Introduction

For several decades, data has been considered a potent propeller of economic growth and innovation. In parallel, with the ever-increasing digitalization of public services, governments have become some of the biggest producers of data (Attard et al., 2016). In this context, Open Government Data (OGD) has incrementally been considered as a strategic resource to be made available for reuse. OGD is data produced by the public administration, made available to access, modify, share, and reuse by anyone without restrictions (Federal Chancellery, 2025). In the early 2010s, both in Switzerland and in the EU, the publication of OGD has been promoted with the publication of legal frameworks such as the Public Sector Information Directive of 2013 for the EU (European Commission, 2025) and the first Open Government Data Strategy in 2014 for Switzerland (Federal Law, 2014). These directives were adopted in the pursuit of a dual objective: on the one hand stimulate economic growth and innovation, and on the other promote government transparency, and translated into the creation of online OGD portals (Attard et al., 2015).

Since then, however, OGD-related outcomes have been deemed underwhelming in several instances, with little evidence supporting their effective impact in enabling innovation and economic growth (Gascó-Hernández et al., 2018; Martin, 2014; Quarati, 2023; Ruijer et al., 2017). This lack of results has often been attributed to insufficient OGD quantity, ascribing low use to low data variety; and scarce quality, with critiques focusing on the characteristics of the published datasets (Máchová & Lnenicka, 2017; Zhu & Freeman, 2019). Indeed, despite having adopted legislation and made investments promoting OGD publishing for more than a decade, the EU recognises “the persistence of technical, legal and financial barriers lead[ing] to a situation in which public sector information in Europe is not used enough” (European Commission, 2023). To address these issues, the EU has created the concept of High-Value Datasets (HVDs), which are datasets produced by public bodies considered particularly promising in terms of potential for added-value generation through reuse. The EU Commission Implementing Regulation 2023/138 defines HVDs and provides the specific list of high-value datasets, which are characterised by their inclusion in one of six thematic domains: geospatial, Earth observation and environment, meteorological, statistics, companies and company ownership, and mobility. The HVD status implies certain publication requirements, also defined by the implementation regulation 2023/138. Namely, since 9 June 2024, public authorities must guarantee that HVDs are available free of charge, in a machine-readable format, with an application programming interface (API), and via bulk download when possible.

The HVD strategy substantially aims at prioritising the availability and quantity of the public datasets showcasing particularly high potential, hence introducing a discrimination between a subset of public sector information on which more resources need to be invested than on the rest. Following recommendations from the EU, the idea of adopting HVDs has also been evaluated in Switzerland but was ultimately discarded precisely to avoid discriminating between datasets. Instead, the Federal Statistical Office (2023) argues that the Swiss strategy is more ambitious, as the Federal Act on the Use of Electronic Means to Conduct Official Tasks (EMOTA), which came into force in 2024, indicates that all public data needs to be made available as OGD, following the open by default principle. Being published as OGD, such data would automatically comply with the HVD publication requirements (Federal Statistical Office, 2020).

Switzerland and the EU are therefore pursuing the same objective, that of increasing OGD quality. However, they adopted different strategies, with the EU relying on a dataset prioritisation strategy, while Switzerland aimed at ensuring uniform data quality across all published public sector data. By comparing the quality of published data across five EU national OGD portals and one non-EU portal, this study seeks to answer the following research question: Does the EU’s high-value dataset strategy help to increase the data quality of open government? To answer this question, we leverage the Marmier and Mettler (2020) index for measuring OGD compliance. We apply this index to a total of 318,696 datasets, of which metadata was gathered from the national OGD portals of 5 EU countries and that of Switzerland. Given the recent emergence of HVDs, little research on the topic has been produced, particularly leveraging empirical data. This article aims to address this gap by providing an early effort to empirically investigate the relationship between the HVD strategy and compliance with best OGD publishing practices.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. In the background section, we briefly elaborate on the meaning of data quality in the OGD context, its link with data reuse, and the various strategies leveraged to increase OGD reuse through better data quality. We then describe our study’s methodology, before presenting our empirical results. Lastly, we discuss our research implications and conclude with limitations.

