1. Introduction

The ancient oasis of Salūt and Bisya, located near Bahla in central Sultanate of Oman (Figure 1), boasts a remarkable palimpsest of archaeological remains, spanning Southeast (SE) Arabian protohistory from the EBA (c. 2500 BC) to the late pre-Islamic period (pre-Islamic recent = PIR, c. 100 AD) (Degli Esposti 2015; Degli Esposti et al. 2019). Later evidence suggests several phases of Islamic occupation, while occasional lithics hint at an earlier human presence, possibly during the Palaeolithic and Neolithic periods (Degli Esposti, Condoluci & Phillips 2018; Degli Esposti et al. 2018a). This situation is not unique in central-northern Oman. Several similar oases dot the western foothills of the al-Hajar mountain range, while thicker alluvial deposits obscure archaeological remains in the eastern part. However, there is arguably no other oasis in the wider region where archaeological investigation has implemented such an extensive programme of survey, stratigraphic excavation, and geoarchaeological study to sites covering such an ample temporal span.

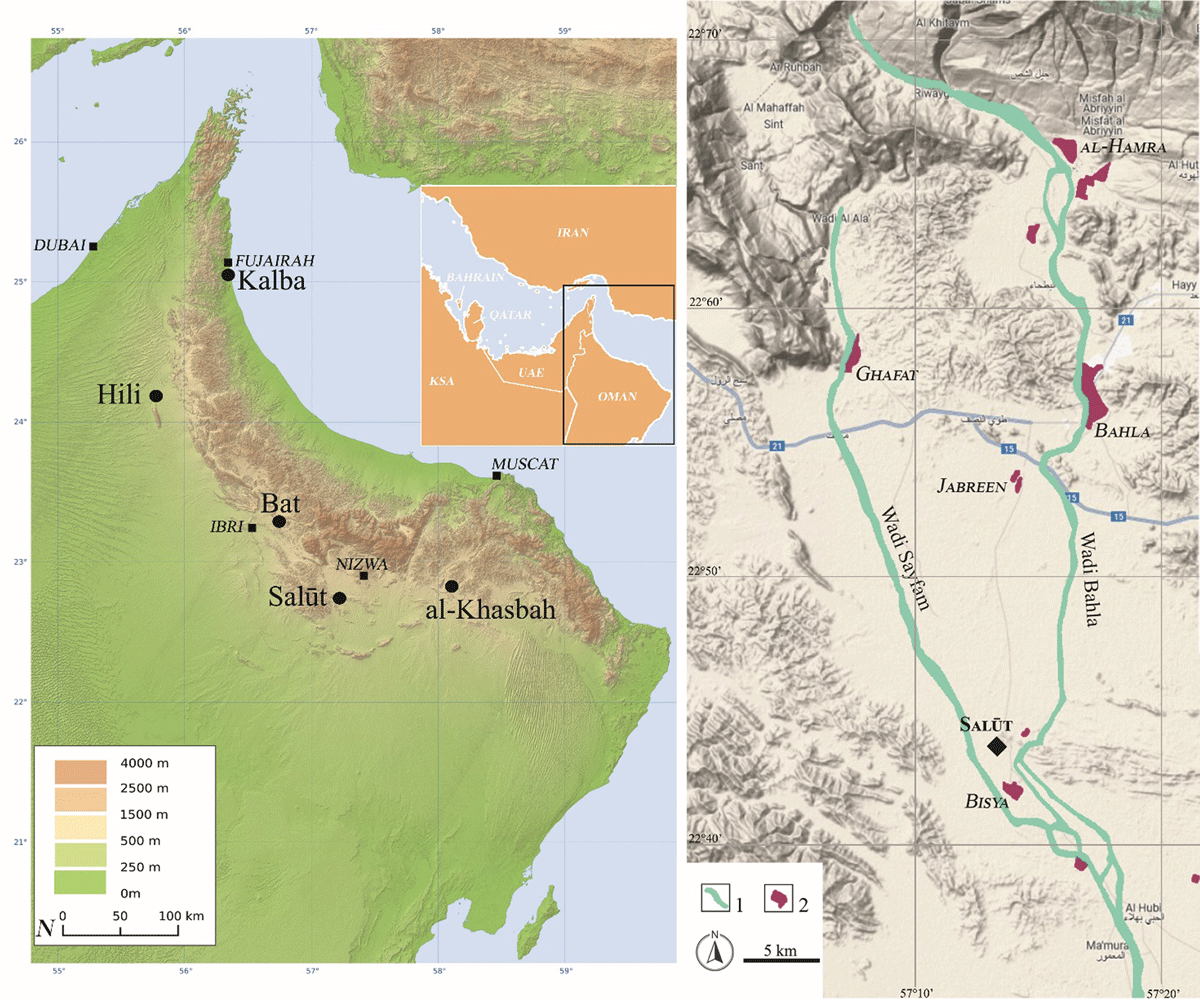

Figure 1

General and regional map. A) The location of Salūt and other main EBA sites in southeast Arabia (modified from Physical location map of Oman by Carport/CC BY-SA 3.0); B) the position of Salūt near the confluence of Wadi Bahla and Wadi Sayfham. 1) Main wadi channel; 2) modern cultivated areas (base relief map: © Google Maps 2024; details adapted from Orchards & Orchards 2007: plate 3).

The oasis of Salūt and Bisya developed on the plain to the east of Wadi Sayfam, near the point where it joins the larger Wadi Bahla flowing south. The core of the oasis in flanked to the northeast by the reliefs of Jabal Hammah (Zerboni et al. 2021), dotted by graves of different periods (e.g. Condoluci & Degli Esposti 2015). Several factors made this area a favorable location for human settlement supported by agricultural production (Degli Esposti et al. 2018a: 24–25). A dense network of ditches visible both on satellite imagery and by field walking testifies to past intensive agriculture on the Wadi Sayfam alluvial plain. Additionally, a more recent grid of small field walls suggests their potential role in mitigating occasional flash floods during heavy rains. The present-day landscape, however, is dominated by an arid savannah and agriculture is limited to isolated farms where small palm groves and crop plots are water-fed by means of engine pumps drawing from deep wells. Local informants claim these wells reach down slightly less than 30 m (90 ft.).

The area was first surveyed in the 1970s, when main sites were reported which date to the EBA or the IA (Humphries 1974: 49–77; Hastings, Humphries & Meadow 1975: 9–55; de Cardi, Collier & Doe 1976: 164). Between 2004 and 2019, the Italian Mission To Oman (IMTO – University of Pisa) conducted excavations and surveys in the area under the auspices of the now Ministry of Heritage and Culture (MHC) of the Sultanate of Oman. The works first dealt with the excavation of the outstanding fortified sector of the IA site of Salūt (Husn Salūt, see Avanzini & Degli Esposti 2018), prominent within a dense network of contemporary sites (Condoluci, Phillips & Degli Esposti 2014; Degli Esposti 2015). The wider settlement directly associated with Husn Salūt, dubbed Qaryat Salūt, was subsequently discovered and partially investigated (Tagliamonte & Avanzini 2018; Degli Esposti 2021). Another key component of the rich archaeological record of the area is the typical 3rd millennium (i.e., EBA) tower site of Salūt-ST1, located in the plain 300 m to the northwest of Husn Salūt (Degli Esposti 2011, 2016). Several EBA and IA graves, including a PIR necropolis were also investigated (Degli Esposti et al. 2019, 2021). All the sites excavated by the IMTO are now included in the Archaeological Sites of Bisya and Salut Park, promoted by the MHC.

In 2007, the Department of Earth Sciences of the University of Milan was appointed with the geomorphological and geoarchaeological research constituting an essential component of the project (Degli Esposti et al. 2018a), with a specific focus on water availability and management through time (Cremaschi et al. 2018), mineral resources, land use, prehistoric occupation of the area, and rock art (Degli Esposti, Cremaschi & Zerboni 2020; Zerboni et al. 2021). This involvement led in 2021 to the creation of the Salūt and Bisya Archaeological Mission (SBAM, University of Milan), that restarted works within the core area of the park. Additional data on the oasis will come from the awaited publication of the French excavations at the nearby EBA tower of Salūt-ST2, while the wider area is now the subject of the research carried out by the French Archaeological Mission in central Oman (Sauvage et al. 2022; Jean et al. 2023).

The focus of this study is synthesizing our knowledge of the hydraulic structures (wells and ditches) associated with the EBA tower of Salūt-ST1 and Salūt-IA. This comprises the results of the survey of the surrounding area to trace the remains of underground (the aflaj) and open-air channels to find evidence of their age. The main aim was the reconstruction of the diachronic changes in water availability and the strategies adopted by local communities to cope with them, tracing the beginning of a long-lasting tradition of sustainable management of water reservoirs in the oasis.

2. Pre-Islamic Hydraulic Features in the Oasis of Salūt

2.1. The Early Bronze Age: the tower of Salūt-ST1

Work at the site between 2010 and 2015 prioritized large-area excavation over vertical stratigraphy, the only practical strategy due to the significant impact of repeated cycles of erosion and redeposition on the archaeological record. Intact pre-Islamic deposits are almost exclusively found within negative features (i.e., excavated in ancient times), primarily those related to water management.

