Introduction

The land of Southeast Arabia (modern Northern Oman and Eastern United Arab Emirates) is characterised by a contrasting topography comprising the sea, mountains, and deserts. The Al-Hajar Mountains, which originated from the uplift of the Tethys Sea Basin and subsequent land transformations during the Middle and Late Mesozoic, divide the coastal regions into the Sea of Oman and the inner desert of Rub al-Khali (Arabic: The Empty Quarter) (Figure 1). The elevation of the highlands in the Al-Hajar Mountains ranges from 2,000 to 3,000 m above sea level, with the highest peak (3,018 m) occurring in the Jabal Shams near Al-Hamra. There are oases on the highland plateaus of the Jabal Akhdar (Arabic: Green Mountain) area, exemplified by Sayq (Gaube et al. 2012). This area receives approximately 300 mm of maximum annual precipitation from the Indian Monsoon (Shahalam 2001: 1). This water resource sustains oasis sedentism in the lowlands and highlands despite the arid climate. In the lowlands, large-scale oases such as Samad ash-Shan, Al-Moyassar, Mudhaybi, Izki, Rustaq, Nakhal, Nizwa, Bahla, Al-Hamra, and Ibri are typically located along the piedmont of the Al-Hajar Mountains. Thus, the Al-Hajar Mountains are natural water reservoirs for Southeast Arabia.

Figure 1

The land of Southeast Arabia and the location of toponym and archaeological sites mentioned in the text. Basemap: Google Maps applied with QGIS.

The Al-Hajar Mountains are also an obstacle to transportation because of their rugged conditions and high elevation. Therefore, Samail Gap and Wadi Jizzi have been preferred for transportation between oasis settlements since prehistoric periods because of their relatively low gradients. In other parts, small-scale logistics have been practised for trans-mountain routes using donkeys and goats (Dickhoefer and Schlecht 2010).

Considering these environmental settings, conventional studies on land-use history in Southeast Arabia have primarily focused on oases, where groundwater is available and where most of the population lives (e.g. Magee 2014). Similarly, this tendency can be applied to archaeological studies focusing on the Early Bronze Age, notably from the perspectives of sedentism and oasis formation, such as those in Bat, Bisyah, Salut, Al-Ain, and Buraimi (Magee 2014). The current understanding of land-use history in Southeast Arabia is primarily based on studies of oases in the lowlands.

However, despite its potential importance, land use in the Al-Hajar Mountains has remained largely overlooked, except for several highlands and canyons. Investigations in the Sayq Plateau have revealed the intermittent presence of archaeological sites from the Neolithic to Islamic periods (Pullar 1985; Schreiber 2007). The development of the falaj (pl. aflaj) irrigation systems and stepwise agricultural fields indicate human adaptation to rugged mountaintops, at least from the Early Iron Age (Gangler 2008; Gaube et al. 2012). In Sint, archaeological and palaeo-environmental studies suggest human utilisation of the highland basin during the Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene (Mateiciucová et al. 2023). The distribution of archaeological sites in the canyons of Wadi Tiwi (Korn et al. 2004), Wadi Bani Awf (Häser 2000; 2003), Wadi Bani Kharus (Ibrahim and Strachan 2020), Wadi Shab (Tosi and Usai 2003; Usai 2006), and Shiya (Munoz et al. 2017) has been studied; however, land-use history has not yet been fully reconstructed.

Canyons are important routes because of their intermediate nature between the highlands and lowlands. Indeed, archaeological evidence relevant to the mobility has been discovered in some canyons in Southeast Arabia. A study focused on land use in canyons can reveal the alternative style of human adaptation and land use in Southeast Arabia next to oases and mountaintops. It can effectively contribute to a holistic understanding of the various modes of human adaptation to overcome the given arid environmental conditions. Land use is closely related to the human perception of environmental elements, including geomorphology, climate, and physical availability, supported by technology and social conditions.1 Land use history, evinced by the apt utilisation of the canyons’ given topography, refers to long-term human adaptation and alteration to lands, and how humans have reacted to environmental conditions in the mountainous areas of the Arabian Peninsula. The reconstructed landscape is a combination of these factors, particularly in monsoon-affected arid lands.

The study of land use history is particularly important for understanding human-environmental interactions in the interior of Southeast Arabia, primarily based on studies in oases and highlands. Previous archaeological studies have indicated the long-term transformation of human subsistence strategies, outlined as follows: the highly mobile lifestyle in the early Holocene until the end of the Neolithic shifted to seasonal sedentism in the Early Bronze Age Hafit period (ca. 3300–2700 BCE) and more developed sedentism in the Early Bronze Age Umm an-Nar period (ca. 2700–2000 BCE). It returned to the mobile societies interacting with the environmental deterioration in the Middle Bronze Age Wadi Suq period (ca. 2000–1600 BCE) and Late Bronze Age (ca. 1600–1300 BCE), followed by resurrection and continuation of sedentism from the Early Iron Age (ca. 1300–300 BCE) onwards accompanied by the advent of the aflaj system. This view can be supplemented by the study of the land use history of the canyons as intermediate lands where mobile activities have potentially taken large roles.

Based on this thought, we explore how humans utilised the particular geographical land settings of canyons, and the changes in this exploitation. To address this question, we studied Tanuf Canyon (Wadi Tanuf) in the interior of North-Central Oman to understand mobility-based employment. By combining on-site surveys, excavations, and satellite image readings (Kuronuma et al. 2022), a rich amount of archaeological evidence was discovered until January 2024. This paper presents these results and discusses long-term human-environmental interactions and land use in this canyon.

Topographical and Archaeological Settings of Tanuf Canyon

Tanuf Canyon is located on the southern flank of the Al-Hajar Mountains, where many other canyons are situated. Wadi Tanuf is derived from two main tributaries, Wadi Qasheh to the east and Wadi al-Hijri to the west, directly downstream of Jabal Akhdar. The wadi deeply cuts the canyon with an adequate amount of potable groundwater, and creates diverse topography inside the canyon. Typical cliffs are more than 400 m high, with a gradual decrease in the outlets, various gradients of the talus slopes, and occasional small-scale terraces in the lower parts. These topographical conditions provide inclined passes for transmountain routes. This topographic diversity is a promising archaeological resource for understanding the millennial-scale transformation of regional land use.

Earlier, archaeologists recognised Tanuf Canyon by its rock art panels. Rock art was first reported in the 1970s (Clarke 1975; Preston 1976; Jäckli 1981), and a few surveys have been conducted in the last two decades (Fossati 2019; Lockwood 2014a). However, the exact location of the recently discovered rock art sites have not been disclosed, except for two localities (Fossati 2019). Additionally, Falaj Tanuf is renowned as a practical example of a traditional water-resource management system in Southeast Arabia (Costa 1983).

Other archaeological investigations, except for one Palaeolithic-focused study (Meredith-Williams et al. 2022), were conducted outside the canyon, particularly around the modern town of Tanuf. Two Umm an-Nar towers and two Hafit cemeteries were mentioned by several scholars (de Cardi et al. 1976; Costa 1983; Schreiber 2007), although the long-term human activities inside the canyon except for rock arts had not been fully understood until the authors’ archaeological investigations starting in 2017.

