Introduction

The use of social media in the context of higher education is far from new. The emergence of social media platforms – initially often referred to as ‘Web 2.0’ – was quickly followed by questions of how this form of technology could be used in higher education (Franklin & Van Harmelen 2007; Selwyn 2008). Over the course of more than fifteen years now, practices around the use of social media in higher education have moved from being niche and peripheral, to embedded within academic work and scholarly practice (Carrigan 2016; Daniels & Thistlethwaite 2016).

Social media has always been a wide-ranging term, encompassing any websites, services or platforms online where the public can share user-generated content and connect with others. As social media use has become more entrenched in academic life, some platforms are now defunct while a small number of platforms have become almost ubiquitous. As an example of how influential the relationship between social media and higher education can be, social media platforms are increasingly used as a way to evidence engagement and impact, which is highly incentivised in the UK higher education sector (Carrigan & Jordan 2022). Twitter (now known as X) is one such site. Twitter was referred to in 3% of impact case studies in the 2014 Research Excellence Framework (REF) national research audit, increasing to 8% in the 2021 REF (Carrigan 2023; Carrigan, Jordan & Wyman 2024). However, recent developments in the platform have highlighted the precarity of relying on corporate infrastructure to support public scholarship. Since its acquisition by Elon Musk in April 2022, and subsequent actions on community standards and rebranding (Swogger 2023), a substantial proportion of academics are believed to have reduced their activities or left the site (Williams 2023).

The changes at Twitter prompted a perceived flurry of migration to new platforms (such as Bluesky, Mastodon, and Threads, for example) and increased engagement of other existing sites (such as LinkedIn). It was against this background of uncertainty that in June 2023 we launched a call for submissions to a special collection of the Journal of Interactive Media in Education (JIME) on the topic of social media in higher education. As academics who use social media, we are aware of a definite sense of turmoil and movement between platforms and infrastructures, but it is challenging at the moment to get an accurate view of the repercussions of this. Throughout 2023, Chambers (2023) generated some evidence of the decline at the site overall, through app download statistics and tracking the frequency of alternative platform handles being mentioned in user bios. This suggested that app downloads were declining steeply, and that other platforms – in particular, Mastodon and Bluesky – were ascending.

However, there is still a great deal of uncertainty around these trends. There is a complex path from downloading an app through to becoming a regular user, particularly for professional use which intersects with the dynamics of the context in which the user is working. The available evidence does suggest the period of Twitter’s ubiquity within higher education is coming to an end, with little clarity at this stage about what might follow it. Bearing this in mind, we set a purposefully broad scope for the call for papers, framed by the question which the Twitter interface itself poses to users: “What’s happening?”.

The transformation within Twitter

The familiar prompt, “What’s happening?”, seen with sufficient regularity by users to fade into the background, has an interesting history. When the platform launched in July 2006, it initially asked users “What’s your status?” (Dorsey 2006); by the end of the year, this had changed to a prompt of “What are you doing?” (Twitter 2006). This remained in place until 2009, when it was replaced with “What’s happening?” (Stone 2009). The change reflected an agenda amongst the firm’s executives to establish Twitter as an ‘information network’ rather than a ‘social network’ (Burgess & Baym 2020: 12–13). While the change was subtle, it replaced the viewpoint of the user with the events the user could witness or describe. In the words of Burgess and Baym (2020: 36), the contrast between “What are you doing? (in your everyday life)” and “What’s happening? (in the world)” involves “subtly but fundamentally shifting the communicative purposes of the platform, at least in terms of how they are expressed to us”. It suggested Twitter’s potential to become a conduit for information flow within sectors and across them, leading it to take on a crucial status for many professional groups and exercise a cultural influence far beyond that suggested by its user numbers.

