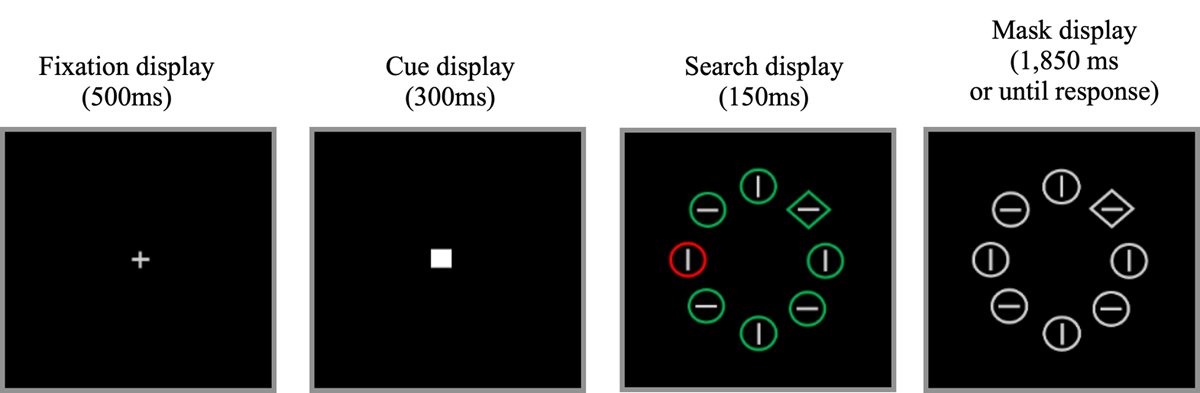

Figure 1

Sample displays during the learning phase of Experiment 1. Participants searched for the unique shape (either the unique diamond among circles or the unique circle among diamonds), while ignoring the color-singleton distractor, when present (2/3 of the trials). The search display was quickly followed by a white mask. During the test phase, the cue display was omitted. Not drawn to scale.

Table 1

Detailed description of the critical hypotheses tested in Experiment 2, their corresponding analysis plans, justifications for sensitivity, and theoretical implications.

| QUESTION | HYPOTHESIS | ANALYSIS PLAN | RATIONALE FOR DECIDING THE SENSITIVITY OF THE TEST FOR CONFIRMING OR DISCONFIRMING THE HYPOTHESIS | SAMPLING PLAN | INTERPRETATION GIVEN DIFFERENT OUTCOMES | THEORY THAT COULD BE SHOWN WRONG BY THE OUTCOMES |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do the 100%-informative spatial pre-cues reduce distractor interference? | Hypothesis 1 H1: The 100%-informative spatial pre-cues reduce distractor interference. H0: The pre-cues do not reduce distractor interference. | A 2 × 2 ANOVA with distractor interference (distractor at a low-probability location vs. absent) as a within-subject factor and group (informative- vs. neutral-cue) as a between-subjects factor (on the learning-phase data). The effect of main interest is the interaction between the two factors. | Based on Experiment 1, we expect the size of distractor interference for the neutral-cue group to be d = 1.6. Previous studies (Theeuwes, 1991; Yantis & Jonides, 1990) showed that when spatial attention is tightly focused on the upcoming target location, a salient distractor does not interfere with search. Therefore, we evaluated the required sample to observe the critical interaction assuming a distractor interference effect of d = 0 for the informative-cue group. | A power analysis indicated that we would need a sample of 16 participants (i.e., 8 in each group) to detect the critical interaction. Our preliminary data in Experiment 2 revealed distractor interference of d = 1.6 for the neutral-cue group and d = .94 for the informative-cue group. A power analysis indicated that a full sample of 30 participants in each group would suffice to detect a reliable interaction. | Finding that distractor interference is significantly larger for the neutral- than for the informative-cue group, would support H1. Finding that this interaction is not significant would support H0. | Support for H1 would invalidate the claim that focused attention does not weaken attentional capture by salient irrelevant objects. Support for H0 would invalidate the claim that focused attention reduces – let alone prevents – attentional capture by salient irrelevant objects (Theeuwes, 1991; Yantis & Jonides, 1990) |

| Does statistical learning persist when the probability imbalance is discontinued? | Hypothesis 2 H1: Statistical learning persists into the test phase. H0: Statistical learning does not persist into the test phase. | A planned comparison (i.e., a paired t-test) between the high- and low-probability location conditions for the neutral-cue group (on the test-phase data). | We selected the size of the statistical learning effect to be d = .67 based on Experiment 1. | A power analysis indicated that we would need a sample of 16 participants to detect a statistical learning effect of this size. | Replication (see Experiment 1). | Not applicable (replication). |