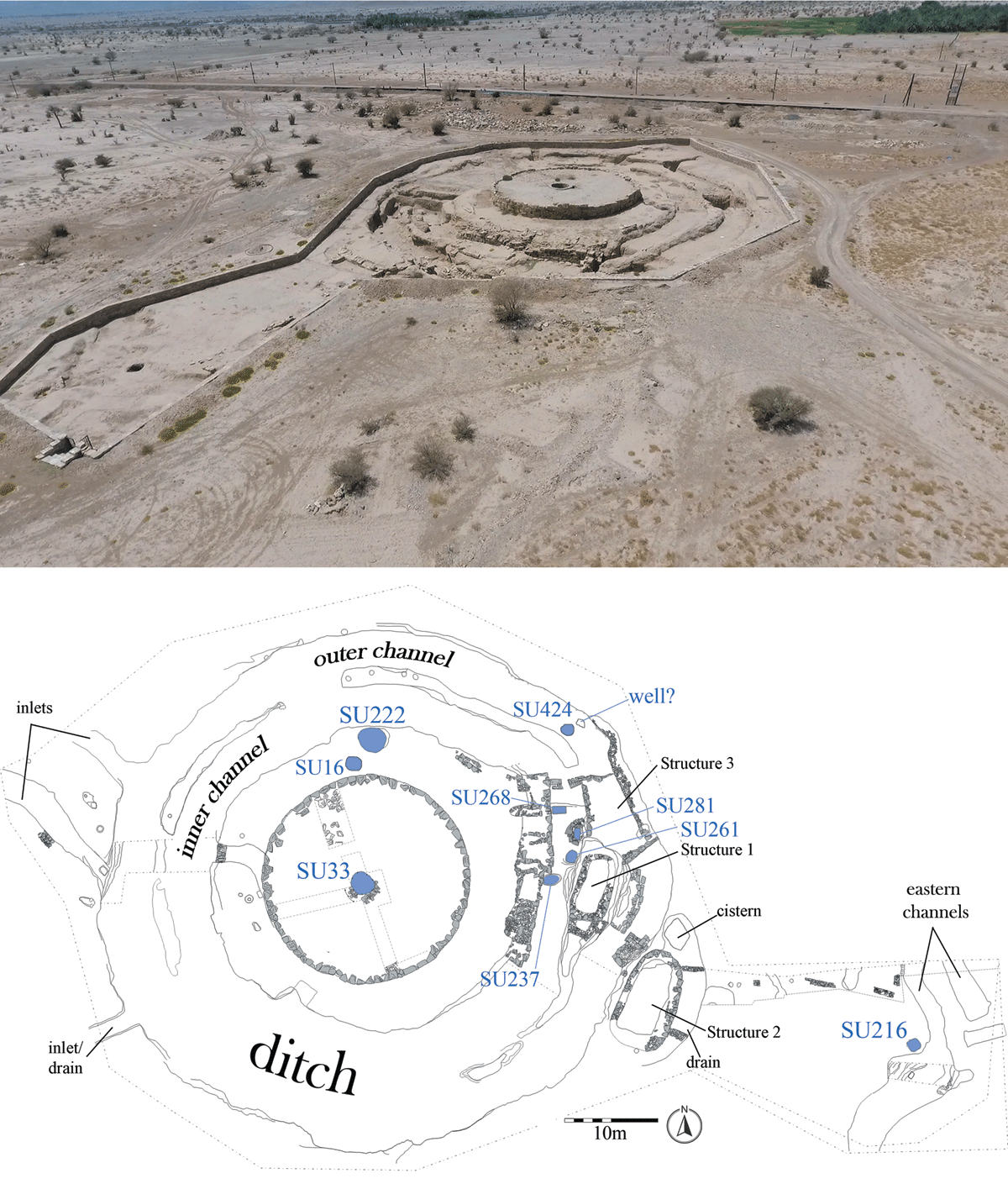

The main monument at the site is a stone tower, 22 m in diameter, with a remaining height of only about 2 m (Figure 2). This structure is one of three similar monuments located in the local alluvial plain, approximately 0.6 and 1.8 km away from ST1, respectively. While excavations have been conducted at both sites, the results remain unpublished.

Figure 2

The EBA “tower” site of Salūt-ST1. Top: bird’s-eye view; bottom: plan with indication of the main hydraulic features discussed in the text (see Figure 5 for the plan location). SU = Stratigraphic Unit.

As is typical for this type of monument, characteristic of the EBA in SE Arabia, the tower is surrounded by a large ditch and hosts a well within its circular wall (Figure 2). The ditch is 11 to 13 m wide and comprises two concentric channels separated by a bedrock septum left untouched during excavation. However, the septum is absent in some places, allowing for communication between the channels. Both channels are approximately 4.5 m wide and 3 m deep, while the septum has an average width of 1.3 m. The overall circumference of the ditch is 55.5 m. It has a flat bottom and its sides are sub-vertical, transitioning to concave in areas affected by erosion.

The impressive water infrastructures connected with the tower also include three inlets located in the western part of the site, thus toward the bed of Wadi Sayfham, currently 1.5 km west of the site. On the opposite side of the tower, some 30 meters east of the main ditch, run two other EBA channels (“eastern channels”) not connected with it. Finally, a cistern collected water from a drainage built around an auxiliary stone structure (Structure 2) built on the edge of the ditch.

The complete excavation of a large portion of the ditch, east of the tower, revealed the presence of 4 or maybe 5 wells dug from its base, while another well was excavated in a later moment and cut through the ditch infills. The investigation of four of these wells showed they all reached a similar depth between 1.5 and 1.8 m from the ditch’s flat base (Degli Esposti 2016: 672; Degli Esposti, Cremaschi & Costanzo 2024).

Based on two radiocarbon dates from deposits accumulated inside the ditch (Degli Esposti, Cremaschi & Costanzo 2024; see Figure 8 and Table 1) and parallels for the ceramic assemblage, the EBA hydraulic structures at Salūt-ST1 can be dated into the second half of the 3rd millennium BC. The site was likely abandoned around 2100/2000 BC, as no material datable to the Wadi Suq period (i.e., Middle Bronze Age, c. 2000–1600 BC) was discovered.

Table 1

Available radiocarbon dates for the sediments inside the main ditch at Salūt-ST1. Calibrated using OxCal v4.4.4 (Bronk Ramsey 2009) and the INTCAL20 atmospheric curve (Reimer et al. 2020). See Figure 8 for the relative position in relation to the general stratigraphy inside the ditch.

| LAB CODE | MATERIAL | UNIT/CONTEXT | 14C DATE (BP) | PRE-TREATMENT | MEASUREMENT TECHNIQUE | δ13C | pMC | 2σCALIBRATED DATE (BC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14Fi2250, 14Fi2255, 14Fi2258 | Charcoal from small dump | Unit 2/ SU 55 | 3830 ± 35 | ABA procedure | graphitisation/ combustion | 62.10 ± 0.25 | 2455 (6.3%) 2417 2410 (85%) 2196 2170 (4.2%) 2147 | |

| UGAMS 27659 | Charcoal from small fireplace | Unit 3 (base)/ SU 419 | 3890 ± 25 | –26.22 | 2464 (95.4%) 2294 |

2.2. The Iron Age: Salūt-IA and the surrounding archaeological landscape

Salūt-IA, situated 300 m east of ST1, is composed of a fortified core hosting communal and likely ceremonial buildings erected above a low hill (Husn Salūt; Degli Esposti & Condoluci 2018), surrounded by a settlement that comprises a terrace system covering the same hill and large sectors extending onto the surrounding plain (Qaryat Salūt; Degli Esposti 2021). Within the site, hydraulic features of different types served different functions including water supply, harnessing, and possibly storage.

Several stone-built drainage channels are found in the alleyways of the settlement and between the terraces along the hillslopes, meant to funnel excess runoff from heavy rains to prevent gullying and erosion.

Wells were surely exploited in this period. Only one, however, was identified and partially excavated in the western area of the settlement, nested within later structures (W27, Figure 5). Local tradition has it that the main monumental tower of Husn Salūt, significantly projecting onto the plain, hosted a well but excavation there was stopped after the discovery of a series of plastered tanks, likely of Islamic date (Degli Esposti, Condoluci & Phillips 2018).

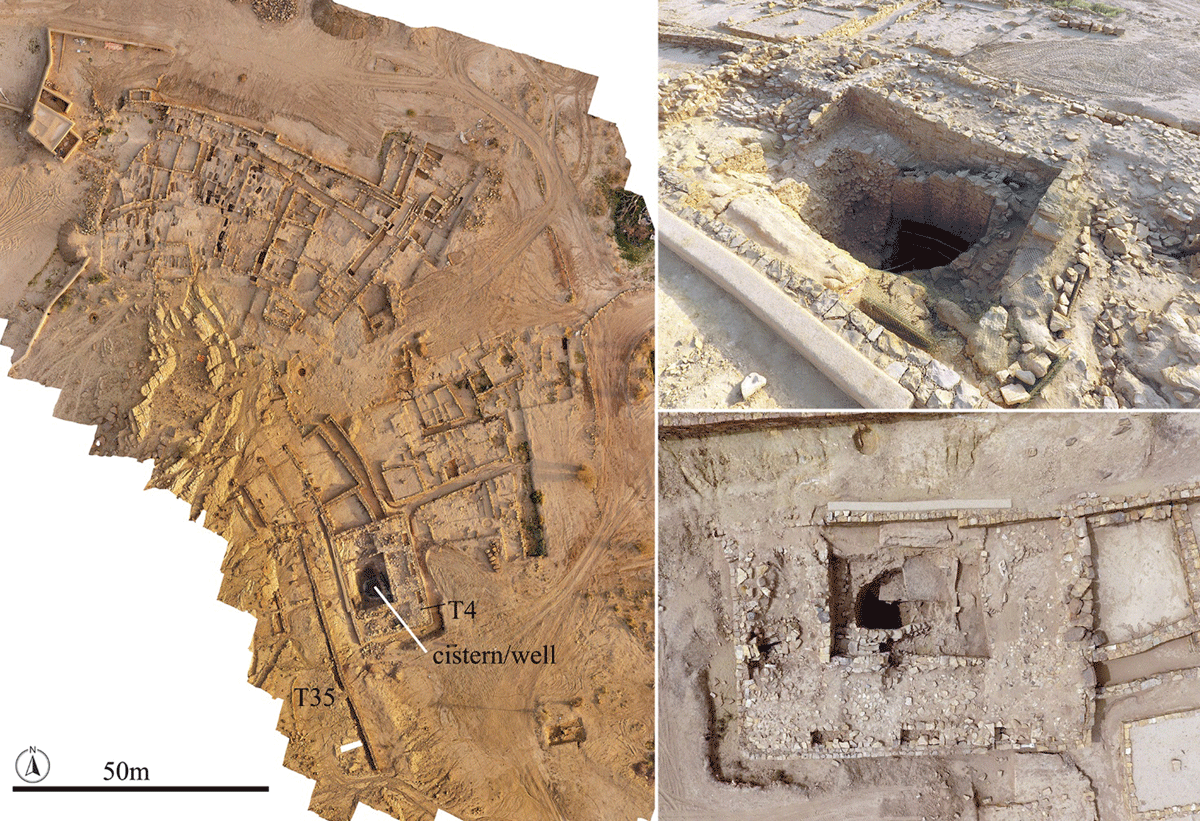

The most impressive water-related structure is the substantial cistern nested inside a monumental terrace erected along the eastern footings of the hill, Terrace 4 (Figure 3). The cistern comprises a circular stone wall lining its shaft, cut through the plain’s sediments against the inclined bedrock of the hill that from a certain depth constitutes the western side of the cistern. After removal of the massive wall fall that obliterated its upper portion, the infill of the cistern was excavated down to c. 7 m from the surviving crest of its wall. Unfortunately, coring could not be performed before the interruption of the work but it is planned for the restart of the investigations. The cistern, which could collect rainwater from the hill slope, might have also served as a well intercepting the aquifers buried in the plain. To our knowledge, it is the largest feature of this kind discovered so far in SE Arabia (Degli Esposti 2021).

