The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) remains one of the most influential frameworks in shaping the trajectory of European rural development. Initially conceived in the aftermath of World War II to ensure food security and stabilize agricultural markets, the CAP has gradually evolved into a comprehensive policy instrument that seeks not only to sustain agricultural production but also to address broader socio-economic and environmental concerns [1], [2], [3]. Over time, it has become evident that rural development cannot be reduced to agricultural outputs alone. It must also engage with issues of community resilience, demographic change and environmental sustainability [4], [5], [6], [7], [8].

Globally, the challenges of rural development share striking similarities, even beyond the European context. In Latin America, rural development programs struggle to balance agricultural modernization with the preservation of traditional livelihoods, while in Sub-Saharan Africa, integrated initiatives attempt to reduce poverty while adapting to climate change and weak infrastructure [9]. In Asia, rural development has become closely tied to food security policies and demographic shifts [5]. These examples demonstrate that rural development is not a European challenge alone, but a worldwide issue with profound implications for agriculture, governance and social well-being.

Within Europe, the LEADER initiative emerged as a flagship program for fostering bottom-up governance, participatory decision-making, and integrated territorial development. By empowering Local Action Groups (LAGs) to design context-sensitive strategies, the LEADER approach sought to overcome the limitations of top-down agricultural policies [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18]. Its emphasis on territorial focus, networking, innovation and partnership positions it as a paradigm shift in rural policy. Nevertheless, despite its ambitious design and repeated recognition as a model of participatory governance, the effectiveness of LEADER has varied significantly across member states, largely due to differences in institutional capacity, governance frameworks and funding structures [12], 19], 20].

The rationale for this study arises from this tension. While numerous studies have evaluated the outcomes of LEADER, many are limited to national case studies or emphasize either social or economic aspects without offering a comprehensive synthesis [21], [22], [23]. Moreover, systematic reviews that critically assess the breadth of evidence across different contexts remain limited. By conducting a structured review of 50 peer-reviewed scientific papers published between 1996 and 2024, this study aims to provide a balanced evaluation of the socio-economic dimensions of rural development under the LEADER program, highlighting recurring themes and challenges.

The methodological approach is designed to move beyond descriptive reporting. By synthesizing findings from multiple sources [24], 25], the study evaluates both the successes and limitations of the LEADER framework, while also recognizing the constraints posed by administrative complexity and uneven funding distribution [20], [26], [27], [28]. The ultimate aim is not only to document the past and present state of rural development initiatives but also to contribute to the ongoing debate on how integrated policies can more effectively address the complex realities of rural areas in Europe and beyond [12], 29].

Accordingly, this study provides a systematic and comparative synthesis of the socio-economic impacts of the LEADER program across the European Union. It seeks to identify recurring patterns of success and limitation, examine the structural factors that shape these outcomes and assess the potential for more integrated and sustainable rural development strategies. The guiding research question of this study is not to directly evaluate the outcomes of LEADER initiatives, but rather to reconstruct how existing academic studies have interpreted and assessed these outcomes. By synthesizing the findings of 50 peer-reviewed articles, the paper provides a reasoned reconstruction of the ways in which the scholarly literature has examined the socio-economic effects of LEADER. This approach clarifies that our analysis is based on the interpretations of previous authors, rather than on direct program data, surveys, or official EU monitoring sources. Accordingly, the originality of this review lies in identifying the recurring themes, patterns and limitations across the academic discourse, thereby contributing to a more consolidated understanding of how LEADER has been represented in research.

Τhis study applied a systematic review approach with a qualitative analytical framework to examine the socio-economic impacts of the LEADER program across the European Union. The review followed established methodological guidelines for systematic reviews in the social sciences [19], 24], 26].

The reference universe consisted of peer-reviewed journal articles, conference proceedings and relevant book chapters addressing the LEADER program and rural development. The primary databases used for the search were Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar, as they provide comprehensive coverage of agricultural economics, rural development and public policy studies [3], 30], 31].

Selection Criteria.

Articles were included based on the following criteria:

-

1.

Timeframe: Publications from 1996 to 2024 were selected to capture the evolution of the LEADER program since the LEADER II [17], 28], 32].