We can see in these shifts attempts to nudge user behaviour in a manner which reflects the shifting ambitions of the platform’s operators, as their sense of what Twitter should be used for has changed over time. This vision of Twitter as a window on the world, a means to track real-time events through the unparalleled vantage points of millions of different users, came to define the platform’s place in the wider ecology of social media. There was a convergence between the experience of users and the ambitions of the firm to make the platform a “powerful system for helping people find out what’s happening now that they care about”, as the co-founder Evan Williams once put it (Burgess & Baym 2020: 90). This was certainly the experience which many academics had in the 2010s, with Twitter becoming a crucial mechanism through which professional networks coalesced and information was shared within them (Carrigan 2016).

This ambition was expressed in but also supported by the simple prompt, with the routine framing of external events nudging users to approach these platforms in these terms. The question “What’s happening?” was a simple question, but a powerful one. In contrast, users logging into the platform from May 2023 onwards find themselves greeted with the prompt “What is happening!?”. The exclamation mark and the removal of the contraction were added in May 2023, six months after Elon Musk’s takeover was finalised after months of speculation. The platform was still called Twitter at this stage, before its renaming as X in July 2023. There has been a long sequence of controversial changes made to the platform since the takeover, from the introduction of subscriptions, the removal of two-step authentication from non-subscribers and huge cuts to the online safety teams. In this context, the addition of an exclamation mark might not seem significant but it is symbolic of the changes, in the frantic and harried tone it introduces to a previously relaxed question. It conveys a sense of urgency and perhaps crisis. It also coincided with many academics feeling they needed to explore alternatives to the platform, even if they might not have yet felt ready to leave it permanently.

It is significant that until recently, Twitter’s relatively open orientation towards social research set it apart from other platforms. It offered a sophisticated Application Programming Interface (API) that was easy to access, leading to a reliance on the platform amongst researchers exploring trends on social media and arguably being part of the reason why “Twitter” and “Social media” had almost become synonymous (Calma 2023). Free access to the API was ended by the firm in February 2023 and paid tiers were launched the following month. Whereas the “Twitter Firehose” once delivered all tweets in real-time, the enterprise API tiers range from $42,000 per month up to $210,000 per month, placing access obviously beyond all but the most well-funded research projects.

Even if Twitter was unusual for its degree of access, it was not the only platform which enabled access to its platform data via an API. More generally, the progressive restriction of access to social media data through APIs has diminished the reproducibility of research in the field (Davidson et al. 2023). Within the past decade, Facebook (van der Vlist et al. 2022) and LinkedIn (Hogan 2018) have been high-profile examples of shifts from freely available APIs to much-reduced data access. More recently, in April 2023 the social annotation platform Reddit precipitated a significant pushback from its user community when a transition towards payment for API issues was announced (Peters 2023). Their stated reason was to avoid the service being scraped to provide data for generative AI models, responding to the widely reported use of Reddit data for the training of OpenAI’s GPT 4 model. It might be a reasonable proposition that a firm with a multibillion valuation, significantly higher than Reddit’s valuation as a firm, is expected to pay for access to the data upon which the development of its services depends. But as with Twitter’s imposition of charges, Reddit’s charge of 24 cents per 1,000 API requests inevitably had collateral damage. The main object of concern in protests from their users was access to third-party apps, which many regular users relied upon for access to the platform. This was because, unlike Twitter, Reddit committed to continuing to provide free access for academic researchers. Even so, we can see a direction of travel here in which the platforms which had been relatively open seek to monetise the data, given the premium placed upon it in a sector driven increasingly by imperatives of data accumulation. This illustrates how change in the platform ecosystem is not restricted to its consumer-facing aspects. There is a broader transformation underway here,1 with significant implications for higher education as a site of knowledge production and as a sector which has incorporated social platforms into its knowledge infrastructure.

