Introduction

there is cause for optimism as long as there is a need for optimism. Cause and need converge in the bent school or marginal church in which we gather together to be in the name of being otherwise. [1: p. 1747]

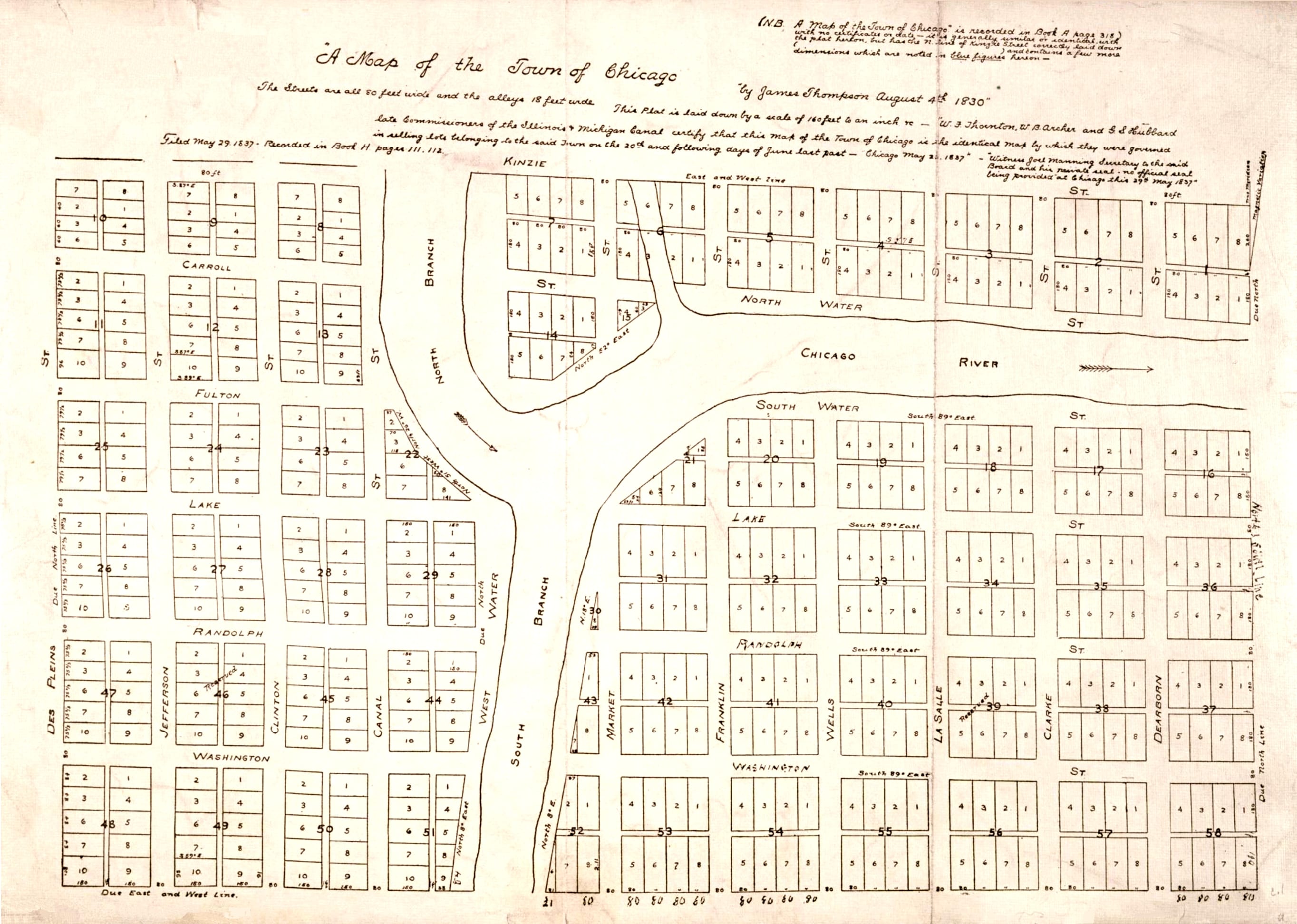

Chicago, a city that appeared in 1830 on territory taken from the Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi people, was nothing more than an abstraction, a map, and even a spectre. The first formal recognition of its existence appears on a plat commissioned to enable real estate transactions (Figure 1). A ‘dream of New York-based capital’ as Lawrence Bennett fondly describes it [2: p. 1], the city was an abstract empirical entity, measured and determined by a colonial grid superimposed upon a dense, low-lying expanse of marsh and grassland located at a point where a river emptied into a lake. The spectral appearance of the grid in 1830 marked a terrain of real estate speculation that in 1900 became the fastest growing city in the world.

Figure 1

James Thompson’s plan of Chicago, made on 4 August 1830 to the order of the Illinois and Michigan Canal Commissioners. This marked the first formal recognition of a place named ‘Chicago’. (Chicago History Museum, ICHi-034284, with restoration by John M Wolfson).