Framework of Archaeological Investigations and the Classification of the Topography

Investigation workflow

The method of archaeological investigation in the canyon of Wadi Tanuf combined excavations and full-coverage-oriented surveys (Kuronuma et al. 2022). The general flow can be divided into four phases, the first of which involves reading pre-fieldwork satellite imagery. Accessibility to archaeological sites is limited because of the rugged local terrain system. Prior to the field investigations, we geolocated possible sites using a time-lapse function to minimise the effects of shades into the canyons. The second phase involved a visit to the identified site candidates, during which new sites were also detected. During this phase, the locations of the archaeological features were recorded onsite. In the third phase, we conducted excavations to determine the date and validate the on-site evaluation. The final phase was the post-fieldwork process which involved data compilation and modification, including database addition and refinement.

Research areas and classification of topography

We conducted archaeological surveys in two selected areas of Tanuf Canyon (Figure 2). Area 1 lies between the outlet and first curve. This area is characterised by a wider canyon. The local topography comprises a combination of terraces, lower steep talus slopes, higher gentle talus slopes, higher steep talus slopes, and a high cliff, particularly on the right (western) bank of Wadi Tanuf. This condition implies that there is a space for human activities between the wadi bed and the cliffs on the right bank. The left (eastern) bank is directly connected to the lower cliff; however, there are relatively gentle high talus slopes.

Figure 2

Satellite imagery of the Tanuf Canyon and the investigated areas. A) Location of Areas 1 and 2. B) Distribution of archaeological sites in Area 1. The numbers with white dots in the figure indicate the sites’ WTN name. C) Distribution of archaeological sites in Area 2. The location of the sites is indicated as the cases in B). The coordinate system is UTM40Q. All background images: AW3D Ortho Imagery © DigitalGlobe, Inc., NTT Data Corporation and Google Maps applied with QGIS. Contours are applied to the ASTER GDEM model with QGIS. White lines indicate the contours in the 100 m interval, while bold purple lines indicate those in the 1000 m interval. The background is ASTER-VA image (ASTER-VA image courtesy NASA/METI/AIST/Japan Spacesystems, and US/Japan ASTER Science Team). See https://gdemdl.aster.jspacesystems.or.jp/index_en.html for details.

Area 2 is located between the confluence of Wadi Qasheh and Wadi al-Hijri after a large curve from the confluence. The canyon is narrower and the cliffs are much higher than that of Area 1; thus, it is more topographically limited. This cliff stands directly on the right bank of Wadi Tanuf. There are a few small terraces on the left bank, with high cliffs behind them. This topographical situation in Area 2 results in a smaller area of land available for use as compared to Area 1. However, the intermediate area has yet to be investigated.

To analyse the long-term history of land use in Wadi Tanuf, we classified the topography in accordance with three factors: surface gradient, accessibility, and visibility from the wadi bed. These factors are essential when considering the archaeological landscape within a rugged canyon with limited land availability. The classification of the local topography was based on field observations and a digital elevation model (ASTER GDEM within 1-arc-second [ca. 30 m] posting intervals). The presence of archaeological sites may affect this classification. Therefore, the topography was defined and classified posterior to several fieldwork seasons. As a result, the topographical classes comprised I, Wadi bed; II, Lower cliff; III, Terrace; IV, Lower steep talus slope; V, Higher gentle talus slope; VI, Higher steep talus slope; VII, Isolated plateau; VIII, High cliff; and IX, Mountain plateau (Figures 3, 4, and 5).

Figure 3

Classified topography in Area 1. Roman numerals indicate the topographical classes defined in the main text, whose supposed boundaries are indicated by the white lines. The red arrow indicates the flowing direction of Wadi Tanuf. The green broken lines indicate the location of the sections presented in Figure 5. All background images: AW3D Ortho Imagery © DigitalGlobe, Inc., NTT Data Corporation and Google Maps applied with QGIS.

Figure 4

Classified topography in Area 2. Roman numerals indicate the topographical classes defined in the main text, whose supposed boundaries are indicated by the white lines. The red arrow indicates the flowing direction of Wadi Tanuf. The green broken lines indicate the location of the sections presented in Figure 5. All background images: AW3D Ortho Imagery © DigitalGlobe, Inc., NTT Data Corporation and Google Maps applied with QGIS.

