Introduction

Many software systems have been created to manage computer-programming assignments [12]. Some are commercial applications that require students or institutions to pay fees [3456]. Others are open source software, thus providing benefits of transparency and extensibility but requiring the institution to host the software. For some types of programming assignments, students submit a solution that consists of multiple source files and perhaps configuration file(s). These solutions may reach thousands of lines of code. Various open-source tools are designed for this type of assignment, including Web-CAT [7], Submitty [8], CodEval [9], and Drop Project [10]. In other settings, programming assignments consist of short-form exercises—typically, those that can be solved in at most 100–200 lines of code within a single file or script. Such exercises are often delivered in introductory computing courses to help students gain experience with basic programming skills. In many cases, it is desirable for students to learn these skills in a setting where they can focus on programming tasks without simultaneously learning to use an integrated development environment (IDE). Existing open-source tools that support this use case include Mooshak [11], CodeRunner [12], CodeWorkout [13], CodeOcean [14], Jutge.org [15], and EDGAR [16]. Features vary across these tools, but they commonly include A) a Web-based interface, B) the ability to execute code and receive semi-immediate feedback, C) validation against expected outputs and/or unit tests, D) support for multiple programming languages, E) code execution in a secure environment, F) the ability to make multiple submissions for a given exercise, G) support for alternative problem types such as multiple-choice questions, and H) support for custom grading. We created CodeBuddy, an open-source tool that supports all of these features and many others. Although originally designed for higher-education courses, CodeBuddy’s functionality is also suitable for K-12 and informal learning.

After landing on the CodeBuddy home page, users authenticate via a third-party service (currently, Google is supported). The first user to access a newly created instance is given administrative privileges, which include the ability to create courses and assign other users as instructors. When each user creates an account, CodeBuddy randomly assigns them to either an “A” or “B” cohort. These groups can be used for online controlled experiments [17]. CodeBuddy allows instructors to perform such experiments for some existing features (described below). Because the code is open source, researchers may implement new features and evaluate their effectiveness in this way.

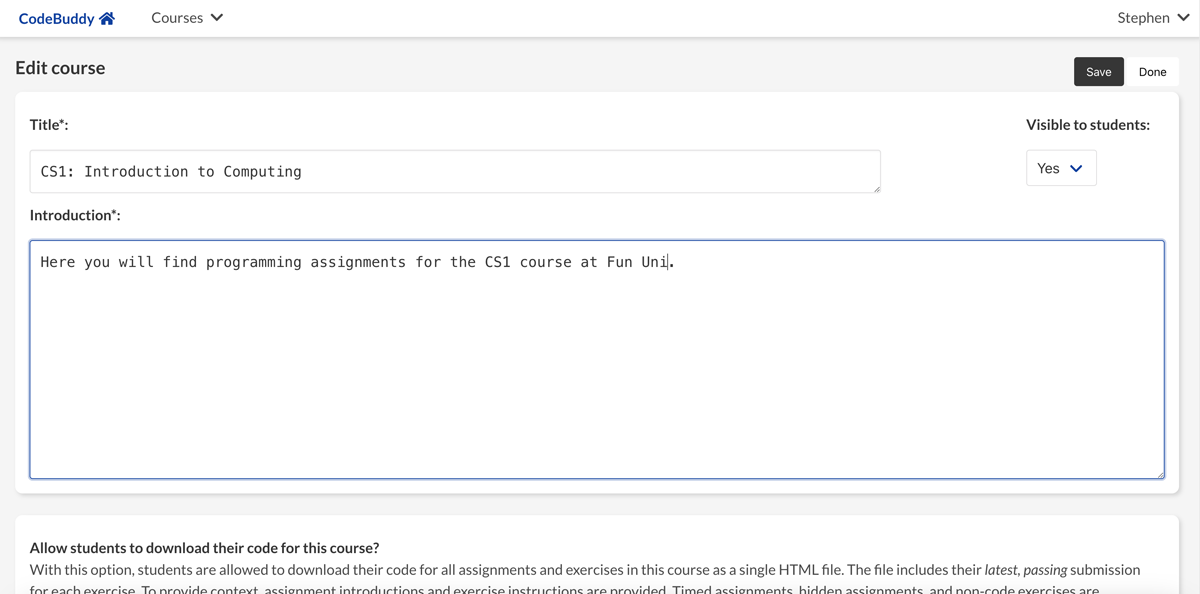

A title and introduction must be specified for each course. Optionally, a passcode may be specified as a means of restricting enrollment. An instructor can indicate whether a given course is visible to students; for example, they might hide a course temporarily while it is being developed. Instructors can create assignments (within courses) and exercises (within assignments).