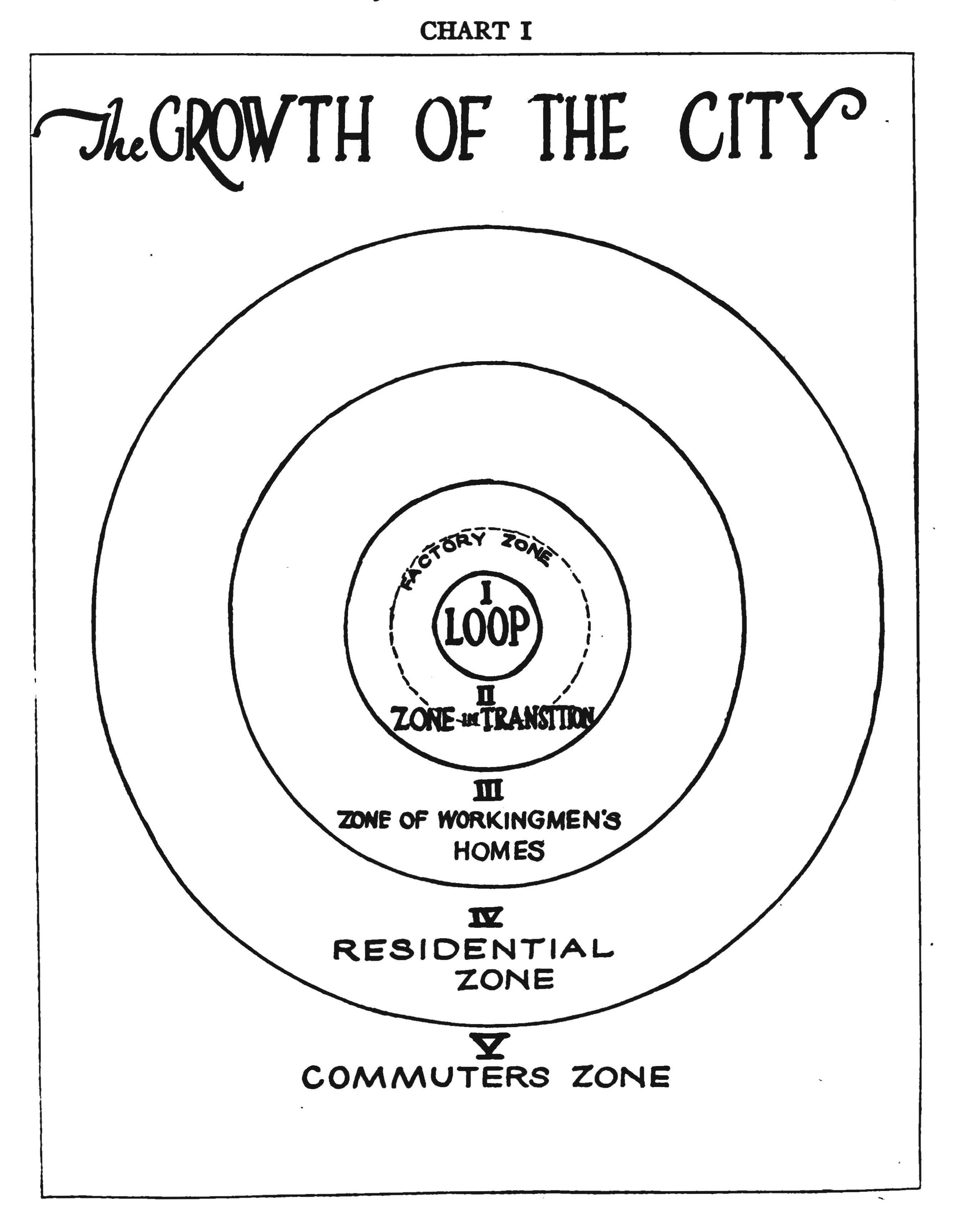

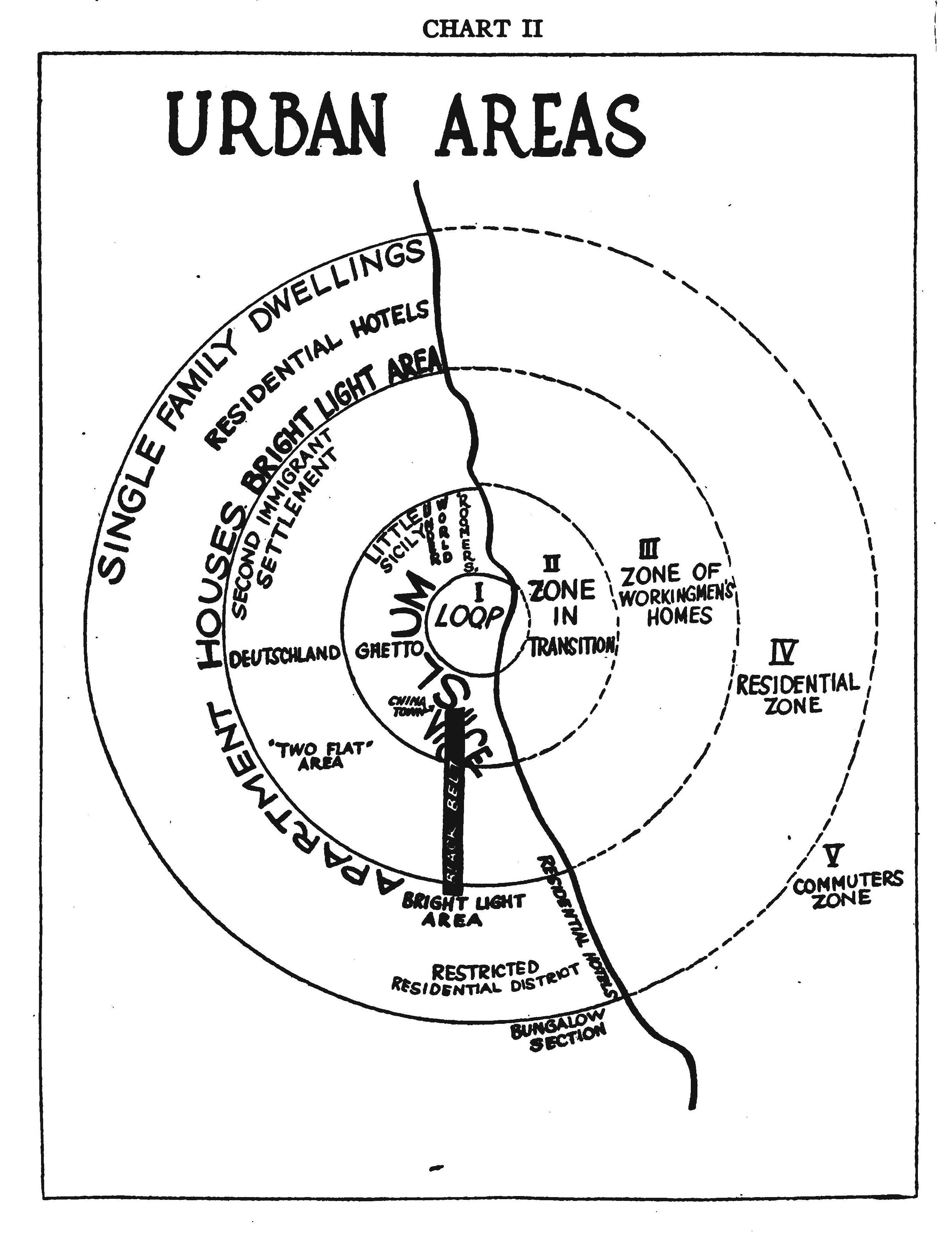

In 1925, the sociologists Robert E. Park and Eugene Burgess mapped another process of possession and dispossession as they studied the social organisation of the city, overlaying a model of succession borrowed from ecological theory on the outlines of the city’s boundaries (Figure 2). Twenty years later, in 1945, their students St. Clare Drake and Howard Cayton would revise and remake that map. Both Park and Burgess, who were white, and Drake and Cayton, who were Black, marked the area of the city where Black people lived, situating it as an anomaly cutting through an otherwise well-determined model of ‘human ecology.’ Park and Burgess labelled it the ‘Black Belt’ while Drake and Cayton named it the ‘Black Metropolis’ (Figure 3). This shift in terminology represented a radically different understanding of the city and its culture that also offers a template for a radical practice for sustainability.

