Introduction

Continental sedimentological records are crucial to study the palaeoenvironment and the palaeoclimate of any selected region. In arid environments, continuous sedimentological records (especially of fine sediments) are hard to find because of denudation processes, flash floods and aeolian dynamics which often lead either to the erosion and/or deep burial of ancient soils and sediments. This is particularly true in the Arabian Peninsula, where aeolian sand covers a wide area and flash floods are often recorded in intermittent wadis (Edgell 2006). In this area, the need for a climatic background is currently reinforced by the growing research interest on the interactions between societies and harsh environments – especially during the Palaeolithic and Early Neolithic (Atkinson et al. 2013; Crassard et al. 2013; Groucutt et al. 2015; Parton et al. 2018; Staubwasser & Weiss 2006), as well as towards the onset of irrigated agriculture in oases (Beuzen-Waller et al. 2019; Charbonnier et al. 2017b, 2017a; Cleuziou, 1997, 2009; Costa et al. 2018; Desruelles et al. 2016; Dinies, Neef & Kuerschner 2011; Purdue et al. 2019). Despite this recent and renewed interest, data are scarce for the Late Holocene and more studies are needed to draw a better picture of the interactions and retroactions between societies and their environment in a diachronic perspective, taking into account the spatio-temporal heterogeneity (due to regional topographic, hydrogeologic and climatic controls) of palaeoclimate and palaeoenvironments (Engel et al. 2017; Enzel, Kushnir & Quade 2015; Parton et al. 2018).

For the last twenty years, Holocene palaeoenvironmental and palaeoclimatic data in southeastern Arabia (Figure 1A) have been mainly derived from continental sediment records located on the western plains and piedmonts of the al-Hajar mountains, such as lacustrine and/or palustrine deposits (Parker et al. 2004, 2006; Preston et al. 2012, 2015) and aeolian ones (Goudie et al. 2000a, 2000b; Preusser 2009; Preusser et al. 2005). These archives cover most of the Early and Middle Holocene but rarely the Late Holocene. In the mountains themselves, where water resources could have favoured human occupation during periods of climatic stress, there is a real lack of data, which results from weakly-developed research as well as very badly-preserved sedimentary archives. Indeed, intense erosion, steep slopes and orographic precipitation have favoured the removal and downstream transport of most of the fine sediments. Up until today, only one study based on the sedimentary and geochemical study of sediments trapped in a closed basin infill in Oman has provided a palaeoclimatic background (Fuchs & Buerkert 2008; Urban & Buerkert 2009) between 19 ka up until 0.2 ka cal yr BP. While these conclusions provide a broad climatic framework for the Holocene, they need to be clarified and nuanced because of dating issues (14C dating processed on shells with an unknown reservoir effect and insufficient bleaching with very low environmental dose rates for precise Optical Stimulated Luminescence – OSL dating, Blechschmidt et al. 2009; Engel et al. 2024) – and because the impact of local human activities was not sufficiently taken into account.

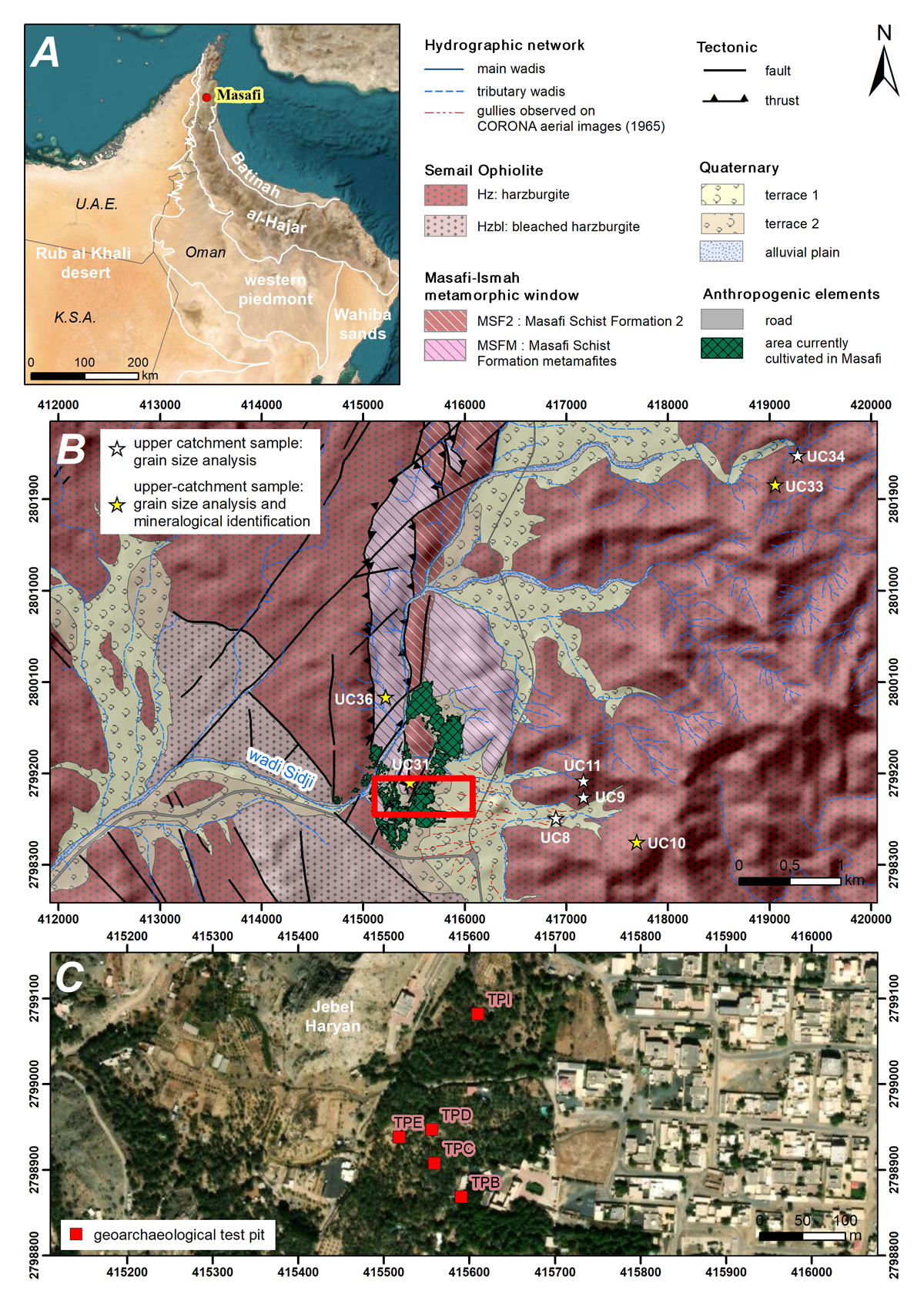

Figure 1

Regional to local contexts of the Masafi oasis. A: The south-east Arabian Peninsula and its main physiographic provinces (ESRI World Imagery). B: Geological map and reference sub-surface samples (UC – Upper Catchment samples) collected in the wadi Sidji catchment (SRTM 90 m, geology based on the British Geological Survey, 2006). C: Location of the geoarchaeological test pits dug in the oasis and presented in this paper (ESRI World Imagery).

Recent studies conducted both in the Emirates and Oman have revealed the potential of other sedimentary archives to provide a hydro-climatic framework in southeast Arabia. These archives are found in oases, which represent the heart of agricultural spaces in arid environments (Charbonnier et al. 2017b; Purdue et al. 2019). Unlike shallow agricultural terraces, generally exploited for short periods of time, some sedimentary archives in oases are composed of more than 5 m of vertically accumulated sediments (Purdue et al. 2019; Costa 2022). However, one critical issue in the study of these archives is that a significant part of the deposits are irragric soils. Therefore, this archive does not constitute, as it stands, a strictly palaeoenvironmental record but rather the result of combined anthropogenic (agricultural) and hydro-climatic factors. In order to provide a new climatic background in the northern al-Hajar mountains based on the study of oasian sedimentary archives, one major challenge is to develop a methodological background to decipher these factors from one another.

To answer these questions, we develop in this manuscript an approach combining geomorphic surveys and field geoarchaeology with laboratory analyses (particle size distribution and mineralogy). This approach allows us to identify sediment origins and transportation modes, and discuss the morphoclimatic and anthropogenic processes behind these dynamics. This approach was applied in the oasis of Masafi (United Arab Emirates) (25°18’N, 56°09E, Figure 1A) which has been studied since 2011 in the framework of the French Archaeological Mission in the UAE (Dir. A. Benoist, J. Charbonnier) and the ANR Project OASIWAT (Dir. L. Purdue). In this oasis, multiple continental archives have been discovered and reveal active sedimentary and erosional processes since the Late Pleistocene (Purdue et al. 2019), providing an important framework to interpret archaeological records.

