1 Introduction

Music question–answering (MQA) is a computational task where machine learning models analyze music‑related data to answer questions about their content (Gao et al., 2022; Li et al., 2022). While MQA is a recent development in machine learning, its fundamental approach— analyzing and interpreting music through structured questioning—aligns with established musicological methods. Various musicological subdisciplines have employed systematic questioning to examine musical structures, performance practices, and cultural contexts, providing relevant frameworks for computational music analysis (Bader, 2018).

Music information retrieval (MIR) also relies on structured analysis to extract information from musical data. While MIR has traditionally focused on symbolic and audio‑based analyses, advances in natural language processing have introduced audio–language processing, enabling automatic music captioning (Manco et al., 2021) and music question–answering (Gao et al., 2022; Li et al., 2022).

There have also been attempts at bringing embodied approaches to the MIR community (Godøy and Jensenius, 2009; Müller et al., 2010), acknowledging that the human body and various bodily processes are essential to understanding more about human perception, cognition, and behavior. In music research, this has been articulated in multiple theories of ‘embodied music cognition’ (Clarke, 2005; Leman, 2007) and numerous studies of ‘musical gestures’ (Gritten, 2006; Godøy and Leman, 2009; Gritten et al., 2011).

The multimodal nature of human perception and cognition is at the core of most embodied (music) cognition theories (Gibson, 1979). From a psychological perspective, multimodality refers to the fusion of multiple sensory modalities (auditory, visual, etc.) as part of cognitive processes (Clarke, 2004). The term ‘multimodality’ is nowadays also used in computer science, often describing the deliberate integration of supplementary information sources—such as audio, video, and text— tailored to specific tasks (Christodoulou et al., 2024). Thus, multimodality refers to a similar information fusion in both humans and machines, although we should not confuse the two. Therefore, in this paper, we will use audio/video to refer to data types and auditory/visual to refer to human perception and cognition.

MQA models adopt a multimodal approach, fusing audio, video, and language (Li et al., 2022; Duan et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2024), enabling computational systems to process a broader range of musical elements. These developments are important for improving the computational analysis of music performance and advancing computational models of music understanding. Despite recent advancements, several challenges remain. For example, some rely on audio‑language analysis (Gao et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2024a), omitting the visual cues essential to music performance understanding. Many multimodal MQA systems often focus on scene description (‘the first sounding instrument is on the left’) and instrument detection (‘a guitar’), ignoring aspects of music performance analysis such as a musician’s sound‑producing actions and communicative gestures, their stage presence, or the audience’s engagement. The focus is often on ‘what’ is happening in a video rather than ‘why,’ omitting causal reasoning about performance choices, acoustics, and spatial relationships.

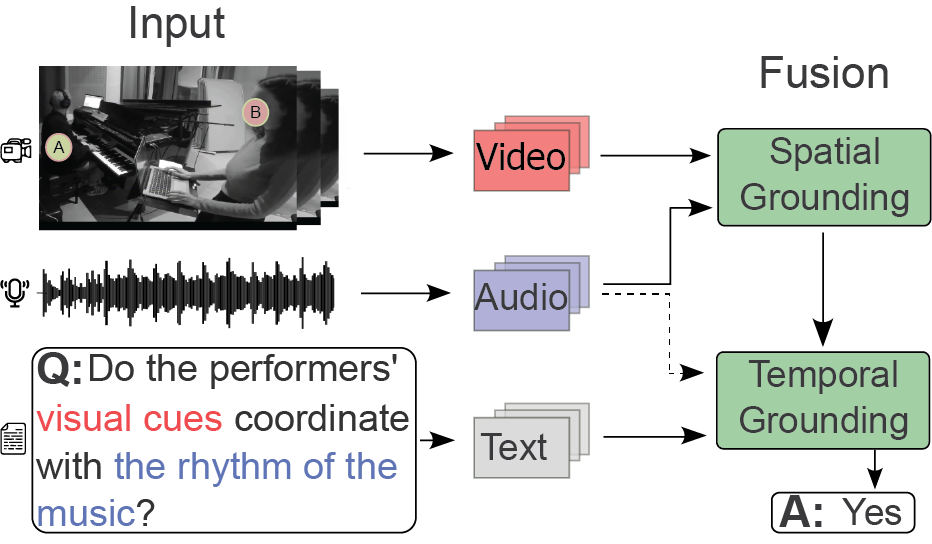

This paper introduces MusiQAl, a multimodal (here, meaning the combination of audio, video, and text) dataset designed to support research on music performance question–answering. Figure 1 illustrates how an MQA model outputs an answer based on features extracted from audio and video files. In this paper, we use the term ‘music performance video’ to refer to video recordings (with audio) of live or staged music performances. These recordings are a combination of videos made for research purposes and ‘music videos’ designed for artistic or promotional purposes.

Figure 1

Overview of the music question–answering system. Features from input data (video, audio, and text) are processed and spatiotemporally mapped (grounded) through the AVST/LAVISH model to generate an answer (A).

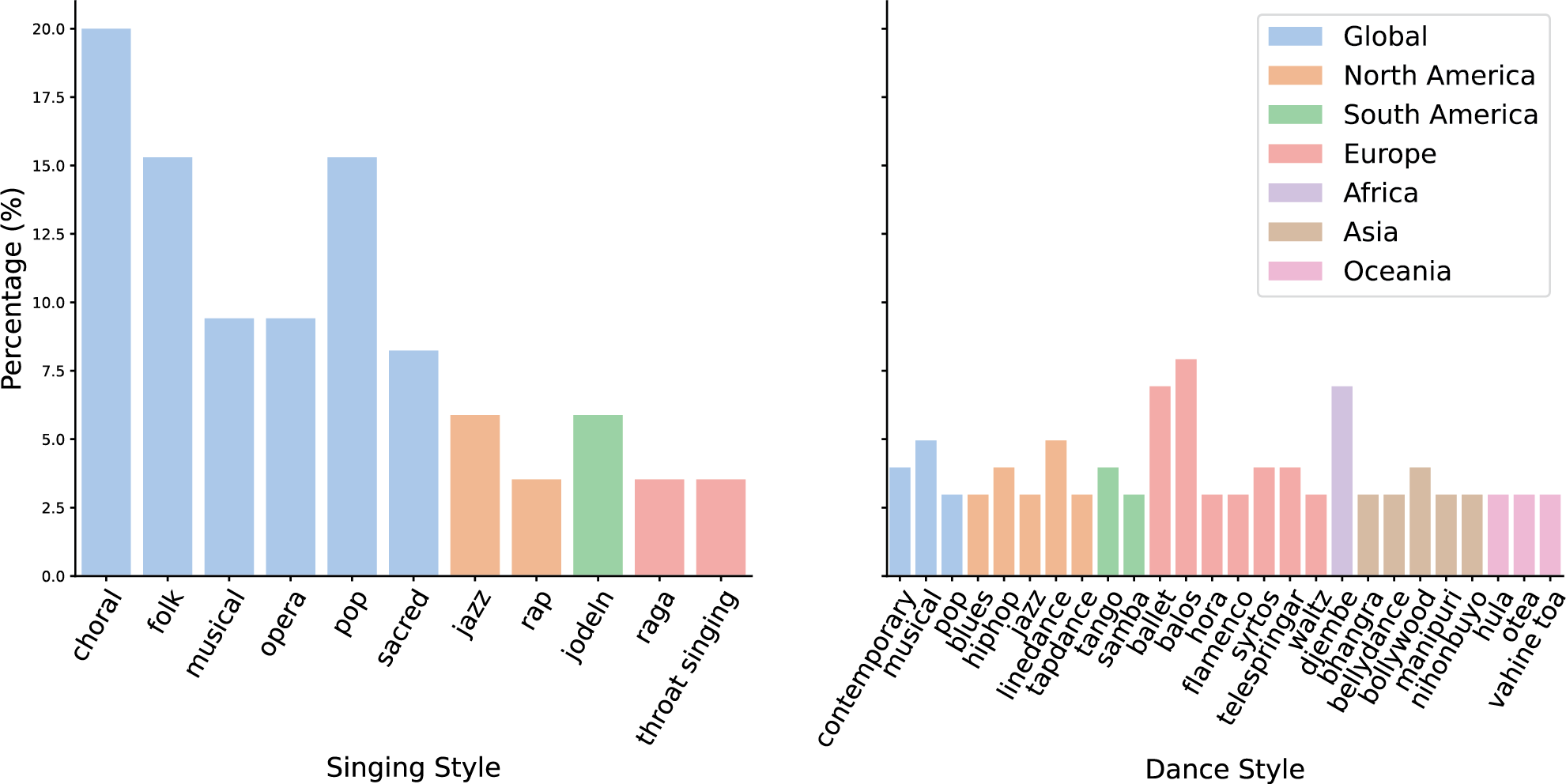

A second objective of our work is to provide a dataset that addresses the missing diversity in many existing models and datasets. Previous studies have raised concerns about genre bias and representational limitations in MIR (de Valk et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2023), something which is also seen in the current repository of ISMIR’s community resource of MIR datasets.1 MQA datasets are no exception. Many of them are created through large‑scale crowdsourcing or using large language models (LLMs), often resulting in challenges related to ambiguity, inconsistency, and various types of bias. MusiQAl includes various musical styles from diverse geographic regions, covering practices such as jazz, raga, djembe rhythms, and Polynesian dance (Figure 2). The collection also includes instrumental and vocal performances, dance, and integrated “music–dance” forms, where music and movement are inseparable (Haugen, 2016). This allows for investigating how musical diversity influences the accuracy and relevance of generated answers in MQA systems.