Figure 2

Chart I (from Park R, Burgess E, McKenzie R. The City: Suggestions for Investigation of Human Behavior in the Urban Environment. University of Chicago Press; 1925: p. 51)

Figure 3

Chart II (from Park R, Burgess E, McKenzie R. The City: Suggestions for Investigation of Human Behavior in the Urban Environment. University of Chicago Press; 1925: p. 55)

Naturalising racial segregation

In 1925, Robert E. Parks, with Earnest W. Burgess and Roderick D. McKenzie, published The City. Most of the book is attributed to Parks, with Burgess contributing two chapters and McKenzie one. In the introduction, Parks described the book as ‘a program of studies of human nature and social life under modern city conditions’ [3: p. vii] Two diagrammatic maps in the second chapter, ‘The Growth of the City: An Introduction to a Research Project,’ attributed to Burgess, would become emblematic of their work, and have a profound and troubling impact on American sociology and urban policy. The first map, titled ‘The Growth of the City,’ claimed to show ‘an ideal construction of the tendencies of any town or city to expand radially from its central business district’ [3: p. 51]. Drawn as a set of five concentric circles, it was intended to illustrate the ‘the main fact of [city] expansion, namely, the tendency of each inner zone to extend its area by the invasion of the next outer zone. This aspect of expansion may be called succession, a process that has been studied in detail in plant ecology’ [3: p. 51]. The map is entirely abstract, with one odd specificity – the centre circle, the central business district, is labelled ‘The Loop,’ the very particular term for Chicago’s downtown. This mix of broad abstraction and occasional specificity is emblematic of the ideas presented in The City, and of Park’s work in general (Figure 2). The second map, titled ‘Urban Areas,’ follows a few pages later and more explicitly references Chicago, showing two tell-tale features – the slightly diagonal meandering line of the lakefront travels from the top to bottom of the diagram and a series of distinctive Chicago neighbourhoods are accurately located along that line (Figure 3). All but one of these residential territories aligns with the concentric zones defined in the first map. The Loop is at the centre. ‘Slums,’ ‘vice,’ ‘underworld,’ ‘Little Sicily,’ ‘ghetto,’ and ‘Chinatown’ all fit into the second zone. ‘Second immigrant settlement,’ ‘Deutschland,’ and ‘two flat area,’ all fit into the third zone of workingmen’s homes. And so on, with one exception, a black bar labelled ‘Black Belt’ that crosses three zones. Burgess’s discussion of this map presented Chicago as the model for American cities. He asserted that ‘In the expansion of the city a process of distribution takes place which sifts and sorts and relocates individuals and group by residence and occupation. The resulting differentiation of the cosmopolitan American city into areas is typically all from one pattern, with only interesting minor modifications’ [3: p. 54]. He went on to describe the residential zones, pointing out the anomaly of the ‘Black Belt, with its free and disorderly life’ and then claimed ‘This differentiation into natural economic and cultural groupings gives form and character to the city. For segregation offers the group, and thereby the individuals who compose the group, a place and a role in the total organisation of city life. Segregation limits development in certain directions, but it releases it in others’ [3: p. 56].

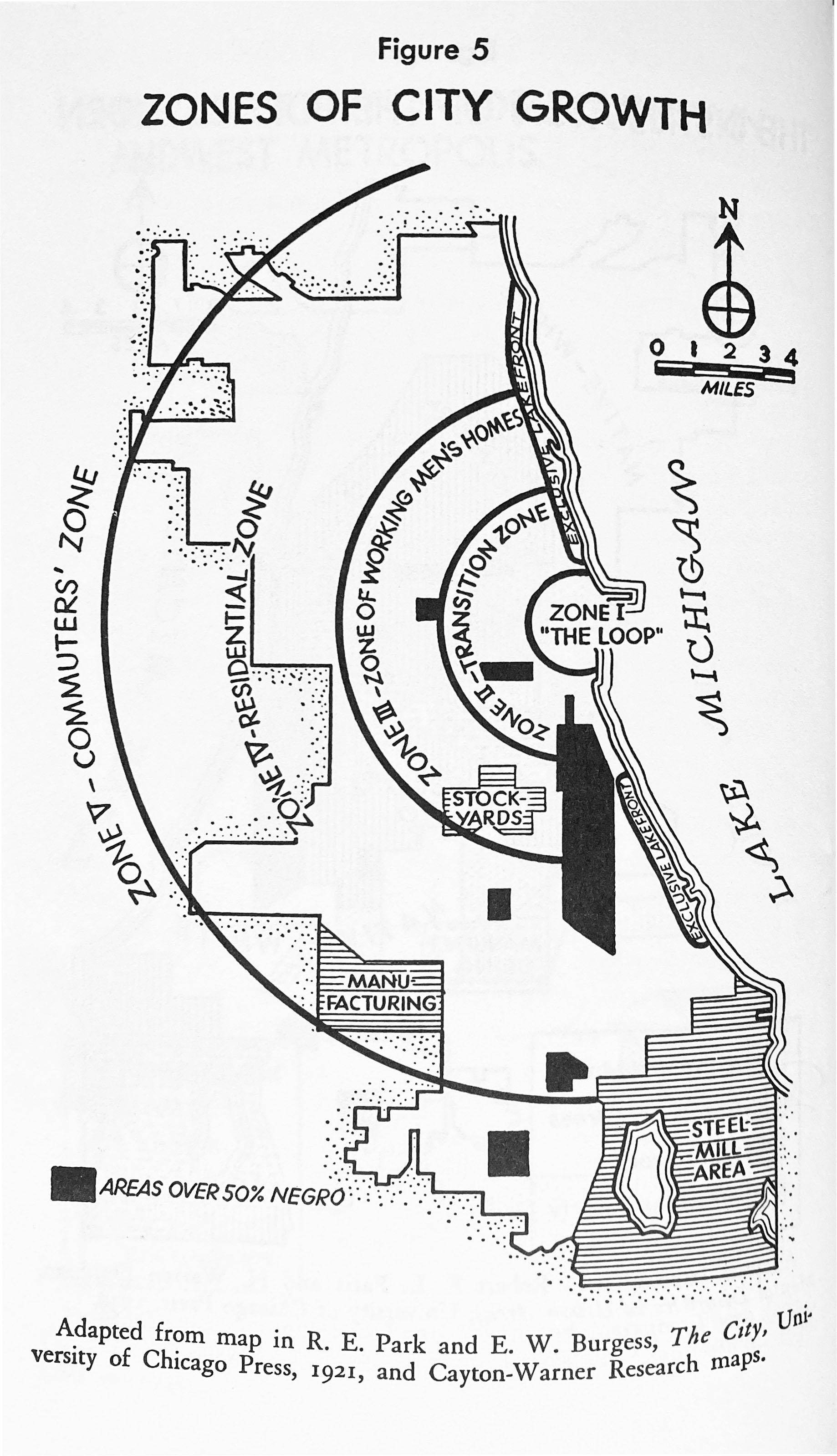

Figure 4

Zones of City Growth, Adapted from map in Park RE, Burgess EW. The City, University of Chicago Press; 1921, and Cayton-Warner Research maps. (Courtesy of the Houghton Mifflin Harcourt).