Environmental background

Geography, geology and hydrography

Southeast Arabia is composed of four main geomorphic units: the coastal plain, the northern Rub’al-Khali, the al-Hajar piedmonts and the al-Hajar mountains (Figure 1A). The coastal plain lies between 0 and circa 80 m a.s.l. (above sea level). Composed of very low and progressive slopes, most of this region is covered by Quaternary formations (aeolian sand dunes, sabkha, desert plains, beach, delta and shoal deposits), although outcrops of Mid-Pliocene formations (coastal, evaporite, fluvial, conglomeratic or dune formations) are still visible locally (Thomas et al. 2014). The piedmonts, with an elevation between 80 to circa 250 m a.s.l., are comprised of fans, megafans and coalescent wadi alluvium (Hili Formation) interstratified with aeolian sediments (Al-Farraj & Harvey 2005; Dalongeville 1999; Farrant et al. 2015; Parton et al. 2015). The Rub’al-Khali dunes extend up to the coast and cover the western part of the Hili Formation (Farrant et al. 2015; Goudie et al. 2000a, 2000b). The al-Hajar mountains cover the eastern part of the UAE and Oman. In the UAE, elevation ranges from 250 m a.s.l. to more than 2,000 m a.s.l. Permian to Cretaceous limestone and dolomite of the al-Hajar Supergroup compose most of the mountains in its northern part. Gabbro, peridotite and serpentinite, part of the ophiolite complex (Semail Formation), are located in the central part of the mountains (Thomas et al. 2014).

The oasis of Masafi (450 m a.s.l) lies in the watersheds of the wadi Sidji, which drains the al-Hajar to the western inner piedmonts (Figure 1A, B). The oasis is located at the interface between ophiolitic outcrops of the Semail Formation (harzburgite more or less serpentinised, hard veins of carbonate – mainly dolomite and magnesite), metasediments (quartzite, quartz-mica-schist and chlorite-quartz schist) and coalescent alluvial fans coming from the east (wadi alluvium, sand veneer, colluvium, etc.) (Figure 1B) (British Geological Survey 2006; Grantham et al. 2003). At the contact between these three formations, a geophysical survey (ERT) reveals the existence of a fault depression in the oasis (Purdue et al. 2019). This configuration has generated a large sediment trap in the core oasis.

Climate, palaeoclimate and palaeoenvironment

The area is included in the BWh area of the Köppen-Geiger climatic classification – i.e. desertic, arid or hyperarid. Present day mean annual rainfalls are higher than in central, west and north Arabia. They vary from less than 50 mm at the margins of the Rub’al-Khali (Edgell 2006) to 85 mm on the Gulf coast and around 180 mm in the al-Hajar mountains (Tourenq et al. 2009, 2011). In Masafi, the average annual precipitation is 179 mm (1968–2004) with a very high temporal variability and the mean air temperature is 26.8°C (max. of 43°C in June and min. of 11,4°C in December) (Tourenq et al. 2009). These high temperatures imply high average evaporation rates of 10,7 mm/day (max. of 21,2 mm in June and min. of 31 mm in January) (Tourenq et al. 2009). Strong and relatively steady winds circulate from the WNW to the ESE all year long (Shamal) (Farrant et al. 2015) and from the NE to the E (N’aschi) during the winter (Edgell 2006).

For older periods, data are patchy in southeastern Arabia (Enzel, Kushnir & Quade 2015; Parton et al. 2018). In the al-Hajar mountains, a period of high aridity and enhanced aeolian dynamics is recorded between 19 and 13 ka (Urban and Buerkert 2009). In general, palaeoenvironmental records are better known for the Early-Mid Holocene period (ca. 11–4.2 ka). The dating of geomorphic features such as lacustrine beds, fluvial deposits, dunes or speleothems, suggest an onset of increased humid conditions around 11–10 ka south of the Peninsula, influenced by the northward migration of the ITCZ (Intertropical Convergence Zone) and increased monsoonal precipitations (Edgell 2006; Farrant et al. 2015), which reached the coast of the Gulf around 9 ka (Parker et al. 2016). Lacustrine archives indicate a rich grassland cover with woody elements on the south coast of the Gulf (Parker et al. 2004, 2006; Preston et al. 2012, 2015). Wetter conditions during the Early Holocene Humid Period lasted from 9 to 6.4 ka, followed by a more arid period between 6.4 and 5 ka and by another wetter period (Mid-Holocene Humid Period) from 5 to 4.3 ka (Parker et al. 2016; Urban and Buerkert 2009). A pronounced peak of aridity then started and lasted until 3.9 ka (Parker et al. 2016; Preston et al. 2012), with a peak of aridity around 4.2 ka (Watanabe et al., 2019). Data are very scarce for the Late Holocene, but it is generally assumed that the climate remained arid up until today. Recent records from the Hoti cave indicate with more precision periods of reduced humidity between 250 BCE – 25 CE, 480–900 CE and 1050–1300 CE (Fleitmann et al. 2022).

Materials and Methods

Previous research on the chronostratigraphy of oasian sedimentary archives

In the framework of the French Archaeological Mission in the UAE and the ANR OASIWAT project, more than twenty test pits have been dug in the oasis of Masafi. The stratigraphy exposed, which can reach nearly 5m in some areas, is comprised of a succession of silts, sands and gravel, some presenting traces of soil development and exploitation, while others being typical of alluvial sedimentation. Five test pits will be presented in this manuscript (Test Pits B, C, D, E and I, Figure 1C) which have been presented in previous publications (Charbonnier et al. 2017b; Costa et al. 2018; Costa 2022; Purdue et al. 2019). These test pits have been framed chronologically with 10 radiocarbon dates, 3 OSL dates and sherds collected during excavation (Supplementary File 1). In the field, the lithostratigraphy was described based on the definition of stratigraphic units (SU) discriminated according to soil texture, structure, stratigraphic boundaries, colour and inclusions. The precise description of the strata allowed us to create a typology of the deposits and define six pedo-sedimentary facies. The detailed typology is available in Purdue et al. 2019 as well as in Supplementary File 2. Facies 1 is composed of white to beige silts with various degrees of soil development. Facies 2 characterizes weakly-sorted clayey silts, rich in boulders, stones and local gravel of harzburgite. Facies 3 is composed of gravelly sediments. Facies 4 is characteristic of agricultural deposits, which differ in color (reddish brown to greyish beige) and inclusions (charcoal, ashes, shells). Facies 5 is typical of backfill or slopewash deposits (stones, boulders, sand), while Facies 6, composed of well-sorted white silts, is interpreted as aeolian or abandonment sediments. This typology allowed us to propose a chronostratigraphic phasing covering the last 20 ka. Our major results indicate the existence of a natural humid area during the Late Pleistocene up until the Early-Mid Holocene (18–6.3 ka) (Facies 1 and 2). Agricultural expansion is recorded during the Iron Age (~3210–2380 cal yr BP) and the Late Islamic Period (>550 cal yr BP) (Facies 4). Scarce evidence of farming activities with complex hydro-climatic signatures are attested during the Pre-Islamic and Early Islamic Period (~2300–550 cal yr BP) (Facies 4 and 6) and episodes of fluvial detritism clearly noticed at the end of the Iron Age (~2380–1870 cal yr BP) (Facies 3).

With the aim to better understand depositional dynamics in oasian environments, bulk and micromorphological samples were collected in the middle of the stratigraphic units of Test Pit B, C, D, E and I to conduct multi-proxy analyses, including sedimentological and mineralogical studies presented in this manuscript.

Geomorphic surveys

Local to regional geomorphic surveys were conducted during several field sessions between 2011 and 2017 in the present-day oasis of Masafi and in the upstream and downstream section of the wadi Sidji (Figure 1B). The objective was to locate vertically preserved sedimentary sequences that could provide a hydro-climatic background in the area and identify preserved pockets of (fine) sediments which could have supplied the oasis with potentially cultivable deposits. When encountered, these sediments were sampled (~100 g) for laboratory studies and referred to as upper catchment samples (UC). Eight of these reference samples were collected (Figure 1A).

Particle size analysis

To identify sediment transport and deposition modes, particle size analyses were conducted on 69 samples, including 61 samples from Test Pit B, C, D, E, I and 8 upper catchment samples (see Supplementary File 3 for the list of samples analysed). Analyses were performed using a Malvern Mastersizer 2000 laser granulometer at the OMEAA laboratory (CNRS UMR5600 EVS and CNRS UMR5133 Archéorient, Lyon, France) after samples were prepared according to the protocol provided in Supplementary File 4. Results include sediment distribution (percentage of clay, silts, sands), their number of modes (unimodal, bimodal, trimodal or polymodal) and their P50 and P90. In order to create a typology of the deposits, statistical analysis was conducted on these samples using the Principal Component Analysis and Ascending Hierarchical Classification function of the package FactoMineR on R.

Mineralogy and micromorphology

To characterize the origin of the sediments in the oasis (local to regional), we developed a mineralogical study of both reference deposits and sediments within the oasis.

Four upper catchment samples and one subsurface oasis soil were processed in thin sections. In parallel, 15 soil micromorphological samples from TP B (4 thin sections) and C (11 thin sections) were prepared at the Servizi per la Geologia, Massimo Sbrana Laboratory (Piombino, Italy) and the laboratory Geosciences Montpellier, Atelier Lithopréparation (Montpellier, France). On each micro-stratigraphic unit identified in the thin sections, three random areas were selected, each one measuring 4 mm². In these areas, all the grains <200 µm were point-counted, their percentage estimated and averaged per area. Particles larger than 200 µm were mentioned by presence/absence. Due to the systematic presence of serpentine and olivine of various sizes in the deposits, we decided to estimate their percentage (referred to as auxiliary components) as a proportion of the total area for particles between 200 µm and 2 mm. We defined three degrees of contribution of these elements (Table 1). In order to better identify mineral assemblages, we also conducted a Principal Component Analysis and Ascending Hierarchical Classification on these samples using the function of the package FactoMineR on R.

