Introduction

Unaccompanied minor refugees (UMRs) are among the most vulnerable groups within the refugee population (Derluyn et al., 2010). While many UMRs initially express relief upon their arrival, this sense of relief is often undermined over time by daily challenges and the need to cope with various traumas (Colic-Peisker, 2009). This situation can lead to psychological distress, including depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (Jensen et al., 2019) – factors that may contribute to negative social behaviors (Gravelmann, 2017), ultimately threatening their integration (Söhn et al., 2016). In accordance with Article 11 of the Swiss Federal Constitution, which emphasizes the protection of children and young people, socio-educational support for UMRs is crucial for providing stability and emotional security (Bustamante et al., 2022; Peter et al., 2020). Numerous studies highlight the significance of care and security measures for UMRs in addressing these emotional challenges (Andersson et al., 2021; Hodes et al., 2008).

While research has identified various appropriate care and security measures for supporting UMRs (Iglesias et al., 2023; Omland & Andenas, 2020), only recent research has studied the role of the organizational place and space of the centers where refugees are typically accommodated (Bombach, 2023; De La Chaux et al., 2018; Kodeih et al., 2023; Mey et al., 2019). Organizational place and space are concepts from organizational theory that focus on understanding the spatial conditions affecting members’ behavior (Cartel et al., 2022; Dacin et al., 2024). While places address geographic locations with socio-historical significance (Gieryn, 2000), spaces refer to built environments that emerge from organizational activities (Stephenson et al., 2020). Previous literature in organizational theory has shown the relevance of places and spaces on “actors, actions, and outcomes” (Lawrence & Dover, 2015, p. 371). Following this perspective, we can conclude that the spatial conditions of UMR accommodations may influence the social behavior of their inhabitants. This leads to the subsequent research question: Which specific spatial conditions of UMR accommodation centers can promote their inhabitants’ positive or negative social behavior?

By conducting a multiple case study using the Eisenhardt (1989; 2021) method, we compare two UMR accommodations (pseudonyms: Rosa and Stella) located in the same Swiss canton and similar in several aspects (e.g., care and security measures, number of inhabitants, management, and available financial resources) but differing in the observed social behavior of the inhabitants. Through the collection and analysis of various qualitative data from the two accommodations (interviews, observations, and documents), we developed a theoretical model illustrating how i) the environment of the place, ii) the facilities of the space, iii) the expectations of the space, and iv) atmospheric design options can influence the social behavior of UMR residents in specific ways. The comparison reveals that UMR accommodation Rosa features a quieter environment, superior infrastructure for social interactions, and better-aligned expectations of the place, while cramped conditions and limited leisure opportunities characterize Stella.

The established model is both theoretically and practically relevant. It offers additional insights into how UMRs can receive support—beyond care and security measures—in their host country. Our model emphasizes the significance of considering spatial dimensions that influence UMRs’ social behavior, thereby indirectly promoting their well-being. These insights are practically relevant as they broaden the toolkit available to public entities and care workers responsible for the development and well-being of UMRs living in accommodation centers.

Theoretical Background

Social Behavior and Social Behavior of UMRs

Social behavior encompasses a person’s actions that influence others and can provoke reactions, emotions, and subsequent actions (Staub, 2013). It includes how individuals communicate, cooperate, resolve conflicts, internalize norms and values, and establish and maintain relationships (Schmidt-Denter, 2005). Social behavior can be particularly disrupted during adolescence, as Hazen and colleagues (2008, p. 72) described adolescents’ behavior as “remarkably consistent in its lack of predictability.” Adolescents may experiment with certain behaviors, take risks, and test their limits in their pursuit of independence, self-identity, and the establishment of boundaries and limitations (Hazen et al., 2008).

Problematic or “problem behavior” refers to actions deemed undesirable for adolescents by adult society (Haydon et al., 2011). It is further defined as behaviors that can impede adolescents’ successful psychosocial development (Knight, 2009). Studies indicate that adolescent boys show higher rates of risk behaviors, while girls encounter more significant emotional challenges (Bor et al., 2014; Patel et al., 2007). Research has also shown that adolescents’ family background and socioeconomic status significantly impact their behavior (Hartas & Kuscuoglu, 2020).

On one hand, the social behavior of UMRs is expected to follow a pattern similar to that of other adolescents, as most are in their teenage years. On the other hand, their unique circumstances can introduce additional influencing factors that must be taken into account. For example, UMRs’ distinct cultural backgrounds can shape their social behavior (Yearwood & Meadows-Oliver, 2021). Since UMRs come from diverse cultural contexts, this influences their communication styles, social norms, and expectations of relationships, which may differ from the host country’s practices (Triandis, 1995). As they navigate a new cultural landscape, UMRs may experience cultural dissonance, leading to confusion or conflict in their social interactions (Berry, 1997). Additionally, uncertainties regarding UMRs’ residency status while trying to integrate into a new society can significantly impact their mental well-being and, consequently, their social behavior (Lems, 2019). Finally, the potentially traumatic experiences of the escape can affect UMRs’ psychosocial development and related social outcomes (Hartmann et al., 2024).