Questioning the ‘color-line’

In 1945 St. Clair Drake and Horace R. Cayton, published Black Metropolis: A Study of Negro Life in a Northern City. A new version of Park, Burgess, and McKenzie’s 1925 ‘Urban Areas’ map appeared in the first chapter (Figure 4). It is last in a sequence of four maps that intend to document and explain the ‘pattern’ of the city. Titled ‘Zones of City Growth’, this version of the concentric zone model of urban growth is presented as documentation of the distinctive character of Black neighbourhoods in Chicago; it is no longer a generic model of the American city.

Drake and Cayton used the maps, along with four tables of data to establish the two central claims of the book. First, they argued that the residential patterns of Black Chicagoans did not follow the Darwinian model of succession [competition, conflict, assimilation] diagrammed in the 1925 ‘Urban Areas’ map:

Negros are not finally absorbed in the general population. Black Metropolis remains athwart the least desirable residential zones. Its population grows larger and larger, unable to either expand freely or scatter. It becomes a persisting city within a city, reflecting in itself the crosscurrents of life in Midwest Metropolis, but isolated from the mains stream. [4: p. 17]

The second, more consequential – even radical – claim, asserted the pivotal role this isolated settlement played in the past, present, and future of the city: ‘These Negros who make up Black Metropolis […] hold a pivotal position in the equilibrium of political and economic power of Midwest Metropolis’ [4: p. 29]. The rest of the book, which at almost 800 pages was four times the length of Park and Burgess’s book The City, documented and analysed ‘the structure and organisation of the Negro community’ in Chicago. It pointed out that ‘The first white man to settle at Chickagou [a Potowatami term that was the source for Chicago’s name] was a Negro,’ and described how the ‘color-line’ had been drawn in the city, assembling a dense description of Chicago’s physical and social structure. It then concluded with an assessment of the paradox of Black life in American cities, caught between market ideologies of ‘free competition’ and the social reality of ‘fixed status,’ while engaged in a ‘constant struggle for complete democracy’ [4: pp. 31, 757, 767]. By complete democracy, they meant that the right to vote and the freedom to choose how, when, and where to work had to be embedded in social order and political culture that allowed democratic principles to thrive. Drake and Cayton end the first edition of the book advocating for this complete democracy as a global project. Subsequent editions – the book has gone through four editions with major revisions in 1962 and 1970 – are less tied to wartime rhetoric and more focused on the difficult and sometimes violent reality of the American Civil Rights movement as it played out in Chicago.

In many ways, Black Metropolis was part of a larger academic project that became known as the Chicago School of Sociology; Drake and Cayton signalled their affiliation with this genre of scholarship by dedicating the book to Robert E. Park, whom they described as ‘a friend of the Negro people’ [4]. The research presented in the book was the product of a series of studies funded as part of a Depression-era government program, the Works Progress Administration, designed to provide unemployed Americans with work that served the public interest. Over 200 academics and researchers collected data and observations over a period of four years, following research agendas that were clearly indebted to, but not limited by, Park’s social theories.

The studies that comprise the research presented and interpreted in the book were initially designed to provide evidence to support Park’s ideas – evidence that was not available when The City was published in 1925. These studies could test Park’s notion of human ecology and the concentric ring model of urban growth, as 20 years had passed since the publication of The City. Drake and Cayton’s book was published at the close of a period that saw an explosion of population growth due to the ‘Great Migration’ of American Blacks from the south; between 1920 and 1940, the population of Black Chicagoans more than doubled, growing from 109,458 to 337,000 [4: p. 8]. If the Park and Burgess theory of succession depicted in the concentric rings of the ‘Growth of the City’ diagram in their book was a reality, there should be evidence of the assimilation of Black Chicagoans into the newer, outer, higher income residential zones.

In addition, Black Metropolis reframed the ideas presented in The City by engaging in careful consideration of scholarship on Black American life, an approach that points to a radically altered and amplified understanding of American cities, particularly those in the north. At the core of Drake and Cayton’s book is a discussion of the ‘color-line’, a term popularised by Fredrick Douglass in the nineteenth century and used to denote the broad range of practices, explicit and implicit, sanctioned and unsanctioned, legal and illegal, that enforce racial segregation and discrimination in the USA. As Drake and Cayton introduce their work on the ‘color-line’ in Chicago, they quote from W.E.B. DuBois’s 1903 book, The Souls of Black Folk, ‘the problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color-line’ [4: p. 97]. Drake and Cayton then present an extended discussion of interviews and survey research interrogating the motivations for southern Blacks to move to Chicago, establishing that many were drawn to a broader set of economic and civic rights and freedoms than were available in the South, even if social equality was unobtainable.

As Drake and Cayton examined the attitudes toward social equality among Black Chicagoans, they asked, ‘Do Negroes want social equality?’ and examined the influence of Black educator and formerly enslaved person, Booker T. Washington’s ‘Atlanta Compromise’. Proposed in an 1895 speech to a white southern audience, the ‘Atlanta Compromise’ prioritised economic advancement for American Blacks over social equality and was widely interpreted to endorse racial segregation. Drake and Cayton describe it as a ‘philosophy of compromise’ [4: p. 52]. They then present an extended discussion of the popularity of Washington’s ideas among Black Chicagoans and acknowledge Washington’s ‘great popularity and influence among southern white people’ [4: p. 120].

By contrast, there is no mention of W.E.B. DuBois in Park and Burgess’s The City, even though, by 1925, DuBois was widely acknowledged as a pioneer in the sociology of African Americans in northern cities, having published The Philadelphia Negro in 1899. There is no mention of Washington, either. However, there are numerous references to DuBois and Washington a few years earlier, in Park’s first major academic publication, Introduction to the Science of Sociology, published in 1921.

