Table 1

Studies included in the present meta-analysis.

| NUMBER OF STUDY | REFERENCE | PARADIGM | NUMBER OF RANDOM EFFECTS | LANGUAGES ASSESSED1 | RATIO PROFICIENCY LESS DOMINANT/DOMINANT (%)2 | TIMING |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Blanco-Elorrieta, E., & Pylkkänen, L. (2017). Bilingual language switching in the laboratory versus in the wild: The spatiotemporal dynamics of adaptive language control. Journal of Neuroscience, 37, 9022–9036. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0553-17. | cued | 3 | Arabic/English | 84.5 | CTI 300 ms |

| 2 | Bonfieni, M., Branigan, H. P., Pickering, M. J., & Sorace, A. (2019). Language experience modulates bilingual language control: The effect of proficiency, age of acquisition, and exposure on language switching. Acta Psychologica, 193, 160–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2018.11.004 | cued | 2 | Italian/English Italian/Sardinian | 83.94 95.42 | CTI 0 ms |

| 3 | Calabria, M., Branzi, F. M., Marne, P., Hernández, M., & Costa, A. (2015). Age-related effects over bilingual language control and executive control. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 18, 65–78. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728913000138 | cued | 2 | Catalan/Spanish | 97.50 52.50 | CTI 1000 ms |

| 4 | Calabria, M., Hernández, M., Branzi, F. M., & Costa, A. (2012). Qualitative differences between bilingual language control and executive control: Evidence from task-switching. Frontiers in Psychology, 2, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00399 | cued | 3 | Catalan/Spanish | 97.50 100.00 92.50 | CTI 1000 ms |

| 5 | Campbell, J. I. D. (2005). Asymmetrical language switching costs in Chinese–English bilinguals’ number naming and simple arithmetic. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 8, 85–91. https://doi.org/10.1017/S136672890400207X | cued | 6 | Chinese/English | 60.00 61.67 61.67 61.67 61.67 61.67 | CTI 1000 ms |

| 6 | Christoffels, I. K., Fink, C., & Schiller, N. O. (2007). Bilingual language control: An event-related brain potential study. Brain Research, 1147, 192–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2007.01.137 | cued | 2 | German/Dutch | 63.64 | not given |

| 7 | Contreras-Saavedra, C. E., Koch, I., Schuch, S., & Philipp, A. M. (2021). The reliability of language-switch costs in bilingual one- and two-digit number naming. International Journal of Bilingualism, 25, 272–285. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367006920951873 | cued | 3 | German/Spanish/English | 77.65+ | CTI 100ms |

| 8 | Costa, A., & Santesteban, M. (2004). Lexical access in bilingual speech production: Evidence from language switching in highly proficient bilinguals and L2 learners. Journal of Memory and Language, 50, 491–511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2004.02.002 | cued | 7 | Korean/Spanish Spanish/Catalan Spanish/English | 63.64 68.99 57.50 92.41 94.18 70.13 94.46 | CTI 2000 ms SOA§ 500/800 ms |

| 9 | Costa, A., Santesteban, M. l, & Ivanova, I. (2006). How do highly proficient bilinguals control their lexicalization process? Inhibitory and language-specific selection mechanisms are both functional. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 32, 1057–1074. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.32.5.1057 | cued | 6 | Spanish/Basque Spanish/English Catalan/English Spanish/new language | 94.74 92.50 58.33 53.33 92.50 47.50 | CTI 2000 ms |

| 10 | de Bruin, A., Samuel, A. G., & Duñabeitia, J. A. (2018). Voluntary language switching: When and why do bilinguals switch between their languages? Journal of Memory and Language, 103, 28–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2018.07.005 | cued & voluntary | 3 | Basque/Spanish | 89.25 92.63 92.63 | CTI 500 ms |

| 11 | Declerck, M., & Philipp, A. M. (2015). The unusual suspect: Influence of phonological overlap on language control. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 18, 726–736. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728914000236 | cued | 2 | German/English | 70.00 84.29 | CTI 500 ms |

| 12 | Declerck, M., Stephan, D. N., Koch, I., & Philipp, A. M. (2015). The other modality: Auditory stimuli in language switching. Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 27, 685–691. https://doi.org/10.1080/20445911.2015.1026265 | alternating runs | 2 | German/English | 72.86 72.86 | not applicable |

| 13 | Declerck, M., Koch, I., & Philipp, A. M. (2012). Digits vs. pictures: The influence of stimulus type on language switching. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 15, 896–904. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728912000193 | cued | 4 | German/English | 70.00 70.00 70.00 70.00 | CTI 1000 ms |

| 14 | Declerck, M., Philipp, A. M., & Koch, I. (2013). Bilingual control: Sequential memory in language switching. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 39, 1793–1806. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033094 | alternating runs | 8 | German/English | 67.14 67.14 75.71 75.71 71.43 71.43 67.14 67.14 74.29 | not applicable |