When an instructor creates an assignment, they specify a title, introduction, and whether to show the “Run” button when students write code. (The “Run” button allows students to test their code before submitting it for scoring.) Optionally, an instructor may specify a start date, due date, and/or time limit. When a due date has been specified, the instructor indicates whether late submissions are allowed and whether students can view the instructor’s solution after the due date has passed. If late submissions are allowed, the instructor selects a percentage indicating how many points students can earn with late submissions. When an assignment has a time limit, the instructor indicates whether to treat the assignment as an examination. When this option is selected, students are unable to access other assignments while they are completing the examination. The instructor can specify time-limit exceptions for individual students.

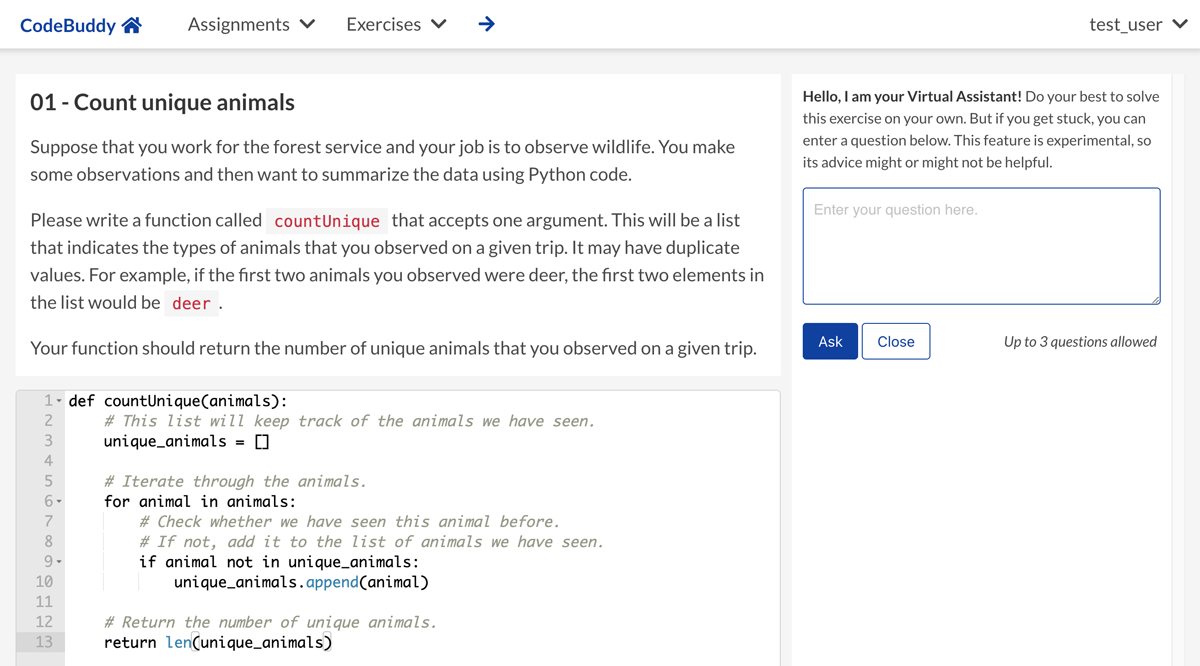

Assignments have three additional options. First, instructors can restrict access to computers with particular IP addresses; this setting would typically be used in examination settings. Second, in some cases, instructors deliver examinations in a controlled environment where students do not have access to external websites; instructors can list URLs that are exceptions. CodeBuddy retrieves content from these URLs, caches a local copy, and allows students to access them during the examination. Third, instructors can indicate whether the “Virtual Assistant” is available for a given assignment. When it is enabled, students can ask questions about their code while completing exercises (Figure 1). CodeBuddy generates a prompt for a large language model (LLM) based on the exercise requirements, the student’s code, and the student’s question. The prompt requests that the LLM provide suggestion(s) but not code. CodeBuddy sends the prompt to OpenAI’s ChatCompletion API [18] and displays the response to the student. Instructors can limit the number of interactions per student per exercise. This feature requires the instructor to specify configuration details for a (paid) OpenAI account. The Virtual Assistant can be made available to A) no students, B) all students, C) students in the “A” cohort, or D) students in the “B” cohort.

Figure 1

An example showing how the exercise page appears to students when the Virtual Assistant is enabled.

