were allowed to immerse in Tris HCl buffer pH 7.4 and 0.1 N HCl. These hydrogel films were weighed at predetermined time intervals. Initially, the weight of dry hydrogel films was recorded. While weighing, the excess fluid was carefully blotted by using tissue paper (Mali et al., 2017a). The findings indicated that the swelling index of hydrogel films depends on various factors such as concentration of the polymer ratio and crosslinker. The results of swelling ratio of hydrogel films in Tris HCl buffer pH 7.4 are shown in Figure 2(a). Due to deprotonation of carboxylic acid groups present in crosslinked CMTG polymer network at a pH of 7.4, hydrogel exhibits good fluid absorption and retention leading to swelling. Deprotonation leads to increase in electrostatic repulsion in between negatively charged carboxylate ions, causing swelling. As the extent of fluid absorption is increased, expansion of the structure takes place (Mali et al., 2023; Sadiq et al., 2022).

Swelling profile of hydrogel films in Tris HCl buffer pH 7.4 (a) and 0.1 N HCl (b).

The swelling ratio of hydrogel films in Tris HCl buffer pH 7.4 was found to be in the range of 20–37.83 g/g. The findings indicate that the film having the lowest amount of crosslinker, that is, HM2, showed excellent swelling; on the contrary, the film having the highest crosslinker concentration, that is, HM4, exhibited lowest swelling. The HM5 batch showed the highest amount of swelling (i.e., 37.83 g/g). Only CMTG hydrogel film showed 24.78 g/g swelling. (no clarity) In the swelling study of prepared hydrogel films, it was recorded that from batch HM2 to HM4, as the CA concentration was increased, the swelling subsequently decreased. This may be attributed to the increase in crosslinking densities aiding in the formation of denser structure and resisting the movement of the polymer chains. This formation of denser structure makes it difficult for the aqueous medium to enter into hydrogel matrix (Sadiq et al., 2022).

From batch HM5 to HM7, as the concentration of FSM was increased, abrupt swelling was observed. Highly hydrophilic nature of FSM might be the reason for the abrupt swelling. But as FSM does not undergo crosslinking with CA, it only gets entangled in the network structure formed by CMTG and CA crosslinking. So, as the swelling increases, the weak hydrogen bonding of entangled polymeric chains of FSM starts to break. The breaking of bonds caused the removal or washout of the FSM polymeric chains, leading to beginning of erosion. Hence, HM6 and HM7 batches showed high and rapid swelling; but after 6 h, erosion of the films started due to the reason mentioned above. HM6 showed high swelling compared to HM7, even though HM7 had the highest concentration of FSM. This might be due to rapid erosion of FSM polymer chains from the matrix of crosslinked CMTG and CA (Mahmood et al., 2022; Mali et al., 2023; Sadiq et al., 2022).

For studying the effect of pH on the swelling properties of the prepared hydrogel films, swelling study was carried out in 0.1 N HCl. Compared to Tris HCl buffer pH 7.4, the swelling in 0.1 N HCl was quiet low. This effect may be attributed to protonation of carboxylate ions in CMTG matrix. This reduces the electrostatic repulsion between polymeric chains. Therefore, decrease in repulsive forces leads to decrease in swelling. Figure 2(b) shows the swelling profile of hydrogel films in 0.1 N HCl (Mali et al., 2023, 2018, 2017a).

Diffusion process was used to load the drug into the hydrogel films. The films were allowed to swell in the medium, which led to diffusion of the drug in the matrix system of the hydrogel and as the films were dried, the drug was entrapped in the matrix of the hydrogel (Badadare et al., 2020). The results of drug loading are given in Table 4. The loading was observed in the range of 30.45–43.86 mg/g. The observed results indicate that as the CA concentration was increased from batch HM2 to HM4, drug loading decreased. This may be because of increase in the crosslinking density, leading to decrease in swelling (Mali et al., 2023). However, in the case of batch HM5 to HM7, as the FSM concentration was increased, the loading increased to some extent. The HM6 batch showed highest loading, which might be due to high swelling in the hydrogel film (Mahmood et al., 2022; Sadiq et al., 2022).