Background

OGD quality and use

The OGD movement has, since its emergence, been driven by expectations of increasing government transparency, fostering democratic participation, and spurring economic growth (Attard et al., 2015; Dawes & Helbig, 2010). Although over ten years of research on OGD has built a growing body of evidence showing it is often underused (Quarati & De Martino, 2019; Santos-Hermosa et al., 2023), many experts continue to argue that to realize its full potential, OGD must be reused more widely (Hein et al., 2023; Zuiderwijk & Reuver, 2021). From this point of view, low data quality is frequently cited as one of the most important factors to be fixed for data reuse to improve (Janssen et al., 2012; Saxena, 2018). It is, however, important to note that, despite the consensus about its importance, data quality does not have a universally accepted definition, but rather several competing ones. Although these definitions typically take into consideration several characteristics of the data, which causes overlaps to be observable between definitions, significant differences persist. For example, certain definitions focus on the reliability, timeliness, and accuracy of the data, while others rather emphasise the value of the data per se through its relevance, usefulness, scope, and level of detail (Wand & Wang, 1996). These conceptual differences have observable practical implications, as different data sharing mechanisms (e.g., data portals) resort to different dimensions to evaluate data quality (Máchová & Lnenicka, 2017). As a result, many efforts have been made over time to clarify what data quality means in the OGD context, leading to several proposals and frameworks, some of which include metrics to measure different aspects of quality (Bizer & Cyganiak, 2009; Kim & Sin, 2011; Zaveri et al., 2015).

In their dataset quality ontology, Debattista et al. (2014) distinguish three types of definitions for data quality: results of care, conformance to requirements, and fitness for use, with fitness for use being the most widespread understanding of data quality. Given that the concept of fitness for use is highly context and data-dependent, the scholarly literature tends to adopt multidimensional approaches considering several quality dimensions (Šlibar & Mu, 2022; Wand & Wang, 1996). Coherent with this conception, we follow Marmier and Mettler (2020) in adopting a pragmatic approach that does not seek to solve the data quality definition debate, but rather uses an approximating index reflecting the best OGD publishing practices, being based on the Sunlight Foundation (SF) standards (summarised in Table 1). Indeed, the SF relies on 30 open government advocates having different backgrounds, including public administration practice, research, and internet use. Bringing together different perspectives, hence seems like a good starting point to cover a wide array of OGD intended uses, and thus to make the data characteristics fit for those uses.

Table 1

Summary of the 10 Sunlight Foundation’s principles for data quality.

| DIMENSION | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| Completeness | Resources published on open data platforms should contain all raw information and metadata defining and explaining their content. |

| Primacy | Resources published on open data platforms should also include the original information released by the government. |

| Timeliness | Resources should be available to the public in a timely manner. |

| Easy access | Resources published on open data platforms should be easy to find and download. |

| Machine-readable format | Resources should be stored in a machine-readable format (i.e., should be processable by a computer). |

| Non-discrimination | Resources published on open data platforms should be accessible without having to identify oneself (e.g., without the need to log in) or having to provide a justificatory reason. |

| Open format | Resources should be usable without proprietary software. |

| Open licensing | Resources published on open data platforms should use an open licensing model. |

| Permanence | Resources published on open data platforms should be accessible by machines and humans over time. |

| Usage cost | Resources should be available for free. |

[i] Source: Marmier and Mettler (2020).

Strategies to increase OGD reuse

In the context of open data, much emphasis is placed on the information describing the data, otherwise called metadata. Metadata is necessary for the data to be findable within an OGD portal, and hence the presence and quality of metadata is decisive for the public to access and use the data (Zuiderwijk et al., 2012). The basic idea is that improving metadata quality would make data easier to find and more accessible, which would, in turn, enhance the usability and use of data sharing mechanisms, such as data portals (Zhu & Freeman, 2019). From this principle derive different strategies aimed at improving OGD use via an improvement of metadata quality, with a prime example being that of automatically running metadata evaluations on OGD portals for continuous monitoring (Neumaier et al., 2016; Reiche & Höfig, 2013). Besides quality checks, relying on common data structures and adhering to widespread publication frameworks (such as CKAN) has also been shown to be associated with higher data quality (Máchová & Lnenicka, 2017; Vetrò et al., 2016).

All these strategies are based on the assumption that data quality drives OGD use. However, empirical results from Quarati (2023) fail to demonstrate the existence of a positive correlation between a metadata quality metric and data use metrics, such as the number of views or the number of downloaded datasets. The same study finds that differences in OGD use are much more related to data categories (i.e., their topic) than their quality. This is coherent with other analyses, notably the 2017 EU report Reuse of Open Data (European Commission, 2020).

The HVD strategy appears coherent with this perspective, as it substantially aims to focus quality increasing efforts on the data belonging to the categories which already attract the public, while avoiding spending excessive resources on datasets that would anyway not be reused enough. On the other hand, one could argue that the EU approach to HVDs does not leave much room for nuance. Indeed, with an analysis of OGD published in the USA, Zencey (2017) highlights how the popularity of data topics is not homogeneous across the country but rather varies with location. From this point of view, one could argue that the Swiss approach aiming to improve the quality of all OGD, without discriminating by category, avoids taking the risk of focusing on the wrong data topics, and hence missing out on potential reuse.