| 15 | Declerck, M., Koch, I., & Philipp, A. M. (2015). The minimum requirements of language control: Evidence from sequential predictability effects in language switching. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 41, 377–394. https://doi.org/10.1037/xlm0000021 | alternating runs/cued | 10 | German/English | 74.29 64.29 64.29 64.29 68.57 74.29 74.29 68.57 72.86 72.86 | CTI 0 ms |

| 16 | Declerck, M., Thoma, A. M., Koch, I., & Philipp, A. M. (2015). Highly proficient bilinguals implement inhibition: Evidence from n-2 language repetition costs. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 41, 1911–1916. https://doi.org/10.1037/xlm0000138 | cued, switching between two languages included | 0 | German/English | No self-rated proficiency scores | CTI 100 ms |

| 17 | Declerck, M., Ivanova, I., Grainger, J., & Duñabeitia, J. A. (2020). Are similar control processes implemented during single and dual language production? Evidence from switching between speech registers and languages. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 23, 694–701. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728919000695 | cued | 3 | French/English | 83.52+ 76.57 | Exp 2: CTI 0/800ms |

| 18 | Gollan, T. H., & Ferreira, V. S. (2009). Should I stay or should I switch? A cost–benefit analysis of voluntary language switching in young and aging bilinguals. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 35, 640–665. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014981 | voluntary | 3 | English/Spanish | 83.82 83.58 81.36 | not applicable |

| 19 | Gollan, T. H., Kleinman, D., & Wierenga, C. E. (2014). What’s easier: Doing what you want, or being told what to do? Cued versus voluntary language and task switching. Journal of Experimental Psychology. General, 143, 2167–2195. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038006 | cued & voluntary | 4 | Spanish/English | 92.31 98.39 92.31 98.39 | CTI 250 ms |

| 20 | Graham, B., & Lavric, A. (2021). Preparing to switch languages versus preparing to switch tasks: Which is more effective? Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, No Pagination Specified. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0001027 | cued | 3 | German/French/Spanish/English | 90.83 | CTI 50/ 800/ 1175 ms |

| 21 | Gross, M., & Kaushanskaya, M. (2015). Voluntary language switching in English–Spanish bilingual children. Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 27, 992–1013. https://doi.org/10.1080/20445911.2015.1074242 | voluntary | 0 | Spanish/English | No self-rated proficiency scores | not applicable |

| 22 | Gullifer, J. W., Kroll, J. F., & Dussias, P. E. (2013). When language switching has no apparent cost: Lexical access in sentence context. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 278.$ | alternating runs | 2 | Spanish/English | 94.43 94.43 | not applicable |

| 23 | Grunden, N., Piazza, G., García-Sánchez, C., & Calabria, M. (2020). Voluntary Language Switching in the Context of Bilingual Aphasia. Behavioral Sciences, 10, 141. | voluntary | 4 | Spanish/Catalan | 100 | not applicable |

| 24 | Jevtović, M., Duñabeitia, J. A., & Bruin, A. de. (2019). How do bilinguals switch between languages in different interactional contexts? A comparison between voluntary and mandatory language switching. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 23, 401–413. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728919000191 | voluntary | 2 | Spanish/Basque | 93.60 93.60 | not applicable |

| 25 | Jylkkä, J., Lehtonen, M., Lindholm, F., Kuusakoski, A., & Laine, M. (2018). The relationship between general executive functions and bilingual switching and monitoring in language production. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 21, 505–522. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728917000104 | cued | 0 | Finnish/English | 84.29 | CTI 0 ms |

| 26 | Kang, C., Ma, F., & Guo, T. (2018). The plasticity of lexical selection mechanism in word production: ERP evidence from short-term language switching training in unbalanced Chinese–English bilinguals. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 21, 296–313. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728917000037 | cued | 2 | Chinese/English | 63.29 69.60 | CTI 800 ms |

| 27 | Khateb, A., Shamshoum, R., & Prior, A. (2017). Modulation of language switching by cue timing: Implications for models of bilingual language control. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 43, 1239–1253. https://doi.org/10.1037/xlm0000382 | cued | 5 | Arabic/Hebrew | 90.00 90.00 90.00 90.00 90.00 | CTI 0/300/900 ms TCI 300/900 ms |

| 28 | Kirk, N. W., Kempe, V., Scott-Brown, K. C., Philipp, A., & Declerck, M. (2018). Can monolinguals be like bilinguals? Evidence from dialect switching. Cognition, 170, 164–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2017.10.001 | cued | 8 | German/German

Dialect English/English Dialect | 90.00 90.00 95.57 90.14 95.57 95.57 62.29 62.29 | CTI 0 ms |

| 29 | Kleinman, D., & Gollan, T. H. (2016). Speaking two languages for the price of one: Bypassing language control mechanisms via accessibility-driven switches. Psychological Science, 27, 700–714. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797616634633# | cued | 1 | Spanish/English | 90.91 | CTI 250 ms |

| 30 | Kleinman, D., & Gollan, T. H. (2018). Inhibition accumulates over time at multiple processing levels in bilingual language control. Cognition, 173, 115–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2018.01.009 | cued, 50% switch condition only taken into account | 1 | Spanish/English | 74.74 | CTI 250 ms |