Drug loading, drug release, and order of release of composite hydrogel films.

| Batch | Drug loading (mg/g) | Q5h (%)a | Zero order | First order | Higuchi | Korsmeyer–Peppas | Order of release | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (r2) | (r2) | (r2) | (r2) | n | ||||

| HM1 | 34.58 ± 2.61 | 53.34 ± 2.58 | 0.881 | 0.733 | 0.967 | 0.968 | 0.511 | Non-Fickian |

| HM2 | 37.45 ± 1.27 | 73.52 ± 3.09 | 0.795 | 0.640 | 0.914 | 0.939 | 0.552 | Non-Fickian |

| HM3 | 34.58 ± 1.94 | 67.00 ± 2.77 | 0.798 | 0.637 | 0.916 | 0.931 | 0.567 | Non-Fickian |

| HM4 | 30.45 ± 4.13 | 60.02 ± 1.62 | 0.799 | 0.643 | 0.916 | 0.936 | 0.588 | Non-Fickian |

| HM5 | 36.66 ± 2.77 | 70.74 ± 2.71 | 0.740 | 0.582 | 0.871 | 0.897 | 0.535 | Non-Fickian |

| HM6 | 43.86 ± 3.65 | 78.90 ± 3.73 | 0.792 | 0.623 | 0.908 | 0.908 | 0.523 | Non-Fickian |

| HM7 | 39.99 ± 3.99 | 88.60 ± 3.27 | 0.809 | 0.627 | 0.917 | 0.892 | 0.514 | Non-Fickian |

Percent MTZ release at the end of 5 h

n: release exponent, r2: correlation coefficient

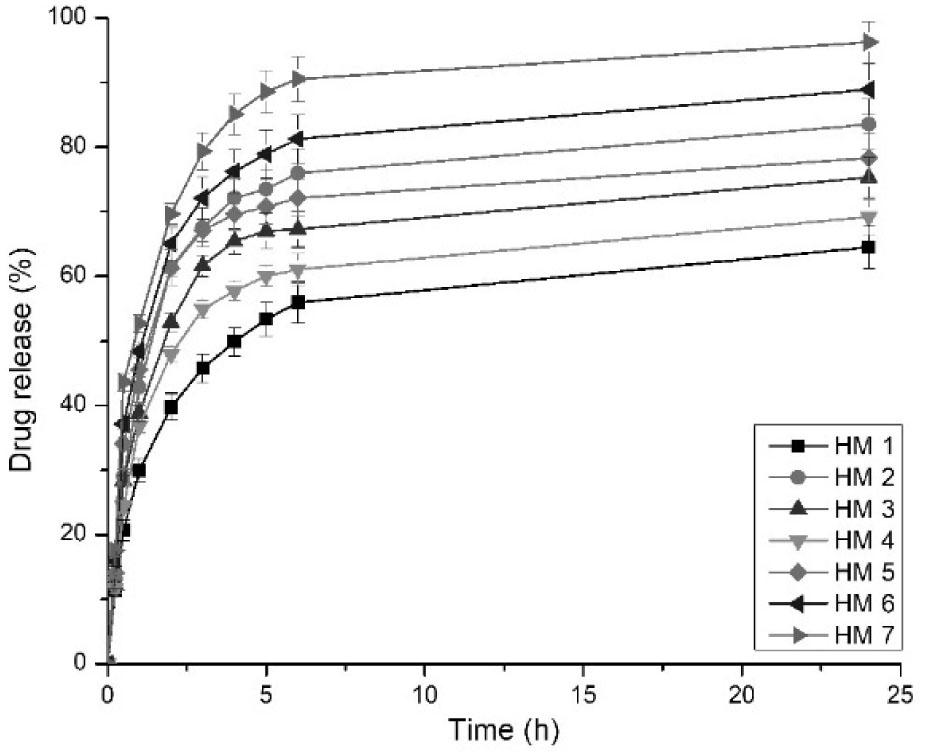

Drug release was studied in Tris HCl buffer pH 7.4 as the dissolution medium (Mali et al., 2017a). Release from the hydrogel films majorly depends on various factors such as swelling, interactions between polymers and drug, drug solubility, and concentration of crosslinker (Mahmood et al., 2022). Figure 3 shows the release profile of MTZ from CMTG–FSM composite hydrogel films, and Table 4 shows the percent drug release in 5 h. All the batches on coming in contact with the dissolution medium showed an initial burst release from 29.92 % to 52.71 % in 1 h. This initial burst release might be due to the surface-associated drug. After completion of drug loading, drying of the films was done, during which a large amount of drug got transferred to the surface. This surface-bound drug was easily released into the dissolution medium (Sadiq et al., 2022). After the burst release in 1 h, most of the drug was released at the end of 6 h. Overall, drug release of MTZ was observed to be between 64.52 % and 96.25 % in 24 h.

MTZ release from hydrogel films in Tris HCl buffer pH 7.4.

It was observed in the studies that as the CA concentration was increased from batch HM2 to HM4, the drug release was found to be increased from 69.18 % to 83.51 %. This might be attributed to low swelling at the high concentration of CA. The only CMTG batch showed 64.52 % drug release in 24 h. These findings indicated that FSM concentration also influences the drug release to a greater extent. It was observed that as the FSM concentration increased from batches HM5 to HM7, the drug release increased. This might be because of the high FSM concentration increasing the swelling. While swelling process as the fluid is absorbed into the matrix, hydrogel films tend to release the drug present in the matrix structure of hydrogel films. Batch HM7 showed the highest amount of drug release because as the swelling is increased in this batch, the polymeric chains of FSM are broken and get dissolved in the dissolution media, leading to fast release of drug from the matrix.