Figure 2

Distribution of singing (left) and dance (right) styles by geographic origin. Styles are listed on the x‑axes, with y‑axes showing their corresponding linear percentage (%). Bar colors denote geographic origin (see legend). The presented style taxonomies and regional annotations were curated by the authors for this study.

Third, we focus on designing questions that improve the alignment of MQA systems with real‑world knowledge and performance practices. The expert annotators of our dataset have backgrounds in musicology, music psychology, and music technology to ensure question–answer pairs informed by established theories and previous work. This makes MusiQAl grounded in how humans understand and interpret music in performance contexts. We test state‑of‑the‑art MQA models to see how well they answer our questions while also studying our dataset to find its strengths and weaknesses.

Through these contributions, we aim to improve computational music understanding by integrating multimodal learning with musicological knowledge. By grounding our dataset in real‑world music practices and diverse genres and performance styles, we hope to support both computational modeling and music research.

2 Background

2.1 Music understanding

In this paper, by ‘music understanding,’ we denote the multiple perceptual, cognitive, and cultural processes that allow humans to recognize music patterns, apply reasoning, and infer deeper meanings beyond the surface‑level features of sound. One key challenge in MQA is developing systems that mirror these capabilities. This section explores how insights from musicology and music psychology connect human and computational music understanding, focusing on multisensory perception, embodied cognition, and cultural context to enhance MQA systems.

Research shows that sensory modalities work collaboratively in the brain to process information, highlighting that multisensory integration is fundamental to human perception (Shimojo and Shams, 2001). From perceiving music‑related auditory and visual information to understanding a music performance, cognition plays a crucial role by combining multisensory inputs with thought, reasoning, and lived experience. Theories of embodied cognition further enhance this process, emphasizing how body motion, gestures, and other sensorimotor interactions contribute to the cognitive processing of music. These embodied interactions enhance expressivity and emotional impact, influencing both performers and their audience (Jensenius, 2007; Godøy and Jensenius, 2009; Moura et al., 2023).

One example of a question that cannot be adequately answered without an embodied and multimodal approach could be: ‘Do the harpist’s gestures communicate the emotion of the music?’ Suppose this question is posed to a performance video of an orchestra with a harpist. One must pay attention to the harp’s sound and the harpist’s visual location on stage (in the video), disregarding other instruments and performers. This process involves synchronizing auditory and visual attention, facilitating a more precise understanding of the harpist’s playing while also engaging reasoning to interpret the emotional connection between body motion and sound.

Finally, cultural references are essential for understanding music, and cross‑cultural sensitivity is needed to interpret a performance within its cultural context. Various cultures use music in different—sometimes unique—ways. Meaning‑making in music often relies on recognizing cultural nuances and genre‑specific norms. Without explicit knowledge about the cultural context, it may not be easy to understand a performance’s symbolic layers.

2.2 Machine perception and cognition of music

In machine learning, the concept of sensory modalities does not apply the same way it does in human perception. Instead of multisensory integration, there is multimodal fusion, where supplementary information from diverse data types, such as audio, video, text, or motion capture, are combined. In this context, ‘perception’ refers to transforming input signals—typically digitized based on continuous physical signals, such as sound and motion—into structured internal representations that machines can process.

The ability of machines to ‘understand’ music is more closely aligned with human cognition, which involves higher‑level functions like reasoning and decision‑making. This process allows machines to perform tasks that require human‑like capabilities, such as interpreting complex musical content. A key component of this process is using models such as transformer‑based attention mechanisms (Vaswani et al., 2023), which enable machines to prioritize key musical features and filter out irrelevant data, replicating human‑like selective attention for multimodal interpretation.

‘Embodiment’ in machine learning refers to how computational systems engage with their environment through sensorimotor processes. This interaction is similar to how humans use their bodies to process and understand the world. Just as humans rely on their sensory modalities to understand music, embodied machine learning systems use a fusion of sensory data to develop a deeper understanding of music performances. For example, for the question, ‘Do the harpist’s gestures communicate the emotion of the music?,’ the model must process several inputs: the audio features extracted from the sound of the harp, the video features extracted from the visual region where the harpist is located, and the motion features extracted from the video. Similar to how humans synchronize auditory and visual cues to interpret musical gestures, a machine learning system would need to fuse audio and video data from multiple sources to form a representation of the performance.

In this scenario, the system must also engage attention and reasoning capabilities. For example, it would need to focus on the relevant points in space and time to detect the correct instrument and sound. It would also need to infer the emotional connection between the harpist’s gestures and the sound produced, recognizing patterns in the performer’s motion and correlating them with the mood of the music. These higher‑level cognitive functions are crucial for creating accurate, contextually aware answers, just as is the case for humans.

Context also plays a critical role in helping machine learning systems understand music. The context in which music is performed—such as cultural traditions, musical genre, and performance environment—provides essential background information that enriches the interpretation of music.

In the context of MQA, data diversity—such as varying musical styles, geographic regions, and cultural traditions—can help machine learning systems develop cross‑cultural understanding. For example, an MQA system trained on diverse musical cultures expands its frame of reference for interpreting performance questions. This diversity allows the system to make more nuanced interpretations of music.

3 Previous Work

This section explores previous studies that have laid the foundation for and advanced the integration of audio–video data in audio‑visual tasks, including MQA.

3.1 Music question–answering models

3.1.1 Audio‑visual spatio‑temporal (AVST)

The AVST model pioneered the use of audio and video data to answer spatial‑temporal questions in music (Li et al., 2022). This model enhances the synchronization of sounds and visual elements by assigning attention to video regions based on corresponding audio inputs, effectively localizing audio sources. It features spatial and temporal grounding modules that adapt to changes in auditory and visual information, allowing for accurate question‑answering. The integration of motion features further boosts the model’s baseline performance (by 1%), demonstrating its capability to handle dynamic music scenes.

3.1.2 Latent audio‑visual hybrid (LAVISH)

The LAVISH adapter developed by Lin et al. (2023) uses vision transformers to enhance audio–video question– answering. By modifying pre‑trained transformers with trainable parameters, LAVISH effectively fuses audio and visual inputs, improving performance across single‑ and multimodality tasks without needing to retrain large models from scratch. This demonstrates the potential of vision transformers in achieving cross‑modal integration.

3.1.3 Dual‑guided spatial‑channel‑temporal (DG‑SCT)

The DG‑SCT model by Duan et al. (2023) dynamically adapts pre‑trained audio and video models to enhance multimodal interactions, mitigating the challenge of irrelevant modality information during encoding. This model leverages the strengths of large‑scale audio and video models to refine task‑specific features through detailed cross‑modal interactions, improving the execution of complex audio–video tasks.

3.1.4 Spatial–temporal–global cross‑modal adaptation (STG‑CMA)

The STG‑CMA model by Wang et al. (2024) adapts pre‑trained image models for audio–video tasks. By extending self‑attention layers to process sequential data and employing an audio–video adapter for cross‑modal attention, this model effectively integrates spatial and temporal features, enhancing the understanding of complex audio and video information. This approach enables nuanced and accurate processing of multimodal music data.

3.1.5 Audio‑visual LLMs (AV‑LLMs)

Gemini Pro 1.5 (Team, 2024) and VideoLLAMA 2 (Cheng et al., 2024) are AV‑LLMs designed to process and generate multimodal content, including audio, video, and text. These models have shown remarkable capabilities in various tasks. However, challenges remain, including issues with accessibility, computational demands, and transparency.

3.2 Music question–answering datasets

Datasets are crucial for evaluating multimodal understanding and spatio‑temporal reasoning capabilities in computational systems. This section presents previous MQA datasets, highlighting their strengths and limitations.

3.2.1 MUSIC‑AVQA

The MUSIC‑AVQA dataset (Li et al., 2022) is designed to facilitate research into queries about visual objects, sounds, and their associations in music performance videos. It features 9,288 YouTube‑sourced videos of solo and ensemble performances, standardized to a one‑minute duration for consistent analysis. It includes 45,867 question–answer pairs gathered through human crowd‑sourcing. It uses 33 question templates (Appendix) to cover nine categories across audio, video, and audio–video data. These categories, further detailed in Section 4.2, probe diverse aspects of musical performance—from existential and locational queries to counting, comparative, and temporal analyses—thereby supporting an examination of how models integrate and interpret dynamic, multimodal information by testing their ability to handle complex spatio‑temporal relationships and interactions between audio and video content in instrument performance settings.

