Lay Summary

In the distant past, the Arabian Peninsula repeatedly experienced climate phases with more rainfall during which lakes and grasslands formed. This allowed mobile, prehistoric groups to ‘walk’ landscapes of the interior that now form deserts as we know them. When at other times the rainfall diminished, the settlers had little choice but to give up their residences, leaving behind traces (stone tools, ceramic sherds, fireplaces etc.). They had then to withdraw to more favourable natural places – refugia (‘retreats’) as archaeologists call them.

Naturally catching clouds, providing shade and being slightly cooler, the Al-Hajar Mountain range at the south-eastern corner of the Arabian Peninsula offers natural advantages. This is especially true at places where hollowed, soluble limestone (‘karst’) takes in water during rains like a sponge. Collecting at the bottom of the stone layers, rainfall from a wider area sheds from the rock as a dependable spring or as flow just a few metres under gravels. Due to the solution process at the surface, a bowl-shaped sink – locally called hayl, pl. huyul – can also form. Naturally filling with washed-in sediments and capturing flows during thunderstorms, these sinks act as ‘flowerpots’ in the rocky landscape.

Having found countless prehistoric stone tools at Hayl Ajah at 1000 m a.s.l., we assume that these grass and shrub-covered, flat spaces have attracted elusive mountain animals. This allowed prehistoric hunter-gatherers to hunt or trap them with reduced risk and effort. Herders could take livestock there for grazing. In later times, the silt accumulated in the karst sinks (huyul) was transferred to oases – ingenious man-made ‘biospheres’ that allowed large populations to thrive on the spot, even as the surroundings became completely dry.

Until recently it was not clear how the deep sediment had formed up in the mountains. Via mineral and micropalaeontological analyses, Project SIPO (Masaryk University, Brno) has found out that the sediment which filled huyul at elevations of 700–1500 m a.s.l. did not form on-site. The fine dust came from the bottom of the Arabian Gulf and supposedly from other coastal shelves, exposed during dry climate phases when the sea level was considerably lower than today. Winds blew the dust into the Al-Hajar Mountains where it was washed into the karst sinks during localised rains.

Paradoxically, the life-sustaining features (huyul) in the mountains result from factors specifically linked to dryness: limited rainfall created sinks but prevented excessive hollowing of the limestone; stirred-up dust from exposed sea beds could reach the mountains; the limited rainfall was strong enough to wash the dust into the sinks but not strong enough to do damage to the natural ‘flowerpots’ in some mountain parts of Oman.

1. Preliminaries

Ḥayl (pl. ḥuyul) is a local Arabian toponym. In our incipient study, we use the term ‘mountain plateau hayl’ for silt-filled depressions in mountain terrain, which usually have a diameter of approximately 100–200 m (some larger specimens reaching 0.5–1.0 km). Such features occur within fractured, horizontal limestone formations inside the Al-Hajar Mountains (Figure 1) at elevations between 700–1500 m a.s.l.1 Huyul (Figure 2) have formed through a distinctive combination of natural factors, including orography, low mean rainfall (ca. 100–140 mm/year; Kwarteng, Dorvlo & Kumar 2009: 608), desertisation, proximal sources of aeolian dust (coastal strips, inland deserts; alluvial plains) and changing monsoon and cyclone influence (Al-Zadjali, Al-Rawahi & Al-Brashdi 2021; Branch et al. 2020). These mountain places with deep sediment are put to special human use (pastoral, horticultural, hunting and soil/plant material extraction), a fact that is reflected in the appearance of the term hayl in toponyms of the area (e.g. Hayl Ajah, Hayl Salman, Al Hayl). In a study by Kharusi and Salman (2015: 21) concerning the water-related terms in Oman, the expression ‘ḥail’ is equated with ‘water which remains in a valley and stagnates’. Although primarily a hydrological rendering, this wording precisely describes the landform’s fundamental characteristic: run-off retention at the surface. With research into this landform only starting and no structural details are yet known, at present, we caution against using more standardised terms (dolina, polje). For instance, in cases such as Hayl Ajah, the sediment infill, more than the structural karst hollow itself, determines the shape and size of the feature. Moreover, some hydrological properties implied by the standard definition of a polje (see Bonacci 2013) seem to be different from e.g. Dinaric karst.

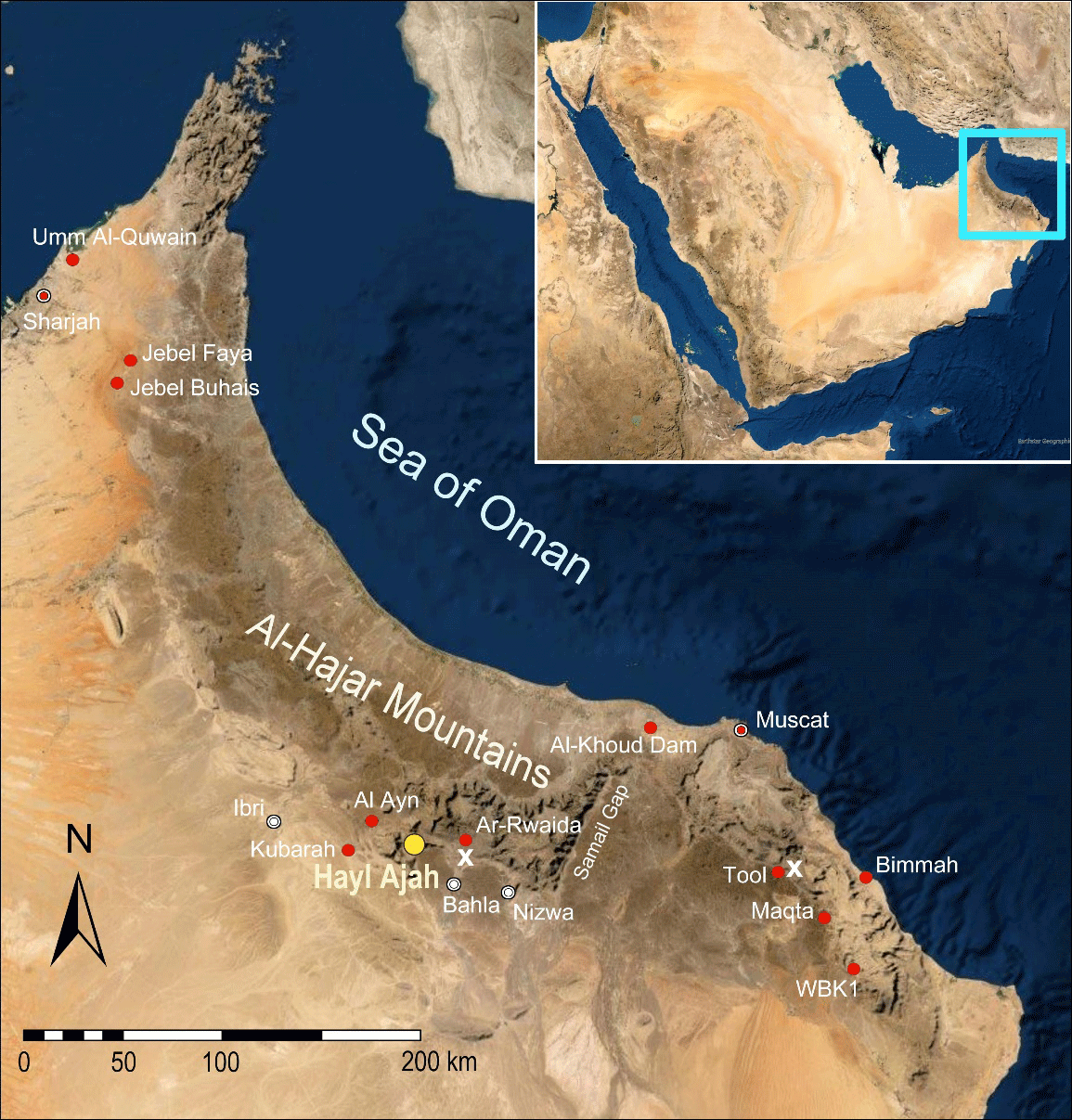

Figure 1

Al-Hajar Mountains (Oman and United Arab Emirates). Western and Eastern Al-Hajar Mountains separated by the Samail Gap. SIPO project site (yellow); sampled and mentioned sites (red); limestone plateaus similar to the Sint Karst Plateau of Hayl Ajah (x). Map source: Google Earth.

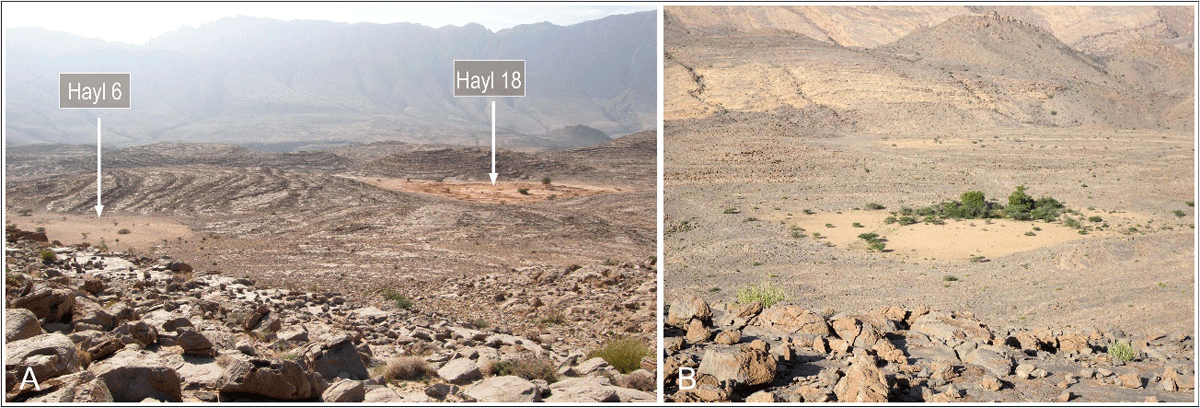

Figure 2

A: Sint Karst Plateau in November 2018, view from a hilltop towards the south-west. Left: Hayl 6 (intact silty top-layer); right: dredged Hayl 18 (terra rossa exposed). The sub-horizontal fractured karst plateau with its rhythmically spaced hillocks and huyul is separated from the slopes of Jebel Kawr by a deep wadi gorge. B: A sanctuary for mountain biota, Hayl 5 receives run-off, silt and organic matter from surrounding rock surfaces.