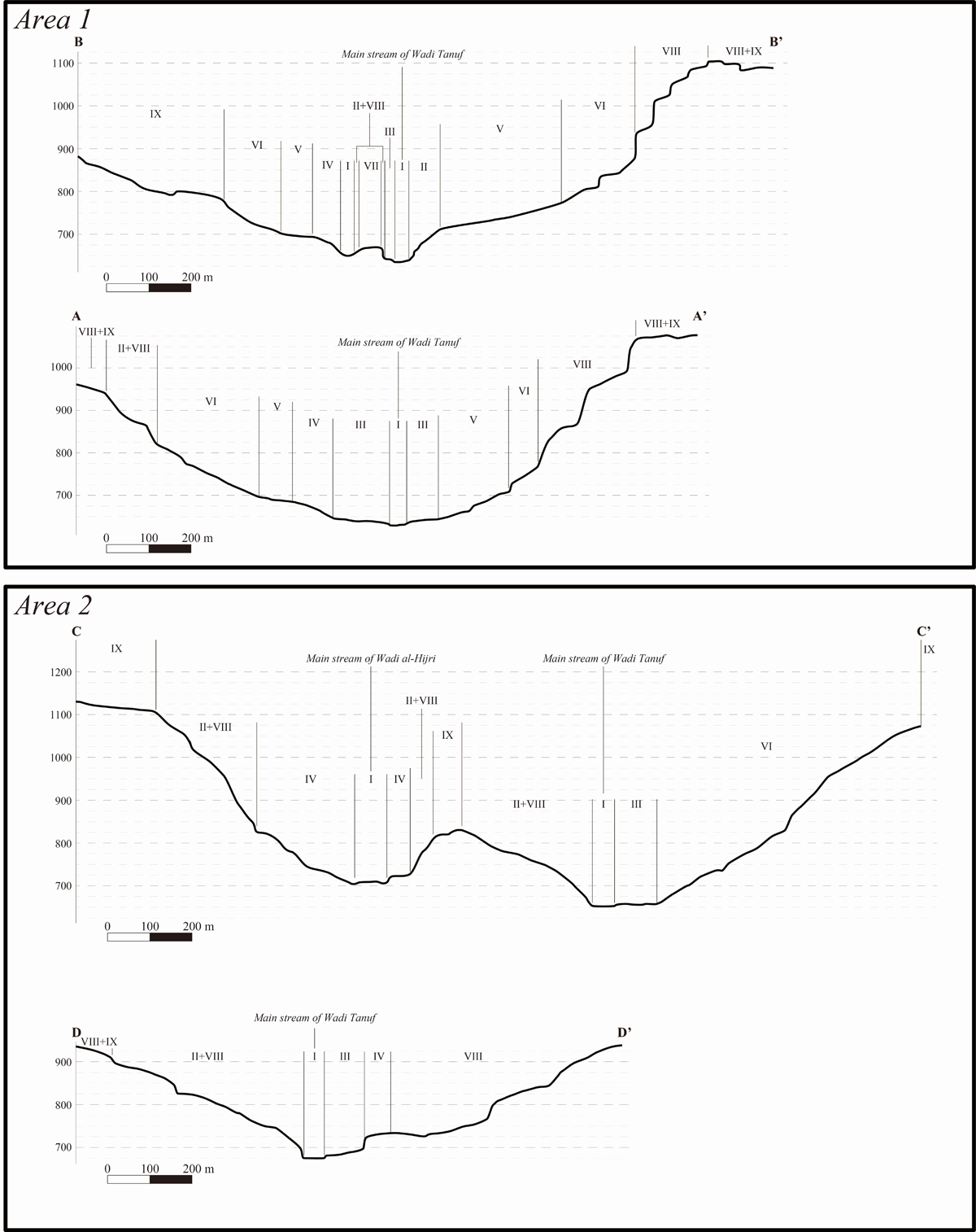

Figure 5

The schematic sections of Tanuf Canyon in Areas 1 and 2 based on ASTER GDEM. Roman numerals indicate the topographical class defined in the main text. The location of the sections is indicated in Figures 3 and 4 in broken green line.

Results

Overview of findings and land use by areas

In total, 21 sites were identified in Tanuf Canyon. Of these, 15 sites (WTN01 (Mugharat al-Kahf), WTN02, WTN05, WTN07, WTN08, WTN12, WTN13, WTN14, WTN15, WTN16, WTN18, WTN19, WTN22, WTN23, and WTN24) are situated in Area 1 and six (WTN09, WTN10, WTN11, WTN17, WTN20, and WTN21) are in Area 2. The chronological range of these sites varies from the Early Holocene to the Islamic period (Table 1).

Table 1

Summary of the discovered sites in each period at the defined topographical classes.

| WTN | AREA | TOPOGRAPHY | TOPOGRAPHY TYPE | EARLY HOLOCENE BEFORE 3300 BCE | HAFIT 3300–2700 BCE | UMM AN-NAR 2700–2000 BCE | WADI SUQ 2000–1600 BCE | LATE BRONZE AGE 1600–1300 BCE | EARLY IRON AGE 1300–300 BCE | LATE IRON AGE 300 BCE – 630 CE | ISLAMIC 630 CE– |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | 1 | VIII | High Cliff | – | X | X | X | X? | X | X? | X |

| 02 | 1 | III | Terrace | – | – | – | – | – | X | – | X |

| 05 | 1 | VII | Isolated Plateau | – | X | X? | – | – | – | – | X |

| 07 | 1 | III | Terrace | – | – | – | X | – | X | – | X |

| 08 | 1 | IV + V | Lower Steep Talus Slope + Higher Gentle Talus Slope | – | X | – | X? | – | X | – | X |

| 09 | 2 | II | Low Cliff | X? | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 10 | 2 | I | Wadi Bed | – | – | – | – | – | X | X? | X |

| 11 | 2 | III | Terrace | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | X |

| 12 | 1 | II | Low Cliff | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | X |

| 13 | 1 | IV + V | Lower Steep Talus Slope + Higher Gentle Talus Slope | – | X | – | X | – | X | – | X |

| 14 | 1 | V | Higher Gentle Talus Slope | – | – | – | X | – | X | – | – |

| 15 | 1 | V | Higher Gentle Talus Slope | – | X | – | – | – | X | – | X |

| 16 | 1 | III | Terrace | – | X | – | – | – | – | X? | X |

| 17 | 2 | III | Terrace | – | X | – | – | – | X | – | – |

| 18 | 1 | VI | Higher Steep Talus Slope | – | X | – | – | – | X? | X? | – |

| 19 | 1 | VI | Higher Steep Talus Slope | – | X | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 20 | 2 | III | Terrace | – | – | – | – | – | X? | – | – |

| 21 | 2 | I | Wadi Bed | X? | X | X | – | – | X | X? | X |

| 22 | 1 | IX | Mountain Plateau | – | X | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 23 | 1 | I | Wadi Bed | – | – | – | X | – | X | – | X |

| 24 | 1 | VI | Higher Steep Talus Slope | – | X | – | – | – | – | – | – |

Cemeteries, living spaces, cave shelters, rock art panels, fortifications, and facilities for pastoralism are found in Areas 1 and 2. In Area 1, past human activity was detected on all topographical classes (Table 2). The terrain with the most varied activities was the higher gentle talus slope (Topography V), where cemeteries, living spaces, pastoral traces, and rock art panels were found at four sites (WTN08, WTN13, WTN14, and WTN15). Hafit, Wadi Suq, Early Iron Age, and Islamic remains were confirmed. This archaeological richness indicates that the higher gentle talus slope in Area 1 was the principal location of activity throughout the ages. In contrast, we found only one type of activity in the wadi bed (Topography I) (WTN21), lower steep talus slope (Topography IV) (WTN08 and WTN13), and mountain plateau (Topography IX) (WTN23). All these types of terrain indicate limited availability. We confirmed two types of activities in the remaining terrain using various combinations of activities.

Table 2

Summary of site types and defined topographical classes in Area 1.

| WTN | AREA | TOPOGRAPHY | TOPOGRAPHY TYPE | CEMETERY | LIVING PLACE | CAVE USE | ROCK-ART | FORTIFICATION | PASTORAL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | 1 | VIII | High Cliff | – | – | X | – | – | – |

| 02 | 1 | III | Terrace | X | X | – | – | – | – |

| 05 | 1 | VII | Isolated Plateau | X | – | – | – | X | – |

| 07 | 1 | III | Terrace | X | X | – | – | – | – |

| 08 | 1 | IV + V | Lower Steep Talus Slope + Higher Gentle Talus Slope | X | – | – | – | – | X |

| 12 | 1 | II | Low Cliff | – | – | X | X | – | – |

| 13 | 1 | IV + V | Lower Steep Talus Slope + Higher Gentle Talus Slope | X | – | – | X | – | – |

| 14 | 1 | V | Higher Gentle Talus Slope | X | – | – | – | – | – |

| 15 | 1 | V | Higher Gentle Talus Slope | X | X | – | – | – | – |

| 16 | 1 | III | Terrace | X | – | – | – | – | – |

| 18 | 1 | VI | Higher Steep Talus Slope | X | – | – | – | – | – |

| 19 | 1 | VI | Higher Steep Talus Slope | X | X? | – | – | – | – |

| 22 | 1 | IX | Mountain Plateau | X | – | – | – | – | – |

| 23 | 1 | I | Wadi Bed | – | – | – | X | – | – |

| 24 | 1 | VI | Higher Steep Talus Slope | X | – | – | – | – | – |

In Area 2, the terrains with archaeological sites were limited to the wadi bed (Topography I), lower cliff (Topography II), and terrace (Topography III) (Table 3). Activities were limited due to the low availability and accessibility of these terrains. The canyon in Area 2 is primarily surrounded by precipices more than 60–70 m high. Usable land is limited to the terraces where activities from the Neolithic to the Islamic periods have been confirmed. The wadi bed has two sites (WTN10 and WTN21) with rock art dated from the Bronze Age to the Islamic period. The lower cliff is characterised by a cave (WTN09), where unspecified lithics were collected from an excavation by the Australian team (Meredith-Williams et al. 2022). These terraces are occupied by Iron Age and Islamic cemeteries. A detailed summary is provided below.