Care and Security Measures for UMRs

Specific care measures must be put in place, considering the various conditions that may increase the likelihood of UMRs displaying problematic behavior. Hammoud (2024) emphasizes the significance of UMRs feeling welcomed as a crucial factor in positively influencing their social integration. A study by Andersson et al. (2021) indicates that UMRs should experience a so-called ‘turning point’ in their development: an enhanced sense of security and independence, belonging, and feeling loved and cared for. Similarly, Bitzi and Landolt (2017) highlight the importance of ‘feelings of belonging’ in UMRs’ social development and emphasize the specific role of UMRs’ educational experiences.

The Swiss Federal Council’s “Strategy for a Swiss Child and Youth Policy” outlines several care measures that should be enacted to comply with international conventions on children’s rights and positively influence the social behavior of UMRs (Peter et al., 2020). Research has also examined the role of security staff and best practices that can encourage responsible security management (Bustamante et al., 2022). Care and security personnel should cultivate an environment that provides a sense of stability and emotional security for UMRs. The development of social skills and the willingness to complete tasks independently should also be encouraged, along with UMRs’ participation in social life. These care measures can significantly enhance UMRs’ social behavior when implemented correctly.

Organizational Place and Space

While most literature has focused on the preconditions that shape UMRs’ social behavior (Derluyn et al., 2010; Huemer et al., 2009) and care measures to mitigate challenging behavior (Iglesias et al., 2023; Omland & Andenas, 2020), to our knowledge, only a few studies have examined the relevance of potentially influential spatial dimensions. Insights from organization studies research, however, indicate the critical role of spatial factors in people’s behavior (Cartel et al., 2022; Dacin et al., 2024). Existing research has shown that both place – defined as a geographic location with socio-historical significance (Gieryn, 2000) – and space – defined as a built environment emerging from organizational activities (Stephenson et al., 2020) – can influence how people interact with one another.

For instance, Lawrence and Dover (2015) examined how places and spaces can transform institutions—norms and habits—in the context of social housing programs. Wright and colleagues (2021) revealed the role of places and spaces in fostering a sense of social inclusion during times of crisis. Further research has explored how spaces can shape individuals’ identification with an organization (Liu & Grey, 2018; de Vaujany & Vaast, 2014) and the potential for jointly envisioning a place’s future (Fohim et al., 2024). The sense of place can also affect individuals’ willingness to engage in sustainable development practices (Yu, 2024). Lastly, organizational places and spaces can influence individuals’ well-being (Colenberg et al., 2021; Leone, 2023; Oyedeji et al., 2025) and their emotions (Beyes & Steyaert, 2011; Kuismin, 2022), thereby further impacting their behavior.

Research Question

Given the critical role of place and space in shaping people’s behavior, a growing number of studies have examined refugee camps through this theoretical lens (e.g., De La Chaux et al., 2018; Kodeih et al., 2023; Waardenburg et al., 2019). They have explored how respected spaces contribute to maintaining social stability (De La Chaux et al., 2018), how sheltering work can somewhat alleviate refugees’ experience of indefinite temporariness (Kodeih et al., 2023), and how reception centers for refugees can be viewed as liminal spaces where individuals face a pervasive sense of boredom (Waardenburg et al., 2019). In the Swiss context, certain studies have investigated the spatial conditions of UMRs’ accommodation centers and concluded that most placements do not offer adequate conditions to ensure children’s welfare (e.g., Bombach, 2023; Mey et al., 2019). Therefore, Mey and colleagues (2020) characterize these accommodation centers as “vacuums,” as the primary purpose of these spaces is to provide an efficient asylum process while overlooking the needs of UMRs.

Recognizing that many UMR accommodation centers lack suitable environments and understanding the impact of places and spaces on people’s behavior, it is crucial to analyze how the spatial conditions for UMRs can influence their social behavior, both positively and negatively. Identifying these conditions is also relevant to the well-being of UMRs and the broader public interest. With a better understanding of these spatial conditions, responsible public entities can choose and design UMR accommodation centers more effectively to prevent or mitigate problematic behavior, thereby conserving personal resources and energy. Thus, this study aims to determine the spatial characteristics of UMR accommodation centers that can foster either positive or negative social behavior among their residents.

Methods

To address this research question, we apply a multiple case study approach, as suggested by Eisenhardt (1989). The multiple case study, also referred to as the Eisenhardt method (Eisenhardt, 2021), is particularly well-suited for our purposes. This approach allows for the investigation of new topics, especially when examining societal grand challenges (Eisenhardt et al., 2016), which applies to our research topic. Moreover, as the theoretical background section has revealed, the theoretical linkages under investigation are relatively underdeveloped, making the multiple case study approach widely recognized as a valuable method (Gehman et al., 2018). As elaborated, we aim to understand the spatial conditions of accommodation centers that can explain the differing outcomes related to UMRs’ social behavior. Following Eisenhardt’s (1989) approach, we compare two similar accommodation centers that differ concerning the variable of interest: the observed social behavior of UMRs.