3.2.2 MUSIC‑AVQA‑v2.0

MUSIC‑AVQA‑v2.0 addresses biases in the original dataset’s question distributions (Liu et al., 2024b). It enhances the diversity of audio–video contexts by addressing biased question distributions and incorporating 1,230 new videos and over 8,100 new question–answer pairs. These additions cover various musical scenarios, including videos with three or more instruments, facilitating more nuanced multimodal reasoning.

3.2.3 MusicQA

The MusicQA dataset offers 112,878 open‑ended questions by combining data mainly from MusicCaps (Agostinelli et al., 2023) and MagnaTagATune (Law et al., 2009). Focused on emotion, tempo, and music genre, it uses LLMs for question–answer generation, contributing a rich repository specifically for music understanding in multimodal models like MU‑LLaMA (Liu et al., 2024a).

3.2.4 MuChoMusic

MuChoMusic is a dataset that evaluates machine understanding of 644 music tracks with 1,187 multiple‑choice questions (Weck et al., 2024). Each question presents four answers—one correct and three distracting—to test a model’s ability to differentiate subtle musical concepts. Questions are divided into knowledge categories (covering musical elements like melody and rhythm) and reasoning categories (focusing on mood and lyrics analysis). Distraction choices (incorrect but related, correct but unrelated, incorrect and unrelated) challenge models to select correct responses while navigating plausible alternatives accurately. All questions and answers are generated by LLMs and validated by human annotators to ensure reliability and quality.

3.3 Dataset limitations

While MusicQA and MuChoMusic mark significant progress in music question–answering, they have several limitations. Subjectivity in emotion and mood‑related questions often leads to varied interpretations, and their audio‑only focus limits the ability to analyze visual performance cues such as stage presence, gestures, and performer interactions. Many aspects of live performance remain unaddressed, including audience engagement and performance dynamics. Additionally, randomly sourced data introduce inconsistencies, unwanted biases, and diversity issues.

Using LLMs to generate question–answer pairs introduces additional challenges. These models rely on limited examples and chain‑of‑thought reasoning, often producing overly generic, ambiguous, or unreliable outputs. They also exhibit ‘auditory hallucination’ (describing non‑existent sounds) and ‘language hallucination’ (introducing irrelevant statements) (Weck et al., 2024). Biases in training data further lead to speculative responses padded with qualifiers like ‘likely’ or ‘probably,’ undermining reliability.

The MUSIC‑AVQA and MUSIC‑AVQA‑v2.0 datasets provide a foundation for audio–video question– answering, but their focus remains primarily descriptive, prioritizing instrument recognition over other performance aspects. They are also skewed by covering mainly instrumental performances, overlooking singing, and dancing. Additionally, synthetically generated instrument combinations, while useful for dataset expansion, make the models less adaptable to real‑world performances.

Both MUSIC‑AVQA and MUSIC‑AVQA‑v2.0 lack detailed tracking of performer motion, ensemble interaction, and the importance of the spatial arrangement of performers. Existing methods recognize instruments and sound locations but fail to analyze how musicians interact on stage, how gestures align with musical phrasing, or how audience reactions shape performances. The absence of causal reasoning further limits understanding. Questions tend to focus on what is happening rather than why, neglecting factors like acoustics, the venue’s visual appearance, spoken segments, or interactive elements.

Expanding these datasets to encompass diverse performances and multimodal interactions would enhance their depth and applicability, better aligning MQA research with human music cognition for a richer understanding of musical performance.

4 The MusiQAl Dataset

The MusiQAl Dataset consists of 310 videos, totaling more than five hours of music performance footage, associated with 11,793 question–answer pairs.

4.1 Music performance videos

We propose MusiQAl to advance MIR research with a diverse collection of instruments, performance styles, and settings. It will enhance music question–answering and cross‑cultural analysis and address the biases and narrow representations detected in previous work.

Our sources include the Malian Jembe recordings from the Interpersonal Entrainment in Music Performance (IEMP) dataset (Polak et al., 2018), a classical string quartet from the MusicLab Copenhagen concert (Høffding et al., 2020), and Hanon exercises—a series of piano finger exercises designed to improve technique, strength, and agility—in the HanonHands dataset (Pilkov et al., 2024). These recordings originate from controlled research settings, ensuring audio and video are optimized for analysis. Other sources include the Greek Folk Music Dataset (GFMD) (Christodoulou et al., 2022) and AudioSet (annotated YouTube clips of music performances) (Gemmeke et al., 2017), as well as curated YouTube videos. These videos were manually selected by the first author and two research assistants and, to avoid search bias, they were searched using incognito mode with targeted keywords. Keywords included: instrument name, using the instances presented in Table 1, followed by either ‘solo,’ ‘ensemble,’ or similar (e.g, group, orchestra, band); dance style or singing style, as presented in Figure 2, followed by either “solo”, “duet”, “ensemble”, or similar (e.g., group, choir) performance; and country name (when relevant). All videos were manually reviewed for relevance, ensuring minimal noise interference and frame changes.

Table 1

The instrumental categories in MusiQAl.

| Strings | Winds | Percussion | Keyboards | Other | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Banjo | Bass | Bassoon | Clarinet | Bell | Castanets | Accordion | Computer |

| Cello | Double Bass | Euphonium | Flute | Djembe | Drum | Piano | Steps |

| Cretan Lyra | Fiddle | Horn | Pipe | Drums | Dundun | Synthesizer | Voice |

| Guitar | Harp | Saxophone | Trombone | Glockenspiel | Kenong | Clap | |

| Koto | Laouto | Trumpet | Tsabouna | Kenong | Saron | ||

| Outi | Qanun | Uilleann Pipe | Whistle | Shaker | Tabla | ||

| Sitar | Violin | Taiko | Tambourine | ||||

| Tympani | |||||||

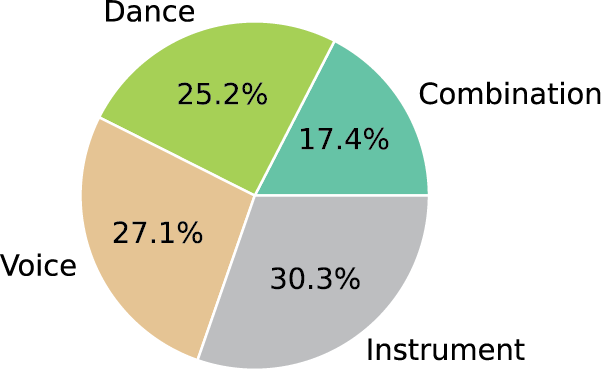

The videos included in MusiQAl are split between different groups (Figure 3), including:

98 videos of purely instrumental performance, including 36 solos, 14 duets, 29 ensembles of the same instrument (e.g., flute ensemble), and 17 ensembles of different instruments (e.g., orchestras)

87 videos of vocal performances (either a cappella or with background music), including 25 voice solos, 18 duets, and 44 vocal ensembles

76 videos of dance performances (with background music), including 21 dance solos, 14 duets, and 41 dance ensembles

49 videos of performances combining either instrumentalists and singers, instrumentalists and dancers, singers and dancers, or the three groups together

Figure 3

Data distribution by performance type in MusiQAl.

MusiQAl features performances involving 47 musical instruments (Table 1), ensuring broad instrumental coverage that supports the study of diverse timbral, harmonic, and performance characteristics. The collection comprises various non‑conventional musical instruments, including rhythmic footsteps in flamenco and traditional Irish music. It also features live electronics, such as laptops used in live coding, self‑playing guitars, and robot glockenspiels. While the self‑playing guitars and robot glockenspiels may not feature the human or robotic gestures typically seen in more conventional musical performances, they were included to reflect the increasing role of technology in contemporary music practices. Self‑playing guitars, for instance, may be used in algorithmic music performances, and robot glockenspiels may feature pre‑programmed actions. Such machine performances offer interesting visual cues, such as the motion of guitar strings or robot parts. These examples highlight various visual aspects relevant to music analysis, even in technologically advanced, machine‑centered performances.