Wadi bed

The rock art sites (WTN10, WTN21, and WTN23) were confirmed on the panel along the wadi bed. No other types of sites were identified. Some pecked figures were covered with soil in WTN10, indicating the damage caused by flash floods (Figure 6A). Rock art is assumed to be from the Bronze Age to the Islamic period based on three aspects. The first and most important aspect is the chronological development of the motifs. For example, several abstract motifs, such as ‘sun-marks’, were confirmed in WTN21. Such abstract motifs date back to before the 2nd millennium BCE. Moreover, there is a pecked petroglyph of the Zebu bovine in WTN21 (Fossati 2019). In the archaeological context of Southeast Arabia, Zebu bovines living in South Asia appear on the Umm an-Nar pottery or contemporary stamp seals (Frenez 2018). Camels and horse riders dating back to the Iron Age and Islamic period, also commonly appeared at these sites.

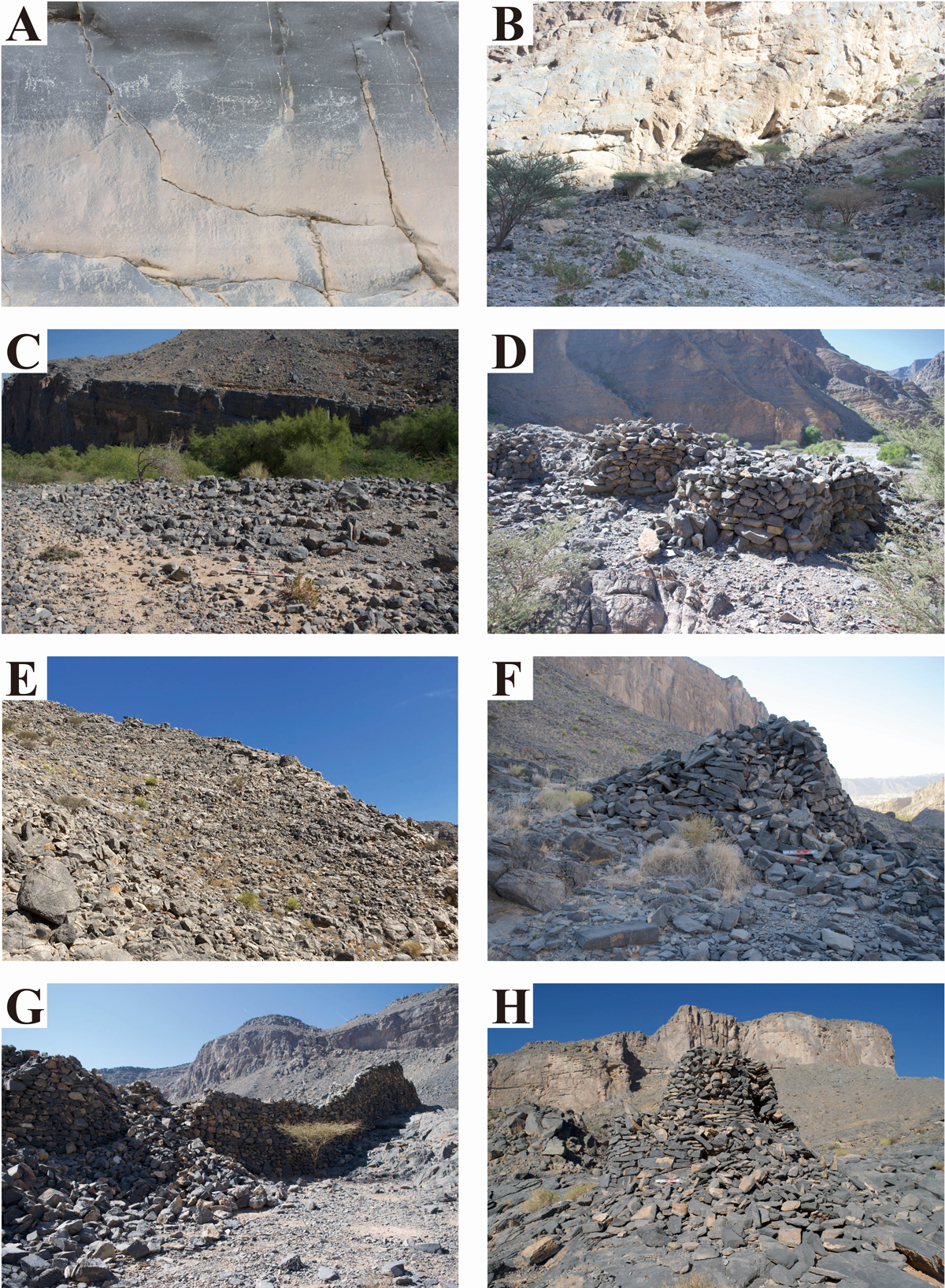

Figure 6

A) Rock art panels of WTN10 beside the Wadi Bed. B) Cave of WTN09 on the Low Cliff. C) Cemetery of WTN16 on the Terrace. D) Cemetery of WTN17 on the Terrace. E) Cemetery of WTN24 on the Higher Steep Talus Slope. F) Cemetery of WTN18 on the Higher Gentle Talus Slope. G) Islamic fort of WTN05 on the Isolated Plateau. H) Cemetery of WTN22 on the Mountain Plateau.

The second aspect is the overlap between petroglyphs. We observed nearly effaced petroglyphs in WTN21 and WTN23. The third aspect is the relative position of petroglyphs. Many rock art pieces were located more than 4 m above the wadi bed in WTN21 and WTN23. Such a position indicates the past position of the wadi bed, as Fossati has mentioned (Fossati 2019). A general trend in the chronological differences can be observed in their vertical positions, with older, supposed Bronze Age examples found in higher places and younger Iron Age or Islamic examples in lower places.

These aspects support the wide chronological range of intermittent visits to the panel on the wadi bed for rock art purposes. Rock art sites embody millennial-scale canyon utilisation by past people. In summary, only rock art sites are located in and around the wadi bed. Other sites may have been present in ancient times but were washed out by recurrent flood.

Low cliff

Among the caves on the lower cliff, two sites, WTN09 and WTN12, were archaeologically identified. Our team registered WTN09 in December 2018 (Figure 6B), and the Australian team opened one or two sondages from which they recovered prehistoric lithics (Meredith-Williams et al. 2022).2 Details of the lithics are yet to be published. However, they likely indicate cave occupation during the Early Holocene. The mouth of WTN12 opens near the outlet of Wadi Tanuf at a slightly higher location than the terrace. An undated, stone-built slope provides access to the cave interior. Although nothing is left in the cave, this slope indicates past activity at WTN12. Furthermore, a few rock art pieces with horse-rider motifs were located near the cave.