We have pointed to a mountain plateau huyul in previous studies (Mateiciucová et al. 2020a; Mateiciucová et al. 2023) as places-of-interest for the prehistoric archaeology of Oman because of a direct association of scattered and embedded prehistoric lithics (Mateiciucová et al. 2020b) with an exceptional quantity of layered, fine sediment in open-air settings, potential geo-archives (see Beuzen-Waller et al. 2022; Mueller et al. 2023; Parker & Goudie 2008; Parker et al. 2016; Parton et al. 2013; Woor et al. 2022; Woor et al. 2023). The prehistoric mountain site Hayl Ajah (wilayat Bahlā, Ad Dhakhiliyah, Sultanate of Oman) not only has its own climate record (due to metres of fine sediments) but also archaeological remains that actually tie in with them. The discovery of prehistoric stone artefacts (surface and embedded) associated with drier periods (Mateiciucová et al. 2020b) and artefacts without direct analogues on the Arabian Peninsula at our research site Hayl Ajah (HA1) at an elevation of 1000 m a.s.l. has led us to investigate the suitability of karstic mountain areas for sustaining animal and human life during phases of aridification (Mateiciucová et al. 2023).

Also during the recent arid period of the Late Holocene, mountain plateau huyul form attractive level spaces for dwellers up in the mountains of Oman. Capturing the run-off of their surroundings, these closed geological features with their deep sediments act as natural ‘flowerpots’, supporting important plant growth in the bleak mountain environment. The xerophytic vegetation includes plants with deep root systems reaching underground water sources (shrubs and trees) and plants with shallow, widely spread root systems maximising the use of seasonal rainfall (ephemeral herbs). Most plant species are used as fodder for animals, herbs in traditional medicine, etc. Considering also the fact that reliable, elevated water bodies (wadi pools and springs) dispersed throughout karst areas of the Al-Hajar Mountains (such as Jebel Akhdar, certain parts of the Eastern Al-Hajar Mountains and the Musandam Peninsula), together with orography and lithology, created diverse ecotopes, we can assume that karst areas have been meaningful parts of prehistoric refugia in Oman during arid periods (Mateiciucová et al. 2023; Mueller et al. 2023; Nicholson et al. 2021; Parton & Bretzke 2020; Preston & Parker 2013; Purdue et al. 2019; Woor et al. 2022).

The aim of this contribution is to describe sediment-filled karst depressions distributed on the Sint Karst Plateau at an elevation of 1000 m a.s.l. in the central part of the Al-Hajar Mountains, with particular focus on the prehistoric site Hayl Ajah. Two research questions are addressed: firstly, what is the origin of the thick sediment deposits found in these mountain features? Secondly, what factors contributed to the retention of fine sediment in the karstic depressions and prevented its loss? Through various laboratory data and field observations, we examine our assumption regarding the genesis of mountain plateau huyul, as expressed in a tentative depositional model (see section 5.2). Answering these research questions will help us to understand how these geomorphological features supported prehistoric human occupation inside the Al-Hajar Mountains of southeastern Arabia.

2. State of research

The sediment-filled karst depression as a landscape feature has previously been studied in Qatar at elevations below 100 m a.s.l. (Engel et al. 2020). There, the shallow karst depressions called rawdha (pl. riyadh), numbering about 800 and with sizes ranging from 0.4 to 4.5 km2, have formed as dissolution landforms in limestone – specifically, subsidence depressions upon collapsed gypsum cavities (Macumber 2018: 203, Figure 5). Cracks connecting the limestone base of a rawdha with the collapse zone below lead to the formation of a groundwater mound beneath it, that during maximal intake may become visible in part of the rawḍah. During periods of high sea levels, the groundwater level mounded and potable water was accessible through hand-dug wells. Conversely, during periods of sea-level decline, potable water remained inaccessible, even, though it may have been present underground (Macumber 2011; Macumber 2018: 204).

One of the first investigations to describe huyul was Gordon Stanger’s pioneering ‘Hydrogeology of the Oman Mountains’ recognizing ‘silt-veneered dolines’ (1986: 100, 102) and outlining their function for subsistence. Besides wadi runnels, Brinkmann et al. (2009: 1036) of the Omani-German project ‘Oases of Oman’ identified ‘small depressions where some sediments have accumulated in pockets’ as exclusive places of plant growth in the Jebel Akhdar massif (central Al-Hajar Mountains). A watershed moment in research was the sedimentological and palaeobotanical investigation of a sediment-filled karst depression next to the mountain oasis Maqta. At this site, ca. 1050 m a.s.l. in the Eastern Al-Hajar Mountains, a 20 m deep sounding into the sediment fill provided a 20 ka-year record of palaeoclimatic and palaeoenvironmental change (Fuchs & Buerkert 2008; Urban & Buerkert 2009), indicating a persistent, albeit declining, run-off supply even during times of reduced sedimentation (Woor et al. 2022: 12).

Undisturbed karst depressions containing metres of fine sediments higher up in the Al-Hajar Mountains have escaped the attention of archaeologists, despite harbouring substantial traces of prehistoric occupation. For instance, the huyul of our research area (a 25 km2 karst plateau bordering the intermountain basin of Sint at the foot of Jebel Kawr) reveal evidence of prehistoric occupation within and around them, including stone artefacts, pottery fragments and Bronze Age stone structures. Furthermore, huyul have been vital for local tribes in recent times to perform pastoralism and marginal agriculture (Birks 1976; Dostal 1972: Table 1; Stanger 1986: 142). Like khabras and playas at lower elevations, the mountain plateau huyul are potential sources of silt. Silt appears to be a major component of the anthroposols found in terraced oasis plots inside the Al-Hajar Mountains (Moraetis et al. 2020: 14; Nagieb et al. 2004: 93; Purdue et al. 2019: 124).

The aim of the ongoing Project SIPO (Masaryk University Brno, Czech Republic) is to draw attention to these features in the mountainous regions of Oman and the UAE and to explore their significance for prehistoric humans.

One of the key sites for studying mountain plateau huyul is the prehistoric site Hayl Ajah, a large intermontane karst depression between the ridges of Jebel Kawr and Jebel Ghul near the divide between the Western-Eastern Al-Hajar. Before embarking on more extensive archaeological work, it was necessary to understand the site’s basic environmental conditions to better comprehend human-environment interactions within this specific context.

3. Intermontane karst depression Hayl Ajah, Sint Karst Plateau

Hayl Ajah is a vast depression approximately 500 m in diameter situated on a small karst plateau between the ridges of Jebel Kawr and Jebel Ghul, 5 km south-east from the intermontane village of Sint (wilayat Bahlā). The closed feature at an elevation of 1019 m a.s.l. is set in a slightly tilted Triassic limestone formation crisscrossed by fracture lines (‘Sint Karst Plateau’, ca. 25 km2) and surrounded by hillocks that rise only 20–40 m above the flat and horizontal sediment surface (Figure 3). Hayl Ajah was previously mentioned in a geological guidebook to Northern Oman, as ‘Sint Polje’ (Hoffmann et al. 2016: 214–215). Besides Hayl Ajah, 21 smaller huyul are found on this karst plateau. Of these, 12 remain in their original state, featuring undisturbed flat surfaces formed of the same light-coloured silt as Hayl Ajah. The other nine, which recently became accessible to vehicles due to their location along a new asphalt road, have been stripped of their surface silt (reportedly for commercial use in agriculture) to an average depth of 1.5–2 m (Figure 3). In each of these cases, a deposit became visible underneath, which directly rests upon a Megalodon limestone bedrock of the Kawr Group of Oman Exotics (Bernecker 1996). Due to its characteristics and red colour, this sediment is designated as terra rossa.2

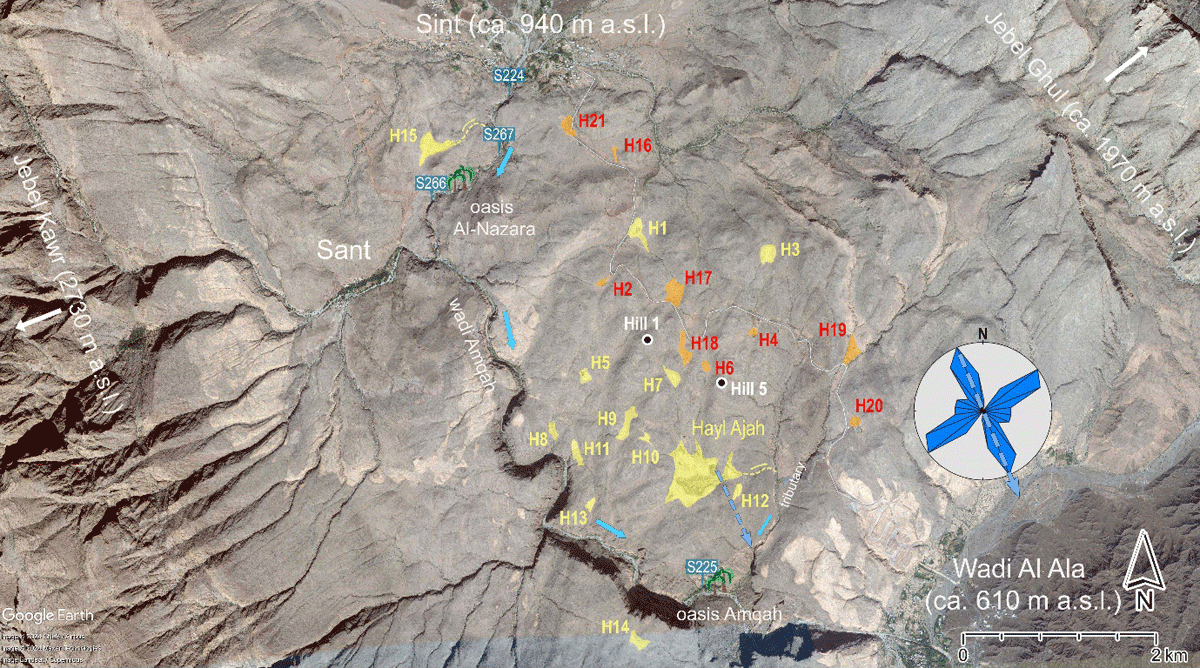

Figure 3

Sint Karst Plateau. Sediment-filled karst depressions (mountain plateau huyul), intact (yellow) and recently dredged (red). Water sampling points (blue). Sediments from the tops of Hill 1 and Hill 5 have been analysed. White line: the new road, a short-cut across the plateau to the area of Al-Hamra and Bahla. The wadi Amqah gorge drains the Sint intermountain basin. Outlying oases: Al-Nazara (abandoned) and Amqah. Overspill huyul (yellow dashed line): Hayl 15 and Hayl Ajah. Rose diagram of fissures derived from measurements within Hayl Ajah at the ponor, demonstrating the tectonic control of the preferential drainage (n = 48, max. 16.7%). Map source: Google Earth.

Calcification, identified during wet-sieving, is apparent from the calcitic nodules and calcitic casts of snail shells in the lower part (at depths of 1.7 m and 2 m) of trench GT5.

Hayl Ajah (Figure 4) has as many as seven gullies transporting suspended sediment into the hayl during hazardous rainfalls typical of the Al-Hajar Mountains (Al-Charaabi & Al-Yahyai, 2013: 4; Kwarteng, Dorvlo & Kumar 2009: 610). An elongated sediment extension that narrows to the east drains floodwater over a cliff edge (‘overspill’) into a steep gully with a series of approximately 60 kamenitzas (potholes). These can capture a total of 37,000 litres of water suitable for animals for two to four weeks after an overspill event. Overspill water flows into a short tributary leading to a precipice, below which the terraced plots of the small wadi oasis Amqah are located.

