Introduction

The challenges that present-day globalization poses in setting international labour standards are not uncharted. The conflict between global considerations, on the one hand, and national and local dimensions, on the other, is well-known to the International Labour Organization (hereinafter referred to as the ILO).1 This issue resurfaces at this time, as the International Labour Conference (ILC) has agreed to develop a new ILO Convention and Recommendation on decent work in the platform economy, with final adoption expected at the 2026 ILC.2

In this context, much can be learned from the wide range of institutional responses, such as jurisprudence, social dialogue, and legislative reform, that have already emerged at lower levels. Their diverse approaches are especially relevant to consider now, when the ILO is committed to adopting a labour standard on platform work. Due to the heterogeneous nature of the ILO’s member states, attempting a universal mandate on platform work adds an extra layer of complexity to regulating this phenomenon, compared to previous efforts at the national or even transnational level, such as the EU’s recent directive on improving working conditions for platform workers (hereinafter PWD).3 While recognizing that countries within similar regions are far from homogeneous, many scholars, including the International Labour Organization itself, have highlighted that the role of platform work in society is heavily influenced by the diverse contexts of the global North (hereinafter GN) and the global South (hereinafter GS).4

Examining how different domestic institutional systems—such as judicial, industrial relations, and legislative systems—have responded to the rise of platform work so far, and considering the factors that may have influenced these responses through the broad lenses of the global North and global South, can offer valuable insights and deepen our understanding of the challenges faced in various regions. There is an urgent need to identify commonalities and shared traits across cases, which can benefit different stakeholders, including policymakers.5 The North–South divide, though not without limitations, provides a meaningful framework for making sense of the differences highlighted in the mapping.

Significant contributions to the literature offer an overview of various developments stemming from platform workers’ labour unrest.6 This paper builds on previous research and contributes to the literature by mapping the global landscape. It aims to shed light on the underrepresented and under-researched region of the GS,7 helping to bridge this gap by examining global institutional responses, with a special focus on the GS. Furthermore, this paper lays the groundwork for a comprehensive understanding of how various institutional mechanisms used by platform workers interact, as most mapping efforts have examined the outcomes of institutional channels, such as case law or collective bargaining, separately.

This paper sets out to present a broad overview of precisely this by drawing on the data collected through a global mapping of jurisprudence, social dialogue, and legislative initiatives in the platform economy, last updated in February 2024, which was carried out based on an extensive review of academic and grey literature, institutional and research databases, and media. This paper presents a part of the results from this exercise,8 primarily focusing on the material scope and outcomes of the initiatives identified in the recollection. A detailed overview of the collected data, along with complete addenda, can be obtained from the author.

To achieve this, the paper is structured as follows: Section I discusses the methodology used for mapping and its limitations. Section II provides an overview of the mapping results, reviewing the material scope and emerging patterns identified when litigation, social dialogue, and legislative reform are used in response to platform work. This section examines the substantive matters (rights and obligations) covered by these initiatives in different jurisdictions and how various systems have responded. Analysing this through the lens of the GN and GS’s diverse contexts reveals significant differences in how these institutional channels have been utilized and how systems responded to this challenge. It highlights varying levels of precarity and perceptions of platform work that are important to consider in future regulation. Section III presents concluding remarks, outlining some key aspects of platform work’s role in society that have been identified, which are strongly influenced by the different contexts of the global North and South. These considerations should be relevant in the upcoming instrument.

Section I: Methodology and Limitations

As mentioned in the introduction, this article presents a fragment of the results of a comprehensive global mapping of case law, social dialogue initiatives, and legislative reform initiatives carried out in accordance with the following definitions (Table 1):

Table 1

Definitions.

| DEFINITIONS | |

|---|---|

| Digital Labour Platform Platform Workers | These concepts will be understood in light of the definitions contained in Article 1 of the ILO’s Draft Convention concerning decent work in the platform economy.9 |

| Global North and South | The use of the North-South divide aims to explore widely diverse contexts, with an emphasis on geopolitical power relations.10 Following the definition provided by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), the Global South broadly comprises Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, Asia (excluding Israel, Japan, and South Korea), and Oceania (excluding Australia and New Zealand). The global North comprises North America, Europe, Israel, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand.11 |

| Collective Actors | The collective actors considered for this mapping are broad, encompassing traditional and newly emerging organizations, such as mainstream and grassroots unions, platform cooperatives, communities, self-organized worker groups, and associations.12 |

| Traditional Collective Actors (also referred to as mainstream unions) | Established, typically longstanding, politically moderate (social democratic), and usually affiliated to a national union confederation. Tend to be more hierarchically organized.13 |

| Newly emerging Collective Actors | Includes grassroots unions and self-organized groups of workers. Grassroots unions: Usually newer, politically more radical, and not part of a national confederation. Tend to have a more horizontal structure.14 Self-organized groups of workers: Informal groups of workers, workers collectives identified by having a distinct name, a webpage or equivalent, and not being a union.15 |

| Institutional Power Resources | This refers to important sources of power that stem from institutions such as collective bargaining systems, employment protection legislation, and conciliation and arbitration systems.16 |

| Case law/jurisprudence | Judicial or administrative decisions addressing the issue of labour conditions for platform workers. This includes, but is not limited to, court cases fighting the contractual misclassification of platform workers. The mapping encompasses a range of decisions stemming from judicialization as a mode of protest, extending beyond the issue of platform workers’ status. Pending cases are not included. |

| Social dialogue initiative | Following Lamannis, this includes both the traditional process where trade unions negotiate with employers/employers’ associations to reach a binding collective agreement, and also all social dialogue initiatives in which collective bodies that are not necessarily trade unions or employers’ associations (e.g. unconventional organizations, public authorities) participate, to negotiate an agreement that might not be binding in itself (i.e. code of conducts, voluntary agreements, collaboration agreements, inter alia).17 |

| Legislation | The diverse initiatives implemented at different levels—i.e., international, regional, and domestic—that seek to regulate the working conditions of platform workers, aiming to improve them from a labour perspective. |

The mapping of case law, social dialogue initiatives, and legislative reform initiatives carried out was last updated in February 2024, and it consisted of three steps:

a. General information gathering and extensive mapping of case law, collective bargaining, and social dialogue agreements, and enacted legislation by means of consulting academic and grey literature, institutional and research databases, and media;

The sources accessed are detailed in Annex I.

In addition, in jurisdictions where the general databases consulted were deemed insufficient, outdated, or unreliable (mostly outside of Europe), but some activity was identified in the initial search, national research databases, academic literature, grey literature, and media reports were used to complement these findings. These sources are all recorded within the research log.

Classification of the initiatives recorded within the research log and initial analysis of relevant aspects: The initiatives identified in each strategy were recorded within a research log and classified according to their geographical location, court, instance, date, type of actor and procedure, sector, subject, summary, outcome, and source. The author can provide a detailed overview of the research log, including all relevant information gathered.

Verification and further research of the initial information: When the sources employed were not primary sources, the comprehensiveness and accuracy of the information gathered were verified, when possible, through additional sources such as academic literature, media reports, and discussions with country experts.

In this regard, essential limitations must be acknowledged. First, the mapping attempts to be as comprehensive as possible, and the results reflect the current state of play to the best of the author’s knowledge. However, it is not all-encompassing. This academic exercise is limited to the cases identified in the databases and sources employed as described in the methodology. This is accentuated in the platform economy, as it is a constantly evolving target where decisions, regulations, and social dialogue initiatives continue to emerge. Since this mapping was last updated, important sources reporting new information have been published.

Second, it must be acknowledged that access to information and sources in the GS is restricted, partially due to it being heavily under-researched.18 Although this mapping aims to help address this limitation, it is significant and must be considered when interpreting the results, highlighting the need for further research in the GS region. Additionally, the methodology used identified a very high number of cases in China that were beyond the scope of the research due to its size. Therefore, this jurisdiction was excluded from the analysis because of these reasons, along with limited access, scarce resources, and language barriers. In this context, limited language proficiency is a significant constraint that must be recognized. While the databases and sources generally provided information in English—or at least a brief summary in English—some initiatives were only available in languages in which the author is not proficient. In such cases, machine translation was used to help address this limitation. Therefore, acknowledging these caveats, this contribution should not be understood as a definitive or exhaustive account. Rather, it complements existing initiatives, such as the ‘Digital Labour Platform Tracker’ and the Cambridge Centre for Business Research (CBR)’s Labour Regulation Index Dataset, by offering an additional perspective within a broader and evolving body of research.

As a final consideration, this paper examines a wide range of contexts through the lens of the GN and GS divide, with the aim of identifying commonalities and broad characteristics shared across cases, which are expected to be useful for policymakers.19 However, it is acknowledged that although countries within similar regions and corresponding to the same cluster share traits and contexts that may be relevant for regulatory purposes, they are far from homogeneous. There is no attempt to claim otherwise.

Section II: Results

The mapping conducted identified case law, social dialogue initiatives, and legislative reform initiatives that addressed the issue of labour conditions of platform workers worldwide. The initiatives identified were spread geographically, as detailed in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2

Geographical Dispersion of the Initiatives Identified Available in the Author’s Database.

| REGION | CASE LAW | SOCIAL DIALOGUE | LEGISLATIVE REFORM INITIATIVES |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global North | 787 | 84 | 36 |

| Global South | 551 | 11 | 16 |

| Total | 1338 | 95 | 52 |

Table 3

Initiatives Identified Per Country Available In The Author’s Database.

| COUNTRY | CASE LAW | COLLECTIVE BARGAINING | LEGISLATIVE REFORM | TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | 25 | 6 | 5 | 36 |

| Australia | 11 | 3 | 2 | 16 |

| Austria | 10 | 2 | 2 | 14 |

| Belgium | 11 | 1 | 2 | 14 |

| Brazil | 486 | 0 | 4 | 490 |

| Canada | 5 | 0 | 1 | 6 |

| Chile | 12 | 4 | 1 | 17 |

| China | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Colombia | 6 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Croatia | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Denmark | 6 | 7 | 0 | 13 |

| Estonia | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| European Union | 4 | 1 | 5 | 10 |

| Finland | 6 | 1 | 2 | 9 |

| France | 169 | 10 | 6 | 185 |

| Georgia | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Germany | 13 | 8 | 2 | 23 |

| Greece | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| Hungary | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| India | 3 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| Indonesia | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Ireland | 4 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| Israel | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Italy | 42 | 25 | 6 | 73 |

| Kazakhstan | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Kenya | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Latvia | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Lithuania | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Luxembourg | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Malta | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Mexico | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Netherlands | 29 | 1 | 2 | 32 |

| New Zealand | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Nigeria | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Norway | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Pakistan | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Panama | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Peru | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Philippines | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Poland | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Portugal | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| Republic of Korea | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Romania | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Singapore | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Slovenia | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| South Africa | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| South Korea | 12 | 0 | 0 | 12 |

| Spain | 301 | 12 | 3 | 316 |

| Sweden | 10 | 6 | 1 | 17 |

| Switzerland | 22 | 4 | 0 | 26 |

| Tanzania | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Turkey | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| United Kingdom | 33 | 4 | 0 | 37 |

| United States of America | 84 | 1 | 6 | 91 |

| Uruguay | 6 | 0 | 1 | 7 |

The results attest to the impact of globalization embodied in the platform economy, as these outcomes, resulting from the employment of institutional mechanisms, were present to varying degrees in different countries and regions worldwide. The overall results indicate that institutional responses were more frequently identified in the GN than in the GS. This is true for case law, social dialogue—most notably—and legislative reform.