HVD identification

HVDs being a recent phenomenon, research on the topic is still in its infancy, and mostly devoted to identifying HVDs. Indeed, the notion of HVDs is not universally agreed on, but instead different organisations identify them in different ways. Indeed, in their literature review focusing precisely on the topic of HVD identification, Nikiforova et al. (2023) find that HVDs are generally defined either by their category, as is the case in the EU, or by their potential reuse. For the former, several competing definitions exist, introduced by the Open Data Directive (EU) 2019/1024, the G8 Open Data Charter and the Electronic Government Agency of Thailand. Each of them provides a list of data categories considered to hold particular high value. Although some similarities can be observed across these lists, they remain significantly dissimilar, as testified by the sheer number of categories they enumerate, being respectively 6, 14 and 9. Wang et al. (2019) use a different approach, arguing that HVDs should be defined by their capacity to meet the actual needs of potential users. Following this idea, some argue for ex-post identification of HVDs rather than ex-ante identification based on data categories. Instead, ex-post identification rests on measuring the impact of datasets which have already been published. Different methods to perform such measures exist, such as the social return on investment method proposed by Stuermer and Dapp (2016). Tseng and Nikiforova (2024) reports an example from practice: in Taiwan certain OGD publishers claim the value of a dataset lies in its popularity, measured by the number of downloads, or in the fact that potential users are willing to pay to access the data.

Methodology

Case selection

As expressed in the background section, many different, and even contrasting, conceptions of HVDs exist. Against this backdrop, the EU context benefits from a common definition, provided by the European Commission Implementing Regulation 2023/138. The EU countries hence present a unique opportunity for a transnational comparative analysis, allowing to observe the relationship between the adoption of a commonly defined HVD strategy and data quality across different national contexts. On the other hand, Switzerland considered adopting the EU HVD strategy, but rejected it on the grounds that an open by default strategy would yield a higher number of high-quality datasets (Federal Statistical Office, 2023). This contrast hence enables an empirical observation of the relationship between HVD strategy adoption and OGD quality across national settings, while comparing with a country in which that strategy has been deliberately rebuked in the pursuit of the same quality objective.

Besides the Swiss national OGD portal, the national OGD portals from which the metadata was extracted were selected following two criteria: the first being that the portal flags HVDs, and the second that the portals reflect the heterogeneity of OGD portals existing in the EU. To ensure the latter, we have selected 5 countries representing distinctly different positions in the EU’s 2024 Open Data Maturity Report. Indeed, considering the ranking by overall maturity score, and out of a total of 34 countries, our sample includes the OGD portals of Ireland (ranked 5th), Italy (ranked 11th), Austria (ranked 17th), the Netherlands (ranked 21st), and Germany (ranked 24th). We chose a comparative approach to get a better understanding of the relationship between the HVD strategy and data quality, trying to minimise the impact of any national context. Through the enabling of international pattern recognition, comparative studies are considered to have a higher potential for some degree of generalisation of findings than single case studies (Lnenicka et al., 2024; Schofield, 2009).

Data collection and preparation

The data used in this study consists of metadata associated with datasets published on six European national OGD portals. All of them use the Comprehensive Knowledge Archive Network (CKAN), an open-source management system facilitating the publishing, sharing, and use of data (Fundation, 2018). Leveraging CKAN functionalities, we were able to collect OGD metadata through application programming interface (API) get requests, specifically executed in the Python programming language, using the requests library.1

The data collection took place between 13 May 2025 and 20 May 2025 and included a total of 318,696 data resources across all 6 OGD portals. From the obtained metadata, we kept only the fields relevant to the analysis. Given that metadata completeness is measured as one of the dimensions determining the quality index of a dataset, missing values were not imputed.

HVD indicator and data categories

We relied on flagging by data publishers to identify HVDs. This flagging was part of the datasets’ metadata, which allowed us to collect this information in a binary variable called is_HVD, taking the value of 1 for datasets classified as HVD, or 0 otherwise. Furthermore, to obtain a more fine-grained analysis, we have decided to extract another variable from the metadata: category_name. The latter captures the topic of the data, often referred to as its category. Including this variable in the analysis allows to get a more detailed view of the factors associated with different data quality levels, as given that HVDs include several data topics, conducting the analysis on the category level allows for the observation of different levels of compliance with best practices among HVDs. Each dataset may belong to one or more categories. To capture this, we created a binary variable for each category present on a given OGD portal, which is equal to 1 if the dataset belongs to that category, and 0 otherwise.