Table 1

Degree of contribution of auxiliary components (serpentine and olivine) in the mineralogical assemblage.

| DEGREE OF CONTRIBUTION | % AUX. COMP. (<200 µM)a | % AUX. COMP. (200 µM- 2 MM)b |

|---|---|---|

| +++ | 20–25 | 15–30 |

| ++ | 10–15 | 5–15 |

| + | 5–10 | <5 |

[i] a: % of aux. comp. point counted in three areas of 4 mm² per micro-stratigraphic unit.

b: semi-quantification of aux.comp. as proportion of total area in the whole micro-stratigraphic unit.

Based on local geology, we expected to identify minerals belonging to the ophiolithic sequence, such as serpentinised olivine (70–90%), ortho- (10–30%) and clino-pyroxenes (<3%) as well as metamorphic outcrops (quartz, chlorite, mica, feldspar plagioclase, clinopyroxene and amphibole) (Goodenough et al. 2006; Roberts et al. 2016; Searle et al. 2014; Tegyey 1990). The other minerals identified (micrite, calcite, glauconite, epidote) are necessarily of regional origin.

Results

Geomorphic surveys

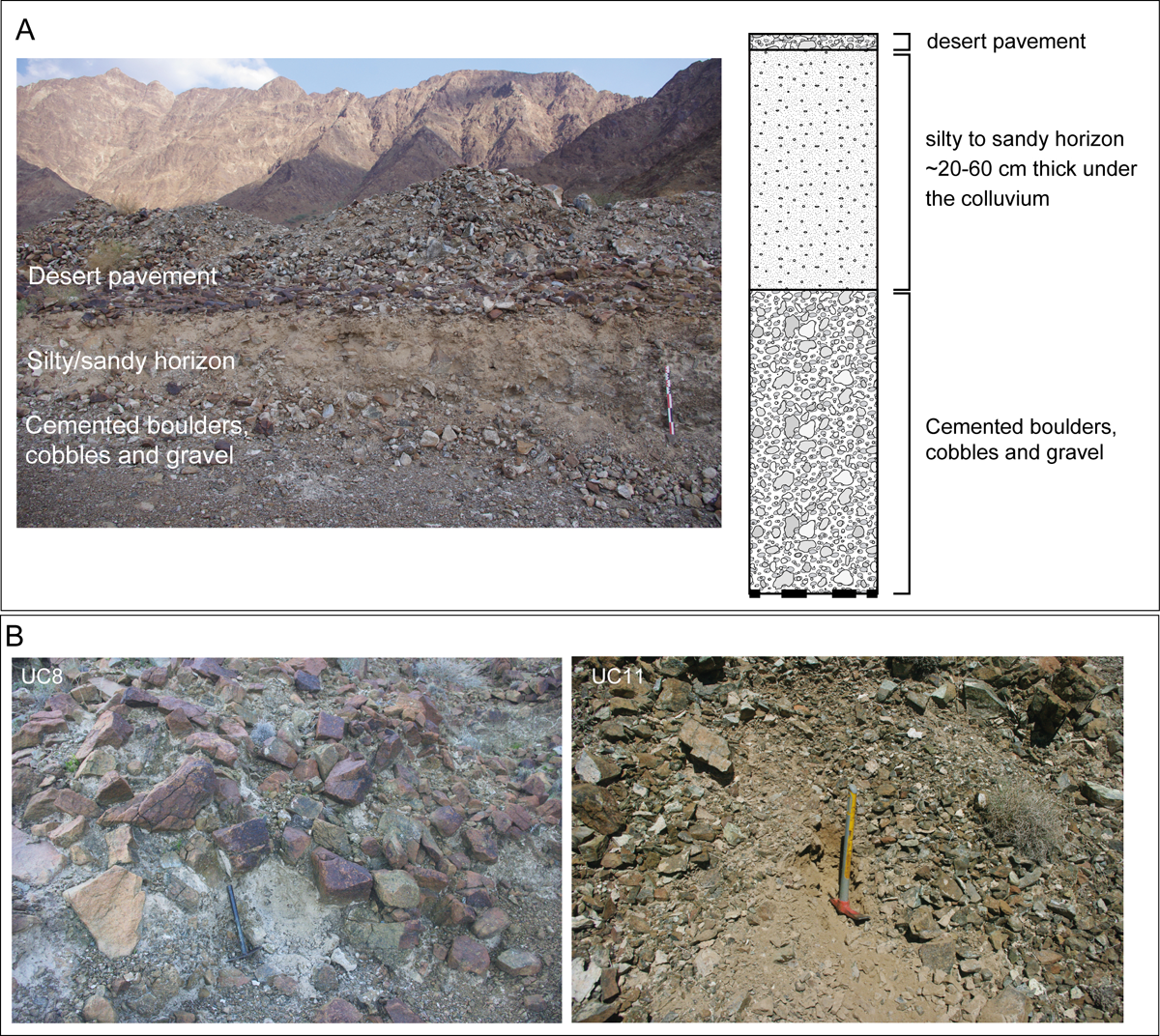

Widespread shallow deposits of fine sediments in the upper catchments

Surveys in the upstream watersheds did not allow for the identification of continuous stratigraphic sequences of fine sediments. Terraces and fans composed of cemented cobbles and boulders are omnipresent in valley bottoms, and are sometimes thicker than 25 m. On the slopes, the substratum outcrops in the higher and/or steepest areas. Most of the time, however, it is covered with colluvium composed of gravel and pebbles which cover 20–60 cm of fine silts and clays mixed with gravel and sands. This sedimentary succession was observed in various areas, even at the heads of the catchments and upstream of the concentration of flows (Figure 2).

Figure 2

A: Schematic sedimentary succession observed in the upper part of the superficial formations. B: Examples of fine sediments collected in the upstream catchments (see Figure 1B for location of the samples).

Pockets of fine sediments in the downstream section of the watersheds

No natural sequences, both chronologically complete and thick enough to ensure good temporal resolution, have been discovered in the areas surrounding the Masafi oasis. Surveys enabled us to observe pockets of loose fine sediments downstream of Masafi in some of the alluvial terraces of the wadi Sidji. Although scattered and small in size, they reflect significant erosive dynamics. However, most of the fine sediments are concentrated much further downstream in alluvial fans, near the western foothills of the al-Hajar mountains. Therefore, the only possible record of hydro-climatic changes in the mountain themselves is recorded in oasian sequences.

Particle size analysis and mineralogical results

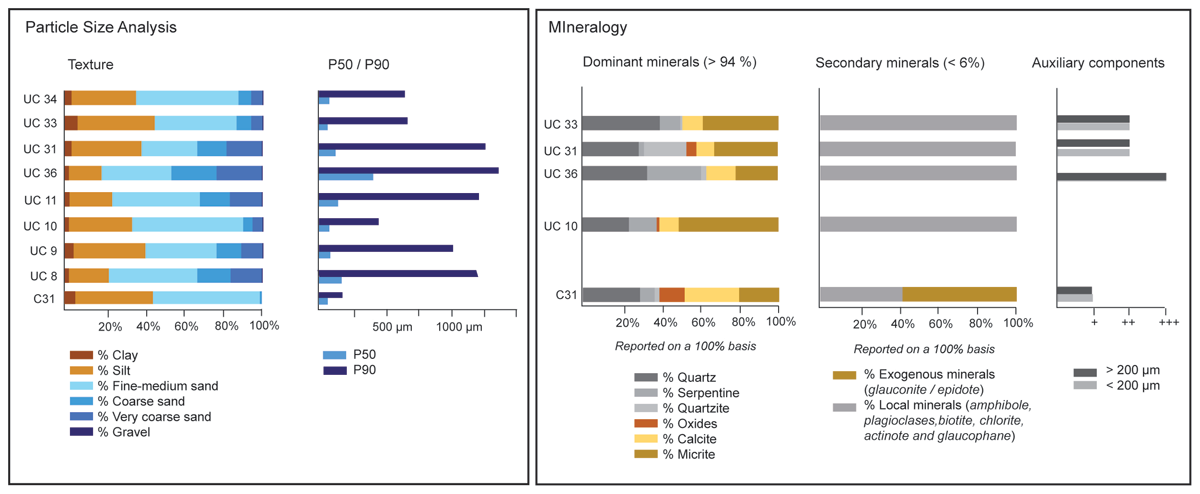

Characterization of the reference samples

Eight upper catchment reference samples were collected in fine deposits east (UC8, 9, 10 and 11), north (UC33, 34), and west (UC36) of the oasis, on top of the Jebel Haryan (UC31) as well as within the oasis itself (C31) (Figures 1B, 2A). Particle size analysis indicate that these deposits are bi- to trimodal sandy loams and loamy fine sands with a high concentration in coarse and very coarse sands (mean P90: 950 µm, mean P50: 147 µm) (Figure 3 and Supplementary Files 5 and 6 for numerical details). Dominant minerals (>94% of the counted grains) include quartz (26%), micritic calcium carbonates (26%), calcite (13%), serpentine (10%) and quartzite (4%). Secondary minerals include local amphibole, micas and pyroxene, while plagioclases, chlorite, epidote, actinote and glaucophane appear as traces (<1%). As a remark, UC33, UC31 and UC36 stand out by their concentration in quartz, quartzite and serpentine. UC31 and C31, sampled in the core oasis, are richer in oxides, and contain traces of glauconite and epidote, absent from the other reference deposits.

Figure 3

Result of the grain size analysis and mineralogy on the reference samples collected in the watershed and in the oasis.

