The childhood obesity epidemic continues to be a serious problem. The cost of treating ill health caused by obesity around the world will top $1.2tn every year from 2025 unless more is done to check the rapidly worsening epidemic, according to new expert estimates (WHO, 2021). Globally, the estimated number of children and adolescents (aged 5–19) being overweight and obese was over 340 million in 2016, with over a tenfold increase since 1975 (WHO, 2021). Over the past four decades, the prevalence of childhood obesity has augmented dramatically from only 4% to over 18%, and the rising trend has been presumed to continue past 2030 (WOF, 2019; WHO, 2021). Overweight and obese children are likely to remain obese into adulthood and more likely to develop non-communicable diseases. Improvements in the morbidity of cardiovascular diseases (CVD) in the past two decades have been offset by the persistence of unhealthy lifestyles (e.g., physical inactivity and poor dietary patterns), resulting in increases in overweight, obesity, and CVD risk factors (Liang et al., 2019). Despite reports of the problem leveling off (Gooding et al., 2020), the evidence is clear; too many of our youth remain overweight or obese. The situation is especially alarming in countries such as China, the UK and the US — rates of overweight and obesity in schoolchildren and adolescents have been recorded as over 20% in 2018/19 (Croker et al., 2020; Fan & Zhang, 2020; Yusuf et al., 2020).

Previously, we examined CVD risk factors in 163 adolescents (aged 12.9 ± 0.4 years; 76 girls and 87 boys) from two cross-sectional experimental studies in the UK (Thomas et al., 2010, 2011). Measurements included physical fitness, physical activity levels, diet, adiposity, and blood biochemistry including lipid profiles, fibrinogen, and C-reactive protein. Our study agreed with the findings of others and confirmed the obesity figures recorded nationally that year (Stamatakis et al., 2010). In spite of the fact that we found no significant change (P > 0.05) in adiposity over the five-year period between studies, there were, however, some worrying trends in blood biochemistry and body weight profiles. Excess body weight was identified as a problem with 21.3 percent of boys and 26.0 percent of girls classified as overweight or obese. Despite no significant positive change in adiposity, our data did demonstrate a significant negative trend (P ≤ 0.05) in physical activity, physical fitness, blood lipids, and inflammatory factors over the 5-year period (Thomas et al., 2011). Findings from the study were presented at several influential governmental health boards, health-related conferences, and educational sub-committees. The presentation of the findings raised the public’s concerns on the problem of the childhood pandemic. For example, the UK government launched an extensive plan in 2016, namely “Childhood Obesity: A Plan for Action (COP)”. The COP plan included a wide range of strategies and guidelines to reduce the UK’s rate of childhood obesity within the subsequent 10-year period (Knai et al., 2018). Similarly, in China, the prevention of childhood obesity has also been placed as one of the priorities on the health agenda and relevant guidelines (e.g., “Implementation Plan of Childhood Obesity Prevention”) to promote healthy eating and active lifestyles in children and adolescents have been published (National Bureau of Disease Control and Prevention, 2020).

Notwithstanding the government directives and lifestyle initiatives, the battle against childhood obesity is a difficult one. How we effectively implement the governmental policy and objectively evaluate the outcome of execution is a challenging problem. In other words, strategic initiatives in line with governmental policies need implementation if we are to prevent this pandemic from increasing further and becoming uncontrollable (Abarca-Gómez et al., 2017).

Creating a positive educational environment, which plays an influential role in combating the obesity problem, should be one of the initiatives. School involvement has also been advocated in the aforementioned governmental guidelines, suggesting internal (e.g., health professionals, parents, and educators) and external (e.g., schools, health organizations, regions) collaborations to address childhood obesity. In the UK, schools open for 380 half-day physical education (PE) periods (190 days) in each school year. American schools average 180 days of instruction per year, while for schoolchildren in China and Japan, the average is over 200 days. Because young people spend approximately seven hours per day in school, these physical activity periods are attractive for promoting positive health behaviors and delivery of lifestyle interventions. Potential interventions must include advice on physical activity levels and the latest dietary developments (Baker et al., 2020; Miller et al., 2020). These measures should be implemented in conjunction with curriculum re-development. The curriculum should include specific biological topics providing information and education on body shape management and associated potential health and eating disorder problems. Although aspects of the school curriculum relate to health, this content needs to be more focused and concentrated. Schools should also provide extra-curricular activities that promote healthy lifestyles for both pupils and the public. Schools are at the hub of their communities and this demographic is an excellent environment for the facilitation of health promotion.