Figure 3

Qaryat Salūt. Left: orthorectified view of the eastern area of the site, with the location of the huge cistern/well; right: two views of the cistern/well.

The settlement of Salūt-IA was established around 1300 BC at the latest, with increasing evidence supporting an even earlier date and indicating that the fortified and the residential areas were part of a single project (Degli Esposti et al. 2018b; Degli Esposti 2021:153). The huge cistern in Terrace 4 also belongs to the initial phase of construction. Indeed, some recent radiocarbon dates, including those associated with the cistern construction, would lend further support to the hypothesis of an even earlier foundation of the site.

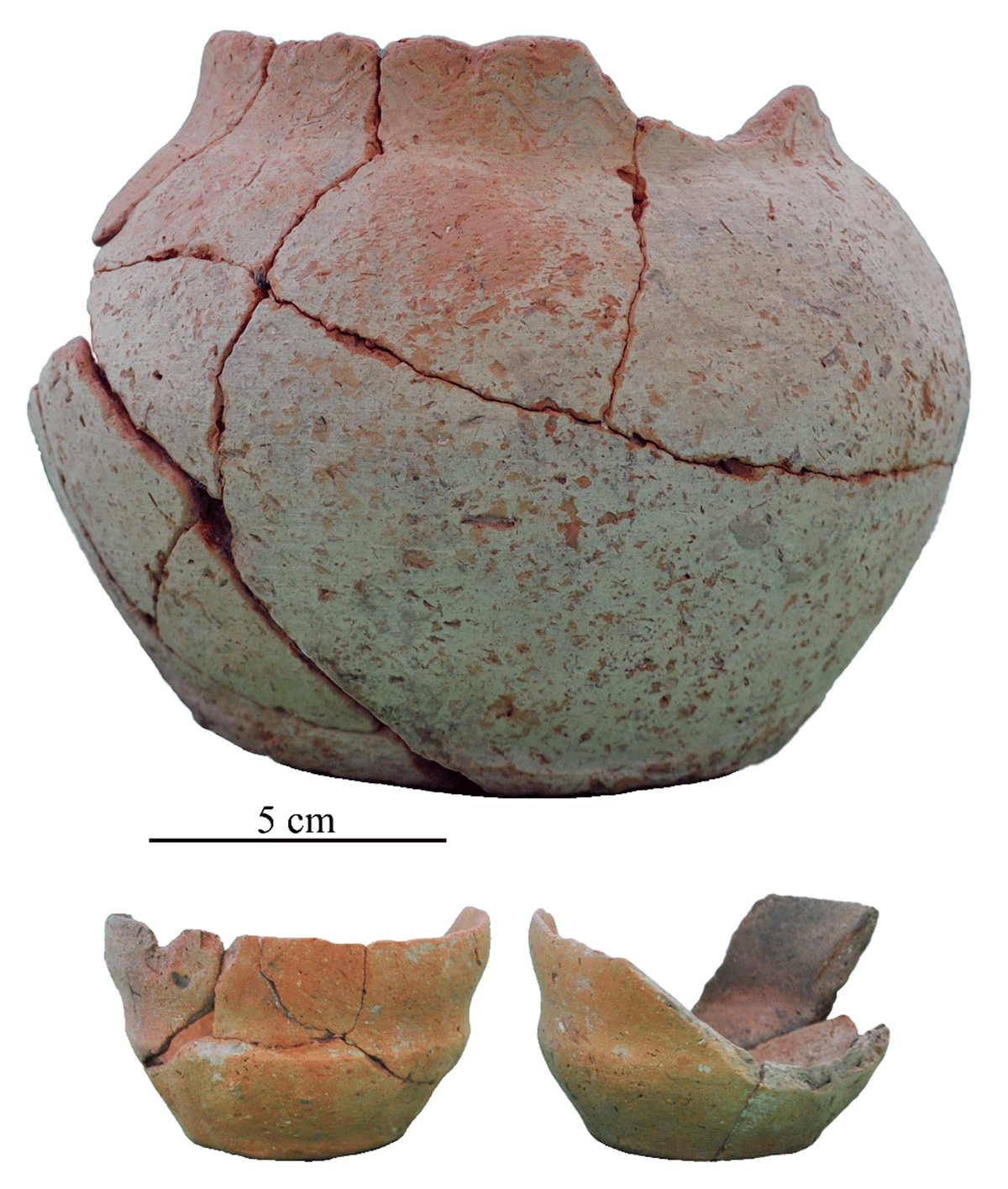

Data about IA water harvesting also came from Salūt-ST1. The central well (SU33 – Figure 2) was reused during the IA and equipped with a new stone-made well head; dumped pottery comprising IA III materials (c. 650–300 BC) marks the end of its use (Degli Esposti 2011: 195–196). Another well (SU216) was identified adjacent to the two eastern channels, east of the tower. It was excavated to a depth of c. 7 m. It has a noticeably different, square-shaped and smaller shaft than the central well of the tower. Such a shape, and the fact it only yielded IA pottery (Figure 4) suggest it was first excavated during the late 2nd–1st millennium BC.

Figure 4

Iron Age pottery. Complete shapes discovered inside well SU216.

Another well (SU222, Figure 2) located immediately outside the tower’s ring wall was surely active during the IA but limited investigation prevented an assessment of the date of its excavation. Its dimensions and shape are consistent with the tower’s central well and could suggest similar construction date. Adjacent to it, well SU16 (Figure 2) only yielded Islamic pottery in the limited excavated part (unpublished data).

The emergence of the major site of Salūt-IA at the core of a network of smaller sites mirrors a remarkable human density (Phillips, Condoluci & Degli Esposti 2010; Condoluci, Phillips & Degli Esposti 2014), which surely relied for its subsistence on the extensive agricultural exploitation of the alluvial plain although facing the challenge of flash floods (Degli Esposti et al. 2018a: 30). To partially overcome this issue, the slopes of the hill hosting Salūt-IA were extensively terraced, as were other hills bordering the plain,1 possibly to host small agricultural plots. To date, this is one of the oldest pieces of evidence in Arabia for terracing, further suggesting an early attempt to contrast soil loss.

One of the main achievements allowing the agricultural exploitation of the land was the introduction of the system of underground water channels know in this part of Arabia as aflaj (sing. falaj), which was demonstrated elsewhere to be surely in place at Salūt by the mid-5th century BC (Cremaschi et al. 2018) but the origin of which might well date back to the beginning of the 1st millennium at the least, consistent with the IA demographic boost (Magee 2014: 215–222). This development marked the final step in the development of the desert oases landscape which characterised the region just until the introduction of modern water-pumping technologies.

3. Geomorphological Setting

The ancient oasis of Salūt and Bisya is located near the confluence between Wadi Sayfam (to the east) and Wadi Bahla (to the west), in the Dahiliyya (al-Dāḫilīyah) region of the Sultanate of Oman (Figure 1). To the north, the study area is framed by the tectonized harzburgite and intrusive peridotite and gabbro reliefs of the Mid-Late Cretaceous Samail Ophiolite, while limestone and radiolarite formations of Permian to Cretaceous origin bound it to the west and south. The Geologic Map of Oman 100,000, Bahla Sheet (Bechennec et al. 1986) indicates the bedrock of the region as consisting of a series of sedimentary and igneous rocks.

A system of coalescent, gravelly alluvial fans stretches out from the northern ophiolitic hills and runs parallel to Wadi Bahla, merging with the plain at the eastern margin of Wadi Sayfam. The remnants of older fluvial deposits were incorporated into this fan system. They consist of different dark-varnished gravel bodies which can be attributed to different stages in the evolution of the system, based on the different degrees of rock varnish (Oberlander 1994; Perego, Zerboni & Cremaschi 2011). In general, the presence of several scatters of Palaeolithic lithics can suggest at least a Middle/Upper Pleistocene age for the deposition of these fluvial units (Beshkani et al. 2017, 2023; Cremaschi et al. 2018: 128).

The alluvial plain of Wadi Sayfam and Wadi Bahla is covered by fine sediments consisting of wind-blown silt and fine sand (desert loess), trapped by bush grassland developed when climate was substantially wetter than today (Cremaschi et al. 2015), partially reworked by fluvial process and weakly affected by pedogenesis. The occurrence of Neolithic scatters of lithics at their base suggests a deposition during the Early Holocene. These sediments are included in the Khabra Formation in the local geological map and correspond to the soils above which Salūt-ST1 and other EBA structures scattered through the plain were erected (see Cremaschi et al. 2018: 125–126, 128) and that sustained cultivations. Below the sediments of the Khabra Formation stand consolidated fluvial sediments through which the cut of the EBA hydraulic structures were visible.

4. Late Quaternary to present-day Climate

Recent rainfall data from monitoring stations throughout Oman define the climate as varying from hyper-arid to arid and semi-arid, with a country average of 117 mm/year and a high inter-annual variability (Kwarteng, Dorvlo & Vijaya Kumar 2009: 605). Variations are also considerable between the different regions due to the diversified topography. Salūt lies to the west of the main al-Hajar mountain range and can be considered part of the interior region, as opposed to the eastern coastal belt of the Batinah and the mountain region itself. Data from the station of al-Hamra, some 40 km from Salūt, indicate an average annual rainfall ranging from c. 55 to 255 mm/year (Fleitmann et al. 2007: 173), but values appear to be also strongly correlated to elevation: the annual rainfall between 1997/2003 at Samail, further away but at the same elevation as Salūt, is 85 mm/year comparing with 167 mm/yr at al-Hamra, almost 300 m higher (Kwarteng, Dorvlo & Vijaya Kumar 2009: Figure 1).

In this area of northern Central Oman, rainfall is caused during winter and spring by Mediterranean frontal systems, while local thunderstorms occur during the summer. Precipitation is more intense during the first months of the year (Weyhenmeyer et al. 2002; Kwarteng, Dorvlo & Vijaya Kumar 2009). Every 5 to 10 years the region is hit by tropical cyclones (Weyhenmeyer et al. 2000).