| 31 | Kubota, M., Chevalier, N., & Sorace, A. (2019). How bilingual experience and executive control influence development in language control among bilingual children. Developmental Science, e12865. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.12865 | cued | 2 | Japanese/English | No self-rated proficiency scores | CTI 0 ms |

| 32 | Lavric, A., Clapp, A., East, A., Elchlepp, H., & Monsell, S. (2019). Is preparing for a language switch like preparing for a task switch? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 45, 1224–1233. https://doi.org/10.1037/xlm0000636 | cued | 4 | German/English | 90.00 90.00 90.00 90.00 | CTI 100/1500 ms |

| 33 | Li, S., Botezatu, M. R., Zhang, M., & Guo, T. (2021). Different inhibitory control components predict different levels of language control in bilinguals. Memory & Cognition. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-020-01131-4 | cued | 2 | Chinese/English | 63.25 67.18 | CTI 0 ms |

| 34 | Li, C., & Gollan, T. H. (2018). Cognates Facilitate Switches and then Confusion: Contrasting Effects of Cascade versus Feedback on Language Selection. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 44, 974–991. https://doi.org/10.1037/xlm0000497 | cued | 6 | English/Spanish | 76.55 72.64 68.89 | CTI 0 ms |

| 35 | Li, C., & Gollan, T. H. (2021). What cognates reveal about default language selection in bilingual sentence production. Journal of Memory and Language, 118, 104214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2020.104214 | cued | 6 | Spanish/English | 80.72† 78.25 76.25 | CTI 0 ms |

| 36 | Liu, H., Zhang, M., Pérez, A., Xie, N., Li, B., & Liu, Q. (2019). Role of language control during interbrain phase synchronization of cross-language communication. Neuropsychologia, 131, 316–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2019.05.014 | cued | 4 | Chinese/English | 62.30 | CTI 250 ms |

| 37 | Liu, C., Jiao, L., Wang, Z., Wang, M., Wang, R., & Wu, Y. J. (2019). Symmetries of bilingual language switch costs in conflicting versus non-conflicting contexts. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 22, 624–636. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728918000494 | cued | 2 | Chinese/English | 55.72 59.73 | CTI 0 ms |

| 38 | Liu, C., Timmer, K., Jiao, L., Yuan, Y., & Wang, R. (2019). The influence of contextual faces on bilingual language control. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 72, 2313–2327. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747021819836713 | cued | 6 | Chinese/English | 55.59 55.59 55.59 57.65 57.65 57.65 | CTI 1000 ms |

| 39 | Liu, H., Kong, C., de Bruin, A., Wu, J., & He, Y. (2020). Interactive influence of self and other language behaviors: Evidence from switching between bilingual production and comprehension. Human Brain Mapping, 41, 3720–3736. | cued | 2 | Chinese/English | 65.39 | CTI 0 ms |

| 40 | Liu, H., Tong, J., de Bruin, A., Li, W., He, Y., & Li, B. (2020). Is inhibition involved in voluntary language switching? Evidence from transcranial direct current stimulation over the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 147, 184–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2019.12.002 | voluntary | 3 | Chinese/English | 76.77 | not applicable |

| 41 | Ma, F., Li, S., & Guo, T. (2016). Reactive and proactive control in bilingual word production: An investigation of influential factors. Journal of Memory and Language, 86, 35–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2015.08.004 | cued | 9 | Chinese/English | 73.63 73.63 73.63 68.66 68.66 68.66 73.56 73.56 73.56 | CTI 0/500/800 ms TCI 200/500/800 ms RCI 500/800/1500 ms |

| 42 | Macizo, P., Bajo, T., & Paolieri, D. (2012). Language switching and language competition. Second Language Research, 28, 131–149. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267658311434893 | reading aloud | 1 | Spanish/English | 85.08 | not applicable |

| 43 | Martin, C. D., Strijkers, K., Santesteban, M., Escera, C., Hartsuiker, R. J., & Costa, A. (2013). The impact of early bilingualism on controlling a language learned late: An ERP study. Frontiers in Psychology, 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00815 | cued | 3 | Spanish/Catalan/Spanish/English | 55.00 55.00 97.50 | CTI 2000 ms |

| 44 | Massa, E., Köpke, B., & El Yagoubi, R. (2020). Age-related effect on language control and executive control in bilingual and monolingual speakers: Behavioral and electrophysiological evidence. Neuropsychologia, 138, 107336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2020.107336 | ? | 2 | French/Italian | 62.07 61.67 | not applicable |

| 45 | Mofrad, F. T., Jahn, A., & Schiller, N. O. (2020). Dual Function of Primary Somatosensory Cortex in Cognitive Control of Language: Evidence from Resting State fMRI. Neuroscience, 446, 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2020.08.032 | cued | 0 | Dutch/English | No self-rated proficiency scores | CTI 750 ms |

| 46 | Mosca, M., & Clahsen, H. (2016). Examining language switching in bilinguals: The role of preparation time. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 19, 415–424. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728915000693 | cued | 2 | German/English | 75.4 | CTI 0/800 ms |