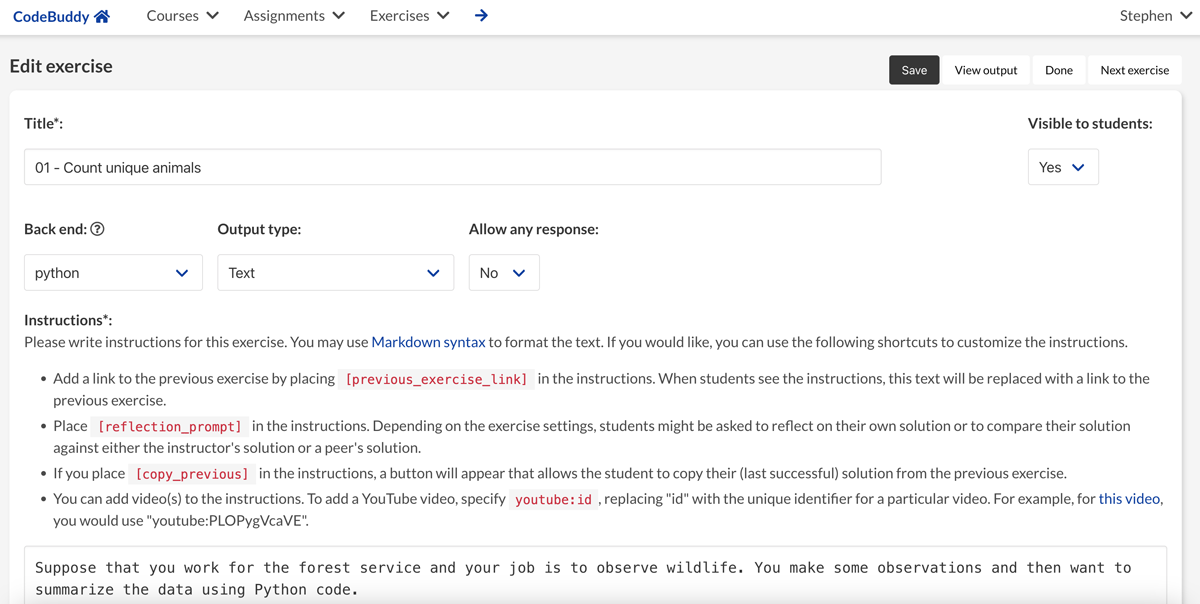

For a given exercise, an instructor specifies a title, instructions, and a solution. Exercise instructions are formatted using Markdown syntax [19], which enables flexibility in formatting without the complexity of markup languages like HTML and LaTeX [20]; however, HTML can be used if desired. When providing instructions, an instructor can include placeholders that are replaced with a) a link to the previous exercise, b) a prompt asking students to reflect on their solution; c) a button that allows the student to copy their (last successful) solution from the previous exercise, thus making it easier to deliver exercise sequences; or d) a YouTube video. A common use case is to embed a video and ask students to post code- or text-based responses.

In the exercise settings, instructors specify a “back end” to be used. Most back ends represent programming languages. The following programming languages are currently supported: bash scripting, C, C++, Java, Javascript, Julia, Python, R, and Rust. One additional back end (“not_code”) allows for submissions that are not computer code. For each back end, the instructor specifies an output type. The default is “Text.” However, for the Python and R back ends, graphics-based outputs can also be used. For Python, graphics are generated using the matplotlib or seaborn packages [2122]. For R, graphics are generated using the ggplot2 package [23]. For any back end or output type, the instructor indicates whether students’ outputs must match the instructor’s outputs (the default). When matching is required, students’ responses are graded on a pass/fail basis. When matching is not required, students receive points for any response.

The exercise settings (Figure 2) including the following, additional options:

Instructors can configure exercises to support pair programming, an evidence-based practice in which two students work together at a single computer [24]. When either student submits code for a given exercise, the code (and resulting score) are stored under both students’ accounts.

Each exercise is assigned a weight. Assignment scores are calculated based on whether students pass or fail each exercise and the weights assigned to the exercises in the assignment.

Instructors can provide data file(s) to be used as inputs for exercises. When a student’s code is executed, the data file(s) are saved to the server’s file system (within a Docker container) where they can be parsed by the student’s code. The maximum size of the data (across all files) is 10,000,000 characters.