-

2.

Geographic Scope: Only studies focusing on European Union member states were considered, given the policy-specific nature of the LEADER initiative [16], 18].

-

3.

Content Relevance: Articles had to explicitly address the LEADER approach, its governance structures, or its socio-economic and environmental outcomes [10], 22], 28].

-

4.

Language: Only studies published in English were included to ensure consistency of analysis.

-

5.

Publication Type: Peer-reviewed journal articles were prioritized. Relevant book chapters and conference proceedings were included when directly linked to the research question.

Exclusion criteria included:

-

–

Non-peer-reviewed publications.

-

–

Articles focusing exclusively on technical agricultural production without a rural development dimension.

-

–

Papers outside the EU context.

Data Extraction and Coding.

A total of 50 articles meeting the inclusion criteria were selected. Information was extracted into an Excel database designed for systematic reviews, including:

-

1.

Publication year.

-

2.

Country studied.

-

3.

Journal title.

-

4.

Keywords.

-

5.

Main research question.

-

6.

Findings categorized into social, economic, or blended dimensions of rural development.

The data was coded using thematic content analysis. Following established practices [21], 33], 34], key categories were derived inductively from the material. Articles were coded based on whether they emphasized social aspects (e.g., community cohesion, governance, partnerships) or economic aspects (e.g., diversification, financial impacts, local markets). Ambiguous or overlapping cases were coded in both categories to preserve nuance, as recommended in previous LEADER-focused reviews [25], 26], 28].

In addition to these two main categories, we also considered environmental, institutional and cultural dimensions when explicitly addressed in the studies. For transparency, “social” aspects were defined as those related to community cohesion, governance, networks and participation. “Cultural” aspects were distinguished from the social dimension by focusing on identity, traditions, heritage and the preservation of local values, even when these intersected with social dynamics. “Institutional” aspects referred to governance frameworks, administrative capacity and multilevel coordination, while “environmental” aspects referred to sustainability, resource management and ecological outcomes. When overlap was unavoidable, studies were cross-coded to preserve nuance, but each assignment followed these working definitions.

This methodological approach not only promotes transparency but also tackles issues highlighted in previous assessments concerning the representativeness and strength of evidence in research related to LEADER [35], 36].

The choice of a systematic review was guided by the need to integrate fragmented findings across diverse contexts [12], 28]. Unlike narrative reviews, the systematic review provides transparency in article selection, enhances replicability and allows for clearer thematic synthesis.