Results in oasian sedimentary sequences

The sediments collected within the five oasis soil sequences are mainly composed of trimodal silt and sandy loam (Figures 4 and 5, see Supplementary file 1 for more details on chronology, see Supplementary files 5 and 6 for numerical details). Major peaks are recorded in fine sands (~100 µm), coarse sands (500–1300 µm) and fine silts (5–20 µm). P50 values range from 8 to 110 µm while P90 values ranges from 70 to 1200 µm. All the minerals observed in the reference samples were identified. In average, quartz (39%), calcite (22%), micrite (18%) and serpentine (10%) dominate, while quartzite (4%) and oxides (5%) are present in a much lesser content. Pyroxene, amphibole, plagioclases, olivine, micas, chlorite, glauconite and epidote represent less than 6% of the total % of the grains counted. We present below the particle size and mineralogical results per test pit.

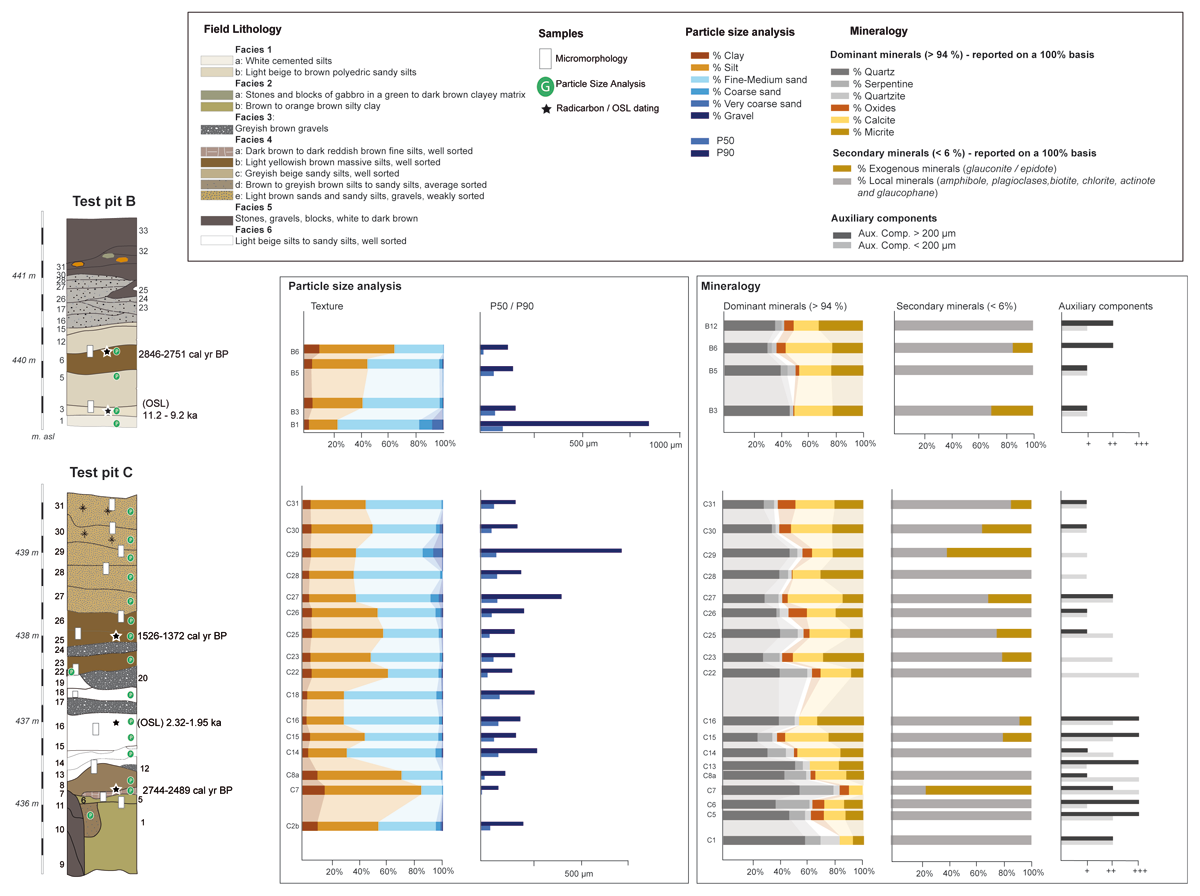

Figure 4

Field lithostratigraphy Lithostratigraphy and chronology (Purdue et al. 2019) and results of the grain size analysis and mineralogy in TP B and C.

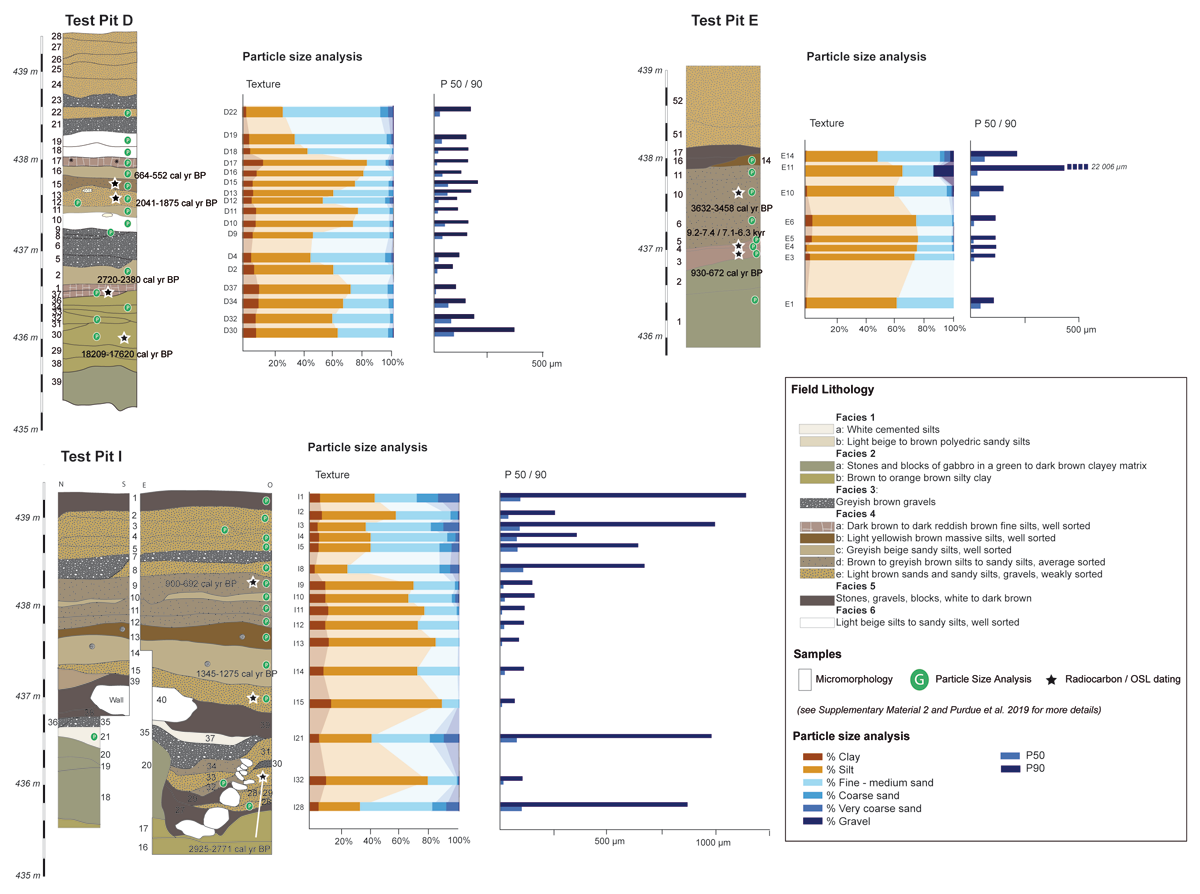

Figure 5

Field lithostratigraphy and chronology (Purdue et al. 2019) and results of the grain size analysis in TP D, E and I.

Test pit B

Four stratigraphic units were studied for grain size analysis and mineralogy (Figure 4). The base (sample B1) is composed of cemented trimodal loamy fine sands (P50: 110 µm, P90: 810 µm) rich in small gravel of harzburgite. Above, B3 (dated from 11.2 – 9.2 ka) and B5 are comprised of trimodal to polymodal sandy loam (P90: 67–73 µm, P50: 160–170 µm). The mineral assemblage is comprised of quartz, micrite and calcite, some occasional allochthonous minerals and a low content in auxiliary component. A shift in the mineral assemblage in favour of calcite, micrite, oxides, a higher auxiliary component content >200 µm and some exogenous minerals was noticed in B6 (dated from 2845–2751 cal yr BP, Iron Age) and B12. The texture of the deposits decreases with the deposition of polymodal silt loam (P50: 26 µm, P90: 130 µm).