| Is statistical learning modulated by spatial attention? | Hypothesis 3 H1: Statistical learning is modulated by spatial attention. H0: Statistical learning is independent of spatial attention. | A mixed 2 × 2 ANOVA with statistical learning (high- vs. low-probability location) as a within-subject factor and group (informative- vs. neutral-cue group) as a between-subjects factor (on the test-phase data). The effect of main interest is the interaction between the two factors. | We expect statistical learning of size d = .67 for the neutral-cue group based on Experiment 1. No study has measured statistical learning while using 100%-informative spatial cues. We evaluated the required sample to observe the critical interaction assuming a statistical learning effect of d = 0 for the informative-cue group. | Frequentist ANOVA: A power analysis indicated that we would need a sample size of 88 participants (i.e., 44 in each group) to detect the critical interaction. Bayesian ANOVA: A power analysis indicated that we would need 100 participants (i.e., 50 in each group) to observe BF10 > 3 supporting the presence of the critical interaction. | Finding that statistical learning interacts with group during test (p < .05 and BF10 > 3 for the interaction) would support H1. Finding that statistical learning does not interact with group during test (p > .05 and BF01 > 3 for the interaction) would support H0. | Support for H1 would invalidate the claim that statistical learning is independent of spatial attention (Duncan & Theeuwes, 2020). Support for H0 would invalidate the claim that statistical learning is modulated by or contingent on spatial attention (Baker et al., 2004). |

| If statistical learning is modulated by spatial attention, is spatial attention necessary for statistical learning? | Hypothesis 4 H1: Spatial attention is necessary for statistical learning to occur. H0: Spatial attention is not necessary for statistical learning to occur. | Exploratory analysis A A planned comparison on distractor interference (distractor at a low-probability location vs. absent) in the learning phase and a planned comparison on statistical learning (high- vs. low-probability location) in the test phase, for the informative-cue group. | Exploratory analysis A Given that a significant distractor-interference of size d = .95 corresponded to a 20-ms effect (SD = 21.8 ms), in Experiment 1), we will consider that distractor-interference is negligible if it is non-significant or smaller than d = .5 (roughly corresponding to a 10-ms effect). We will consider that statistical learning did not occur during the test phase, if it is non-significant or smaller than d = .2. | Exploratory analysis A A power analysis indicated that we would need a sample of 27 participants to detect distractor interference of d = .5. A power analysis indicated that we would need a sample of 156 participants to detect a statistical learning effect of d = .2 | Exploratory analysis A Finding no statistical learning in the test phase would support H1 (irrespective of the size of distractor interference in the learning phase). Finding statistical learning in the test phase and a negligible distractor interference in the learning phase would support H0. | Support for H1 would invalidate the claim that spatial attention is unnecessary for statistical learning (Duncan & Theeuwes, 2020). Support for H0 would invalidate the claim that spatial attention is necessary for statistical learning (Baker et al., 2004). |

| Exploratory analysis B A linear regression analysis between statistical learning in the test phase and distractor interference in the learning phase, for the informative-cue group. The main effect of interest is the regression coefficient (β) and the intercept (α). | Exploratory analysis B We will conduct this analysis only if SL is modulated by spatial attention, and therefore expect a significant correlation between distractor interference in the learning phase and statistical learning in the test phase. We will consider that this prediction is confirmed if the regression coefficient is significant and larger than β = .4 (which is equivalent to a Pearson’s correlation coefficient of size, r = .4). | Exploratory analysis B A power analysis indicated that we would need a sample of 46 participants to detect a β = .4 for the correlation between distractor interference and statistical learning. | Exploratory analysis B Finding that the intercept is not significantly different from zero would support H1. Finding that the intercept is significantly larger than zero would support H0. |