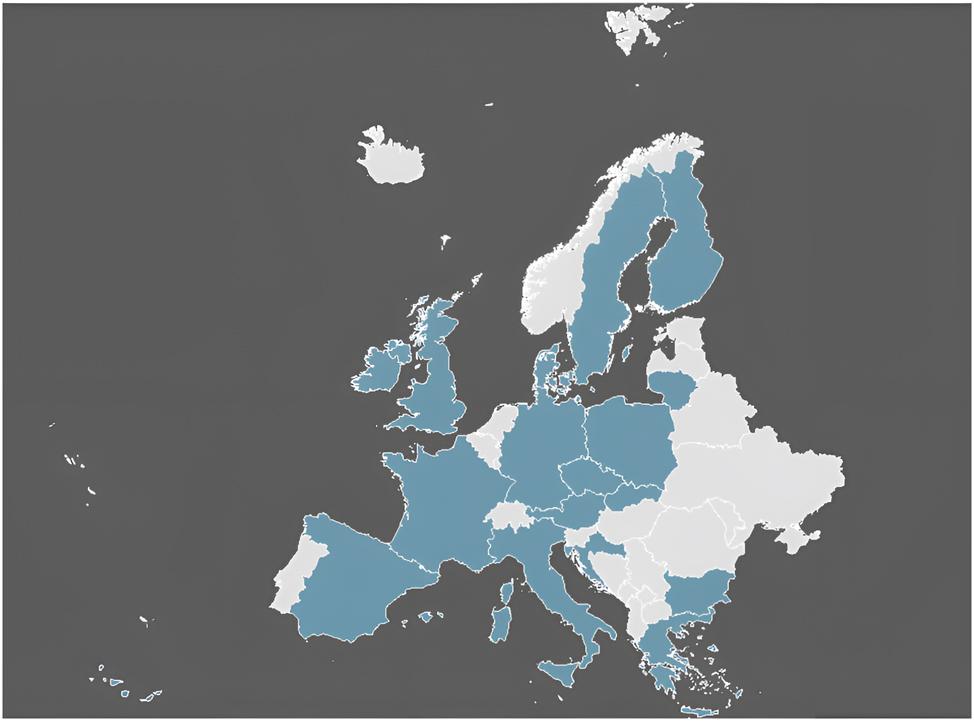

While advanced software such as NVivo, VOSviewer and Iramuteq can facilitate bibliometric mapping and co-citation analysis, this study deliberately used Excel for data management to prioritize clarity and accessibility of coding. Nonetheless, limitations such as reduced visualization capacity and the absence of advanced network analysis are acknowledged (Figure 1).

Geographic distribution of the reviewed studies. Source: Authors own elaboration based on scopus, web of science, and analyzed journal articles.