The decline of the ‘Black Metropolis’

Robert E. Park is often credited as a pioneering scholar of race relations in the USA. He attributed his insights on the topic to his experience working for Booker T. Washington in Alabama at Tuskegee Institute between 1907 and 1914. Of his time in Alabama, he said:

These seven years [working for Washington at Tuskegee] were for me a sort of prolonged internship during which I gained a clinical and first hand knowledge of a first class social problem ... [It was from Washington that] I gained some adequate notion of how deep-rooted in human history and human nature social institutions were, and how difficult, if not impossible it was, to make fundamental changes in them by mere legislation or by legal artifice of any sort. [5: p. 150]

He came to Alabama after studying with John Dewey, William James, and Georg Simmel, and worked in the tradition of Max Weber and Emile Durkheim [6: pp. 89-90]. When he left Tuskegee in 1914, he took a position in the sociology department at the University of Chicago. During his time there he taught courses on race relations and extended Washington’s pioneering creating educational opportunities for American Blacks by mentoring a generation of African-American academics, including Drake and Cayton, who would become the first generation of Black scholars at US universities.

Park’s work on race relations is inseparable from his systematic understanding of the city as ‘a spatial pattern and a moral order’ governed by a model of succession that operated through four processes: competition, conflict, accommodation, and assimilation [6: pp. 89, 92]. The notion of succession, spatial patterns, and the processes of competition, conflict, accommodation, and assimilation were derived from his studies of the then emerging science of ecology, notably plant communities [6: p. 99; 7]. The ‘Urban Areas’ map that appeared in The City and then reappeared in the Black Metropolis was intended to visualise that model, each concentric zone defining an ecological niche, where communities composed of people with similar social characteristics would emerge.

This model of human ecology shares Washington’s conservative understanding of social change; for Park, it was ‘an attempt to investigate the processes by which the biotic balance and social equilibrium are disturbed, the transition is made from one relatively stable order to other’ [8]. Park believed that this this equilibrium model was generalisable and could be applied to other American cities. He also believed it explained race relations, which he described as ‘a cycle of events which tends everywhere to repeat itself’ [9]. For Park and Burgess, racial segregation was both positive and negative, a natural process, where ‘inequality becomes normal, even normative’ [10: p. 38]. At the same time, Park led the opposition to racist eugenic policies and practices in the USA in the 1920s, and a colleague, W.I. Thomas, would describe him as ‘free of racial prejudice as it was possible for a white man to be’ [4; 6: p. 106].

By contrast, racial segregation was not part of the natural order in Drake and Cayton’s Black Metropolis. As students and employees in the Department of Sociology at the University of Chicago, they were indebted and dependent on Park and his colleagues. Nonetheless, their book presented a substantial critique of Park’s theories. First, the data analysed in the first chapter of Black Metropolis demonstrated that the processes associated with urban growth and Park’s race relations cycle were critically flawed; there was competition, conflict, and accommodation but no assimilation. Second, they reframed the Black communities that were the focus of their work; Park and Burgess’s ‘Black Belt,’ characterised by ‘disorderly life,’ became Drake and Cayton’s ‘Black Metropolis,’ ‘a city within a city’ [3: p. 56; 4: p. 12].

As Neil Brenner has recently pointed out, Park and Burgess’s characterisation of city growth and the development of residential neighbourhoods as a ‘natural’ process ’renders invisible’ the bias, prejudice, and violence that produced Chicago’s ‘Black Belt’ [11]. Park’s human ecology, as a theory of social change, erased history along with the political and institutional practices that created racial apartheid on the city’s south side. Park and his colleagues’ persistent advancement of these theories, despite the overwhelming evidence to the contrary, is difficult to understand in retrospect. For example, in their Urban Areas diagram, they chose to draw the ‘Black Belt’ in a manner that distinguished it from every other Chicago community but neglected to account for why it had to be drawn in such a distinctive manner, something so at odds with the graphic design of the map that Drake and Cayton could repurpose it to make the opposite argument. Perhaps the most remarkable thing about Drake and Cayton’s book is that it happened within the same academic setting that produced Park’s human ecology. In Black Metropolis, segregation was not natural. It was economic, political, and social, and the overwhelming array of histories, data, interviews, and observations presented in the book made that reality visible.

The authors’ decision to write Black Metropolis as popular non-fiction, rather than an academic publication, explicitly registered their desire to advocate for and create change, along with signalling their decision to work outside conventional American academia. As part of their effort to position Black Metropolis as a popular work, Drake and Cayton invited Richard Wright, a friend of Cayton, to write the introduction. Their choice to open the book with Wright’s radical rhetoric indicates Drake and Cayton’s understanding of the type of change required to achieve equality for Black Americans. Born in Mississippi in 1908, Wright became part of the ‘Great Migration’, moving to Chicago in 1927, where he worked in the US Post Office, joined, then left, the Communist Party (an early short story was titled ‘I Tried to Become a Communist’), and began his writing career. When he wrote the introduction to Black Metropolis, he had already published his most widely popular protest novel, Native Son, in 1940. Wright started his introduction by describing the book as a ‘landmark of research,’ and then asserted that ‘Chicago is the city from which the most incisive and radical Negro thought has come’ [4: p. xvii]. He described the book as ‘a scientific report upon the state of unrest, longing, hope among urban Negroes’ [4: p. xxv]. He then made it clear that Black Metropolis advanced an understanding of race relations in distinct opposition to Park’s human ecology:

The hour is too late to argue if there is a Negro problem or not. Riots have swept the nation and more riots are pending. This book assumes that the Negro’s present position in the United States results from the oppression of Negroes by white people, that the Negro’s conduct, his personality, his culture, his entire life flow naturally and inevitability out of the condition imposed upon him by white America. [4: p. xxix]

When new editions of Black Metropolis were issued in 1961 and 1969, Drake and Cayton added a series of chapters at the end of the book that updated demographic data and described how Chicago had changed. In the 1961 update, they discussed the impact of postwar prosperity and the ‘Era of Integration,’ while observing that ‘the Black Ghetto has become a gilded ghetto, but a ghetto all the same’ [4: p. 796]. They discussed ‘slum clearance’ efforts by the city and federal governments and pointed out that these policies, which located all new public housing in Black neighbourhoods, were ‘a monument to Midwest Metropolis’s [Chicago’s] insistence upon residential segregation’ that reinforced the Black ghetto [4: p. 823]. Despite the promise of the Civil Rights movement, they observed that for ‘most people, wearing their dark skin color is like living with a chronic disease’ and closed with a warning:

Negroes in Bronzeville [the actual name of the Chicago neighbourhood at the core of Black Metropolis] are very much Americans. And this means, too, that if the masses are driven too far they are likely to fight back, despite their sometimes seemingly indifferent reactions to discrimination and segregation. A potential for future violence within Black Metropolis exists that should not and cannot be ignored. [4: pp. 804, 806

In 1969, they added a ‘Postscript,’ which opened with an account of the increasing level of segregation in Chicago and other American cities and discussed the influences and outcomes of the demonstrations and unrest that defined American city life throughout the 1960s. This chapter closed with a dispassionate account of the effects of the Black Power movement on local politics; they did not need to repeat their earlier prediction of violence because that potential for violent resistance had become a reality.