Holocene climate change in southern Arabia has been investigated using several proxies, from speleothems and Aeolian sediments to lacustrine and fluvial deposits (Fleitmann et al. 2003a, 2007; Parker et al. 2006; Berger et al. 2012; Atkinson et al. 2013).

Climate dynamics in the region are dependent on the interaction between the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) migration and Indian Summer Monsoon (ISM) rainfall belt. The speleothems of the al-Hoota cave near al-Hamra represent a valuable palaeoenvironmental archive that allowed the reconstruction of changing rainfall patterns in northern Oman (Neff et al. 2001; Fleitmann et al. 2007).

Oxygen isotope data (δ18O) from al-Hoota cave speleothems suggest a northward shift of the summer ITCZ and associated ISM rainfall belt during the Early Holocene (10–9.5 ka BP). This led to increased precipitation and water availability in the region. However, the southward migration of the summer ITCZ began around 7.8 ka BP, resulting in a gradual decrease in ISM intensity and duration. While this trend indicates aridification, speleothems from al-Hoota and southern Dhofar reveal short-lived humid periods between 4–2.7 ka BP (al-Hoota), 2.2–1.9 ka BP, and 450–350 years BP (Dhofar – Fleitmann et al. 2003b; 2007).

The possibility of local variations must be considered. A recently published stalagmite record from al-Hoota cave bear witness to a period of low effective moisture from the half of the 3rd century BC to the 1st quarter of the 1st century AD (Fleitmann et al. 2022: 1318), thus diverging from the data from Dhofar mentioned above. At the same time, findings from Masafi, in the Fujairah Emirate (Purdue et al. 2019), suggest a phase of relative humidity between 3.2–1.8 ka BP, partially aligning with the al-Hoota record. Despite this local anomaly, a marked decrease in precipitation is evident around 1.9 ka BP in the al-Hoota record. Similar trends in Dhofar and Socotra speleothems (Fleitmann et al. 2003b; Shakun et al. 2007) further support a general weakening of the ISM in the late Holocene.

5. Methods

The main hydraulic structures identified during the excavations were studied from the geoarchaeological point of view. Several sections were cut through the infills of the main ditch at Salūt-ST1. These were surveyed, studied, and described following established pedological codes. The same methodology was applied to the eastern channels and the excavated wells (specified below), although some were only partially excavated.

The central well of the tower at ST1 was excavated to a depth exceeding 7 m from its opening, but in this case the lateral stratigraphy (the substratum) was not investigated. The IA well SU216, located near the eastern channels at Salūt-ST1 (Figure 2), was excavated to a similar depth. The remaining two wells at Salūt-ST1 (SU16, SU222) and well W37 in the western part of Salūt-IA were only excavated to a depth of approximately 2.5 m (Figure 5).

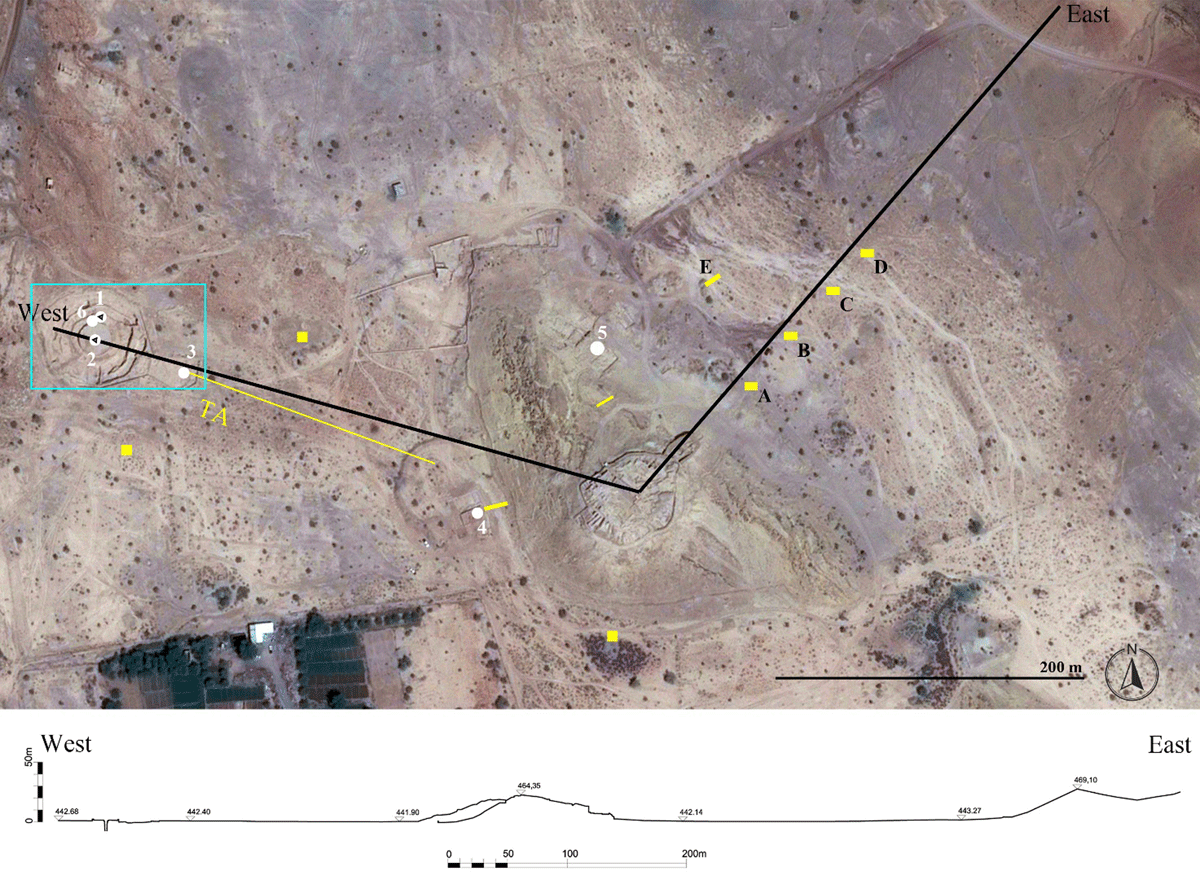

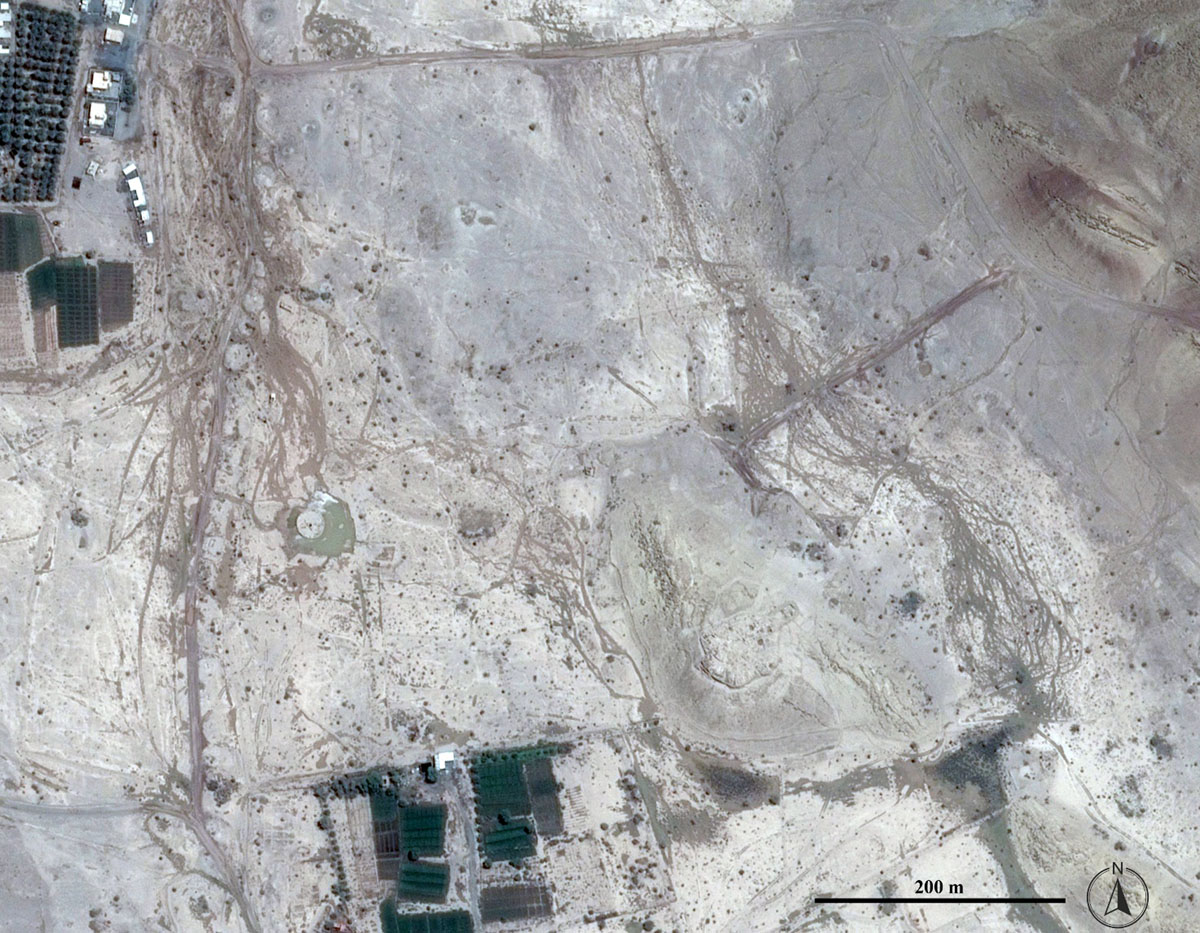

Figure 5

Satellite view (Maps data: Google © 2024 CNES/Airbus, acquired Oct. 2016) and general profile through the modern oasis (topographic survey by A. Massa). Top: location of the wells and cisterns discussed in the text (white numbers; EBA and possibly EBA wells with inner black triangle) and of the test pits excavated in the plain. 1) well SU222; 2) well SU33; 3) well SU216; 4) well W37; 5) well/cistern in Terrace 4; 6) well SU16; A-E) test pits illustrated in Figure 7. Yellow polygons indicate other test pits currently under study, with TA showing the alignment of 12 test pits. The light blue rectangle indicates the extension of the plan in Figure 2 bottom.