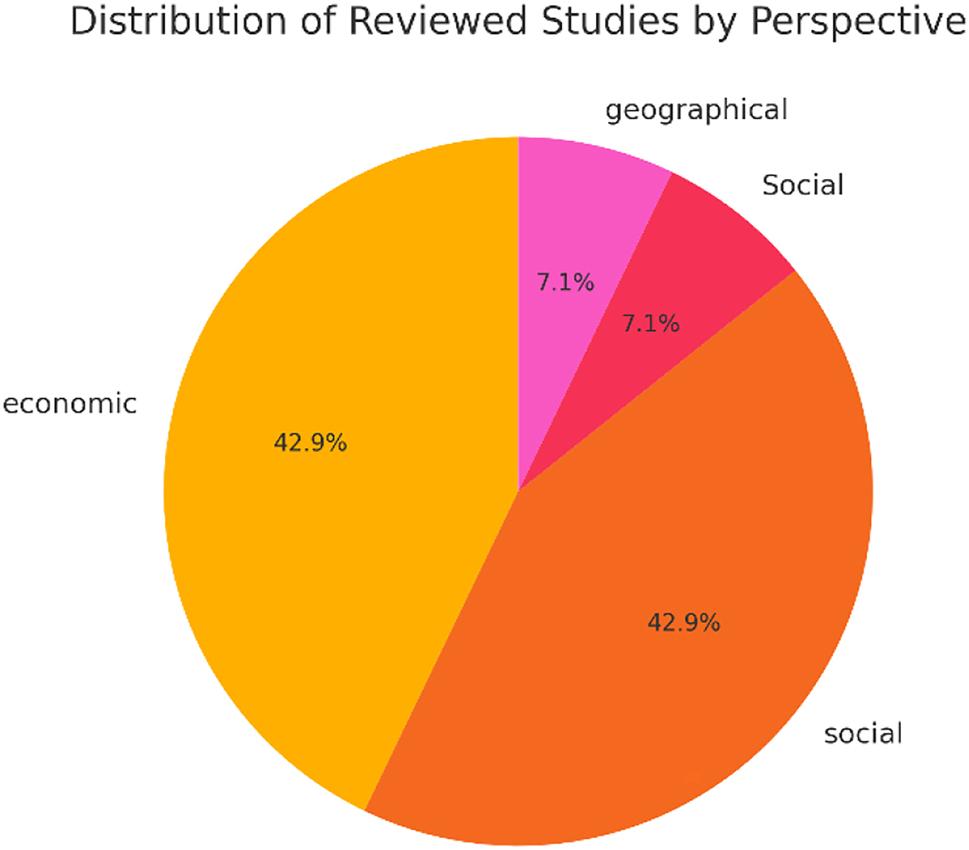

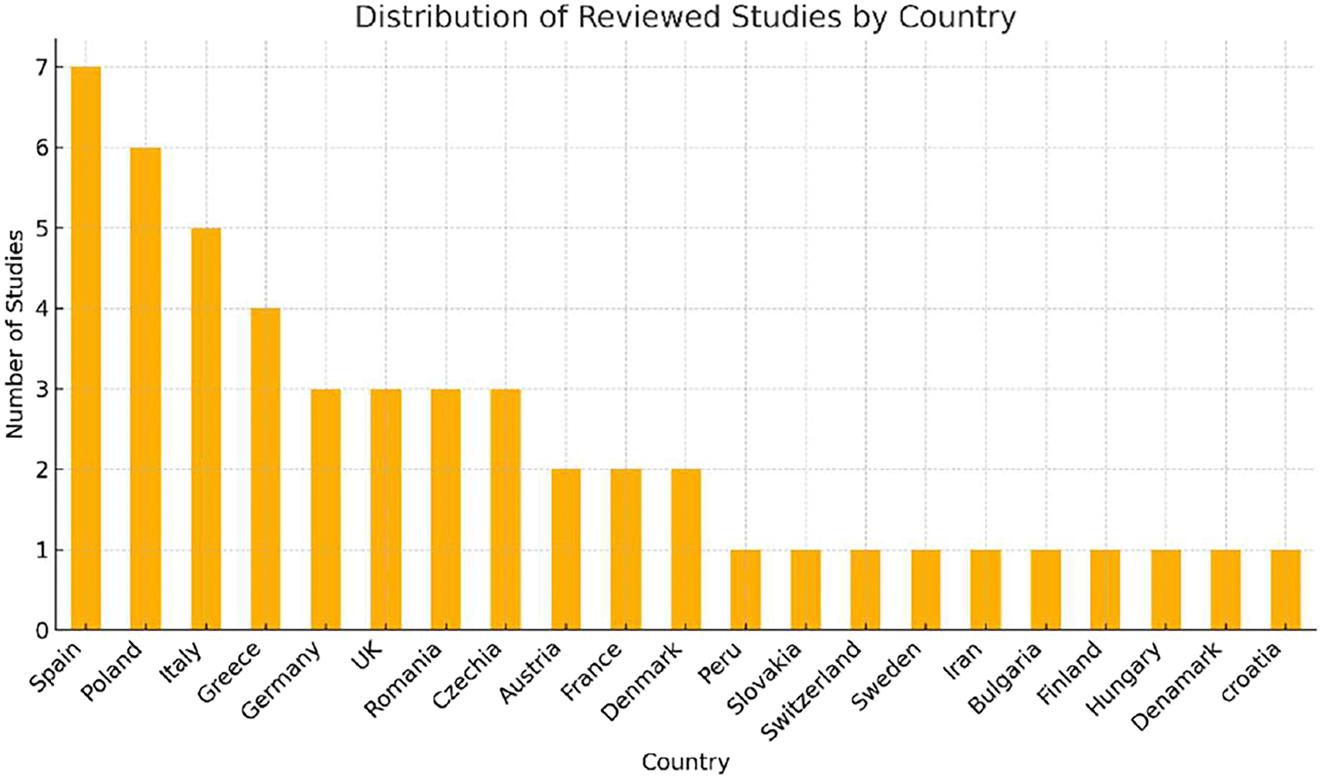

To enhance transparency, the distribution of the reviewed publications is presented both in tabular and graphical form. Table 1 in the main text summarizes their distribution by year, while the complete list of all 50 studies is provided in Appendix A (Table A1). Figures 2 and 3 summarize their distribution by country and research perspective. In addition, Appendix A includes a schematic flow diagram (Figure A1), adapted from the PRISMA framework, to illustrate the main steps of the article selection process. While a full PRISMA protocol was not applied, the diagram serves to provide a transparent overview of how the final sample was derived. These visual representations help to better comprehend the sample’s makeup and ensure alignment with the inclusion criteria mentioned earlier.

Distribution of reviewed articles by year. Source: Authors’ synthesis of reviewed studies.

| Year range | Number of articles | Percentage of total |

|---|---|---|

| 1996–2005 | 4 | 8 % |

| 2006–2010 | 5 | 10 % |

| 2011–2015 | 9 | 18 % |

| 2016–2020 | 18 | 36 % |

| 2021–2024 | 14 | 28 % |

| Total | 50 | 100 % |

Distribution of the 50 reviewed publications by research perspective (economic, social, or both). Source: Authors’ elaboration based on systematic review results.