Despite the obvious flaws in Park’s model of city growth and race relations, it played a crucial role in the intensified segregation Drake and Cayton observed in 1969. Starting in the mid-1930s, Park’s theories provided the intellectual framework for a series of US national policies and practices that institutionalised racial segregation in American cities. Homer Hoyt, a real estate economist trained at the University of Chicago, instrumentalised Park’s understanding of race relations through a series of urban land values studies that became a government-sanctioned framework for mortgage lending and real-estate investment throughout the USA. His model of real-estate investment risk was remarkably straightforward. It was directly tied to race and depended on a hierarchy that prioritised mortgage investments in predominantly white neighbourhoods and made obtaining real estate mortgages in Black neighbourhoods almost impossible. This investment regime affected both public and private real estate investment and became known as redlining because this hierarchy was represented in maps of every urban area in the USA, and Black neighbourhoods, which fell into the highest risk category, were indicated in red (Figure 5).

Figure 5

Colour-coded Home Owners’ Loan Corporation map of Chicago, c. 1940.

The data that Hoyt collected was accurate; it did show a correlation between Black neighbourhoods and low land values. His interpretation of this correlation was tied to Park’s understanding of racial segregation as a natural occurrence, and, as Park put it, ‘how difficult, if not impossible it was, to make fundamental changes,’ an understanding that had deeply problematic consequences [5: p. 150]. Hoyt wrote that ‘while the ranking may be scientifically wrong from the standpoint of inherent racial characteristics, it registers an opinion or prejudice that is reflected in land values’ [12: p. 300; 13: p. 314]. Hoyt’s reification and the US government’s institutionalisation of these prejudices subsidised white families as they moved into racially exclusive suburbs and supported other forms of racial discrimination in housing markets.

As Richard Rothstein has pointed out in his 2017 book, The Color of Law, residential racial segregation in Chicago was ‘open and explicit government-sponsored segregation,’ reflecting discriminatory housing policies put in place throughout the twentieth century [14]. These policies were not imposed on the city from the outside. Chicago was the laboratory for these practices and policies, as research conducted by Park and Hoyt justified and enabled local institutions (including the University of Chicago) and local governments to advocate for, implement, and benefit from these policies and practices [14].

The concentric zone model of urban growth and the race relations cycle presented in Park and Burgess’s The City were abstractions that operated similarly to the nineteenth-century grid. Both diagrams of Chicago became instruments of procession and dispossession. While the 1830 plat enabled the violent removal of the area’s indigenous people, the 1925 map of concentric zones enabled the extraction of significant wealth from Chicago’s Black neighbourhoods. In 2017, the Metropolitan Planning Council, a Chicago non-profit planning organisation, in partnership with the Urban Institute, estimated that the Chicago region’s gross domestic product would increase by $8 billion if its current level of segregation was reduced to the US median (this would not eliminate segregation in the city; it would just bring to a median level for the USA, similar to Atlanta’s level of racial segregation) [15: p. 4]. When considering the impact on African American households, current scholarship indicates that the wealth produced by homeownership is a determining factor in their financial stability [16: p. 34]. This reflects the determinants of the racial wealth gap in the USA, where in 2016, white family wealth was seven times greater than Black family wealth [17]. Drawing a relationship between the racial wealth gap and the impact of the segregated real estate lending practices related to redlining is straightforward, even decades after the practice was made illegal. In 2020, Aaronson et al [18], found that redlining had ‘a causal, and an economically meaningful, effect on outcomes like household income during adulthood, the probability of living in a high-poverty census tract, the probability of moving upward toward the top of the income distribution, and modern credit scores’ [18: p. 22]. They go on to conclude:

The most striking conclusion from the analysis is the way that government intervention can alter communities for decades to come. The outcomes we studied were measured among cohorts born four decades after the HOLC maps were drawn, and yet the ratings still had visible impacts on many different social and economic outcomes in these communities. Our results provide clear evidence that policy decisions made decades ago can begin a process of investment and disinvestment with long-term consequences for communities and the residents within them. [18: pp. 22-23]

Drake and Cayton’s choice to rename the ‘Black Belt’ was central to their work and in that renaming instigated something other than the abstract instruments of dispossession represented by Park and Burgess’s diagrams and Hoyt’s redlining maps. In the third section of the book, where the focus of their analysis shifts from larger political and social issues to an actual portrait of the community, Drake, and Cayton compiled an extended account of the various names for Chicago’s South Side Black neighbourhood where they acknowledged the use of terms like ‘Black Ghetto’ and ‘Black Belt’ by ‘civic leaders’, but then went on to argue that the neighbourhood is ‘more than a ‘ghetto’ [4: p. 385]. On the other hand, Park’s use of the term ‘Black Belt’ reflected white, mainstream usage at the time of the publication of his study of the neighbourhood and reflected the marginal status of a zone of the city inhabited by people who were thought to be apart from, and less than, the rest of Chicago [19]. Notably, as Drake and Cayton pointed out, Park did not use the terms ‘South Side’ and ‘Bronzeville’, the names for the neighbourhood used by the Black people who live there [4: p. 383].

Drake and Cayton’s choice to use the term ‘Black Metropolis’ was deliberate and meant to create a new understanding of that distinct realm of the city. While there is no definitive scholarship that traces the relationship between Georg Simmel’s 1903 essay, ‘The Metropolis and Mental Life’, and Drake and Cayton’s book, the essay would have been known to both. As students of Robert Park, they would have been familiar with Simmel’s work, as Park studied with Simmel in Heidelberg and adopted some of Simmel’s ideas. (For example, in The City, Park described the city as a ‘state of mind, a body of customs and traditions […] attitudes and sentiments’ [3: p. 1]). Drake and Cayton also used the term ‘metropolis’ to name the city of Chicago the ‘Midwest Metropolis’, a choice that made it simultaneously a part of, and distinct from, the larger political and organisational entity of the city of Chicago. This idea of a metropolis within or embedded in another metropolis is a kind of doubling, or even something that could be read in Moten’s terms, as a fugitive – a metropolis that has the capacity to be both ‘immanent to the thing, but is manifest transversally’ [20]. The decision to name this neighbourhood the ‘Black Metropolis’ asserted that the community of people who lived there had created and were creating a form of life and a way of being that was at least equivalent to the dominant white culture of Chicago. As they put it, ‘this is not “just another neighborhood” of Midwest Metropolis’ [4: p. 379].