| 47 | Mosca, M., & de Bot, K. (2017). Bilingual language switching: Production vs. recognition. Frontiers in Psychology, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00934 | cued | 0 | Dutch/English | No self-rated proficiency scores | CTI 0 ms |

| 48 | Olson, D. J. (2016). The gradient effect of context on language switching and lexical access in bilingual production. Applied Psycholinguistics, 37, 725–756. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716415000223 | cued | 2 | Spanish/English | 74.44 | CTI 0 ms |

| 49 | Peeters, D. (2020). Bilingual switching between languages and listeners: Insights from immersive virtual reality. Cognition, 195, 104107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2019.104107 | cued (contrast full switch/no switch) | 0 | Dutch/English | 82.14 | CTI 0 ms |

| 50 | Peeters, D., & Dijkstra, T. (2018). Sustained inhibition of the native language in bilingual language production: A virtual reality approach. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 21, 1035–1061. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728917000396 | cued | 4 | Dutch/English | 76.86 74.56 80.23 75.73 | CTI 0 ms |

| 51 | Philipp, A. M., Gade, M., & Koch, I. (2007). Inhibitory processes in language switching: Evidence from switching language-defined response sets. European Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 19, 395–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/09541440600758812 | cued | 6 | German/English/French | No self-rated proficiency scores | CTI 100/1000 ms |

| 52 | Prior, A., & Gollan, T. H. (2011). Good language-switchers are good task-switchers: Evidence from Spanish – English and Mandarin –English bilinguals. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 17, 682–691. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355617711000580 | cued | 2 | Spanish/English Chinese/English | 85.07 64.71 | CTI 250 ms |

| 53 | Prior, A., & Gollan, T. H. (2013). The elusive link between language control and executive control: A case of limited transfer. Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 25, 622–645. https://doi.org/10.1080/20445911.2013.821993 | cued | 4 | Spanish/English Chinese/English Hebrew/English English/various | 42.03 82.86 67.16 90.77 | CTI 250 ms |

| 54 | Reynolds, M. G., Schlöffel, S., & Peressotti, F. (2016). Asymmetric switch costs in numeral naming and number word reading: Implications for models of bilingual language production. Frontiers in Psychology, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.02011 | reading aloud/cued/alternating runs | 10 | Italian/English English/French | 50.14 50.14 No self-rated proficiency scores | not applicable |

| 55 | Santesteban, M., & Costa, A. (2016). Are cognate words “special”? In J. W. Schwieter (Hrsg.), Cognitive control and consequences of multilingualism (Bd. 2, S. 97–125). John Benjamins Publishing Company. | cued | 4 | Spanish/Catalan | 95.72 54.14 | CTI 2000 ms |

| 56 | Segal, D., Stasenko, A., & Gollan, T. H. (2019). More evidence that a switch is not (always) a switch: Binning bilinguals reveals dissociations between task and language switching. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 148, 501–519. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000515 | cued | 1 | English/Spanish | 90.91 | CTI 250 ms |

| 57 | Slevc, L. R., Davey, N. S., & Linck, J. A. (2016). A new look at “the hard problem” of bilingual lexical access: Evidence for language-switch costs with univalent stimuli. Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 28, 385–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/20445911.2016.1152274 | reading aloud | 2 | Chinese/English | 73.43 73.43 | not applicable |

| 58 | Stasenko, A., Matt, G. E., & Gollan, T. H. (2017). A relative bilingual advantage in switching with preparation: Nuanced explorations of the proposed association between bilingualism and task switching. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 146, 1527–1550. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/xge0000340 | cued | 8 | Spanish/English | 90.77 90.77 90.77 90.77 23.19 23.19 23.19 23.19 | CTI 116/1016 ms |

| 59 | Timmer, K., Christoffels, I. K., & Costa, A. (2019). On the flexibility of bilingual language control: The effect of language context. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 22, 555–568. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728918000329 | cued | 2 | Dutch/English | 74.00 79.00 | CTI 0 ms |

| 60 | Timmermeister, M., Leseman, P., Wijnen, F., & Blom, E. (2020). No Bilingual Benefits Despite Relations Between Language Switching and Task Switching. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01832 | cued | 0 | Dutch/Turkish | 114.23* | CTI 650 ms |

| 61 | Verhoef, K., Roelofs, A., & Chwilla, D. J. (2009). Role of inhibition in language switching: Evidence from event-related brain potentials in overt picture naming. Cognition, 110, 84–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2008.10.013 | cued | 1 | Dutch/English | 51.40 | CTI 500/1250 ms |

| 62 | Verhoef, K. M. W., Roelofs, A., & Chwilla, D. J. (2010). Electrophysiological evidence for endogenous control of attention in switching between languages in overt picture naming. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 22, 1832–1843. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn.2009.21291 | cued | 4 | Dutch/English | 55.00 55.00 55.00 55.00 | CTI 500 ms |

| 63 | Vorwerg, C. C., Suntharam, S., & Morand, M.-A. (2019). Language control and lexical access in diglossic speech production: Evidence from variety switching in speakers of Swiss German. Journal of Memory and Language, 107, 40–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2019.03.007 | cued | 4 | Swiss