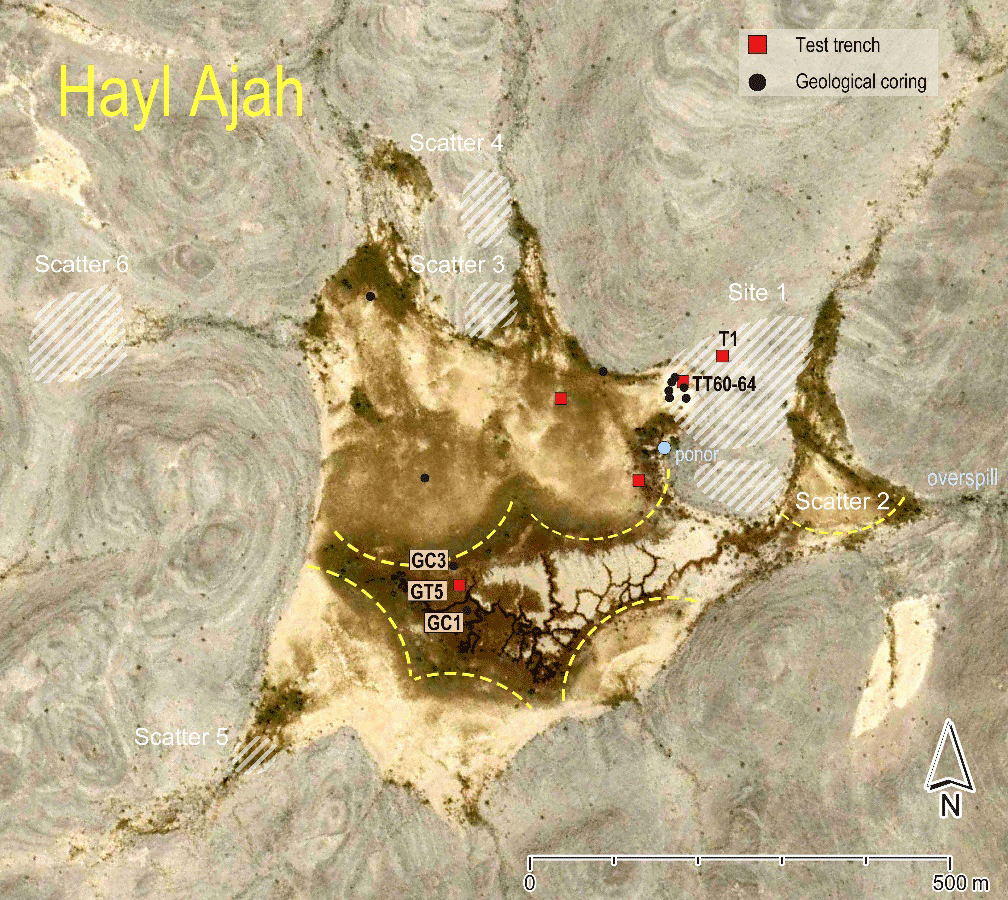

Figure 4

Karst depression Hayl Ajah. Central infiltration zone with suffosion channels and trees, defined by level silty fans in front of radial gullies. Main drill holes GC1 (2018), GC3 (2022), and the main geological-palaeoenvironmental trench GT5. Subsidiary drill holes (black dots); archaeological and geological trenches (red squares). Site HA1: archaeological test trenches T1 and TT60–64 (2018). Lithic scatters 2–6. Vertical drainage shaft (ponor). Overspill to a flanking tributary 100 m below. Map source: Google Earth.

Unlike the roughly circular shape of common karst depressions, Hayl Ajah has a jagged, star-like outline. This results from alluvial silt being banked up into the lower parts of the gullies that provide the inflow of run-off, indicating an excessive filling of the karst depression (Figure 4).

This interpretation is supported by the fact that one part of the horizontal hayl fill extends all towards the overspill point 200 m away, indicating the maximal fill level has been reached. From the entry points of the gullies, nearly horizontal alluvial fans extend into the inner part of the hayl. The semi-circular distal ends of the fans determine a central infiltration zone. This core area is recognisable mainly through vegetation changes and a grid of less than knee-deep channels, caused by the slow suffosion3 of silt.

As studies concerning the siltation problem of modern dams in Oman imply (Al-Maktoumi et al. 2020; Rajendran, Nasir & Al Jabri 2020), pluvio-alluvially redeposited silts tend to clog the substratum (see below section 5.1). The drainage of the studied mountain plateau huyul thus cannot happen solely via infiltration or percolation of rainwater through the fill sediment. We should therefore expect the drainage of the studied mountain plateau huyul to be controlled to some degree by surface run-off concentration at the contact of the barren slopes with the level silt fill (see Yair 1999: Figure 14.11).

The surface catchment area of the huge Hayl Ajah depression is less than 2 km2. The elevation difference between the entirely horizontal sediment surface of the mountain plateau hayl and the overspill height is less than 1 m (DEM by Robert C. Bryant, February 2023). Mobile phone images from residents show wave marks on a spoil heap (geological trench GT5, spring 2023) and suggest that the short-lived peak flood level after cloudbursts may reach slightly over one metre.

Inhabitants of Sint have reported that after a flooding episode that lasts less than a day, standing water fills the suffosion channels for up to four weeks (photographed in 2019; Figure 5). Periodically, following extremely heavy rains, a large portion of Hayl Ajah becomes flooded. Residents reported (pers. comm. December 2023) that after torrential rains, grass sprouts in Hayl Ajah, forming a green cover (used as a grazing reserve) over a large area of the hayl for several weeks. Initially, the temporary grass cover was considered to be specific to Hayl Ajah, but satellite imagery (Google Earth Pro; 3/2009 – 12/2024) shows that under the same conditions grass grows at other huyul as well (e.g. at Ar-Rwaida, 5 km north of Hoti Cave, and in the Eastern Al-Hajar Mountains at mountain plateau huyul near the village of Tool and also at a hayl next to the mountain oasis Maqta; Fuchs & Buerkert 2008: 549).

Figure 5

Hayl Ajah (December 2019). After covering the withered and grazed remains of former grass for less than a day, standing water fills the shallow suffosion channels in the hayl for weeks (information from residents).

The filling of Hayl Ajah to its maximum height with fine sediments and the fact that the level hayl surface is almost without holes suggests that some kind of sealing has occurred in the underground. This is indicated by the negligible sediment reduction in the form of suffosion channels, which are rather flat and wide, with an average depth of 0.5 m. The levelness not only of Hayl Ajah’s inner zone but also the flatness of the fans in front of the seven gullies emptying into the hayl can be explained by horizontal flow during flooding, that is drainage towards ponor (shaft) and overspill. On the basis of their cross-sections, the drainage elements are ranked as follows: (1) a vertical shaft (ponor) in the rock just outside the hayl; (2) horizontal overspill; (3) suffosion channels less than 0.5 m deep; (4) minor holes in the silt fill (diameter less than 1.5 m); and (5) minor infiltration improvement by desiccation cracks and roots of trees and bushes in some parts.

4. Methodological approach and methods

4.1. Preliminary terrain reconnaissance and satellite imagery analysis

In the initial phase of research, a pedestrian survey of the Sint Karst Plateau was conducted. Due to the absence of previous studies on huyul in Oman, it was necessary to develop the methodological approach directly in the field. The survey took the form of the surface examination of an area of approximately 25 km². Morphological characteristics of the depressions were recorded, along with their spatial distribution and their relationship to geological structures. Identifiable features were georeferenced using GPS devices. Geological and topographical maps (Beurrier et al. 1986; National Survey Authority 2009) were used for orientation in the field. This terrain reconnaissance was complemented by the analysis of Google Earth Pro imagery (3/2009–12/2024), which utilises satellite collections with spatial resolutions ranging from 0.3–15 m, allowing for a broader spatial perspective and landscape analysis. An iterative process of observation and interpretation made it possible to formulate a preliminary model of the origin and development of mountain plateau huyul.

Combining ground observations led early in the research to a hypothetical model of the formation of huyul on the Sint Karst Plateau. The special geological conditions for sediment retention in mountain plateau huyul (only slightly perforated soluble bedrock) are thereby interpreted as being reinforced by yet another effect caused by aridity: the availability of substantial quantities of free-moving dust from areas close to the mountain range, such as dune fields, alluvial strips and continental shelves.

4.1.1. Initial work hypothesis

Combining observations on ground has led early in the research to a hypothetical model of the formation of huyul upon the Sint Karst Plateau. The special geological conditions for sediment retention in mountain plateau huyul (only slightly perforated soluble bedrock) are interpreted as reinforced by yet another aridity effect: the availability of substantial quantities of free-moving dust from areas close to the mountain range, i.e. dune fields, alluvial strips and continental shelves.

The key observations were: (1) mountain plateau huyul and adjacent hillocks are set in an alternating pattern, (2) mountain plateau huyul are situated where fracture lines of the karst formation intersect, (3) terra rossa is overlain by a more extensive silt deposit and (4) remains of similar silt occur on the hillock tops next to mountain plateau huyul. Based on these observations, the following developmental sequence has been inferred for the studied morphological features (Figure 6):

Figure 6

Hypothetical model of silt mobility on the Sint Karst Plateau.

Fractures caused structural weakening of the karst, particularly at spots where they intersect (Figure 6:I)

Vertical drainage created solution openings at the intersection points. Increasingly sheet flows drained toward developing karst hollows carrying debris and sediments from the surrounding area (Figure 6:II).

Terra rossa developed from the accumulated sediment (Figure 6:II).

At some point, a comparatively large quantity of wind-blown silt was deposited and covered the Sint Karst Plateau (Figure 6:III).

After stagnation of this aeolian supply, silt was washed via precipitation from the higher parts of the plateau and concentrated via pluvio-alluvial flows in the low, enclosed karst depressions (Figure 6:IV–VI).

In an advanced stage of filling, muddy overspill occurred, which together with the proximity of reliable water sources enabled the establishment of outlying oases next to the Sint Karst Plateau (Figure 6:VII–VIII).

This model subsequently became the conceptual framework for structured research, including a targeted sampling for laboratory analyses. Moreover, it led to analyses that produced Yes/No answers. This proved decisive when embarking on the environmental-archaeological assessment of a landform not previously described in greater detail in prehistoric studies.