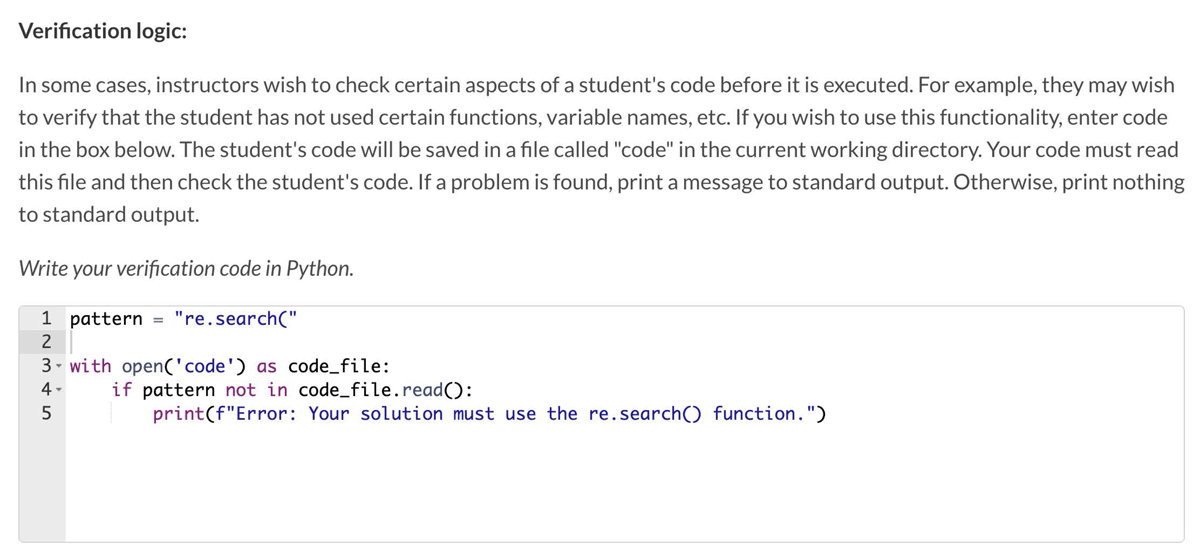

Instructors can write “verification logic” to statically analyze students’ code before it is executed. For example, if an instructor asked students to complete an exercise using regular expressions, they could parse the students’ code to verify that they had used regular expressions rather than simpler string-manipulation methods (Figure 3).

Instructors can write tests to verify the functionality of students’ code. For exercises with text outputs, CodeBuddy verifies that the output of the students’ code matches that of the instructor’s solution. For exercises with graphics outputs, CodeBuddy performs a pixel-based comparison between the student’s and instructor’s images.

For each test, the instructor can author code that will be executed before the student’s code. For example, they could declare variables that the student’s code must use. Additionally, the instructor can author code that will be executed after the student’s code. For example, if the instructions ask the student to write a function, the test code can invoke the student’s function using a variety of arguments. By providing multiple tests, the instructor can verify that the student does not “hard code” specific values.

Instructors can create tests with “hidden” inputs and/or outputs. For example, they can ask students to write a function that accepts certain arguments but not tell them what the values are. This prevents students from circumventing test requirements.

Instructors can provide starter code for students.

Instructors can provide hints. Students can view the hints after clicking a button.

Instructors can limit the number of submissions that a student can make for a given exercise.