To elucidate the mechanism of MTZ release, the drug release data for all batches were fitted to various kinetic models, including zero-order, first-order, Higuchi, and Korsmeyer–Peppas. The Korsmeyer–Peppas model showed the best fit for all batches, as indicated by the highest correlation coefficients (r2), suggesting that release is primarily diffusion controlled through the hydrated polymer network. Table 4 shows the results of release mechanism and diffusion coefficient (n). The finding indicates that all the hydrogel films show non-Fickian release behavior (Erikci et al., 2024). The interaction between MTZ and hydrogel was indicated by the value of diffusion coefficient greater than 0.5. It was observed that as the CA concentration was increased, the value of release exponent was increased, indicating that the drug was released by diffusion coupled with swelling mechanism (Mali et al., 2023). Whereas as the FSM concentration was increased, the value of release exponent was decreased, suggesting a shift toward Fickian mechanism. Here, the drug release becomes more dependent on diffusion through a tighter matrix rather than on swelling (Sheikh et al., 2020).

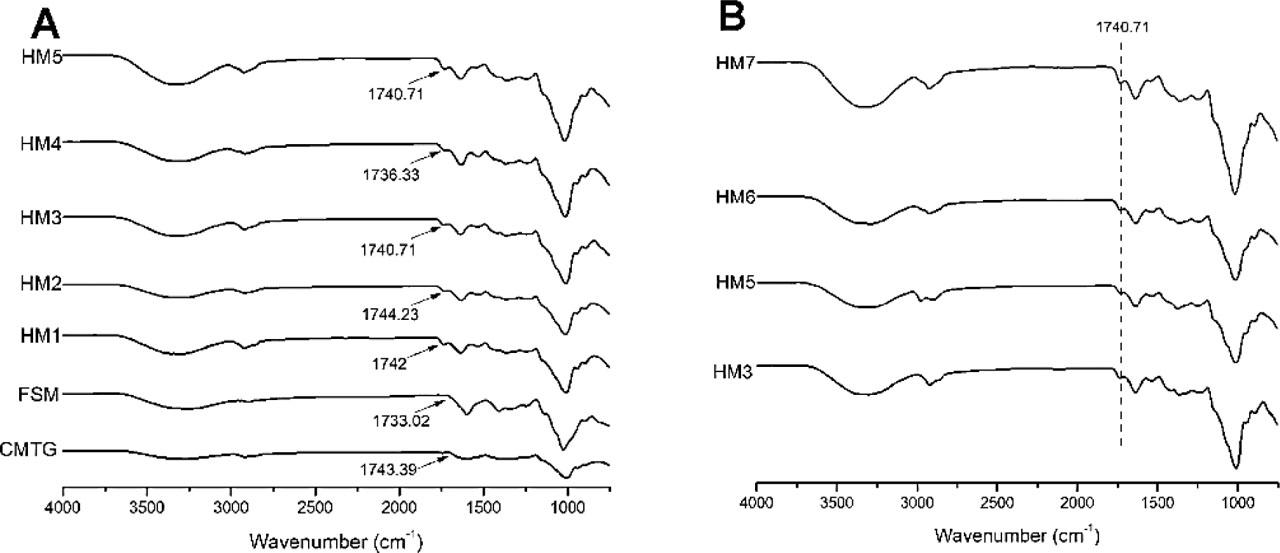

The ATR–FTIR spectra of CMTG, FSM, and HM1–HM5 hydrogel films was recorded and is given in Figure 4(a). The FSM spectrum showed a broad -OH stretching band at 3259.34 cm−1. FTIR revealed two peaks at 2899.06 cm−1 and 2834 cm−1, which were recognized as -CH resonance. The C=O stretching vibration was shown by a peak at 1733.02 cm−1 representing the presence of galacturonic acids. Two peaks at 1596.77 cm−1 and 1408 cm−1 indicating carbonyl groups and uronic acids, respectively, were found. At 1135.92 cm−1 and 1024 cm− 1, two absorption bands corresponding to C–O–C glycosidic linkage and =CO stretching were observed, pointing the presence of xyloglucan in FSM. The ATR–FTIR spectra of CMTG demonstrates multiple notable peaks, at 3275 cm−1 a broad strong peak indicating stretching vibration of –OH group. Due to asymmetric stretching of –CH, medium peaks were recorded at 2918 cm−1 and 2858 cm−1. It exhibited peak at 1743.39 cm−1, which may be due to C=O of the ester group. The carboxyl groups in CMTG were revealed by peaks at 1629.23 cm−1 and 1402.33 cm−1. A peak at 1005 cm−1 indicated C–O–C stretch showing glycosidic linkage.