The lower number of institutional responses to platform work in the GS is probably attributable to several factors. As previous exercises such as the Leeds Index of Platform Worker Protest exhibit, this is not a reflection of a lack of mobilization and attention to the precarious working conditions of platform workers in this region, as protests on this issue were frequently identified both in the GN and GS, although reasons for protesting differ significantly between regions.20 However, it does suggest that platform workers resort to institutional mechanisms as a form of protest to a lower degree in the GS, that these channels have been less effective in this region, or both.

A factor that likely influenced this (mostly concerning the existence of case law) is that adherence to the rule of law is significantly weaker in the GS, which impacts access to prompt justice and procedural and judicial safeguards.21 In addition, the mapping results show that state and collective actors held a predominant role in the GN, primarily in litigation, and were less prominent in the GS. This factor may also come into play when explaining the different degrees of institutional responses, as state actors and collective actors were important in bringing lawsuits to Court in the GN, for example.

The following sections will examine, in addition to the insights provided by quantitative data, the material scope and main topics in debate from a qualitative perspective. What rights and obligations were examined in different jurisdictions, and how did these systems respond? Examining this from the perspective of the GN and GS’s diverse contexts reveals key differences in how these institutional channels have been utilized and responded to this challenge.

1. Case Law

This research identified and reviewed 1,338 judicial and administrative decisions spanning 39 countries in the global North and South regions. Out of these 1338 cases, 892 were first-instance cases. The remaining cases correspond with further instances in the process.

The claims brought by various actors to judicial or administrative authorities exhibit substantial similarities and parallel characteristics across jurisdictions, indicating the relatively standardized employment practices of digital labour platforms worldwide. The literature has described such practices in depth as part of the business model of platform companies.22

These claims were submitted before various bodies and procedures, including labour inspections, social security institutions, tax authorities, competition and data protection authorities, civil and commercial courts, specialized employment courts, state prosecutors, criminal courts, and constitutional courts.

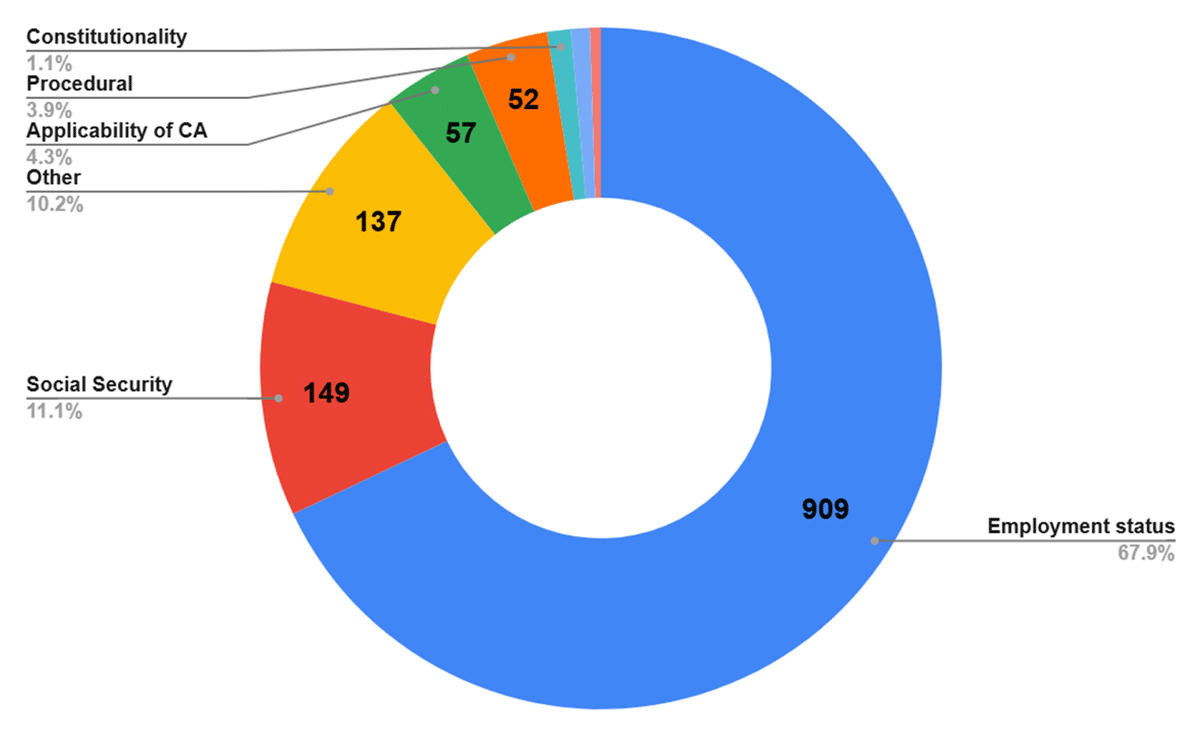

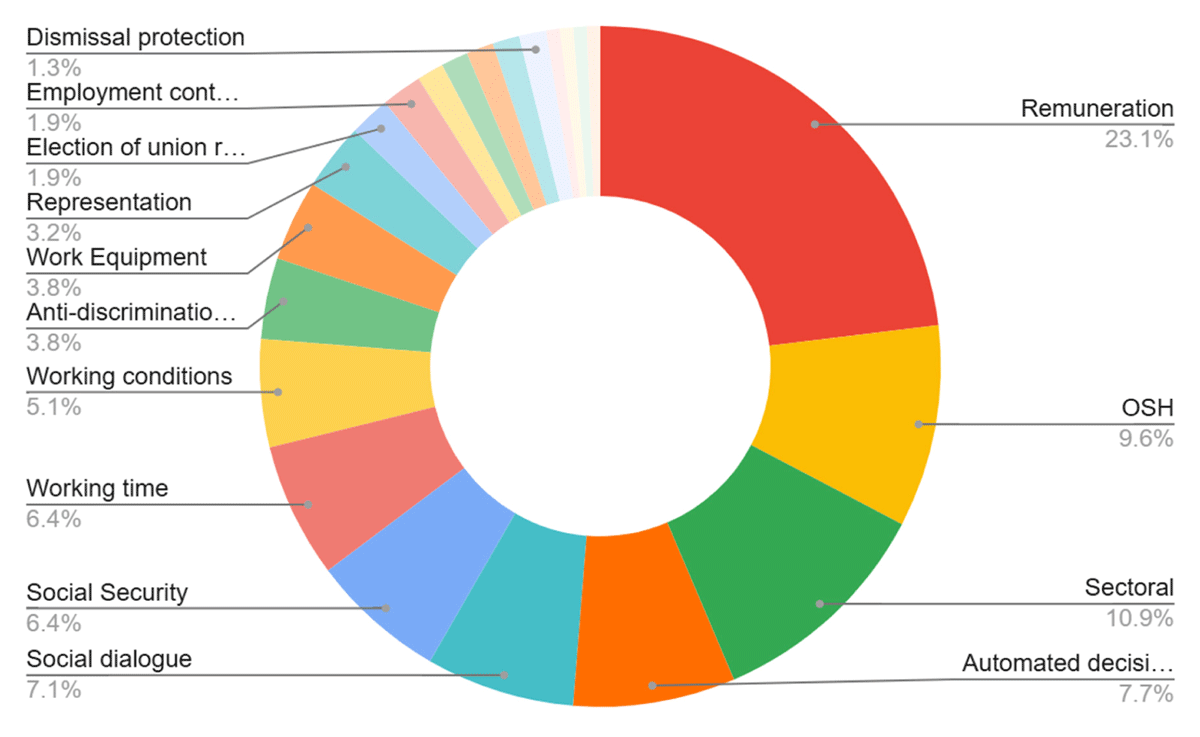

The most common claim found in the mapping was the request for recognition of the employment relationship, followed by claims regarding social security entitlements (see Figure 1). In this sense, the majority of the cases are centered on misclassification, confirming the widespread use of regulatory arbitrage in the platform economy.23

Figure 1

Most Common Claims In Case Law (Worldwide) Available in the Authors’ database.

Source: Author’s elaboration.

Some exceptions were identified, where platform workers were employed at a relatively early stage of their mobilization cycle or the use of regulatory arbitrage was much more nuanced, predominantly in the GN. Nevertheless, other conditions of precarity, such as a lack of work equipment or fragmented employment relationships, persisted, as illustrated by the examples below.

In Germany, for example, couriers filed two lawsuits against ‘Lieferando’ with the support of the ‘Gewerkschaft Nahrung-Genuss-Gaststätten’ – NGG. These couriers were engaged with the platform through an employment contract and demanded that the platform provide them with the necessary work equipment for the agreed-upon activity as a bicycle supplier. The ‘Federal Labour Court’ ruled in favour of the plaintiffs in both cases, stating that they were entitled to the defendant providing the necessary work equipment (i.e., a roadworthy bicycle and an internet-capable mobile phone). The contractual agreement, which stated that the plaintiff must use their own bicycle and mobile phone, was deemed ineffective by the judge.24

Similarly, a lawsuit was lodged by the ‘Swedish Transport Workers’ Union’ against ‘Foodora’ for the dismissal conditions of a worker. In this case, ‘Foodora’ employed the bicycle courier on a fixed-term basis; however, when the worker started carrying out his deliveries on a motorbike, he was referred to sign a contract with an intermediary staffing company while continuing to work for ‘Foodora’ under substantially similar conditions. Thus, a dispute surfaced as to whether the worker should be considered to have remained employed by ‘Foodora’, whether the employment was for an indefinite duration, whether he had been dismissed from that employment, and whether there was a factual basis for dismissal. The Court decided in November 2022 that ‘Foodora’ had no employer liability, and that the intermediary should be considered a staffing company.25

A wide range of secondary issues was often identified and addressed in the context of misclassification claims, as shown in Table 3. It is essential to note that the misclassification issue was not uniform or one-dimensional, as it involved various shades of disguised relationships, including self-employed workers, outsourcing chains, complex business structures, and temporary agency work arrangements. Hießl has thoroughly researched these multiparty relationships in platform work within a European context.26

In turn, complaints related to social security contributions were the second most common claim globally. Although social security claims are closely connected to the issue of misclassification, it is essential to note that this category refers to lawsuits where the recognition of social security entitlements was the primary object of the claim, rather than procedures where social security contributions were recognized as a consequence of pursuing the recognition of employment status. These were almost entirely filed in the global North, as observed in Table 4. Nearly half the cases that pursued this claim (47.65%) were brought by state institutions and/or collective actors (see Table 5).

