Background: Restaging following neoadjuvant therapy has become a pivotal aspect of personalized oncologic care, enabling tailored surgical planning and improved prognostication. High‑resolution pelvic MRI is the most reliable modality due to superior soft‑tissue contrast, multiplanar capability, and functional sequences.

Purpose: To summarize technique, interpretive priorities, diagnostic performance, pitfalls, and clinical impact of MRI in post‑treatment restaging, and to outline emerging advances.

Timing & Technique: Restaging MRI is typically performed 6–12 weeks after chemoradiotherapy or total neoadjuvant therapy. A protocol with high‑resolution T2‑weighted images in sagittal, axial/coronal (orthogonal/parallel to the tumor bed) planes and axial diffusion‑weighted imaging (DWI) with high b‑values and ADC maps is recommended.

Interpretation Priorities

Primary tumor response: Differentiate fibrosis/scar from residual tumor. Features of a complete response include a dark T2 scar without intermediate signal mass and the absence of restricted diffusion (Figure 1).

Margins and planes: Reassess mesorectal fascia (MRF) and the anal sphincter involvement to guide surgical planes.

Vascular involvement: Document regression or persistence of extramural venous invasion (mrEMVI), given its adverse prognostic weight.

Lymph nodes: Compare both mesorectal and lateral lymph nodes to baseline MRI, know your interpretation limitations.