These excavations provided valuable evidence regarding the nature and origin of the deposits, enabling the reconstruction of the main palaeoclimatic changes in terms of fluctuation of the water table, as detailed by Degli Esposti, Cremaschi & Costanzo (2024). Additionally, the lithology of the underlying substratum through which these features were cut was investigated in the field.

Over the years, several test pits were dug at various locations across the plain to investigate the characteristics of the waterborne and aeolian sediments that make up the soil cover above the substratum.

Four test pits (A–D) were positioned along a SE–NW transect east of the IA site, between the latter and the Jabal Hammah hills bordering the plain, also known to locals as Jabal Salūt (Figure 5). An additional isolated pit (E) was also included in this area. Other test pits were excavated throughout the plain but they will not be mentioned here as their study is ongoing.

Field observations were complemented by the micromorphological analysis of collected samples, following standard procedures outlined in Degli Esposti, Cremaschi & Costanzo (2024). This analysis allows the reconstruction of the environmental and anthropogenic processes that drove the formation of the stratigraphic sequences (Courty, Goldberg & Macphail 1990; Goldberg & Macphail 2006; Goldberg & Berna 2010).

6. Results

6.1. The geological substratum

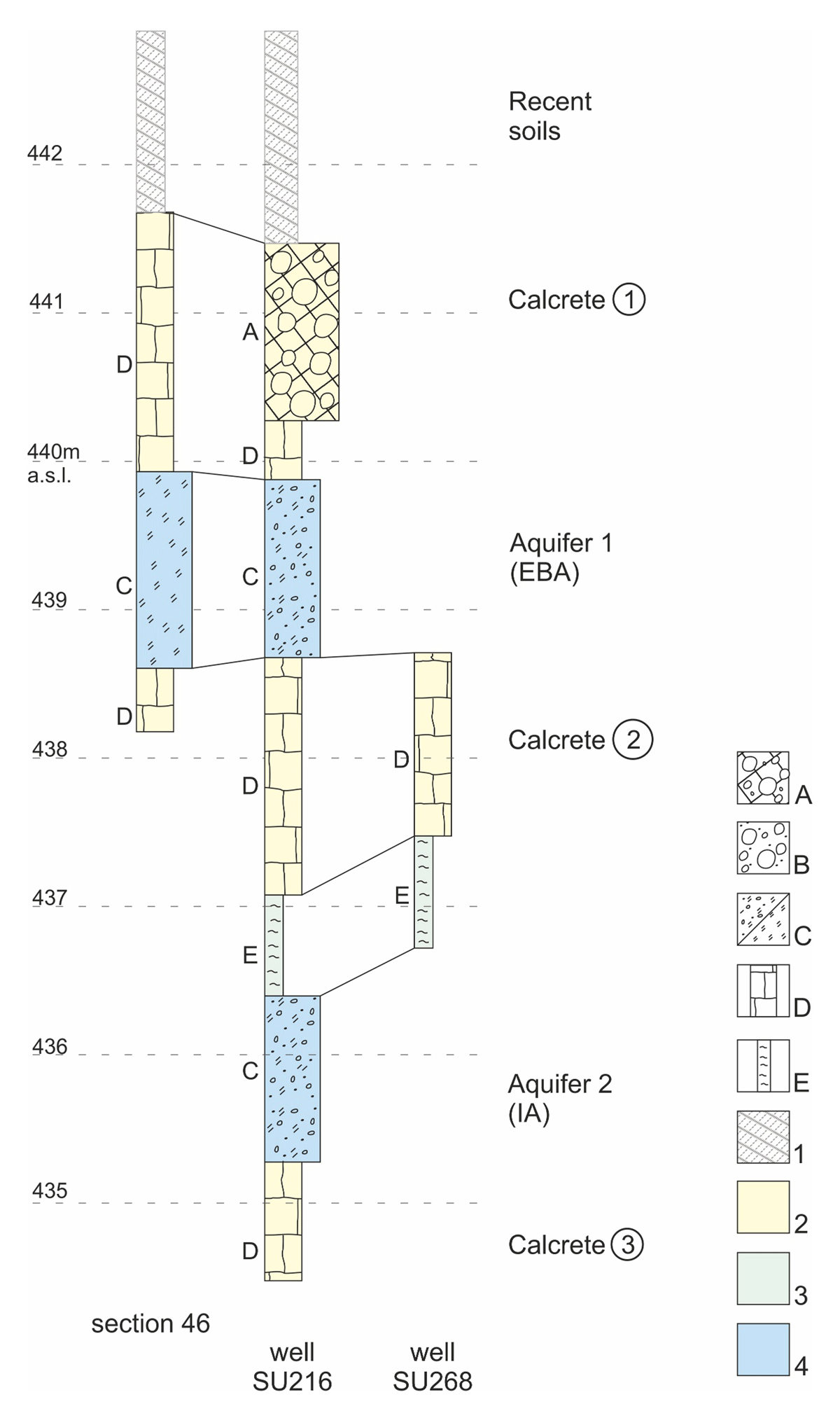

Excavations of various sections of the main ditch, combined with investigations of wells (particularly the IA well SU216) and eastern channels at Salūt-ST1, provided insights into the geological substratum. The sequence (Figure 6) comprises the following units (see Degli Esposti, Cremaschi & Costanzo 2024):

Cemented sand and gravel, represents the upper portion of the calcrete horizon (Bk) characteristic of the alluvial plain buried below the Khabra Formation deposits.

Slightly cemented to loose gravel in a coarse sandy matrix. Only recorded west of the Salūt-ST1 tower, these deposits exhibit poorly developed stratification.

Fine gravel in sandy matrix with a dominant olive grey colour and intense orange brown mottling.

Hardly cemented, olive brown silt and sand (calcrete).

Poorly cemented, green-bluish silt and sand, tapped by the wells dug through the bottom of the ditch.

Figure 6

Illustrative stratigraphic logs of the substratum surveyed in the main ditch at Salūt-ST1, in well SU261, and in one of the wells at the bottom of the ditch (modified from Degli Esposti, Cremaschi & Costanzo, 2024: Figure 3). Keys: A) calcrete on gravel; B) loose gravel; C) mottled loose small gravel and sand/mottled sand and silt; D) calcrete on sand and silt; E) weakly cemented sand and silt; 1) soils in the plain; 2) impermeable layers (A+D); 3) poorly permeable layers E); 4) permeable layers (B+C). See Figure 1 for log location.

Either Units A or D stand at the top of the sequence, underlying the most recent soils (see below), and both constitute the uppermost calcrete horizon (Calcrete 1). The ancient hydraulic structures are cut into this Bk horizon, identified in all the exposed sections, including those left visible at the nearby sites investigated by other missions. It is thicker east of Salūt-ST1 and shallower moving west. Similar units cemented by CaCO3 occur twice at lower depth, defining two additional calcrete horizons (Calcrete 2 and 3).

For the issue of water harvesting and management it is essential to point out that Units B, C and E have the potential to host aquifers, while the remaining ones are impervious to water (aquicludes). Unit E, with its loose silty sand, has the potential of functioning as an aquitard. Currently, all these aquifers are inactive as the water table has dropped to around 30 m from the surface.

Units B and C, forming the uppermost fossil aquifer (Aquifer 1), are entirely crossed by the cut of the main ditch. Well SU216 allowed the identification of a deeper fossil aquifer (Aquifer 2) hosted in a Unit C horizon sandwiched between the Calcrete 2 and 3 horizons, and standing immediately below the poorly cemented silty sands of Unit E. The investigated wells dug from the bottom of the ditch tap into this last Unit.

6.2. The soils of the alluvial plain

Across the alluvial plain surrounding the archaeological sites, a pedosedimentary cover, ranging from 0.8 to 1.6 m thick, buries the underlying calcrete surface. This stratigraphy was observed in several test pits (Figure 7). The uppermost layer consists of a loose, stone- and potsherd-rich (IA to Islamic) sandy loam deposit, likely formed by the deflation of older sediments. This layer is followed by a weakly developed soil horizon characterized by poorly aggregated, pale brown sandy loam containing small charcoal fragments and scattered IA sherds.

Figure 7

Stratigraphic logs from the test trenches in the plain to the east of Salūt-IA (for their location, see Figure 5). Keys: 1) loose sandy loam; 2) pale brown sandy, weakly developed soil; 2bis) fluvial coarse sand and gravel/anthropogenic stone accumulation; 3) calcrete on sand and silt (= Unit D) 4) mottled loose small gravel and sand (= Unit C?); 5) pottery.

An erosional surface marked by a stone line rich in potsherds separates this unit from the underlying B horizon. This horizon is composed of reddish brown, moderately blocky clay loam and contains charcoal and EBA pottery fragments. This soil, however, was only observed to the west of Salūt-IA (Cremaschi et al. 2018: Figure 11). East of it, this unit has been eroded by fluvial activity, resulting in some cases in its replacement by coarse sand and gravel deposits (Trench C, Figure 7).

The base of the entire sequence is defined by the hardly cemented deposits (calcrete) of Unit A of the local geological substratum (see Figure 6). In Trench C (Figure 7), excavation reached the bottom of Unit D, revealing a hydromorphic layer beneath it. This layer may correlate with Unit C identified along the sides of the main ditch at Salūt-ST1, suggesting a large extent of the upper fossil aquifer (Aquifer 1).

6.3. The sedimentary infillings of hydraulic structures

Ancient excavated features represent the only safe stratigraphic archives for ancient levels dated to the EBA or IA. Throughout the plain, the investigated trenches show the presence of an erosional surface coinciding with the upper limit of the Calcrete 1 horizon. A broad terminus ante quem for this erosional surface is provided by the IA materials found immediately above the main ditch’s backfilling at Salūt-ST1, that conversely yielded exclusively EBA materials.