Compliance index calculation

The objective of this article is to empirically investigate the relationship between the HVD strategy and OGD quality through a comparison within the EU and with Switzerland. The EU’s notion of HVDs rests on an ex-ante identification strategy, based on dataset category, and not on an ex-post strategy leveraging use statistics or users’ perspective. We chose to follow the same logic, focusing on dataset quality rather than impact, analysing the portals’ metadata. More specifically, to evaluate the level of compliance with the best OGD publishing practices for the different datasets present on the 6 OGD portals in our sample, we followed the methodology presented by Marmier and Mettler (2020). The latter consists of the use of 10 questions to be answered with OGDs’ metadata, and which test compliance with the 10 principles of OGD quality. The questions and the logic used for point attribution are presented in Table 2. Each question focuses on one of the 10 data quality principles, is answered by the elaboration of one or several OGD metadata fields, and results in a 0 equivalent to a no, or a 1, equivalent to a yes. To each dataset is thus associated a score of 0 or 1 for each of the 10 questions. The sum of these scores constitutes the compliance index, which is an integer spanning from 0 to 10. We then proceeded to compare the index averages of HVDs and non-HVDs, as well as to compute the correlation between category belonging and compliance level. All comparisons were done within OGD portals, rather than across, for two main reasons. First, OGD portals each present marked specificities, which would confound the comparison. For example, the dataset update frequency (i.e., how often a dataset must be updated to stay current) is never indicated on the German portal, contrary to the other portals in the sample. This would imply systematically lower compliance scores for datasets published on that portal. Second, the topic categories used to classify the datasets are also portal-specific and often lack direct equivalents across portals.

Table 2

Questions and their chaining logic.

| QUALITY PRINCIPLE | QUESTION | CHAINING LOGIC |

|---|---|---|

| Completeness | Q1: Is the metadata complete? | If the raw information and the metadata of this resource exist = 1, else 0 |

| Primacy | Q2: Is there an email address for a contact point/support contact? | If an e-mail address to contact the originator exists = 1, else 0 |

| Timeliness | Q3: Is the resource up to date? | If the dataset was last updated in time to comply with the declared update frequency = 1, else 0 |

| Easy access | Q4: Is the data available in bulk? | If a link to download the data exists, and the license for data reuse is fully open = 1, else 0 |

| Machine-readable format | Q5: Is the resource available in machine-readable format? | If the format used is machine-readable = 1, else 0 |

| Non-discrimination | Q6: Do people have limited access to the resource? | If a link to download the data exists, and the license for data reuse is fully open, and the data is machine-readable = 1, else 0 |

| Commonly owned or open standards | Q7: Is the resource in an open file format? | If the data format is open = 1, else 0 |

| Transparent licensing | Q8: Is the licensing information about the resource transparent? | If licensing information for data reuse is available = 1, else 0 |

| Permanence | Q9: Is the published resource available over time? | If a link to download the data exists, and it is different from the data access link = 1, else 0 |

| Usage cost | Q10: Is the resource freely available? | If the data format is open and the license for data reuse is fully open = 1, else 0 |

[i] Source: Adapted from Marmier and Mettler (2020).