German/German Swiss German/Tamil | 100.00 100.00 83.33 83.33 | CTI 0 ms |

| 64 | Weissberger, G. H., Wierenga, C. E., Bondi, M. W., & Gollan, T. H. (2012). Partially overlapping mechanisms of language and task control in young and older bilinguals. Psychology and Aging, 27, 959–974. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028281 | cued | 2 | English/Spanish | 95.38 98.31 | CTI 2500 ms |

| 65 | Wong, W. L., & Maurer, U. (2021). The effects of input and output modalities on language switching between Chinese and English. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1017/S136672892100002X | alternating runs | 2 | Chinese/English | 76.82 | not applicable |

| 66 | Wu, J., Kang, C., Ma, F., Gao, X., & Guo, T. (2018). The influence of short-term language-switching training on the plasticity of the cognitive control mechanism in bilingual word production. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 71, 2115–2128. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747021817737520 | cued | 2 | Chinese/English | 65.69 62.24 | CTI 0 ms |

| 67 | Wu, J., Yang, J., Chen, M., Li, S., Zhang, Z., Kang, C., Ding, G., & Guo, T. (2019). Brain network reconfiguration for language and domain-general cognitive control in bilinguals. NeuroImage, 199, 454–465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.06.022 | cued | 0 | Chinese/English | 69.32 | CTI 0 ms |

| 68 | Zhang, Y., Cao, N., Yue, C., Dai, L., & Wu, Y. J. (2020). The Interplay Between Language Form and Concept During Language Switching: A Behavioral Investigation. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 791. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00791 | cued | 3 | Chinese/English | 65.83 | CTI 0 ms |

| 69 | Zhang, M., Wang, X., Wang, F., & Liu, H. (2019). Effect of Cognitive Style on Language Control During Joint Language Switching: An ERP Study. Journal of psycholinguistic research, 49, 383–400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10936-019-09682-7 | cued | 4 | Chinese/English | 65.38 60.00 | CTI 750 ms |

| 70 | Zheng, X., Roelofs, A., Farquhar, J., & Lemhöfer, K. (2018). Monitoring of language selection errors in switching: Not all about conflict. PLOS ONE, 13, e0200397. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0200397 | cued | 0 | Dutch/English | 86.00 | CTI 0 ms |

| 71 | Zheng, X., Roelofs, A., Erkan, H., & Lemhöfer, K. (2020). Dynamics of inhibitory control during bilingual speech production: An electrophysiological study. Neuropsychologia, no pagination specified. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2020.107387 | cued | 0 | Dutch/English | 84.00 | CTI 0 ms |

| 72 | Zhu, J. D., Seymour, R. A., Szakay, A., & Sowman, P. F. (2020). Neuro-dynamics of executive control in bilingual language switching: An MEG study. Cognition, 199, 104247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2020.104247 | cued | 0 | Chinese/English | 60.00 | CTI 750 ms |

| 73 | Zhu, J. D., & Sowman, P. F. (2020). Whole-Language and Item-Specific Inhibition in Bilingual Language Switching: The Role of Domain–General Inhibitory Control. Brain Sciences, 10, 517. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10080517 | cued | 6 | Chinese/English | 87.68† 77.96 | CTI 0 ms |

[i] Note: 1 The dominant language (L1) is printed in bold. 2 Dominant/less dominant proficiency values refer to the values given in the respective study. When no dominant language proficiency values were reported, the highest possible values of the respective measurement for less dominant language proficiency assessment were used. When different conditions/samples were assessed, we decided – for the sake of transparency – to report all values, explaining why there are several less dominant/dominant proficiency values. CTI = Cue Target Interval, TCI = Target Cue Interval, RCI = Response Cue Interval *PPVT receptive vocabulary in Dutch and Turkish (the dominance ratio was clarified with the authors); † based on MINT Scores in L1 and L2; +based on LexTaleScores. § SOA was manipulated between subjects only in Experiment 5; only descriptive data from short (500 ms) and long (800 ms) were requested; $ only Experiment 1 considered as Experiment 2 used blocked sentence conditions; # only Experiment 1 taken into account as no switch-specific instructions were given for Experiment 2.

Table 2

Priors for the fitted models using all data points.