6.3.1. The main ditch at Salūt-ST1

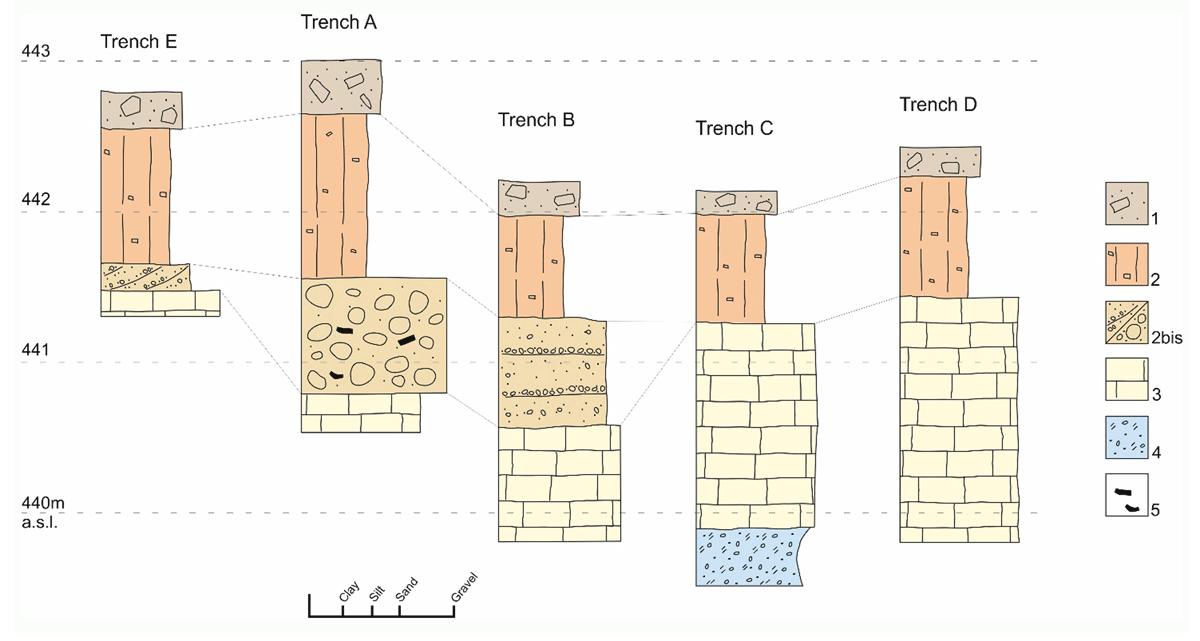

The ditch infills could be associated to four units (Figure 8), top to bottom (Degli Esposti, Cremaschi & Costanzo 2024):

Loose gravel, generally massive but sometimes showing a discontinuous cross-bedding, interspersed on an erosive base with sandy loam sediments that occasionally exhibit a planar stratification. The anthropogenic material is limited to occasional charcoal and minute pottery fragments.

Brown sand and silty loam. Originally showing thin laminations emphasised by concave stone lines, now mostly concealed by bioturbation. Human activity is indicated by hearth intercalated within the deposits, together with scattered charcoal and potsherds. Wavy lower boundary to Unit 3.

Brown, laminated sand and loam. Extensive, thin lamination is also evident at the micro-morphological level. Its colour indicates deposition within a non-hydromorphic environment. Along the ditch’s sides, the unit is enriched by gravel-size material coming from calcrete degradation. Indeed, most of the coarse fraction is composed of calcrete fragments while clasts of limestone and ophiolits are rare, which indicates a limited exogenous supply. Possible ripples also occur. Charcoal and ash lenses, fireplaces (one of which was radiocarbon dated, see §7.1), use surfaces, and probable pottery dumps mirror human activity. The lower boundary towards Unit 4 is wavy and likely erosional.

Green loam, mainly clayish loamy, occasionally sandy texture, identified at the bottom of the ditch; along its sides, the presence of abundant stones distinguishes sub-unit 4A. The overall colour is olive-brownish, with occasional visible manganese coatings. Sparse imprints of aquatic plant roots are also visible.

Figure 8

An example of a section cut through the main ditch at Salūt-ST1 (modified from Degli Esposti, Cremaschi & Costanzo, 2024: Figure 5). Unit 2: loamy sand, massive; Unit 3: laminated sand and silt; Unit 4: olive brown laminated clay. The relative position of the radiocarbon dated contexts (see Table 1) is indicated with asterisks: * SU 419; ** SU 55. For substratum keys see Figure 6.

Inside the two large channels discovered to the east of the main ditch, the overall sequence is similar to that of the main ditch but lacks evidence of anthropic contribution to sedimentation.

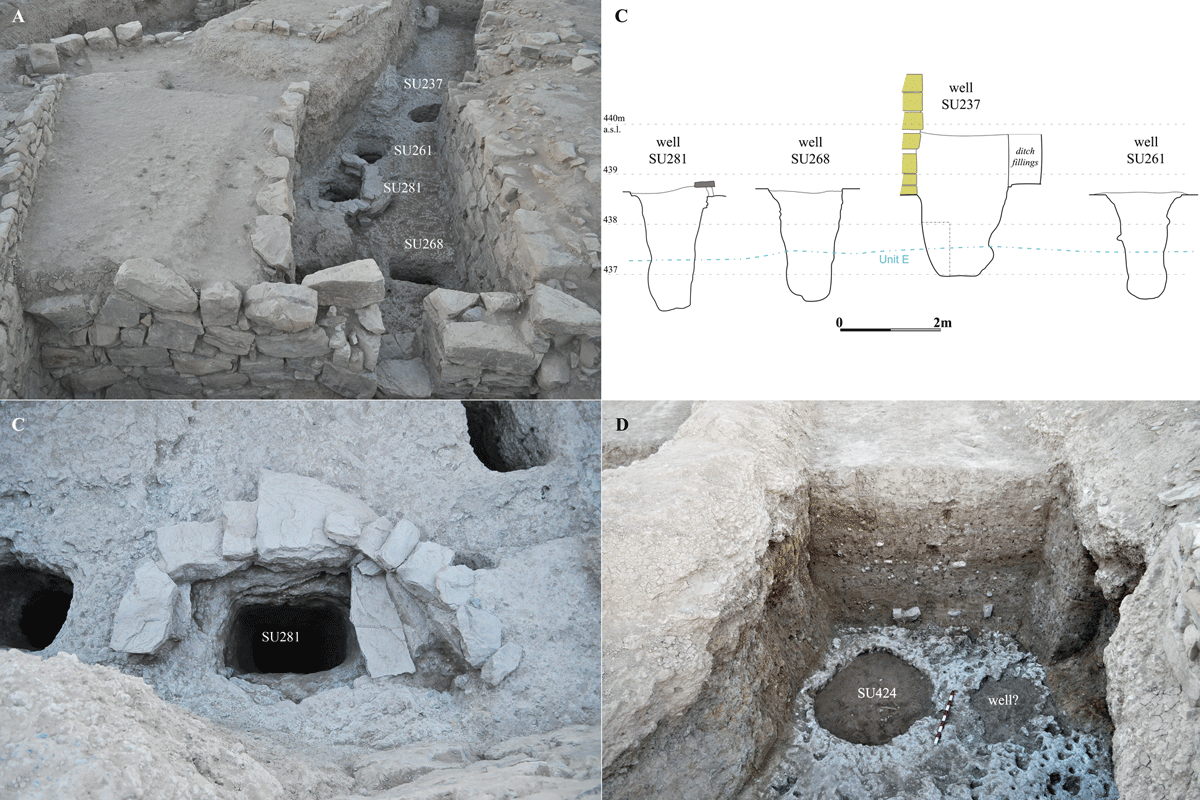

6.3.2. The EBA wells at the bottom of the ditch

Five wells were discovered, cut through the cemented base (Unit D deposits of the Calcrete 2 horizon) of the ditch (Figure 9). The presence of a sixth well is only suspected, pending further excavation. Four wells were investigated and the fifth only outlined. All the excavated wells reached roughly the same depth, significantly corresponding to a layer of poorly cemented, green-bluish silt and sand (the aquitard of Unit E). The wells were usually cut through the cemented substratum and only one had a stone curb.

Figure 9

Views and profiles of the wells discovered at the bottom of the ditch at Salūt-ST1.

The stratigraphic position of the wells shows they were excavated at slightly different times. Well SU281 appears to be the earliest, excavated after the removal of Unit 4 from the ditch bottom and equipped with a stone curb. It was consistently filled by sediments associated with the deposition of Unit 3. Well SU268, on the other hand, cut through the lower part of Unit 3 and was subsequently buried by Unit 2’s deposits. Defining the precise excavation times for the remaining two wells is more challenging, but they were certainly earlier than SU237, identified from the top of Unit 2 and filled by material eroded from the same unit.

Despite individual variations, the infills of the four earlier wells exhibit general similarities. They consist of clayish or silty loam, massive and poorly stratified, although some laminated lenses are present. The colour varies little, ranging from pale brown to very dark greyish brown. Notably, the upper portions of their infills can be correlated with the deposition of Unit 3 (except SU237).