Research Context

For our investigation, we selected two UMR accommodation centers, which we designated with the pseudonyms Rosa and Stella to maintain the anonymity of the participants. Both centers are situated in the same Swiss canton. By selecting accommodation centers from the same canton, we can ensure a comparable setting as required when applying the Eisenhardt (2021) method. For example, regarding management, both centers are operated by the canton’s UMR support department. In each center, daycare is provided by social educators and caregivers. The social education teams in both centers adhere to the same philosophy of care. This is emphasized by the central idea that no one can be compelled to do something, even if the care team believes it is the right course of action. This philosophy of care is intended to assist caregivers in strengthening their presence and acting as effective and respected authorities.

The conditions regarding security measures are also comparable. The same external security service company oversees the night shift at both centers. The security staff is responsible for keeping the UMRs safe at night and ensuring everyone is home. Some employees from the company work at both residences, which is why UMRs can be expected to receive equal treatment in both centers. Additionally, the canton provides a night service that supports both facilities in case of emergencies. Since Rosa and Stella are both under the jurisdiction of the same cantonal authority, both centers also have equal access to financial resources. Furthermore, in terms of the number of residents, both centers are comparable: approximately 70 UMRs live at Rosa, while about 50 reside at Stella.

Although many conditions are similar, initial discussions with the night shift staff who work in both accommodations revealed that the social behaviors of UMRs differ between the two locations. One night shift employee who has worked in both centers noted, “I have seen differences as I have already worked in various UMRs accommodations as a security guard” (Night shift employee). This observed difference can be confirmed through an analysis of selected indicators from the night shift reports provided by the company (see Table 1). The analysis of the night shift reports for 2023 shows clear differences in the social behavior of UMRs living at Rosa and Stella. At Stella, the night shift had to intervene six times due to UMRs’ aggressive behavior, while only one such incident was recorded at Rosa. Additionally, five disputes among the UMRs were documented at Stella, whereas no such incidents were reported at Rosa. The night shift also had to intervene twice at Stella due to disturbances affecting sleeping hours, compared to only once at Rosa.

Table 1

Analysis of the Night Shift Reports 2023 of UMR Accommodations Rosa and Stella.

| TYPE OF INCIDENT | UMR ACCOMMODATION ROSA | UMR ACCOMMODATION STELLA |

|---|---|---|

| Aggressive behavior by UMRs | 1 | 6 |

| Confrontations among UMRs | 0 | 5 |

| Disturbance of night’s rest | 1 | 2 |

Further investigations through additional interviews and observations confirmed a distinct prevailing basic mood between the two centers. The overall atmosphere and prevailing climate, shaped by the behavior and interactions between UMRs and employees, were generally described as more positive at Rosa than at Stella. Thus, alongside various comparable conditions regarding care and security measures, as well as the number of inhabitants, management, and financial resources in the two accommodation centers, the initial investigation phase revealed a difference in UMRs’ social behavior. UMRs at Rosa were often perceived as quieter. Therefore, comparing these two cases, Rosa and Stella, provides a suitable research context for investigating the spatial conditions as potential influencing factors on the observed distinctive social behavior.

Data Collection

In line with the applied Eisenhardt (1989; 2021) method, we collected various qualitative data to triangulate potential findings. We gathered data from four different sources to comprehensively understand the research context. We conducted observations and interviews, along with collecting relevant documents and photographs/maps. In total, we conducted five interviews. One interview was with the head of the accommodation center, Rosa, and another with the head of Stella. Additionally, we interviewed one employee responsible for the night shifts. This interviewee had worked in both accommodations, allowing them to compare and provide information on both locations. Finally, we undertook one group interview with the inhabitants of Rosa and one with those at Stella. The UMRs who participated in these group interviews were selected by the employees present during the investigation. The criterion for shortlisting UMRs was their sufficient level of German and their ability to express their points of view independently. Each UMR voluntarily participated in the group interviews and was not coerced into doing so.

In addition to the interviews, we collected various documents from the respective canton, particularly those related to the care concept for working with UMRs and the existing night shift reports from 2023, as mentioned earlier. Furthermore, we spent an afternoon and evening at each accommodation to observe and identify differences in the spatial conditions among the centers. Impressions were documented through field notes and photographs. Photos were taken with the management’s approval, and UMRs were only photographed with their consent. Additionally, private areas, such as bedrooms, were also photographed only with the consent of the UMRs. Finally, we gathered map extracts of the locations and surroundings of the accommodation centers for further analysis.

This unique data set enabled a comprehensive disclosure of the spatial differences and their potential effects on the social behavior of UMRs at the two accommodation centers. Data collection took place between January and April 2024. Table 2 presents an overview of the gathered qualitative data.