4.2. Used methods

The relief of the jagged, steep Al-Hajar Mountains in combination with torrential rains produces erosional forces and steep landforms that are not by themselves favourable for the retention of fine sediment at higher elevations. Hence the origin of the deep, fine sediment at 20 or more locations within an area of only 4 x 5 km at 1000 m a.s.l. required explanation. To understand the retention effect, it was necessary to study the topography of the Sint Karst Plateau in a more synoptic fashion. Conventional satellite imagery (Google Earth Pro) was used to recognise the larger-scale structural elements on the surface of the studied karst formation and to obtain approximate 3D information. Besides the origin of the deep fine hayl sediment, another fundamental question concerned the depositional properties of mountain plateau huyul of which flooding after local storm events is certainly the most striking (‘stagnant water’ as echoed by native etymology, see section 1). To answer these questions, three laboratory methods were applied: translucent heavy mineral analysis, micropalaeontological analysis and hydrochemical analysis.

4.2.1. Translucent heavy mineral analysis

To check our assumption regarding the aeolian provenance of the infill of huyul on the Sint Karst Plateau (Mateiciucová et al. 2020a), we used heavy mineral analysis. This technique makes it possible to distinguish between autochthonous materials formed by on-site weathering and allochthonous materials transported from external sources.

Initially, heavy mineral analysis was carried out on two sediment samples from Hayl Ajah, extracted in 2018 at depths of 2 m and 4 m b.s. at borehole GC1. To confirm the aeolian origin suggested by these initial tests, additional 19 sediment and rock samples were subsequently analysed (Supplementary Files 1 & 2). Regarding Hayl Ajah, six samples from borehole GC3 (depth 3.3 m), approximately 50 m away from borehole GC1 (depth 4.1 m), were examined (Figure 4). Both boreholes GC1 and GC3 were drilled in the central part of the karst depression. Furthermore, one sediment sample from the top of Hill 5 northeast of Hayl Ajah was analysed (red sediment overlying limestone bedrock, hence designated as terra rossa). Other samples were collected from Hayl 15 and Hayl 19, as well as from the terraced plots of the oasis Amqah directly below the Sint Karst Plateau, and from the abandoned oasis Al-Nazara below the karst depression Hayl 15 (Figure 3). One soil sample was obtained from a horticultural plot directly in the Sint village. For comparative studies, four rock samples were extracted from the Samail Ophiolite complex (pyroxenic tuff, tectonic mélange, pyroxenic basalt and harzburgite-derived sand) within the Sint Drainage Basin (Figure 10).

For broader regional context, five samples from more distant areas were analysed. Three samples represent coastal sand deposits from the Sea of Oman and the Arabian Gulf. Two comparison samples were collected in the Eastern Al-Hajar Mountains: one from a karst depression near the mountain oasis Maqta and one from the fortified Iron Age settlement, WBK1, in the Wadi Bani Khalid (Loreto 2020).

All heavy mineral samples underwent a standard preparation protocol. Samples were washed and sieved to fractions of 0.06–0.25 mm, then dried and separated using an LST non-toxic heavy liquid. Heavy minerals were determined and enumerated using an Amplival Karl Zeiss polarising microscope at the laboratories of the Czech Geological Survey in Brno. For each sample, 400 to 500 grains were counted. Results were evaluated in modal percentages (i.e., grain quantities irrespective of size or mass). The ZTR index (percentage of zircon + tourmaline + rutile) was calculated for each sample to quantify ultra-stable minerals in each assemblage.

4.2.2. Micropalaeontological analysis

The sedimentological investigation was complemented by a micropalaeontological analysis. Microfossils – particularly foraminifera and ostracods – serve as sensitive indicators of depositional environments and can reveal the marine origin of certain sediment components (see below sections 5.3 and 6.1). In this study, we analysed 14 sediment samples from the Sint area and seven comparative samples from various locations across Oman and the UAE (Supplementary File 3).

From the Sint area, our analysis covered four sediment samples from borehole GC1 at Hayl Ajah, one silt sample from the top of a hillock above the Hayl Ajah site, three samples from Hayl 19 (including a terra rossa sample from the base of a section) and one sample from Hayl 15. To ascertain the origin of silt used at terraced plots, we analysed three samples from the Amqah oasis and one from the oasis Al-Nazara. Further-afield comparative samples included four from the northwest: two from the Arabian Gulf coast and two from the anticlines of the Western Al-Hajar Mountains near the prehistoric sites of Jebel Faya and Jebel Buhais. From the north, we analysed one beach sand from Muscat, whilst from the Eastern Al-Hajar Mountains, we examined one sample from a karst depression near Maqta oasis and another from the prehistoric site WBK1 in the Wadi Bani Khalid.

All samples were processed at the laboratory of the Czech Geological Survey in Brno. The sediments were immersed in a sodium carbonate solution and washed using a 0.06 mm sieve. The microfossils were subsequently manually extracted under a Jena Zeiss binocular microscope and preserved in cardboard microslides.

4.2.3. Hydrochemical analyses

To complement the sedimentological investigations, we conducted hydrochemical analyses to detect subsurface drainage systems. These analyses provided insights into anthropogenic contamination and changes of the composition due to the gradual decrease of ophiolite influence downstream the wadi Amqah (Figure 3). The analytical protocol included pH values, electrical conductivity measurements and quantification of major cationic and anionic constituents.

Water samples were taken to: (1) determine the general chemistry, (2) evaluate settlement impacts on water quality at the foot of the Sint Karst Plateau, (3) understand the influence of local ultramafic and mafic rocks on water composition, and (4) compare with water from carbonates and other rocks.

Four water samples were collected in February 2023 in the wadi gorge between the village of Sint and the oasis Amqah. These included samples from a wadi pool immediately downstream of Sint (situated in an ophiolite basin), a spring below the abandoned oasis Al-Nazara and two presumed resurgences of water infiltrating the Sint Karst Plateau. From each source (wadi pool, spring and falaj), 500 ml of water was transferred into PET bottles, sealed and transported to Czechia for comprehensive chemical analyses at the accredited laboratories of the Czech Geological Survey in Prague-Barrandov.

5. Results

As follows, recent analyses confirm some of the basic tenets of the initial working model.

5.1. Satellite imagery and field prospection

The working model for the Sint Karst Plateau has emphasised the role of intersecting fracture lines for the positioning and forming of the sediment-filled depressions. This has been deduced from satellite images (Google Earth Pro; Image © Airbus 2025). Meanwhile fissure systems were measured and evaluated in the field near the main ponor (drainage shaft) during the Spring Season 2023 (Figure 3). Hillocks, having approximately the same absolute height, can be interpreted as pyramidal remnants of a formerly continuous level limestone plateau that has acquired its current (modest) height differences primarily through the development of closely spaced karst hollows. Recently, when using conventional satellite imagery to check the upper size limit of huyul at two other mountain areas where such features occur (Figures 1 & 7), a similar crosshatch patterning of part of the limestone formations (caused by fracture lines) was noticed.

Figure 7

Sub-horizontal plateaus comparable to the Sint Karst Plateau with mountain plateau huyul (sg. hayl) at other karst formations of the Al-Hajar Mountains above 1000 m a.s.l. (A: north-east of Hoti Cave and Ar-Rwaida; B: north-east of Tool).

One area near the Hoti Cave and Ar-Rwaida lies approximately 30 km east of Hayl Ajah and the other 140 km further east, in the upper catchment of the wadi Dayqah not far from Tool in the Eastern Al-Hajar Mountains (see also Stanger 1986: 102). The first area has an elevation of approximately 1470 m a.s.l., and the area farther away an elevation of approximately 1100 m a.s.l. At both places identified via satellite imagery, alluvial sediment is retained upon thick carbonate sequences (Natih Formation and Kahmah Group, both Cretaceous; Celestino et al. 2017; Homewood et al. 2008) which are fractured similarly to the Sint Karst Plateau. These karstic limestone formations, too, form plateaus with an inclination of little more than 5%. The size of the mountain plateau huyul differs considerably. On the karst plateau near the Hoti Cave, besides several small sediment places, only two to three larger huyul were identified, which are about half the size of Hayl Ajah (i.e. approximately 250 m in diameter). On the more distant karst formation near Tool, three to four huyul are half the size of Hayl Ajah, but other huyul there are twice as large as Hayl Ajah (up to 1 km in diameter). Despite the ruggedness of the limestone formations, the nearest settlements are located no more than 3 km from Hayl Ajah (as the crow flies): those in the vicinity of the Hoti Cave approximately 2 km away, whilst settlements in the more distant Eastern Al-Hajar lie between ca. 1 to 3 km away.

Using satellite images, besides a hayl resembling Hayl Ajah (fans, channels, concentric plant growth), a mountain plateau hayl with a diameter of approximately 600–700 m was discovered in the Eastern Al-Hajar Mountains, which suffers significant sediment loss (now to a depth of about 9 m). The lowering of the infill in one half reveals circular cracks on the sediment surface with a diameter of 80–90 m which are presumed to delineate an original doline at the bottom in the central part of the mountain plateau hayl (Figure 8). The rock outside the hayl shows irregularities which, based on our survey experiences, result from fractures. Substantial plant growth is restricted to the funnel-shaped part where massive sediment loss has happened (due to a major collapse underground?).

Figure 8

Contour of a circular doline at the bottom of a mountain plateau hayl (ca. 980 m a.s.l.), approximately 10 km west-northwest of the settlement Tool (Eastern Al-Hajar Mountains).

Satellite imagery of other formations, combined with our field knowledge of the Sint Karst Plateau, reveals two key patterns: (1) Almost horizontal karst formations with dissected surfaces formed preferential features (inclination about 5%) able to capture, concentrate and preserve windblown sediment higher up in the Al-Hajar Mountains. (2) Human activity at these higher elevations is spatially linked to mountain plateau huyul.