Table 4

Secondary Subjects Discussed in Employment (Misclassification Claims) in Case Law Available in the Authors’ database.

| GENERAL ISSUE | SECONDARY SUBJECT |

|---|---|

| Determination of employer | Subsidiary liability, illegal intermediation, single business unit, real employer, temporary agency work. |

| Entitlements of an employment relationship | Overtime pay (unpaid work, waiting time), holiday pay, social security contributions, compensation for unfair dismissal (account deactivation) |

| Freedom of association | Union recognition, discrimination for union activities, unfair dismissal for union activities, account deactivation, collective redundancies |

| Concealed work | Right to substitution, account renting, illegal migrant work |

| Collective bargaining | Applicability of collective agreement |

| Social security | Sick pay, accident insurance, unemployment benefits, occupational pension. |

| Health and safety obligations | Personal protection elements. |

| Other Obligations of the Platform | Provide information, working equipment, registration obligation |

| Technology and data | Algorithmic management, human review, and discrimination by the algorithm, right to information. |

| Debt | Conforming contract; private bailiff; loan for work equipment. |

| Competition Law | Unfair competition. |

Table 5

Distribution of Most Common Claims in Case Law by Region Available in the Authors’ database.

| CLAIM | CASES(GN) | % | CASES(GS) | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment status | 384 | 42.24% | 525 | 57.76% |

| Social Security | 145 | 97.32% | 4 | 2.68% |

| Other (OSH, overtime pay, unfair dismissal, sick pay, transfer of undertakings, competition law, criminal or commercial procedures, discrimination, etc). | 124 | 90.51% | 13 | 9.49% |

| Applicability of CA | 57 | 100.00% | 0 | 0% |

| Procedural | 50 | 96.15% | 2 | 3.85% |

| Constitutionality | 8 | 53.33% | 7 | 46.67% |

| GDPR | 12 | 100.00% | 0 | 0% |

| Tax | 7 | 100.00% | 0 | 0% |

| Grand Total | 787 | 551 |

Platform companies themselves were also common actors in bringing this claim to court after administrative authorities—such as Labour Inspections, Social Security Institutions, and Tax Authorities—issued an administrative decision ordering the recognition and payment of tax or social security contributions to the platform company (Table 6).

Table 6

Actors Involved in Case Law Concerning Social Security Available in the Authors’ Database.

| TYPE OF ACTOR | CASES | % |

|---|---|---|

| Platform | 55 | 36.91% |

| State | 53 | 35.57% |

| Individual | 22 | 14.77% |

| Collective | 18 | 12.08% |

| N/A | 1 | 0.67% |

| Grand Total | 149 | 100% |

This claim was not common in the GS. This may be influenced by welfare states that recognize social security entitlements to their citizens, which are predominant in the GN, together with the low involvement of state institutions/collective actors identified in the mapping and the limited coverage of social security systems in the GS,27 leading to a low resort to litigation in this region.

Other claims presented independently of the misclassification issue included the applicability of collective agreements, violations of data protection principles, and constitutional matters. Excluding the latter, these claims were preponderantly filed in the GN. (see Table 4)

Procedures requesting the applicability of a collective agreement tended to be Eurocentric. Given that social dialogue initiatives in the GS were much less common, this confirms that, as some literature suggests, collective agreements as an institutional tool are generally stronger in the GN (and more specifically in Europe).28 This claim was most prominent in the Netherlands, Spain, and Italy. Often, it involved workers or collective actors—who were logically important actors in these procedures—requesting that a specific collective agreement be declared applicable to a platform company (for example, the collective bargaining agreement for the Taxi industry in the Dutch case). In most cases, the platform company was not applying any collective agreement. However, some Spanish examples were interesting because the actors requested the applicability of the collective agreement for logistics rather than for the courier sector, showcasing an interesting innovation: these workers were already covered by a collective agreement, which likely reflects the influence of the Riders’ Law in Spain.

Regarding violations of data protection principles, this claim mainly refers to the use of the existing data rights framework—primarily the GDPR—to address breaches of platforms’ obligations to disclose details about algorithmic management processes and automated decision-making. Therefore, it is not surprising that these cases are most common in Europe, as the GDPR has limited jurisdiction within the EU member states. In the absence of specific labor law provisions applicable to self-employed workers, the broad scope of data rights—which extend to all individuals regardless of employment status—has provided alternative legal channels for establishing protections against exploitative platform practices. At the time of writing, the number of cases involving this issue continues to grow within the European context, positioning itself as a promising tool to defend the working conditions of platform workers and the broader workforce. These decisions mark significant progress, reflecting a shift in focus from employment classification to data transparency and access to information as ways to better understand organizational models and limit the expansion of employers’ discretion.29

In turn, concerning procedures that claimed constitutionality violations, these were most commonly presented against the enactment of a law specific to platform work (e.g., against Proposition 22 in the USA, the Loi relative à la relance économique et au renforcement de la cohésion sociale du 18 juillet 2018 in Belgium, or the law banning platform-based transportation in Brazil). Such procedures all requested that the law be declared unconstitutional/inapplicable. This claim was also commonly brought in response to the deactivation of workers’ account, mostly connected to the fundamental right to work.

A peculiar example is the Colombian jurisdiction, where, although only one case has reached a decision by the labour courts, a handful of decisions have been examined by the constitutional jurisdiction. This may be explained by the fact that the constitutional jurisdiction in Colombia is subject to an abbreviated procedure. Notably, in judgment T-109/2021,30 the highest court in Colombia for constitutional matters declared the existence of an employment contract for an adult webcam content creator who provided her services through a digital labour platform. The court considered the adverse consequences imposed for not logging into the platform, the constant monitoring, the control over clients’ payment methods, and the power to review complaints about content uploaded as crucial elements in reaching this decision.31 Other decisions in the constitutional jurisdiction referred to the platform’s disregard for the right to due process when deactivating a worker’s account. (T-534/2332 and No. 1100141890212021008780033). In addition to constitutional jurisdiction, lawsuits were also brought to criminal courts. Examples were identified in jurisdictions such as France34 and Italy,35 where criminal procedures were brought forward against platforms for the engagement of illegal migrants.

Lastly, procedural claims involve procedures where the main focus of the decision is of a procedural nature, such as jurisdictional conflicts, the enforceability of the arbitration clause, the certification of a class action, or other procedural issues. The debate over the enforceability of arbitration clauses was most prominent and supported by courts in Anglo-Saxon systems, such as the USA and Canada, often resulting in the arbitration clause being upheld. Jurisdictional disputes were also common, as platform companies frequently argued that the labour court lacked competence. This argument was often accepted in French and Brazilian courts, leading to many claims being dismissed. Overall, although some judges have moved beyond formalistic approaches and have argued against procedural tactics used by platforms, they still face significant obstacles, as seen with arbitration clauses in the USA and jurisdictional disputes in Brazil, which often prevent courts from addressing substantive issues.36