Table 2

Overview of Data.

| TYPE OF DATA | UMR ACCOMMODATION ROSA | UMR ACCOMMODATION STELLA | TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interviews | 1 with accommodation leader (1 h) | 1 with accommodation leader (1 h 10 min) | 2 h 30 min |

| 1 with employee of the night shift company (20 min) | |||

| Group Interviews | 1 with selected inhabitants (40 min) | 1 with selected inhabitants (30 min) | 1h 10 min |

| Observations | 1 afternoon/evening (6h 30 min) | 1 afternoon/evening (5 h) | 11 h 30 min |

| Photos | 136 photos | 120 photos | 261 |

| Maps | 2 maps covering the accommodation and surroundings | 2 maps covering the accommodation and surroundings | 5 |

| 1 map covering the entire canton | |||

| Documents | 14 night shift reports | 15 night shift reports | 31 |

| 1 document about the applied philosophy of care 1 care concept to work with UMRs | |||

Data Analysis

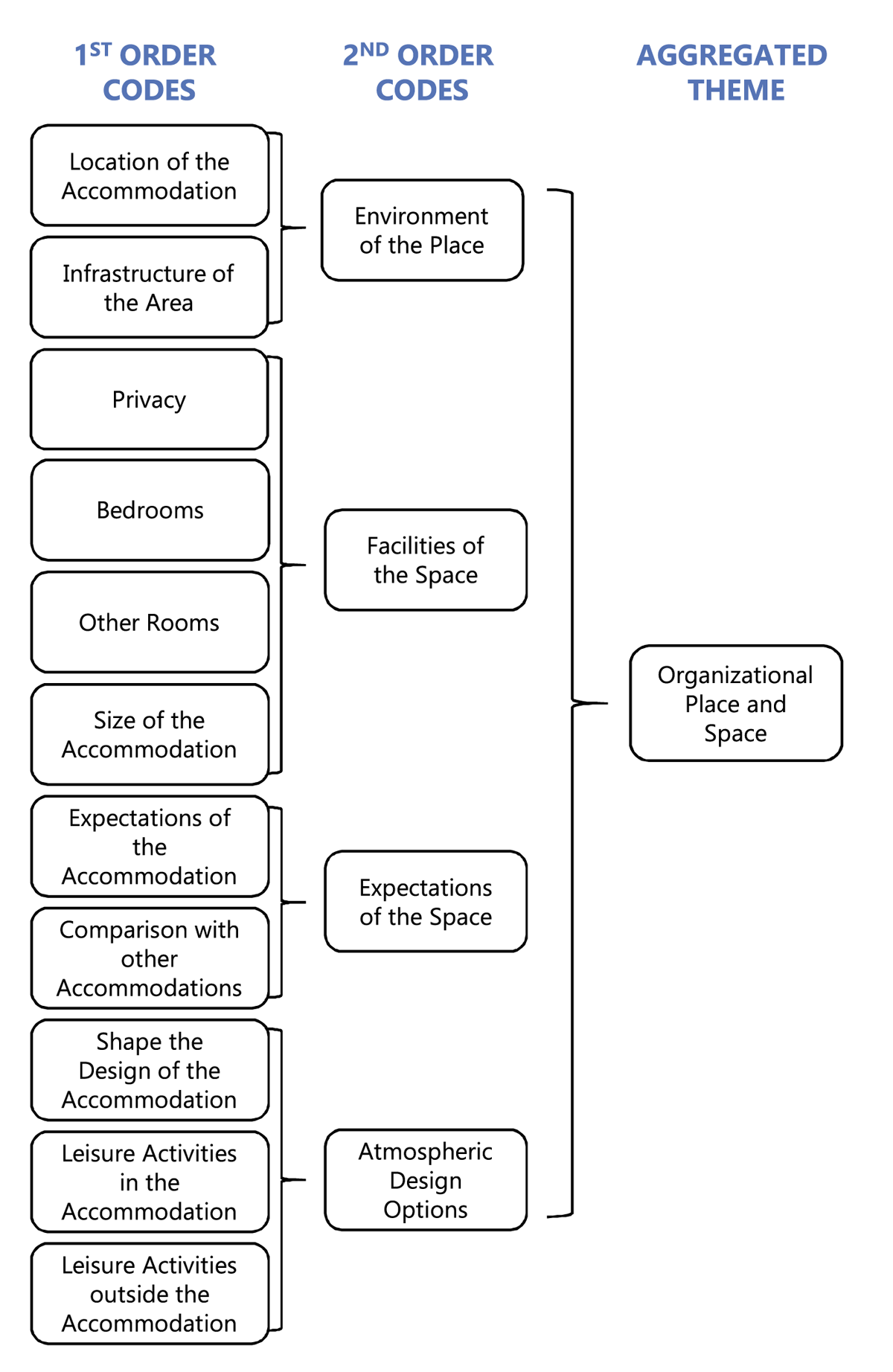

Following the Eisenhardt (1989; 2021) method and established procedures for developing insights from qualitative data (see Miles et al., 2014), we analyzed the transcribed interviews, field notes, and documents using the open-source coding program “Taguette.” Through an iterative process, we marked any central passages with a keyword, resulting in a relevant first-order code. Photos, as well as map extracts and aerial photographs of the two accommodations and their surroundings, supported the analysis. Based on the established first-order codes, we then developed subsequent second-order codes: i) environment of the place, ii) facilities of the space, iii) expectations of the space, and iv) atmospheric design options. These second-order codes were then summarized to form the aggregated theme ‘Organizational Place and Space’ (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Data Structure.

Building on the established first-order codes, we analyzed the spatial characteristics of each accommodation to address the initial research question: What specific spatial conditions of UMRs’ accommodation centers can promote positive or negative social behavior among their inhabitants? Table 3 presents selected data extracts to enhance the transparency of this process. In the next section, we will provide additional details about the findings derived from this analysis.