Test pit C

Sixteen samples were studied for grain size analysis and mineralogy (Figure 4). Strata C1–C8a are composed of trimodal to polymodal loam and silt loam (P90: 90–125 µm, P50: 10–20 µm). The deposits are rich in quartz, some cemented in exogenous micritic nodules, serpentine, quartzite, rounded iron/manganese oxides and numerous auxiliary components. C7 was dated from 2742–2490 cal yr BP and contains a higher percentage of exogenous minerals. Soil texture and composition evolves in C13 to C18. The deposits are comprised of trimodal sandy loam (P50: 70–95 µm, P90: 180–280 µm) occasionally laminated, deposited between 2.23–1.95 ka. Minerals include micrite, calcite and allochthonous minerals. Above, three layers of harzburgite gravel (C17 to 20) were observed in the field. They are sealed by trimodal (silt) loam (P50: 35–60 µm, P90: 160–215 µm) (C22 to C26) dated from 1518–1358 cal yr BP. These deposits stand out by an important decrease in auxiliary components and a higher concentration in oxide nodules and calcite. This mineralogical trend remains similar in the upper section of the pit (C27 to 31) but the deposits are coarser (sandy loam with P50: 70–80 µm and P90: 175–710 µm).

Test pit D

Seventeen samples were studied for grain size analysis (Figure 5). The base of the pit is composed of stones and boulders of harzburgite cemented in reddish yellow silty clays dated from 18,257–17,587 cal yr BP. D30 to D37, which belong to the same sedimentary environment, are very poorly sorted tri- to polymodal silt loam (P50: 16–40 µm, P90: 165–180 µm). D37 was dated from 2719–2370 cal yr BP. These deposits are sealed by trimodal sandy loam (P50: 40–70 µm) alternating with gravel and fine sand (D2 to D9). Above, nearly 1 m of very poorly sorted bimodal to trimodal silt loam (D10 to D17) (P50: 10–50 µm, P90: 90–170 µm) were dated from 2038–1830 cal yr BP (D12) up until 657–553 cal yr BP (D16). Last, samples D18 to D22 are poorly sorted trimodal to polymodal silt loam, sandy loam and loamy fine sand (P50: 70–100 µm, P90: 150–390 µm) richer in coarse gravel.

Test pit E

Eight samples were studied for grain size analysis (Figure 5). The base of the sequence (E1 to E3) is composed of poorly sorted polymodal silt loam (P50: 15–50 µm, P90: ~100 µm). E3 was dated from 9.23–7.41 kyr (Age pIR-225) to 7.07–6.33 kyr (Age IR-50) (Early Holocene). Above, E10 to 14 are comprised of trimodal silt-sandy loam (P50: 30–65 µm, P90: 150–22 000 µm).

Test pit I

Sixteen samples were processed for grain size analysis. The base of the pit (I21 and I28) is comprised of trimodal sandy loam (P50: 80–100 µm, P90: 860–970 µm). I29 was dated from 2925–2771 cal yr BP. Above, samples I32 to I9, probably dated from the Iron Age up until the Islamic Period (900–692 cal yr BP), are composed of trimodal silt loam (P50 <25 µm, P90: 70–150 µm). Last, samples I8 to I1 are comprised of trimodal loam and sandy loam (P50: 40–110 µm, P90: 350–1200 µm). These deposits stand out from the others by a high increase in medium sand, coarse sand and gravel.

Interpretation

Sedimentary environment classification

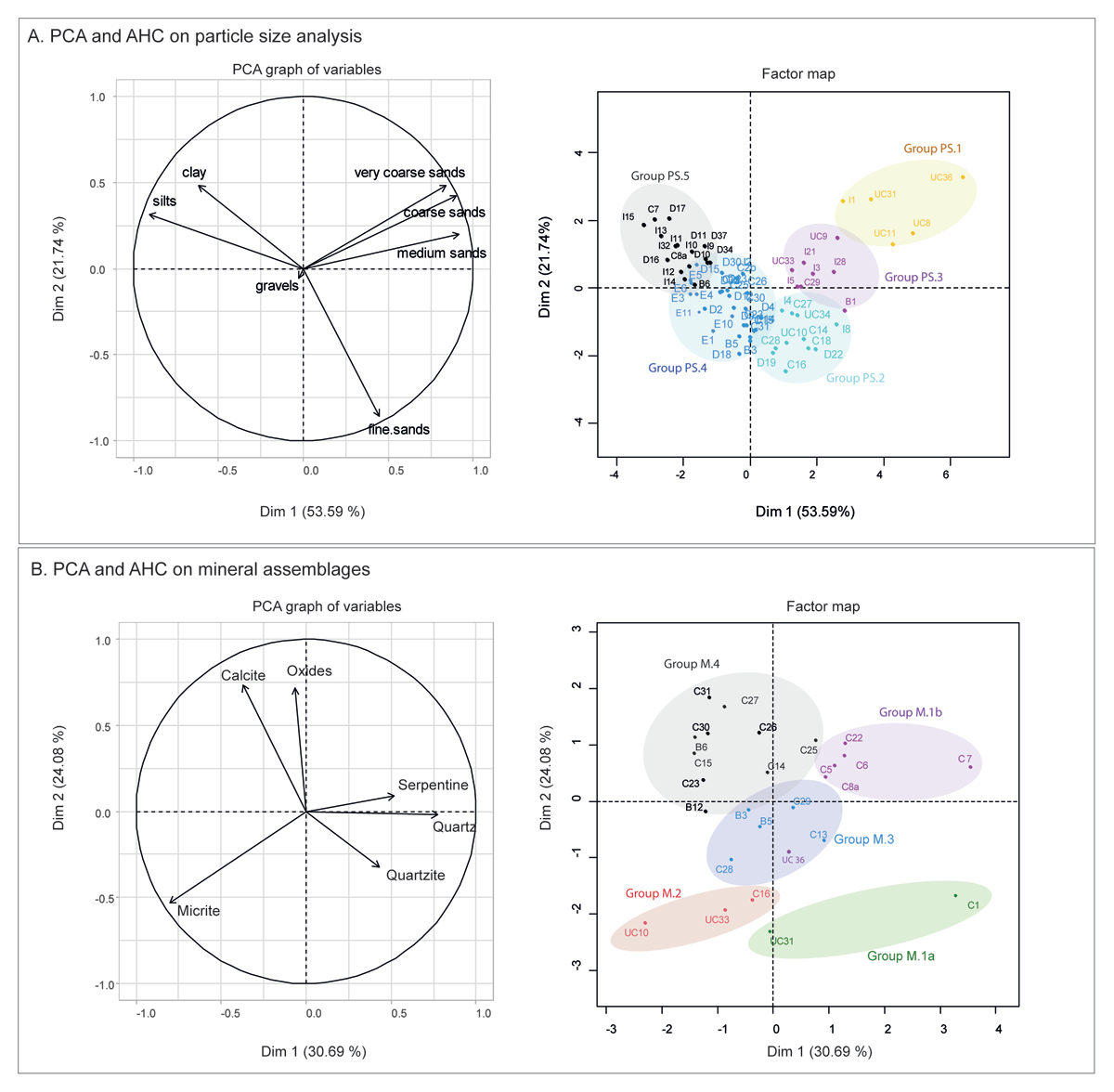

The PCA and AHC conducted on 69 samples structured sediment diversify in 5 groups (Group Particle Size-PS. 1 to 5) (Figure 6A). The first two dimensions carry 75.33% of the inertia. The first axis (53.59%) opposes silts and clay with medium, coarse and very coarse sands. On the point cloud, we can see that this axis is mainly pulled by the reference deposits. The second axis (21.74%) correlates mainly with the % of fine sands. We propose below a first interpretation of these groups, based on textural differences, P50, P90, distribution and confrontation with field interpretations.

Figure 6

Principal component analysis to characterize sediment environment and origin. A: PCA conducted on the texture (clay to grave) of 69 samples, presentation of the first and second dimensions. B: PCA conducted on the dominant minerals (>94%) of the mineral assemblage of 27 samples, presentation of the first and second dimensions.

Group PS.1: In situ aeolian fine sands and autochthonous very coarse sands

These deposits comprise 5 reference samples (UC8, 9, 11, 31 and 36) and 1 sample from Test Pit – TP I (I1). They correspond to very poorly sorted sandy loams and loamy fine sands (P50: 90–400 µm, P90: 1000–1300 µm), bi- to trimodal, with two major modes around 105 µm (fine sands) and 1100 µm (very coarse sand). In view of the location of the samples within the watershed and the absence of fine local weathered material in these areas, we put forward that the 105 µm peak corresponds to aeolian very fine sands while the second mode corresponds to the weathering of local geological formations.

Group PS.2: Hydric remobilization of aeolian fine sands and autochthonous coarse sands

This group includes 2 reference samples (UC 10, 34) and 10 samples (C14, C16, C18, C27, C28, D19, D22, I4). The deposits are very poorly sorted sandy loams (P50: 77–97 µm, P90: 200–630 µm), trimodal, with a major mode around 105 µm (fine sand) and a second one between 550–1100 µm (coarse sand). Interpreted in the field as being aeolian, abandoned or irrigation canal deposits (Facies 4e and 6), we can interpret this group as aeolian very fine sands remobilized with coarse local sands and deposited in the oasis through low intensity hydric processes.

Group PS.3: Intense hydric remobilization of aeolian fine sand and autochthonous coarse sands/marling

This group comprises 1 reference sample (UC33) and 7 samples (B1, C29, I3, I5, I8, I28, I21). They correspond to very poorly sorted sandy loams and loamy fine sands (P50: 80–110 µm, P90: 630–990 µm), tri- to polymodal, with a major mode around 105 µm (fine sand) and a second one between 725–1100 µm (coarse sand). This group stands out from the others by the percentage of particles >2 mm. These deposits were interpreted in the field as natural deposits (Facies 1a) as well as anthroposoils (Facies 4e), rich in gravel and secondary carbonates. We can interpret these deposits as aeolian ones remobilized by intense hydric processes (which could explain the presence of gravel) or remixed deposits in the oasis for agricultural practices (marling).