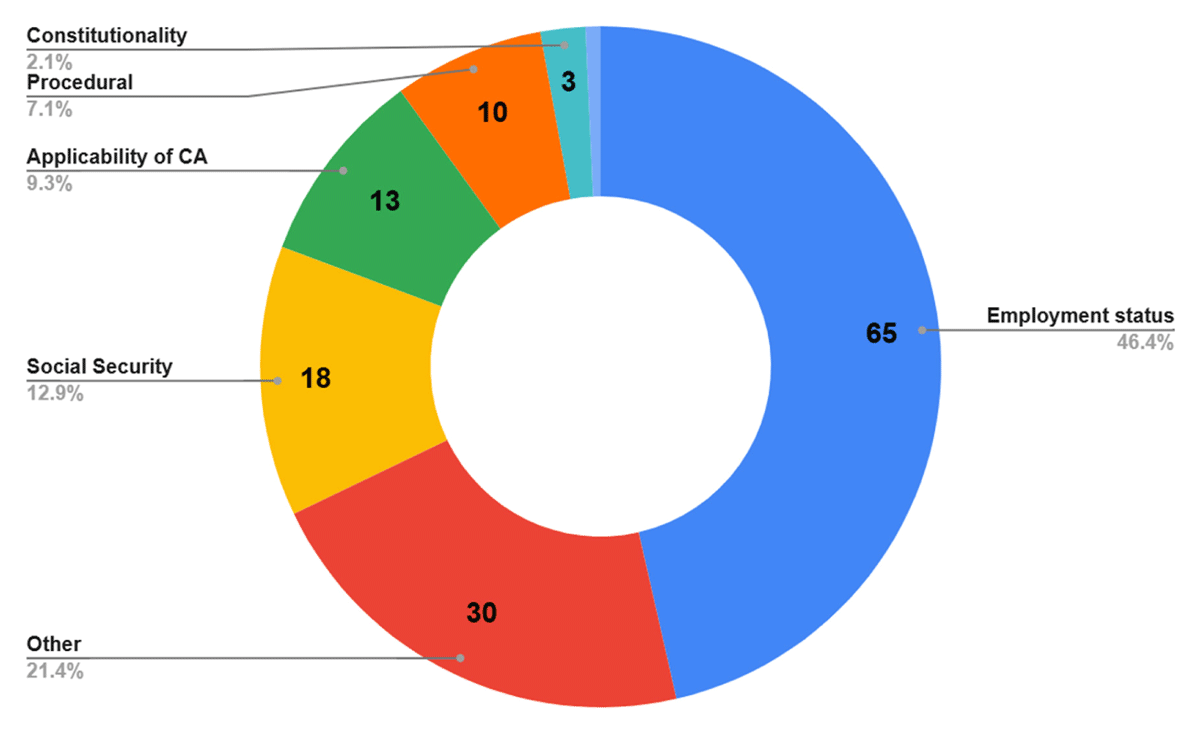

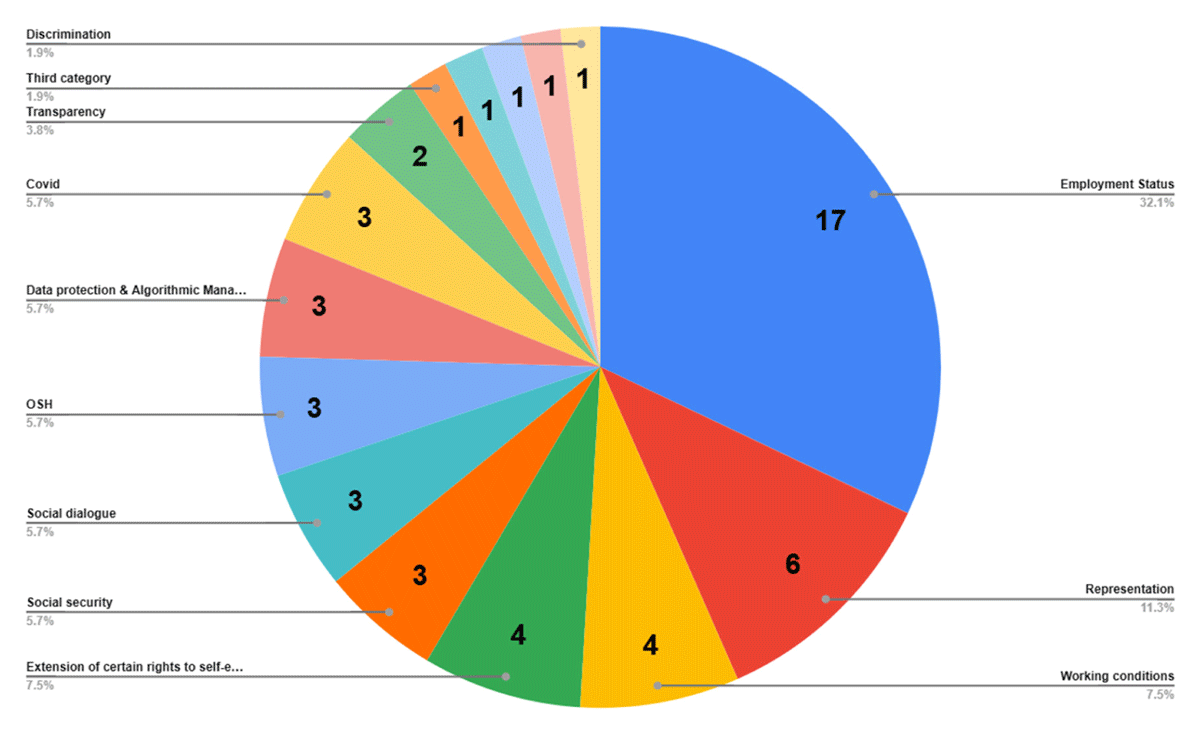

Despite the clear prevalence of misclassification claims in general, when examining the cases brought to court by collective actors, as observed in Figure 2, over 53% of them involve other grievances. These include the applicability of the collective agreement, data protection, and claims related to algorithmic management, work and safety equipment, complaints against anti-union activity, the need to reactivate accounts during COVID-19 times to guarantee subsistence, or requests to guarantee their right to work when the platform was suspended from operations.

Figure 2

Cases Brought To Court By Collective Actors In Case Law Available in the Authors’ database.

Source: Author’s elaboration.

This suggests that collective actors are resorting to litigation for issues beyond employment status, possibly using it strategically to enforce smaller claims. As argued by Gaudio, collective litigation is advantageous over individual one as it enables the enforcement of small claims where many workers have been affected homogenously by the same or analogous decision-making processes, as often happens with algorithmic management devices. In these situations, damages may be small for each worker, and bringing an individual claim would be meaningless for them. However, since the sum of individual damages may be significant if the rights of many workers are infringed, this potential gap may be filled through collective litigation.37

In sum, misclassification was the main issue leading to litigation in both the GN and the GS. Another common claim in both regions involved platform workers requesting the reactivation of their blocked accounts. Social security issues were much more prevalent in the GN and were mostly brought forward by the state and collective actors. This claim was most prominent in welfare states such as Switzerland, Spain, France, and South Korea, where social security institutions likely had to bear some costs because these workers were not covered by insurance. Conversely, it was rare in the GS. This aligns with the fact that, although social security systems in the Global South are expanding, coverage remains limited (confined to small sections of the population that are in formal employment), leaving billions without protection.38 Regardless, landmark cases such as the lawsuit filed by the ‘Sindicato dos Trabalhadores com Aplicativos de Transporte Terrestre Intermunicipal do Estado de Sao Paulo,’ which requested safety equipment for workers during the COVID pandemic, were identified.39

Other claims, such as GDPR, the applicability of collective agreements, and the exercise of information and consultation rights, have mostly been the subject of litigation in the GN. This may be attributed to the fact GN jurisdictions have data protection laws, like the EU’s GDPR. These issues were not frequently brought to court in the GS, likely because several—though not all—GS countries lack suitable laws for the protection of personal data. In this region, litigation primarily involved the reclassification of employment contracts or constitutional claims, seeking the immediate protection or restoration of fundamental rights. Examples include reactivating workers’ blocked accounts to guarantee the right to work, protecting the fundamental right to freedom of association, accessing medical care due to an industrial accident, or challenging the validity of laws that specifically regulate or ban platform work.

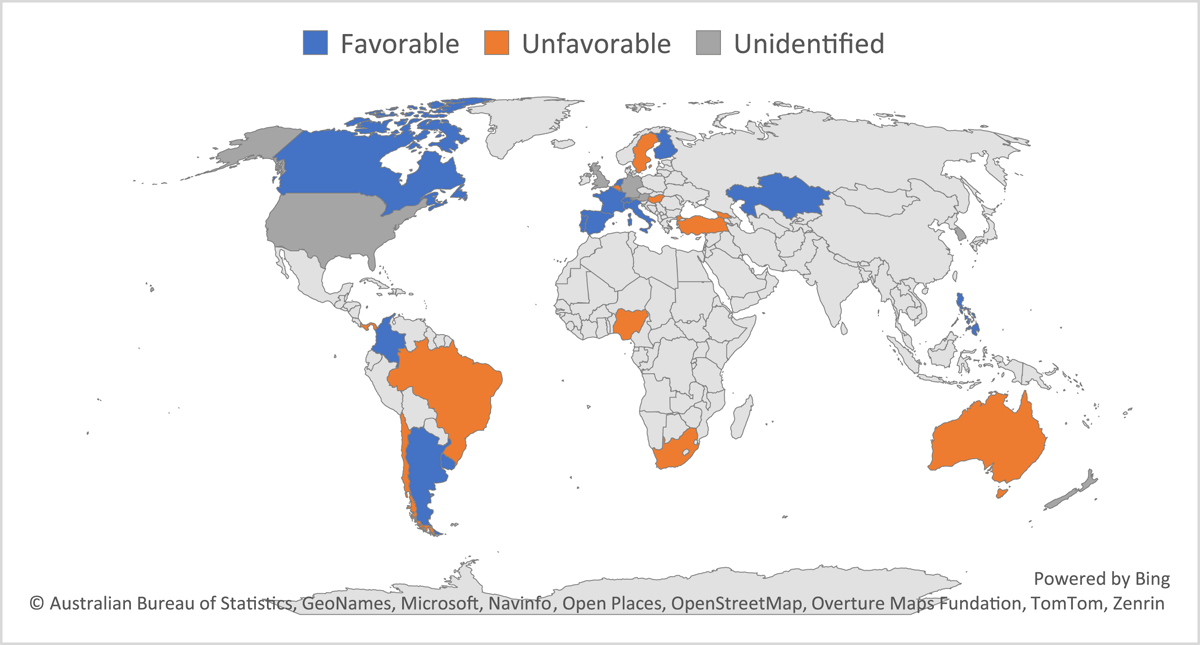

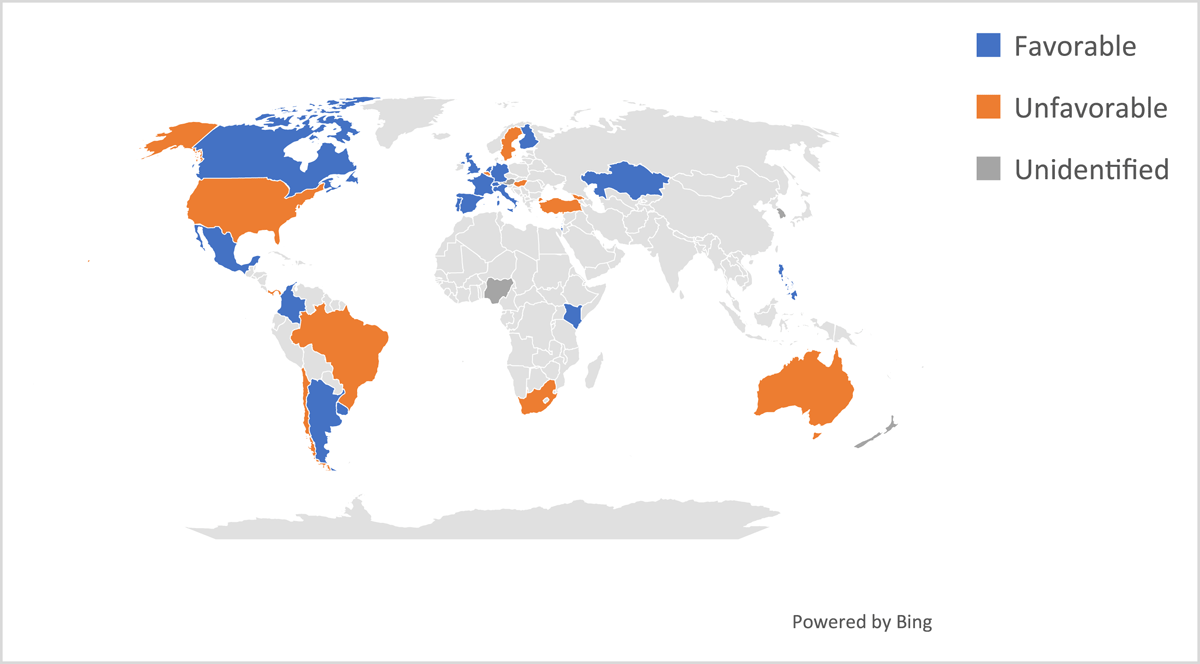

Regarding the outcomes of litigation, when assessing the direction of the decisions analysed per jurisdiction, the results are scattered, as observed in Figures 3 and 4. Specifically, regarding the issue of employment status (see Figure 3), a group of countries exhibits a tendency towards recognizing some labour rights for platform workers. This is achieved either by acknowledging them as employees or by categorizing them as a third category, as specified in national law – e.g., “workers” in the UK, or “lavoro etero-organizzato” in Italy-. A second group of jurisdictions displays a certain inclination towards the status of independent contractors. Finally, there are jurisdictions where the decisions are so dispersed, and the ratio is so close that it is not possible to establish a tendency. (A more comprehensive table is available as an addendum to this paper.)