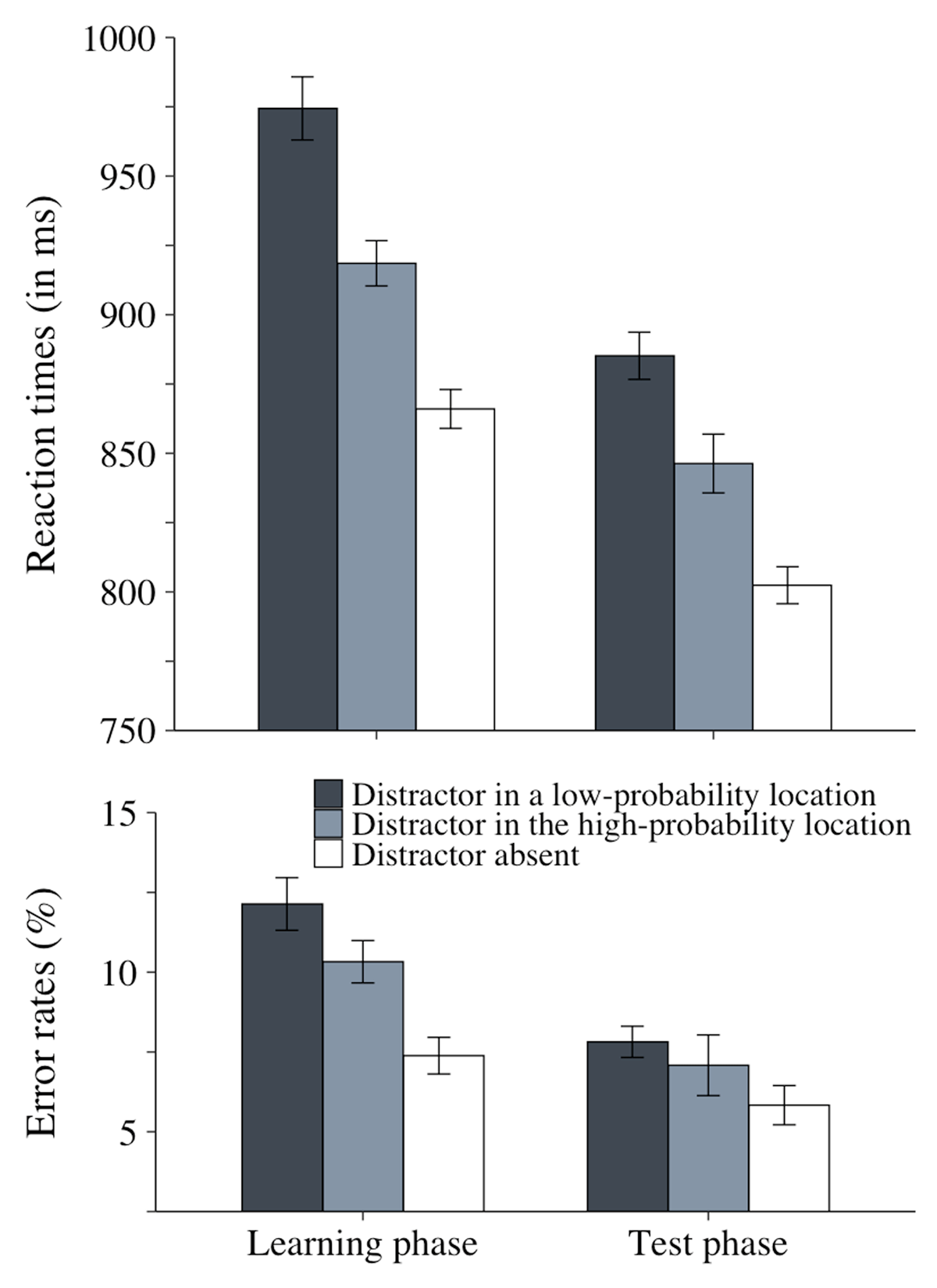

Figure 2

Mean RTs (in millseconds) and mean % of errors as a function of distractor condition (present at a low-probability location, present at the high-probability location, or absent) in the learning and test phases in Experiment 1. The error bars represent within-subject standard error of the mean.