Distribution of the 50 reviewed publications by country. Source: Authors’ elaboration based on systematic review results.

To further clarify the selection process, we provide a simplified PRISMA-style flow description. The initial search across Scopus, Web of Science and Google Scholar yielded more than 200 records. After removing duplicates, approximately 160 unique records were screened by title and abstract. Of these, many were excluded because they did not explicitly address the LEADER approach or lacked a rural development perspective. Ninety full-text articles were then assessed for eligibility. 40 studies were excluded at this stage because they either focused on non-EU contexts, did not contain socio-economic perspectives, or were not peer-reviewed publications. The final sample therefore consisted of 50 peer-reviewed studies, which were subsequently analyzed in this review.

Appendix A (Table A1) provides additional details for clarity. The “Country” column refers to the country or countries that were the focus of the empirical case study in each paper, rather than the institutional affiliation of the authors. This distinction ensures consistency and allows readers to understand the selection process more accurately.

Despite its contributions, this study is subject to several limitations. First, the review is restricted to 50 peer-reviewed publications covering 17 EU countries. While this scope provides valuable comparative insights, it does not capture the full breadth of the vast literature on LEADER and rural development [26], 37]. Furthermore, the exclusive focus on English-language articles may have excluded relevant research published in national languages [17], 32].

Second, the analysis primarily concentrates on economic and social dimensions. Although references to environmental, institutional and cultural aspects were included where relevant [10], 38], 39], these dimensions remain underrepresented in the sample. This imbalance reflects both the priorities of existing literature and the methodological constraints of this review.

Third, the coding process, while systematic, relied on manual classification verified through cross-checking among authors. The use of specialized software such as NVivo or IRaMuTeQ could potentially enhance transparency and allow for more complex network analyses [22], 26], 40]. Future research could therefore apply mixed-methods approaches, combining qualitative synthesis with bibliometric and content-analysis tools.

Finally, the study did not evaluate the quality of the reviewed articles in a PRISMA framework, which may limit the robustness of the conclusions. Subsequent studies could implement stricter inclusion criteria and quality assessments, as well as extend the analysis to non-EU contexts where LEADER-like programs have been adapted [41], 42].

Future research should give greater attention to cross-cutting issues, including environmental sustainability, cultural identity and the participation of disadvantaged groups [29], 43], 44]. Longitudinal analyses could shed light on how LEADER’s impacts evolve over time, while comparative studies with other EU and non-EU rural development initiatives would enrich the understanding of its role in fostering inclusive and sustainable rural futures.

From the systematic review of 50 peer-reviewed articles published between 1996 and 2024, two dominant dimensions of analysis emerged: economic and social. Other aspects of sustainability such as institutional, environmental, and cultural, were occasionally referenced, but their coverage was inconsistent. Thus, the analysis focuses on economic and social dimensions, with additional aspects revisited in the discussion.

A notable increase in the number of studies was observed after 2015, with peaks in 2019 and 2021. This reflects the growing academic and policies of interest in the LEADER program and its evolving role in rural development.

Geographically, the articles examined 17 European countries, with the highest concentration in Italy, Spain, and Poland. This pattern reflects both their active participation in LEADER projects and the relatively high availability of academic research focusing on these contexts, In contrast, several EU member states are not represented in the reviewed sample. This absence is explained by the limited number of peer-reviewed publications in English addressing LEADER in those countries, as well as by differences in the degree of national engagement with the program. Previous reviews have noted similar imbalances, highlighting that the distribution of case studies often mirrors both research capacity and policy emphasis across regions [17], 29], 32].

LEADER has significantly contributed to strengthening community cohesion and participatory governance. Studies by Thuesen [33] and Teilmann & Thuesen [34] demonstrated how inclusive LAG board composition in Denmark enhanced local legitimacy. In Greece, Arabatzis et al. [45] found that LAGs improved collaboration and civic engagement, while Papadopoulou et al. [46] highlighted the importance of policy networks for reinforcing social trust.