Figure 3

Success Rate of Litigation on Employment Status by Workers Per Country Available in Author’s database.

Source: Author’s elaboration.

Figure 4

Success Rate of Litigation by Workers Per Country Available in the Author’s Database.

Source: Author’s elaboration.

Workers were more successful in bringing their claims in countries like Spain, Italy, and the Netherlands. In turn, judicialization of the conflict resulted in less favourable outcomes in Brazil and Australia. No clear trend can be identified in countries such as Austria, New Zealand, Nigeria, and South Korea.

Examining the courts’ positions exclusively regarding the classification of platform workers reveals a marked tendency towards employment status in the Netherlands, France, Spain, and Argentina. It should be noted that, at the time of writing, some decisions issued by the Dutch courts following the last update of the mapping have been less favourable to the Dutch trade union (e.g., the Uber and Temper cases), marking a step back from the precedent that recognized platform workers as employees.

In contrast, a tendency in favour of independent contractor status is seen in countries such as Australia and Brazil. However, the trend appears to be shifting in Brazil –and is presumably going to continue to do so with decisions like the one from the Supreme Court favouring the employment status of Uber drivers in 2022–.40 Finally, courts have favoured an intermediate category in jurisdictions such as Italy and the UK.

These ongoing developments show that this topic remains a moving target, and even in jurisdictions where the position once appeared settled (such as the Netherlands or Brazil), the judicial debate over the misclassification of platform workers is still unfolding.

There are also jurisdictions where a clear trend could not be identified due to a scarcity of decisions combined with a lack of uniformity (e.g., Belgium or Chile). The absence of cases may hinder a shift in the judges’ position. Examples in jurisdictions with a higher number of cases (NL, ES, IT, BR) show that, although initially judges favoured the classification of platform workers as independent contractors, the evolution led to a shift in the judiciary’s opinion.

Initially, judges had a superficial understanding of the platform business model and how algorithms work;41 however, they later gained knowledge and improved their understanding, as shown in the reasoning behind their decisions.42 Examples of this shift can be seen in jurisdictions worldwide, both in the GN and GS.43 Naturally, this change is not exclusively shaped by the judiciary and is also influenced by other sources of power, such as legislative reforms that will be discussed below (institutional power) and societal pressure to improve the working conditions of this workforce (ideational power).

However, this shift requires cases to reach the courts, which, in several jurisdictions, platforms have hindered by employing a practice that could be termed “strategic conciliation” or “manipulative conciliation.” 44 This practice was identified by national experts such as Palomo in Chile45, de Sena et al in Brazil46 and Cherry in the USA.47 Although several lawsuits were lodged, they never reached a judgment, as digital labour platforms are alleged to have resorted to settlements on repeated occasions to avoid adverse legal precedents from arising. This practice seemed pivotal in avoiding the consolidation of an adverse judicial precedent in some jurisdictions, such as Brazil, Australia, Chile, and the USA, where the general direction of the jurisprudence remains unfavourable or unclear at best.

2. Social Dialogue

The mapping conducted identified 95 social dialogue initiatives in the platform economy. This is significant considering the widespread use of regulatory arbitrage in the platform economy,48 among other obstacles faced by platform workers that foster a barren environment for collective representation and social dialogue.49

As observed in Table 1 (supra), the higher presence of institutional responses in the GN is most noticeable in social dialogue, where over 88% of the initiatives identified are located in the GN, primarily in Europe. In the GS, although scarce, most initiatives were identified in Latin America.

Regarding the material scope of the agreements, Figure 5 shows the topics addressed and key provisions included in the different social dialogue initiatives.

Figure 5

Topics Addressed in Social Dialogue Initiatives Available in the Authors’ Database.

Source: Author’s elaboration.

Remuneration was the most frequently regulated issue in social dialogue. It has been a highly contested issue in some agreements, for instance, in the French and Italian systems, as it has raised questions about whether it has been disadvantageous for the workers.

The French example refers to an income agreement reached on April 20, 2023.50 This agreement was finalized between the ‘Association des Plateformes d’Indépendants’ (API), which represents platform companies, and several new workers’ organizations.51 This income agreement has faced heavy criticism from traditional unions such as ‘CGT,’ which argues it sets the delivery drivers’ hourly pay at 11.75 euros per hour of actual work. Representatives of ‘CGT’ claim this rate applies only during the ordering process. However, waiting times are not considered part of working hours. A representative from ‘Uber Eats’ clarified that waiting at the restaurant and the travel time to the restaurant are included.52 Nonetheless, this does not account for all the waiting time workers experience, as over half (52%) of delivery workdays involve waiting because the platform does not assign enough orders.53 Therefore, delivery workers often wait long periods for orders, and this waiting time is not covered by the agreement. In Colombia, a very similar pay scheme, included in an agreement between Rappi and Unidapp, stipulates a minimum pay of 3,050 Colombian pesos per delivered order.

In turn, in the Italian case, the ‘Assodelivery’ and ‘UGL’ collective agreement recognized in Article 7 that riders were classified as self-employed. Moreover, Article 10 stated that riders will be compensated based on the deliveries completed. This was agreed upon despite platform workers being covered by employment protections, including a statutory minimum hourly wage (Law No. 128/2019, known as the Riders’ Decree). This agreement was considered unlawful by the Court of Florence, ruling No. 781/2021, as the court found ‘UGL’ acted as a “yellow union”.

These collective agreements have raised questions as they were deemed detrimental to the workers. The underlying issue in these agreements is that of unpaid labour performed by platform workers, as the agreements establish a pay-per-delivery instead of a minimum hourly wage that recognizes the entire time it takes the worker to perform their job.

Following remuneration, although not related to a specific issue, agreements aimed at regulating the entire sector were the second most common. Examples include the ‘Logistics National Collective Bargaining Agreement’ that applies to ‘Just Eat’s’ workers in Italy, the LO and Foodora sectoral collective agreement in Sweden, the agreement reached by the ‘Sindicato de Comercio’ with ‘Pedidos Ya’ for drivers to be covered under the collective agreement for catering services in Argentina, the sector-based Memorandum of Understanding for ride-hailing companies in Kenya, and the sectoral agreement for delivery drivers adhered to by JustEat in Denmark.

Ilsøe and Söderqvist analysed two of these sectoral agreements, namely JustEat in Denmark and Foodora in Sweden, when examining the Nordic model in the platform economy. They assessed that there is still a long way to go as most platforms do not adhere to the agreements, and choose to remain outsiders to the system. The scholars acknowledge that both food delivery platform companies hired platform workers as employees, engaged in collective bargaining, and voluntarily shared rulemaking capacity with organized labour, ultimately becoming first movers and shaping future sectoral norms, thereby exercising significant rulemaking capacity. However, they also noted that a sectoral agreement with a single signatory company does not meet the requirements of full Nordic IR-system integration. Consequently, a pertinent challenge remains integrating competitors such as Wolt, who may insist on continued IR-system evasion due to the existing collective agreement being a poor fit for their business model.54 This particular analysis can be applied (with saved proportions) to other sectoral agreements found in the platform economy, as most of them share the condition of being concluded with a single signatory company, with multiple competitors choosing to remain outside the system. Therefore, these agreements, in general, although exhibiting some progress in the working conditions of workers on specific platforms, remain with many challenges ahead for the sector.

The different social dialogue initiatives also frequently included provisions on occupational health and safety, automated decision-making, social dialogue, social security, and working conditions.

Geographically speaking, most agreements identified in the GS were in Latin America, mainly in Chile, Colombia, and Argentina. The main issues addressed in said agreements were remuneration, social security, deactivation procedures, representation, and OSH.

Traditional and grassroots unions were important actors in negotiating collective agreements in the GS, the latter having a role just as significant as the former. The state also had a prevalent role in this regard in the GS vis-à-vis the GN. Although the state participated and promoted social dialogue in the platform economy in the GN as well -e.g. the Charter of Fundamental Rights of Digital Labour in the Urban Context with the intervention of the municipality of Bologna in Italy and the Voluntary Charter that included ten road safety principles that aim to keep motorcycle couriers and other road users safe in the UK, with the participation of Transport for London- in relative numbers, it displayed a minor role compared to the GS. In the GS, the state’s participation was decisive in the agreements signed in Kenya, Colombia, and Argentina. This exhibits that collective actors and industrial relations systems in the GS are more reliant on state-given institutional power, whereas in the GN, social partners and IR systems retain a higher degree of autonomy.

The (even greater) lack of power and autonomy of platform workers and their representatives within social dialogue processes in the GS is reflected both in the voluntary nature and content of the scarce initiatives concluded. For instance, the memorandum of understanding between riders and several ride-hailing companies in Kenya was a non-binding instrument that did not result from a collective bargaining process.55 In turn, in Colombia, the platform workers’ trade union ‘Unidapp’ was founded in 2020 with the support of the traditional organization ‘Central Unitaria de Trabajadores’. The delivery platform ‘Rappi’ had been refusing to recognize or negotiate with ‘Unidapp’, leading to ‘Unidapp’ filing a complaint before the Ministry of Labour.56 The intervention of the Ministry of Labour, which facilitated the parties’ bargaining, ultimately led to the conclusion of a first agreement in February 2024 addressing issues of minimum remuneration, account deactivation, and union recognition, despite the workers still being regarded as independent contractors. In the country’s first-ever agreement in the platform economy, ‘Rappi’ recognized ‘Unidapp’ as a trade union. The involvement of the Ministry of Labour was a crucial factor in reaching this agreement.57 Both the Kenyan and the Colombian agreements classify the workers as self-employed. Similarly, the conditions under which a company-level collective agreement was reached in Chile suppose a rare case, unlikely to be replicated, as it was concluded under the wings of a domestic start-up (’Cornershop‘) that employed its workers and fostered collective dialogue before ‘Uber’ -which holds an opposite position- acquired the company.58

Another notable development in the social dialogue scene is the role of global unions, such as the International Transport Workers’ Federation (ITWF), which has signed two framework agreements with Uber: the Memorandum of Understanding and the Global Safety Charter for Couriers. Said agreements paved the way and subsequently led to national affiliates of the ITWF signing national agreements at the domestic level, namely in Belgium, the UK, and Spain.