5.2. Translucent heavy minerals

The results of heavy mineral analysis are illustrated by a ternary diagram and pie charts. Three end members of the ternary diagram were selected to quantify differences and similarities between silt deposits and terra rossa samples: amphibole (hornblende) in the left-hand corner, pyroxene + olivine + chromspinel at the top and other minerals in the right-hand corner (Figure 9). The reasons for such division are as follows:

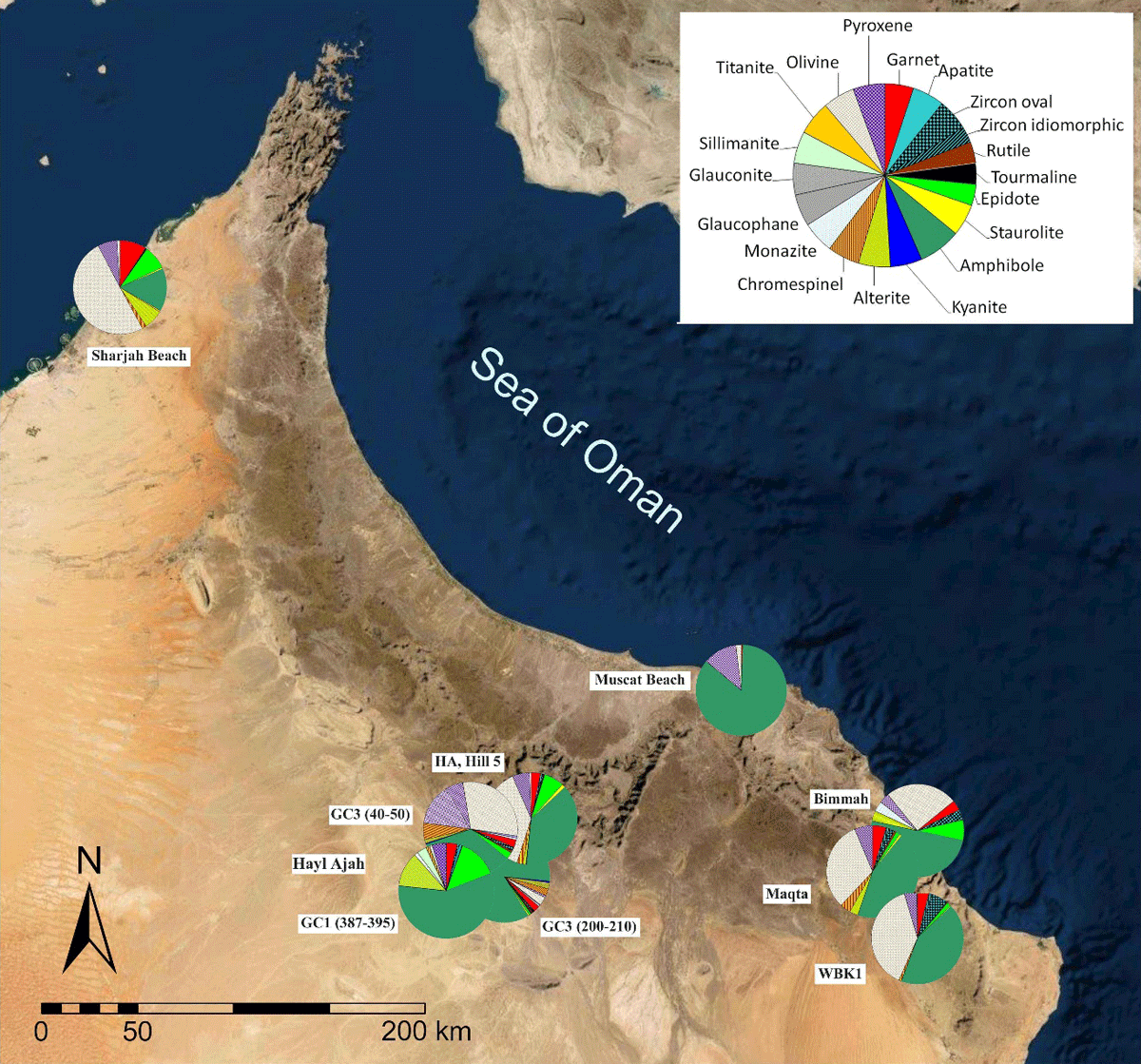

Figure 9

Translucent heavy mineral analysis (Supplementary File 1). Comparison of sediment samples from Hayl Ajah and surrounding huyul, from the nearby oases Al-Nazara, Amqah and Sint and from a karst depression at the mountain oasis Maqta (Eastern Al-Hajar Mountains) with potential source rocks from local and distant areas. The top corner indicates relation to an ophiolite suite source (pyroxene, olivine and chromspinel) and the left-hand corner an association with amphibole. The right-hand corner refers to remnant minerals from more distant sources.

Mafic and ultramafic rocks of the Sint Basin (Figure 10) contain significant minerals – olivine and/or pyroxene, and occasionally chromspinel in all cases.

The significant mineral of silts – wind-blown and subsequently washed into depressions – is amphibole (hornblende). Notably, amphibole minerals were absent from all tested samples within the Sint ophiolitic basin. This absence suggests that the amphibole originates from a more distant source rather than local ophiolitic materials.

The remaining minerals, such as epidote, garnet, alterite, etc., are generally of external, distant origin.

Figure 10

Translucent heavy mineral composition in sediment and rock samples of the Sint Karst Plateau and ophiolitic (dark-coloured) Sint Basin (Supplementary File 2). Comparisons of relative proportions of translucent heavy minerals in sediments from huyul (Hayl Ajah, Hayl 15, Hayl 19), top of Hill 5 and oases horticultural plots (Al-Nazara, Amqah and Sint) with primary sources from the Sint Basin. Map source: Google Earth.

Analyses of translucent heavy minerals (Figure 10) from boreholes GC1 and GC3 at Hayl Ajah show that silts from various depths down to 4 m consistently have a high proportion of non-local amphibole. Only the sample from the upper part (<0.65 m) of borehole GC3 differs, with a higher representation of ophiolitic minerals occurring in the Sint Drainage Basin. Similar results were obtained from Hayl 19 and Hayl 15, where silts again exhibit a predominance of amphibole. Comparable results with significant amphibole content were registered in sediments from the nearby horticultural terraces of the oasis Amqah and the oasis Al-Nazara. Although amphibole occurs in ophiolites in the Al-Hajar Mountains, comparative analyses of ophiolitic rocks in the vicinity of Sint demonstrate that the main components there are olivine and pyroxene supplemented by chromspinel and that amphibole is almost missing. Amphibole can therefore be considered as non-local, with wind being the principal transport vector prior to pluvio-alluvial redeposition in the karst depressions (Mateiciucová et al. 2020a). Wind transport is also unequivocally evidenced by the analysis of reddish sediment (designated as terra rossa) retrieved from the top of Hill 5 of the Sint Karst Plateau, which likewise shows a higher proportion of amphibole.

The mineral composition of the silty sediment at Hayl 19 differs significantly from its basal layer of terra rossa, which is composed primarily of olivine minerals (approximately 90%) and thus has an affinity with the ophiolite rocks in the Sint Drainage Basin. However, the terra rossa at Hayl 19 has not been formed in situ from the residuum of the limestone bedrock. Rather, its pedogenesis was significantly influenced by an aeolian component in which ophiolitic minerals from the immediate vicinity predominated. The terra rossa contains epigenetic CaCO3 aggregates and particles of (evaporitic) gypsum crystals.

In summary, the infill of huyul on the Sint Karst Plateau consists of silt dominated by non-local amphibole. A sand sample from the Sea of Oman coast near Muscat shows similarly high amphibole representation (Figure 11). Compared to that, surface sediments from the Eastern Al-Hajar Mountains obtained from a karst depression near the Maqta oasis (see Fuchs & Buerkert 2008; Urban & Buerkert 2009) and from the fortified Iron Age site Wadi Bani Khalid (WBK1) contains a significantly lower amphibole proportion, same as sediments near Bimmah sinkhole. However, all these surface sediments also contain a significant ophiolite component (source not specified) and thus resemble samples from the top of Hill 5 and from the upper part of the borehole GC3 at Hayl Ajah. Comparably lower amphibole content was found in a sand sample from the coast at Sharjah City, UAE (Figures 10 & 11).

Figure 11

Translucent heavy mineral composition in sediment samples of selected sites in the south-eastern Arabian Peninsula (Supplementary File 2). Map source: Google Earth.

5.3. Microfossils

Based on the microfossils in samples from Hayl Ajah, nine groups of microfossils were defined. Their presence and relative abundance in comparative samples have been evaluated in terms of provenance. The quantitative composition of microfossils in samples from borehole GC1 (depth 4.1 m) and from surrounding sites on the karst plateau is characterised by a dominance of foraminifera of the Ammonia-Elphidium association and ostracods (up to 77% in GC1). The similarity between the microfossil content of silt preserved atop Hill 1 north of Hayl Ajah and the main deposits at Hayl Ajah confirms their aeolian origin (Figure 12).