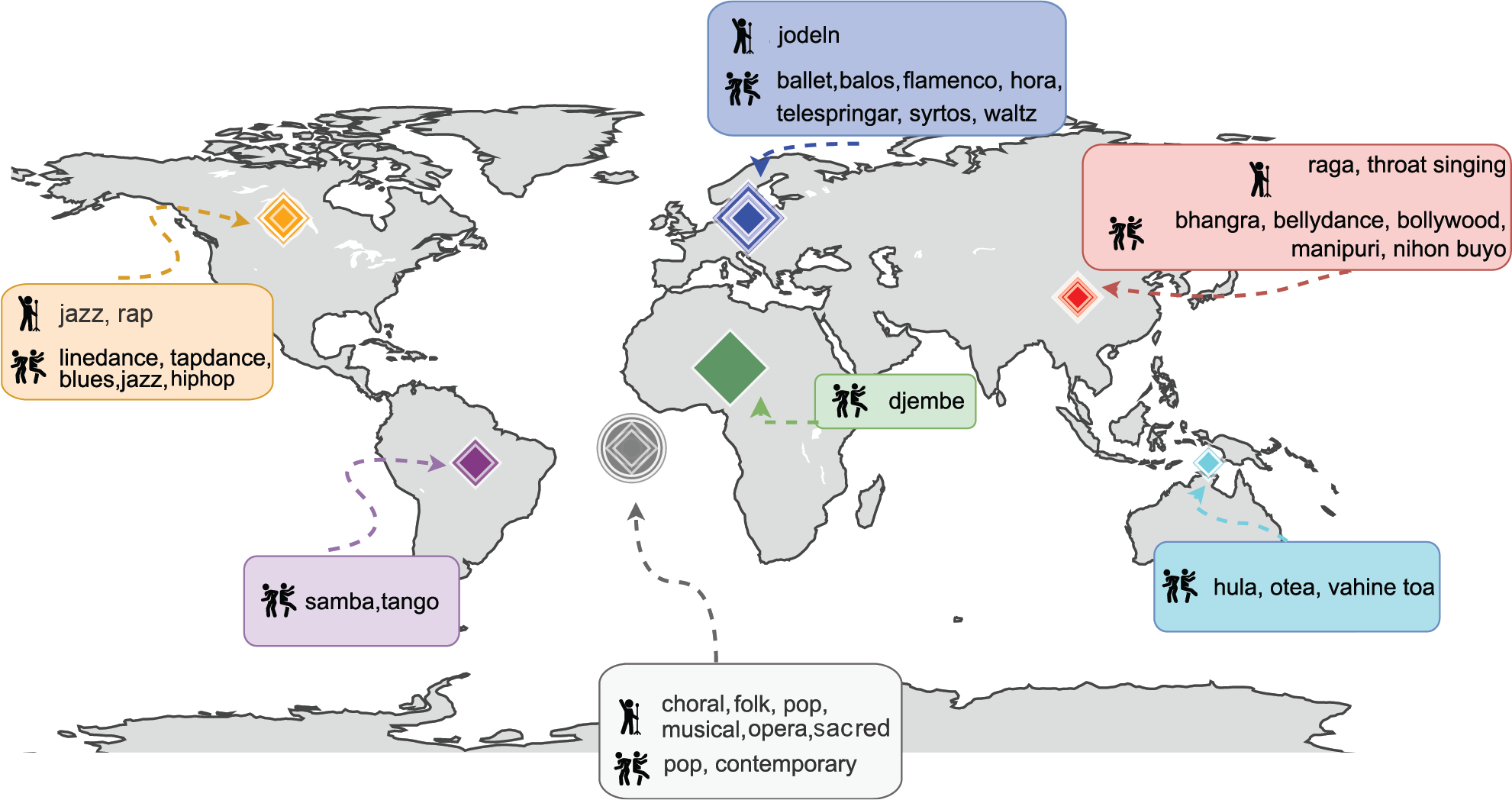

The videos in MusiQAl represent recordings made in 18 countries across five continents, offering a broader, globally representative music question–answering collection (Figure 4). While the selection is not exhaustive, this approach aims to ensure a more inclusive representation of both widely recognized and historically underrepresented musical genres, supporting advancements in cross‑cultural music analysis.

Figure 4

Overview of singing styles and dance types in MusiQAl, along with their countries of origin. The symbol in the center of the map denotes global data.

Global singing traditions, including choral, folk, and pop, compose 77.65% of the vocal performances. In contrast, North American jazz and rap account for 8.8%, Asian vocal traditions contribute 7.06%, and European styles such as yodeling make up 5.88%. Similarly, dance styles are drawn from a broad geographic spectrum. European traditions like flamenco and waltz represent 31.68%, while North American (17.82%), Asian (15.84%), and global (11.88%) forms—including balos, blues, rock ‘n’ roll, bhangra, and Manipuri—highlight the diversity of movement‑based performances. Oceanian (8.91%), African (6.93%), and South American (6.93%) styles, such as djembe, hula, otea, tango, and samba, provide additional cultural depth. A more detailed distribution is presented in Figure 2.

MusiQAl is designed to capture four key aspects of music performance: instrument‑playing, singing, dancing, and their combinations. The inclusion of singing and dancing traditions in MusiQAl aligns with research on multisensory integration, where body movement can enhance rhythm perception (Schutz, 2008), and on spatial perception in music cognition (Gibson, 1979). By including a variety of performance contexts—including formal concerts, folk parades, street performances, school musicals, operas, and ‘do‑it‑yourself (DIY)’ home covers—the dataset reflects the relationship between music and movement across different cultures, including ritualistic, theatrical, and social traditions. This approach also extends the applicability of MIR into areas such as auditory–visual synchronization and expressive gesture analysis within dance and performance studies.

4.2 Questions

We introduce new questions that integrate perspectives from musicology and music psychology to enhance machine understanding of musical performances.

4.2.1 Description of questions

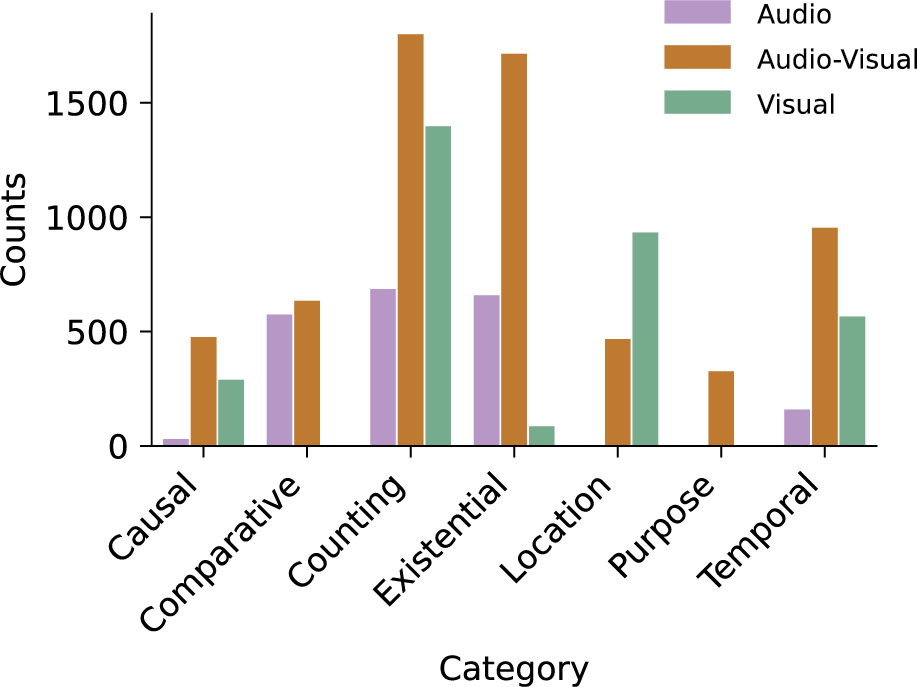

MusiQAl includes the five question categories proposed by Li et al. (2022), as well as the two categories proposed by Yang et al. (2022) (Table 2), and covers three modalities: audio‑only, video‑only, and audio–video (Figure 5). We used the 33 question templates in MUSIC‑AVQA and created 47 new ones, resulting in 80 questions (Appendix). The question templates provide structured formats for generating consistent and adaptable questions. They use placeholders (e.g., Object, Instrument, LR) that can be replaced with context‑specific terms, ensuring scalability across different videos. Some templates allow multiple substitutions, while others are fully formed questions.

Table 2

Overview of the question categories present in four former music question–answering datasets compared to MusiQAl.

| Dataset | # Questions | A Questions | V Questions | AV Question | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Existential | Location | Counting | Comparing | Temporal | Causal | Purpose | ||||

| MusicQA (Liu et al., 2024a) | 112K | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| MuChoMusic (Weck et al., 2024) | 1.1 K | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| MUSIC‑AVQA (Li et al., 2022) | 45K | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| MUSIC‑AVQA‑v2.0 (Liu et al., 2024b) | 53K | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| MusiQAl | 12K | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

[i] The questions can be based on audio (A), video (V), or both audio and video (AV).

Figure 5

Distribution of question categories in different scenarios. The count of questions (y‑axis) per category (x‑axis) for each modality (audio–video, audio‑only, and video‑only).