It is worth noting, however, that these agreements are not always concluded through the traditional collective bargaining procedure, and furthermore, the issue of employment status is not typically discussed. Both parties to the agreement acknowledge they do not see eye to eye on the issue of the classification of the platform workers but express their commitment to work for the improvement of other aspects, such as the right to freedom of association and bargaining, flexibility, and open access to the uber application, occupational health and safety, working conditions, social protection and dispute mechanisms which include deactivation and data rights.

Despite the progress made by this worker’s organization in reaching a macro-level agreement, these efforts have so far only produced effects in the GN. Affiliate organizations to the ‘ITWF’ in Spain,59 Australia,60 the UK,61 and Belgium62 have reached agreements at the domestic level. This has been much harder to accomplish in some jurisdictions in the GS, as exemplified by an African case. Notably, in Kenya in 2018, members of the ‘ITWF’ attempted to unionize Uber drivers together with the Digital Taxi Forum. However, they were not successful, as drivers preferred the grassroots organizations that had spontaneously formed in the community.63 Literature on platform workers’ organization in the GS shows that the Kenyan example is part of a larger trend of informal collective action, grassroots organizing, and even the creation of alternative platforms in this region.64 This informal collective action partially explains the lesser degree of collective bargaining, as research suggests that there is little grassroots action in the platform economy, resulting in practical, long-term improvements in workers’ working conditions.65

The minor presence of social dialogue outside of Europe, which was most pronounced in the GS, together with the struggles identified when structures attempt to foster it, such as in the Kenyan case, contributes to reinforcing arguments elucidated by Nowak that stress the Eurocentric focus of traditional trade unions and collective negotiations, which do not have an equally prevalent role outside of Europe.66 This also results from the existing legal barriers (observed in both GN and GS regions) that restrict platform workers and the broader self-employed population from accessing structures of worker representation, such as trade unions. (See e.g., APP trade union in Argentina or The App-Based Drivers Union of Bangladesh).67

This strategy by global unions such as the ‘ITWF’ managed to get Uber to the negotiation table—a task that itself is an achievement—and resulted in agreements with them, so far within different jurisdictions of the GN. The agreements addressed issues related to working conditions but did not include the issue of misclassification. These agreements can be classified as “staircase agreements.” This concept, initially developed by Ilsøe, Jesnes, and Munkholm in the Nordic context and later recaptured by Lammanis on a broader European scale, refers to agreements designed as a first step, leaving open the possibility for gradual improvements in protections through subsequent renegotiation.68

However, not all affiliates and organizations agree with this strategy. Some organizations argue that platform workers are wrongly classified and, therefore, should be granted full employment status with all the consequent rights that come with it. Thus, they consider negotiating below this threshold as watering down the rights of platform workers. A notable example is the FNV in the Netherlands. The biggest trade union in the Netherlands has assumed a position, which became apparent in the aftermath of the collaboration agreement signed between the hospitality division of the ‘FNV’ –‘FNV Horeca’- and ‘Temper’ in 2018.69 Subsequently, reports of tensions emerged between ‘FNV Horeca’, ‘FNV ABU’, and ‘FNV Flex’. The latter two departments of the ‘FNV’ perceived the collaboration agreement as undermining the union’s efforts to fight bogus self-employment, as they claim ‘Temper’ operated as a temporary employment agency instead of as a freelance platform, underpaying workers who are falsely defined as freelancers.70 It should also be noted that the Dutch industrial relations system is known for its widespread use of the extension mechanism in collective agreements. This instrument provides a solid basis for trade unions to refuse to bargain for lower standards, especially within a sector where a generally applicable standard exists. Arguably, these factors led to a clear focus on the FNV’s use of strategic litigation to combat misclassification, which has so far been successful in its results, as seen in Section 2.1. Nonetheless, it should be noted that at the time of writing, some decisions issued in the Dutch case after the mapping was last updated have been less favourable to the Dutch trade union (e.g., Uber and Temper cases).

Other actors who have engaged with these so-called staircase agreements, only in rare circumstances, can be seen in the Nordic systems. This was the case of the ‘Hilfr’ collective agreement, which was conceived as a first step, leaving the door open to a gradual improvement in protections through subsequent renegotiation. However, as explained by Ilsøe and Söderqvist the exceptional background to the agreement created the premises for this model, such as the fact that the cleaning market in private households was unregulated and affected by a large amount of undeclared work.71 This is believed to have made it easier for the union to conclude an agreement with less protection than usual (and make it acceptable), ‘a “lesser” agreement being preferable over no agreement’.72 However, generally speaking, this constitutes the exception rather than the rule in the Nordic model.

Nevertheless, it must be noted that systems such as those in the Nordic and Dutch regions are known for their strong presence of social dialogue and social consensus.73 Therefore, the higher degree of power of these collective actors and the surrounding systems allows social partners to reject gradual routes, compared to systems assembled differently, predominantly but not exclusively in the GS, where this “staircase approach” could be an interesting alternative.

Overall, reflecting on the approaches observed and the content of the agreements reviewed, it can be assessed that a large number of agreements concluded within the platform economy are negotiated outside traditional collective bargaining systems and procedures. As observed, at times, this led to tensions emerging on whether these gradual approaches are better than nothing at all or, on the contrary, contribute to watering down existing employment protections. It is valid to question whether these agreements are materially improving the working conditions of platform workers in a significant way, or if they are merely temporary fixes that contribute to these companies remaining in the “exceptionalism” on which their business model has been based so far. Although this analysis does not provide a definitive answer to this question, it does propose that the industrial relations system and broader context in which these agreements are taking place are relevant factors for setting a strategy forward.

3. Legislative Reform

As observed in Table 1, legislative reform initiatives were significantly less common in the GS. For instance, Africa has close to no regulation on this matter. Most African nations have not enacted specific laws pertaining to the gig economy, even though there are an increasing number of allegations of abuse linked to the sector.74

This contrasted with the global North, where not only more initiatives were identified, but some of them had a wider reach. A quintessential example of this can be observed in Europe, where the PWD has been approved and will be implemented across the 27 EU member states.

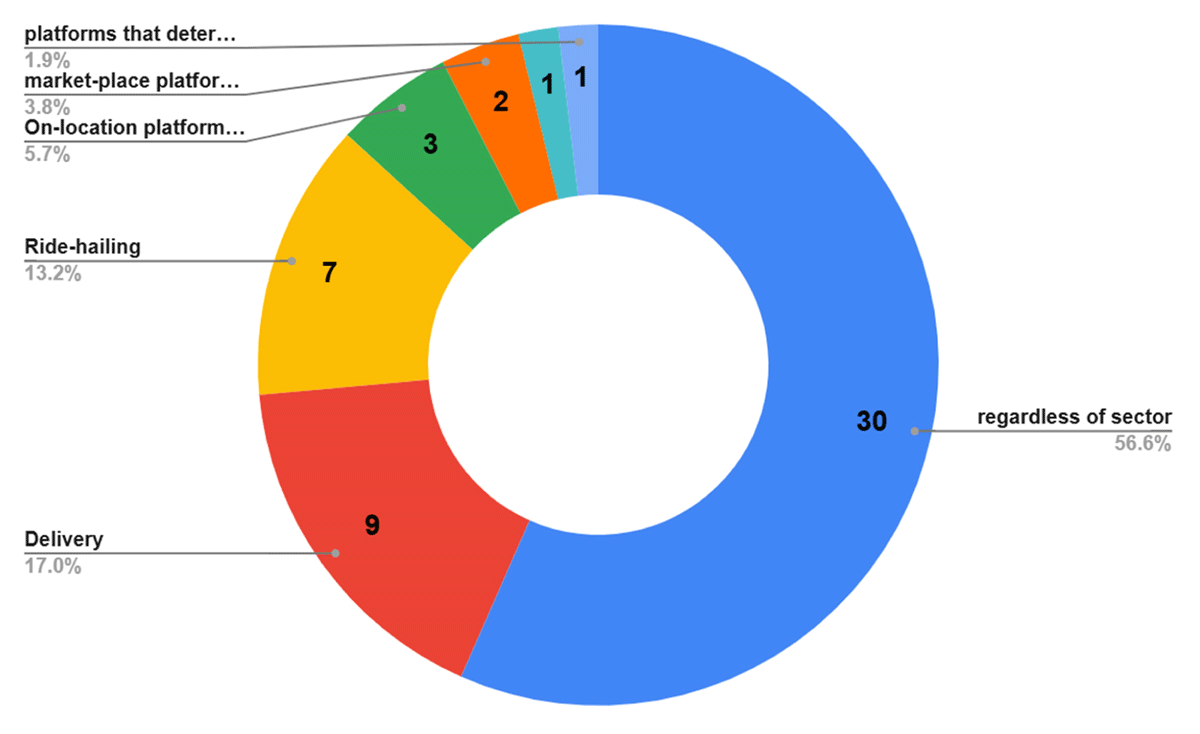

Regarding the material scope, among the diverse legislative initiatives identified, the employment status of platform workers was the most frequently addressed subject, followed by initiatives related to social dialogue and workers’ representation. Working conditions, occupational health and safety, and social security were other frequently identified matters. (See Figure 6)

Figure 6

Main Subject Addressed In Legislative Initiatives Available in the Authors’ database.

Source: Author’s elaboration.

Regarding the status of platform workers and how it has been regulated, the trend is far from uniform, and different stances have been adopted by the countries regulating it.

A block of jurisdictions have introduced presumptions of an employment relationship. These are Belgium,75 Spain,76 Portugal,77 Croatia,78 Malta,79 and most recently, the European Union.80 Although later rendered inoperable with Proposition 22, the state of California introduced the AB5.81 Argentina has approached this stance; nonetheless, the law has not yet been effectively implemented, and several legal actions have been taken against it.82 In turn, Finland’s approach introduced some criteria to distinguish self-employment from dependent employment more clearly.83

In contrast, in other regulatory frameworks, platform workers are classified as independent contractors. This includes several states in the USA, including Utah,84 Iowa85 and California with Proposition 22,86 and the province of Mendoza in Argentina.87 Countries such as Greece88 and Chile89 have introduced two categories of platform workers: those who perform work under an employment contract and those who perform it as independent contractors. Thus, they hold a similar stance and are open to the classification as self-employed.