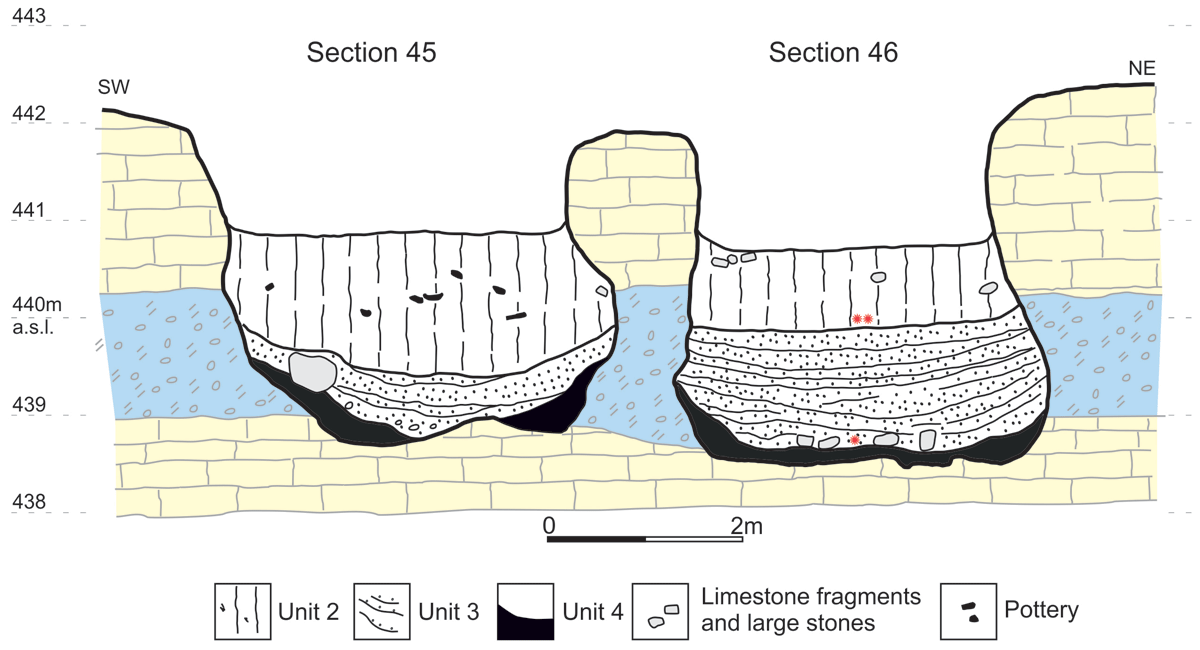

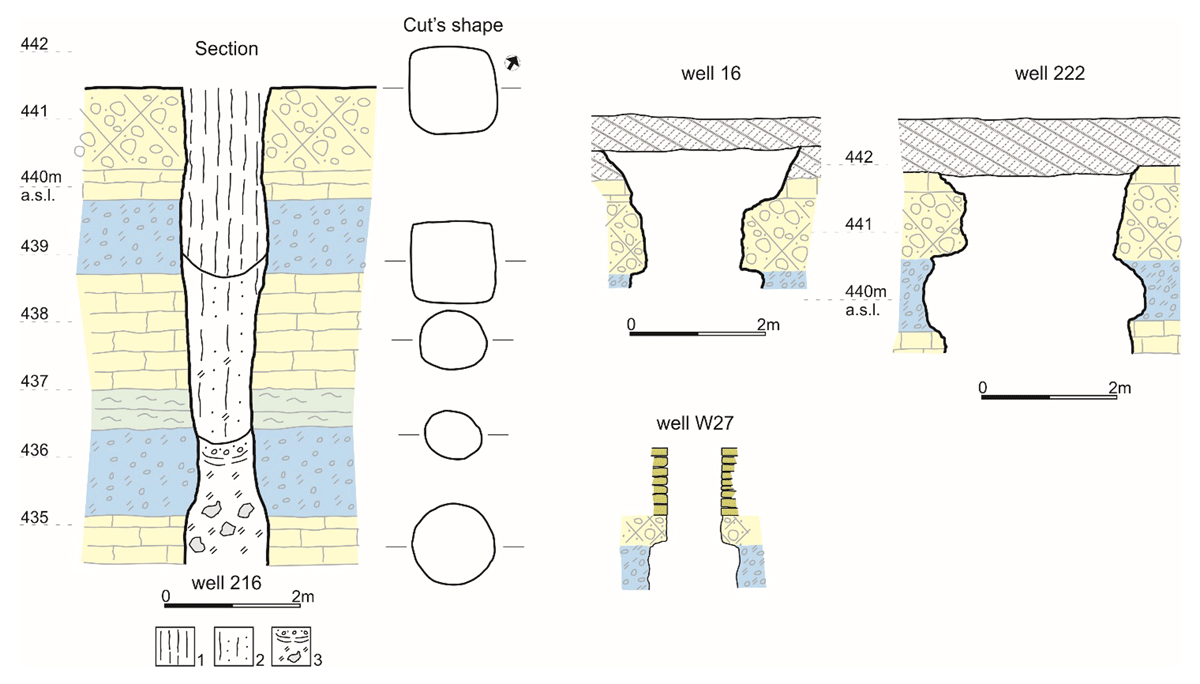

6.3.3. The IA wells

The most comprehensively investigated IA well is SU216, located southeast of the central tower of Salūt-ST1. It stands very close to one of the EBA channels running there: the features are separated by a thin (20 to 40 cm) septum in the Calcrete 1 horizon (Units A+D) through which they are cut. This proximity suggests the well was built later, when the presence of the earlier ditch was no longer relevant.

Furthermore, the shape and dimensions of SU216 differentiate it from the two wells of confirmed or highly probable EBA date: the one in the centre of the tower (SU33) and the one just north of it (SU222). The shaft of SU216 has an irregular section, varying in dimension and shape but never over 1.25 m in diameter (Figure 10). This morphology contrasts significantly with the circular section and much larger diameter (more than 2 m) of well SU33 inside the EBA tower. As mentioned above, the pottery collected during the exploration of well SU216, which reached a depth of 7 m from the calcrete surface, exclusively dates to the IA.

Figure 10

Section of the most relevant wells discussed in the text, excluding those at the bottom of the ditch Salūt-ST1. Keys: 1) upper infill, unstratified silty loam and calcrete fragments; 2) middle infill, massive sandy silt; 3) lower infill, mottled loamy silt and laminated small gravel at the top. For substratum keys see Figure 6.

This age aligns with the possibility that this well tapped into a lower aquifer (not reached by the excavation) than the EBA wells cut at the bottom of the main ditch. The excavation of well SU216 not only provided the chance to extend the stratigraphic sequence of the geological substratum but also allowed the geoarchaeological study of its infills (see Degli Esposti, Cremaschi & Costanzo 2024).

These comprise massive silty loam at the top, including abundant calcrete clasts deposited by gravity, without evidence of reworking in water. Below it until the bottom of the excavation in the well, discontinuously laminated loamy sands and sand with hydromorphic feature (mottling) occur. Coatings and infillings observed in voids indicate the substantial flow of water within the sediment at this level.

At ST1, two more wells were surely in use during the IA; the central well of the tower SU33, originally dug during the EBA, and SU222, located immediately outside the tower wall. The pottery collected from its limited excavation is only of IA date (Degli Esposti 2016) but the shape and dimensions are more consistent with the well inside the tower than with SU216, so that an original EBA date is possible.

Adjacent to SU222, well SU16 was partially investigated, but in this case it only contained Islamic pottery and the dimensions are not distinctive.

Another IA well, dubbed W27, was discovered in Area East at Salūt-IA, below the remains of a recent small mosque (Figure 5). It is distinguished by a roughly rectangular stone curb 1 m height and 0.8 × 0.6 m wide. Works were limited to the removal of some collapsed stones obliterating the upper part of the well, in order to verify the pottery sealed below them. While this appears to be of a generic IA date (not excluding a Late IA one), the excavation also allowed the identification of the upper limit of Aquifer 1, never exploited by this same well (Figure 10).

7. Discussion

7.1. The aquifers in the substratum and the phase of their exploitation

The late Quaternary geological record of Wadi Sayfham is characterised by the presence of several calcrete horizons – fluvial sediments of varying texture (from gravel to sand and silt) cemented by the CaCO3 precipitated by percolating water at a later stage. Such buried soil horizons are alternated with loose or slightly cemented levels that hosted aquifers, as revealed by their hydromorphic features, including mottling and the presence of iron-manganese oxy-hydroxides coatings.

This stratigraphic sequence of the host sediments has been confirmed at the other EBA tower of Salūt-ST2, 550 m to the northeast of ST1. More interestingly, a similar alternation of hard, impermeable calcrete horizons and loose gravel deposits with the potential to host aquifers has been identified at a greater distance, studying the ditches associated with EBA buildings at Al-Khashbah (Beuzen-Waller 2020; Beuzen-Waller et al. 2023).

The exploitation of the aquifers (1 and 2) identified in the geological substratum can be dated based on the correlation with archaeological structures and contexts.

Aquifer 1 was rather shallow (c. 2.2 m below current surface) and was completely intersected by the cut for the EBA ditch. The concavity of the ditch sides is indeed the result of erosion caused by the water leaking from this active aquifer, that at the same time led to the sedimentation of Unit 4 at the bottom of the ditch.

The ditch originally exploited as its base the Calcrete 2 horizon immediately below Aquifer 1. The search for a lower aquifer during a later phase of the EBA is witnessed by the wells excavated from the bottom of the ditch, all reaching more or less the same depth that, however, only tapped into the aquitard of Unit E. Its whole thickness was appreciated along the sides of well SU216, where the presence of the underlying Aquifer 2 was also recorded. At the corresponding depth, the sediments inside the well show in the thin section a laminated clay infilling indicative of water flow. This confirms Aquifer 2 was active after 1 had deactivated. During the IA, therefore, the active water table was at least roughly five meters deep and had fallen by more than two meters compared to Aquifer 1.

Based on radiocarbon dating results and the collected archaeological material, the excavation of the ditch and its early use can be placed within the second half of the 3rd millennium BC and corresponds to the period of Aquifer 1’s activity. The first well was excavated at the bottom of the ditch before the deposition of Unit 3. The radiocarbon date between 2464–2294 cal BC obtained for SU 419, a fireplace identified at the bottom of Unit 3, provides, therefore, a terminus ante quem for the depletion of Aquifer 1 (Table 1 and Figure 8). Its activity was apparently very short.

The end of the subsequent attempted use of Aquifer 2, or more probably the tapping of the aquitard in Unit E, can be evaluated around or before c. 2150 BC, based on the radiocarbon date between 2455–2147 cal BC obtained for a dump at the top of Unit 2 (SU 55), from where the last well was excavated (Table 1 and Figure 8).

This date, and the increasing aridity mirrored by the lowering of the water table, is consistent with the intense aridity phase documented over different areas of the world, starting at around 2200 BC (Mayewski et al. 2004). This climate shift has also been suggested among the main causes of the transition from the Early to the Middle Bronze Age in SE Arabia around 2000 BC.

7.2. The EBA ditch sediments and the changing water regime

The huge ditch of Salūt-ST1 went through different phases of use, mirrored in its infills. These originated from the degradation and collapse of its sides, human activity, and water transport. The change in the processes connected with the ditch infill is likely correlated with the lowering of the water table and the change in the water regime of the nearby wadi.

The oldest sediments, those of Unit 4, have a predominantly fine texture and comprise a scarce coarse fraction of exotic origin. These characteristics suggest low-energy, basically stagnant water. Nevertheless, this Unit is also found inside the probable inlet channel SU306, indicating a connection with the bed of Wadi Sayfham also in this phase. The greenish colour and the aquatic plant roots observed in the upper part of the Unit, however, indicate a marshy environment, implying water was leaking from Aquifer 1 and the contribution of the inlets was not substantial, possibly due to a low-energy flow or artificial regimentation. A recharge of the ditches with groundwater has been indicated as the most likely option also in the case of Al-Khashbah, where the contribution of fluvial systems has conversely been excluded and run-off reputed too unreliable (Schmitt et al. 2022).