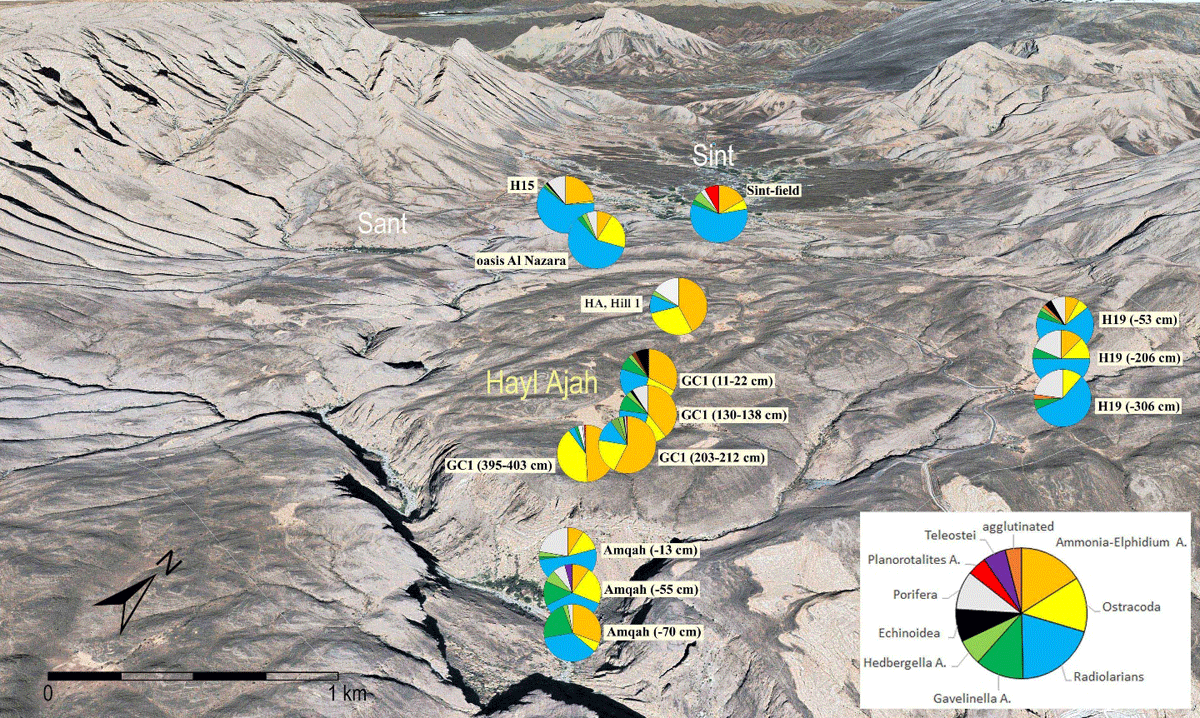

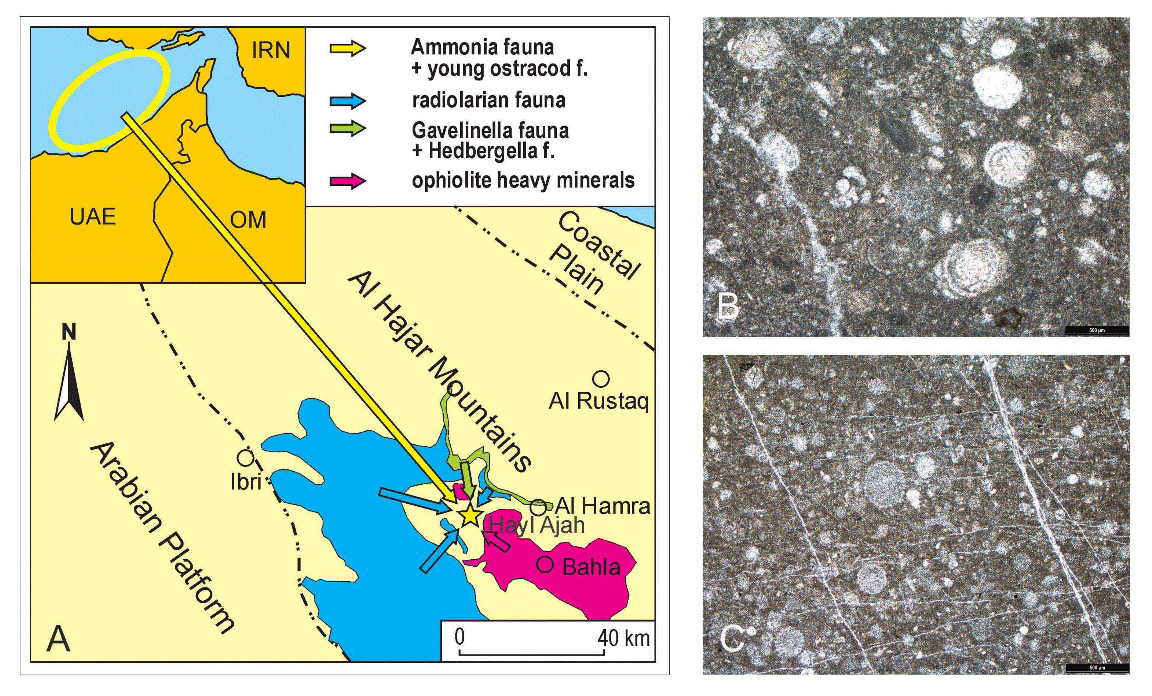

Figure 12

Micropalaeontological compositions in sediment samples of the Sint Karst Plateau and Sint Basin (Supplementary File 3). Comparison of microfossil proportions in sediment samples from Hayl Ajah (borehole GC1), Hayl 15 (depth 30 cm) and Hayl 19, together with samples taken from the top of a hillock (Hill 1) and from horticultural plots in the oases Al-Nazara, Amqah and Sint. Map source: Google Earth.

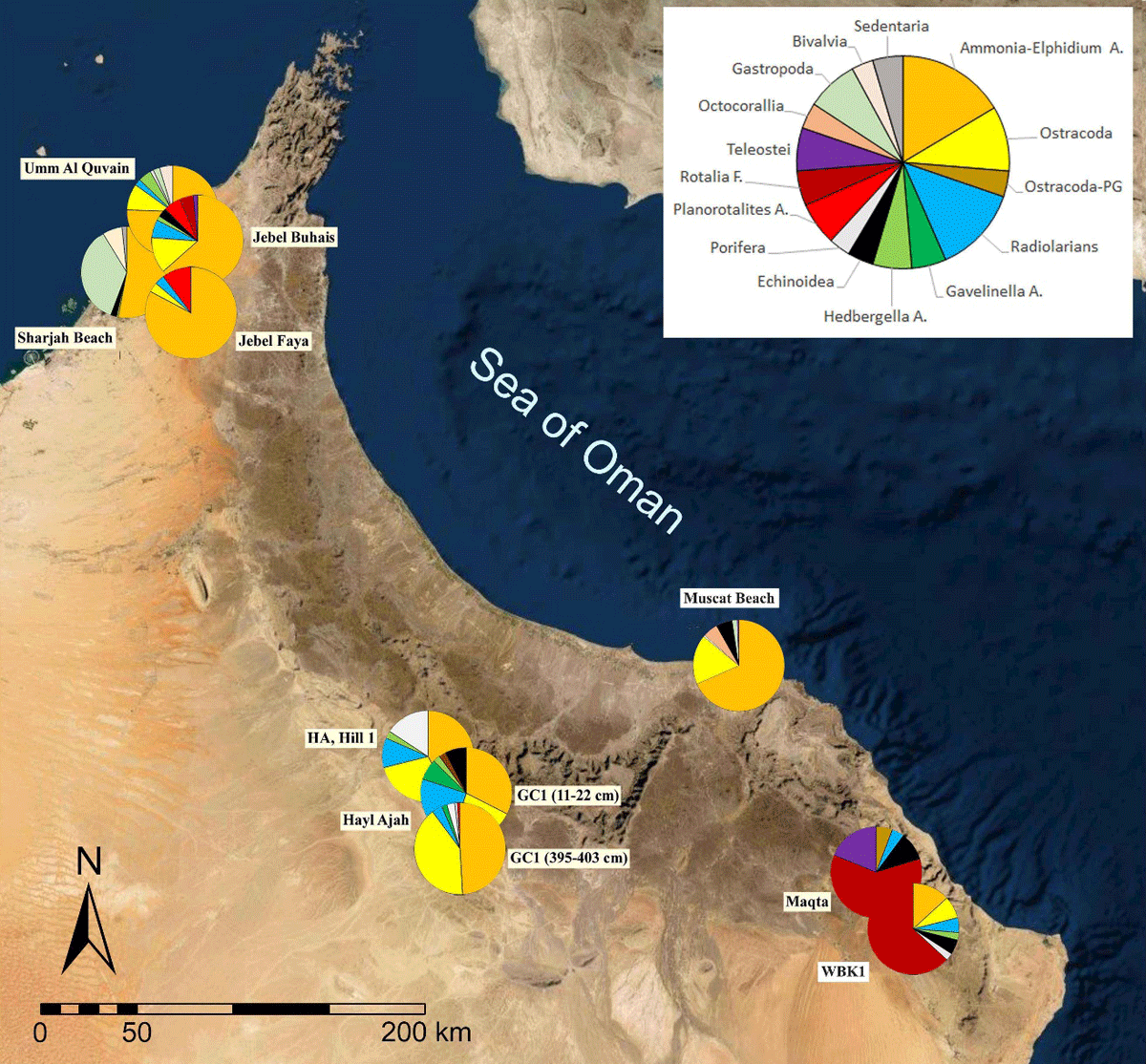

Both faunas originate from the same source and seem to originate from Quaternary or older coastal shelf deposits exposed during the marine regression of the Arabian Gulf or the Sea of Oman (Figure 13). This supposition is consistent with the similar share of these microfossils in surface samples from locations in the UAE (shore sabkhah at Umm Al Quwayn and the inland sites of Jebel Faya and Jebel Buhais). The composition of the microfauna in marine fine sand from Muscat is generally similar due to comparable biofacies but differs regarding preservation (fresh foraminifera shells versus the recrystallised shells of Hayl Ajah). Remarkably, whilst the silt drilled in the centre of Hayl Ajah (borehole GC1) contains allochthonous, stratigraphically young foraminifera and ostracods, most of the samples taken elsewhere on the Sint Karst Plateau and in the neighbouring Sint Drainage Basin contain radiolarians and older foraminifera from rocks in the surroundings. The absence or low content of young foraminifera and ostracods in the latter samples can be explained by their Holocene age. During the Holocene the source in the Arabian Gulf disappeared due to marine transgression. The Cretaceous Gavelinella and Hedbergella fauna (foraminifera) in these cases may come from Upper Cretaceous marine sedimentary rocks exposed not far from Hayl Ajah in north and north-eastern direction, whilst radiolarians come from Jurassic outcrops north and south of the Sint Drainage Basin, with another potential source to the north-west (approximately 25 km away, at Al-Ayn). The Triassic Megalodon limestone matrix of the Sint Karst Plateau itself contains neither radiolarians nor other weathering-resistant microfossils. Consequently, it does not contribute to the microfossil pseudoassociations of Hayl Ajah silts.

Figure 13

Microfossil pseudoassociations (Supplementary File 3). Comparative analyses reveal similarities between the dominant Ammonia-Elphidium and ostracod fauna found in the silty infill of Hayl Ajah and distant coastal sediments. Map source: Google Earth.

A consistent composition of the microfossil pseudoassociations throughout the GC1 borehole section indicates that the source of the silt material has basically stayed the same during the deposition of the uppermost 4.1 m of sediments in the centre of Hayl Ajah.

In the GC1 borehole section, a moderate quantitative shift from the Ammonia-Elphidium and ostracod fauna to local Jurassic-Cretaceous microfossils (radiolarians and foraminifera) is noticeable from a depth of approximately 3 metres upwards (Figure 12). This change may either signify a weakening of the aeolian contribution from the distant source on the Arabian Gulf or an increase in the proportion of mountain sediments. The silt from a hayl of the mountain oasis Maqta in the Eastern Al-Hajar Mountains completely lacks the young microfauna of Ammonia-Elphidium and ostracods encountered at Hayl Ajah.

The higher content of Ammonia-Elphidium and ostracods (21–36%) in the deeper soil layers of horticultural terraces of the Amqah oasis (Figure 12) indicates that silt transported by overspill from Hayl Ajah in an earlier phase of their building contributed 30–50% to the used material, whilst the surface layer with a greater share of Porifera spicules, abundant in sediment of the Hayl 19, seems to reflect a reworking from the upper part of the tributary catchment. When comparing the sediment sample from Hayl 15 with the sediment of the oasis Al-Nazara below it, a similarity in the composition of the microfossil content can be observed. Unlike Hayl Ajah and also to a greater extent than in the oasis Amqah, radiolarians redeposited from Jurassic outcrops are significantly represented. However, Ammonia-Elphidium and ostracods are also present.