Finally, there is a group that creates an intermediate category for platform workers, extending them certain rights. France,90 Italy91 have adopted legislation in this sense. However, it remains to be seen how some EU member states, such as Greece and France, will adapt their current regulations in response to the implementation of the new EU directive on platform work.

Broadly speaking, there is a greater emphasis and will to regulate employment status in the GN, especially when contrasted with the GS. On the other hand, the issues regulated in the GS so far pertain more frequently to other matters not directly related to employment status, such as social security (India,92 Uruguay93 and Colombia94), occupational health and safety -especially during Covid- (Brazil95, Peru96), working conditions, AI/AM and data protection (Brazil,97 Colombia98, Nigeria99), anti-harassment and discrimination, and even an ordinance that incentivizes platform work (Pernambuco, Brazil100). Although some legislative projects have been identified in the Latin American region, aiming to regulate employment status, such as in Mexico,101 Colombia,102 and Uruguay,103 the necessary political will has not yet been sufficient for their enactment. The larger presence of informality and unemployment rates in the GS accounts for this regulatory trend to some extent, as regulations seem to adopt a more neoliberal approach. At times, not only by allowing it in the terms proposed by platform companies but by incentivizing it, as seen with Pernambuco.

Another trend identified from a regulatory perspective is the intention to advance algorithmic management, AI, and the rights of platform workers to access their personal data. The EU is leading this matter, with the PWD, which includes an entire chapter establishing new algorithmic management and data rights (most of which also cover self-employed workers)104 and the AI Act. It could be argued that the former places platform workers in a privileged position, even in comparison to traditional workers, concerning algorithmic management rights. Although research widely exhibits platform workers face considerably more precarious conditions than traditional workers in a large set of labour rights, with regards to algorithmic management, the opposite is the case within the EU, as this Directive provides specific rights such as to receive adequate information about the algorithms used to hire, monitor and discipline them, a right to request human review, inter alia, applicable specifically to persons performing platform work. There is also a growing interest in this issue, as identified in the GS, with examples in Brazil,105 Nigeria106 and Colombia.107 The ILO has included this as a key issue in the Draft Convention (Sections X, XI, XII) and Recommendation (Sections VII and VIII), acknowledging the significant implications of the use of automated systems based on algorithms or similar methods for the working conditions of digital platform workers. This is certainly one of the most promising aspects that the international labour standard could bring forward in terms of new protections for this workforce, especially in the GS, where data protection regimes are still in their infancy.

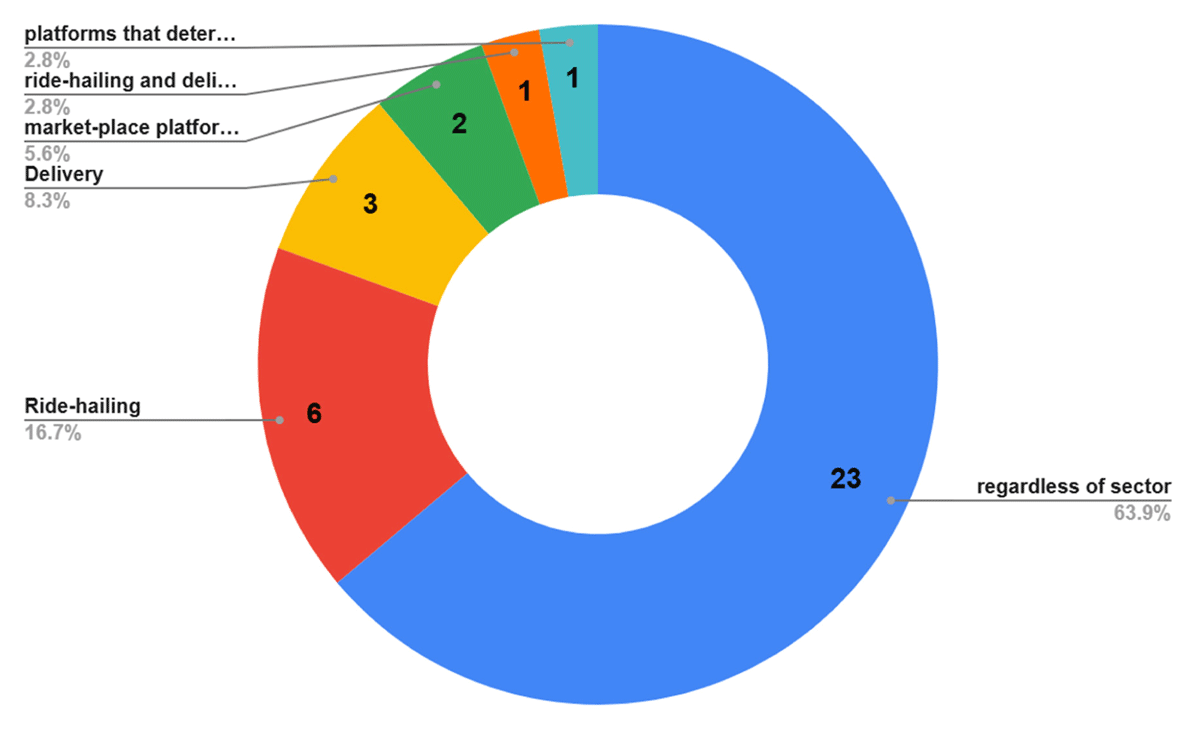

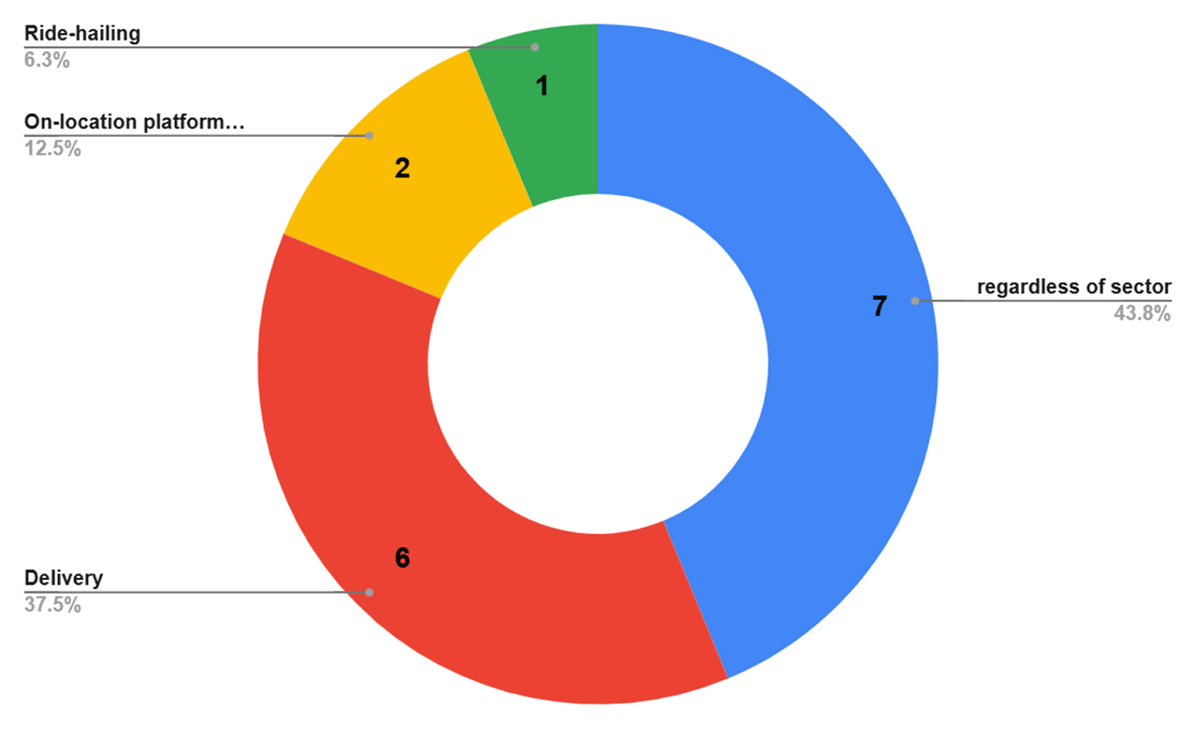

Finally, a common pattern observed in the mapping of both the GN and GS was that platform work was more prone to regulation in specific types and sectors, predominantly in on-location platform work. Close to half of the regulatory initiatives identified aim to address the conditions of platform workers performing services in specific sectors, such as ride-hailing, delivery, and, to a lesser extent, care, cleaning, and household services. All these sectors are included within the realm of “location-based” platform work.108 (see Figure 7)

Figure 7

Legislative Reform Initiative Cases By Sector Available in the Authors’ database.

Source: Author’s elaboration.

This regulatory focus on location-based platform work was even more noticeable in the GS (see Figures 8 and 9). Thus, online platform workers are not covered by a large percentage of the legislative initiatives adopted.

Figure 8

Legislative Initiative Cases By Sector in Global North Available in the Authors’ database.

Source: Author’s elaboration.

Figure 9

Legislative Initiative Cases By Sector in Global South Available in the Authors’ database.

Source: Author’s elaboration.

In general, this suggests a tendency for legislative reform to focus on specific companies and sectors in location-based platform work, particularly those with prominent visibility. Several authors have previously highlighted this trend in different national systems.109 Meanwhile, the exclusive focus on riders has inadvertently overshadowed other forms of platform work, which at times represent the majority of individuals working via digital platforms – e.g., crowd workers.110

Thus, social policy and legislative reform so far remain narrow in scope, targeting specific sectors in which platform work is most ‘visible’, such as ride-hailing and delivery services. This exhibits tunnel vision on how challenges are tackled.

This more prominent focus on location-based platform work in the GS is of concern, considering there are major players in the platform economy—especially in terms of labor recruitment in crowdwork and click work—located in the GS, such as India and the Philippines.111 Therefore, to address the precarious conditions in online platform work, it is necessary that the scope of regulation be broad enough to consider all forms of platform work and that these regulations are not geographically limited to the GS.

Unfortunately, regulations with limited geographic scope within countries in the GN cannot improve working conditions for those working offshore, which is a significant portion, and this trend is likely to continue due to the phenomenon of labour deterritorialization. Moreover, a great portion of the regulations enacted in the GS leave online platform workers outside the scope of protection.