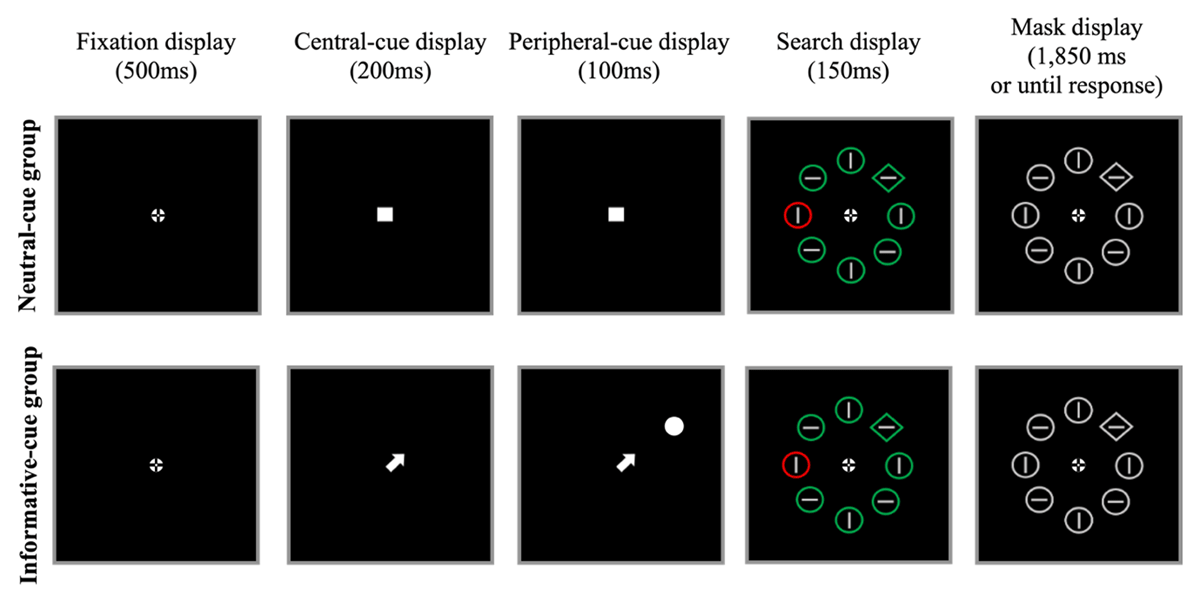

Figure 3

Sample displays during the learning phase of Experiment 2. As in Experiment 1, participants searched for the unique shape (here, the diamond), while ignoring the color-singleton distractor, when present (2/3 of the trials). For the informative-cue group (upper panel), the central arrow cue as well as the peripheral cue indicated the upcoming target’s location with 100% validity. During the test phase, the cue displays were omitted (the test phase was therefore be the same for the neutral- and informative-cue groups). Not drawn to scale.

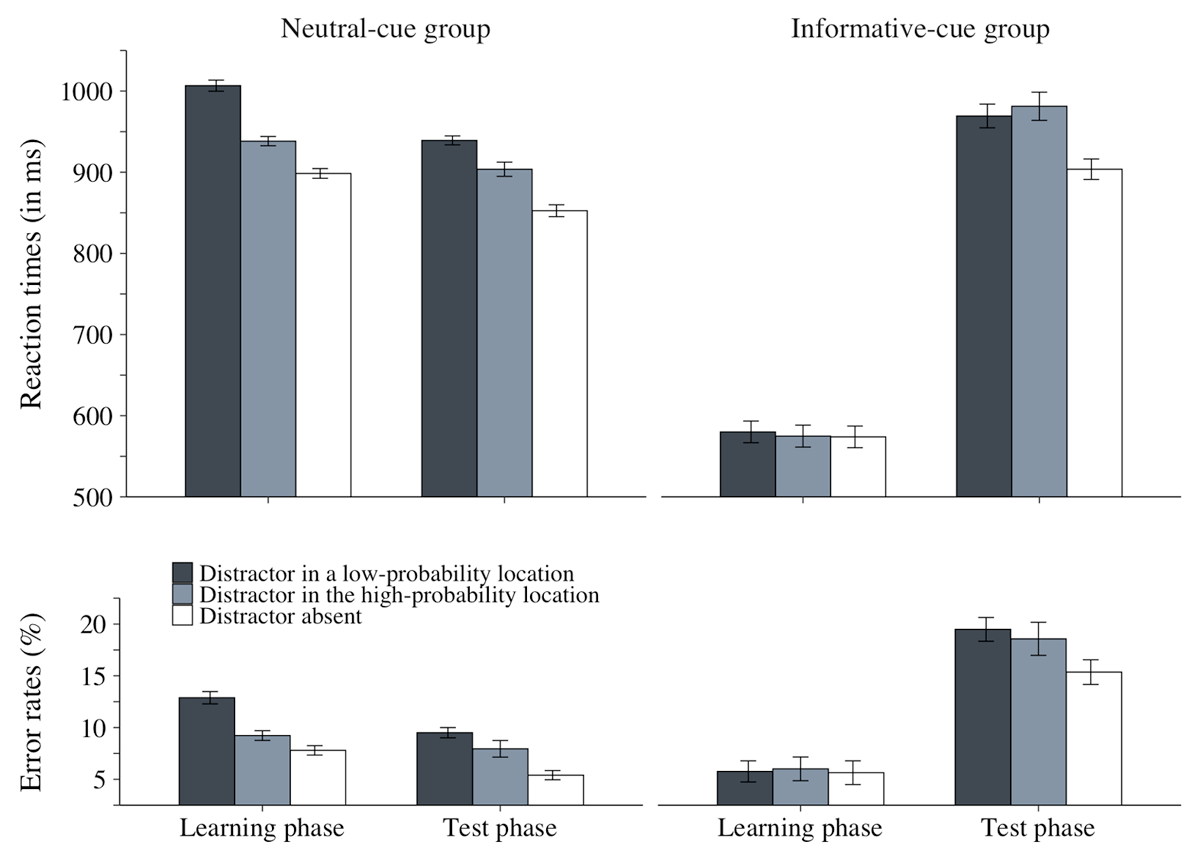

Figure 4

Mean RTs (in millseconds) and mean % of errors as a function of distractor condition (present at a low-probability location, present at the high-probability location, or absent) in the learning phase (left panel) and in the test phase (right panel), separately for the informative-cue and for the neutral-cue groups in Experiment 2. The error bars represent within-subject standard error of the mean.