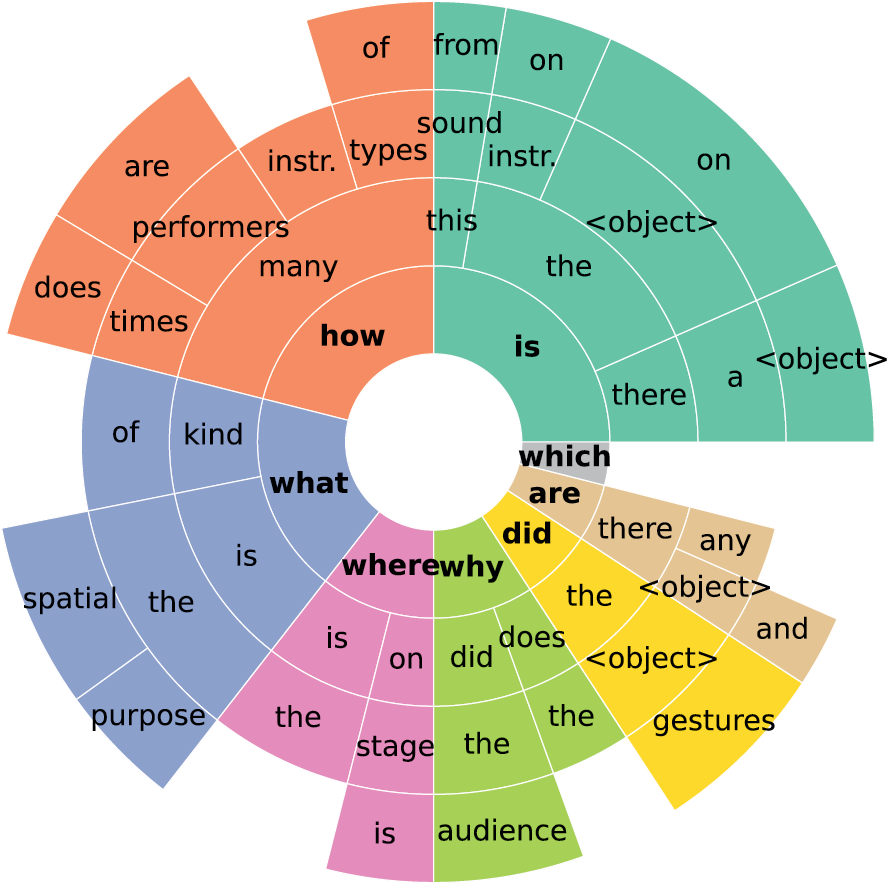

Figure 6 provides an overview of the question categories in the MusiQAl dataset, visualizing the distribution of word sequences at the start of questions via N‑gram analysis. The plot displays the frequency of different word sequences (up to four words, or N‑grams) at the beginning of questions. The innermost ring represents the most frequent first words, with arc length proportional to frequency. Subsequent rings show common continuations, illustrating how words tend to follow one another in question formation. This helps identify dominant question structures and supports our classification of questions into seven main types, while deepening our understanding of the underlying question templates.

Figure 6

N‑gram analysis of question formulation. This plot shows the frequency of common word sequences (up to four words) at the beginning of questions, revealing dominant patterns in question formulation.

Existential questions

Previously, questions in this category focused on matching sounds to on‑screen instruments and determining whether a specific musical element remains present throughout the video. We have expanded this category to determine the performance type (instrumental, singing, or dancing), differentiating the roles and interactions of performers based on their artistic contributions. We introduce questions on emotional expression through gestures, building on research that underscores body language’s critical role in shaping music perception and emotional interpretation in performance (Davidson, 2005; Vines et al., 2011). Furthermore, we include questions related to classifying dance and singing styles, building on the understanding that genre classification relies not only on audio features but also on visual and contextual cues, as explored by Tzirakis et al. (2017). We also address the existence of ‘background’ elements, such as how environmental sounds, including audience noise and the room’s reverberation, contextualize performances and shape perceptions of realism and authenticity, as noted in previous work on ecological perception (Gibson, 1979) and the role of environmental context in music (Clarke, 2004). Performers frequently adjust their stage positioning to emphasize structural shifts, highlight solo sections, or interact with the audience, as highlighted by Dahl and Friberg (2007). We include questions related to tracking a performer’s position on stage, offering insight into the performance narrative.

Location questions

Previous questions focused on basic spatial orientation, such as identifying the left or right placement of instruments on stage in the video or determining whether the performance is indoors or outdoors. We have expanded this analysis to include performers’ arrangement and the audience’s positioning relative to the performance setup on stage in the video (around, in front of, or behind the performers). Research highlights the influence of a listener’s spatial position relative to the stage, which impacts how sound is perceived in live settings (McAdams et al., 2004). Our questions enhance spatial analysis beyond individual instruments, including ensemble coordination and performer–audience interactions. We assess the positioning of musicians on stage, which builds upon the concept of auditory scene analysis (Bregman, 1990). By tracking the movement of musicians during a performance, MQA models capture both the location of instrumental sounds and the performer’s motion over time. This is closely tied to studies that show how visual cues play a significant role in helping listeners anticipate musical structure (Davidson, 1993; Jensenius, 2007).

Counting questions

The original MUSIC‑AVQA questions primarily focused on counting instruments and detecting sounds. Our dataset includes counting how many performers play instruments, dance, or sing, and which voices sound throughout a performance. This addition ensures the model reflects the full range of music performance. Also, the previous questions overlooked critical aspects like temporal dynamics and performer interactions, neglecting the combined influence of auditory and visual cues on perceptions of timing and expression. Informed by auditory scene analysis (Bregman, 1990) and research on multisensory integration (Schutz, 2008; Lacey et al., 2020), our dataset includes questions related to tracking tempo changes and performer–audience interactions. An example question is ‘How many times did the performer visually interact with the audience?’ We define intentional visual cues as gestures, eye contact, or facial expressions directed at the audience, applying this question only in cases with a clear performer–audience distinction to ensure relevance while capturing performance engagement and communication strategies. This approach aims to capture the structural dynamics and engagement levels of music performances and expand beyond static object identification.

Comparative questions

Originally, these questions focused on comparing the rhythmicity and loudness of instruments on the left and right. Now, we ask more nuanced questions, such as ‘Did the object’s gestures correspond with the object’s fills?’ or ‘Do the performers’ visual cues coordinate with the rhythm of the music?’ These new questions track how bodily movements—such as hand gestures, head movements, and dance steps—align with musical structure. Instead of just detecting changes in sound, they examine how musicians and dancers use movement to highlight musical phrasing and expression. This aligns with previous research showing that body movements and visual cues help listeners process rhythm, phrasing, and expressive intent (Jensenius, 2007). Musical gestures—such as arm movements, bowing, and conducting— reinforce phrasing and structure (Davidson, 2005). MQA systems can better model musical expressivity, groove, and performer coordination by correlating performers’ gestures with their associated music and sound events.

Temporal questions

Previously, questions focused on sequencing instruments, such as which instrument plays first or last and which enters before or after another. Instead of only tracking instrumental entrances, the dataset now examines performance fluctuations in energy levels over time. Research on musical expressivity shows that dynamic shifts in lighting, stage effects, and performer movement help audiences track emotional intensity in live performances (Jensenius, 2007; Tsay, 2013). Additionally, musicians use expressive gestures that audiences perceive as integral to the musical message (Platz and Kopiez, 2012). By asking questions like ‘Did the object perform any visual actions?,’ we emphasize the role of bodily communication in music perception. These additions allow a more dynamic analysis of how performers interact over time rather than treating them as static entities.

Causal questions

With this category, we introduce new questions to music question–answering systems that explore causal relationships. One example is analyzing the cause of a spoken word segment in the middle of a song. Spoken word sections add narrative, emotional, or structural meaning, engaging both musical and linguistic processing (Patel, 2007). They signal shifts, dramatic changes, or intertextual references, shaping listener expectations (Huron, 2008). Other questions determine the reason behind performers’ attire–whether it reflects tradition, style, uniformity, or the use of motion capture technology. In live music, clothing is not arbitrary (Davidson, 2005), and it can signal genre, formality, or thematic intent. Having such questions, we aim to move beyond simple object recognition (e.g., identifying what the performers are wearing) to causal inference (e.g., understanding why they are dressed that way). Understanding attire helps infer whether a performance is formal, ritualistic, or part of a specific cultural tradition (Platz and Kopiez, 2012; Clayton, 2008). Additionally, we now examine causal relationships in other aspects of performance, such as why a performer is using a particular object, the reasons behind audience behavior (e.g., clapping or cheering), and how venue acoustics affect instrument placement and sound projection. Such questions reflect social cognition in music, where listener expectations and cultural norms influence responses to performance events (Huron, 2008).