The ILO’s commitment to adopt an international labour standard on platform work could be a timely instrument to shed light on this issue, broadening the scope of protection to a wider range of platform workers. In fact, the ILO appears to seize the opportunity provided in the Draft Convention Article 1(a)(ii), which states that it applies to digital labour platforms “regardless of whether that work is performed online or in a specific geographic location.”

Finally, while this paper advocates a tailored approach that accounts for regional contexts, this should not be confused with excessive flexibility or vagueness that could compromise the instrument’s effectiveness. Provisions such as Article 10 of the Draft Convention—which states, ‘Each Member shall take measures to ensure the correct classification of digital platform workers in respect of the existence of an employment relationship’— risk being too broad, potentially hindering enforcement. To ensure meaningful progress, more concrete measures are needed (see, for example, the concluding remark on page 32.)

Section III: Concluding Remarks

Aiming to contribute to the construction of an international labour standard on platform work, this paper sought to examine how various domestic institutional systems—such as judicial, industrial relations, and legislative systems—have responded to the presence of platform work thus far. It also reflected on the factors that may have influenced these responses, considering the wide variety of contexts in the global North and South.

Following the prevailing literature, this paper theorizes that diverse socio-economic contexts and labour markets influence how such systems and domestic institutional frameworks respond to (or approach) platform work. Factors such as the share of informal employment and access to the traditional sector play significant roles in this context. This becomes more evident when comparing countries from the GN with those from the GS. A study conducted by the National Institution for Transforming India highlights that informality is notably high in the GS compared to the GN. While countries like the USA (18.6%), UK (13.6%), and Spain (27.3%) have relatively small informal sectors, the GS shows contrasting figures, with India (93%), Indonesia (85.6%), and China (54.4%) exhibiting high levels of informality.112 Informality is also substantially higher in Latin America (50%)113 and Africa (85.8%).114 This situation is further worsened by the large populations of many countries in the GS.115 Therefore, the labour market and lack of job opportunities may significantly push vulnerable workers into platform work, both in the global North and South—though this is more pronounced in the South.

ILO surveys also indicate that, although not being able to find traditional work is a motivation for workers to opt to work in the platform economy in both developing and developed countries, better pay than in other available jobs is particularly relevant for those in developing countries.116 Further studies find that in wealthier economies, such as the US and the EU, supplemental income and flexibility are the primary motivators for workers to enter platform work. In contrast, in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, workers are more motivated by income and a lack of alternative employment opportunities.117 Nevertheless, precariousness within platform work remains a common factor in both regions.118

More so, in economies flooded with informality, research from the ILO suggests platform work offers comparable labour conditions to a vast portion of the labour market—on occasions even more favourable conditions than the “traditional” labour market. Particularly in the GS, workers may find an additional incentive to perform platform work, especially on location platform workers, as in developing countries, earnings in the app-based taxi and delivery sectors tend to be higher than in the traditional sectors.119 Therefore, although they still face precarious working conditions, these can, in certain cases, be more attractive—at least in terms of earnings, as they do not account for other risks, such as social security, to mention one—than the conditions offered in traditional sectors. Hence, the purpose of platform jobs is markedly different in the GN and GS, and so are the structural challenges.

This existing literature provides important insights that help explain the notable differences revealed by this mapping exercise. Generally, institutional channels were used much less in the GS, suggesting that platform workers rely less on institutional mechanisms as a form of protest in the GS, that these channels have been less effective in this region, or both. It may also be due to the already precarious working conditions of the labour market, which lead to a less negative perception of the platform economy.

Concerning case law, a significant portion of the judicial and administrative decisions identified focused on a relatively small number of countries, without establishing a correlation between the size of the country’s platform economy and the number of decisions issued. For instance, there are countries with a high presence of platform work that, to date, have reported no or very few court cases, such as India and the Philippines. It is possible that the high degree of informality present in some of these countries, even within the traditional sector, fosters a different perception towards platform work. Although labour unrest is identified in similar exercises, such as the Leeds Index of Platform Worker Protest, these mobilizations often emanate from other grievances associated with more immediate requests. Examples include reactions against unilateral measures taken by the platform that impact workers’ earnings, responses to an accident resulting in deadly consequences for a worker, reactivation of workers’ accounts, coverage against occupational accidents, and the risk of infection during the COVID-19 pandemic. These mobilizations are usually conducted through short-span protests that quickly exhaust their fuel and seldom lead to the use of any form of institutional channels, such as litigation. In addition, the lack of judicial decisions may also be due to the lower access to prompt justice and procedural and judicial safeguards.120

Individual platform workers were the primary actors in litigation, typically filing lawsuits to demand that they be classified as employees. Important differences in the degree of precariousness were identified within case law. For example, in the GN, several decisions identified workers who were already employed, requesting claims such as work equipment in Germany, unfair dismissal in Sweden, and the application of the collective agreement in Spain. This exhibited a higher degree of protection. These claims were not commonly identified in the GS.

State actors played a significant role in judicial and administrative procedures in the GN. The state, through social security institutions and, to a lesser extent, tax authorities, played a prominent role, especially in welfare states, as these institutions were directly impacted by the lack of contributions. This made social security a significant claim in the development of case law in the GN region.

Collective actors also played a significant role, which was more evident in the GN, in bringing claims beyond platform workers’ employment status to court. These included the applicability of the collective agreement, data protection and algorithmic management rights, work and safety equipment, the need to reactivate accounts during COVID-19 to ensure subsistence, and the request to secure their right to work when the platform was suspended. Some of these claims, such as those relating to work equipment or data protection, are less critical than the issue of misclassification. While the former generally arise within a recognized employment relationship that already grants workers a baseline of contractual and statutory protections, misclassification denies workers that status altogether and thus excludes them from the full range of labour rights and social protections. This makes misclassification a more fundamental and far-reaching violation.

These smaller claims sought to improve working conditions that were relatively less serious violations of workers’ rights and were much less identified as the main cause of litigation in the GS. This suggests that platform workers in the GN have a higher level of rights accessible to them compared to those in the GS.

In turn, regarding the development of social dialogue, significant differences were observed between the GN and GS. The scarce presence of social dialogue in the GS is the most notable. This is the case despite efforts from global confederations, such as the ITWF, which depend greatly on national affiliates and positions from platform companies at the domestic level. Nevertheless, efforts from this confederation have yielded significant results on the platform economy. So far, these have been geographically limited to the GN.

Despite the low number of agreements in the GS, state intervention has been crucial in facilitating the completion of several agreements in this region. This hints towards a greater reliance of social partners on state-given institutional power in the GS.

A common trend observed in social dialogue within the platform economy was the frequent subscription of voluntary agreements and nonbinding memorandums, referred to as “staircase” agreements, outside the traditional collective bargaining systems and rejecting the status of employees. Serious doubts have been raised about the genuine improvement in working conditions under these agreements. It could be argued that these agreements are better suited for systems where contextual circumstances do not allow for a higher degree of protection. Stronger systems with well-consolidated social partners may be in a position to metaphorically “put their foot down” and not bend to these platforms’ business models, which rely on exceptionalism. Conversely, in a system where this workforce is fully unprotected, and a great percentage of the conventional workforce is also in informal employment, these schemes may be possible to guarantee a higher floor of rights. For these cases, perhaps this staircase approach may be a particularly useful tool.

Finally, regarding legislative reform, diverse positions were identified. Governments reacted differently. Some countries have yet to introduce any form of legislation. This was common, for example, in the African region, likely because the urgency to address the issue could be less pressing than in the GN, given the already large informality present, as well as the fear of scaring away much-needed foreign investments.121 Other countries, although opting to regulate it, adopt a more permissive and typically neoliberal approach, as seen in the Chilean example, where individuals are allowed to be classified as self-employed.122 In turn, in India, the regulatory approach centers around the issue of social security. Finally, other examples, such as the EU or Spain, have opted for a greater degree of protection by including a presumption of employment. These differences could potentially be explained by looking at the diverse socio-economic realities of the GN and GS. For example, abundant research—especially in the GN—warns about the risks platform work presents to labour and social standards.123 Conversely, although acknowledging the precarity of the jobs it generates, some studies, for instance in Africa, highlight the opportunities platform work can pose to reduce unemployment and provide a means out of the informal sector.124 Moreover, some research, primarily in so-called developing countries, has suggested that with the proper policy actions, platform work and digitalization can drive structural transformation.125 Although it should be taken with a grain of salt, some optimists suggest that online work and AI could become a powerful equalizer, eliminating the need for physical migration, driving economic growth, addressing demographic challenges in developed countries, and reducing global income disparities.126 This, of course, demands ethical practices from companies driving the transformation, or else it risks fatal outcomes, opening the door to what Spilda et al denominate “The unmagical World of AI.”127

A pattern was also observed, indicating a regulatory focus on on-location platform work. This was more noticeable in the GS. It risks overlooking the precarious conditions in online platform work, of which the GS is a major provider. Research from the Oxford Internet Institute on remote platform work reveals that millions of workers offer services such as logo design or software development remotely via digital marketplaces, yet their presence is often overlooked in many of these initiatives.128 This underscores the need and opportunity to expand regulation to cover all types of platform work in future instruments by the ILO, and to ensure these rules are not limited geographically to the GS. The ILO’s intention seems to be to seize this opportunity, as shown in the Draft Convention Article 1(a)(ii).”

These differences in the responses of institutional mechanisms across the various regions examined here provide relevant considerations for the debates on the ILO’s adoption of an international labour standard on decent work in the platform economy. They exhibited the widely diverse contexts within the GN and GS regions – despite the heterogeneity that prevails within these regions as well – that demand an adjustable approach by the ILO that considers this divergence. To be successful, the instrument should provide several avenues for compliance with the labour standard (or allow for derogations and flexibility); otherwise, it risks setting too high thresholds for GS countries, which may result in reduced ratification or compliance with the instrument.

A useful precedent for flexible regulatory design can be found in the EU’s Fixed-Term Work Directive,129 which allowed Member States to choose among three safeguards against the abuse of successive fixed-term contracts—objective justification, maximum duration, or a limit on renewals—requiring adoption of at least one. Similar modular approaches exist within ILO governance frameworks, such as Convention No. 102 on Social Security Article 2,130 which permits states to select at least 3 of the 9 branches of social security to comply with. This kind of multi-track or modular compliance model, tailored to national contexts, could be well-suited for establishing universal rules on platform work. Rather than mandating a blanket presumption of employment—which may be unworkable for some countries, particularly in the Global South—alternatives like a rebuttable presumption, a reverse burden of proof, or clearly defined classification criteria could offer meaningful flexibility while promoting effective implementation.