These issues raise serious concerns about the integrity of academic research into social media platforms (Davidson et al. 2023) and risk development of what Lazega (2020) describes as ‘privatized social science’. It is important to recognise that groups other than researchers used APIs to access these platforms. The most high-profile consequence is for third-party developers seeking to build tools which enable users to engage with the platform through priority software. In this way, social media firms are cutting off access to a commercial ecosystem, which they encouraged to develop around their software, in order to exercise greater control over the user experience, and maximise the potential for its monetisation. However, it represents a significant transformation in the platform landscape, in which an existing problem of how to generate scientific knowledge of online social behaviour becomes pervasive.

There remains social science being undertaken within these firms, constituting what are in effect the biggest real-time behavioural science experiments in human history, but these are primarily oriented towards the commercial imperatives of the firms (e.g. increasing user engagement, maximising advertising revenue) rather than knowledge production as a public good. While research teams from these firms do publish in scientific journals and engage in public outreach, these tend to be the exception rather than the rule, leading to concerns about a privatised social science undertaken purely in pursuit of corporate interests. There was already a stark gap between the digital social research which could be undertaken by social scientists working within these firms and those operating outside them, reflecting differential access to platform data which encompasses increasingly broad swathes of social activity. If the restriction of API access is the start of an ongoing trend, this gap will become even starker over time, with important ramifications for who has what knowledge about which changes are underway within social and political life.

The JIME Twitter account as a case study

The combination of fundamental shifts in management and governance of the platform, and locking down of access to data, makes it particularly challenging at present to understand the implications for users with any clarity. While Twitter network data could previously be readily accessed automatically through the API and software such as NodeXL, the alternative now is to manually collect data – which would be too arduous and resource-intensive to be able to collect network data. However, some manual data collection strategies remain feasible, such as reading follower bios for the inclusion of handles associated with emerging alternative platforms (Chambers 2023).

Like many other Twitter users, during 2023 we have been questioning the impact of the changes on the platform from the perspective of the JIME Twitter account. To what extent has the JIME Twitter network degraded, in terms of reduced numbers of followers and levels of engagement? Should we consider moving to a different site, and if so, which one? While different platforms are perceived to be associated with different audiences in nuanced ways (Jordan 2020), the advice to think first about your audience when choosing a social media channel breaks down at this point, when it is far from clear where the audience has ‘gone’, or that the alternative platform is so new that norms and expectations are yet to be established.

We had some archival network data, the JIME account (@JIME_journal) ego-network which was collected in January 2019, before a period of active engagement and growth in terms of number of followers, which could be used to provide a snapshot of followers historically. The removal of API access prevented running the same data collection and comparing the structural characteristics of the ego-network then and now directly. However, it was feasible to collect the list of followers in January 2024 manually, and while doing so also noting whether alternative social media handles were referred to in user bios.

When the archived network data was collected in January 2019, the JIME account had 231 followers. In January 2024, the account had 1,037 followers. While acknowledging that the follower count had changed substantially (ideally, it would have been better to compare January 2024 to January 2022, rather than 2019) and it was not possible to pinpoint when accounts were deactivated, this at least allowed us to ask how many of the accounts which followed JIME in January 2019 still do so. Of the 231 followers at that point, 40 no longer follow the account. While this included one account suspension and eight instances of unfollowing, the majority of missing accounts (31) were due to account deletions, suggesting a 13% reduction compared to the 2019 sample (we have no way of knowing at what point the accounts were deleted however, or how many accounts followed and were subsequently deleted in the meantime).