Table 3

Second-Order, First-Order Constructs, and Data Exemplars.

| 2nd ORDER CODES | 1st ORDER CODES | UMR ACCOMMODATION ROSA | UMR ACCOMMODATION STELLA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environment of the Place | Location of the Accommodation | Close to nature: “Yes, the remote location of the accommodation helps to clear the head…” [leader] “There are advantages because we are not in a hotspot like an urban center, … and therefore the risk of something going wrong is smaller.” [leader] “I think Rosa is a quiet place…” [UMR] | Close to an urban center: “The location makes a difference for the boys. In the nearby urban center, you are much closer to the problems. Especially on Friday nights when you go out.” [leader] “They are close to the city. And yes, they see a lot of things in the city… ” [Night shift worker] “Accommodation is right next to the main road.” [field notice] |

| Infrastructure of the Area | Good access opportunities to sport and other infrastructures: “There are sports fields here in the village and I am currently in talks with the municipality about whether we can get a hall here. There is also a swimming pool…” [leader] | Diminished access to sport and other infrastructures: “In the village here is only the youth club… We can‘t go to the gym because the clubs have booked them all the times.” [leader] “The fields here are always occupied and we can‘t use them.” [leader] | |

| Facilities of the Space | Privacy | Privacy granted in the bedroom and in the nearbynature: “My favorite place here is the nature. I go running outside every morning.” [UMR] “On the floor where I live, there is an office. I like to play the keyboard there.” [UMR] “I am often outside and in the evening, I come home and need peace and quiet. That’s why I like to be in my room.” [UMR] | Privacy only granted in the bedroom: “Are there any opportunities for privacy in the accommodation? A place where you can be alone? In your room. We don‘t have any other options.” [leader] “Unfortunately, we don‘t have any other spaces for privacy. We would like that.” [leader] |

| Bedrooms | UMRs sleep in the bedroom that they share with anotherperson: “For me everything is great. The room is also good, I am only in the room with one other person.” [UMR] | UMRs sleep in the bedroom that they share with another person: “The boys know that double rooms are a luxury.” [leader] “We have a room with four young people, but there are never any problems with them. When there are two people, there are problems from time to time.” [leader] | |

| Other Rooms | Kitchens withdining rooms/group rooms and a fitness room in thebasement: “We have the kitchen that we can also use for social activities.” [leader] “The UMA have set up a fitness room themselves with donations.” [field notes] | No (inviting) spaces for social activities, eating or sports. Too few bathrooms: “We can‘t do much here.” [leader] “There are rooms to live here, but it‘s difficult to work with UMRs. The accommodation is not suitable for UMRs.” [leader] “They need… space where they can let off steam and let out their anger…” [leader] “No fitness room is possible in the basement because there are no basement windows” [field notice] | |

| Size of the Accommodation | 70 UMRs live in the accommodation, divided into six shared apartments and spacious residential containers inthe courtyard: “We have currently around 70 UMRs, coming from different places.” [leader] | There are 50 UMRs living in the accommodation. The house is too small for so many people: “There are 50 or 60 people living in this accommodation… so it must be almost dirty because… there is not enough space. We would like 20 people… to change accommodation so that it is quieter and cleaner here.” [leader] “The accommodation is too small for so many people, we need more space. I want more space.” [UMR] | |

| Expectations of the Space | Expectations of the Accommodation | Expectations decrease after the adjustment period: “At the beginning they have ideas that they will be paid something… But within a short time the boys come down to earth…” [leader] | Generally high financial expectations: “They have huge financial expectations.” [leader] |

| Comparison with other Accommodations | Other accommodations are not perceived as better: “Especially when I compare us with UMRs who live in other cantons. I think we have made more progress here than others.” [UMR] | Continuous comparison with other accommodations: “They only see the advantages of the other cantons and perhaps not what is going better here.” [leader] “The UMRs also ask around and find out what it is like in the other cantons. There may be more or something different or larger spaces. Accordingly, they come to us and would like to have that too. But they know that there is not much that can be changed here and that it is set in stone.” [leader] | |

| Atmospheric Design Options | Shape the Design of the Accommodation | Many liberties: “Theoretically, they can do almost anything they want… Often they want a carpet. Then we send them to the second-hand store. They can put practically anything they want on the walls” [leader] | Many liberties: “No, they can do anything. Everyone can realize their potential.” [leader] “If supervisors want to set new rules, we hold a meeting and give our opinion.” [UMR] |

| Leisure Activities in the Accommodation | Diverse: “We do activities whenever possible… someone from sexual health and… workshops on violence prevention.” [leader] “Every Tuesday people from an association come… [UMR] “The UMRs can move around outside unhindered, and you can see… kites flying…” [Field notice] | Sparse: “Leisure activities in the accommodation are missing.” [leader] “There are many things that we need but don‘t get… For example, sports equipment…” [UMR] “The common room is not used a lot. UMR stay in the room or outside the accommodation.” [field notice] | |

| Leisure Activities outside the Accommodation | In the village and nearby nature: “The Swiss Youth Red Cross organizes sports afternoons and we go to a sports hall in every Monday.” [leader] “I am playing in the volleyball club here in the village.” [UMR] | Not provided in the town: “The only thing missing in the village are leisure activities.” [leader] “I like playing cricket but we have to use the sports field in neighbor village for that.” [UMR] “I play football for a nearby town” [UMR] |

Findings

As discussed above, the initial investigation phase revealed that UMRs living in Rosa exhibit more positive signs of social behaviors compared to those living in Stella. Subsequently, we elaborate on the important spatial factors to explain the observed differences.