The caves are occupied by low cliffs, along with other minor activities. Panels with petroglyphs indicate frequent transportation inside the canyon in the form of corridors. Additionally, Fossati mentioned a cave with rock art, including rare painted cases on ceilings (Fossati 2019), although we have yet to detect them. This evidence supports the existence of past sojourns in these caves.

Terrace

Flat surfaces (terraces) beside Wadi Tanuf are a topographical class with various human activities. WTN02 and WTN07 in Area 1 were on a large terrace (ca. 250 m long and 75 m wide) with archaeological evidence. We confirmed the sites of WTN02 (Early Iron Age settlement and Islamic cemetery) (Kuronuma et al. 2023; Miki et al. 2024) and WTN07 (probable Early Iron Age settlement with sole solid structures in Tanuf Canyon, probable Wadi Suq cemetery for a collective tomb, and an Islamic cemetery with more than 120 graves) (Kuronuma et al. 2024). This chronologically diversified evidence embodies the long-term transformation of terrace activities between non-mortuary and mortuary purposes. Islamic and possible Early Bronze cemeteries were also confirmed on the terrace (ca. 115 m long and 20 m wide) with WTN16 to the north, indicating long-term recurrent tomb building (Figure 6C).

In Area 2, the terraces are on higher ground and host three cemeteries (WTN11, WTN17, and WTN20). WTN11 is an Islamic cemetery with two distributional areas of tombs separated by a talus slope directly facing the wadi bed. Some tombs built near the edge of the terrace are currently being destroyed by deflation. Despite its large size (ca. 260 m in length and 50 m in width), the terrace was mostly blank. Islamic cemeteries have been established in the easternmost region. WTN17 is located on a different terrace upstream of WTN11. This terrace was occupied by Early Iron Age free-standing tombs with superstructures (so-called Hut-tombs) (Yule 2001) which were previously introduced as Hafit cairns (Lockwood 2014b). Some tombs are connected to form mortuary complexes (Figure 6D). Each tomb has common structural characteristics, indicating a possible short-term cemetery formation. We confirmed that several natural rocks provided space for the rock shelter tombs. The improvised conversion of natural rocks is also a characteristic of canyons that have limited available space. Similar cases (WTN20) were confirmed in the lower terrace to the north of WTN17, representing the frequent substitution of natural monuments in Tanuf Canyon.

Lower steep talus slope

This topographical class is highly visible from the wadi bed. Despite its instability, cemeteries were found on this class of terrain in Area 1. Eight Hafit tombs belonging to WTN08 spread to the higher gentle talus slope from this terrain. Interestingly, the tombs form four groups on each slope ridge, separated by gullies. We also recorded an additional tomb belonging to WTN13 on the terrain. Each group comprises one to three Hafit tombs, depending on the ground conditions. The Hafit landscape of this terrain was likely characterised by the stepwise allocation of cairns along Wadi Tanuf. The WTN13 Hafit tomb was secondarily attached to a possible Iron Age tomb, indicating the long-term continuity of land use.

Higher gentle talus slope

The higher gentle talus slope confirmed in Area 1 was the most utilised terrain in Wadi Tanuf, with four sites (WTN08, WTN13, WTN14, and WTN15). At WTN08, three Hafit tombs were built on this terrain as a continuation of the lower steep talus slope. The cemetery in the Early Iron Age with Hut-tombs and the rock-shelter tomb complex is similar to that of the WTN17. In addition, we confirmed that a few undated stone enclosures were built by diverting natural rock. These enclosures were probably intended for goat keeping, implying pastoralism in this terrain. At WTN15, an undated occupational structure was observed.

WTN13 and WTN14 were among the largest cemeteries before the arrival of Islam. After its initial opening as a Hafit cemetery, probable Wadi Suq tombs, Iron Age rock shelters, and rock-attached tombs were established on the terrain. Because smaller individual burials were reintroduced during the Wadi Suq period, establishing the Wadi Suq cemetery in a relatively wide and gentle place on the higher talus slope was a reasonable selection. Other places that are affordable for many individual tombs are limited to Tanuf Canyon.

This talus slope is clearly visible from the cave hollowed on the high cliff, where a contemporary cave (WTN01) is present. The location of WTN13 and WTN14 could have been selected to establish a place where they could have mutual links with the other contemporary sites from the visibility and landscape perspectives.

WTN13 and WTN14 also include a higher part, where large natural rocks are dispersed. Such rocks were converted into tombs, as observed in WTN17 and WTN20. In WTN13, natural rock was used as two rock art panels with horse or camel-rider motifs after the Iron Age or Islamic period (Fossati 2019). This indicates activities during the Islamic period after the cessation of the cemetery. This demonstrates the long-term importance of the higher gentle talus slope in WTN13 and WTN14.

Higher steep talus slope

Archaeological evidence in this topographical class has been limitedly confirmed. On the right bank of Area 1, between the higher gentle talus slope and the high cliff, we confirmed the spread of Wadi Suq and Early Iron Age pottery, which flowed down from the cave WTN01 (Mugharat al-Kahf), opening on the high cliff. We also confirmed the presence of WTN24 with at least three Hafit tombs and one Early Iron Age tomb on the terrain (Figure 6E). The tombs were built on either extremely steep slopes or minimal flat spaces with low accessibility, indicating the selection of rugged terrains for cemeteries. The visibility of the wadi bed is excellent and may be suitable for building monumental tombs as landmarks. Therefore, the terrain was used appropriately.

On the left bank, we confirmed three Hafit cairns: one undated (possibly Later Prehistoric) tomb between the edge of the low cliff and the middle of the higher steep talus slope in WTN18 (Figure 6F) and two Hafit cairns in WTN19 at the same location. The archaeological landscapes in WTN18 and WTN19 during the Hafit period can be considered as one entity on the left bank. Additionally, there is a possible recent non-mortuary structure in the WTN19. This terrain is closely associated with trans-mountain transportation and other related activities.

Isolated plateau

We only recorded the Bronze Age and Islamic site of WTN05 on this topographical class in Area 1. The most ancient features are the three Hafit cairns built near the edge of the cliff beside the main stream of Wadi Tanuf. The two tombs were in ruins and their stones were recycled for Islamic fortification. We also confirmed a badly destroyed Early Bronze Age tomb, which could have been dated to the Umm an-Nar period.

The most well-preserved feature is the Islamic fortification (Figure 6G), which is confirmed by the presence of Islamic pottery on the surface. The full extent of the plateau was developed for protective purposes, and the only accessible part, the route to the mountaintop via WTN24, was blocked by the main massive fortification wall crossing the entire plateau transect. We confirmed that relatively stable and flat areas provided room for several buildings, as evidenced by the preserved foundations.

On the other part of the plateau, the ridge is equipped with 18 walls which are distributed throughout the ridge. These walls are intentionally unconnected, and such gaps may serve defensive purposes related to merlons, allowing for archery or stone-throwing while hiding. This structural distribution can cause defenders to conduct attacks while concealing themselves. It is also possible that the broken Hafit cairn was converted into a de facto defensive facility. This topography is tactically the best place to install fortifications for protective purposes in Tanuf Canyon.