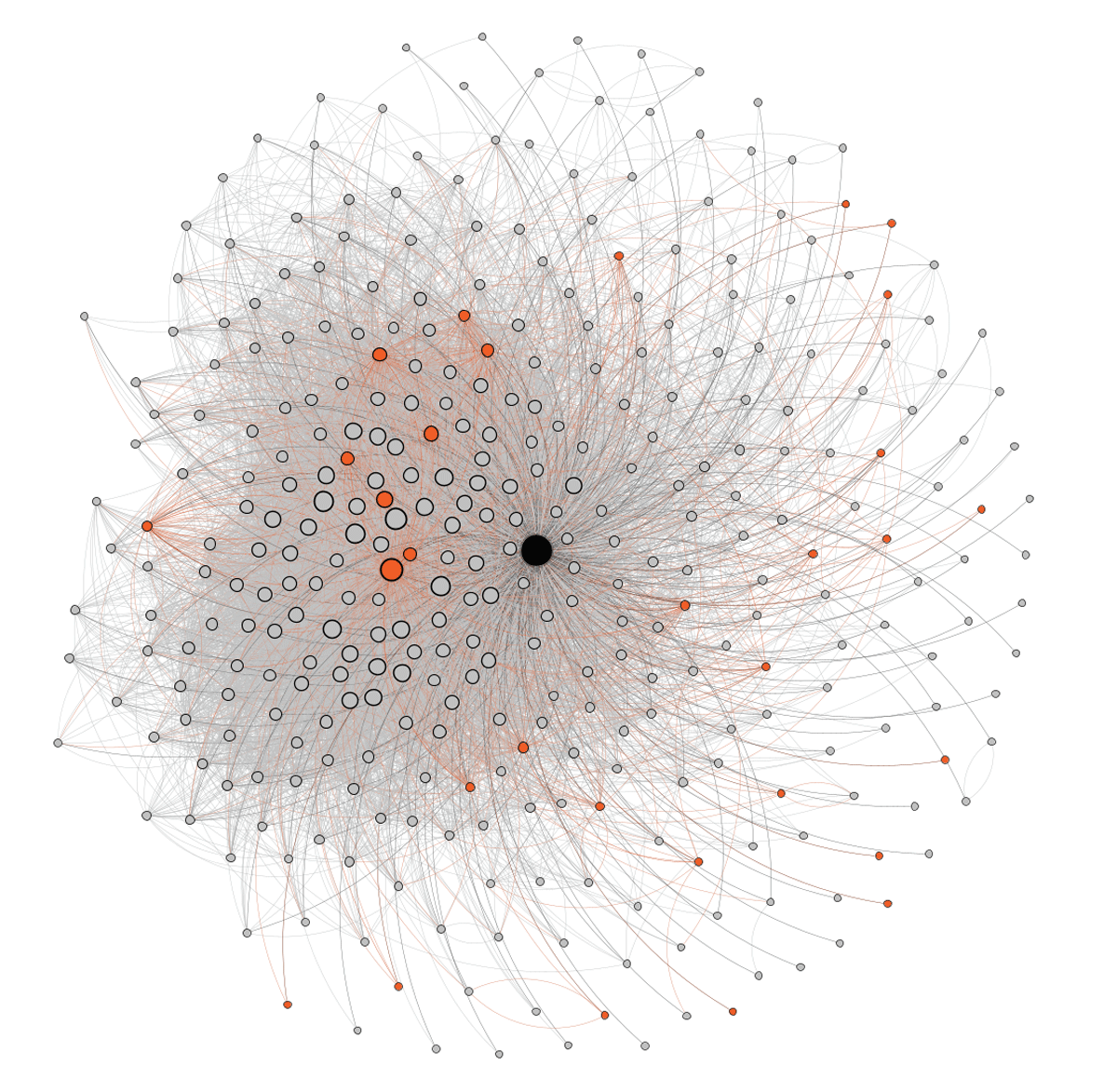

This raises a question of how the account deletions relate to the network structure – are they more likely to be peripheral, with minimal effect, or more embedded in the network? We were able to address this by looking at the ego network as collected in 2019, and colour-coding nodes which represent subsequently deleted accounts (Figure 1). While approximately two-thirds of the deleted accounts are more peripheral in the network, a number did occupy highly connected positions within the dense core of the network, which suggests that influential nodes are being lost.

Figure 1

Ego-network of the JIME Twitter account, collected in January 2019. Ego – the JIME account – is shown in black; nodes are scaled according to degree; and subsequent account deletions are shown as orange nodes.