As a critical spatial factor, the data analysis revealed the importance of the environment of the place where the accommodation is located. A notable difference between the two locations emerged in both subcategories. The Stella accommodation is situated on a main road with limited surroundings and noise-sensitive neighbors. It is also near an urban center, which was frequently cited as a significant issue in the interviews. This situation increases the likelihood that UMRs would stay in the city until late, possibly missing their agreed-upon return times. Furthermore, the infrastructure available for UMRs at Stella is limited. The nearby sports field can only be used when a caretaker is on-site, and the sports halls are often occupied by local clubs. As a result, the youth center stands as the only place UMRs can visit without restrictions. In contrast, Rosa is located further from the urban center. Therefore, UMRs must return relatively early when they visit the town, as they would otherwise lose access to public transportation. Additionally, the accommodation in Rosa is near an industrial estate, bordered by pastureland and a forest. Consequently, no neighbors are likely to be disturbed by any noise from the UMRs. Moreover, UMRs can freely use the community’s sports fields, and the community swimming pool is also accessible to them during the summer. Finally, discussions are ongoing to consider whether UMRs can access the nearby sports halls.

The second spatial factor revealed by the data analysis is the role of the facilities of the space. This aspect includes spatial dimensions such as privacy, bedrooms, other rooms, and the size of the accommodations. It is important to note that there is little privacy in any of the accommodations. The only area that provides some privacy is the bedroom; however, all UMRs must share it with at least one other person. In Rosa, some UMRs go into the nearby nature to seek peace and privacy if needed. For this reason, most UMRs at Rosa were generally satisfied with their rooms. In contrast, the conditions at Stella are more cramped. There is no space for any social activities in the accommodation, aside from an uninviting lounge in the entrance area, which others can see into from the street. There is also no dining room, so the UMRs must eat in their bedrooms. Additionally, there are too few bathrooms on each floor. In comparison, at Rosa, dining rooms exist next to the kitchens, which can also be used as group rooms for social activities. In the basement, a fitness room is set up with local donations’ help. A similar room is absent at Stella. Clearly, the Stella accommodation is too small for 50 UMRs and not very suitable for its purpose. Although accommodation Rosa houses more inhabitants (namely, 70 UMRs), it is much better designed for this number of people.

Another spatial factor revealed by the data analysis is the UMRs’ expectations of the space. This aspect encompasses UMRs’ expectations of the accommodation and comparisons with other accomodations. The analysis indicates that when young people arrive at an accommodation, they generally hold high expectations for financial support from the canton, which they associate with the accommodation itself. While these expectations at Stella remain elevated throughout their stay, at Rosa, in contrast, UMRs’ expectations become more realistic after a certain adjustment period, as mentioned by the respective head. Additionally, the analysis revealed that at Stella, residents actively made inter-cantonal comparisons regarding the services and offerings provided by the respective accommodations for UMRs. Their primary focus was on emphasizing the better conditions found in other accommodation centers. This mode of comparison was not observed among the UMRs living at Rosa.

The last significant spatial factor revealed by the data analysis is the potential for atmospheric design options. This factor can be divided into three subcategories. The first involves opportunities for UMRs to shape the design of their accommodations. In both settings, UMRs can design their living spaces as they prefer. There are no notable differences to mention here. The second subcategory pertains to possibilities for engaging in leisure activities within the accommodations. While Stella does not provide specific leisure activities, Rosa offers weekly activities and workshops. Additionally, UMRs at Rosa can enjoy activities in the surrounding garden, which is not available at Stella. The final subcategory concerns available leisure activities outside the accommodations. In the village where Stella is located, there are no opportunities for UMRs to pursue leisure activities, as previously mentioned. For instance, if they want to play cricket, they must travel to another village. In contrast, UMRs at Rosa can join various sports clubs in the village. They can also take part in a communal sports afternoon once a week. In summary, there are clear differences between the two accommodations regarding the subcategories of leisure activities both inside and outside the living spaces. Consequently, UMRs at Rosa have better opportunities to foster an atmosphere that suits them.