Results

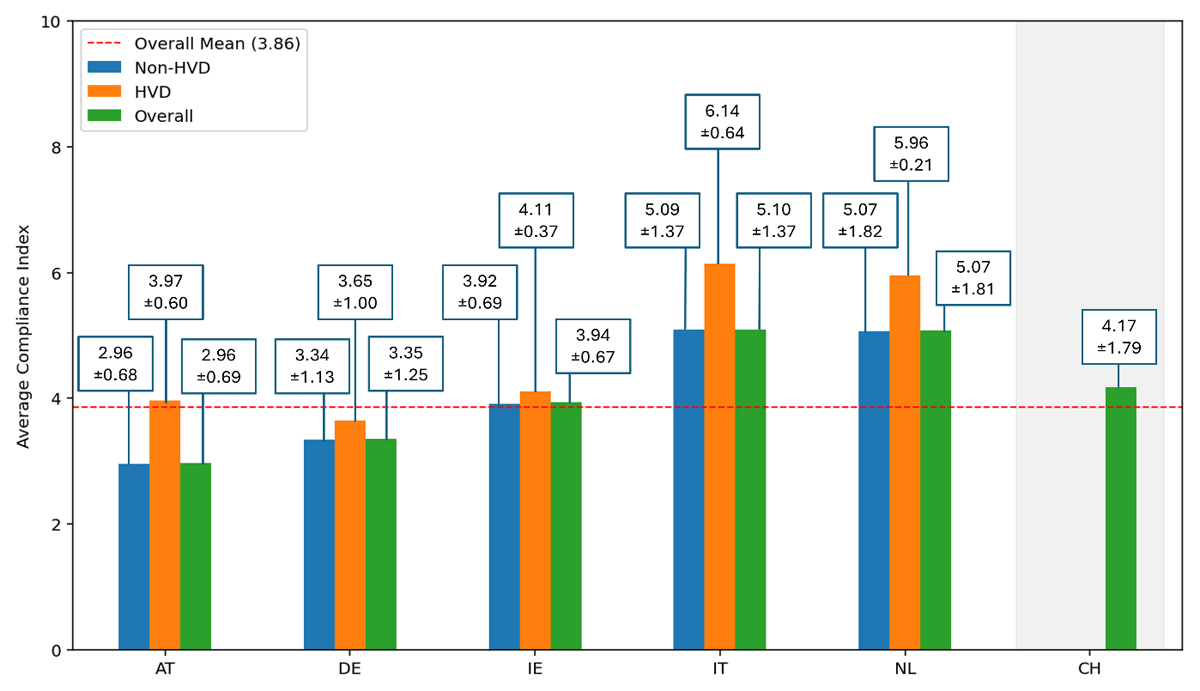

The Swiss average compliance level is roughly in line with that of the other portals in the sample. Figure 1 displays the average compliance index levels for all 6 different countries. The general average index across the sample is rather low, spanning from 2.96 to 5.10, whereas the theoretical maximum is 10. The average OGD compliance index in Switzerland is 4.17, against 5.10 for Italy, 5.07 for the Netherlands, 3.93 for Ireland, 3.35 for Germany, and 2.96 for Austria, not distinguishing between HVDs and non-HVDs. Even considering only HVDs, the average compliance index on the Swiss platform is near the average of the other countries, which is 4.76 and spans from 3.65 for Germany to 6.14 for Italy. Another interesting observation from Figure 1 is that in all OGD portals analysed, the average compliance level is higher among HVDs than among the rest of the datasets.

Figure 1

Average compliance index and standard deviation per country and per dataset type (HVD and non-HVD).

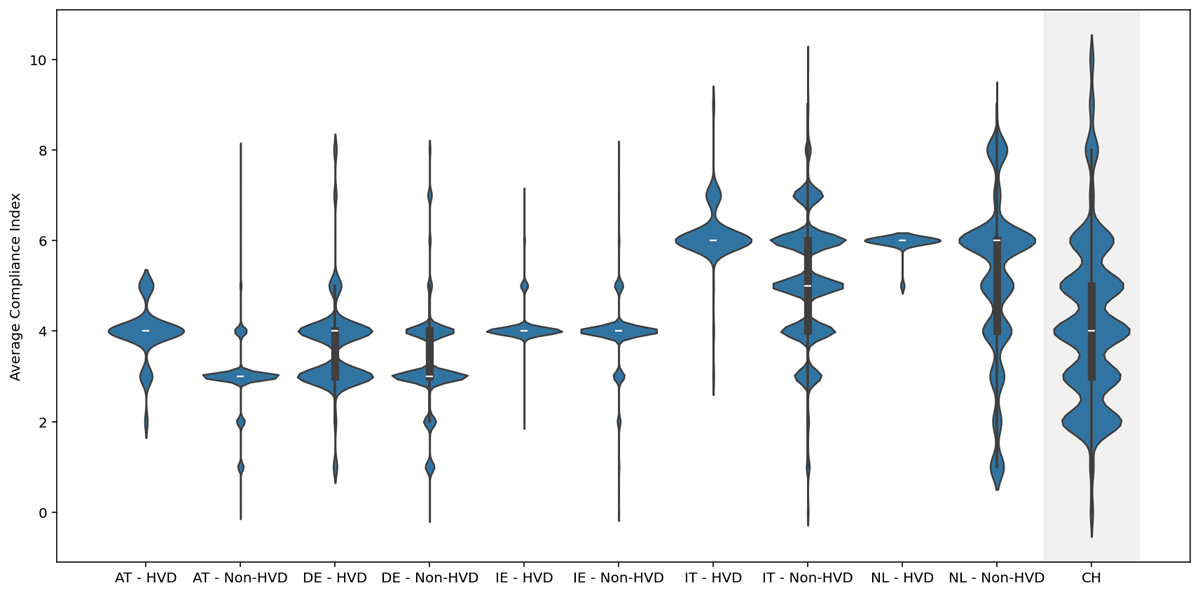

Figure 2 offers a more thorough illustration of the distributions of the compliance index levels per country and per dataset type. The white line indicates the median score and is included within a box plot illustrating the lower and upper quartile scores of each group. The tips of the violins indicate the minimum and maximum scores, and their width illustrates the density of the distribution. Figure 2 hence allows to observe how diversified the landscape of compliance with best publishing practices is across the sample, with countries having very homogenous compliance levels, such as Austria, and others showcasing much more variability, such as Switzerland. Moreover, we can also observe that HVDs tend to have much less dispersed compliance levels than non-HVDs throughout the analysed portals.