Purpose questions

With this category, we aim to expand MQA beyond identification to understanding the intent behind musical, visual, and performative elements. Instead of simply recognizing props or sounds, we now ask about their function within a performance. Music cognition research highlights that music is a communicative act, integrating sound, movement, and visuals to convey meaning (Leman, 2007). Props, costumes, and visual elements act as semiotic tools, shaping audience perception and interpretation (Tagg, 2012). Many performances use these elements to reinforce themes and narratives (Cook, 1998). By exploring props’ aesthetic, narrative, or thematic functions, we aim to advance MQA from recognition to performance semiotics.

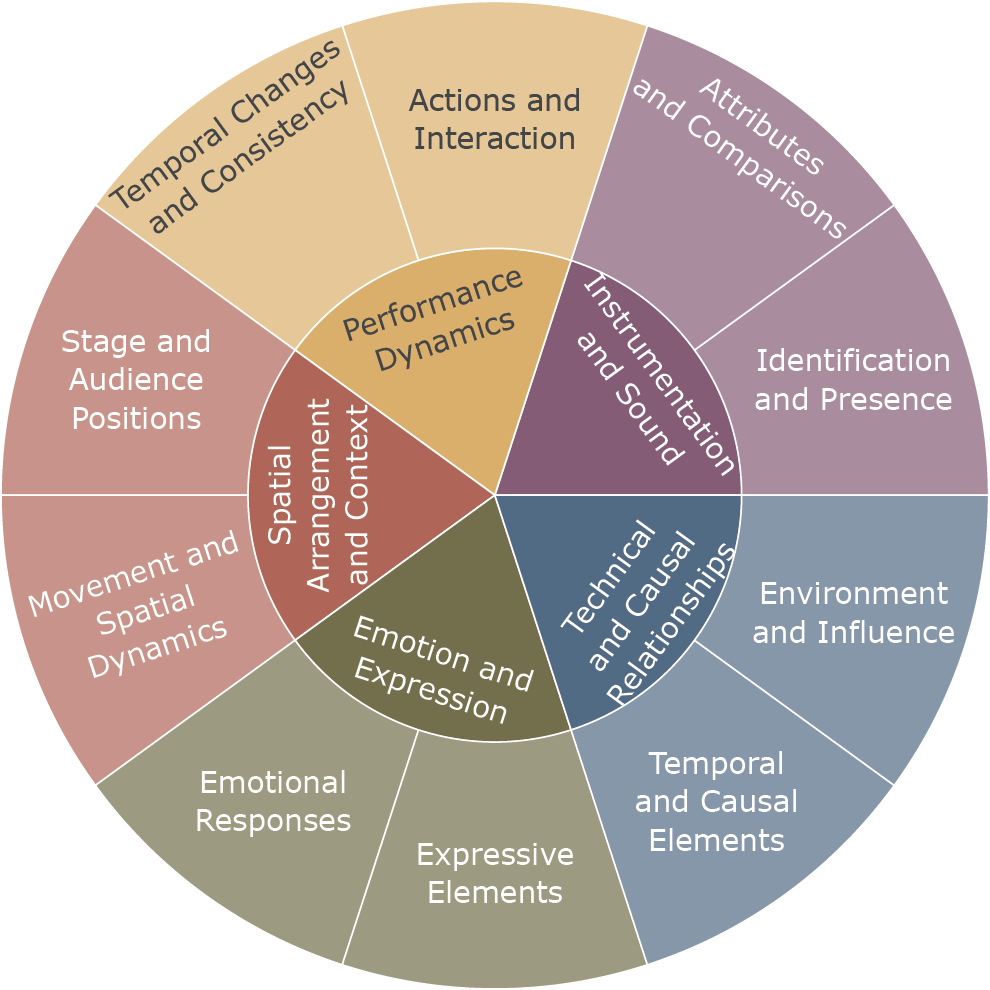

To illustrate the scope of our new questions and their connection to music‑related concepts, we present a taxonomy that reflects the types of musical information covered. Rather than serving as a rigid framework, this taxonomy highlights thematic relationships among different question types, offering a reference point for future studies or the development of more structured taxonomies in MQA. This is not intended as a strict classification but as an overview of the diverse aspects of music captured by our questions.

Figure 7 presents this taxonomy, which includes the following broad categories and subcategories:

Instrumentation and Sound: Identification and presence of sound (e.g., ‘Is the singer always singing?’), as well as attributes and comparisons (e.g., ‘Does the violin play the same rhythm as the djembe?’).

Performance Dynamics: Performer actions and interactions (e.g., ‘How many times does the performer visually interact with the audience?’), as well as temporal changes and consistency (e.g., ‘How many times does the tempo change?’).

Spatial Arrangement and Context: Stage and audience positioning (e.g., ‘Where is the audience in relation to the performance setup?’) and spatial movement dynamics (e.g., ‘What is the spatial arrangement of the dancers on stage?’).

Emotion and Expression: Emotional responses (e.g., ‘Did the singer’s gestures convey the emotion of the music?’) and expressive elements (e.g., ‘Does the energy level of the performance increase or decrease as it progresses?’).

Technical and Causal Relationships: Temporal and causal elements (e.g., ‘What is the first instrument that comes in?’) and environmental influences (e.g., ‘Is there any background ambiance or environmental sounds audible during the music performance?’).

Figure 7

Question taxonomy. This visual representation highlights the hierarchical structure and interconnections between different questions.

4.2.2 Question collection and annotation

The annotation process, carried out over one month by a team of research assistants with Master’s degrees in Musicology, involved two primary annotators selecting answers and a third resolving disagreements. One annotator specialized in Ethnomusicology with over seven years of experience in world folk music. All annotators were compensated for their time. The authors managed question creation to ensure alignment with the study’s objectives.

At least two annotators annotated each video and communicated with the question creators. A helper file was provided to guide the annotators, outlining question focus (audio, video, or both) and category (e.g., location, counting), with examples of good and bad annotations and multiple‑choice answers.

We followed the answer‑labeling strategy from Li et al. (2022), considering an answer correct if selected by two annotators. In cases of disagreement, a third annotator made the final decision. This process ensured consistency, resulting in answers to 12,759 questions, of which we kept 11,793 to maintain a balanced answer distribution.

5 Experiment

To assess the ability of multimodal models to answer music‑related questions, we conducted experiments using the MusiQAl dataset. These experiments assessed model performance across question categories and modalities, comparing the effectiveness of the AVST and LAVISH architectures. These models were selected because they provide a strong baseline for multimodal learning, and both offer relatively straightforward integration with audiovisual datasets. Additionally, both models have publicly available implementations, which made them practical choices. The following sections describe the dataset preprocessing, feature extraction methods, training procedures, and evaluation metrics used in our study.

5.1 Experiment design

5.1.1 Dataset pre‑processing

We extracted video, motion, and audio features to prepare videos for training. Each video was one minute long and sampled in 80 frames, resized to 224224 pixels. A pre‑trained ResNet18 model (He et al., 2015), following the AVST baseline (Li et al., 2022), was used to extract visual features of dimension 512 from these frames. We used the R(2+1)D model to capture motion, pre‑trained on Kinetics‑400 (Li et al., 2022). This model processes frames in clips resized to 112112 pixels, producing 512‑dimensional vectors that encode movement and spatial relationships.

For audio, we extracted the sound and converted it into a log Mel spectrogram using a 25‑ms window, 10‑ms hop size, and a 64‑band Mel filterbank (125–7500 Hz). We resampled the audio to 16 kHz and converted it to mono. We then segmented the spectrograms into 0.96‑s patches and processed them with the VGGish model (Gemmeke et al., 2017), pre‑trained on AudioSet. This step generated features of dimension 128 that captured key aspects like spectral content and temporal patterns.

The pre‑trained models, including ResNet18 and VGGish, are part of the AVST and LAVISH frameworks. They were chosen for their effectiveness in extracting robust features from large, diverse datasets (e.g., ImageNet for ResNet18, AudioSet for VGGish). These models have been shown to reliably capture essential visual and audio features, making them well‑suited for complex multimodal tasks such as ours.

To process questions, we tokenized them, replacing placeholders (e.g., <Object>) with specific values during training and inference. Tokens were mapped to a predefined vocabulary and padded to a maximum of 15 words (according to the length of our longest question). Finally, a question encoder (QstEncoder) converted them into dense feature vectors, allowing smooth integration with audio–video features.

5.1.2 Architectures

We used the extracted features to train AVST (Li et al., 2022) and LAVISH (Lin et al., 2023). For AVST, we first concatenated the audio and video features, ensuring that both the spatio‑temporal information from the video frames and the dynamic characteristics from the audio signals were included. These combined features were then passed through the architecture’s fully connected layers to create joint representations, capturing the necessary information for MQA.

We used AVST’s attention mechanism for audio‑visual spatio‑temporal grounding to refine representations, aligning key audio‑visual interactions for improved predictions. Multihead attention enables the model to focus on relevant audio–video features at specific moments, with the question feature vector as the query and audio‑visual features as keys and values. The features are then refined through fully connected layers, capturing significant interactions across audio, video, and text to produce a unified multimodal vector for final predictions.