Group PS.4: Pedogenized bioturbated/manured aeolian fine sand

This group comprise 28 samples (B3, B5, C2b, C7, C15, C22 to C26, C30, C31, I2, E 1 to E14, D30, D32, D2, D4, D9, D 12, D13, D18), which are very poorly sorted silt loams and sandy loams (P50: 8–73 µm and P90: 90–250 µm). They appear trimodal to polymodal, with the principal mode around 70–105 µm (fine sand), a secondary one around 9–17 µm (fine silt), and a minor third mode between 480 and 950 µm (medium and coarse sands). Similarly to the other groups, the principal sedimentary source seems to be aeolian very fine sands (~100 μm), sometimes mixed with local medium/coarse sands (>500 μm). However, these samples are also enriched in finer particles. In the field, these deposits were classified as natural Pleistocene soils as well as anthroposoils (Facies 1a, 2b, 4b, d, e). Based on the context, this group can be interpreted as in situ windblown sediments (if no large auxiliary component) or remobilized aeolian fine sand, more or less pedogenized and/or manured cultivated soils.

Group PS.5: Manured (ashes) aeolian fine sand

This type includes 17 samples (B6, C8a, D10, D11, D15 to D17, I 9 to 15, I32). They correspond to very poorly sorted silt loams (P50: 10–27 µm, P90: 86–160 µm). They are tri- to polymodal, with a principal peak between 5–20 µm (silt), a second one around 60–105 µm (fine sand), and an occasional one between 480–550 µm (medium sand). In the field, these deposits were classified as anthroposoils (Facies 4a to d). Six of them belong to the field Facies 4d, ie greyish agricultural layers with ashes. We can interpret this group as enriched aeolian fine sands but also as ashy deposits mixed with in situ windblown particles.

Origin of the sediments and soils in the oasis

The PCA and AHC conducted on the dominant minerals (quartz, calcite, micritic calcium carbonates, quartzite and oxides) of the 27 samples structured sediment origin in 4 groups (Group Mineralogy – M1 to 4). The first two dimensions carry 54,77% of the inertia (Figure 6). The first axis (30.69%) opposes micritic assemblages to the ones composed of quartzite, quartz and serpentine. On the point cloud, we can see that this axis is mainly pulled towards micritic assemblages by the reference deposits UC10, UC33 and UC16, and towards quarzitic deposits by the reference sample UC31. The second axis is positively pulled by calcite and oxides.

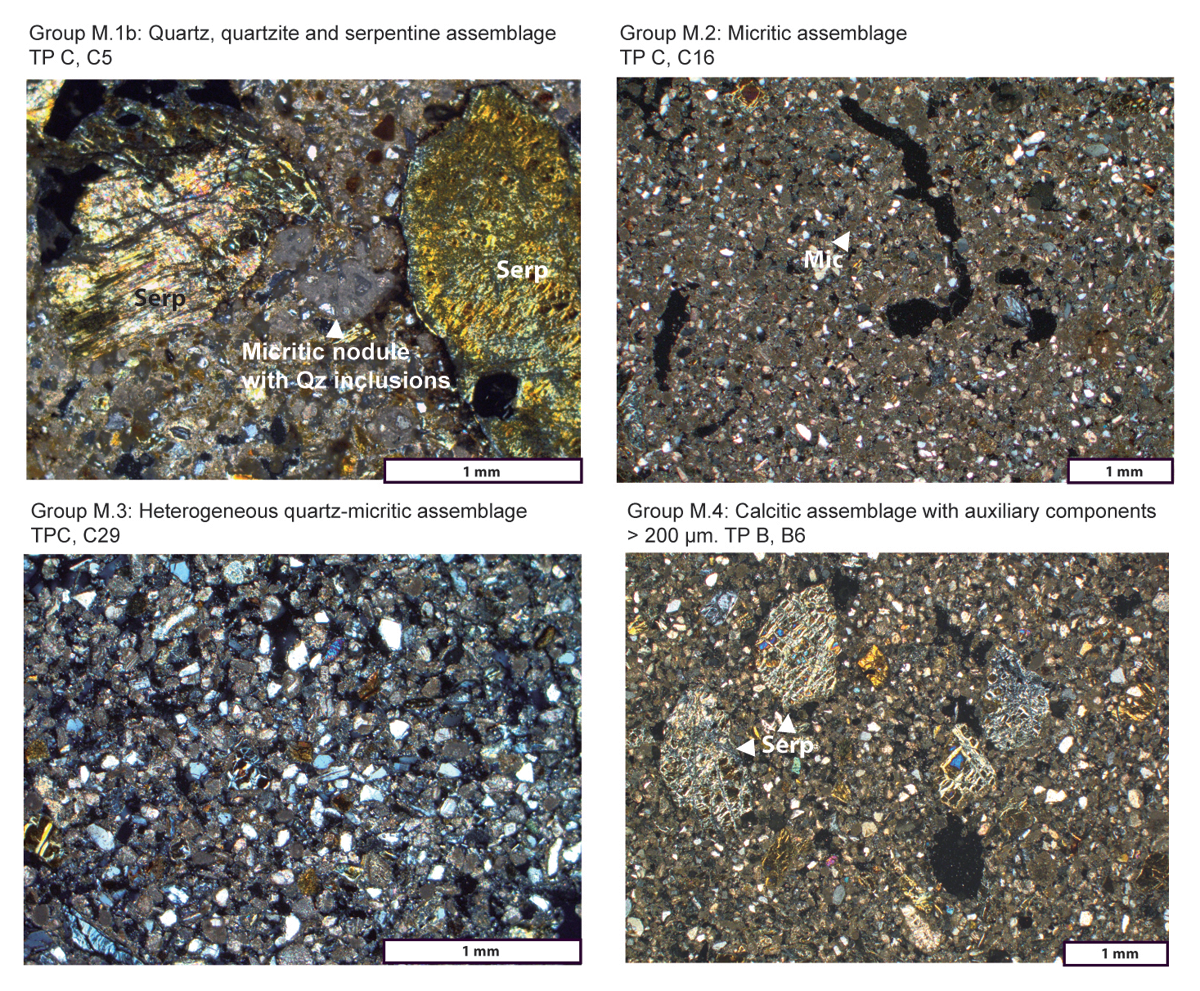

Group M.1. Quartz, quarzitic and serpentine mineral assemblage

This group stands out by its concentration in quartz, serpentine, quartzite, and micritic calcium carbonates grains often cemented around quartz grains. The auxiliary component contribution of various sizes (serpentine and olivine) is high. Two sub-groups have been defined. Group 1a (C1, UC31) is characterized by a higher concentration of quartzite, muscovite and amphibole while Group1b (C5, C6, C7, C8a, C22, UC 36) contains more serpentine (Figure 7). This mineral assemblage corresponds to a mixture of local metamorphic and ophiolitic minerals with non-local quartz and micrite, which can be due to combined and successive processes: 1/ in situ weathering of metamorphic deposits, 2/ local aeolian remobilization of weathered metamorphic sediments combined with regional aeolian processes depositing quartz grains, some cemented in pedological micritic carbonates. The presence of large serpentine fragments suggests their hydric remobilization. In the field these deposits were classified as Facies 2b (pedologically evolved quaternary deposits) but also as anthroposoils (Facies 4a and 4d), characterized by their content in charcoal and ashes. The presence of micrite could therefore also result from agricultural practices.

Figure 7

Microphotographic in Crossed Polarized Light of the various mineralogical groups identified in the reference and archaeological deposits in the oasis (Serp.: Serpentine; Mic: Micrite; Qz: Quartz, Qtzite: Quartzite).

Group M.2. Micritic mineral assemblage

This group mainly includes reference samples from the eastern, northern and western part of the watershed (UC 10, UC 33 and C16). They stand out by their concentration in micritic calcium carbonates and quartz, as well as serpentine of various sizes (Figure 7). This allochthonous assemblage is the result of regional wind transport with limited runoff and small watercourse input. It was classified in the field as Facies 6.

Group M.3. Heterogeneous quartz-micritic mineral assemblage

The deposits in this group correspond to a mix between Groups M.1 and M.2. The mineral assemblage is composed of quartz, olivine and serpentine, a low % in calcite and an average one in micrite (UC B3, B5, C28 and C29) (Figure 7). The contribution of the auxiliary components is low. These deposits correspond to a mix between two allochthonous mineral assemblages resulting from regional wind transport. In the field, they were classified as Facies 1b (light beige Early Holocene aeolian deposits), and Facies 4e (light brown gravelly anthroposoil rich in charcoal).

Group M.4. Calcitic mineral assemblage

This mineral assemblage is mainly characterized by a higher content in calcite and oxides, the presence of glauconite and epidote, associated to a slight decrease in quartz, micritic calcium carbonates and serpentine (sample B6, B12, C14, C15, C23, C25, C26, C27, C30, C31) (Figure 7). In general, the contribution of auxiliary components is low. Due to the allochthonous presence of calcite, glauconite and epidote, we suspect the existence of pockets of aeolian sand in the watersheds, occasionally remobilized by hydric processes or irrigation processes. In the field, these deposits belong to Facies 6, interpreted as aeolian or abandonment deposits but also to Facies 4b and 4e, which correspond to light brown anthroposoils, rich in shells, gravel and highly bioturbated.