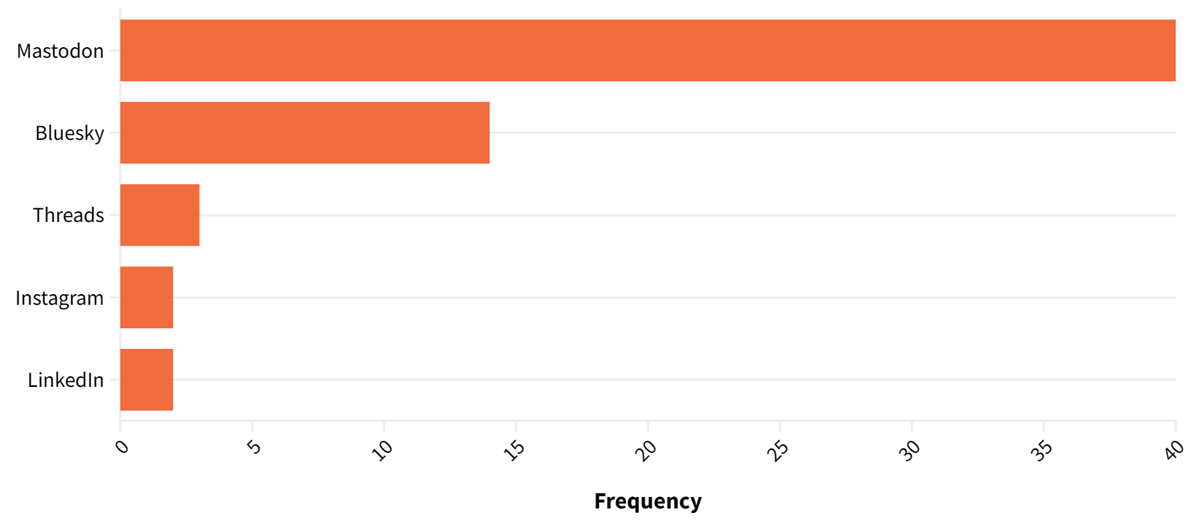

While examining the followers list in January 2024, we also adopted the approach used by Chambers (2023) and logged instances where follower bios included information about alternative platforms, acting as a note to redirect followers. Of the 1,037 followers at this point, 57 (5%) included this information, with a further two who stated that their accounts were dormant without specifying an alternative. This is certainly an underestimate, however, as there are likely to be many more followers who have signed up to other services but have not taken the additional optional step of adding this information to their bio. A breakdown of frequencies according to the particular platform mentioned is shown in Figure 2. This aligns with the findings from Chambers (2023) which put Mastodon as the lead alternative, although Bluesky is also rising. An interesting gap is present here between Bluesky and Threads, which are at comparable levels when considering Twitter more generally (Chambers 2023).

Figure 2

Frequency of alternative social network platforms mentioned in bio texts of accounts following @JIME_journal at X, January 2024.

These findings illustrate the changes we are discussing. There are prima facie signs of the network which coalesced around the journal’s account beginning to unravel, with a significant minority of followers either having deleted their accounts or signifying through their profile that their attention is now directed elsewhere. Even if these users represent a minority of those on the platform, withdrawal and redirection of their activity diminish the value which remaining users can find in the network. In this sense unravelling is a process rather than a singular event, inverting the ‘network effects’ (the value of a service increasing as its user base grows) upon which the growth of platforms depends. The example offered here is a small and specialised case study. But the future does not look bright for X if similar stories can be told about other accounts across the platform, as we suspect is the case.

Topics within the special collection

While the uncertainty around the declining influence of X means that it is probably still too early to fully appreciate its consequences for academics and higher education, it is striking that one theme emerged as a strong common thread across all the papers included in the special collection: identity. The collection of papers spans a range of different locations and disciplinary perspectives, and while the conceptualisation of social media varies from particular platforms to a broader collective view, discussions of expressing identity as a member of a community or communities, are a common theme throughout. These concepts are often considered in terms of tensions and trade-offs, which underscores the sometimes uneasy relationship between higher education and social media.