Figure 2

Violin plot of the compliance index level per country and per dataset type (HVD and non-HVD).

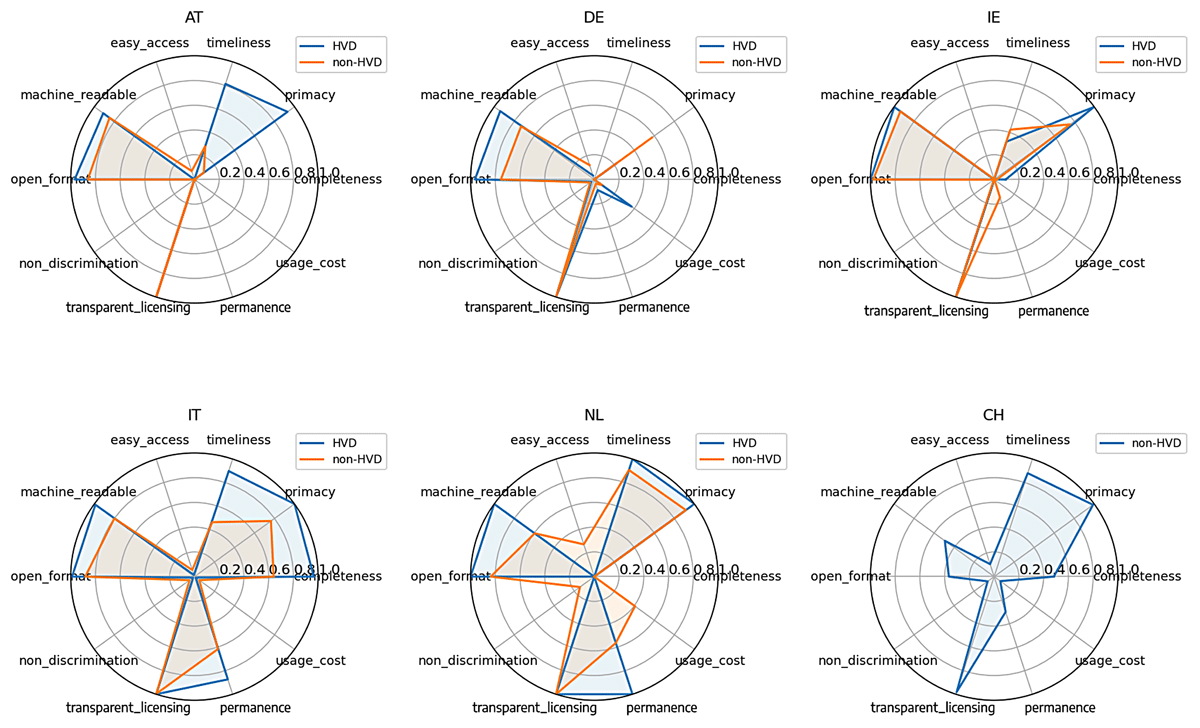

Figure 3 provides further insight into the difference in average OGD best practices compliance levels between countries. We see that several portals are penalised by the mere absence of information, with the completeness criteria recording null values, or nearly, in 4 out of 6 portals in the sample.

Figure 3

Composition of the average compliance index score by quality principle per country and per dataset type (HVD and non-HVD).

Furthermore, this lack of information sometimes implies low scores in other dimensions, as the missing variables are necessary for determining whether the dataset metadata complies with certain data quality principles. The most striking examples are those of the data update frequency never appearing on the German portal, already cited above, and that of the data access link, always missing on the Austrian portal. These cases of systematic unreported information imply the impossibility of attributing a score for certain quality dimensions (timeliness and permanence in this example), in addition to receiving a 0 score for completeness. Moreover, it is notable that the principles showcasing the lowest average scores are all related to license openness: (easy access, non-discrimination, and usage cost). That is mainly because we considered a license to be open when no form of condition is requested for any kind of reuse (that is for example the case when a dataset is licensed as public domain), whereas the dominant model across the portals is that of allowing for any kind of reuse while requesting attribution to the data producer, employing license akin to CC BY.2 In addition to the widespread limited license openness, a common observation across all EU portals is the high scores for transparent licensing, machine readability, and open format. Lastly, despite these common patterns, we can observe that many portal-specificities subsist, with the different portals recording vastly varying scores on different dimensions. In this regard, the Netherlands offers an example with its unusually high permanence score, especially among HVDs, and so does Irish unusually low timeliness, with only Germany scoring lower due to lack of information.