The shift to a sandy matrix in Unit 3 and the presence of fine gravel which is not found in the bedrock, points to a changed source of the water-borne sediments. Erosion due to the upper aquifer no longer (or much less) contributes to the sediments, now mostly attributable to supply from the inlets. The sediments also differ in colour from those of Unit 4 and their poorly reduced aspect excludes prolonged saturation. What is of great relevance, Unit 3’s sediments are interspersed with anthropogenic evidence (dumps, fireplaces) that indicate the ditch was periodically dry and could host human activity. Mudcracks and vesicles seen in the thin sections support this interpretation (Degli Esposti, Cremaschi & Costanzo 2024). The continuation of this trend is witnessed by the similar sediments of Unit 2, except these are remarkably bioturbated. No cleaning of the structures led to their complete backfilling. The bioturbation indicates that when Unit 2 ceased to accumulate, the area surrounding ST1 was essentially stable and not reached by the wadi, and subject to pedological processes that require the presence of vegetation cover.

Overall, the deposition processes of Units 3 and 2 may have occurred in a drying environmental context, similar to the present one, with supply from a water course characterised by a greater flow and an increasingly seasonal rhythm. During this phase, water only remained inside the ditch for short periods and the ditch became the place of anthropic activities in essentially dry conditions.

Lastly, Unit 1 has a much coarser texture that can be correlated with higher-energy floods and a shift towards a more arid environment with higher surface discharge variability. In fact, the sediments indicate occasional floods of a high-energy watercourse capable of effectively eroding its bed and reworking even coarse sediments (Figure 11).

Figure 11

The effects of flash-floods at Salūt-ST1 and in the plain flanking Salūt-IA are evident in two main streams of gullies, plus a minor one just west of the hill hosting Salūt-IA – (Maps data: Google © 2024 CNES/Airbus, acquired Aug. 2013).

Based on the radiocarbon dates mentioned above (see Table 1), the evolution from the conditions leading to the deposition of Unit 4 to that of Unit 2 occurred between c. 2500–2150 BC, the latter being broadly the date of the hydrological change mirrored in the passage between Units 2 and 1.

The micromorphological study also showed the presence of microcharcoals inside the clayish laminae of the laminated sequences, that are reddish in colour as the above mentioned ancient external soil (Degli Esposti, Cremaschi & Costanzo 2024). The occurrence of charcoal fragments can reflect the existence of cultivated surfaces in the site’s surroundings, that were manured and above which fires were lit, consistent with the observations made in the plain’s test pits (above) and confirming that the introduction of agricultural land use in the area date back to the Bronze Age.

The later developments of this trend are witnessed by the soils in the plain. The lower layer above the calcrete of Unit A indicates a probably wetter environment (Cremaschi et al. 2018: 131), with a more developed vegetal cover. In the overlying strata, several indicators point towards increasing aridity, like the gravel deposited by torrential events that incised and removed the EBA soil, the limited development of the IA soils, and the consistent deflation of the uppermost deposits that prevented the formation of a distinct soil of Islamic date.

7.3. A broader view on water harvesting in the Iron Age: wells and aflaj

The presence of wells excavated anew during the Iron Age (SU216 at ST1, W27 at Salūt-IA), together with clear indications of reactivation (implying re-excavation and deepening) of EBA wells demonstrate the importance of these infrastructures to the IA community. A more precise date within the ample range of the IA occupation at the site (1300–300 BC) cannot be determined, but it is likely that they belong to an early phase, especially as the reused ones should have still been visible. More safely dated around the mid-2nd millennium (Degli Esposti 2021: 153, Table 1) is the substantial cistern built inside Terrace 4, that almost surely collected runoff and rain water, while possibly serving also as an additional well intercepting local aquifers.

Such an early date for these structures is of relevance when compared to the established date for the introduction of the falaj system in the plain. The study of calcareous tufa concretions inside the gallery of Falaj Shaww, one of the ancient aflaj visible in the plain to the north of the sites discussed here, proved that water was flowing inside it at least around the mid-5th century BC (Cremaschi et al. 2018). It is anyway possible that earlier use did not leave visible traces and/or other galleries were active before that date. Based on the evidence for the introduction of the aflaj system in SE Arabia, however, it seems unlikely that the system was implemented at Salūt before the commonly accepted date around the end of the 2nd millennium BC (Magee 2014: 215–222). From an environmental point of view, the adoption of the aflaj system implies the exhaustion of the shallow aquifers exploited during the BA and the necessity to collect water from those located more distant from the oasis.

North of the investigated sites, the modern layout of Falaj Farud, Falaj Shaww, and Falaj Bisya all comprise an open-air canal at their lower reaches, consistent with the necessity to irrigate fields by gravity. These can be indirect evidence of increased agricultural exploitation of the plain in a later phase of the IA (based on the evidence for an IA data for Falaj Shaww, later reworked and lowered until Islamic times, see Cremaschi et al. 2018), to an extent not sustainable during the EBA, when water should have been drawn from the wells but also from channels and ditches, too deeply incised. Besides, the consistent association with pottery and other human activity indicators (charcoal, exotic stone fragments) suggests the soils identified in the plain are anthropogenic, formed through long-term agricultural practices like the addition of fine sediment, manuring, burning, and irrigation, during two distinct phases of pedogenesis – one during the EBA, the other during the IA.

This implies a re-consideration of the role of well-drawn water to sustain agriculture before the introduction of the aflaj system (see Charbonnier 2015). The farms nowadays scattered over the plain only rely on water pumped from wells. This means that the key point is the scale of agricultural exploitation rather than its viability tout-court. It is worth noting that a recent reconstruction of ancient vegetation at Al-Khashbah, a site featuring several EBA monumental structures and associated ditches, “confidently” excluded the large-scale agricultural exploitation of the area (Schmitt et al. 2022: 9–10). At the same time, estimating the level of production necessary to support the workforce that built the impressive hydraulic structures in both the EBA and IA periods at Salūt remains a challenge.

From a more general perspective, it appears clear that local oases formed in the mid-late Holocene, as in other Old-World arid regions (e.g., Cremaschi and Zerboni, 2009, 2013) This formation was driven by geomorphological processes influenced by declining local water resources, ultimately linked to reduced rainfall. If on the one hand the formation of the oases and their attractiveness to human communities were controlled by natural processes, on the other hand their long-term survival as verdant refugia depended on human intervention.

At Salūt, it’s evident that since at least the IA, the existence of the oasis, the preservation of fertile soil for agriculture, and the concentration of water resources required significant human effort to counteract progressive aridification and support a growing population. From the IA through Islamic times and into recent years, the maintenance of small oasis patches along Wadi Sayfham relied heavily on aflaj technology, which harnessed water from distant sources and distributed it throughout the valley. Today, with many aflaj abandoned, oases persist primarily where water is pumped from deep wells (Figure 12). Oases are inherently fragile human-made ecosystems whose survival now hinges on human agency and a delicate balance between water supply and resource overuse.

Figure 12

Abandoned cultivated fields in the old oasis of Bisya (B) and at a nearby location on along the edges of the alluvial plain (A). Photos S. Bizzarri.

8. Conclusions

The study summarised here achieved a comprehensive reconstruction of the Bisya and Salūt plain’s stratigraphic record, comprising the geological substratum that pre-dates human occupation and the soils developed throughout the pre-historic and historic periods. Data about the substratum inform a reconstruction of water-table dropping from the EBA onwards. Additionally, the interpretation of the infills excavated inside wells and ditches of different ages provides indication about changes in the rain and water-flow regime over the same time span. The nature of the more recent soils identified in the plain supplies complementary information about this issue and indications about the agricultural land use since the late prehistory. The collected data allow us to draw some general conclusion about the human-environment relationship in the Salūt area:

The establishment of EBA settlement was permitted by climatic conditions wetter than today and exploited a shallow water table, currently at a depth of 2 to 3 m but surely closer to the surface by that time.

The water table dropped about 3 m likely between 2450–2300 BC. After exploiting a lower aquitard with newly excavated wells, EBA occupation ceased when it became depleted. The lowering of the water table progressed over the following millennia up to modern days (30 m), although its rate cannot be determined. If the IA well SU216 was actually tapping a lower aquifer, it would have been already more than 6.6 m from the surface.

Water table dropping went alongside a modification in the precipitation regime and wadi flow. In general, the environment became more and more arid, while the activity of the wadi shifted gradually towards a more accentuated variability connected to seasonally distributed rainfall, causing occasional floods (heavy rains).

In the early IA, dating to possibly as early as the mid-2nd millennium, new wells were excavated and old ones reactivated to sustain increasing population but the water table continued to drop as climate became increasingly arid.

During the Iron Age, at least around the mid-1st millennium BC, a radical change in land management and water harvesting took place with the construction of (at least) one falaj that tapped water in the piedmont alluvial fans flanking the alluvial plain (Cremaschi et al. 2018). The new system possibly replaced the use of wells. Aflaj were not easier to dig and maintain than the wells but provided a more regular and year-round supply of water, necessary to sustain the demographic growth witnessed by the dense settlement network.

The survival of the oasis ecosystem in the IA and later phases depended on human intervention and required careful management of natural resources (water and soil) to prevent their depletion.

Notes

Acknowledgements

This research was initially conducted (until 2019) as part of the Italian Mission To Oman of the University of Pisa, and subsequently carried on under the umbrella of the Salut and Bisya Archaeological Mission of the University of Milan (directed by AZ). The Ministry of Heritage and Tourism of the Sultanate of Oman in Muscat, the regional office in Nizwa, and the Archaeological Park of Bisya and Salut and all their staff are warmheartedly thanked for their support. The constant help of the Italian Embassy in Muscat is deeply appreciated.

Funding Information

The archaeological research is supported by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation (Direzione Generale per la Diplomazia Pubblica e Culturale), 2022–2024 grants entrusted to AZ; further financial support is from the University of Milano. Part of this research was supported by the Italian Ministry of University and Research (MUR) through the project “Dipartimenti di Eccellenza 2023–2027” awarded to the Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra “A. Desio” of the Università degli Studi di Milano (WP2). S. Costanzo is supported by the Cultural Heritage Active Innovation for Sustainable Society (CHANGES) Project, funded by the European Union – NextGenerationEU, under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP) Mission 4 Component 2 Investment Line 1.3.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.