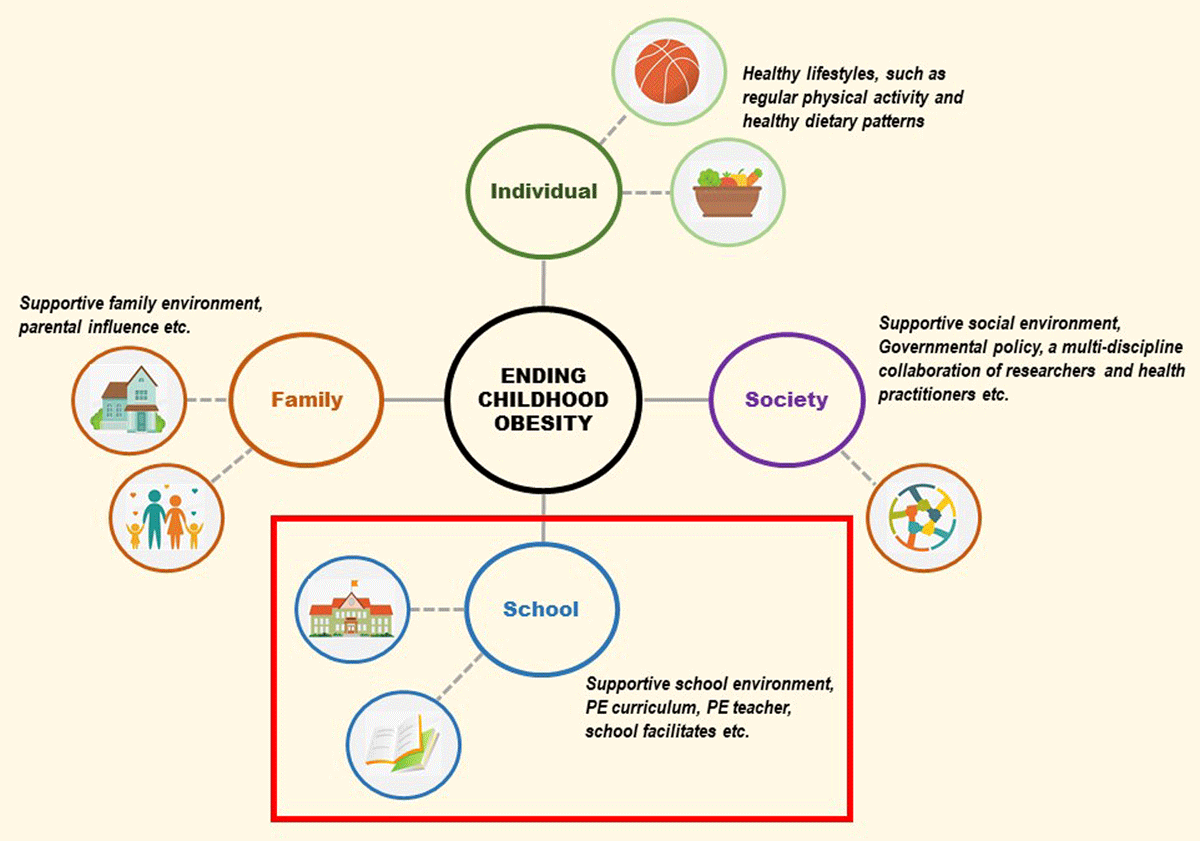

For this initiative to succeed there needs to be support for a whole-school approach where the ethos of the school encourages the application and promotion of well-being for all individuals (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Interrelationships between the school environment, family, health, wellness and obesity.