The program has also promoted social innovation. Chatzichristos & Nagopoulos [22] revealed that LEADER triggered significant social innovation through local partnerships, while Dax & Oedl-Wieser [29] concluded that more than two decades of LEADER initiatives have reshaped rural development perspectives across the EU. Yet, Navarro et al. [47] spointed out that participation of disadvantaged groups remains limited in Andalusia, highlighting persistent inclusivity challenges. Table 2 provides a synthesis of the main social impacts identified in the reviewed literature.

Main Social Results of the LEADER Program. Source: Authors’ synthesis of reviewed studies.

| Key findings | Example evidence | Reported challenges |

|---|---|---|

| Strengthened social capital | Multiple studies (e.g., Dax & Oedl-Wieser [29]; Chatzichristos & Nagopoulos [22]) | Gender imbalance and exclusion risks |

| Enhanced community cohesion | Multiple studies (e.g., Arabatzis et al. [45]; Papadopoulou et al. [12]) | Limited institutional capacity of LAGs |

| Participatory governance | Multiple studies (e.g., Thuesen [33]; Teilmann & Thuesen [34]) | High administrative workload for volunteers |

For a full list of studies supporting each key finding, see Appendix A (Table A1).

Despite its dual contributions, the balance between economic and social outcomes is uneven. Lošťák & Hudečková [20] observed that economic initiatives were more prominent than social projects in the Czech Republic. Pollermann, Raue & Schnaut [40] noted that governance complexity in Germany sometimes hindered broad community involvement. Environmental, institutional and cultural dimensions are still underrepresented [10], 32], 39], despite their importance for long-term sustainability.

Several studies underlined the interdependence of economic and social dimensions. For example, community-led innovation often produced simultaneous economic benefits (e.g., new jobs, entrepreneurship) and social benefits (e.g., trust-building, cohesion). Despite these successes, the integration of environmental, cultural and institutional dimensions was limited. This gap highlights the need for future research and policy frameworks that adopt a more holistic view of sustainability.

Figure 2 visualizes the relative prevalence of economic and social perspectives in the reviewed studies. Figure 3 further illustrates the uneven distribution of reviewed studies across EU member states, highlighting regional imbalances in literature.

The findings confirm that the LEADER program has played a pivotal role in enhancing economic development across rural Europe. It has supported income diversification, entrepreneurship and local market integration [4], 38], 48]. For example, Galluzzo [4] highlighted LEADER’s role in generating employment opportunities in Romania through agrotourism, while Alonso & Masot [48] observed similar impacts in Spain. Mrnjavac & Perić [49] emphasized that the effectiveness of LAGs in attracting project subsidies depends strongly on municipal support, illustrating the importance of governance structures.

LEADER has also facilitated access to EU funds for innovation and sustainability. Chevalier & MačIulyté [50] documented how the program encouraged institutional learning in France and Lithuania. Pollermann et al. [37] found that the multilevel governance framework in France, Germany, and Italy created opportunities for innovation but also added administrative burdens. However, Biagini et al. [51] showed that income effects remain uneven across farms in Italy, reflecting structural disparities. These results are summarized in Table 3, which illustrates the main economic outcomes reported across member states.

Main economic results of the LEADER program. Source: Authors’ synthesis of reviewed studies.

| Key findings | Example evidence | Reported challenges |

|---|---|---|

| Income diversification | Multiple studies (e.g., Galluzzo [4]; Alonso & Masot [48]; Biagini et al. [51]) | Long term sustainability remains weak |

| Establishment of micro-enterprises | Multiple studies (e.g., Mrnjavac & Perić [49]; Pollermann et al. [37]) | Bureaucratic and financial barriers |

| Market access and innovation | Multiple studies (e.g., Chevalier & MačIulyté [50]; Pollermann, Raue & Schnaut [40]) | Unequal allocation of resources |

For a full list of studies supporting each key finding, see Appendix A (Table A1).