| PARAMETER | PRIOR |

|---|---|

| Intercept | t(3, 847.5, 215) |

| b | normal (0, 10) |

| sd | t(3, 0, 215) |

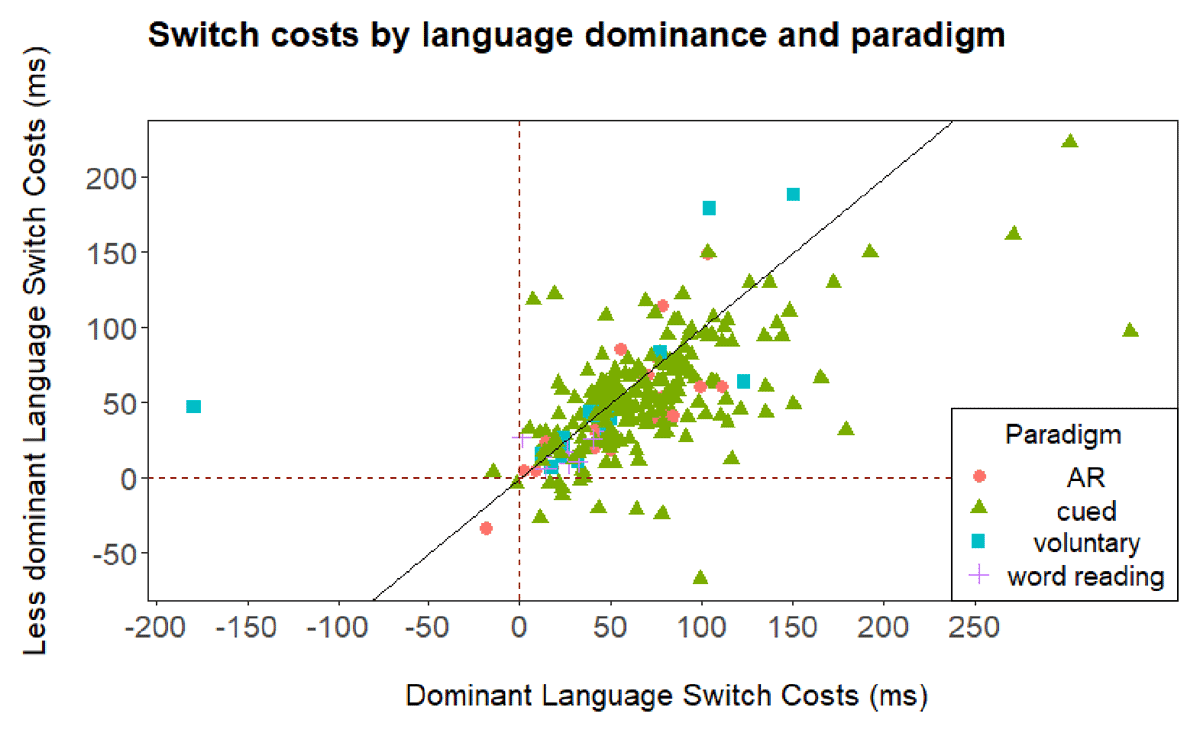

Figure 1

Language switch cost as a function of language dominance and paradigm for all data points included in the meta-analysis. AR stands for alternating runs.

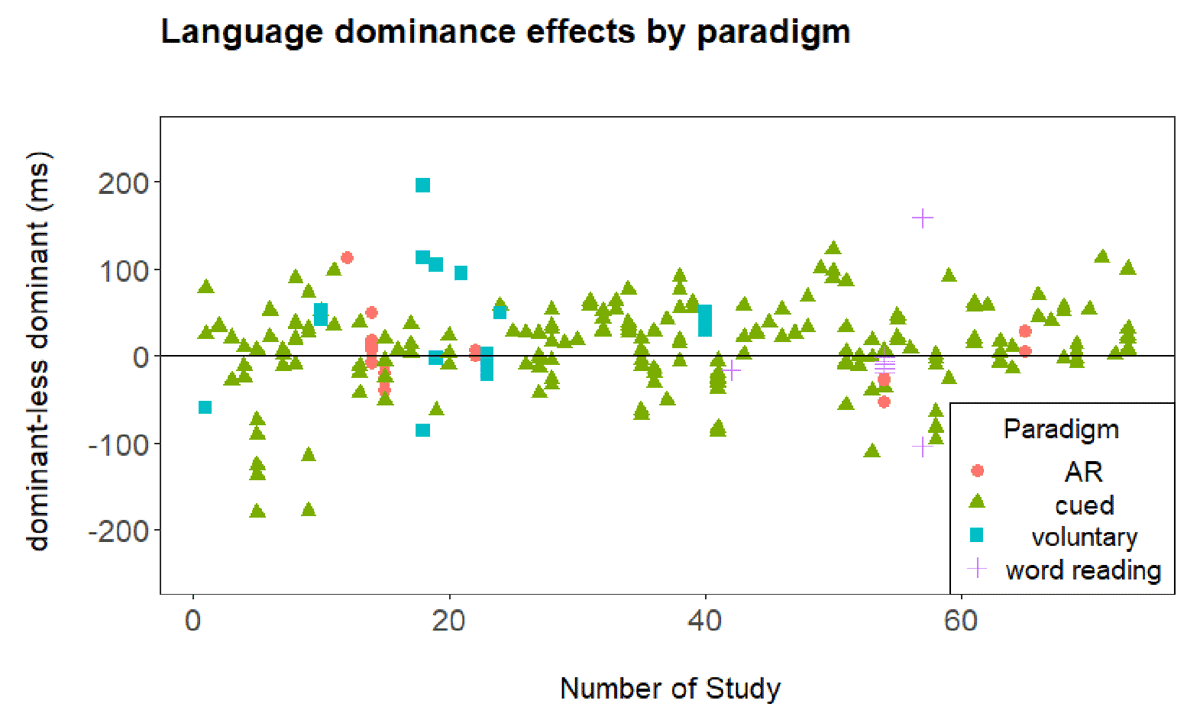

Figure 2

Language dominance effects (i.e., difference between mean RT in the dominant and less dominant language in mixed-language blocks) and paradigm for all data points included in the meta-analysis. Number of Study refers to the numbering of studies given in Table 1. AR stands for alternating runs.