5.4. Water analysis

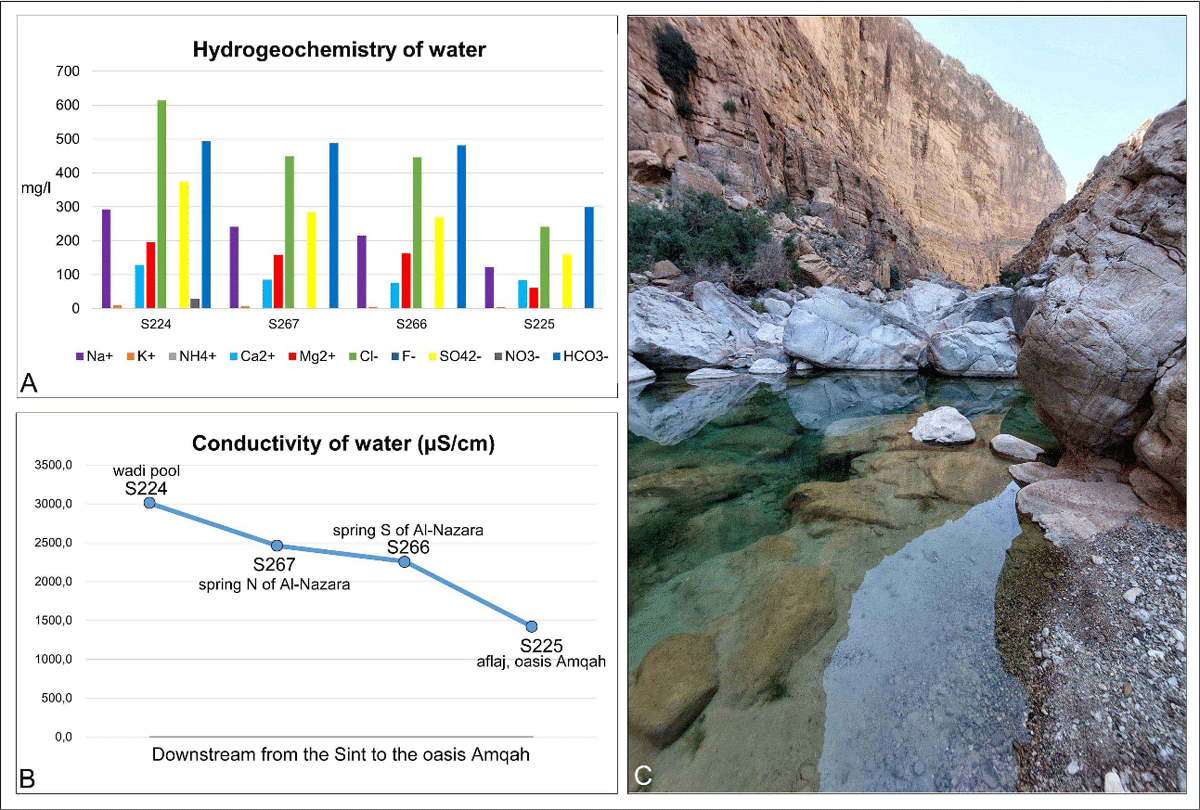

All water samples were taken in the wadi Amqah gorge. The first sample up-drainage from a pond just below the contact with ophiolites (S224), the second one from a tiny spring below the abandoned village Al-Nazara (S267), near to the largest pond in the upper section of the gorge another spring was sampled (S266) and finally one sample was taken from the Amqah oasis head waters (S225) in the lower section of the wadi gorge (Figure 14). S266 and S267 are water samples from springs in the gorge at the contact of Triassic limestone with ophiolite rocks. S225 further downstream probably represents water that originates directly from the mentioned karst formations, including the Sint Karst Plateau.

Figure 14

Hydrogeochemistry (A) and conductivity (B) of water samples taken in the wadi Amqah gorge. The samples are ordered downstream. C: Wadi pool with Garra fish at the head of the falaj irrigation channel of Amqah oasis (view up-drainage).

The high contents of magnesium and other metal elements (A) are undoubtedly a reflection of the passage of water through the rocks of the ophiolite complex. The high contents of NH4+ cations (ammonia) and Cl–, SO42– and NO3– anions (chlorides; sulphate; nitrates), however, is presumably caused by anthropogenic activity upstream in the intermountain basin of Sint (agricultural measures like the use of fertilisers). These minerals, same as the conductivity, are, however, gradually decreasing downstream in the samples. The lowest conductivity and mineralisation, together with the lowest pH, is found in the water taken from a wadi pool upstream the oasis Amqah which lies at the foot of Hayl Ajah (S 225). The linear alteration concerning these parameters can be interpreted as a gradual ‘dilution’ of water flowing from the Sint ophiolites by waters from the carbonate massifs Jebel Kawr and Jebel Ghul.

6. Discussion

6.1. Aeolian provenance of the infill sediments terra rossa and silt

The preliminary analyses of the sediments filling the karst depressions on the Sint Karst Plateau provide significant insights into their provenance and the depositional circumstances. The analyses indicate that both the parental materials of the terra rossa base layer and overlying silt beds were transported via aeolian-alluvial processes and represent redeposited material.

The terra rossa, which forms the basal stratum in excavated huyul across the plateau, displays in Hayl 19 a mineral composition derived from the ophiolites of the Sint Drainage Basin, characterised by abundant olivine together with pyroxene and chromspinel. This composition indicates weathered ophiolitic material transported to the Megalodon (Triassic) limestone via aeolian-alluvial processes, subsequently transformed within the karst environment, rather than representing an in situ dissolution product. The overlying silt layers are dominated by non-local amphibole supplemented by garnet and epidote. Although these minerals may originate from the Al-Hajar Mountains, they are absent from the immediate surroundings of the Sint Karst Plateau (Figure 10), suggesting a more distant source than the ophiolite complex of the Sint Drainage Basin. Notably, sediments taken from the terraced field plots of the outlying oases Amqah and Al-Nazara exhibit similar mineralogical characteristics like the mountain plateau huyul up on the Sint Karst Plateau. The placement of these outlying oases in locations where excess silt has spilled over from karst depressions indicates a profound environmental understanding by the early settlers.

The aeolian origin of huyul sediments is corroborated by micropalaeontological evidence. The silts of Hayl Ajah contain substantial proportions of the Ammonia-Elphidium foraminifera association and ostracods and resemble microfossils from surface samples collected in the UAE and Oman (Umm Al Quwayn, Jebel Faya, Jebel Buhais, Muscat), likely derived from exposed Quaternary or older marine shelves. The radiolarians that predominate in Hayl 19 and Hayl 15 sediments are also not indigenous to the Megalodon limestone – their nearest sources are found in Jurassic outcrops north and south of the Sint Drainage Basin. Compelling evidence for aeolian transport comes from the comparative analyses of hilltop sediments, where the microfossils and heavy minerals absent from the limestone bedrock could only have arrived via wind.

Both mineralogical and micropalaeontological analyses prove that huyul infills represent material of aeolian origin that underwent pluvio-alluvial redeposition. Importantly, these preliminary data suggest promising avenues for further hayl research rather than definitive conclusions. Creating a robust chronological framework through OSL (Optically Stimulated Luminescence) and radiocarbon dating is a precondition for correlating aeolian deposits with known climatic fluctuations and human occupation phases in the region. Absolute dating of the sediment sequences must be established before a further-reaching interpretation can be offered (in preparation).

Given the limited availability of specific publications on this elementary landform, the above results are now placed within the framework of more general depositional observations from the mountain plateau huyul and supplemented by a modern-day analogy (silting-up of dam reservoirs).

6.2. Silt gathering

Due to the lower precipitation rate in the northern part of Oman, the corrosion openings forming in the karstic limestone of the Al-Hajar Mountains remained relatively small, with calcification (see Stanger 1986: 102) secondarily reducing the porosity of the limestone. From this perspective, the limited amount of rainfall in the Al-Hajar Mountains has allowed pluvio-alluvial transport of aeolian sediment in suspension but has prevented hollowing of the limestone to such a degree that the settling of fine sediments upon the karst surface would be made impossible. Apart from this factor, plant cover, intergranular moisture and carbonate cementation have contributed to silt stabilisation.

In 2018, silt deposits very similar to the infill of Hayl Ajah were found in a small deepening at the very top of a hillock (Figure 3) approximately 1 km away (Samples S1 and S2 in Mateiciucová et al. 2020a: Fig. 2b). This observation suggested initial transport to the hilltop by wind and subsequent pluvio-alluvial transport (via surface and channel run-off) to the lower-lying places of the fractured karst formation (karst depressions).

Precipitation in the Al-Hajar Mountains is often characterised by cloudbursts, producing at times localised flash floods (Al-Ismaily et al. 2013: 4; Kwarteng, Dorvlo & Kumar 2009: 610). Torrential flows, augmented by the pronounced rain splash known from the Al-Hajar Mountains, can remobilise aeolian deposits and create flows of silt in suspension. Notably, relatively small amounts of heavy rainfall suffice to move fine sediment in an eroded arid landscape (Saber et al. 2022a: 366; Saber et al. 2022b: 402) and even more so in the steep terrain of the Al-Hajar Mountains (Al-Mamari et al. 2023: 7; on soil loss). This means that cloudbursts in the mountains (Branch et al. 2020: 68) contribute to silt mobility more than do longer, more frequent and mild rainfalls (for a direct correlation of soil loss and precipitation, see Al-Mamari et al. 2023: Fig. 12).

Unlike Dhofar, which experiences 45.9 days of rainfall per year, the Al-Hajar Mountains receive rain on only 13 days annually on average (Kwarteng, Dorvlo & Kumar 2009: Table II). Of these 13 days, 1.5 days bring heavy to extreme rainfall. In contrast, Dhofar experiences light rainfall (<10 mm) on 42.7 days, whilst heavy (25–50 mm) and extreme (>50 mm) rainfall accounts for only 0.6 days, representing merely 1.3% of annual rainy days.

Infrequent yet rather intense rainfall appears to be one of the important factors in the formation of huyul. Another factor is the nature of adjacent hills from which the aeolian dust is washed down. The slope gradient of the hills is important, and also whether the slopes are rocky or vegetated (Yair 1999). Rather, low hills (only 30–40 m above the surrounding terrain) with gentle, rocky slopes, lacking vegetation are apparently advantageous. Aeolian dust on rocky slopes, unanchored by vegetation, is easily washed into drainage channels during heavy rains and subsequently moved as bedload in channel flows into huyul. Since it rains only a few days per year, moisturised silt accumulated in karst depressions has sufficient time to properly settle and become vegetated.4 The hills rise only tens of metres above the surrounding terrain. Combined with infiltration through fissured karst rocks, flows are not strong enough to breach the depression edges, thereby preventing complete silt loss.

The rainfall in the Al-Hajar Mountains, which is intermittent but locally forceful, thus creates the pulses that move aeolian sediments through the mountain landscape and concentrate them in mountain plateau huyul or in ghabrat (Mateiciucová et al. 2023; Swerida et al. 2024), without breaking the retaining features open.

6.3. Silt sealing

To understand the depositional process that happens after alluvial silt becomes trapped in karst depressions, one can look at the situation at modern recharge dams in front of the Al-Hajar Mountains. This will allow for a better understanding of the interrelation between the rising silt levels, flooding, and overspilling observable in mountain plateau huyul.

The first retention dams in Oman were constructed about 50 years ago to harness flash floods as they pour out of the Al-Hajar Mountains during the ingression of low-pressure systems (Al-Zadjali et al. 2021; Kwarteng, Dorvlo & Kumar 2009). Dams like Al-Khoud should prevent rainwater from being lost either to the sea or to deserts and from damaging infrastructure, instead allowing it to recharge aquifers via infiltration basins downstream of the dam. However, silt from flash floods has since aggraded to several metres in some reservoirs, reducing the infiltration rate. As a result, incoming floodwater, too, can no longer be fully accommodated. This can lead to overtopping, whereby the muddy water seals the ground downstream of the dam, lengthening its flow path (Al-Maktoumi, 2018: 116; Al-Saqri et al. 2016: 4).