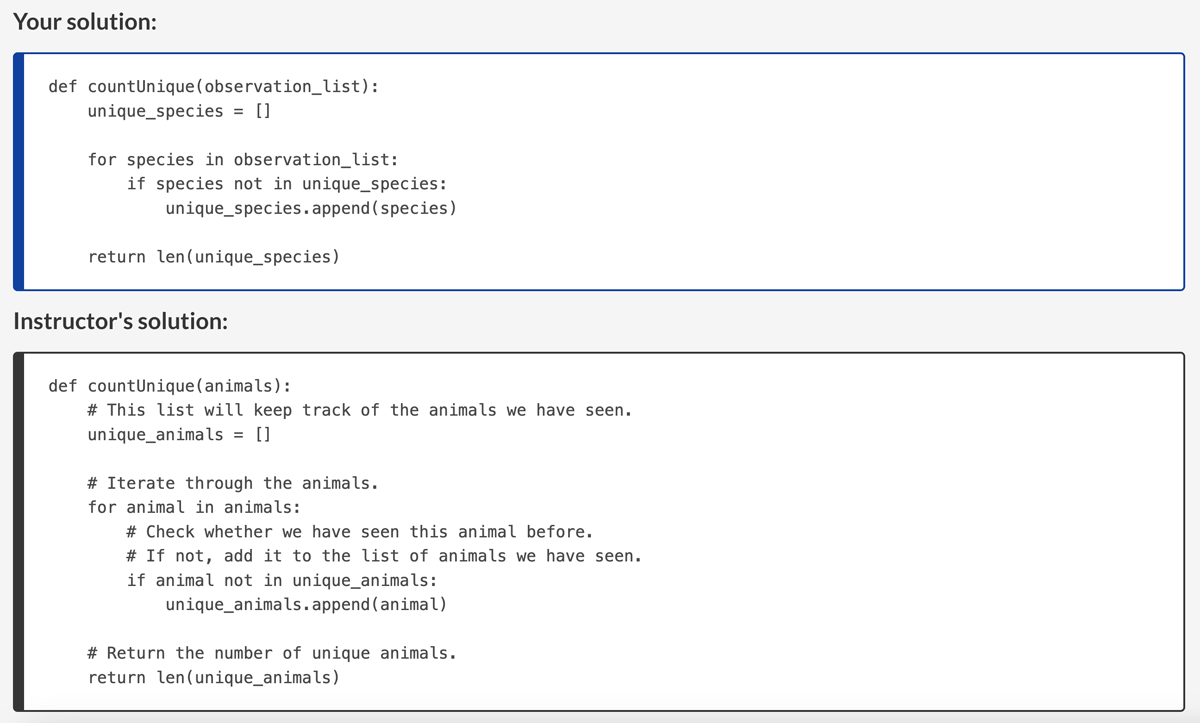

Instructors can allow students to see the instructor’s solution after they have solved a given exercise (Figure 4). This feature can be made available to A) no students, B) all students, C) students in the “A” cohort, or D) students in the “B” cohort.

Figure 2

An example of the exercise-settings page.

Figure 3

An example of using verification logic to statically analyze code. This example is from a Python programming exercise in which the student is asked to use the re.search() function to identify a particular string pattern in text. In some cases, students try to implement the logic using alternative means. The verification logic ensures that the student’s code uses re.search().

Figure 4

An example showing the ability for students to view the instructor’s solution after completing an exercise.

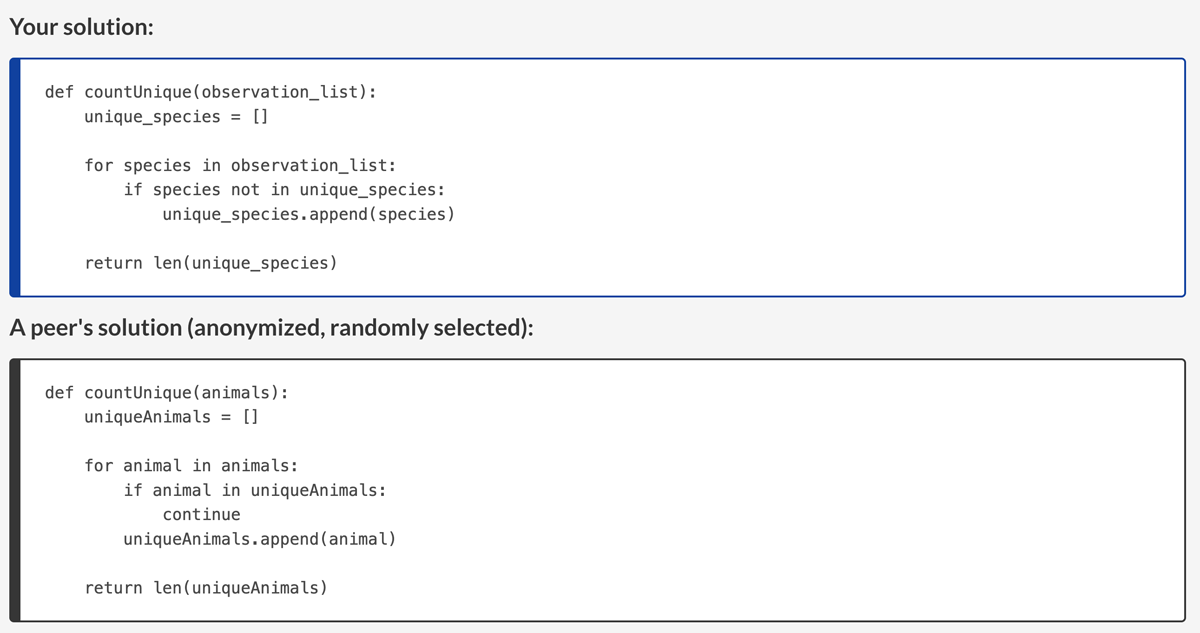

Instructors can allow students to see anonymized solutions from peers after they have solved a given exercise (Figure 5). When a student selects this option, passing solutions from other students are randomly shuffled, and one of those solutions is displayed to the student (if at least three students have solved the exercise). The student can refresh the page to repeat the shuffling process. Instructors can make this feature available to A) no students, B) all students, C) students in the “A” cohort, or D) students in the “B” cohort.