The term ‘Black Metropolis’ lives on as a historical reference, a geographic location, and an imaginary. Some scholars, like Christopher Robert Reed and Preston H. Smith II, rely upon the term to define a historical moment and a geographical location and advance revised and alternative histories of the area focused on class and entrepreneurship [21; 22]. Chicago’s city government officially acknowledged the term by designating a portion of the neighbourhood as the Black Metropolis-Bronzeville historic district. Scholarship that looks at Drake and Cayton’s renaming of the oldest Black neighbourhood and examines the implications of that decision is scant. That said, the contemporary popularity of the term, which has been adopted by the US National Parks Service and embedded in the narratives shaping research and engagement efforts by the University of Chicago, speaks to its role as a particular form of imaginary [23; 24]. This imagination animates an optimism that also attracts several local activist organisations, including Sweetwater Foundation and Blacks in Green, which informally reference Black Metropolis in their organising work.

Chicago’s historically Black neighbourhoods, where over 400 hectares lie empty after decades of housing disinvestment and demolition, defy easy characterisation [25]. Approximately 75 hectares of these vacant spaces emerged between 1995 and 2011, the product of an unprecedented demolition of publicly owned residential high rises that contained 17,000 apartments built by the city to house the poor. These were the second set of large-scale demolitions on the same sites. A political calculus, designed to consolidate the power of two mayors, a father, and a son, catalysed each episode.

Richard J. Daley, mayor of the city from 1955 to 1976, used the construction of high-rise public housing and two crosstown highways to demolish the densest areas of the Black Metropolis, reinforcing the boundaries between white and Black Chicago. The highways and housing concentrated poor African Americans into discrete, well-defined zones. His son, Richard M. Daley, who was the city’s mayor as it gentrified in the 1990s, then initiated the demolition of the high-rises his father built and gave these properties to real estate developers for new Urbanist developments, turning public property into private profit. Lawsuits delayed the high-rise demolitions for years. Once the 2008 recession started, most efforts at private redevelopment on the former public housing sites failed, leaving blocks of empty land, closed schools, and vacant storefronts.

If the construction and demolition of Chicago’s public housing could be understood as a failure of government policy and private initiative built on the legacy of Park and Burgess, the 14,000 abandoned residential lots found scattered throughout these same neighbourhoods are evidence of the success of Hoyt’s scheme to minimise real estate risk, which supported white suburban home ownership at the expense of African Americans [25]. The lack of access to conventional mortgages forced Black homeowners to seek expensive predatory loan contracts on over-priced properties in segregated neighbourhoods. These housing contracts inflicted substantial financial burdens on Black homeowners and led to defaults, disinvestment, abandonment, and demolition. As of November 2019, these vacant lots add up to 334 hectares of empty land, along with a remarkable decline in the population of Chicago’s African American middle class.

West Woodlawn, Chicago’s first middle-class Black neighbourhood, is defined by this emptiness. Located at the southmost tip of Drake and Cayton’s Black Metropolis, it is where Blacks in Green, a non-profit community organisation, works to create carbon-negative self-sustaining Black communities, a vision that emerges from the legacy of African American land stewardship. The neighbourhood’s median income is less than half the Chicago median, and 36% of the population is in poverty.

Most of West Woodlawn was developed in tandem with the 1893 World’s Columbian Exhibition. By 1920, white residents of Woodlawn had established residential restrictive covenants to prevent Black residents from living in the area. Nonetheless, Black residents settled in West Woodlawn in significant numbers between 1914 and 1940. By 1950, it was a majority Black neighbourhood. West Woodlawn offered Black Chicagoans one of the only alternatives to the conditions of overcrowding and squalor in the older Black neighbourhoods to the north. Influential figures in African American life have lived in West Woodlawn, including Lorraine Hansberry, playwright, the Civil Rights pioneer, Mamie Till Mobley, and Michele Obama, the partner of Barack Obama, a former US President. Most of the empty land in West Woodlawn appeared in the aftermath of 1968 and 2008. During the late-1960s and early-1970s, unrest after Martin Luther King’s assassination overlapped with the unemployment associated with deindustrialisation and led to declining property values, income instability, and many West Woodlawn homeowners lost their property, as their relative lack of wealth left Black Chicagoans in financial precarity. A similar cycle of disruption happened during the 2008 financial crisis. West Woodlawn homeowners found themselves behind on their mortgages, unable to pay real estate taxes, and underemployed.

Blacks in Green (known as BIG), led by Naomi Davis, a West Woodlawn resident, works within these open spaces and has formulated a strategy for reconstructing the neighbourhood as a self-sufficient ‘sustainable square-mile’ [26]. Founded in 2007, BIG emerged during the Great Recession and at the advent of the Obama presidency. In West Woodlawn, where BIG is located, this was a paradoxical moment. Foreclosures and bank failures, an everyday experience for the residents of West Woodlawn, happened alongside an outpouring of joy and optimism as a neighbour, Barack Obama, who lived less than two miles north of the community, became the first Black US president. A sense of desperation, of extreme precarity, driven by the sense that the neighbourhood would evaporate, existed alongside hopeful astonishment at Obama’s electoral victory. This combination of an expansive possibility and a real fear of obliteration shaped BIG’s mission, which is ‘designed, driven, managed by residents, supported by allies across the bounds of race and class’, and intends to ‘close the racial health and wealth gap by stopping displacement, supporting new models of home-ownership, and creating neighborhood-based green economies’ [27]. While this language carries with it the influence of the self-help, separate-but-equal philosophy of Black uplift derived from Booker T. Washington’s ‘Atlanta Compromise’, along with a small dose of New Urbanism, the organisation operates through more radically disruptive means tied to the legacies of segregation. Early support from the Natural Resources Defense Council, an international NGO focused on environmental advocacy, helped develop a handbook of the organisation’s principles and practices, which are explicitly modelled on the ‘Great Migration’ neighbourhoods described in Black Metropolis, in 2017.