The Role of Organizational Place and Space on the Social Behavior of UMRs

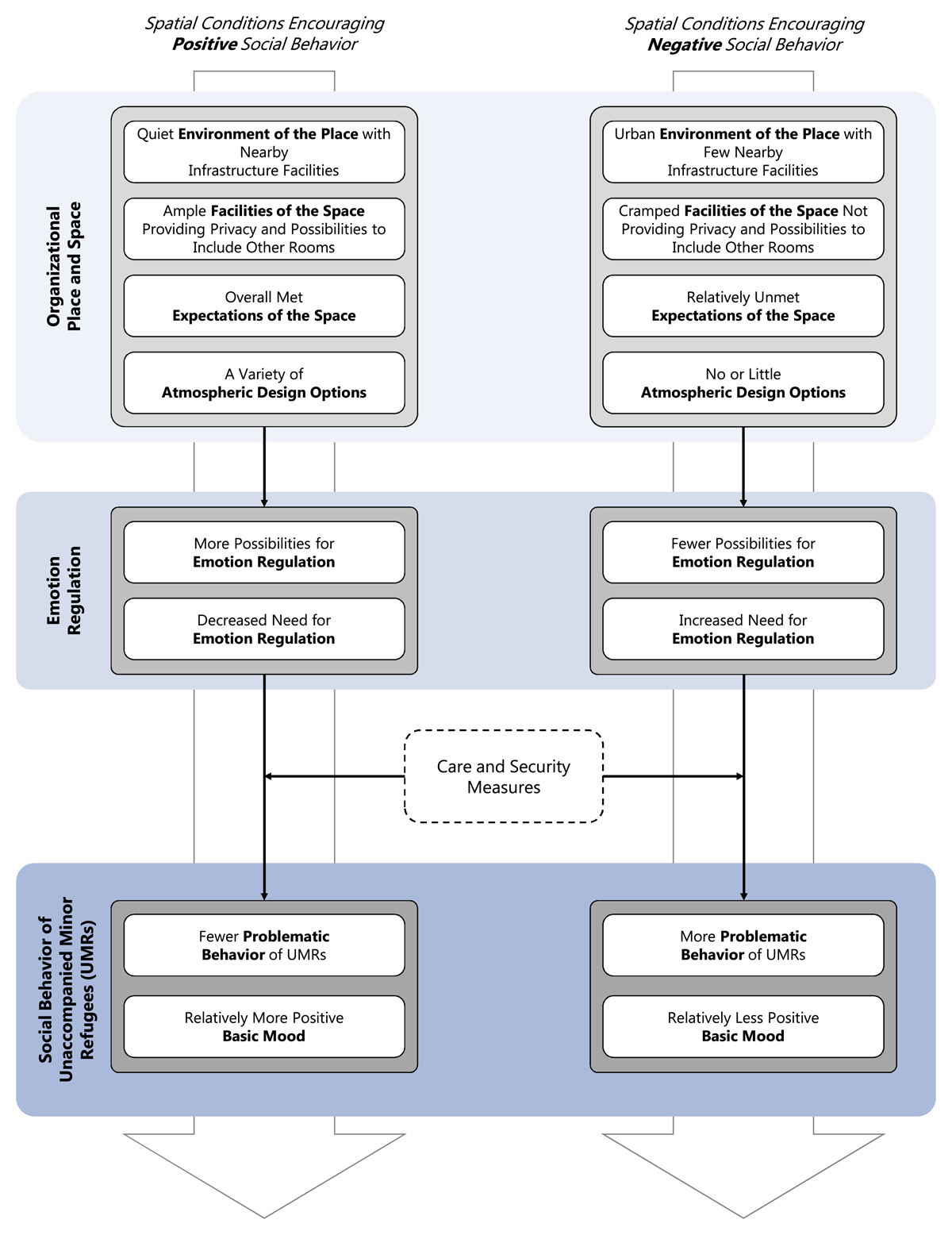

Based on the findings discussed in the previous section, we established a theoretical model aimed at determining the spatial conditions of UMRs’ accommodation centers that can encourage positive or negative social behavior among their inhabitants. Figure 2 illustrates the factors related to the place and space of accommodation centers that, according to our findings, can influence the social behavior of UMRs. We propose that an accommodation center’s arrangement of the environment of the place, facilities of the space, expectations of the space, and atmospheric design options can impact the social behavior of the UMRs living there.

Figure 2

The Role of Organizational Place and Space on the Social Behavior of Unaccompanied Minor Refugees.

Based on the findings, we conclude that i) a quieter environment where the accommodation center is situated, with nearby infrastructure facilities, ii) ample facilities at the accommodation center that provide privacy and options for additional activities, iii) overall satisfaction with the accommodation center, and iv) a variety of atmospheric design options for UMRs can promote more positive social behaviors among UMRs residing in these accommodations. In contrast, v) an urban environment surrounding the accommodation center with limited nearby infrastructure facilities, vi) cramped facilities at the accommodation center that offer few opportunities for privacy and include spaces for other activities, vii) relatively unmet expectations concerning the accommodation center, and viii) limited atmospheric design options for UMRs are more likely to encourage problematic social behaviors among UMRs living in such accommodations.

The identified relationship between organizational place and space, as well as social behavior, can be better understood through the concept of emotion regulation. Various studies indicate that the ability to regulate one’s emotions positively affects social behavior, especially among adolescents (e.g., Blair et al., 2004; Calkins & Mackler, 2011). Additionally, research has explored how organizational places and spaces can influence people’s emotions (e.g., Beyes & Steyaert, 2011; Kuismin, 2022). The comparative analysis reveals that depending on the spatial conditions of an accommodation, there are varying opportunities for the UMRs to regulate their emotions. At Rosa, for example, the UMRs have more chances to retreat or engage in meaningful activities. Furthermore, it can be inferred that the UMRs at Rosa require less emotion regulation—partly because their expectations of the accommodation are better met, leading to reduced frustration. On the other hand, they enjoy more opportunities to cultivate an atmosphere that positively influences their well-being.