High cliff

The high cliff is characterised by caves. We found an archaeological site in the Mugharat al-Kahf Cave (WTN01). The cave is situated slightly above the higher steep talus slope with a triangular entrance that is visible from the wadi bed. We confirmed intermittent cave occupation from the Early Bronze Age to recent times. On-surface artefact collection and excavations revealed extensive occupation during the Wadi Suq period (Miki et al. 2020; 2022; 2024). The excavated artefacts include carbonised date seeds, animal bones, and pottery. Several ash layers and hearths were also detected. The radiocarbon dates support the period of these artefacts.

Interestingly, radiometric dates corresponding to the Wadi Suq period were measured from the excavated carbonised date stones, indicating their importation to the cave. The cave was also occupied during the Early Iron Age. We followed Islamic remains, such as goat pastoralism, which included recently built walls.

The cave intermittently functioned as a natural shelter on the way to transportation, which was motivated by several factors, such as pastoral nomadism, non-pastoral transportation, or their combination. Caves are a characteristic natural feature of canyons, and many caves have their openings on high cliffs. Some caves are situated on terrains without accessibility, whereas others are reachable but have not been surveyed. In such cases, a high potential exists for further occupation.

Mountain plateau

We identified an isolated Hafit cemetery, WTN22, with one tomb at the edge of a mountain plateau on the right bank of Wadi Tanuf (Figure 6H). The tomb stands between the edge of a high cliff and natural cracks, which are the chimney mouth of a cave below. This cemetery is highly visible, indicating the selection of this terrain according to mortuary regulations related to monumentality.