Figure 6

West Woodlawn map, 20212. Prepared by Grimes et al. Based on the City of Chicago Vacant Land Inventory and a survey of the neighbourhood.

The first step of BIG’s model of reconstruction is the occupation, through a variety of means, of the neighbourhood’s abandoned properties, which pervade the neighbourhood (Figure 6). Working with other non-profits, foundations, and local government, along with a network of architects, landscape architects, contractors, and suppliers, BIG is building a neighbourhood-scale green infrastructure designed to manage stormwater, improve air quality, and provide summer cooling. Eventually, the infrastructure will also accommodate a community solar network and other neighbourhood assets. This work is incremental, pragmatic, and opportunistic, staying within while pushing against, various legal constraints, operating in a manner that is both informal and improvisational, repurposing waste from corporate developers, and starting seedlings in neighbours’ basements. One objective of this approach is to remove the vacant lots from the conventional development market, a strategy which has a time constraint as land values are increasing with the advent of gentrification driven by the University of Chicago, which is located alongside the eastern edge of the neighbourhood. Other work includes rescuing vacant buildings to house the organisation’s activities and preserve the neighbourhood’s heritage. All these properties will become part of a community land trust controlled by residents. Affordable homeownership and local business are at the core of this vision of a sustainable square mile, but these wealth-building tactics are outside the frameworks of a conventional neoliberal understanding of markets and rely upon the failure of these markets.

The simultaneous failure of private markets and public agencies has produced a peculiar opportunity to operate outside the typical market development on one side and the subsidised bureaucracy of government projects on the other. The vacant land that racist policies and practices left behind in West Woodlawn has opened a new possibility for Black Chicagoans to re-occupy and reconstruct the neighbourhood in a manner that recasts its origination in the speculator’s grid. This is not a return to the indigenous past. It is a restructuring of the possibilities and capacities of the remnants of a nineteenth- and twentieth-century urban fabric to sustain the lives of its inhabitants through the disruptions of climate change. Blacks in Green’s ‘Sustainable Square Mile’ has adopted a radicalised form of sustainability that depends on something Fred Moten calls ‘Black optimism’, which

persists in thinking that we have what we need, that we can get there from here, that there’s nothing wrong with us or even, in this regard, with here, even as it also bears an obsession with why it is that difference calls the same, that resistance calls regulative power, into existence, thereby securing the simultaneously vicious and vacant enmity that characterises here and now, forming and deforming us [1: p. 1747].

Moten formulates this notion of ‘Black optimism’ in a short essay on the paradoxical position of Black studies in universities that hinges on the distinction between blackness and things and people called Black. He argues that Black Studies must engage blackness and

extend and deepen its critical and imaginative relation to the terms abolition and reconstruction in a genuine, fundamental, fantastic, radical collective rethinking of them that will take into their account their historical ground while also propelling them with the greatest possible centrifugal force into other, outer space. [1: p. 1745]

In a recent lecture to architecture students at MIT, he makes it clear that this distinction and the possibilities for blackness in design practice are entangled with these same concerns [28]. He discusses AbdouMaliq Simone’s understanding of the ‘already insurgent sociality’ of Black urban life and goes on to ask architecture to locate places where ‘the emergence of the city as a zone of political control … is broken by its excesses.’

The work of Blacks in Green reflects its name, locating and dislocating blackness in the regimes of sustainability, in order to envision and enact a post-hydrocarbon future. It captures and appropriates the excesses of Chicago’s racialised real estate economy by planting hazelnut trees on abandoned properties and running an ‘Emergency Vegetable’ program at the end of the month when public assistance checks run out. BIG advocates for carbon abolition and neighbourhood reconstruction by envisioning, planning, and slowly building a neighbourhood to create a kind of mutual self-sufficiency, where going off the grid means joining a community solar network, where supporting yourself means weatherising your neighbour’s building, and where owning your home means joining a collective.

Environmental justice as a radical liberatory practice

BIG’s work aligns with other environmental justice frameworks such as the Just Transition, but it operates through an understanding of the distinctive optimism Drake and Cayton discovered in Black Metropolis, characterised by Wright as ‘unrest, longing, hope’ [4: p. xxv]. The histories and traditions of land stewardship brought to Chicago during the ‘Great Migration’ carry with them the unfinished project of the structural changes in American law, markets, culture, and social life, that were initiated in 1865 at the end of the Civil War, but eventually abandoned a decade later, along with the unrealised promise of reparations for slavery, also pledged at the end of the same war. For BIG, the work of environmental justice is a liberatory project, a reconstruction of the radical promises of emancipation and reparations requiring carbon abolition and the radical reintegration of economies and ecologies, work can only be accomplished by ‘being otherwise’ [1: p. 1747].

The ‘Great Migration’ transformed Chicago’s demographics and culture in a manner that was more profound than cities like New York and Los Angeles. Black populations in Los Angeles and New York never came close to becoming a majority, but that happened in Detroit and very nearly happened in Chicago. Dominated by people from Alabama and Mississippi, places where racial segregation and exploitation were especially fierce, and paradoxically, ties to these places were especially strong and maintained over generations, Black communities in Chicago and Detroit maintained traditions of land stewardship and mutual support that had emerged in sharecropper settlements after the Civil War. Chicago distinguished itself from Detroit as the site of the earliest academic departments of sociology at the University of Chicago, which studied (and often misunderstood) the transformative effects of the ‘Great Migration’ on Chicago. At the same time, local businessman Julius Rosenwald endowed the Rosenwald Fund which distributed hundreds of grants that supported PhD studies for Black scholars, including both Drake and Cayton. When Richard Wright asserts Chicago’s status as ‘the city from which the most incisive and radical Negro thought has come’ at the opening of their book, he locates that idea in the city’s ‘extremes of possibility’ [4: p. xvii].

Chicago is the city of the speculator, of the political operative, of the urban scientist, where certain neighbourhoods are understood as plastic grounds for the consolidation of power and influence, where voids in the urban fabric appear as countless artifacts of bias and exploitation, all forms of nothingness given pseudo-necessitarian labels. But it is also a ‘Black Metropolis’ where other, fugitive forms of urban life operate through and around these norms, reconstructing the promises of freedom, familiar with the processes and disruptions of abolition.

Acknowledgements

This work is indebted to the people who make up BIG, especially Nuri Medina, Suzanne Waddell, Amandilo Cuzan, Gwen Pruitt, and David Yocca. My most profound gratitude is for the visionary leadership and determination of Naomi Davis, BIG’s founder.

Competing Interests

The author has worked as a pro-bono consultant to Blacks in Green.