ATR–FTIR spectra of (a) CMTG, FSM, and hydrogel films HM1–HM5 and (b) hydrogel films HM3, HM5, HM6, and HM7.

The ATR–FTIR spectra of all the composite hydrogel films showed an additional peak around 1740 cm−1, which indicates the crosslinking of ester, confirming the occurrence of crosslinking reaction between CMTG and CA. In the HM2–HM4 hydrogel films, as the concentration of CA was increased, ester crosslink peak shifted toward lower wavenumbers. The gradual shift to lower wavenumbers indicates increased H bonding involving the carbonyl group (Sharmin et al., 2022). The peak intensity was found to be increased. This may be due to higher crosslinking density (Mali et al., 2023; Miller et al., 2024). The ATR–FTIR spectra of HM3, HM5, HM6, and HM7 hydrogel films is shown in Figure 4(b). The peak intensity of ester carboxyl peak at 1740 cm−1 was found to be decreased when FSM concentration was increased. This may be attributed to inability of FSM to undergo crosslinking with CA, leading to only entanglement of the FSM polymeric chains. This ultimately reduces the covalent crosslinks in the hydrogel matrix (Chen et al., 2023). When FSM concentration was increased in the hydrogel film, the peak observed between 3500 cm−1 and 3100 cm−1 became progressively wider and more intense. This widening may be associated with an increase in the number of hydrogen bonding between CMTG–FSM, FSM–FSM, and CMTG–CMTG, as well as interweaving of polymeric chains within the network structure (Deng et al., 2020).

The TGA curves for CMTG and FSM are shown in Figure 5(a), highlighting the degradation profile for the temperature range of 30 °C–600 °C. The TGA thermogram of FSM showed fast degradation from 30 °C to 200 °C compared to CMTG; this may be due to its high hydrophilic nature. The initial weight loss was attributed to evaporation of water molecules from the polymer structure. It was observed that both the polymers showed major weight loss at 200 °C–400 °C; this may be due to decomposition of polymer chain backbone. Notably, CMTG showed delayed degradation compared to FSM; this might be due to chemical modification of tamarind gum. After 400 °C till 600 °C, both the samples slowly degraded (Mali et al., 2023, 2017a).

TGA curves of (a) FSM, CMTG, and hydrogel films HM1 and HM5 and (b) hydrogel films HM2–HM7.

When FSM was incorporated into CMTG hydrogel films, the thermal stability was found to be decreased. It was observed that as the CA concentration was increased from HM2 to HM4, the thermal stability decreased. This may be attributed to over crosslinking leading in formation of small or low-molecular weight ester crosslinks, which degrade rapidly (Surendra Babu et al., 2015). The TGA thermogram of HM2–HM7 hydrogel films are given in Figure 5(b). All the films exhibited primarily three stages of decomposition. It was observed from the findings that the first stage of decomposition occurred between 30 °C and 180 °C. The second stage of weight loss was found to be from 180 °C to 380 °C and represented highest weight loss in this region. The initial weight loss was attributed to removal of free water bound from the polymeric structure, and the second stage of weight loss was due to degradation of polymeric backbone. The overall findings show that as the FSM concentration was increased, the thermal stability of the hydrogel films decreased (Mahmood et al., 2022; Mali et al., 2023; Sadiq et al., 2022).

In the present study, CA-crosslinked CMTG–FSM composite hydrogel films for wound dressing were developed successfully from biowaste-derived polymers. The study demonstrated that the swelling as well as matrix integrity of the hydrogel films was enhanced compared to CMTG alone hydrogel films. It was observed from the findings that as the concentration of FSM was increased, the weight loss and contact angle increased, whereas the thickness and TCC of hydrogel films decreased. As the concentration of CA was increased, swelling of the hydrogel films was observed to be decreased. The films with increasing concentration of FSM exhibited high swelling. TCC, swelling, and drug loading were found to be correlated. A good WVTR of the hydrogel films was recorded. The developed films exhibited resistance for permeation of microbes and were found to be hemocompatible. MTZ was selected as the model drug, and drug loading was carried out using diffusion mechanism. The release of MTZ from CMTG–FSM composite hydrogel films showed non-Fickian release behavior. Characterization of the CMTG–FSM composite hydrogel films was conducted. ATR–FTIR proved the formation of ester crosslinking between CMTG and CA. The entanglement of FSM was manifested by the ATR–FTIR spectra. The TGA curves of FSM and CMTG demonstrated that FSM showed less thermal stability than CMTG. The overall findings indicate that the developed CMTG–FSM composite hydrogel films can be promising candidates for wound dressing applications.