Table 3 provides an overview of the distribution of dataset issuers across the different portals and by dataset priority level. In all portals, HVDs are published by a lower number of organisations compared to non-HVDs. Combining these insights with the standard deviations in Figure 1, we observe that in most cases, within a given portal, the dataset type recording the lowest variety of issuers is associated with a more homogeneous compliance level. The most striking example is that of the Dutch portal, in which all HVDs are published by the same issuer, and for which the compliance index standard deviation of 0.21, against 1.82 for non-HVDs.

Table 3

Measures of issuers’ distribution concentration per country and per dataset type (HVD and non-HVD).

| COUNTRY | DATASET TYPE | NUMBER OF ISSUERS | TOP ISSUER SHARE (%) | TOP 3 ISSUERS SHARE (%) | ENTROPY SCORE OF ISSUERS’ DISTRIBUTION |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT | HVD | 16 | 18.7 | 48.9 | 3.39 |

| AT | Non-HVD | 146 | 78.2 | 90.5 | 1.44 |

| DE | HVD | 188 | 6.5 | 15.2 | 6.04 |

| DE | Non-HVD | 1658 | 12.1 | 29.2 | 6.43 |

| IE | HVD | 16 | 92.5 | 98.3 | 0.55 |

| IE | Non-HVD | 120 | 58.4 | 70.2 | 2.94 |

| IT | HVD | 3 | 72.8 | 100.0 | 1.07 |

| IT | Non-HVD | 230 | 16.6 | 39.5 | 4.49 |

| NL | HVD | 1 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 |

| NL | Non-HVD | 24 | 37.7 | 74.3 | 2.65 |

| CH | Non-HVD | 128 | 22.6 | 32.7 | 4.94 |

[i] Note: The Entropy Score is calculated using Shannon entropy in bits. It is a measure of dispersion, with higher values designating a more dispersed distribution.

Generally, the measures of the dispersion of the issuers’ distribution from Table 3, in conjunction with the compliance index standard deviations from Figure 1, highlight the fact that more dispersed issuer distributions are associated with more variability in the compliance index distribution. This might be an implication from the fact that as the HVD strategy places more emphasis on a subset of datasets, a subset of publishers will publish more datasets relatively to the non-HVD issuers. This, in turn, can lead to overall more homogenous compliance levels within an OGD portal.

Discussion and Conclusion

An analysis of the metadata from 318,696 datasets across six European countries revealed a consistently low and uniform level of adherence to best practices for Open Government Data publication among the national OGD portals in our sample. Overall, HVDs display an average higher compliance level than non-HVDs in all the EU national portals analysed. Furthermore, we observe that the Swiss portal records an average publishing best practices compliance index in line with the other portals, even considering only HVDs, despite not resorting to any data prioritisation strategy.

The composition of this index differs significantly from portal to portal, reflecting differences in the level of maturity between the OGD initiatives of the different countries within the sample, which has been shown to be linked to a myriad of different factors. Among these, economic factors, such as GDP and national expenditure, as well as the level of e-government development are often mentioned (de Juana-Espinosa & Luján-Mora, 2019; Wen & Hwang, 2019). Widespread technical ability and culture favourable to the development of OGD are also found to play an important role, and need to be fostered through investment in training and data literacy (Gomes & Soares, 2014; Haini et al., 2020). Moreover, choices related to infrastructure are also relevant, since they allow for information centrality and findability (Lnenicka et al., 2024). Even within a country, differences in OGD publishing practices and instructions can persist. Indeed, the agencies running the OGD portals often publish guidelines for public administrations to follow when posting their datasets,3 which inevitably reflect differences in the way each country designs and implements its OGD strategy. Furthermore, research efforts showed that even within a country, different publishing agencies do not follow the guidelines in the same way causing differences in the data quality in datasets posted by different agencies (Marmier & Mettler, 2020; Quarati, 2023; Šlibar & Mu, 2022). However, the purpose of our comparative analysis is not to explain differences, but to observe common patterns. For example, most data portals recorded their best scores in the dimensions concerning transparent licensing, machine readability, and openness, while scoring poorly on dimensions such as timeliness and permanence. This might suggest that public administrations more easily comply with quality principles that require one-time dataset specifications upon publication but face greater challenges with principles that demand ongoing actions to sustain data quality over time.