Discussions

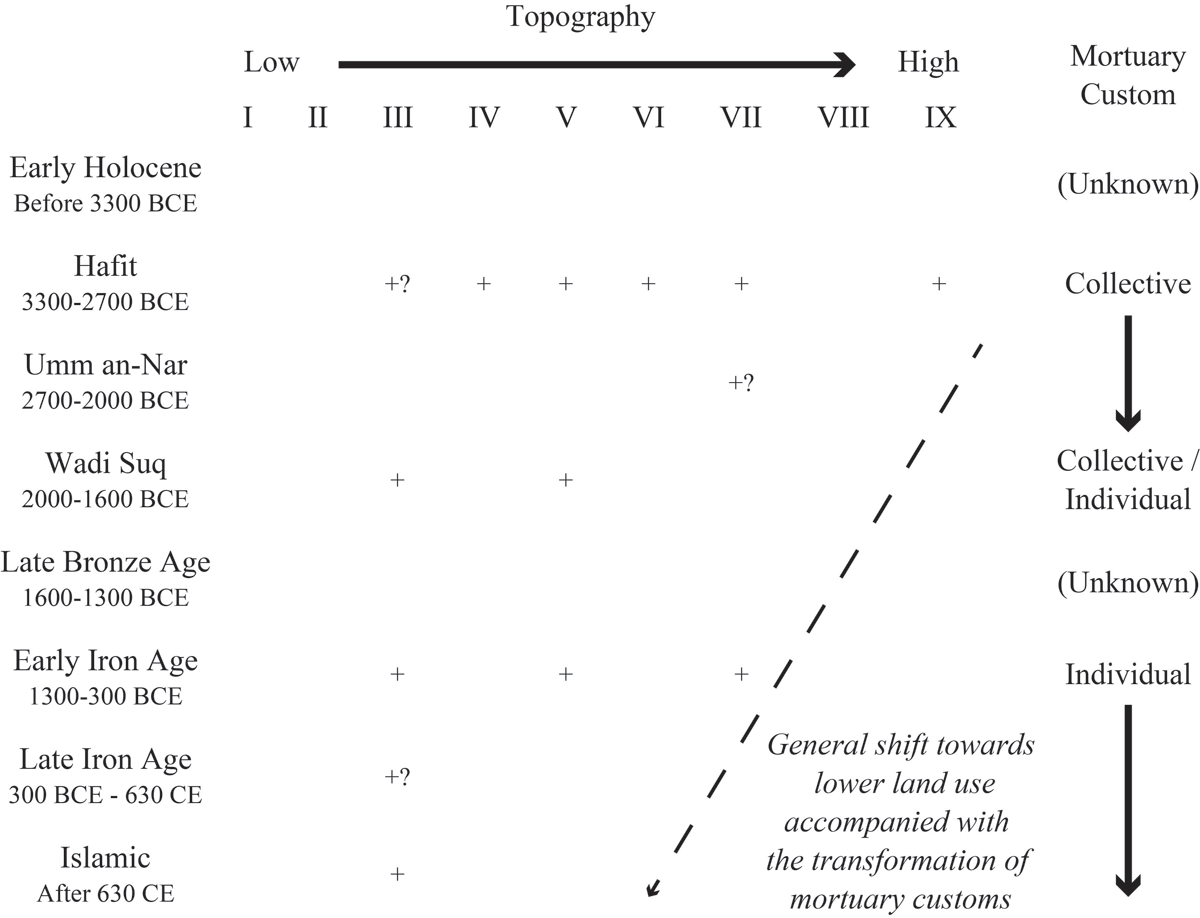

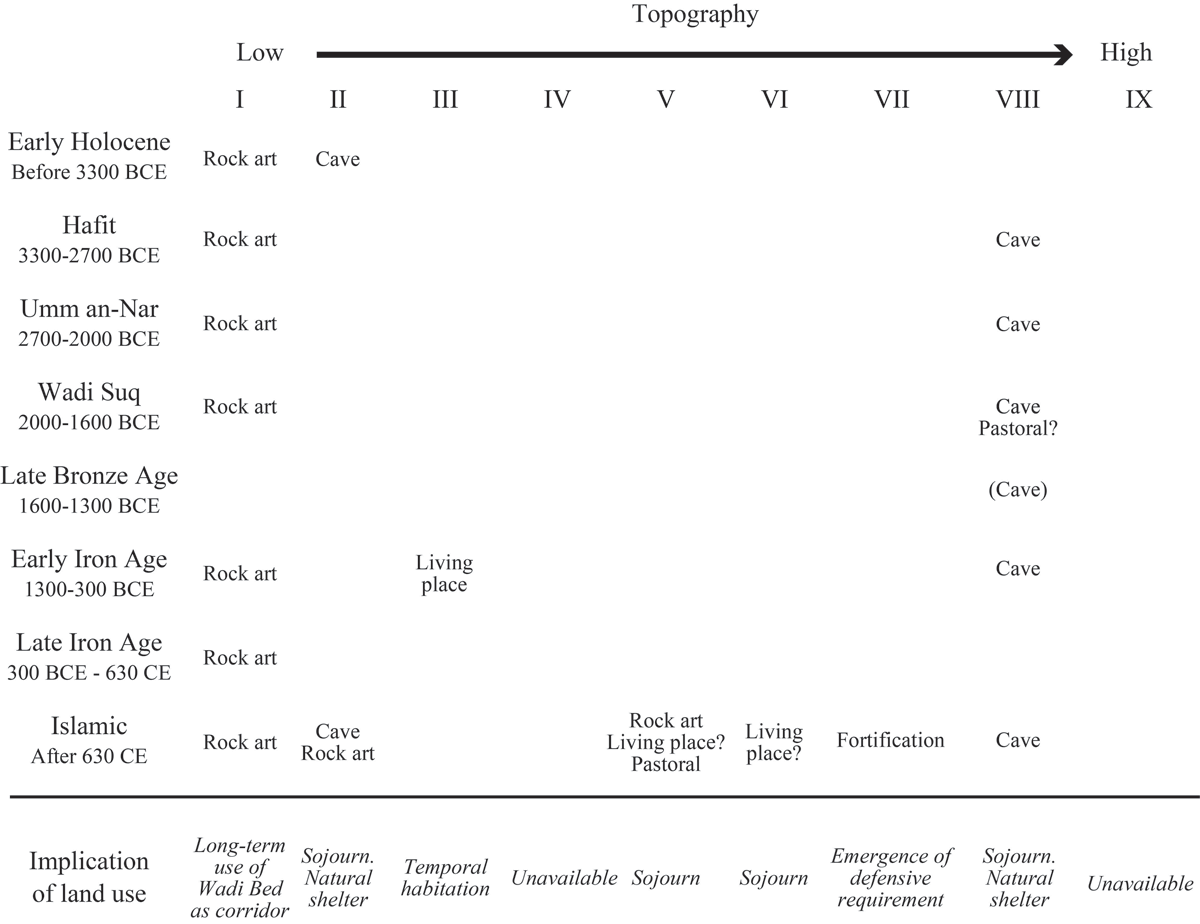

Several years of archaeological investigations have confirmed the continuous and intermittent deployment of archaeological features on various terrains, and land use in the limited available terrains has transformed over time, even within the same topography. This transformation matched cultural demands with usable land conditions. The background of topographical selection can be summarised as follows (Figures 7 and 8; Table 4).

Figure 7

Diachronic shift of locations for cemeteries in Areas 1 and 2. The letter ‘+’ indicates the presence of archaeological evidence.

Figure 8

Diachronic overview of land use for non-mortuary purposes in Areas 1 and 2.

Table 4

Summary of land use transformation in the millennial scale.

| TOPOGRAPHY | I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII | VIII | IX | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activity type | Mortuary | Non-Mortuary | Mortuary | Non-Mortuary | Mortuary | Non-Mortuary | Mortuary | Non-Mortuary | Mortuary | Non-Mortuary | Mortuary | Non-Mortuary | Mortuary | Non-Mortuary | Mortuary | Non-Mortuary | Mortuary | Non-Mortuary |

| Early Holocene Before 3300 BCE | Rock art | Cave | ||||||||||||||||

| Hafit 3300–2700 BCE | Rock art | Collective tombs? | Collective tombs | Collective tombs | Collective tombs | Collective tombs | Cave | Collective tombs | ||||||||||

| Umm an-Nar 2700–2000 BCE | Rock art | Collective tombs? | Cave | |||||||||||||||

| Wadi Suq 2000–1600 BCE | Rock art | Collective tombs | Individual tombs | Cave Pastoral? | ||||||||||||||

| Late Bronze Age 1600–1300 BCE | (Cave) | |||||||||||||||||

| Early Iron Age 1300–300 BCE | Rock art | Individual tombs | Living place | Individual tombs | Cave | |||||||||||||

| Late Iron Age 300 BCE-630 CE | Rock art | Individual tombs? | ||||||||||||||||

| Islamic After 630 CE | Rock art | Cave Rock art | Individual tombs | Rock art Living place? Pastoral facility | Living place? | Fortification | Cave | |||||||||||

For cemeteries

Our results demonstrated the shift of the land for tombs accompanied with long-term transformation of mortuary customs. The cemetery location generally shifted from a highly visible, unstable, and narrow place to a less visible, stable, and wide place.

The structures and spatial distribution patterns of tombs in Southeast Arabia have changed over the past millennia. From a diachronic perspective, people in the Hafit period preferred to build Hafit tombs at higher elevations than the surrounding ground level, ensuring adequate visibility for territorial indications (Al-Jahwari 2008; 2013; Deadman 2012; 2017). This locational tendency is also applicable to Tanuf Canyon. Terrains with high visibility, represented by the lower steep talus slope (Topography IV), higher gentle talus slope (Topography V), higher steep talus slope (Topography VI), and mountain plateau (Topography IX), were used for the Hafit tombs. Such higher places in and around the canyon fulfilled the requirements for visibility. Cultural needs of this visibility appear to be related to mobility rather than to territorial markers in Tanuf Canyon, as observed in the cases of WTN18 and WTN19, located beside the trails to Jabal Akhdar. Cairns WTN05, WTN08, WTN13, WTN15, and WTN16 possibly functioned as guideposts for the wadi bed.

The lack of the Umm an-Nar tombs, except for one possible example in WTN05 on an isolated plateau (Topography VII), contributes minimally to discussing land use for mortuary purposes during this period. Temporal cave occupations and rock art, albeit with a lack of permanent settlement, indicate the less sedentary nature of activities at Tanuf Canyon during the Umm an-Nar period. However, the Umm an-Nar tomb inside the canyon is not exceptional, as seen in the possible example at Al-Bir (Häser 2003). Perhaps the mortuary activities in Tanuf Canyon were related to mobility.

The locations of the cemeteries appear to have been highly affected by the reintroduction of individual tombs during the Wadi Suq period. A Wadi Suq cemetery with individual tombs requires land that fulfils the size and relative flatness requirements, enabling the clustered spread of dozens of freestanding tombs. This explains why the Wadi Suq cemeteries are spread on a higher gentle talus slope (Topography V). Nevertheless, such places are atypical of the Wadi Suq cemetery. Individual Wadi Suq tombs are usually built on lower flat alluvial terraces, unless they are secondary tombs or a few primary cemeteries (Kuronuma 2023). Their location on the higher gentle talus slope is likely due to the limited land that fulfils the requirements inside the canyon. Perhaps, visibility from the contemporary cave of Mugharat al-Kahf was also important during the Wadi Suq period.

Moreover, we may be able to consider the different cultural backgrounds of mortuary practices for a possible Wadi Suq collective tomb in WTN07 on the terrace (Topography III) due to its separated location from the individual tombs on the higher gentle talus slope (Topography V). For such cultural backgrounds, we can presume the finer chronological difference, as well as other reasons such as societal differences or the monumentality.

Early Iron Age mortuary practices intermingled the return to the locational selection of these Hafit tombs and the emergence of new clustering-attached tombs. The reintroduction of tombs (Hut-tombs) on ridges has followed a similar trend in other parts of Southeast Arabia (Yule 2001). In addition, the clustering of attached tombs requires a specific size and flatness of the land, as observed in individual Wadi Suq tombs. However, considering the clustering of tombs around natural rocks, land with numerous natural rocks was effectively substituted for cemeteries. This adaptation was unique to this period.