Figure 5

An example showing the ability for students to view a peer’s solution after completing an exercise.

Instructors can configure an exercise so that students are asked to write a reflection about their solution and how it compares with the instructor’s or peer’s solutions to the previous exercise.

Instructors can provide a written description of their solution.

CodeBuddy supports additional features for managing content, users, grading, preferences, and the student experience.

New administrators can be added.

Existing administrators can remove their own administrative privileges (but not others’ privileges).

Instructors can import and export assignments.

Instructors can edit, copy, move, and delete assignments and exercises (Figure 6).

Figure 6

An example of the course-settings page.

Instructors can view a table of “at-risk” students who have not made a submission in the past x number of hours (or days).

Instructors can allow students to download all of their latest, passing code submissions. Students often use this feature at the conclusion of a course.

Instructors can view course- and assignment-level summaries that show the number of completed assignments per course and the number of completed exercises per assignment, respectively; average scores are also shown.

Instructors can export scores as delimited text files.

Instructors can review students’ submissions and edit scores manually.

Instructors can assign users as teaching assistants (TAs). TAs can access the instructor’s solutions and students’ scores. They are not permitted to change some settings.

All page accesses are stored in log files, which are summarized once per day. Administrators can view and filter these summaries via the Web interface.

Instructors can configure an assignment so that other assignment(s) must be completed as prerequisite(s). Students are unable to access the assignment(s) until they have completed the prerequisite(s).

Instructors can require students to have a security code to access an assignment. The instructor can generate a PDF with a separate page for each student. The student would then receive one of these pages upon starting the assignment to ensure that the student takes the assignment in a secure location (i.e., testing center). Optionally, the instructor can configure the assignment so that a confirmation code is generated when the student completes the assignment (or ends it early). They must give this confirmation code to the instructor (or a proxy) to ensure that they completed the assignment in the secure location.

Instructors can include multiple-choice (or multiple-answer) exercises in assignments.

An assignment score is calculated as the average of the exercise scores within the assignment. Alternatively, instructors can specify custom scoring logic. For example, suppose an assignment has five exercises. An instructor might specify that if a student successfully completes one exercise (20%), the student receives a passing grade (60%). And/or they might specify that if a student completes all but one of the exercises (80%), the student receives full points (100%) for the assignment.

Administrators can configure the database to use write-ahead logging. With this option, it is possible to perform automatic backups to remote servers using third-party tools such as Litestream (https://litestream.io).

After logging in, students see an option to register for existing courses. Upon registering for one or more courses, they see a list of registered courses on the main landing page. After clicking on one of these courses, they view a list of assignments for that course, along with icons indicating whether each assignment has been completed and the number of exercises completed. Where applicable, they also see start dates, due dates, and whether the assignment is timed. Upon clicking on one of the assignments, they see a list of exercises. For each exercise, they see the number of submissions they have made, whether it has been completed, and their current score. When pair programming is enabled for a given exercise, an icon indicates this. Upon selecting a given exercise, students see the exercise title, instructions, a text box where code is entered, and a “Submit” button for submitting code. When a student has made multiple submissions, they see buttons enabling them to view previous submissions. Under default settings, a “Run” button is shown on the exercise page; this enables students to execute code and see its output before submitting it for a score. The instructor can optionally remove this button (for example, if they have placed a limit on the number of submissions). When the Virtual Assistant is enabled, students see an additional panel where they can enter questions and see its responses. Finally, a Preferences page enables all users to specify application preferences.

Evaluation

From January to April 2024, we surveyed students in two separate courses regarding their use of CodeBuddy. In these courses, students learned introductory programming skills in the Python (https://python.org) and R (https://r-project.org) languages. Assignments consisted of short-form exercises in each course. We conducted a short survey to evaluate students’ perceptions of the software. This survey was approved by Brigham Young University’s Institutional Review Board under exempt status (IRB2023-244). The survey questions included the following:

How helpful for your learning did you find CodeBuddy overall?

Which feature(s) did you find most helpful for your learning in CodeBuddy?