Despite the recognized influence of place and space on the social behavior of UMRs, the significance of care and security measures—as discussed in the theoretical section (e.g., Andersson et al., 2021; Bustamante et al., 2022; Peter et al., 2020)—cannot be overlooked. As noted, the care teams in both shelters share the same philosophy of care, which emphasizes empowering caregivers and acknowledging their authority. Open and transparent collaboration is vital to ensure a consistent approach. The primary objective is to create a stable environment that fosters the young inhabitants’ social, psychological, and intellectual development while preparing them for independent living. Implementing these principles remains essential, as the data analysis has also shown. Stella’s group leader articulated this well: “The boys mirror us. If it is not calm, we must ask ourselves, what are we doing wrong? If they receive the support they need, we have no problems.” This quote underscores that the behavior of UMRs often reflects the quality of care and security measures provided. Consistent and supportive care can help mitigate challenges arising from limited opportunities for emotional regulation, whereas neglect can lead to frustration and escalation. Therefore, care and security measures can moderate the effects of organizational place and space on the social behavior of UMRs.

Thus, optimally equipped accommodations alone are not sufficient to foster positive social behavior among UMRs. The role of care work and responsible security management remains crucial, which is why this element is included in the proposed theoretical model. Nevertheless, the arrangement of specific spatial conditions can reduce the need for care, particularly in regulating emotions.

Discussion and Conclusion

For the present study, we employed a multiple case study (Eisenhardt, 1989; 2021) to determine the spatial conditions of UMR accommodation centers that can influence their inhabitants’ positive or negative social behavior. Two comparable UMR accommodations (Rosa and Stella) situated in the same canton were analyzed to answer this question. While the two accommodations were similar in terms of care and security measures, as well as the number of inhabitants, management, and available financial resources, differing social behaviors among the UMRs were noted. We established a theoretical model based on the qualitative data collected and analyzed from the two accommodations to address the research question. The model illustrates the mechanisms through which the arrangement of spatial conditions in accommodations can impact the residents’ ability and need to regulate emotions, ultimately affecting the social behavior of the UMRs.

Contributions

The theoretical model is relevant both theoretically and practically. Theoretically, it contributes to the literature on the well-being and related social behavior of UMRs (e.g., Andersson et al., 2021; Hebebrand et al., 2016; Jurt & Roulin, 2016; Rieker et al., 2020). This literature discusses appropriate care and security measures so that UMRs can develop as optimally as possible in their country of arrival despite their often challenging circumstances (e.g., Bustamante et al., 2022; Peter et al., 2020). The theoretical insights enhance this literature by illustrating the significance of the spatial conditions of UMR accommodations, which, depending on their design, can also influence the inhabitants’ social behavior and, consequently, their future development.

Furthermore, the theoretical insights contribute to literature that has utilized a spatial lens to investigate refugee camps and similar accommodations (e.g., De La Chaux et al., 2018; Kodeih et al., 2023; Waardenburg et al., 2019). In the Swiss context, several studies have examined the spatial quality of UMR accommodation centers, emphasizing the need to ensure privacy and provide leisure activities (e.g., Bombach, 2023; Mey et al., 2019; 2020). However, unlike our research, these studies often concentrate on whether such accommodations meet the welfare and expectations of adolescents. While this is an important area of research, our study distinguishes itself by highlighting UMRs’ social behavior and the related spatial conditions. Despite the slightly different research focuses, most findings overlap, revealing one main distinction. Mey and colleagues (2019) emphasize the importance of selecting accommodations near urban centers, while our insights suggest the benefits of quieter locations. Focusing on social behavior, quieter areas can be advantageous as they offer better opportunities for UMRs to retreat into nature and avoid potential social conflicts that may arise when going out late in town. In addition to this difference, we also stress, as Mey and colleagues (2019) do, the significance of nearby infrastructure for conducting leisure activities and social interaction with others. Therefore, we do not advocate for locations that are isolated from the rest of society when discussing the benefits of a quiet environment.

Finally, the theoretical insights also hold practical importance, particularly for public entities and caregivers responsible for the well-being and development of UMRs. Besides choosing appropriate care and safety measures, these insights can guide responsible decision-makers when considering spatial measures that impact UMRs’ social behavior. At the political level, these insights can serve as a reference for selecting suitable locations and housing for UMR accommodations. This matter naturally hinges on financial resources and the political willingness to opt for accommodations that may influence the social behavior of their inhabitants.

Limitations and Future Research

Like any study, this one has limitations, primarily due to the limited resources available for conducting this research. Investigating the role of organizational place and space in relation to UMRs’ social behavior is a broad topic. To narrow the scope of the study, we concentrated our research on just two accommodations within a limited timeframe while conducting observations and interviews with selected residents, security staff, and the heads of each accommodation. To enhance and potentially expand the theoretical insights, we suggest broadening the research design by comparing other similar UMR accommodations over a longer period and collecting additional qualitative data that would also incorporate the perspectives of care workers. This expanded approach holds promise for identifying further specific spatial conditions of accommodation centers that can influence UMRs’ positive or negative social behavior.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.