The reason why terraces were selected as mortuary places during the Islamic period is likely to guarantee a flat and expansive space that fulfils the strict regulation for building tombs in the same orientation as the qibla, as observed in WTN07 (cf. Petersen 2013). However, this strictness is only occasionally applicable, as in WTN11, in which several long axial orientations are confirmed. These tombs were distributed in the deeper parts of the terrace at WTN07 and WTN11. The reason for the selection of this location was not specified. However, their location may be related to a reasonable selection of land for establishing Islamic tombs based on land conditions.

For occupations including caves as shelters

The canyon is characterised by a scarcity of evidence of habitational activities because of the limited land availability for building permanent structures (Figure 8). The terrace where WTN02 and WTN07 are situated is exceptional evidence of permanent habitational structures, with another possible example in WTN15 on a slope. Therefore, Tanuf Canyon was not permanently occupied except during the Early Iron Age. This paucity is the opposite of the cave occupation of natural shelters. Intermittent occupations in Mugharat al-Kahf Cave are the best examples. These shelters were probably related to the transportation across the Al-Hajar Mountains via canyons. Considering this situation, sojourn in caves is the best choice for every period. Such convenient usage also fits mobile activities rather than sedentary ones.

For rock art panels

These mobile aspects are also related to rock art. Rock art locations were close to the wadi bed (Topography I), which should have been the main route on the millennial scale. The panels standing out from the route on the wadi bed were landmarks for travellers, indicating minor but specific-scale pedestrian routes inside the canyon. The recurrent overwriting of rock art in WTN21 and WTN23 supported this view. Rock art in caves (Fossati 2019) can be considered similarly. Rock art reflects long-term activities inside canyons and the constant role of the wadi bed.

For defence

The fortification of the isolated plateau (Topography VII) presents an interesting conversion of land from cemeteries to protective facilities. The selection of this topographical class for fortification during the Islamic period is the most reasonable in Tanuf Canyon. The fortification of the isolated plateau indicates the emergence of the need for defensive facilities in strategically effective places. In Oman, some prehistoric and historic forts are isolated from the nearby oases (Yule 2019). As a similar example from different periods, a Late Iron Age fort with walls and structures was built on a plateau in Wadi Bani Khalid (Loreto 2020). The selection of an isolated high location inside the canyon effectively accomplished the purpose of the forts by providing adequate protection.

For pastoral activities

Some facilities on the slope indicate frequent pastoralism within the canyon, and such evidence is related to the mountain pastoralism in the Al-Hajar Mountains. Facilities related to pastoral activities were often found on the higher gentle talus slopes (Topography V). The long-term continuation of pastoralism inside the canyon can also be inferred from the findings of Mugharat al-Kahf, from where goat dung was acquired (Miki et al. 2020; 2022). The survey and excavation results indicate the possible long-term presence of goats and humans in Tanuf Canyon, suggesting pastoral nomadic land utilisation. The presence of several groups of goats has been confirmed in modern times inside the canyon, indicating the continued pastoralism in modern times. Modern mountain pastoralism has been examined through the ethnographical study of the Showai’ya people (Wilkinson 1977).

In summary, the long-term land use inside Tanuf Canyon is connected to various pieces of evidence related to transportation and mobile activities (Table 4). The land inside the canyon was not regularly occupied for a long time. However, the terrain for particular activities shifted through time, undoubtedly reflecting the needs of the people at the time. Therefore, the canyon provided the best solution for land use related to mobile activities throughout the study period.

Such mobile activities can be connected to the technological development including canyon-adapted water systems, which were undoubtedly introduced during the Islamic period. In modern Wadi Qasheh, there is a settlement with small-scale stepped agricultural fields and aflaj, similar to the style in Jabal Akhdar (cf. Siebert et al. 2007). We have yet to determine the origin of this settlement, but it represents the technological improvements which have helped overcome land difficulties.

The variety of land use observed in these results and discussions indicates a higher and more variegated potential of canyons for past human lives than previously recognised. This reflects the transformation of land use over time. The detected archaeological landscape and land-use in the Al-Hajar Mountains, including other canyons, present another style of ecocultural adaptation in Southeast Arabia.

Conclusion

The use of various topographies was confirmed inside the canyon despite limited land availability. Its intermediate position between the high mountains and lowland oases has functioned as a place for various activities related to transportation connecting the coast and the interior. The observed land use was undoubtedly different from that surrounding the lowland open oases and highland plateaus on the mountains.

However, the general trends of environmental and cultural changes in Southeast Arabia are also reflected in the transformation of the utilised terrain inside the canyon. Some local adaptations can be observed, in addition to typical landscape elements outside the canyon. Local adaptation cannot be classified solely according to the canyon’s available land conditions. Numerous archaeological sites in the canyon are associated with mobile activities; however, their material culture is generally similar to those outside the canyon. This indicates another form of adaptation in the arid region of Southeast Arabia, which is differentiated into lowlands and highlands.

This study also raised high expectations for similar evidence in other canyons in the Al-Hajar Mountains, which are characterised by their relatively short length (less than 20 km between the origins and the outlet). This indicates the effectiveness of the full-coverage-oriented survey in gathering evidence from all periods to bridge gaps in the understanding of the landscape in Southeast Arabia. We anticipate that this resolution will increase through further archaeological investigations. Similar relationships between topography and archaeological remains can be expected in other areas with arid conditions such as South, Southwest, and West Arabia, as well as in other regions worldwide. The methodology developed by this study can effectively be applied to the deduction of human-environmental interactions from given archaeological landscapes.

Data Accessibility Statement

The data supporting this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Notes

[1] This human perception of lands can be called fūdo (Japanese: Wind and Terrain), which was argued by the Japanese philosopher Tetsuro Watsuji (1935). He categorised the three types of old world fūdo as pastoral, desert, and monsoon. Southeast Arabia could be a mix of deserts and monsoons.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their utmost gratitude to the Ministry of Heritage and Tourism, Sultanate of Oman, for their continuous support of our archaeological expedition to Tanuf District. We are particularly thankful to His Excellency Shaykh Salim bin Mohammed Al-Mahruqi (Minister of Heritage and Tourism), His Excellency Eng. Ibrahim al-Kharusi (Undersecretary for Heritage Affairs), Mr. Sultan bin Sayf Al-Bakri (Advisor to the Minister of Heritage and Tourism), Mr. Ali Al-Mahruqi (Director of Surveys and Excavations), Mr. Khamis Al-ʿAsmi (Former Director of Excavations and Archaeological Studies), Mr. Ahmad Al-Tamimi (Former Director of the Ministry’s Ad-Dakhiliyah Branch), and all staff members of the Ministry of Heritage and Tourism, Sultanate of Oman for supporting this project. We also thank the conference organiser, UmWeltWandel Projekt, directed by Dr. Conrad Schmidt (Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen), for their kind acceptance of our paper in the workshop. Last but not least, we appreciate constructive comments from two anonymous reviewers.

Funding Information

This study was financially supported by JSPS KAKENHI JP20J01674, JP21H00605, and JP24H00112.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Author contributions

Taichi Kuronuma collected the data and wrote the draft. Takehiro Miki, Kantaro Tanabe, and Yasuhisa Kondo collected data and edited the initial draft. All co-authors’ approved the final version of the paper.