What suggestions, if any, do you have about improving CodeBuddy?

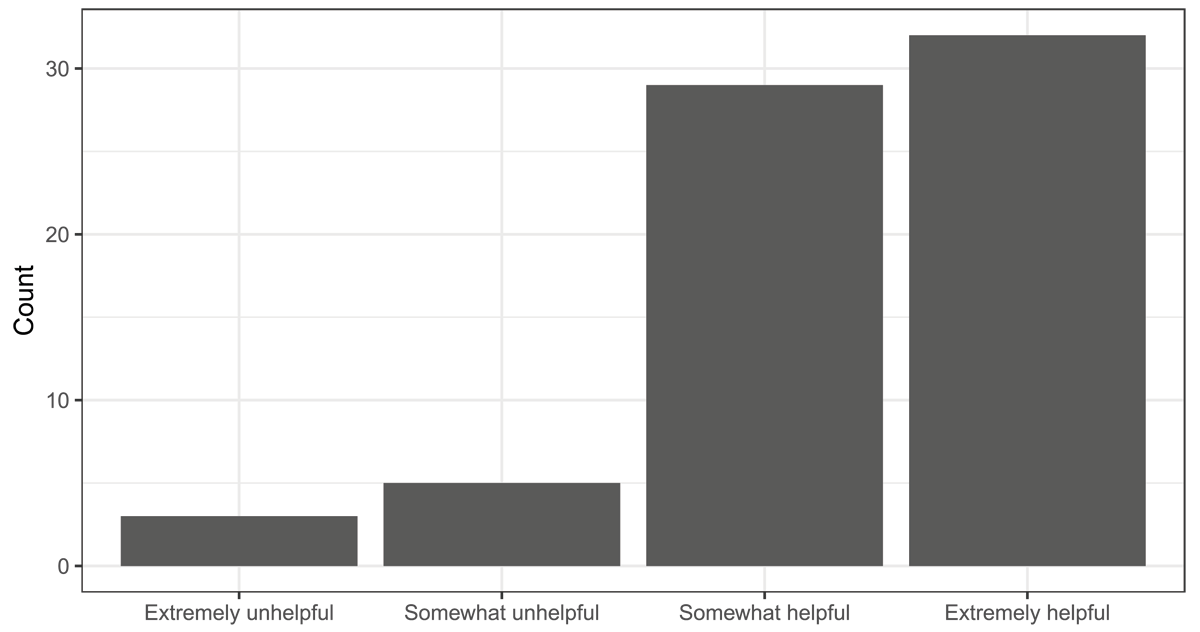

For the first question, students were asked to rate the software using a Likert scale. Allowed responses were “Extremely unhelpful,” “Somewhat unhelpful,” “Somewhat helpful,” or “Extremely helpful.” Of the respondents, 88.4% indicated that the software was “Somewhat helpful” or “Extremely helpful” (Figure 7). In response to the second question, students commented positively on A) the ability to make multiple submissions and use the “Run” button, B) support for pair programming, C) the ability to review the instructor’s solution, and D) being able to see expected outputs and compare them against their own outputs. Students commented that they would have liked it to function more like an IDE (with debugging capabilities), to have more options for customizing the software’s appearance, to provide easier navigation, and not to have tests with hidden inputs/outputs.

Figure 7

Student survey responses regarding the software’s general utility. We surveyed students to assess their perceptions of the software’s utility on a Likert scale.

Implementation and architecture

On the client side, CodeBuddy uses HTML, Cascading Style Sheets, and Javascript. These resources are served using Tornado [25] with server-side handlers written in the Python programming language. Data are stored in a relational database [26]. To facilitate deployment, security, and cross-platform compatibility, Docker containerization is used [27].

To facilitate secure code execution, CodeBuddy uses a three-layer system. First, for a given exercise, the front end (Tornado server) identifies which “back end” (associated with a particular programming language) to use. The front end submits a request to a “middle layer” Python server, which uses the FastAPI framework [28]. This request includes the student’s (or instructor’s) code, test code, verification code, data file(s), configuration settings, and back-end information. The middle layer then instantiates a Docker container; uses a volume to share the code and data files with the container; and executes a command to run the code within the container. To prevent attacks, the container is allowed minimal security privileges; furthermmore, the system administrator can configure the amount of random access memory and number of CPU processes that can be used; these settings can be different for each back end. As the container executes the code, it redirects outputs to file(s), which the middle layer parses. These outputs are returned to the front end, compared against the expected outputs, and returned to the student.