LAVISH fuses information differently. Advanced VisualAdapter layers are employed before the fusion process, enhancing the interaction between modalities. Swin Transformer is also used for more detailed and context‑aware visual feature extraction. Additionally, LAVISH introduces parameterization techniques like gating and LayerNorm for more nuanced handling of feature interactions, which helps us handle complex multimodal data more effectively.

5.1.3 Training

We trained the AVST (Li et al., 2022) and LAVISH (Lin et al., 2023) architectures on the MusiQAl’s question–answer pairs. We used a single model for all question types, assessing how well a unified framework can handle our questions. This approach allowed us to evaluate the overall performance of current methods rather than optimizing for specific question categories. The dataset was split into training, validation, and test sets (70%, 20%, and 10%, respectively). The test set was maintained to evaluate model performance independently after training and tuning, ensuring that our results accurately assess the model’s generalization capability, devoid of tuning artifacts. Given the size of our dataset and the substantial computational resources required for training, no cross‑validation was included. Similar to the approach in Liu et al. (2024b), to ensure a balanced data distribution of styles, instruments, and other factors in all our splits—but most importantly, our test set—we employed stratified sampling. This technique ensured we sampled proportionally from different categories, mitigating potential biases from overrepresenting particular genres or performance types. Stratification also helped balance the distribution of answers and unique questions across the dataset.

We optimized the model’s performance by exploring the best hyperparameters for training. To achieve this, we leveraged Optuna (Akiba et al., 2019), a framework for hyperparameter optimization, which explored the search space through a Bayesian approach. The learning rate was optimized using a log‑uniform distribution between 10−5 and 10−3, while batch sizes were set to for AVST. In contrast, LAVISH was restricted to a batch size of , following original paper recommendations and memory constraints. Optuna’s search process was conducted on the training and validation sets. We limited the optimization process to 50 trials, allowing for sufficient exploration while maintaining reasonable computation time. For the search process, we employed Optuna’s default Tree‑structured Parzen Estimator (TPE) acquisition function, which focuses on selecting promising hyperparameters while also considering unexplored areas of the search space. This approach reduces the number of trials needed to find optimal configurations, improving overall efficiency.

The optimization process resulted in a learning rate of for AVST, with a batch size of . The model was trained using the Adam optimizer. For LAVISH, the optimal parameters included a learning rate of and a batch size of 1. It (or LAVISH) was also trained using the Adam optimizer.

We proceeded with task‑specific adjustments to the network architecture to better align with the requirements of our dataset. First, we adjusted the QstEncoder module, where the number of input tokens was set to 235, allowing the question encoder to accommodate the vocabulary size required for our dataset. Additionally, the final answer prediction layer, fc_ans, was modified to output 143 classes, ensuring the output layer matches the number of possible answer categories for the task.

5.2 Results

5.2.1 Prediction accuracy per model

The models were evaluated based on their accuracy in predicting human‑annotated answers, which is the primary performance metric. The answer vocabulary consists of 143 distinct answers, covering objects, genres, spatial descriptions, numerical counts, and contextual descriptors. Following prior work (Li et al., 2022), both models were trained on the same feature set and evaluated on the same test set for consistency.

The results in Table 3 show the classification accuracy of AVST and LAVISH in predicting answers for different question categories. Each number represents the percentage of correct predictions made by the model compared to human‑annotated answers. In the audio (A) category, AVST outperforms LAVISH in existential (76.11% vs. 55.00%), temporal (76.37% vs. 52.90%), and causal (80.00% vs. 76.00%) question categories. On the other hand, LAVISH demonstrates a notable advantage in the counting question category (77.46% vs. 69.79%). This suggests that AVST is more adept at temporal and causal reasoning from audio, while LAVISH is stronger at numerical counting. On average, AVST achieves a higher audio‑specific accuracy of 72.32% compared to 66.03% for LAVISH.

Table 3

Performance comparison of the AVST and LAVISH models on the MusiQAl dataset.

| Model | Audio (A) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Existential | Location | Counting | Comparative | Temporal | Causal | Purpose | Avg | |

| AVST () | 76.11 | N/A | 69.79 | 72.65 | 76.37 | 80.00 | N/A | 72.32 |

| (std) | 1.82 | ‑ | 2.32 | 1.00 | 3.29 | 0.00 | ‑ | 1.02 |

| LAVISH () | 55.00 | N/A | 77.46 | 68.77 | 52.90 | 76.00 | N/A | 66.03 |

| (std) | 2.38 | ‑ | 1.01 | 1.47 | 4.33 | 8.94 | ‑ | 2.03 |

| Model | Video (V) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Existential | Location | Counting | Comparative | Temporal | Causal | Purpose | Avg | |

| AVST () | 94.55 | 69.08 | 68.75 | N/A | 73.41 | 63.51 | N/A | 69.48 |

| (std) | 4.98 | 1.55 | 1.71 | ‑ | 2.06 | 2.30 | ‑ | 0.87 |

| LAVISH () | 77.74 | 61.45 | 74.91 | N/A | 69.63 | 60.00 | N/A | 69.60 |

| (std) | 3.50 | 0.69 | 1.69 | ‑ | 4.65 | 3.12 | ‑ | 1.41 |

| Model | Audio–Video (AV) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Existential | Location | Counting | Comparative | Temporal | Causal | Purpose | Avg | AvgAll | |

| AVST () | 61.19 | 66.10 | 69.05 | 73.68 | 70.55 | 64.40 | 65.97 | 66.23 | 68.21 |

| (std) | 0.88 | 1.11 | 1.21 | 3.44 | 1.40 | 2.44 | 1.40 | 1.14 | 0.95 |

| LAVISH () | 80.80 | 63.83 | 64.42 | 82.37 | 50.00 | 76.99 | 73.23 | 70.08 | 69.78 |

| (std) | 0.38 | 1.51 | 0.55 | 0.71 | 1.40 | 1.63 | 1.38 | 0.27 | 0.48 |

[i] The results are detailed in three tables, corresponding to audio‑only (A), video‑only (V), and combined audio‑video (AV) question categories. All values represent answer prediction accuracy in percentage (%). For each model and category, the mean accuracy () over five independent runs is reported. The ‘(std)’ row presents the standard deviation, quantifying the performance variability across these runs. Both models were trained on human‑annotated question–answer pairs. Higher scores, indicating superior performance for a given category between the two models, are highlighted (in bold). ‘Avg’ refers to the average accuracy across all question categories within a specific modality (A, V, or AV), while ‘AvgAll’ represents the overall average across all three modalities.

In the video category (V), AVST shows superior performance in existential (94.55% vs. 77.74%) and location (69.08% vs. 61.45%) questions. This suggests AVST may better interpret object presence and spatial cues from video. AVST also slightly outperforms LAVISH in causal questions (63.51% vs. 60.00%). In contrast, LAVISH performs better in counting (74.91% vs. 68.75%) and temporal (69.63% vs. 73.41%) questions. Their average visual accuracy is very similar, with LAVISH scoring 69.60% and AVST scoring 69.48%.

In the audio–video category (AV), LAVISH outperforms AVST in the majority of categories, including existential (80.80% vs. 61.19%), comparative (82.37% vs. 73.68%), causal (76.99% vs. 64.40%), and purpose (73.23% vs. 65.97%) questions. However, AVST demonstrates higher accuracy in location, counting, and temporal questions. The contrasting performance suggests that LAVISH’s multimodal fusion is particularly effective for question types that rely on complex relational and causal reasoning. In contrast, AVST’s fusion process may be more adept at integrating direct spatio‑temporal and numerical cues. Overall, LAVISH achieves a higher average audio–video accuracy (70.08%) compared to AVST (66.23%), as well as a higher overall average performance across all modalities (69.78% vs. 68.21%).

5.2.2 Prediction accuracy per question type

Regarding trends in accuracy across different music styles or source datasets, we did not observe a systematic pattern indicating that certain styles or datasets performed better or worse overall. However, we identified variations in performance across different question types (Figure 8), which we now discuss in detail.

Figure 8

Accuracy of different questions based on modality (audio (A), audio–video (AV), or video (V)) and category (Causal, Comparative, Counting, Existential, Location, Purpose, Temporal).

Our findings indicate that the models achieved higher accuracies (above 70%) when answering questions based on clear observation, such as ‘Is this sound from the instrument in the video?’ or ‘Are there any lyrics?’ These questions provide clear answer choices with minimal ambiguity. Furthermore, questions about stage arrangement and performer–sound‑source localization also score above 70%, exemplified by ‘Where on stage is the dancer/singer during the solo?’ This shows that the models can visually confirm the location of objects and sounds.