Table 3

Summary of model diagnostics and parameters estimated as well as credible intervals for the model including the interaction.

| ESTIMATE | ESTIMATED ERROR | LOWER 95% | UPPER 95% | Ȓ | BULK ESS | TAIL ESS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 895.25 | 23.15 | 850.11 | 941.67 | 1 | 556 | 1057 |

| Language Dominance | –4.44 | 2.95 | –10.3 | 1.40 | 1 | 12977 | 11174 |

| Language Transition | 27.13 | 2.85 | 21.58 | 32.68 | 1 | 14162 | 11666 |

| Language Dominance * Language Transition | –3.0 | 2.88 | –8.61 | 2.68 | 1 | 13661 | 11365 |

[i] Note: Estimated mean of the posterior distributions, estimated error of the posterior distributions as well lower and upper 95% credible intervals of the posterior distributions, Ȓ as index for convergence, as well as effective sample size (ESS) for bulk and tail. Remember that language dominance and language transition were contrast-coded with –1 and 1 for dominant and repetition as for less dominant and switch.

Table 4

Summary of model diagnostics and parameters estimated as well as credible intervals for the model without the interaction.

| ESTIMATE | ESTIMATED ERROR | LOWER 95% | UPPER 95% | Ȓ | BULK ESS | TAIL ESS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 892.04 | 23.64 | 844.95 | 937.02 | 1.01 | 368 | 864 |

| Language Dominance | –4.42 | 2.92 | –10.14 | 1.30 | 1 | 14498 | 11961 |

| Language Transition | 27.08 | 2.92 | 21.33 | 32.78 | 1 | 18111 | 11606 |

[i] Note: Estimated mean of the posterior distribution, estimated error of the posterior distribution as well lower and upper 95%, credible intervals of the posterior distribution, Ȓ as index for convergence, as well as effective sample size (ESS) for bulk and tail. Remember that language dominance and language transition were contrast-coded with –1 and 1 for dominant and repetition as for less dominant and switch.

Table 5

Priors for the fitted models with proficiency ratio as continuous variable.

| PARAMETER | PRIOR |

|---|---|

| Intercept | t(3, 862, 212) |

| b | normal (0, 10) |

| sd | t(3, 0, 212) |

Table 6

Summary of model diagnostics and parameters estimated as well as credible intervals for the model including the interaction for analysis with proficiency ratio as continuous variable.

| ESTIMATE | ESTIMATED ERROR | LOWER 95% | UPPER 95% | Ȓ | BULK ESS | TAIL ESS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 897.33 | 23.97 | 850.06 | 943.41 | 1.01 | 512 | 1116 |

| Language Dominance | –0.08 | 5.96 | –11.71 | 11.62 | 1 | 5975 | 8679 |

| Language Transition | 18.02 | 5.88 | 6.44 | 29.52 | 1 | 6554 | 10090 |

| Proficiency Ratio | –9.77 | 9.54 | –28.52 | 8.77 | 1 | 11794 | 11805 |

| Language Dominance

* Proficiency Ratio | –6.57 | 7.51 | –21.33 | 8.08 | 1 | 5903 | 9044 |

| Language

Transition* Proficiency Ratio | 11.48 | 7.42 | –3.19 | 26.13 | 1 | 6325 | 9242 |

| Language Dominance * Language Transition | –2.51 | 5.99 | –14.17 | 9.26 | 1 | 6632 | 9747 |

| Language Dominance * Language Transition * Proficiency Ratio | –0.69 | 7.52 | –15.42 | 13.86 | 1 | 6717 | 9829 |

[i] Note: Estimated mean of the posterior distributions, estimated error of the posterior distributions as well lower and upper 95% credible intervals of the posterior distributions, Ȓ as index for convergence, as well as effective sample size (ESS) for bulk and tail. Remember that language dominance and language transition were contrast-coded with –1 and 1 for dominant and repetition as for less dominant and switch, whereas Proficiency Ratio was obtained by dividing less dominant language proficiency rating by dominant language proficiency rating using the values and dominance assignments given in the study or by later queries, for scaling issues decimal values and not percent proficiency were used.