Students edit code using the Ajax.org Cloud9 Editor (Ace) [29]. Ace provides basic code completion and formatting help. When a student’s outputs are similar to the expected outputs but do not match exactly, a “diff” summary is generated. For text-based outputs, Ace displays a side-by-side comparison in a separate browser tab. For image-based outputs, the Pillow package [30] generates an image with highlighted differences; this image is displayed in a separate tab.

Additional programming languages can be supported via the following steps. For a given language, the administrator provides a Dockerfile specifying instructions for building a Linux-based, operating-system environment with software to compile (if necessary) and execute code in the respective language. A separate configuration file indicates how much memory usage to allow, whether text- and/or graphics-based outputs are supported, and code examples. Additionally, script(s) are provided for compiling (if necessary) the code, executing the code, and tidying the outputs (e.g., removing common warning or informational messages).

CodeBuddy stores data using SQLite–a serverless, embedded database engine. Accordingly, the database can be backed up and shared easily. To date, we have run the system with hundreds of students enrolled simultaneously. We are unsure of its ability to scale to more simultaneous users. Using a client-server database management system could increase its ability to scale. Another option is to run multiple instances of the server, each with a different database file.

Features supported by other tools that are not currently supported in CodeBuddy include A) CPU or memory profiling, B) uploading source files, C) command-line execution, D) integration with source-code repositories, E) automatic checks against code-style guidelines, F) plagiarism detection, G) integration with other learning management systems. The lack of some of these features is by design; other features may be implemented in future versions.

Quality control

The README file in the source-code repository provides instructions for installing and executing the software (https://github.com/srp33/CodeBuddy/blob/master/README.md). Additionally, we provide a data file that can be used to import an example assignment (https://github.com/srp33/CodeBuddy/blob/master/examples/Example_assignment.json). This assignment provides exercises that use diverse back ends, output types, and configuration options.

The source code includes an automated script that performs basic unit testing (https://github.com/srp33/CodeBuddy/blob/master/front_end/tests/run.sh). The script generates a database, starts a web-server instance, and submits HTTP requests to the server. The tests ensure that the most frequently accessed pages are rendered without error and that specific keyphrases are present in the rendered output.

Availability

Operating system

The front-end server is executed within a Docker container; therefore, it can be executed on any operating system that supports the Docker execution engine. The middle-layer server is not containerized (to avoid limitations with between-container communication). This server must be executed on a Linux operating system; additionally, the Docker execution engine must be installed on the server because the middle-layer server executes code within Docker containers.

Programming language

Server logic is written in Python (version 3.9+). Client-side code is written in Javascript and TypeScript. Shell commands build and run Docker containers.

Additional system requirements

When running idle, the Python servers use little memory and few CPU cycles. When users access the site and complete tasks other than executing code, the server uses relatively few resources. However, as course content and the number of submissions grows, the database scales accordingly. At our university, the database is currently a few gigabytes in size. The Python servers execute processes in parallel, and the administrator can configure how many processes are allowed. Additionally, the administrator can configure limits on the amount of memory that each Docker container can use when code is being executed; the default is 500 megabytes.

Dependencies

Docker execution engine.

List of contributors

All individuals who contributed to the software are listed as authors. Each author made a substantive contribution.

Software location

Archive

Name: Zenodo

Persistent identifier: DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.13250409

License: GNU Affero General Public License v3.0

Publisher: Stephen R. Piccolo

Version published: 55

Date published: 06/08/2024

Code repository

Name: GitHub

Identifier: https://github.com/srp33/CodeBuddy

License: GNU Affero General Public License v3.0

Date published: 06/08/2024

Language

English

Reuse potential

CodeBuddy has been used at Brigham Young University since 2019. Instructors from other higher-education institutions, primary or secondary schools, industry, and informal settings may find it useful for delivering short-form programming exercises.

An additional use case is the delivery of written or video-based content. In some of our courses, we use CodeBuddy to deliver video-based lectures and ask students to provide responses to each lecture segment. Students have provided informal feedback that this interactivity helps them to remain engaged with lecture material.

Because each student is assigned to an “A” or “B” cohort, CodeBuddy can be used for pedagogical research.

The website footer includes a link to a “Contact us” page, which provides details about support mechanisms. Support is provided through the Issues page on our GitHub site (for developers) and an online forum (administrators running their own instance of the software).

Funding information

The authors received internal funds from Brigham Young University to pay for a portion of this work.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to writing the software. SRP wrote the paper.