This review’s findings affirm that the LEADER initiative has been crucial in fostering both economic and social progress in rural regions throughout Europe. Consistent with earlier studies, our results indicate that LEADER significantly aids in diversifying income, encouraging entrepreneurship and enhancing local markets, while also bolstering community unity and participatory governance [10], 14], 19], 52]. This dual impact supports the argument that rural development policies must integrate social and economic dimensions rather than treating them in isolation [9].

However, the results also highlight persistent challenges that echo concerns raised in earlier studies. Administrative complexity, uneven allocation of resources, and limited scalability of projects continue to hinder the program’s long-term effectiveness [20], 26]. These findings align with Dax and Oedl-Wieser [29], who observed that while LEADER facilitates innovation, its outcomes remain uneven across different contexts and Pollermann et al. [40], who stressed the limitations in integrating sustainability concerns into local action plans.

Although this review primarily focused on economic and social impacts, some studies also considered environmental, institutional and cultural dimensions. For instance, Wojewódzka-Wiewiórska [39] emphasized the underrepresentation of environmental sustainability in LEADER evaluations. Similarly, Chatzichristos and Nagopoulos [22] discussed the need for more attention to institutional factors that shape local governance capacity. Cultural dimensions, as noted in broader assessments such as Dax et al. [28], remain marginal in most evaluations, despite their relevance for maintaining rural identity and cohesion. These gaps suggest that future research and policy design should adopt a more holistic perspective on sustainability, moving beyond the two dominant dimensions.

The findings also carry important implications for policymakers and practitioners. For governments and EU institutions, the results underscore the need to simplify administrative procedures [19] and ensure a more equitable distribution of resources among regions [20], 26]. For Local Action Groups (LAGs), the evidence highlights the importance of building institutional capacity to maintain community engagement and long-term project sustainability [23], 28], 34]. For rural communities, LEADER demonstrates the potential of participatory governance to empower local actors and foster inclusive development [10], 33], 44]. For the scientific community, this synthesis of 50 studies provides a consolidated perspective on the socio-economic impacts of LEADER, addressing the fragmentation observed in earlier reviews [12], 13], 20], 29].

This review extends beyond previous studies by integrating findings from 50 peer-reviewed articles on the LEADER approach across 17 EU nations. Importantly, the study does not directly evaluate the outcomes of the LEADER program itself, but rather reconstructs how the academic literature has interpreted its socio-economic effects. By consolidating the perspectives of previous authors, the review identifies recurring themes, shared concerns, and points of divergence. In this sense, the originality of our contribution lies in providing a reasoned reconstruction of the scholarly debate on LEADER, which helps clarify how the program has been represented in research and highlights where gaps remain for future inquiry.

This variability is largely explained by differences in institutional capacity, governance frameworks, and funding structures, as well as persistent administrative burdens. By consolidating fragmented evidence and identifying cross-country patterns, the paper advances theoretical discussions on participatory, place-based development and underscores the need for more integrated, context-sensitive and multidimensional approaches to rural sustainability.

This study has several limitations. First, the reliance on 50 peer-reviewed articles, while analytically rich, may not capture the full breadth of the LEADER literature, particularly local-language studies [11]. Second, the exclusive focus on English-language sources may limit insights from non-English contexts. Third, while Excel was used to manage data coding transparently, the absence of advanced bibliometric software (such as NVivo, VOSviewer, or IRaMuTeQ) restricted the ability to map co-authorships or co-quotations [24], 25].

Future research could expand the scope by:

-

–

Including additional dimensions of sustainability, such as environmental and cultural impacts [39].

-

–

Incorporating bibliometric and network analysis tools to visualize interconnections among studies [25], 53].

-

–

Conducting comparative analyses of LEADER with other rural development programs globally [29].

Overall, this review provides strong evidence that the LEADER program continues to contribute significantly to rural development in Europe, despite persisting limitations. Its dual economic and social contributions reaffirm the importance of participatory, bottom-up approaches in addressing the complex realities of rural areas. However, for LEADER and similar initiatives to reach their full potential, future strategies must adopt a more integrated, multidimensional approach to sustainability and ensure that policy design addresses the barriers that remain [10], 12], 20], 29].