Causal reasoning was also successful, with questions such as ‘Does the venue’s acoustics affect instrument placement and sound projection?’ or ‘Why did the audience cheer?’ The models’ ability to establish cause–effect relationships within musical performances is reflected in their high scores, all exceeding 70%. Similarly, they demonstrated proficiency in music–performer interaction. Their high accuracy in questions such as ‘Do the performers’ visual cues coordinate with the rhythm of the music?’ and ‘Did the object’s gestures convey the emotion of the music?’ suggests an advanced understanding of rhythm and expressive movement.

Both models could also recognize and quantify key performance elements, consistently scoring above 70% in tasks requiring numerical insights. They accurately predicted the number of solos featured and the number of performers/musical instruments, highlighting their ability to extract numerical insights, even in complex performance environments. These results underscore the models’ robust capabilities in audio–video music analysis and the dataset’s effectiveness in supporting structured evaluations of musical elements.

Certain question types struggled with accuracy (below 55%), often due to complexity, multiple variables, or temporal tracking difficulties. Style classification posed challenges, with musical and dance styles frequently misclassified into broad categories like ‘folk’ or ‘pop’ instead of specific subgenres. These results suggest that the dataset may have limited stylistic diversity or that the models struggle to distinguish subtle stylistic differences. This highlights the challenge of capturing nuanced styles, which may require better feature representations or refined category definitions.

Temporal and counting questions proved challenging, especially in complex performances with overlapping sound sources. For example, the models struggled with ‘Which instrument sounds simultaneously as the Object?’ and ‘What is the TH instrument that comes in?’ These tasks require a high memory load and spatiotemporal reasoning. MusiQAl’s inclusion of complex ensembles, unlike prior work focused on simpler scenarios, highlights the need for improved mechanisms to process overlapping auditory and visual cues in these challenging environments.

The model’s responses also revealed some interesting patterns. One example was that, in the question ‘Why is the performer wearing this attire?,’ the models sometimes labeled clothing from non‑European traditions as a ‘uniform,’ even when the attire was not traditional but simply a stylistic choice.

Another notable finding was the model’s ability to differentiate between a fiddle and a violin despite being essentially the same instrument (except for the Hardanger fiddle). This was particularly interesting because it aligns with real‑world distinctions, where the terms ‘fiddle’ and ‘violin’ are often used differently depending on musical style and context.

6 Discussion and Conclusions

In this paper, we highlight the importance of multimodal reasoning in MQA. Audio‑only analysis lacks the visual context to interpret dance, stage presence, and other performance aspects. Audio–video integration enables richer analysis, especially in genres like flamenco or samba, where dance and rhythm are intertwined. In MusiQAl, we include various musical instruments, performance styles, and settings to mitigate bias and promote cross‑cultural understanding. This aids machine learning models in developing a more accurate understanding of diverse music cultures.

Grounded in established theories of music understanding, perception, and cognition, MusiQAl’s question– answer pairs draw from research in musicology and music psychology. The questions are designed to capture meaningful auditory–visual relationships, supporting model evaluation and deeper insights into music performance and interpretation. Furthermore, we introduce causal reasoning tasks through new question categories for a richer, contextually aware dataset.

MusiQAl uses expert annotations from musicologists to ensure alignment with real‑world musical knowledge. Their evaluations, validated by inter‑annotator agreement, guarantee clarity, consistency, and adherence to the dataset’s goals, strengthening its ability to reflect real‑world musical contexts.

Training AVST and LAVISH architectures on MusiQAl confirmed its potential as a benchmark dataset for assessing model performance across various music performance contexts. While models excelled at existential reasoning, performer tracking, and synchronization, they struggled with style classification, source separation, and instrument detection in complex ensembles—skills crucial for real‑world applications. This suggests that specialized model architectures may be needed for different MQA questions.

Model performance on the dataset reflects success in achieving the dataset’s aims to advance music understanding, particularly focusing on embodiment, advanced reasoning, and cross‑cultural understanding. High accuracy in tasks involving direct observation, spatio‑temporal reasoning, causal inference, and performer– music interaction demonstrates that MusiQAl effectively captures core elements of music performance across diverse cultural contexts. This suggests the dataset provides a foundation for models to learn meaningful relationships within musical performances.

Despite its robustness, MusiQAl has limitations. Including questions with multiple valid answers creates ambiguity, likely contributing to difficulties in source separation during complex ensemble performances with overlapping sources. Furthermore, while gesture annotations and general connections between performance and emotional context are present, the lack of direct emotion annotations limits the exploration of expressive intent.

Future work will address the identified limitations and expand MusiQAl’s capabilities. Including more genres and cultural contexts could enhance inclusivity and mitigate existing biases, particularly in identifying performers’ attire. Future iterations will employ multi‑label annotation strategies to address questions with multiple valid answers, allowing both annotators and the model to select all correct answers and providing a more nuanced representation of potential responses. Simultaneously, future attempts will integrate metadata (e.g., performance context, historical details), physiological data (e.g., acceleration), motion capture, and symbolic music representations. This approach might not only improve cultural sensitivity and historical awareness but also enhance event detection, instrument recognition (particularly in ensemble settings), and the overall potential for multimodal analysis.

MusiQAl has potential applications in computational musicology, music education, and music therapy. Its structured alignment of audio, video, and text supports tasks beyond the current study, such as music captioning. Furthermore, MusiQAl can improve cross‑cultural understanding in music research and technologies by offering accurate representations of diverse genres and traditions. The advancements from new data integrations could help refine algorithms for genre classification, synchronization, and retrieval, which remains an important research direction.

In music education, MusiQAl can enhance interactive learning and performer tracking. Adaptive learning tools could use physiological feedback to tailor instruction based on student engagement and cognitive load, improving the effectiveness of music training. Beyond performance analysis, multimodal MQA systems can enhance accessibility through visual descriptions for visually impaired users, transcriptions for hearing‑impaired users, and interactive explanations of musical techniques for education.

Integrating physiological signals (respiration, heart rate, brain measurements) into MQA could reveal insights into cognitive responses to music. This knowledge can then support personalized interventions in music therapy, tailoring treatments to a listener’s emotional and cognitive state.

LLMs can improve MQA systems by enhancing context‑aware responses, refining question disambiguation, integrating multimodal data, and recognizing cultural nuances for a more globally inclusive understanding of music. These advancements will make MQA systems more accurate, context‑aware, and culturally adaptive for music research, education, and performance analysis.

In summary, MusiQAl offers a diverse and open‑source resource for multimodal music analysis, with applications in MIR and beyond. Its open availability facilitates interdisciplinary research. Future work will enhance the dataset’s adaptability, cultural inclusivity, and research relevance by incorporating multi‑label strategies and expanding modalities to include physiological data and metadata.

7 Reproducibility

To ensure the reproducibility of our research, we thoroughly explain our approach, including algorithms, models, and parameters used. We have also made all scripts and code for data preprocessing, model training, and evaluation publicly available with detailed instructions and documentation.2 The repository also includes the full dataset with annotated audio–video question–answer pairs and information on data collection, annotation guidelines, and preprocessing steps.

Acknowledgments

This project is supported by the Research Council of Norway through projects 262762 (RITMO), 322364 (fourMs), 335795 (DjembeDance), and 287152 (MIRAGE).

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization of the work. A.C. led the development and curation of the multimodal dataset, prepared the figures and tables, and wrote the original draft of the manuscript, with substantial input and guidance from A.J., O.L., and K.G. K.G. provided significant contributions to the methodology. A.J. and O.L. contributed significantly to the theoretical framework presented in the paper. All authors critically reviewed and edited the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version for publication.

Ethics and Consent

According to the University of Oslo’s standard for research integrity, formal institutional review board approval was not required for this research. Our study primarily involved the analysis of publicly available data and the engagement of annotators for task‑based work with fair compensation, without collecting sensitive personal identifiable information beyond that necessary for remuneration. All data used are publicly available and have been appropriately cited, respecting any original terms of use.

We recognize that developing large‑scale musical datasets and associated technologies has significant ethical implications. Positive applications include supporting education through automated feedback for student musicians and advancing interdisciplinary research in music cognition and creativity. Nonetheless, we also acknowledge potential risks, such as the displacement of skilled human educators by automated systems. To address these concerns, our methods have been designed with transparency in mind, ensuring that the dataset and its applications are well‑documented and responsibly used. Additionally, we envision the technology complementing rather than replacing human expertise, enabling educators to focus on creative and higher‑order tasks. Finally, by curating a diverse dataset, we aim to promote inclusion and provide equitable opportunities for studying and applying musical traditions from a wide range of cultures and contexts.

Additional File

The additional file for this article can be found using the links below:

Notes

[3] ISMIR Community Resource of MIR Datasets. Available at: https://ismir.net/resources/datasets/. Accessed on: 30.05.2025

[4] Public repository for scripts and code. Available at: https://zenodo.org/records/13623449 and https://github.com/MuTecEn/MusiQAl. Accessed on: 30.05.2025