It has been incumbent upon PE departments to adopt leadership roles in promoting health in the school community. To investigate the success of leadership roles, a recent paper by Nasário et al. (2020) suggested that PE is identifiable with health promotion, and both PE teachers and the PE environment are regarded as legitimate assets for health enhancement. However, the PE teacher’s conceptions, attitudes, and values regarding the role of PE are inseparable from their performance. Further details emerged that the objective of the paper was to verify concepts and attitudes of PE professionals and students, to understand how they value their role in health promotion. From the findings, a total of 942 PE professionals and students (86.9%) regarded themselves as active in health promotion (Nasário et al., 2020). This result emerged although there were no clear definitions or directions about the concepts of health with no curriculum roadmap to develop health promotion objectives. The respondents attributed the responsibility for childhood obesity and lack of motivation to engage in physical activity to external influences. These included the media (72.6%), family (84.7%), and technologies (83.1%). Despite participants regarding themselves as being active in health promotion, there was a lack of clarity on how to promote healthy behavior in schools. There also appeared to be difficulties in providing curriculum development strategies to address the problems associated with childhood obesity and inactivity. A further issue relates to parental conceptions of what constitutes being overweight. Despite positive media campaigns increasing awareness of obesity, parents fail to recognize their children’s weight problems (Etelson et al., 2003). This may also be true for PE teachers. With no formal training or structural policies in place to support developments, our aspirations to tackle the obesity epidemic in schools might be far-fetched and inadequate.

The inability of professional individuals to recognize excess weight may relate to social comparisons where the cut points for perceived overweight rises in line with the increasing waist girths of the local population (Johnson et al., 2008). Furthermore, media messages highlighting overweight and obesity often display images of severely obese people. This can lead to a false sense of security for overweight individuals and those working with overweight children.

These observations may reflect a general shift in PE teachers’ perceptions of what constitutes a ‘normal weight’ child. Early identification and action relating to addressing unwanted weight gain is clearly the best solution. The PE teachers’ enhanced role should include counseling parents early about unhealthy changes in body mass. This should happen in consultation with pediatricians with access to WHO growth curves to monitor and closely evaluate young children who appear to be on upward trajectories in unhealthy growth percentiles. The school remains an attractive setting for combating childhood obesity. However, the PE team is unlikely to take the necessary preventative actions if they have a distorted perception of what constitutes overweight and obesity. Further to this, the problem becomes inflated without effective implementation of governmental support and meaningful intervention. Specific training or assistance may be required to enable the educators to educate and conduct effective preventive activities.

The search for effective interventions to halt this epidemic is urgent. If school-based healthy messages and lifestyle interventions are to succeed, there is a need to develop methodologies to help schools correct their misperceptions of what constitutes overweight and obesity. PE teachers’ expertise and insights need utilization throughout all stages of program planning, implementation, and evaluation. This requires governmental support, curriculum development, and specific educator training and policy reconfiguration.

Due to the ongoing societal problems related to the COVID-19 pandemic, many countries have instituted large-scale and nationwide school closures. The pandemic has led to life-altering challenges for most schoolchildren (e.g., decreased physical activity, increased screen behavior, and unbalanced diet), and has subsequently increased the risk or aggravated the problem of childhood obesity (Arora & Grey, 2020). The pandemic has highlighted the requirement for specific strategies by the government to inform policymakers and education providers to combat these challenges. Some schools in the UK and China applied a mixed-mode approach (online + offline) for PE classes, facilitating new opportunities for addressing student health during the pandemic. However, its effectiveness and generalizability which rely on a series of factors, e.g. technology and cultural context, need to be further investigated. A greater challenge is how schools create favorable environments and update settings to mitigate the residual impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and to combat childhood obesity in the future.

In conclusion, given the existing global childhood obesity problems, which may worsen because of the COVID-19 pandemic, we suggest that now is the time to empower educators and remobilize schools in the post-COVID-19 period. If our governments provide more actual support in synergy with educational providers and policymakers, we may have an opportunity to initiate meaningful changes before the problem becomes uncontrollable.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.