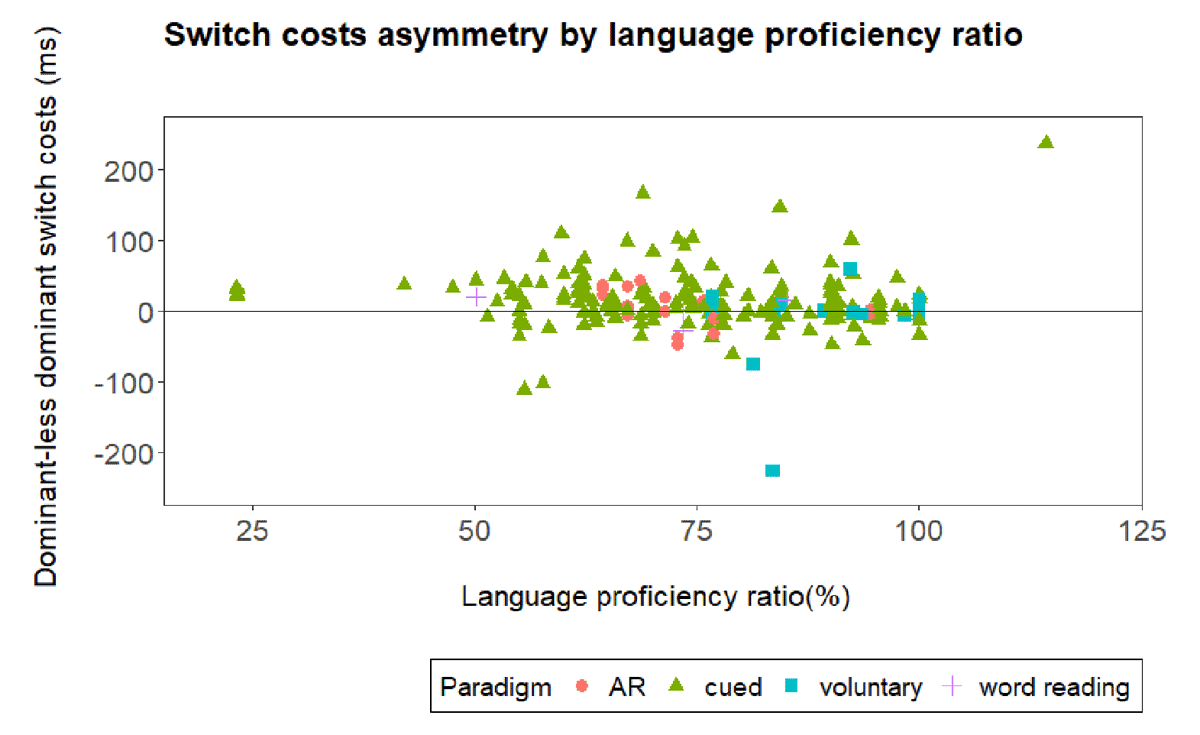

Figure 3

Asymmetrical switch costs (i.e., difference between switch costs for the dominant and less dominant language [switch costs dominant – switch costs less dominant]) by language proficiency ratio (%) and paradigm for all data points included providing language proficiency measures. AR stands for alternating runs.

Table 7

Priors for the fitted models using cued language switching only.

| PARAMETER | PRIOR |

|---|---|

| Intercept | t(3, 877, 203.1) |

| b | normal (0, 10) |

| sd | t(3, 0, 203.1) |

Table 8

Summary of model diagnostics and parameters estimated as well as credible intervals for the model including the interaction for cued language switching only.

| ESTIMATE | ESTIMATED ERROR | LOWER 95% | UPPER 95% | Ȓ | BULK ESS | TAIL ESS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 891.16 | 22.05 | 847.92 | 935.33 | 1.01 | 615 | 1404 |

| Language Dominance | –3.83 | 2.95 | –9.68 | 1.97 | 1 | 17236 | 11852 |

| Language Transition | 28.55 | 2.95 | 22.7 | 34.33 | 1 | 17123 | 11503 |

| Language Dominance * Language Transition | –3.78 | 2.96 | –9.52 | 2.11 | 1 | 16434 | 10385 |

[i] Note: Estimated mean of the posterior distributions, estimated error of the posterior distributions as well lower and upper 95% credible intervals of the posterior distributions, Ȓ as index for convergence, as well as effective sample size (ESS) for bulk and tail. Remember that language dominance and language transition were contrast-coded with –1 and 1 for dominant and repetition as for less dominant and switch.

Table 9

Priors for the fitted models using cued language switching with short CTI only.

| PARAMETER | PRIOR |

|---|---|

| Intercept | t(3, 923, 170.5) |

| b | normal (0, 10) |

| sd | t(3, 0, 170.5) |

Table 10

Summary of model diagnostics and parameters estimated as well as credible intervals for the model including the interaction for cued language switching with short CTI only.

| ESTIMATE | 1 ERROR | LOWER 95% | UPPER 95% | Ȓ | BULK ESS | TAIL ESS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 927.93 | 32.84 | 863.1 | 992.17 | 1 | 1090 | 1998 |

| Language Dominance | –8.83 | 3.6 | –15.96 | –1.79 | 1 | 10809 | 10835 |

| Language Transition | 29.64 | 3.64 | 22.4 | 36.79 | 1 | 9431 | 10531 |

| Language Dominance * Language Transition | –2.94 | 3.56 | –9.83 | 4.07 | 1 | 9949 | 10825 |

[i] Note: Estimated mean of the posterior distributions, estimated error of the posterior distributions as well lower and upper 95% credible intervals of the posterior distributions, Ȓ as index for convergence, as well as effective sample size (ESS) for bulk and tail. Remember that language dominance and language transition were contrast-coded with –1 and 1 for dominant and repetition as for less dominant and switch.