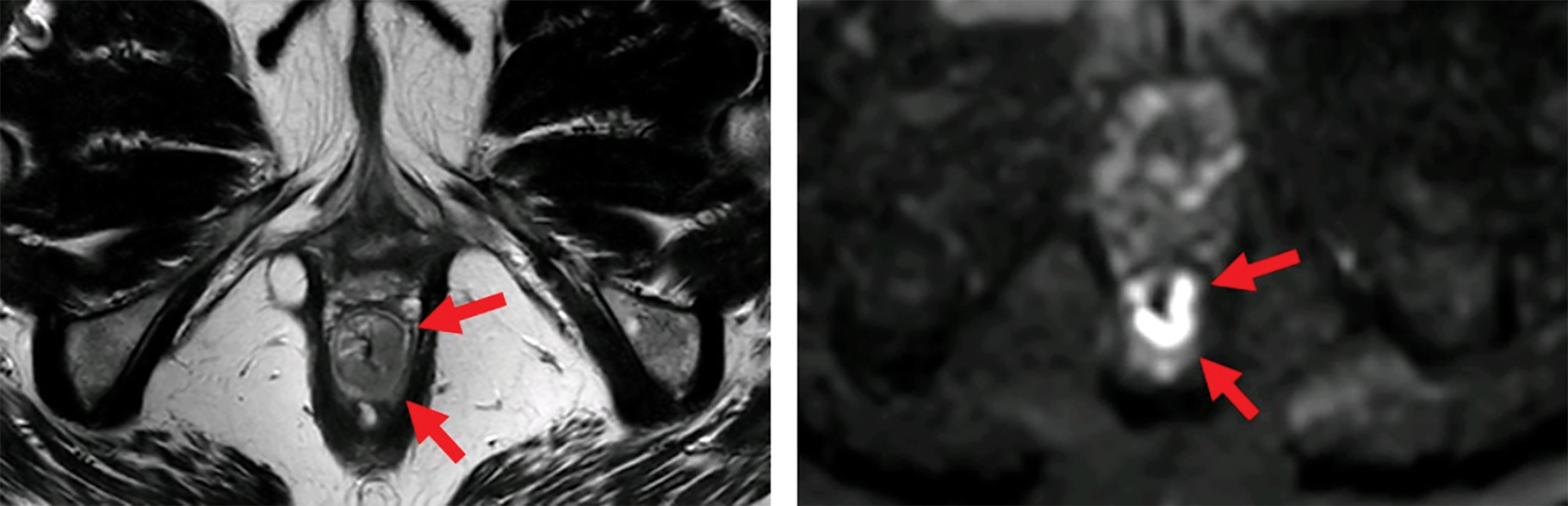

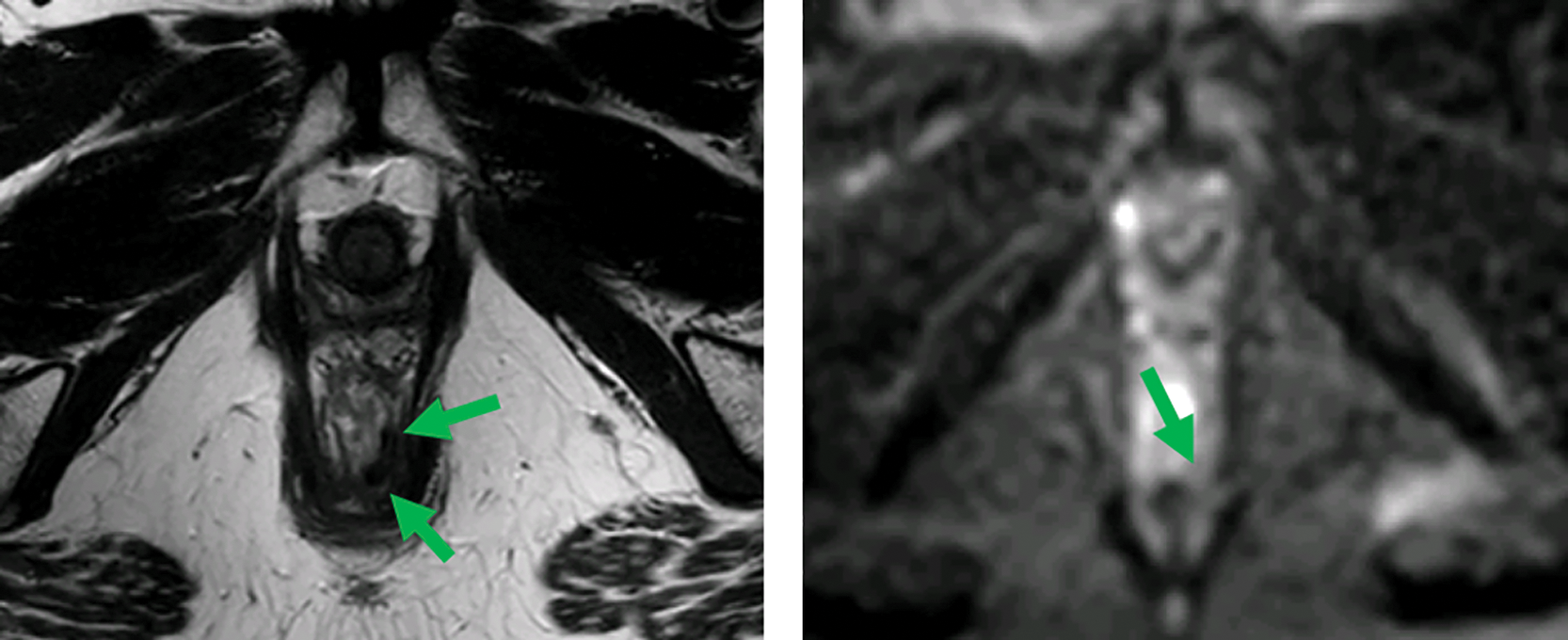

Figure 1

MRI before (top) and after (bottom) neoadjuvant therapy. Axial T2‑weighted and b1000 DWI images show a distal rectal tumor (red arrows). After neoadjuvant therapy, a T2 dark, fibrotic remnant is seen without restricted diffusion (green arrows), indicative of a clinical complete response.

Pitfalls: Post‑treatment fibrosis and desmoplastic reaction can mimic residual disease on T2. DWI “shine‑through,” edema, reactive mucosal signal, and mucinous components may falsely suggest residual tumor. Close correlation with endoscopy and digital rectal examination is essential.

Clinical Impact: MRI restaging significantly influences surgical planning. In patients with good tumor regression, organ preservation strategies such as local excision or even non‑operative approaches may be considered. Conversely, identification of poor responders may prompt a more aggressive surgical approach or consideration for additional systemic therapy.

Future Directions: Radiomics and AI‑assisted analyses show promise for quantitative response prediction and standardization, but require robust multicenter validation before routine adoption.

Conclusion: The ability of MRI to non‑invasively assess tumor response, re‑evaluate surgical margins, and guide organ‑preserving strategies underscores its central role in contemporary rectal cancer management. However, limitations in specificity, inter‑reader variability, and nodal assessment necessitate a multimodal approach that integrates imaging, clinical examination, and endoscopy. High‑quality MRI interpretation and standardization across institutions will be essential for optimizing patient outcomes in rectal cancer care.

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.