Our analysis highlights two possible implications of the use of the HVD strategy. First, the fact of recognising a subset of datasets as having more value than others might discourage non-HVD publishers from applying the same level of scrutiny when publishing OGD, hence creating a disparity in the level of publishing best practices compliance within a portal, which was observed in all HVD strategy-using portals of our sample. Second, this prioritisation naturally implies increasing the proportion of data published by a more restricted group of issuers. This indicates that the overall portal data quality will be more dependent on the training and publishing practices of fewer individuals, possibly preventing average data quality levels from being balanced within a portal, thanks to publisher diversity. We are hinted towards the existence of this kind of effect by the fact that, throughout the sample, HVDs generally display more “extreme” scores (either close to 0 or to 10) in different quality dimensions than non-HVDs.

Another relevant aspect to the issue is that adopting the HVD strategy does not cancel out or compensate for certain weaknesses that OGD publishers can have. Indeed, various portals within our sample simply never contained certain types of information and mostly resorted to not entirely open reuse licenses, facts that hold for HVDs as well as other datasets. Barry and Bannister (2014, p. 146) find that the lack of open licensing is linked to concerns over liability of the publisher organisation about the way OGD could be used after being published, a concern “reflect[ing] conservative and defensive historical attitudes to government data”. Compliance with this and other quality principles requiring one-time action upon publication, opposed to continued maintenance ensuring timeliness for instance, depends on governance decisions rather than operational modalities. They are hence less likely to benefit from HVD strategy adoption, as the main benefit of dataset prioritisation lies in dedicating more resources to datasets identified as high value, but does not necessarily imply different standards in terms of format, licensing or information completeness. This is pointed out by the fact that the difference in compliance levels between HVDs and non-HVDs tends to be larger for quality principles involving continuous effort, such as permanence and timeliness, than those that do not, such as usage_cost and open_format.

Moreover, establishing a hierarchy of potential economic value among OGD fosters the idea that the main objective of OGD is economic development, relegating to the background claims of improving government transparency and democratic involvement, values that the OGD movement was initially founded on (Alexopoulos et al., 2023; Zuiderwijk et al., 2018); even though signs of such a transition have been observed for years already (Mettler & Miscione, 2023). Lastly, the idea of prioritising data also goes against the OGD ideal of granting the public the choice to select the datasets relevant to their intended use themselves, a similar logic fuelling the “open by default” idea, currently the recipient of tangible efforts throughout Europe (Government of Ireland, 2025).

All in all, we have seen that despite the HVD strategy appearing to present potential in improving the level of compliance with best practices in publishing for at least some datasets, it is far from being a panacea for all causes of low OGD quality. Indeed, the most frequently overlooked data quality principles are those regarding open licensing, a problem common to countries using the HVD strategy and Switzerland. However, Switzerland’s profile has the particularity of performing less well in areas that seem to work relatively well for other countries, namely machine readability and format openness, while doing better in timeliness, which appears to cause more problems in other portals. This factor, combined with the fact that the set of OGD publishers is rather concentrated (as shown by Table 3), suggests that the overall portal data quality could be increased with better compliance with “one-off” publishing best practices by a relatively small number of organisations. In this regard, the HVD strategy seems to perform rather well in other European countries, as it might be easier to train a smaller number of publishers in best practices than their entirety. However, as is observable in different EU countries’ portals, adoption of the HVD strategy is not an answer to certain governance questions heavily affecting the degree of compliance with best publishing practices, notably license openness. Lastly, one cannot forgo the risks associated with HVDs, particularly that of non-HVD issuers being less rigorous when publishing, which could be even more relevant for a country where three publishers account for roughly a third of datasets.

Our study is not without limitations, the main one being that the HVD strategy is still in its early stages of implementation in many of the OGD portals that make up the sample, with several of them containing only a small share of HVDs. While we believe that collecting early evidence does have the merit of contributing to the establishment of an empirical base regarding HVD strategy implementation, repeated evidence collection efforts in the future will be necessary to fully understand the relationship between data quality and HVD use. Second, our reliance on the OGD publisher compliance index implies inheriting its limitations, and notably the fact that it rests on 10 principles defined by the Sunlight Foundation, which is only one among competing OGD best practices systems.

We hope this initial assessment will be complemented by future research, both in terms of implementation stages and in terms of approaches. Indeed, choosing alternative approaches to measuring or approximating OGD quality can contribute to building a more complete and nuanced view of the phenomenon.

Data Accessibility Statement

The data used for this article is freely available on the open government data portals listed in the methodology section, which also describes the method used for their collection.

Notes

[6] Among others, see for example the Swiss OGD publishing guidelines (https://handbook.opendata.swiss/de/content/glossar/bibliothek/ogd-richtlinien.html) and the Dutch guide to open data (https://data.overheid.nl/en/ondersteuning/data-publiceren/handreiking-open-data).

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Author contributions

Leonardo Mori: Conceptualisation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualisation. Tobias Mettler: Conceptualisation, Supervision, Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.