In their paper ‘“Visibility, transparency, feedback and recognition”: Higher Education Scholars Using Digital Social Networks’ Romero-Hall et al. report findings from a survey of 307 scholars working in higher education, who actively use social media in their roles. This provides an up-to-date view of the reasons why academics use social media professionally. Notably, despite X being the principal platform through which invitations to participate were circulated, LinkedIn emerged as the platform which most respondents use for professional networking (X was ranked third). Benefits and challenges are identified, and insight is provided into the trade-offs which academics make in the process. Furthermore, they examined participants’ perceptions of their imagined audiences online, exposing links to identity in terms of self-presentation and impression management.

Focusing on the role of academics as teaching practitioners in higher education, Machado et al. explored ways in which social media can improve learning for students in a practice-based paper drawing upon the authors’ experiences across four different disciplines in ‘Entering the Social Media Stratosphere: Higher Education Faculty Use of Social Media with Students across Four Disciplines’. The paper provides insights into rich conversations undertaken as part of a Teaching Circle dialogue between a small group of professors. This illustrates the significance of the platform for professional development, as well as what is at stake in the unravelling of the networks upon which this depends.

Tying into the issue of social media and research impact, which was also included in the call, Knipp presents a study focused on the use of academic social networking sites Academia.edu and ResearchGate in ‘Digital Scholarship from the Periphery: Insights from Researchers in Chile on Academia.edu and ResearchGate’. Through interviews with Chilean university researchers, tensions were explored between three aspects of using the sites, including self-promotion, building a reputation, and altmetrics as a way of quantifying this. The tensions and compromises echo the tradeoffs noted by Romero-Hall et al. Furthermore, the tensions highlight the uncomfortable relationship between higher education and capitalism through the increased platformisation of aspects of academic work and identity.

Two papers address the issue of professional practice by academics in the post-Twitter era by reflecting upon the role of Twitter, specifically, and the repercussions of the recent changes to the platform. In ‘‘Sharing’, Selfhood, and Community in an Age of Academic Twitter’ Mahon and Bergin take an arts-based approach, using fictionalised scenarios, to prompt reflection and act as a starting point for discussion in relation to social theory. Through the account, they provide a thoughtful reflection on the dynamics behind the acts through which Twitter has become embedded in academic life, and how this relates to notions of identity and authenticity. This is crucial for understanding how the post-Twitter shift is likely to impact upon the sector.

Koutropoulos et al. focus specifically upon the consequences for higher education networks online, following the disruption and disaffection with Twitter, in ‘Lines of Flight: The Digital Fragmenting of Educational Networks’. The team of networked scholars, all previously actively engaged with the Twitter platform, use an innovative ‘zigzag’ writing methodology, to reflect on and respond to the experiences of others, moving beyond singular accounts to provide a broader insight into their collective experiences of the decline of the platform and its consequences. As such, it provides insight into the emergent academic social media ecosystem, post-Twitter.

Finally, in ‘Unveiling the TikTok Teacher: The Construction of Teacher Identity in the Digital Spotlight’, Ulla, Lemana and Kohnke maintain a focus on identity, but exploring identity in the context of a new and under-studied social media platform in the context of higher education. Their study addresses the use of TikTok by five teachers of English as a foreign language, at a university in Thailand. The study reveals rich insights into how the short video-sharing platform acts as a medium for expressing a wider range of aspects of identity – “expressive, relational, adaptive and progressive identities” – and serves to enhance perceived authenticity in their roles as educators.