Sedimentary processes and depositional environments: between natural and anthropogenic processes

Despite surveys in the surrounding watersheds, it was impossible to find a sequence of fine sediments outside of the oasis exceeding a few decimetres. Conversely, the Masafi oasis contained both thick and extensive deposits, spanning from the Late Glacial Maximum to the present day. Agricultural sequences in oases can therefore provide a new type of sedimentary archive in arid mountain environments of the Arabian Peninsula, less subject to erosion than areas outside of the oasis. However, it is necessary to untangle the mixed environmental, climatic and anthropic signal within these sequences. Based on the particle size and mineral groups identified and their interpretation, we can put forward three dynamics of depositions and natural/anthropogenic post-depositional processes.

Aeolian sedimentation in the catchment and wind powdering in the oasis

Our results highlight the crucial importance of wind transport processes in the al-Hajar mountains. All the samples are comprised of a fine sand aeolian input (circa 100 µm in size) (Group PS. 1 to 5). Three different aeolian sources were identified. The first one contains quartz minerals (Group M.1), the second one micritic calcium carbonates (Group M.2) and the last one calcite-glauconite-epidote (Group M.3). The specific geomorphic context of Masafi – as well as its archaeological context of irrigated cultivation- has favoured the catchment of windblown suspended particles and their hydric reworking. This raises the question of the location of the recycled primary aeolian deposits: were there thick loess sequences in the watershed deflated or eroded during distinct climatic phases (more frequent or severe precipitation), or rather veneers and dusting gradually carried away towards the oasis during runoff events or increased wind erosion?

Local sediment input and runoff remobilization

The oasis of Masafi is located at the terminal end of alluvial fans coming from the east. The bedrock is composed of harzburgite and metamorphic rocks rich in quartzite, muscovite, amphibole, olivine and serpentine (Group M.1). The mineralogical assemblages within the oasian sedimentary sequences are composed of these minerals in various proportions and size which allow us to monitor the intensity and contribution of lateral inputs. Apart for some of the reference samples (Group PS.1), they correspond to coarse to very coarse sand inputs (Group PS.2 and PS.3). Their occurrence in the oasis results both from natural processes, such as uncontrolled guylling, as well as controlled irrigation and sediment filtering through headgates.

Soil development and anthropogenic processes linked with agricultural practices

Despite the possible natural origin of the deposits, one must remember that oases are artificial man-made landscapes. In order for the land to be productive, soils as well as agricultural practices are crucial. Various practices, which aim at creating soils, fertilizing them or remodelling them in order to facilitate gravitarian irrigation have an impact on sedimentary and mineralogical signatures. First, soils can be created with ashes and manure only, adding organic and calcitic elements (micrite <4 µm) to the soil (Group PS. 5). Marling, which corresponds to the voluntary displacement of soil to create cultivable areas, has also been noticed in Masafi, such as long-distance (eg. adding of marine sand which included marine shells) or short-distance displacement. Indeed, the removal of soils from some areas of the palm grove to create terraces in other areas could explain the occurrence of weakly sorted deposits in which fine silts are mixed with gravel >2 cm, possibly originating from previous episodes of gullying (Group PS.3). Moreover, once soils are created, pedological development such as bioturbation can mix various strata together, as well as irrigation which can leach fine particles to lower horizons (Group PS.4). All these practices will partially erase the initial signature of sedimentary sources.

Discussion

Chronostratigraphic results obtained in the Masafi oasis (Purdue et al., 2019) allowed us to classify natural and anthropogenic deposits and to draw a first picture of oasian landscapes for the last 18 ka. Confronted with field observations, the grain size and mineralogical analyses of these deposits allow us to clarify 1) their depositional mode and their origin, providing a much clearer aeolian and hydroclimatic framework; 2) anthropogenic disturbances such as manuring and ash addition. The results highlight the dominance of wind dynamics and aeolian sedimentation for the last 18 ka in the oasis and its watershed, with aeolian sands of different origin depending on regional climatic patterns. Periods of increased water availability at the local scale have allowed for the remobilisation of these sands in the oasis, and their exploitation for agricultural purposes. These results allow us to propose a source-to-sink model of aeolian transport in the al-Hajar Mountains from the Late Pleistocene to the Late Holocene.

Diachronic evolution and regional significance of sediment origin, deposition and transformation

Late Pleistocene to Early Holocene

The Late Pleistocene deposits found within the oasis (basal parts of TP C and D, ~18 ka) correspond to pedogenized silt loams and loams (Group PS.4). They are composed of quartz, quartzite and serpentine, as well as exogenous large micritic nodules cemented around quartz grains (Group M.1). This suggests that local sediments are mixed with quartz-rich deposits later cemented in the upstream part of the watershed and finally remobilized by hydric processes. This mineralogical group resembles the relict palaeodunes of the Early Pleistocene Madinah Zayed Formation, identified in the northern Rub’al-Khali along the Arabian gulf coast, and composed of deflated Miocene sandstones and Quaternary siliciclastic palaeodunes (Farrant et al., 2015, 2019). These dunes stabilized and cemented during the pluvial intervals of the MIS 7, MIS 5 and early MIS 3. We can then propose that the same process occurred within the mountains, with north-westerly winds (Preusser, Radies & Matter 2002) forming pockets of quartz-rich aeolian deposits within the watersheds during dry intervals (MIS 8, MIS 4) (Figure 6), later remobilized with autochthonous coarse sands during drainage periods.

The Early Holocene deposits found in the oasis (basal part of TP B, 11.2–9.2 ka and TP E, 9.2–7.4 ka) show a progressive change in mineralogical composition. These deposits are silt loams to sandy loams (Group PS. 3 and 4) interpreted as remobilized aeolian fine sands and autochthonous coarse sands. The deposits are rich in quartz, olivine and serpentine, with a low concentration in calcite and an average concentration in micrite (Group M.3). Based on near-by reference deposits, we can attest that these deposits correspond to two allochthonous mineral assemblages resulting from regional wind transport, later remobilized by hydric processes or mixed together through bioturbation processes. While the presence of quartz reminds Late Pleistocene deposits composed of siliclastic minerals, the increase in carbonate minerals resembles the Late Pleistocene to Holocene carbonated palaeo-dunes of the Ghayathi formation (Farrant et al., 2015, 2019). These palaeo-dunes are the result of the deflation of carbonated alluvial sediments of the Tigris-Euphrates Rivier Systems deposited in the Gulf and exposed to the NW-SE Shamal wind erosion during periods of low water levels. These dunes accumulated during the MIS2/LGM, stabilized and were remobilized during the Early Holocene Humid period (~10 ka) (Farrant et al., 2015, 2019; Garzanti et al., 2013; Lambeck, 1996), with remaining pockets of older siliclastic aeolian fine sands.

Late Holocene up until today

From the Late Holocene up until today, the oasis has trapped sediments of various origins, depending on regional environmental changes (rainfall, winds, vegetation cover) and local land use (irrigation practices, cultivated species, land clearing and pastoralism, abandonment and recovery). Four diachronic trends can be distinguished.

1- The onset of anthropogenic activities in Masafi is dated from the Iron Age, around 2800 cal yr BP (Charbonnier et al. 2017b; Purdue et al. 2019). In the core oasis (TP C, D), agricultural activity directly develops on quart-rich aeolian sands (Group M.1). East of the oasis, a shift in the mineralogical assemblage is recorded around 2700 cal yr BP with an increase in calcite (Group M.4, TP B) and coarse local harzburgite inputs remobilized by runoff water channelling practices or gullying. The high content in fine silts suggest these deposits were manured, probably with ashes (Group PS. 5).

2- The next phase, dated between ~2380–1860 cal yr BP, was interpreted in the field as non-cultivated (Purdue et al. 2019). Fine sediments are represented by a series of sandy loams composed of calcite-rich aeolian fine sands (Group M.4 in TP B and C), autochthonous coarse sands (Group PS.2 in TP C), presenting traces of soil development (Group PS.4 in TP D) and sealed by gully deposits (TP C and D). Despite a regional phase of aridity recorded between 250 BCE-25 CE (Fleitman et al., 2022), our sedimentary record attests of active torrential sedimentation, probably as a result of persistent orogenic precipitations.

3- Clear changes are recorded between ~1860–550 cal yr BP (Late PreIslamic, Sasanian and Islamic Periods). Scattered deposits are dominated by calcite-rich aeolian fine sand with a clear reduced auxiliary input (Group M.4, TP C). Interpreted in the field as anthroposoils (Facies 4b), they are pedogenized and probably manured (Group PS. 4 in TP C and D). The absence of coarse local minerals in the deposits raises the hypothesis of direct wind powdering. This shift in sediment deposition is in accordance with two periods of aridification recorded in the Hoti cave and recently dated between 480–900 CE and 1050–1300 CE (Fleitman et al., 2022).

4- After 550 cal BP, the occurrence of mixed aeolian fine sands (Group M.3, TP C) rich in centimetric gravel (Group PS 2–3 in TP C, D and I), interpretated in the field as anthroposoils (Facies 4e), suggests sediment mixing probably associated to the restructuration of the oasis and the digging of new terraces (Purdue et al. 2019). The upper part of TP E also supports this hypothesis. On the surface, partly abandoned agricultural layers are still composed of calcite-rich aeolian sands (Group M.4, TP C) but they also contain a higher proportion in silts (Group PS.4, TP C and I) as a result of agricultural activities, manuring and soil development as well as in situ wind-blown particles (Group PS.1, TP I).