As a silt-straining experiment using sand-filled glass cylinders by Faber et al. (2016) has demonstrated, dam silting involves a progressive clogging of subsurface porous environments with fine silt particles.

The experiment indicates that silt particles in water – if smaller than 1/6 of pore size (Faber et al. 2016: 3) – can be expected to dissipate through parent soil of alluvial gravels. Silt particles accumulating or dragging inside the coarse substrate lower hydrological conductivity. This physico-chemical process causes a ‘plastering’ inside the parent soil over time, while dissolved calcium can form a blocking calcification front within the substrate (Al-Saqri et al. 2016: 4). The recharge zone beneath dams suffers from the same problem (Al-Saqri et al. 2016: 7; Faber et al. 2016: 2), since overspilling water carries fine suspended particles that move vertically into the substrate, reducing hydraulic conductivity and impeding infiltration (Al-Maktoumi, 2018: 117).

For huyul, a similar decelerating effect can be assumed for pluvio-alluvially deposited aeolian sediments that came into contact with the poorly sorted debris layers presumably found at the bottom of the karst depressions. Reduced infiltration at depth, however, causes an additional clogging effect because it reduces seepage and gives suspended silt particles more time to settle already on the flooded surface (see Veress et al. 2015: 424–425). This could cause fine sediment deposits in flooded parts of a hayl that further restrict water penetration, as exemplified by the silt caking observed in the glass cylinder experiment by Faber et al. (2016: 9–10). Through water sorting, the rising sedimentary fill of Hayl Ajah will have undergone an upward fining that enhances the sealing effect, causing floodwater to pool rather than infiltrate (Al-Saqri et al. 2016).

Filling gradually over time, some mountain plateau huyul (Hayl Ajah, Hayl 15) reached a maximum fill and released silty flows to lower elevation during storm events. Where the moving pluvio-alluvial silt met accommodation spaces (for instance at the foot of screes, in wadi bends, in alluvial deposits or natural sinks), it accumulated and formed a key resource provided by the Al-Hajar Mountains for creating oasis anthroposols (see Moraetis et al. 2020). Our analyses confirm this relationship, showing marked similarity between sediments from the Amqah oasis terraced plots and Hayl Ajah 200 m above, and between those from Al-Nazara oasis and Hayl 15.

Upstream of both oases, wadi pools with clear water feed traditional aflaj irrigation channels. Our hydrochemical analyses show that the pool supplying Amqah is not fed by surface water from the ophiolitic Sint Drainage Basin, but rather by water seeping from the Sint Karst Plateau. This exemplifies a complex hydrological-sedimentary system in which karst fissures and huyul together form a run-off buffering configuration, creating conditions for mountain oases through seepage and silty overflows (wadi pools, springs and silt deposits).

7. Conclusions

Our investigation of mountain plateau huyul on the Sint Karst Plateau has yielded fundamental insights into their formative processes, sedimentary composition and hydrological characteristics. These vital habitats develop at the intersections of fracture lines in sub-horizontal karst formations at higher elevations in the Al-Hajar Mountains.

Our mineralogical and micropalaeontological analyses confirm that both the basal terra rossa and the overlying silt originates from allochthonous aeolian sources beyond the immediate surroundings (Figure 15). In the limestone environment of the Sint Karst Plateau, amphibole minerals and microfossils of the Ammonia-Elphidium foraminifera association, as well as pyroxene/olivine/chromspinel minerals derived from nearby ophiolites, are the aeolian ‘fingerprint’.

Figure 15

A: Possible primary sources of microfossils and translucent heavy minerals in the sediments of Hayl Ajah. B: Thin section of Triassic Megalodon limestone with agglutinated foraminifer and ooids, Hayl Ajah. C: Thin section of Upper Jurassic–Lower Cretaceous radiolarian limestone, Kubara. Scale bars = 0.5 mm.

The remarkable capacity of huyul to retain water and sediment in a highly eroded mountain landscape apparently derives from a progressive sealing process, caused by silt particles infiltrating and clogging the pore spaces of the underlying material and gradually reducing hydraulic conductivity. This process, analogous to the silting up of modern recharge dams in Oman, creates conditions favourable for temporary water retention (Figure 16) following precipitation events (Al-Maktoumi 2018; Al-Saqri et al. 2016).

Figure 16

Flooding at the mountain plateau hayl Ar-Rwaida (ca. 1100 m a.s.l.; above the Hoti Cave), approximately 25 km due east of Hayl Ajah. Source: Google Maps (Photo: Mohammad Al-Hatali).

Mountain plateau huyul as sediment-trapping, runoff-retaining depressions function as natural ‘flowerpots’ that support ephemeral but vital plant growth and provide meaningful places for both animals and humans inside the Al-Hajar Mountains. Backed by the availability of karst water, mountain plateau huyul have enabled occupation at higher elevations since prehistoric times, as evidenced by the numerous stone artefacts and pottery sherds found at Hayl Ajah and the surrounding huyul (Mateiciucová et al. 2023). Huyul thereupon have played a key role in providing silt for the anthroposols of mountain oases. This is proven by the similar mineralogical composition of sediments from the terraced plots of Amqah and Al-Nazara and those from the huyul above. Moreover, the significance of huyul lies in their thick sedimentary infills, which represent valuable palaeoclimatic and palaeoenvironmental archives (Fuchs & Buerkert 2008; Urban & Buerkert 2009). Establishing absolute chronologies for deposits in Hayl Ajah through OSL and radiocarbon dating will enable us to correlate our data with palaeoclimatic data derived from speleothems in Hoti Cave and the deep sounding in a karst depression near the Maqta oasis (Eastern Al-Hajar). This is particularly significant because the mountain plateau huyul of the three near-horizontal limestone formations have preserved aeolian deposits that no longer exist in steep terrain at similar elevations.

Summing up, we would like to highlight the paradox that the existence of the vital stepping-stones for life-forms inside the mountains was facilitated precisely by the arid palaeoclimate causing: (a) only limited karstification, thus allowing the recharge of perched aquifers within the rock whilst preventing the loss of fine sediments from the rock surface; (b) the release of sediments from the bottom of the Arabian Gulf during marine regression and their transport into the mountainous landscape by wind; and (c) irregular but intense rainfall sufficient to move aeolian sediments into the karst depressions without damaging these retention features. As a result of these climate-driven interferences, huyul have emerged as unique landscape features which, despite arid conditions – or rather because of them – have formed key microhabitats in otherwise bleak and steep mountain terrain.

Additional Files

The additional files for this article can be found as follows:

Notes

[1] Hayl Salman, only 12 km away from Hayl Ajah, is found almost at the top of Jebel Kawr, at ca. 2000 m a.s.l. (Boehme 2022).

[2] Terra rossa refers to intensely red soil occurring on limestone or dolomite bedrock. According to current research, the sediment cannot be viewed solely as a product of limestone dissolution but may mainly have formed with the contribution of external materials (Muhs & Budahn 2009; Sandler et al. 2015).

[3] Suffosion is a destructive process in which fine sediment particles overlying fissured limestone are washed out by rain and surface water. This may lead to a flushing of cover deposits into underground cavities, thereby creating depressions of varying depth on the sediment surface (Gutiérrez et al. 2014).

[4] Since cloudbursts in the surrounding mountains may lead to ponding and horizontal flow inside Hayl Ajah (current towards the ponor and overspill), evaporites might be flushed out of the hayl at relatively short intervals. The repeatedly washed surface of overflowing huyul might thus improve the conditions for herbaceous plants (Al-Maktoumi et al. 2014: 692). Halophytes have not been encountered during botanical surveys at Hayl Ajah (spring 2022 and autumn 2023).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the support for the mountain-archaeological project by His Highness Shaykh Salim bin Mohammed Al Mahrooqi, Minister of Heritage and Tourism of the Sultanate of Oman, and the interest and research perspectives shared by His Excellency Eng. Ibrahim Said Al Kharusi. We thank Sultan Al-Makhmari, Director General for Archaeology and Museums, for his welcoming and effective support. Our team benefited from a visit to the prehistoric mountain site (autumn 2023) by Sultan bin Saif Al-Bakri, Advisor to the Minister, and Ali bin Saeed Al Adawi, Director of the MHT Department in Nizwa. Ali Al-Mahrooqi extended the administrative support to hospitality in Adam, which allowed our team to obtain updated information on aflaj research and Oman’s clay-architectural heritage.

We received ready logistical support from Mr Sulaiman Al-Jabri (MHT Bat) and were effectively assisted in the field by Mr Said Al-Jadidi and Yaqoob Al-Abadi (MHT Nizwa), supervisors of our excavation. In equal measure we received help from Ms Shurooq Saleh Al Sharqi, Ms Sheikha Kh. Al-Rasbi and Mr Mohammed Al-Waili and Mr Khamis Al-Asmi.

We are grateful to our SIPO field team, and to Jennifer Swerida, Eric Fouache, Claude Cosandey, Robert C. Bryant and Aleksandre Prosperini of the Bat Archaeological Project.

We would like to thank Jaroslava Ester Evangelu, Marta Dočkalová, Doris Helbling, Břetislav Svozil, Patrycja Astrid Twardowska, Michal Mazel and Emil Mateiciuc for their invaluable assistance in resolving a critical situation that threatened the realisation of the autumn 2023 season.

Sincere thanks go to Jitka Novotná, Irena Sedláčková, Jana Buřilová and Silvie Čápová from the Czech Geological Survey in Brno and Prague for their support. We would like to thank our colleagues Zuzanna Wygnańska (Polish Academy of Sciences), Knut Bretzke (University of Jena) and Romolo Loreto (University of Naples). For enabling our archaeological research in Oman, we owe gratitude to the Department of Classical Studies and the Dean of the Faculty of Arts, Irena Radová, at Masaryk University (Brno, Czech Republic). For critical reading and comments, we are indebted to Max Engel (Institute of Geography, Heidelberg University), and to Alaisdair Whittle (Cardiff University) for his dependable and careful language corrections over several years.

For a visit to the site Hayl Ajah we would like to thank Sheikh Ahmad Al-Hinai and local elders and leaders of the Sint community. We are very grateful to Mr Luqman Al-Maskari and Kristýna Štorková in Muscat, our landlord Mr Mohanna Saif Al-Hinai, as well as those residents who share their valuable lived knowledge of the mountains with us, either directly at Hayl Ajah or as generous hosts in their homes.

We owe thanks to the reviewers for their constructive comments and useful recommendations that helped to improve the article.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Author contributions

Inna Mateiciucová: Conceptualisation; Investigation; Writing – original draft, review & editing; Visualisation; Funding acquisition. Maximilian Wilding: Conceptualisation; Investigation; Writing – original draft, review & editing; Visualisation; Funding acquisition. Jiří Otava & Miroslav Bubík: Investigation; Formal analysis & Data curation; Writing – review & editing; Visualisation – editing.