Looking ahead

Although initially we set out to ask ‘What’s happening?’, one of the main conclusions we have reached throughout initiating and preparing this special collection is that at present, there is a good deal of uncertainty around this, and it is not a question which can be answered yet. It is perhaps too soon to reach any firm conclusions about the impact of the changes at Twitter/X – it is very much still in a state of flux. There are signs of a multiplatform landscape taking shape, in which users routinely2 operate across a wider range of platforms than was previously the case. But it remains to be seen whether this is a temporary phenomenon or the new normal. While there is evidence that migration from Twitter to other platforms is taking place, a definitive alternative has not been established yet (Mastodon was an early front-runner, but it may be declining – while Bluesky is rising in popularity; Chambers 2023). It is not clear yet whether the changes herald the death of Twitter, or whether it will still be useful albeit with a reduced level of engagement.

A large proportion of users currently remain, and it is not the first period of turbulence on the platform (for example, the introduction of the algorithmic timeline sparked the #RIPTwitter hashtag; DeVito, Gergle & Birnholtz 2017). Having built up significant networks of connections – and being a space where academic hierarchy is less of a barrier to doing so (Jordan 2019) – it is perhaps understandable that there has not been a more substantial level of account deletions. Twitter users may be reluctant to delete accounts en masse. While collecting the 2024 JIME followers data, for example, it was striking how wide a reach the account has. The social capital established on the platform is highly valued by many academics, even if the unravelling of networks means that it will be decreasingly possible to translate that into practical influence or reward. But for now there are rewards still available, even if the value of the platform might be diminishing in real terms. What is clear, from the collection of papers in particular, is that social media remains closely linked to academic identity and that while Twitter has been a major part of this, it is only one in a range of platforms used by academics. It is critical for ongoing work to focus on documenting and understanding the changes to the scholarly social media landscape.

This is a period of tremendous upheaval for social media. Unfortunately, it is becoming more difficult to produce robust knowledge about social media at precisely the moment when we need such insights more than ever. The trend towards removing or rate-limiting free API access limits methodological opportunities for those who cannot pay, while the fragmentation of audiences across platforms creates methodological challenges to which there are no easy solutions. While multi-platform research is demonstrably possible, it is by its nature time-consuming and involves decisions about inclusion and where to draw boundaries which are intrinsically ambiguous in many cases. To understand how academic networks are reconsolidating across platforms do we simply undertake research on each of the platforms which are perceived as being professionally viable for academics? How do we make comparisons across platforms providing sharply differing levels of access to relevant data? Can we assume that social platforms are embedded in organisational settings in the same way? Or do we need distinct models of how specific platforms ‘hook into’ higher education? There are a range of conceptual and methodological challenges posed by the prospect of a multiplatform landscape within higher education. If we want to understand the role of social platforms in the sector then it will be necessary to address these challenges, informed by wider dialogues in fields like Internet Studies and Platform Studies.

Notes

[1] The analysis of these changes is beyond the scope of this editorial but we suggest the underlying drivers are predominately economic. The low interest rate environment which technology firms have occupied for much of their existence reduced investor pressure for profitability, leaving them inclined to seek future gains in an investment environment with few other options. The higher interest rates which have predominated since the Covid-19 pandemic have heightened commercial scrutiny of these firms by investors, particularly those like Twitter which have failed to achieve consistent profitability. In other words, the fragility in the underlying business model has been exposed by macro-economic changes.

[2] The routine use of multiple platforms is integral to this shift. There have always been multiple platforms available and used within the sector. Our contention here is that we may be witnessing a shift in practice such that users routinely use multiple platforms, prompted by existing networks being split across them, such that there is no longer a single platform which occupies the majority of their time and attention.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the authors who responded to the call for papers, and who contributed to the special issue. We would also like to express our gratitude and appreciation to the individuals who kindly acted as peer reviewers for the submissions. Through examining the trends in followers of the JIME Twitter account, we would like to acknowledge and thank Dr Martina Emke for her service as the JIME social media editor from 2019 to 2022, whose activities helped to build the network and audience substantially.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.