These results show that connectivity with the catchment was maintained from the Iron Age and up to the change of era. After this date, in situ aeolian sedimentation followed by increasing soil displacement all point to a reduction in lateral inputs from the slopes. Shifting hydraulic strategies such as reduced water channelling and the development of underground water use, as suggested by the discovery of only one qanat dated from the 17th century CE (Charbonnier et al. 2020), could explain this shift.

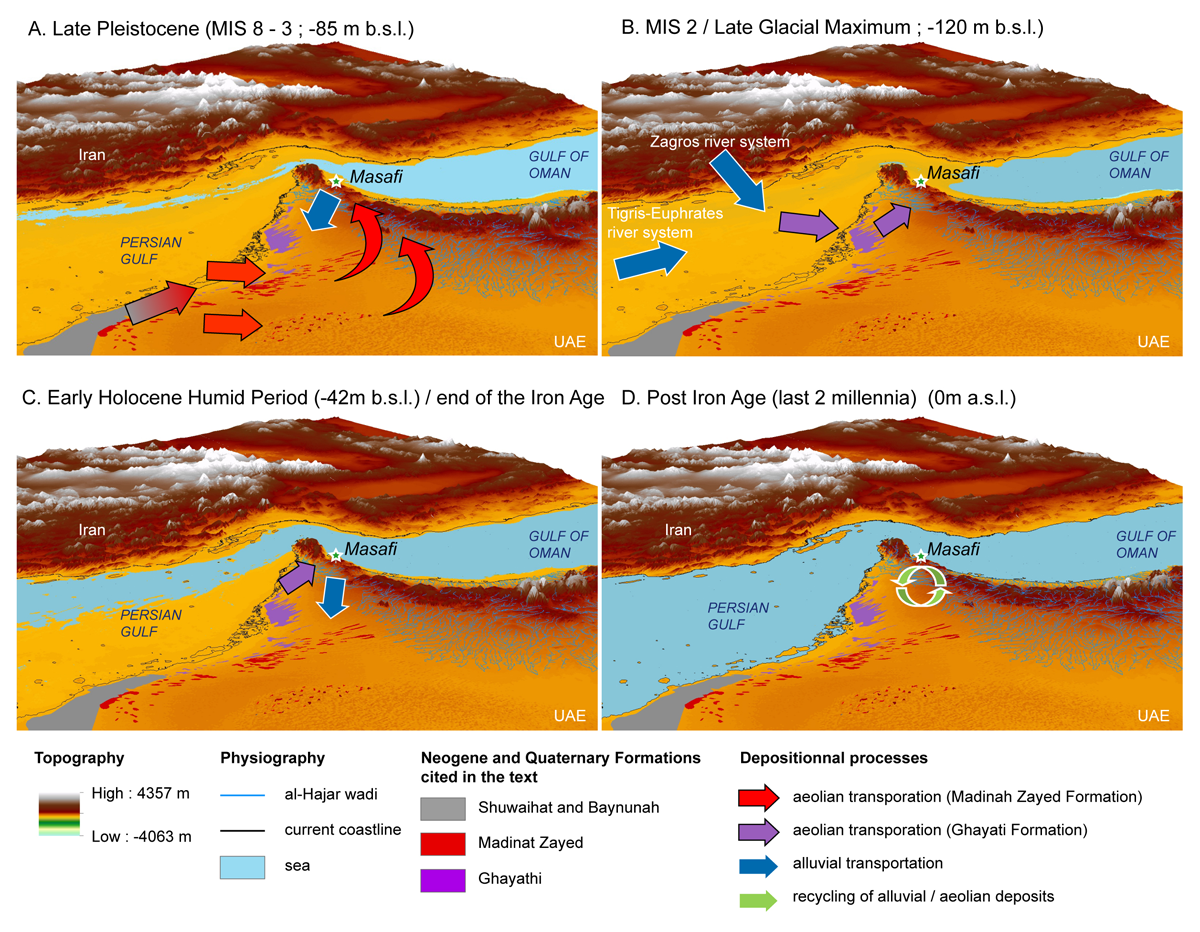

Beyond source to sink analysis and sediment cascade

Our results demonstrate that wind erosion, through its capacity to cause sediments to move upslope or to transport them in suspension, sometimes over very long distances, escape the categories proposed by the source to sink analysis and by the sediment cascade studies (Cossart 2006; Nyberg et al. 2018). These research paradigms are indeed insufficient to account for the mobility of sediments in the Masafi oasis, partly deposited directly by wind, partly stored first on upstream slope, then remobilized, redeposited and displaced by anthropogenic activities. Four regional scale dynamics can be put forward (Figure 8).

Figure 8

Synthesis of depositional processes and model of source-to-sink dynamics in southeast Arabia. A: see Waelbroek et al. 2002 for sea-level – average depth. B: see Lambeck, 1996 for sea level changes and Farrant et al. 2019 for the location of the Tigris sediment pathway. C: see Lambeck, 1996 for sea level changes.

1- Late Pleistocene quartz-rich deposits were identified at the base of the sedimentary sequences in Masafi. Possibly transported over long distances from the Rub’al-Khali, these deposits initially originate from the deflation of the siliciclastic Shuwaihat and Baynunah fluvial formations coming from the Arabian Shield south-west of the Arabian Peninsula (Farrant et al. 2019). Their occurrence in the al-Hajar mountains tends to indicate dry conditions. However, identified under the shape of quartz particles cemented in secondary micritic carbonates, they indicate that these sediments were subject to later cementation processes in the watershed under humid conditions and were remobilized even later during runoff events (Figure 8A and B).

2- Early Holocene aeolian deposits in Masafi are comprised of micritic grains, which originate from the Gulf, itself fed by the coastal rivers from the Zagros and Tigris-Euphrates-Karun system (Farrant et al. 2019; Garzanti et al. 2003, 2013). Temporarily stored in the Gulf, remobilised during periods of low water level, deposited in the watershed of Masafi and remobilized in the oasis during runoff events, these deposits have a complex sedimentary story but testify of the hydrological and sediment connectivity in the watersheds (Figure 8C).

3- Most of these aeolian deposits compose the agricultural sequence of the oasis. At the early stages of agriculture in the oasis, during the Iron Age, active runoff processes still remobilize aeolian calcite-rich deposits in the watershed indicating available water and maintained connectivity between the oasis and its watershed. The presence of lateral water and sediment supply is recorded up until the change of era.

4- For the last 2 millennia, reduced local sedimentary inputs associated with increasing in situ aeolian sedimentation and soil displacement indicate a decreasing sedimentary connectivity between the oasis and its watershed. We suspect that decreasing water resources as a result of climatic constraints could have led to shifting water management strategies and reduced sediment supply (Figure 8D).

Conclusion

Sedimentological records in the oasis of Masafi (al-Hajar mountains, UAE) cover a timespan of more than 18,000 years, from the Late Glacial Maximum to our days. Due to its location and hydrogeology, this oasis acted as a sediment trap and as such is a unique climatic and palaeoenvironmental archive. However, the study of oasian sedimentary sequences requires great caution as they record regional climatic signals, local hydrogeological ones, the reworking of older deposits and local anthropogenic activities. The importance of this mixed signal while working on sedimentological records has already been emphasized in the context of palaeolake/wetlands studies (Parton et al. 2018) and it appears that it is the same when working in oasian contexts. Based on previously published stratigraphic sequences providing a broad history of the construction and management of the oasis through time (Purdue et al. 2019), we propose in this manuscript a combination of geomorphological surveys at the watershed scale, mineralogical analysis and grain size studies, to better extract the palaeoenvironmental signature of these deposits. Our results reveal a complex morphogenetic system and highlight that the deposition of Late Pleistocene loess from the Rub’al-Khali and from the Gulf region were the dominant sedimentary processes in the catchment. While in situ wind powdering probably occurred, these aeolian pockets were remobilized by hydric processes towards the oasis both during the Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene. During the Late Holocene, the hydric reworking of local and aeolian deposits stored on the slopes during the previous phases still prevails as a result of runoff water channelling and gullying events around the first millennium BCE (Iron Age, Pre-Islamic Period). However, increased aeolian activity at the turn of the era in parallel with a reduced local sedimentary input suggest a disconnection between the oasis and its watershed, raising the hypothesis of shifting hydro-agricultural water management practices, maybe as a result of decreasing water availability and climatic constraints. The results provided by this study underline the complexity of hydro-sedimentary processes and wind dynamics in arid environments. The approach developed here could be extended to other oases in the al-Hajar mountains in order to observe whether the trends identified in Masafi corresponds to regional or local ones.

Additional Files

The additional files for this article can be found as follows:

Supplementary File 2

Field Facies defined in Purdue et al. 2019. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/oq.143.s2

Supplementary File 5

Grain size results, typology and confrontation with field Facies published in Purdue et al. 2019. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/oq.143.s5

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the Fujairah Tourism and Antiquities Authority, and especially Ahmed al-Shamsi, Saeed al-Semahi, and Salah Ali Hassan for their support, which enables us to carry out our study of Masāfī oasis. We deeply thank Anne Benoist and Julien Charbonnier, Directors of the Masafi operation in the framework of the Mission Française aux Emirats Arabes Unis (Dir. S. Méry).

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Author contributions

Investigation, data collection, analysis, conceptualization and writing were done by all the authors.